Pacific Power Edu kit.pdf - Casula Powerhouse

Pacific Power Edu kit.pdf - Casula Powerhouse

Pacific Power Edu kit.pdf - Casula Powerhouse

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Edu</strong>cation Kit

Contents<br />

1 Curatorial statement: Culture currency, back to the mat – Leo Tanoi, Curator<br />

2 What is exchange?<br />

6 Back to the Mat<br />

8 The U-Turn Canoe (Waka) and Restore Respect Canoe Projects<br />

10 Shigeyuki Kihara<br />

12 Aaron McTaggart<br />

14 Greg Semu<br />

16 Angela Tiatia<br />

18 Glossary<br />

Culture currency,<br />

back to the mat<br />

Leo Tanoi, Curator<br />

<strong>Pacific</strong>a <strong>Power</strong> 2012 Culture currency, back to the mat is the third annual series of<br />

exhibitions, public and education programs and events held at <strong>Casula</strong> <strong>Power</strong>house<br />

Arts Centre which celebrate, showcase and explore <strong>Pacific</strong> cultures. The focus this<br />

year is on the role of commerce within the various systems of cultural exchange in<br />

contemporary society, particularly for <strong>Pacific</strong> communities.<br />

Many <strong>Pacific</strong>, <strong>Pacific</strong> Rim and other Indigenous cultures still trade traditional textiles<br />

such as I’e Toga, Samoan Woven Mats and Tongan and Fijian Tapa cloths used<br />

in ceremonies. Over 10,000 I’e Toga are exchanged on any given weekend across<br />

Australia as part of ceremonies for births, deaths and other important events. The<br />

traditional economies for <strong>Pacific</strong> trade of cultural ‘currencies’ are very much alive<br />

today and have existed for millennia.<br />

‘Back to the mat’ is a term understood to have been coined in colonial <strong>Pacific</strong> times<br />

to describe the Indigenous native going back to their roots. It refers to the rejection<br />

of colonial dictatorship politically, socially, commercially and physically. In particular<br />

it refers to the rejection of colonial dress. In the context of this exhibition <strong>Pacific</strong><br />

cultures and cultural ‘currencies’ thrive despite mainstream economies struggling<br />

with the fall out of the Global Financial Crisis.<br />

The exhibition tells the stories of how artists and their cultural practices have<br />

evolved to remain relevant, meaningful and current. Many of the artists’ works have<br />

traditional characteristics or subjects of the <strong>Pacific</strong> region while the materials used<br />

or the means of presenting their work are modern or contemporary. For example,<br />

Angela Tiatia’s collection of ‘island girls’ sourced from eBay cleverly occupies a<br />

place within the genre of Modernism as a found object or readymade. The calibre of<br />

works presented here are a testament to the tenacity and creativity of these <strong>Pacific</strong><br />

artists and their cultures to stay strong by adapting and evolving while retaining<br />

their ‘pacific power’.<br />

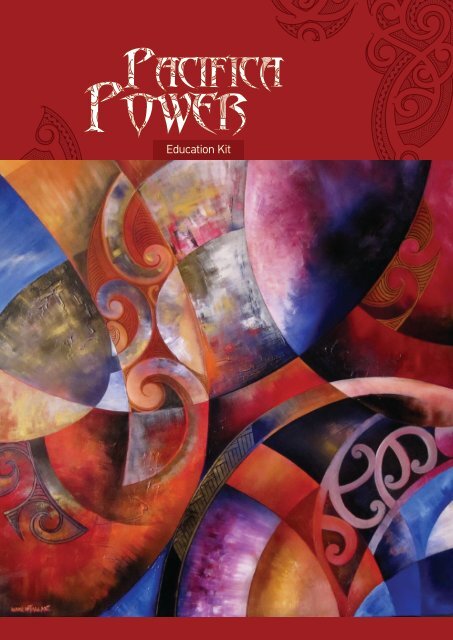

Cover image: Aaron McTaggart, Breaking Tradition (2011), impasto, texture paste,<br />

oil on canvas, 100 x 100 x 5cm. Courtesy of the artist.<br />

<strong>Casula</strong> <strong>Power</strong>house Arts Centre <strong>Pacific</strong>a <strong>Power</strong> <strong>Edu</strong>cation Kit 1

