Intercultural competence as an aspect of the communicative ...

Intercultural competence as an aspect of the communicative ...

Intercultural competence as an aspect of the communicative ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

UNIVERSITY OF NOVI SAD<br />

FACULTY OF PHILOSOPHY<br />

ENGLISH DEPARTMENT<br />

<strong>Intercultural</strong> <strong>competence</strong> <strong>as</strong> <strong>an</strong> <strong>as</strong>pect <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>communicative</strong> <strong>competence</strong> in<br />

<strong>the</strong> tertiary level English l<strong>an</strong>guage learners<br />

DOCTORAL DISSERTATION<br />

Supervisor: Gord<strong>an</strong>a Petričić, <strong>as</strong>sist<strong>an</strong>t pr<strong>of</strong>essor<br />

PhD c<strong>an</strong>didate: Nina Lazarević, MA<br />

Novi Sad, 2013

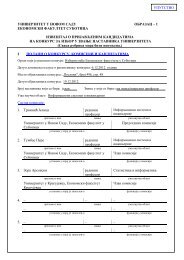

UNIVERZITET U NOVOM SADU<br />

FILOZOFSKI FAKULTET<br />

KLJUČNA DOKUMENTACIJSKA INFORMACIJA<br />

Redni broj:<br />

RBR<br />

Identifikacioni broj:<br />

IBR<br />

Tip dokumentacije:<br />

TD<br />

Tip zapisa:<br />

TZ<br />

Vrsta rada (dipl., mag., dokt.):<br />

VR<br />

Ime i prezime autora:<br />

AU<br />

Mentor (titula, ime, prezime,<br />

zv<strong>an</strong>je):<br />

MN<br />

N<strong>as</strong>lov rada:<br />

NR<br />

Jezik publikacije:<br />

JP<br />

Jezik izvoda:<br />

JI<br />

Zemlja publikov<strong>an</strong>ja:<br />

ZP<br />

Uže geografsko područje:<br />

UGP<br />

Godina:<br />

GO<br />

Izdavač:<br />

IZ<br />

Mesto i adresa:<br />

MA<br />

Monografska dokumentacija<br />

Tekstualni štamp<strong>an</strong>i materijal<br />

Doktorska disertacija<br />

Nina Lazarević<br />

Dr Gord<strong>an</strong>a Petričić, docent, Odsek za <strong>an</strong>glistiku<br />

Interkulturna kompetencija kao <strong>as</strong>pekt<br />

komunikativne kompetencije učenika engleskog<br />

jezika na tercijalnom nivou<br />

engleski<br />

srpski / engleski<br />

Srbija<br />

Vojvodina<br />

2013.<br />

autorski reprint<br />

Novi Sad, Zor<strong>an</strong>a Đinđića 2

Fizički opis rada:<br />

FO<br />

6 poglavlja / 301 str<strong>an</strong>ica /19 slika / 45 tabela /<br />

368 referenci /11 priloga<br />

Naučna obl<strong>as</strong>t:<br />

NO<br />

Naučna disciplina:<br />

ND<br />

Predmetna odrednica, ključne reči:<br />

PO<br />

UDK<br />

Čuva se:<br />

ČU<br />

Lingvistika, primenjena lingvistika<br />

Interkulturna kompetencija<br />

interkulturna kompetencija, interkulturna svest,<br />

interkulturna osetljivost, kulturni <strong>as</strong>imilator,<br />

kritički incident, n<strong>as</strong>tava engleskog jezika kao<br />

str<strong>an</strong>og<br />

Biblioteka Odseka za <strong>an</strong>glistiku, Filoz<strong>of</strong>ski<br />

fakultet, Univerzitet u Novom Sadu<br />

Važna napomena:<br />

VN<br />

Izvod:<br />

IZ<br />

Ciljevi n<strong>as</strong>tave engleskog jezika su se promenili kako su međusobna povez<strong>an</strong>ost i moblinost<br />

ljudi koje karakterišu moderni svet r<strong>as</strong>le. Interkulturna kompetencija se pojavljuje kao još jed<strong>an</strong> uz već<br />

postavljene ciljeve lingvističke i komunikativne kompetencije u n<strong>as</strong>tavi str<strong>an</strong>ih jezika. Ipak, primena<br />

teorije interkulturne kompentencije u n<strong>as</strong>tavi str<strong>an</strong>ih jezika nije z<strong>as</strong>tupljena u velikom obimu i „malo<br />

pažnje pridaje se istraživ<strong>an</strong>ju konceptualizacije interkulturne interakcije“ (Spencer-Oatey, Fr<strong>an</strong>klin<br />

2009: 63,64). Iako postoji „potreba na svetskom nivou da diplomir<strong>an</strong>i studenti budu „građ<strong>an</strong>i sveta“, i<br />

da budu „svesni sveta““ (Paige, Goode 2009: 333), tehnike koje se primenjuju u n<strong>as</strong>tavi nisu<br />

najpogodnije za razvij<strong>an</strong>je afektivne i bihevioralne komponente interkulturne kompetencije. Štaviše,<br />

n<strong>as</strong>tavnici nemaju potrebnu teorijsku i praktičnu osnovu i nisu uvek spremni da uključe interkulturnu<br />

kompetenciju u n<strong>as</strong>tavu engleskog jezika (Byram 1997), a istraživ<strong>an</strong>ja koja bi trebalo da pomognu<br />

n<strong>as</strong>tavu u velikoj meri usmerena su na programe studir<strong>an</strong>ja u inostr<strong>an</strong>stvu, i tek m<strong>an</strong>ji broj studija bavi<br />

se interkulturnom kompetencijom u kontekstu engleskog kao str<strong>an</strong>og jezika (Pl<strong>an</strong>ken et al. 2004,<br />

Korhonen 2004, Lundgren 2009, Lázár 2007). U Srbiji je polje interkulturne kompetencije relativno<br />

novo i mali je broj istraživ<strong>an</strong>ja koja idu dalje od problema stereotipa (Cvetič<strong>an</strong>in, Paunović 2007,<br />

Lazarević, Savić 2009, Paunović 2011).<br />

Disertacija je imala za cilj da da uvid u interkulturnu kompetenciju studenata Univerziteta u<br />

Nišu, sa posebnim osvrtom na pedagoške implikacije za n<strong>as</strong>tavnu praksu na univerzitetskom nivou.<br />

Drugo, cilj istraživ<strong>an</strong>ja bio je da se istraže i faktori koji mogu imati uticaja na nju. Stoga je posebna<br />

pažnja data sposobnosti ispit<strong>an</strong>ika da obj<strong>as</strong>ne određene interkulturne nesporazume.<br />

U tu svrhu u istraživ<strong>an</strong>ju je korišćen kulturni <strong>as</strong>imilator kao najčešća tehnika koja u prvi pl<strong>an</strong><br />

stavlja stavove studenata, a koristi se i za n<strong>as</strong>tavu i za ocenjiv<strong>an</strong>je. Asimilator koji je istraživač napravio<br />

upravo za ovo istraživ<strong>an</strong>je z<strong>as</strong>nov<strong>an</strong> je na dva pristupa: empirijskom (intervjui sa izvornim govornicima<br />

engleskog jezika) i teoretskom (Bennett 1993, Cushner, Brislin 1996, Fowler 1995, Hall 1966, H<strong>of</strong>stede<br />

1984, Lambert <strong>an</strong>d Myers 1994, Trompenaars, Hampden-Turner 1997).<br />

Kako je interkulturna kompetencija suštinski kompleks<strong>an</strong> koncept, istraživ<strong>an</strong>je je bilo ne samo<br />

deskriptivno već i eksploratorno te koristilo kombinov<strong>an</strong>u metodu (Teddlie, T<strong>as</strong>hakkori 2009), kako bi<br />

pružilo bolje razumev<strong>an</strong>je interkulturne kompetencije. U svrhu prikuplj<strong>an</strong>ja podataka, iskorišćen je<br />

st<strong>an</strong>dardizov<strong>an</strong>i upitnik koji se koristi za ispitiv<strong>an</strong>je interkulturne osetljivosti, a koji su popunili studenti<br />

sa deset departm<strong>an</strong>a (koji su takođe pohađali i kurs engleskog jezika) kako bi se dobile informacije o<br />

raznolikoj i velikoj grupi. U kvalitativnoj fazi korišćeni su kritički incidenti iz kulturnog <strong>as</strong>imilatora u<br />

intervjuima sa dv<strong>an</strong>aest studenata sa različitih departm<strong>an</strong>a kako bi se dobili podaci o kognitivnom i<br />

donekle bihevioralnom i afektivnom domenu interkulturne kompetencije ispit<strong>an</strong>ika. Za <strong>an</strong>alizu podataka<br />

korišćeni su statistički testovi u kv<strong>an</strong>titativnoj, a <strong>an</strong>aliza sadržaja i kodir<strong>an</strong>je u kvalitativnoj fazi.<br />

Rezultati pokazuju neslag<strong>an</strong>je između kv<strong>an</strong>titativnih i kvalitativnih rezultata. Prvi pokazuju<br />

relativno visok stepen interkulturne perspektive, što ukazuje na viši nivo prihvat<strong>an</strong>ja kulturno različitih<br />

perspektiva, sigurnost u interkulturnim susretima kao i senzitivnost prema kontekstu koji je kulturno<br />

raznolik. S druge str<strong>an</strong>e, kvalitativni podaci daju skoro dijametralno suprotne rezultate, pokazujući

određen nedostatak interkulturne kompetencije jer su ispit<strong>an</strong>ici uglavnom koristili kulturne okvire<br />

sopstvene kulture kako bi obj<strong>as</strong>nili interkulturne susrete i pribegavali stereotipima, generalizacijama i<br />

atribucijama z<strong>as</strong>nov<strong>an</strong>im na ličnim karakterisitkama.<br />

