English - Europe's World

English - Europe's World

English - Europe's World

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

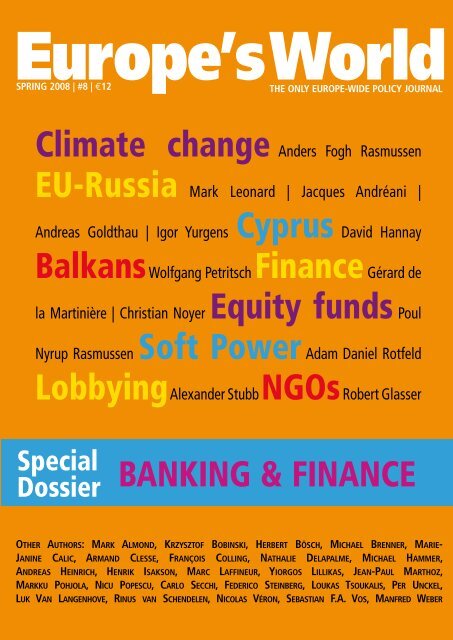

Europe’s<strong>World</strong><br />

SPRING 2008 | #8 | 12<br />

THE ONLY EUROPE-WIDE POLICY JOURNAL<br />

Climate change Anders Fogh Rasmussen<br />

EU-Russia Mark Leonard | Jacques Andréani |<br />

Andreas Goldthau | Igor Yurgens Cyprus David Hannay<br />

Balkans Finance Wolfgang Petritsch Gérard de<br />

Equity funds la Martinière | Christian Noyer Poul<br />

Soft Power Nyrup Rasmussen Adam Daniel Rotfeld<br />

Lobbying NGOs Alexander Stubb Robert Glasser<br />

Special<br />

Dossier<br />

BANKING & FINANCE<br />

OTHER AUTHORS: MARK ALMOND, KRZYSZTOF BOBINSKI, HERBERT BÖSCH, MICHAEL BRENNER, MARIE-<br />

JANINE CALIC, ARMAND CLESSE, FRANÇOIS COLLING, NATHALIE DELAPALME, MICHAEL HAMMER,<br />

ANDREAS HEINRICH, HENRIK ISAKSON, MARC LAFFINEUR, YIORGOS LILLIKAS, JEAN-PAUL MARTHOZ,<br />

MARKKU POHJOLA, NICU POPESCU, CARLO SECCHI, FEDERICO STEINBERG, LOUKAS TSOUKALIS, PER UNCKEL,<br />

LUK VAN LANGENHOVE, RINUS VAN SCHENDELEN, NICOLAS VÉRON, SEBASTIAN F.A. VOS, MANFRED WEBER

HOW EUROPE'S WORLD HARNESSES THE INTERNET<br />

It was a distinguished and very experienced<br />

Agence France Presse journalist who first<br />

described as “highly original” the Europe’s<br />

<strong>World</strong> policy of combining the printed version of<br />

the journal with an electronic one that is sent to a<br />

few hundred thousands of people. More recently,<br />

our idea of making its entire content available<br />

free on-line to as many potential readers as<br />

possible was greeted by Carlo De Benedetti, the<br />

Italian industrialist-turned-publishing tycoon as<br />

“intelligent and interesting”.<br />

Debate still rages as fiercely as ever in the<br />

world of media and journalism over how best<br />

to reconcile the information revolution with the<br />

hard commercial realities of publishing. It’s a<br />

real headache for newspapers and magazines to<br />

know how to make money out of the internet.<br />

But for newcomers like Europe’s <strong>World</strong> it’s been<br />

a no-brainer. Because this journal is published<br />

on behalf of a large coalition of think-tanks<br />

with the aim of creating a Europe-wide debate<br />

on key issues, the internet has offered us an<br />

unparalleled opportunity to reach out to the<br />

political elites of some 171 countries, both<br />

within the EU and further afield.<br />

The 60-plus think-tanks and civil society bodies<br />

that make up this journal’s Advisory Board are<br />

all closely connected to the political movers<br />

and shakers in their own country. That is why<br />

Europe’s <strong>World</strong> is able to count a readership of<br />

over 100,000, and still climbing!<br />

Hard-nosed commercial publishers continue<br />

to have major problems with free on-line<br />

readerships. But for this journal, with its ambition<br />

of becoming the pre-eminent European platform<br />

for new thinking and original policy ideas, the<br />

goal is to add as many more readers as we can.<br />

In line with this, we want to issue the following<br />

invitation to universities and other interested<br />

parties: Get in touch with us and we’ll send<br />

electronic copies of Europe’s <strong>World</strong> to as many<br />

potential readers as you wish. Once we have<br />

the e-mail details of students, faculty members<br />

and other contacts with a strong interest in<br />

policymaking, we’ll ensure that they receive each<br />

issue as soon as it’s published.<br />

In the 30 months since its launch, Europe’s<br />

<strong>World</strong> has surpassed all expectations. It attracts<br />

thoughtful contributions from some of Europe’s<br />

foremost politicians – in this issue we not<br />

only feature an article by Denmark’s current<br />

prime minister, but also one by his immediate<br />

predecessor – and by acknowledged experts<br />

from around the world.<br />

The breadth of issues dealt with in our pages<br />

reflects the widening reach of EU-level decisionmaking.<br />

It seems to us, as Editor and Publisher of<br />

Europe’s <strong>World</strong>, that it is more essential than ever<br />

that we should strive towards creating Europewide<br />

consensus on so many different topics. We<br />

hope this journal makes a useful contribution to<br />

this process.<br />

Giles Merritt<br />

Editor<br />

Geert Cami<br />

Publisher<br />

Spring 2008 Europe’s <strong>World</strong> | 1

2 | Europe’s <strong>World</strong> Spring 2008

TABLE OF CONTENTS<br />

Section<br />

1 INTERNATIONAL<br />

■ Europe’s chance to become a global climate champion<br />

by Anders Fogh Rasmussen .................................................. 10<br />

■ How Europe is starting to set global rules by Adam Daniel Rotfeld ............. 15<br />

■ A five-point strategy for EU-Russia relations by Mark Leonard and Nicu Popescu .. 20<br />

■ The reasons Europe has so disappointed Putin’s Russia by Jacques Andréani .... 31<br />

■ Russia’s energy weapon is a fiction by Andreas Goldthau<br />

Commentary by Andreas Heinrich. ............................................. 36<br />

■ Forget politics; What Russia and the EU need is a shared economic space<br />

by Igor Yurgens ............................................................ 43<br />

■ Latin America is Europe’s next big missed business opportunity by Carlo Secchi<br />

Commentary by Federico Steinberg ............................................ 48<br />

■ While America electioneers, Europe has a Middle East role to play<br />

by Michael Brenner. ........................................................ 55<br />

■ European foreign policy begins with the neighbours by Loukas Tsoukalis ....... 59<br />

Further contributions to this section by Bernd Kaussler (Iran), Christa Meindersma (Afghanistan), Alexandros<br />

Petersen and James Rogers (Atlantic pact), can be found on www.europesworld.org<br />

Section<br />

2 EUROPE<br />

■ The case for urgently re-starting talks on Cyprus by David Hannay<br />

Commentary by Yiorgos Lillikas ............................................... 66<br />

■ Why the EU may never get its accounts straight by François Colling<br />

Commentary by Herbert Bösch ................................................ 72<br />

■ The EU must speed-up its Western Balkans enlargement by Wolfgang Petritsch<br />

Commentary by Marie-Janine Calic. ............................................ 80<br />

■ Why Turkey may turn its back on Europe by Mark Almond..................... 87<br />

■ The dangers to the EU of condemning Ukraine and Belarus to political limbo<br />

by Krzysztof Bobinski ....................................................... 92<br />

■ Europe badly needs a Nordic-style “knowledge policy” by Per Unckel.......... 97<br />

■ Finding a new EU Budget mechanism won’t be easy by Marc Laffineur ........ 103<br />

■ It’s time Europe stopped crying “foul” to justify its protectionism<br />

by Henrik Isakson ......................................................... 107<br />

■ This enlargement mess by Armand Clesse ................................... 110<br />

■ Power to the regions, but not yet farewell to the nation state<br />

by Luk Van Langenhove .................................................... 113<br />

