child care - Digital Library Collections

child care - Digital Library Collections child care - Digital Library Collections

THE STATE OF AMERICA'S CHILDREN YEARBOOK 1998 Table 2.2 Child Health Coverage: Best and Worst States· Ten best states Ten worst states Rank State Percentage of children uninsured Rank State Percentage of children uninsured 1 Wisconsin 6.4% 51 Texas 24.1% 2 Hawaii 6.7 50 New Mexico 22.9 3 Vermont 7.0 49 Arizona 22.4 4 Minnesota 7.1 48 Oklahoma 20.8 5 North Dakota 7.9 47 Louisiana 20.3 6 Michigan 8.1 46 Arkansas 19.3 7 South Dakota 8.5 45 Nevada 19.1 8 Pennsylvania 9.3 44 California 18.7 8 Massachusetts 9.3 43 Mississippi 18.6 10 Nebraska 9.4 42 Florida 17.5 'Including the District of Columbia. Source: U.S. Deportment of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, March Current Population Surveys for 1994-96. Calculations by Children's Defense Fund. for children with family income up to 185 percent of the federal poverty level, corroborates these fmdings. The Florida report states that when parents got help in buying coverage for uninsured children, more children received health care in doctors' offices and fewer were treated in hospital emergency rooms. According to the report, children's emergency room visits dropped by 70 percent in the areas served by the program, saving state taxpayers and consumers $13 million in 1996. CHIP: A Landmark Federal-State Partnership for Child Health Temendous help for uninsured children came in 1997 with enactment of the new State Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP) as part ofthe Balanced Budget Act. A core ofcongressionalleaders, including Senators Kennedy, Hatch, Chafee, and Rockefeller and Representatives Johnson, Matsui, and Dingell, championed the program. The campaign for Child Health Now, a broad-based coalition of more than 250 organizations, garnered support for the measure, and it passed with strong bipartisan backing. On August 5, 1997, President Clinton signed the bill into law, approving the largest funding increase for children's health insurance coverage since the original enactment of Medicaid in 1965. CHIP represents one of the most significant developments for children's health in decades. Effective October I, 1997, it provides $48 billion over 10 years for children's health coverage. The program includes targeted Medicaid expansions and state grants of roughly $4 billion annually to cover uninsured children with family income above current Medicaid eligibility levels but too low to afford private health insurance. As many as 5 million uninsured children could benefit, depending on how states implement the new program. States need to move quickly so that children receive necessary health care as soon as possible (see box 2.1). 26 CHI L D R EN'S D E FEN S E FUN D

