Double-Edged Hydropolitics on the Nile - Center for Security Studies ...

Double-Edged Hydropolitics on the Nile - Center for Security Studies ...

Double-Edged Hydropolitics on the Nile - Center for Security Studies ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

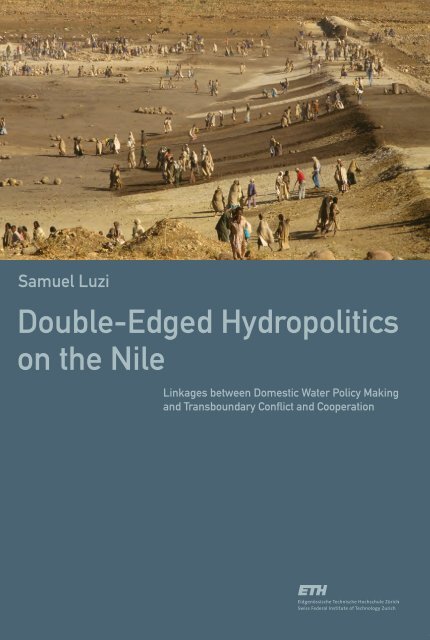

Samuel Luzi<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Double</str<strong>on</strong>g>-<str<strong>on</strong>g>Edged</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Hydropolitics</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Nile</strong><br />

Linkages between Domestic Water Policy Making<br />

and Transboundary C<strong>on</strong>flict and Cooperati<strong>on</strong>

DISS. ETH NO. 17432<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Double</str<strong>on</strong>g>-<str<strong>on</strong>g>Edged</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Hydropolitics</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Nile</strong><br />

Linkages Between Domestic Water Policy Making<br />

and Transboundary C<strong>on</strong>flict and Cooperati<strong>on</strong><br />

A dissertati<strong>on</strong> submitted to <strong>the</strong><br />

Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich<br />

<strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> degree of<br />

Doctor of Science<br />

presented by<br />

Samuel Luzi<br />

Dipl. Umwelt-Natw. ETH<br />

born December 29 th , 1975<br />

citizen of Furna und Jenaz<br />

accepted <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> recommendati<strong>on</strong> of<br />

Prof. Dr. Alexander J.B. Zehnder<br />

Prof. Dr. Andreas Wenger<br />

2007

Acknowledgment<br />

T<br />

his study was c<strong>on</strong>ducted in <strong>the</strong> framework of <strong>the</strong> Work Package 1<br />

(Governance and C<strong>on</strong>flict) of <strong>the</strong> NCCR North South Program. The<br />

Nati<strong>on</strong>al Competence <strong>Center</strong> in Research (NCCR) North South is jointly<br />

funded by <strong>the</strong> Swiss Nati<strong>on</strong>al Science Foundati<strong>on</strong> (SNF) and <strong>the</strong> Swiss<br />

Agency <strong>for</strong> Development and Cooperati<strong>on</strong> (SDC).<br />

I am deeply indebted to numerous individuals <strong>for</strong> supporting me during<br />

<strong>the</strong> work <strong>on</strong> this <strong>the</strong>sis. I particularly thank my supervisors, Prof. Alexander<br />

J.B. Zehnder and Prof. Andreas Wenger, <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir c<strong>on</strong>tinuous and reliable<br />

support. Prof. Zehnder provided valuable c<strong>on</strong>tributi<strong>on</strong>s both through his<br />

c<strong>on</strong>structive inputs to my scientific writing and through his support and<br />

extensive knowledge in <strong>the</strong> areas of water policy and water management<br />

instituti<strong>on</strong>s. I am especially grateful <strong>for</strong> his additi<strong>on</strong>al support to <strong>the</strong> associated<br />

M.A. / M.Sc. projects. Prof. Wenger’s input greatly helped to improve<br />

<strong>the</strong> c<strong>on</strong>ceptual frameworks and to structure <strong>the</strong> draft articles c<strong>on</strong>stituting<br />

this <strong>the</strong>sis. I also thank Prof. Wenger <strong>for</strong> four years of access to <strong>the</strong> infrastructure<br />

of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Center</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Security</strong> <strong>Studies</strong> (CSS) at <strong>the</strong> Swiss Federal<br />

Institute of Technology.<br />

I am most grateful to Dr. Sim<strong>on</strong> Mas<strong>on</strong>, who has accompanied this<br />

<strong>the</strong>sis from <strong>the</strong> beginning with his c<strong>on</strong>tinuous and encouraging support.<br />

He introduced me to <strong>the</strong> complex challenges of <strong>Nile</strong> Basin cooperati<strong>on</strong>,<br />

dependably provided feedback and guidance in practical and scientific matters,<br />

and was a very pleasant office mate. I also greatly benefited from <strong>the</strong><br />

c<strong>on</strong>tacts he had established in Egypt and Ethiopia during his own studies<br />

<strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Nile</strong>.<br />

The ‘family’ of <strong>the</strong> NCCR North-South Program provided a stimulating<br />

working envir<strong>on</strong>ment <strong>for</strong> this study. I greatly enjoyed <strong>the</strong> opportunities<br />

to share experiences with colleagues from all over <strong>the</strong> world and expand<br />

research partnerships into pers<strong>on</strong>al friendship. The collaborati<strong>on</strong> with colleagues<br />

at IP7 and <strong>the</strong> JACS Horn of Africa, namely Alemmaya Mulugeta,<br />

Amare Bantider, Atta El Battahani, Birru Yitaferu, Christine Bichsel, Irina<br />

3

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Double</str<strong>on</strong>g>-<str<strong>on</strong>g>Edged</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Hydropolitics</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Nile</strong><br />

Wenk, Tobias Hagmann, Mey Eltayeb Ahmed, Moges Shiferaw, and Sanjay<br />

Barbora, has been of particular importance in this regard. Berhanu Debele,<br />

Nathalie Gasser, Laurent Goetschel, Eva Ludi, and Didier Péclard additi<strong>on</strong>ally<br />

provided administrative support. Yacob Arsano deserves special menti<strong>on</strong><br />

<strong>for</strong> being an excellent mentor regarding <strong>Nile</strong> issues in Ethiopia.<br />

I thank Mohamed Abdelmoghny Hamouda, Franziska Sigrist, Evelyne<br />

Tauchnitz, and Demeke Achiso <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir ef<strong>for</strong>ts to align <strong>the</strong>ir M.A. / M.Sc.<br />

projects with my study, and <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> insights I gained both from <strong>the</strong>ir data<br />

and from <strong>the</strong> fruitful discussi<strong>on</strong>s we had. We are all grateful to Dr. Uwe<br />

Serdült <strong>for</strong> his valuable input to <strong>the</strong> network analysis part of our work.<br />

I collectively thank all <strong>the</strong> colleagues I had <strong>the</strong> pleasure of sharing offices<br />

with in Zürich, Bern, Addis Ababa, and Cairo. I am particularly grateful<br />

<strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> prompt and reliable administrative and moral support provided by<br />

<strong>the</strong> staff at both Prof. Zehnder’s and Prof. Wenger’s offices, particularly by<br />

Annina v<strong>on</strong> Muralt, Erika Girod, and Astrid Karrer Dawoud. I am grateful<br />

to Fabian Furter <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> layout of this document, and Christopher Findlay,<br />

Miriam Mas<strong>on</strong> Martineau, and Stefan Zach <strong>for</strong> proofreading services in<br />

different phases of this study.<br />

This study would not have been possible without <strong>the</strong> generous allocati<strong>on</strong><br />

of precious time <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> part of many water sector experts in Egypt and<br />

Ethiopia. Most interviewees did much more than just answer my questi<strong>on</strong>s<br />

by sharing <strong>the</strong>ir pers<strong>on</strong>al views <strong>on</strong> issues of water management and <strong>Nile</strong><br />

Basin cooperati<strong>on</strong>, and thus provided stimulating inputs to this research.<br />

I can <strong>on</strong>ly highlight a few individuals whose support included multiple<br />

encounters or access to key documents: Musa Mohamed and his team at<br />

MoWR Transboundary Rivers Department, Dr. Abdel Fattah Metawie<br />

and <strong>the</strong> staff at <strong>the</strong> MWRI <strong>Nile</strong> Water Sector, Dr. Diaeddin El Quosi, Dr.<br />

Enan Abdallah and <strong>the</strong> NWPR team, Imeru Tamrat, Dr. Khaled Abu Zeid,<br />

Kidanemariam Jembere, Dr. Madgy Hefny, Martha Solom<strong>on</strong>, Mek<strong>on</strong>nen<br />

Luelseged, Prof. Mohamed Nour Eldin, Mohammed Nasser Ezzat, Motuma<br />

Mekasa, Dr. Osman El-Tom, Dr. Shaden Abdel-Gawad and her team at<br />

<strong>the</strong> NWRC, Shimeles Lemma, Yasser Elwan, and Yoseph Endeshaw. I also<br />

thank Dr. Heinz Walker-Nederkoorn and <strong>the</strong> Swiss Embassy in Cairo <strong>for</strong><br />

support in administrative matters.<br />

4

Acknowledgement<br />

Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore, I am greatly indebted to many people who, through <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

pers<strong>on</strong>al friendship, rendered my time in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Nile</strong> Basin all <strong>the</strong> more enjoyable.<br />

To menti<strong>on</strong> just a few: Derese and family, <strong>the</strong> staff at <strong>the</strong> Roma Hotel,<br />