Mada je bilo m<strong>an</strong>jih razlika u kv<strong>an</strong>titativnim rezultatima za različite departm<strong>an</strong>e, kvalitativni<br />

podaci ih nisu pokazali, već su kod ispitatnika ukazali na nisku interkulturnu senzitivnost i empatiju kao<br />

i karakteristike faza Odbr<strong>an</strong>a i Minimalizacija (Bennett 1993) kod studenata skoro svih departm<strong>an</strong>a.<br />

I kvalitativni i kv<strong>an</strong>titativni rezultati pokazuju da faktori kao što su boravak u inostr<strong>an</strong>stvu,<br />

poznav<strong>an</strong>je drugih str<strong>an</strong>ih jezika i pol nemaju značaj<strong>an</strong> uticaj na interkulturnu kompetenciju. Takođe se<br />

pokazalo da intenzivna n<strong>as</strong>tava engleskog jezika sama po sebi ne doprinosi boljoj interkulturnoj<br />

kompetenciji, što su rezultati studenata engleskog jezika i književnosti i potvrdili.<br />

Na kraju, rezultati ukazuju da interkulturna n<strong>as</strong>tava treba da se uključi u opšte visoko<br />

obrazov<strong>an</strong>je ako želimo da studenti pokažu interkulturnu kompetenciju u komunikaciji. Kako se<br />

kulturne vrednosti i značenja prenose jezičkim funkcijama, njihovo poznav<strong>an</strong>je uključuje i „<strong>an</strong>alizu<br />

vrednosti i artefakta na koje se odnose“ (Byram 1989: 43) i svest o tome da one ne mogu biti i isključivo<br />

lingvističke. Upravo tu interkulturni elementi (koji se uvode kroz interkulturne tehnike, od kojih je<br />

kulturni <strong>as</strong>imilator samo jedna) mogu da umnogome poboljšaju n<strong>as</strong>tavu str<strong>an</strong>ih jezika.<br />

Datum prihvat<strong>an</strong>ja teme od str<strong>an</strong>e<br />

NN veća:<br />

DP<br />

Datum odbr<strong>an</strong>e:<br />

DO<br />

Čl<strong>an</strong>ovi komisije:<br />

(ime i prezime / titula / zv<strong>an</strong>je /<br />

naziv org<strong>an</strong>izacije / status)<br />

KO<br />

03.12.2009.<br />

predsednik:<br />

čl<strong>an</strong>:<br />

čl<strong>an</strong>:

UNIVERSITY OF NOVI SAD<br />

FACULTY OF PHILOSOPHY<br />

KEY WORD DOCUMENTATION<br />

Accession number:<br />

ANO<br />

Identification number:<br />

INO<br />

Document type:<br />

DT<br />

Type <strong>of</strong> record:<br />

TR<br />

Contents code:<br />

CC<br />

Author:<br />

AU<br />

Mentor:<br />

MN<br />

Title:<br />

TI<br />

L<strong>an</strong>guage <strong>of</strong> text:<br />

LT<br />

L<strong>an</strong>guage <strong>of</strong> abstract:<br />

LA<br />

Country <strong>of</strong> publication:<br />

CP<br />

Locality <strong>of</strong> publication:<br />

LP<br />

Publication year:<br />

PY<br />

Publisher:<br />

PU<br />

Publication place:<br />

PP<br />

Monograph documentation<br />

Textual printed material<br />

Doctoral dissertation<br />

Nina Lazarević<br />

Gord<strong>an</strong>a Petričić, PhD, Assist<strong>an</strong>t Pr<strong>of</strong>essor, English<br />

Department, Faculty <strong>of</strong> Philosophy, University <strong>of</strong><br />

Novi Sad<br />

<strong>Intercultural</strong> <strong>competence</strong> <strong>as</strong> <strong>an</strong> <strong>as</strong>pect <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>communicative</strong> <strong>competence</strong> in <strong>the</strong> tertiary level<br />

English l<strong>an</strong>guage learners<br />

English<br />

Serbi<strong>an</strong>/ English<br />

Serbia<br />

Vojvodina<br />

2013<br />

Author’s reprint<br />

2 Zor<strong>an</strong>a Đinđića, Novi Sad

Physical description:<br />

PD<br />

6 chapters/ 301 pages / 19 figures / 45 tables /<br />

368 references / 11 appendices<br />

Scientific field<br />

SF<br />

Scientific discipline<br />

SD<br />

Subject, Key words<br />

SKW<br />

UC<br />

Holding data:<br />

HD<br />

Linguistics, Applied linguistics<br />

<strong>Intercultural</strong> <strong>competence</strong><br />

intercultural <strong>competence</strong>, intercultural awareness,<br />

intercultural sensitivity, culture <strong>as</strong>similator, critical<br />

incidents, TEFL<br />

Library <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> English Department, Faculty <strong>of</strong> Philosophy,<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Novi Sad<br />

Note:<br />

N<br />

Abstract:<br />

AB<br />

With <strong>the</strong> incre<strong>as</strong>ed interconnectedness <strong>an</strong>d mobility <strong>of</strong> people in a globalized world, <strong>the</strong> goals<br />

<strong>of</strong> foreign l<strong>an</strong>guage teaching (FLT) have undergone a ch<strong>an</strong>ge <strong>as</strong> well. <strong>Intercultural</strong> <strong>competence</strong> (ICC)<br />

h<strong>as</strong> become a proclaimed goal, adding to <strong>the</strong> already set goals <strong>of</strong> linguistic <strong>an</strong>d <strong>communicative</strong><br />

<strong>competence</strong>. However, <strong>the</strong> application <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ICC <strong>the</strong>ory in l<strong>an</strong>guage teaching h<strong>as</strong> not been extensive<br />

<strong>an</strong>d ‘little attention [h<strong>as</strong> been paid] to researching conceptualizing intercultural interaction’ (Spencer-<br />

Oatey, Fr<strong>an</strong>klin 2009: 63, 64). While <strong>the</strong>re is a ‘world-wide dem<strong>an</strong>d for <strong>the</strong> graduates to be “global<br />

citizens”, “world minded”’ (Paige, Goode 2009: 333), techniques applied in <strong>the</strong> cl<strong>as</strong>sroom do not seem<br />

to be conducive to <strong>the</strong> development <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> affective or behavioural component <strong>of</strong> ICC. Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore,<br />

teachers lack <strong>the</strong> tools <strong>an</strong>d might be hesit<strong>an</strong>t to include ICC in EFL cl<strong>as</strong>ses (Byram 1997), while <strong>the</strong><br />

research that should support teaching is mostly focused on study abroad programs with few studies<br />

investigating <strong>the</strong> ICC in <strong>the</strong> context <strong>of</strong> EFL (Korhonen 2004, Lázár 2007, Lundgren 2009, Pl<strong>an</strong>ken et al.<br />

2004). As for Serbia, <strong>the</strong> research in this area is quite recent, with only few studies that move beyond<br />

exploration <strong>of</strong> stereotypes in EFL (Cvetič<strong>an</strong>in, Paunović 2007, Lazarević, Savić 2009, Paunović 2011).<br />

The purpose <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> present study w<strong>as</strong> to gain <strong>an</strong> insight into <strong>the</strong> ICC <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> university students<br />

in Niš with a special focus on pedagogical implications for teaching practice at <strong>the</strong> university level.<br />

Secondly, <strong>the</strong> aim w<strong>as</strong> to explore possible factors that might influence ICC. In that respect, special<br />

attention w<strong>as</strong> given to <strong>the</strong> particip<strong>an</strong>ts’ ability to account for particular IC misunderst<strong>an</strong>dings in <strong>the</strong> form<br />

<strong>of</strong> critical incidents.<br />

For that purpose <strong>the</strong> study w<strong>as</strong> structured around <strong>the</strong> culture <strong>as</strong>similator <strong>as</strong> <strong>the</strong> most frequently<br />

used student-centered technique for both teaching <strong>an</strong>d <strong>as</strong>sessment. The <strong>as</strong>similator w<strong>as</strong> designed<br />

specifically for <strong>the</strong> study, employing two major approaches: empirical (interviews with English<br />

l<strong>an</strong>guage native speakers) <strong>an</strong>d <strong>the</strong>oretical (Bennett 1993, Cushner, Brislin 1996, Fowler 1995, Hall<br />

1966, H<strong>of</strong>stede 1984, Lambert <strong>an</strong>d Myers 1994, Trompenaars, Hampden-Turner 1997).<br />

Due to <strong>the</strong> inherent complexity <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ICC concept, <strong>the</strong> study w<strong>as</strong> both exploratory <strong>an</strong>d<br />

descriptive <strong>an</strong>d employed a mixed methods approach (Teddlie, T<strong>as</strong>hakkori 2009), with <strong>the</strong> aim <strong>of</strong><br />

providing a rich description <strong>of</strong> ICC. The data source in <strong>the</strong> qu<strong>an</strong>titative ph<strong>as</strong>e <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> study w<strong>as</strong> a<br />

st<strong>an</strong>dardized Global Perspective Inventory questionnaire distributed to <strong>the</strong> students from ten<br />

departments at <strong>the</strong> University <strong>of</strong> Niš (who also attended English l<strong>an</strong>guage courses) with <strong>the</strong> purpose <strong>of</strong><br />

ga<strong>the</strong>ring information <strong>of</strong> a wide <strong>an</strong>d diverse group. In <strong>the</strong> qualitative ph<strong>as</strong>e, <strong>the</strong> critical incidents from<br />

