Initiation of enteral feeding in preterm infants â how ... - iDOC Africa

Initiation of enteral feeding in preterm infants â how ... - iDOC Africa

Initiation of enteral feeding in preterm infants â how ... - iDOC Africa

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

MINI-REVIEW<br />

<strong>Initiation</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>enteral</strong> <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>preterm</strong> <strong>in</strong>fants – <strong>how</strong> does evidence <strong>in</strong>form<br />

current strategies<br />

Authors: Newton Opiyo 1<br />

Eric Ngetich 2<br />

Mike English 1, 3<br />

1. KEMRI/Wellcome Trust Research Programme, Nairobi, Kenya<br />

2. Department <strong>of</strong> Paediatrics, Moi Teach<strong>in</strong>g and Referral Hospital, Eldoret, Kenya<br />

3. Department <strong>of</strong> Paediatrics, Oxford University, Oxford, UK<br />

Summary<br />

In <strong>in</strong>itiat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>enteral</strong> <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong>s <strong>in</strong> <strong>preterm</strong> <strong>in</strong>fants, cl<strong>in</strong>icians struggle with questions on (1) when to<br />

<strong>in</strong>itiate (early or late) <strong>enteral</strong> <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> and <strong>how</strong> rapidly (slowly or rapidly) to <strong>in</strong>crease feed<br />

volumes. This review summarizes the evidence from systematic reviews and randomised<br />

controlled trials <strong>of</strong> <strong>enteral</strong> <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> strategies <strong>in</strong> <strong>preterm</strong> neonates, with a particular focus on<br />

def<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g optimal tim<strong>in</strong>g (early versus late) and rates <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> feed volume (slow versus<br />

rapid) suited to low-<strong>in</strong>come sett<strong>in</strong>gs where par<strong>enteral</strong> (<strong>in</strong>travenous) nutrition is not feasible. The<br />

GRADE (Grad<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) system<br />

was used to appraise the quality <strong>of</strong> available evidence. The review identified a number <strong>of</strong> limited<br />

short-term benefits <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>itiat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> early and <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g the volume at a relatively rapid rate<br />

us<strong>in</strong>g a standardized approach as long as the <strong>in</strong>fant is cl<strong>in</strong>ically well. Overall, available very low<br />

to low quality evidence suggests that despite some evidence <strong>of</strong> benefit from early <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong>, it<br />

rema<strong>in</strong>s unclear whether <strong>preterm</strong> <strong>in</strong>fants who receive par<strong>enteral</strong> nutrition should be given early<br />

or delayed <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong>s. Similarly, low to moderate quality evidence suggests that there is currently<br />

<strong>in</strong>sufficient evidence to determ<strong>in</strong>e whether slowly advanc<strong>in</strong>g <strong>enteral</strong> feed volumes reduces the<br />

risk <strong>of</strong> mortality or necrotis<strong>in</strong>g enterocolitis <strong>in</strong> <strong>preterm</strong> neonates. There is need for further cl<strong>in</strong>ical<br />

research <strong>in</strong> this area to develop a scientific basis to current <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> strategies.<br />

1

Background<br />

Very low birth weight (VLBW) and small for gestational age (SGA) <strong>in</strong>fants are at <strong>in</strong>creased risk<br />

<strong>of</strong> adverse neonatal outcomes. These ‘high risk <strong>in</strong>fants’ frequently demonstrate <strong>in</strong>tolerance <strong>of</strong><br />

feeds and high rates <strong>of</strong> necrotis<strong>in</strong>g enterocolitis (NEC) - a syndrome <strong>of</strong> acute <strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al necrosis<br />

<strong>of</strong> unknown aetiology [1]. Risk factors for NEC <strong>in</strong>clude: extreme prematurity, SGA (due to <strong>in</strong>trauter<strong>in</strong>e<br />

growth restriction) and <strong>enteral</strong> <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> [1, 2]. Compared with stable term <strong>in</strong>fants without<br />

NEC, high risk <strong>in</strong>fants who develop NEC have: a greater than 20% mortality, lower levels <strong>of</strong><br />

nutrient <strong>in</strong>take, slower rate <strong>of</strong> post-natal growth, a higher <strong>in</strong>cidence <strong>of</strong> nosocomial <strong>in</strong>fections,<br />

longer duration <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>tensive care and hospital stay, and higher <strong>in</strong>cidence <strong>of</strong> long-term<br />

neurological disability [1-3].<br />

As prevent<strong>in</strong>g prematurity rema<strong>in</strong>s an elusive goal <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> regimens therefore try and steer a<br />

course between firm observational evidence suggest<strong>in</strong>g a strong association between <strong>enteral</strong><br />

nutrition and NEC (an adverse effect) and the clear relationship between improved nutrition and<br />

better early post-natal growth (a positive effect). Unfortunately, to date, there is no consensus<br />

on <strong>how</strong> to balance these compet<strong>in</strong>g risks and optimise <strong>in</strong>itial <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> strategies <strong>in</strong> high-risk<br />

<strong>in</strong>fants. More conservative strategies <strong>in</strong> use <strong>in</strong>clude: delay<strong>in</strong>g feeds, slowly <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g feeds,<br />

use <strong>of</strong> total par<strong>enteral</strong> nutrition, and prophylactic antibiotics [4, 5]. In this paper we summarize<br />

available best evidence on the safety and effectiveness <strong>of</strong> methods <strong>of</strong> establish<strong>in</strong>g <strong>enteral</strong><br />

<strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> small, <strong>preterm</strong> <strong>in</strong>fants. Our aim is to consider <strong>how</strong> this evidence helps def<strong>in</strong>e which<br />

strategies are likely to be best suited to low-<strong>in</strong>come sett<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>in</strong> which par<strong>enteral</strong> nutrition (either<br />

total or partial) is not available to provide additional caloric and nutrient <strong>in</strong>take. Furthermore the<br />

context <strong>in</strong> which any guidel<strong>in</strong>e might be implemented is one <strong>in</strong> which the cause <strong>of</strong> low or very<br />

low birth weight, whether prematurity or SGA, may not be identified by the health workers who<br />

provide the majority <strong>of</strong> care who have limited tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g or experience. We also consider the<br />

evidence <strong>in</strong> the light <strong>of</strong> an exist<strong>in</strong>g Kenyan recommendation, based on expert op<strong>in</strong>ion, that<br />

promotes: (1) relatively ‘early’ <strong>in</strong>troduction <strong>of</strong> <strong>enteral</strong> feeds, and; (2) a standardized approach <strong>of</strong><br />

relatively ‘rapid’ rates <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>itial <strong>enteral</strong> feed volumes (see box 1 outl<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g current<br />

recommendation).<br />

Methods<br />

Search strategy and study selection criteria<br />

Potential articles for <strong>in</strong>clusion were identified by direct searches <strong>of</strong> The Cochrane Library and<br />

MEDLINE (both from <strong>in</strong>ception to March 2009). MEDLINE was searched via PubMed cl<strong>in</strong>ical<br />

filters. The searches were performed us<strong>in</strong>g comb<strong>in</strong>ations <strong>of</strong> the follow<strong>in</strong>g Medical Subject<br />

Head<strong>in</strong>g (MeSH) terms: ‘<strong>in</strong>fant’, ‘newborn’, ‘neonate’, ‘premature’, ‘low birth weight’, ‘<strong>in</strong>fant<br />

formula’, ‘formula’, ‘milk’, ‘<strong>enteral</strong> nutrition’, and ‘<strong>enteral</strong> <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong>’. No time or language<br />

restrictions were applied <strong>in</strong> these searches. Where high quality, previously conducted<br />

systematic reviews had been performed we <strong>in</strong>cluded these reviews and did not retrieve or-reevaluate<br />

the <strong>in</strong>dividual trials that were <strong>in</strong>cluded. Trials identified that were not <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong><br />

systematic reviews were considered for eligibility. Additional published and unpublished studies<br />

2

were sought by screen<strong>in</strong>g through references <strong>of</strong> identified reviews / study reports and writ<strong>in</strong>g to<br />

authors <strong>of</strong> identified relevant papers / abstracts.<br />

The criteria for consider<strong>in</strong>g studies for <strong>in</strong>clusion <strong>in</strong> this review are summarised <strong>in</strong> table 1. Study<br />

selection was done by two <strong>in</strong>dependent reviewers (NO and EN). The studies were screened <strong>in</strong><br />

two rounds, first on title and abstract, and second on full text, aga<strong>in</strong>st the pre-def<strong>in</strong>ed eligibility<br />

criteria summarised <strong>in</strong> table 1. Discrepancies between the reviewers were resolved by<br />

discussion.<br />

Quality assessment<br />

Quality <strong>of</strong> available evidence from the selected studies was assessed us<strong>in</strong>g the Grad<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong><br />

Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach [6]. The<br />

approach classifies the quality <strong>of</strong> evidence (def<strong>in</strong>ed as: ‘the extent to which one can be<br />

confident that an estimate <strong>of</strong> effect or association can be correct’) <strong>in</strong>to 4 categories: high,<br />

moderate, low, or very low (table 2). The GRADE evidence pr<strong>of</strong>iles were prepared by one<br />

reviewer (NO) and verified by a second reviewer (EN). Discrepancies between the reviewers <strong>in</strong><br />

the quality rat<strong>in</strong>gs were resolved by discussion.<br />

Data extraction and analysis<br />

Data on study characteristics (designs, participants, etc) and outcome measures were extracted<br />

by one reviewer (NO) and checked by a second reviewer (EN). Data abstraction errors were<br />

discussed and corrected. Study results were summarised narratively given important<br />

differences <strong>in</strong>: study sett<strong>in</strong>gs, birth weights and gestational ages <strong>of</strong> studied <strong>in</strong>fants and <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong><br />

regimens.<br />

Results<br />

The study selection process is summarised <strong>in</strong> figure 1. Overall, 6 papers were <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> this<br />

review: four systematic reviews [1, 2, 7, 8], one published randomised controlled trial (RCT) [9],<br />

and one unpublished RCT [10]. Details <strong>of</strong> the methods and results <strong>of</strong> the reviews / randomised<br />

controlled trial (RCT) are presented below and summarised <strong>in</strong> the GRADE evidence pr<strong>of</strong>iles<br />

(see tables 2, 4 to 7). Overall, the GRADE quality <strong>of</strong> evidence varied from low to moderate for<br />

the critical / important outcomes considered.<br />

i) When should <strong>enteral</strong> <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong>s be <strong>in</strong>itiated <strong>in</strong> high-risk <strong>in</strong>fants?<br />

a) Plausibility evidence (derived from RCTs) on ‘ma<strong>in</strong>tenance volume’ <strong>enteral</strong><br />

<strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> on day 1 <strong>of</strong> life<br />

Evidence for the effectiveness / safety <strong>of</strong> ‘ma<strong>in</strong>tenance volume’ <strong>enteral</strong> <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> on day 1 <strong>of</strong> life<br />

was derived from one rigorously conducted World Health Organisation (WHO) technical review<br />

[8]. A common practice <strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g countries, where provision <strong>of</strong> total par<strong>enteral</strong> nutrition is<br />

very rarely feasible, is to <strong>in</strong>itiate ma<strong>in</strong>tenance <strong>enteral</strong> feeds on day 1 <strong>of</strong> life and monitor the<br />

3

<strong>in</strong>fants closely. However, some cl<strong>in</strong>icians delay <strong>in</strong>itiation <strong>of</strong> <strong>enteral</strong> feeds to day 2, provid<strong>in</strong>g<br />

simple glucose / electrolyte ma<strong>in</strong>tenance crystalloid fluids <strong>in</strong>travenously, until the <strong>in</strong>fants have<br />

been assessed to be stable and not at risk <strong>of</strong> respiratory distress.<br />

