Dr - LRS Institute of Tuberculosis & Respiratory Diseases

Dr - LRS Institute of Tuberculosis & Respiratory Diseases Dr - LRS Institute of Tuberculosis & Respiratory Diseases

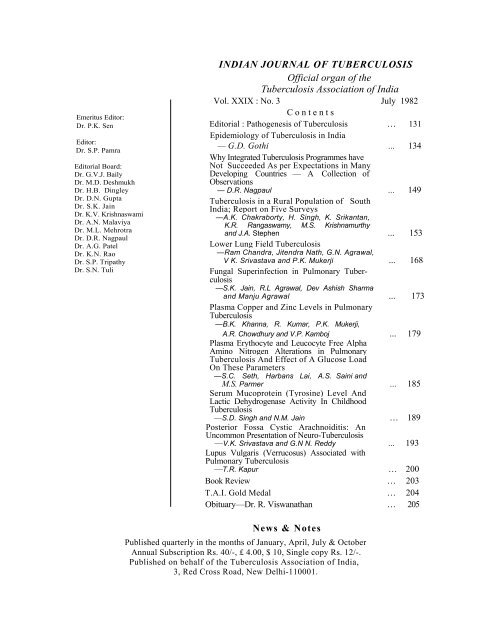

Emeritus Editor: Dr. P.K. Sen Editor: Dr. S.P. Pamra Editorial Board: Dr. G.V.J. Baily Dr. M.D. Deshmukh Dr. H.B. Dingley Dr. D.N. Gupta Dr. S.K. Jain Dr. K.V. Krishnaswami Dr. A.N. Malaviya Dr. M.L. Mehrotra Dr. D.R. Nagpaul Dr. A.G. Patel Dr. K.N. Rao Dr. S.P. Tripathy Dr. S.N. Tuli INDIAN JOURNAL OF TUBERCULOSIS Official organ of the Tuberculosis Association of India Vol. XXIX : No. 3 July 1982 Contents Editorial : Pathogenesis of Tuberculosis … 131 Epidemiology of Tuberculosis in India — G.D. Gothi ... 134 Why Integrated Tuberculosis Programmes have Not Succeeded As per Expectations in Many Developing Countries — A Collection of Observations — D.R. Nagpaul ... 149 Tuberculosis in a Rural Population of South India; Report on Five Surveys —A.K. Chakraborty, H. Singh, K. Srikantan, K.R. Rangaswamy, M.S. Krishnamurthy and J.A. Stephen ... 153 Lower Lung Field Tuberculosis —Ram Chandra, Jitendra Nath, G.N. Agrawal, V K. Srivastava and P.K. Mukerji ... 168 Fungal Superinfection in Pulmonary Tuberculosis —S.K. Jain, R.L Agrawal, Dev Ashish Sharma and Manju Agrawal ... 173 Plasma Copper and Zinc Levels in Pulmonary Tuberculosis —B.K. Khanna, R. Kumar, P.K. Mukerji, A.R. Chowdhury and V.P. Kamboj ... 179 Plasma Erythocyte and Leucocyte Free Alpha Amino Nitrogen Alterations in Pulmonary Tuberculosis And Effect of A Glucose Load On These Parameters —S.C. Seth, Harbans Lai, A.S. Saini and M.S. Parmer ... 185 Serum Mucoprotein (Tyrosine) Level And Lactic Dehydrogenase Activity In Childhood Tuberculosis —S.D. Singh and N.M. Jain … 189 Posterior Fossa Cystic Arachnoiditis: An Uncommon Presentation of Neuro-Tuberculosis —V.K. Srivastava and G.N N. Reddy ... 193 Lupus Vulgaris (Verrucosus) Associated with Pulmonary Tuberculosis —T.R. Kapur … 200 Book Review … 203 T.A.I. Gold Medal … 204 Obituary—Dr. R. Viswanathan … 205 News & Notes Published quarterly in the months of January, April, July & October Annual Subscription Rs. 40/-, £ 4.00, $ 10, Single copy Rs. 12/-. Published on behalf of the Tuberculosis Association of India, 3, Red Cross Road, New Delhi-110001.

- Page 2 and 3: The Indian Journal of Tuberculosis

- Page 4 and 5: The unsolved problems in pathogenes

- Page 6 and 7: EPIDEMIOLOGY OF TUBERCULOSIS IN IND

- Page 8 and 9: EPIDEMIOLOGY OF TUBERCULOSIS IN IND

- Page 10 and 11: EPIDEMIOLOGY OF TUBERCULOSIS IN IND

- Page 12 and 13: EPIDEMIOLOGY OF TUBERCULOSIS IN IND

- Page 14 and 15: EPIDEMIOLOGY OF TUBERCULOSIS IN IND

- Page 16 and 17: EPIDEMIOLOGY OF TUBERCULOSIS IN IND

- Page 18 and 19: EPIDEMIOLOGY OF TUBERCULOSIS IN IND

- Page 20 and 21: WHY INTEGRATED TUBERCULOSIS PROGRAM

- Page 22 and 23: WHY INTEGRATED TUBERCULOSIS PROGRAM

- Page 24 and 25: TUBERCULOSIS IN A RURAL POPULATION

- Page 26 and 27: TUBERCULOSIS IN A RURAL POPULATION

- Page 28: TUBERCULOSIS IN A RURAL POPULATION

- Page 32 and 33: TUBERCULOSIS IN A RURAL POPULATION

- Page 34 and 35: TUBERCULOSIS IN A RURAL POPULATION

- Page 36 and 37: TUBERCULOSIS IN A RURAL POPULATION

- Page 38 and 39: TUBERCULOSIS IN A RURAL POPULATION

- Page 40 and 41: LOWER LUNG FIELD TUBERCULOSIS 169 T

- Page 42 and 43: TABIF IV Radiological nature of les

- Page 44 and 45: FUNGAL SUPERINFECTION IN PULMONARY

- Page 46 and 47: FUNGAL SUPERINFECTION IN PULMONARY

- Page 48 and 49: FUNGAL SUPERINFECTION IN PULMONARY

- Page 50 and 51: PLASMA COPPER AND ZINC LEVELS IN PU

Emeritus Editor:<br />

<strong>Dr</strong>. P.K. Sen<br />

Editor:<br />

<strong>Dr</strong>. S.P. Pamra<br />

Editorial Board:<br />

<strong>Dr</strong>. G.V.J. Baily<br />

<strong>Dr</strong>. M.D. Deshmukh<br />

<strong>Dr</strong>. H.B. Dingley<br />

<strong>Dr</strong>. D.N. Gupta<br />

<strong>Dr</strong>. S.K. Jain<br />

<strong>Dr</strong>. K.V. Krishnaswami<br />

<strong>Dr</strong>. A.N. Malaviya<br />

<strong>Dr</strong>. M.L. Mehrotra<br />

<strong>Dr</strong>. D.R. Nagpaul<br />

<strong>Dr</strong>. A.G. Patel<br />

<strong>Dr</strong>. K.N. Rao<br />

<strong>Dr</strong>. S.P. Tripathy<br />

<strong>Dr</strong>. S.N. Tuli<br />

INDIAN JOURNAL OF TUBERCULOSIS<br />

Official organ <strong>of</strong> the<br />

<strong>Tuberculosis</strong> Association <strong>of</strong> India<br />

Vol. XXIX : No. 3 July 1982<br />

Contents<br />

Editorial : Pathogenesis <strong>of</strong> <strong>Tuberculosis</strong> … 131<br />

Epidemiology <strong>of</strong> <strong>Tuberculosis</strong> in India<br />

— G.D. Gothi ... 134<br />

Why Integrated <strong>Tuberculosis</strong> Programmes have<br />

Not Succeeded As per Expectations in Many<br />

Developing Countries — A Collection <strong>of</strong><br />

Observations<br />

— D.R. Nagpaul ... 149<br />

<strong>Tuberculosis</strong> in a Rural Population <strong>of</strong> South<br />

India; Report on Five Surveys<br />

—A.K. Chakraborty, H. Singh, K. Srikantan,<br />

K.R. Rangaswamy, M.S. Krishnamurthy<br />

and J.A. Stephen ... 153<br />

Lower Lung Field <strong>Tuberculosis</strong><br />

—Ram Chandra, Jitendra Nath, G.N. Agrawal,<br />

V K. Srivastava and P.K. Mukerji ... 168<br />

Fungal Superinfection in Pulmonary <strong>Tuberculosis</strong><br />

—S.K. Jain, R.L Agrawal, Dev Ashish Sharma<br />

and Manju Agrawal ... 173<br />

Plasma Copper and Zinc Levels in Pulmonary<br />

<strong>Tuberculosis</strong><br />

—B.K. Khanna, R. Kumar, P.K. Mukerji,<br />

A.R. Chowdhury and V.P. Kamboj ... 179<br />

Plasma Erythocyte and Leucocyte Free Alpha<br />

Amino Nitrogen Alterations in Pulmonary<br />

<strong>Tuberculosis</strong> And Effect <strong>of</strong> A Glucose Load<br />

On These Parameters<br />

—S.C. Seth, Harbans Lai, A.S. Saini and<br />

M.S. Parmer ... 185<br />

Serum Mucoprotein (Tyrosine) Level And<br />

Lactic Dehydrogenase Activity In Childhood<br />

<strong>Tuberculosis</strong><br />

—S.D. Singh and N.M. Jain … 189<br />

Posterior Fossa Cystic Arachnoiditis: An<br />

Uncommon Presentation <strong>of</strong> Neuro-<strong>Tuberculosis</strong><br />

—V.K. Srivastava and G.N N. Reddy ... 193<br />

Lupus Vulgaris (Verrucosus) Associated with<br />

Pulmonary <strong>Tuberculosis</strong><br />

—T.R. Kapur … 200<br />

Book Review … 203<br />

T.A.I. Gold Medal … 204<br />

Obituary—<strong>Dr</strong>. R. Viswanathan … 205<br />

News & Notes<br />

Published quarterly in the months <strong>of</strong> January, April, July & October<br />

Annual Subscription Rs. 40/-, £ 4.00, $ 10, Single copy Rs. 12/-.<br />

Published on behalf <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Tuberculosis</strong> Association <strong>of</strong> India,<br />

3, Red Cross Road, New Delhi-110001.