What is exchange?<br />

Exchange is a word that holds a variety of meanings. It basically means a reciprocal<br />

(give-and-take) transaction and can refer to a swapping of ideas, cultures, money or<br />

objects.<br />

Many people would probably relate ‘exchange’ to money, economy and capitalism<br />

– after all it contains the word ‘change’, relating to loose coin or leftover money,<br />

and the word ‘exchange’ also makes us think of things like the stock exchange. This<br />

connection is likely due to the dominance of money in Western capitalist societies.<br />

Money has allowed for the transaction of goods and services and its symbolic value<br />

means that these goods and services have become increasingly abstract. These<br />

days we transact on information such as ‘likes’ on Facebook, not just physical items.<br />

Consider the idea of ‘exchange’ in the Information Age (the age of the internet,<br />

telecommunications, and immediate access to information – like through Google).<br />

The internet has not just allowed for people to share ideas, information and culture.<br />

It has also allowed for online banking and e-commerce, these platforms mean that<br />

no physical money needs to be transacted. As a result, money itself has become<br />

a very abstract concept, which was not always the case. Prior to the Industrial<br />

Revolution money was very much a material substance, and gifts and exchange<br />

were also very common – in fact, they often formed the basis of social relations<br />

and society itself.<br />

This is still evident in the gift societies of countries such as India (through dowries<br />

for marriage), the <strong>Pacific</strong> where gift exchange still plays a large role in the<br />

community, and remnants in Western society with gift giving on birthdays, weddings<br />

and housewarmings (to name a few). To use <strong>Pacific</strong> culture as an example, gifts<br />

such as food, mats and other cultural items are commonly presented during<br />

ceremonial occasions such as weddings, the opening of prestigious buildings, and<br />

even form part of the judicial system with the presentation of gifts to victims or the<br />

victim’s families serving as atonement for a crime.<br />

In these examples we can see that the exchange value of the gift given does not<br />

always equally match its occasion or what is being reciprocally exchanged. What is<br />

more important than the gift itself is the process of giving/exchanging. As a result,<br />

the ‘gift exchange’ is a process that strengthens cultural and community ties, and<br />

interlinks individuals and families through a process of gift receiving, appreciation<br />

and obligation.<br />

Money and exchange have become increasingly depersonalised in today’s society<br />

– we can now transact with people on the other side of the world without ever<br />

having met them! At this time more than any other, it may be important to consider<br />

the role of exchange in connecting people and developing intimate or personal<br />

relationships. In the wake of the disappearance and abstraction of processes of<br />

exchange, do we need to think of new ways to bind our community together?<br />

2 <strong>Casula</strong> <strong>Power</strong>house Arts Centre<br />

<strong>Pacific</strong>a <strong>Power</strong> <strong>Edu</strong>cation Kit 3

4 <strong>Casula</strong> <strong>Power</strong>house Arts Centre<br />

<strong>Pacific</strong>a <strong>Power</strong> <strong>Edu</strong>cation Kit 5

Back to the Mat<br />

‘Back to the mat’ is the subtitle of the <strong>Pacific</strong>a <strong>Power</strong> exhibition. As a symbol of<br />

traditional arts practices, it acknowledges the contribution of these practices to<br />

contemporary ones. The ‘mat’ is also symbolic of the traditional cultural practices<br />

that keep <strong>Pacific</strong> communities connected, such as the practice of gift exchange. As<br />

the Curator Leo Tanoi stated, back to the mat encourages a celebration of ‘a return<br />

to the roots’.<br />

One example of an important cultural item is the ‘fine mats’ or ie’toga of Samoa or<br />

ngatu in Tonga. Ie’toga are a sacred item in Samoa and are exchanged during the<br />

celebration of births and marriages, ceremonies and other special occasions. They<br />

are created from the pandanus leaf and its weaving serves as a metaphor for the<br />

binding and keeping of things together. Its exchange reaffirms family connections<br />

through its representation of time and lineage.<br />

<strong>Pacific</strong> Mats & Cloths<br />

This table outlines some different types of mats and cloths found in various <strong>Pacific</strong><br />

cultures, and their specific uses.<br />

TAPA<br />

IE’TOGA<br />

LAVA LAVA<br />

LAP LAP<br />

TA‘OVALA<br />

A bark cloth made by <strong>Pacific</strong> Islands including Samoa, Tonga,<br />