Further contributions to this section by Simon Anholt (Europe’s image), Maria Dunin–W sowicz (eurozone), Derek<br />

Marshall and Tim Williams (defence industry), Jozias van Aartsen (energy policy), can be found on www.europesworld.org<br />

POLICY DOSSIER: BANKING AND FINANCE ......................... 117<br />

■ Taming the private equity fund “locusts” by Poul Nyrup Rasmussen<br />

Commentary by Sebastian F.A. Vos ....................................... 130<br />

■ How the EU is banking on decentralisation by Christian Noyer .......... 133<br />

■ Credit crunch pushes cross-border watchdogs high on EU agenda<br />

by Nicolas Véron ..................................................... 135<br />

Spring 2008 Europe’s <strong>World</strong> | 3

4 | Europe’s <strong>World</strong> Spring 2008

Section<br />

TABLE OF CONTENTS<br />

■ We’ve got to do something about Europe’s crazy patchwork of<br />

bank supervisors by Markku Pohjola ................................... 139<br />

■ Pitfalls that Europe’s booming insurance industry must sidestep<br />

by Gérard de la Martinière ............................................. 142<br />

■ What Europe’s future financial marketplace will look like<br />

by Manfred Weber .................................................... 144<br />

A further contribution to this section by Manfred Jäger (ECB), can be found on www.europesworld.org<br />

3 THE DEVELOPING WORLD<br />

■ Why we need to look hard at the NGOs’ flaws by Robert Glasser<br />

Commentary by Michael Hammer ............................................. 150<br />

■ Regulating Brussels’ legion of lobbyists by Alexander Stubb<br />

Commentary by Rinus van Schendelen. ........................................ 156<br />

■ Bush's legacy will be NGOs with a truly global vision by Jean-Paul Marthoz.... 162<br />

■ Developing a new Euro-Africa partnership by Nathalie Delapalme............. 169<br />

Section<br />

4 VIEWS FROM THE CAPITALS<br />

Disgruntled Austrians ignore EU’s economic benefits by Sonja Puntscher Riekmann . . 175<br />

How the EU underpinned peace in Ireland by Etain Tannam .................... 176<br />

Nostalgia appeal could brighten Lithuania’s dismal political landscape<br />

by Mantas Adom nas ........................................................ 178<br />

Portugal’s EU presidency success masks worsening domestic unease<br />

by António Figueiredo Lopes .................................................. 179<br />

One year after EU accession, Romanians still resist anti-corruption efforts<br />

by Sabina Fati. .............................................................. 182<br />

Reciprocal respect could calm the troubled waters of EU-Russia relations<br />

by Fyodor Lukyanov ......................................................... 186<br />

Fickle Swedes are turning on their government – again by Anders Mellbourn.... 187<br />

Despite EU reverses, Turkey’s AK Party walks tall by Beril Dedeo lu............. 189<br />

Iron law of EU politics makes Britain a poor European by John Peterson ........ 191<br />

LETTERS TO THE EDITOR<br />

From Adam Ficsor, Marija Pej inovi Buri , Helga Trüpel, Marko Mihkelson, Arjen Berkvens,<br />

Alan Dukes, Angelika Beer, Jamila Madeira, Ruth Thompson, Romana Jordan Cizelj, Anneli<br />

Jäätteenmäki, Cem Özdemir, Lena Ek, Hans van Baalen .......................... 194<br />

FORUM FOR DEBATE<br />

From Constantinos Eliades, Emma Nicholson .................................... 214<br />

Spring 2008 Europe’s <strong>World</strong> | 5

EUROPE’S WORLD EDITORIAL BOARD<br />

The Editorial Board of Europe’s <strong>World</strong> gives the journal a truly European breadth and balance.<br />

Its ranks include senior journalists and political and business figures.<br />

MIGUEL ANGEL AGUILAR<br />

El País columnist<br />

BARON DANIEL JANSSEN<br />

Former Chairman of the Board of Solvay<br />

GIAMPIERO ALHADEFF<br />

Secretary General of the European Parliamentary<br />

Labour Party<br />

CARL BILDT<br />

Swedish Foreign Minister<br />

JORGO CHATZIMARKAKIS MEP<br />

Member of the European Parliament’s Committee<br />

on Industry, Research and Energy<br />

PAT COX<br />

Former President of the European Parliament<br />

JOSEF JOFFE<br />

Publisher-Editor of the German weekly newspaper<br />

Die Zeit<br />

SANDRA KALNIETE<br />

Former Latvian Minister of Foreign Affairs and<br />

a former EU Commissioner for Agriculture and<br />

Fisheries<br />

GLENYS KINNOCK MEP<br />

Member of the European Parliament’s Committee<br />

on Development<br />

PASCAL LAMY<br />

Director General of the <strong>World</strong> Trade Organization<br />

VICOMTE ETIENNE DAVIGNON<br />

Vice President of Suez-Tractebel and President of<br />

Friends of Europe<br />

PHILIPPE LE CORRE<br />

Lecturer at the Institut d'Etudes Politiques and the<br />

Institute of Oriental Studies in Paris.<br />

JEAN-LUC DEHAENE MEP<br />

Former Belgian Prime Minister<br />

ANNA DIAMANTOPOULOU<br />

Member of the Greek National Parliament and a<br />

former EU Commissioner for Employment and<br />

Social Affairs<br />

MIA DOORNAERT<br />

Diplomatic Editor of the Belgian daily newspaper<br />

De Standaard<br />

MONICA FRASSONI MEP<br />

Co-President of the Green Group in the European<br />

Parliament<br />

JEAN-DOMINIQUE GIULIANI<br />

President of the Robert Schuman Foundation<br />

BRONISLAW GEREMEK MEP<br />

Former Polish Foreign Minister<br />

MIKE GONZALEZ<br />

Editor of the Wall Street Journal-Asia<br />

ROBERT GRAHAM<br />

Ambassador-at-large of the Financial Times<br />

TOOMAS HENDRIK ILVES<br />

President of the Republic of Estonia<br />

ROBERT MANCHIN<br />

Founder and Managing Director of the Gallup<br />

Organisation Europe<br />

PASQUAL MARAGALL I MIRA<br />

Former President of the Generalitat de Catalunya<br />

JOHN MONKS<br />

General Secretary of the European Trade Union<br />

Confederation (ETUC)<br />

MARIO MONTI<br />

President of the Università Bocconi and a former<br />

EU Commissioner for Competition<br />

DORIS PACK MEP<br />

Chairwoman of the European Parliament’s<br />

Delegation for relations with the countries of<br />

south-east Europe<br />

CHRIS PATTEN<br />

Chancellor of Oxford University and a former EU<br />

Commissioner for External Relations<br />

ANTÓNIO VITORINO<br />

Former EU Commissioner for Justice and Home<br />

Affairs<br />

JORIS VOS<br />

President, European Union and NATO Relations at<br />

Boeing International<br />

GILES MERRITT<br />

Editorial Board Chairman and Secretary General<br />

of Friends of Europe<br />

6 | Europe’s <strong>World</strong> Spring 2008

Europe’s <strong>World</strong> is published three times yearly in partnership with Friends of Europe, Gallup and the Robert<br />

Schuman Foundation / Editor: Giles Merritt / Sub-editors: Keith Colquhoun, Rowena House / Matters of opinion<br />

Editor: Katharine Mill / Publisher: Geert Cami / Publication Manager: Julie Bolle / Editorial Coordinator:<br />

Hendrik Roggen / Advertising:Design & Production: Brief-Ink<br />

/ Address:<br />

E-mails: For suggestions of topics and authors or for letters to the Editor: editorial@europesworld.org; for advertising rates<br />

and bookings: advertise@europesworld.org; to get a subscription to the printed version: subscriptions@europesworld.org.<br />

Europe’s <strong>World</strong> is available free online: http://www.europesworld.org<br />

