January | February 2002 - Boston Photography Focus

January | February 2002 - Boston Photography Focus

January | February 2002 - Boston Photography Focus

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

an improvisation on<br />

mus i c and photograp<br />

Leslie K. Brown, Curator, PRC<br />

From his loft on Third Avenue, John immersed himself in the ferment of<br />

the New York City art scene. Soon after he arrived, John had his first exhibition<br />

at Helen Gee’s Limelight. In 1959, his neighbor Robert Frank asked<br />

an shared. experience<br />

Of Dylan, Cohen recalls a moment in 1962, when he “showed me the words<br />

The eye permits us to experience and to document the thing depicted, but is rarely sufficient to convey the deeper meaning of<br />

John to take production stills of the filming of Pull My Daisy. The images<br />

produced during those sessions are among the finest portraits ever of Allen<br />

Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, and Frank himself. In return, Frank photographed<br />

the New Lost City Ramblers for a series of images that would grace the<br />

covers and liner notes of their albums for years to come. John’s loft became<br />

a crossroads for musicians and artists. An organization of independent photographers,<br />

with members including Lee Friedlander, Gary Winogrand, and<br />

others, was formed there. Southern musicians on their way to and from<br />

performances dropped by, as did Woody Guthrie, Alan Lomax, and others<br />

involved in the folk-music revival.<br />

Throughout the late ’50s and early ’60s, Cohen toured extensively with the<br />

New Lost City Ramblers, sharing the stage with rural musicians like Roscoe<br />

Holcomb and the Stanley Brothers as well as with emerging stars such as<br />

Bob Dylan and Joan Baez. Robert Cantwell, whose When We Were Good<br />

(1996) outstandingly documents the growth and decline of the folk music<br />

revival, noted that during this period the Ramblers “raised the nap of the<br />

revival with newly esotericized discographic sources and a performance style<br />

that sounded as exotic as a Tibetan prayer.”<br />

Also during the late 1950s Cohen took the first of many trips to Peru,<br />

ostensibly to study Andean textile production. In the isolated mountain<br />

region of Q’eros he photographed Indian weavers at work, learning their<br />

vocabulary and rituals and developing a deep appreciation for Andean<br />

music. Years later, Cohen returned to Q’eros to make the films Mountain<br />

Music of Peru (1984) and Carnival in Q’eros (1992). He also recorded and<br />

released two albums of traditional Peruvian music. One of his recordings,<br />

of a young girl singing an Andean huano, was included as a sample of the<br />

sounds of our planet that was sent into space on the Voyager spacecraft.<br />

In 1962, the young Bob Dylan visited for a portrait session on John’s Third<br />

Avenue rooftop. In addition to their common appreciation for traditional<br />

music, the two men shared a close friendship with the ailing Woody Guthrie.<br />

to his new song A Hard Rain’s Gonna Fall. At first it resembled the old ballad<br />

Lord Randall or Where Have You Been Billy Boy. Then it seemed like an<br />

old French symbolist poem to me, and I invited Bob to look at some of<br />

that poetry at my loft. I thought his verses were very strong although I<br />

couldn’t imagine how he would fit them to music. The night of the Cuban<br />

Missile Crisis when it felt like the world was on the brink of atomic collision,<br />

Dylan and I sang together at the Gaslight Café. We did an old Carter<br />

Family song, You’re Gonna Miss Me When I’m Gone, not certain if there’d be<br />

anyone left to miss us.”<br />

By the late ’60s the Ramblers were performing in large halls like the Fillmore,<br />

in lineups with supergroups such as The Grateful Dead, the Jefferson<br />

Airplane, and the Jimi Hendrix Experience. Cohen notes that during this<br />

time “a shift of sensibilities set in. The beat generation had prepared the<br />

stage for the counter culture, while the emerging civil rights movement<br />

shook the social landscape… For me, a decade of wide-eyed wandering<br />

with my camera was closing down… So much of what I’d responded to on<br />

a poetic level was becoming entertainment and commerce… Further, there<br />

was my own dissatisfaction with the prospects of ever getting my work seen<br />

on its intended level. By the time the photography galleries were opening<br />

I was somewhere else.” That “somewhere else” was filmmaking.<br />

John shot his first film, a silent two-reeler, on the rooftop with Dylan.<br />

Beginning with his landmark 1962 feature, The High Lonesome Sound,<br />

John has made a total of fifteen documentary films, including important<br />

work on the folk culture of Peru and on the North Carolina musician<br />

Dillard Chandler (The End of an Old Song, 1970). “I made films about<br />

music,” he writes. “And that challenge became so great and transformative<br />

that it became my main effort for the next twenty years.”<br />

Behind the scenes, but central to the picture, is the growth of John’s own family.<br />

In the early 1960s, Cohen married Penny Seeger. The youngest child of<br />

musicologist Charles Seeger and composer Ruth Crawford Seeger, after the<br />

death of her mother when Penny was eight she lived with her half-brother<br />

Pete. A potter by training, she also sang with her siblings Mike and Peggy on<br />

several collections of American folk music, including the classics American<br />

