indians of the great basin - Museum Volkenkunde

indians of the great basin - Museum Volkenkunde

indians of the great basin - Museum Volkenkunde

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

INDIANS OF THE GREAT BASIN:<br />

THE 1883 FIELDWORK AND COLLECTION OF HERMAN TEN KATE<br />

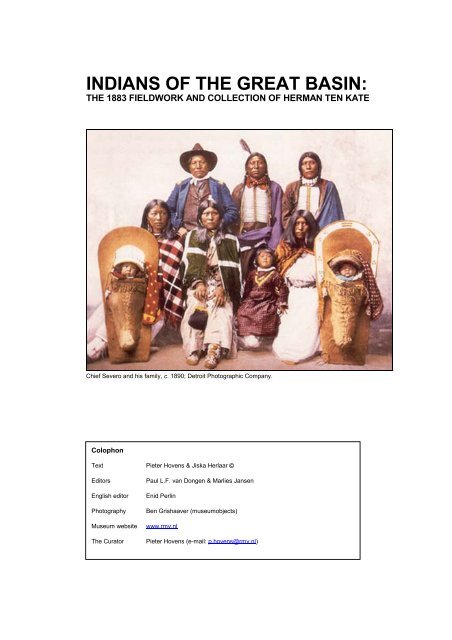

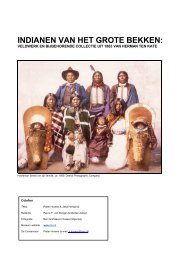

Chief Severo and his family, c. 1890; Detroit Photographic Company.<br />

Colophon<br />

Text Pieter Hovens & Jiska Herlaar ©<br />

Editors<br />

English editor<br />

Photography<br />

<strong>Museum</strong> website<br />

The Curator<br />

Paul L.F. van Dongen & Marlies Jansen<br />

Enid Perlin<br />

Ben Grishaaver (museumobjects)<br />

www.rmv.nl<br />

Pieter Hovens (e-mail: p.hovens@rmv.nl)

INDIANS OF THE GREAT BASIN: THE 1883 FIELDWORK AND COLLECTION OF HERMAN TEN KATE<br />

PIETER HOVENS & JISKA HERLAAR ©<br />

Digital publications <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> National <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> Ethnology<br />

Table <strong>of</strong> contents<br />

1. Indians <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Great Basin<br />

2. Herman ten Kate<br />

3. Fieldwork<br />

4. The Chemehuevis<br />

5. Chemehuevi art and material culture<br />

6. The Las Vegas Paiutes<br />

7. Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Paiute basketry<br />

8. The Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Utes<br />

9. Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Ute art and material culture<br />

10. Indian-white relations<br />

11. Conclusion<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

Appendix<br />

References<br />

1

INDIANS OF THE GREAT BASIN: THE 1883 FIELDWORK AND COLLECTION OF HERMAN TEN KATE<br />

PIETER HOVENS & JISKA HERLAAR ©<br />

Digital publications <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> National <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> Ethnology<br />

1. Indians <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Great Basin<br />

The Great Basin is a desert region in <strong>the</strong> American West in which Native American peoples<br />

developed a distinct culture attuned in sophisticated ways to <strong>the</strong>ir desert ecosystem, a<br />

culture necessitated by <strong>the</strong> precarious nature <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir environment. The Great Basin culture<br />

area lies between <strong>the</strong> Rocky Mountains in <strong>the</strong> east, and <strong>the</strong> Sierra Nevada and Cascade<br />

Range in <strong>the</strong> west. It covers <strong>the</strong> states <strong>of</strong> Nevada and Utah, western Colorado and western<br />

Wyoming, sou<strong>the</strong>rn Idaho, and smaller areas <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> adjacent states <strong>of</strong> Oregon, California,<br />

Arizona and New Mexico.<br />

The Great Basin culture area; after D’Azevedo 1986:ix.<br />

The Great Basin culture area is characterized by semi-desert and desert flatlands dissected<br />

by mountain chains. The region has <strong>the</strong> lowest rainfall and highest evaporation rate in <strong>the</strong><br />

United States, and <strong>the</strong> resulting aridity has characterized <strong>the</strong> flora and fauna. Vegetation is<br />

sparse, and is dominated by a variety <strong>of</strong> drought-resistant grasses, sagebrush, cacti and<br />

succulents. Mountains are clad in juniper, piñon, scrub oak, pine, aspen, spruce and fir,<br />

depending on elevation. Typical animals <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Great Basin are a variety <strong>of</strong> reptiles, notably<br />

snakes and lizards; rodents, including mice, rats and squirrels; and hares and rabbits in<br />

some abundance. Pronghorn antelope, elk, bighorn sheep and mule deer were <strong>the</strong> largest<br />

mammals to be found <strong>the</strong>re, although in small numbers. O<strong>the</strong>r animal species <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Great<br />

Basin include mountain lions, coyotes and foxes.<br />

2

INDIANS OF THE GREAT BASIN: THE 1883 FIELDWORK AND COLLECTION OF HERMAN TEN KATE<br />

PIETER HOVENS & JISKA HERLAAR ©<br />

Digital publications <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> National <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> Ethnology<br />

Impressions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Great Basin landscape.<br />

Due to <strong>the</strong> relative paucity <strong>of</strong> food resources in <strong>the</strong> Great Basin, <strong>the</strong>ir limited productivity, and<br />

a seasonal harvest cycle, <strong>the</strong> number <strong>of</strong> Native Americans inhabiting this region was always<br />

low. The Indians who made it <strong>the</strong>ir homeland developed a nomadic lifestyle to exploit<br />

available food resources periodically, living and travelling in small groups, <strong>of</strong>ten as single<br />

families. All possible sources <strong>of</strong> food in <strong>the</strong> harsh desert environment needed to be exploited<br />

for survival. The men were <strong>the</strong> hunters, and <strong>the</strong> women ga<strong>the</strong>rers <strong>of</strong> plant foods, although<br />

both sexes assisted each o<strong>the</strong>r when this was required. Hunters used bows, arrows, spears,<br />

clubs, nets and snares, and <strong>the</strong> men went after antelope, rodents, hares and rabbits, and<br />

reptiles. Communal hunts were organized to capture antelope and rabbits. Streams and<br />

lakes were sources <strong>of</strong> fish, turtles and ducks provided <strong>the</strong>y did not dry up. The women were<br />

adept at weaving baskets in a large variety <strong>of</strong> forms and sizes, used for collecting, preparing,<br />

serving and storing food. With <strong>the</strong> help <strong>of</strong> digging sticks <strong>the</strong>y unear<strong>the</strong>d roots, bulbs and<br />

tubers. Plant foods harvested in a seasonal cycle included roots, bulbs, cactus fruit, agave<br />

stalks, <strong>the</strong> seeds <strong>of</strong> mesquite, and a <strong>great</strong> variety <strong>of</strong> grasses, and nuts, especially piñons.<br />

Seeds and nuts were parched and ground into flour, from which porridge and cakes were<br />

made, <strong>the</strong> latter for underground storage, packed in skin bags. Caterpillars, grasshoppers,<br />

cicadas, fly and moth larvae, and ant eggs contributed to <strong>the</strong> diet.<br />

Groups <strong>of</strong> families formed a band and exploited <strong>the</strong> resources in <strong>the</strong>ir territory. Often <strong>the</strong>y<br />

assembled in wintertime into a larger settlement, from which <strong>the</strong>y went out on hunting and<br />

ga<strong>the</strong>ring expeditions, led by experienced men. Seeds, berries and nuts collected and stored<br />

over <strong>the</strong> summer and fall, provided necessary nutrition during <strong>the</strong> cold season, in addition to<br />

<strong>the</strong> prey caught in <strong>the</strong> hunt. On <strong>the</strong>se occasions <strong>the</strong>y lived in "wickiups", conical or domeshaped<br />

huts covered with brush, mats or bark. In <strong>the</strong> spring <strong>the</strong> people dispersed and<br />

traveled in nuclear or extended families, exploiting all available food resources. They built<br />

temporary wind and sun screens to shield <strong>the</strong>mselves against <strong>the</strong> elements. Caves and rock<br />

shelters also provided protection. Men and women dressed in simple clothing, made from<br />

animal hides and skins, shredded bark and plant fibers. Rabbit-fur blankets provided<br />

protection against <strong>the</strong> cold. Women wove basketry hats for both sexes.<br />

Religious leadership was provided by shamans who cured <strong>the</strong> sick in healing rituals, and<br />

tried to influence <strong>the</strong> outcome <strong>of</strong> communal hunts by appealing to <strong>the</strong> spirits. Those<br />

appearing in dreams were regarded as sources <strong>of</strong> individual personal power. In sweat huts<br />