Index to Partners and Advertisers:<br />

<br />

Alstom p.4<br />

Belgian Ministry of Foreign Affairs p.212<br />

Boeing<br />

Inside front cover<br />

Brussels Airlines p.34<br />

Chamber of Commerce and Industry<br />

<br />

<br />

EFG Eurobank p.116<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

Generalitat de Catalunya p.200-201<br />

Government of the Republic<br />

<br />

<br />

Invest Macedonia<br />

p.100-102<br />

<br />

<br />

La Poste, International Mail Activities p.174<br />

<br />

<br />

Polish Oil and Gas Company PGNiG p.2<br />

Robert Schuman Foundation p.46<br />

<br />

<br />

Slovenia’s Ministry of the Environment<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

Volvo<br />

p.166-167<br />

Europe’s <strong>World</strong> authors contribute in their personal capacities, and their views do not necessarily reflect those<br />

of the institutions they represent or of Europe’s <strong>World</strong> and its Advisory Board and Editorial Board members.<br />

Reproduction in whole or in part is permitted, provided that full attribution is made to Europe’s <strong>World</strong><br />

(including mention of our website: www.europesworld.org) and to the author(s).<br />

Spring 2008 Europe’s <strong>World</strong> | 7

1<br />

Section<br />

INTERNATIONAL<br />

Europe’s chance to become<br />

a global climate champion<br />

With less than two years to go until the crucially<br />

important UN climate change talks in Copenhagen in<br />

late 2009, Denmark’s Prime Minister Anders Fogh<br />

Rasmussen assesses Europe’s chances of making a real<br />

difference on global warming<br />

The Kyoto Protocol was a landmark<br />

in the global fight against climate<br />

change and it has been the main<br />

reference point for international debate<br />

on the subject for years. However, the<br />

first commitment period to fulfil pledges<br />

to cut greenhouse gas emissions between<br />

2008 and 2012 only came into force a few<br />

months ago. For the next four years, those<br />

countries that ratified the protocol will be<br />

busy delivering on their binding promises.<br />

Meanwhile, the political debate has moved<br />

on – and rightly so. Kyoto was crucial, but it<br />

was only a first step. According to scientific<br />

evidence compiled by the International Panel<br />

on Climate Change, it will require strenuous<br />

efforts well beyond the Kyoto horizon of<br />

2012 to limit temperature increases to 2o<br />

Celsius. This is now widely recognised. With<br />

Europe promising to lead the way beyond<br />

Kyoto, the eyes of the world will be on the<br />

Europe Union in 2008 to see how effective a<br />

lead we will take.<br />

It is right that the world should be looking<br />

to the EU for leadership. Europe shares<br />

responsibility for the world’s current climate<br />

problems, accounting for approximately<br />

14% of global carbon dioxide emissions.<br />

Cutting European emissions will make a<br />

substantial contribution towards worldwide<br />

efforts to reduce carbon levels – even<br />

10 | Europe’s <strong>World</strong> Spring 2008

though it cannot reverse global warming by<br />

itself. The EU also has good reason to act.<br />

Not only have we made commitments to<br />

the rest of the world, but we have a strong<br />

self-interest in combating climate change.<br />

Europeans are no strangers to extreme<br />

weather phenomena such as drought, forest<br />

fires and floods.<br />

What, then, will the EU’s role<br />

be post-Kyoto? First, we need<br />

to ensure broader international<br />

participation in efforts to<br />

reduce carbon emissions. Kyoto<br />

was ratified by 175 countries,<br />

but this apparently impressive<br />

figure tends to exaggerate the<br />

impact of the protocol. Only<br />

31 of the countries (Annex 1<br />

Parties to the United Nations<br />

Framework Convention on<br />

Climate Change) that ratified<br />

it are committed to cutting<br />

greenhouse gases by some 5% below 1990<br />

levels by 2012. These 31 countries together<br />

represented less than 25% of global CO 2<br />

emissions from fuel combustion in 2005.<br />

The Kyoto Protocol was not ratified by the<br />

US, until recently the largest carbon-emitting<br />

country in the world. Nor does the protocol<br />

bind certain major emerging economies –<br />

including China, India and Brazil – to any<br />

specific reductions. In reality, therefore, Kyoto<br />

only addressed a limited part of the problem,<br />

despite its great political significance.<br />

This fundamental limitation is aggravated<br />

still further when projections about future<br />

carbon emissions are taken into account.<br />

The 31 countries that accepted CO 2 targets<br />

under Kyoto are projected to account<br />

The people of<br />

Europe will expect<br />

the EU to deliver on<br />

its promises. Failure<br />

would risk alienating<br />

EU citizens from<br />

European institutions<br />

and may even harm<br />

the very concept of<br />

the Union<br />

for less than 15% of the world’s fuelcombustion<br />

carbon dioxide emissions by<br />

2030. The first requirement of a post-Kyoto<br />

agreement, therefore, is to make sure it is<br />

truly global, with participation of all major<br />

emitting economies.<br />

Winning the battle against climate change<br />

will require all major industrialised countries<br />

to share a vision about the<br />

need for deep emission cuts<br />

and a global understanding<br />

that everyone will be made<br />

to contribute; the world<br />

has a responsibility to<br />

act in common. However,<br />

it is equally clear that<br />

different countries will<br />

have different degrees of<br />

responsibility, according<br />

to their respective levels<br />

of economic development.<br />

The 1992 United Nations<br />

Framework Convention on Climate Change,<br />

for example, talked about a “common but<br />

differentiated responsibility” for combating<br />

global warming. This principle remains<br />

fundamental to the process of reaching a<br />

new global consensus.<br />

In the struggle against global warming,<br />

the people of Europe will expect the EU to<br />

take a lead and to deliver on its promises.<br />

Failure would risk alienating EU citizens from<br />

European institutions and may even harm<br />

the very concept of the Union. Likewise,<br />

the world will look to Europe to push<br />

the international agenda forward and to<br />

demonstrate that it is possible to cut carbon<br />

emissions while also maintaining welfare<br />

spending and economic growth.<br />

Spring 2008 Europe’s <strong>World</strong> | 11

Time is short. According to the timetable<br />

confirmed at the UN climate conference in<br />

Bali in December 2007, efforts to agree a new<br />

ambitious global accord will reach an initial<br />

peak in Poznan, Poland, next December and<br />

will culminate at the scheduled<br />

Copenhagen UN Climate<br />

Change Conference one year<br />

later. Thus December 2009<br />

is the deadline for reaching<br />

a post-Kyoto arrangement<br />

that will effectively engage all<br />

major emitting countries in<br />

the global effort to combat<br />

man-made climate change. Europe is deeply<br />

involved in this process and has already<br />

set the world an example by agreeing post-<br />

Kyoto carbon reduction targets. In March<br />

2007, the European Council agreed EU<br />

emissions would be cut by 30% below 1990<br />

levels by 2020 as its contribution to a global<br />

and comprehensive agreement.<br />

However, Europe’s legitimacy as a global<br />

leader on climate change will simply not<br />

depend on setting targets; the EU will have<br />

to deliver on them too. This year will witness<br />

painful negotiations on the Commission’s<br />