Missa, Taika, Fitsum, Djamila, Hapte, Hashem, Sisay, Mamoush and friends,<br />

Marianne, Fethi, Yoseph, Jasmin and friends, and <strong>the</strong> Plaza team.<br />

Finally, I thank Susanne Leuenberger <strong>for</strong> her innumerable c<strong>on</strong>tributi<strong>on</strong>s<br />

to this work. She not <strong>on</strong>ly provided scientific input, but was also a great<br />

sport in allocating time in tense periods. Most of all, however, she gave me<br />

calm by being <strong>the</strong> best mo<strong>the</strong>r to our little boy.<br />

I dedicate this <strong>the</strong>sis to my parents, who have supported me in every respect<br />

<strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> l<strong>on</strong>g way to <strong>the</strong> completi<strong>on</strong> of this <strong>the</strong>sis.<br />

5

Note <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> structure of this document<br />

The chapters of this <strong>the</strong>sis were written <strong>for</strong> publicati<strong>on</strong> as articles in scientific<br />

journals, not as parts of a m<strong>on</strong>ograph. There<strong>for</strong>e all chapters start with an<br />

abstract, and most of <strong>the</strong>m c<strong>on</strong>tain <strong>the</strong>oretical, methodological, and empirical<br />

secti<strong>on</strong>s. Some duplicati<strong>on</strong> in <strong>the</strong> introductory secti<strong>on</strong>s of <strong>the</strong> chapters<br />

is unavoidable. Since <strong>the</strong> peer review process was still <strong>on</strong>going <strong>for</strong> most<br />

articles at <strong>the</strong> time of printing of this document, <strong>the</strong> versi<strong>on</strong>s published in<br />

<strong>the</strong> journals may not corresp<strong>on</strong>d exactly to <strong>the</strong> chapters of this <strong>the</strong>sis.<br />

6

Table of C<strong>on</strong>tents<br />

List of Figures 11<br />

List of Tables 12<br />

List of Abbreviati<strong>on</strong>s 13<br />

Summary 17<br />

Zusammenfassung 21<br />

1 Introducti<strong>on</strong> 27<br />

1.1 Research questi<strong>on</strong>s and objectives of <strong>the</strong> study 29<br />

1.2 The discursive and analytical c<strong>on</strong>text: What c<strong>on</strong>flict? And<br />

how to analyze it? 31<br />

Systemic and domestic-level explanati<strong>on</strong>s of<br />

<strong>for</strong>eign policy behavior 32<br />

C<strong>on</strong>verging ‘water management’ and ‘water c<strong>on</strong>flict’<br />

perspectives 34<br />

Transboundary river disputes in <strong>the</strong> literature 36<br />

1.3 Delimitati<strong>on</strong>s of <strong>the</strong> research focus 43<br />

1.4 C<strong>on</strong>ceptual framework 44<br />

The ‘two-level game’ 45<br />

Domestic policy processes 50<br />

1.5 Methodological framework 52<br />

Selecti<strong>on</strong> of case study countries 52<br />

Data type and data collecti<strong>on</strong> 53<br />

1.6 Outline of <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>sis 57<br />

7

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Double</str<strong>on</strong>g>-<str<strong>on</strong>g>Edged</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Hydropolitics</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Nile</strong><br />

2 Water challenges in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Nile</strong> Basin 59<br />

2.1 Global and regi<strong>on</strong>al water challenges 59<br />

2.2 The <strong>Nile</strong> Basin 60<br />

Hydrology and water utilizati<strong>on</strong> in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Nile</strong> Basin 61<br />

<strong>Nile</strong> Basin History 66<br />

The current status of <strong>Nile</strong> Basin cooperati<strong>on</strong> 69<br />

3 Internati<strong>on</strong>al River Basins: Management and C<strong>on</strong>flict Perspectives 73<br />

Abstract 73<br />

3.1 Introducti<strong>on</strong> 74<br />

3.2 Resp<strong>on</strong>ses to evolving river utilizati<strong>on</strong> challenges: towards<br />

integrated water management 76<br />

Transboundary water management through internati<strong>on</strong>al<br />

regimes 80<br />

3.3 Water c<strong>on</strong>flicts: water wars and threats to human security 82<br />

Trans<strong>for</strong>ming water c<strong>on</strong>flicts 86<br />

3.4 C<strong>on</strong>clusi<strong>on</strong>s: c<strong>on</strong>verging perspectives 87<br />

4 Driving <strong>for</strong>ces and patterns of water policy making in Egypt 91<br />

8<br />

Abstract 91<br />

4.1 Introducti<strong>on</strong> 92<br />

4.2 Framework of analysis 94<br />

4.3 The general policy-making envir<strong>on</strong>ment in Egypt 96<br />

4.4 Evolving narratives and water policies 98<br />

4.5 Actors in <strong>the</strong> water sector 102<br />

4.6 Cooperati<strong>on</strong> and coordinati<strong>on</strong> in <strong>the</strong> water sector 107<br />

4.7 Selected policy issues 108<br />

Reclamati<strong>on</strong> of new lands 108<br />

Rice producti<strong>on</strong> 110<br />

Waste water quality debate 111<br />

Instituti<strong>on</strong>al re<strong>for</strong>m 113

Table of C<strong>on</strong>tents<br />

4.8 Patterns of policy-making 114<br />

Rati<strong>on</strong>al choice 114<br />

Organizati<strong>on</strong>al processes 116<br />

Governmental politics 117<br />

4.9 C<strong>on</strong>clusi<strong>on</strong>s 119<br />

5 Shaky ground:<br />

Ethiopian water policy making and <strong>Nile</strong> Basin cooperati<strong>on</strong> 121<br />

Abstract 121<br />

5.1 Introducti<strong>on</strong> 122<br />

5.2 Theoretical background 124<br />

5.3 The <strong>Nile</strong> Basin two-level game 125<br />

5.4 Results 128<br />

Water sector actors 129<br />

Diverging actor preferences 134<br />

Instituti<strong>on</strong>al aspects 139<br />

5.5 Syn<strong>the</strong>sis and c<strong>on</strong>clusi<strong>on</strong>s 146<br />

6 Water policy networks in Egypt and Ethiopia 151<br />

Abstract 151<br />

6.1 Introducti<strong>on</strong> 152<br />

6.2 C<strong>on</strong>ceptual framework 154<br />

6.3 Methodology 156<br />

Quality c<strong>on</strong>trol and robustness of data 160<br />

6.4 Results 161<br />

Network comparis<strong>on</strong> 161<br />

The Egyptian water sector 162<br />

The Ethiopian water sector 172<br />

6.5 Summary and Discussi<strong>on</strong> 178<br />

6.6 C<strong>on</strong>clusi<strong>on</strong>s 181<br />

9

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Double</str<strong>on</strong>g>-<str<strong>on</strong>g>Edged</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Hydropolitics</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Nile</strong><br />

7 <str<strong>on</strong>g>Double</str<strong>on</strong>g>-edged <str<strong>on</strong>g>Hydropolitics</str<strong>on</strong>g>: Domestic C<strong>on</strong>straints and<br />

Internati<strong>on</strong>al Cooperati<strong>on</strong> in <strong>the</strong> Eastern <strong>Nile</strong> Basin 185<br />

Abstract 185<br />

7.1 Introducti<strong>on</strong> 186<br />

7.2 C<strong>on</strong>ceptual framework 189<br />

7.3 Results 193<br />

Domestic divides: actors and <strong>the</strong>ir interests 193<br />

Instituti<strong>on</strong>al factors 200<br />

The impact of <strong>the</strong> NBI 203<br />

7.4 Discussi<strong>on</strong> 206<br />

7.5 C<strong>on</strong>clusi<strong>on</strong>s 210<br />

8 C<strong>on</strong>cluding remarks 213<br />

8.1 Summary of main findings and generalizati<strong>on</strong> 213<br />

8.2 Implicati<strong>on</strong>s <strong>for</strong> domestic water policy re<strong>for</strong>ms and<br />

external interventi<strong>on</strong>s in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Nile</strong> Basin 222<br />

8.3 Critical assessment of <strong>the</strong> strength and limitati<strong>on</strong>s of<br />

this study 224<br />

8.4 Suggesti<strong>on</strong>s <strong>for</strong> fur<strong>the</strong>r research 225<br />

8.5 Final remark: <strong>the</strong> future of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Nile</strong> Basin 227<br />

References 229<br />

Appendix: Questi<strong>on</strong>naires used in <strong>the</strong> Social Network Analysis 259<br />

Egyptian case study 260<br />

Ethiopian case study 266<br />

Curriculum Vitae 275<br />

10

List of Figures<br />

1.1 C<strong>on</strong>verging analytical perspectives <strong>on</strong> transboundary<br />

river management 32<br />

1.2 Explaining c<strong>on</strong>flict and cooperati<strong>on</strong> in shared river basins:<br />

Approaches <strong>on</strong> different levels 42<br />

1.3 Basic effects of <strong>the</strong> two-level game 47<br />

2.1 The <strong>Nile</strong> Basin 64<br />

2.2 C<strong>on</strong>flictive and cooperative developments in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Nile</strong> Basin 68<br />

2.3 Advances <strong>on</strong> different tracks towards bilateral or multilateral<br />

cooperati<strong>on</strong> in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Nile</strong> Basin 70<br />

