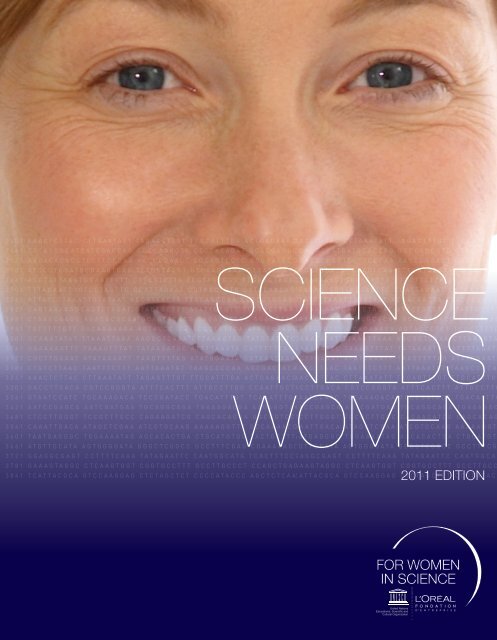

2011 EDITION

2011 EDITION

2011 EDITION

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

2401 AAACTCTTAC CTTAAATATT TAGAGTTTGT TTGCATTTGA ACTGAGAACG 2401 AAACTCTTAC TTTTGT CTTAAATATT TAGAGTTTGT TTGCATTTG<br />

2461 CTCAGGGCATGATGCACCAG GGCCAGGGTC CTCCACAGAT GCACCAGGGA 2461 CTCAGGGCATGATGCACCAG CATCCTGGCC<br />

GGCCAGGGTC CTCCACAG<br />

2521 AACACACGCCTCCTTCCCAA AACCCGAACT CGCAGTCCTC GGGGATGCCG 2521 AACACACGCCTCCTTCCCAA TCTCCACTGT<br />

AACCCGAACT CGCAGTCC<br />

SCIENCE<br />

2581 ATCCCTGGATGCGAAGTCAG TTTGGTAAGT GTCAAGGAAA GTGATCGACA 2581 ATCCCTGGATGCGAAGTCAG ATTCCACGAA<br />

TTTGGTAAGT GTCAAGGAA<br />

2641 ACGTATTAAGTGGAATTTTT CTTCTTCTTA TCGTAGTGGG TTGAAGTAGT 2641 ACGTATTAAGTGGAATTTTT TAGTTCCCCG<br />

CTTCTTCTTA TCGTAGTGGG<br />

2701 TTTAGAATTGGTCGTAGTTC CCATTAGAAT CGTAACTGTG CATACAACAG 2701 TTTAGAATTGGTCGTAGTTC CTAGAGCTGT<br />

CCATTAGAAT CGTAACTGTG<br />

2761 ATTATCTTAAATTGTATAAT ACCATAACTA TTACAGCGAA CCTCGTGCAG 2761 ATTATCTTAAATTGTATAAT CGAAGCAAAG<br />

ACCATAACTA TTACAGCGAA<br />

2821 CAGTAAAAAGCAGTCTAGAT GTACTGCTTT ATATTGTGTT TCCTGCTTGA 2821 CAGTAAAAAGCAGTCTAGAT TATTAGATCA<br />

GTACTGCTTT ATATTGTGTT<br />

2881 CTAAGCAAGC AGACGCGCAA GCAGTTCACG CAGATCACGC AGACGTTAAA 2881 CTAAGCAAGC AATTTAAAAA AGACGCGCAA GCAGTTCACG CAGATCAC<br />

2941 TGTTTTTGTT TGCAGAAAGA AGTACCCTCT TCGCTTTTCA ATTTTGTAGT 2941<br />

NEEDS<br />

TGTTTTTGTT TAAAATTCGA TGCAGAAAGA AGTACCCTCT TCGCTTTTC<br />

3001 GCAAATATAT TTAAATTAAA AAGGCTCAAA CTTAAAGTAC TATGTATGTC 3001 GCAAATATAT TTGTATTTTT TTAAATTAAA AAGGCTCAAA CTTAAAGTA<br />

3061 GAAAAAATTC TAAAGTTTAT TATAAAATGC ATTTTAAATA CATTTTTTAA 3061 GAAAAAATTC CCTACCTTGTTAAAGTTTAT<br />

TATAAAATGC ATTTTAAATA<br />

3121 CGCTTGAAAT ATATAAAATT TAAGTTTTAG ATATGGAATA GATAAACAAA 3121 CGCTTGAAAT ATATTTCCCT ATATAAAATT TAAGTTTTAG ATATGGAATA<br />

3181 CTGTCTTAAC TAATTTCTTT AATTAAATGT TAAGCCCCAA AGCGACTACA 3181 CTGTCTTAAC GCTTCATGTC TAATTTCTTT AATTAAATGT TAAGCCCCA<br />

3241 AAACTCTTAC CTTAAATATT TAGAGTTTGT TTGCATTTGA ACTGAGAACG 3241 AAACTCTTAC TTTTGTCGAC CTTAAATATT TAGAGTTTGT TTGCATTTG<br />

3301 GACCTTGACA CGTCCGGGTA ATTTCACTTT ATTGCCTTGG CCAATTGCTT 3301 GACCTTGACA GACATCATCC CGTCCGGGTA ATTTCACTTT ATTGCCTTG<br />

WOMEN<br />

3361 GTAATCCATC TGCAAAGACA TCCCGATACC TGACATTTGT TCAAATTTGC 3361 GTAATCCATC GAATTTCCCA TGCAAAGACA TCCCGATACC TGACATTTG<br />

3421 AATCCGAGCA AATCGATGAA TGCAGGCAGA TGAAAGACGA AAGAGGTGGC 3421 AATCCGAGCA GGAAGAGGTG AATCGATGAA TGCAGGCAGA TGAAAGAC<br />

3481 CTCCTTGGGT TCCGCTTGCC CAGAAGATCG CAGCACAGGA GGCGGTCCTG 3481 CTCCTTGGGT CCAGCTAATG TCCGCTTGCC CAGAAGATCG CAGCACAG<br />

3541 CAAATTGACA ATAGCTCGAA ATCGTGCAAG AAAAAGGTTT GCCAAAACCC 3541 CAAATTGACA TAGGCGTAAC ATAGCTCGAA ATCGTGCAAG AAAAAGGT<br />

3601 TAATGAGGGC TGGAAAATAG AGCACACTGA CTGCATGTGG TACTGCTTTA 3601 TAATGAGGGC GGCTTAGAGG TGGAAAATAG AGCACACTGA CTGCATGT<br />

3661 ATGTTGCATA AGTGGGGATA GGGCTCGGCC GCCTTTCGAG CGAAAAAGGT 3661 ATGTTGCATA GTAAGGTCTA AGTGGGGATA GGGCTCGGCC GCCTTTCG<br />

3721 GGAGGCGAGT CCTTTTCAAA TATAGAATTC CAATGGCATG TCACTTTCCT 3721 GGAGGCGAGT CGGAGAAAGT CCTTTTCAAA TATAGAATTC CAATGGCAT<br />

3781 GAAAGTAGGC CTCAAGTGGT CGGTGCCTTT GCCTTGCCCT CCAGCTGACC 3781 GAAAGTAGGC TGCTCCCTGG CTCAAGTGGT CGGTGCCTTT GCCTTGCC<br />

3841 TCATTACGCA GTCCAAGGAG CTCTAGCTCT CCCCATACCC AGCTCTCAAT 3841 TCATTACGCA GTTGTTGTGG GTCCAAGGAG CTCTAGCTCT <strong>2011</strong> <strong>EDITION</strong><br />

CCCCATAC<br />

3901 TTTTTTGTTT GTAGCCGGCT GAATTTTTTC GCCAAAGCCA GATTGAGATG 3901 TTTTTTGTTT TAAAGCACAA GTAGCCGGCT GAATTTTTTC GCCAAAGCC

P.4 - (c) Stéphane de Bourgies P. 5 - (c) UNESCO / Michel Ravassard, P. 8 - (c) Micheline Pelletier for the L’Oréal Corporate Foundation<br />

P. 9-19 - (c) V. Durruty & P. Guedj for the L’Oréal Corporate Foundation, P. 20 - (c) Christophe Guibbaud/Abacapress for the L’Oréal Corporate Foundation