proposal for burden sharing, hopefully<br />

with an agreement in place later this year.<br />

Europe will also explore and develop flexible<br />

market instruments to widen the potential<br />

for emission reductions. The EU is ideally<br />

placed to push market mechanism forward;<br />

we are currently embarking on a second<br />

generation carbon emission trading scheme.<br />

Much was learnt from the first phase and the<br />

second-stage centralised scheme should<br />

both improve market efficiency in the EU and<br />

pave the way for global emission trading.<br />

This year will witness<br />

painful negotiations<br />

on the Commission’s<br />

proposal for burden<br />

sharing<br />

The EU should also demonstrate to the<br />

world that tackling climate change is not just<br />

about making negative choices. Global warming<br />

creates opportunities too, with new lowcarbon<br />

technologies and production methods<br />

able to increase industrial<br />

competitiveness and economic<br />

growth. Denmark, for example,<br />

has achieved 70% growth<br />

since the early 1980s without<br />

increasing energy consumption<br />

and while transferring 15% of<br />

overall energy production to<br />

renewable sources. During this<br />

period, Denmark has created one of the most<br />

competitive economies in the world. Thus<br />

the development of eco-friendly technologies,<br />

renewable energy and energy efficiency<br />

technology is not only part of the answer to<br />

the climate challenge, it is also an important<br />

source of jobs and wealth creation. This<br />

positive outlook is shared at the European<br />

level, where climate and energy are one of<br />

four priority areas for the EU’s growth and<br />

employment strategy. We must continue to<br />

set the world an example and show that<br />

climate change is not an obstacle to economic<br />

expansion but also a part of the solution<br />

Making an economic success out of<br />

the climate challenge will, however, require<br />

continued investments in research and<br />

development and a sustained push for<br />

innovation. Also, if we are to ensure the<br />

necessary up-take of new climate-friendly<br />

technologies, we will have to promote and<br />

invest in energy-efficient buildings, make the<br />

right long-term investment decisions about<br />

transport and energy and develop the right<br />

mix of green instruments. This will require<br />

12 | Europe’s <strong>World</strong> Spring 2008

an effective and ambitious framework. This<br />

framework must strive to make Europe<br />

the world’s testing ground for the green,<br />

market-based energy solutions of tomorrow.<br />

Member states do not lack imagination in<br />

this regard; lots of initiatives are already<br />

being taken in the pursuit of greener energy.<br />

We need to tap into each other’s best ideas<br />

and turn them into winning solutions for us<br />

all. Thus we need to increase cooperation<br />

on technology, research and development,<br />

diffusion and transfer of technologies.<br />

While the EU must set the pace on clean<br />

technologies and market instruments, we<br />

should also make sure that we adapt our<br />

policies towards third countries. The EU<br />

is already a world leader in development<br />

assistance and in funding the Clean<br />

Development Mechanism under the Kyoto<br />

Protocol; this is one area we will have<br />

to pay particular attention to in future.<br />

Most developing countries only contribute<br />

marginally to greenhouse gas emissions,<br />

but they are particularly vulnerable to<br />

MATTERS OF OPINION<br />

In the South, EU public opinion is hotting up on climate change<br />

The plethora of news reports concerning, what<br />

<br />

weather events around the world have propelled the<br />

issue of climate change high up the agenda. In a<br />

recent Eurobarometer survey, carried out by The<br />

Gallup Organization, nearly nine out of 10 Europeans<br />

admitted that they were worried about climate<br />

change and global warming. Fifty percent said they<br />

<br />

“some degree” of concern.<br />

Interestingly, some of the countries in southern Europe<br />

– Greece, Spain, Cyprus and Malta – were the most<br />

concerned; the Scandinavians, Poles, Latvians and<br />

Estonians were the least worried. Somewhat surprisingly,<br />

given their low-lying situation, Dutch people were one of<br />

the least likely EU countries to be “very concerned”.<br />

Most Europeans say<br />

EU should take the lead and<br />

promote clean energy<br />

Twice as many people believed that measures to deal<br />

with energy issues should be decided at the EU rather<br />

<br />

Europe setting minimum targets for the share of<br />

renewable energy in Member States. Twice as many<br />

<br />

should be reduced from its current one-third share of<br />

energy supply, compared to those who believed it<br />

<br />

ARE YOU CONCERNED ABOUT CLIMATE<br />

CHANGE?<br />

% answering yes<br />

> 50%<br />

24%<br />

31% - 50%<br />

< 31%<br />

30% 20%<br />

24%<br />

50%<br />

48% 28% 32%<br />

40% 47%<br />

53%<br />

48% 41%<br />

55%<br />

45%<br />

51% 64%<br />

58% 53%<br />

40%<br />

65% 70%<br />

68%<br />

37% 34%<br />

Source: Eurobarometer 2007<br />

68%<br />

70%<br />

Spring 2008 Europe’s <strong>World</strong> | 13

the impact of climate change. Severe<br />

weather threatens food production, fragile<br />

ecosystems and scarce water resources,<br />

and therefore jeopardises our efforts to<br />

alleviate poverty and reach the millennium<br />

development goals. These dangers need<br />

to be systematically reflected in our choice<br />

of policies and programmes, and efforts to<br />

mitigate climate effects must be given much<br />

more prominence.<br />

The post-Kyoto period is already well<br />

underway. The EU has set itself an immense<br />

challenge as a world leader in the fight<br />

against climate change. Together with the<br />

US and other advanced economies, the EU<br />

will have to shoulder responsibility for a<br />

significant slice of the necessary carbon<br />

reductions while also maintaining economic<br />

growth. We will also have to assist developing<br />

countries to play their part and help them to<br />

adapt to the adverse effects of climate<br />

change which are already under way. This<br />

will be one of the greatest challenges for the<br />

EU in the years to come – one that will have<br />

a direct bearing on perceptions of the EU,<br />

both among Europe’s citizens and worldwide.<br />

We have the means and the responsibility to<br />

act. In the months and years ahead, we in<br />

the EU must demonstrate that we are up to<br />

the task.<br />

Anders Fogh Rasmussen is Denmark’s Prime Minister.<br />

<br />

E.W. ADVISORY BOARD MEMBERS<br />

Confrontations Europe is a<br />

European “think-tank” that brings<br />

together people of different<br />

political leanings and experiences:<br />

company managers, trade<br />

unionists, politicians, academics,<br />

students, key players from associations and the political scene.<br />

Its main objective is to revive public debate and to contribute to<br />

better citizen information. Its members endeavour to share an<br />

analysis of globalisation and major changes, and on this basis,<br />

to better imagine the possible options available for necessary<br />

reforms in France and in Europe. In order to share our analysis<br />

and better understand the European construction, you can<br />

subscribe for 38 euros to our publications : a monthly newsletter<br />

(Interface), a trimestrial magazine (La Lettre de Confrontations<br />

Europe) and bi-yearly (The Option).<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