Fiji, Niue, Vanuatu, New Zealand and Papua New Guinea. Tapa<br />

is the word accepted by most <strong>Pacific</strong> nations but is also known<br />

by many other local versions. Tapa can be painted, rubbed<br />

with colour, stamped, smoked or dyed. Once formerly used as<br />

clothing, tapa is now often worn on formal occasions or given<br />

as gifts. Other uses include a blanket, room dividers or as a<br />

decorative item hung on walls.<br />

A very special, almost sacred, mat woven from the pandanus.<br />

This item is gifted or exchanged on religious and ceremonial<br />

occasions and often binds families like a social contract.<br />

An article of daily clothing traditionally worn by cultures of the<br />

<strong>Pacific</strong>. It is a rectangular piece of cloth worn as a skirt, and is<br />

worn by both men and women. Many people of <strong>Pacific</strong> ethnicity<br />

wear the lava lava as an expression of cultural identity and for<br />

comfort within expatriate communities.<br />

A similar simple kind of clothing to the lava lava is the lap lap<br />

worn in Papua New Guinea and the South <strong>Pacific</strong>. The primary<br />

difference between these items is that the lap lap is completely<br />

open at both sides.<br />

A Tongan wearable item taking the form of a mat wrapped<br />

around the waist. It is worn by men and women at all formal<br />

occasions. The ta’ovala is also commonly seen among the<br />

Fijian Lau islands, a region that was once heavily influenced by<br />

Tongan cultural exchange.<br />

6 <strong>Casula</strong> <strong>Power</strong>house Arts Centre<br />

<strong>Pacific</strong>a <strong>Power</strong> <strong>Edu</strong>cation Kit 7

The U-Turn Canoe (Waka) and<br />

Restore Respect Canoe Projects<br />

A ‘waka’ is a sacred Maori canoe which is hand-carved with traditional inscriptions and symbols,<br />

presenting stories of the social history of those who created it.<br />

The U-Turn Canoe (Waka) Project is a multicultural canoe built by 23 young people in 2003 at<br />

SWYPE in Miller as a crime prevention and cultural awareness strategy. These young people spent<br />

eleven months with master carver Verdun Walker learning the ancient art of wood carving. Many<br />

of the young people involved were from disadvantaged backgrounds, and learning these unique<br />

traditional and cultural skills was a way for them to imagine a better future for themselves and<br />

therefore build a stronger community.<br />

The U-Turn Waka is eleven metres long and seats 25 people. Based on the traditional Maori canoes<br />

of New Zealand, the Waka features carved symbols and totems from many different cultures in the<br />

Miller area, including Arabic, Asian, <strong>Pacific</strong> Islander and those of the Gandagarra people of South<br />

Western Sydney. The carvings depict the diverse cultures and experiences of the young people in<br />

this area. The Canoe is carved with juxtapositions of traditional and youth culture symbols; from<br />

Indigenous and <strong>Pacific</strong> markings, to Nike boots and football designs.<br />

The project was initiated by workers at the Miller Youth Centre who wanted to give these young<br />

people an opportunity to learn new skills and change their attitudes about themselves. Team leader,<br />

Charlie Fruean says:<br />

The Waka Project has been a terrific success. By teaching the kids traditional carving, we’ve helped<br />

build their awareness, boost their self-esteem and re-connect them with their cultural identity.<br />

Seeing what these kids have achieved and how the project has transformed them has been amazing.<br />

