Leaders of Latin American Revolutions Fact Sheet - Galileo ...

Leaders of Latin American Revolutions Fact Sheet - Galileo ...

Leaders of Latin American Revolutions Fact Sheet - Galileo ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

1

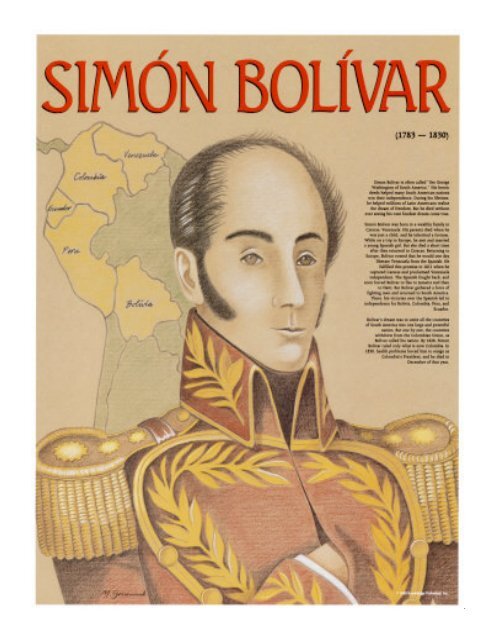

Simón Bolívar<br />

Grandiose in his schemes, headstrong and difficult, Simón Bolívar nevertheless conquered enormous<br />

obstacles in gaining South <strong>American</strong> independence from Spain, particularly in his homeland <strong>of</strong> Venezuela.<br />

Bolívar was born on July 24, 1783 in Caracas, Venezuela to a wealthy family <strong>of</strong> Spanish descent. By the<br />

time he was nine years old, he had lost both his parents, and his maternal uncle, Carlos Palacios, supervised his<br />

upbringing. From a tutor, he learned Enlightenment ideas and was especially attracted to the philosophy <strong>of</strong><br />

Jean-Jacques Rousseau. In 1799, he was sent to Europe, where he completed his education. He lived in Spain<br />

for three years and married Maria Teresa de Toro, the daughter <strong>of</strong> a Spanish nobleman. Soon after Bolívar<br />

returned to Venezuela in 1802, his wife died <strong>of</strong> yellow fever.<br />

Bolívar again journeyed to Europe in 1804 and visited Italy and France, where Napoleon I's grandeur<br />

impressed him. He traveled to the United States in 1807 and then sailed to Venezuela. The following year, the<br />

Spanish Empire trembled when Emperor Napoleon I conquered the Iberian peninsula and appointed his brother<br />

ruler <strong>of</strong> Spain. In Spanish America, confusion resulted. Although the colonies unanimously refused to recognize<br />

the new ruler, some colonists opted to remain loyal to the deposed king, while others decided to fight for<br />

independence. Bolívar sided with the latter and in 1810, joined a revolutionary group that expelled the Spanish<br />

governor from Venezuela. The ruling junta then sent Bolívar to England in search <strong>of</strong> assistance. Although the<br />

English refused Bolívar's requests, the revolutionary convinced Francisco de Miranda, a prominent Venezuelan<br />

nationalist, to return home and help the rebellion.<br />

In 1811, Venezuela declared its independence, and early the following year, Miranda became head <strong>of</strong><br />

the revolutionary government (the rebel Congress eventually granted him dictatorial powers). Bolívar won an<br />

important battle at Valencia, an engagement that earned him the loyalty and admiration <strong>of</strong> his men. A split<br />

developed in the revolutionary leadership, however. Miranda gained Bolívar's enmity when he signed an<br />

armistice with Spain—a move engendered in part by Bolívar's having lost a harbor fortress to the enemy.<br />

Bolívar then delivered Miranda to the Spanish. In gratitude, Spain decided not to jail Bolívar and instead<br />

rewarded him with passage to Curacao, a Dutch Caribbean island.<br />

After journeying to New Granada (Colombia), Bolívar planned another attack and in August 1813, led<br />

an army triumphantly into Caracas, proclaimed the country a republic, and was made its leader with the title <strong>of</strong><br />

"Liberator." He had not, however, secured his position, and in 1814, the Spanish, supported by Venezuelan<br />

llaneros, or cowboys, defeated the Liberator, who fled to Jamaica. Bolívar then wrote one <strong>of</strong> the most important<br />

works in <strong>Latin</strong> <strong>American</strong> history, "The Letter from Jamaica," in which he expressed his grand scheme to<br />

establish republics throughout Spanish America with representative bodies and presidents chosen for life.<br />

Anxious to continue the fight, he obtained weapons and money from Haiti and in March 1816, sailed for<br />

Venezuela. However, Spanish forces again turned him away.<br />

2

Despite this setback, several factors converged to work in Bolívar's favor. For one, the llaneros, led by<br />

José Antonio Páez, a daring cavalryman who became one <strong>of</strong> the founders <strong>of</strong> Venezuela, shifted their loyalty to<br />

the revolutionaries. Second, Bolívar changed his strategy to focus on the resource-rich Orinoco River basin,<br />

rather than Caracas with its heavy fortifications. Third, several thousand adventurers arrived from England to<br />

help Bolívar.<br />

In 1817, Bolívar led his army into the Orinoco region and established a temporary capital, Angostura.<br />

He then surprised the Spanish by attacking New Granada. In 1819, he and his men trekked through steamy<br />

tropical jungles and across the frigid 11,000-foot Andes and on August 7, met the enemy at Boyacá, scoring a<br />

stunning victory.<br />

Even though Spain still held substantial territory, Bolívar audaciously formed a new state, Gran<br />

Colombia, encompassing Colombia, Venezuela, and Ecuador. By now, he held the initiative, and turmoil within<br />

Spain disrupted the Spanish war effort. In June 1821, Bolívar, leading an army <strong>of</strong> 6,500 men, won a crucial<br />

battle at Carabobo, and the following year, Antonio de Sucre, Bolívar's foremost general, defeated the Spanish<br />

at Pichincha, in Ecuador. On June 16, Bolívar marched his army into Quito. Thus Gran Colombia had been<br />

liberated, and Bolívar ruled under a new constitution that made him president.<br />

Spain still maintained control <strong>of</strong> Peru, however, and at this point, Bolívar met with José de San Martín,<br />

the great Argentinean revolutionary who had liberated his homeland and Chile. San Martín had already entered<br />

Lima and declared Peruvian independence, but the Spanish retained a grip on the interior. On July 26, 1822,<br />

Bolívar and San Martín conferred at Guayaquil in Ecuador. Details <strong>of</strong> their discussion have been lost, but San<br />

Martín left Ecuador, apparently resigned to Bolívar's dominance, and went into exile.<br />

In August 1824, Bolívar and Sucre defeated the Spanish at Junin in Peru, and four months later, Sucre<br />

defeated them at Ayacucho. The country was now free <strong>of</strong> Spanish influence, and Bolívar was made president <strong>of</strong><br />

Gran Colombia and Peru. In 1825, Sucre eliminated the last Spanish opposition in Upper Peru, which upon<br />

independence became the country <strong>of</strong> Bolivia, named after Bolívar. Bolívar drafted the constitution for that<br />

republic, complete with a weak legislature and a lifetime president, a position filled by Sucre (after Bolívar<br />

ruled on an interim basis for five months).<br />

Bolívar, meanwhile, battled severe illness and a spreading discontent with his rule. In 1826, he crafted a<br />

league <strong>of</strong> Hispanic-<strong>American</strong> states that held a congress in Panama. Colombia, Peru, Mexico, and the Central<br />

<strong>American</strong> Federation sent delegates, and they agreed to a treaty <strong>of</strong> alliance. Plans for a joint military and a<br />

regular congress proved unsuccessful, however.<br />

Civil war soon erupted in Gran Colombia when Venezuelan and Colombian forces clashed. Bolívar<br />

quickly left Peru and arranged a new constitution that granted Venezuela greater autonomy. Elections to a<br />

national convention in 1828 produced more opposition to Bolívar, who then assumed dictatorial powers over<br />

3

Gran Colombia. That autumn, dissidents tried to kill Bolívar but failed. As he battled tuberculosis, Venezuela<br />

seceded from Gran Colombia in September 1830, followed by Ecuador.<br />

On May 3, 1830, Bolívar left Bogotá, headed for exile in Europe, but he made it only to Santa Marta on<br />

the Caribbean coast, where he died on December 17.<br />

Further reading:<br />

Angell, Hildegarde, Simón Bolívar: South <strong>American</strong> Liberator, 1930; Del Rio, Daniel, Simón Bolívar, 1965;<br />

Johnson, John J., Simón Bolívar and Spanish <strong>American</strong> Independence, 1783-1830, 1968; Masur, Gerhard,<br />