For more information : confrontations@wanadoo.fr;<br />

www.confrontations.orgu<br />

14 | Europe’s <strong>World</strong> Spring 2008

How Europe is starting to set<br />

global rules<br />

With its Reform Treaty, the European Union becomes<br />

a new animal, more than an organisation but less<br />

than a state, says Adam Daniel Rotfeld, a former<br />

foreign minister of Poland. He argues that its soft<br />

power strategy has helped to make Europe secure and<br />

prosperous, but asks how it should develop<br />

The European Union is a success story.<br />

Europe’s achievements have to be<br />

seen not as a single act or chain of<br />

spectacular consecutive EU summits, but as<br />

a historical process. Almost 50 years ago,<br />

the political scientist Karl Deutsch defined a<br />

concept of a pluralistic security community<br />

based on the following principles: the<br />

sovereignty and legal independence of<br />

states; the compatibility of core values<br />

derived from common institutions; mutual<br />

responsiveness, identity and loyalty;<br />

integration to the point that states entertain<br />

“dependable expectations of peaceful<br />

change” and communication cementing<br />

political communities. As it turns out,<br />

the EU today reflects these elements of<br />

a universal pluralistic security community<br />

much more than any other international<br />

and multilateral security institution.<br />

A few months ago the College of Europe<br />

in Natolin, near Warsaw, Sweden’s foreign<br />

minister Carl Bildt rightly said: “Our Europe<br />

has never been as free, as prosperous or as<br />

secure as it is today. And never really means<br />

never – never in its entire history.”<br />

Recognition of this simple fact has<br />

to be our point of departure for further<br />

deliberation on the adequacy of “soft”<br />

security instruments when confronting<br />

Europe’s contemporary requirements and<br />

risks. Since Europe is now more secure than<br />

in its entire history, it seems legitimate to<br />

ask: “If so, why have so many Europeans<br />

been so disappointed for so many<br />

years?” One could perhaps argue that the<br />

higher their expectations, the deeper the<br />

disappointment. But the reality has been,<br />

as we know, that each successive round<br />

of EU-level reform has without exception<br />

generated tension and frustration.<br />

Former Italian prime minister Lamberto<br />

Dini, in his foreword to MEP Andrew Duff’s<br />

1997 book on the Amsterdam treaty, said<br />

that “the long night of Amsterdam closed on<br />

a note of bitter disappointment”. He went on<br />

to explain: “We could have blocked everything<br />

Spring 2008 Europe’s <strong>World</strong> | 15

in Amsterdam. We refrained from doing so<br />

because a pause for reflection would not have<br />

sufficed to overcome the stalemate… Better<br />

to adopt the disappointed but lucid attitude<br />

suggested by Altiero Spinelli after the Single<br />

Act – to consolidate what we have obtained<br />

and set sail again for the next<br />

objective.” Europe’s security<br />

and defence culture is much<br />

better suited to soft rather<br />

than hard security issues.<br />

For the past two decades,<br />

institutional reforms have<br />

worked better than they<br />

are given credit for. The EU<br />

has gradually enhanced its<br />

decision-making mechanisms by moving more<br />

areas to qualified majority voting (QMV), and by<br />

streamlining its institutions. New mechanisms<br />

have emerged in such areas as a common<br />

foreign and security policy (CFSP), and have<br />

gradually created space for themselves in<br />

the Union’s institutional set-up. Failures have<br />

had more to do with inadequate political<br />

leadership and the lack of determination to<br />

move more decisively towards QMV, as well as<br />

the EU’s continuing dilemma over how to close<br />

its distance from the citizen. Opportunities for<br />

political leadership have been weakened by<br />

the complexities of the institutional triangle,<br />

and the emphasis on unanimity has slowed<br />

decision-making in such key areas as justice<br />

and home affairs and taxation. Nor have the<br />

citizens always been properly consulted on<br />

draft legislation or on the overall objectives of<br />

the Union, and member states have had very<br />

different track records.<br />

Differentiated integration has come<br />

up against an instinct for uniformity and<br />

The Reform Treaty<br />

is the rejected<br />

constitutional treaty<br />

minus, but the minus<br />

isn’t very big. If it<br />

walks like a dog and<br />

barks like a dog,<br />

then it is a dog<br />

cohesion in the EU. Although the UK retains<br />

its opt-out/opt-in reservations Denmark is<br />

planning to give up its opt-outs. Constructive<br />

abstention over CFSP has not been given the<br />

benefit of the doubt. Flexibility and enhanced<br />

cooperation were the subject of much<br />

attention in the Amsterdam<br />

and Nice intergovernmental<br />

conferences, but not much<br />

has been done to put them<br />

into practice. At the same<br />

time, some initiatives taken<br />

outside the treaty framework<br />

have been successful. Almost<br />

all the recommendations<br />

of the “praline summit” in<br />

November 2003 to discuss<br />

EU states different views on the Iraq war<br />

have been implemented. Provisions of the<br />

Prüm convention on cross-border policing<br />

are now generally accepted. The idea that<br />

some should lead and others follow remains<br />

a source of inspiration for the future.<br />

Now we have the Reform Treaty signed<br />

in Lisbon. This is the rejected constitutional<br />

treaty minus, but the minus isn’t very big. If<br />

it walks like a dog and barks like a dog, then<br />

it is a dog. The treaty aims to transform the<br />

Union into an international organisation<br />

and grant it legal personality. In my view,<br />

the Union is much more than a classical<br />

international organisation; It is a new animal<br />

that is more than an organisation and less<br />

than a state.<br />

The treaty says that the Union will act<br />

only within the limits conferred upon it by<br />

member states. The Union has always acted<br />

on the basis of conferred competence, and<br />

stating that obvious fact more explicitly<br />

16 | Europe’s <strong>World</strong> Spring 2008

eflects the continuing unease in some states<br />

over the very principle of supranational<br />

integration. Such a statement could wrongly<br />

give the impression of an identity crisis, were<br />

it not for the volume of innovations that<br />

were transferred largely unchanged from the<br />

constitutional treaty.<br />

The role of national<br />

parliaments is enhanced,<br />

the subsidiarity mechanism<br />

reinforced, and the double<br />

majority voting system is<br />

being implemented. The title<br />

“minister of foreign affairs” in<br />

the rejected constitution has<br />

been dropped, so the CFSP<br />

is still in charge of the “high<br />

representative”.<br />

It is an open<br />

question whether<br />

the values shared<br />

by NATO and the<br />

EU, along with<br />

the concept of<br />

soft power, are<br />

compatible with the<br />

ambitions of the<br />

United States<br />

the member state presidencies is another<br />

area where improvements might be needed.<br />

The composition of the Commission, where<br />

traditionally there is a lot of creativity and fresh<br />

thinking, will attract attention. Governance<br />

inside the eurozone will also be the subject of<br />

further discussions if, as seems<br />

likely, it offers a basis for more<br />

advanced integration.<br />

Reducing the scope of<br />

qualified majority voting will<br />

remain a major objective,<br />

possibly focusing on financial<br />

matters. The procedure for<br />

amending a treaty, at present<br />

requiring ratification by all<br />

member states, will also need<br />

to be explored further.<br />

That still leaves the question of how the<br />

EU’s common and security policy will shift<br />

from rhetoric to action? Karl von Wogau,<br />

president of the European Parliament’s subcommittee<br />

on defence, has rightly noted:<br />

“The main challenge we face is not to<br />

rewrite the European security strategy, but to<br />

implement what we have already agreed.”<br />

Looking ahead, governance issues are<br />

likely to be subject of review as the innovations<br />

of the Reform Treaty are tested in practice.<br />

The double-hatted high representative of the<br />

Union for foreign affairs and security policy<br />

could be a model for use elsewhere in the<br />

institutional architecture. A more ambitious<br />

double-hatting exercise would be one in<br />

which the president of the European Council<br />

serves at the same time as the president of<br />

the Commission. Interaction between the<br />

new permanent president of the Council and<br />

The Union is likely to be spared a new wave<br />

of reform in the near future, but from 2010<br />

onwards the pressures will grow for reviewing<br />