The<br />

Indian Journal <strong>of</strong> <strong>Tuberculosis</strong><br />

Vol. XXIX New Delhi, July 1982 No. 3<br />

PATHOGENESIS OF TUBERCULOSIS<br />

Robert Koch, in his famous dissertation announcing the discovery <strong>of</strong><br />

Tubercle Bacillus, said : “<strong>Tuberculosis</strong> has so far been habitually considered<br />

to be a manifestation <strong>of</strong> social misery, and it has been hoped that an improvement<br />

in the latter would reduce the disease. Measures specifically directed<br />

against tuberculosis are not known to preventive medicine. But in the future<br />

the fight against this terrible plague <strong>of</strong> mankind will deal no longer with an<br />

undetermined something, but with a tangible parasite, whose living conditions<br />

are, for the most part, known and can be investigated further”. Robert Koch’s<br />

pronouncement presaged a complete break from the past thinking and suggested<br />

an entirely new direction towards the control <strong>of</strong> tuberculosis. However,<br />

subsequent observations showed that even Robert Koch was not completely<br />

correct and his prophesy was the result <strong>of</strong> dogmatism and over-enthusiasm.<br />

Nageli and, subsequently, Opie and Ghon showed the presence <strong>of</strong> obsolete<br />

tuberculous lesions at autopsy in persons who had never suffered from tuberculosis<br />

in their life time. What is more important, many <strong>of</strong> these<br />

lesions contained viable tubercle bacilli. In other words, infection and<br />

mere presence <strong>of</strong> the aetiological agent in the tissues <strong>of</strong> the host is not<br />

sufficient per se to determine the development <strong>of</strong> manifest disease. A<br />

question naturally arises - why do only some <strong>of</strong> the enormous number<br />

<strong>of</strong> infected individuals develop the disease ? What are the factors which influence<br />

the development <strong>of</strong> disease, once infection has taken place ? Could it be<br />

that the very factors which Robert Koch decried are the factors which decide<br />

whether infection will go on to disease or not?<br />

The association <strong>of</strong> heredity and tuberculosis has been the subject <strong>of</strong> discussion<br />

for ages. We may not believe that one inherits tuberculosis but one<br />

also cannot deny that heredity can and does influence resistance against disease.<br />

Hill’s hypothesis <strong>of</strong> the speed <strong>of</strong> reaction is merely old wine served in a<br />

new bottle. It does not elucidate at all as to what makes the body react and<br />

what determines the speed <strong>of</strong> reaction.<br />

Knowledge regarding the mechanism through which the natural resistance<br />

operates and factors which augment or depress this is crucial but unfortunately<br />

still lacking. It has been hypothesised that the degree <strong>of</strong> natural resistance<br />

is dependent in part on ability to develop acquired resistance. But then,<br />

why does primary infection itself heal and the subsequent re-infection some<br />

times progress to disease inspite <strong>of</strong> the natural resistance being further<br />

augmented by acquired resistance ?<br />

Ind. J. Tub., Vol. XXIX, No, 3

132<br />

The increased susceptibility <strong>of</strong> household contacts <strong>of</strong> an open case <strong>of</strong><br />

tuberculosis is well-known and attributed to one or other <strong>of</strong> the three factors<br />

viz. intensity <strong>of</strong> exposure, heredity, adverse environmental factors. Seemingly<br />

valid arguments can be adduced for and against each <strong>of</strong> these factors.<br />

Inherent ability <strong>of</strong> an individual to maintain resistance at a high level may<br />

be, and very probably is, governed in part by heredity but the maintenance <strong>of</strong><br />

a satisfactory degree <strong>of</strong> resistance is also influenced by many environmental<br />

factors. The influence <strong>of</strong> ‘psyche’ is being increasingly incriminated in the<br />

problems <strong>of</strong> ‘soma’. But, whether a given unfavourable factor actually depresses<br />

the mechanism <strong>of</strong> natural resistance or whether the mechanism remains unaltered<br />

but conditions are introduced which thwart it or prevent it from functioning<br />

effectively is, <strong>of</strong> course, not known. Since many <strong>of</strong> these factors which influence<br />

the outcome <strong>of</strong> infection are intangible, the fate <strong>of</strong> the individual remains<br />

unpredictable.<br />

Mode <strong>of</strong> reinfection is another moot point in pathogenesis. It is common<br />

knowledge that most <strong>of</strong> the progressive pulmonary disease is not the<br />

direct result <strong>of</strong> primary infection but follows re-infection, sometimes many<br />

years after the primary infection. Is reinfection endogenous or exogenous ?<br />

Arguments for and against both have been many and fascinating. Consensus<br />

appears to be in favour <strong>of</strong> endogenous reinfection being more likely<br />

and more plausible though it cannot be proved that exogenous reinfection<br />

is not possible. This controversy is not merely an exercise in intellectual<br />

polemics without any practical implication. Prevention <strong>of</strong> tuberculosis does<br />

seem to be linked with this problem. If endogenous reinfection was the only<br />

mode, isolation <strong>of</strong> an open case from individuals already infected is meaningless.<br />

If on the other hand, exogenous reinfection is possible, then isolation<br />

from both infected and uninfected is imperative.<br />

Endogenous reinfection is also linked with the problem <strong>of</strong> dormant bacilli.<br />

What makes the bacilli dormant ? Our knowledge in respect <strong>of</strong> growth requirements<br />

<strong>of</strong> the bacillus and its metabolism is still limited. Is dormancy governed<br />

by some inherent and intrinsic character <strong>of</strong> the bacillus or is it in response<br />

to some altered state <strong>of</strong> the tissues in which the bacilli are lodged ? We are<br />

still ignorant about the mechanism which triggers dormancy and subsequent reanimation.<br />

A substance called “Hibernation Induction Trigger” has been<br />

isolated from the blood <strong>of</strong> hibernating animals. Could it that some such<br />

substance is involved in dormancy <strong>of</strong> the tubercle bacillus also ?<br />

The importance <strong>of</strong> the dormant bacillus is not merely because <strong>of</strong> its role<br />

in reinfection and relapse but also because <strong>of</strong> its influence on epidemiology.<br />

When tuberculosis started declining rapidly in the western countries, the high<br />

priests <strong>of</strong> epidemiology prophesied that eradication <strong>of</strong> tuberculosis was imminent.<br />

Their optimism was more wishful than rational. As long as there is but<br />

one human being in the world who has but one dormant bacillus inside his<br />

body, he can generate, at least theoretically, a new epidemic <strong>of</strong> tuberculosis<br />

even if the previous one had completely died out. This has been corroborated<br />

by a number <strong>of</strong> small localised epidemics that have occurred recently in developed<br />

countries where tuberculosis has declined tremendously.<br />

Ind. J. Tub., Vol. XXIX, No. 3

The unsolved problems in pathogenesis <strong>of</strong> tuberculosis are many and<br />

varied. Rich summarised the position admirably in 1951. What passed for<br />

knowledge about pathogenesis was more a matter <strong>of</strong> belief based on reasoning<br />

from analogy rather than a conviction based on valid statistical and scientific<br />

pro<strong>of</strong>. And there the matter rests even today!<br />

133<br />

Ind. J. Tub., Vol. XXIX, No. 3

REVIEW ARTICLE<br />

EPIDEMIOLOGY OF TUBERCULOSIS IN INDIA<br />

<strong>Tuberculosis</strong> is known to have existed in<br />

India since ancient times and has been mentioned<br />

in classical literature including Ayurvedic<br />

Samhitas. However, quantitative information<br />

about its epidemiology has become available<br />

only in the last half century. Unlike western<br />

countries, where a more or less efficient notification<br />

system has existed for a long time,<br />

India has been lacking in even approximate<br />

data about the prevalence and incidence <strong>of</strong><br />

tuberculous infection and disease as well as<br />

mortality rates. One <strong>of</strong> the earliest <strong>of</strong>ficial<br />