Simón Bolívar, 1969; Trend, J. B., Bolívar and the Independence <strong>of</strong> Spanish America, 1946; Wepman, Dennis,<br />

Simón Bolívar, 1985.<br />

Source:<br />

"Simón Bolívar." World History: The Modern Era. ABC-CLIO, 2010. Web. 19 Jan. 2010.<br />

.<br />

4

<br />

5

Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla<br />

Father Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla was the author <strong>of</strong> the "Grito de Dolores" ("Cry from Dolores"), the<br />

passionate speech in his parish <strong>of</strong> Dolores that ignited the independence struggle in Mexico on September 16,<br />

1810. Leading a rebellion <strong>of</strong> Indian peasants and mestizos (mixed-bloods) against Spanish colonial rule,<br />

Hidalgo became wildly popular and badly frightened the colony's white elite, who joined forces to defeat his<br />

army in 1811.<br />

Hidalgo was born on May 8, 1753 in Guanajuato, Mexico on the Corralejo hacienda <strong>of</strong> which his father<br />

was the manager. He entered a school in Valladolid (now Morelia) and studied theology under the strong<br />

influence <strong>of</strong> the Jesuit Order. People he knew began to call him "the Fox" because they considered him sly and<br />

crafty. Upon his graduation in 1782, Hidalgo became a Roman Catholic priest and a pr<strong>of</strong>essor at the famous<br />

seminary <strong>of</strong> San Nicolás, where he wrote two treatises concerning theology.<br />

Hidalgo was assigned to fulfill his priestly duties in a wealthy parish in San Felipe Torres Mochas.<br />

Before long, however, his parishioners began to complain that Hidalgo's activities and thoughts were too<br />

radical. He critics went before the Inquisition to accuse him <strong>of</strong> gambling and womanizing, complaining <strong>of</strong> his<br />

continual celebrations that they referred to as "little France." His opponents also accused Hidalgo <strong>of</strong> public<br />

heresy, claiming they had heard him deny the existence <strong>of</strong> hell, lampoon Santa Teresa, and argue that<br />

"fornication is not a sin." The wayward priest also read banned books. Despite these accusations, Hidalgo<br />

continued untouched by the authorities.<br />

In his parish work, Hidalgo did not like the mundane aspects <strong>of</strong> the priesthood; he consumed money<br />

lavishly and was <strong>of</strong>ten late to repay his loans. He preferred to preach and enjoyed the tasks <strong>of</strong> paternal<br />

humanitarianism. He learned the language <strong>of</strong> the Indians <strong>of</strong> his parish and taught them trades. In Dolores, he put<br />

particular effort into cultivating silk from silkworms, one <strong>of</strong> the more famous <strong>of</strong> his large-scale projects.<br />

Hidalgo was part <strong>of</strong> an intellectual circle <strong>of</strong> priests who had access to all varieties <strong>of</strong> European and<br />

colonial literature. His friend Bishop Manuel Abad y Queipo enjoyed such liberal writers <strong>of</strong> the Enlightenment<br />

as Adam Smith and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. In contrast, Hidalgo preferred earlier critics <strong>of</strong> monarchy and<br />

absolutism. Hidalgo agreed with early 17th-century Spanish philosopher Francisco Suárez, who had written that<br />

political sovereignty resided in the people, not the king. Hidalgo supported these ideas and their implication that<br />

Mexican-born Spaniards—criollos or Creoles—were the sovereigns <strong>of</strong> Mexico.<br />

Hidalgo and several other Creoles in the local government began to conspire against the Spanish crown.<br />

Throughout <strong>Latin</strong> America, the Creole population was denied access to the privileged government positions it<br />

was qualified to hold by a crown policy that insisted on sending <strong>of</strong>ficials directly from Spain to run the colonies.<br />

Resentment about Spanish preferment was very strong in some regions, as Creoles hoped to free the colonies<br />

from Spain in order to assume the privileges <strong>of</strong> Spanish government themselves. Hidalgo had other motives as<br />

well. In 1804, the Spanish government had passed a controversial law, the Consolidación de Vales Reales, in an<br />

6

attempt to raise royal revenues. As a result <strong>of</strong> these measures, the government had taken money from the<br />

Hidalgo family, almost ruining the family fortune and pushing Hidalgo's brother toward madness.<br />

In September 1810, one member <strong>of</strong> the anticrown conspiracy betrayed the others by informing royal<br />

<strong>of</strong>ficials <strong>of</strong> the plot. Now forced to make his move, Hidalgo claimed that his rebellion was not only for the<br />

Creoles but for all Mexicans. Proclaiming his authority in the name <strong>of</strong> the Mexican nation, on September 16,<br />

1810, Hidalgo rang his church bell. Once the parishioners assembled, he delivered the legendary "Grito de<br />

Dolores." He cried, "Death to the Spaniards! Long live the Virgin <strong>of</strong> Guadalupe!" Riding an emotional high,<br />

Hidalgo took an image <strong>of</strong> the virgin on canvas and placed it on a stick to lead the rebellion. Without delay, the<br />

group followed his call to sack and destroy the homes <strong>of</strong> all Spaniards. More than 20,000 <strong>of</strong> the region's poor<br />

and oppressed Indians and mestizos followed him. Creole observers characterized the rebellion as a crude and<br />

unruly mob. This upset Hidalgo, since he wanted the revolution to free Creoles <strong>of</strong> Spanish rule. Less than 100<br />

Creoles would ever join, however, so Hidalgo made do with his roving horde.<br />

Hidalgo and his unorganized rebellion moved toward the city <strong>of</strong> Guanajuato. News <strong>of</strong> the rebellion and<br />

its violence reached the city ahead <strong>of</strong> them. Some <strong>of</strong> the Spanish population fled, while others remained to<br />

defend their wealth. Once the army entered the city, the rebellion killed any white people it found, followed by<br />

looting and destruction <strong>of</strong> property. One survivor described the scene as a frenzy <strong>of</strong> racial hatred. The rebellion<br />

and its violence against all white Mexicans galvanized the Spaniards and Creoles <strong>of</strong> Mexico. Instead <strong>of</strong><br />

dwelling on their differences, these two groups were inspired by Hidalgo's threat to view each other as allies.<br />

After the sacking <strong>of</strong> Guanajuato, Hidalgo was unsure <strong>of</strong> his next move; he did not have a specific<br />

military strategy. The army moved forward and captured Valladolid, after which his old friend, Bishop Abad y<br />

Queipo, excommunicated Hidalgo. To show his indifference, Hidalgo proceeded in a more radical direction and<br />

declared the abolition <strong>of</strong> slavery in Mexico.<br />

Hidalgo's army consisted <strong>of</strong> mostly Indians and mestizos to whom the respective ideals <strong>of</strong> republicanism<br />

and absolutism were far less important than the opportunity to escape the domination <strong>of</strong> Europeans and take up<br />

their own lives in an unfettered fashion. Moreover, a central aspect <strong>of</strong> their lives was their spiritual belief<br />

system, and Hidalgo's banner <strong>of</strong> the Virgin <strong>of</strong> Guadalupe had brought out their devotion to this popular<br />

religious icon whose brown skin associated her with the poor. Many believed that they were fighting for the<br />

Virgin <strong>of</strong> Guadalupe against the white devils. One witness remembered that the insignia <strong>of</strong> the Virgin was<br />

everywhere, even on hats and banners.<br />

By October, the number <strong>of</strong> rebels had reached 80,000, and the enthusiastic horde reached the outskirts <strong>of</strong><br />

Mexico City, ready to plunder the largest jewel in the Spanish Empire. As they waited, a Creole-Spanish army<br />

appeared and fired artillery rounds into Hidalgo's irregular army. For reasons unknown to anyone, then or now,<br />

Hidalgo stopped his advance, departing instead to Guadalajara. There, he declared the restoration <strong>of</strong> Indian<br />

7

lands to their communities and the abolition <strong>of</strong> taxes. While garrisoned in Guadalajara, Hidalgo and his army<br />

continued to massacre whites, including the execution <strong>of</strong> 350 prisoners at Hidalgo's request.<br />

Stalled in Guadalajara, the movement began to break apart. The recruits began to leave as mysteriously<br />

as they had appeared a few months before. They removed the Virgin from their hats and went back to their<br />

villages. Without an army, Hidalgo fled to the North with only the remnants <strong>of</strong> his rebellious followers. A<br />

royalist <strong>of</strong>ficer captured Hidalgo in Chihuahua, where he endured a military and ecclesiastical trial. During the<br />

trial, he defended his actions as humanitarian and claimed that he had underestimated the Indians' desire for<br />

Spanish blood. To the Inquisition, he recanted all <strong>of</strong> his previous heresies. The courts defrocked him and<br />

sentenced him to death by firing squad. After three rifle volleys failed to kill him, the commander ordered two<br />

soldiers to walk up to Hidalgo and shoot him in the heart. Hidalgo died on July 30, 1811.<br />