3.1 Comp<strong>on</strong>ents of ‘water management’ and ‘water c<strong>on</strong>flict’<br />

approaches 76<br />

3.2 C<strong>on</strong>vergence of ‘water management’ and ‘water c<strong>on</strong>flict’<br />

perspectives 88<br />

6.1 Effective cooperati<strong>on</strong> in planning network (Egypt) 164<br />

6.2 Actor centralities 170<br />

6.3 Effective cooperati<strong>on</strong> in planning network (Ethiopia) 177<br />

7.1 C<strong>on</strong>ceptual framework linking domestic interest and<br />

internati<strong>on</strong>al negotiati<strong>on</strong> positi<strong>on</strong>s 189<br />

7.2 Spectrum of interests of different actors categories in<br />

Egypt and Ethiopia 195<br />

11

List of Tables<br />

1.1 Comparis<strong>on</strong> of <strong>the</strong> Egyptian and Ethiopian water sectors 54<br />

1.2 ‘Checklist’ <strong>for</strong> water sector instituti<strong>on</strong>al analysis 56<br />

2.1 Populati<strong>on</strong> data, water withdrawal and utilizati<strong>on</strong>, and GNI <strong>for</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>Nile</strong> Basin countries 65<br />

4.1 Analytical framework guiding <strong>the</strong> attributi<strong>on</strong> of water<br />

policy issues to policy-making patterns 95<br />

4.2 Actors in <strong>the</strong> Egyptian water sector 103<br />

4.3 Resp<strong>on</strong>sibilities and roles of <strong>the</strong> different actors in <strong>the</strong><br />

policy process 106<br />

4.4 Influence of patterns of policy making <strong>for</strong> selected policy issues 115<br />

5.1 Domestic factors influencing <strong>the</strong> Ethiopian win-set in <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Nile</strong> Basin negotiati<strong>on</strong>s 128<br />

5.2 Water sector actors in Ethiopia 132<br />

6.1 Linkage types, data types, and trans<strong>for</strong>mati<strong>on</strong> of data 157<br />

6.2 Network density and centralizati<strong>on</strong> 161<br />

6.3 Influence reputati<strong>on</strong> 166<br />

6.4 Influence reputati<strong>on</strong> of departments of each water ministry 168<br />

6.5 Actor categories and subgroups 171<br />

6.6 Sub-network densities within actor categories and subgroups 172<br />

6.7 Main characteristics of <strong>the</strong> water policy networks in<br />

Egypt and Ethiopia 178<br />

8.1 Major domestic c<strong>on</strong>straints to <strong>the</strong> nati<strong>on</strong>al win-sets 215<br />

12

List of Abbreviati<strong>on</strong>s<br />

AAU<br />

ADB<br />

ADLI<br />

AfDB<br />

AHD<br />

AOYE<br />

ASR&T<br />

CC<br />

CEDARE<br />

CIDA<br />

CRDA<br />

DfID<br />

DRC<br />

DSS<br />

EEA<br />

EEAA<br />

EEPCo<br />

EHPEA<br />

EIA<br />

EN<br />

ENCID<br />

ENCOM<br />

ENSAP<br />

ENSAPT<br />

ENTRO<br />

EPA<br />

ERHA<br />

EU<br />

EWWCA<br />

FAO<br />

FDRE<br />

feddan<br />

GDP<br />

GNI<br />

GoE<br />

Addis Ababa University<br />

African Development Bank (see also AfDB)<br />

Agricultural Development Led Industrializati<strong>on</strong><br />

African Development Bank (see also ADB)<br />

Aswan High Dam<br />

Arab Office <strong>for</strong> Youth and Envir<strong>on</strong>ment (Egypt)<br />

Academy of Scientific Research and Technology (Egypt)<br />

Chamber of Commerce<br />

<strong>Center</strong> <strong>for</strong> Envir<strong>on</strong>ment and Development <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> Arab<br />

Regi<strong>on</strong> and Europe (Egypt)<br />

Canadian Development Cooperati<strong>on</strong> Agency<br />

Christian Relief and Development Associati<strong>on</strong> (Ethiopia)<br />

Department <strong>for</strong> Internati<strong>on</strong>al Development (UK)<br />

Democratic Republic of C<strong>on</strong>go<br />

Decisi<strong>on</strong> support system<br />

Ethiopian Ec<strong>on</strong>omics Associati<strong>on</strong><br />

Egyptian Envir<strong>on</strong>mental Affairs Agency<br />

Ethiopian Electric Power Corporati<strong>on</strong><br />

Ethiopian Horticultural Producers and Exporters Associati<strong>on</strong><br />

Envir<strong>on</strong>mental Impact Assessment<br />

Eastern <strong>Nile</strong><br />

Egyptian Nati<strong>on</strong>al Committee <strong>on</strong> Irrigati<strong>on</strong> and Drainage<br />

Eastern <strong>Nile</strong> Council of Ministers<br />

Eastern <strong>Nile</strong> Subsidiary Acti<strong>on</strong> Program<br />

Eastern <strong>Nile</strong> Subsidiary Acti<strong>on</strong> Program Team<br />

Eastern <strong>Nile</strong> Technical Regi<strong>on</strong>al Office<br />

Envir<strong>on</strong>mental Protecti<strong>on</strong> Agency (Ethiopia)<br />

Ethiopian Rainwater Harvesting Associati<strong>on</strong><br />

European Uni<strong>on</strong><br />

Ethiopian Water Works C<strong>on</strong>structi<strong>on</strong> Authority<br />

Food and Agriculture Organizati<strong>on</strong> of <strong>the</strong> United Nati<strong>on</strong>s<br />

Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia<br />

Unit of area used in Egypt; 1 feddan = 0,42 ha<br />

Gross Domestic Product<br />

Gross Nati<strong>on</strong>al Income<br />

used <strong>for</strong> ei<strong>the</strong>r Government of Egypt or Government of<br />

Ethiopia in <strong>the</strong> respective nati<strong>on</strong>al documents<br />

13

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Double</str<strong>on</strong>g>-<str<strong>on</strong>g>Edged</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Hydropolitics</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Nile</strong><br />

GTZ Deutsche Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit<br />

(German Development Cooperati<strong>on</strong> Agency)<br />

HEP Hydro-electric power<br />

IDEN Integrated Development of <strong>the</strong> Eastern <strong>Nile</strong><br />

IR<br />

Internati<strong>on</strong>al Relati<strong>on</strong>s<br />

IWMI Internati<strong>on</strong>al Water Management Institute<br />

IWRM Integrated Water Resources Management<br />

JICA Japanese Development Cooperati<strong>on</strong> Agency<br />

MHUNC Ministry of Housing, Utilities and New Communities<br />

(Egypt)<br />

MoALR Ministry of Agriculture and Land Reclamati<strong>on</strong> (Egypt)<br />

MoARD Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (Ethiopia)<br />

MoFA Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Egypt/ Ethiopia)<br />

MoFED Ministry of Finance and Ec<strong>on</strong>omic Development (Ethiopia)<br />

MoH Ministry of Health (Ethiopia)<br />

MoHP Ministry of Health and Populati<strong>on</strong> (Egypt)<br />

MoIC Ministry of Internati<strong>on</strong>al Cooperati<strong>on</strong> (Egypt)<br />

MoLD Ministry of Local Development (Egypt)<br />

MoP Ministry of Planning (Egypt)<br />

MoSEA Ministry of State <strong>for</strong> Envir<strong>on</strong>mental Affairs (Egypt)<br />

MoTI Ministry of Trade and Industry (Egypt)<br />

MoWR Ministry of Water Resources (Ethiopia)<br />

MWRI Ministry of Water Resources and Irrigati<strong>on</strong> (Egypt)<br />

NBD <strong>Nile</strong> Basin Discourse<br />

NBI<br />

<strong>Nile</strong> Basin Initiative<br />

NELSAP <strong>Nile</strong> Equatorial Lakes Subsidiary Acti<strong>on</strong> Program<br />

NFP Nati<strong>on</strong>al Focal Point<br />

NGO N<strong>on</strong> Governmental Organizati<strong>on</strong><br />

<strong>Nile</strong>-COM Council of Ministers of Water Affairs of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Nile</strong> Basin<br />

States<br />

<strong>Nile</strong>-SEC <strong>Nile</strong> Basin Initiative Secretariat<br />

<strong>Nile</strong>-TAC <strong>Nile</strong> Basin Initiative Technical Advisory Committee<br />

North Sinai HC North Sinai Holding Company (Egypt)<br />

NWRC Nati<strong>on</strong>al Water Research <strong>Center</strong> (Egypt)<br />

NWRP Nati<strong>on</strong>al Water Resources Plan (Egypt)<br />

O&M Operati<strong>on</strong> and Maintenance<br />

OCDC Orthodox Church Development Cooperati<strong>on</strong> (Ethiopia)<br />

PA<br />

People’s Assembly<br />

PMU Project Management Unit<br />

PRSP Poverty Reducti<strong>on</strong> Strategy Paper<br />

PWSHC Potable Water and Sanitati<strong>on</strong> Holding Company (Egypt)<br />

14

List of Abbreviati<strong>on</strong>s<br />

R&D Research and Development<br />

SAP<br />

Subsidiary Acti<strong>on</strong> Program<br />

SFD<br />

Social Fund <strong>for</strong> Development (Egypt)<br />

SVP<br />

Shared Visi<strong>on</strong> Program<br />

TAC Technical Advisory Commissi<strong>on</strong><br />

TECCONILE Technical Co-operati<strong>on</strong> Committee <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> Promoti<strong>on</strong> of <strong>the</strong><br />

Development and Envir<strong>on</strong>mental Protecti<strong>on</strong> of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Nile</strong><br />

