Literature review: Impact of Chilean needle grass ... - Weeds Australia

Literature review: Impact of Chilean needle grass ... - Weeds Australia

Literature review: Impact of Chilean needle grass ... - Weeds Australia

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Native temperate <strong>grass</strong>lands <strong>of</strong> south-eastern <strong>Australia</strong> and their conservation status<br />

According to the <strong>Australia</strong>n Native Vegetation Assessment 2001 (C<strong>of</strong>inas and Creighton 2001), 60,214 km 2 <strong>of</strong> the pre-European<br />

area <strong>of</strong> 589,212 km 2 <strong>of</strong> tussock <strong>grass</strong>lands in <strong>Australia</strong> had been cleared or substantially modifed by grazing by c. 2000. The<br />

category includes <strong>grass</strong>lands dominated by Astreleba, Sorghum etc., mostly in Queensland (282, 547 km 2 ) and the tussock<br />

<strong>grass</strong>lands <strong>of</strong> the dry inland, the largest proportion by far <strong>of</strong> which was in the north <strong>of</strong> the continent. Of all the major vegetation<br />

groups, <strong>grass</strong>lands are among the most affected by clearing in Victoria, ACT and NSW (See Table 9). The Victorian Midlands,<br />

Victorian Volcanic Plains (Victoria and South <strong>Australia</strong>) and the South East Coastal Plain (Victoria) had less than 30% <strong>of</strong> their<br />

orginal native vegetation remaining (C<strong>of</strong>inas and Creighton 2001).<br />

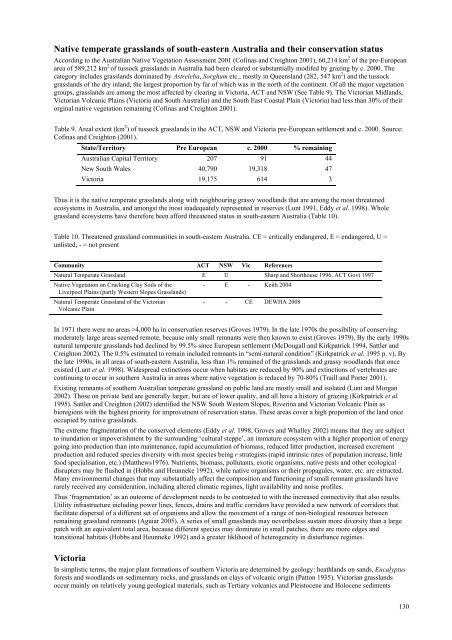

Table 9. Areal extent (km 2 ) <strong>of</strong> tussock <strong>grass</strong>lands in the ACT, NSW and Victoria pre-European settlement and c. 2000. Source:<br />

C<strong>of</strong>inas and Creighton (2001).<br />

State/Territory Pre European c. 2000 % remaining<br />

<strong>Australia</strong>n Capital Territory 207 91 44<br />

New South Wales 40,790 19,318 47<br />

Victoria 19,175 614 3<br />

Thus it is the native temperate <strong>grass</strong>lands along with neighbouring <strong>grass</strong>y woodlands that are among the most threatened<br />

ecosystems in <strong>Australia</strong>, and amongst the most inadequately represented in reserves (Lunt 1991, Eddy et al. 1998). Whole<br />

<strong>grass</strong>land ecosystems have therefore been afford threatened status in south-eastern <strong>Australia</strong> (Table 10).<br />

Table 10. Threatened <strong>grass</strong>land communities in south-eastern <strong>Australia</strong>. CE = critically endangered, E = endangered, U =<br />

unlisted, - = not present<br />

Community ACT NSW Vic References<br />

Natural Temperate Grassland E U Sharp and Shorthouse 1996, ACT Govt 1997<br />

Native Vegetation on Cracking Clay Soils <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Liverpool Plains (partly Western Slopes Grasslands)<br />

