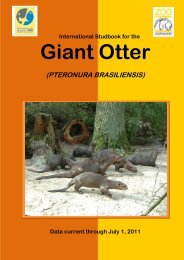

International Giant Otter Studbook Husbandry and Management

International Giant Otter Studbook Husbandry and Management

International Giant Otter Studbook Husbandry and Management

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

action be taken to resolve these problems <strong>and</strong> that all institutions/persons involved undertake<br />

these goals <strong>and</strong> openly communicate <strong>and</strong> share information with the professional community.<br />

“Hacking out is probably the best technique for release available, but it should be noted that this<br />

is controversial to some, <strong>and</strong> survival rates are questionable due to lack of experience <strong>and</strong> lack<br />

of exposure to diseases, among other problems.” (Burnette 1994). This is regardless of whether<br />

the otter is released before or after it becomes sexually mature. It remains controversial to<br />

some because it is thought that even with the best scientific techniques, otter caretakers cannot<br />

prepare or teach the otter how to deal with all of the potentially hazardous situations or<br />

challenging environmental conditions it may encounter in the wild. Caretakers can neither fully<br />

present h<strong>and</strong>reared otters with the real life exposure they would have had if reared in the wild,<br />

nor can they fully substitute for the training <strong>and</strong> social interactions natural parents <strong>and</strong> siblings<br />

would have provided. (In the wild giant otters do not leave the family group until they are two to<br />

three years old <strong>and</strong> they are dependent on their family for survival until then.) <strong>Giant</strong> otters<br />

already inhabiting the territory the releasee is destined for, may prove too great of competition<br />

for the releasee (i.e. limiting denning <strong>and</strong> fishing areas, etc.) or they may kill the releasee.<br />

Released otters may also be unable to find mates or establish family groups <strong>and</strong> being solitary<br />

can make survival much more difficult. They also may not be successful at rearing their own<br />

litters, without the first-h<strong>and</strong> experience of being reared by parents or helping to rear younger<br />

siblings (as done in the wild). Whether the otter is already returned to the wild or it is exposed<br />

to wild conditions during the rearing/hacking out/rehabilitation process, predators (i.e. caiman)<br />

may kill the inexperienced otters or the otter may approach humans (i.e. because they have lost<br />

their fear of humans) <strong>and</strong> this may result in their harm, death, or capture. During the hacking<br />

out/rehabilitation process wild giant otters may also kill the inexperienced otters while they are<br />

being exposed to conditions in the wild. (Of course, this is dependent on the type of method<br />

that is used during hacking out/rearing.) <strong>Otter</strong>s that are being hacked out/reared in conditions in<br />

the wild or releasees, which are generally not used to exposure to a wide variety of different<br />

diseases/pathogens, may be especially susceptible to contracting diseases which may cause their<br />

death.<br />

Unfortunately, reports have shown the combined mortality rate of h<strong>and</strong>reared orphaned wild<br />

giant otters that have been reared/rehabilitated/hacked out for release <strong>and</strong> those that were finally<br />

fully released back into the wild have been very high (i.e. the majority did not survive) because<br />

of some of the same problems as mentioned above. Most (either during the rearing/hacking<br />

out/rehabilitation process for release or after final release) got killed by wild giant otters, people,<br />

or caiman. Some attempts to finally release the giant otters have also been unsuccessful. It is<br />

important to note that, from what is known, it is generally rare that orphaned h<strong>and</strong>reared giant<br />

otters have been released back into the wild <strong>and</strong> to date, the releases below are the only ones that<br />

are known to have occurred or been attempted.<br />

To date, the only known cases that have been published about giant otter re-introduction <strong>and</strong><br />

hacking out were in Colombia (Gomez, Jorgenson, & Valbuena 1999) <strong>and</strong> in Guyana at<br />

Karanambu Ranch (McTurk & Spelman 2004). The report by Gomez et. al. (1999) included<br />

very general notes on the hacking out procedure used. It is as follows. One orphaned wild otter<br />

was h<strong>and</strong>reared for 6 months <strong>and</strong> the other was h<strong>and</strong>reared for one month before their release.<br />

They were h<strong>and</strong>reared for one month together <strong>and</strong> they were also released together. One animal<br />

was 5.5 months old <strong>and</strong> the other 8 months old at the time of their release. The study concludes<br />

that the release was successful <strong>and</strong> the authors (who carried out this project) determined it was a<br />

success based on the observations of these two animals three times in a one month period after<br />

their release. During these times, the two cubs were identified <strong>and</strong> the authors were “sure” that<br />

66