Further reading:<br />

Anna, Timothy, The Fall <strong>of</strong> Royal Government in Mexico, 1988; Hamill, H. M., The Hidalgo Revolt: Prelude to<br />

Mexican Independence, 1966; Krauze, Enrique, Mexico: Biography <strong>of</strong> Power, 1997.<br />

Source:<br />

"Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla." World History: The Modern Era. ABC-CLIO, 2010. Web. 19 Jan. 2010.<br />

.<br />

8

9

Benito Juárez<br />

Despite the limited effectiveness <strong>of</strong> Benito Juárez' reforms, he remained the hero <strong>of</strong> Mexican<br />

nationalism, a leader who weakened colonial practices and created a new Mexico in the mid-19th century.<br />

Juárez was born on March 21, 1806 in San Pablo Guelatao, Oaxaca State. His parents were peasants and<br />

full-blooded Zapotec Indians. They died when Juárez was three years old, and he subsequently lived with an<br />

uncle. Juárez received little education and worked tending his uncle's sheep. One day, he lost one <strong>of</strong> the sheep<br />

and, fearful that his uncle would punish him, ran away to Oaxaca City. There, a Franciscan lay brother<br />

introduced him to books and the ideas that subsequently stirred him to change Mexico.<br />

At one time, Juárez considered entering the priesthood, and toward this end, he studied theology and<br />

<strong>Latin</strong>. In 1829, however, he began pursuing science and law at the Oaxaca Institute <strong>of</strong> Arts and Sciences. Two<br />

years later, he obtained his law degree and won election to the municipal council. As a lawyer, he at first earned<br />

little money, representing mainly the impoverished. By 1843, however, he acquired sufficient finances to marry<br />

into a prominent family.<br />

During the 1840s, Juárez advanced politically and attracted national attention. He became a judge and<br />

then governor <strong>of</strong> Oaxaca State. He criticized the aristocracy and the Catholic Church, with its massive hold on<br />

land, for stifling Mexico, and he supported capitalist growth that would break monopolies and stimulate the<br />

economy. He also desired a federal political system that would give Mexico's states more authority.<br />

By 1853, President Antonio López de Santa Anna had developed a despotic regime, and in 1854, an<br />

uprising began in the nation's southern highlands. Led by Juan Álvarez, the rebels espoused liberal ideas and<br />

demanded a new constitution. Many middle-class mestizos (people <strong>of</strong> Spanish and Indian blood) supported the<br />

rebellion, particularly after the rebels rejected radicalism and issued a moderate declaration for change in 1854.<br />

Juárez' support for this uprising resulted in his exile by Santa Anna. For two years, beginning in 1853, he lived<br />

in New Orleans, where he plotted with fellow exiles. Late in 1855, Juárez returned home and joined the rebel<br />

force that captured Mexico City without a fight and toppled Santa Anna. Álvarez emerged as president and<br />

appointed Juárez minister <strong>of</strong> justice.<br />

Álvarez soon resigned the presidency, and Ignacio Comonfort succeeded him. Juárez and Comonfort<br />

differed on many issues, but the administration pursued a liberal program that Juárez helped shape, including<br />

forcing the church to sell its lands with the intent <strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong>fering them at low prices to the landless. Unfortunately<br />

for the poor, the land was purchased mainly by wealthier Mexicans, and the peasants benefited little.<br />

In yet another reform, a new constitution in 1857 established a federal political system. Elections that year<br />

resulted in a victory for Comonfort, and Juárez became vice president and chief justice <strong>of</strong> the Supreme Court.<br />

Conservatives, however, rebelled against the liberal victory and forced Comonfort to resign, an upset that<br />

10

unleashed a civil war between the conservative government and the liberals, who named Juárez as Mexico's<br />

president.<br />

At first, the army <strong>of</strong> the conservatives gained the upper hand, partly due to funds supplied by the<br />

Catholic Church. In reaction to this, in 1859 Juárez ordered the confiscation <strong>of</strong> all church property not used for<br />

religious services. He also separated church and state and proclaimed religious liberty. As the civil war<br />

continued, Juárez established close ties with the United States that led to charges he was a tool <strong>of</strong> the<br />

<strong>American</strong>s. By 1860, the army <strong>of</strong> the liberals had obtained the advantage, and in December, it entered Mexico<br />

City. Victorious, Juárez presided over all <strong>of</strong> Mexico. He displayed leniency toward the conservative rebels and<br />

allowed full freedom <strong>of</strong> speech. The conservatives took advantage <strong>of</strong> this, severely criticized him, and through<br />

their control <strong>of</strong> Congress nearly removed him from <strong>of</strong>fice.<br />

Juárez' greatest threat, though, entailed the national debt. The nation's treasury was empty, yet Mexico<br />

still owed money to foreign investors. In July 1861, Juárez ordered the suspension <strong>of</strong> payments on the debt,<br />

bringing an angry response from Europeans, including the severing <strong>of</strong> diplomatic relations. France went even<br />

further: with the United States preoccupied by the <strong>American</strong> Civil War, the French government under Emperor<br />

Napoleon III decided to install Archduke Maximilian <strong>of</strong> Austria as Emperor Ferdinand-Joseph Maximilian <strong>of</strong><br />

Mexico. Within a year after French troops invaded in 1862, Juárez was forced to flee Mexico City. The<br />

conservatives hailed Maximilian's arrival, thinking they had a fellow believer, but Maximilian stunned them<br />

when he announced his support for liberal reforms.<br />

This position, however, proved his undoing, for the conservatives deserted him and the liberals<br />

distrusted him. Then, when the <strong>American</strong> Civil War ended, the United States informed France it would not<br />

allow Maximilian's government to continue. Once the French withdrew their troops, Juárez and the liberals<br />

defeated Maximilian and in 1867 executed him. Despite the turmoil, the Maximilian affair boosted Mexican<br />

nationalism when large segments <strong>of</strong> the population united to expel the foreigners.<br />

Unity did not, however, mark Juárez' return to power. He won reelection to the presidency in 1867 but<br />

ruled increasingly without consulting Congress. At the same time, his health deteriorated, and Mexico's<br />

financial situation remained bleak. Juárez angered many liberals with his unilateral approach, his decision to<br />

grant amnesty to the conservatives, and his unsuccessful attempt to alter the constitution and increase executive<br />

power. Furthermore, he angered the army when he reduced its size by two-thirds. In 1871, Juárez ignored<br />

liberal requests that he step aside; he sought reelection and won in voting marred by fraud. One <strong>of</strong> the defeated<br />

candidates, Porfirio Díaz, led an armed revolt, but Juárez crushed it. The president's health, however, worsened,<br />

and he died on July 18, 1872.<br />

Further reading:<br />

Roeder, Ralph, Juárez and His Mexico, 2 vols., 1947; Smart, Charles A., Viva Juárez, 1963; Weeks, Charles A., The Juárez Myth in<br />

Mexico, 1987.<br />

Source:<br />

"Benito Juárez." World History: The Modern Era. ABC-CLIO, 2010. Web. 19 Jan. 2010. .<br />

11

12

Toussaint L'Ouverture<br />

Toussaint L'Ouverture was the dominant figure in the largest slave revolt in the Western hemisphere and<br />

the only one to be fully successful. He rose from enslavement to the military and political leadership <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Haitian struggle for independence within the French Revolution. He abolished slavery and established an<br />

autonomous nation based on the concept that all men should be equal. L'Ouverture became a symbol <strong>of</strong> black<br />

power, dignity, and autonomy, inspiring both those who supported and those who opposed those ideals.<br />

L'Ouverture was born on May 20, 1743, to slave parents on the Breda sugar estate outside <strong>of</strong> Cap<br />

Français, one <strong>of</strong> the leading cities <strong>of</strong> the island colony Saint-Domingue. Tradition holds that his father was once<br />

a chief <strong>of</strong> the West African Arada tribe. Whatever his background, L'Ouverture did not grow into a field hand<br />

but became a domestic worker, probably a coachman. As a child, he had learned various folk and herbal<br />

remedies from his mother and achieved some fame as a healer. At the same time, he was a devout Catholic and<br />

later outlawed voodoo from his armies. By 1779, Toussaint de Breda, as he was known before the revolution,<br />

was a free black growing c<strong>of</strong>fee on rented property with a work force <strong>of</strong> 12 slaves, leased from a wealthy<br />

planter. He learned to read and write when he was about 30, taught by an ex-priest.<br />

During L'Ouverture's youth, Saint-Domingue (present-day Haiti) was the most prosperous <strong>of</strong> France's<br />

colonies. Its economy was based on the plantation and slavery system. More than 3,000 plantations produced<br />

c<strong>of</strong>fee, sugar, cotton, indigo, tobacco, and cocoa. Under the mercantilist system practiced by France, Saint-<br />