<strong>the</strong> culture <strong>as</strong>similator were used in <strong>the</strong> interviews with twelve students <strong>of</strong> different departments in order<br />

to ga<strong>the</strong>r information on <strong>the</strong> cognitive <strong>an</strong>d to a certain extent behavioural <strong>an</strong>d affective domains <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

particip<strong>an</strong>ts’ ICC. The data were <strong>an</strong>alysed by applying statistical tests in <strong>the</strong> qu<strong>an</strong>titative ph<strong>as</strong>e, while<br />

content <strong>an</strong>alysis <strong>an</strong>d coding were used in <strong>the</strong> qualitative ph<strong>as</strong>e <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> study.<br />

The findings <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> study suggested a disparity between <strong>the</strong> qu<strong>an</strong>titative <strong>an</strong>d qu<strong>an</strong>titative<br />

results. The former showed medium to high intercultural perspective, pointing to higher levels <strong>of</strong><br />

accept<strong>an</strong>ce <strong>of</strong> different cultural perspectives, self-confidence in IC encounters, <strong>an</strong>d sensitivity for<br />

pluralistic settings. On <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r h<strong>an</strong>d, <strong>the</strong> qualitative data provided almost diametrically different

esults, showing a considerable lack <strong>of</strong> intercultural <strong>competence</strong> <strong>as</strong> <strong>the</strong> particip<strong>an</strong>ts mainly relied on<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir own cultural frames to account for IC encounters, <strong>an</strong>d resorted to stereotyping, generalized<br />

descriptions <strong>an</strong>d dispositional attribution.<br />

While <strong>the</strong>re were slight differences in <strong>the</strong> qu<strong>an</strong>titative results across different departments,<br />

<strong>the</strong>se were not supported by <strong>the</strong> qualitative data, which ra<strong>the</strong>r showed low intercultural sensitivity,<br />

empathy <strong>an</strong>d <strong>the</strong> characteristics <strong>of</strong> Defense or Minimization stage (Bennett 1993) <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> particip<strong>an</strong>ts<br />

from almost all departments.<br />

Both <strong>the</strong> results <strong>of</strong> qualitative <strong>an</strong>d qu<strong>an</strong>titative stages <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> study showed that factors such <strong>as</strong><br />

stays or studies abroad, knowledge <strong>of</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r FL or gender did not have a signific<strong>an</strong>t influence on one’s<br />

intercultural <strong>competence</strong>. The findings also showed that intensive EFL instruction in itself did not<br />

contribute to ICC, <strong>as</strong> <strong>the</strong> results for <strong>the</strong> English l<strong>an</strong>guage students illustrated.<br />

Finally, <strong>the</strong> study shows that if students are to become interculturally competent learners <strong>an</strong>d<br />

communicators, IC instruction should be included in general education at <strong>the</strong> university level. Since <strong>the</strong><br />

functions <strong>of</strong> l<strong>an</strong>guage are used to tr<strong>an</strong>sfer cultural values <strong>an</strong>d me<strong>an</strong>ings, <strong>the</strong> knowledge <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se values<br />

<strong>an</strong>d me<strong>an</strong>ings entails ‘<strong>the</strong> <strong>an</strong>alysis <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> values <strong>an</strong>d artefacts to which <strong>the</strong>y refer’ (Byram 1989: 43) <strong>as</strong><br />

well <strong>as</strong> <strong>the</strong> awareness that <strong>the</strong>y c<strong>an</strong>not be only linguistic. This is where <strong>the</strong> intercultural component<br />

(introduced through IC techniques such <strong>as</strong> culture <strong>as</strong>similator) c<strong>an</strong> signific<strong>an</strong>tly improve EFL teaching.<br />

Accepted on Scientific<br />

Board on:<br />

AS<br />

Defended:<br />

DE<br />

Thesis Defend Board:<br />

DB<br />

3 rd Dec 2009<br />

president:<br />

member:<br />

member:

TABLE OF CONTENTS<br />

PAGE<br />

LIST OF TABLES<br />

iv<br />

LIST OF FIGURES<br />

vi<br />

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS<br />

vii<br />

ABSTRACT 1<br />

APSTRAKT 3<br />

CHAPTER I – INTRODUCTION 5<br />

1.1. Background <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> study 5<br />

1.2. Purpose <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> study 7<br />

1.3. Signific<strong>an</strong>ce <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> study 8<br />

1.4. Research questions 9<br />

1.5. Limitations <strong>an</strong>d delimitations <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> study 10<br />

1.6. Definitions <strong>of</strong> terms 11<br />

1.7. Org<strong>an</strong>ization <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> study 15<br />

CHAPTER II – LITERATURE REVIEW 17<br />

2.1. Culture 17<br />

2.1.1. Introduction 17<br />

2.1.2. Cultural awareness 27<br />

2.1.3. Cultural <strong>competence</strong> 28<br />

2.1.4. Culture <strong>an</strong>d l<strong>an</strong>guage teaching 29<br />

2.1.5. Models <strong>of</strong> culture 32<br />

2.1.6. Summary 37<br />

2.2. Communicative <strong>competence</strong> 38<br />

2.2.1. Introduction 38<br />

2.2.2. Communicative <strong>competence</strong> models 39<br />

2.2.3. Criticism <strong>of</strong> <strong>communicative</strong> <strong>competence</strong> 47<br />

2.2.4. Summary 48<br />

2.3. Development <strong>of</strong> intercultural <strong>competence</strong> 49<br />

2.3.1. Introduction 49<br />

2.3.2. The work <strong>of</strong> E.T. Hall 50<br />

2.3.3. Conceptualisation <strong>of</strong> ICC 52<br />

2.3.4. Criticism <strong>of</strong> ICC definitions 61<br />

2.3.5. The import<strong>an</strong>ce <strong>of</strong> ICC <strong>an</strong>d positive attitudes 62<br />

2.3.6. Criticism against <strong>the</strong> intercultural elements in <strong>the</strong> cl<strong>as</strong>sroom 64<br />

2.3.7. Foreign l<strong>an</strong>guage cl<strong>as</strong>sroom <strong>as</strong> <strong>the</strong> context for ICC learning 67<br />

2.3.7.1. <strong>Intercultural</strong> Competence <strong>an</strong>d English l<strong>an</strong>guage teaching 68<br />

2.3.8. Summary 74<br />

2.4. Models <strong>an</strong>d approaches to ICC 74<br />

2.4.1. Introduction 74<br />

2.4.2. Models <strong>of</strong> ICC 74<br />

2.4.3. Summary 105<br />

2.5. <strong>Intercultural</strong> <strong>competence</strong> in teaching/ learning context 105<br />

i

2.5.1. Introduction 105<br />

2.5.2. Techniques for intercultural learning 106<br />

2.5.3. Summary 113<br />

2.6. Research into learners’ ICC 114<br />

2.6.1. Introduction 114<br />

2.6.2. Previous research 114<br />

2.6.3. Culture <strong>as</strong>similator in previous research 125<br />

2.6.4. Summary 126<br />

CHAPTER III – METHODOLOGY 127<br />

3.1. Introduction 127<br />

3.2. Mixed methods approach 127<br />

3.3. The study 130<br />

3.3.1. Research questions 130<br />

3.4. Qu<strong>an</strong>titative study 131<br />

3.4.1. Introduction 131<br />

3.4.2. Global Perspective Inventory (GPI) 131<br />

3.4.2.1. Reliability <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> GPI 134<br />

3.4.3. Procedures 136<br />

3.4.3.1. Data collection 136<br />

3.4.3.2. Data <strong>an</strong>alysis 136<br />

3.5. Qualitative study 136<br />

3.5.1. Introduction 136<br />

3.5.2. Interviews 137<br />

3.5.3. Culture <strong>as</strong>similator 138<br />

3.5.3.1 Developing <strong>the</strong> culture <strong>as</strong>similator 139<br />

3.5.4. Syllabi <strong>of</strong> English l<strong>an</strong>guage courses 144<br />

3.5.5. Field notes 146<br />

3.5.6. Data trustworthiness 146<br />

3.5.7. Methods for validation <strong>an</strong>d trustworthiness – legitimation 146<br />

3.6. Particip<strong>an</strong>ts 148<br />

3.7. Researcher 151<br />

3.7.1. Hum<strong>an</strong> instrument 151<br />

3.7.2. Researcher role <strong>an</strong>d ethics 152<br />

3.8. Procedure 153<br />

3.8.1. Data collection 153<br />

3.8.2. Data <strong>an</strong>alysis 154<br />

3.9. Summary 155<br />

CHAPTER IV – RESULTS 157<br />

4.1. Introduction 157<br />

4.2. Questionnaire results 158<br />

4.3. Summary 174<br />

4.4. Interview results 174<br />

4.4.1. Coding categories 175<br />

ii

4.4.2. Attributions 179<br />

4.4.2.1. National identity – awareness <strong>of</strong> one’s own culture 179<br />

4.4.2.2. Establishing <strong>the</strong> first contact 181<br />

4.4.2.3. Socializing 185<br />

4.4.2.4. Student life 188<br />

4.4.2.5. At <strong>the</strong> work place 190<br />

4.4.2.6. Family life 193<br />

4.4.2.7. <strong>Intercultural</strong> awareness 194<br />

4.5. Summary 197<br />

CHAPTER V – DISCUSSION 199<br />

5.1. Introduction 199<br />

5.2. Attributions 203<br />

5.2.1. National identity – knowing who you are 204<br />

5.2.2. Establishing <strong>the</strong> first contact 208<br />

5.2.3. Socializing 211<br />

5.2.4. Student life 215<br />

5.2.5. At <strong>the</strong> work place 217<br />

5.2.6. Family life 219<br />

5.2.7. <strong>Intercultural</strong> awareness 221<br />

5.3. Concluding remarks 223<br />

5.4. Summary 227<br />

CHAPTER VI – CONCLUSION 229<br />

6.1. Conclusions 229<br />

6.2. Pedagogical implications 231<br />

6.3. Limitations 232<br />

6.4. Suggestions for fur<strong>the</strong>r research 234<br />

REFERENCES 237<br />

APPENDICES 265<br />

Appendix 1 Informed consent form for English l<strong>an</strong>guage native speakers 265<br />