Basin<br />

UNDP United Nati<strong>on</strong>s Development Programme<br />

UNESCO United Nati<strong>on</strong>s Educati<strong>on</strong>al, Scientific, and Cultural<br />

Organizati<strong>on</strong><br />

UNICEF United Nati<strong>on</strong>s Children’s Fund<br />

USAID United States Agency <strong>for</strong> Internati<strong>on</strong>al Development<br />

WB<br />

World Bank<br />

WSS Water Supply and Sanitati<strong>on</strong><br />

WUA Water User Associati<strong>on</strong><br />

WWDSE Water Works Design & Supervisi<strong>on</strong> Enterprise (Ethiopia)<br />

15

Summary<br />

T<br />

his <strong>the</strong>sis focuses <strong>on</strong> domestic processes of water policy making in Egypt<br />

and Ethiopia in <strong>the</strong> c<strong>on</strong>text of transboundary c<strong>on</strong>flict and cooperati<strong>on</strong><br />

in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Nile</strong> Basin.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> light of increasing global water demands, transboundary rivers<br />

are often portrayed both as a source of inter-state c<strong>on</strong>flict and as a catalyst<br />

<strong>for</strong> internati<strong>on</strong>al cooperati<strong>on</strong>. Analysts comm<strong>on</strong>ly explain <strong>the</strong> c<strong>on</strong>flictive<br />

or cooperative behavior of riparian states in shared basins by referring<br />

to characteristics of <strong>the</strong> internati<strong>on</strong>al system (e.g., <strong>the</strong> hydrological c<strong>on</strong>nected-ness,<br />

<strong>the</strong> overall level of water scarcity, <strong>the</strong> geo-political c<strong>on</strong>text, or<br />

<strong>the</strong> level of ec<strong>on</strong>omic integrati<strong>on</strong> in a basin) and attributes of <strong>the</strong> riparian<br />

states (e.g., <strong>the</strong>ir geographical positi<strong>on</strong> al<strong>on</strong>g <strong>the</strong> course of <strong>the</strong> river,<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir ec<strong>on</strong>omic and military power, existing and planned domestic water<br />

uses). Hence, most studies <strong>on</strong> transboundary river basins at least implicitly<br />

apply an analytical perspective rooted in ‘Internati<strong>on</strong>al Relati<strong>on</strong>s’ <strong>the</strong>ories<br />

and tend to view riparian states as unitary rati<strong>on</strong>al actors pursuing specific<br />

‘nati<strong>on</strong>al interests’.<br />

Such a ‘systemic’ perspective c<strong>on</strong>trasts with <strong>the</strong> observati<strong>on</strong> that, in<br />

many shared river basins, <strong>the</strong> course of transboundary c<strong>on</strong>flict and cooperati<strong>on</strong><br />

is significantly influenced by domestic c<strong>on</strong>straints to <strong>the</strong> ratificati<strong>on</strong><br />

or implementati<strong>on</strong> of transboundary agreements. The inter-relati<strong>on</strong>s between<br />

domestic policy processes and transboundary cooperati<strong>on</strong> have so far<br />

largely been approached in a qualitative and anecdotal manner. The present<br />

<strong>the</strong>sis addresses this gap in <strong>the</strong> transboundary river literature by applying<br />

a systematic perspective <strong>on</strong> domestic water sector actors, instituti<strong>on</strong>s, and<br />

processes in two <strong>Nile</strong> Basin countries (Egypt and Ethiopia).<br />

The analytical focus <strong>on</strong> domestic actors and instituti<strong>on</strong>s in transboundary<br />

river basins relates to recent developments both at <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>oretical and<br />

practical level. New <strong>the</strong>oretical approaches in political sciences integrate<br />

systemic (i.e., Internati<strong>on</strong>al Relati<strong>on</strong>s) and domestic (Public Policy Analysis)<br />

explanati<strong>on</strong>s of <strong>the</strong> <strong>for</strong>eign policy behavior of states. At <strong>the</strong> same time, prac-<br />

17

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Double</str<strong>on</strong>g>-<str<strong>on</strong>g>Edged</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Hydropolitics</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Nile</strong><br />

titi<strong>on</strong>ers and modern water management paradigms increasingly highlight<br />

<strong>the</strong> important role of n<strong>on</strong>-state actors and water sector instituti<strong>on</strong>s. In <strong>the</strong><br />

c<strong>on</strong>text of <strong>the</strong>se c<strong>on</strong>verging approaches, <strong>the</strong> noti<strong>on</strong> of ‘water c<strong>on</strong>flict’ has<br />

evolved from a narrow focus <strong>on</strong> inter-state warfare to emphasizing <strong>the</strong><br />

impacts of n<strong>on</strong>-violent transboundary disputes and local level c<strong>on</strong>flicts <strong>on</strong><br />

‘human security’. Linkages between domestic instituti<strong>on</strong>s and water policies<br />

<strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>on</strong>e hand, and challenges to establish basin-wide instituti<strong>on</strong>s<br />

to foster transboundary cooperati<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r have become more and<br />

more obvious.<br />

The present <strong>the</strong>sis adopts a two-level game perspective to c<strong>on</strong>ceptualize<br />

<strong>the</strong> mechanisms linking domestic policy processes to <strong>the</strong> progress of transboundary<br />

negotiati<strong>on</strong>s. The c<strong>on</strong>cept of nati<strong>on</strong>al win-sets – i.e., <strong>the</strong> range of<br />

domestically ratifiable policy opti<strong>on</strong>s – is used to identify and explain <strong>the</strong><br />

specific negotiati<strong>on</strong> challenges and to discuss implicati<strong>on</strong>s <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> potential<br />

negotiati<strong>on</strong> outcomes. The study places <strong>the</strong> analytical focus <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> interests<br />

and c<strong>on</strong>stellati<strong>on</strong>s of domestic actors and water sector instituti<strong>on</strong>s, as well as<br />

<strong>on</strong> specific ‘patterns’ of policy-making (i.e., rati<strong>on</strong>al choice decisi<strong>on</strong>-making,<br />

organizati<strong>on</strong>al routines, or interest bargaining between domestic actors). The<br />

empirical data were collected through expert and stakeholder interviews,<br />

document analysis, and <strong>the</strong> applicati<strong>on</strong> of Social Network Analysis as a<br />

quantitative tool.<br />

The <strong>the</strong>sis presents results at two different levels. First, <strong>the</strong> water sectors<br />

of Egypt and Ethiopia are analyzed with regard to <strong>the</strong>ir capacity to jointly<br />

design and implement effective and sustainable strategies <strong>for</strong> transboundary<br />

river development. Sec<strong>on</strong>d, <strong>the</strong> study produces general insights regarding<br />

<strong>the</strong> nature of transboundary river c<strong>on</strong>flicts and <strong>the</strong> challenges of c<strong>on</strong>flict<br />

mitigati<strong>on</strong>.<br />

Domestic factors significantly c<strong>on</strong>strain <strong>the</strong> ability of policy-makers in<br />

<strong>the</strong> Egyptian water sector to accept any de jure re-allocati<strong>on</strong> of water quotas<br />

at <strong>the</strong> internati<strong>on</strong>al level. Domestic c<strong>on</strong>straints arise from 1) <strong>the</strong> widely held<br />

view that Egypt’s current water share of 55.5 billi<strong>on</strong> cubic meters per year is<br />

legitimate and n<strong>on</strong>-negotiable, 2) <strong>the</strong> limited success of <strong>the</strong> water sector in<br />

influencing related sectoral policies that determine <strong>the</strong> total nati<strong>on</strong>al water<br />

demand, particularly regarding irrigati<strong>on</strong> expansi<strong>on</strong>, and 3) <strong>the</strong> failure to<br />

design and implement effective policies regarding demand management or<br />

18

Summary<br />

polluti<strong>on</strong> c<strong>on</strong>trol. The Egyptian water governance system is highly centralized,<br />

and <strong>on</strong>ly a small number of n<strong>on</strong>-state actors have direct access to <strong>the</strong><br />

policy processes. Decisi<strong>on</strong>s regarding <strong>the</strong> traditi<strong>on</strong>al core tasks of <strong>the</strong> water<br />

ministry, e.g., inter-sectoral water allocati<strong>on</strong>, are based to a large extent <strong>on</strong><br />

‘rati<strong>on</strong>al choice’ decisi<strong>on</strong>-making patterns. Water policy issues that have<br />

emerged more recently, such as water quality or demand management, are<br />

subject to intensive interest bargaining between different domestic policy<br />

actors at both <strong>the</strong> planning and <strong>the</strong> implementati<strong>on</strong> stage. The lack of intersectoral<br />

policy integrati<strong>on</strong> and <strong>the</strong> low level of stakeholder participati<strong>on</strong><br />

c<strong>on</strong>strain <strong>the</strong> ability of water authorities to design and evaluate alternative<br />

policy opti<strong>on</strong>s both domestically and in <strong>the</strong> c<strong>on</strong>text of transboundary<br />

cooperati<strong>on</strong>.<br />

Most water sector actors in Ethiopia highlight <strong>the</strong> right of upstream<br />

countries to a higher share of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Nile</strong> and <strong>the</strong> need <strong>for</strong> a legal and instituti<strong>on</strong>al<br />

framework agreement re-allocating nati<strong>on</strong>al water abstracti<strong>on</strong><br />

quotas. There is a broad c<strong>on</strong>sensus as to <strong>the</strong> need <strong>for</strong> enhanced hydropower<br />

development and <strong>the</strong> expansi<strong>on</strong> of irrigated agriculture in Ethiopia. Actor<br />

preferences are divided to some extent, however, with regard to <strong>the</strong> priority<br />

assigned to large-scale infrastructure projects (large dams and water<br />

diversi<strong>on</strong>s) as opposed to more localized and household-centered strategies<br />