To date, only three studies [11-13], conducted <strong>in</strong> the 1960s <strong>in</strong> the US and UK, have exam<strong>in</strong>ed<br />

the effects <strong>of</strong> such ‘early’ <strong>in</strong>itiation <strong>of</strong> ‘ma<strong>in</strong>tenance’ <strong>enteral</strong> <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> on day 1 <strong>of</strong> birth <strong>in</strong> high risk<br />

<strong>in</strong>fants (table 3). Two <strong>of</strong> the studies [11, 12] found no significant difference <strong>in</strong> mortality between<br />

‘early’ (day 1) and ‘delayed’ <strong>enteral</strong>ly fed <strong>in</strong>fants. One <strong>of</strong> the studies [13] <strong>how</strong>ever found an<br />

<strong>in</strong>creased risk <strong>of</strong> death <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>fants given milk feeds with<strong>in</strong> 2 to 4 hours <strong>of</strong> birth, compared to those<br />

fed smaller volumes from 12 to 16 hours (mortality rate ratio 2.93, 95% confidence <strong>in</strong>terval (CI):<br />

1.29 to 6.67). The effect <strong>of</strong> ‘early’ <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> on the time to rega<strong>in</strong> birth weight was varied:<br />

significant improvement was found <strong>in</strong> one study [12] while no evidence <strong>of</strong> effect was found <strong>in</strong><br />

another [11].<br />

The only other evidence about tim<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> onset <strong>of</strong> <strong>enteral</strong> <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> is from a recent Cochrane<br />

systematic review [7] which identified 3 RCTs (N=115 <strong>in</strong>fants) (table 2). This review found no<br />

significant difference <strong>in</strong> weight ga<strong>in</strong>, g/kg/week (mean difference -1.00, 95% CI: -127.4 to<br />

125.4), NEC (risk ratio 1.27 to 95% CI: 0.54 to 3.00), mortality (rate ratio 0.87, 95% CI: 0.34 to<br />

2.28) or duration <strong>of</strong> hospital stay (post-menstrual weeks at discharge) (mean difference, 0.90,<br />

95% CI: -1.21 to 3.01) among <strong>in</strong>fants started on progressive <strong>enteral</strong> feeds at > 4 days (‘delayed’<br />

<strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong>) compared to those started on <strong>enteral</strong> feeds at a mean or median age <strong>of</strong> ≤ 4 days<br />

(‘early’ <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong>) although important beneficial or harmful effects could not be excluded given the<br />

small number <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>fants studied. The authors concluded that available data are <strong>in</strong>sufficient to<br />

guide cl<strong>in</strong>ical practice and recommended further trials to provide robust evidence to <strong>in</strong>form this<br />

key area <strong>of</strong> care.<br />

b) Mixed evidence (derived from RCTs / observational studies) on <strong>in</strong>itial <strong>enteral</strong><br />

<strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong><br />

While early (small) RCTs found no effect <strong>of</strong> delayed <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> on NEC [14, 15], limited early<br />

(trophic) <strong>enteral</strong> nutrition has been s<strong>how</strong>n to improve the functional adaptability <strong>of</strong> the<br />

gastro<strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al tract and eventually <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> tolerance, especially when human milk is used [16,<br />

17] although the practice has been reported to be associated with an <strong>in</strong>creased risk <strong>of</strong> NEC [18,<br />

19].<br />

Overall, <strong>in</strong>terpretation <strong>of</strong> the available RCT and observational data on the benefits and risks <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>itial <strong>enteral</strong> feeds is limited by the small number <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>fants <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> studies, considerable<br />

variation and overlap <strong>in</strong> the def<strong>in</strong>itions <strong>of</strong> ‘early’ and ‘delayed’ <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> schedules and a number<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>herent methodological flaws (e.g. unclear method <strong>of</strong> randomization, lack <strong>of</strong> bl<strong>in</strong>ded<br />

assessments <strong>of</strong> outcomes, and exclusion <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>fants who developed complications dur<strong>in</strong>g<br />

hospitalization). Thus, considerable uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty persists regard<strong>in</strong>g the optimal tim<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>itiation<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>enteral</strong> <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> high risk <strong>in</strong>fants.<br />

ii) When <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong>s are advanced, <strong>how</strong> rapidly should the volume be <strong>in</strong>creased?<br />

4

Controversy persists regard<strong>in</strong>g <strong>how</strong> fast to advance <strong>enteral</strong> <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong>: limited retrospective data<br />

suggests that rapid rates <strong>of</strong> feed advancement are associated with <strong>in</strong>creased risk <strong>of</strong> NEC <strong>in</strong><br />

VLBW <strong>in</strong>fants; conversely, slow rates <strong>of</strong> feed advancement may result <strong>in</strong> undernutrition,<br />

prolonged exposure to hazards <strong>of</strong> par<strong>enteral</strong> nutrition, prolonged hospital stay and delayed<br />

establishment <strong>of</strong> full <strong>enteral</strong> nutrition [18, 19].<br />

Evidence on the effects <strong>of</strong> slow versus rapid rates <strong>of</strong> advanc<strong>in</strong>g <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> volumes <strong>in</strong> <strong>preterm</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>fants is derived from one updated Cochrane review [2] and one RCT [9] published after the<br />

Cochrane review. The Cochrane review identified three small RCTs (N=396 <strong>in</strong>fants) [20-22].<br />

Entry criteria and rates <strong>of</strong> advancement <strong>of</strong> <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> volumes <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>cluded RCTs were varied: <strong>in</strong><br />

the Caple trial, <strong>in</strong>fants 1000-2000 g were enrolled and <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong>s were advanced at 20 mL/kg/day<br />

and 30 mL/kg/day <strong>in</strong> the slow and rapid groups; <strong>in</strong> the Salhotra trial, <strong>in</strong>fants with birth weight<br />

less than 1205 g were enrolled, and <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong>s were advanced at 15 mL/kg/day and 30<br />

mL/kg/day <strong>in</strong> the slow and rapid groups respectively; <strong>in</strong> the Rayyis trial, <strong>in</strong>fants 501-1500 g were<br />

enrolled and <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong>s were advanced at 15 mL/kg/day and 35 mL/kg/day.<br />