the existing provisions. New revision treaties<br />

could deal with selected issues, and hence be<br />

easier to agree on and ratify.<br />

Constructing a new international order<br />

based on multilateralism is neither a choice<br />

nor an alternative, but a necessity. Henry<br />

Kissinger believes that the United States<br />

should be aware of its superiority, yet should<br />

act as if it were functioning in a world where<br />

security depends on numerous other centres<br />

of power. “In such a world”, Kissinger has<br />

written, “the United States will find partners<br />

not only for sharing the psychological<br />

burdens of leadership, but also for shaping an<br />

international order consistent with freedom<br />

and democracy” Such a new centre of power<br />

is constituted by the EU.<br />

Spring 2008 Europe’s <strong>World</strong> | 17

18 | Europe’s <strong>World</strong> Spring 2008

It was Kissinger who asked the famous<br />

question about Europe’s phone number. That<br />

was many years ago, but not much has changed<br />

since. Under the rejected constitution, there<br />

would have been a foreign affairs minister.<br />

Javier Solana would probably have got the job,<br />

and under the Reform Treaty could still get it,<br />

though without the title. Zbigniew Brzezinski,<br />

who like Kissinger is a former big wheel in<br />

American foreign policy, wants Europeans to<br />

overcome their “parochialism”. “A genuine<br />

US-EU transatlantic alliance, based on a shared<br />

global perspective, must be derived from a<br />

similarly shared strategic understanding of the<br />

nature of our era, of the central threat that the<br />

world faces, and of the role and mission of the<br />

west as a whole,” he has said.<br />

But it is an open question whether the<br />

values shared by NATO and the EU, along<br />

with the concept of soft power, are compatible<br />

with the ambitions of the United States. In<br />

his book The European Dream, American<br />

author Jeremy Rifkin praises Europe for<br />

offering “diversity, quality of life …<br />

sustainability, universal human rights, the<br />

rights of nature, and peace on Earth.” He<br />

concluded, “We Americans used to say that<br />

the American Dream is worth dying for. The<br />

new European Dream is worth living for”.<br />

Adam Daniel Rotfeld is a former Polish Foreign<br />

Minister. <br />

E.W. ADVISORY BOARD MEMBERS<br />

Luxembourg Institute for<br />

European<br />

and International Studies<br />

21 rue Philippe II<br />

L-2340 Luxembourg<br />

Phone: +352 466580<br />

Fax: +352 466579<br />

E-mail: armand.clesse@ieis.lu<br />

Web: www.ieis.lu<br />

Presided by Javier Solana, the Madariaga European<br />

Foundation was created in 1998 by former students of<br />

the College of Europe to practically develop the potential<br />

represented by the College’s capacity for insightful reflection<br />

and analysis into European issues. The Foundation bears the<br />

name of the College of Europe founder: Spanish writer,<br />

historian, diplomat and philosopher Salvador de Madariaga<br />

(1886-1978).<br />

MEF is an independent operating foundation dedicated to<br />

promoting innovative thinking on the role and responsibilities<br />

of the EU in an era of global challenges. Acting as a platform<br />

for dialogue between public and private actors, civil society<br />

and academia, the Foundation currently specialises in<br />

developing projects on Conflict Prevention. In parallel<br />

to its project-oriented activities, MEF pursues an active<br />

information and communication strategy for a deeper<br />

understanding of major European issues stake.<br />

Spring 2008 Europe’s <strong>World</strong> | 19

A five-point strategy for<br />

EU-Russia relations<br />

The EU badly needs a new approach<br />

in its dealings with resurgent Russia,<br />

write Mark Leonard (far left) and<br />

Nicu Popescu. They set out the five<br />

broad elements of a fresh European<br />

strategy<br />

Russia’s parliamentary elections<br />

in December not only confirmed<br />

President Vladimir Putin’s position<br />

as the ‘father of the nation’ but further<br />

weakened the European Union’s leverage<br />

over a resurgent and increasingly assertive<br />

Russia. The election also marked a series<br />

of indirect humiliations for the EU, ranging<br />

from the Russian government’s refusal to<br />

grant visas to OSCE election observers<br />

to the successful bid for a Duma seat<br />

(and immunity from prosecution) by Andrei<br />

Lugovoi, the former intelligence officer<br />

suspected by the British authorities of the<br />

poisoning in London of Alexander Litvinenko.<br />

Putin’s crushing victory – together with<br />

the anointment of Gazprom vice-chairman<br />

Dimitri Medvedev as his successor – have<br />

confirmed what most EU officials have long<br />

known: the EU’s strategy for democratising<br />

Russia is now officially dead.<br />

In the 1990s, EU member states coalesced<br />

around a strategy of democratising and<br />

westernising a weak and indebted Russia,<br />

and managed to get the Russians to sign<br />

up to all major international standards on<br />

democracy and human rights. Btu since<br />

then, soaring oil and gas prices have made<br />

the Russian governing elite incredibly<br />

powerful, less cooperative and, above all,<br />

less interested in joining the west. The old<br />

strategy is increasingly out of synch with<br />

the realities of the new Russia. Although<br />

the EU is a far bigger power than Russia<br />

in conventional terms – its population is<br />

three and a half times the size of Russia's,<br />

its military spending ten times bigger, its<br />

economy 15 times the size of Russia’s<br />

– Europeans are increasingly finding that<br />

Russia is setting the terms of the relationship<br />

between the two blocs.<br />

While not reproducing the ideological<br />

divisions of the cold war, Russia seems to be<br />

setting itself up as an ideological alternative<br />

to the EU, with a different approach to<br />

sovereignty, power and world order. Where<br />

the European project is founded on the<br />

rule of law and multilateralism, Moscow<br />

believes that laws are a mere expression<br />

of power, and that when the balance of<br />

power changes, laws should be changed<br />

unilaterally if needed to reflect it. In recent<br />

20 | Europe’s <strong>World</strong> Spring 2008

years, Moscow has tried to revise the<br />

terms of commercial deals with western<br />

companies, military agreements such as the<br />

Conventional Forces in Europe Treaty, and<br />

even breached diplomatic codes of conduct<br />

like the Vienna Convention.<br />

These trends are not just<br />

a pre-electoral ritual, but a<br />

consolidated and widely<br />

accepted desire in Russia<br />

to revise the whole set of<br />

agreements with the EU.<br />

Moscow is also challenging<br />

another aspect of the EU’s<br />

world view – its belief that<br />

security is built through interdependence.<br />

The Kremlin’s<br />

philosophy of “sovereign<br />

democracy”, however, has<br />

led it to try to decrease its reliance on the<br />

European Union, while trying to increase<br />

the EU’s dependence on Russia. This quest<br />

for “asymmetric inter-dependence” is a tool<br />

of power projection rather than stability.<br />

The Kremlin has deployed a powerful mix<br />

of charm and aggression to divide and rule<br />

EU member states – so that it can deal<br />

with each member state individually from<br />

a position of strength. On the one hand,<br />

it has reached out and flattered several<br />

member states – in particular the big ones<br />

– signing long-term bilateral energy deals<br />

and exchanging state visits. On the other,<br />

Russia has picked bilateral disputes with 11<br />

member states so far on issues ranging from<br />

Polish meat to Finnish timber which have<br />

had an equally adverse impact on EU unity.<br />

The European Union’s response to<br />

December’s parliamentary elections<br />

Although the EU<br />

is far bigger – its<br />

population is three<br />

and a half times<br />

the size, its military<br />

spending ten times<br />

bigger, its economy<br />

15 times the size<br />

– Russia is setting<br />

the terms of the<br />

relationship<br />

EU-RUSSIA<br />

followed a pattern of division and confusion<br />

that have plagued its Russia policy in recent<br />

years. Even though the elections were<br />

denounced by parliamentarians from the<br />

Council of Europe and the OSCE, different<br />

EU governments gave out<br />

very mixed messages. It took<br />

three days for the Portuguese<br />

EU presidency to release a<br />

statement on the arrest of<br />

opposition activists such as<br />

Garry Kasparov – and once<br />

published it was withdrawn<br />

and replaced by a milder<br />

version. After the poll, the<br />

EU issued a mildly-worded<br />

statement about “election<br />

irregularities”, while strong<br />

condemnation by Germany<br />

and Poland was cancelled<br />

out by French President Nicolas Sarkozy’s<br />

congratulatory telephone call to Putin.<br />