(rainwater harvesting, small-scale diversi<strong>on</strong>s and irrigati<strong>on</strong> schemes).<br />

Different rati<strong>on</strong>ales and priorities are applied to issues of food security,<br />

ec<strong>on</strong>omic growth, pro-poor development, and envir<strong>on</strong>mental c<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong>.<br />

D<strong>on</strong>or agencies, decentralized water authorities, and <strong>the</strong> planned River<br />

Basin Organizati<strong>on</strong>s somewhat c<strong>on</strong>strain <strong>the</strong> decisi<strong>on</strong> aut<strong>on</strong>omy of <strong>the</strong><br />

central government. Capacity c<strong>on</strong>straints arising from poor inter-ministerial<br />

coordinati<strong>on</strong>, overlapping levels of planning resp<strong>on</strong>sibilities, limited stakeholder<br />

participati<strong>on</strong>, and limited research capacities reduce <strong>the</strong> government’s<br />

ability to evaluate and exploit trade-offs between different domestic and<br />

transboundary river development strategies.<br />

The analysis of domestic water sector networks illustrates <strong>the</strong> similarities<br />

and differences between <strong>the</strong> policy-making patterns in Egypt and<br />

Ethiopia. Governmental agencies occupy central network positi<strong>on</strong>s in both<br />

countries. The limited c<strong>on</strong>nectedness of sectoral agencies in both countries<br />

leads to fragmented policies, which in <strong>the</strong> case of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Nile</strong> Basin translates<br />

19

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Double</str<strong>on</strong>g>-<str<strong>on</strong>g>Edged</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Hydropolitics</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Nile</strong><br />

into a focus <strong>on</strong> – unilaterally or jointly planned – infrastructure projects.<br />

Internati<strong>on</strong>al d<strong>on</strong>or agencies play an important role by c<strong>on</strong>necting different<br />

types of domestic actors in in<strong>for</strong>mati<strong>on</strong> exchange networks. The<br />

greater prominence of regi<strong>on</strong>al state water authorities and NGOs in <strong>the</strong><br />

Ethiopian water sector indicates a somewhat higher potential <strong>for</strong> pluralistic<br />

water policy making. The weak instituti<strong>on</strong>al research capacity and <strong>the</strong><br />

dependence <strong>on</strong> c<strong>on</strong>sultants in <strong>the</strong> policy <strong>for</strong>mulati<strong>on</strong> process affect <strong>the</strong><br />

ability of <strong>the</strong> Ethiopian water authorities to design effective and broadly<br />

supported policies.<br />

In c<strong>on</strong>clusi<strong>on</strong>, <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>sis dem<strong>on</strong>strates that <strong>the</strong> negotiati<strong>on</strong> positi<strong>on</strong>s and<br />

river management strategies of riparian states in transboundary river basins<br />

can be c<strong>on</strong>siderably c<strong>on</strong>strained by divided actor preferences and deficient<br />

policy processes at <strong>the</strong> domestic level. Domestic c<strong>on</strong>straints narrow down <strong>the</strong><br />

win-sets <strong>for</strong> internati<strong>on</strong>al cooperati<strong>on</strong> ei<strong>the</strong>r by limiting <strong>the</strong> government’s<br />

decisi<strong>on</strong> aut<strong>on</strong>omy and implementati<strong>on</strong> capacity, or by reducing <strong>the</strong> range<br />

of policy choices available to <strong>the</strong> decisi<strong>on</strong>-makers. Inadequate planning<br />

capacities limit <strong>the</strong> riparian countries’ ability to effectively coordinate <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

water policies within a cooperative framework. N<strong>on</strong>-participatory policy<br />

processes fail to tap a significant segment of <strong>the</strong> domestically available<br />

expertise in <strong>the</strong> ef<strong>for</strong>t to design and implement policies that are compatible<br />

with <strong>the</strong> interests of co-riparian states.<br />

The <strong>Nile</strong> states could expand <strong>the</strong> range of domestically ratifiable opti<strong>on</strong>s<br />

<strong>for</strong> a basin-wide river development framework by fur<strong>the</strong>r including top-level<br />

nati<strong>on</strong>al planners and decisi<strong>on</strong>-makers in <strong>the</strong> transboundary negotiati<strong>on</strong>s,<br />

by better integrating sectoral policies to address trade-offs between different<br />

water uses, and by seeking transboundary mechanisms to reward progress<br />

made in demand management and quality c<strong>on</strong>trol.<br />

20

Zusammenfassung<br />

D<br />

ie vorliegende Dissertati<strong>on</strong> untersucht nati<strong>on</strong>ale Planungs- und<br />

Implementierungsprozesse im Wassersektor v<strong>on</strong> Ägypten und<br />

Äthiopien vor dem Hintergrund der internati<strong>on</strong>alen Verhandlungen um<br />

die Verteilung und gemeinsame Nutzung des Wassers des Nils.<br />

Die zunehmende K<strong>on</strong>kurrenz um Wassernutzungsrechte an grenzüberschreitenden<br />

Flüssen wird oft als Ursache zukünftiger ‘Wasserkriege’<br />

genannt. Schnelles Bevölkerungswachstum und das Fehlen grenzüberschreitender<br />

Instituti<strong>on</strong>en zur Harm<strong>on</strong>isierung v<strong>on</strong> nati<strong>on</strong>alen<br />

Wassernutzungsstrategien lassen ein vermehrtes Auftreten v<strong>on</strong> K<strong>on</strong>flikten<br />

zwischen Flussanrainern befürchten. Die Abflussregulierung wie auch die<br />

Verteilung v<strong>on</strong> Nutzungsrechten zwischen den Nilstaaten ist seit langem<br />

umstritten. Die geplante Wasserentnahme zur Bewässerung im Oberlauf<br />

(etwa in Äthiopien) bedroht bestehende Nutzungen im Unterlauf (vor allem<br />

in Ägypten). Die v<strong>on</strong> internati<strong>on</strong>alen Geldgebern unterstützte und v<strong>on</strong> allen<br />

Nilländern getragene <strong>Nile</strong> Basin Initiative (NBI) bildet den Rahmen für<br />

internati<strong>on</strong>ale Verhandlungen um ein neues rechtliches und instituti<strong>on</strong>elles<br />

Abkommen zwischen den zehn Nilstaaten. Daneben strebt die NBI die<br />

Schaffung eines k<strong>on</strong>kreten Mehrwerts durch Investiti<strong>on</strong>sprojekte und eine<br />

Stärkung nati<strong>on</strong>aler Planungskapazitäten an.<br />

Wissenschaftliche Analysen zu den Ursachen internati<strong>on</strong>aler<br />

Wasserk<strong>on</strong>flikte wenden meist implizit oder explizit <strong>the</strong>oretische<br />

Ansätze aus dem Fachgebiet der ‘Internati<strong>on</strong>alen Beziehungen’ an. Solche<br />

‘systemische’ Erklärungsmodelle stützen sich k<strong>on</strong>zepti<strong>on</strong>ell vorwiegend<br />

auf die Beschreibung des internati<strong>on</strong>alen Systems (etwa die generelle<br />

Wasserknappheit, den geo-politischen K<strong>on</strong>text, die ök<strong>on</strong>omische Integrati<strong>on</strong><br />

zwischen den Anrainerstaaten) sowie auf Attribute der Anrainerstaaten<br />

selbst (z.B. ihre Lage am Fluss, ihr spezifischer Wasserbedarf, ihre ök<strong>on</strong>omische<br />

und militärische Stärke). Die Anrainerstaaten werden oft vereinfachend<br />

als einheitliche rati<strong>on</strong>ale Akteure betrachtet, welche bestimmte<br />

‘nati<strong>on</strong>ale Interessen’ verfolgen. Innerstaatliche Entscheidungsprozesse und<br />

21

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Double</str<strong>on</strong>g>-<str<strong>on</strong>g>Edged</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Hydropolitics</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Nile</strong><br />

politische Instituti<strong>on</strong>en werden dabei als untergeordnete Erklärungsvariablen<br />

behandelt oder vernachlässigt.<br />

Untersuchungen aus zahlreichen internati<strong>on</strong>alen Flussbecken verdeutlichen<br />

jedoch die entscheidende Rolle nati<strong>on</strong>aler Instituti<strong>on</strong>en und<br />

Policy-Prozesse bezüglich der k<strong>on</strong>fliktiven oder kooperativen Ausprägungen<br />

der zwischenstaatlichen Beziehungen. Die Aushandlung internati<strong>on</strong>aler<br />

Abkommen, deren <strong>for</strong>melle oder in<strong>for</strong>melle Ratifizierung sowie<br />

die tatsächliche Umsetzung hängen entscheidend v<strong>on</strong> den Interessen<br />

nati<strong>on</strong>aler Akteure und ihrem jeweiligen Einfluss auf die nati<strong>on</strong>alen<br />

Entscheidungsprozesse ab. Die Interakti<strong>on</strong>en zwischen nati<strong>on</strong>alen und<br />

internati<strong>on</strong>alen Planungs- und Entscheidungsprozessen im Zusammenhang<br />

mit grenzüberschreitenden Flüssen wurden bisher meist unsystematisch<br />

und oft nur anekdotenhaft behandelt. Die vorliegende Studie präsentiert<br />

eine systematische Untersuchung der Zusammenhänge zwischen nati<strong>on</strong>aler<br />