Overall, comb<strong>in</strong>ed results did not detect statistically significant effects on the risk <strong>of</strong> NEC (risk<br />

ratio 0.96, 95% CI: 0.48 to 1.92) or all-cause mortality (rate ratio 1.40, 95% CI: 0.71 to 2.80).<br />

Infants who had slow rates <strong>of</strong> feed volume advancement took longer to rega<strong>in</strong> birth weight<br />

(reported mean difference between three and five days). No statistically significant effect on the<br />

total duration <strong>of</strong> hospital stay was detected. The authors concluded that: (1) available data do<br />

not provide evidence that slow advancement <strong>of</strong> <strong>enteral</strong> feed volumes reduces the risk <strong>of</strong> NEC <strong>in</strong><br />

VLBW <strong>in</strong>fants; and (2) <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g the volume <strong>of</strong> <strong>enteral</strong> feeds at slow rather than faster rates<br />

results <strong>in</strong> several days delay <strong>in</strong> rega<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g birth weight and establish<strong>in</strong>g full <strong>enteral</strong> feeds but the<br />

long-term cl<strong>in</strong>ical importance <strong>of</strong> these effects are unclear.<br />

In the RCT [9], a total <strong>of</strong> 100 stable neonates weigh<strong>in</strong>g between 1000 and 1499 g and<br />

gestational age less than 34 weeks were randomly allocated to <strong>enteral</strong> <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> (expressed<br />

human milk or formula) advancement <strong>of</strong> 20 mL/kg/day (n=50) or 30 mL/kg/day (n=50).<br />

Neonates <strong>in</strong> the rapid <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> advancement group achieved full volume <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong>s before the<br />

slow advancement group (median 7 days versus 9 days, p

<strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> protocols: current <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> regimens (CFRs, n=37 babies) and standardised <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong><br />

regimens (SFRs, n=35 babies). The CFR consisted <strong>of</strong> slow <strong>in</strong>troduction and low volume<br />

<strong>in</strong>crement <strong>of</strong> <strong>enteral</strong> feeds. In the SFR group, feeds were <strong>in</strong>troduced with<strong>in</strong> 4 to 24 hours after<br />

birth, and volumes <strong>in</strong>creased rapidly. SFR was associated with (1) a cl<strong>in</strong>ically significant<br />

<strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> mean weight ga<strong>in</strong>, g/kg/day (SFR 14.1 versus CFR 9.8; p

Conclusions<br />

Available very low to low quality evidence suggests that despite some evidence <strong>of</strong> benefit from<br />

early <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong>s, it rema<strong>in</strong>s unclear whether low or very low birth weight <strong>in</strong>fants who receive<br />

par<strong>enteral</strong> nutrition should be given early or delayed <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong>s. Similarly, low to moderate quality<br />

evidence suggests that there is currently <strong>in</strong>sufficient evidence to determ<strong>in</strong>e whether slowly<br />

advanc<strong>in</strong>g <strong>enteral</strong> feed volumes reduces the risk <strong>of</strong> mortality or necrotis<strong>in</strong>g enterocolitis <strong>in</strong> very<br />

low birth weight <strong>in</strong>fants. Conversely, low quality evidence suggests standardised <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong><br />

regimens <strong>in</strong> the form <strong>of</strong> cl<strong>in</strong>ical practice guidel<strong>in</strong>es may be important <strong>in</strong> prevent<strong>in</strong>g / m<strong>in</strong>imiz<strong>in</strong>g<br />

necrotis<strong>in</strong>g enterocolitis <strong>in</strong> <strong>preterm</strong> neonates. Overall, further randomised controlled studies that<br />

compare different ages <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>itiation <strong>of</strong> <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong>s, and that assess the effect <strong>of</strong> vary<strong>in</strong>g the rates <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>enteral</strong> <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong>s given to very low birth weight <strong>in</strong>fants are needed to strengthen the evidence<br />

base.<br />

7

References<br />

1. Patole S, de Klerk N: Impact <strong>of</strong> standardised <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> regimens on <strong>in</strong>cidence <strong>of</strong> neonatal<br />

necrotis<strong>in</strong>g enterocolitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis <strong>of</strong> observational studies.<br />

Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2005, 90(2):F147-151.<br />

2. McGuire W, Bombell S: Slow advancement <strong>of</strong> <strong>enteral</strong> feed volumes to prevent<br />

necrotis<strong>in</strong>g enterocolitis <strong>in</strong> very low birth weight <strong>in</strong>fants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev<br />

2008, 2:CD001241.<br />

3. Bisquera J, Cooper T, Berseth C: Impact <strong>of</strong> necrotis<strong>in</strong>g enterocolitis on length <strong>of</strong> stay<br />

and hospital charges <strong>in</strong> very low birth weight <strong>in</strong>fants. Pediatrics 2002, 109:423-428.<br />

4. Churella H, Bachhuber W, MacLean WJ: Survey: methods <strong>of</strong> <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> low-birth-weight<br />

<strong>in</strong>fants. Pediatrics 1985, 76(2):243-249.<br />

5. Siu Y, Ng P, Fung S, et al: Double bl<strong>in</strong>d, randomised, placebo controlled study <strong>of</strong> oral<br />

vancomyc<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> prevention <strong>of</strong> necrotis<strong>in</strong>g enterocolitis <strong>in</strong> <strong>preterm</strong>, very low birthweight<br />

<strong>in</strong>fants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 1998, 79(2):F105-109.<br />

6. Guyatt G, Oxman A, Vist G, et al: GRADE: an emerg<strong>in</strong>g consensus on rat<strong>in</strong>g quality <strong>of</strong><br />

evidence and strength <strong>of</strong> recommendations. BMJ 2008, 336(7650):924-926.<br />

7. Bombell S, McGuire W: Delayed <strong>in</strong>troduction <strong>of</strong> progressive <strong>enteral</strong> feeds to prevent<br />

necrotis<strong>in</strong>g enterocolitis <strong>in</strong> very low birth weight <strong>in</strong>fants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev<br />

2008; 16(2).<br />

8. Edmond K, Bah lR: World Health Organisation. Optimal <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>of</strong> low-birth-weight<br />

