Annual Conference of the International Wader Study Group, Séné ...

Annual Conference of the International Wader Study Group, Séné ...

Annual Conference of the International Wader Study Group, Séné ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Annual</strong> <strong>Conference</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>International</strong> <strong>Wader</strong> <strong>Study</strong><br />

<strong>Group</strong>, Séné, France, 21–24 September 2012<br />

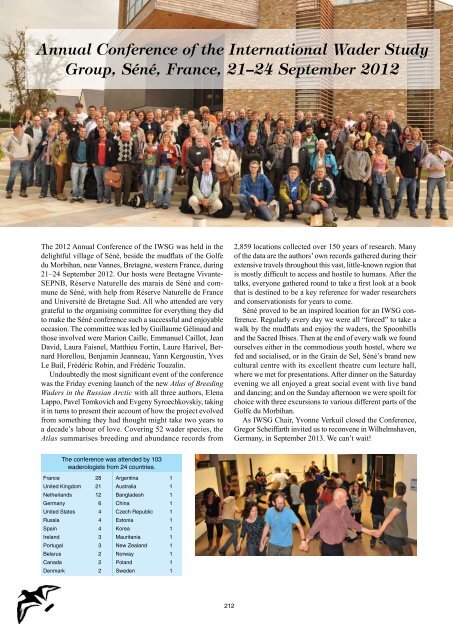

The 2012 <strong>Annual</strong> <strong>Conference</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> IWSG was held in <strong>the</strong><br />

delightful village <strong>of</strong> Séné, beside <strong>the</strong> mudflats <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Golfe<br />

du Morbihan, near Vannes, Bretagne, western France, during<br />

21–24 September 2012. Our hosts were Bretagne Vivante-<br />

SEPNB, Réserve Naturelle des marais de Séné and commune<br />

de Séné, with help from Réserve Naturelle de France<br />

and Université de Bretagne Sud. All who attended are very<br />

grateful to <strong>the</strong> organising committee for everything <strong>the</strong>y did<br />

to make <strong>the</strong> Séné conference such a successful and enjoyable<br />

occasion. The committee was led by Guillaume Gélinaud and<br />

those involved were Marion Caille, Emmanuel Caillot, Jean<br />

David, Laura Faisnel, Matthieu Fortin, Laure Harivel, Bernard<br />

Horellou, Benjamin Jeanneau, Yann Kergoustin, Yves<br />

Le Bail, Frédéric Robin, and Frédéric Touzalin.<br />

Undoubtedly <strong>the</strong> most significant event <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> conference<br />

was <strong>the</strong> Friday evening launch <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> new Atlas <strong>of</strong> Breeding<br />

<strong>Wader</strong>s in <strong>the</strong> Russian Arctic with all three authors, Elena<br />

Lappo, Pavel Tomkovich and Evgeny Syroechkovskiy, taking<br />

it in turns to present <strong>the</strong>ir account <strong>of</strong> how <strong>the</strong> project evolved<br />

from something <strong>the</strong>y had thought might take two years to<br />

a decade’s labour <strong>of</strong> love. Covering 52 wader species, <strong>the</strong><br />

Atlas summarises breeding and abundance records from<br />

2,859 locations collected over 150 years <strong>of</strong> research. Many<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> data are <strong>the</strong> authors’ own records ga<strong>the</strong>red during <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

extensive travels throughout this vast, little-known region that<br />

is mostly difficult to access and hostile to humans. After <strong>the</strong><br />

talks, everyone ga<strong>the</strong>red round to take a first look at a book<br />

that is destined to be a key reference for wader researchers<br />

and conservationists for years to come.<br />

Séné proved to be an inspired location for an IWSG conference.<br />

Regularly every day we were all “forced” to take a<br />

walk by <strong>the</strong> mudflats and enjoy <strong>the</strong> waders, <strong>the</strong> Spoonbills<br />

and <strong>the</strong> Sacred Ibises. Then at <strong>the</strong> end <strong>of</strong> every walk we found<br />

ourselves ei<strong>the</strong>r in <strong>the</strong> commodious youth hostel, where we<br />

fed and socialised, or in <strong>the</strong> Grain de Sel, Séné’s brand new<br />

cultural centre with its excellent <strong>the</strong>atre cum lecture hall,<br />

where we met for presentations. After dinner on <strong>the</strong> Saturday<br />

evening we all enjoyed a great social event with live band<br />

and dancing; and on <strong>the</strong> Sunday afternoon we were spoilt for<br />

choice with three excursions to various different parts <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Golfe du Morbihan.<br />

As IWSG Chair, Yvonne Verkuil closed <strong>the</strong> <strong>Conference</strong>,<br />

Gregor Scheiffarth invited us to reconvene in Wilhelmshaven,<br />

Germany, in September 2013. We can’t wait!<br />

The conference was attended by 103<br />

waderologists from 24 countries.<br />

France 28 Argentina 1<br />

United Kingdom 21 Australia 1<br />

Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands 12 Bangladesh 1<br />

Germany 6 China 1<br />

United States 4 Czech Republic 1<br />

Russia 4 Estonia 1<br />

Spain 4 Korea 1<br />

Ireland 3 Mauritania 1<br />

Portugal 3 New Zealand 1<br />

Belarus 2 Norway 1<br />

Canada 2 Poland 1<br />

Denmark 2 Sweden 1<br />

212

f<br />

Abstracts <strong>of</strong> <strong>Conference</strong> Talks<br />

Demography<br />

e<br />

Spatio-temporal variation in <strong>the</strong> survival <strong>of</strong><br />

Red Knots Calidris canutus islandica<br />

centred on <strong>the</strong> Wadden Sea<br />

Eldar Rakhimberdiev 1,2,3 , Piet J. van den Hout 1 ,<br />

Bernard Spaans 1 & Theunis Piersma 1,4<br />

1<br />

NIOZ Royal Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands Institute for Sea Research, Texel,<br />

The Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands; eldar.rakhimberdiev@nioz.nl<br />

2<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> Vertebrate Zoology, Biological Faculty,<br />

Lomonosov Moscow State University, Moscow, Russia<br />

3<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> Ecology and Evolutionary Biology,<br />

Cornell University, Ithaca, USA<br />

4<br />

Animal Ecology <strong>Group</strong>, Centre for Ecological and Evolutionary<br />

Studies, University <strong>of</strong> Groningen, Groningen, The Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands<br />

The estimation <strong>of</strong> demographic parameters within a capture–<br />

recapture framework has now become common practice. The<br />

most important parameter obtained from capture–recapture<br />

analysis, annual survival, is regarded as a good indicator <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> conservation status <strong>of</strong> a population. In <strong>the</strong> case <strong>of</strong> highly<br />

mobile animals such as migrating birds, annual survival is<br />

an important and interesting vital statistic to know, but it<br />

lacks information on where in <strong>the</strong> annual cycle and where<br />

in space <strong>the</strong> population suffers <strong>the</strong> greatest losses. Currently,<br />

only a handful <strong>of</strong> studies have looked at seasonal and spatial<br />

variation in <strong>the</strong> survival <strong>of</strong> migrants. Here we use mark–<br />

resight data over a period <strong>of</strong> 15 years to estimate space- and<br />

time-dependent variation in survival <strong>of</strong> Red Knots Calidris<br />

canutus islandica breeding in Arctic Canada and Greenland<br />

and wintering in Europe. Birds were ringed primarily in <strong>the</strong><br />

Wadden Sea (<strong>the</strong> Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands) but were resighted at all staging<br />

and stopover areas except <strong>the</strong> breeding grounds. We estimated<br />

adult survival in <strong>the</strong> following framework: (1) <strong>Annual</strong><br />

apparent survival for <strong>the</strong> whole population according to <strong>the</strong><br />

CJS model indicated a strong (and previously undetected)<br />

decline in <strong>the</strong> islandica population. (2) Seasonal apparent<br />

survival (CJS model) indicated that <strong>the</strong> autumn and winter<br />

periods are <strong>the</strong> most critical (i.e. <strong>the</strong> seasons with <strong>the</strong> lowest<br />

survival rate). (3) Season–site true survival estimates using<br />

multi-strata modelling will show <strong>the</strong> places where autumn<br />

and winter survival is worst. This approach will enable us<br />

to quantify not only true survival, but also emigration rates,<br />

which in turn will tell us whe<strong>the</strong>r knots have started to bypass<br />

areas with low survival.<br />

A chance for Kentish Plover populations in <strong>the</strong><br />

Wadden Sea? Habitat selection and population<br />

dynamics <strong>of</strong> Kentish Plovers in N Germany<br />

Hermann Hötker, Dominic Cimiotti,<br />

Brigitte Klinner-Hötker & Rainer Schulz<br />

Michael-Otto-Institut im NABU; Hermann.Hoetker@NABU.de<br />

Kentish Plover Charadrius alexandrinus is <strong>the</strong> most threatened<br />

bird species that breeds in <strong>the</strong> German Wadden Sea.<br />

Most <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> remaining 180–250 pairs are found on recently<br />

claimed polders on <strong>the</strong> coast <strong>of</strong> Schleswig-Holstein. Although<br />

most nests are found in inland habitats, <strong>the</strong> birds forage on<br />

intertidal mudflats and sandflats. An analysis <strong>of</strong> nest habitat<br />

choice showed that distance to intertidal feeding grounds,<br />

vegetation structure (a mosaic <strong>of</strong> bare ground and different<br />

vegetation types) and <strong>the</strong> size <strong>of</strong> breeding sites significantly<br />

affected <strong>the</strong> abundance <strong>of</strong> Kentish Plovers. In recent years,<br />

breeding success has been high enough in most sites to<br />

balance mortality, but in some sites Kentish Plovers have<br />

suffered from high rates <strong>of</strong> nest predation and flooding. At<br />

present, <strong>the</strong> population seems to be limited by <strong>the</strong> availability<br />