documents in which data regarding tuberculosis<br />

have been given is the Bhore Commission<br />

Report, 1946. The general impression at that<br />

time was that tuberculosis was mainly an urban<br />

problem and that younger persons, specially<br />

females, were more prone to it than others.<br />

Although the relevant facts regarding the<br />

present day epidemiology <strong>of</strong> tuberculosis in<br />

India have not yet been fully elucidated, a<br />

considerable amount <strong>of</strong> information, <strong>of</strong> varying<br />

degrees <strong>of</strong> reliability and accuracy, has accumulated<br />

during the course <strong>of</strong> the last 30 or 40<br />

years enabling us to see at least the outlines <strong>of</strong><br />

the problem and furnishing the basis for future<br />

action.<br />

As is well known, infection and disease are<br />

not synonymous in tuberculosis. We have, thus,<br />

two parameters to consider, both interdependent,<br />

even though the extent <strong>of</strong> interdependence<br />

is itself an enigma.<br />

Prevalence <strong>of</strong> tuberculous infection<br />

Prevalence <strong>of</strong> infection is measured by the<br />

proportion <strong>of</strong> tuberculin reactors in the total<br />

population at any point <strong>of</strong> time and is usually<br />

expressed as a percentage. However, in the<br />

absence <strong>of</strong> a well defined test, available information<br />

on this point is highly variable. Because<br />

<strong>of</strong> the use <strong>of</strong> different types <strong>of</strong> tuberculins,<br />

different dosages and methods <strong>of</strong> testing,<br />

considerable variations in the reading <strong>of</strong> reactions<br />

by different workers, imprecise knowledge<br />

about the exact size <strong>of</strong> tuberculin induration<br />

that should be regarded as evidence <strong>of</strong><br />

tubercular infection, the possibility <strong>of</strong> a boosting<br />

effect due to earlier tuberculin testing and the<br />

prevalence <strong>of</strong> non-specific tuberculin sensitivity<br />

in some areas, the interpretation <strong>of</strong> tuberculin<br />

G.D. GOTHI*<br />

test reactions is a highly complex job. In view<br />

<strong>of</strong> these limitations, it is not possible to compare<br />

infection rates reported from time to time by<br />

different workers from different areas. A review<br />

<strong>of</strong> literature reveals that, unaware <strong>of</strong> the limitations<br />

<strong>of</strong> the test, different workers have used<br />

different strengths and types <strong>of</strong> tuberculin and<br />

arbitrarily set critical values for separating<br />

tuberculin reactors and non-reactors.<br />

The earliest report on prevalence <strong>of</strong> infection<br />

in India is by Ukil (1930) who found 11%<br />

tuberculin reactors in the 0 to 4 age group and<br />

75% among persons aged 10 years or more in<br />

a survey carried out in areas <strong>of</strong> Bengal, Bihar,<br />

Assam and Madras. The observed rates were<br />

much higher -in the urban areas. Benjamin<br />

(1938-39), surveying a sample population in<br />

the rural and urban areas <strong>of</strong> Chittoor district<br />

and in Saidapet (in the suburbs <strong>of</strong> Madras),<br />

made similar observations although, contrary<br />

to the then current general impression, he<br />

concluded that villages were not free from tuberculous<br />

infection. Rist and Rose (1938) carried<br />

out a survey among Muslim girls in Ludhiana,<br />

Ilahi Baksh (1939) in the rural population <strong>of</strong><br />

Jullunder and Rao and Cochran (1943) repeated<br />

a tuberculin survey in Saidapet. All<br />

these reported a high prevalence <strong>of</strong> infection<br />

in towns, semi-urban areas and villages. High<br />

infection rates were also reported by Frimodt-<br />

Moller (1949) in Madanapalle town and surrounding<br />

rural areas.<br />

More extensive data regarding infection<br />

rates became available as a by-product <strong>of</strong> the<br />

mass BCG vaccination campaign undertaken<br />

by the Government <strong>of</strong> India. Analysis <strong>of</strong> data<br />

showed a high prevalence <strong>of</strong> infection even at<br />

the young age <strong>of</strong> 5 years in West Bengal,<br />

Bombay and Uttar Pradesh. The tuberculin<br />

reactor rates at this age in the three states were<br />

23.0%, 32.2% and 27.4% respectively for<br />

males and 21.5%, 32.2%’ and 22.8% for<br />

females. It was found that by the age <strong>of</strong> 10,<br />

more than half the males and over 45 % <strong>of</strong> the<br />

females had already been infected. In the hilly<br />

regions, half the population was infected by the<br />

age <strong>of</strong> 15 years as against the age <strong>of</strong> 10 years<br />

in the plains. Infection rates in the industrial<br />

towns were higher than elsewhere, 50% level<br />

<strong>of</strong> infection having been reached before the<br />

age <strong>of</strong> 10 years.<br />

*Director, New Delhi <strong>Tuberculosis</strong> Centre, Jawahar Lai Nehru Marg, New Delhi-110002.<br />

Ind. J. Tub., Vol. XXIX, No. 3

EPIDEMIOLOGY OF TUBERCULOSIS IN INDIA 135<br />

Several other studies carried out at the same<br />

time (Sikand and Raj Narain, 1952 in Faridabad<br />

township, Hertzberg, 1952 in Trivandrum city<br />

and Frimodt-Moller in Madanapalle town and<br />

surrounding villages) also revealed a very high<br />

rate <strong>of</strong> tuberculintzation. Frimodt-Moller (I960)<br />

carried out a large scale tuberculin survey<br />

among a population living within 10 miles<br />

radius <strong>of</strong> Madanapalle. Using 5 TU PPD<br />

(XIX, XX and XXI with a reaction <strong>of</strong> 10 mm<br />

or more taken as an evidence <strong>of</strong> infection),<br />

he found that at the ages <strong>of</strong> 10 years, 20 years<br />

and 30 years, the infection rates were 10%,<br />

21% and 31% respectively. Using 1 TU and<br />

considering an induration <strong>of</strong> 6 mm or more as<br />

an evidence <strong>of</strong> infection the rates at the same<br />

ages were slightly lower.<br />

Considering a reaction <strong>of</strong> 10 mm or more<br />

to 1 TU PPD RT 23 with tween 80 as positive,<br />

Raj Narain et al (1963) found an overall infection<br />

rate <strong>of</strong> 38.3% in a sample population<br />

<strong>of</strong> Tumkur district (42.8% among males and<br />

33.9% among females). Infection rates in the<br />

rural and semi-rural areas were 37.9% and<br />

43.9% respectively. The overall prevalence <strong>of</strong><br />

infection in 119 villages <strong>of</strong> Bangalore district<br />

(based on the same tuberculin and reaction<br />

as above) was found to be 30% (35% among<br />

males and 25% among females) (National<br />

<strong>Tuberculosis</strong> <strong>Institute</strong> (NTI), 1974). The infection<br />

rates for both sexes increased with<br />

age upto ‘45 to 54 years’ (66% to 72% for<br />

males, 47% to 50% for females). The rate <strong>of</strong><br />

increase in females, unlike males, slowed down<br />

after the age <strong>of</strong> 15 years. Repeated tuberculin<br />

testing <strong>of</strong> the same population at intervals <strong>of</strong><br />

1-1/2 years to 2 years did not show any change<br />

over a period <strong>of</strong> 5 years. In a recently conducted<br />

study in Chingleput district <strong>of</strong> Tamil Nadu,<br />

<strong>Tuberculosis</strong> Prevention Trial (TPT, 1980),<br />

using 3 TU <strong>of</strong> PPD-S and considering an<br />

induration <strong>of</strong> 12 mm or more as evidence <strong>of</strong><br />

infection, reported an overall prevalence rate<br />

<strong>of</strong> infection <strong>of</strong> 50% (males 54%; females 46%).<br />