SUMMARY<br />

04<br />

THE PROGRAMME<br />

08<br />

THE <strong>2011</strong> AWARD LAUREATES<br />

5 Women, 5 Outstanding Careers, 5 Major Contributions<br />

22<br />

THE <strong>2011</strong> INTERNATIONAL FELLOWSHIPS<br />

The Faces of Science for Tomorrow

4<br />

A SHARED<br />

COMMITMENT<br />

Béatrice<br />

Dautresme<br />

CEO, L’Oréal Corporate Foundation<br />

The L’Oréal-UNESCO For Women in Science<br />

programme, through thirteen years of<br />

commitment, has given recognition to over<br />

a thousand women scientists, providing<br />

visbility and encouragement for the excellence<br />

of their work, their contribution to scientific<br />

advancement and their impact on society.<br />

Our commitment began with a contradiction:<br />

even though women excelled at all levels<br />

of upper education, they were still poorly<br />

represented at the highest levels of scientific<br />

research.<br />

Through our long-term partnership with<br />

UNESCO, we are proud to shine a spotlight<br />

each year on outstanding women who have<br />

helped change the world through science.<br />

Faced with the mounting challenges of our<br />

century, it is more important than ever that we<br />

continue to lend them our support.<br />

Each year we celebrate scientists hailing from<br />

every continent who incarnate the promise of<br />

a better world. The science they personify is<br />

modern, cross-disciplinary and open to the<br />

world: science working on behalf of humanity,<br />

ceaselessly pushing back the frontiers of<br />

knowledge, transforming and improving<br />

our lives and providing solutions to the<br />

enormous challenges that face our planet.<br />

They address such urgent issues as aging<br />

populations, global warming, the extinction<br />

of species, access to water, fighting<br />

pandemics and harnessing energy.<br />

The year <strong>2011</strong> is resolutely turned towards<br />

the sciences: the UN has proclaimed it<br />

the International Year of Chemistry and we<br />

celebrate the centennial of Marie Curie’s<br />

Nobel Prize in Chemistry, which will be<br />

sponsored in part by the L’Oréal Corporate<br />

Foundation.<br />

This year, the programme welcomes for<br />

the first time scientists from such widelyspread<br />

countries as Estonia, Iraq, Panama<br />

and Sweden. For us, this ever broader<br />

community is a source of pride and<br />

ambition, which continues to motivate our<br />

cause year after year.

Gretchen<br />

Kalonji<br />

Assistant Director-General<br />

for Natural Sciences at UNESCO<br />

This year, we are honouring women and science.<br />

<strong>2011</strong> has been proclaimed the “International year<br />

of chemistry” by the United Nations. The launch<br />

ceremonies took place at UNESCO on 27 and 28<br />

January, at which scientists and politicians talked<br />

at length about chemistry’s essential contribution<br />

to knowledge, its importance in all aspects of our<br />

everyday lives and the crucial role it will play in<br />

sustainable development.<br />

For the first time in the history of international years,<br />

a plenary session was dedicated specifically to<br />

women’s contribution to science, honouring two-time<br />

Nobel Prize winner Marie Slodowska Curie and with<br />

a presentation by Ada Yonath, winner of the Nobel<br />

Prize in Chemistry in 2009 and laureate of the<br />

L’Oréal-UNESCO Award For Women in Science in<br />

2008. Promoting the role of women in chemistry is<br />

one of the four main aims of the International year<br />

of chemistry, with a number of events taking place<br />

around the world during the year on this theme.<br />

“Madame Curie” was celebrated again at the<br />

Sorbonne on 29 January on the occasion of the<br />

100th anniversary of the Nobel Prize for chemistry.<br />

The L’Oréal-UNESCO For Women in Science Award<br />

ceremony, held at UNESCO on 3 March, is a key part<br />

of this series of events, with five exceptional female<br />

scientists from five continents honoured for their<br />

contribution to advances in science. Two of them are<br />

eminent in the field of chemistry. And 15 fellowship<br />

winners, also from different parts of the world, will<br />

participate in the ceremony as well. Once again<br />

this year, but to a greater extent than usual,<br />

L’Oréal and UNESCO combine their efforts to<br />

spread the message summarising their mutual<br />

claim: “The world needs science and science<br />

needs women”.<br />

As the new Assistant Director-General for<br />

Natural Sciences at UNESCO and the first<br />

woman appointed to this important position, this<br />

message is particularly significant for me. With<br />

its prestigious awards and fellowships, the<br />

L’Oréal-UNESCO For Women in Science<br />

programme achieves goals that I would like to<br />

place at the heart of what we do: working to<br />

establish true equality between men and women<br />

in research and education, promoting diversified,<br />

shared and committed science in our time<br />

to young people, and increasing cooperation<br />

with universities and greater international<br />

cooperation, not forgetting one particular<br />

dimension that the L’Oréal-UNESCO partnership<br />

has been so successful in developing: solidarity.<br />

I am thinking in particular of the steps being<br />

taken with research scientists in Africa.<br />

May the <strong>2011</strong> L’Oréal-UNESCO Awards<br />

For Women In Science be a great celebration,<br />

and together we shall make the International<br />

Year of Chemistry a success.

6<br />

DECODING<br />

OUR WORLD<br />

VISIONARY<br />

AND PROMISING<br />

RESEARCH<br />

Harnessing solar energy, clean petrol production,<br />

water depollution, understanding the interreactions<br />

between light and matter and analysing the<br />

Universe are but some of the fields of research and<br />

contributions highlighted this year.<br />

Today’s Laureates and Fellows epitomise the<br />

commitment and ambition of the L’Oréal-UNESCO<br />

For Women in Science programme. This year we<br />

honour five women in the physical sciences. Their<br />

research demonstrates to what extent the socalled<br />

“hard” sciences, far from being hermetically<br />

closed, often provide us with concrete solutions to<br />

the enormous challenges facing society today.<br />

INTERCONNECTING<br />

SCIENTIFIC COMMUNITIES<br />

In a connected and globalised world, ever bigger and<br />

stronger bridges and ties are being forged between<br />

societies. These exchanges are what make innovation<br />

and scientific research possible, and help stimulate<br />

major discoveries.<br />

The L’Oréal Corporate Foundation and UNESCO<br />

have created a community of over a thousand women<br />

scientists, fostering exchanges and creating bridges<br />

between women researchers and students in the<br />

sciences, but also between disciplines, to help make<br />

science more open and less isolated.