<strong>of</strong> suitable breeding sites. Measures taken to enlarge <strong>the</strong> area<br />

<strong>of</strong> suitable breeding habitat have shown some success.<br />

Ecology and spatial patterns<br />

Adult sex-ratio variation in Red Knots Calidris<br />

canutus rufa at non-breeding and stopover sites<br />

Patricia Gonzalez 1 , Allan Baker 2 , Larry Niles 3 ,<br />

Amanda Dey 4 , Kevin Kalasz 5 , Yves Aubry 6 ,<br />

Christoph Buidin 7 & Yann Rochepault 7<br />

1<br />

Fundacion Inalafquen and Global Flyway Network, San Antonio<br />

Oeste, Rio Negro, Argentina; ccanutus@gmail.com<br />

2<br />

Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto ON Canada<br />

3<br />

Conserve NJ Wildlife, NJ, USA<br />

4<br />

Division <strong>of</strong> Fish and Wildlife, NJ Dept. <strong>of</strong> Environmental<br />

Protection, NJ, USA<br />

5<br />

Division <strong>of</strong> Fish and Wildlife, DE USA<br />

6<br />

Canadian Wildlife Service, Quebec Region,<br />

Environment Canada, Quebec, QC, Canada<br />

7<br />

Riviere-St-Jean, Quebec, Canada<br />

Adult sex ratios are commonly skewed from equality in<br />

birds, and are thought to reflect sex-biased mortality ra<strong>the</strong>r<br />

than skewed <strong>of</strong>fspring sex-ratios. We investigated adult sexratios<br />

using molecular sexing <strong>of</strong> migratory populations <strong>of</strong> Red<br />

Knots Calidris canutus rufa sampled at <strong>the</strong> Delaware Bay,<br />

USA, stopover site, and show that from 2004–2010 males predominated<br />

in cannon net catches. The male skew in <strong>the</strong> Bay<br />

could possibly arise from higher female than male mortality,<br />

a skewed male primary sex-ratio, shorter stopover duration<br />

<strong>of</strong> females than males, females skipping breeding seasons or<br />

bypassing <strong>the</strong> Bay en route to <strong>the</strong> Arctic, or by differential<br />

catchability <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> sexes. In contrast, sex-ratios in catches<br />

made at Rio Grande, Tierra del Fuego, a non-breeding site,<br />

and at San Antonio Oeste, Argentina, a northward migration<br />

stopover site, are balanced in most years or have a significant<br />

male or female skew in o<strong>the</strong>r years. Following <strong>the</strong> good<br />

2011 breeding season, a sample <strong>of</strong> 100 juveniles captured in<br />

<strong>the</strong> Mingan Archipelago, Gulf <strong>of</strong> St Lawrence, Canada, on<br />

southward migration showed a balanced sex-ratio, but both<br />

female- and male-skewed samples <strong>of</strong> juveniles have been<br />

obtained in Argentina and Chile in different years. Adult<br />

213

214 <strong>Wader</strong> <strong>Study</strong> <strong>Group</strong> Bulletin 119(3) 2012<br />

sex-ratios at o<strong>the</strong>r non-breeding sites in Maranhão, N Brazil,<br />

and in Florida, USA, seem to be balanced. We conclude that<br />

adult sex ratios are very difficult to quantify without large<br />

samples, and are likely to be affected by multiple causes in<br />

long distance migrants.<br />

Genetic differentiation among <strong>the</strong> three<br />

major wintering populations <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Red Knot<br />

Calidris canutus rufa<br />

Allan Baker 1 , Erika Tavares 1 , Patricia Gonzalez 2 ,<br />

Oliver Haddrath 1 , Kristen Ch<strong>of</strong>fe 1 & Larry Niles 3<br />

1<br />

Dept. <strong>of</strong> Natural History, Royal Ontario Museum,<br />

Toronto, ON Canada; allanb@rom.on.ca<br />

2<br />

Fundacion Inalafquen, San Antonio Oeste, Rio Negro, Argentina<br />

3<br />

Conserve NJ Wildlife, 109 Market Lane, Greenwich, NJ 08323,<br />

USA<br />

To determine whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> populations <strong>of</strong> Red Knots wintering<br />

in Tierra del Fuego, Maranhao and Florida were differentiated<br />

genetically, we assayed variation in a MHC class II locus, 10<br />

microsatellites, and 461 loci detected with amplified fragment<br />

length polymorphisms (AFLP). Only <strong>the</strong> high resolution<br />

AFLP which fingerprint individuals were able to clearly separate<br />

<strong>the</strong> three populations. This finding implies that individuals<br />

have high fidelity to wintering sites, and probably breed in<br />

distinct areas in <strong>the</strong> Arctic. Most importantly, fragmentation<br />

into three populations supports listing <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> subspecies C. c.<br />

rufa as endangered, primarily due to <strong>the</strong> higher demographic<br />

risks associated with smaller population sizes.<br />

Variation in wader community structure along<br />

environmental gradients<br />

V. Mendez 1 , J.A. Gill 1 , N.H.K. Burton 2 & R.G. Davies 1<br />

1<br />

University <strong>of</strong> East Anglia, Norwich, UK; v.mendez@uea.ac.uk<br />

2<br />

British Trust for Ornithology, Thetford, Norfolk, UK<br />

Understanding <strong>the</strong> consequences <strong>of</strong> changes in biodiversity<br />

under global climate change for ecosystem functions and<br />

services is an issue <strong>of</strong> increasing concern. The ecological<br />

functions provided by any community are thought to be<br />

dependent on <strong>the</strong> diversity <strong>of</strong> functional traits, also known<br />

as functional diversity, represented by <strong>the</strong> species present.<br />

<strong>Study</strong>ing patterns <strong>of</strong> community functional diversity can aid<br />

in our understanding <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> processes by which communities<br />

assemble. <strong>Wader</strong> communities are under continuous<br />

anthropogenic pressures (direct and indirect) during winter,<br />

when <strong>the</strong>y mostly depend on estuarine systems, one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

most threatened ecosystems in <strong>the</strong> world. In order to maintain<br />

natural communities and monitor <strong>the</strong>ir responses to environmental<br />

change, it is important to understand <strong>the</strong> mechanisms<br />

that regulate community assembly, species coexistence, and<br />

whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong>ir influence on community structure varies along<br />

environmental gradients.<br />

In this study, we use a long-term dataset on wader species<br />

distributions to investigate spatial and temporal patterns<br />

<strong>of</strong> community structure and functional diversity across UK<br />

estuaries in relation to environmental gradients. From all <strong>the</strong><br />

environmental variables considered, tidal range and minimum<br />

winter temperature were <strong>the</strong> factors that accounted for <strong>the</strong><br />

largest portions <strong>of</strong> variation in community structure across<br />

estuaries, followed by longitude and fetch (a measure <strong>of</strong> turbidity).<br />

Additionally, communities found in sandier estuaries<br />

appear to be becoming more similar through time, suggesting<br />

that <strong>the</strong> factors structuring communities are also changing. We<br />

will discuss <strong>the</strong>se findings in terms <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> likely mechanisms<br />

driving both spatial and temporal community patterns, and<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir implications for understanding <strong>the</strong> functional response<br />

<strong>of</strong> estuarine wader communities to environmental change.<br />

Geographical patterns in primary moult and<br />

body mass <strong>of</strong> Greenshanks Tringa nebularia<br />

staying in sou<strong>the</strong>rn Africa<br />

Magdalena Remisiewicz 1,2 , Anthony J. Tree 3 &<br />

Les G. Underhill 2,4<br />

1<br />

Avian Ecophysiology Unit, Department <strong>of</strong> Vertebrate Ecology<br />

and Zoology, University <strong>of</strong> Gdansk, al. Legionow 9, 80-441<br />

Gdansk, Poland; biomr@univ.gda.pl<br />

2<br />

Animal Demography Unit, Department <strong>of</strong> Zoology,<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Cape Town, Rondebosch 7701, South Africa<br />

