Literature review: Impact of Chilean needle grass ... - Weeds Australia

Literature review: Impact of Chilean needle grass ... - Weeds Australia

Literature review: Impact of Chilean needle grass ... - Weeds Australia

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Campbell (1977, quoted by Gardener 1998) observed that Nassella trichotoma first appears in an area as widely sccattered<br />

tussocks, seven to twelve years later as patches, with scattered plants between them, and four to six years later as complete<br />

infestations. It appears that the development <strong>of</strong> N. neesiana infestations may show a similar pattern.<br />

Weed status<br />

Nassella species appear to become a problem wherever they naturalise. Verloove (2005, p. 112) that the complex <strong>of</strong> exotic<br />

stipoids including Jarava and Nassella spp. naturalised in Europe were“a serious threat for native vegetation” and “worldwide<br />

among the most troublesome weeds” the control and eradication <strong>of</strong> which was “very time consuming and expensive”.<br />

In New Zealand N. neesiana has been rated as extremely undesirabable (Bourdôt and Ryde 1986). It was declared a Class B<br />

noxious plant under the Noxious Plants Act 1978 by the Marlborough District Noxious Plants Authority in 1979 (Bourdôt and<br />

Hurrell 1987a) and later Class B in the whole country(Bourdôt 1988). However some have questioned its potential for major<br />

impact. Jacobs et al. (1989 p. 569) considered it “a localised troublesome weed <strong>of</strong> pastures”, Connor et al. (1993 p. 301) thought<br />

it has achieved only ‘modest success’, and that there were “no serious grounds” for predicting it would become a widespread<br />

problem, while Edgar and Connor (2000) considered to be only. “locally troublesome”. As <strong>of</strong> 2002 it was classed under the<br />

Biosecurity Act 1993 as requiring “Progressive Control” in the Marlborough region , and “Total Control” with the aim <strong>of</strong><br />

eventual eradication in Hawkes Bay region (Slay 2002a).<br />

Although native to Chile, it was classified as a weed there because <strong>of</strong> the effects <strong>of</strong> the seeds on livestock and livestock produce<br />

(Gardener et al. 1996b - see their citation).<br />

N. neesiana was listed as one <strong>of</strong> 20 <strong>Weeds</strong> <strong>of</strong> National Significance (WONS) in <strong>Australia</strong> in 1999 (Iaconis 2003). The process <strong>of</strong><br />

determining WONS was “the first attempt to prioritise weeds over a range <strong>of</strong> land uses at the national level” and was “not a<br />

purely scientific process” (Thorp and Lynch 2000 p. v). Of 71 weeds nominated by States and Territories N. neesiana was<br />

ranked 12th, based on evaluation by technical experts on six invasiveness questions, seven impact questions, potential for spread,<br />

and documentation <strong>of</strong> socioeconomic and environmental impacts (Thorp and Lynch 2000, McLaren et al. 2002a). The<br />

environmental impact assessment was rudimentary and “could be achieved only by taking a few pertinent environmental<br />

indicators and combining them into a ranking” (Thorp and Lynch 2000 p. 6). These were: 1. presence in a biogeographical<br />

region (each region being assigned equal value); 2. monoculture potential (ability to form pure stands giving a high score); 3.<br />

biodiversity indicator - based on the number <strong>of</strong> threatened species and special conservation areas (Thorp and Lynch 2000). N.<br />

neesiana was rated medium impact in respect <strong>of</strong> impact on threatened species, low impact in terms <strong>of</strong> threatened communities,<br />

“minimal national relevance” based on presence in less than 25% <strong>of</strong> biogeographic regions and low monoculture potential<br />

(Thorp and Lynch 2000 pp.15-16). Despite this, the species given a national listing. Recognition as a WONS resulted in a<br />

National Strategic Plan (ARMCANZ et al. 2001), increased mapping and recording, codes <strong>of</strong> practice to prevent spread and the<br />

development <strong>of</strong> better management methods (McLaren et al. 2002a).<br />

