Literature review: Impact of Chilean needle grass ... - Weeds Australia

Literature review: Impact of Chilean needle grass ... - Weeds Australia

Literature review: Impact of Chilean needle grass ... - Weeds Australia

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

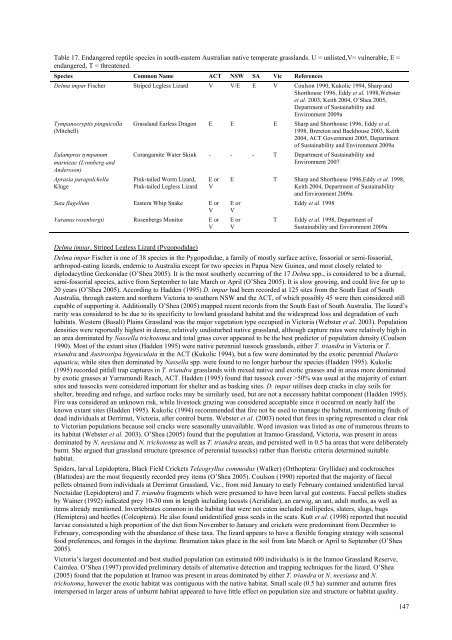

Table 17. Endangered reptile species in south-eastern <strong>Australia</strong>n native temperate <strong>grass</strong>lands. U = unlisted,V= vulnerable, E =<br />

endangered, T = threatened.<br />

Species Common Name ACT NSW SA Vic References<br />

Delma impar Fischer Striped Legless Lizard V V/E E V Coulson 1990, Kukolic 1994, Sharp and<br />

Shorthouse 1996, Eddy et al. 1998,Webster<br />

et al. 2003, Keith 2004, O’Shea 2005,<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> Sustainability and<br />

Environment 2009a<br />

Tympanocryptis pinguicolla<br />

(Mitchell)<br />

Eulamprus tympanum<br />

marnieae (Lvnnberg and<br />

Andersson)<br />

Aprasia parapulchella<br />

Kluge<br />

Grassland Earless Dragon E E E Sharp and Shorthouse 1996, Eddy et al.<br />

1998, Brereton and Backhouse 2003, Keith<br />

2004, ACT Government 2005, Department<br />

<strong>of</strong> Sustainability and Environment 2009a<br />

Corangamite Water Skink - - - T Department <strong>of</strong> Sustainability and<br />

Environment 2007<br />

Pink-tailed Worm Lizard,<br />

Pink-tailed Legless Lizard<br />

E or<br />

V<br />

Suta flagellum Eastern Whip Snake E or<br />

V<br />

Varanus rosenbergii Rosenbergs Monitor E or<br />

V<br />

E T Sharp and Shorthouse 1996,Eddy et al. 1998,<br />

Keith 2004, Department <strong>of</strong> Sustainability<br />

and Environment 2009a<br />

E or<br />

V<br />

E or<br />

V<br />

T<br />

Eddy et al. 1998<br />

Eddy et al. 1998, Department <strong>of</strong><br />

Sustainability and Environment 2009a<br />

Delma impar, Striped Legless Lizard (Pygopodidae)<br />

Delma impar Fischer is one <strong>of</strong> 38 species in the Pygopodidae, a family <strong>of</strong> mostly surface active, fossorial or semi-fossorial,<br />

arthropod-eating lizards, endemic to <strong>Australia</strong> except for two species in Papua New Guinea, and most closely related to<br />

diplodacytline Geckonidae (O’Shea 2005). It is the most southerly occurring <strong>of</strong> the 17 Delma spp., is considered to be a diurnal,<br />

semi-fossorial species, active from September to late March or April (O’Shea 2005). It is slow growing, and could live for up to<br />

20 years (O’Shea 2005). According to Hadden (1995) D. impar had been recorded at 125 sites from the South East <strong>of</strong> South<br />

<strong>Australia</strong>, through eastern and northern Victoria to southern NSW and the ACT, <strong>of</strong> which possibly 45 were then considered still<br />

capable <strong>of</strong> supporting it. Additionally O’Shea (2005) mapped recent records from the South East <strong>of</strong> South <strong>Australia</strong>. The lizard’s<br />

rarity was considered to be due to its specificity to lowland <strong>grass</strong>land habitat and the widespread loss and degradation <strong>of</strong> such<br />

habitats. Western (Basalt) Plains Grassland was the major vegetation type occupied in Victoria (Webster et al. 2003). Population<br />

densities were reportedly highest in dense, relatively undisturbed native <strong>grass</strong>land, although capture rates were relatively high in<br />

an area dominated by Nassella trichotoma and total <strong>grass</strong> cover appeared to be the best predictor <strong>of</strong> population density (Coulson<br />