Appendix 2 Informed consent form for students 266<br />

Appendix 3 Permission to use <strong>the</strong> GPI 267<br />

Appendix 4 The Global Perspective Inventory 269<br />

Appendix 5 The GPI subdomain items 271<br />

Appendix 6 Tr<strong>an</strong>scription conventions 273<br />

Appendix 7 Tr<strong>an</strong>script sample 274<br />

Appendix 8 Critical incidents used in interviews 279<br />

Appendix 9 Culture <strong>as</strong>similator – critical incidents <strong>an</strong>d rationales 282<br />

Appendix 10 Coding protocol, categories <strong>an</strong>d codes 296<br />

Appendix 11 Tables <strong>an</strong>d figures 297<br />

iii

LIST OF TABLES<br />

Table<br />

PAGE<br />

Table 3.1 The GPI questionnaire 135<br />

Table 3.2 Particip<strong>an</strong>ts in <strong>the</strong> qu<strong>an</strong>titative ph<strong>as</strong>e <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> study 149<br />

Table 3.3 Particip<strong>an</strong>ts in <strong>the</strong> qualitative ph<strong>as</strong>e <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> study 150<br />

Table 4.1 ICC domains <strong>an</strong>d <strong>the</strong> study stages 157<br />

Table 4.2 Years <strong>of</strong> learning English 158<br />

Table 4.3 Me<strong>an</strong> values <strong>of</strong> GPI subdomains 159<br />

Table 4.4 Me<strong>an</strong> values on subdomains for all departments 160<br />

Table 4.5 Test Statistics for Kruskal-Wallis Test for <strong>the</strong> grouping variable<br />

‘all departments’ 161<br />

Table 4.6 Fisher’s LSD test 161<br />

Table 4.7 One-Sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test 162<br />

Table 4.8 Test statistics for <strong>the</strong> grouping variable ‘English l<strong>an</strong>guage<br />

students’ 163<br />

Table 4.9 Subdomain me<strong>an</strong>s for English l<strong>an</strong>guage department students 164<br />

Table 4.10 Comparison <strong>of</strong> me<strong>an</strong> values for <strong>the</strong> 1 st <strong>an</strong>d 2 nd years 164<br />

Table 4.11 Comparison <strong>of</strong> male <strong>an</strong>d female particip<strong>an</strong>ts 165<br />

Table 4.12 Stays abroad 166<br />

Table 4.13 Knowledge <strong>of</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r FL 167<br />

Table 4.14 Correlations between questions 25, 29, 30, <strong>an</strong>d 32 168<br />

Table 4.15 Correlations between questions 8,13, <strong>an</strong>d 19 169<br />

Table 4.16 Correlations between questions 1 <strong>an</strong>d 12 169<br />

Table 4.17 Correlations between questions 29 <strong>an</strong>d 39 170<br />

Table 4.18 Correlations between questions 5 <strong>an</strong>d 38 171<br />

Table 4.19 Correlations <strong>of</strong> questions 28 <strong>an</strong>d 29 171<br />

Table 4.20 Correlations between questions 12, 25, <strong>an</strong>d 32 172<br />

Table 4.21 Correlations between questions 8 <strong>an</strong>d 32 173<br />

Table 4.22 Experience with FLL codes 175<br />

Table 4.23 ICC codes 176<br />

Table 4.24 Attitudes to IC contact codes 178<br />

Table 4.25 Values codes 178<br />

Table 4.26 Defining one’s own culture 179<br />

Table 4.27 Critical incident 1 codes 182<br />

Table 4.28 Critical incident 2 codes 183<br />

Table 4.29 Critical incident 3 codes 185<br />

Table 4.30 Critical incident 5 codes 186<br />

Table 4.31 Critical incident 18 codes 187<br />

Table 4.32 Critical incident 4 codes 188<br />

Table 4.33 Critical incident 9 codes 189<br />

Table 4.34 Critical incident 14 codes 190<br />

Table 4.35 Critical incident 6 codes 191<br />

iv

Table 4.36 Critical incident 7 codes 192<br />

Table 4.37 Critical incident 8 codes 193<br />

Table 4.38 Critical incident 17 codes 194<br />

Table A.1 ANOVA test 297<br />

Table A.2 M<strong>an</strong>n-Whitney U test for male <strong>an</strong>d female particip<strong>an</strong>ts 298<br />

Table A.3 Stays abroad <strong>an</strong>d sub-domain me<strong>an</strong>s 299<br />

Table A.4 Me<strong>an</strong>s for English l<strong>an</strong>guage students on all subdomains 299<br />

v

LIST OF FIGURES<br />

Figure<br />

PAGE<br />

Figure 2.1 Points <strong>of</strong> articulation between culture <strong>an</strong>d l<strong>an</strong>guage, adapted from<br />

Liddicoat et al. (2003) 31<br />

Figure 2.2 Cultural iceberg 33<br />

Figure 2.3 Onion layers, taken from Hosfstede (1997) 35<br />

Figure 2.4 Model <strong>of</strong> culture, taken from Trompenaars <strong>an</strong>d Hampden-Turner<br />

(1997) 36<br />

Figure 2.5 Chronological evolution <strong>of</strong> <strong>communicative</strong> <strong>competence</strong>, adapted<br />

from Celce-Murcia, M. (2007) 45<br />

Figure 2.6 Development <strong>of</strong> <strong>Intercultural</strong> sensitivity, taken from Bennett,<br />

Bennett, Allen (2003) 71<br />

Figure 2.7 Developmental Model <strong>of</strong> <strong>Intercultural</strong> Sensitivity, taken from<br />

Bennett (2004) 79<br />

Figure 2.8 The development <strong>of</strong> intercultural <strong>competence</strong>: a tr<strong>an</strong>sformational<br />

model, taken from Gl<strong>as</strong>er et al. (2007) 89<br />

Figure 2.9 AUM Theory, adapted from Gudykunst (2005) 91<br />

Figure 2.10 Worldviews convergence model, taken from F<strong>an</strong>tini (1995) 93<br />

Figure 2.11 Components <strong>of</strong> intercultural <strong>competence</strong>, taken from Sercu et al.<br />

(2005) 94<br />

Figure 2.12 Byram’s model <strong>of</strong> intercultural <strong>communicative</strong> <strong>competence</strong>,<br />

taken from Byram <strong>an</strong>d Zarate (1997a) 95<br />

Figure 2.13 <strong>Intercultural</strong> <strong>competence</strong> in foreign l<strong>an</strong>guage education, adapted<br />

from Kramer (2000) 101<br />

Figure 2.14 A contextual model <strong>of</strong> intercultural communication, taken from<br />

Neuliep (2005) 102<br />

Figure 4.1 Years <strong>of</strong> learning English <strong>an</strong>d Affect 167<br />

Figure A.1 Department comparison on sub-domain Knowledge 300<br />

Figure A.2 Department comparison on sub-domain Identity 300<br />

Figure A.3 Department comparison on sub-domain Responsibility 301<br />

Figure A.4 Department comparison on sub-domain Global Citizenship 301<br />

vi

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS<br />

CA Cultural awareness<br />

CC Cultural <strong>competence</strong><br />

CEFR Common Europe<strong>an</strong> Framework <strong>of</strong> Reference<br />

DMIS Developmental model <strong>of</strong> intercultural sensitivity<br />

EFL English <strong>as</strong> a foreign l<strong>an</strong>guage<br />

ELT English l<strong>an</strong>guage teaching<br />

FL Foreign l<strong>an</strong>guage<br />

FLT Foreign l<strong>an</strong>guage teaching<br />

IC <strong>Intercultural</strong><br />

ICC <strong>Intercultural</strong> <strong>competence</strong><br />

ICCC <strong>Intercultural</strong> <strong>communicative</strong> <strong>competence</strong><br />

L1 First l<strong>an</strong>guage<br />

L2 Second l<strong>an</strong>guage<br />

NNS Non-native speaker<br />

TEFL Teaching English <strong>as</strong> a foreign l<strong>an</strong>guage<br />

TESL Teaching English <strong>as</strong> a second l<strong>an</strong>guage<br />

vii

ABSTRACT<br />

With <strong>the</strong> incre<strong>as</strong>ed interconnectedness <strong>an</strong>d mobility <strong>of</strong> people in a globalized<br />

world, <strong>the</strong> goals <strong>of</strong> foreign l<strong>an</strong>guage teaching (FLT) have undergone a ch<strong>an</strong>ge <strong>as</strong> well.<br />

<strong>Intercultural</strong> <strong>competence</strong> (ICC) h<strong>as</strong> become a proclaimed goal, adding to <strong>the</strong> already set<br />

goals <strong>of</strong> linguistic <strong>an</strong>d <strong>communicative</strong> <strong>competence</strong>. However, <strong>the</strong> application <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ICC<br />

<strong>the</strong>ory in l<strong>an</strong>guage teaching h<strong>as</strong> not been extensive <strong>an</strong>d ‘little attention [h<strong>as</strong> been paid] to<br />

researching conceptualizing intercultural interaction’ (Spencer-Oatey, Fr<strong>an</strong>klin 2009: 63,<br />

