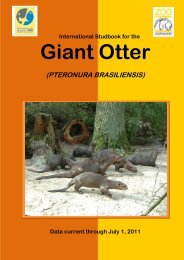

International Giant Otter Studbook Husbandry and Management

International Giant Otter Studbook Husbandry and Management

International Giant Otter Studbook Husbandry and Management

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Section 2<br />

Breeding, Cub-Rearing Success & Privacy from Human Disturbances<br />

A self-sustaining captive giant otter population has never been created. Very few zoos in the<br />

world have had successful reproduction. In captivity P. brasiliensis does not appear to be<br />

particularly difficult to keep, but successful rearing of offspring has been rare, as high cub<br />

mortality exists world-wide <strong>and</strong> historically (Sykes 1997-99 & 1998/2002; Sykes-Gatz 2001 &<br />

unpublished data, 2003). See Tables 2-3. From 1968 to 1997, seven institutions reported<br />

captive giant otter births. Litter size (n=31; i.e. litter sample size) ranged from 1 to 6 cubs, with<br />

a mean of 2.9 <strong>and</strong> common litter size of 2 cubs. Of 177 cubs born live at seven institutions<br />

(born 1968 -1997), only 16.4 % (29) were successfully reared (i.e. survived to one year of age or<br />

older). This is an 83% cub mortality rate. [In 2003 more detailed census records became<br />

available, so the cub survival rate reported in Sykes-Gatz 2001 was updated <strong>and</strong> slightly<br />

increased for current census records.] More detailed data available for 90 of those 177 cubs,<br />

indicated that 53% died during the first week of life, while 50% of the cubs surviving to one<br />

week, died before reaching four months of age. (See Graph 1.) Most of these deaths occurred<br />

because parents, stressed by human disturbances, failed to properly care for their cubs. This<br />

was the primary cause of death. These two main mortality phases show that different factors<br />

were responsible; i.e. gross parental neglect in the first week (when most cubs were eaten or/<strong>and</strong><br />

not cared for properly) <strong>and</strong> medical illness either independent of or resulting from parental<br />

neglect thereafter. Medical illnesses that were commonly reported when cub deaths occurred<br />

were pneumonia, enteritis, malnutrition, <strong>and</strong> intestinal invagination (Trebbau 1972; Autuori <strong>and</strong><br />

Deutsch 1977; Flügger 1997; Brasilia Zoo; pers. comm.; Dortmund Zoo, pers. comm.). Many<br />

of these illnesses were thought to be secondary causes of death that developed as a result of<br />

parental neglect/cub abuse.<br />

From 1968 to 1997, all of the zoos with successful parent reared litters, provided parents with<br />

privacy <strong>and</strong> isolation/seclusion from human disturbances (visual <strong>and</strong> acoustic) <strong>and</strong> presence<br />

(zoo staff <strong>and</strong> visitors) during cub-rearing. Either their management methods (which were only<br />

discovered <strong>and</strong> carried out after the loss of many litters) <strong>and</strong>/or “exhibit design” permitted<br />

privacy. (“Exhibit design” means that the enclosures were natural or semi-natural <strong>and</strong><br />

expansive, i.e. at least 600m² (6,458.4 ft²) or more in size, <strong>and</strong> the otters could dig their own<br />

dens underground to keep their cubs in. For management methods provided see Chapter 2<br />

Section 10 <strong>and</strong> for “exhibit designs” provided see Chapter 2 Sections 10 & 12.) This is the most<br />

important management factor needed to help parents rear litters successfully. (Great emphasis<br />

has been placed on this management method throughout this manual <strong>and</strong> its 1 st edition. See<br />

Chapter 2 Section 10 <strong>and</strong> below under “Historical Overview” for information on this method.)<br />

From 1998 to 2002, four zoos reported litter births (40 cubs were born live) (Sykes-Gatz,<br />

unpublished report). Three zoos (Belem* <strong>and</strong> Brasilia in Brazil <strong>and</strong> Cali in Colombia) reported<br />

successfully rearing cubs (i.e. 16 of their 23 cubs total, were reared to one year of age or older).<br />

[*Both Museu Paraense Emilio Goeldi (Belem, Brazil) <strong>and</strong> Criatorio Crocodilo Safari (Belem,<br />

Brazil), the private facility associated with Museu Goeldi, are referred to under “Belem”. The<br />

breeding pair at Museu Goeldi was loaned to Criatorio Crocodilo Safari in 2001 where the pair<br />

had one litter (in 2002) while they were held at this institution. The parents successfully reared<br />

the one litter born at the Safari <strong>and</strong> they had successfully reared 2 litters born at Museu Goeldi.<br />

Because the same pair gave birth to at least one or more successful litters at both of the two<br />

aforementioned institutions, these institutions are associated, <strong>and</strong> no other breeding pairs were<br />

known to be held at these institutions, these two institutions, except where noted, are counted as<br />

one institution for all data within this manual <strong>and</strong> are referred to as “Belem”.] Inherited thyroid<br />

20