- E - Keith 2004<br />

Natural Temperate Grassland <strong>of</strong> the Victorian<br />

Volcanic Plain<br />

- - CE DEWHA 2008<br />

In 1971 there were no areas >4,000 ha in conservation reserves (Groves 1979). In the late 1970s the possibility <strong>of</strong> conserving<br />

moderately large areas seemed remote, because only small remnants were then known to exist (Groves 1979). By the early 1990s<br />

natural temperate <strong>grass</strong>lands had declined by 99.5% since European settlement (McDougall and Kirkpatrick 1994, Sattler and<br />

Creighton 2002). The 0.5% estimated to remain included remnants in “semi-natural condition” (Kirkpatrick et al. 1995 p. v). By<br />

the late 1990s, in all areas <strong>of</strong> south-eastern <strong>Australia</strong>, less than 1% remained <strong>of</strong> the <strong>grass</strong>lands and <strong>grass</strong>y woodlands that once<br />

existed (Lunt et al. 1998). Widespread extinctions occur when habitats are reduced by 90% and extinctions <strong>of</strong> vertebrates are<br />

continuing to occur in southern <strong>Australia</strong> in areas where native vegetation is reduced by 70-80% (Traill and Porter 2001).<br />

Existing remnants <strong>of</strong> southern <strong>Australia</strong>n temperate <strong>grass</strong>land on public land are mostly small and isolated (Lunt and Morgan<br />

2002). Those on private land are generally larger, but are <strong>of</strong> lower quality, and all have a history <strong>of</strong> grazing (Kirkpatrick et al.<br />

1995). Sattler and Creighton (2002) identified the NSW South Western Slopes, Riverina and Victorian Volcanic Plain as<br />

bioregions with the highest priority for improvement <strong>of</strong> reservation status. These areas cover a high proportion <strong>of</strong> the land once<br />

occupied by native <strong>grass</strong>lands.<br />

The extreme fragmentation <strong>of</strong> the conserved elements (Eddy et al. 1998, Groves and Whalley 2002) means that they are subject<br />

to inundation or impoverishment by the surrounding ‘cultural steppe’, an immature ecosystem with a higher proportion <strong>of</strong> energy<br />

going into production than into maintenance, rapid accumulation <strong>of</strong> biomass, reduced litter production, increased excrement<br />

production and reduced species diversity with most species being r strategists (rapid intrinsic rates <strong>of</strong> population increase, little<br />

food specialisation, etc.) (Matthews1976). Nutrients, biomass, pollutants, exotic organisms, native pests and other ecological<br />

disrupters may be flushed in (Hobbs and Heunneke 1992), while native organisms or their propagules, water, etc. are extracted.<br />

Many environmental changes that may substantially affect the composition and functioning <strong>of</strong> small remnant <strong>grass</strong>lands have<br />

rarely received any consideration, including altered climatic regimes, light availability and noise pr<strong>of</strong>iles.<br />

Thus ‘fragmentation’ as an outcome <strong>of</strong> development needs to be contrasted to with the increased connectivity that also results.<br />

Utility infrastructure including power lines, fences, drains and traffic corridors have provided a new network <strong>of</strong> corridors that<br />

facilitate dispersal <strong>of</strong> a different set <strong>of</strong> organisms and allow the movement <strong>of</strong> a range <strong>of</strong> non-biological resources between<br />

remaining <strong>grass</strong>land remnants (Aguiar 2005). A series <strong>of</strong> small <strong>grass</strong>lands may nevertheless sustain more diversity than a large<br />

patch with an equivalent total area, because different species may dominate in small patches, there are more edges and<br />

transitional habitats (Hobbs and Heunneke 1992) and a greater liklihood <strong>of</strong> heterogeneity in disturbance regimes.<br />

Victoria<br />

In simplistic terms, the major plant formations <strong>of</strong> southern Victoria are determined by geology: heathlands on sands, Eucalyptus<br />

forests and woodlands on sedimentary rocks, and <strong>grass</strong>lands on clays <strong>of</strong> volcanic origin (Patton 1935). Victorian <strong>grass</strong>lands<br />

occur mainly on relatively young geological materials, such as Tertiary volcanics and Pleistocene and Holocene sediments<br />

130