The conventional wisdom is that relations<br />

with Russia have deteriorated as a result<br />

of the 2004 enlargement which imported<br />

a hostile, anti-Russian bloc into the EU.<br />

But while it is true that the relationship<br />

with Russia has become the most divisive<br />

factor within the EU since Donald Rumsfeld<br />

divided member states into “new” and “old”<br />

Europe – it is wrong to see the main dividing<br />

line between the EU’s eastern and western<br />

member states.<br />

In a comprehensive “power audit” of<br />

the EU-Russia relationship published last<br />

November, the European Council on Foreign<br />

Relations commissioned experts from all<br />

27 member states to examine the bi-lateral<br />

relationship between their own country and<br />

Spring 2008 Europe’s <strong>World</strong> | 21

Russia. We identified five distinct policy<br />

approaches to Russia shared by old and<br />

new members alike: “Trojan Horses” (Cyprus<br />

and Greece) who often defend Russian<br />

interests in the EU system, and are willing<br />

to veto common EU positions; “Strategic<br />

Partners” (France, Germany, Italy, Spain)<br />

who enjoy a “special relationship” and<br />

whose governments have built special<br />

bilateral relationships with Russia, which<br />

occasionally cuts against the grain of<br />

common EU objectives in areas such as<br />

energy and the EU Neighbourhood Policy;<br />

“Friendly Pragmatists” (Austria, Belgium,<br />

Bulgaria, Finland, Hungary, Luxembourg,<br />

Malta, Portugal, Slovakia, and Slovenia) who<br />

maintain a close relationship with Russia<br />

and tend to put their business interests<br />

above political goals; “Frosty Pragmatists”<br />

(Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Ireland,<br />

Latvia, the Netherlands, Romania, Sweden<br />

and the United Kingdom) who also focus<br />

on business interests but are less afraid<br />

than others to speak out against Russian<br />

behaviour on human rights or other issues;<br />

“New Cold Warriors” (Lithuania and Poland)<br />

who have an overtly hostile relationship with<br />

Moscow and are willing to use the veto to<br />

block EU negotiations with Russia.<br />

Broadly speaking, the EU is split between<br />

two approaches – and each of the five<br />

groups tends towards one of the main policy<br />

paradigms. At one end of the spectrum<br />

are those who view Russia as a potential<br />

partner that can be drawn into the EU’s orbit<br />

through a process of “creeping integration”.<br />

They favour involving Russia in as many<br />

institutions as possible and encouraging<br />

Russian investment in the EU's energy sector,<br />

even if Russia sometimes breaks the rules.<br />

At the other end are member states who see<br />

and treat Russia as a threat. According to<br />

them, Russian expansionism and contempt<br />

for democracy must be rolled back through<br />

a policy of “soft containment” that involves<br />

excluding Russia from the G-8, expanding<br />

NATO to include Georgia, supporting anti-<br />

Russian regimes in the neighbourhood,<br />

building missile shields, developing an “Energy<br />

NATO”, and excluding Russian investment<br />

from the European energy sector.<br />

Both approaches have obvious<br />

drawbacks, making them unpalatable to<br />

a majority of EU member states. The first<br />

approach would give Russia access to all<br />

the benefits of co-operation with the EU<br />

without demanding that it abides by stable<br />

rules. The other approach – of open hostility<br />

– would make it hard for the EU to draw on<br />

Russia’s help to tackle a host of common<br />

problems in the European neighbourhood<br />

and beyond.<br />

The EU badly needs a new approach to<br />

deal with the new Russia. Ultimately, this<br />

fragmentation of EU power does not serve<br />

the strategic interests of any of these five<br />

groups. No single country can shape the EU’s<br />

Russia policy on their own, and the different<br />

approaches end up cancelling each other<br />

out. No single EU government is influential<br />

enough with Russia to withstand bilateral<br />

pressures, or to push Moscow to implement<br />

existing commitments and deals. This was<br />

shown aptly by Russia’s recent attempt to<br />

revise some of its energy deals with friendly<br />

states, such as Bulgaria and Germany.<br />

While the EU’s long-term goal should still<br />

be to have a liberal democratic Russia as a<br />

22 | Europe’s <strong>World</strong> Spring 2008

EU-RUSSIA<br />

neighbour, a more realistic mid-term goal<br />

would be to encourage Russia to respect the<br />

rule of law, which would allow it to become<br />

a reliable partner.<br />

The rule of law is central to the European<br />

project, and its weakness in Russia is a concern<br />

for businesses who worry about respect of<br />

contracts, diplomats who fear breaches of<br />

international treaties, human rights activists<br />

concerned about authoritarianism, and defence<br />

establishments who want to avoid military<br />

tensions. If EU leaders manage to unite around<br />

a common strategy, they will be able to use<br />

many points of leverage to reinforce it.<br />

The first element of this would be a<br />

conditional engagement with Russia. This will<br />

MATTERS OF OPINION<br />

Support for Putin not as solid as the recent elections suggest<br />

Russians returned President Putin’s United Russia<br />

party to government last December, with almost<br />

two-thirds of the votes, in elections that were widely<br />

seen as a referendum on Putin’s policies after eight<br />

years in power.<br />

But polls carried out by Gallup before Putin dissolved<br />

the government, in April and May 2007, showed<br />

that Russians were divided over their government’s<br />

performance. While four out of 10 said they approved<br />

of the government’s performance, almost the same<br />

<br />

<br />

or a good job.<br />

Western observers were critical of irregularities<br />

in the December ballot, with the Organisation<br />

<br />

the Council of Europe describing the results as<br />

“unfair”. This would seem to support unease<br />

among Russia’s voters noted by the Gallup survey:<br />

<br />

<br />

honesty of elections.<br />

However, people were more optimistic in early 2007<br />

about Russia’s future than in 2006: 43% of people<br />

said that they thought economic conditions were<br />

<br />

thought conditions were getting worse, compared to<br />

22% the previous year.<br />

ARE ECONOMIC CONDITIONS IN RUSSIA<br />

GETTING BETTER OR WORSE?<br />

43%<br />

33%<br />

35%<br />

27%<br />

22%<br />

15%<br />

2 2<br />

2 2<br />

2 2<br />

0 0<br />

0 0<br />

0 0<br />

0 0<br />

0 0<br />

0 0<br />

6 7<br />

6 7<br />

6 7<br />

Better Same Worse<br />

Gallup <strong>World</strong>Poll Copyright© 2008 The Gallup Organization.<br />

HOW DO YOU RATE THE PERFORMANCE<br />

OF RUSSIA'S LEADERSHIP?<br />

Approve<br />

40% 38%<br />

Gallup <strong>World</strong>Poll Copyright© 2008 The Gallup Organization.<br />

Disapprove<br />

Spring 2008 Europe’s <strong>World</strong> | 23

allow the EU to escape from the argument<br />

between proponents of “soft containment”<br />

and “creeping integration” over whether<br />

Russia should be excluded from the G-8,<br />

and whether to negotiate a new Partnership<br />

and Co-operation Agreement. Under a new<br />

approach, the EU should adjust the level<br />

of cooperation to Russia’s observance of<br />

the spirit and the letter of common rules<br />

and agreements. If Moscow drags its feet<br />

on given G-8 commitments and policies,<br />

more meetings should be organised at a<br />

junior level under a G-7 format, without<br />

excluding Russia from the G-8. Similarly,<br />

the Union should not be afraid to use the<br />

EU-Russia summit and the negotiation of a<br />

new Partnership and Cooperation Agreement<br />

to highlight issues where Russia is being<br />

unhelpful, such as Kosovo and the conflicts<br />

in Georgia and Moldova.<br />

The second element of this strategy<br />

should be a principled bilateralism. Here<br />

again, the EU needs to find a middle way<br />

between those who see bilateral relations<br />

as a good way to reach out to Russia at a<br />

time of tension, and states who see such<br />

contact as a kind of betrayal (for example,<br />

Polish politicians have compared the deal<br />

on the Nordstream pipeline to the Molotov-<br />

Ribbentrop pact). The goal would be to<br />

ensure that bilateral contacts between Russia<br />

and individual EU member states reinforce<br />

common EU objectives. This would involve<br />

E.W. ADVISORY BOARD MEMBERS<br />

The Think Tanks &<br />

Civil Societies Program-<br />

TTCSP<br />

The Center for International Relations (CIR) is an independent,<br />

non-governmental establishment dedicated to the study of Polish foreign<br />

policy and those issues of international politics, which are of<br />

crucial importance to Poland. The Center’s primary objective is to offer<br />

political counseling, to describe Poland’s current international situation,<br />