Indians periodically purified <strong>the</strong>mselves, physically and mentally.<br />

Most <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Indians encountered by <strong>the</strong> first explorers and settlers in <strong>the</strong> Great Basin spoke<br />

languages belonging to <strong>the</strong> Uto-Aztecan family: Paiutes, including Bannocks and<br />

Chemehuevis, Utes, Shoshones and Kawaiisu. The relation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> language <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Washoes<br />

has not yet been satisfactorily established, although a Hokan source is most likely.<br />

3

INDIANS OF THE GREAT BASIN: THE 1883 FIELDWORK AND COLLECTION OF HERMAN TEN KATE<br />

PIETER HOVENS & JISKA HERLAAR ©<br />

Digital publications <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> National <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> Ethnology<br />

Until <strong>the</strong> arrival <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> white man, <strong>the</strong> culture <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Native Americans <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Great Basin<br />

remained relatively unchanged from <strong>the</strong> establishment <strong>of</strong> a general Desert Archaic Culture<br />

about 8.000 years B.C. However, <strong>the</strong> presence <strong>of</strong> man might be much older in this region,<br />

and may date back to Paleo-Indian times, as for example at Fort Rock Cave in Oregon.<br />

Archeological research focussed on this issue continues 1 .<br />

Fort Rock Cave, Oregon.<br />

4

INDIANS OF THE GREAT BASIN: THE 1883 FIELDWORK AND COLLECTION OF HERMAN TEN KATE<br />

PIETER HOVENS & JISKA HERLAAR ©<br />

Digital publications <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> National <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> Ethnology<br />

2. Herman ten Kate<br />

Herman Frederik Carel ten Kate was born in 1858 in Amsterdam, but grew up in The Hague.<br />

The Ten Kate family was blessed by <strong>the</strong> muses, since it counted many painters and literary<br />

men among its members. Ten Kate's fa<strong>the</strong>r was a popular painter in his time and received royal<br />

patronage. It was his modest fortune which enabled Ten Kate jr. to abandon his early artistic<br />

education at <strong>the</strong> Art Academy and register as a student <strong>of</strong> medicine, geography, non-western<br />

languages and Indonesian ethnology at <strong>the</strong> University <strong>of</strong> Leiden in 1877. Although this shift<br />

from art to science was remarkable, it was a natural outcome <strong>of</strong> his personal development. As<br />

he was an avid reader <strong>of</strong> popular juvenile literature, an interest in Native North American<br />

peoples and cultures had taken hold <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> young boy, and <strong>the</strong> books <strong>of</strong> James Fennimore<br />

Cooper, Gustave Aimard, Friedrich Gerstäcker and Mayne Reid cluttered his shelves. In 1876<br />

Ten Kate went to Corsica on a painting trip, accompanying Charles van de Velde, a friend <strong>of</strong> his<br />

fa<strong>the</strong>r. With stories <strong>of</strong> his adventures and research in <strong>the</strong> East Indies and South Africa, Van de<br />

Velde encouraged Ten Kate's smouldering interest in non-western peoples and cultures.<br />

However, back in Holland it took some effort to persuade his fa<strong>the</strong>r to support his son's<br />

decision on a new career.<br />

The year 1877 also marks <strong>the</strong> beginning <strong>of</strong> academic anthropology in <strong>the</strong> Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands, since<br />

<strong>the</strong> first chair in (Indonesian) anthropology was established at <strong>the</strong> University <strong>of</strong> Leiden. It was<br />

occupied by P.J. Veth, whose topical and regional interests ranged far beyond <strong>the</strong> Dutch colony<br />

in Asia, since he also became an authority on early sources on African cultures. Moreover,<br />

some interest was devoted to Native American cultures in <strong>the</strong> West Indies, where Holland ruled<br />

over <strong>the</strong> colonies <strong>of</strong> Surinam and <strong>the</strong> Dutch Antilles. Under Veth's guidance Ten Kate was<br />

encouraged to develop his Americanist interest to <strong>the</strong> full. During his time in Leiden he<br />

published his first article on North American Indians.<br />

Herman ten Kate, 1881.<br />

After two years Ten Kate transferred to Paris, where he studied under Paul Broca and Paul<br />

Topinard at <strong>the</strong> Ecole d'Anthropologie, specializing in physical anthropology. He developed a<br />

friendship with E-T. Hamy, who shared his Americanist interests. In <strong>the</strong> autumn <strong>of</strong> 1880 he<br />

worked at <strong>the</strong> University <strong>of</strong> Berlin, where he received guidance from Adolf Bastian and probably<br />

attended a number <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> courses in ethnology Bastian was teaching at that time. Over <strong>the</strong> next<br />

two years he continued his medical, zoological and geographical studies at <strong>the</strong> academic<br />

institutions <strong>of</strong> Göttingen and Heidelberg, meanwhile pursuing his doctoral research on<br />

Mongoloid crania. In April 1882 he received a Ph.D. in zoology from Heidelberg university. 2<br />

5

INDIANS OF THE GREAT BASIN: THE 1883 FIELDWORK AND COLLECTION OF HERMAN TEN KATE<br />

PIETER HOVENS & JISKA HERLAAR ©<br />

Digital publications <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> National <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> Ethnology<br />

It was an explicit interest in non-European peoples, notably Native North American cultures,<br />

which had prompted Ten Kate to enter university. He chose courses which would qualify him<br />

for anthropological research: Indonesian ethnology and geography, Indonesian and Oriental<br />

languages, historical geography, and comparative anatomy. Practical considerations with<br />

regard to future salaried employment obliged him to specialize in <strong>the</strong> natural sciences and<br />

non-western languages, concentrating on zoology for an early Ph.D., and on medicine, in<br />

which field he received his M.D. in 1895 after fur<strong>the</strong>r studies at <strong>the</strong> universities <strong>of</strong> Halle,<br />

Montpellier, Heidelberg and Freiburg. Herman ten Kate was thus a typical representative <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> early phase in <strong>the</strong> development <strong>of</strong> anthropology as an academic discipline. 3<br />

6

INDIANS OF THE GREAT BASIN: THE 1883 FIELDWORK AND COLLECTION OF HERMAN TEN KATE<br />

PIETER HOVENS & JISKA HERLAAR ©<br />

Digital publications <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> National <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> Ethnology<br />

3. Fieldwork<br />

Having developed an early interest in North American Indians, Ten Kate planned an exploratory<br />

fieldwork journey to <strong>the</strong> western United States and nor<strong>the</strong>rn Mexico. He received scientific<br />

guidance and practical advice from his tutors in Leiden, Paris and Berlin, and material support<br />

from Dutch and French scientific societies. However, most <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> costs <strong>of</strong> his first fieldwork<br />

were borne by his always supportive and generous fa<strong>the</strong>r.<br />

The primary aim <strong>of</strong> Ten Kate's first fieldwork in North America was to obtain a first-hand and<br />

representative impression <strong>of</strong> aboriginal tribal cultures and <strong>the</strong>ir current state under white<br />

political and cultural domination. His research among <strong>the</strong> Iroquois in Upper New York State in<br />

<strong>the</strong> autumn <strong>of</strong> 1882 led to a streng<strong>the</strong>ning <strong>of</strong> an already apparent salvage approach in his first<br />

fieldwork. 4 However, Ten Kate also defined o<strong>the</strong>r specific objectives <strong>of</strong> his travels and<br />

researches: <strong>the</strong> classification <strong>of</strong> physical types, <strong>the</strong> collection <strong>of</strong> ethnographic artifacts, <strong>the</strong><br />

determination <strong>of</strong> intertribal relationships on <strong>the</strong> basis <strong>of</strong> physical anthropological, ethnolinguistic<br />

and ethnographic data, and <strong>the</strong> description and analysis <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> influence and consequences <strong>of</strong><br />

white domination over Indian societies. To this effect he collected and studied scientific<br />

literature; purchased artifacts; made physical anthropological and ethnographic observations;<br />

held interviews with key Indian and white informants; measured many Indians; collected skulls<br />

and skeletal material, and completed <strong>the</strong> standard vocabulary lists <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Bureau <strong>of</strong> American<br />

Ethnology. 5<br />

During his 1882-1883 fieldwork in <strong>the</strong> American West, Ten Kate was able to acquire over three<br />

hundred ethnographic artifacts for <strong>the</strong> National <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> Ethnology in Leiden. Series 361 was<br />

purchased with a grant from <strong>the</strong> Holland Academy <strong>of</strong> Sciences. The acquisition <strong>of</strong> series 362,<br />

which includes <strong>the</strong> Great Basin materials, was rendered possible with a grant from <strong>the</strong><br />