Among males, the infection rate rose rapidly<br />

upto the age <strong>of</strong> 25 years (reaching 80 %) whereas<br />

in females the rise continued upto 35 years<br />

(reaching 70%). In both sexes the rate levelled<br />

<strong>of</strong>f after the peak had been reached. In the<br />

Kashmir valley, infection rates were found to<br />

be considerably lower than, say, in the south<br />

Indian states <strong>of</strong> Karnataka and Tamil Nadu.<br />

(Unpublished material 1980).<br />

In Tumkur survey, the prevalence rates <strong>of</strong><br />

infection in the age groups 0 to 4 years, 5 to 9<br />

years and 10 to 14 years were 2.7%, 5.5% &<br />

25.4% respectively (Raj Narain, 1963). Gothi<br />

et al (1979) found nearly the same rates among<br />

children and adolescents in the same population<br />

after 12 years.<br />

Udani (1968) reported a prevalence rate <strong>of</strong><br />

4.7% in the age group 0 to 6 years on the west<br />

coast. In the semi-urban areas <strong>of</strong> Delhi the<br />

rate was 4.6% (Dingley, 1979) in the age group<br />

0 to 4 years but among school children (5 to<br />

14 years) in the city, the figure was 40.7%<br />

(Singh, 1960). Figures for school children<br />

<strong>of</strong> Nagpur were reported as 24.4% by Majumdar<br />

(1960). At the age <strong>of</strong> 15 years, Benjamin<br />

(1951) found the lowest infection rates in<br />

Assam (51% among males and 36% among<br />

females) and the highest in U.P. (males 75%,<br />

females 74%). In the <strong>Tuberculosis</strong> Prevention<br />

Trial (1980), the rates for age groups 1 to 4<br />

years, 5 to 9 years and 10 to 14 years were<br />

4.9%, 7.9% and 16.5% respectively, males in<br />

general showing a higher prevalence than<br />

females. Krishnaswami (1978) reporting on the<br />

urban slums <strong>of</strong> Madras found a very high<br />

rate <strong>of</strong> infection for children below 5 years.<br />

In another congested urban areas <strong>of</strong> Madras,<br />

Narmada et al (1973) reported rate <strong>of</strong> 7.3%<br />

in the 0 to 4 years age group.<br />

Although data available from various<br />

sources are not strictly comparable, nevertheless,<br />

there are some common features viz. (i) infection<br />

rates increase with age and are higher in males<br />

than in females (ii) the difference can probably<br />

be explained by the fact that males in general<br />

lead a more active life and mix with people in<br />

a much wider circle, thus coming across more<br />

chances <strong>of</strong> acquiring infection, (iii) infection<br />

rates, in general, are more or less the same in<br />

urban and rural areas, although they are somewhat<br />

higher in congested urban areas and<br />

industrial towns.<br />

Incidence <strong>of</strong> infection<br />

The conventional method <strong>of</strong> estimating the<br />

incidence <strong>of</strong> infection is by repeated tuberculin<br />

testing <strong>of</strong> the population. Persons classified as<br />

non-reactors at an earlier tuberculin testing who<br />

become reactors at a subsequent testing can be<br />

considered to have acquired tuberculous infection<br />

in the intervening period and incidence<br />

<strong>of</strong> infection is calculated per annum by expressing<br />

the latter as a percentage <strong>of</strong> the former.<br />

Several attempts have been made, mostly in<br />

south Indian states, to estimate the incidence<br />

<strong>of</strong> infection.<br />

Bogen (1957) used age specific prevalence<br />

rates <strong>of</strong> infection for his estimate <strong>of</strong> 5.3 % per<br />

year for all ages. Using similar data, Frimodt-<br />

Moller (1960) estimated the annual incidence<br />

<strong>of</strong> infection as lying between 4.7% and 6.2%<br />

for different ages and Raj Narain et al (1963)<br />

between 0.9% to 2.4%. Partly these differences<br />

may be accounted for by different standards<br />

Ind. J. Tub., Vol. XXIX, No. 3

136 G.D. GOTHI<br />

adopted for judging tuberculin positivity.<br />

Frimodt-Moller (1960), however, also gave a<br />

different estimate <strong>of</strong> the incidence <strong>of</strong> infection<br />

(2%) per year by direct observation i.e. after<br />

repeated tuberculin testing at intervals <strong>of</strong> 2-1/2<br />

years. Narmada et al (1977) reported 3%<br />

annual incidence <strong>of</strong> infection in 0-12 years age<br />

group.<br />

Serious doubts about the validity <strong>of</strong> the<br />

studies mentioned above arose as a result <strong>of</strong><br />

the findings <strong>of</strong> Raj Narain et al (1965) wherein<br />

they proved that a previous tuberculin test<br />

boosts the induration <strong>of</strong> any subsequent tuberculin<br />

test reaction. Also, it was found that the<br />

prevalence <strong>of</strong> non-specific sensitivity (Frimodt-<br />

Moller 1960; Raj Narain et al 1965-72; Chakraborty<br />

et al 1976) may interfere with the<br />

estimation <strong>of</strong> the incidence <strong>of</strong> infection. Raj<br />

Narain (1966) found a method for overcoming<br />

this difficulty and suggested a new approach for<br />

identifying the newly infected persons. By<br />

this method Raj Narain (1965) and Gothi et al<br />

(1972) estimated the incidence in the age group<br />

‘0 to 4’ years at 0.9 % per year and for the age<br />

groups ‘5-9’ years and ‘10-14’ years, 1.4% and<br />

2.1% respectively. National <strong>Tuberculosis</strong> <strong>Institute</strong><br />

(NT1-1974), using the same method reported<br />

that the average annual incidence <strong>of</strong><br />

infection for all ages was 1 %, that for the age<br />

group ‘0 to 4’ years being 0.8%. The incidence<br />

rates increased with age. For the age group<br />

‘35 years and above’ the figure varied from<br />

1.3% to 3.16% during three periods. Adopting<br />

the same method <strong>of</strong> calculation, TPT (1980)<br />

found a much higher annual incidence <strong>of</strong> infection,<br />

3%, 4% and 6% per year for the age<br />

groups ‘1 to 4’ years, ‘5 to 9’ years and ‘10<br />

to 14’ years, respectively. A plausible reason<br />

for such differences could be the considerable<br />

difference in the prevalence <strong>of</strong> bacillary disease<br />

in the two areas (4 per 1000 in the NTI study<br />

area and 11 per 1000 in the TPT area).<br />

<strong>Tuberculosis</strong> Morbidity<br />

Two principal indices are generally used<br />

to measure tuberculosis morbidity in any<br />

community, the prevalence <strong>of</strong> active disease and<br />

fresh incidence <strong>of</strong> disease among previously<br />

healthy persons. As in the case <strong>of</strong> studies<br />

relating to infection, there is a considerable<br />

paucity <strong>of</strong> data in respect <strong>of</strong> tuberculosis morbidity<br />

in India and in practically all developing<br />

countries. In western countries, tuberculosis<br />

has been a notifiable disease for a long time<br />

and the system works fairly efficiently. As such,<br />

some data (more or less precise, depending on<br />

the efficiency <strong>of</strong> the notification system in any<br />

particular country) relating to the prevalence<br />

and incidence <strong>of</strong> disease have been available<br />

Ind. J. Tub., Vol. XXIX, No. 3<br />

for a long time, even though these statistics are<br />

based only on ‘known’ cases. Although these<br />

data do not take into account the undetected,<br />

asymptomatic cases <strong>of</strong> tuberculosis, nevertheless<br />

they provide very valuable information<br />

about TB morbidity and trends in the community.<br />

For several decades, these were the<br />

only statistics available even in the western<br />

countries for evaluating the tuberculosis problem.<br />

In India, on the other hand, practically no<br />

reliable data, were available till the early fifties<br />

about the prevalence or incidence <strong>of</strong> tuberculosis.<br />

One <strong>of</strong> the earliest estimates made by<br />

Benjamin (1945), based on findings <strong>of</strong> a small<br />

scale survey in the suburbs <strong>of</strong> Madras city,<br />

and certain other observations, placed the total<br />

number <strong>of</strong> active TB cases in the country at<br />

about 25 lakhs, the estimated total TB mortality<br />

in a year being <strong>of</strong> the order <strong>of</strong> 5 lakhs (Bhore<br />

Commission Report, 1946).<br />

It was only in the early 1950s that, with the<br />

availability <strong>of</strong> mobile mass miniature radiographic<br />

facilities, one acquired the means for<br />

evaluating the tuberculosis problem by carrying<br />

out surveys in various groups. In the last 30<br />

years, a number <strong>of</strong> surveys (some in representative<br />

community groups and others in selected<br />

groups) have been carried out and although<br />

data available are still not sufficient, considering<br />

the size <strong>of</strong> the country, they provide a<br />

useful basis for planning tuberculosis control<br />

strategies.<br />

It must not be presumed, however, that<br />

with the availability <strong>of</strong> mass radiography and<br />

sputum examination (the main tools employed<br />

for tuberculosis morbidity surveys) all problems<br />

relating to estimation <strong>of</strong> TB morbidity have<br />

been solved. Both chest radiography and<br />

bacteriological examination have their limitations.<br />

In addition, the diagnostic problems <strong>of</strong><br />

tuberculosis are so complicated that no two<br />

studies are, strictly speaking, comparable and<br />

for that reason it is not possible to make any<br />

general statement about the country as a whole<br />

by taking into account the various studies<br />

carried out in different regions. It would be<br />

useful at the outset to consider all these limitations<br />

to serve as caveat before drawing any<br />

rash and possibly unjustified conclusions from<br />

the various studies carried out at different<br />

centres.<br />

The first difficulty arises from limitations <strong>of</strong><br />

the two principal diagnostic tools viz. radiography<br />

and bacteriological examination. Radiological<br />

assessment <strong>of</strong> chest shadows, as is well<br />

known, is highly subjective and is influenced

EPIDEMIOLOGY OF TUBERCULOSIS IN INDIA 137<br />

by the competence <strong>of</strong> the x-ray reader and his<br />

impression about the prevalence <strong>of</strong> other<br />

pulmonary diseases in the region concerned.<br />

A number <strong>of</strong> studies have brought out the<br />

extent <strong>of</strong> ‘reader variations’, both intra-individual<br />

and inter-individual, in intrepretation<br />

<strong>of</strong> chest x-rays (Yerushalmy et al 1950, Sikand<br />

et al 1962, Raj Narain et al 1962, Karan 1962,<br />

Gothi et al 1974). An additional difficulty in<br />

large scale surveys is that usually it is not<br />

possible to have anything more than a single<br />

miniature film to decide the aetiology and<br />

activity <strong>of</strong> abnormal shadows. This is <strong>of</strong>ten<br />