It’s helped engage them in their local community and allowed them to break free of the stereotypes<br />

and create more positive images of young people. These kids have faced huge disadvantages in their<br />

short lives. We wanted to find a way to show them the great things they are capable of achieving<br />

when given the opportunity. I think what has been fascinating is watching how the power of ancient<br />

rituals and traditions has resonated with these young people, and how they have accepted the<br />

challenge put to them. 1<br />

Over the seven years of the Waka’s existence, exposure to the elements has meant that the canoe<br />

needed some attention and repairs. As such, the Restore Respect Canoe Project was initiated, which<br />

has seen twelve young people and community members work together to restore the canoe and<br />

learn the art of wood carving. The canoe restoration occurred over a six-month period. Now the<br />

canoe is ready to embark on a new phase of its life.<br />

Outcomes<br />

Five participants found employment and three participants moved onto TAFE for carpentry and<br />

plumbing.<br />

Question<br />

Imagine that you worked on this project. What symbols and totems would you<br />

carve on the canoe to represent yourself and your heritage? Explain why these<br />

markings would be significant to you.<br />

Verdun Walker (U-Turn Canoe Waka Project) and Peter Elers (Restore Respect Project), U-Turn Canoe (Waka) Project (2001-2003),<br />

wood carved canoe, 11 x 1.5m. Courtesy of the artists and Miller Youth Centre.<br />

1<br />

Quoted in ‘Ancient Canoe Floats the Hopes of Troubled Teens’ in UWS Latest News, 28 Nov 2003,<br />

http://pubapps.uws.edu.au/news/index.php?act=view&story_id=655<br />

8 <strong>Casula</strong> <strong>Power</strong>house Arts Centre<br />

<strong>Pacific</strong>a <strong>Power</strong> <strong>Edu</strong>cation Kit 9

Shigeyuki Kihara<br />

Shigeyuki Kihara is a Japanese-Samoan inter-disciplinary artist who explores both visual and<br />

performance arts in her practice. She was born and grew up in Japan, and moved to New Zealand<br />

when she was 16 years old. Kihara is interested in the intersections between art, performance and<br />

theatre, and how these forms interact with the public and foster dialogue about the complexities of<br />

humanity.<br />

Informing Kihara’s practice are investigations into the indigenous cultures of the <strong>Pacific</strong>, with specific<br />

focus on Samoan culture, history and spirituality. A central theme of her artworks is colonialism,<br />

particularly the experience of 19th century Samoans who were ‘examined’ by Western colonisers<br />

and portrayed ethnographically. Kihara’s artworks seek to undermine and challenge these<br />

stereotypes, traces of which remain today.<br />

For the <strong>Pacific</strong>a <strong>Power</strong> exhibition, Kihara presents video documentation of one of her most significant<br />

projects – Talanoa: Walk the Talk. The ancient Samoan concept of talanoa is a process between<br />

two parties to find a mutual ground through the exchange of ideas. The Talanoa series are ongoing<br />

performances which explore how the Samoan principle of talanoa can be applied universally<br />

to facilitate cross-cultural relationships between different communities. Shigeyuki’s talanoas<br />

are collaborative and intercultural musical and dance pieces performed between two diverse<br />

communities.<br />

Previous collaborations include: Talanoa I between a Scottish highland pipe band and Chinese<br />

dragon dancers; Talanoa II between Brazilian samba and Cook Island drummers; Talanoa III between<br />

Hindu singers and Christian singers; Talanoa IV between Aboriginal Australian didgeridoo players<br />

and Scottish highland drummers; Talanoa V between Chinese dragon dancers and Cook Island<br />

drummers; Talanoa VI was between Japanese Taiko Drummers and a Maori Kapa Haka cultural<br />

group; and Talanoa VII between the South Sudanese and the Kiribati communities.<br />