Department <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Interior, <strong>of</strong> which <strong>the</strong> museum was a part at that time. Ten Kate purchased<br />

additional artifacts with private funds, and he acquired additional artifacts in 1887-1888, when<br />

he was a member <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Hemenway Southwestern Archaeological Expedition. 6 A catalogue <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> Ten Kate collection, now consisting <strong>of</strong> approximately four hundred artifacts, is in progress.<br />

Ten Kate in Camp Apache, August 1883. Photo: C. Duhem.<br />

7

INDIANS OF THE GREAT BASIN: THE 1883 FIELDWORK AND COLLECTION OF HERMAN TEN KATE<br />

PIETER HOVENS & JISKA HERLAAR ©<br />

Digital publications <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> National <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> Ethnology<br />

In 1885 Ten Kate published a voluminous book, written in Dutch, on his 1882-1883 travels and<br />

fieldwork, and an English translation has just been published. 7 In addition he published<br />

numerous articles on his research in scientific periodicals in <strong>the</strong> Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands and France. Part<br />

<strong>of</strong> his Hemenway Expedition diary was only published in 1925 in a collection <strong>of</strong> his travel<br />

narratives, and has recently been translated. 8 These writings, as well as his personal letters,<br />

provide us with a <strong>great</strong> deal <strong>of</strong> information about his travels and researches.<br />

After a first visit to <strong>the</strong> Iroquois <strong>of</strong> Upper New York State in <strong>the</strong> fall <strong>of</strong> 1882, Ten Kate traveled to<br />

<strong>the</strong> Southwest and conducted fieldwork among <strong>the</strong> Tiguas <strong>of</strong> Ysleta del Sur near El Paso, <strong>the</strong><br />

Tohono O'odham (Papagos) at San Xavier del Bac, and <strong>the</strong> Yaquis near Guaymas, Sonora.<br />

Accompanied by <strong>the</strong> British ornithologist Lyman Belding, he excavated burial sites and<br />

documented rock paintings in sou<strong>the</strong>rn Baja California. 9 After leaving Mexico in April 1883, he<br />

spent some time among <strong>the</strong> Quechans near Yuma. 10 Subsequently he planned to conduct<br />

fieldwork among <strong>the</strong> Mohaves on <strong>the</strong> Colorado River, and continue his research among <strong>the</strong><br />

Pimas. However, when he heard about a Chemehuevi village on <strong>the</strong> Colorado River Indian<br />

reservation, he planned to pay at least a visit to that settlement. He also accepted an<br />

unexpected opportunity for visiting <strong>the</strong> Las Vegas division <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Paiutes fur<strong>the</strong>r<br />

upstream. 11 8

INDIANS OF THE GREAT BASIN: THE 1883 FIELDWORK AND COLLECTION OF HERMAN TEN KATE<br />

PIETER HOVENS & JISKA HERLAAR ©<br />

Digital publications <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> National <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> Ethnology<br />

4. The Chemehuevis<br />

Ten Kate left Yuma by buckboard on April 21, 1883. Crossing <strong>the</strong> Gila River he almost lost his<br />

luggage when his wagon sank into a mud hole in <strong>the</strong> middle <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> stream. Only with <strong>great</strong><br />

difficulty did <strong>the</strong> six horse-team manage to pull <strong>the</strong> wagon and its load onto <strong>the</strong> bank. At Castle<br />

Dome Landing he encountered several Apache Yumas. The journey continued across <strong>the</strong><br />

barren Chocolate Mountains and along <strong>the</strong> Colorado River, and in <strong>the</strong> early evening <strong>of</strong> April 24<br />

Ten Kate arrived in Ehrenberg, where he was forced to spend several days waiting for transport<br />

by buckboard to <strong>the</strong> Mohave and Chemehuevi Agency at Parker. From April 28 to May 6 he<br />

conducted fieldwork among <strong>the</strong> Yuman-speaking Mohaves, during which time he visited <strong>the</strong><br />

Chemehuevi settlement, twelve miles from <strong>the</strong> agency headquarters.<br />

On May 7 Ten Kate boarded <strong>the</strong> stern-wheeler "Mohave" and travelled northward by way <strong>of</strong><br />

Aubrey's Landing, Chemehuevi Valley and Needles to Fort Mohave, where he continued his<br />

research among <strong>the</strong> Mohaves for several days. He made <strong>the</strong> acquaintance <strong>of</strong> Indian inspector<br />

general C.H. Howard, and agreed to visit <strong>the</strong> Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Paiutes fur<strong>the</strong>r upstream with this <strong>of</strong>ficial<br />

from <strong>the</strong> Bureau <strong>of</strong> Indian Affairs. On May 13 <strong>the</strong>y embarked on a steamer, and journeyed<br />

upstream, passing Hardyville and Boulder Rapids, stopping at Cottonwood Island, continuing<br />

past Painted Canyon, and arriving at El Dorado Canyon, a mining camp in sou<strong>the</strong>rn Nevada, on<br />

<strong>the</strong> evening <strong>of</strong> May 15. The next day Howard called toge<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> local Paiutes, providing Ten<br />

Kate with an opportunity for making observations and interviewing several Indians.<br />

The Colorado River at Black Canyon; lithograph by Balduin Möllhausen, 1858.<br />

According to <strong>the</strong> Indian Agent's annual report, <strong>the</strong> reservation harboured 811 Mohaves and 215<br />

Chemehuevis, <strong>the</strong> latter living in <strong>the</strong> northwestern corner <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> reservation on <strong>the</strong> Californian<br />

side <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Colorado River. During his fieldwork Ten Kate noted linguistic, physical, and<br />

psychological differences between <strong>the</strong> Mohaves and Chemehuevis. Because <strong>the</strong> Chemehuevi<br />

language sounded much harsher than <strong>the</strong> melodious Mohave-Yuman, Ten Kate tried to<br />

determine its linguistic affiliation. On <strong>the</strong> basis <strong>of</strong> his ethnolinguistic knowledge he concluded<br />

that <strong>the</strong> Chemehuevis were a division <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Paiutes. He later found this conclusion supported<br />

by <strong>the</strong> name by which <strong>the</strong> Indians called <strong>the</strong>mselves: "Tontewaits", meaning "those <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

south". They formed <strong>the</strong> most sou<strong>the</strong>rn division <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Paiutes.<br />

9

INDIANS OF THE GREAT BASIN: THE 1883 FIELDWORK AND COLLECTION OF HERMAN TEN KATE<br />

PIETER HOVENS & JISKA HERLAAR ©<br />

Digital publications <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> National <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> Ethnology<br />

Regional groups <strong>of</strong> Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Paiutes; after Kelly and Fowler 1986:369.<br />

The Chemehuevis also differed physically from <strong>the</strong> Mohaves, being shorter and less robust,<br />

with flatter faces. The shape <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir skulls was deemed to be brachycephalous (broadly<br />

shaped) and <strong>the</strong>y resembled <strong>the</strong> Mohaves in this respect. They had peculiar moustaches, <strong>the</strong><br />

middle part <strong>of</strong> which was shaved <strong>of</strong>f, leaving only <strong>the</strong> ends near <strong>the</strong> corners <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> mouth. Ten<br />

Kate managed to take <strong>the</strong> physical measurements <strong>of</strong> fourteen men, but only after he had made<br />

<strong>the</strong>m believe that this was in order to determine <strong>the</strong> size <strong>of</strong> hats <strong>the</strong> government would provide:<br />

an early example <strong>of</strong> anthropological ethics in fieldwork.<br />

The Chemehuevi dwellings were similar to those <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Quechans and Mohaves. Their earth<br />

lodges or winter houses were built in shallow excavated pits, which were surrounded by beams<br />

and poles, given a flat ro<strong>of</strong>, and <strong>the</strong>n covered with earth and mud. Shapes varied from round to<br />

oblong and rectangular. They also constructed separate sweat lodges. Their pottery also<br />

resembled that <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Colorado River Yumans. Ten Kate bought a pair <strong>of</strong> white deerskin boots,<br />

called pagap by <strong>the</strong> Indians. The acquisition <strong>of</strong> traditional ethnographic objects was virtually<br />

impossible according to Ten Kate, since most expressions <strong>of</strong> traditional material culture had<br />

vanished. Only basketry was still being produced, and he admired its quality, as a competent<br />

judge after seeing ethnographic collections in several European and American museums, and<br />

having visited <strong>the</strong> Tohono O'odham (Papagos) earlier. Ten Kate saw similar baskets among <strong>the</strong><br />

Quechans and Mohaves, and assumed that <strong>the</strong> Chemehuevis traded <strong>the</strong>ir craftwork with <strong>the</strong>se<br />

tribes.<br />

Ten Kate paid a visit to Thomas, <strong>the</strong> chief <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Chemehuevis. However, it seems that <strong>the</strong><br />

head man was not much use as an informant because he was actively engaged in a game <strong>of</strong><br />

cards in a sweat house, and did not want to be disturbed. His face was painted red, but he wore<br />

a western-style black hat like most <strong>of</strong> his tribesmen. Few Chemehuevis, however, spoke<br />