not an adequate basis on which to arrive at a<br />

conclusive diagnosis. A number <strong>of</strong> procedures<br />

for radiological assessment <strong>of</strong> miniature films<br />

have been evaluated empirically and the system<br />

commonly followed in the better planned<br />

studies, nowadays, is to have two independent<br />

assessments by two readers with a third ‘umpire’<br />

reading by another reader to settle the<br />

differences between the first two. It has been<br />

found after experimentation that this procedure<br />

is fairly adequate for minimizing errors <strong>of</strong><br />

both under-reading and over-reading.<br />

In well planned surveys, all persons with<br />

abnormal chest x-rays are subjected to a set <strong>of</strong><br />

bacteriological examinations. The fact that<br />

intensity <strong>of</strong> such bacteriological examinations<br />

varies from place to place and from time to<br />

time is an additional factor which makes it<br />

difficult to compare or combine results <strong>of</strong><br />

studies carried out at different centres. Many<br />

centres lacking culture facilities have perforce no<br />

option but to depend entirely on direct<br />

microscopy <strong>of</strong> sputum. Some carry out both<br />

direct smear and culture examination <strong>of</strong> a<br />

single specimen. Some others are in the fortunate<br />

position <strong>of</strong> being able to examine more than one<br />

specimen at different intervals <strong>of</strong> time and<br />

sometimes even repeat the chest x-ray, if<br />

indicated. It is natural in this situation that the<br />

final assessments would lack comparability. An<br />

idea <strong>of</strong> how much difference this would make<br />

can be had from the study <strong>of</strong> Chandra-sekhar et<br />

al (1970) wherein it was shown that if 4<br />

bacteriological specimens were examined in a<br />

survey, nearly 25% <strong>of</strong> the bacillary cases were<br />

added by the third and fourth specimens. Nair et al<br />

(19761 have also shown that the rate <strong>of</strong> bacillary<br />

disease increased by an additional , 39 % if eight<br />

specimens were examined instead <strong>of</strong> two. It is<br />

thus obvious that unless suitable ‘corrections’<br />

are made, data obtained from one study would<br />

not be directly comparable with any other study<br />

with a different intensity <strong>of</strong> bacteriological<br />

examination.<br />

Further problems arise because <strong>of</strong> the fact<br />

that there is no commonly agreed definition <strong>of</strong><br />

pulmonary tuberculosis (Raj Narain, 1968).<br />

Except for bacteriologically proved cases, there<br />

is always an element <strong>of</strong> doubt about cases<br />

adjudged tuberculous merely on radiological<br />

basis. To overcome this difficulty and to provide<br />

a sort <strong>of</strong> lowest common denominator, the<br />

WHO Expert Committee in its VIIIth Report<br />

(1964) recommended that only sputum positive<br />

patients should be considered as ‘cases’ <strong>of</strong> tuberculosis<br />

and all others labelled as ‘suspects’.<br />

This definition too is not, however, free from<br />

faults. Bacteriological diagnosis, although highly<br />

specific, is not sensitive enough and it is well<br />

known that a large proportion <strong>of</strong> tuberculosis<br />

patients with minimal disease are bacteriologically<br />

negative to start with. This, besides the<br />

difficulties enumerated earlier, detracts somewhat<br />

from evaluation <strong>of</strong> tuberculosis problem<br />

based only on bacteriological confirmation <strong>of</strong><br />

diagnosis.<br />

So far as the prevalence rates are concerned, a<br />

certain comparability can be achieved between<br />

various studies by comparing the rate <strong>of</strong> bacillary<br />

disease. Where estimation <strong>of</strong> incidence<br />

rates among previously healthy persons is<br />

concerned, a further difficulty arises. Since<br />

there is no agreed definition <strong>of</strong> a tuberculosis<br />

case, it follows that there is no agreed definition<br />

<strong>of</strong> a non-case. In a longitudinal study, in which<br />

prevalence <strong>of</strong> only bacteriologically confirmed<br />

disease at the first survey has been calculated,<br />

the remaining population including bacteriologically<br />

unproved but radiologically active<br />

patients, persons with inactive disease and<br />

those with clear chest x-ray would form the<br />

denominator (population at risk) for calculation<br />

to further incidence. In another study in which<br />

prevalence is calculated on the basis <strong>of</strong> radiological<br />

and/or bacteriological evidence, the<br />

people at risk which would form the denominator<br />

for calculation <strong>of</strong> incidence would be<br />

only persons with a clear chest x-ray. Since the<br />

attack rate in the two types <strong>of</strong> ‘non-cases’ in<br />

the two studies is likely to be different, it is<br />

obvious that incidence rates would also not be<br />

comparable.<br />

Inspite <strong>of</strong> the difficulties and handicaps<br />

mentioned above, surveys based on examination<br />

by various procedures and techniques<br />

have contributed valuable fundamental knowledge<br />

about tuberculosis morbidity in the<br />

country.<br />

Prevalence <strong>of</strong> disease<br />

Prevalence is defined as the number <strong>of</strong><br />

patients at a given point <strong>of</strong> time and is expressed<br />

either in absolute numbers or as a<br />

rate per 1,000 or per 100,000 <strong>of</strong> population.<br />

Ind. J. Tub., Vol. XXIX, No. 3

138 G.D. GOTHI<br />

Prior to 1950 only a few small scale surveys<br />

were carried out in some parts <strong>of</strong> the country<br />

to ascertain prevalence <strong>of</strong> tuberculosis. Benjamin<br />

et al (1939) surveyed a population <strong>of</strong> 3,309 in<br />

Saidapet, a suburb <strong>of</strong> Madras. Persons having<br />

a strongly positive tuberculin test reaction or<br />

having suspicious symptoms were physically<br />

examined and 241 out <strong>of</strong> these were picked up<br />

for x-ray. The disease prevalence thus estimated<br />

was 2.3%. Another survey (Lai et al, 1943)<br />

carried out in an urban population at Serampore<br />

in Bengal showed a morbidity prevalence <strong>of</strong><br />

7% <strong>of</strong> which sputum positive disease accounted<br />

for 3%. In both these surveys, because <strong>of</strong><br />

meagre x-ray facilities, only a small adult<br />

population was examined. It is easy to see that<br />

the figures do not reflect the correct tuberculosis<br />

prevalence even for the limited areas covered.<br />

Mobile miniature radiography was first<br />

used by Aspin in 1945 to survey Gurkha recruits<br />

for the Army and labour units. All those<br />

examined were aged 18 years or more. In<br />

Gurkha recruits the prevalence <strong>of</strong> tuberculosis<br />

was found to be 1 % and among labour recruits<br />

3.4%. Obviously, these figures cannot be considered<br />

representative. Besides the fact that<br />

they were all adults, recruits presenting themselves<br />

for appointment in the Army were<br />

expected to be healthier than the community<br />

to which they belonged. In 1947, Frimodt-<br />

Moller surveyed a population <strong>of</strong> 10,000 in<br />

Madanapalle town and reported a prevalence<br />

<strong>of</strong> 0.7% bacillary disease. This figure was<br />

confirmed by a series <strong>of</strong> 5 longitudinal surveys<br />

carried out by Frimodt-Moller in the same area<br />

between 1950 and 1955 in which the population<br />

studied was about 60,000. In 1951. the New<br />

Delhi TB Centre surveyed Faridabad township<br />

(housing displaced population) and found<br />

active disease prevalence rate <strong>of</strong> 13.6 per 1000<br />

among persons aged 5 years or more (Sikand<br />

and Raj Narain, 1952). Other surveys carried<br />

out about the same time in selected groups at<br />

Madras and Trivandrum were reported by<br />

Phillips (1952) and Hertzberg (1952). These<br />

were the best available data on the subject till<br />

about 1954-55. On the basis <strong>of</strong> personal impressions<br />

and limited data obtained from<br />

surveys, the general belief about this .time was<br />

that tuberculosis was commoner among younger<br />

people rather than the aged, females rather than<br />

males, and cities and towns rather than villages.<br />

Studies carried out during last 30 years have<br />

disproved these beliefs. The first doubt about<br />

these hypotheses arose from the data obtained<br />

as a by-product <strong>of</strong> the mass BCG programme<br />

carried out throughout the country starting in<br />

1951. Tuberculin testing <strong>of</strong> the rural population<br />

revealed an unexpectedly high prevalence <strong>of</strong><br />

tuberculous infection in the villages (Benjamin,<br />

1951) suggesting the probability <strong>of</strong> a substantially<br />

high prevalence <strong>of</strong> tuberculosis in the<br />

rural areas as well.<br />

To verify this impression, the Indian Council<br />

<strong>of</strong> Medical Research (1959) organized a large<br />

scale Sample Survey to assess the tuberculosis<br />

situation in urban, semi-urban and rural areas<br />

in various parts <strong>of</strong> the country during 1955-57.<br />

The survey was carried out in 6 zones <strong>of</strong> the<br />

country and covered a sample <strong>of</strong> nearly 300,000<br />

persons aged 5 years or more. All persons<br />

included in the sample were <strong>of</strong>fered mass miniature<br />

radiography. Sputa <strong>of</strong> persons with<br />

abnormal chest shadows were examined by<br />

direct microscopy and by culture. The main<br />

findings <strong>of</strong> the survey were (i) the rate <strong>of</strong><br />