A LONG-TERM<br />

COMMITMENT<br />

Every year, the L’Oréal Corporate Foundation and<br />

UNESCO renew their commitment to recognising<br />

the excellence of outstanding women, encouraging<br />

scientific careers and identifying and supporting<br />

future talent.<br />

By highlighting the advances that women scientists<br />

make possible day after day, the L’Oréal-UNESCO<br />

Awards For Women in Science help create female<br />

role models, paving the way for a whole new<br />

generation of young women scientists.<br />

In 2009, two L’Oréal-UNESCO For Women in<br />

Science Laureates were awarded Nobel prizes:<br />

Elizabeth Blackburn in Medecine and Ada Yonath<br />

in Chemistry. The merits of our programme are<br />

recognised in these two Nobel Awards.<br />

2401 AAACTCTTAC CTTAAATATT TAGAGTTTGT TTGCATTTGA<br />

2461 CTCAGGGCATGATGCACCAG GGCCAGGGTC CTCCACAGAT<br />

2521 AACACACGCCTCCTTCCCAA AACCCGAACT CGCAGTCCTC<br />

2581 ATCCCTGGATGCGAAGTCAG TTTGGTAAGT GTCAAGGAAA<br />

2641 ACGTATTAAGTGGAATTTTT CTTCTTCTTA TCGTAGTGGG T<br />

2701 TTTAGAATTGGTCGTAGTTC CCATTAGAAT CGTAACTGTG C<br />

2761 ATTATCTTAAATTGTATAAT ACCATAACTA TTACAGCGAA C<br />

Key figures:<br />

2821 CAGTAAAAAGCAGTCTAGAT GTACTGCTTT ATATTGTGTT T<br />

2881 CTAAGCAAGC L’OréaL-uNesCO AGACGCGCAA GCAGTTCACG fOr CAGATCACG<br />

2941 TGTTTTTGTT TGCAGAAAGA AGTACCCTCT TCGCTTTTCA<br />

WOmeN iN sCieNCe<br />

3001 GCAAATATAT TTAAATTAAA AAGGCTCAAA CTTAAAGTAC<br />

3061 GAAAAAATTC TAAAGTTTAT TATAAAATGC ATTTTAAATA<br />

3121 CGCTTGAAAT ATATAAAATT TAAGTTTTAG ATATGGAATA<br />

1086<br />

3181 CTGTCTTAAC TAATTTCTTT AATTAAATGT TAAGCCCCAA<br />

3241 AAACTCTTAC CTTAAATATT TAGAGTTTGT TTGCATTTGA<br />

3301 GACCTTGACA CGTCCGGGTA ATTTCACTTT ATTGCCTTGG<br />

3361 GTAATCCATC TGCAAAGACA TCCCGATACC TGACATTTGT<br />

3421 AATCCGAGCA AATCGATGAA TGCAGGCAGA TGAAAGACG<br />

women scientists<br />

3481 CTCCTTGGGT TCCGCTTGCC CAGAAGATCG CAGCACAGG<br />

3541 CAAATTGACA from across ATAGCTCGAA five continents<br />

ATCGTGCAAG AAAAAGGTTT<br />

3601 TAATGAGGGC TGGAAAATAG AGCACACTGA CTGCATGTGG<br />

have been recognised<br />

3661 ATGTTGCATA AGTGGGGATA GGGCTCGGCC GCCTTTCGAG<br />

3721 GGAGGCGAGT CCTTTTCAAA by the programme<br />

TATAGAATTC CAATGGCATG<br />

3781 GAAAGTAGGC CTCAAGTGGT CGGTGCCTTT GCCTTGCCCT<br />

3841 TCATTACGCA GTCCAAGGAG CTCTAGCTCT CCCCATACCC<br />

2401 3901 AAACTCTTAC TTTTTTGTTT CTTAAATATT GTAGCCGGCT TAGAGTTTGT GAATTTTTTC TTGCATTTGA GCCAAAGCCAA<br />

2461 CTCAGGGCATGATGCACCAG GGCCAGGGTC CTCCACAGAT<br />

2521<br />

in13<br />

AACACACGCCTCCTTCCCAA<br />

years<br />

AACCCGAACT CGCAGTCCTC<br />

2581 ATCCCTGGATGCGAAGTCAG TTTGGTAAGT GTCAAGGAAA<br />

2641 ACGTATTAAGTGGAATTTTT CTTCTTCTTA TCGTAGTGGG T<br />

2701 TTTAGAATTGGTCGTAGTTC CCATTAGAAT CGTAACTGTG C<br />

2761 ATTATCTTAAATTGTATAAT ACCATAACTA TTACAGCGAA C<br />

2821 CAGTAAAAAGCAGTCTAGAT GTACTGCTTT ATATTGTGTT T<br />

67 laureates<br />

2881 CTAAGCAAGC AGACGCGCAA GCAGTTCACG CAGATCACGC<br />

2941 TGTTTTTGTT TGCAGAAAGA AGTACCCTCT TCGCTTTTCA<br />

1019 fellows<br />

3001 GCAAATATAT TTAAATTAAA AAGGCTCAAA CTTAAAGTAC<br />

3061 GAAAAAATTC from TAAAGTTTAT 103 countries<br />

TATAAAATGC ATTTTAAATA C<br />

3121 CGCTTGAAAT ATATAAAATT TAAGTTTTAG ATATGGAATA G<br />

3181 CTGTCTTAAC TAATTTCTTT AATTAAATGT TAAGCCCCAA A<br />

3241 AAACTCTTAC CTTAAATATT TAGAGTTTGT TTGCATTTGA A<br />

3301 GACCTTGACA CGTCCGGGTA ATTTCACTTT ATTGCCTTGG<br />

<strong>2011</strong><br />

3361 GTAATCCATC TGCAAAGACA TCCCGATACC TGACATTTGT<br />

3421 AATCCGAGCA AATCGATGAA TGCAGGCAGA TGAAAGACGA<br />

3481 CTCCTTGGGT TCCGCTTGCC CAGAAGATCG CAGCACAGGA<br />

In 3541 CAAATTGACA ATAGCTCGAA ATCGTGCAAG AAAAAGGTTT<br />

3601 TAATGAGGGC TGGAAAATAG 4 new AGCACACTGA countries: CTGCATGTGG<br />

3661 ATGTTGCATA AGTGGGGATA GGGCTCGGCC GCCTTTCGAG<br />

3721 GGAGGCGAGT CCTTTTCAAA Estonia<br />

TATAGAATTC CAATGGCATG<br />

3781 GAAAGTAGGC CTCAAGTGGT CGGTGCCTTT GCCTTGCCCT<br />

3841 TCATTACGCA GTCCAAGGAG CTCTAGCTCT Iraq CCCCATACCC<br />

3901 2401 TTTTTTGTTT AAACTCTTAC GTAGCCGGCT CTTAAATATT GAATTTTTTC TAGAGTTTGT GCCAAAGCCA<br />

TTGCATTTGA<br />

Panama<br />

2461 CTCAGGGCATGATGCACCAG GGCCAGGGTC CTCCACAGAT<br />

2521 AACACACGCCTCCTTCCCAA AACCCGAACT CGCAGTCCTC<br />

Sweden<br />

2581 ATCCCTGGATGCGAAGTCAG TTTGGTAAGT GTCAAGGAAA<br />

2641 ACGTATTAAGTGGAATTTTT CTTCTTCTTA TCGTAGTGGG<br />

2701 TTTAGAATTGGTCGTAGTTC CCATTAGAAT CGTAACTGTG<br />

2761 ATTATCTTAAATTGTATAAT ACCATAACTA TTACAGCGAA C<br />

2821 CAGTAAAAAGCAGTCTAGAT GTACTGCTTT ATATTGTGTT<br />

2881 CTAAGCAAGC AGACGCGCAA GCAGTTCACG CAGATCACG<br />

2941 TGTTTTTGTT TGCAGAAAGA AGTACCCTCT TCGCTTTTCA<br />

3001 GCAAATATAT TTAAATTAAA AAGGCTCAAA CTTAAAGTAC<br />

3061 GAAAAAATTC TAAAGTTTAT TATAAAATGC ATTTTAAATA<br />

3121 CGCTTGAAAT ATATAAAATT TAAGTTTTAG ATATGGAATA<br />

3181 CTGTCTTAAC TAATTTCTTT AATTAAATGT TAAGCCCCAA

8<br />

THE <strong>2011</strong><br />

LAUREATES<br />

5 Women<br />

5 Outstanding Careers<br />

5 Major Contributions<br />

THE <strong>2011</strong> LAUREATES AS SEEN<br />

bY THE PRESIDENT OF THE JURY<br />

Pr. Ahmed Zewail<br />

Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1999<br />

Through the L’Oréal-UNESCO Awards For Women in Science, the<br />

international jury strives to shed light on the infinite possibilities<br />

offered by science each year. The 15 members of the international<br />

jury were selected on their scientific merit and their commitment to<br />

women scientists.<br />

To select the Laureates, we examine their scientific achievements<br />

and the international contribution of their research, notably through<br />

their publications and peer reviews.<br />

Identifying Laureates in the emerging countries is truly challenging.<br />

In certain regions of the world, the difficulty of identifying women<br />

scientists is symptomatic of the conditions women face to access<br />

education and the sciences. This is why it is vital that we pursue our<br />

mission. Each year, L’Oréal and UNESCO renew their commitment<br />

and send out a call for nominations to over 1000 eminent scientists<br />

on every continent.<br />

In <strong>2011</strong>, we are proud to have selected a group of Laureates<br />