English or Spanish. Most used Mohave in <strong>the</strong>ir dealings with that tribe, since few Mohaves were<br />

able or willing to master <strong>the</strong> Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Paiute language. Interethnic sexual relations with whites<br />

were much more frequent among <strong>the</strong> Chemehuevis than <strong>the</strong> Mohaves, resulting in a<br />

considerable number <strong>of</strong> mixed-blood Indians. Many women left <strong>the</strong> tribe to live with <strong>the</strong>ir white<br />

husbands in mining camps and frontier towns.<br />

10

INDIANS OF THE GREAT BASIN: THE 1883 FIELDWORK AND COLLECTION OF HERMAN TEN KATE<br />

PIETER HOVENS & JISKA HERLAAR ©<br />

Digital publications <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> National <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> Ethnology<br />

Ten Kate was aware <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> fact that <strong>the</strong> federal government had forcefully removed <strong>the</strong> band<br />

from <strong>the</strong>ir fertile Chemehuevi Valley to <strong>the</strong> arid desert reservation, an "unselfish" act as he<br />

noted cynically, clearly showing where his sympathies lay. A number <strong>of</strong> Chemehuevi children<br />

visited <strong>the</strong> agency day school, which was established in 1881. The women teachers told Ten<br />

Kate that <strong>the</strong> Chemehuevi youngsters were generally more intelligent than <strong>the</strong>ir Mohave<br />

counterparts. They had observed <strong>the</strong> same for boys as compared to girls. Intertribal<br />

personality differences were also noted, <strong>the</strong> Chemehuevis being headstrong and unforgiving<br />

while <strong>the</strong> Mohaves were impulsive but ligh<strong>the</strong>arted and humorous, according to <strong>the</strong> notes<br />

made by <strong>the</strong> Dutch anthropologist. Among <strong>the</strong> Chemehuevis Ten Kate purchased several<br />

clay effigies, several baskets, items <strong>of</strong> dress, a flute and a war club.<br />

11

INDIANS OF THE GREAT BASIN: THE 1883 FIELDWORK AND COLLECTION OF HERMAN TEN KATE<br />

PIETER HOVENS & JISKA HERLAAR ©<br />

Digital publications <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> National <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> Ethnology<br />

5. Chemehuevi art and material culture<br />

"Mohavezation" <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Chemehuevis explains <strong>the</strong> similarity in dwellings and pottery <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> two<br />

tribes as noted by Ten Kate. The Mohave type <strong>of</strong> summer house was even found as far north<br />

as <strong>the</strong> Moapa Paiutes. 12 His observation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> similarity in <strong>the</strong> pottery <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Quechans,<br />

Mohaves and Chemehuevis was as much <strong>the</strong> result <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Mohave trading <strong>the</strong>ir wares with<br />

neighbouring groups, as <strong>the</strong> Chemehuevis producing <strong>the</strong>ir own pottery and being substantially<br />

influenced by <strong>the</strong>ir neighbours' craftwork. 13 It was <strong>the</strong> women who made <strong>the</strong> pottery, a fact not<br />

mentioned by Ten Kate, who probably saw only finished vessels in Indian households. The<br />

Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Paiutes, including <strong>the</strong> Chemehuevis, had <strong>the</strong>ir own pottery tradition which was less<br />

developed because <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir semi-nomadism. Moreover, pottery making declined substantially<br />

soon after <strong>the</strong> arrival <strong>of</strong> white settlers and <strong>the</strong> introduction <strong>of</strong> western trade goods among most<br />

bands. 14<br />

At <strong>the</strong> agency school on <strong>the</strong> Mohave Indian Reservation, Ten Kate acquired four small pottery<br />

busts <strong>of</strong> people, made by a Chemehuevi girl by <strong>the</strong> name <strong>of</strong> Topilla who showed artistic talent.<br />

Pottery effigies by Topilla, Chemehuevi (RMV 362-205, 206, 207, 208).<br />

It is not known whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> pottery classes in which <strong>the</strong>se were made were part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

conventional art training in <strong>the</strong> school’s regular curriculum, or whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong>se classes were<br />

organized because <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> strong pottery tradition among <strong>the</strong> Mohaves, a tradition later adopted<br />

by <strong>the</strong> Chemehuevis. Topilla’s name was carved in <strong>the</strong> base <strong>of</strong> one effigy, something probably<br />

encouraged by her teacher, but possibly suggested by Ten Kate. Small pottery effigies had<br />

been made for a long time among <strong>the</strong> Paiutes, and were used as children's toys. 15<br />

Ten Kate collected four baskets which he listed as Chemehuevi. The study <strong>of</strong> Chemehuevi<br />

basketry has been neglected by anthropologists. Single observations on <strong>the</strong> craft are scattered<br />

12

INDIANS OF THE GREAT BASIN: THE 1883 FIELDWORK AND COLLECTION OF HERMAN TEN KATE<br />

PIETER HOVENS & JISKA HERLAAR ©<br />

Digital publications <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> National <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> Ethnology<br />

throughout <strong>the</strong> literature, but do not provide a clear or coherent picture, let alone a complete<br />

one. Clara Lee Tanner 16 has provided <strong>the</strong> best study to date, based on an analysis <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> large<br />

Birdie Brown collection at <strong>the</strong> Colorado River Indian Tribes <strong>Museum</strong>, as well as many items<br />

from o<strong>the</strong>r private collections and museums. One <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> pieces collected by Ten Kate in 1883,<br />

and identified by him as Chemehuevi, fits well into <strong>the</strong> characterization <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Chemehuevi style<br />

<strong>of</strong> basketry as defined by Tanner.<br />

RMV 362-191<br />

RMV 362-191 is a small jar, round and bulbous in shape. It is coiled clockwise, a peculiar<br />

characteristic <strong>of</strong> Chemehuevi basketry, as are <strong>the</strong> three willow rods constituting <strong>the</strong> foundation<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> coils, which are wrapped with light-coloured willow (Salix). The Chemehuevis<br />

distinguished two species <strong>of</strong> willow, both <strong>of</strong> which were probably used for <strong>the</strong>ir basketry, and<br />

which <strong>the</strong>y called sagah and kanavi . 17 The design, applied in three horizontal bands around <strong>the</strong><br />

jar at <strong>the</strong> top, in <strong>the</strong> middle and on <strong>the</strong> bottom, is done in black devil's claw (Proboscidea<br />

al<strong>the</strong>aefolia). Each band shows a different pattern: triangles at <strong>the</strong> top; a white zigzag pattern<br />

results from two interlocking bands <strong>of</strong> black triangles around <strong>the</strong> middle; and a stepped block<br />

band surrounds <strong>the</strong> lower part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> jar. The top pattern is separated from <strong>the</strong> rim coil, and <strong>the</strong><br />

final coil is finished in black, ano<strong>the</strong>r characteristic <strong>of</strong> Chemehuevi basketry. 18<br />

Chemehuevi basketry trays (RMV 362-118, 119).<br />

13

INDIANS OF THE GREAT BASIN: THE 1883 FIELDWORK AND COLLECTION OF HERMAN TEN KATE<br />

PIETER HOVENS & JISKA HERLAAR ©<br />

Digital publications <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> National <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> Ethnology<br />

Chemehuevi basketry bowl (RMV 362-192).<br />

The o<strong>the</strong>r three Chemehuevi baskets collected by Ten Kate also fit <strong>the</strong> tribal craft as<br />

characterised by Tanner. All are coiled clockwise, using a three-rod foundation: a parching tray<br />

(RMV 362-118), a bowl with a faded pattern on <strong>the</strong> outside (RMV 362-119) and a large bowl<br />

with several block bands forming a checkered pattern (RMV 362-192). The Chemehuevis<br />

regarded designs on baskets as <strong>the</strong> personal property <strong>of</strong> weavers, and did not infringe this<br />

informal rule.<br />

Although some authors have stated that <strong>the</strong> Chemehuevis only made coiled baskets, o<strong>the</strong>rs<br />

have qualified this statement. 19 (cf. Smith and Simpson 1964:16). Ten Kate saw twined conical<br />

burden baskets and winnowing trays still being produced in 1883. He was correct in assuming<br />

that <strong>the</strong> Chemehuevis traded <strong>the</strong>ir fine basketry with o<strong>the</strong>r Colorado River tribes.<br />

RMV 5910-44<br />

14

INDIANS OF THE GREAT BASIN: THE 1883 FIELDWORK AND COLLECTION OF HERMAN TEN KATE<br />

PIETER HOVENS & JISKA HERLAAR ©<br />

Digital publications <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> National <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> Ethnology<br />