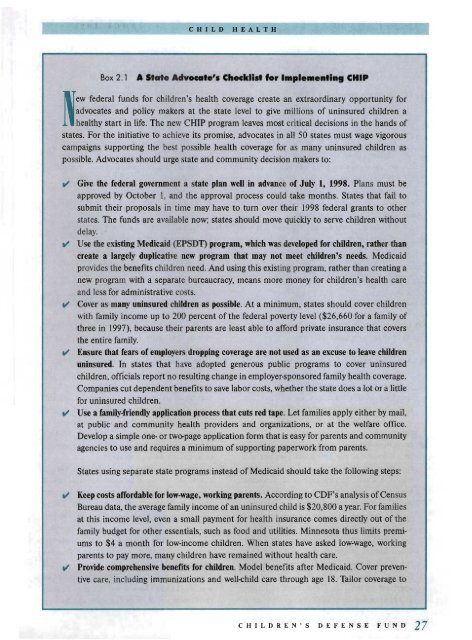

CHILD HEALTH Box 2.1 A State Advocate's Checklist for l..pl....ntln. CHIP New federal funds for children's health coverage create an extraordinary opportunity for advocates and policy makers at the state level to give millions of uninsured children a healthy start in life. The new CHIP program leaves most critical decisions in the hands of states. For the initiative to achieve its promise, advocates in all 50 states must wage vigorous campaigns supporting the best possible health coverage for as many uninsured children as possible. Advocates should urge state and community decision makers to: tJ' tJ' tJ' tJ' tJ' Give the federal government a state plan well in advance of July 1, 1998. Plans must be approved by October 1, and the approval process could take months. States that fail to submit their proposals in time may have to turn over their 1998 federal grants to other states. The funds are available now; states should move quickly to serve children without delay. Use the existing Medicaid (EPSDT) program, which was developed for children, rather than create a largely duplicative new program that may not meet children's needs. Medicaid provides the benefits children need. And using this existing program, rather than creating a new program with a separate bureaucracy, means more money for children's health care and less for administrative costs. Cover as many uninsured children as possible. At a minimum, states should cover children with family income up to 200 percent of the federal poverty level ($26,660 for a family of three in 1997), because their parents are least able to afford private insurance that covers the entire family. Ensure that fears of employers dropping coverage are not used as an excuse to leave children uninsured. In states that have adopted generous public programs to cover uninsured children, officials report no resulting change in employer-sponsored family health coverage. Companies cut dependent benefits to save labor costs, whether the state does a lot or a little for uninsured children. Use a family·friendly application process that cuts red tape. Let families apply either by mail, at public and community health providers and organizations, or at the welfare office. Develop a simple one- or two-page application form that is easy for parents and community agencies to use and requires a minimum ofsupporting paperwork from parents. States using separate state programs instead of Medicaid should take the following steps: tJ' tJ' Keep costs affordable for low-wage, working parents. According to CDF's analysis ofCensus Bureau data, the average family income ofan uninsured child is $20,800 a year. For families at this income level, even a small payment for health insurance comes directly out of the family budget for other essentials, such as food and utilities. Minnesota thus limits premiums to $4 a month for low-income children. When states have asked low-wage, working parents to pay more, many children have remained without health care. Provide comprehensive benefits for children. Model benefits after Medicaid. Cover preven· tive care, including immunizations and well-ehild care through age 18. Tailor coverage to CHI L D R EN'S D E FEN S E FUN D 27