Artist statement<br />

There is something in music and dance that cuts through people’s insecurities, prejudice and<br />

misunderstandings about each other while going deep into the hearts, the minds and the spirit of<br />

the people. I have been fortunate enough to witness people transform and become enlightened<br />

though the Talanoa process while finding out more about each other in the process…When you see<br />

two different cultures with their distinct cultural contexts, beliefs and philosophies coming together,<br />

it is not only about them, it is also about the audience. I hope they begin to think about how they fit<br />

into this complex matrix—tradition, cliché, the present and the future informed by their past—how do<br />

they fit into this wider world. When people walk away from the performance I hope it inspires them<br />

to talanoa with someone outside their everyday world. I hope that my Talanoa project and method<br />

can operate as a catalyst for social change. 2<br />

Question<br />

Choose two different cultural groups. Research their traditional styles of dance<br />

and performance. How would you stage a talanoa between these two groups?<br />

What dance and performance styles would be on display, and what cultural<br />

exchange do you hope to achieve from the talanoa?<br />

Shigeyuki Kihara, Talanoa: Walk the Talk V (2010), DVD, duration: 21mins. Courtesy of the artist.<br />

2<br />

Shigeyuki Kihara quoted in Katerina M. Teiwa, ’An interview with interdisciplinary artist Shigeyuki Kihara’ in<br />

Intersections: Gender and Sexuality in Asia and the <strong>Pacific</strong>, Issue 27, November 2011,<br />

http://intersections.anu.edu.au/issue27/kihara.htm<br />

10 <strong>Casula</strong> <strong>Power</strong>house Arts Centre<br />

<strong>Pacific</strong>a <strong>Power</strong> <strong>Edu</strong>cation Kit 11

Aaron McTaggart<br />

Aaron McTaggart was born in Darwin and is of Maori/Pakeha descent. He is a fourth-generation<br />

artist who was taught to paint by his mother and aunties. As an artist, McTaggart delivers a unique<br />

perspective and shines a torch on the components of Maori art and Maoritanga that appeal to both<br />

the ‘old world’ and the ‘new world’; the traditional and the contemporary.<br />

Whakapapa (genealogical connections) is a key theme in most of McTaggart’s paintings. Maori people<br />

are spiritually attached to both their ancestral ties and the earth, and this plays an integral role in<br />

the kaupapa (theme, subject, plan) that defines his body of work. This is the reason kowhaiwhai<br />

design and the koru feature so prominently in his artwork. These are traditional flowing rafter<br />

designs that follow a repetitious pattern and are often found in Maori meeting houses. They usually<br />

tell a story about a particular tribe. McTaggart believes that everything we experience in life is only<br />

made possible through the pathway laid by our ancestors and our relationships with the earth. Our<br />

understanding of things, knowledge and abilities gained from those who came before lead us to<br />

thirst for a greater closeness to where we came from. We strive to move along this pathway, and in<br />

turn share the taonga (gift) of life with future generations.<br />

Artist statement<br />

My intentions as an artist are to harmoniously blend traditional Maori design elements and<br />

components with my own personal interpretations, whilst integrating the elements and technical<br />

aspects of art from the contemporary realm. I have always loved the beauty, simplicity and strength<br />

of Maori art and design. The natural bold shapes and impossibly precise linework of Taamoko and<br />

Whakairo (Tattooing and Carving) have influenced my art immensely. I strive to create an eclectic<br />

style of contemporary art that infuses timeless styles and injects an enthusiastic, vibrant perspective<br />

which all people may relate to and appreciate.<br />

Questions<br />

Identify the elements within McTaggart’s works which have been translated from<br />

traditional Maori customs to contemporary art. Consider lines (geometric and<br />

organic), textures, form, patterns and colour. How has McTaggart blended the ‘old<br />

world’ with the ‘new world’? What is your response to this amalgamation?<br />

How does McTaggart’s body of work relate to each of The Frames in Visual Arts?<br />

Subjective<br />

Cultural<br />

Structural<br />

Postmodern<br />

Aaron McTaggart,<br />

Segmented (2010),<br />

impasto, texture paint, oil<br />

on canvas, 60 x 91 x 5cm.<br />

Courtesy of the artist.<br />

12 <strong>Casula</strong> <strong>Power</strong>house Arts Centre<br />

<strong>Pacific</strong>a <strong>Power</strong> <strong>Edu</strong>cation Kit 13