The "traditional headcloth" <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Chemehuevis mentioned by Ten Kate was probably <strong>the</strong> cap<br />

made <strong>of</strong> s<strong>of</strong>t animal skin. The white moccasins were made <strong>of</strong> deerskin 20 , and Ten Kate<br />

purchased a pair <strong>of</strong> Chemehuevi boots made from that material (RMV 362-120), as well as a<br />

pair <strong>of</strong> moccasins (RMV 362-121).<br />

Chemehuevi footwear (RMV 362-120, 121).<br />

A Chemehuevi flute (RMV 362-122), probably made <strong>of</strong> elderberry wood, is also included in his<br />

collection. 21 Finally, a Chemehuevi war club (RMV 362-193) completes <strong>the</strong> small collection he<br />

brought back from <strong>the</strong> Chemehuevi and Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Paiute territory. 22 The war club is <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

"potato masher" type, made from hardwood, and consisting <strong>of</strong> a stick with a cylindrical head. It<br />

was <strong>the</strong> principal weapon <strong>of</strong> war for <strong>the</strong> Chemehuevis, and resembled Mohave war clubs. 23<br />

The head <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Leiden club is painted yellow, with a zigzag pattern painted in red, and red<br />

points in <strong>the</strong> middle <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> triangle.<br />

Chemehuevi flute and war club (RMV 362-122 and 193).<br />

15

INDIANS OF THE GREAT BASIN: THE 1883 FIELDWORK AND COLLECTION OF HERMAN TEN KATE<br />

PIETER HOVENS & JISKA HERLAAR ©<br />

Digital publications <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> National <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> Ethnology<br />

6. The Las Vegas Paiutes<br />

Ten Kate saw <strong>the</strong> first members <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Las Vegas Paiute division when his boat stopped at<br />

Cottonwood Island to take on firewood. The fuel was delivered by <strong>the</strong> few Paiutes who lived on<br />

<strong>the</strong> island, and by that time <strong>the</strong>y had virtually stripped it <strong>of</strong> its cottonwood and mesquite trees.<br />

On <strong>the</strong> Nevada shore rose Mount X. The Indians considered this as <strong>the</strong> place where <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

former paradise was situated. According to tribal oral tradition as told to Ten Kate, when <strong>the</strong>y<br />

killed a good headman, <strong>the</strong> Great Spirit punished <strong>the</strong>m by expelling <strong>the</strong> band to <strong>the</strong> hot river<br />

valley.<br />

After <strong>the</strong>ir arrival at Eldorado Canyon, General Howard let it be known that he wanted a<br />

meeting with <strong>the</strong> local Paiutes. Ten Kate estimated an Indian population <strong>of</strong> about a hundred<br />

Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Paiutes on Cottonwood Island and at Eldorado Canyon. The meeting was<br />

unsuccessful since no interpreter was available. The bro<strong>the</strong>r <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> temporarily absent<br />

headman, although able to speak some English, declined to answer Howard’s questions. He<br />

only declared that <strong>the</strong> Paiute loved <strong>the</strong> area, and that <strong>the</strong>y had been born and raised <strong>the</strong>re,<br />

apparently fearing government plans to remove <strong>the</strong>m to a reservation. However, Ten Kate at<br />

last managed to find an informant willing to assist him in filling out <strong>the</strong> vocabulary list requested<br />

by <strong>the</strong> Bureau <strong>of</strong> American Ethnology. It is probable that this person also gave him some<br />

information about <strong>the</strong> Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Paiute way <strong>of</strong> life. Comparing his vocabularies, Ten Kate<br />

concluded that Chemehuevi and Paiute were almost identical. When he undertook fieldwork<br />

among <strong>the</strong> Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Utes in Colorado and <strong>the</strong> Comanches in Indian Territory some time later,<br />

he was convinced that <strong>the</strong>se tribal languages were related to Chemehuevi and Paiute.<br />

Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Paiute chiefs; photographed by Timothy O’Sullivan, 1871.<br />

The Paiutes called <strong>the</strong>mselves "Nu", meaning "<strong>the</strong> people". Ten Kate noted <strong>the</strong>ir small to<br />

medium stature, lean but muscular build and wiry appearance. He distinguished two physical<br />

types, <strong>the</strong> first with a flat nose, receding forehead, and prognatism (protruding lower jaw), <strong>the</strong><br />

second with a curved nose and high cheekbones, similar to <strong>the</strong> classic "Red Indian" type <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Plains. The men also shaved away <strong>the</strong> middle <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir moustaches, leaving only <strong>the</strong> ends, like<br />

<strong>the</strong> Chemehuevis.<br />

Ten Kate's Las Vegas Paiute informant(s) told him that <strong>the</strong>y still hunted mountain sheep (Ovis<br />

montana), and that grass seeds and mesquite beans were <strong>the</strong>ir main wild food resources.<br />

16

INDIANS OF THE GREAT BASIN: THE 1883 FIELDWORK AND COLLECTION OF HERMAN TEN KATE<br />

PIETER HOVENS & JISKA HERLAAR ©<br />

Digital publications <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> National <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> Ethnology<br />

Jimsonweed (Datura stramonium) was chewed, producing a state <strong>of</strong> delirium. Their dwellings<br />

were very simple, consisting only <strong>of</strong> branches. The only crafts produced at that time were willow<br />

baskets, several <strong>of</strong> which he purchased. The Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Paiutes cremated <strong>the</strong>ir dead. They were<br />

frequently at war with <strong>the</strong> Mohaves, taking scalps from <strong>the</strong>ir enemies, although <strong>the</strong> last battle<br />

had taken place more than ten years previously. The Indians considered <strong>the</strong> mountains along<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir stretch <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Colorado River to be <strong>the</strong> abodes <strong>of</strong> evil spirits.<br />

Las Vegas Paiute man with hunting weapons; photographed by John Hillers, 1872.<br />

Almost all Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Paiutes wore "citizen dress" (western dress) and only a few still wore <strong>the</strong><br />

traditional headcloth and white deerskin moccasins, <strong>the</strong> latter being exactly like those <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Chemehuevis. Paiute women had entered into unions with white men, which resulted in mixedblood<br />

<strong>of</strong>fspring. A number <strong>of</strong> Paiute men were employed at <strong>the</strong> smelter in Eldorado Canyon,<br />

where silver was extracted from excavated rocks. O<strong>the</strong>r Paiutes earned <strong>the</strong>ir living by ga<strong>the</strong>ring<br />

firewood and selling it to <strong>the</strong> smelter and <strong>the</strong> steamboat captains. Excessive consumption <strong>of</strong><br />

alcohol was a serious problem, but <strong>the</strong> white American traders pr<strong>of</strong>ited from this trade, a<br />

situation criticized by Ten Kate.<br />

Las Vegas Paiute women; photographed by John Hillers, 1873.<br />

On May 18 Ten Kate departed down river to continue his fieldwork, which would take him to <strong>the</strong><br />

Pimas, Apaches, Pueblos, Navajos, Hopis, Zunis, Utes, Cheyennes and Comanches and <strong>the</strong><br />

deported Sou<strong>the</strong>astern tribes in Indian Territory. 24<br />

17

INDIANS OF THE GREAT BASIN: THE 1883 FIELDWORK AND COLLECTION OF HERMAN TEN KATE<br />

PIETER HOVENS & JISKA HERLAAR ©<br />

Digital publications <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> National <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> Ethnology<br />

7. Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Paiute basketry<br />

Among <strong>the</strong> Las Vegas Paiutes Ten Kate collected three twined baskets: a small conical<br />

carrying or seed basket, probably meant for a girl (RMV 362-123); a winnowing tray (RMV 362-<br />

124); and a small basket or woman's hat with two decorative bands. 25<br />

Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Paiute basketry (RMV 362-124, 125 and 123).<br />

Twining is one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> oldest techniques with which plant fibres are woven into a variety <strong>of</strong><br />

shapes, degrees <strong>of</strong> rigidity, and products, from flexible mats and bags to sturdy baskets and<br />

sandals. The winnowing tray was used to separate chaff and shells from seeds and nuts that<br />

were collected during <strong>the</strong> harvest season. The loosening <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> chaff and opening <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

pinenuts was accomplished by mixing hot charcoal with <strong>the</strong> seeds and nuts on <strong>the</strong> trays, and<br />

rhythmically tossing <strong>the</strong> contents <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> tray into <strong>the</strong> air, continuing for as long as it took to<br />

dispose <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> chaff and shells or to open <strong>the</strong> pinenuts. This required dexterity and<br />

attentiveness from <strong>the</strong> women, to avoid burning <strong>the</strong> trays. Depending on specific requirements,<br />

winnowing trays were woven tightly or open, in <strong>the</strong> latter case also functioning as a sieve.<br />