1990). Most <strong>of</strong> the extant sites (Hadden 1995) were native perennial tussock <strong>grass</strong>lands, either T. triandra in Victoria or T.<br />

triandra and Austrostipa bigeniculata in the ACT (Kukolic 1994), but a few were dominated by the exotic perennial Phalaris<br />

aquatica, while sites then dominated by Nassella spp. were found to no longer harbour the species (Hadden 1995). Kukolic<br />

(1995) recorded pitfall trap captures in T. triandra <strong>grass</strong>lands with mixed native and exotic <strong>grass</strong>es and in areas more dominated<br />

by exotic <strong>grass</strong>es at Yarramundi Reach, ACT. Hadden (1995) found that tussock cover >50% was usual at the majority <strong>of</strong> extant<br />

sites and tussocks were considered important for shelter and as basking sites. D. impar utilises deep cracks in clay soils for<br />

shelter, breeding and refuge, and surface rocks may be similarly used, but are not a necessary habitat component (Hadden 1995).<br />

Fire was considered an unknown risk, while livestock grazing was considered acceptable since it occurred on nearly half the<br />

known extant sites (Hadden 1995). Kukolic (1994) recommended that fire not be used to manage the habitat, mentioning finds <strong>of</strong><br />

dead individuals at Derrimut, Victoria, after control burns. Webster et al. (2003) noted that fires in spring represented a clear risk<br />

to Victorian populations because soil cracks were seasonally unavailable. Weed invasion was listed as one <strong>of</strong> numerous threats to<br />

its habitat (Webster et al. 2003). O’Shea (2005) found that the population at Iramoo Grassland, Victoria, was present in areas<br />

dominated by N. neesiana and N. trichotoma as well as T. triandra areas, and persisted well in 0.5 ha areas that were deliberately<br />

burnt. She argued that <strong>grass</strong>land structure (presence <strong>of</strong> perennial tussocks) rather than floristic criteria determined suitable<br />

habitat.<br />

Spiders, larval Lepidoptera, Black Field Crickets Teleogryllus commodus (Walker) (Orthoptera: Gryllidae) and cockroaches<br />

(Blattodea) are the most frequently recorded prey items (O’Shea 2005). Coulson (1990) reported that the majority <strong>of</strong> faecal<br />

pellets obtained from individuals at Derrimut Grassland, Vic., from mid January to early February contained unidentified larval<br />

Noctuidae (Lepidoptera) and T. triandra fragments which were presumed to have been larval gut contents. Faecal pellets studies<br />

by Wainer (1992) indicated prey 10-30 mm in length including locusts (Acrididae), an earwig, an ant, adult moths, as well as<br />

items already mentioned. Invertebrates common in the habitat that were not eaten included millipedes, slaters, slugs, bugs<br />

(Hemiptera) and beetles (Coleoptera). He also found unidentified <strong>grass</strong> seeds in the scats. Kutt et al. (1998) reported that nocutid<br />

larvae consistuted a high proportion <strong>of</strong> the diet from November to January and crickets were predominant from December to<br />

February, corresponding with the abundance <strong>of</strong> these taxa. The lizard appears to have a flexible foraging strategy with seasonal<br />

food preferences, and forages in the daytime. Brumation takes place in the soil from late March or April to September (O’Shea<br />

2005).<br />

Victoria’s largest documented and best studied population (an estimated 600 individuals) is in the Iramoo Grassland Reserve,<br />

Cairnlea. O’Shea (1997) provided preliminary details <strong>of</strong> alternative detection and trapping techniques for the lizard. O’Shea<br />

(2005) found that the population at Iramoo was present in areas dominated by either T. triandra or N. neesiana and N.<br />

trichotoma, however the exotic habitat was contiguous with the native habitat. Small scale (0.5 ha) summer and autumn fires<br />

interspersed in larger areas <strong>of</strong> unburnt habitat appeared to have little effect on population size and structure or habitat quality.<br />

147