radiologically active pulmonary tuberculosis<br />

varied from 13.5 to 26.6 per 1,000 population<br />

in different zones and within each zone from<br />

cities to small towns and rural areas, (ii) the<br />

prevalence <strong>of</strong> bacillary disease varied from<br />

2.4 to 8.2 per 1,000 (iii) prevalence <strong>of</strong> disease<br />

in rural areas did not differ significantly from<br />

the urban areas, (iv) prevalence <strong>of</strong> disease<br />

showed a continuous rise with age in both<br />

sexes but for females there was a decline from<br />

the age <strong>of</strong> 45 years onwards. Nearly 2/3rd <strong>of</strong><br />

the total disease was in males. Villages accounted<br />

for nearly 80 % <strong>of</strong> the total cases (the same<br />

proportion as the rural population bore to the<br />

total population).<br />

Further information about prevalence rates<br />

is available from longitudinal studies carried<br />

out in Delhi, Bangalore, Madanapalle and<br />

Chingleput. The surveys in Delhi and Madanapalle<br />

(the former in an urban and the latter in<br />

a rural areas) confirmed the findings regarding<br />

prevalence rates obtained from the earlier ICMR<br />

survey. In the Delhi study, carried out in a<br />

congested old city area and covering a population<br />

<strong>of</strong> about 30,000, the prevalence was<br />

found to be 13.2 per 1,000 (bacillary : 4 per<br />

1.000). It is interesting to note that in the Delhi<br />

survey the rate <strong>of</strong> bacillary disease in the 6<br />

surveys carried out from 1962 to 1977 varied<br />

from 2.1 to 4 per 1,000. Tumkur survey (Raj<br />

Narain et al 1963) carried out in a rural population<br />

<strong>of</strong> 36,000 showed an overall prevalence<br />

<strong>of</strong> 19 active cases per 1,000, <strong>of</strong> which 4 per<br />

1,000 were bacillary. The NTI (1974) found<br />

practically uniform rate <strong>of</strong> bacillary disease<br />

(3 to 4 per 1,000) in rural population <strong>of</strong><br />

Bangalore district during the 4 surveys carried<br />

out between 1962 and 1968.<br />

In the Chingleput study (TPT 1980) where a<br />

rural population <strong>of</strong> about 300,000 was under<br />

surveillance in connection with a BCG trial,<br />

the prevalence <strong>of</strong> bacillary disease was<br />

Ind. J. Tub., Vol. XXIX, No. 3

EPIDEMIOLOGY OF TUBERCULOSIS IN INDIA 139<br />

extremely high (17 per 1,000 for males, 4 per<br />

1,000 for females and 11 per 1,000 for both<br />

sexes).<br />

A number <strong>of</strong> studies carried out in special<br />

groups have also brought forth interesting data.<br />

These include a survey <strong>of</strong> Delhi Police (Sikand<br />

et al, 1954-1959), Civil Servants in Delhi<br />

(Pamra et al, 1968), Textile Workers (Sikand<br />

and Raj Narain, 1953). Also <strong>of</strong> interest is a<br />

study carried out in a rural population in<br />

Bangalore in which 22,957 persons were examined;<br />

the prevalence <strong>of</strong> bacillary disease was<br />

3.0 per 1,000 (Gothi et al, 1976). In Bangalore<br />

city in a small slum population a low prevalence<br />

<strong>of</strong> bacillary disease (2.6 per 1,000) was reported<br />

(Chakarborty et al, 1979). The low prevalence<br />

in the city slums is probably a reflection <strong>of</strong> the<br />

better epidemiological situation in Bangalore,<br />

a fact which was also marked in the ICMR<br />

(1959) survey.<br />

Since radiological and bacteriological examination<br />

<strong>of</strong> children below 5 years is impracticable,<br />

no authentic information on prevalence<br />

<strong>of</strong> respiratory disease in this age group is<br />

available. However, judging from the infection<br />

rates it can be safely presumed that prevalence<br />

<strong>of</strong> disease too must be low. Prevalence <strong>of</strong> disease<br />

(including primary disease) in the age group<br />

5 to 14 years in the rural population <strong>of</strong><br />

Bangalore was reported as 0.3% (bacillary<br />

disease 0.1%) by Gothi et al (1972). Similar<br />

figures for Chingleput rural area (TPT, 1980)<br />

in the 10 to 14 years age group were 0.36%<br />

(bacillary, 0.04%). Prevalence, in general, was<br />

somewhat higher among male children. The<br />

surprising finding was that although the prevalence<br />

<strong>of</strong> infection in the 10 to 14 years age<br />

group in Chingleput was almost twice that<br />

in Balgalore rural area, the morbidity rates were<br />

not different.<br />

It was also found that children with large<br />

tuberculin test reactions (greater than 20 mm,<br />

1 TU PPD-S with RT 23) had more disease<br />

than those with small induration. As expected,<br />

the prevalence <strong>of</strong> respiratory TB in children<br />

was much less than among adults.<br />

Although extra-pulmonary tuberculosis is<br />

believed to be more common in children than<br />

adults, no authentic information about its<br />

prevalence is available from any large scale<br />

community survey. A study carried out in the<br />

slum population <strong>of</strong> Bangalore (Gothi et al,<br />

1974), in which all systems <strong>of</strong> the total child<br />

population were examined, showed a very low<br />

prevalence <strong>of</strong> all manifestations <strong>of</strong> tuberculosis<br />

(0.35%) in the age group 0 to 14 years.<br />

Incidence <strong>of</strong> disease<br />

Incidence <strong>of</strong> bacillary disease is defined as<br />

the number <strong>of</strong> new bacillary cases occurring<br />

annually at subsequent re-examination among<br />

1,000 persons either with normal chest x-ray<br />

or healed x-ray abnormality but bacteriologically<br />

negative at the previous examination (NTI,<br />

1974). The incidence <strong>of</strong> abacillary disease is<br />

the number <strong>of</strong> new radiologically active but<br />

bacteriologically negative cases arising annually<br />

among 1,000 persons with a normal chest x-ray<br />

at an earlier examination.<br />

Information regarding incidence <strong>of</strong> tuberculosis<br />

is available from four areas <strong>of</strong> the<br />

country, Madanapalle, Delhi, Bangalore and<br />

Chingleput. In the congested areas <strong>of</strong> Delhi,<br />

the overall annual incidence <strong>of</strong> bacteriologically<br />

confirmed tuberculosis was found to be 1.3 %<br />

per year (Pamra et al, 1973, Goyal et al, 1978).<br />

In rural area <strong>of</strong> Bangalore (NTI, 1974) the<br />

rate varied from 0.9 to 1.3 per 1,000 per year.<br />

Frimodt-Moller reported an incidence <strong>of</strong> 1.3<br />

per 1,000 per year in the rural population <strong>of</strong><br />

Madanapalle. On the other hand, <strong>Tuberculosis</strong><br />

Prevention Trial (1980) has shown a very<br />

high annual incidence <strong>of</strong> 2.5 per 1,000 between<br />

the first two surveys carried out in Chingleput.<br />

In all areas, incidence <strong>of</strong> bacillary disease<br />

was higher among males than in females. All<br />

four studies had shown a rising incidence with<br />

age for both sexes. Of the total ‘incidence’<br />

cases arising more than half were contributed<br />

by persons more than 35 years <strong>of</strong> age among<br />

males and less than 35 years <strong>of</strong> age among<br />

females.<br />

In the Delhi study (Goyal et al, 1978) the<br />

incidence <strong>of</strong> abacillary disease among previously<br />

healthy persons was found to vary from 1.5 to<br />

3.8 per 1,000 per year at different periods,<br />

whereas in Madanapalle it was <strong>of</strong> the order <strong>of</strong><br />