marked by diversity. Far from sharing the same research themes,<br />

the Laureates’ work is characterised by variety and interdisciplinarity

touching on all areas of the physical sciences, from<br />

nanoscience to the environmental sciences and cosmology. In<br />

our eyes, they represent a veritable wealth of knowledge that<br />

opens the door to infinite possibilities!<br />

Although I believe that science is currently doing rather well,<br />

I sometimes have doubts about financing mechanisms and<br />

new trends that could erode curiosity and creativity. Yet I am<br />

still optimistic about the future of science and thus the world,<br />

because it is my deep-felt conviction that human beings can<br />

adapt to anything.<br />

An international award like L’Oréal-UNESCO For Women<br />

in Science helps increase awareness of the role women<br />

scientists play in finding solutions for planetary issues. It<br />

seems the best way to reach absolute gender parity in<br />

scientific research is to perpetuate successful role models<br />

through innumerable awards and scholarships, and to give life<br />

to an influential community.<br />

PR. FAIZA<br />

AL-KHARAFI<br />

Laureate for Africa<br />

and the Arab States<br />

PR. SILVIA<br />

TORRES-PEIMBERT<br />

Laureate for Latin America<br />

PR. JILLIAN<br />

BANFIELD<br />

Laureate for North America<br />

PR. VIVIAN<br />

WINg-WAH YAM<br />

Laureate for Asia<br />

and the Pacific<br />

PR. ANNE<br />

L’HUILLIER<br />

Laureate for Europe

10<br />

PR. FAIZA<br />

AL-KHARAFI<br />

Kuwait University, Safat, KUWAIT<br />

Laureate for Africa and the Arab States<br />

Fight Corrosion<br />

Corrosion is a natural process: metals react to oxygen in the<br />

air and are paradoxically vulnerable to their environment.<br />

Less well known, corrosion also affects all machinery made<br />

from iron or steel. The cost of corrosion is estimated at about<br />

2% of world gDP. Every second, roughly 5 tonnes of steel are<br />

transformed into rust! This explains why corrosion is such a<br />

big concern for mining, agriculture and heavy industry.<br />

Professor Faiza Al-Kharafi has spent her career investigating<br />

the mechanisms underlying the corrosion of metals and<br />

finding practical solutions to inhibit the process. Her work has<br />

had a major impact on the development of the energy sector<br />

in Kuwait as well as on improving water treatment.<br />

Founder of the first Corrosion and Electrochemistry Research<br />

Laboratory at Kuwait University in 1967, she has devoted her<br />

research to the study of copper and platinum, two metals<br />

widely used in many important industrial processes.<br />

Responding to an<br />

Environmental Issue<br />

Corrosion, the most common example of which is rust,<br />

is the permanent and generally undesirable change in<br />

metal when it reacts with its environment. But sometimes<br />

a metal can actually speed up a chemical reaction and<br />

remain unchanged itself. This is called catalysis, and it<br />

is extremely important in many industrial applications.<br />

Platinum, for example, interacts with numerous<br />

molecules making it an extremely valuable catalyst.<br />

A specialist in platinum, Faiza Al-Kharafi naturally zeroed<br />

in on this property, especially since platinum catalysts are<br />

widely used in oil refining to increase the octane rating of<br />

gasoline, such as the SP 95 and SP 98 fuels commonly<br />

found in service stations. Yet metal catalysts like platinum<br />

also generate side reactions that can produce harmful<br />

components such as benzene, which is carcinogenic.<br />

Faiza Al-Kharafi and her team discovered a new class<br />

of catalysts based on the element molybdenum, which<br />

does not have the secondary reactions of platinum and<br />

can be used to increase the octane number of gasoline

For her work on corrosion,<br />

a problem of fundamental importance<br />

to water treatment and<br />

the oil industry<br />

without producing benzene. This was a veritable revolution for<br />

the refining industry, reducing costs and making it safer for<br />

refinery workers, the environment and the general public. It<br />

was also a major advance for water treatment, since this new<br />

class of catalyst can also be used to extract certain pollutants<br />

from drinking water.<br />

A Career in Chemistry<br />

After earning a BSc degree from Ain Shams University in<br />

Egypt, Faiza Al-Kharafi received her MSc and PhD from<br />

Kuwait University, where she joined the faculty in 1967.<br />

From 1993 to 2002 she served as head of the Chemistry<br />

Department, Dean of the Faculty of Science and President<br />

of the University, becoming the first woman to head a major<br />

university in the Arab world. In 2002, she left her university<br />

post to serve on the Kuwaiti government’s Supreme Council<br />

of Planning and Development.<br />

Professor Al-Kharafi has greatly contributed to the promotion<br />

of science in Kuwait. She has been the research director for<br />

over twenty research projects in corrosion and has facilitated<br />

fruitful international collaborations between Kuwait University<br />

and other universities in France and around the world. She is<br />

a member of the United Nations University Council and Vice<br />

President of The Academy of Sciences for the Developing<br />

World.<br />

FAIZA<br />

AL-KHARAFI<br />

IN HER OWN<br />

WORDS<br />

EXEMPLARY DEDICATION<br />

Faiza Al-Kharafi has been committed<br />

to science since a young age.<br />

She went on to become a leading<br />

scientific figure in Kuwait, experiencing<br />

first-hand women’s contribution<br />

to the development of science<br />

and their strong commitment. As<br />

president of Kuwait University from<br />

1993 to 2002, she was in charge<br />

of 1,500 staff members, more than<br />

5000 employees and more than<br />

20,000 students annually. Today,<br />

she emphasises the important role<br />

women play in scientific research.<br />

“In the Faculty of Science at Kuwait<br />

University, more than 40 percent<br />

of the staff members and students<br />

are female. Their contribution to the<br />

development of science in general<br />

is very important.”<br />

A WOMAN WHO ACCEPTS<br />

CHALLENgES<br />

Throughout her career, Faiza<br />

Al-Kharafi has noted how “many<br />

people underestimated the abilities<br />

of women in science,” she explains.<br />

“Another big challenge was finding<br />

the right balance between my work<br />

and raising my children. By hard<br />

work, dedication and commitment,<br />

and also thanks to time management<br />

and family help,” she says,<br />

she was able to succeed at this<br />

difficult juggling act.<br />

Professor Al-Kharafi is extremely<br />

pleased to receive this award that<br />

promotes the cause of women<br />

scientists. “I very much hope that<br />

this prize will encourage young<br />

people – especially girls – to<br />

specialise in scientific fields and be<br />

more involved and committed to<br />

the development of society.”

12<br />

PR. SILVIA<br />

TORRES-<br />

PEIMBERT<br />

University of Mexico (UNAM), Mexico City, MExICO<br />

Laureate for Latin America<br />

Nebulae: Birthplaces and<br />

Graveyards of Stars<br />

There are more stars in the Universe than grains of sand on<br />

Earth, and our galaxy alone has more than 200 billion stars!<br />

These staggering figures explain the interest and difficulties in<br />

studying these distant suns.<br />

Like humans, stars are not eternal: they are born, grow old<br />

and die. The major events in the life cycle of a star take place<br />

in the nebulae, the regions of the universe with a high density<br />

of hydrogen and helium gas, dust, and other gases. Specific<br />

nebulae called HII regions serve as birthplaces for new stars,<br />

while planetary nebulae are produced by the death of stars,<br />

which explode or run out of fuel.<br />

Professor Torres-Peimbert has devoted her career to<br />

decoding nebulae, and her work provides scientists with<br />

valuable insights into the origins of stars and the evolution of<br />

the universe.<br />

Starlight: a Look Back in Time<br />

The chemical composition of a nebula, which can be<br />

determined by analyzing its light spectrum, contains<br />

the history of the nuclear transformations that have<br />

occurred within a star, and can be used to understand<br />

the events of its life cycle.<br />

Very early on, Professor Torres-Peimbert took an<br />

interest in the Orion Nebula, which contains hundreds<br />

of stars at various stages of development. In 1977,<br />

she published the first complete analysis of the<br />

composition of this nebula, which showed that it is<br />

chemically very similar to our own Sun.<br />

By observing the planetary nebulae from numerous<br />

galaxies, she has helped understand the beginning of<br />

the universe when the first stars were born nearly 14<br />

billion years ago. She also provided new insight into<br />

the stellar aging process.

For her work on the chemical<br />

composition of nebulae which is<br />

fundamental to our understanding<br />

of the origin of the universe<br />

The Future of the Universe<br />

In the first three minutes following the Big Bang, the only<br />

elements produced in abundance were hydrogen and helium.<br />

The other elements were created later via fusion processes<br />

inside stars. The respective quantity of helium and hydrogen in<br />

the early universe is extremely important because it can help<br />

shape our understanding of the first moments of the universe.<br />

By studying the Large Magellanic Cloud, the brightest HII<br />

region visible from Earth, and the Orion Nebula, Professor<br />

Torres-Peimbert and her colleagues were the first to establish<br />

differences in helium abundance among nebulae from different<br />

galaxies. According to their research, the amount of helium<br />

in the universe has increased throughout its evolution, which<br />

could shed new light on the future of the universe.<br />

At this early stage of the 21st century, Silvia Torres-Peimbert is<br />

at the leading edge of research on the very first generations of<br />

stars and galaxies, which remain one of the major mysteries of<br />

astronomical research.<br />

Sharing Stars<br />

with the Whole World<br />

Professor Torres-Peimbert received her bachelor’s degree at<br />

the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) and<br />

her PhD in Astronomy at the University of California - Berkeley.<br />

She has been a professor in the Faculty of Sciences at UNAM<br />

since 1972 and a professor in the Institute of Astronomy since<br />

1976.<br />

She has received several awards from the Mexican Physical<br />

Society, the National University of Mexico, and other national<br />

and international organizations including the guillaume Budé<br />

Medal from the Collège de France. She is a member of the<br />

American Astronomical Society, the Astronomical Society<br />

of the Pacific, TWAS, The Academy of Sciences for the<br />

Developing World and Vice President of the International<br />

Astronomical Union.<br />

She has been chief editor of a scientific journal and has<br />

delivered more than 250 talks for the general public. She also<br />

produces TV and radio shows designed to popularise science.<br />

SILVIA TORRES-<br />

PEIMBERT<br />

IN HER OWN<br />

WORDS<br />

PASSION BEATS TRADITION<br />

“When I was a student,” she pointed<br />

out, “women in Mexico were not<br />

expected to have a career”. Although<br />

her family was supportive throughout<br />

her studies, she still remembers the<br />

feeling of being at cross purposes with<br />

the principles of traditional education.<br />

That is why she also insists on the<br />

need to promote “deeper changes<br />

in the attitudes of men and women<br />

starting early in life.”<br />

TEACHINg NEW ATTITUDES<br />

TO OUR CHILDREN<br />

“The main challenges I had to overcome<br />

were my own expectations of<br />

the role of women in society. At several<br />

stages in my life, I had to stop and<br />

reflect on my real interests, in order to<br />

prioritize my activities,” she explains,<br />

adding that when she looks back on<br />

her choices, she is “very glad to have<br />

been so defensive of my career.”<br />

For future generations, she emphasizes<br />

the need to instil new attitudes as early<br />

as possible: “Significant differences in<br />

attitudes are taught to boys and girls<br />

at an early age, and are very difficult to<br />

discard later in life.”<br />

ACCOMPLISHINg MORE<br />

AND BETTER WITH LESS<br />

Scientists in the developing countries<br />

must deal with additional hardships,<br />

such as “carrying out competitive<br />

research with fewer resources and<br />

outdated equipment.” With fewer<br />

scientists per capita and only a small<br />

share of GDP invested in science, the<br />

developing countries have a real need<br />

for scientists.

14<br />

PR. JILLIAN<br />

BANFIELD<br />

University of California, Berkeley, USA<br />

Laureate for North America<br />

Between Life and Matter<br />

Among the indispensable elements for the creation of living<br />

matter are air, water, phosphorus, calcium, magnesium, iron,<br />

copper and zinc. Yet one thing is missing: without the help<br />

of microorganisms, these elements cannot be assimilated by<br />

more complex living organisms. Microorganisms transform<br />

phosphorus into phosphate, sulphur into sulphate, etc.<br />

Consequently, life can arise where living bacteria encounter<br />

bits of matter. Even more surprising, we now know that the<br />

biological disintegration of rocks in the outer layer of the Earth<br />

is essential for maintaining life on our planet.<br />

Professor Jillian Banfield has specialised in the association of<br />

minerals and microscopic forms of life, two areas of science<br />

that at first glance appear to have little in common. From her<br />

unique vantage point at the interface of these fields, she has<br />

revealed rich secrets about their fundamental interactions. She<br />

has even proven that microorganisms have the capacity to<br />

influence large-scale geological processes like erosion, and to<br />

construct unique materials from molecular building blocks.<br />

Bordering between the physical and biological worlds,<br />

these microorganisms can no longer be dissociated from<br />

their natural environments.<br />

What if Evidence of Life<br />

Was Recorded in Minerals?<br />

This would help answer a key question in space<br />

exploration: now that we have found water, could there<br />

be life on Mars? Astrobiology, also called exobiology, the<br />

study of life in the universe, is another one of Professor<br />

Banfield’s projects. She has demonstrated how the kinds<br />

of biological processes necessary for life can result in the<br />

production of unique crystalline materials that provide a<br />

“signature” for life, serving as evidence that<br />

microorganisms once inhabited a particular environment.