3<br />

PO Box 2793, Port Alfred, 6170, South Africa<br />

4<br />

Marine Research Institute, University <strong>of</strong> Cape Town,<br />

Rondebosch 7701, South Africa<br />

Greenshanks show varied patterns <strong>of</strong> primary moult during<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir migration and stay in <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn hemisphere. Their<br />

moult fur<strong>the</strong>r south is known fragmentarily because <strong>of</strong> data<br />

shortage. We aimed to identify geographical patterns in primary<br />

moult and pre-migratory fattening <strong>of</strong> Greenshanks <strong>of</strong><br />

different age within <strong>the</strong>ir sou<strong>the</strong>rnmost African non-breeding<br />

grounds. We analysed primary moult and body mass <strong>of</strong> 356<br />

Greenshanks caught at inland wetlands <strong>of</strong> Zimbabwe, and on<br />

<strong>the</strong> east coast and west coast <strong>of</strong> South Africa from 1968 to<br />

1998, using Underhill–Zucchini moult models (1988). About<br />

20% <strong>of</strong> immatures replaced 1–5 outer primaries between<br />

December and May, which is rare in <strong>the</strong> north. Sub-adults<br />

moulted all primaries on average 40 days earlier but at <strong>the</strong><br />

same rate as adults. Most adults moulted continuously all<br />

10 primaries. Their moult started on average 19 days earlier<br />

(4 Sep) and took 17 days longer (122 days) on <strong>the</strong> east coast<br />

than on <strong>the</strong> west coast (23 Sep, 105 days), in Zimbabwe moult<br />

start date was close to <strong>the</strong> east coast (7 Sep, 115 days). Moult<br />

starts probably following a broad front arrival by Greenshanks<br />

in Zimbabwe and on <strong>the</strong> east coast, and later arrival<br />

on <strong>the</strong> west coast. But <strong>the</strong> end <strong>of</strong> moult was synchronised to<br />

within six days (31 Dec–6 Jan), and pre-migratory fattening<br />

began about 13–19 Jan in all three regions. The mean<br />

departure weights <strong>of</strong> adults were 238 g in Zimbabwe, 278 g<br />

on <strong>the</strong> west coast, and 298 g on <strong>the</strong> east coast. This suggests<br />

that coastal wetlands provide Greenshanks with richer food<br />

resources than those <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> interior. The heaviest adults from<br />

all regions could reach <strong>the</strong> Nile Valley or Mediterranean coast<br />

in one flight. We suggest that Greenshanks staying inland<br />

benefit from abundant food during <strong>the</strong> entire austral summer<br />

in some years, a shorter migration distance and lower<br />

competition than at <strong>the</strong> coasts, with a backup <strong>of</strong> a potential<br />

movement to <strong>the</strong> coast if conditions deteriorate.

IWSG <strong>Annual</strong> <strong>Conference</strong><br />

215<br />

Hunting moratorium on Eurasian Curlew<br />

Numenius arquata in France (2008–2012):<br />

possible effects at different spatial levels<br />

P. Delaporte 1 , F. Robin 1 , V. Lelong 1 , E. Caillot 2 ,<br />

F. Corre 1 , N. Boileau & P. Bocher 3<br />

1<br />

Ligue Pour la Protection des Oiseaux, Les Fonderies Royales,<br />

5 Rue Docteur Pujos, 17300 Rochefort Sur Mer,<br />

France; vincent.lelong@lpo.fr<br />

2<br />

Réserve Naturelle de France. – 6,<br />

bis rue de la Gouge – BP 100 – 21803 Quetigny cedex<br />

3<br />

Laboratory Littoral Environnement et Sociétés UMR LIENSs 7266<br />

CNRS-University <strong>of</strong> La Rochelle, 2 rue Olympe de Gouges,<br />

17000 La Rochelle, France<br />

Since July 2008, <strong>the</strong> hunting <strong>of</strong> Eurasian Curlew Numenius<br />

arquata has been banned in France. We investigate possible<br />

effects <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> moratorium on curlew numbers at staging and<br />

wintering coastal areas by comparing numbers before and<br />

after 2008. We used mid-winter counts at <strong>the</strong> national level<br />

and for <strong>the</strong> regional level, we use monthly counts from all<br />

staging and wintering sites from August to March (Observatoire<br />

des Limicoles Côtiers). We also focus on <strong>the</strong> Nature<br />

Reserve <strong>of</strong> Moëze-Oléron (Atlantic coast) where curlews<br />

have been studied since 2001 using a colour ringing scheme.<br />

The numbers <strong>of</strong> curlew wintering in France have shown an<br />

increase since <strong>the</strong> moratorium was introduced with regional<br />

variations between <strong>the</strong> Channel and Atlantic coasts. At a local<br />

level, curlews have responded to less hunting disturbance by<br />

changing <strong>the</strong>ir spatial distribution in <strong>the</strong> bay at Moëze-Oléron<br />

at both low tide and high tide. We have also found that since<br />

<strong>the</strong> moratorium <strong>the</strong> body condition <strong>of</strong> birds in January and<br />

February has improved suggesting that feeding conditions<br />

have improved. This might be a consequence <strong>of</strong> better access<br />

to high quality feeding areas now that <strong>the</strong>y are free <strong>of</strong> hunting<br />

disturbance and/or <strong>the</strong> result <strong>of</strong> a reduction in stress and<br />

wasted energy costs caused by flying to escape <strong>the</strong> hunters.<br />

More studies are required on <strong>the</strong> spatial, ecological and functional<br />

responses <strong>of</strong> curlews to <strong>the</strong> hunting moratorium in order<br />

to assess <strong>the</strong> effectiveness <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> measure. We recommend<br />

ano<strong>the</strong>r five years <strong>of</strong> moratorium to allow <strong>the</strong> development<br />

<strong>of</strong> such studies.<br />

Foraging ecology<br />

Relationship between microphytobenthos and<br />

feeding behaviour <strong>of</strong> Dunlin Calidris alpina, a<br />

shorebird wintering in Bourgneuf Bay<br />

Sigrid Drouet 1 , Priscilla Decottignies 1 , Vincent Turpin 1 ,<br />

Gwenaëlle Quaintenne 1 , Pierrick Bocher 2 &<br />

Richard Cosson 1<br />

1<br />

LUNAM université, Université de Nantes, MMS (EA2160), 44322<br />

Nantes Cedex 03, France; sigrid.drouet@univ-nantes.fr<br />

2<br />

Laboratory Littoral Environnement et Sociétés UMR LIENSs 7266<br />

CNRS-University <strong>of</strong> La Rochelle, 2 rue Olympe de Gouges,<br />

17000 La Rochelle, France<br />

Intertidal mudflats in bays and estuaries are among <strong>the</strong><br />

world’s most productive ecosystems. Characteristically <strong>the</strong>y<br />

have high biodiversity and many are areas <strong>of</strong> international<br />

importance for waterbird conservation. Many species <strong>of</strong><br />

ducks and waders are dependent on <strong>the</strong>m during all or a large<br />

proportion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir life cycles because <strong>the</strong>y provide abundant<br />

and accessible food resources for winter survival and/or to<br />

fulfil <strong>the</strong> energetic requirements <strong>of</strong> long-distance migration.<br />

Recently, previously unrecorded feeding behaviour by a<br />

group <strong>of</strong> wader species has highlighted <strong>the</strong> key role in estuarine<br />

food webs <strong>of</strong> microphytobenthic bi<strong>of</strong>ilm. This organic<br />

material develops at <strong>the</strong> mud surface and has proved to be a<br />

key food resource for some waders. This throws into question<br />

<strong>the</strong> trophic level at which waders feed because previously<br />

<strong>the</strong>y were always assumed to be secondary consumers.<br />

In this study we investigated <strong>the</strong> relationship between<br />

waders and microphytobenthic food resources in Bourgneuf<br />

Bay on <strong>the</strong> Atlantic coast <strong>of</strong> France. This is an area in which<br />

microphytobenthic bi<strong>of</strong>ilm achieves high biomass and has<br />

been shown to be important as a food resource for oyster<br />

farming. In our studies we used stable isotope techniques to<br />

assess <strong>the</strong> importance <strong>of</strong> microphytobenthic bi<strong>of</strong>ilm grazing<br />

in <strong>the</strong> diet <strong>of</strong> wintering Dunlin Calidris alpina.<br />

Functional response curve <strong>of</strong><br />

Bar-tailed Godwits foraging on lugworms<br />

Sjoerd Duijns 1 , Ineke Knot 1 , Jan A. van Gils 1 &<br />

Theunis Piersma 1,2<br />

1<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> Marine Ecology, NIOZ Royal Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands<br />

Institute for Sea Research, PO Box 59, 1790 AB Den Burg,<br />

Texel, The Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands; sjoerd.duijns@nioz.nl<br />