<strong>in</strong>fants. Technical review. 2006.<br />

9. Krishnamurthy S, Gupta P, Debnath S, Gomber S: Slow versus rapid <strong>enteral</strong> <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong><br />

advancement <strong>in</strong> <strong>preterm</strong> newborn <strong>in</strong>fants 1000-1499 g: a randomized controlled trial.<br />

Acta Paediatr 2010, 99(1):42-46.<br />

10. Ngetich E, Were F, English M, Musoke RN: Effect <strong>of</strong> a standardised <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> regimen on<br />

early neonatal growth <strong>in</strong> low and very low birth weight neonates at Kenyatta National<br />

Hospital: a pilot randomised controlled trial. Unpublished MMed thesis, 2009.<br />

11. Cornblath M, Forbes A, Pildes R, et al: A controlled study <strong>of</strong> early fluid adm<strong>in</strong>istration on<br />

survival <strong>of</strong> low birth weight <strong>in</strong>fants. Pediatrics 1966, 38(4):547-554.<br />

12. Smallpeice V, Davies P: Immediate <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>of</strong> premature <strong>in</strong>fants with undiluted breastmilk.<br />

Lancet 1964, 2(7374):1349-1352.<br />

13. Wharton B, Bower B: Immediate or later <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> for premature babies? A controlled trial.<br />

Lancet 1965, 2(7420):769-772.<br />

14. LaGamma E, Ostertag S, Birenbaum H: Failure <strong>of</strong> delayed oral <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong>s to prevent<br />

necrotiz<strong>in</strong>g enterocolitis. Results <strong>of</strong> study <strong>in</strong> very-low-birth-weight neonates. Am J Dis<br />

Child 1985, 139(4):385-389.<br />

15. Ostertag S, LaGamma E, Reisen C, Ferrent<strong>in</strong>o F: Early <strong>enteral</strong> <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> does not affect<br />

the <strong>in</strong>cidence <strong>of</strong> necrotiz<strong>in</strong>g enterocolitis. Pediatrics 1986, 77(3):275-280.<br />

16. Berseth C: Neonatal small <strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al motility: motor responses to <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> term and<br />

<strong>preterm</strong> <strong>in</strong>fants. J Pediatr 1990, 117(5):777-782.<br />

17. Lucas A, Bloom S, Aynsley-Green A: Gut hormones and 'm<strong>in</strong>imal <strong>enteral</strong> <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong>'. Acta<br />

Paediatr Scand 1986, 75(5):719-723.<br />

18. Brown E, Sweet A: Prevent<strong>in</strong>g necrotiz<strong>in</strong>g enterocolitis <strong>in</strong> neonates. JAMA 1978,<br />

240:2452-2454.<br />

19. Uauy R, Fanar<strong>of</strong>f A, Korones S, et al: Necrotiz<strong>in</strong>g enterocolitis <strong>in</strong> very low birth weight<br />

<strong>in</strong>fants: biodemographic and cl<strong>in</strong>ical correlates. National Institute <strong>of</strong> Child Health and<br />

Human Development Neonatal Research Network. J Pediatr 1991, 119(4):630-638.<br />

20. Caple J, Armentrout D, Huseby V, et al: Randomized, controlled trial <strong>of</strong> slow versus<br />

rapid <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> volume advancement <strong>in</strong> <strong>preterm</strong> <strong>in</strong>fants. Pediatrics 2004, 114:1597-1600.<br />

8

21. Rayyis S, Ambalavanan N, Wright L, Carlo W: Randomized trial <strong>of</strong> “slow” versus “fast”<br />

feed advancements on the <strong>in</strong>cidence <strong>of</strong> necrotiz<strong>in</strong>g enterocolitis <strong>in</strong> very low birth weight<br />

<strong>in</strong>fants. Journal <strong>of</strong> Pediatrics 1999, 134:293-297.<br />

22. Salhotra A, Ramji S: Slow versus fast <strong>enteral</strong> feed advancement <strong>in</strong> very low birth weight<br />

<strong>in</strong>fants: a randomized control trial. Indian Pediatrics 2004, 41:435-441.<br />

9

Tables and Figures<br />

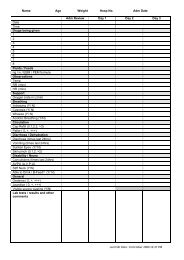

Box 1. Feed<strong>in</strong>g regimens for ‘early’ / ‘delayed’ and ‘slow’ / ‘rapid’ schedules<br />

No respiratory distress / asphyxia<br />

Significant respiratory distress†/ severe asphyxia‡<br />

Weight <<br />

1500g:<br />

‘Early’<br />

Feed<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Weight <<br />

1500g:<br />

‘Delayed’<br />

Feed<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Weight<br />

1500–1999g:<br />

‘Early’<br />

Feed<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Weight<br />

1500 –1999g:<br />

‘Delayed’<br />

Feed<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Start Feed<strong>in</strong>g: 3mls / 3 hrly from birth<br />

Incremental feed volume: Add 3mls to 3 hourly feed<br />

volume every 24 hour period from 24 hours <strong>of</strong> life until<br />

full feed volume achieved (e.g. at 24 hours feed = 6mls<br />

3hrly, at 48 hours = 9mls / 3hrly)<br />

Start Feed<strong>in</strong>g: 3mls / 3 hrly from 24 hours <strong>of</strong> age<br />

Incremental feed volume: Add 3mls to 3 hourly feed<br />

volume every 24 hour period from 72 hours <strong>of</strong> life until<br />

full feed volume achieved (e.g. at 72 hours feed = 6mls<br />

3hrly, at 96 hours = 9mls / 3hrly)<br />

Start Feed<strong>in</strong>g: Initiate full volume feeds appropriate for<br />

weight with<strong>in</strong> 3 hours <strong>of</strong> birth<br />

Start Feed<strong>in</strong>g: 6mls / 3 hrly from birth<br />

Incremental feed volume: Add 6mls to 3 hourly feed<br />

volume every 24 hour period from 24 hours <strong>of</strong> life until<br />

full feed volume achieved (e.g. at 24 hours feed = 12mls<br />

3hrly, at 48 hours = 18mls / 3hrly)<br />

Start Feed<strong>in</strong>g: 3mls / 3 hrly from 24 hours <strong>of</strong> age<br />