64). While <strong>the</strong>re is a ‘world-wide dem<strong>an</strong>d for <strong>the</strong> graduates to be “global citizens”,<br />

“world minded”’ (Paige, Goode 2009: 333), techniques applied in <strong>the</strong> cl<strong>as</strong>sroom do not<br />

seem to be conducive to <strong>the</strong> development <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> affective or behavioural component <strong>of</strong><br />

ICC. Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore, teachers lack <strong>the</strong> tools <strong>an</strong>d might be hesit<strong>an</strong>t to include ICC in EFL<br />

cl<strong>as</strong>ses (Byram 1997), while <strong>the</strong> research that should support teaching is mostly focused<br />

on study abroad programs with few studies investigating <strong>the</strong> ICC in <strong>the</strong> context <strong>of</strong> EFL<br />

(Korhonen 2004; Lázár 2007; Lundgren 2009; Pl<strong>an</strong>ken et al. 2004). As for Serbia, <strong>the</strong><br />

research in this area is quite recent, with only few studies that move beyond exploration<br />

<strong>of</strong> stereotypes in EFL (Cvetič<strong>an</strong>in, Paunović 2007; Lazarević, Savić 2009; Paunović<br />

2011).<br />

The purpose <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> present study w<strong>as</strong> to gain <strong>an</strong> insight into <strong>the</strong> ICC <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

university students in Niš with a special focus on pedagogical implications for teaching<br />

practice at <strong>the</strong> university level. Secondly, <strong>the</strong> aim w<strong>as</strong> to explore possible factors that<br />

might influence ICC. In that respect, special attention w<strong>as</strong> given to <strong>the</strong> particip<strong>an</strong>ts’<br />

ability to account for particular IC misunderst<strong>an</strong>dings in <strong>the</strong> form <strong>of</strong> critical incidents.<br />

For that purpose <strong>the</strong> study w<strong>as</strong> structured around <strong>the</strong> culture <strong>as</strong>similator <strong>as</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

most frequently used student-centered technique for both teaching <strong>an</strong>d <strong>as</strong>sessment. The<br />

<strong>as</strong>similator w<strong>as</strong> designed specifically for <strong>the</strong> study, with two major approaches employed:<br />

empirical (interviews with English l<strong>an</strong>guage native speakers) <strong>an</strong>d <strong>the</strong>oretical (Bennett<br />

1993; Cushner, Brislin 1996; Fowler 1995; Hall 1966; H<strong>of</strong>stede 1984; Lambert, Myers<br />

1994; Trompenaars, Hampden-Turner 1997).<br />

Due to <strong>the</strong> inherent complexity <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ICC concept, <strong>the</strong> study w<strong>as</strong> both exploratory<br />

<strong>an</strong>d descriptive <strong>an</strong>d employed a mixed methods approach (Teddlie, T<strong>as</strong>hakkori 2009),<br />

with <strong>the</strong> aim <strong>of</strong> providing a rich description <strong>of</strong> ICC. The data source in <strong>the</strong> qu<strong>an</strong>titative<br />

ph<strong>as</strong>e <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> study w<strong>as</strong> a st<strong>an</strong>dardized Global Perspective Inventory questionnaire<br />

distributed to <strong>the</strong> students from ten departments at <strong>the</strong> University <strong>of</strong> Niš (who also<br />

1

attended English l<strong>an</strong>guage courses) with <strong>the</strong> purpose <strong>of</strong> ga<strong>the</strong>ring information <strong>of</strong> a wide<br />

<strong>an</strong>d diverse group. In <strong>the</strong> qualitative ph<strong>as</strong>e, <strong>the</strong> critical incidents from <strong>the</strong> culture<br />

<strong>as</strong>similator were used in <strong>the</strong> interviews with twelve students <strong>of</strong> different departments in<br />

order to ga<strong>the</strong>r information on <strong>the</strong> cognitive <strong>an</strong>d to a certain extent behavioural <strong>an</strong>d<br />

affective domains <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> particip<strong>an</strong>ts’ ICC. The data were <strong>an</strong>alysed by applying statistical<br />

tests in <strong>the</strong> qu<strong>an</strong>titative ph<strong>as</strong>e, while content <strong>an</strong>alysis <strong>an</strong>d coding were used in <strong>the</strong><br />

qualitative ph<strong>as</strong>e <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> study.<br />

The findings <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> study suggested a disparity between <strong>the</strong> qu<strong>an</strong>titative <strong>an</strong>d<br />

qu<strong>an</strong>titative results. The former showed medium to high intercultural perspective,<br />

pointing to higher levels <strong>of</strong> accept<strong>an</strong>ce <strong>of</strong> different cultural perspectives, self-confidence<br />

in IC encounters, <strong>an</strong>d sensitivity for pluralistic settings. On <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r h<strong>an</strong>d, <strong>the</strong> qualitative<br />

data provided almost diametrically different results, showing a considerable lack <strong>of</strong><br />

intercultural <strong>competence</strong> <strong>as</strong> <strong>the</strong> particip<strong>an</strong>ts mainly relied on <strong>the</strong>ir own cultural frames to<br />

account for IC encounters, <strong>an</strong>d resorted to stereotyping, generalized descriptions <strong>an</strong>d<br />

dispositional attribution.<br />

While <strong>the</strong>re were slight differences in <strong>the</strong> qu<strong>an</strong>titative results across different<br />

departments, <strong>the</strong>se were not supported by <strong>the</strong> qualitative data, which ra<strong>the</strong>r showed low<br />

intercultural sensitivity, empathy <strong>an</strong>d <strong>the</strong> characteristics <strong>of</strong> Defense or Minimization stage<br />

(Bennett 1993) <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> particip<strong>an</strong>ts from almost all departments.<br />

Both <strong>the</strong> results <strong>of</strong> qualitative <strong>an</strong>d qu<strong>an</strong>titative stages <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> study showed that<br />

factors such <strong>as</strong> study abroad, knowledge <strong>of</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r FL or gender did not have a signific<strong>an</strong>t<br />

influence on one’s intercultural <strong>competence</strong>. The findings also showed that intensive EFL<br />

instruction in itself did not contribute to ICC, <strong>as</strong> <strong>the</strong> results for <strong>the</strong> English l<strong>an</strong>guage<br />

students illustrated.<br />

Finally, <strong>the</strong> study shows that if students are to become interculturally competent<br />

learners <strong>an</strong>d communicators, IC instruction should be included in general education at <strong>the</strong><br />

university level. Since <strong>the</strong> functions <strong>of</strong> l<strong>an</strong>guage are used to tr<strong>an</strong>sfer cultural values <strong>an</strong>d<br />

me<strong>an</strong>ings, <strong>the</strong> knowledge <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se values <strong>an</strong>d me<strong>an</strong>ings entails ‘<strong>the</strong> <strong>an</strong>alysis <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> values<br />

<strong>an</strong>d artefacts to which <strong>the</strong>y refer’ (Byram 1989: 43) <strong>as</strong> well <strong>as</strong> <strong>the</strong> awareness that <strong>the</strong>y<br />

c<strong>an</strong>not be only linguistic. This is where <strong>the</strong> intercultural component (introduced through<br />

IC techniques such <strong>as</strong> culture <strong>as</strong>similator) c<strong>an</strong> signific<strong>an</strong>tly improve EFL teaching.<br />

Key words: intercultural <strong>competence</strong>, intercultural sensitivity, EFL teaching,<br />

culture <strong>as</strong>similator, critical incidents<br />

2

APSTRAKT<br />

Ciljevi n<strong>as</strong>tave engleskog jezika su se promenili kako su međusobna povez<strong>an</strong>ost i<br />

moblinost ljudi koje karakterišu moderni svet r<strong>as</strong>le. Interkulturna kompetencija se<br />

pojavljuje kao još jed<strong>an</strong> uz već postavljene ciljeve lingvističke i komunikativne<br />

kompetencije u n<strong>as</strong>tavi str<strong>an</strong>ih jezika. Ipak, primena teorije interkulturne kompentencije u<br />

n<strong>as</strong>tavi str<strong>an</strong>ih jezika nije z<strong>as</strong>tupljena u velikom obimu i „malo pažnje pridaje se<br />

istraživ<strong>an</strong>ju konceptualizacije interkulturne interakcije“ (Spencer-Oatey, Fr<strong>an</strong>klin 2009:<br />

63,64). Iako postoji „potreba na svetskom nivou da diplomir<strong>an</strong>i studenti budu „građ<strong>an</strong>i<br />

sveta“, i da budu „svesni sveta““ (Paige, Goode 2009: 333), tehnike koje se primenjuju u<br />

n<strong>as</strong>tavi nisu najpogodnije za razvij<strong>an</strong>je afektivne i bihevioralne komponente interkulturne<br />

kompetencije. Štaviše, n<strong>as</strong>tavnici nemaju potrebnu teorijsku i praktičnu osnovu i nisu<br />

uvek spremni da uključe interkulturnu kompetenciju u n<strong>as</strong>tavu engleskog jezika (Byram<br />

1997), a istraživ<strong>an</strong>ja koja bi trebalo da pomognu n<strong>as</strong>tavu u velikoj meri usmerena su na<br />

programe studir<strong>an</strong>ja u inostr<strong>an</strong>stvu, i tek m<strong>an</strong>ji broj studija bavi se interkulturnom<br />

kompetencijom u kontekstu engleskog kao str<strong>an</strong>og jezika (Pl<strong>an</strong>ken et al. 2004; Korhonen<br />

2004; Lundgren 2009; Lázár 2007). U Srbiji je polje interkulturne kompetencije relativno<br />

novo i mali je broj istraživ<strong>an</strong>ja koja idu dalje od problema stereotipa (Cvetič<strong>an</strong>in,<br />