Wasserpolitik und grenzüberschreitender Zusammenarbeit anhand der<br />

Fallstudie des Nils und zwei seiner Anrainerstaaten.<br />

Eine genaue Betrachtung der Berührungsfläche zwischen nati<strong>on</strong>aler<br />

und internati<strong>on</strong>aler Wasserpolitik bietet sich aus mehreren Gründen an.<br />

Auf k<strong>on</strong>zepti<strong>on</strong>eller Ebene trägt sie der häufig genannten Forderung<br />

nach einer Integrati<strong>on</strong> der Forschungsansätze der ‘Internati<strong>on</strong>alen<br />

Beziehungen’ und ‘Vergleichenden Politikwissenschaft’ (Public Policy<br />

Analysis) Rechnung. In der Praxis nehmen nicht-staatliche Akteure und<br />

partizipative Policy-Prozesse in der Evaluati<strong>on</strong> und in der Entwicklung<br />

v<strong>on</strong> Wasserbewirtschaftungsstrategien eine immer grössere Rolle ein.<br />

Innerstaatlichen Entscheidungs- und Umsetzungsprozessen kommt<br />

daher auch bezüglich einer internati<strong>on</strong>alen Harm<strong>on</strong>isierung nati<strong>on</strong>aler<br />

Strategien eine wachsende Bedeutung zu.<br />

Die vorliegende Studie stützt sich auf den k<strong>on</strong>zepti<strong>on</strong>ellen Ansatz des<br />

‘Two-Level Game’ zur Analyse der Schnittstelle zwischen nati<strong>on</strong>aler und<br />

internati<strong>on</strong>aler Wasserpolitik. Dabei spielt das nati<strong>on</strong>ale ‘Win-Set’ – also die<br />

Menge der für eine entscheidende Mehrheit der nati<strong>on</strong>alen Akteure akzeptablen<br />

Policy-Opti<strong>on</strong>en – eine wichtige Rolle. Das ‘Win-Set’ bestimmt den<br />

Verhandlungsspielraum der Verhandlungsführer in jedem Anrainerstaat, und<br />

damit auch die Aussicht auf ein internati<strong>on</strong>ales Abkommen. Die Studie untersucht<br />

die nati<strong>on</strong>alen ‘Win-Sets’ anhand der Analyse v<strong>on</strong> Akteursinteressen<br />

22

Zusammenfassung<br />

und Akteursk<strong>on</strong>stellati<strong>on</strong>en, der nati<strong>on</strong>alen politischen Instituti<strong>on</strong>en,<br />

sowie der spezifischen ‘Muster’ der Politikgestaltung (‘Rati<strong>on</strong>al Choice’,<br />

‘Organizati<strong>on</strong>al Processes’, ‘Governmental Politics’). Die Untersuchung<br />

beruht auf Daten aus bestehenden Policy-Dokumenten, Experten- und<br />

Akteursbefragungen, sowie aus einer systematischen Netzwerkanalyse.<br />

Die Entscheidungsträger im ägyptischen Wassersektor haben aus<br />

verschiedenen Gründen einen eingeschränkten Verhandlungsspielraum<br />

bezüglich einer Redukti<strong>on</strong> der nati<strong>on</strong>alen Wasserentnahmequote zugunsten<br />

der Oberanrainer. Zum einen hat sich die aktuelle Quote v<strong>on</strong> 55.5<br />

Milliarden Kubikmetern pro Jahr, festgelegt in einem bilateralen Vertrag<br />

mit dem Sudan, als nicht verhandelbarer ‘historischer’ Anspruch in den<br />

Narrativen der meisten ägyptischen Akteure verankert. Zum anderen hat<br />

das Wasserministerium nur bedingten Einfluss auf die Wassernutzung<br />

in anderen Sektoren und damit auf den totalen nati<strong>on</strong>alen Wasserbedarf.<br />

Staatliche und privatwirtschaftliche Projekte zur Gewinnung v<strong>on</strong> landwirtschaftlichem<br />

Land prägen die nati<strong>on</strong>ale Wasserpolitik entscheidend.<br />

K<strong>on</strong>krete Bemühungen, den Wasserbedarf durch Effizienzsteigerungen<br />

und eine volkswirtschaftliche Umorientierung zu verringern, sind mit<br />

zahlreichen bürokratischen Hindernissen und dem Widerstand einzelner<br />

Akteursgruppen k<strong>on</strong>fr<strong>on</strong>tiert. Der ägyptische Wassersektor ist stark zentralisiert<br />

und bietet nur wenigen nicht-staatlichen Akteuren eine effektive<br />

Mitsprachemöglichkeit. Kernaufgaben des Wasserministeriums, wie<br />

etwa die Allokati<strong>on</strong> v<strong>on</strong> Wasser zwischen verschiedenen Sektoren, folgen<br />

vornehmlich einem ‘rati<strong>on</strong>alen’ Entscheidungsprozess. Neuere Aufgaben<br />

des Wassersektors, etwa die Eindämmung der Verschmutzung oder die<br />

Verminderung des Wasserverbrauchs, sind in der Planung und Umsetzung<br />

stärker v<strong>on</strong> der Kooperati<strong>on</strong> verschiedener Akteure des Wassersektors abhängig,<br />

und folgen daher anderen Entscheidungsmustern.<br />

Die meisten einflussreichen Akteure im äthiopischen Wassersektor<br />

<strong>for</strong>dern eine de jure Umverteilung der Wassernutzungsrechte am Nil zugunsten<br />

der bisher kaum berücksichtigten Oberanrainer. Diese Haltung trägt<br />

vor allem der Forderung nach ‘Fairness’ im internati<strong>on</strong>alen Verteilungsmuster<br />

Rechnung, und ist weniger durch eine k<strong>on</strong>krete Bedrohung bestehender<br />

oder geplanter Wassernutzung erklärt. Die Notwendigkeit des Ausbaus der<br />

Wasserkraftgewinnung und der Bewässerungslandwirtschaft in Äthiopien<br />

23

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Double</str<strong>on</strong>g>-<str<strong>on</strong>g>Edged</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Hydropolitics</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Nile</strong><br />

ist kaum umstritten. Allerdings bestehen Meinungsunterschiede bezüglich<br />

der geeigneten Grössenordnung und Nutzung entsprechender Projekte.<br />

Nati<strong>on</strong>ale Akteure beurteilen grossangelegte Infrastrukturprojekte<br />

unterschiedlich je nach ihren organisati<strong>on</strong>ellen Interessen und ihrer<br />

relativen Priorisierung verschiedener Ziele wie Ernährungssicherheit,<br />

Wirtschaftswachstum, Armutsbekämpfung oder Erhaltung naturnaher<br />

Ökosysteme. Stärker als in Ägypten nehmen in Äthiopien bi- und multilaterale<br />

Geldgeber, unabhängige Nicht-Regierungsorganisati<strong>on</strong>en und dezentrale<br />

Verwaltungseinheiten an nati<strong>on</strong>alen und sub-nati<strong>on</strong>alen Planungs- und<br />

Umsetzungsprozessen teil. Diese Pluralität und die Abhängigkeit v<strong>on</strong> externen<br />

Finanzmitteln und Expertise schränken den Handlungsspielraum der<br />

äthiopischen Regierung im Hinblick auf die internati<strong>on</strong>alen Verhandlungen<br />

um eine kooperative Nutzung des Nils etwas ein.<br />

Die Betrachtung der Akteursnetzwerke in den Wassersektoren<br />

in Ägypten und Äthiopien verdeutlicht die Gemeinsamkeiten und<br />

Unterschiede in den Politikprozessen der beiden Länder. Staatliche Akteure<br />

nehmen in beiden Netzwerken zentrale Positi<strong>on</strong>en ein, sind gleichzeitig aber<br />

relativ schwach miteinander verknüpft. Internati<strong>on</strong>ale Geldgeber spielen<br />

eine wichtige Rolle, insbes<strong>on</strong>dere als Vermittler v<strong>on</strong> In<strong>for</strong>mati<strong>on</strong>en zwischen<br />

verschiedenen Akteurstypen. Die vergleichsweise hohe Pluralität<br />

im äthiopischen Wassersektor vermindert die staatliche Dominanz der<br />

Zentralregierung in der Planung grosser Infrastrukturprojekte nur unwesentlich.<br />

Die relativ geringe Forschungskapazität und die Abhängigkeit<br />

v<strong>on</strong> Beratungsfirmen in Äthiopien beeinträchtigt dagegen die Effektivität<br />

sowie die gesellschaftliche Verankerung und Legitimität der nati<strong>on</strong>alen<br />

Wasser-Policies.<br />

Als Folge des schwachen Einbezugs der Wassernutzer und nicht-staatlicher<br />

Akteure sind nati<strong>on</strong>ale Strategien zur Eindämmung der Verschmutzung<br />

und Steigerung der Nutzungseffizienz in beiden Ländern nur beschränkt erfolgreich.<br />

Dadurch steigt der Anreiz für beide Länder, ihre Wasserversorgung<br />

durch Abkommen auf der zwischenstaatlichen Ebene zu erhöhen, entweder<br />

durch eine Umverteilung nati<strong>on</strong>aler Entnahmerechte oder durch gemeinsame<br />