Folk Songs for Christmas and Animal Folk Songs for Children, both of which<br />

drew extensively from their mother’s folk music collection. To support his<br />

family, John took a position as Professor of Visual Arts at the State University<br />

of New York, Purchase, where he worked until his retirement in 1997.<br />

Penny and John raised two children, Rufus and Sonja, in Putnam Country,<br />

New York. In the summer of 1965, when daughter Sonja was still an infant,<br />

her parents brought her to the Newport Folk Festival where the Ramblers<br />

were scheduled to perform. Uncle Pete Seeger opened the program by playing<br />

a cassette of Sonja crying, announcing to the audience, “Here’s the real<br />

folk music.” Sonja, now an adult, has recorded two highly regarded recordings<br />

with composer Dick Connette’s Last Forever project, which draws its<br />

inspiration from American traditional music. Her brother Rufus, also a<br />

musician, works in New Mexico as a textile craftsman. The Cohen family<br />

is featured in both the exhibition, where photographs document their<br />

growth, and in John’s CD, There Is No Eye: Music for Photographs. The CD<br />

presents a musical counterpoint to the exhibition, with songs by many of<br />

the artists whom John photographed, from Rev. Gary Davis and Holcomb<br />

to Dylan and David Amram, and includes pieces by Rufus and Sonja.<br />

In all of John Cohen’s work, his collecting, photographing, filmmaking,<br />

performing, teaching, and parenting, a layer of pure fact (i.e., the thing<br />

depicted) is combined with a layer of meaning conveyed (i.e., the memory<br />

revived or the tradition shared). The eye permits us to experience and to<br />

document the thing depicted, but is rarely sufficient to convey the deeper<br />

meaning of an experience shared. Individual songs or photographs may<br />

describe specific moments in time, and each moment possess a distinct historical<br />

narrative, which we may know by looking.<br />

But experience is not conveyed by looking, or wisdom by simply reading.<br />

This has been a central theme of the New Lost City Ramblers, and it is<br />

implicit in John Cohen’s photographs as well. Meaning and value are conveyed<br />

not through the eye alone, but through the active and generous<br />

bequest of tradition and knowledge from one generation to another, from<br />

one culture to another, from teacher to student, and from parent to child.<br />

This, for me, is the underlying message of John Cohen’s work, and the<br />

deeper narrative of this exhibition: there is no eye because, in the end, it is<br />

the exchange of songs, the sharing of wisdom, the flow of knowledge, and<br />

the gift of life that are important, and not the individual eye/I.<br />

John P. Jacob, Guest Curator<br />

Penobscot, Maine 2001<br />

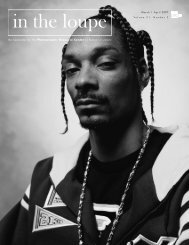

John Cohen’s photograph, Jack Kerouac Listening to<br />

Himself on the Radio, (seen at left) demonstrates, literally and humorously, the<br />

complex conundrum photographers face when attempting to document subjects<br />

of an auditory nature. Can photography adequately capture a musical<br />

moment by recording the performer, or even a snippet of the performance?<br />

In this short improvisation, an etude if you will, I attempt to cast a wider net<br />

and muse upon Cohen’s fascinating photographs within a larger historical<br />

and philosophical context.<br />

From its inception, photography has been lauded as a method for nature to<br />

reproduce itself. While this was meant primarily in the visual sense — cameras<br />

were often compared to eyes — artists have long attempted to capture the<br />

non-perceptual. Those seeking the abstract saw in sound an equivalent for<br />

the internal non-objective world for which they were searching: an aesthetic<br />

“music of the spheres”. While photography and dance seemed to partner more<br />

readily, painting took especially to music: James Abbott McNeill Whistler<br />

and Wassily Kandinsky titled their canvases symphonies and compositions,<br />

while Piet Mondrian explored the pulsating rhythms of jazz.<br />

This is not to say that photographers did not engage music or its attendant<br />

ideas. In fact, some saw photography as particularly suited for the task.<br />

Cohen alludes to this ability when explaining why he did not become a<br />

painter: “The lens became the center of an equation with the visible world on<br />

one side and the interior world on the other.” Many culture mavens at the<br />

turn of the last century were interested in synaesthesia, or the crossing of various<br />

senses whereby one could see music and hear colors. Such beliefs led to<br />

the invention of fascinating instruments such as the color organ, which<br />

played colors instead of music. Photographer Francis Brugiuère made some<br />

of the earliest abstract photographs and films documenting patterns produced<br />

by such an apparatus. Playing off the Theory of Correspondences so<br />

popular with the Symbolists, Alfred Stieglitz photographed clouds, initially<br />

titling them “Music,” intending that they stand in for mental states akin to<br />

those induced by melodies.<br />

Cohen’s exhibition, book, and accompanying CD provide the viewer (and<br />

listener) with a rare opportunity to see (and to hear) what he has recorded.<br />

Although freezing performers in mid refrain or strum, his photographs are not<br />

silent; instead they sing with beautiful formal relationships. When Cohen’s<br />

photographs don’t show music, they imply it, transforming the viewer into a<br />

makeshift deejay. Images of Cohen’s wife in Peru and a lone figure in a Tenth<br />

Street studio, for example, almost give rise to a melancholy dirge.<br />

One would think that photography’s use of a negative and its ability to be<br />

repeated and reinterpreted much like a musical score would make these arts<br />

close cousins. Ansel Adams’s much-repeated comparison of the negative to<br />

sheet music and its printing to performance alludes to this attribute. Quite<br />

the opposite, many photographers even go so far as to destroy their negatives<br />

so no one can translate them. Ironically or aptly, Cohen’s re-discovery of<br />

Left to right: 1. John Cohen, Woody Guthrie at Cooper Union. Courtesy of the artist and<br />

Deborah Bell, New York. 2. John Cohen, Third Avenue, New York City, 1962. Courtesy of the<br />

artist and Deborah Bell, New York. 3. John Cohen, Philadelphia, 1961. Courtesy of the artist<br />

and Deborah Bell, New York. 4. John Cohen, Jack Kerouac listening to himself on the radio.<br />

Courtesy of the artist and Deborah Bell, New York. 5. John Cohen, Harlem, New York City,<br />

1954. Courtesy of the artist and Deborah Bell, New York. 6. John Cohen, Harlem, New York<br />

City, 1954. Courtesy of the artist and Deborah Bell, New York.<br />

(continued on page 8)<br />

6 7