2<br />

Animal Ecology <strong>Group</strong>, Centre for Ecological and<br />

Evolutionary Studies, University <strong>of</strong> Groningen, PO Box 11103,<br />

9700 CC Groningen, The Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands<br />

During <strong>the</strong> last decade <strong>the</strong> composition <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Wadden Sea’s<br />

waterbird populations has changed drastically. Bivalve predators<br />

such as Red Knot, Eurasian Oystercatcher and Common<br />

Eider have declined in numbers, whereas polychaete predators<br />

have increased (e.g. Bar-tailed Godwit, Dunlin and Grey<br />

Plover), suggesting links with changes in <strong>the</strong> benthic fauna.<br />

However, fur<strong>the</strong>r studies are needed to explain <strong>the</strong>se changes.<br />

These need to be based on <strong>the</strong> densities <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> birds on <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

feeding grounds and <strong>the</strong> densities <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir food where <strong>the</strong>y<br />

feed and <strong>the</strong> function that links <strong>the</strong>m, i.e. <strong>the</strong> functional<br />

response. The type II functional response cannot be measured<br />

with any accuracy in <strong>the</strong> field, as birds avoid feeding on very<br />

low densities <strong>of</strong> food, moreover <strong>the</strong>y seldom feed where<br />

<strong>the</strong>re are high food densities as such sites are rare. In this<br />

study we determined <strong>the</strong> functional response <strong>of</strong> female Bartailed<br />

Godwits in captivity. During spring migration, females<br />

mainly feed on lugworms Arenicola marina and in order to<br />

explain why intake rates in <strong>the</strong> field declined with increasing<br />

densities <strong>of</strong> female Bar-tailed Godwits, we hypo<strong>the</strong>sized<br />

that probing would induce lugworms to bury deeper. In a<br />

controlled experiment we found that this was indeed <strong>the</strong> case.<br />

Simulated probing led to an increase in <strong>the</strong> burying depth <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> lugworms and <strong>the</strong> captive female Bar-tailed Godwits had<br />

increased searching and handling times and consequently<br />

decreased intake rates.

216 <strong>Wader</strong> <strong>Study</strong> <strong>Group</strong> Bulletin 119(3) 2012<br />

Breeding ecology<br />

Unequal division <strong>of</strong> incubation<br />

in a High Arctic shorebird<br />

Martin Bulla, Anne Rutten, Alexander Girg,<br />

Mihai Valcu & Bart Kempenaers<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> Behavioural Ecology & Evolutionary Genetics.<br />

Max Planck Institute for Ornithology. Eberhard-Gwinner-Strasse<br />

7.82319 Seewiesen, Germany; mbulla@orn.mpg.de<br />

Breeding in <strong>the</strong> harsh conditions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> High Arctic is<br />

extremely energetically demanding. Although <strong>the</strong>re is continuous<br />

daylight during <strong>the</strong> Arctic summer, wea<strong>the</strong>r conditions<br />

and prey availability fluctuate during <strong>the</strong> day. This makes<br />

some parts <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> day more advantageous for foraging or incubation<br />

than o<strong>the</strong>rs. As a consequence, uniparental incubators<br />

concentrate <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>of</strong>f-nest (foraging) activity around <strong>the</strong> warmest<br />

part <strong>of</strong> a day (noon). Regardless <strong>of</strong> fluctuating conditions,<br />

biparentally incubating High Arctic shorebirds incubate <strong>the</strong><br />

eggs almost 100% <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> time. As a result, only one parent<br />

is <strong>of</strong>f-nest during <strong>the</strong> period when foraging conditions are<br />

most favourable. We have used Semipalmated Sandpiper<br />

Calidris pusilla as a model to investigate <strong>the</strong> outcome <strong>of</strong> this<br />

parental conflict and found great between-nest differences<br />

in <strong>the</strong> way <strong>the</strong> sexes divide incubation duties. On average,<br />

females tended to be <strong>of</strong>f-nest a) during windier conditions<br />

(usually during <strong>the</strong> day), and b) during warmer periods <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

day, that is when foraging is most efficient. This may allow<br />

females to replenish <strong>the</strong>ir reserves after egg-laying, but is to<br />

<strong>the</strong> disadvantage <strong>of</strong> males, who mostly care for <strong>the</strong> young<br />

alone. Females may compensate by having longer incubation<br />

bouts than males. This would allow males to forage for longer<br />

periods. It remains to be tested whe<strong>the</strong>r female-biased incubation<br />

is due to <strong>the</strong> female generosity or male exploitation.<br />

Multiple breeding strategies in<br />

Sanderling Calidris alba<br />

Jeroen Reneerkens, Pieter van Veelen,<br />

Marco van der Velde & Theunis Piersma<br />

Animal Ecology <strong>Group</strong>, Centre for Ecological and<br />

Evolutionary Studies, University <strong>of</strong> Groningen, Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands;<br />

J.W.H.Reneerkens@rug.nl<br />

The breeding system <strong>of</strong> Sanderling was described for <strong>the</strong><br />

first time in <strong>the</strong> early 1970’s. Females were suspected to lay<br />

two complete clutches in rapid succession, <strong>the</strong> first being<br />

incubated by <strong>the</strong> male, <strong>the</strong> second by <strong>the</strong> female. This strategy<br />

was also called “double-clutching” and should result in<br />

uniparental clutches with an incubating male or female. Later<br />

observations in different Arctic regions showed that <strong>the</strong> majority<br />

<strong>of</strong> clutches were in fact incubated by two adults sharing<br />

incubation duties. Despite <strong>the</strong>se contradicting observations,<br />

until recently <strong>the</strong> breeding strategy <strong>of</strong> Sanderling has usually<br />

been described as “double-clutching”. During six breeding<br />

seasons in NE Greenland, we observed <strong>the</strong> behaviour and<br />

movements <strong>of</strong> individually colour-marked Sanderlings,<br />

studied nest attendance with dataloggers and used microsatellite<br />

markers to genetically study parentage. The majority<br />

<strong>of</strong> clutches were incubated by both a male and a female, but<br />

uniparental nests were also observed in varying numbers in<br />

different years. A low percentage <strong>of</strong> clutches contained extrapair<br />

young and we found evidence for both polygynous males<br />

and polyandrous females. The polygamy in Sanderlings can<br />

explain why clutches <strong>of</strong> uniparental males on average hatched<br />

a few days earlier than those <strong>of</strong> uniparental females, a pattern<br />

that has previously been interpreted as indicating doubleclutching.<br />

After hatch, <strong>the</strong> male and female <strong>of</strong>ten divided <strong>the</strong><br />

chicks to be cared for separately (brood division); moreover<br />

brood mixing (chicks ending up in unrelated broods) occurred<br />

as well. In two cases, a female cared for unrelated chicks that<br />

hatched in nests which <strong>the</strong>y did not attend. We will discuss<br />

possible ecological factors that may drive <strong>the</strong> evolution <strong>of</strong><br />

uniparental care.<br />

Olfactory and visual nest defenses<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Mountain Plover<br />

Stephen J. Dinsmore & Paul D.B. Skrade<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> Natural Resource Ecology and Management,<br />

339 Science II, Iowa State University, Ames, IA 50011, USA;<br />

cootjr@iastate.edu<br />

The Mountain Plover Charadrius montanus is patchily distributed<br />

across <strong>the</strong> North American Great Plains. Their nests<br />

are located in open areas, are depredated by mammals, birds,<br />

and snakes, and adults use distraction displays to deter predators<br />

when eggs are close to hatching. We studied <strong>the</strong> roles<br />

<strong>of</strong> olfactory and visual cues on <strong>the</strong> species’ nest survival in<br />

Montana, USA from 1995 to 2010. To assess olfactory cues<br />

we analyzed <strong>the</strong> contents <strong>of</strong> 450 nests during a 5-year study<br />

(2004–2008) to correlate nest survival with aromatic nest<br />

contents that deter nest predators that use scent cues. Nest<br />

survival was positively correlated with <strong>the</strong> amount <strong>of</strong> dense<br />

clubmoss Selaginella densa and dung (primarily black-tailed<br />

prairie dog Cynomys ludovicianus and domestic cattle) in <strong>the</strong><br />

nest contents. The presence <strong>of</strong> asters Asteraceae, lichens,<br />

rocks, and o<strong>the</strong>r nest material was not correlated with nest<br />

survival. To address visual cues we photographed 374 nests<br />

during a 5-year study (2006–2010) and correlated measures<br />

<strong>of</strong> color at <strong>the</strong> nest and <strong>the</strong> color contrast between <strong>the</strong> nest<br />

and surrounding substrate with nest survival. Both <strong>the</strong> overall<br />

color contrast between <strong>the</strong> nest and surrounding substrate and<br />

<strong>the</strong> homogeneity in <strong>the</strong> three color spectra (as measured by<br />

variance) surrounding <strong>the</strong> nest were negatively correlated to<br />

nest survival. So, nests with a close color match to <strong>the</strong> nest<br />

substrate or low variability in color surrounding <strong>the</strong> nest<br />

had <strong>the</strong> greatest survival. Collectively, this suggests that <strong>the</strong><br />

Mountain Plover lines its nest with items that may hide <strong>the</strong><br />

scent <strong>of</strong> eggs from predators, places eggs in a heterogeneous<br />

substrate with respect to color, and selects nest sites where<br />

<strong>the</strong> color <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> eggs closely matches that <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> substrate.<br />

Studies such as this add an important level <strong>of</strong> understanding<br />

to patterns <strong>of</strong> nest survival in birds.