For her work on bacterial and<br />

material behaviour under<br />

extreme conditions relevant to<br />

the environment and the Earth<br />

Life Survives even under<br />

the Harshest Conditions<br />

By studying the interactions of microorganisms in extreme<br />

environments such as ore deposits, Jillian Banfield has shown<br />

how they have adapted to hostile conditions. She elucidated<br />

the mechanisms by which these organisms produce energy<br />

and obtain essential nutrients from metal sulphide ore.<br />

She also revealed how certain bacteria contribute to the<br />

acidification process that occurs in these mines, producing<br />

toxic wastewater that can pollute groundwater, which was<br />

previously attributed to a spontaneous chemical reaction.<br />

Once again, the physical and biological components of the<br />

terrestrial ecosystem are not isolated from each other.<br />

Professor Banfield and her students have sequenced the<br />

genomes of the different species within this community and<br />

catalogued the proteins they produce, fully characterizing this<br />

unique microbial ecosystem. Their work has improved our<br />

understanding of how life survives in even the most unlikely<br />

places.<br />

A Career Devoted<br />

to Bio-Geo-Chemistry<br />

Jillian Banfield received her bachelor’s and master’s degrees in<br />

geology from the Australian National University. She completed a<br />

PhD in Earth and Planetary Science at Johns Hopkins University<br />

in 1990. From 1990-2001 she was a professor in the geology<br />

and geophysics Department and in the Materials Science<br />

Program at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Since then she<br />

has been a professor in the Materials Science Department and<br />

the Earth and Planetary Science Department at the University<br />

of California-Berkeley and an affiliate scientist at the Lawrence<br />

Berkeley National Laboratory.<br />

Professor Banfield has been honoured with numerous<br />

prestigious awards, including a MacArthur Fellowship (1999-<br />

2004), the Dana Medal of the Mineralogical Society of America<br />

(2010), and a John Simon guggenheim Foundation Fellowship<br />

(2000). She was elected to the U.S. National Academy of<br />

Sciences in 2006.<br />

JILLIAN<br />

BANFIELD<br />

IN HER OWN<br />

WORDS<br />

INTERCONNECTIVITY<br />

AS A SOURCE OF HOPE<br />

If she were allowed just one word<br />

to describe what she hopes to<br />

contribute to the world of research,<br />

Jillian Banfield would choose<br />

“interconnectivity” – perhaps her way<br />

of saying that nothing happens in a<br />

vacuum. In a world where actions<br />

and reactions are interrelated, her<br />

research underscores how each<br />

phenomenon influences and is<br />

influenced by others and thus the<br />

importance of interconnectivity.<br />

“I have a lot of hope that science<br />

can provide answers, such as new<br />

sustainable technologies, innovative<br />

medical treatments, strategies for<br />

carbon sequestration, etc.”<br />

URgENT NEED FOR<br />

SUSTAINABLE LIFESTYLES<br />

From her interdisciplinary<br />

perspective, Professor Banfield<br />

places a premium on sustainability.<br />

“We are changing the biosphere in a<br />

complex manner with unpredictable<br />

results. Finding ways to live<br />

sustainably within our environment,<br />

without destroying it, seems to me to<br />

be the most urgent challenge facing<br />

our planet today.”<br />

THE VALUE OF WOMEN’S<br />

PERSPECTIVE IN SCIENCE<br />

Professor Banfield welcomes the<br />

movement in recent decades to<br />

facilitate the access to scientific<br />

careers for women. She also<br />

recognises the value of women’s<br />

perspective in science: “It seems<br />

clear to me from personal experience<br />

that women approach problems<br />

differently from men. I suspect that<br />

women tend to see things more<br />

holistically and be less forceful in the<br />

ways in which they offer opinions.”

16<br />

PR. VIVIAN<br />

WING-WAH<br />

YAM<br />

Hong Kong University, CHINA<br />

Laureate for Asia and the Pacific<br />

The Sun: a Free, Unlimited Source<br />

of Energy that is Largely Wasted<br />

There are several renewable and sustainable energy solutions<br />

like solar power, which could provide an unlimited source of<br />

energy. Yet a few obstacles must still be resolved, such as<br />

the low efficiency of solar cells and their high supply costs.<br />

Currently, efficiency is low because these solar cells capture<br />

only some parts of light. The most efficient solar cells today<br />

are made from silicon crystals, are very expensive to produce<br />

and are able to convert around 30 percent of the solar energy<br />

they absorb. Clearly, this is a vital challenge for the future of<br />

our technological and industrial societies and thus for humanity<br />

as a whole.<br />

In Search of the Holy Grail:<br />

New Materials<br />

By developing and testing new and photoactive materials,<br />

Professor Yam and her colleagues hope to overcome these<br />

limits. We can now envision innovative photoactive materials<br />

based on organometallics with new properties by combining<br />

components associating metal atoms and organic<br />

molecules that absorb or emit light in an optimum<br />

manner. Professor Yam has focused her attention on<br />

this class of versatile photoactive materials. Depending<br />

on the type of metal at the core of the complex and the<br />

nature of the surrounding organic molecule, photoactive<br />

materials can absorb and emit light at a range of different<br />

wavelengths and efficiencies. Her research has led to the<br />

discovery of several materials with unique light absorption<br />

properties that may prove useful for harnessing solar<br />

energy.<br />

We can imagine imitating a well-known natural photochemical<br />

process, the photosynthesis of plants, which<br />

has been transforming sunlight into energy on Earth for<br />

billions of years.<br />

Professor Vivian Yam has spent years investigating<br />

methods to develop photoactive materials capable of<br />

absorbing light energy in their chemical bonds and then<br />

to convert it into electrical energy.

