Literature review: Impact of Chilean needle grass ... - Weeds Australia

Literature review: Impact of Chilean needle grass ... - Weeds Australia

Literature review: Impact of Chilean needle grass ... - Weeds Australia

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

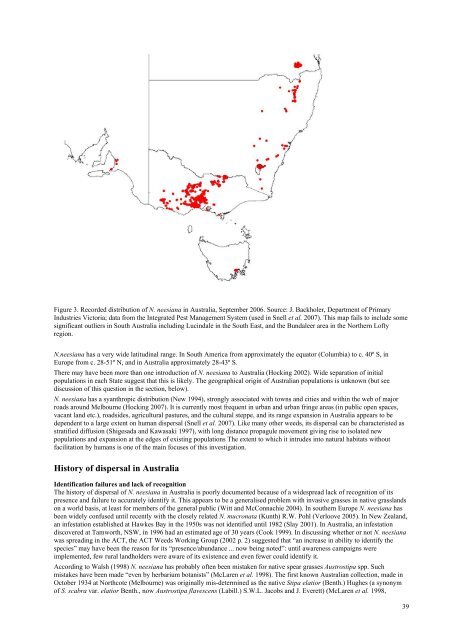

Figure 3. Recorded distribution <strong>of</strong> N. neesiana in <strong>Australia</strong>, September 2006. Source: J. Backholer, Department <strong>of</strong> Primary<br />

Industries Victoria; data from the Integrated Pest Management System (used in Snell et al. 2007). This map fails to include some<br />

significant outliers in South <strong>Australia</strong> including Lucindale in the South East, and the Bundaleer area in the Northern L<strong>of</strong>ty<br />

region.<br />

N.neesiana has a very wide latitudinal range. In South America from approximately the equator (Columbia) to c. 40º S, in<br />

Europe from c. 28-51º N, and in <strong>Australia</strong> approximately 28-43º S.<br />

There may have been more than one introduction <strong>of</strong> N. neesiana to <strong>Australia</strong> (Hocking 2002). Wide separation <strong>of</strong> initial<br />

populations in each State suggest that this is likely. The geographical origin <strong>of</strong> <strong>Australia</strong>n populations is unknown (but see<br />

discussion <strong>of</strong> this question in the section, below).<br />

N. neesiana has a syanthropic distribution (New 1994), strongly associated with towns and cities and within the web <strong>of</strong> major<br />

roads around Melbourne (Hocking 2007). It is currently most frequent in urban and urban fringe areas (in public open spaces,<br />

vacant land etc.), roadsides, agricultural pastures, and the cultural steppe, and its range expansion in <strong>Australia</strong> appears to be<br />

dependent to a large extent on human dispersal (Snell et al. 2007). Like many other weeds, its dispersal can be characteristed as<br />

stratified diffusion (Shigesada and Kawasaki 1997), with long distance propagule movement giving rise to isolated new<br />

populations and expansion at the edges <strong>of</strong> existing populations The extent to which it intrudes into natural habitats without<br />

facilitation by humans is one <strong>of</strong> the main focuses <strong>of</strong> this investigation.<br />

History <strong>of</strong> dispersal in <strong>Australia</strong><br />

Identification failures and lack <strong>of</strong> recognition<br />

The history <strong>of</strong> dispersal <strong>of</strong> N. neesiana in <strong>Australia</strong> is poorly documented because <strong>of</strong> a widespread lack <strong>of</strong> recognition <strong>of</strong> its<br />

presence and failure to accurately identify it. This appears to be a generalised problem with invasive <strong>grass</strong>es in native <strong>grass</strong>lands<br />

on a world basis, at least for members <strong>of</strong> the general public (Witt and McConnachie 2004). In southern Europe N. neesiana has<br />

been widely confused until recently with the closely related N. mucronata (Kunth) R.W. Pohl (Verloove 2005). In New Zealand,<br />

an infestation established at Hawkes Bay in the 1950s was not identified until 1982 (Slay 2001). In <strong>Australia</strong>, an infestation<br />

discovered at Tamworth, NSW, in 1996 had an estimated age <strong>of</strong> 30 years (Cook 1999). In discussing whether or not N. neesiana<br />

was spreading in the ACT, the ACT <strong>Weeds</strong> Working Group (2002 p. 2) suggested that “an increase in ability to identify the<br />

species” may have been the reason for its “presence/abundance ... now being noted”: until awareness campaigns were<br />

implemented, few rural landholders were aware <strong>of</strong> its existence and even fewer could identify it.<br />

According to Walsh (1998) N. neesiana has probably <strong>of</strong>ten been mistaken for native spear <strong>grass</strong>es Austrostipa spp. Such<br />

mistakes have been made “even by herbarium botanists” (McLaren et al. 1998). The first known <strong>Australia</strong>n collection, made in<br />

October 1934 at Northcote (Melbourne) was originally mis-determined as the native Stipa elatior (Benth.) Hughes (a synonym<br />

<strong>of</strong> S. scabra var. elatior Benth., now Austrostipa flavescens (Labill.) S.W.L. Jacobs and J. Everett) (McLaren et al. 1998,<br />

39