IWSG <strong>Annual</strong> <strong>Conference</strong><br />

217<br />

Nest success and habitat requirements <strong>of</strong><br />

saltmarsh-breeding birds<br />

Elwyn Sharps<br />

School <strong>of</strong> Ocean Sciences, Bangor University. Working with <strong>the</strong><br />

Centre for Ecology and Hydrology, <strong>the</strong> Royal Society for <strong>the</strong><br />

Protection <strong>of</strong> Birds and Wildlife Conservation Wales<br />

Address for correspondence: Centre for Ecology and Hydrology,<br />

Floor 1, Environment Centre Wales, Deiniol Road, Bangor,<br />

Gwynedd, LL57 2UW, United Kingdom; e.sharps@bangor.ac.uk<br />

Populations <strong>of</strong> Redshank Tringa totanus breeding on UK<br />

saltmarshes are declining, yet <strong>the</strong> exact mechanisms behind<br />

<strong>the</strong> declines are unknown. This study addressed nest survival<br />

and habitat selection in a number <strong>of</strong> saltmarsh-breeding birds<br />

focussing primarily on Redshank, but also including Eurasian<br />

Oystercatcher Haematopus ostralegus, Nor<strong>the</strong>rn Lapwing<br />

Vanellus vanellus, Meadow Pipit Anthus pratensis, Skylark<br />

Alauda arvensis and Linnet Carduelis cannabina. We asked:<br />

1) What are <strong>the</strong> drivers <strong>of</strong> nest failure in saltmarsh breeding<br />

birds, and does this vary according to grazing intensity?<br />

(2) Are <strong>the</strong> main predators birds or mammals, and is this<br />

related to grazing intensity? (3) Does nest habitat selection<br />

vary within different grazing treatments?<br />

The number <strong>of</strong> eggs and <strong>the</strong>ir length, breadth and weight<br />

were recorded to estimate a hatch date. Nests were revisited<br />

regularly until <strong>the</strong> eggs had ei<strong>the</strong>r hatched or failed. iButton<br />

<strong>the</strong>rmo-loggers were be placed in each wader nest. Following<br />

a predation event, logger-data were used to look for changes<br />

in temperature to determine if predation events were nocturnal<br />

(mammals) or diurnal (birds). Vegetation height and %<br />

cover was measured both in a 1 m × 1 m area around each<br />

nest and within five 1-m quadrats within a 10 m × 10m area<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> nest site. A total <strong>of</strong> 45 Redshank nests were monitored<br />

as well as 25 nests <strong>of</strong> Meadow Pipit, 11 <strong>of</strong> Nor<strong>the</strong>rn Lapwing,<br />

10 <strong>of</strong> Eurasian Oystercatcher, 8 <strong>of</strong> Skylark and 3 <strong>of</strong> Linnet.<br />

Tidal flooding was <strong>the</strong> biggest overall cause for nest failure,<br />

followed by predation and trampling by livestock. Nine <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> 45 Redshank nests hatched successfully. Results will be<br />

presented in more detail and discussed in <strong>the</strong> context <strong>of</strong> grazing<br />

management and conservation implications.<br />

Staging ecology and migration<br />

Connectivity <strong>of</strong> stop-over sites: <strong>the</strong> stepping<br />

stones <strong>of</strong> range-wide carry-over effects<br />

José A. Alves 1 , Tomas G. Gunnarsson 2 ,<br />

Daniel B. Hayhow 1,6 , Graham, F. Appleton 3 ,<br />

Peter M. Potts 4 , William J. Su<strong>the</strong>rland 5 &<br />

Jennifer A. Gill 1<br />

1<br />

School <strong>of</strong> Biological Sciences, University <strong>of</strong> East Anglia, Norwich<br />

Research Park, Norwich, NR4 7TJ, UK; j.alves@uea.ac.uk<br />

2<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Iceland, South Iceland Research Centre,<br />

Tryggvagata 36, IS-800 Selfoss, Iceland;<br />

Gunnarsholt, IS-851 Hella, Iceland<br />

3<br />

British Trust for Ornithology, The Nunnery,<br />

Thetford, IP24 2PU, UK<br />

4<br />

Farlington Ringing <strong>Group</strong>, Solent Court Cottage,<br />

Chilling Lane, Warsash, Southampton SO31 9HF, UK<br />

5<br />

Conservation Science <strong>Group</strong>, Department <strong>of</strong> Zoology, University<br />

<strong>of</strong> Cambridge, Downing St., Cambridge, CB2 3EJ, UK<br />

6<br />

Present address: RSPB, The Lodge, Sandy,<br />

Bedfordshire, SG19 2DL, UK<br />

Many migratory species use stopover sites on spring and<br />

autumn journeys to and from <strong>the</strong> breeding grounds, and different<br />

migratory routes involve different stopover locations.<br />

Links between conditions on breeding and winter sites <strong>of</strong><br />

migratory species can be strong drivers <strong>of</strong> individual fitness<br />

but <strong>the</strong> influence <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> migratory routes used by individuals<br />

on <strong>the</strong>se links is unknown. In Icelandic Black-tailed Godwits,<br />

individuals tend to occupy ei<strong>the</strong>r good or poor breeding and<br />

wintering sites, resulting in substantial fitness differences between<br />

individuals. Large differences in <strong>the</strong> energetic costs and<br />

benefits <strong>of</strong> wintering at different locations have been linked<br />

to <strong>the</strong> timing <strong>of</strong> arrival <strong>of</strong> individuals in Iceland, and early<br />

arriving birds tend to occupy better quality breeding areas.<br />

However, <strong>the</strong> majority <strong>of</strong> individuals also use stopover sites<br />

on spring migration, and <strong>the</strong>se sites may also be contributing<br />

to <strong>the</strong> seasonal links in connectivity and individual fitness. By<br />

population-wide tracking <strong>of</strong> marked individuals throughout<br />

<strong>the</strong> annual migration, we show that <strong>the</strong> two major spring<br />

stopover areas: <strong>the</strong> Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands and E England are used in<br />

different proportions by birds from different winter regions.<br />

Additionally, irrespective <strong>of</strong> winter location, individuals<br />

using <strong>the</strong> Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands stopover arrive significantly earlier<br />

in Iceland and are more likely to breed in traditionally occupied<br />

breeding grounds, where good quality breeding habitat<br />

is more abundant. As <strong>the</strong> majority <strong>of</strong> individuals using <strong>the</strong><br />

Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands come from wintering locations in <strong>the</strong> south <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> range, <strong>the</strong> conditions on <strong>the</strong>se stopover sites are likely to<br />

facilitate a longer migration and an early migratory schedule.<br />

A strategic stopover for Red Knot<br />

and o<strong>the</strong>r shorebirds:<br />

Mingan Archipelago, Quebec, Canada<br />

Yves Aubry 1 , Allan Baker 2 , Christophe Buidin 3 ,<br />

Yann Rochepault 3 & Patricia Gonzalez 4<br />

1<br />

Canadian Wildlife Service-Quebec Region, Environment Canada,<br />

801-1550 avenue D’Estimauville, Quebec, Qc, G1J 0C3,<br />

Canada; yves.aubry@ec.gc.ca<br />

2<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> Natural History, Royal Ontario Museum,<br />

100 Queen’s Park, Toronto, ON. M5S 2C6, Canada<br />

3<br />

1, Chemin du Ruisseau, Rivière St-Jean,<br />

Québec, QC, G0G 2N0, Canada<br />

4<br />

Fundacion Inalafquen, Roca 135, 8520 San Antonio Oeste,<br />

Rio Negro, Argentina<br />

The Mingan Archipelago is likely <strong>the</strong> first important stopover<br />

for Red Knots and many o<strong>the</strong>r species <strong>of</strong> shorebirds as <strong>the</strong>y<br />

exit <strong>the</strong>ir Canadian Arctic breeding grounds on <strong>the</strong>ir journey<br />

to eastern South America. These unique and scenic islands<br />

are located on <strong>the</strong> north side <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Gulf <strong>of</strong> St Lawrence<br />

and <strong>the</strong>ir limestone flats are rich in marine invertebrates.<br />

<strong>Annual</strong> monitoring <strong>of</strong> shorebirds which started in 2006 has<br />

revealed <strong>the</strong> importance <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Mingan Archipelago during<br />

autumn migration (Jul–Nov) as a site for <strong>the</strong> refuelling <strong>of</strong><br />

Red Knots. Regular counts and resightings <strong>of</strong> flagged birds<br />

have been used as indices <strong>of</strong> breeding success. We estimate<br />

that over 5,000 adult Red Knots stop to refuel in <strong>the</strong> Mingan<br />

Archipelago each autumn.