Paunović 2007; Lazarević, Savić 2009; Paunović 2011).<br />

Disertacija je imala za cilj da da uvid u interkulturnu kompetenciju studenata<br />

Univerziteta u Nišu, sa posebnim osvrtom na pedagoške implikacije za n<strong>as</strong>tavnu praksu<br />

na univerzitetskom nivou. Drugo, cilj istraživ<strong>an</strong>ja bio je da se istraže i faktori koji mogu<br />

imati uticaja na nju. Stoga je posebna pažnja data sposobnosti ispit<strong>an</strong>ika da obj<strong>as</strong>ne<br />

određene interkulturne nesporazume.<br />

U tu svrhu u istraživ<strong>an</strong>ju je korišćen kulturni <strong>as</strong>imilator kao najčešća tehnika koja<br />

u prvi pl<strong>an</strong> stavlja stavove studenata, a koristi se i za n<strong>as</strong>tavu i za ocenjiv<strong>an</strong>je. Asimilator<br />

koji je istraživač napravio upravo za ovo istraživ<strong>an</strong>je z<strong>as</strong>nov<strong>an</strong> je na dva pristupa:<br />

empirijskom (intervjui sa izvornim govornicima engleskog jezika) i teoretskom (Bennett<br />

1993; Cushner, Brislin 1996; Fowler 1995; Hall 1966; H<strong>of</strong>stede 1984; Lambert, Myers<br />

1994; Trompenaars, Hampden-Turner 1997).<br />

Kako je interkulturna kompetencija suštinski kompleks<strong>an</strong> koncept, istraživ<strong>an</strong>je je<br />

bilo ne samo deskriptivno već i eksploratorno te koristilo kombinov<strong>an</strong>u metodu (Teddlie,<br />

T<strong>as</strong>hakkori 2009), kako bi pružilo bolje razumev<strong>an</strong>je interkulturne kompetencije. U svrhu<br />

prikuplj<strong>an</strong>ja podataka, iskorišćen je st<strong>an</strong>dardizov<strong>an</strong>i upitnik koji se koristi za ispitiv<strong>an</strong>je<br />

3

interkulturne osetljivosti, a koji su popunili studenti sa deset departm<strong>an</strong>a (koji su takođe<br />

pohađali i kurs engleskog jezika) kako bi se dobile informacije o raznolikoj i velikoj<br />

grupi. U kvalitativnoj fazi korišćeni su kritički incidenti iz kulturnog <strong>as</strong>imilatora u<br />

intervjuima sa dv<strong>an</strong>aest studenata sa različitih departm<strong>an</strong>a kako bi se dobili podaci o<br />

kognitivnom i donekle bihevioralnom i afektivnom domenu interkulturne kompetencije<br />

ispit<strong>an</strong>ika. Za <strong>an</strong>alizu podataka korišćeni su statistički testovi u kv<strong>an</strong>titativnoj, a <strong>an</strong>aliza<br />

sadržaja i kodir<strong>an</strong>je u kvalitativnoj fazi.<br />

Rezultati pokazuju neslag<strong>an</strong>je između kv<strong>an</strong>titativnih i kvalitativnih rezultata. Prvi<br />

pokazuju relativno visok stepen interkulturne perspektive, što ukazuje na viši nivo<br />

prihvat<strong>an</strong>ja kulturno različitih perspektiva, sigurnost u interkulturnim susretima kao i<br />

senzitivnost prema kontekstu koji je kulturno raznolik. S druge str<strong>an</strong>e, kvalitativni podaci<br />

daju skoro dijametralno suprotne rezultate, pokazujući određen nedostatak interkulturne<br />

kompetencije jer su ispit<strong>an</strong>ici uglavnom koristili kulturne okvire sopstvene kulture kako<br />

bi obj<strong>as</strong>nili interkulturne susrete i pribegavali stereotipima, generalizacijama i<br />

atribucijama z<strong>as</strong>nov<strong>an</strong>im na ličnim karakterisitkama.<br />

Mada je bilo m<strong>an</strong>jih razlika u kv<strong>an</strong>titativnim rezultatima za različite departm<strong>an</strong>e,<br />

kvalitativni podaci ih nisu pokazali, već su kod ispitatnika ukazali na nisku interkulturnu<br />

senzitivnost i empatiju kao i karakteristike faza Odbr<strong>an</strong>a i Minimalizacija (Bennett 1993)<br />

kod studenata skoro svih departm<strong>an</strong>a.<br />

I kvalitativni i kv<strong>an</strong>titativni rezultati pokazuju da faktori kao što su boravak u<br />

inostr<strong>an</strong>stvu, poznav<strong>an</strong>je drugih str<strong>an</strong>ih jezika i pol nemaju značaj<strong>an</strong> uticaj na<br />

interkulturnu kompetenciju. Takođe se pokazalo da intenzivna n<strong>as</strong>tava engleskog jezika<br />

sama po sebi ne doprinosi boljoj interkulturnoj kompetenciji, što su rezultati studenata<br />

engleskog jezika i književnosti i potvrdili.<br />

Na kraju, rezultati ukazuju da interkulturna n<strong>as</strong>tava treba da se uključi u opšte<br />

visoko obrazov<strong>an</strong>je ako želimo da studenti pokažu interkulturnu kompetenciju u<br />

komunikaciji. Kako se kulturne vrednosti i značenja prenose jezičkim funkcijama,<br />

njihovo poznav<strong>an</strong>je uključuje i „<strong>an</strong>alizu vrednosti i artefakta na koje se odnose“ (Byram<br />

1989: 43) i svest o tome da one ne mogu biti i isključivo lingvističke. Upravo tu<br />

interkulturni elementi (koji se uvode kroz interkulturne tehnike, od kojih je kulturni<br />

<strong>as</strong>imilator samo jedna) mogu umnogome da poboljšaju n<strong>as</strong>tavu str<strong>an</strong>ih jezika.<br />

Ključne reči: interkulturna kompetencija, interkulturna senzitivnost, n<strong>as</strong>tava<br />

engleskog jezika, kulturni <strong>as</strong>imilator, kritički incidenti<br />

4

CHAPTER I – INTRODUCTION<br />

1.1. Background <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> study<br />

<strong>Intercultural</strong> <strong>competence</strong> (ICC) h<strong>as</strong> been a debated <strong>an</strong>d researched issue for a few<br />

decades now, however, its inclusion in English l<strong>an</strong>guage cl<strong>as</strong>ses h<strong>as</strong> not been that<br />

successful (Kramsch 1993, 2003). Culture used to be a useful ‘<strong>as</strong>ide’ in l<strong>an</strong>guage cl<strong>as</strong>ses,<br />

<strong>the</strong>n, <strong>the</strong> view h<strong>as</strong> ch<strong>an</strong>ged <strong>an</strong>d culture w<strong>as</strong> <strong>the</strong>n seen <strong>as</strong> a ‘fifth dimension’ (Damen<br />

1987), while in more recent years m<strong>an</strong>y authors agree that l<strong>an</strong>guage teaching is culture<br />

bound (Valdes 1986; Byram 1989; Seelye 1993; B<strong>as</strong>snett 2003). However, <strong>the</strong><br />

application <strong>of</strong> <strong>an</strong>y <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ICC <strong>the</strong>ories is still not seen in l<strong>an</strong>guage teaching, <strong>an</strong>d <strong>the</strong>re<br />

seems to be ‘relatively little attention [paid] to researching conceptualizing intercultural<br />

interaction’ (Spencer-Oatey, Fr<strong>an</strong>klin 2009: 63, 64). The re<strong>as</strong>on for this might be what<br />

Stern points to, that ‘<strong>the</strong> cultural component h<strong>as</strong> remained difficult to accommodate in<br />

practice’ (Stern 1992: 206), <strong>an</strong>d o<strong>the</strong>r researchers agree with that statement, listing a<br />

number <strong>of</strong> re<strong>as</strong>ons for <strong>the</strong> current state <strong>of</strong> affairs. The research h<strong>as</strong> shown that techniques<br />

applied in <strong>the</strong> cl<strong>as</strong>sroom are not conducive to <strong>the</strong> development <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> affective or<br />

behavioural component in students. On <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r h<strong>an</strong>d, ‘<strong>the</strong>re is a world-wide dem<strong>an</strong>d for<br />

<strong>the</strong> graduates to be ‘global citizens,’ ‘world minded,’ ‘globally engaged,’ […] 1 <strong>an</strong>d <strong>the</strong>re<br />

h<strong>as</strong> been <strong>an</strong> incre<strong>as</strong>e in programs that provide intercultural learning opportunities (Paige,<br />

Goode 2009: 333).<br />

As Chen <strong>an</strong>d Starosta (1996) point out, <strong>the</strong>re are a number <strong>of</strong> <strong>as</strong>pects due to which<br />

<strong>the</strong> world h<strong>as</strong> become a global society with ICC <strong>as</strong> a critical ability needed to face all <strong>the</strong><br />

challenges <strong>of</strong> that world. To name but a few <strong>as</strong>pects, <strong>the</strong>se are <strong>the</strong> development <strong>of</strong><br />

communication <strong>an</strong>d tr<strong>an</strong>sportation, <strong>the</strong> globalization <strong>of</strong> world economy <strong>an</strong>d<br />

multinationals, migration <strong>of</strong> population among nations, diversification <strong>of</strong> workforce, <strong>as</strong><br />

well <strong>as</strong> regional alli<strong>an</strong>ces. The new characteristics <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> modern world require greater<br />

underst<strong>an</strong>ding, toler<strong>an</strong>ce <strong>an</strong>d sensitivity, but also greater competency <strong>of</strong> people from<br />

different cultures.<br />

The global market <strong>an</strong>d interconnected world dem<strong>an</strong>d different <strong>an</strong>d widened skills<br />

when it comes to interaction <strong>an</strong>d communication, which renders l<strong>an</strong>guage pr<strong>of</strong>iciency <strong>as</strong><br />