Domingue could not develop its own industries but was forced to purchase finished goods from France. All<br />

trade was carried by French ships. Although many planters became fabulously wealthy, they harbored some<br />

resentment against the royal government.<br />

The population on Saint-Domingue comprised three separate groups. Whites held most <strong>of</strong> the power in<br />

the colony; in 1789, they numbered about 45,000 persons. Free blacks or mixed bloods occupied an<br />

intermediate position. Many members <strong>of</strong> this group were wealthy in their own right and owned slaves and<br />

plantations. They were, however, systematically discriminated against by the whites and excluded from real<br />

power in the colony. Free blacks and mulattos totaled about 30,000 persons. Most <strong>of</strong> the population <strong>of</strong> Saint-<br />

Domingue were slaves <strong>of</strong> African descent. Their numbers were approximately 450,000.<br />

The French Revolution began in 1789 and quickly spread to the colonies. On Saint-Domingue, the<br />

whites were divided between those supporting and those opposing the revolution. Free blacks and mulattos also<br />

took sides, and fighting began between the different factions. In Saint-Domingue, the fighting centered around<br />

the idea <strong>of</strong> racial equality, which weakened the control <strong>of</strong> slave owners.<br />

On August 22, 1791, the slaves <strong>of</strong> the Cap Français hinterland rose up in revolt. L'Ouverture apparently<br />

joined the revolt as a doctor. He is said to have saved the lives <strong>of</strong> the Breda plantation manager and his family<br />

early in the revolution. L'Ouverture's first recorded activity with the rebels, however, was on December 4, 1791,<br />

13

when he participated in negotiations between white and black leaders. Negotiations broke down, and the<br />

revolution spread to slaves in other parts <strong>of</strong> the island.<br />

L'Ouverture quickly became chief lieutenant to slave general Biassou, and in 1793, the two men allied<br />

their forces with the Spanish in Santo Domingo on the eastern side <strong>of</strong> the island. As war broke out in Europe<br />

between revolutionary France on the one hand and England and Spain on the other, the latter countries invaded<br />

Saint-Domingue. In those circumstances, many blacks presented themselves as counterrevolutionaries, loyal to<br />

the French king and willing to fight with the Spanish. Tens <strong>of</strong> thousands <strong>of</strong> slaves were mobilized and armed to<br />

fight. In one month, more than 1,000 plantations were burned. To prevent total defeat, the representatives <strong>of</strong> the<br />

revolutionary government in Paris abolished slavery in September 1793.<br />

L'Ouverture quickly changed sides, joining with the French against the Spanish and British, who sought<br />

to continue the institution <strong>of</strong> slavery. He soon became the leading black general for the French and defeated<br />

those <strong>of</strong> his former colleagues who were still allied with the Spanish. Fighting continued until the Treaty <strong>of</strong><br />

Bayle in 1795 ended the war between France and Spain.<br />

By 1796, L'Ouverture was the leading figure on Saint-Domingue. He was named deputy governor and<br />

proved to be an excellent military leader. The French-educated, mulatto class sought to replace the largely<br />

destroyed white class and take control <strong>of</strong> the colony, but L'Ouverture limited them for the most part to the<br />

southern peninsula <strong>of</strong> the island. Many <strong>of</strong> his black <strong>of</strong>ficers took over the abandoned plantations and revived<br />

their production, using compulsory, but paid, labor <strong>of</strong> former slaves.<br />

L'Ouverture used his army and influence with the free blacks to increase the autonomy <strong>of</strong> Saint-<br />

Domingue from France. He engineered the forced return to France <strong>of</strong> various representatives <strong>of</strong> the central<br />

government. He also negotiated a trade agreement with the United States and an agreement with the British to<br />

withdraw their troops and open trade with British colonies.<br />

Supported by Great Britain and the United States, L'Ouverture entered into civil war in July 1799 with<br />

his mulatto counterpart, André Rigaud. The so-called War <strong>of</strong> the South ended with a total victory for<br />

L'Ouverture's blacks over the mulatto class. Yet the violence <strong>of</strong> the war made it impossible for blacks and<br />

mulattos to reunite. By the end <strong>of</strong> 1800, L'Ouverture had also conquered Spanish Santo Domingo, against<br />

orders from Paris. In that and other situations, L'Ouverture displayed increasing independence from the French<br />

government. He promulgated a new colonial constitution that made him governor-general for life. He did not<br />

declare complete independence, however, for fear <strong>of</strong> alienating Britain and the United States and ending their<br />

support. L'Ouverture maintained a strong attachment to French culture. He sent his children to school in France.<br />

He valued education and ability above race. Unqualified blacks who asked for positions were rejected, while his<br />

entourage included three white priests and several white advisers.<br />

In early 1802, Napoleon I sent a military expedition to reassert French control over Saint-Domingue. In<br />

a brief but costly campaign, L'Ouverture was defeated and exiled to France. Many blacks had turned against<br />

14

L'Ouverture during the fighting. Once the campaign ended, however, they quickly realized that the French<br />

planned to reestablish slavery. Under the general and future monarch <strong>of</strong> Haiti, Jean-Jacques Dessalines,<br />

combatants <strong>of</strong> all colors united to expel the French. The colony was declared free on November 29, 1803, and<br />

given the name <strong>of</strong> Haiti to emphasize the break with European colonialism.<br />

The first modern black state was established. Much <strong>of</strong> the credit for laying the groundwork belongs to<br />

L'Ouverture, who demonstrated that blacks were capable <strong>of</strong> self-rule. He never saw the fruit <strong>of</strong> his labors,<br />

however. He died in prison in France on April 7, 1803.<br />

Further reading:<br />

James, C. L. R. The Black Jacobins; Toussaint L'Ouverture and the San Domingo Revolution. 2nd ed. New<br />

York: Vintage Books, 1963; Ott, Thomas O. The Haitian Revolution, 1789–1804. Knoxville: University <strong>of</strong><br />

Tennessee Press, 1973; Parkinson, Wenda. "This Gilded African": Toussaint L'Ouverture. New York: Quartet<br />

Books, 1978; Tyson, George F., Jr., ed. Toussaint L'Ouverture. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1973.<br />

Source:<br />

"Toussaint L'Ouverture." World History: The Modern Era. ABC-CLIO, 2010. Web. 19 Jan. 2010.<br />

.<br />

15

16 <br />

José de San Martín<br />

José de San Martín led the rebellion against Spain that liberated Argentina, Chile, and Peru. This came<br />

after he made an abrupt change in 1812 from commanding Spanish forces to allying with nationalist rebels.<br />

San Martín was born on February 25, 1778 in a small village called Yapeyú, located on the northern<br />

frontier <strong>of</strong> Argentina. His father served as an <strong>of</strong>ficial in the Spanish colonial government that controlled the<br />

area. In 1785, his parents returned to Spain, where they had both been born, and took young José with them. He<br />

attended an aristocratic school, the Nobles' Seminary, in Madrid and began his military career when he entered<br />

the Royal Academy and became a cadet in the Murica infantry regiment. He subsequently fought in battles<br />

against the British and Portuguese and by 1804 advanced to the rank <strong>of</strong> captain. Following this, he fought in the<br />

war between Spain and Napoleonic France.<br />

After Napoleon occupied Spain, San Martín continued to fight for the Spanish Crown, earning<br />

promotion to lieutenant colonel and in 1811 commanding the Sagunto Dragoons. The following year, he made<br />

his puzzling and unexpected transformation, quitting the Spanish military in 1812 and returning to Argentina<br />

where he allied with the rebels in Buenos Aires who demanded independence from Spain. To this day,<br />

historians are uncertain as to why San Martín switched his loyalty; he may have been influenced by a British<br />

agent who sought to undermine Spain, or he may have become disgusted with the prejudice he encountered<br />

from Spaniards who looked down upon him as an inferior Creole, a person <strong>of</strong> Spanish blood born in the<br />

Americas.<br />

Whatever the case, in 1812 he helped found the Lautaro Lodge, a secret organization committed to<br />

independence. He organized Argentine troops against the pro-Spanish royalist forces and in 1813 won an<br />

important battle at San Lorenzo, which secured supply lines with Montevideo. The following year, he was<br />

appointed general and ordered to attack Upper Peru (today, Bolivia). He publicly balked at the impossibility <strong>of</strong><br />

this mission, while privately he concluded that independence from Spain could not be secured without a victory<br />

in Peru, which had become a royalist stronghold. In a skillful maneuver, he resigned his command—claiming ill<br />

health—and requested an obtained appointment as governor <strong>of</strong> Cuyo Province, located near the Andes, where<br />

he could supposedly recuperate. he actually used this move to gather his forces in western Argentina and<br />

develop a plan to cross the Andes into Chile, acquire reinforcements, and attack Peru.<br />