For her work on light-emitting<br />

materials and innovative ways<br />

of capturing solar energy<br />

In recent years, chemists have also focused their research<br />

on physio-chemical transformations triggered by light to<br />

better understand this phenomenon and to take advantage<br />

of light-molecule interactions. The idea is to design electronic<br />

“communication” pathways by constructing nanometric<br />

complexes using organic molecules, which when brought into<br />

the presence of metal atoms, assemble themselves into organometallic<br />

molecular structures.<br />

In molecular electronics, Professor Yam has also tested the<br />

capacity of organic and organometallic systems to transfer or<br />

process information. Her work shows that these molecules<br />

can serve as molecular junctions because they act like electric<br />

wires.<br />

From Oil Spills to Medicine<br />

The photoactive materials developed by Professor Yam have<br />

far more applications than just solar energy. Many technologies<br />

we use daily rely on photoactive materials, such as<br />

organic light-emitting diode displays (OLED). The discovery<br />

and development of materials for efficient white organic lightemitting<br />

diodes (WOLEDs) will also have a huge impact to<br />

meet the challenge towards the launching of a more efficient<br />

solid-state lighting system as lighting currently takes up about<br />

19 % of the global power. Yet, biology is probably one of its<br />

most spectacular fields of application. By emitting light when<br />

exposed to oil or heavy metal ions, for example, these materials<br />

could be used to detect environmental hazards such as<br />

an oil spill or radioactive contamination. In healthcare, photoactive<br />

materials could also serve as chemosensors, detecting<br />

glucose in the blood of diabetics or the presence of malignant<br />

cells.<br />

The Youngest Member of the<br />

Chinese Academy of Sciences<br />

Professor Yam received her bachelor’s and PhD degrees from<br />

the University of Hong Kong. She taught at City Polytechnic<br />

of Hong Kong before joining the University of Hong Kong as<br />

a faculty member. She has served as the Chair Professor of<br />

Chemistry since 1999 and headed the chemistry department<br />

for the two terms from 2000 to 2005.<br />

At age 38, she was the youngest member ever elected to the<br />

Chinese Academy of Sciences. She is also a Fellow of TWAS,<br />

the Academy of Sciences for the Developing World, and<br />

was awarded the State Natural Science Award and the RSC<br />

Centenary Medal.<br />

VIVIAN WINg-<br />

WAH YAM<br />

IN HER OWN<br />

WORDS<br />

NO gENDER DIFFERENCE<br />

IN SCIENCE<br />

“I do not think there is a difference between<br />

men and women in terms of their intellectual<br />

ability and research capabilities. As<br />

long as one has the passion, dedication<br />

and determination to pursue research<br />

wholeheartedly, one can excel regardless<br />

of one’s gender or background.”<br />

She concedes, however, that women<br />

may still feel discouraged about pursuing<br />

science. “Many young women are still<br />

worried about the barriers they might face<br />

in their careers posed by possible gender<br />

stigmas. This is particularly prevalent in<br />

Asian countries, and even in major modernised<br />

cities like Hong Kong, albeit globalised,<br />

where conventional or even biased<br />

Chinese values still prevail.”<br />

CHEMISTS ARE ARTISTS<br />

Professor Vivian Wing-Wah Yam describes<br />

the boundless possibilities of chemistry and<br />

the beauty of this discipline. “One of the<br />

beauties of chemistry is the ability to create<br />

new molecules and chemical species. I<br />

have always associated chemists with<br />

artists, creating new things with innovative<br />

ideas,” affirms Professor Yam. She<br />

also points out the interdisciplinarity of<br />

research which can lie at the crossroads<br />

of chemistry, physics and engineering<br />

to respond to energy and environmental<br />

challenges, or at the junction of chemistry<br />

and medicine for the development of new<br />

biomedical applications.<br />

ENERgY, THE CHALLENgE<br />

OF THE CENTURY<br />

Alternative sources of clean, renewable<br />

energy, are a top priority because they<br />

are linked to several other key issues like<br />

water scarcity, global warming and climate<br />

change. “There are many challenges facing<br />

our planet today, including food and healthcare.<br />

However, I believe energy is the most<br />

urgent challenge because once it is solved,<br />

it will have a positive impact on the others,<br />

since they are all interconnected in one way<br />

or another. Everything is linked to our everincreasing<br />

demand for energy!”

18<br />

PR. ANNE<br />

L’HUILLIER<br />

Lund University, SWEDEN<br />

Laureate for Europe<br />

The Fastest Cameras ever made<br />

To capture the movement of an electron in an atom, you<br />

need a “camera” with a shutter speed of a billionth of a<br />

billionth of a second. We have now entered the timescale<br />

of the attosecond, which is to the second what the second<br />

is to the age of the universe, estimated at about 13.7 billion<br />

years.<br />

For a long time, most of the extremely fast molecular events<br />

that form the basis of important natural phenomena like<br />

photosynthesis or of technological devices like microchips<br />

were invisible to experimental science, simply because we<br />

did not have the ability to capture events on such short<br />

timescales. Thanks to the research of Professor Anne<br />

L’Huillier and other scientists, we have developed the tools<br />

to study the ultrafast processes that form the foundation<br />

for most of our observations of the natural world.<br />

The Key to Ultrafast Pulses<br />

generating ultrafast light pulses is no easy task. The<br />

laws of physics dictate that an extremely short pulse of<br />

light will be a mixture of many different wavelengths; in<br />

physics parlance, it has a large bandwidth. For years,<br />

the problem of obtaining such a large bandwidth<br />

represented a major roadblock to ultrafast science.<br />

At the end of the 1980s, however, Anne L’Huillier, then<br />

a young researcher at the Centre d’Etudes de Saclay<br />

in France, stumbled onto the solution to this problem.<br />

By focusing an intense pulse of laser light into a gas,<br />

high-order harmonics of the laser light – similar to the<br />

harmonics of a musical instrument – were generated<br />

and light of the appropriate bandwidth was obtained.<br />

Since the mid-1990s, Anne L’Huillier and her<br />

colleagues have continued to study these processes<br />

from a theoretical and experimental perspective in<br />

Lund, Sweden.

For her work on the development<br />

of the fastest camera for recording<br />

the movement of electrons in attoseconds<br />

(a billionth of a billionth of a second) DARE TO DO RESEARCH<br />

The Potential of the Attosecond<br />

Attosecond physics has emerged as one of the most<br />

promising areas in atomic and molecular science.<br />

Technologies based on attosecond pulses could allow us to<br />

observe the movement of electrons in atoms and molecules<br />

in real-time, enhancing our understanding of the structure of<br />

matter and its interaction with light.<br />

A Career Evolving<br />

at the Speed of Light<br />

Anne L’Huillier was born in Paris and pursued her<br />

undergraduate studies at the Ecole Normale Supérieure,<br />

majoring in mathematics and physics. She received her PhD<br />

in Physics at the University of Paris VI in 1986, performing<br />

her research at the French Atomic Energy Commission and<br />

Centre d’Etudes de Saclay. She completed her postdoctoral<br />

work in Sweden and the United States. She was a researcher<br />

for the Service des Photons, Atomes and Molécules (SPAM),<br />

Centre d’Etudes de Saclay from 1986 to 1995.<br />

In 1995, Anne L’Huillier moved to Sweden to be a lecturer in<br />

the physics department of Lund University and was named<br />

professor in 1997. She has been honoured with early-career<br />

awards from the French Physics Society and the Royal<br />

Swedish Academy of Sciences, and more recently, the Julius<br />

Springer Prize for Applied Physics (together with Professor<br />

Ferenc Krausz).<br />

She has been a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of<br />

Sciences since 2004 and was awarded an ERC Advanced<br />

Research grant from the European Research Council in 2008.<br />

ANNE<br />

L’HUILLIER<br />

IN HER OWN<br />

WORDS<br />

“To be a researcher and a professor<br />

is a fantastic profession,” says Anne<br />

L’Huillier, but adds, “I’m quite sure<br />

there are many women who can do it<br />

but maybe don’t dare”. As she sees<br />

it, many are discouraged by the way<br />

research is organised and the structure<br />

of the university system in many<br />

countries. She also believes “the<br />

heart of the problem comes much<br />

earlier, at school and in families.<br />

Young girls need to understand they<br />

can also do science if they want to.<br />

Their families and teachers – society<br />

as a whole – all need to convey this<br />

message.”<br />

She also adds that in terms of<br />

leadership, women might have a<br />

different approach that can make a<br />

difference. “Generally speaking, a<br />

group works so much better when<br />

there is gender balance. This is true<br />

at a group level and at the level of a<br />

scientific community.”<br />

SCIENCE MEANS RIgOROUS<br />

SELF-DISCIPLINE BUT ALSO<br />

BEINg OPEN WITH OTHERS<br />

In her approach to research,<br />

Professor L’Huillier considers<br />

that how one does science is as<br />

important as what one investigates.<br />

When pressed to choose just one<br />

word to describe what she hopes her<br />

scientific contribution will represent,<br />

she hesitates before answering:<br />

“‘Rigorous’ is the word I can come<br />

up with. Combining experimentation<br />

and theory, and trying to go as<br />

deeply as possible is the way I like to<br />

think about what I’m doing. Sharing<br />

and discussing ideas with other<br />

people, colleagues and students is<br />

also very important for research to be<br />

successful.”<br />

A SENSE OF SHARINg<br />

AND LISTENINg<br />

When Professor L’Huillier arrived in<br />

Sweden in 1995 she discovered her<br />

passion for teaching, which has not<br />

abated for the past 15 years:<br />

“I found that teaching brought me<br />

something I had been missing from<br />

my profession as a researcher,<br />

something more concrete and useful!<br />

I hope my way of teaching will have<br />

an impact on my students and<br />

influence the way they learn science.”

20<br />

INTERNATIONAL<br />

JURY <strong>2011</strong><br />

L’ORÉAL-UNESCO AWARDS, PhySiCAL SCiENCES<br />

(PhySiCS AND ChEMiSTRy)<br />

From left to right, 1 st row : Pr. J. King, Pr. M. Brimble, Pr. B. Barbuy, Pr. J. Ragai<br />

2 nd row : Pr. C. de Duve, Pr. A. Robledo, Pr. W. Winnick, Pr. S. Canuto, Pr. G. Ogunmola, Pr. A. Zewail<br />

3 rd row : Dr. L. Gilbert, Pr. H.E. Stanley, Pr. M. Maaza, Pr. M. Chergui, Pr. C. Amatore, Pr. C-L. Bai.

President of the Jury<br />

Professor Ahmed ZeWAiL<br />

Nobel Prize in Chemistry, 1999<br />

California Institute of Technology, CA, USA<br />

founding President<br />

Professor Christian de duVe<br />

Nobel Prize in Medicine, 1974<br />

Institut de Pathologie Cellulaire, BELGIUM<br />

honorAry President<br />

irina BoKoVA<br />

Director-General, UNESCO<br />

AfriCA And ArAB stAtes<br />

Professor Jehane rAgAi<br />

Department of Chemistry, School of Sciences and Engineering,<br />

The American University in Cairo (AUC), EGYPT<br />

Professor gabriel ogunMoLA (for l’UNESCO)<br />

Chairman, Board of Trustees, and Chancellor, Lead City University, Ibadan,<br />

Chairman, Institute of Genetic Chemistry & Laboratory of Medicine, Ibadan, NIGERIA<br />

Professor Malik MAAZA<br />

iThemba LABS-National Research Foundation of South Africa, Somerset West,<br />

Western Cape Province, SOUTH AFRICA<br />

AsiA - PACifiC<br />

Professor Chun-Li BAi<br />

Executive Vice President and President of the Graduate University,<br />

Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, CHINA<br />

Professor Margaret BriMBLe (Laureate 2007)<br />

Chair of Organic and Medicinal Chemistry, University of Auckland, Auckland, NEW ZEALAND<br />

euroPe<br />

Professor Christian AMAtore<br />

Département de Chimie, Ecole Normale Supérieure, Paris, FRANCE<br />

Professor Majed Chergui<br />

Professor of Physics and Chemistry, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology<br />