Greg Semu<br />

Greg Semu is a photographer who was born and raised in New Zealand, but considers Samoa to<br />

be his ancestral and spiritual home. Semu’s practice explores themes of cultural displacement,<br />

particularly the colonial impact on indigenous cultures such as those of the <strong>Pacific</strong> Islands. He often<br />

looks to <strong>Pacific</strong> iconography and customs to investigate the differences between traditional and<br />

contemporary <strong>Pacific</strong> Island culture, and how these intersect with colonial histories.<br />

For the <strong>Pacific</strong>a <strong>Power</strong> exhibition, Semu’s Aussie Aiga series are 21 photographic portraits<br />

presenting various members of Samoan communities throughout Western Sydney. The word aiga<br />

means family, and in these photographs the artist engaged with the community and was welcomed<br />

into their homes and given the honour of taking their family portraits. These special moments<br />

captured on film reinforce the universal importance of family photos and the role that photographs<br />

play in presenting and illuminating human relationships and ancestral links.<br />

Furthermore, the portraits compliment the strong oral traditions of Samoan culture. Curator, Leo<br />

Tanoi, says that:<br />

Every village in Samoa has an ongoing fa’alupega – a recited charter of ceremonial greetings<br />

that incorporate salutations immemorial and the village hierarchy. The charter acts as an oral<br />

constitution and registry of the village’s chieftain titles. It serves as a reminder for all families<br />

within the village of their founding ancestors over the centuries. Photography can complement our<br />

contemporary oral genealogical claims. Photographic proof of a person’s existence, in the form of a<br />

family portrait, will help future family members attest and trace their lineage through oral and visual<br />

evidence.<br />

Artist statement<br />

‘Aussie aiga’ is a term that encapsulates ideas about inhabiting and belonging: to place, to country,<br />

to family. We photographed 200 people in the environments that they inhabit both domestically and<br />

socially. It was an incredibly bonding human experience. I came away from the project feeling I had<br />

been given an acknowledgement that we are the living descendents of a unique DNA tree dating<br />

back thousands of years. It was palpable, visible and communicable in all senses.<br />

Questions<br />

Analyse the series Aussie aiga in relation to the Conceptual Frame. How do these<br />

components relate to each other, and how do they intersect or overlap?<br />

World<br />

Greg Semu, Sydney members of the extended families of Vaipu’a Tafaoimalo Lalau, Penrith (2008),<br />

C type handprint off large format, 76 x 100cm. Courtesy of the artist and Lalau Leo Tanoi.<br />

Artwork<br />

Audience<br />

Artist<br />

14 <strong>Casula</strong> <strong>Power</strong>house Arts Centre<br />

<strong>Pacific</strong>a <strong>Power</strong> <strong>Edu</strong>cation Kit 15

Angela Tiatia<br />

Angela Tiatia is both an artist and a curator – she creates artworks and also organises and designs<br />

art exhibitions. Her art practice is mainly centred on sculpture, installation and video.<br />

As an artist Tiatia is interested in exposing the misrepresentations and stereotypes of <strong>Pacific</strong> peoples<br />

in contemporary and commercial culture. Her work often highlights colonialist assumptions and<br />

stereotypes, especially in relation to the passive depiction of women.<br />

In her work Foreign Objects, Tiatia scoured eBay and other online sites for antiques, memorabilia<br />

and tourist knickknacks that were sourced with search terms like ‘<strong>Pacific</strong>’ or ‘Polynesian’. The<br />

similarity between the items and their content highlights <strong>Pacific</strong> stereotypes such as the <strong>Pacific</strong><br />

beauty or the male ‘warrior’ depicted with primitive weaponry. Most significantly, the imagery of<br />

these objects often focuses on the physical form of the <strong>Pacific</strong> people, idealising curvy women and<br />

strong muscly men. Women are often depicted semi-nude in hula skirts. As a result, the viewer is<br />

forced to objectify these ‘bodies’.<br />

These items are presented like museum artefacts, displayed under glass cabinets. Tiatia has<br />

consciously created this presentation format to create a serious contemplative environment,<br />

encouraging the viewer to analyse these objects and their meaning rather than just seeing them as<br />

fun and frivolous. Consequently the viewer is forced to think about the implications of stereotypes<br />

that are seemingly harmless.<br />

Tiatia’s work comments on cultural and commercial processes of exchange. The commercialisation<br />

of <strong>Pacific</strong> stereotypes can be seen as a repressive and containing force that prevents an<br />

understanding of the true complexity and depth of <strong>Pacific</strong> culture.<br />