Infrastrukturprojekte.<br />

Die vorliegende Studie zeigt auf, dass die Verhandlungspositi<strong>on</strong>en in den<br />

Nilländern entscheidend durch Faktoren der nati<strong>on</strong>alen Politikgestaltung<br />

24

Zusammenfassung<br />

geprägt sind. Der Umfang der nati<strong>on</strong>alen ‘Win-Sets’ ist eine Funkti<strong>on</strong><br />

der verschiedenen Akteursinteressen und der Instituti<strong>on</strong>en, welche den<br />

Einfluss der Akteure in den relevanten Entscheidungsprozessen bestimmen.<br />

Einschränkungen der ‘Win-Sets’ resultieren sowohl aus der<br />

Beschränkung der Entscheidungsaut<strong>on</strong>omie der Regierung, als auch<br />

aus Beeinträchtigungen der Planungs- und Umsetzungskapazität im<br />

Wassersektor. Eine weit reichende Harm<strong>on</strong>isierung der wirtschaftlichen<br />

Ziele und Wassernutzungsstrategien in den Nilländern ist zudem erschwert<br />

durch hohe Planungsunsicherheiten.<br />

Der momentane instituti<strong>on</strong>elle Verhandlungsrahmen mit den Wasserund<br />

Aussenministerien als zentrale Verhandlungsführer, zusammen<br />

mit der lückenhaften Koordinati<strong>on</strong> unter den relevanten staatlichen<br />

Akteuren auf beiden Seiten, steht einer stärker integrierten internati<strong>on</strong>alen<br />

Zusammenarbeit zwischen den Nilländern im Weg. Die Fokusierung auf<br />

Infrastrukturprojekte und auf die de jure Verteilung v<strong>on</strong> Nutzungsrechten<br />

ist dadurch teilweise erklärbar. Ein stärkerer Einbezug v<strong>on</strong> höchsten<br />

Entscheidungsträgern und Planungsinstituti<strong>on</strong>en in den internati<strong>on</strong>alen<br />

Verhandlungen, und eine bessere Zusammenarbeit zwischen allen<br />

nati<strong>on</strong>alen Interessensgruppen erhöht die Chance, dass der langfristige und<br />

gesamtwirtschafliche Nutzen einer verstärkten internati<strong>on</strong>alen Kooperati<strong>on</strong><br />

erkannt und auch gegen die Interessen einzelner Akteure k<strong>on</strong>sequent angestrebt<br />

wird.<br />

25

1 Introducti<strong>on</strong><br />

T<br />

he growing global demand <strong>for</strong> freshwater has given rise both to speculati<strong>on</strong>s<br />

<strong>on</strong> future ‘water wars’ and to calls <strong>for</strong> intensified cooperati<strong>on</strong> am<strong>on</strong>g<br />

<strong>the</strong> riparian states in shared river basins. In <strong>the</strong> last two decades, scholars<br />

and policy-makers have made c<strong>on</strong>siderable progress towards a better understanding<br />

of <strong>the</strong> c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s and mechanisms governing transboundary river<br />

c<strong>on</strong>flicts and cooperati<strong>on</strong>. Theory-guided accounts of river basin c<strong>on</strong>flicts,<br />

however, tend to c<strong>on</strong>ceptualize riparian states as unitary rati<strong>on</strong>al actors aiming<br />

to maximize <strong>the</strong>ir utility in respect of a ‘nati<strong>on</strong>al interest’. Such ‘systemic’<br />

c<strong>on</strong>ceptualizati<strong>on</strong>s fail to fully explain <strong>the</strong> observed variati<strong>on</strong> of success<br />

and failure in transboundary regime-building and cooperati<strong>on</strong>. This <strong>the</strong>sis<br />

challenges <strong>the</strong> perspective of riparian states as unitary actors by analyzing<br />

interacti<strong>on</strong>s between <strong>the</strong> domestic processes of water policy making and<br />

<strong>the</strong> transboundary negotiati<strong>on</strong>s in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Nile</strong> Basin. The study explores new<br />

ground by systematically addressing determinants of transboundary c<strong>on</strong>flict<br />

and cooperati<strong>on</strong> rooted in domestic interest divides and water governance<br />

instituti<strong>on</strong>s.<br />

Demographic pressure as well as growing c<strong>on</strong>sumpti<strong>on</strong> and polluti<strong>on</strong><br />

levels pose tremendous challenges to policy-makers and instituti<strong>on</strong>s in <strong>the</strong><br />

water sector. The availability of freshwater <strong>for</strong> human activities fluctuates in<br />

time and varies across geographical regi<strong>on</strong>s. A country’s total water demand<br />

depends <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> different inter-linked sectoral water uses, most of which relate<br />

directly to issues of ec<strong>on</strong>omic growth, welfare, human and animal health,<br />

as well as envir<strong>on</strong>mental sustainability. This complexity implies a need <strong>for</strong><br />

both better analytical tools to analyze <strong>the</strong> structure of water management<br />

challenges and enhanced ef<strong>for</strong>ts to <strong>for</strong>mulate and implement integrated<br />

water management policies.<br />

Internati<strong>on</strong>al boundaries dividing hydrological watersheds complicate<br />

<strong>the</strong> task of river management even fur<strong>the</strong>r. Positive and negative externalities<br />

of water use often accrue asymmetrically <strong>on</strong> different sides of a border and<br />

may encourage ‘free riding’ behavior. The waters of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Nile</strong> have been a<br />

27

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Double</str<strong>on</strong>g>-<str<strong>on</strong>g>Edged</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Hydropolitics</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Nile</strong><br />

source of transboundary disputes <strong>for</strong> millennia of recorded history. Egypt’s<br />

total dependence <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> river flow as a source of freshwater has created fears<br />

of deprivati<strong>on</strong> since ancient times. However unsubstantiated c<strong>on</strong>cerns of<br />

upstream manipulati<strong>on</strong>s of <strong>the</strong> river flow have been in <strong>the</strong> past, modern<br />

hydro-engineering projects in <strong>the</strong> upstream of <strong>the</strong> river may dramatically<br />

alter <strong>the</strong> runoff regime of <strong>the</strong> river. Any unilaterally imposed reducti<strong>on</strong> of<br />

<strong>the</strong> downstream water flow is certain to strain <strong>the</strong> transboundary relati<strong>on</strong>s<br />

am<strong>on</strong>g <strong>the</strong> <strong>Nile</strong> Basin states.<br />

With ancient rivalries still echoing in <strong>the</strong> basin, <strong>the</strong> <strong>Nile</strong> states have<br />

decided to take a different path. For <strong>the</strong> first time in history, all ten basin<br />

countries (with Eritrea still as an observer) have engaged in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Nile</strong> Basin<br />

Initiative to jointly design <strong>the</strong> future utilizati<strong>on</strong> of <strong>the</strong>ir river. Under <strong>the</strong><br />

stated overall goal of poverty alleviati<strong>on</strong>, <strong>the</strong> World Bank and o<strong>the</strong>r d<strong>on</strong>or<br />

agencies are committed to invest substantially into what is hoped will become<br />

a showcase of river basin cooperati<strong>on</strong>.<br />

This <strong>the</strong>sis starts from <strong>the</strong> assumpti<strong>on</strong> that both <strong>the</strong> potential <strong>for</strong> c<strong>on</strong>flict<br />

and <strong>the</strong> recent shift towards cooperati<strong>on</strong> in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Nile</strong> Basin are partly rooted in<br />

<strong>the</strong> domestic processes of water policy making. Specific mechanisms linking<br />

<strong>the</strong> domestic and internati<strong>on</strong>al levels of water governance are addressed<br />

through <strong>the</strong> lens of a two-level game framework. Implicati<strong>on</strong>s are drawn<br />

with regard to both <strong>the</strong> chances of reaching a transboundary agreement <strong>on</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>Nile</strong> and <strong>the</strong> likely focus of cooperative approaches.<br />

This introductory chapter sets <strong>the</strong> stage <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> presentati<strong>on</strong> and discussi<strong>on</strong><br />

of empirical results. It first specifies <strong>the</strong> research questi<strong>on</strong> and <strong>the</strong><br />

research objectives. Sec<strong>on</strong>d, <strong>the</strong> focus of <strong>the</strong> study is positi<strong>on</strong>ed in <strong>the</strong> c<strong>on</strong>text<br />

of <strong>the</strong> scientific discourses regarding <strong>the</strong> analysis of <strong>for</strong>eign policy decisi<strong>on</strong>s<br />

and ‘water c<strong>on</strong>flicts’. Then, <strong>the</strong> overall c<strong>on</strong>ceptual framework is outlined, and<br />

an overview of <strong>the</strong> methodological approach is presented. The delimitati<strong>on</strong>s<br />

of <strong>the</strong> research focus are specified. The chapter ends with an outline of <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong>sis document.<br />

C<strong>on</strong>ceptual and methodological issues also are addressed in <strong>the</strong> introductory<br />

secti<strong>on</strong>s of Chapters 3 to 7. The purpose of <strong>the</strong> introductory chapter<br />

is to present an overarching perspective <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> scope of this study, and to<br />

highlight a few c<strong>on</strong>ceptual and <strong>the</strong>matic aspects in a broader c<strong>on</strong>text.<br />