Honorary Professor, University of Lausanne, SWITZERLAND<br />

Professor Julia King<br />

Vice Chancellor, Aston University, Birmingham, UNITED KINGDOM<br />

doctor Laurent giLBert (for L’OREAL)<br />

Director, International Development of Advanced Research, L’Oréal FRANCE<br />

LAtin AMeriCA<br />

Professor Beatriz BArBuy (Laureate 2009)<br />

Professor, Institute of Astronomy, Geophysics and Atmospheric Sciences University<br />

of São Paulo, BRAZIL<br />

Professor sylvio CAnuto<br />

Institute of Physics, University of São Paulo, Brazil, BRAZIL<br />

Professor A. roBLedo<br />

Senior Research Scientist, Physics Institute, National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM),<br />

Mexico City, MEXICO<br />

north AMeriCA<br />

Professor Mitchell WinniK<br />

University Professor, Chemistry Department, Faculty of Arts and Science University of Toronto,<br />

CANADA<br />

Professor h. eugene stAnLey<br />

University Professor, Professor of Physics; Professor of Physiology,<br />

and Director, Center for Polymer Studies, Boston University, USA<br />

2 PAST LAUREATES JOIN<br />

THE <strong>2011</strong> PHYSICAL SCIENCES JURY<br />

Beatriz<br />

Barbuy<br />

Member of the Jury and 2009 Laureate<br />

“ After winning the L’Oréal-UNESCO Award<br />

For Women in Science, I had the incredible<br />

chance to share my research with the general<br />

public. By highlighting the contributions<br />

of each laureate, For Women in Science<br />

undoubtedly creates leverage for women<br />

researchers.<br />

As a result, it is now a true source of<br />

motivation in the ongoing quest for<br />

excellence which shows that with<br />

perseverance and tenacity,<br />

we can overcome any obstacle. ”<br />

Margaret<br />

Brimble<br />

Member of the Jury and 2007 Laureate<br />

“ One of the numerous challenges facing<br />

women scientists is to strike the right balance<br />

to successfully handle a multi-faceted career.<br />

Women researchers are generally asked to<br />

teach and serve as mentors in addition to their<br />

high-level research.<br />

The importance of an award like<br />

L’Oréal-UNESCO For Women in Science<br />

is to highlight outstanding women who can<br />

become veritable role models for future<br />

generations. After receiving my For Women in<br />

Science award, I was named president of the<br />

Rutherford Foundation of the Royal Society of<br />

New Zealand, which aims to support young<br />

researchers as they start their careers. ”

22<br />

THE <strong>2011</strong><br />

INTERNATIONAL FELLOWS:<br />

THE FACES OF SCIENCE<br />

FOR TOMORROW<br />

An International Network<br />

• Each year, 15 young women are encouraged through an<br />

International Fellowship to pursue their research abroad.<br />

• Along with the International Fellowships, national<br />

fellowships help women doctoral students to pursue<br />

research in their home country.<br />

• In total every year, more than 200 young women<br />

scientists are supported by the L’Oréal-UNESCO<br />

For Women in Science Fellowship programmes.<br />

Year after year, an international network continues<br />

to develop, reinforcing the potential for exchanges<br />

and knowledge sharing.<br />

L’ORÉAL-UNESCO SPECiAL FELLOWShiP<br />

“iN ThE FOOTSTEPS OF MARiE CURiE”<br />

Marcia Roye, PhD in Molecular Virology<br />

Lecturer in Biotechnology, Research Faculty of<br />

Pure and Applied Sciences, Associate Dean of<br />

graduate Studies, University of the West Indies,<br />

Kingston, Jamaica<br />

The celebration of the Marie Curie Nobel Prize Centennial<br />

is a real opportunity for the L’Oréal-UNESCO For Women<br />

Isabel Cristina<br />

Chinchilla soto<br />

COsTa riCa<br />

Alejandra<br />

Jaramillo gutierrez<br />

PaNama<br />

Andia<br />

Chaves fonnegra<br />

COLOmBia<br />

in Science programme to reaffirm its commitment to women<br />

scientists throughout their careers through the creation of a<br />

“Special Fellowship”.<br />

This new fellowship will be awarded to a former recipient of a<br />

For Women in Science International Fellowship who, through her<br />

outstanding career over the past ten years, incarnates the future<br />

of science.<br />

The first “Special Fellowship” is awarded to the Marcia Roye<br />

of Jamaica, who received a UNESCO-L’Oréal International

Samia elfékih<br />

TuNisia<br />

Hagar gelbard-sagiv<br />

israeL<br />

Fellowship in 2000 for her research on geminivirus, an insectborne<br />

virus that devastates crops around the world.<br />

Dr. Marcia Roye is passionate about research that has a direct<br />

impact on the lives of people. Her enthusiasm has been the<br />

driving force behind a particularly rich scientific career, and by<br />

age 42, she has already transformed the daily lives of numerous<br />

inhabitants of her native Jamaica and elsewhere.<br />

Her research in molecular virology focuses on two major projects.<br />

The first aims to improve the situation of Jamaican farmers who<br />

Germaine L.minoungou<br />

BurKiNa fasO<br />

Triin Vahisalu<br />

esTONia<br />

Mais absi<br />

syria<br />

Justine germo Nzweundji<br />

CamerOON<br />

Ladan Teimoori-Toolabi<br />

iraN<br />

Reyam al-malikey<br />

iraQ<br />

Fadzai Zengeya<br />

ZimBaBWe<br />

Nilufar mamadalieva<br />

uZBeKisTaN<br />

grow cash crops like peas and tomatoes, and the second is<br />

designed to help HIV patients.<br />

These two seemingly distinct fields of research have two<br />

points in common: both involve research on viruses, and<br />

both projects are guided by Marcia Roye’s unrelenting<br />

determination to use science to help people.<br />

Tatiana Lopatina<br />

russia<br />

Jiban Jyoti Panda<br />

iNDia

24<br />

THE IMPACT<br />

OF HUMAN ACTIVITY<br />

ON OUR ECOSYSTEMS<br />

COLOMbIA<br />

Marine ecology<br />

Coral reefs are not only threatened by overfishing,<br />

pollution and climate change, but also by the<br />

devastating effects of Cliona delitrix. This excavating<br />

sponge is capable of modifying the three-dimensional<br />

structure of coral reefs and reducing the amount<br />

of living coral tissue. Yet coral reefs play a vital role,<br />

providing a refuge for fish and protecting the coastline<br />

from waves and currents, thereby slowing erosion. We<br />

now know they can also serve as a potential resource<br />

for new drug molecules.<br />

A PhD student in marine biology, Andia Chaves<br />

Fonnegra, 31, is studying the effects of climate change<br />

on sponge populations and their impact on coral reefs<br />

in the Caribbean Sea. She is researching the timing<br />

of sponge reproduction and its possible correlation<br />

with sea temperature. By comparing the genetic<br />

profiles of neighbouring populations, she will be able<br />

to determine to what extent this species can be used<br />

as a bio-indicator of the deterioration of coral reefs in<br />

the Caribbean Sea.<br />

Andia<br />

Chaves Fonnegra<br />

HOST INSTITUTION:<br />

Nova Southeastern University Oceanographic Center,<br />

Fort Lauderdale, Florida, USA<br />

Andia Chaves Fonnegra’s research will<br />

help improve the management of coral<br />

reef restoration projects.<br />

After finishing her PhD, Andia plans<br />

to return to Colombia to continue her<br />

career as a researcher and teacher.<br />

She will focus her work on the potential<br />

of marine organisms as a source of new<br />

drugs for human diseases. Through<br />

her research, she hopes to inspire<br />

future generations to appreciate the<br />

importance of the ocean environment<br />

for human life.<br />

“If politics and the<br />

economy continue<br />

to build a world<br />

that does not take<br />

into account the<br />

preservation of life<br />

as its first objective,<br />

then we are heading<br />

straight toward its<br />

extinction.”