Conical carrying baskets came in all sizes, from small ones used by little girls imitating and<br />

helping <strong>the</strong>ir mo<strong>the</strong>rs in ga<strong>the</strong>ring a wide variety <strong>of</strong> edible seeds, to large ones used for carrying<br />

all kinds <strong>of</strong> household goods. 26 18

INDIANS OF THE GREAT BASIN: THE 1883 FIELDWORK AND COLLECTION OF HERMAN TEN KATE<br />

PIETER HOVENS & JISKA HERLAAR ©<br />

Digital publications <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> National <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> Ethnology<br />

8. The Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Utes<br />

After a visit to <strong>the</strong> Zunis, Ten Kate stayed in Santa Fe until 17 September 1883. He had<br />

planned a visit to <strong>the</strong> Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Utes in Colorado, after which he wanted to continue his journey<br />

by way <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> small town <strong>of</strong> Trinidad in Colorado, eastward through Kansas to Indian Territory.<br />

During this trip he had also planned to visit <strong>the</strong> Jicarilla Apaches who lived near <strong>the</strong> Utes, but<br />

<strong>the</strong> federal government had transferred <strong>the</strong>m to a new reservation at Fort Stanton, where <strong>the</strong><br />

Mescalero Apaches already lived. Ten Kate took <strong>the</strong> mail coach to Española on <strong>the</strong> Rio Grande<br />

River, in order to take <strong>the</strong> train through <strong>the</strong> mountains to Ignacio, <strong>the</strong> Ute Indian Agency. En<br />

route he saw pioneers in large wagons, heavily loaded with <strong>the</strong>ir belongings, pulled along by<br />

oxen. In Antonito, Colorado, he came upon a public trial in progress, but instead <strong>of</strong> watching it<br />

he decided to look for a place in which to have dinner and spend <strong>the</strong> night. The next day Ten<br />

Kate travelled through <strong>the</strong> mountains on <strong>the</strong> Denver & Rio Grande Railway by way <strong>of</strong> Chama<br />

and Amargo, <strong>the</strong> former Indian Agency <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Jicarilla Apaches. In Ignacio he took a buckboard<br />

to meet <strong>the</strong> Indian Agent, Warren Patten, in his <strong>of</strong>fice, where he also met an Indian Inspector.<br />

Patten was aptly named “Crosseye” by <strong>the</strong> Utes. The inspector commanded little respect since<br />

Ten Kate disparagingly remarked that his inspection <strong>of</strong> conditions on <strong>the</strong> reservation remained<br />

limited to <strong>the</strong> <strong>of</strong>fice <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Indian Agent.<br />

Ten Kate spent about ten days on <strong>the</strong> Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Ute Indian Reservation. He enjoyed Ignacio<br />

because <strong>of</strong> its splendid location on <strong>the</strong> banks <strong>of</strong> Rio de Los Pinos, its high elevation with <strong>the</strong><br />

invigorating mountain air, and <strong>the</strong> surrounding tree-clad mountains. He visited <strong>the</strong> nearby Indian<br />

encampment several times, travelled throughout <strong>the</strong> reservation on horseback to o<strong>the</strong>r camps,<br />

sometimes accompanying <strong>the</strong> agency physician Dr. White, and was present during an issueday<br />

when government rations were being distributed among <strong>the</strong> Indians, mainly beef and flour<br />

on this occasion. Much <strong>of</strong> this time he was accompanied by John Taylor, an Afro-American who<br />

had lived among <strong>the</strong> Utes for two or three years, and who worked for <strong>the</strong> army and agency as<br />

an interpreter. On all <strong>the</strong>se occasions Ten Kate made notes <strong>of</strong> his observations and his<br />

conversations with individual Utes, who included Chiefs Ignacio, Severo, Buckskin Charley and<br />

Aguila.<br />

Chief Severo and his family, c. 1890; Detroit Photographic Company.<br />

19

INDIANS OF THE GREAT BASIN: THE 1883 FIELDWORK AND COLLECTION OF HERMAN TEN KATE<br />

PIETER HOVENS & JISKA HERLAAR ©<br />

Digital publications <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> National <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> Ethnology<br />

Ten Kate stayed with <strong>the</strong> Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Utes until 27 September and, after a four-day trip into <strong>the</strong><br />

Rocky Mountains, he took <strong>the</strong> train to Indian Territory on 1 October, travelling by way <strong>of</strong><br />

Cucharas and Trinidad. 27 On <strong>the</strong> basis <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> literature available to him, and his observations<br />

and conversations on <strong>the</strong> reservation, Ten Kate composed a sketch <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Utes.<br />

The Utes called <strong>the</strong>mselves “Noots” or "Yutas", and were a powerful nomadic tribe living in<br />

Western Colorado, and before 1868 in large parts <strong>of</strong> Wyoming, Utah and New Mexico. A sou<strong>the</strong>astern<br />

group <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Utes lived adjacent to <strong>the</strong> Kiowas in nor<strong>the</strong>rn Texas on <strong>the</strong> Cimarron<br />

River. Some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir major tribes are <strong>the</strong> Uncompagres and Tabewaches, Wimenuches,<br />

Capotes and Muaches. The former two were transferred to <strong>the</strong> Uintah and Ouray reservations<br />

in north-east Utah in 1880. The Capotes and Muaches who used to live in nor<strong>the</strong>rn New Mexico<br />

were forced to live in south-western Colorado toge<strong>the</strong>r with <strong>the</strong> Wimenuches, and from <strong>the</strong>n on<br />

<strong>the</strong>y were called <strong>the</strong> Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Utes, numbering approximately a thousand people on <strong>the</strong><br />

reservation at <strong>the</strong> time <strong>of</strong> Ten Kate's visit.<br />

The Utes belong to <strong>the</strong> Numic-speaking family along with <strong>the</strong> Paiutes, Hopis and <strong>the</strong><br />

Comanches. Their language was considered a difficult one for white people to learn, although<br />

Ten Kate’s Afro-American interpreter John Taylor had mastered it, and Ten Kate thought it was<br />

easier than Apache and Navaho to put into writing. After <strong>the</strong> enemies <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Utes pushed <strong>the</strong>m<br />

into <strong>the</strong> Rocky Mountains <strong>the</strong>y gradually lost <strong>the</strong>ir use <strong>of</strong> sign language. Ten Kate spoke<br />

Spanish with <strong>the</strong> Utes, a language most tribesmen could speak reasonably well. Only a few<br />

Utes knew some English words, but he predicted that English would soon replace Spanish,<br />

since <strong>the</strong> numbers <strong>of</strong> American settlers surrounding <strong>the</strong>ir reservation were increasing at a rapid<br />

rate.<br />

Chief Buckskin Charley, Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Ute; lithograph by Pieter Haaxman (1885)<br />

after a photograph by Mat<strong>the</strong>w Brady, c. 1880.<br />

Ten Kate encountered <strong>great</strong> difficulties in measuring <strong>the</strong> Utes, who appeared to be scared and<br />

recalcitrant. Because <strong>of</strong> his frequent visits to <strong>the</strong> camps, assisting <strong>the</strong> agency physician, he was<br />

able to overcome distrust and resistance to a certain extent, and eventually was able to<br />

measure ten men, whom he remunerated with money and tobacco. Women could not be<br />

20

INDIANS OF THE GREAT BASIN: THE 1883 FIELDWORK AND COLLECTION OF HERMAN TEN KATE<br />

PIETER HOVENS & JISKA HERLAAR ©<br />

Digital publications <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> National <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> Ethnology<br />

persuaded to submit to somatological measurements. The imposing Chief Ignacio and Chief<br />

Severo also refused Ten Kate’s requests, and <strong>the</strong> latter chief engaged him in a discussion on<br />

his views on physical types, while <strong>the</strong> anthropologist tried to enlighten <strong>the</strong> chief about scientific<br />

<strong>the</strong>ories in <strong>the</strong> field <strong>of</strong> comparative ethnic anatomy, albeit with little success.<br />

The anthropologist encountered two main physical types among <strong>the</strong> Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Utes, and<br />

countless intermediate types. Ten Kate had never seen <strong>the</strong> first type before, but he was to<br />

encounter it later among <strong>the</strong> Kiowas. It was distinctive because <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> large proportion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

face compared to <strong>the</strong> skull, and because <strong>of</strong> a slightly heavy, straight or somewhat upturned<br />

nose. A strongly receding forehead and heavy eyebrow ridges were also characteristic. The<br />

torso and arms were very muscular, <strong>the</strong> neck short, <strong>the</strong> shoulders broad and square. Although<br />

representatives <strong>of</strong> this type were above medium height, <strong>the</strong>y appeared compact and massive.<br />