With little support form Buenos Aires, San Martín gathered his men over a three-year period and joined<br />

with the Chilean liberator, Bernardo O'Higgins. Early in 1817, San Martín led his men over the Andes, scaling<br />

incredible heights and fighting Spanish forces in a campaign that enhanced his reputation as a great general.<br />

About this feat, he observed: "The difficulty that had to be overcome in the crossing <strong>of</strong> the mountains can only<br />

be imagined by those who have actually gone through it." In February, he captured Santiago and was <strong>of</strong>fered<br />

the Chilean governorship. He refused, however, so that his friend O'Higgins could rule, a move that also<br />

17

allowed him to secure Chile militarily and prepare for his attack on Peru. In 1818, he defeated the last Royalist<br />

troops in Chile.<br />

San Martín then aimed at Peru. After gathering his force, he departed aboard a ramshackle naval fleet in<br />

1820 and landed at Pisco. Rather than directly assault the heavily fortified capital, Lima, San Martín waited out<br />

his enemy. The Royalist troops failed to get supplies and reinforcements. When they retreated into the<br />

mountains in 1821, San Martín entered Lima. On July 28, the revolutionaries declared Peru independent and<br />

San Martín their nation's protector.<br />

Trouble soon arose, however, for Spanish troops remained in Peru and many Peruvians feared San<br />

Martín's intentions—perhaps he would make himself dictator, weaken the Catholic Church, or destroy the large<br />

landholdings. As disorder threatened, San Martín indeed became dictator, and to defeat the Royalists he decided<br />

to form an alliance with Simón Bolívar, the great South <strong>American</strong> liberator. Bolívar had recently defeated the<br />

Spanish in Venezuela, Colombia, and Ecuador.<br />

In July 1822, the two leaders met at Guayaquil in Ecuador. Little is known about what transpired, but<br />

after two days <strong>of</strong> talks, San Martín unexpectedly returned to his ship and, under the cover <strong>of</strong> darkness, set sail<br />

for Peru. He likely believed it impossible to reconcile his differences with Bolívar, who did not <strong>of</strong>fer him an<br />

adequate number <strong>of</strong> reinforcements and opposed the idea <strong>of</strong> San Martín serving under him in the final assault<br />

against the Spaniards. The two men may also have disagreed over territory, with San Martín opposing Bolívar's<br />

having declared Guayaquil a part <strong>of</strong> Colombia.<br />

In any event, San Martín apparently believed his presence would bring discord and disrupt the war. In<br />

September 1822, he resigned as protector and, while suffering from illness, he traveled to Chile. After his wife<br />

died in 1824, he sailed for England with his daughter and settled in Belgium. In 1829, he decided to return to<br />

Buenos Aires, but when he received news aboard ship that political strife had intensified, he headed back to<br />

Europe without having entered Argentina. He lived in Paris and then Boulogne, where he died on August 17,<br />

1850. The "Liberator <strong>of</strong> the South" eventually returned home: in 1880, his remains were moved to Buenos<br />

Aires.<br />

Further reading:<br />

Metford, John C. J., San Martín: The Liberator, 1950; Mitre, Bartolomé, The Emancipation <strong>of</strong> South America,<br />

1969; Rojas, Ricardo, San Martín: Knight <strong>of</strong> the Andes, 1945.<br />

Source:<br />

"José de San Martín." World History: The Modern Era. ABC-CLIO, 2010. Web. 19 Jan. 2010.<br />

.<br />

18

19

Antonio López de Santa Anna<br />

One <strong>of</strong> Mexico's most influential leaders <strong>of</strong> all time, president and general Antonio López de Santa<br />

Anna directed the Mexican government and military from September 1846 to September 1847, when Mexico<br />

City was seized by Gen. Winfield Scott.<br />

Born in Jalapa in 1794 to a middle-class family, Santa Anna received little schooling before he joined<br />

the Spanish Army in 1810 as a cadet. As a soldier, he helped suppress Indian tribes, public uprisings against the<br />

Roman Catholic Church, and Mexican and U.S. settler uprisings in Texas. His bravery led to recognition and<br />

promotions. As did many other <strong>of</strong>ficers in the Spanish Army, Santa Anna embraced the revolution <strong>of</strong> Augustín<br />

de Iturbide, which resulted in independence from Spain in 1821. Soon afterward, Santa Anna was promoted to<br />

brigadier general and supported the overthrow <strong>of</strong> Iturbide.<br />

In 1829, Santa Anna gained widespread recognition by raising and commanding a 2,000-man army that<br />

defeated a Spanish expeditionary force in 1829 at Tampico. His success at Tampico resulted in his election as<br />

the (liberal) president <strong>of</strong> Mexico in 1833, with Valentín Gómez Farías as vice president. By 1834, mostly for<br />

reasons <strong>of</strong> self-preservation, he adopted a centralist platform, exiled his vice president, shut down Congress, and<br />

declared himself dictator. In 1836, Santa Anna replaced the constitution with the "Seven Laws," which<br />

eliminated self-rule in the states <strong>of</strong> Mexico and lengthened his term to eight years. As dictator, he spent much <strong>of</strong><br />

his time acquiring vast land holdings around Veracruz.<br />

Santa Anna continued to rule with a heavy hand, repressing rebellious cultures in the Yucatán and<br />

Tabasco. In 1836, with an army <strong>of</strong> 6,000 men, he defeated Texan rebels at the Alamo and Goliad, but was badly<br />

beaten by Sam Houston at the Battle <strong>of</strong> San Jacinto, where he displayed poor tactical judgment and a keen<br />

interest in self-preservation. He ultimately signed the Treaties <strong>of</strong> Velasco, which granted Texas its freedom<br />

from Mexico. A few months after his return to Mexico in 1837, Anastasio Bustamante had been chosen as<br />

president by the centralist regime, and Santa Anna retired to his hacienda at Veracruz.<br />

In 1838, Santa Anna was called upon to expel a French force at Veracruz; during the skirmish, he was<br />

wounded by a cannonball, and his left leg was amputated below the knee. The bone was not properly cut, and<br />

he lived with pain for the rest <strong>of</strong> his life. Back in favor, and with the help <strong>of</strong> generals Mariano Paredes y<br />

Arrillaga and Gabriel Valencia, Santa Anna regained the presidency in 1843. His severed leg was disinterred<br />

from his estate at Veracruz and, in a formal military procession, escorted in an urn to the cemetery <strong>of</strong> Santa<br />

Paula, where it was placed in a vault.<br />

In 1844, Santa Anna ordered a levy <strong>of</strong> 30,000 new troops. Under his leadership, the country was nearly<br />

bankrupt through the misuse <strong>of</strong> government funds. Santa Anna's preoccupation with regaining Texas was not<br />

embraced by other Mexican leaders. The political and military arenas grew increasingly unstable, and uprisings<br />

increased. After he left Mexico City to deal with a revolt by former ally Paredes y Arrillaga, Mexico City rioted,<br />

20

and Santa Anna's severed limb was dragged through the streets. Santa Anna was captured in disguise and<br />

imprisoned at Perote Castle until he was exiled to Cuba for life in May 1845.<br />

After discussions between President James K. Polk and Alexander J. Atocha in 1846, and Cmdr.<br />

Alexander Slidell Mackenzie and Santa Anna himself in Cuba, Polk allowed Santa Anna to pass through the<br />

U.S. naval blockade to Veracruz in August 1846. Polk had been assured that Santa Anna would easily regain<br />

the presidency and then seek a negotiated peace. Santa Anna's return at Veracruz was marked by celebratory<br />

cannon discharges and fireworks. In September, he rode into Mexico City in an elegant carriage bedecked with<br />

tricolored ribbons with Valentín Gómez Farías by his side.<br />

Mexico felt momentarily redeemed and hopeful with the return <strong>of</strong> Santa Anna as president. Up to this<br />

point, the war with the United States had gone badly—Gen. Zachary Taylor had won three straight battles,<br />

inflicted terrible losses on the Army <strong>of</strong> the North, and controlled northern Mexico. While Vice President Gómez<br />

Farías ran the day-to-day government, Santa Anna, with his usual energies (and wanton waste <strong>of</strong> funds),<br />

reorganized the Army <strong>of</strong> the North into a 20,000-man army with which he planned to destroy Taylor.<br />

After leaving cheering crowds in San Luis Potosí in late January 1847, Santa Anna returned with his<br />

broken army two months later, having lost the close Battle <strong>of</strong> Buena Vista (La Angostura) and over half the<br />

strength <strong>of</strong> his army. By the time he returned to Mexico City, it was wracked by civil unrest and the Polkos<br />

Revolt, and a U.S. army under Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott had landed without the loss <strong>of</strong> a single man at<br />