“I hope my research<br />

will eventually make an<br />

important contribution<br />

to the sustainability and<br />

conservation of Costa<br />

Rica’s precious natural<br />

resources.”<br />

IRAQ<br />

Ecology<br />

Today, a quarter of heavy metal pollution<br />

is generated by household waste, such as<br />

NiCad batteries, lead-acid batteries and<br />

the copper and zinc found in pesticides.<br />

These metals have a toxic impact on human<br />

and animal health and are a real threat<br />

to the environment. Unlike organic waste,<br />

heavy metals do not decay over time. They<br />

are ingested and accumulate in the bodies<br />

of animals and humans at each level of the<br />

food chain.<br />

Reyam Al-Malikey, 31, has a PhD in ecology<br />

and now works as an assistant lecturer<br />

in biology at the Al-Mustansiryha University<br />

in Baghdad, Iraq. She is concerned by the<br />

potentially damaging effects of heavy metal<br />

waste, such as cadmium, lead and zinc,<br />

on aquatic ecosystems and their health<br />

implications. This is particularly true in the<br />

southern marshlands of Iraq, which are<br />

undergoing restoration after the ravages of<br />

a government drainage program followed<br />

Isabel Cristina<br />

Chinchilla Soto<br />

COSTA RICA<br />

Ecology<br />

Covering 11.5 million km², tropical forests house over<br />

75% of living species and are a remarkable source of<br />

biodiversity. Numerous studies show how the preservation<br />

of tropical forests, which are often threatened by<br />

deforestation and the opening up of farmland, might help<br />

slow down global warming. Yet, most of these studies<br />

focus on rainforests and little attention has been given to<br />

the role of tropical dry forests, even though they represent<br />

over two thirds of land cover in Latin America and<br />

are just as endangered, notably from fire.<br />

A doctoral student in ecology at the University of Edinburgh,<br />

Scotland, Isabel Cristina Chinchilla-Soto, 32, is<br />

researching the effects of climate change on the carbon<br />

cycle in tropical dry forests.<br />

She will measure the impact of climate change in the dry<br />

forest of Costa Rica’s Santa Rosa National Park, where<br />

she will monitor fluctuations in gas exchange and the leaf<br />

characteristics of various trees. She then plans to analyse<br />

changes in species composition according to the<br />

age of each sampling site. Cristina hopes to demonstrate<br />

that the total carbon storage capacity of forests gradually<br />

increases with age before stabilising in forests over sixty<br />

years old. She will also investigate the ways different tree<br />

HOST INSTITUTION:<br />

School of Environmental Studies,<br />

Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada<br />

by the impact of war. The resulting pathologies are often<br />

degenerative diseases such as the diminution of cognitive<br />

faculties, Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease, and<br />

multiple sclerosis.<br />

Reyam uses geographic information systems (gIS), a<br />

technology combining statistical analysis, visualization<br />

and geographical analysis, as well as field sampling to<br />

establish a correlation between heavy metal concentration<br />

in different levels of the food chain and the nutrient<br />

levels of different marsh areas. She hopes to contribute<br />

to the development of anti-pollution strategies for this<br />

important ecosystem.<br />

When she returns to her university in Iraq, Reyam Al-Malikey<br />

plans to transfer her skills in gIS technology to other<br />

research projects. She would eventually like to set up her<br />

own research team to further explore the impact of pollution<br />

on Iraq’s ecosystems.<br />

HOST INSTITUTION:<br />

School of geoSciences,<br />

University of Edinburgh, Scotland, UK<br />

species cope with drought and how they<br />

allocate carbon to their constituent parts<br />

under different environmental conditions.<br />

Her research results will help refine predictions<br />

of changes to the forest ecosystem<br />

and develop vital decision-making tools for<br />

forest conservation and management.<br />

On completion of her PhD, Isabel Cristina<br />

will continue her research career at the<br />

University of Costa Rica, where she looks<br />

forward to sharing her love of science with<br />

the next generation of students.<br />

Reyam<br />

Al-Malikey<br />

“In science, there is<br />

no difference between<br />

men and women.<br />

Successful results<br />

depend on how hard<br />

you work, not on your<br />

gender.”

26<br />

“I hope to serve as<br />

an ambassador for<br />

women in science and<br />

technology in Tunisia.”<br />

Samia<br />

Elfékih<br />

TUNISIA<br />

Molecular biology<br />

HOST INSTITUTION:<br />

Faculty of Life Sciences and Medicine, Imperial College<br />

London, Silwood Park, Ascot, UK<br />

Ceratitis capitata, better known as the Mediterranean<br />

fruit fly or medfly, is an insect that can cause<br />

extensive damage to a wide range of fruit crops. A<br />

native of Africa, it has spread invasively to the entire<br />

Mediterranean basin as well as to many other parts of<br />

the world, where it causes severe economic losses<br />

for fruit growers. The insect is not only highly resistant<br />

to several pesticides, but as the climate gradually<br />

warms, there is a risk that the medfly will further<br />

expand its geographical range.<br />

In Tunisia, an agricultural country that has paid heavy<br />

tribute to this insect, Samia Elfékih, 31, with a PhD<br />

in biology from the University of Tunis ElManar,<br />

focuses on the genetic diversity of insect populations.<br />

During her fellowship, Samia Elfékih will try to better<br />

understand how mutant genes coding for resistance<br />

have spread geographically and across diverse<br />

environmental conditions. She will compare gene<br />

sequences from resistant and non-resistant medflies<br />

collected from across the world and examine which<br />

genetic mutations are due to natural evolutionary<br />

adaptation to changing environmental conditions and<br />

which are due to adaptation to insecticide use. She<br />

will then analyse the links between these two types of<br />

evolutionary adaptation to develop better alternatives<br />

to classic pesticides, ones that address changing<br />

climatic conditions and the increasing demand for<br />

eco-friendly solutions.<br />

At the end of her fellowship, Samia<br />

Elfékih will return to Tunisia to take up<br />

a position as associate professor. She<br />

is determined to transfer the technical<br />

skills she acquired during her studies in<br />

the UK and hopes to foster long-term<br />

research collaboration between the two<br />

countries.

Triin<br />

Vahisalu<br />

ESTONIA<br />

Plant molecular biology<br />

HOST INSTITUTION:<br />

Division of Plant Biology, University of Helsinki, Finland<br />

In the face of ever dwindling water<br />

resources, a key challenge for the future<br />

of agriculture is the study of droughtresistant<br />

plants. It is vital to research<br />

the mechanisms plants use to adapt to<br />

drought and to identify the specific genes<br />

involved.<br />

With a doctorate in Plant Biology at<br />

the University of Tartu, Estonia and the<br />

University of Helsinki, Triin Vahisalu, 32,<br />

is studying how plants react to changing<br />

environmental conditions.<br />

Leaves are covered with microscopic<br />

pores called stomata. By opening and<br />

closing these pores, plants regulate the<br />

intake of carbon dioxide as a nutrient<br />

and the release of oxygen. To avoid<br />

drying out when not given enough water,<br />

plants close the stomata and slow down<br />

photosynthesis. They are constantly<br />

striving to strike a balance between<br />

maximizing carbon dioxide intake and<br />

minimizing water loss.<br />

Triin Vahisalu has already identified the protein<br />

responsible for the regulation of stomatal closure<br />

in response to drought and ozone pollution, two<br />

factors to which plants are highly sensitive. During<br />

her fellowship, Triin plans to use Arabidopsis plants<br />

from the cabbage family, which grow in sandy soils,<br />

to analyse the mechanisms that activate this protein<br />

when ozone is detected by the plant and that<br />

deactivate the protein when the plant needs to open<br />

its stomata to take in carbon dioxide.<br />

On returning to Estonia, Triin Vahisalu plans to<br />

continue her research in this area and hopes her<br />

findings will eventually lead to the development<br />

of more agricultural crops that are more drought<br />

resistant with lower ozone sensitivity<br />

“With a population of 1.4<br />

million inhabitants, Estonia<br />

has only a few researchers<br />

specialising in plants.<br />

The fellowship provides<br />

invaluable support<br />

that will enable me to<br />

conduct research in a<br />

foreign laboratory.”

28<br />

NATURE: AN ALLY IN<br />

CONTROLLING THE SPREAD<br />

OF HEALTH DISASTERS<br />

germaine L.<br />

Minoungou<br />

bURKINA FASO<br />

Virology<br />

germaine L. Minoungou, 31, defines traditional poultry farming<br />

in Burkina Faso as the ‘‘poor man’s bank’’, but one that<br />

is all too often bankrupted by Newcastle disease, a highly infectious<br />

viral disease. Transmitted by direct contact with infected<br />

birds, contaminated equipment or the air, Newcastle disease<br />

affects all bird species and generates severe economic<br />

losses. Caused by a strain of avian paramyxovirus, Newcastle<br />

disease can lead to 100% mortality in an infected flock of<br />

poultry. Although effective vaccines for the disease exist, they<br />

are rarely used in rural areas because of their cost and the<br />

need to ensure a continuous cold chain for vaccine storage.<br />

germaine Minoungou is convinced of the need to improve<br />

the system for animal disease diagnosis in her country, in<br />

order to enable veterinary staff to differentiate between the<br />

symptoms of Newcastle disease and the often similar symptoms<br />

of avian influenza. This is why she has chosen to spend<br />

her fellowship in a laboratory specializing in these two viral<br />

diseases of birds.<br />

With a doctorate in veterinary medicine, germaine is now preparing<br />

a PhD in virology. She is head of the Virology Service<br />

at the National Laboratory for Livestock Diseases Diagnosis in<br />

HOST INSTITUTION:<br />

Research Center for Animal Hygiene and Food Safety,<br />

University of Obihiro, Hokkaido, Japan<br />

Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, where she is<br />

responsible for the diagnosis of viral disease<br />

in animal stock.<br />

She plans to begin by conducting an epidemiological<br />

study based on an analysis of<br />

poultry samples from across the country.<br />

She will isolate the virus strains found in infected<br />

poultry and analyse them to see whether<br />

those found in Burkina Faso are related to<br />

the strains found in other regions. She hopes<br />

to participate eventually in the development<br />

of a new, low-cost vaccine that could be<br />

stored without special refrigeration.<br />

The young scientist would like her research<br />

to make an important contribution to the well<br />