218 <strong>Wader</strong> <strong>Study</strong> <strong>Group</strong> Bulletin 119(3) 2012<br />

Development <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> project The Ruff<br />

Philomachus pugnax studies in CIS countries<br />

Natalia Karlionova 1 , Pavel Pinchuk 1 , Ivan Bogdanovich 1 ,<br />

Julia Karagicheva 2 Maksim Korolkov 3 ,<br />

Alexander Matsyna 4 , Ekaterina Matsyna 4 ,<br />

Pavel Panchenko 5 , Oleg Formanuk 5 ,<br />

Josef Chernichko 6 & Eldar Rakhimberdiev 2,7,8<br />

1<br />

Institute <strong>of</strong> Zoology NAS Belarus,<br />

Minsk, Belarus; Karlionova@tut.by<br />

2<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> Ecology and Evolutionary<br />

Biology, Cornell University, Ithaca, USA<br />

3<br />

Regional Youth Ecological Centre, Ulyanovsk, Russia<br />

4<br />

Ecological Centre ”Dront”, Nizhny Novgorod, Russia<br />

5<br />

Odessa, Ukraine<br />

6<br />

Azov-Black Sea Ornithological Station, Melitopol, Ukraine<br />

7<br />

Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands Institute for Sea Research<br />

(NIOZ), Den Burg, Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands<br />

8<br />

Lomonosov Moscow State University, Moscow, Russia<br />

In 2012, we continued <strong>the</strong> Ruff colour-ringing project, initiated<br />

in Russia and E Europe in 2010. With this project we aim<br />

to obtain information on migration routes and major stopover<br />

sites <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Ruff in this area (Russia, Belarus, Ukraine, Hungary).<br />

From 2011, we developed and registered at EURING<br />

a new colour-ringing scheme for Ruff captured in different<br />

locations in Russia, Belarus, Hungary and Ukraine. This<br />

scheme allows <strong>the</strong> identification <strong>of</strong> individual birds by a<br />

unique code inscribed on <strong>the</strong> flag. In case <strong>the</strong> code cannot be<br />

read, <strong>the</strong> pattern <strong>of</strong> colour-rings and <strong>the</strong> colour <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> flag indicate<br />

<strong>the</strong> location, year and season that <strong>the</strong> bird was marked.<br />

In 2011, we ringed migrating Ruffs at 5 stopover sites (3 in<br />

Russia, 1 in Belarus and 1 in Hungary). In total, 638 birds<br />

f<br />

were colour-marked during <strong>the</strong> spring and autumn migration<br />

seasons <strong>of</strong> 2011. In spring 2012, we ringed migrating Ruffs<br />

at 2 places in Russia (3 marked birds), 2 places in Ukraine<br />

(172 marked birds) and 1 place in Belarus (600 marked birds).<br />

The increase in <strong>the</strong> number <strong>of</strong> colour-marked Ruffs and<br />

observers has led to an increase in <strong>the</strong> number <strong>of</strong> resightings<br />

and recoveries. In 2012, we had <strong>the</strong> first resightings <strong>of</strong> colourringed<br />

Ruffs from <strong>the</strong> previous year. Three Ruffs marked in<br />

spring 2011 at <strong>the</strong> Turov Station (Belarus) were seen in <strong>the</strong><br />

same place <strong>the</strong> next year. At <strong>the</strong> beginning <strong>of</strong> June 2012, 3<br />

Ruffs ringed in <strong>the</strong> Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands were seen on Kolguev Island<br />

(Barents Sea). Also 8 birds ringed in Belarus in spring 2012<br />

have been seen in o<strong>the</strong>r countries (4 Ukraine, 2 Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands,<br />

1 Estonia and 1 Sweden).<br />

We have launched a website called “The Ruff Project”<br />

(www. philomachus.ru) with 103 users now registered. We<br />

have published more than 60 articles, telling about our Ruff<br />

ringing project, as well as o<strong>the</strong>r projects related to wader<br />

studies, expeditions, scientific papers, conferences and o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

events in ornithology. In <strong>the</strong> web forum (322 posts) our visitors<br />

discuss news and events in <strong>the</strong> ornithological world. A<br />

separate branch <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> forum is devoted to modern techniques<br />

<strong>of</strong> statistical analysis.<br />

As we are interested in discovering <strong>the</strong> main staging<br />

areas used by Ruff, we have studied information published<br />

on wader counts in post-Soviet countries over <strong>the</strong> last 20<br />

years and have discovered that <strong>the</strong>re are no reliable data.<br />

We <strong>the</strong>refore decided to create our own database that can be<br />

potentially synchronized with any <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> main international<br />

information repositories. Currently our database holds details<br />

<strong>of</strong> 207 counts <strong>of</strong> 225 species. Distributions are presented<br />

using Google maps.<br />

Workshop:<br />

East Asian–Australasian Flyway in crisis<br />

e<br />

High densities <strong>of</strong> small prey explain fast fuelling<br />

in a long-distance migrating molluscivore,<br />

Red Knots, in <strong>the</strong> Yellow Sea:<br />

<strong>the</strong> classical diet model as a special case<br />

Hong-Yan Yang 1, 2 * , Bing Chen 3 , Jan van Gils 4 ,<br />

Zheng-Wang Zhang 1 & Theunis Piersma 2, 4<br />

1<br />

Key Laboratory for Biodiversity Science and Ecological<br />

Engineering, Beijing Normal University, Beijing 100875, China<br />

2<br />

Animal Ecology <strong>Group</strong>, Centre for Ecological and Evolutionary<br />

Studies, University <strong>of</strong> Groningen, PO Box 14,<br />

9750 AA Haren, The Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands<br />

3<br />

Room 2511, Building 1, 2 Nan-Fang-Zhuang,<br />

Fengtai District, Beijing 100079, China<br />

4<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> Marine Ecology and Evolution,<br />

Royal Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands Institute for Sea Research (NIOZ),<br />

PO Box 59, 1790 AB Den Burg, Texel, The Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands<br />

* boganick@mail.bnu.edu.cn<br />

Nor<strong>the</strong>rn Bohai Bay, <strong>the</strong> Yellow Sea, is a crucial staging area<br />

for two subspecies <strong>of</strong> Red Knots (Calidris canutus rogersi<br />

and C. c. piersmai) during northward migration. As famous<br />

molluscivores which ingest <strong>the</strong>ir prey whole, Red Knots can<br />

only harvest 4.5<br />

kJ/g DMshell) according to <strong>the</strong> “digestive constraint model”,<br />

<strong>the</strong> measured shell processing rate <strong>of</strong> 3.93 mg/s, based on field<br />

observations <strong>of</strong> dropping rates and digestion experiments, is<br />

much higher than predicted for Red Knots eating as fast as<br />

<strong>the</strong>y can with <strong>the</strong> measured gizzard size (2.58 mg/s). It suggests<br />

that Potamocorbula has characteristics that make <strong>the</strong>m<br />

easy to ingest or digest, e.g. <strong>the</strong> shells may be more crushable<br />

than prey studied elsewhere. The distinctive characteristics<br />

<strong>of</strong> Potamocorbula as prey (small size, low quality, high<br />

density and high processing rate) mean that <strong>the</strong> net energy<br />

intake rate <strong>of</strong> Red Knots in Bohai Bay (5.13 J/s) is as high as<br />

that <strong>of</strong> Red Knots feeding on apparently better quality food<br />

elsewhere. Fur<strong>the</strong>r work is needed to explore <strong>the</strong> changing<br />

food resource and <strong>the</strong> carrying capacity <strong>of</strong> Red Knots at this<br />

important stopover.