28

Introducti<strong>on</strong><br />

1.1 Research questi<strong>on</strong>s and objectives<br />

of <strong>the</strong> study<br />

The present <strong>the</strong>sis builds <strong>on</strong> earlier studies investigating <strong>the</strong> driving <strong>for</strong>ces<br />

behind c<strong>on</strong>flicts and cooperati<strong>on</strong> regarding issues of water allocati<strong>on</strong> and<br />

utilizati<strong>on</strong> in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Nile</strong> Basin. In most of <strong>the</strong>se studies, <strong>the</strong> behavior of <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Nile</strong> states and <strong>the</strong> potential <strong>for</strong> c<strong>on</strong>flict and cooperati<strong>on</strong> is explained with<br />

reference to <strong>the</strong> <strong>Nile</strong> states’ ‘nati<strong>on</strong>al interests’ and <strong>the</strong>ir relative military,<br />

ec<strong>on</strong>omic, and diplomatic power in <strong>the</strong> broader geopolitical c<strong>on</strong>text. Such<br />

systemic approaches, however, can <strong>on</strong>ly partly explain and predict <strong>the</strong> shifts<br />

between c<strong>on</strong>flictive and cooperative developments, or <strong>the</strong> specific areas of<br />

progress and deadlock in <strong>the</strong> transboundary negotiati<strong>on</strong>s.<br />

This <strong>the</strong>sis takes an explicit look at domestic processes of water policy<br />

making and instituti<strong>on</strong>al factors that influence <strong>the</strong> nati<strong>on</strong>al governments’<br />

priorities and thus c<strong>on</strong>stitute <strong>the</strong> ‘nati<strong>on</strong>al interests’ brought <strong>for</strong>ward in<br />

<strong>the</strong> transboundary negotiati<strong>on</strong>s. It is assumed that dynamic inter-linkages<br />

between <strong>the</strong> domestic policy processes and <strong>the</strong> internati<strong>on</strong>al negotiati<strong>on</strong>s<br />

determine <strong>the</strong> course of transboundary cooperati<strong>on</strong> and <strong>the</strong> specific outcomes<br />

in terms of policy re<strong>for</strong>ms and infrastructure development <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> ground.<br />

The analysis of domestic water policy processes can thus be expected to yield<br />

a refined understanding of <strong>the</strong> challenges and opportunities that characterize<br />

cooperati<strong>on</strong> initiatives in internati<strong>on</strong>al river basins. Accordingly, <strong>the</strong> main<br />

research questi<strong>on</strong>s addressed in this <strong>the</strong>sis are specified as follows.<br />

• What characteristics of domestic water policy processes influence<br />

<strong>the</strong> negotiati<strong>on</strong>s aiming at a transboundary agreement in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Nile</strong><br />

Basin?<br />

• What particular bias in <strong>the</strong> design of cooperative agreements results<br />

from specific domestic patterns of water policy making?<br />

• What are <strong>the</strong> specific mechanisms linking domestic processes of<br />

water policy making and <strong>the</strong> outcomes of transboundary negotiati<strong>on</strong>s<br />

over cooperative river management frameworks?<br />

29

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Double</str<strong>on</strong>g>-<str<strong>on</strong>g>Edged</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Hydropolitics</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Nile</strong><br />

The goal of this <strong>the</strong>sis is to add a complementary perspective to <strong>the</strong> prevalent<br />

c<strong>on</strong>ceptualizati<strong>on</strong> of riparian states as unitary actors in transboundary<br />

negotiati<strong>on</strong>s. The <strong>the</strong>sis does not questi<strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> merits of systemic approaches<br />

to <strong>the</strong> descripti<strong>on</strong> of transboundary river c<strong>on</strong>flict and cooperati<strong>on</strong>. Ra<strong>the</strong>r,<br />

it attempts to broaden <strong>the</strong> scope of explanatory variables and adds a complementary<br />

analytical dimensi<strong>on</strong>. The <strong>the</strong>sis thus aims to fur<strong>the</strong>r explore<br />

<strong>the</strong> general asserti<strong>on</strong> that ‘domestic politics and instituti<strong>on</strong>s matter’. More<br />

specifically, <strong>the</strong> following objectives are pursued.<br />

• First, <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>sis aims to create a better understanding of <strong>the</strong> specific<br />

linkages between domestic and internati<strong>on</strong>al water governance<br />

through <strong>the</strong> systematic – yet qualitative – applicati<strong>on</strong> of a<br />

two-level game framework. The resulting insights are expected to<br />

explain in part – and qualitatively predict – <strong>the</strong> course of <strong>the</strong> negotiati<strong>on</strong><br />

process in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Nile</strong> Basin and <strong>the</strong> c<strong>on</strong>crete cooperative<br />

projects <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> ground.<br />

• Sec<strong>on</strong>d, <strong>the</strong> study aims to test a specific analytical framework to<br />

describe domestic processes of water policy making in relati<strong>on</strong> to<br />

internati<strong>on</strong>al c<strong>on</strong>flict and cooperati<strong>on</strong>. In c<strong>on</strong>trast to earlier – and<br />

often anecdotal – descripti<strong>on</strong>s of domestic factors affecting transboundary<br />

cooperati<strong>on</strong>, <strong>the</strong> analytical focus of this study lies <strong>on</strong><br />

present structures ra<strong>the</strong>r than past events. The approach adopted<br />

in this project invites discussi<strong>on</strong>, modificati<strong>on</strong>s, and fur<strong>the</strong>r refinement.<br />

• Third, <strong>the</strong> findings from this <strong>the</strong>sis are expected to help researchers,<br />

but also water professi<strong>on</strong>als and decisi<strong>on</strong>-makers in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Nile</strong><br />

Basin and o<strong>the</strong>r regi<strong>on</strong>s, to design effective strategies that explicitly<br />

address <strong>the</strong> trade-offs between domestic and transboundary<br />

water development and management opti<strong>on</strong>s.<br />

30

Introducti<strong>on</strong><br />

The analytical perspective <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> interface between domestic and internati<strong>on</strong>al<br />

water governance can also serve as an entry point <strong>for</strong> a reassessment of<br />

certain ‘dogmas’ underpinning c<strong>on</strong>temporary water management paradigms.<br />

In particular, <strong>the</strong> results of this <strong>the</strong>sis shed a new light <strong>on</strong> – though <strong>the</strong>y do<br />

not necessarily reject – <strong>the</strong> assumpti<strong>on</strong>s that ‘transboundary cooperati<strong>on</strong><br />

is desirable in any case’ (see Bernauer 2002 <strong>for</strong> a critical view), ‘Integrated<br />

Water Resources Management produces best outcomes’ (see Allan 2003;<br />

Biswas 2004; Swatuk 2005 <strong>for</strong> differentiated analyses), and ‘participati<strong>on</strong><br />

and decentralizati<strong>on</strong> leads to more efficient water utilizati<strong>on</strong>’ (see Steelman<br />

and Ascher 1997; Milich and Varady 1999; Mostert 2003; Delli Priscoli 2004;<br />

Poolman and Van De Giesen 2006; Warner 2006).<br />

1.2 The discursive and analytical c<strong>on</strong>text:<br />

What c<strong>on</strong>flict? And how to analyze it?<br />

This secti<strong>on</strong> embeds <strong>the</strong> topic of <strong>the</strong> study in <strong>the</strong> broader c<strong>on</strong>text of two<br />

relevant academic discourses, and reviews <strong>the</strong> literature <strong>on</strong> transboundary<br />

river c<strong>on</strong>flicts. It prepares <strong>the</strong> ground <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> c<strong>on</strong>ceptual framework presented<br />

in Secti<strong>on</strong> 1.4. First, <strong>the</strong> <strong>on</strong>going debate am<strong>on</strong>g scholars of political<br />

sciences <strong>on</strong> how to best explain <strong>for</strong>eign policy behavior of states is addressed.<br />

Approaches rooted in Internati<strong>on</strong>al Relati<strong>on</strong>s <strong>the</strong>ories and Public<br />

Policy Analysis frameworks are discussed with a particular focus <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

potential integrati<strong>on</strong> of <strong>the</strong> two c<strong>on</strong>ceptual streams (Figure 1.1, right side;<br />

see also Chapters 3 and 7). Sec<strong>on</strong>d, <strong>the</strong> challenge of water allocati<strong>on</strong> and<br />

development in transboundary river basins is reviewed through <strong>the</strong> lens of<br />

evolving c<strong>on</strong>ceptual approaches to <strong>the</strong> issues of ‘water c<strong>on</strong>flict’ and ‘water<br />

management’ (Figure 1.1, left side; see also Chapter 3).<br />

31

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Double</str<strong>on</strong>g>-<str<strong>on</strong>g>Edged</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Hydropolitics</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Nile</strong><br />

Transboundary rivers in<br />

different perspectives<br />

Analytical perspectives <strong>on</strong><br />

<strong>for</strong>eign policy making<br />

Water C<strong>on</strong>flict<br />

Water Management<br />

Integrati<strong>on</strong> of<br />

internat<strong>on</strong>al and<br />

domestic water<br />

policy making<br />

Internati<strong>on</strong>al Relati<strong>on</strong>s<br />

Public Policy Analysis<br />

Figure 1.1: C<strong>on</strong>verging analytical perspectives <strong>on</strong> transboundary river management<br />

Systemic and domestic-level explanati<strong>on</strong>s of<br />

<strong>for</strong>eign policy behavior<br />

According to Kenneth Waltz’s (1979) seminal distincti<strong>on</strong>, explanati<strong>on</strong>s of a<br />

state’s behavior vis-à-vis o<strong>the</strong>r states are typically rooted in <strong>on</strong>e of <strong>the</strong> following<br />