Some Utes were distinctly stout. They had light eyes and a light skin complexion. The second<br />

type was <strong>the</strong> “Red Indian type” found predominantly on <strong>the</strong> Plains. Ten Kate encountered those<br />

two types among half <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Ute population; <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r half consisted <strong>of</strong> varying intermediate<br />

types. Some Utes had thick, wavy hair. Based on his observations <strong>of</strong> physical types, Ten Kate<br />

also assumed that relations had been intimate with Jemez Pueblo and <strong>the</strong> Jicarilla and Tonto<br />

Apaches. He also thought he detected influences from Jemez on Ute dress, and noted that a<br />

Ute dance was known in <strong>the</strong> pueblo. Intermarriage with <strong>the</strong> Jicarillas was common.<br />

Among <strong>the</strong> Utes <strong>the</strong>re were no children <strong>of</strong> mixed blood, since <strong>the</strong>re were virtually no sexual<br />

relations between Utes and whites. Mixed <strong>of</strong>fspring were killed after birth, a fate that also befell<br />

<strong>the</strong> children <strong>of</strong> Afro-American John Taylor, and Chief Ignacio told Ten Kate that <strong>the</strong> children<br />

with <strong>the</strong> buffalo hair were killed immediately after <strong>the</strong>y were born. Sexual relations between Ute<br />

men and women were liberal according to Ten Kate, and <strong>the</strong>re were marriages between Utes<br />

and o<strong>the</strong>r Native Americans. Chief Ouray’s mo<strong>the</strong>r was a Jicarilla Apache.<br />

Chief Ouray and his wife Chipita, 1880. Photograph by<br />

Ma<strong>the</strong>w Brady, Washington D.C.<br />

21

INDIANS OF THE GREAT BASIN: THE 1883 FIELDWORK AND COLLECTION OF HERMAN TEN KATE<br />

PIETER HOVENS & JISKA HERLAAR ©<br />

Digital publications <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> National <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> Ethnology<br />

Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Utes, Ignacio, Colorado, c. 1890; photographed by Rose and Hopkins.<br />

The Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Utes appeared to be generally healthy, although many people suffered from<br />

goitre, possibly from a lack <strong>of</strong> iodine. O<strong>the</strong>rs showed signs <strong>of</strong> an advanced stage <strong>of</strong> syphilis.<br />

Acute rheumatism seemed to be <strong>the</strong> dominant illness, probably because <strong>of</strong> <strong>great</strong> fluctuations in<br />

temperatures, high humidity and life outdoors.<br />

Ute men were responsible for providing <strong>the</strong>ir family with meat and hides, and Ten Kate<br />

repeatedly saw men leaving to hunt deer, <strong>of</strong>ten staying away for several days, sometimes<br />

even weeks. They had virtually discarded bows and arrows, and instead used Sharp,<br />

Winchester and Ballard rifles. Prairie dogs (Cynomys) were part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir diet, and <strong>the</strong>y hunted<br />

fowl, grouse (Canaces) being a favourite prey. Fishing was also common, and <strong>the</strong> mountain<br />

streams were rich in trout. Women were engaged in household duties: storing food,<br />

preparing meals, making clothing, applying beadwork, and looking after <strong>the</strong> youngest<br />

children. In pre-reservation times <strong>the</strong> women also ga<strong>the</strong>red edible plants, including <strong>the</strong><br />

cambium layer <strong>of</strong> pine trees, which contained sugar. During leisure time Ute men and<br />

women engaged in playing cards. The men also danced, accompanied by a drum. Target<br />

shooting with Sharp rifles was a favourite pastime, as were horse races, accompanied by<br />

serious betting with Navajo blankets, mountain-lion skins and weapons. Navajo Indians were<br />

among <strong>the</strong> spectators, and stood out against <strong>the</strong> Utes because <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>great</strong>er height. The<br />

mood during <strong>the</strong>se races was quiet and modest, a far cry from <strong>the</strong> boisterous atmosphere<br />

among white men at horse races.<br />

The Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Utes did not farm, and refused to begin farming, despite persistent<br />

encouragement from <strong>the</strong> government. However, Ten Kate noted that <strong>the</strong>y had little choice<br />

since <strong>the</strong> deer population decreased rapidly through over-hunting. Never<strong>the</strong>less, <strong>the</strong><br />

mountain region did not permit farming on a large scale. Government rations were a shortterm<br />

solution, and buying food at <strong>the</strong> traders’ stores required cash, something which <strong>the</strong> Utes<br />

had difficulty obtaining, except when <strong>the</strong>y sold horses; <strong>the</strong>y owned approximately 2200 <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong>se animals, all <strong>of</strong> good quality. They also owned a hundred cows and a thousand sheep<br />

that had been given to <strong>the</strong>m by <strong>the</strong> government under <strong>the</strong> treaty provisions. These animals<br />

were herded on horseback by both men and women.<br />

22

INDIANS OF THE GREAT BASIN: THE 1883 FIELDWORK AND COLLECTION OF HERMAN TEN KATE<br />

PIETER HOVENS & JISKA HERLAAR ©<br />

Digital publications <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> National <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> Ethnology<br />

Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Utes crossing <strong>the</strong> Los Pinos River, Colorado, c. 1890; photographed by H.S. Poley.<br />

Ten Kate found <strong>the</strong> issue or ration day quite spectacular. The cattle provided by <strong>the</strong><br />

government was driven toge<strong>the</strong>r in a pen, and shot one by one by an agency employee and<br />

a Ute Indian. Each Indian family <strong>the</strong>n dashed towards <strong>the</strong> animal assigned to it, and began<br />

butchering it, <strong>the</strong> women skinning <strong>the</strong> carcasses with agility and speed. While <strong>the</strong> ground<br />

was soaking with blood, on which <strong>the</strong> dogs tried to feast, <strong>the</strong> Indians cut up <strong>the</strong> animals,<br />

meanwhile eating parts <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> innards while <strong>the</strong>y were still warm. Only <strong>the</strong> livers were<br />

discarded.<br />

The Utes were fierce and courageous warriors, but <strong>the</strong>y also had a reputation for chivalry. Their<br />

enemies were many, especially neighbouring tribes such as <strong>the</strong> Comanches, Cheyennes,<br />

Arapahos, and Kiowas with whom <strong>the</strong>y competed in hunting buffalo on <strong>the</strong> Plains. Chief Aguila<br />

revelled in his stories about raids he had undertaken, and attributed his robust torso to <strong>the</strong><br />

brains from a slain Cheyenne enemy he had eaten. In more recent times <strong>the</strong> Utes’ principal<br />

enemy was <strong>the</strong> white man, and settlers continued to encroach onto <strong>the</strong>ir lands.<br />

Ten Kate’s efforts to obtain information on <strong>the</strong> social organization <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Utes proved<br />

fruitless, due to <strong>the</strong> evasive and conflicting information given by informants, and <strong>the</strong> complete<br />

lack <strong>of</strong> knowledge and disinterest on <strong>the</strong> part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Indian Agent and his staff.<br />

Through his visits to Indian camps, and <strong>the</strong> assistance he gave to <strong>the</strong> sick and wounded, Ten<br />

Kate had gained some trust among <strong>the</strong> Utes, at least among <strong>the</strong> chiefs. They tactfully inquired<br />

what he thought <strong>of</strong> Warren "Crosseye" Patten, <strong>the</strong> Indian Agent, and <strong>the</strong> Indian Inspector from<br />

Washington. The agent commanded little respect, and during Ten Kate’s stay was physically<br />

attacked by Ojo Blanco, a prominent warrior who was inebriated at <strong>the</strong> time <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> incident. Ute<br />

Indian policemen who witnessed <strong>the</strong> event were at first reluctant to act, but armed intervention<br />

by <strong>the</strong> agency’s cook brought <strong>the</strong>m into action.<br />

Agency personnel and white settlers were wary <strong>of</strong> Indian resentment <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> invasion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

homeland. They warned Ten Kate not to search for Indian skeletal remains, as this might cause<br />

violent opposition, or even worse. The anthropologist shared <strong>the</strong>ir fears but had to perform his<br />

scientific duty. He was very circumspect, but also unsuccessful, since <strong>the</strong> Utes buried <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

dead under rocks and branches, a perfect camouflage. When agency staff saw a fire signal on<br />

one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> mountain tops one evening, <strong>the</strong>y came running to Ten Kate and blamed him for<br />

causing an Indian uprising. However, nothing happened.<br />

23

INDIANS OF THE GREAT BASIN: THE 1883 FIELDWORK AND COLLECTION OF HERMAN TEN KATE<br />

PIETER HOVENS & JISKA HERLAAR ©<br />

Digital publications <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> National <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> Ethnology<br />