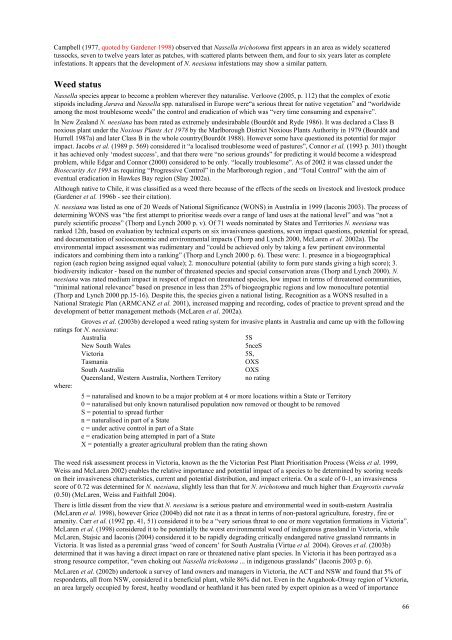

Groves et al. (2003b) developed a weed rating system for invasive plants in <strong>Australia</strong> and came up with the following<br />

ratings for N. neesiana:<br />

<strong>Australia</strong><br />

5S<br />

New South Wales<br />

5nceS<br />

Victoria 5S,<br />

Tasmania<br />

OXS<br />

South <strong>Australia</strong><br />

OXS<br />

Queensland, Western <strong>Australia</strong>, Northern Territory no rating<br />

where:<br />

5 = naturalised and known to be a major problem at 4 or more locations within a State or Territory<br />

0 = naturalised but only known naturalised population now removed or thought to be removed<br />

S = potential to spread further<br />

n = naturalised in part <strong>of</strong> a State<br />

c = under active control in part <strong>of</strong> a State<br />

e = eradication being attempted in part <strong>of</strong> a State<br />

X = potentially a greater agricultural problem than the rating shown<br />

The weed risk assessment process in Victoria, known as the the Victorian Pest Plant Prioritisation Process (Weiss et al. 1999,<br />

Weiss and McLaren 2002) enables the relative importance and potential impact <strong>of</strong> a species to be determined by scoring weeds<br />

on their invasiveness characteristics, current and potential distribution, and impact criteria. On a scale <strong>of</strong> 0-1, an invasiveness<br />

score <strong>of</strong> 0.72 was determined for N. neesiana, slightly less than that for N. trichotoma and much higher than Eragrostis curvula<br />

(0.50) (McLaren, Weiss and Faithfull 2004).<br />

There is little dissent from the view that N. neesiana is a serious pasture and environmental weed in south-eastern <strong>Australia</strong><br />

(McLaren et al. 1998), however Grice (2004b) did not rate it as a threat in terms <strong>of</strong> non-pastoral agriculture, forestry, fire or<br />

amenity. Carr et al. (1992 pp. 41, 51) considered it to be a “very serious threat to one or more vegetation formations in Victoria”.<br />

McLaren et al. (1998) considered it to be potentially the worst environmental weed <strong>of</strong> indigenous <strong>grass</strong>land in Victoria, while<br />

McLaren, Stajsic and Iaconis (2004) considered it to be rapidly degrading critically endangered native <strong>grass</strong>land remnants in<br />

Victoria. It was listed as a perennial <strong>grass</strong> ‘weed <strong>of</strong> concern’ for South <strong>Australia</strong> (Virtue et al. 2004). Groves et al. (2003b)<br />

determined that it was having a direct impact on rare or threatened native plant species. In Victoria it has been portrayed as a<br />

strong resource competitor, “even choking out Nassella trichotoma ... in indigenous <strong>grass</strong>lands” (Iaconis 2003 p. 6).<br />

McLaren et al. (2002b) undertook a survey <strong>of</strong> land owners and managers in Victoria, the ACT and NSW and found that 5% <strong>of</strong><br />

respondents, all from NSW, considered it a beneficial plant, while 86% did not. Even in the Angahook-Otway region <strong>of</strong> Victoria,<br />

an area largely occupied by forest, heathy woodland or heathland it has been rated by expert opinion as a weed <strong>of</strong> importance<br />

66