4 per 1,000 per year. The follow up <strong>of</strong> persons<br />

with healed inactive disease in Delhi showed<br />

that their breakdown rates varied considerably<br />

from One period to another, the rate <strong>of</strong> fresh<br />

bacillary disease ranging from 4 per 1,000 to<br />

14 per 1,000 per year and <strong>of</strong> active abacillary<br />

disease from 7 per 1,000 to 21 per 1,000 per<br />

year between 1962 and 1967.<br />

Also worth reporting is a study carried<br />

out by New Delhi TB Centre in Delhi Police<br />

(Sikand et al, 1959). It was found that in this<br />

group an average <strong>of</strong> 7.8 per 1,000 previously<br />

healthy persons (obviously all adults) broke<br />

down every year with tuberculosis, either<br />

bacillary or abacillary.<br />

Ind. J. Tub., Vol. XXIX, No. 3

140 G.D. GOTHI<br />

Gothi et al (1978) analysed the breakdown<br />

rate among previously healthy persons according<br />

to size <strong>of</strong> tuberculin reaction. They found<br />

that among non-reactors (0 to 9 mm), 0.41 per<br />

1,000 per year developed bacillary disease<br />

whereas among reactors (10 mm or more), the<br />

rate was 1.73 per 1,000 per year. The annual<br />

incidence rate among persons with normal<br />

x-ray chest and a tuberculin reaction between<br />

10 and 19 mm was lowest (0.27 per 1,000).<br />

It was highest (1.9 per 1,000) among those<br />

with a tuberculin reaction <strong>of</strong> 20 mm or more<br />

(NTI, 1974).<br />

The follow up <strong>of</strong> persons with inactive<br />

tuberculous or non-tuberculous lesions in the<br />

same population (Gothi et al, 1978) showed<br />

that 3.73 per 1,000 developed bacillary disease<br />

every year. It was also found that among untreated<br />

persons with radiologically active or<br />

probably active tuberculous lesions the annual<br />

breakdown to bacillary disease was 26 per<br />

1,000. An analysis <strong>of</strong> the total bacillary<br />

‘incidence cases, showed that 76% arose from<br />

the group <strong>of</strong> previous tuberculin positives. The<br />

population with normal chest x-ray at an<br />

earlier examination contributed 48% <strong>of</strong> the<br />

total new bacillary cases.<br />

Krishnamurthy et al (1976) found that<br />

the attack rate <strong>of</strong> disease among recently infected<br />

persons was 7 times higher than among<br />

those infected for more than 9 months.<br />

However, <strong>of</strong> the total new cases, 72% arose<br />

from the previously infected population, a<br />

finding which corroborates the results obtained<br />

by Frimodt-Moller (1960) and several other<br />

workers in other countries.<br />

Raj Narain et al (1972) & Gothi et al (1976)<br />

calculated the annual incidence <strong>of</strong> bacillary<br />

disease among persons with low grade tuberculin<br />

sensitivity (reaction O to 9 mm to 1 TU<br />

PPD RT 23 but more than 10 mm in the former<br />

and 8 mm in the latter study to 20 TU) which<br />

is presumed to be due to infection with Mycobacteria<br />

other than tuberculosis. The five<br />

year incidence in this group was found to be<br />

1.4 per 1,000 which was significantly lower<br />

than among reactors to 1 TU PPD RT 23<br />

(10.8 per 1,000 per year). Among non-reactors<br />

to 20 TU PPD RT 23 it was 2.6 per 1,000<br />

(Gothi et al. 1976).<br />

A point <strong>of</strong> some importance is the length<br />

<strong>of</strong> interval between two consecutive surveys<br />

in longitudinal studies. In the studies reported<br />

above the intervals varied from one to 2½<br />

years. While calculating incidence rates between<br />

any two surveys one always takes into account<br />

symptomatic breakdowns occurring during the<br />

Ind. J, Tub., Vol. XXIX, No. 3<br />

interval. However, it is not inconceivable that,<br />

if the interval is long, some cases may develop<br />

the disease and die or get cured without treatment<br />

and thus miss being counted in the calculation<br />

<strong>of</strong> incidence rates. To that extent,<br />

calculation <strong>of</strong> incidence rates from longitudinal<br />

surveys could be regarded, theoretically, as an<br />

under-estimate. To assess the extent <strong>of</strong> this<br />

possible under-estimate, Gothi et al (1978)<br />

carried out a study in Bangalore rural population<br />

in which a group <strong>of</strong> 30,576 was examined<br />

after a short interval <strong>of</strong> 3 months. The incidence<br />

during the 3-month period was .99 per 1,000<br />

as against the reported annual incidence rates<br />

<strong>of</strong> 1.3 per 1,000 in some other studies (Frimodt-<br />

Moller, 1976; Pamra et al, 1978; NTI, 1974).<br />

From this, it would appear that there is probably<br />

a significant imprecision in the estimates <strong>of</strong><br />

annual incidence as calculated in the studies<br />

referred to above, in which re-examination <strong>of</strong><br />

population was carried out after long intervals.<br />

Another possible source <strong>of</strong> error is the fact<br />

that the second survey may bring to light healed<br />

lesions among persons who had a clear x-ray<br />

at the first survey. Such persons must have had<br />

active disease sometime between the surveys<br />

and must not be ignored while calculating<br />

incidence rates.<br />

Incidence <strong>of</strong> disease among children is a<br />

parameter <strong>of</strong> special interest. Gothi et al (1972)<br />

reported the incidence in 5 to 9 year and 10 to<br />

14 year age groups as 0.5 and 1.0 per 1.000<br />

respectively. Children with a large tuberculin<br />

reaction (>20 mm) were found to have a higher<br />

incidence as also those who had been newly<br />

infected between the two surveys. It is possible<br />

that the newly infected lack resistance with the<br />

result that containment <strong>of</strong> infection takes a<br />

long time and disease manifests itself within<br />

a short period after infection leading to high<br />

morbidity and mortality. New disease was<br />

also seen among children who continued to<br />

remain non-reactors to tuberculin. A plausible<br />

reason for such findings could be (i) tuberculin<br />

test being given in pre-allergic phase or (ii)<br />

overwhelming infection which suppressed the<br />

hypersensitivity.<br />

Narmada et al (1977) reported an incidence<br />

<strong>of</strong> 2.8 per 1,000 per year in the age group 0-12<br />

years in a congested area <strong>of</strong> Madras and 1.2<br />

per 1,000 per year among the non-infected and<br />

8.8 per 1,000 per year among the infected.<br />

The high rates in this population reflect the<br />

unhygienic conditions as well as the chances<br />

<strong>of</strong> acquiring massive and repeated super-infection<br />

among children <strong>of</strong> poor nutritional status.<br />

The low rates prevalence and incidence<br />

<strong>of</strong> infection and disease suggest that respiratory

EPIDEMIOLOGY OF TUBERCULOSIS IN INDIA 141<br />

‘<br />

tuberculosis is not a major problem <strong>of</strong> childhood.<br />

However, it appears that recently infected<br />

children and those with a strong tuberculin<br />

reaction have higher risk <strong>of</strong> developing disease<br />

and dying <strong>of</strong> it.<br />

<strong>Tuberculosis</strong> mortality<br />

In the absence <strong>of</strong> notification regarding<br />

cause <strong>of</strong> death, very little is known about<br />

tuberculosis mortality rates in India. One <strong>of</strong><br />

the earliest reports on the subject is by Sir<br />

Leonard Roger (quoted by Lankaster, 1920)<br />

who, on the basis <strong>of</strong> 22 years’ post-mortem<br />

records <strong>of</strong> Calcutta, concluded that 17% <strong>of</strong><br />