Veracruz. To face Scott, Santa Anna rushed to organize the makeshift Army <strong>of</strong> the East, which he personally<br />

led during the bloody defeats that led to the fall <strong>of</strong> Mexico City in September 1847.<br />

Santa Anna resigned as president <strong>of</strong> Mexico on September 16, 1847. After surrendering to U.S. forces at<br />

Puebla, he voluntarily exiled himself in 1848 to Venezuela, where he lived in a comfortable hacienda and<br />

enjoyed his favorite hobby <strong>of</strong> cockfighting.<br />

Mexico, again adrift and leaderless in 1853, asked the aged dictator to return, which he did. Santa Anna<br />

quickly sold the Mesilla Valley to the United States for $10 million (Gadsden Purchase) to generate badly<br />

needed revenue. Overthrown by the liberals in 1855, he left for Havana, Cuba. Allowed to return to Mexico<br />

City in 1874, he died there in 1876 at the age <strong>of</strong> 82.<br />

Further reading:<br />

Calderón de la Barca, Frances Erskine, Life in Mexico, 1982; Callcott, Wilfrid H., Santa Anna, 1936; Costeloe,<br />

Michael P., The Central Republic in Mexico, 1835-1846, 1993; Hanighen, Frank C., Santa Anna, 1934; Olivera,<br />

Ruth R., and Liliane Crete, Life in Mexico under Santa Anna, 1822-1855, 1991; Ruiz, Ramon Eduardo, ed., The<br />

Mexican War, 1963; Santa Anna, Antonio López de, The Eagle, 1967.<br />

Source:<br />

"Antonio López de Santa Anna." World History: The Modern Era. ABC-CLIO, 2010. Web. 19 Jan. 2010.<br />

.<br />

21

22

Pancho Villa<br />

Pancho Villa was one <strong>of</strong> the great revolutionary heroes <strong>of</strong> <strong>Latin</strong> America. A general in the epic struggle<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Mexican Revolution <strong>of</strong> 1910, Villa took on a legendary importance in Mexico for his social ideals and<br />

daring military exploits. Though his actions during the revolution were very real, today he remains a symbol <strong>of</strong><br />

nationalism and social justice easily recognizable to all Mexican people.<br />

Francisco Villa was born Doroteo Arango on June 5, 1878 on a large hacienda in San Juan del Río,<br />

Durango to sharecropper parents. Villa's father died shortly thereafter, and his mother was left to raise five<br />

children. Much <strong>of</strong> Villa's early life is difficult to pinpoint not only because <strong>of</strong> a lack <strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong>ficial records but also<br />

because his later fame engendered many legends about his youth. He was an illiterate ranch hand who witnessed<br />

the abusive labor practices <strong>of</strong> landowners against his family and others <strong>of</strong> their social class. According to<br />

legend, in 1894, Villa entered his home to find his mother trying to prevent the rape <strong>of</strong> his younger sister by a<br />

landowner. After wounding the man, Villa fled to the Durango Mountains as a fugitive. He survived as a bandit<br />

and cattle rustler, roaming and scrounging in the mountains.<br />

In January 1901, Villa was arrested and forcibly inducted into the Mexican Army. A little over a year<br />

later, he deserted, having acquired a good deal <strong>of</strong> military knowledge and skill. Shortly after his desertion, Villa<br />

settled in Parral, Chihuahua, near the Durango border. It was around this time that he took the name <strong>of</strong><br />

Francisco Villa. Opinions differ, but in all likelihood he chose that name because his father was the illegitimate<br />

son <strong>of</strong> a wealthy man named Jesus Villa.<br />

Over the next eight years, Villa continued to live as an outlaw while intermittently finding work as a<br />

laborer for foreign companies. In 1910, Chihuahuan authorities had placed him on the most wanted list,<br />

primarily for the killing <strong>of</strong> Claro Reza, a former bandit companion who had become an informant for the secret<br />

police. An attack on the hacienda <strong>of</strong> a prominent local businessman had also gone unsolved.<br />

On a more momentous level, 1910 was the year that the Mexican Revolution erupted, and Villa <strong>of</strong>fered<br />

his services to Francisco Madero, the liberal politician whose victory in presidential elections had been<br />

cancelled by Porfirio Díaz, the longstanding ruler <strong>of</strong> Mexico. In the early rounds <strong>of</strong> fighting against Díaz, Villa<br />

commanded a company <strong>of</strong> 28 men. The revolutionary forces soon forced the aging Díaz into exile, and Madero<br />

assumed his place as president <strong>of</strong> Mexico. Madero did not, however, alter the structure <strong>of</strong> the national army,<br />

assuming that it would be loyal to him as it had been to Díaz.<br />

Villa served in this army under Mexican general Victoriano Huerta, but a rift soon developed between<br />

the two men, culminating in charges <strong>of</strong> insubordination against Villa. He was sentenced to death but escaped to<br />

the United States, where his exploits during the revolution had attracted considerable attention. In fact, military<br />

advisers to U.S. president Woodrow Wilson urged him to support Villa because they thought Villa would<br />

become "the George Washington <strong>of</strong> Mexico."<br />

23

The revolution was far from over, however, and in 1913, Madero was assassinated as Huerta seized<br />

control <strong>of</strong> the government. Villa returned to Mexico, allying with other revolutionary contingents in the effort to<br />

bring down the Huerta government. Several <strong>of</strong> these leaders commanded armies in the north <strong>of</strong> Mexico.<br />

Venustiano Carranza, a politician from Sonora, proclaimed himself the first chief <strong>of</strong> the Constitutionalists, and<br />

for some time, Villa and his División del Norte were content with the alliance with Carranza.<br />

Villa was a charismatic leader, and the ranks <strong>of</strong> the División del Norte swelled with recruits. Unlike the<br />

guerrilla forces in the Mexican south led by Emiliano Zapata, Villa organized his men as a regular army. Men<br />

on horseback were an important part <strong>of</strong> his forces in the vast arid expanse <strong>of</strong> the Sonoran Desert, but Villa also<br />

pioneered in the use <strong>of</strong> the railroad not only for troop transport but also for hospital services. His men did not<br />

fight for land but rather for pay. Villa was able to finance the army by selling the cattle confiscated from the<br />

large haciendas. Sold across the border in the United States, the revenue from these cattle enabled Villa to buy<br />

guns (also in the United States) and to pay his soldiers.<br />

Huerta was defeated in 1914. With the exile <strong>of</strong> their common enemy, however, the alliances between the<br />

revolutionary armies began to deteriorate. By 1915, Villa had grown impatient with Carranza's growing<br />

conservatism and pretensions to lead the country. Villa faced the forces <strong>of</strong> Carranza led by Alvaro Obregón at<br />

the Battle <strong>of</strong> Celaya. Obregón, familiar with the new tactics <strong>of</strong> defense through machine guns and barbed wire<br />

that were being employed with such devastating effects in World War I, was able to defeat the Villista cavalry<br />

in spite <strong>of</strong> the personal courage <strong>of</strong> Villa and his men. The División del Norte suffered massive losses, and Villa<br />

retreated to Chihuahua, maintaining a precarious control over the local area.<br />

By October 1915, the U.S. government recognized Carranza as its choice to lead Mexico while declaring<br />

Villa an outlaw and ordering an arms embargo. Villa believed that the backing <strong>of</strong> the United States would not<br />

only allow Carranza to consolidate his control <strong>of</strong> the Mexican government but also that Carranza would grant<br />

U.S. leaders the measures they sought to control the Mexican economy and domestic programs. On March 9,<br />

1916, in order to undermine the relations between Carranza and U.S. government leaders, Villa crossed the<br />

border with nearly 600 men and attacked the town <strong>of</strong> Columbus, New Mexico. Seventeen U.S. citizens were<br />

killed in the raid. U.S. president Woodrow Wilson sent an expeditionary force under U.S. general John J.<br />

Pershing into Chihuahua on a punitive mission against Villa.<br />

Even using such new military machinery as tanks, trucks, and planes, the Mexican Expedition failed to<br />

capture or even engage Villa's forces. In Parral on April 2, a skirmish between U.S. soldiers and townspeople<br />

left several more U.S. citizens dead. Two months later, 150,000 troops were on active duty from Texas to<br />

California. Though U.S. leaders had expected that Carranza would remain neutral as they hunted Villa, the<br />

nationalist Carranza could not allow Mexico to be occupied by U.S. troops without losing the support <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Mexican population. Carranza announced that Villa was no longer a threat and formally demanded the<br />

withdrawal <strong>of</strong> the U.S. troops in Mexico, but Wilson refused.<br />