Artist statement<br />

I was very fascinated with the idea of how <strong>Pacific</strong> cultures are commercialised and captured in<br />

objects.<br />

Questions<br />

Analyse the work Foreign Objects through the Cultural Frame.<br />

Different objects have different meanings depending on their context. How do you think<br />

Angela Tiatia has altered the meaning of the objects contained within her work?<br />

Angela Tiatia, Foreign Objects (2011 – 2012), mixed media,<br />

dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artist.<br />

Imagine you were going to create a work that dealt with <strong>Pacific</strong> culture. Drawing from<br />

what you have seen in this exhibition, what kinds of themes would you deal with and what<br />

symbols and images would you use to communicate them?<br />

16 <strong>Casula</strong> <strong>Power</strong>house Arts Centre<br />

<strong>Pacific</strong>a <strong>Power</strong> <strong>Edu</strong>cation Kit 17

Glossary<br />

Abstract: not able to be touched, seen or felt; thought of apart from concrete realities, specific objects, or<br />

actual instances.<br />

Amalgamation: a combination of two or more elements.<br />

Capitalism: an economic system in which investment in and ownership of the means of production, distribution,<br />

and exchange of wealth is made and maintained chiefly by private individuals or corporations, especially as<br />

contrasted to cooperatively or state-owned means of wealth.<br />

Catalyst: something that causes activity between two or more forces without itself being affected.<br />

Colonialism: the control or governing influence of a nation over a dependent country, territory or people.<br />

Contemporary: of the present time.<br />

Context: the circumstances in which an event occurs, its setting.<br />

De-personalise: to deprive of personality or individuality<br />

Eclectic: composed of elements drawn from a variety of sources and styles.<br />

Encapsulate: to sum up in a short or concise form; condense.<br />

Ethnography: the branch of anthropology that deals with the scientific description of individual human societies.<br />

Frivolous: not serious or sensible in content, attitude or behaviour; silly.<br />

Genealogy: a record or account of the ancestry and descent of a person, family or group.<br />

Juxtaposition: placing two items or ideas side-by-side in order to compare and contrast.<br />

Iconography: symbolic representation, especially the conventional meanings attached to images.<br />

Installation: installation art uses sculptural materials and other media to modify the way we experience a<br />

particular space. It is used to create an idea or story for the viewer. Installation art is not necessarily confined to<br />

gallery spaces and can be any material intervention in everyday public or private spaces.<br />

Inter-disciplinary: a discipline is a field of study, research or practice, for example, visual arts, music and<br />

performance. Something that is inter-disciplinary involves the use of ideas and methods of many disciplines all<br />

at once.<br />

Intersection: a point where two or more ideas meet.<br />

Lineage: ancestry; from whom you directly came.<br />

Palpable: easily perceived by the senses or the mind.<br />

Prejudice: unreasonable feelings, opinions or attitudes, especially of a hostile nature, regarding a racial,<br />

religious or national group.<br />

Resonate: to expand, intensify or amplify a sound or feeling.<br />

Universal: applying to all people, at all times, in all places.<br />

18<br />

<strong>Casula</strong> <strong>Power</strong>house Arts Centre

<strong>Casula</strong> <strong>Power</strong>house Arts Centre<br />

1 <strong>Casula</strong> <strong>Power</strong>house Rd, <strong>Casula</strong>.<br />

Contact us:<br />

02 9824 1121<br />

reception@casulapowerhouse.com<br />

For information on excursion packages relating to this exhibition, please contact<br />

the <strong>Edu</strong>cation Officer Vi Girgis, girgis@casulapowerhouse.com or 9612 5214<br />

Written and produced by<br />

Vi Girgis: Public Programs and <strong>Edu</strong>cation Officer<br />

Nisa Mackie: Public Programs and <strong>Edu</strong>cation Manager<br />

ARTS CENTRE