Incremental feed volume: Add 3mls to 3 hourly feed volume every 24<br />

hour period from 72 hours <strong>of</strong> life until full feed volume achieved (e.g.<br />

at 72 hours feed = 6mls 3hrly, at 96 hours = 9mls / 3hrly)<br />

Start Feed<strong>in</strong>g: 3mls / 3 hrly from 72 hours <strong>of</strong> age<br />

Incremental feed volume: Add 3mls to 3 hourly feed volume every 24<br />

hour period from 120 hours <strong>of</strong> life until full feed volume achieved<br />

(e.g. at 120 hours feed = 6mls 3hrly, at 144 hours = 9mls / 3hrly)<br />

Start Feed<strong>in</strong>g: 6mls / 3 hrly from birth<br />

Incremental feed volume: Add 6mls to 3 hourly feed volume every 24<br />

hour period from 24 hours <strong>of</strong> life until full feed volume achieved (e.g.<br />

at 24 hours feed = 12mls 3hrly, at 48 hours = 18mls / 3hrly)<br />

Start Feed<strong>in</strong>g: 6mls / 3 hrly from 24 hours<br />

Incremental feed volume: Add 6mls to 3 hourly feed volume every 24<br />

hour period from 72 hours <strong>of</strong> life until full feed volume achieved (e.g.<br />

at 72 hours feed = 12mls 3hrly, at 96 hours = 18mls / 3hrly)<br />

†Persistent severe hypoxaemia (SpO 2 rema<strong>in</strong>s

Table 1. Study selection criteria<br />

Design<br />

• Randomised or quasi-randomised controlled trials<br />

• Editorials, comments, and case-series were excluded<br />

Participants<br />

• Newborn <strong>in</strong>fants at high risk <strong>of</strong> <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong>tolerance or necrotis<strong>in</strong>g enterocolitis on the<br />

basis <strong>of</strong> low birth weight (

Figure 1. Flow diagram for selection <strong>of</strong> studies<br />

Identification<br />

Eligibility<br />

Included<br />

478<br />

Articles (after duplicates<br />

removed) identified through<br />

electronic and manual searches<br />

12<br />

Full-text articles assessed for<br />

<strong>in</strong>clusion<br />

6<br />

Papers <strong>in</strong>cluded†<br />

466 Articles excluded on<br />

screen<strong>in</strong>g titles and<br />

abstracts electronically<br />

6 Articles excluded<br />

4 Narrative reviews<br />

1 Without <strong>in</strong>tervention <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>terest<br />

† - 3 Cochrane reviews, 1 non-Cochrane review, 1 randomised<br />

controlled trial (RCT), and 1 unpublished RCT<br />

12

Table 2. GRADE evidence pr<strong>of</strong>ile<br />

Question: Delayed <strong>in</strong>troduction <strong>of</strong> progressive <strong>enteral</strong> feeds to prevent necrotis<strong>in</strong>g enterocolitis <strong>in</strong> very low birth weight <strong>in</strong>fants<br />

Intervention: Early <strong>in</strong>itiation (at a mean or median <strong>of</strong> ≤4 days) <strong>of</strong> <strong>enteral</strong> <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong>s <strong>of</strong> human milk or formula<br />

Comparison: Delayed <strong>in</strong>itiation (at a mean or median <strong>of</strong> >4 days) <strong>of</strong> <strong>enteral</strong> <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong>s <strong>of</strong> human milk or formula<br />

Sett<strong>in</strong>gs: Neonatal care units<br />

Bibliography: Bombell S, McGuire W. Delayed <strong>in</strong>troduction <strong>of</strong> progressive <strong>enteral</strong> feeds to prevent necrotis<strong>in</strong>g enterocolitis <strong>in</strong> very<br />

low birth weight <strong>in</strong>fants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008 Apr 16 ;( 2).<br />

Quality assessment<br />

Summary <strong>of</strong> f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs<br />

Effect size<br />

Quality††<br />

Importance<br />

No <strong>of</strong><br />

studies<br />

No <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>fants<br />

Design Limitations Inconsistency Indirectness Imprecision<br />

(95% CI)<br />

(GRADE)<br />

Mortality prior to discharge<br />

2 101 randomised<br />

controlled<br />

trials<br />

serious†<br />

no serious<br />

<strong>in</strong>consistency<br />

no serious<br />

<strong>in</strong>directness<br />

serious‡ RR 0.87<br />

(0.34 to<br />

2.28)<br />

⊕⊕<br />

LOW<br />

CRITICAL<br />

Necrotis<strong>in</strong>g enterocolitis (NEC)<br />

2 101 randomised<br />

controlled<br />

trials<br />

serious†<br />

no serious<br />

<strong>in</strong>consistency<br />

no serious<br />

<strong>in</strong>directness<br />

serious‡<br />

RR 1.27<br />

(0.54 to 3.0)<br />

⊕⊕<br />

LOW<br />

CRITICAL<br />

Weight ga<strong>in</strong> (g/kg/week)<br />

1 12 randomised<br />

controlled<br />

trial<br />

serious†<br />

no serious<br />

<strong>in</strong>consistency<br />

no serious<br />

<strong>in</strong>directness<br />

very<br />

serious‡<br />

WMD -1.00<br />

(-127.37 to<br />

125.37<br />

⊕<br />

VERY LOW<br />

IMPORTANT<br />

Duration <strong>of</strong> hospital admission (post-menstrual weeks at discharge)<br />

13

1 60 randomised<br />

controlled<br />

trial<br />

serious†<br />

no serious<br />

<strong>in</strong>consistency<br />

no serious<br />

<strong>in</strong>directness<br />

serious‡ MD 0.90<br />

(-1.21 to<br />

3.01)<br />

⊕⊕<br />

LOW<br />

IMPORTANT<br />

† - small sample sizes, no bl<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>tervention and outcome measurement; ‡ – few number <strong>of</strong> events<br />