and to continuously monitor the government’s foreign policy moves.<br />

The CIR prepares reports and analyses, holds conferences and seminars,<br />

publishes books and articles, carries out research projects and organizes<br />

working groups. We have built up a forum for foreign policy debate<br />

involving politicians, MPs, civil servants, local government officials,<br />

journalists, academics, students and representatives of other NGOs.<br />

Center for International Relations<br />

Emilii Plater 25<br />

00-688 Warsaw, Poland<br />

Tel. +48-22-646-52-67<br />

Fax. +48-22-646-52-58<br />

www.csm.org.pl<br />

“Helping to bridge the gap between knowledge<br />

and policy”<br />

Researching the trends and challenges facing<br />

think tanks, policymakers, and policy-oriented<br />

civil society groups...<br />

Sustaining, strengthening, and building<br />

capacity for think tanks around the world...<br />

Maintaining the largest, most<br />

comprehensive global database of<br />

over 5,000 think tanks...<br />

2007 Global Trends Survey of<br />

Think Tanks is now available.<br />

To request a summary of the<br />

findings send an email to:<br />

James G. McGann, Ph.d.- jm@fpri.org<br />

Senior Fellow and Director of TTCSP<br />

24 | Europe’s <strong>World</strong> Spring 2008

the creation of an early warning system which<br />

would allow both upcoming crises and deals<br />

to be discussed internally within the EU.<br />

Third, the EU should work harder to<br />

integrate its Eastern Neighbourhood.<br />

While some member states want to avoid<br />

competition for influence with Russia in<br />

Europe’s neighbourhood, and<br />

others want an “anti-Russian”<br />

neighbourhood policy, we<br />

believe that the EU should focus<br />

on encouraging its neighbours<br />

to adopt European norms and<br />

regulations and thus integrate<br />

them into the European project.<br />

The EU could could also invest<br />

in electricity interconnections<br />

with some neighbouring<br />

countries, give them access to<br />

the Nabucco pipeline, extend<br />

the European Energy Community and seek<br />

the full application the energy acquis in<br />

Turkey, Ukraine and Moldova. Equally, the EU<br />

should explore the possibility of giving the<br />

Trade Commissioner a mandate to fast-track<br />

access to the EU market for selected products<br />

in case of any more politically motivated<br />

Russian embargoes such as those imposed on<br />

Georgian and Moldovan wines.<br />

Fourth, the EU should insist on the<br />

implementation of contractual obligations<br />

and international commitments by Russia. The<br />

European Commission should, for instance,<br />

be given more political support to apply<br />

competition policy in the energy sector, and to<br />

investigate the more dubious deals between<br />

Russian and EU companies. More generally,<br />

the EU should demand the enforcement of<br />

the growing number of agreements which<br />

To avoid further<br />

partitioning of the<br />

EU energy market,<br />

the Commission<br />

could pre-approve<br />

big energy deals<br />

between European<br />

and foreign energy<br />

companies<br />

EU-RUSSIA<br />

have not been implemented – the PCA, the<br />

four Common Spaces and the European<br />

Energy Charter. Ignoring Russian foot-dragging<br />

undermines the very principle of a rules-based<br />

relationship with Russia.<br />

Finally, the EU needs to work hard on<br />

rebalancing the relationship with Russia. To<br />

achieve this, the EU needs<br />

to adopt an internal code<br />

of conduct on energy deals<br />

and guidelines on long-term<br />

contracts and forthcoming<br />

mergers. In order to avoid<br />

further monopolisation<br />

and partitioning of the EU<br />

energy market, the European<br />

Commission could be granted<br />

the right to pre-approve big<br />

energy deals on long-term<br />

contracts and pipelines<br />

concluded between European and foreign<br />

energy companies. The practical goals should<br />

be open competition, the rule of law and an<br />

integrated and flexible gas market.<br />

If the EU wants the new Russia to be a<br />

predictable and viable neighbour, it must build<br />

its partnership with Russia on the same<br />

foundations that made European integration a<br />

success – interdependence based on stable<br />

rules, transparency and consensus. But these<br />

foundations will not build themselves. The<br />

Union must be much more determined about<br />

agreeing rules of engagement with Russia, and<br />

then defending them.<br />

Mark Leonard is Executive Director of the new<br />

pan-European think-tank the European Council on<br />

Foreign Relations, where Nicu Popescu is a Policy<br />

Fellow. <br />

Spring 2008 Europe’s <strong>World</strong> | 25

VIEW FROM SLOVENIA<br />

SLOVENIA TAKES TO THE WORLD STAGE AS<br />

EU PRESIDENT FOR THE FIRST TIME<br />

By Janez Podobnik, Minister of the Environment and Spatial Planning<br />

of the Republic of Slovenia<br />

5.7% and 54% of households had access to<br />

the internet. In 2007, Slovenia became the<br />

first of the new EU member states to join<br />

the eurozone and, in 2008, it took on the<br />

presidency of the EU – again, the first new<br />

member state to do so.<br />

When Slovenia emerged as a<br />

sovereign state in 1991, very few<br />

people in western Europe had<br />

any real knowledge of the country. Several<br />

brands, products and services from Slovenia<br />

were familiar, but even these needed to be<br />

repackaged to reflect the country’s new<br />

circumstances. Slovenia is now becoming<br />

increasingly familiar on the world stage,<br />

thanks largely to its recognized scientists,<br />

artists and sportsmen. People in Europe and<br />

even across the globe can today pinpoint<br />

Slovenia on the world map.<br />

Slovenia’s economy has recently passed<br />

several milestones. In 2006, annual per<br />

capita Gross Domestic Product crossed the<br />

psychological mark of 15,000, growth was<br />

However, raw numbers cannot really<br />

illustrate the essence of Slovenia; its<br />

main attraction is the quality of life. Many<br />

people here live in small towns and villages<br />

scattered across the beautiful countryside.<br />

Roughly one third of the entire country<br />

is included in the Natura 2000 network.<br />

Slovenians are still closely connected to<br />

nature and have an almost sentimental<br />

relationship with the natural world; this is<br />

undoubtedly one of the most important<br />

facets of the Slovenian national character.<br />

When Slovenia joined the EU in 2004,<br />

there was some unease in older member<br />

states about possible mass emigration<br />

from the newcomers. One diplomat posted<br />

to Ljubljana reassured Slovenia’s worried<br />

neighbours by joking: “Come on; they won’t<br />

even move to Ljubljana – and they have a<br />

good reason for that.” Slovenians prefer to<br />

stay in their picturesque environment and<br />

live amid untouched nature.<br />

26 | Europe’s <strong>World</strong> Spring 2008

Unfortunately, this preference is generating<br />

unsustainable behaviour and represents a<br />

serious challenge for the national Ministry of<br />

Environment and Spatial Planning. Slovenia is<br />

currently facing a raft of major environmental<br />

problems, including deforestation, loss of<br />

biodiversity, degraded air and water quality, plus<br />

climate change, drought and desertification.<br />

Saving Europe’s biodiversity a<br />

priority for Slovenia<br />

Germany, Portugal and Slovenia set very ambitous<br />

goals on biodiversity when they drew up their<br />

joint EU presidency programme. The objective<br />

was to make more and more people across<br />

Europe aware of the importance of conservation<br />

– and to improve the implementation of measures<br />

aimed at halting the loss of biodiversity within<br />

the European Union by 2010. So conservation<br />

of European biodiversity is a priority for the<br />

<br />

At a conference on business and biodiversity<br />

in Lisbon late last year, top-level delegates<br />

reconfirmed that biodiversity counts. The<br />

conference agreed that Europe needs to improve<br />

the integration of biodiversity objectives into<br />

schemes that are designed to improve corporate<br />

social responsibility, strategic environmental<br />

assessment, social and environmental<br />

accreditation and labelling, plus socially<br />

responsible investment. All these major themes<br />

– and more – were discussed at Lisbon.<br />

Slovenians understand how vital it is to<br />

approach issues about spatial planning and<br />

the sustainable use of natural resources from<br />

the perspective of natural ecosystems. Slovenia<br />

sits at the junction of four major European<br />

ecological regions – the Alpine, Mediterranean,<br />

Dinaric and Panonic areas. So we recognise<br />

that we must respect regional principles when<br />

planning for the future. At the same time, we<br />

know that the development of conservation and<br />

biodiversity policies also depends crucially on the<br />

role of global treaties, including the Convention<br />

on Biological Diversity, as well as the Alpine,<br />

Barcelona and Danube Conventions. This is also<br />

true for the other great global environmental<br />

challenge of our time – climate change – and<br />

when considering the local consequences of<br />

droughts and floods. Thus, countries in our<br />

<br />

trans-boundary, regional and global cooperation<br />

and, more and more, they acknowledge the<br />

importance of implementing projects that better<br />

integrate effective and sustainable management<br />

of our natural resources.<br />

Slovenia is already playing its part. By chairing<br />

the Bureau of the Barcelona Convention and<br />

establishing the Adriatic Sea partnership, Slovenia<br />

has actively contributed to implementing the<br />

Mediterranean sustainable development strategy<br />

and the development of the EU maritime policy.<br />

Slovenia’s presidency of the European Union<br />

is a fresh opportunity to make a difference on<br />

biodiversity.<br />

Spring 2008 Europe’s <strong>World</strong> | 27

VIEW FROM SLOVENIA<br />

By chance - but symbolically - Slovenia<br />

made its first international appearance<br />

as a sovereign state at the 1992 United<br />

Nations Conference on Environment and<br />

Development in Rio de Janeiro. From then<br />

on it was actively involved in international<br />

efforts to protect nature, biodiversity and<br />

the environment in general. Initially, Slovenia<br />

concentrated on regional agreements,<br />

such as the Alpine Convention and the<br />

Convention for the Protection of the<br />

Mediterranean Sea. This was largely due to<br />

scarce human capacity. After the conclusion<br />

of the Dayton agreement, which formally<br />

ended the conflict in the western Balkans,<br />

the environment became an important area<br />

of cooperation among the new nations of<br />

south east Europe. The 2002 Framework<br />

Agreement on the Sava River Basin, signed<br />

in Kranjska gora in Slovenia, was formal<br />

confirmation that such cooperation had<br />

been established in the region.<br />

Protection of the environment is, of course,<br />

one of the EU’s top priorities, including<br />

conservation of natural resources through<br />

more efficient usage and consideration of the<br />

environmental aspects of all relevant policies.<br />

Germany, Portugal and Slovenia had already<br />

confirmed that protection of the environment<br />