IWSG <strong>Annual</strong> <strong>Conference</strong><br />

219<br />

Extreme migration and <strong>the</strong> annual cycle:<br />

individual strategies in New Zealand<br />

Bar-tailed Godwits<br />

Jesse R. Conklin & Phil F. Battley<br />

Ecology <strong>Group</strong>, Massey University, Palmerston North,<br />

New Zealand; conklin.jesse@gmail.com<br />

Alaska-breeding Bar-tailed Godwits Limosa lapponica<br />

baueri perform <strong>the</strong> two longest non-stop migratory flights<br />

<strong>of</strong> any bird, including a direct trans-Pacific flight <strong>of</strong> 11,000–<br />

12,000 km to New Zealand. Amid <strong>the</strong>ir challenging annual<br />

routines, godwits maintain highly individualised moult and<br />

migration schedules and are strongly sexually dimorphic. At<br />

a single non-breeding site in New Zealand, we used detailed<br />

direct observations <strong>of</strong> colour-marked individuals, coupled<br />

with year-round geolocator tracking, to examine <strong>the</strong> roots<br />

and consequences <strong>of</strong> persistent and ephemeral individual<br />

differences, and to identify potential constraints and bottlenecks<br />

in <strong>the</strong> annual cycle. Inter-individual variation in size,<br />

plumage, and migration timing were linked to <strong>the</strong> location<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> godwits’ breeding sites in Alaska. Despite remarkable<br />

annual consistency in moult and migration schedules,<br />

godwits showed surprising flexibility to respond to shortterm<br />

wea<strong>the</strong>r patterns, annual variation in breeding success,<br />

and substantial delays in southbound migration. Overall,<br />

this research confirms that an individual-based, entire-year<br />

perspective is required to understand population patterns in<br />

any particular season, and challenges <strong>the</strong> view that extreme<br />

long-distance migrants are operating at <strong>the</strong> limits <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

capabilities.<br />

Using demographic estimates to keep track <strong>of</strong><br />

population dynamics and viability<br />

Jutta Leyrer & Marcel Klaassen<br />

Centre for Integrative Ecology, Deakin University, Waurn Ponds<br />

Campus, Geelong Victoria 3220, Australia;<br />

jutta.leyrer@deakin.edu.au<br />

In recent years, shorebird populations all around <strong>the</strong> globe<br />

have shown rapid declines. The most prominent declines are<br />

observed within <strong>the</strong> East Asian–Australasian Flyway. This<br />

has raised much concern among scientists and conservationists<br />

alike, and demands immediate conservation actions<br />

for <strong>the</strong> protection <strong>of</strong> shorebird species and <strong>the</strong>ir migratory<br />

flyways. The development <strong>of</strong> conservation strategies greatly<br />

benefits from knowledge about demographic parameters as<br />

it is extremely important to be able to distinguish whe<strong>the</strong>r<br />

changes in survival or recruitment are <strong>the</strong> main drivers <strong>of</strong><br />

population declines. Mark–recapture (or resighting) studies<br />

are <strong>of</strong>ten conducted to determine <strong>the</strong>se essential parameters.<br />

Freely available s<strong>of</strong>tware such as MARK or ESURGE<br />

facilitates analyses <strong>of</strong> adult survival, and survival <strong>of</strong> juveniles/<br />

immatures (recruitment). Yet, such mark–recapture models<br />

are extremely data hungry. Hence, we analysed simulated<br />

capture–recapture histories using MARK to detect optimal<br />

sampling duration and capture effort with different underlying<br />

demographical parameters. Confirming previous studies we<br />

could show that study designs should allow for high capture<br />

and recapture rates to obtain reliable estimates, even if differences<br />

between groups (e.g. populations) are high. Setting<br />

up an individually marked population allows <strong>the</strong> calculation<br />

<strong>of</strong> fur<strong>the</strong>r important parameters such as site-fidelity to nonbreeding,<br />

staging or breeding areas, and stopover duration<br />

and provides an additional tool for monitor population sizes.<br />

Spoon-billed Sandpiper: current population<br />

estimates and conservation activities by <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>International</strong> Task Force<br />

Evgeny Syroechkovskiy – BirdsRussia &<br />

<strong>the</strong> Spoon-billed Sandpiper Task Force <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> East<br />

Asian–Australasian Flyway Partnership<br />

All-Russian Research Institute for Nature Conservation,<br />

Moscow, Russia; ees_jr@yahoo.co.uk<br />

The critically endangered Spoon-billed Sandpiper has<br />

declined over 90% in about 30 years and is now one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

most threatened waders in <strong>the</strong> world as well as <strong>the</strong> flagship<br />

species for conservation on <strong>the</strong> East Asian – Australasian<br />

Flyway. The project focusing on <strong>the</strong> conservation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> species<br />

was started in <strong>the</strong> year 2000 in Russia and now after 12<br />

years <strong>of</strong> continuous work has become an international effort<br />

coordinated by an <strong>International</strong> Task Force (ITF) under <strong>the</strong><br />

East Asian – Australasian Flyway Partnership with BirdLife<br />

<strong>International</strong> as leading partner and BirdsRussia as key<br />

implementing organization. The main priority directions <strong>of</strong><br />

work are: (1) hunting in <strong>the</strong> SE Asian wintering grounds,<br />

(2) reclamation <strong>of</strong> inter-tidal areas in <strong>the</strong> staging grounds and<br />

(3) <strong>the</strong> very low breeding productivity in Chukotka. The ITF<br />

has successfully initiated conservation work in both breeding<br />

and wintering areas in Russia and SE Asia but at <strong>the</strong> moment<br />

faces serious challenges at <strong>the</strong> staging sites, particularly in<br />

China. Recent population estimates are based on evaluations<br />

in <strong>the</strong> intensively studied breeding grounds. Of <strong>the</strong> 42 main<br />

known breeding locations, 28 have been revisited in <strong>the</strong> past<br />

twelve years: 18 breeding populations were extinct and ten<br />

populations showed extreme declines in numbers – no stable<br />

or increasing populations were discovered. In 2012, <strong>the</strong><br />

breeding population was estimated to be hardly more than one<br />

hundred pairs. In <strong>the</strong> past five years one key breeding population<br />

has gone extinct, and ano<strong>the</strong>r is considered near extinct.<br />

Only one breeding population seems to be stable, although at<br />

very low levels with only about 30–40 breeding pairs.<br />

Spoon-billed Sandpiper in Bangladesh<br />

Sayam U. Chowdhury<br />

Bangladesh Spoon-billed Sandpiper Conservation Project &<br />

Focal Point <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Spoon-billed Sandpiper Task Force in<br />

Bangladesh; sayam_uc@yahoo.com<br />

The Spoon-billed Sandpiper Eurynorhynchus pygmeus is a<br />

migrant shorebird that breeds in <strong>the</strong> Russian Arctic and winters<br />

primarily in Bangladesh and Myanmar. To determine <strong>the</strong><br />

current status <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Spoon-billed Sandpiper in Bangladesh,<br />

all locations at which <strong>the</strong> species had previously been recorded<br />

were surveyed over three consecutive winters. GIS analysis<br />

was carried out using Google Earth to identify potential sites.<br />

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with local people<br />

to determine <strong>the</strong> degree <strong>of</strong> hunting pressure on Spoon-billed<br />

Sandpipers. After thorough surveys, we identified Sonadia<br />

Island and Domar Char as <strong>the</strong> most important intertidal<br />

mudflats for Spoon-billed Sandpipers in Bangladesh. The<br />

findings <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se studies add to our knowledge <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> current<br />

distribution, wintering population and ecology <strong>of</strong> this<br />

highly threatened wader. The sites identified are subject to<br />

extreme pressure from human activities, especially shorebird<br />

hunting. A total <strong>of</strong> 25 active bird-trappers were identified at<br />

Sonadia Island and eight <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>m claimed to have captured<br />

an aggregate <strong>of</strong> 22 Spoon-billed Sandpipers in <strong>the</strong><br />

last two winter seasons. All 25 hunters have now

220 <strong>Wader</strong> <strong>Study</strong> <strong>Group</strong> Bulletin 119(3) 2012<br />

signed agreements that in return for alternative livelihood<br />

support <strong>the</strong>y will stop shorebird hunting and protect <strong>the</strong>m<br />

instead. Village Conservation <strong>Group</strong>s (VCG) will be in charge<br />

<strong>of</strong> monitoring and hunters will repay a small percentage <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

income generated by <strong>the</strong> alternative livelihood to <strong>the</strong>ir VCG<br />

over <strong>the</strong> next 24 months. The VCGs will <strong>the</strong>n use this money<br />

for fur<strong>the</strong>r hunting mitigation.<br />

What role does captive breeding and<br />

“headstarting” have in <strong>the</strong> recovery <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Spoon-billed Sandpiper?<br />

Nigel Clark 1 , Rhys Green 2 & Baz Hughes 3 on behalf <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> Spoon-billed Sandpiper Task Force<br />

1<br />

British Trust for Ornithology, The Nunnery, Thetford, Norfolk<br />

IP22 1HT, UK; nigel.clark@bto.org<br />

2<br />

Conservation Science <strong>Group</strong>, Department <strong>of</strong> Zoology,<br />

Downing Street, Cambridge CB2 3EJ, UK<br />

3<br />

Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust (WWT), Slimbridge,<br />

Glos GL2 7BT, UK<br />

The Spoon-billed Sandpiper is now critically endangered and<br />

is predicted to become extinct within <strong>the</strong> next decade without<br />

conservation action. Since 2000, it has been declining at 25%<br />

per annum probably due to a number <strong>of</strong> factors. The two most<br />

important are likely to be subsistence hunting and habitat loss<br />

through land claim.<br />

Considerable progress has been made on <strong>the</strong> reduction <strong>of</strong><br />

hunting, but it will be a number <strong>of</strong> years until it will be possible<br />

to tell if this is sufficient to halt or reverse <strong>the</strong> decline. If<br />