††: Quality <strong>of</strong> evidence – the extent to which we can be confident that an estimate <strong>of</strong> effect or association is correct. The<br />

judgements are based on the: study design (randomised versus observational studies); likelihood <strong>of</strong> bias; consistency <strong>of</strong> the results<br />

across the studies; precision (wide or narrow confidence <strong>in</strong>tervals) <strong>of</strong> overall estimates and; directness <strong>of</strong> the evidence with respect<br />

to the populations, <strong>in</strong>terventions and sett<strong>in</strong>gs where the proposed <strong>in</strong>tervention may be used.<br />

Quality <strong>of</strong> evidence is categorized as ‘high’, ‘moderate’, ‘low’ or ‘very low’.<br />

• HIGH: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence <strong>in</strong> the estimate <strong>of</strong> effect.<br />

• MODERATE: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence <strong>in</strong> the estimate <strong>of</strong> effect and may<br />

change the estimate.<br />

• LOW: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence <strong>in</strong> the estimate <strong>of</strong> effect and is likely to<br />

change the estimate.<br />

• VERY LOW: We are very uncerta<strong>in</strong> about the estimate.<br />

14

Table 4. GRADE evidence pr<strong>of</strong>ile<br />

Question: Slow advancement <strong>of</strong> <strong>enteral</strong> feed volumes to prevent necrotis<strong>in</strong>g enterocolitis <strong>in</strong> very low birth weight <strong>in</strong>fants<br />

Intervention: Slow rates (up to 24 mls/kg/day) <strong>of</strong> advancement <strong>of</strong> <strong>enteral</strong> <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong><br />

Comparison: Faster rates <strong>of</strong> advancement <strong>of</strong> <strong>enteral</strong> <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong><br />

Sett<strong>in</strong>gs: Neonatal care units<br />

Bibliography: McGuire W, Bombell S. Slow advancement <strong>of</strong> <strong>enteral</strong> feed volumes to prevent necrotis<strong>in</strong>g enterocolitis <strong>in</strong> very low<br />

birth weight <strong>in</strong>fants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008 Apr 16.<br />

Quality assessment<br />

Summary <strong>of</strong> f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs<br />

Effect size<br />

Quality<br />

Importance<br />

No <strong>of</strong><br />

studies<br />

No <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>fants<br />

Design Limitations Inconsistency Indirectness Imprecision<br />

(95% CI)<br />

(GRADE)<br />

All cause mortality<br />

2 238 randomised<br />

controlled<br />

trials<br />

serious†<br />

no serious<br />

<strong>in</strong>consistency<br />

no serious<br />

<strong>in</strong>directness<br />

serious‡ RR 1.40<br />

(0.71 to<br />

2.80)<br />

⊕⊕<br />

LOW<br />

CRITICAL<br />

Necrotis<strong>in</strong>g enterocolitis (NEC)<br />

3 396 randomised<br />

controlled<br />

trials<br />

no serious<br />

limitations<br />

no serious<br />

<strong>in</strong>consistency<br />

no serious<br />

<strong>in</strong>directness<br />

serious‡ RR 0.96<br />

(0.48 to<br />

1.92)<br />

⊕⊕<br />

LOW<br />

CRITICAL<br />

Feeds <strong>in</strong>tolerance (caus<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>terruption <strong>of</strong> <strong>enteral</strong> <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong>)<br />

1 53 randomised<br />

controlled<br />

trial<br />

serious<br />

no serious<br />

<strong>in</strong>consistency<br />

no serious<br />

<strong>in</strong>directness<br />

serious‡ RR 1.26<br />

(0.8 to 1.99<br />

⊕⊕⊕<br />

MODERATE<br />

IMPORTANT<br />

Duration <strong>of</strong> hospital stay (days)<br />

15

2 343 randomised<br />

controlled<br />

trials<br />

serious†<br />

no serious<br />

<strong>in</strong>consistency<br />

no serious<br />

<strong>in</strong>directness<br />

no serious<br />

imprecision<br />

NSD<br />

⊕⊕⊕<br />

MODERATE<br />

IMPORTANT<br />

Time to rega<strong>in</strong> birth weight<br />

3 396 randomised<br />

controlled<br />

trials<br />

serious†<br />

no serious<br />

<strong>in</strong>consistency<br />

no serious<br />

<strong>in</strong>directness<br />

no serious<br />

imprecision<br />

Longer <strong>in</strong><br />

slow rate<br />

group<br />

(range: 2 to<br />

5 days)<br />

⊕⊕⊕<br />

MODERATE<br />

IMPORTANT<br />

† – parents, care givers, and <strong>in</strong>vestigators were aware <strong>of</strong> allocated <strong>in</strong>terventions; ‡ – few number <strong>of</strong> events (n=24 deaths, 29 cases<br />

<strong>of</strong> NEC, 31 cases <strong>of</strong> <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong>tolerance); - small sample size; NSD – no statistically significant difference <strong>in</strong> the duration <strong>of</strong> hospital<br />

stay between slow and fast advancement groups<br />

16

Table 5. GRADE evidence pr<strong>of</strong>ile<br />

Question: Impact <strong>of</strong> standardised <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> regimens on the <strong>in</strong>cidence <strong>of</strong> neonatal necrotis<strong>in</strong>g enterocolitis: a systematic review and<br />

meta-analysis<br />

Sett<strong>in</strong>gs: Neonatal care units<br />

Bibliography: Patole SK, de Klerk N. Impact <strong>of</strong> standardised <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> regimens on <strong>in</strong>cidence <strong>of</strong> neonatal necrotis<strong>in</strong>g enterocolitis: a<br />

systematic review and meta-analysis <strong>of</strong> observational studies. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2005 Mar; 90(2):F147-51.<br />

Quality assessment<br />

Summary <strong>of</strong> f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs<br />