1 Square brackets are used to indicate several ch<strong>an</strong>ges in <strong>the</strong> original quotation text: missing text, ch<strong>an</strong>ged<br />

capitalization, ch<strong>an</strong>ged inflection to fit <strong>the</strong> context or grammatical accuracy <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> sentence.<br />

5

not sufficient. M<strong>an</strong>y people today live in ‘ephemeral social formations’ (Spencer-Oatey,<br />

Kotth<strong>of</strong>f 2007: 1), <strong>the</strong>y are simult<strong>an</strong>eously part <strong>of</strong> several cultures <strong>an</strong>d one would be<br />

tempted to <strong>as</strong>sume that people do not belong to separate local cultures <strong>as</strong> <strong>the</strong>re are<br />

international influences from <strong>the</strong> m<strong>as</strong>s media. However, this does not me<strong>an</strong> that<br />

communities will become globalized. It is precisely in contact with o<strong>the</strong>rs that a need for<br />

distinction arises, <strong>an</strong>d a particular group membership c<strong>an</strong> be created <strong>as</strong> a relev<strong>an</strong>t feature<br />

for differences in contacts (Barth 1969). It is <strong>the</strong>n that intercultural <strong>competence</strong> enters <strong>the</strong><br />

scene <strong>an</strong>d helps people navigate intercultural encounters successfully.<br />

To be more effective in a ch<strong>an</strong>ging world ‘a conscious decision concerning our<br />

b<strong>as</strong>ic attitudes towards ourselves <strong>an</strong>d toward our relationship to o<strong>the</strong>rs <strong>an</strong>d <strong>the</strong> world at<br />

large’ (Gudykunst, Kim 1984: 224) should be made. What is needed is repositioning<br />

oneself in terms <strong>of</strong> our daily strategies <strong>an</strong>d lessened ethnocentrism. However, ch<strong>an</strong>ging<br />

one’s views <strong>an</strong>d habits, especially if one grows up in a monocultural milieu is difficult<br />

<strong>an</strong>d <strong>the</strong>re usually lacks ‘a clear underst<strong>an</strong>ding <strong>of</strong> [<strong>the</strong> worlds’] fundamental dynamics <strong>an</strong>d<br />

a clear sense <strong>of</strong> direction for ch<strong>an</strong>ge’ (Gudykunst, Kim 1984: 224). That is <strong>the</strong> re<strong>as</strong>on<br />

why intercultural <strong>competence</strong> <strong>an</strong>d communication should be learned.<br />

Though <strong>the</strong> need for intercultural (IC) training h<strong>as</strong> been recognized, <strong>the</strong> response<br />

from <strong>the</strong> field <strong>of</strong> practice in Serbia h<strong>as</strong> still to come. The new org<strong>an</strong>ization <strong>of</strong> university<br />

studies after <strong>the</strong> Bologna reform could be a timely ch<strong>an</strong>ge if <strong>the</strong> courses with IC content<br />

are to be introduced. That would be a useful continuation to EFL high school instruction<br />

that h<strong>as</strong> <strong>as</strong> one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> teaching goals culture learning <strong>an</strong>d development <strong>of</strong> empathy for<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r cultures, if still not completely implemented (Lazarević 2007).<br />

Students continuing education at <strong>the</strong> tertiary level should be ready for <strong>the</strong> open<br />

market, multiethnic <strong>an</strong>d multinational working context. Therefore, Europe<strong>an</strong> universities<br />

have begun to introduce courses in international <strong>an</strong>d intercultural issues, ‘regardless <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> disciplinary focus <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> academic program’ (Otten 2003: 18), which is still not <strong>the</strong><br />

c<strong>as</strong>e in Serbia. Also, apart from a few courses at <strong>the</strong> Department <strong>of</strong> Journalism <strong>an</strong>d<br />

Sociology, much <strong>of</strong> ‘IC load’ seems to be left for foreign l<strong>an</strong>guage courses. While IC<br />

teaching c<strong>an</strong>not be done only through FL courses, <strong>the</strong>y are surely <strong>an</strong> import<strong>an</strong>t element in<br />

ICC teaching.<br />

English l<strong>an</strong>guage teaching at <strong>the</strong> tertiary level <strong>of</strong> education does not employ a<br />

unified curriculum, <strong>an</strong>d at various universities most <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> courses in English are designed<br />

<strong>as</strong> English for specific purposes. While <strong>the</strong> teaching follows different educational<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>iles, thus giving a sound pr<strong>of</strong>ession-related l<strong>an</strong>guage b<strong>as</strong>e, it is questionable whe<strong>the</strong>r<br />

6

enough attention is given to intercultural learning <strong>an</strong>d <strong>the</strong> reality that would await<br />

graduated students once <strong>the</strong>y enter <strong>the</strong> global pr<strong>of</strong>essional world.<br />

Finally, since <strong>the</strong> researcher included ICC <strong>of</strong> high school students in her MA<br />

<strong>the</strong>sis, though <strong>as</strong> a minor segment <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> study, it w<strong>as</strong> logical to continue to explore that<br />

<strong>as</strong>pect <strong>of</strong> TEFL <strong>an</strong>d <strong>the</strong> tertiary education w<strong>as</strong> <strong>the</strong>refore <strong>the</strong> next step. Not forgetting that<br />

our students face realistic prospects <strong>of</strong> interacting with o<strong>the</strong>r students <strong>an</strong>d pr<strong>of</strong>essionals<br />

not only from <strong>the</strong> surrounding countries, but also from Europe <strong>an</strong>d <strong>the</strong> world, <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

linguistic <strong>competence</strong> should be on a par with <strong>the</strong> IC one. <strong>Intercultural</strong> instruction c<strong>an</strong><br />

create ‘more interculturally trained citizens who would add on knowledge <strong>an</strong>d coping<br />

techniques, <strong>an</strong>d consequently, enh<strong>an</strong>ce pr<strong>of</strong>essional skills’ (Kealey, Pro<strong>the</strong>roe 1996: 147).<br />

1.2. Purpose <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> study<br />

The aim <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> present study w<strong>as</strong> to get <strong>an</strong> insight into <strong>the</strong> existing intercultural<br />

<strong>competence</strong> <strong>of</strong> university students <strong>of</strong> hum<strong>an</strong>ities <strong>an</strong>d social studies at <strong>the</strong> University <strong>of</strong><br />

Niš. Also, <strong>the</strong> present study explored <strong>the</strong> views <strong>of</strong> a smaller sample <strong>of</strong> students, <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

opinions <strong>as</strong> well <strong>as</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir IC skills when presented with a potential misunderst<strong>an</strong>ding in <strong>an</strong><br />

ICC encounter in order to closer examine <strong>the</strong>ir intercultural <strong>competence</strong>.<br />

In order to better explore students’ ICC, <strong>the</strong> study is both descriptive <strong>an</strong>d<br />

exploratory (Patton 1990). It is descriptive in <strong>the</strong> sense that it tapped into <strong>the</strong> area which<br />

h<strong>as</strong> not been researched extensively in Serbia. There h<strong>as</strong> been a small number <strong>of</strong> studies<br />

dealing with culture <strong>an</strong>d attitudes – <strong>the</strong> effect <strong>of</strong> accents <strong>an</strong>d l<strong>an</strong>guage varieties on<br />

students’ attitudes (Cvetič<strong>an</strong>in, Paunović 2007), or stereotypes that students have<br />

(Ignjačević 1998), culture <strong>competence</strong> <strong>of</strong> high school learners (Lazarević 2007),<br />

knowledge <strong>of</strong> pre-service teachers <strong>of</strong> culture-teaching techniques (Lazarević, Savić<br />

2009). However, <strong>the</strong>re have been very few studies focused on intercultural <strong>competence</strong>,<br />

for example, one study focused on <strong>the</strong> cultural elements <strong>an</strong>d <strong>communicative</strong> contexts preservice<br />

English l<strong>an</strong>guage teachers found relev<strong>an</strong>t in <strong>the</strong> field <strong>of</strong> ICC, exploring students’<br />

cultural sensitivity, <strong>the</strong>ir attitudes towards cultural differences, <strong>an</strong>d <strong>the</strong>ir critical cultural<br />

awareness (Paunović 2011). Therefore, <strong>the</strong> present study provided data on a relatively<br />

large sample <strong>of</strong> first year students with both <strong>the</strong>ir experience with EFL <strong>an</strong>d views about<br />

ICC.<br />

The study is exploratory since it explores a relatively recent concept in <strong>the</strong> local<br />

setting. Namely, it tries to show what elements, attitudes <strong>an</strong>d opinions influence <strong>an</strong><br />

individual’s intercultural sensitivity <strong>an</strong>d <strong>competence</strong>. Such gained experience with <strong>the</strong><br />