24

On June 18 in the town <strong>of</strong> Carrizal, several more U.S. soldiers were killed and 24 were taken prisoner<br />

when they clashed with townspeople. Wilson threatened full-scale war and delivered an ultimatum to Carranza,<br />

demanding the release <strong>of</strong> the soldiers. Within days, the soldiers were freed. Villa, however, was still at large and<br />

soon captured a number <strong>of</strong> towns previously held by Carranza's forces. The unstable situation continued to<br />

develop, but Pershing's mission was turning into a fiasco. By early 1917, Wilson was forced to negotiate a<br />

settlement with Carranza, ordering the withdrawal <strong>of</strong> U.S. troops from Mexico in spite <strong>of</strong> the fact that Villa was<br />

never captured.<br />

By this time, Villa was a tremendously popular hero. Common people in the North had believed<br />

throughout the revolution that Villa had their interests at heart, and his conduct in their towns during the years<br />

<strong>of</strong> war reinforced this idea. His great victories early in the revolution added to his reputation, and his defiance <strong>of</strong><br />

the U.S. Army sealed his fate as a character <strong>of</strong> legend.<br />

In 1920, after the assassination <strong>of</strong> Carranza, Villa struck a deal with the new government under recently<br />

elected Mexican president Obregón. In exchange for a 25,000-acre hacienda in Durango, Villa ended his armed<br />

struggle and retired from politics. In addition, his men were given land and one year's military pay. Villa the<br />

landowner remembered the experiences <strong>of</strong> Villa the farmhand. He instituted a number <strong>of</strong> progressive agrarian<br />

measures on his property. He studied the U.S. techniques <strong>of</strong> contour plowing and crop rotation and founded a<br />

bank that made loans to farmers at low interest rates. Villa also provided a school for the children living on the<br />

hacienda. The management <strong>of</strong> his property mirrored some <strong>of</strong> the aspirations he had harbored for his country.<br />

On the morning <strong>of</strong> July 20, 1923, Villa was en route to a christening in Parral when he and five<br />

companions were shot to death by seven gunmen. Several days later, Jesus Salas Barraza, a local politician, said<br />

he had planned the killing in retaliation for "Villa's many crimes." Most Mexicans believed, however, that the<br />

order had come from high-level government <strong>of</strong>ficials.<br />

In 1976, Villa's remains were transferred from Durango to the Monument <strong>of</strong> the Revolution in Mexico City as<br />

the current government struggled to rouse support for itself by asserting its origins in the revolution. For most<br />

Mexicans, however, the importance <strong>of</strong> Villa has less to do with government monuments than with the old<br />

photographs, movies, and songs that keep his legend alive.<br />

Further reading:<br />

Harris, Larry, Pancho Villa: Strong Man <strong>of</strong> the Revolution, 1989; Herrera, Celia, Pancho Villa Facing History,<br />

1993; Katz, Frederick, The Life and Times <strong>of</strong> Pancho Villa, 1998; O'Brien, Steven, Pancho Villa, 1994.<br />

Source:<br />

"Pancho Villa." World History: The Modern Era. ABC-CLIO, 2010. Web. 19 Jan. 2010.<br />

.<br />

25

26

Emiliano Zapata<br />

According to legend, Emiliano Zapata, a tenant farmer in Mexico, began his revolutionary crusade after<br />

he noticed the discrepancy between the decrepit housing in which he lived and the luxurious stables maintained<br />

for his master's horses. Wearing a sombrero, his face adorned by a drooping black mustache, Zapata rallied the<br />

peasants and emerged as a charismatic revolutionary hero.<br />

Zapata was born on August 8, 1879 in Anenecuilco, Mexico to poor parents <strong>of</strong> Spanish and indigenous<br />

Indian blood. In his youth, he worked as a tenant farmer on a sugar plantation and witnessed the injustice <strong>of</strong><br />

wealthy landowners—those who had large estates, or haciendas—continuously expanding their holdings by<br />

confiscating peasant land. Zapata refused to stand for this and organized the peasants in his village to protest,<br />

which resulted in his arrest. After his imprisonment, Zapata served briefly in the army and then trained horses<br />

for a wealthy landowner. In 1909, he led a group <strong>of</strong> peasants in another protest; they forcibly occupied land<br />

recently claimed by an owner <strong>of</strong> a hacienda.<br />

By this time, Mexico had reached a crisis. Since the late colonial period, with the revolutionary uprising<br />

led by José María Morelos, and continuing through the independence years <strong>of</strong> Augustín de Iturbide and Benito<br />

Juárez, the nation had been in almost constant turmoil. In particular, the economic gulf between a wealthy few<br />

and the impoverished masses produced great tension. This situation resulted in the Mexican Revolution <strong>of</strong> 1910,<br />

characterized by disjointed rebellions that shook the countryside. That year, one <strong>of</strong> the rebels, Francisco<br />

Madero, overthrew the dictatorship <strong>of</strong> Porfirio Díaz. In the fight between Madero and Díaz, Zapata raised an<br />

army to support Madero, a moderate democratic reformer.<br />

Madero soon disappointed Zapata, however. When the mustachioed rebel demanded that Madero arrange for<br />

land to be returned to the peasants, the incoming president refused and insisted that Zapata and his followers lay<br />

down their arms. Zapata considered doing this but decided against it after Madero's army attacked his men.<br />

Thus, Zapata continued fighting—attacking haciendas and government <strong>of</strong>ficials and building a larger<br />

following among the peasants. In 1911, he issued the Plan <strong>of</strong> Ayala that called for Madero's overthrow and<br />

promised democracy and a redistribution <strong>of</strong> land. Two years later, Madero's regime collapsed, partly because <strong>of</strong><br />

the disorder promoted by Zapata and other rebel leaders, including Pancho Villa and Victoriano Huerta, who<br />

were each fighting their own battles.<br />

In February 1913, Huerta captured the presidency and established a dictatorship. A conservative, he had<br />

no desire to redistribute land or establish democracy, and the United States intervened by supporting his<br />

overthrow. Zapata now fought Huerta and gained control <strong>of</strong> the area south <strong>of</strong> Mexico City. In the territory he<br />

ruled, he confiscated the haciendas, redistributed land to the poor, and established an organization to provide the<br />

farmers with credit; observers who traveled through the area noted that the peasants worshipped Zapata and that<br />

27

order prevailed. Zapata's military tactics confounded his opponents. He used guerrilla warfare, and <strong>of</strong>tentimes<br />

the peaceful-looking peasant farmers became, at an instant's notice, rifle-wielding fighters.<br />

In July 1914, Huerta's government fell, and Venustiano Carranza became Mexico's ruler. He refused to<br />

adopt Zapata's agrarian reform and found himself battling both Zapata in the south and Villa in the north. In<br />

November, representatives <strong>of</strong> Carranza, Villa, and Zapata met in Aguascalientes, trying but failing to reach an<br />

agreement. Carranza soon fled Mexico City for Veracruz, and Villa and Zapata alternately occupied the capital.<br />

While turmoil prevailed, Zapata's peasant followers did not loot the city but instead solicited food.<br />

As Villa gained the advantage in the fighting, Zapata agreed late in 1914 to cooperate with him.<br />

Carranza's generals developed superb battlefield tactics, however, and the dictator developed reform programs<br />

that appealed to the disadvantaged, issuing decrees that gave them unused lands owned by the national<br />

government and that protected industrial workers. By the spring <strong>of</strong> 1915, Carranza had put both Villa and<br />

Zapata on the defensive.<br />

In late 1916, Carranza oversaw a constitutional convention—closed to Villa and Zapata. The<br />

Constitution <strong>of</strong> 1917 was a radical document that gave the government the right to restrict private property in<br />

order to more equitably distribute the nation's wealth; it also outlawed child labor and stipulated the eight-hour<br />

work day. Although Carranza did not personally care about these provisions other than as a means to<br />

consolidate his power, the 1917 constitution appealed to many reformers and deflated Zapata's revolutionary<br />

movement.<br />

On April 10, 1919, Mexican colonel Jesús Guajardo arranged a meeting with Zapata and then ambushed<br />

and killed him. Thus ended Zapata's revolutionary campaign, one that raised social issues to prominent heights<br />

and pressured Carranza into radical reforms that reshaped Mexico and would continue under Lázaro Cárdenas.<br />

Mexicans remember Zapata as a revolutionary hero—his influence is so great that in 1994, more than 70 years<br />

after his death, a sizable revolutionary movement in Chiapas State called itself the Zapatista National Liberation<br />

Army.<br />

Further reading:<br />

Brunk, Samuel, Emiliano Zapata: Revolution and Betrayal in Mexico, 1995; Parkinson, Roger, Zapata, 1975;<br />

Womack, John, Zapata and the Mexican Revolution, 1969.<br />

Source:<br />

"Emiliano Zapata." World History: The Modern Era. ABC-CLIO, 2010. Web. 19 Jan. 2010.<br />