the total deaths were due to tuberculosis and<br />

estimated the annual tuberculosis mortality<br />

as 800 per 100,000 <strong>of</strong> population. Lankaster<br />

(1920) on the basis <strong>of</strong> Roger’s data and some<br />

other available information reported that<br />

Ahmedabad had an annual tuberculosis mortality<br />

<strong>of</strong> 591 per 100,000 and put forward a speculative<br />

estimate <strong>of</strong> at least 400 per 100,000 per year<br />

for most Indian cities. Benjamin et al<br />

(1949) on the basis <strong>of</strong> the Saidapet study put<br />

the estimate at 462 per 100,000. McDougal<br />

(1949) estimated the annual mortality in India<br />

at about 200 per 100,000 and in the same year,<br />

Frimodt-Moller arrived at a rate <strong>of</strong> 253 per<br />

100,000 on the basis <strong>of</strong> Madanapalle study.<br />

Frimodt-Moller (1960) reported that tuberculosis<br />

mortality in the area declined from 64<br />

per 100,000 in 1953-54 to 21 per 100,000 in<br />

1954-55. The marked reduction was probably<br />

due to incomplete recording <strong>of</strong> deaths as natural<br />

decline and intensive treatment could not have<br />

achieved it in so short a time.<br />

Chakarborty et al (1978), from data collected in<br />

Bangalore area estimated the mortality rate at<br />

84 per 100,000 and further found that the rate<br />

was higher in males and in the older age groups,<br />

(a finding which corroborates earlier results <strong>of</strong><br />

Frimodt-Moller, 1960). Among females the<br />

highest mortality was in the age group 30 to 39<br />

years. It may be mentioned that data collected<br />

in the Bangalore area represented the natural<br />

trend since anti-TB services could not be<br />

provided in the area concerned. Goyal et al<br />

(1978) reported an annual mortality rate <strong>of</strong><br />

about 40 per 100,000 in a congested area <strong>of</strong><br />

Delhi where good domiciliary treatment service<br />

was provided. It must, however, be pointed out<br />

that in this calculation no correction was made<br />

for any possible deaths due to non-tuberculous<br />

conditions among tuberculous patients who<br />

died.<br />

Even taking into account the varying reliability<br />

<strong>of</strong> the data collected at different periods<br />

<strong>of</strong> time by different workers, there is little doubt<br />

that tuberculosis mortality is much less to day<br />

than it was in the forties. It is however not<br />

possible to comment on the factors responsible<br />

for the decline which could be due to one or<br />

more factors such as (i) natural decline as a<br />

result <strong>of</strong> increased resistance and socio-economic<br />

betterment, (ii) availability <strong>of</strong> more effective<br />

specific anti-TB measures or (iii) increase in<br />

the number <strong>of</strong> patients coming forward for<br />

treatment in the wake <strong>of</strong> efficient chemotherapy.<br />

Little is known about tuberculosis mortality<br />

in children. Raj Narain (1975) compared the<br />

crude mortality rates among infected and noninfected<br />

children on the assumption that the<br />

differences in the two could be ascribed to tuberculosis.<br />

<strong>Tuberculosis</strong> mortality among children<br />

aged 1 to 4 years on this assumption was found<br />

to be 5.5, 5.2 and 23.9 per 10,000 children in<br />

rural Bangalore, Chingleput and Choolai<br />

city area <strong>of</strong> Madras respectively. The mortality<br />

rate was significantly higher among children<br />

with a tuberculin reaction <strong>of</strong> 20 mm or more,<br />

specially in the O to 4 years age group. Raju<br />

et al (1971) reported a higher mortality rate<br />

among infected compared to non-infected<br />

children below 5 years. Gothi et al (1972)<br />

reported that <strong>of</strong> the total deaths from any<br />

cause in the age group O to 14 years, 19%<br />

could be ascribed to TB.<br />

INH resistance<br />

In recent years, a new index has been added<br />

to the usual indices employed for assessing the<br />

tuberculosis situation in any community. This<br />

is the prevalence <strong>of</strong> primary drug resistance<br />

(specially to INH) in any community. Although<br />

a number <strong>of</strong> antimicrobial drugs have been<br />

in use during the last 30 years, INH is, for<br />

several reasons, the most important and widely<br />

used <strong>of</strong> all the drugs and forms part <strong>of</strong> all regimens<br />

being prescribed anywhere. Primary<br />

resistance to INH may be regarded mainly as<br />

a consequence <strong>of</strong> unsatisfactory therapy <strong>of</strong><br />

infectors (the only other reason being mutation<br />

<strong>of</strong> bacilli) and is a reflection on the quality <strong>of</strong><br />

anti-TB services provided to the community<br />

and availed <strong>of</strong> by the patients. Although the<br />

significance <strong>of</strong> INH resistance is still a moot<br />

point, yet the prevalence <strong>of</strong> primary resistance<br />

in the community is now considered a factor<br />

<strong>of</strong> considerable epidemiological importance.<br />

As in the case <strong>of</strong> other indices there is<br />

considerable lack <strong>of</strong> uniformity in the data<br />

available. This arises due to a number <strong>of</strong> factors<br />

such as (i) differences in the techniques used<br />

and standards adopted for defining drug resistance<br />

and (ii) difference in the care taken to<br />

elicit history <strong>of</strong> previous treatment.<br />

Ind. J. Tub., Vol. XXIX, No. 3

142 G.D. GOTHI<br />

Findings on the subject have been reported<br />

by different workers. Frimodt-Moller (1962)<br />

found INH resistant strains in 6% <strong>of</strong> the untreated<br />

sputum positive patients in Madanapalle<br />

area. Parthasarthy et al (1967) estimated the<br />

prevalence <strong>of</strong> disease with primary INH resistant<br />

strains as 0.9 and 0.8 per 10,000 in the rural<br />

population <strong>of</strong> Rayachoty and Madanapalle<br />

respectively and in Madanapalle town, 6 per<br />

10,000. In the rural areas <strong>of</strong> Bangalore, Raj<br />

Narain et al (1967) reported prevalence <strong>of</strong><br />

INH resistance among bacteriologically confirmed<br />

cases as 12%, 15.4% and 25.4% during 3<br />

surveys carried out between 1961 and 1966.<br />

One fourth <strong>of</strong> these were considered as primary<br />

resistance. However due to unreliable history<br />

<strong>of</strong> previous treatment this finding can be<br />

considered questionable.<br />

A number <strong>of</strong> reports are available regarding<br />

prevalence <strong>of</strong> INH resistant strains among<br />

persons reporting for treatment. Menon (1963)<br />

reported a figure <strong>of</strong> 15% from Hyderabad<br />

which in the subsequent year rose to 21 %<br />

(Menon, 1964); Pamra (1967) reported a figure<br />

<strong>of</strong> 14.1 % from Delhi. Rao et al (1967) reported<br />

that among sanatorium patients, 53.7% were<br />

INH resistant, the corresponding figure in<br />

patients attending a clinic being 27.5% in<br />

rural primary health centre, 32.5%, in selective<br />

house to house case finding programme in rural<br />

areas, 15.5%, and in general population surveys,<br />

11.2%. The history <strong>of</strong> their previous treatment<br />

was not reported.<br />

In 1967, Gangadharam reported the results<br />

<strong>of</strong> a co-operative investigation sponsored by<br />

the ICMR among previously untreated patients<br />

attending 9 urban clinics in the country situated<br />

in Delhi, Bombay, Calcutta, Madras, Bangalore,<br />

Patna, Nagpur, Hyderabad and Amritsar.<br />

Among untreated patients the overall figure<br />

for INH resistant strains was 16%. Among<br />

treated patients the corresponding figure was<br />

46%, nearly three times as high as in untreated.<br />

It may be worth pointing out that history<br />

<strong>of</strong> previous treatment was probably not uniformly<br />

reliable in this investigation.<br />

In the longitudinal surveys carried out by<br />

NTI in rural areas, the proportion <strong>of</strong> sputum<br />

positive patients with INH resistant strains<br />

rose from 11.2% at the first survey to 21.6%<br />

at the 4th survey. The increase was ascribed<br />

to longer survival <strong>of</strong> the resistant cases <strong>of</strong> earlier<br />

surveys and the emergence <strong>of</strong> resistant strains<br />

due to insufficient treatment among those who<br />

had earlier shown sensitive strains. Among the<br />

newly discovered (‘incidence’) cases the percentage<br />

with INH resistant strains during three<br />

successive inter-survey periods was 11.4 %,<br />

Ind. J. Tub., Vol. XXIX, No. 3<br />

10.0% and 6.4% whereas in the Delhi study<br />

there was no significant change in the primary<br />

resistance pattern over a 15 years’ period.<br />

Fate <strong>of</strong> TB patients in the community<br />

The rural population <strong>of</strong> Bangalore was<br />

surveyed 4 times during a period <strong>of</strong> 5 years<br />

at an -interval <strong>of</strong> 1J and 2 years. The patients<br />

discovered in this study could not be <strong>of</strong>fered<br />

treatment for want <strong>of</strong> resources and facilities.<br />

Pamra (1966) and Goyal et al (1978) have also<br />

reported on the fate <strong>of</strong> cases from their longitudinal<br />

study conducted in a congested city<br />

area <strong>of</strong> Delhi. In this study all patients discovered<br />

were <strong>of</strong>fered good intensive ambulatory<br />

domiciliary treatment. Another study by<br />

Frimodt-Moller (1961) gave similar data about<br />

the rural area <strong>of</strong> Madanapalle distinct where<br />

too the patients were provided satisfactory<br />

service. Raj Narain reported a tuberculosis<br />

case fatality <strong>of</strong> 34% and sputum conversion <strong>of</strong><br />

11 % in patients 1½ years after the first survey;<br />

24% continued to remain positive. The fate<br />

<strong>of</strong> direct smear positive culture negative patients<br />

was somewhat better, death rate being 18.4%.<br />

A 5 year study reported by NTI (1974)<br />

shows that <strong>of</strong> the 178 sputum positive patients,<br />

126 could be followed up. Of these 49.2%<br />

died, 18.3% continued to remain bacillary and<br />

sputa <strong>of</strong> 32.5% became negative. Death rates<br />

were reported to be highest during the initial<br />

1½ years period <strong>of</strong> observation; subsequent<br />

survivors continued to live longer and remained<br />

bacillary. Of the new sputum positive cases<br />

discovered during subsequent surveys amongst<br />

the abacillary population <strong>of</strong> the first survey,<br />

sputum conversion rate during the 1½ years<br />

was 52%, mortality 14.3%; 33.3% remained<br />

sputum positive. The fate <strong>of</strong> old cases <strong>of</strong><br />

previous surveys which were considered as<br />

‘prevalence cases’ was poorer than that <strong>of</strong> new<br />

cases discovered in the subsequent surveys.<br />

Frimodt-Moller, on the basis <strong>of</strong> the longitudinal<br />

survey, reported a high mortality<br />

(31.1%) amongst advanced cases in a year;<br />

18% improved. It was further seen that the<br />

mortality in the other category <strong>of</strong> cases was less.<br />