7

concept <strong>of</strong> ICC in <strong>the</strong> university setting may be a springboard for fur<strong>the</strong>r research b<strong>as</strong>ed<br />

on intercultural <strong>competence</strong> <strong>an</strong>d communication, <strong>an</strong>d help define fur<strong>the</strong>r <strong>an</strong>d more<br />

definite investigation. In order to achieve this, <strong>the</strong> approach employed w<strong>as</strong> a mixed<br />

methods approach (Teddlie, T<strong>as</strong>hakkori 2009), which presents ‘<strong>an</strong> integration <strong>of</strong><br />

statistical <strong>an</strong>d <strong>the</strong>matic data <strong>an</strong>alytic techniques, plus o<strong>the</strong>r strategies unique to mixed<br />

method (e.g. data conversion or tr<strong>an</strong>sformation)’ (Teddlie, T<strong>as</strong>hakkori 2009: 8). Such<br />

research c<strong>an</strong> address a number <strong>of</strong> questions which are exploratory in nature, might give<br />

stronger inferences, <strong>an</strong>d <strong>of</strong>fer a wider r<strong>an</strong>ge <strong>of</strong> views (Teddlie, T<strong>as</strong>hakkori 2009).<br />

The study tried to establish whe<strong>the</strong>r students knew how to identify possible<br />

troublesome are<strong>as</strong> (fixed points, Jensen 2006) through a culture <strong>as</strong>similator. A number <strong>of</strong><br />

critical incidents comprising <strong>the</strong> culture <strong>as</strong>similator were devised, specially focused on<br />

<strong>the</strong> Serbi<strong>an</strong> <strong>an</strong>d Anglophone cultures in contact. These might be used in cl<strong>as</strong>s to practice<br />

both l<strong>an</strong>guage <strong>an</strong>d intercultural <strong>competence</strong>. In that respect <strong>the</strong> study h<strong>as</strong> a concrete<br />

outcome – a teaching (<strong>an</strong>d potentially <strong>as</strong>sessment) tool, which c<strong>an</strong> be fur<strong>the</strong>r honed <strong>an</strong>d<br />

tested. Hopefully, this may help English l<strong>an</strong>guage teachers at a university <strong>an</strong>d even high<br />

school level in terms <strong>of</strong> including culture <strong>as</strong>similators into <strong>the</strong>ir teaching practices.<br />

Finally, <strong>the</strong> aim for <strong>the</strong> study w<strong>as</strong> not to provide <strong>an</strong>y a particular level <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

particip<strong>an</strong>ts’ ICC, <strong>as</strong> it w<strong>as</strong> focused on a ‘section’ <strong>of</strong> foreign l<strong>an</strong>guage learning. Ra<strong>the</strong>r, it<br />

might serve <strong>as</strong> a starting point for a wider study that would engage scholars from different<br />

fields <strong>of</strong> Serbi<strong>an</strong> l<strong>an</strong>guage, English l<strong>an</strong>guage, sociology, pedagogy, psychology in a joint<br />

venture to provide training in ICC.<br />

1.3. Signific<strong>an</strong>ce <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> study<br />

There are several <strong>as</strong>pects that <strong>the</strong> study addressed, thus making it signific<strong>an</strong>t both<br />

for <strong>the</strong> underst<strong>an</strong>ding <strong>of</strong> ICC in <strong>the</strong> Serbi<strong>an</strong> context <strong>an</strong>d <strong>the</strong> applied linguistics, especially<br />

for <strong>the</strong> current TEFL practices at <strong>the</strong> tertiary level. While this is fur<strong>the</strong>r commented on in<br />

<strong>the</strong> concluding chapter, only several signific<strong>an</strong>t <strong>as</strong>pects are presented here.<br />

Firstly, <strong>the</strong> field <strong>of</strong> ICC is relatively new, despite its having been developed over<br />

<strong>the</strong> course <strong>of</strong> 60 to 70 years, <strong>the</strong>re have not been m<strong>an</strong>y studies conducted to explore <strong>the</strong>se<br />

particular issues in Serbia. While <strong>the</strong>re were studies that were concerned with <strong>the</strong><br />

students’ views on EFL or explored students’ stereotypes about a FL culture <strong>the</strong>re have<br />

not been studies aimed solely at students’ ICC.<br />

Secondly, culture does not play a signific<strong>an</strong>t part in ELT, <strong>an</strong>d <strong>the</strong> same goes for<br />

IC elements. The research conducted so far (Kramsch 2003, Lambert 1999, Sercu 2005)<br />

8

shows that in spite <strong>of</strong> <strong>an</strong> allegedly widely used <strong>communicative</strong> method, techniques which<br />

are used for teaching culture are still b<strong>as</strong>ed on a teacher-centered cl<strong>as</strong>sroom, thus not<br />

allowing learners to fully develop <strong>the</strong>ir ICC. The study might be <strong>an</strong> impetus for a more<br />

interculturally-oriented foreign l<strong>an</strong>guage cl<strong>as</strong>sroom, providing data, teaching <strong>an</strong>d<br />

<strong>as</strong>sessment formats.<br />

Thirdly, <strong>the</strong> present study provided <strong>an</strong> insight into <strong>the</strong> ‘rationalization’ <strong>of</strong><br />

students’ attitudes <strong>an</strong>d opinions. The data showed how particular IC ‘problems’ are<br />

understood <strong>an</strong>d would be responded to, <strong>the</strong>refore providing a starting point for fur<strong>the</strong>r<br />

research.<br />

Fourthly, <strong>the</strong> research had in its center <strong>the</strong> culture <strong>as</strong>similator <strong>as</strong> <strong>the</strong> most<br />

frequently used technique for both teaching <strong>an</strong>d <strong>as</strong>sessment. It is a student-centered<br />

technique, <strong>an</strong>d requires <strong>an</strong> <strong>an</strong>alysis <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> elements <strong>of</strong> a foreign culture to be successfully<br />

solved. The culture-specific <strong>as</strong>similator w<strong>as</strong> used both to probe for <strong>the</strong> ICC <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

particip<strong>an</strong>ts, but could be used <strong>as</strong> a teaching tool in its own right.<br />

Fifthly, <strong>the</strong> study uses a research tool which c<strong>an</strong> e<strong>as</strong>ily be adapted <strong>as</strong> both<br />

teaching <strong>an</strong>d <strong>as</strong>sessment tool. The culture <strong>as</strong>similator that w<strong>as</strong> designed to specifically fit<br />

<strong>the</strong> purposes <strong>of</strong> <strong>an</strong> English l<strong>an</strong>guage learner c<strong>an</strong> be applied in different teaching contexts<br />

or serve <strong>as</strong> <strong>an</strong> initial help for students in <strong>the</strong>ir individual work.<br />

Sixthly, <strong>the</strong> study is signific<strong>an</strong>t <strong>as</strong> it employed a mixed methods approach which is<br />

still not usual for <strong>the</strong> research done in <strong>the</strong> fields <strong>of</strong> EFL or ICC in Serbia. It provided<br />

qu<strong>an</strong>titative data for a larger sample <strong>of</strong> students <strong>an</strong>d <strong>the</strong>n compared <strong>an</strong>d contr<strong>as</strong>ted it with<br />

qualitative data for a smaller sample. This paradigm might give <strong>an</strong> incentive to Serbi<strong>an</strong><br />

researchers to use it more extensively.<br />

Finally, <strong>the</strong> present study might be <strong>an</strong> encouragement for o<strong>the</strong>r researchers to<br />

apply some o<strong>the</strong>r methods <strong>an</strong>d methodologies in order to explore ICC in a more detailed<br />

m<strong>an</strong>ner <strong>an</strong>d to engage in <strong>an</strong> ongoing discussion on <strong>the</strong> <strong>as</strong>sessment <strong>of</strong> ICC.<br />

1.4. Research questions<br />

The research questions that were set for this study had been arrived at after several<br />

years <strong>of</strong> work on culture <strong>an</strong>d intercultural <strong>competence</strong>. During <strong>the</strong> work on <strong>the</strong> MA<br />

dissertation, some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> questions connected to <strong>the</strong> field <strong>of</strong> ICC emerged <strong>an</strong>d <strong>the</strong><br />

researcher felt it w<strong>as</strong> import<strong>an</strong>t to explore <strong>the</strong>m in greater detail. The results <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> MA<br />

<strong>the</strong>sis showed that high school students received little cultural training in <strong>the</strong>ir English<br />

9

l<strong>an</strong>guage cl<strong>as</strong>ses, <strong>an</strong>d that <strong>the</strong> knowledge <strong>the</strong>y did possess came from sources outside <strong>the</strong><br />

cl<strong>as</strong>sroom. This only led to questions whe<strong>the</strong>r this w<strong>as</strong> <strong>the</strong> c<strong>as</strong>e in higher education, more<br />

precisely, whe<strong>the</strong>r university students received intercultural training alongside <strong>the</strong>ir EFL<br />

or ESP cl<strong>as</strong>ses <strong>an</strong>d how interculturally competent <strong>the</strong>y were.<br />

To give a more detailed <strong>an</strong>swer <strong>the</strong>re are four main research questions:<br />

RQ1 Are <strong>the</strong> Niš University students interculturally competent?<br />

RQ2 Do certain factors (i.e. stays abroad, FL learning, year <strong>of</strong> study, gender)<br />

signific<strong>an</strong>tly influence <strong>the</strong> ICC <strong>of</strong> students?<br />

RQ3 Is <strong>the</strong> ICC <strong>of</strong> English l<strong>an</strong>guage students different from <strong>the</strong> ICC <strong>of</strong> students from<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r departments, due to intensive instruction in English coupled with culture<br />

<strong>an</strong>d literature cl<strong>as</strong>ses?<br />

RQ4 Are students competent to navigate certain intercultural encounters presented to<br />

<strong>the</strong>m <strong>an</strong>d what do <strong>the</strong>y use in terms <strong>of</strong> attribution to account for IC<br />

differences?<br />

It w<strong>as</strong> hoped that <strong>an</strong>swers to <strong>the</strong>se question would contribute to a better<br />

underst<strong>an</strong>ding <strong>of</strong> ICC in <strong>the</strong> university setting. Additionally, <strong>the</strong>y might not only provide<br />