.<br />

28

29

Che Guevara<br />

First serving alongside Fidel Castro as one <strong>of</strong> the leaders <strong>of</strong> the Cuban Revolution, Che Guevara became<br />

the most recognizable face <strong>of</strong> guerrilla warfare and revolution <strong>of</strong> the 20th century, his death promoting him to<br />

mythical status among students and radical youth worldwide.<br />

Ernesto Guevara de la Serna was born on May 14, 1928 in Rosario, Argentina, the first <strong>of</strong> Ernesto<br />

Guevara Lynch and Celia Guevara de la Serna's five children. (Che is a nickname commonly used in Argentina<br />

to address friends; the Cuban exiles he met later in Central America thus referred to him always as "Che.") In<br />

May 1930, after swimming with his mother in a river north <strong>of</strong> the city, Guevara developed a cough that would<br />

turn into asthmatic bronchitis. His asthma would affect him for the rest <strong>of</strong> his life. The family moved to Alta<br />

Gracia, in the province <strong>of</strong> Córdoba, realizing that only a dry climate would help his development. The family<br />

struggled as a result <strong>of</strong> fluctuating incomes, yet they could not move for fear that their son's health might<br />

worsen. Despite his ill health, Guevara was outgoing, rebellious, and accomplished on the sports field, even if<br />

his grades did not reflect his intelligent mind.<br />

Guevara's first political lessons probably came during the mid- to late 1930s when the family took in<br />

relatives escaping the Spanish Civil War. Guevara's father headed the local aid committee for the Spanish<br />

Republic and befriended the republican refugees who came to Alta Gracia. In early 1943, the family moved to<br />

the city <strong>of</strong> Córdoba, where Guevara was already attending the Colegio Nacional Deán Funes. When he<br />

graduated in 1946, the same year that Juan Perón assumed the presidency <strong>of</strong> Argentina, Guevara took a job with<br />

the National Department <strong>of</strong> Roads in Córdoba while the family moved back to Buenos Aires.<br />

Following the death <strong>of</strong> his grandmother, Guevara also moved to Buenos Aires and began studying<br />

medicine. At the allergy clinic <strong>of</strong> Dr. Pisani, he moved quickly from patient to unpaid research assistant when<br />

the renowned doctor recognized his potential. During his vacations, Guevara traveled extensively throughout<br />

Argentina, first hitchhiking and then by motorized bicycle. In January 1952, he set <strong>of</strong>f on a motorcycle with a<br />

childhood friend, intent on journeying northward as far as the United States. They scrounged for food and<br />

passed themselves <strong>of</strong>f as leprologists in order to gain renown. On his return to Buenos Aires and medical<br />

school, Guevara wrote that, "Vagabonding through our 'America' has changed me more than I thought." He<br />

continued working in Pisani's clinic and studying for the 14 exams he had left to finish medical school.<br />

Rather than settle down as a doctor, however, Guevara set <strong>of</strong>f on another journey north. In Ecuador, he<br />

joined with travelers en route to Guatemala to witness the attempts <strong>of</strong> Jacobo Arbenz Guzmán to challenge the<br />

might <strong>of</strong> the United States and the United Fruit Company by instituting land reform. Before he visited<br />

Guatemala, Guevara showed no more than a superficial interest in political events either in Argentina or in<br />

<strong>Latin</strong> America as a whole. His eight months in Guatemala occasioned an ideological formation that extended<br />

beyond simple anti-imperialism. He seemed to enjoy the threat <strong>of</strong> confrontation, which may explain much <strong>of</strong><br />

30

Guevara's revolutionary spirit. He wrote home that the events <strong>of</strong> the coup gave him a "magical sense <strong>of</strong><br />

invulnerability."<br />

Guevara also met his first wife in Central America, Hilda Gadea, an exiled Peruvian activist. They were<br />

married on August 18, 1955 in Mexico. The collapse <strong>of</strong> the Guatemalan regime during the U.S.-influenced<br />

invasion from Honduras convinced Guevara <strong>of</strong> the need for armed struggle to accompany any radical reform. In<br />

Mexico, Guevara returned to medical research, and in the hospital in which he worked, he met a Cuban exile,<br />

Ñico López, whom he had met in Guatemala. Soon he met Raúl Castro Ruz and, in the summer <strong>of</strong> 1955, Raúl's<br />

brother Fidel.<br />

Fidel Castro was in exile in Mexico but was determined to return to Cuba and triumph over the regime<br />

<strong>of</strong> dictator Fulgencio Batista. Guevara wrote that after his experiences in <strong>Latin</strong> America, and especially in<br />

Guatemala, "It wasn't hard to talk me into joining any revolution against a tyrant, but Fidel impressed me as an<br />

extraordinary man . . . I shared in his optimism." The two men quickly developed a deep respect and fondness<br />

for one another, a bond that strengthened during their detention in a Mexican immigration center after the<br />

militants' plans to invade Cuba were discovered by the authorities. On February 15, 1956, Guevara's daughter,<br />

Hilda Beatriz, was born.<br />

On November 25, Guevara left by boat, the Granma, for Cuba and revolution, his marriage to Hilda<br />

Gadea all but over. The journey took longer than expected, and government forces were awaiting the group. A<br />

small cadre, including Guevara and both Castros, survived the attack and made its way to the Sierra Maestra<br />

mountain range in eastern Cuba. The group survived through 1957, Guevara continually battling his asthma,<br />

and in 1958, began guerrilla attacks on Batista's troops. Batista's repressive measures against suspected<br />

supporters <strong>of</strong> Castro only intensified opposition to the regime and won support for the guerrillas. Guevara<br />

gained a reputation as an efficient and egalitarian leader and one <strong>of</strong> the most ideologically radical members <strong>of</strong><br />

the movement. During the guerrilla phase <strong>of</strong> the revolution, Guevara would also meet his second wife, Aleida<br />

March, a militant who would become his constant companion and collaborator. They married on June 2, 1959<br />

and eventually had four children together.<br />

On January 1, 1959, the revolutionaries marched into Havana in victory. Soon after the triumph,<br />

however, Guevara's asthma returned, and he was confined to bed. He stayed at the seaside, in Tarará, where he<br />

continued to work. There, he took decisions on agrarian reform, consolidated his alliance with the communist<br />

Popular Socialist Party, formulated plans for the new armed forces, and drafted his most famous book, Guerrilla<br />

Warfare. Guevara believed that land reform was crucial in order to destroy the political power <strong>of</strong> the oligarchy,<br />

reorient the economy away from its dependence on sugar, and allow peasants to produce staple foods.<br />

Diversification and industrialization became the catch phrases.<br />

Guevara soon assumed the role <strong>of</strong> minister <strong>of</strong> industry within the National Institute <strong>of</strong> Agrarian Reform.<br />

Perhaps due to political differences, Castro sent Guevara on a trip to Africa and Asia three days later. He<br />

31

eturned in September to take charge <strong>of</strong> the National Bank and to oversee the expropriation <strong>of</strong> Cuba's sugar<br />

mills, the island's most important industry. In protest, U.S. president Dwight D. Eisenhower suspended sugar<br />

purchases from Cuba. Guevara turned to the Soviet Union, and Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev promised to<br />

buy the U.S. quota. The Soviet Union also provided the oil that Cuba was no longer able to obtain from the U.S.<br />

Time magazine referred to Guevara as the brain <strong>of</strong> the revolution, Fidel as its heart, and Raúl as its fist.<br />

Guevara loved his life in Cuba but had never lost his desire to fight for socialism abroad or to export the<br />

revolution to other <strong>Latin</strong> <strong>American</strong> countries. He talked <strong>of</strong> going to Vietnam and did spend time in the Congo<br />

during 1965, but his main focus was <strong>Latin</strong> America. He had dispatched a reconnaissance party to Argentina in<br />

1963, and in 1966, he went to Bolivia. It was not the same country he had visited in 1953. Land reform had<br />

quieted the peasant sector and political reform gave participation to labor unions, leaving the left divided and<br />

weak. The Bolivian Communist Party was allied to the Soviet Union, which was opposed to Cuba spreading<br />

revolution and expected that Guevara would only be passing through Bolivia to Argentina. Betrayed by political<br />

opponents, deserters, and poor planning and communications, Guevara's forces were unable to gain support<br />

from the local population and fell prey to the Bolivian military and the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency. In<br />

October 1967, the guerrillas were captured.<br />

On October 9, 1967, Guevara was shot by his captors in a schoolhouse in Vallegrande, Bolivia. In order<br />

to prove to the world that he was dead, his executioners took pictures <strong>of</strong> his corpse and severed his hands for<br />

identification purposes. They did not kill the legend that resurfaced within a year, however, as images <strong>of</strong><br />

Guevara occupied posters and T-shirts around the world.<br />

Further reading:<br />

Anderson, Jon Lee, Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life, 1997; Castañeda, Jorge G., Compañero: The Life and<br />