<strong>the</strong> population continues to decline over <strong>the</strong> next few years it<br />

will become increasingly difficult to set up a viable breeding<br />

population in captivity, so <strong>the</strong> decision was taken in 2011 to<br />

collect 40 eggs over two years and set up a founder population<br />

at Slimbridge, UK. The 20 eggs taken in 2011 were<br />

raised on <strong>the</strong> breeding grounds and near <strong>the</strong> regional capital<br />

Anadyr and <strong>the</strong> success <strong>of</strong> this project lead to <strong>the</strong> development<br />

<strong>of</strong> ‘headstarting’; a plan to take eggs and raise chicks<br />

in a predator-free environment before releasing fledglings<br />

on <strong>the</strong> tundra at about 20 days old. In 2012, a fur<strong>the</strong>r 20<br />

eggs were collected for captive breeding and as a result <strong>of</strong><br />

favourable wea<strong>the</strong>r conditions were transported to Slimbridge<br />

before <strong>the</strong>y hatched. The development <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se plans and <strong>the</strong><br />

modelling <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> likely impact on <strong>the</strong> wild population will<br />

be discussed.<br />

Urgency <strong>of</strong> flyway conservation: overview <strong>of</strong><br />

rates <strong>of</strong> habitat loss and<br />

<strong>the</strong> status <strong>of</strong> shorebird populations<br />

in <strong>the</strong> East Asian–Australasian Flyway<br />

Yvonne I. Verkuil<br />

Marine Evolution and Conservation, Centre for Ecological and<br />

Evolutionary Studies, University <strong>of</strong> Groningen, The Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands;<br />

yvonne_verkuil@hotmail.com<br />

A situation analysis commissioned by IUCN, and executed in<br />

collaboration with Queensland University in Australia, shows<br />

that intertidal habitats along <strong>the</strong> East Asian–Australasian<br />

Flyway (EAAF) face an unprecedented ecological crisis.<br />

Intertidal migratory waterbirds along <strong>the</strong> EAAF show fast<br />

declines: at least 24 species are threatened with extinction,<br />

many more than in o<strong>the</strong>r flyways. Shorebirds in <strong>the</strong> EAAF<br />

are <strong>the</strong> world’s most threatened migratory birds, and many<br />

face exceptionally rapid losses <strong>of</strong> 5–9% per year. With<br />

a 26% annual decline, <strong>the</strong> Spoon-billed Sandpiper<br />

could be extinct soon. Of <strong>the</strong> 16 identified EAAF key areas,<br />

six are in <strong>the</strong> Yellow Sea. Here <strong>the</strong> most pressing threat is <strong>the</strong><br />

fast pace <strong>of</strong> land reclamation: since 2000 at least 35% <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

tidal flat area has been reclaimed. Overall, some countries<br />

have lost >50% <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir coastal wetlands to land reclamation<br />

since 1980. These rates <strong>of</strong> habitat loss are comparable to<br />

those <strong>of</strong> tropical rainforests and mangroves. Losses <strong>of</strong> such<br />

magnitude are likely <strong>the</strong> key drivers <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> waterbird declines<br />

and related environmental problems. Breeding success in <strong>the</strong><br />

Arctic and survival in <strong>the</strong> Australasian sites, where <strong>the</strong> birds<br />

spend <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn winter, appear to be adequate; <strong>the</strong> main<br />

problems seem to be in <strong>the</strong> East Asian staging areas. The declines<br />

<strong>of</strong> waterbirds are signals <strong>of</strong> wider deteriorations <strong>of</strong> tidal<br />

ecosystems. The effects <strong>of</strong> reclamation act cumulatively with<br />

pollution, invasion <strong>of</strong> non-native species, silt-flow reduction<br />

resulting from damming <strong>of</strong> rivers, over-fishing, hunting <strong>of</strong><br />

waterbirds, and conversion <strong>of</strong> mudflats for agri-aquaculture.<br />

There has been a significant increase in floods, salination,<br />

outbreaks <strong>of</strong> algal blooms, and death <strong>of</strong> fish and aquaculture<br />

stocks, exposing densely populated areas to devastating damage.<br />

Alternatively, healthy tidal flats would provide many<br />

services <strong>of</strong> direct economic benefit to local communities and<br />

beyond (e.g. fisheries worth billions <strong>of</strong> US$ per year). Currently<br />

coastal zone planning does not adequately acclaim <strong>the</strong><br />

existing and future values <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> intertidal wetlands.<br />

IUCN report: MacKinnon, J., Verkuil, Y.I. & Murray,<br />

N. (compilers) (2012) IUCN situation analysis on East and<br />

Sou<strong>the</strong>ast Asian intertidal habitats, with particular reference<br />

to <strong>the</strong> Yellow Sea (including <strong>the</strong> Bohai Sea). Occasional Paper<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> IUCN Species Survival Commission No. 47. Gland,<br />

Switzerland and Cambridge, UK: IUCN. 72 pp. www.iucn.<br />

org/Asiancoastalwetlands<br />

Successes and challenges in<br />

Spoon-billed Sandpiper conservation in <strong>the</strong><br />

EAAFP flyway context<br />

C. Zöckler 1 , E. Syroechkovskiy 2 & N.A. Clark 3<br />

1<br />

ArcCona Consulting, 30 Eachard Road, CB3 0HY Cambridge, UK;<br />

Christoph.Zockler@consultants.unep-wcmc.org<br />

2<br />

All-Russian Research Institute for<br />

Nature Conservation, Moscow, Russia<br />

3<br />

British Trust for Ornithology, Thetford, Norfolk, UK<br />

The Spoon-billed Sandpiper is one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> few critically endangered<br />

waders with a rapidly declining population, estimated<br />

to be below 100 pairs. The species breeds along a narrow<br />

strip <strong>of</strong> coastal wetlands in Chukotka and N Kamchatka in<br />

<strong>the</strong> Russian Arctic and migrates along <strong>the</strong> East Asian Flyway<br />

passing through 14 countries, wintering in Myanmar,<br />

Thailand, China, Vietnam and Bangladesh. Hunting and<br />

trapping has been identified as a major threat but mitigation<br />

measures over <strong>the</strong> past two years have been very successful<br />

in <strong>the</strong> most important wintering sites in Myanmar and<br />

Bangladesh. Whilst work is continuing to foster initiatives<br />

with local communities, threats along <strong>the</strong> flyway, especially<br />

at very important stopover and moulting sites in China and<br />

Korea are more challenging. In fact <strong>the</strong> rate <strong>of</strong> habitat loss<br />

and coastal development is accelerating and <strong>the</strong> entire global<br />

conservation community is powerlessly watching <strong>the</strong> decline.<br />

There are though hopes in emerging young bird-watching<br />

groups formulating new approaches in conservation. It is now<br />

<strong>the</strong> time to find partners, supporters and donors to step up<br />

<strong>the</strong> next level <strong>of</strong> coordination. As we cannot be sure that our<br />

conservation work will be successful, we have ventured into<br />

an ambitious captive breeding programme as a ‘back up’. This<br />

is now in its second year and has so far been very successful.

IWSG <strong>Annual</strong> <strong>Conference</strong><br />

221<br />

Population trends in shorebirds <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

East Asian–Australasian Flyway from a<br />

Siberian perspective<br />

Pavel S. Tomkovich<br />

Zoological Museum, Moscow State University, Moscow, Russia<br />

Typically, shorebirds are spread over vast areas on <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

Arctic breeding grounds which, with few exceptions, means<br />

that monitoring <strong>the</strong>ir populations is virtually impossible or<br />

at least very difficult. In Russia, <strong>the</strong>re are only two longterm<br />

studies: since <strong>the</strong> mid-1990s <strong>the</strong> densities <strong>of</strong> breeding<br />

shorebirds have been monitored on SE Taimyr, and since <strong>the</strong><br />

early 2000s a special monitoring project for <strong>the</strong> Spoon-billed<br />

Sandpiper has been conducted in Chukotka. Therefore, we<br />

cannot supply data about <strong>the</strong> population trends <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> great<br />

majority <strong>of</strong> species across <strong>the</strong>ir extensive breeding ranges.<br />

There is also a large faunistic literature with data on species<br />

distribution and abundance, collected mostly during <strong>the</strong> 20th<br />

century, which represents ano<strong>the</strong>r source <strong>of</strong> information about<br />

f<br />

The Coast, Shorebird and Benthic Macr<strong>of</strong>auna Survey <strong>Group</strong>,<br />

led by Réserves Naturelles de France in partnership with <strong>the</strong><br />

Agence des Aires Marines Protégées is an ongoing coastal<br />

surveillance effort. Since 2000, at <strong>the</strong> initiative <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> managers<br />