To Ten Kate <strong>the</strong> Utes appeared "carefree and cheerful", though not as "childlike and benign" as<br />

<strong>the</strong> Mohaves and Yumas. He attributed this difference in character to <strong>the</strong> Utes' more difficult<br />

living environment with its harsh winters, time-consuming and exhausting hunting as part <strong>of</strong><br />

daily life, and <strong>the</strong> fact that being surrounded by enemies made life ra<strong>the</strong>r perilous at times.<br />

24

INDIANS OF THE GREAT BASIN: THE 1883 FIELDWORK AND COLLECTION OF HERMAN TEN KATE<br />

PIETER HOVENS & JISKA HERLAAR ©<br />

Digital publications <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> National <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> Ethnology<br />

9. Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Ute art and material culture<br />

Among <strong>the</strong> Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Utes Ten Kate made many observations on <strong>the</strong>ir material culture. Ute<br />

men wore skin leggings and moccasins, <strong>the</strong> former beautifully decorated with beadwork, and<br />

with broad flapping panels along <strong>the</strong> seams. The moccasins were decorated with blue and<br />

white beads. In addition <strong>the</strong> Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Utes dressed in western-style shirts and waistcoats, worn<br />

hanging loose. Some men wore small medicine bags as amulets, pinned to <strong>the</strong>ir clo<strong>the</strong>s not far<br />

from <strong>the</strong>ir armpits (near <strong>the</strong> heart?). Some wore western-style hats. The women dressed in<br />

long robes, extending to mid-calf. Occasionally <strong>the</strong>se were still made from lea<strong>the</strong>r, but<br />

increasingly from cotton and linen. Underneath <strong>the</strong> women wore plain lea<strong>the</strong>r leggings and<br />

undecorated moccasins.<br />

The men wore <strong>the</strong>ir hair parted in <strong>the</strong> middle or on <strong>the</strong> side in two long braids. The ends <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

braids were wrapped with otter fur or red ribbons. The hair parting was <strong>of</strong>ten painted red or<br />

yellow. The women wore <strong>the</strong>ir hair loose on <strong>the</strong>ir back, shoulders and chest, usually parted in<br />

<strong>the</strong> middle and shorter than <strong>the</strong> men wore <strong>the</strong>irs. Most Ute men, especially <strong>the</strong> young<br />

generation, painted <strong>the</strong>ir entire faces with red and yellow pigment. They also plucked <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

eyebrows and eyelashes. The pigments were kept in a long flat skin bag decorated with glass<br />

beads.<br />

Their jewellery consisted <strong>of</strong> breastplates, necklaces made from beads and seashell (plastrons),<br />

finger rings, earrings and bracelets made <strong>of</strong> sterling silver or "Berlin silver", a low-grade zincsilver<br />

alloy. The beads and ground shells were sold at <strong>the</strong> trader’s store. The seashells were<br />

white, and reminded Ten Kate <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> shells used on wampum belts he had seen. The valuable<br />

seashells were collected and fashioned for this purpose in <strong>the</strong> eastern United States and sent<br />

to trader's stores all across <strong>the</strong> American West.<br />

The Navajos made silver jewellery for <strong>the</strong> Utes using <strong>the</strong> American silver dollars <strong>the</strong> Utes gave<br />

<strong>the</strong>m. For <strong>the</strong>ir horses <strong>the</strong> Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Utes also had harnesses and saddles decorated with<br />

silverwork, provided by Navajo silversmiths. The saddles, made <strong>of</strong> wood and covered with<br />

rawhide, were used only by women. The saddles had a large knob at <strong>the</strong> front and back<br />

decorated with long fringes <strong>of</strong> s<strong>of</strong>t white lea<strong>the</strong>r.<br />

Most Utes still lived in tipis. These were no longer made from buffalo hide, because <strong>the</strong> Indians<br />

were no longer allowed to hunt buffalo. The conical tents were now made from white or yellow<br />

canvas received from <strong>the</strong> US government. Utes still painted <strong>the</strong>ir kani (tipis) with war and<br />

hunting scenes, and signs that could only be interpreted by insiders. Smoke rose from <strong>the</strong> open<br />

tops into <strong>the</strong> mountain air. In <strong>the</strong> tipis Ten Kate saw Navajo and American blankets, animal<br />

hides, items <strong>of</strong> dress, weapons, household goods, and food all stored around <strong>the</strong> perimeter,<br />

while a fire burned in <strong>the</strong> centre. He mentions <strong>the</strong> use <strong>of</strong> brightly painted "parflèches"<br />

(rectangular rawhide containers) for storing dried meat and parflèche cylinders for storing small<br />

and ceremonial items. He also saw baskets and basketry water jars, which reminded him <strong>of</strong><br />

Apache basketry. Babies and small children were carried around in cradle boards made <strong>of</strong> a<br />

wooden backboard, covered with lea<strong>the</strong>r. The headboard was wide to protect <strong>the</strong> child’s head,<br />

and gave <strong>the</strong> cradle a bulky appearance. Outside each tipi stood a tripod on which <strong>the</strong> owner<br />

usually kept his best clo<strong>the</strong>s and equipment, to avoid soiling and damage.<br />

Among <strong>the</strong> Utes Ten Kate observed <strong>the</strong> use <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> "calumet", <strong>the</strong> Indian pipe. According to<br />

his informants <strong>the</strong> Utes used to make <strong>the</strong>ir pipe bowls from a s<strong>of</strong>t stone found near <strong>the</strong><br />

Cimarron River in New Mexico. However, this practice was discontinued, since it was much<br />

easier to obtain pipe bowls through trade with <strong>the</strong> Comanches, who in turn received <strong>the</strong>m<br />

through intertribal trade from <strong>the</strong>ir original source, <strong>the</strong> catlinite pipestone quarries <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

25

INDIANS OF THE GREAT BASIN: THE 1883 FIELDWORK AND COLLECTION OF HERMAN TEN KATE<br />

PIETER HOVENS & JISKA HERLAAR ©<br />

Digital publications <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> National <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> Ethnology<br />

Sioux in southwestern Minnesota. The pipes were valued possessions. When Ten Kate tried<br />

to buy a pipe, pipe bag and beaded tobacco pouch from a Ute man, <strong>the</strong> owner wanted a<br />

horse in exchange, a price <strong>the</strong> anthropologist could not afford, much to his regret.<br />

Chief Peah and family on Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Ute Reservation; photographed by William Henry Jackson, 1874.<br />

Among <strong>the</strong> Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Utes Ten Kate collected a wheat loaf and five artifacts: a purse, an awl<br />

case, a paint bag, a parflèche, and a tubular rawhide case. All were decorated with ei<strong>the</strong>r<br />

beadwork or paint, and <strong>the</strong> specimens exemplify <strong>the</strong> strong Plains influence on <strong>the</strong> material<br />

culture <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Utes. The Utes closest to <strong>the</strong> Spanish settlements in <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn Rio<br />

Grande Valley had begun to acquire horses before <strong>the</strong> mid-seventeenth century, and used<br />

<strong>the</strong>se initially as beasts <strong>of</strong> burden. After <strong>the</strong> Pueblo Revolt <strong>of</strong> 1680 <strong>the</strong> number <strong>of</strong> Ute horses<br />

increased as <strong>the</strong> result <strong>of</strong> trade. In <strong>the</strong> course <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> next century <strong>the</strong> most easterly <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Ute<br />

groups became equestrian nomads, living in tipis, hunting buffalo on <strong>the</strong> Plains, raiding for<br />

horses, and racing horses as a favourite pastime. However, after 1830 <strong>the</strong>y were pushed back<br />

to <strong>the</strong> west by High Plains tribes, but in <strong>the</strong>ir way <strong>of</strong> life <strong>the</strong>y continued <strong>the</strong> Plains pattern <strong>of</strong><br />

equestrian nomadism as far as possible. Increasingly <strong>the</strong>y hunted elk and deer, kept up a<br />

reputation as fierce warriors, and retained <strong>the</strong> Plains type <strong>of</strong> material culture. 28<br />

The awl case (RMV 362-20) Ten Kate collected in 1883 at <strong>the</strong> Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Ute Indian Agency was<br />

unfortunately stolen in 1964 during an exhibition on <strong>the</strong> Plains Indians at <strong>the</strong> Leiden museum. It<br />

was beaded in white, yellow, blue, green and red, and a snake design ran down both sides,<br />

outlined once in red, once in black beads, oppositional colours in Ute colour symbolism. Red is<br />

associated with protection, represented in animal life by <strong>the</strong> weasel, while black stands for <strong>the</strong><br />

negative power <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> rattlesnake, and symbolizes <strong>the</strong> underworld. 29 The Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Ute “purse”<br />

(RMV 362-19) Ten Kate acquired is much too small and tight to hold coins or ration tickets, and<br />