- Page 2 and 3: About CDF he Children's Defense Fun

- Page 4 and 5: Copyright © 1998 by Children's Def

- Page 6 and 7: Acknowledgments Susanne Martinez, d

- Page 8 and 9: THE STATE OF AMERICA'S CHILDREN YEA

- Page 10 and 11: THE STATE OF AMERICA'S CHILDREN YEA

- Page 12 and 13: THE STATE OF AMERICA'S CHILDREN YEA

- Page 14 and 15: THE STATE OF AMERICA'S CHILDREN YEA

- Page 16 and 17: THE STATE OF AMERICA'S CHILDREN YEA

- Page 18 and 19: THE STATE OF AMERICA'S CHILDREN YEA

- Page 20 and 21: _____T...:H_._E... S T ATE 0 F AM E

- Page 22 and 23: .... T...-HE STATE OF AMERICA'S CHI

- Page 24 and 25: THE STATE OF AMERICA'S CHILDREN YEA

- Page 26 and 27: THE STATE OF AMERICA'S CHILDREN YEA

- Page 28 and 29: THE STATE OF AMERICA'S CHILDREN YEA

- Page 30 and 31: THE STATE OF AMERICA'S CHILDREN YEA

- Page 32 and 33: THE STATE OF AMERICA'S CHILDREN YEA

- Page 34 and 35: THE STATE OF AMERICA'S CHILDREN YEA

- Page 36 and 37: ....._--"T..;H;;..;;;.E STATE OF AM

- Page 38 and 39: THE STATE OF AMERICA'S CHILDREN YEA

- Page 40 and 41: THE STATE OF AMERICA'S CHILDREN YEA

- Page 42 and 43: THE STATE OF AMERICA'S CHILDREN YEA

- Page 44 and 45: THE STATE OF AMERICA'S CHILDREN YEA

- Page 46 and 47: ......._---'T;..;;.;;H....;;E STATE

- Page 48 and 49: '--__...;T;...;;;H...;E;;....S T AT

- Page 52 and 53: THE STATE OF AMERICA'S CHILDREN YEA

- Page 54 and 55: THE STATE OF AMERICA'S CHILDREN YEA

- Page 56 and 57: THE STATE OF AMERICA'S CHILDREN YEA

- Page 58 and 59: THE STATE OF AMERICA'S CHILDREN YEA

- Page 60 and 61: THE STATE OF AMERICA'S CHILDREN YEA

- Page 62 and 63: THE STATE OF AMERICA'S CHILDREN YEA

- Page 64 and 65: THE STATE OF AMERICA'S CHILDREN YEA

- Page 66 and 67: THE STATE OF AMERICA'S CHILDREN YEA

- Page 68 and 69: THE STATE OF AMERICA'S CHILDREN YEA

- Page 70 and 71: THE STATE OF AMERICA'S CHILDREN YEA

- Page 72 and 73: L-__T.HE STATE OF AMERICA'S CHILDRE

- Page 74 and 75: THE STATE OF AMERICA'S CHILDREN YEA

- Page 77 and 78: CHAPTER CHILD NUTRITION any America

- Page 79 and 80: CHILD NUTRITION gram requirements,

- Page 81 and 82: .... ..,;C;;..;,;H..;I;.,.L;;;.,;;D

- Page 83 and 84: CHILD NUTRITION ;;0".;'-'- .... pro

- Page 85 and 86: .... ....;;.c H I L D N U TR IT I O

- Page 87 and 88: CHAPTER CHILDREN AND FAMILIES IN CR

- Page 89 and 90: CHILDREN AND FAMILIES IN CRISIS pas

- Page 91 and 92: CHILDREN AND FAMILIES IN CRISIS in

- Page 93 and 94: CHILDREN A D FAMILIES IN CRISIS kin

- Page 95 and 96: CHILDREN AND FAMILIES IN CRISIS Box

- Page 97 and 98: '-- C~H,;,.;I L D R E NAN D F A MIL

- Page 99: CHILDREN AND FAMILIES IN CRISI""S"-

CHILD<br />

HEALTH<br />

Box 2.1<br />

A State Advocate's Checklist for l..pl....ntln. CHIP<br />

New federal funds for <strong>child</strong>ren's health coverage create an extraordinary opportunity for<br />

advocates and policy makers at the state level to give millions of uninsured <strong>child</strong>ren a<br />

healthy start in life. The new CHIP program leaves most critical decisions in the hands of<br />

states. For the initiative to achieve its promise, advocates in all 50 states must wage vigorous<br />

campaigns supporting the best possible health coverage for as many uninsured <strong>child</strong>ren as<br />

possible. Advocates should urge state and community decision makers to:<br />

tJ'<br />

tJ'<br />

tJ'<br />

tJ'<br />

tJ'<br />

Give the federal government a state plan well in advance of July 1, 1998. Plans must be<br />

approved by October 1, and the approval process could take months. States that fail to<br />

submit their proposals in time may have to turn over their 1998 federal grants to other<br />

states. The funds are available now; states should move quickly to serve <strong>child</strong>ren without<br />

delay.<br />

Use the existing Medicaid (EPSDT) program, which was developed for <strong>child</strong>ren, rather than<br />

create a largely duplicative new program that may not meet <strong>child</strong>ren's needs. Medicaid<br />

provides the benefits <strong>child</strong>ren need. And using this existing program, rather than creating a<br />

new program with a separate bureaucracy, means more money for <strong>child</strong>ren's health <strong>care</strong><br />

and less for administrative costs.<br />

Cover as many uninsured <strong>child</strong>ren as possible. At a minimum, states should cover <strong>child</strong>ren<br />

with family income up to 200 percent of the federal poverty level ($26,660 for a family of<br />

three in 1997), because their parents are least able to afford private insurance that covers<br />

the entire family.<br />

Ensure that fears of employers dropping coverage are not used as an excuse to leave <strong>child</strong>ren<br />

uninsured. In states that have adopted generous public programs to cover uninsured<br />

<strong>child</strong>ren, officials report no resulting change in employer-sponsored family health coverage.<br />

Companies cut dependent benefits to save labor costs, whether the state does a lot or a little<br />

for uninsured <strong>child</strong>ren.<br />

Use a family·friendly application process that cuts red tape. Let families apply either by mail,<br />

at public and community health providers and organizations, or at the welfare office.<br />

Develop a simple one- or two-page application form that is easy for parents and community<br />

agencies to use and requires a minimum ofsupporting paperwork from parents.<br />

States using separate state programs instead of Medicaid should take the following steps:<br />

tJ'<br />

tJ'<br />

Keep costs affordable for low-wage, working parents. According to CDF's analysis ofCensus<br />

Bureau data, the average family income ofan uninsured <strong>child</strong> is $20,800 a year. For families<br />

at this income level, even a small payment for health insurance comes directly out of the<br />

family budget for other essentials, such as food and utilities. Minnesota thus limits premiums<br />

to $4 a month for low-income <strong>child</strong>ren. When states have asked low-wage, working<br />

parents to pay more, many <strong>child</strong>ren have remained without health <strong>care</strong>.<br />

Provide comprehensive benefits for <strong>child</strong>ren. Model benefits after Medicaid. Cover preven·<br />

tive <strong>care</strong>, including immunizations and well-ehild <strong>care</strong> through age 18. Tailor coverage to<br />

CHI L D R EN'S D E FEN S E FUN D 27