Risk ratio<br />

Quality<br />

Importance<br />

No <strong>of</strong><br />

studies<br />

No <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>fants<br />

Design Limitations Inconsistency Indirectness Imprecision<br />

(95% CI)<br />

(GRADE)<br />

Incidence <strong>of</strong> necrotis<strong>in</strong>g enterocolitis (NEC)<br />

6 9,453 observational<br />

studies<br />

no serious<br />

limitations<br />

no serious<br />

<strong>in</strong>consistency<br />

no serious<br />

<strong>in</strong>directness<br />

no serious<br />

<strong>in</strong>directness<br />

0.13 (0.03<br />

to 0.50)<br />

⊕⊕⊕<br />

MODERATE<br />

CRITICAL<br />

17

Table 6. GRADE evidence pr<strong>of</strong>ile<br />

Question: Slow versus rapid <strong>enteral</strong> <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> advancement <strong>in</strong> <strong>preterm</strong> newborn <strong>in</strong>fants 1000-1499 g: a randomised controlled trial<br />

Intervention: Rapid <strong>enteral</strong> <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> (expressed human milk or formula) advancement at 30 mL/kg/day<br />

Comparison: Slow <strong>enteral</strong> <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> (expressed human milk or formula) advancement at 20 mL/kg/day<br />

Sett<strong>in</strong>gs: Neonatal care units<br />

Bibliography: Krishnamurthy S, Gupta P, Debnath S, Gomber S. Slow versus rapid <strong>enteral</strong> <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> advancement <strong>in</strong> <strong>preterm</strong><br />

newborn <strong>in</strong>fants 1000-1499 g: a randomized controlled trial. Acta Paediatr. 2010 Jan; 99(1):42-6.<br />

Quality assessment<br />

Summary <strong>of</strong> f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs<br />

Effect size<br />

Quality<br />

Importance<br />

No <strong>of</strong><br />

studies<br />

No <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>fants<br />

Design Limitations Inconsistency Indirectness Imprecision<br />

(95% CI)<br />

(GRADE)<br />

Mortality<br />

1 100 randomised<br />

controlled<br />

trial<br />

serious†<br />

no serious<br />

<strong>in</strong>consistency<br />

no serious<br />

<strong>in</strong>directness<br />

serious‡<br />

NSD<br />

⊕⊕<br />

LOW<br />

CRITICAL<br />

Necrotis<strong>in</strong>g enterocolitis (NEC)<br />

1 100 randomised<br />

controlled<br />

trial<br />

serious†<br />

no serious<br />

<strong>in</strong>consistency<br />

no serious<br />

<strong>in</strong>directness<br />

serious‡<br />

NSD<br />

⊕⊕<br />

LOW<br />

CRITICAL<br />

Days to rega<strong>in</strong> birth weight<br />

1 100 randomised<br />

controlled<br />

trial<br />

serious†<br />

no serious<br />

<strong>in</strong>consistency<br />

no serious<br />

<strong>in</strong>directness<br />

serious‡<br />

Earlier <strong>in</strong><br />

rapid<br />

group‡‡<br />

⊕⊕<br />

LOW<br />

IMPORTANT<br />

Length <strong>of</strong> hospital stay (days)<br />

18

1 100 randomised<br />

controlled<br />

trial<br />

serious†<br />

no serious<br />

<strong>in</strong>consistency<br />

no serious<br />

<strong>in</strong>directness<br />

serious‡<br />

Shorter <strong>in</strong><br />

rapid<br />

group††<br />

⊕⊕<br />

LOW<br />

IMPORTANT<br />

† – small sample size, n=100 <strong>in</strong>fants; ‡ – few number <strong>of</strong> events; NSD – no statistically significant difference <strong>in</strong> mortality between slow<br />

and fast groups; ‡‡ median 16 days versus 22 days, p

Table 7. GRADE evidence pr<strong>of</strong>ile<br />

Question: Effect <strong>of</strong> a standardised <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> regimen on early neonatal growth <strong>in</strong> low and very low birth weight neonates at Kenyatta<br />

National Hospital: a pilot randomised controlled trial<br />

Sett<strong>in</strong>gs: Neonatal care units<br />

Bibliography: Ngetich E, Were FN, English M, Musoke RN. Effect <strong>of</strong> a standardised <strong>feed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> regimen on early neonatal growth <strong>in</strong><br />

low and very low birth weight neonates at Kenyatta National Hospital: a pilot randomised controlled trial. Unpublished MMed thesis,<br />

2009.<br />

Quality assessment<br />

Summary <strong>of</strong> f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs<br />

Effect size<br />

Quality<br />

Importance<br />

No <strong>of</strong><br />

studies<br />

No <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>fants<br />

Design Limitations Inconsistency Indirectness Imprecision<br />

(GRADE)<br />

Mortality<br />

1 13 randomised<br />

controlled<br />

trial<br />

serious†<br />

no serious<br />

<strong>in</strong>consistency<br />

no serious<br />

<strong>in</strong>directness<br />

serious† CFR 18.9%<br />

versus SFR<br />

17.4%<br />

⊕⊕<br />

LOW<br />

CRITICAL<br />

Necrotis<strong>in</strong>g enterocolitis (NEC)<br />

1 6 randomised<br />

controlled<br />

trial<br />

serious†<br />

no serious<br />

<strong>in</strong>consistency<br />

no serious<br />

<strong>in</strong>directness<br />

serious† CFR 8.1%<br />

versus SFR<br />

8.6%<br />

⊕⊕<br />

LOW<br />

CRITICAL<br />

Mean weight ga<strong>in</strong>, g/kg/day<br />

1 55 randomised<br />

controlled<br />

trial<br />

serious†<br />

no serious<br />

<strong>in</strong>consistency<br />

no serious<br />

<strong>in</strong>directness<br />

serious† CFR 9.8<br />

versus<br />

SFR 14.1<br />

p

Time to atta<strong>in</strong> full feeds (mean days)<br />

1 55 randomised<br />

controlled<br />

trial<br />

serious†<br />

no serious<br />

<strong>in</strong>consistency<br />

no serious<br />

<strong>in</strong>directness<br />

serious† CFR 7.0<br />

versus<br />

SFR 5.6<br />

p