Local Health Agency Exploratory Research Literature Review

Local Health Agency Exploratory Research Literature Review

Local Health Agency Exploratory Research Literature Review

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Local</strong> <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Agency</strong> <strong>Exploratory</strong> <strong>Research</strong><br />

<strong>Literature</strong> <strong>Review</strong><br />

December 2006<br />

Submitted to:<br />

Colorado State Tobacco Education & Prevention Partnership<br />

Colorado Department of Public <strong>Health</strong> & Environment<br />

Prevention Services Division

Submitted by:<br />

One Park Square<br />

75 Washington Avenue<br />

Portland, Maine 04101<br />

Phone 207-767-6440<br />

Fax 207-767-8158<br />

Center for <strong>Health</strong> Policy, Planning and <strong>Research</strong><br />

716 Stevens Ave<br />

Portland, ME 04101

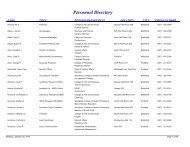

TABLE OF CONTENTS<br />

OVERVIEW AND PURPOSE ................................................................................................................ 1<br />

NATIONAL GUIDANCE FOR STATE AND LOCAL HEALTH AGENCY ROLES....................................... 5<br />

The Guide to Community Preventive Services................................................................... 5<br />

NIH State of the Science Conference Statement on Tobacco Use: Prevention, Cessation,<br />

and Control.......................................................................................................................... 6<br />

Promising Practices in Chronic Disease Prevention and Control: A Public <strong>Health</strong><br />

Framework for Action......................................................................................................... 6<br />

Best Practices for Comprehensive Tobacco Control Programs for Comprehensive<br />

Tobacco Control Programs ................................................................................................. 7<br />

The American Stop Smoking Intervention Study for Cancer Prevention (ASSIST).......... 7<br />

ROLES OF STATES AND LOCAL AGENCIES IN STATES WITH CLEAN INDOOR AIR LAWS .................. 9<br />

Youth Focused Efforts ...................................................................................................... 10<br />

Peer-Mentor Programs...................................................................................................... 10<br />

Media/Counter-Marketing Campaigns ............................................................................. 11<br />

Quit Lines.......................................................................................................................... 14<br />

Physician Education Efforts.............................................................................................. 18<br />

ENFORCEMENT............................................................................................................................... 19<br />

Smokefree Policies............................................................................................................ 19<br />

Broadening Protection from Environmental Tobacco Smoke .......................................... 21<br />

Youth Access Restrictions ................................................................................................ 22<br />

ELIMINATING DISPARITIES IN TOBACCO USE................................................................................. 24<br />

STATE ROLES OF SURVEILLANCE AND TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE ................................................... 26<br />

Surveillance....................................................................................................................... 26<br />

Evaluation ......................................................................................................................... 27<br />

THE CLEAN AIR STATES: APPROACHES TO FUNDING, ADMINISTRATION AND MANAGEMENT OF<br />

LOCAL HEALTH AGENCIES AND TOBACCO PROGRAMS.................................................................. 29<br />

REFERENCES .................................................................................................................................. 36

OVERVIEW AND PURPOSE<br />

In March 2006, the State of Colorado passed a new clean indoor air act prohibiting smoking in<br />

most indoor areas throughout the state. This ban, affecting restaurants, bars, and other<br />

businesses, went into effect in July 2006. Before the state-wide law came into effect, state and<br />

local governments in Colorado had largely been focusing their work around tobacco control on<br />

passing ordinances or laws to ban indoor smoking at the state and local level. Now, under the<br />

new law, there is a need for a shift in focus of the work of these organizations and refocus on<br />

other needed issue areas associated with freedom from second-hand smoke, smoking prevention<br />

and cessation programs.<br />

The purpose of this document is to examine the potential implementation, administration,<br />

enforcement and surveillance roles of local health agencies in a state with a state-wide smoking<br />

ban and to explore the implications of the state-wide ban on the role of local agencies in<br />

developing and implementing evidence-based tobacco control programs and policies at the<br />

community level. This report reviews the applicable literature and includes a discussion of<br />

comparable activities occurring throughout the United States, with a focus on states that have<br />

enacted clean indoor air acts similar to the new Colorado law. State tobacco program evaluation<br />

and planning reports developed by those states with state-wide smoking bans, as well as<br />

important national publications on the topic were included in this document.<br />

Surgeon General: Secondhand Smoke a National Priority<br />

The Surgeon General first acknowledged the issue of involuntary exposure to tobacco smoke<br />

(also referred to as secondhand smoke or environmental tobacco smoke) in 1972, and, by 1986<br />

concluded that involuntary smoking caused lung cancer in lifetime nonsmoking adults and<br />

adverse effects on respiratory health in children and that separating smokers and nonsmokers in<br />

the same airspace reduced but did not eliminate the exposure to secondhand smoke (US<br />

Department of <strong>Health</strong> and Human Services, 1986).<br />

The 1986 Surgeon General findings, supported by reports released in 1986 by the International<br />

<strong>Agency</strong> for <strong>Research</strong> on Cancer of the World <strong>Health</strong> Organization (International <strong>Agency</strong> for<br />

<strong>Research</strong> on Cancer, 1986) and the National <strong>Research</strong> Council (1986) provided an important<br />

impetus to a growing movement in California and other states to restrict smoking in public<br />

places and workplaces. And, since 1986, the evidence regarding the adverse health effects of<br />

secondhand smoke and burden on health continued to mount, with the release of additional<br />

reports from federal, state, and international agencies (US EPA, 1992), (California EPA, 1997),<br />

(CDC, 2002), (World <strong>Health</strong> Organization, 1999). In response, many local and state<br />

governments have enacted policies to prohibit smoking in restaurants, bars, and workplaces.<br />

Colorado’s legislation is one of the most recent of those policies.<br />

In June 2006, shortly after the Colorado clean indoor air legislation was passed, the US Surgeon<br />

General released a report on the <strong>Health</strong> Consequences of Involuntary Exposure to Tobacco<br />

Smoke. This report evaluated new evidence on the subject of “second hand smoke” or<br />

“environmental tobacco smoke” exposures and updated prior Surgeon General findings on the<br />

1

subject (US Department of <strong>Health</strong> and Human Services, 2006). It made the following<br />

conclusions:<br />

• Secondhand smoke causes premature death and disease in children and in adults who do<br />

not smoke.<br />

• Children exposed to secondhand smoke are at an increased risk for sudden infant death<br />

syndrome (SIDS), acute respiratory infections, ear problems, and even more severe<br />

asthma. Smoking by parents causes respiratory symptoms and slows lung growth in their<br />

children.<br />

• Exposure of adults to secondhand smoke has immediate adverse effects on the<br />

cardiovascular system and causes coronary heart disease and lung cancer.<br />

• There is no risk-free level of exposure to secondhand smoke<br />

• Many millions of Americans, both children and adults, are still exposed to secondhand<br />

smoke in their homes and workplaces despite substantial progress in tobacco control.<br />

• Eliminating smoking in indoor spaces fully protects nonsmokers from exposure to<br />

secondhand smoke. Separating smokers from nonsmokers, cleaning the air, and<br />

ventilating buildings cannot eliminate exposures of nonsmokers to secondhand smoke.<br />

The 2006 report, which stated that there was massive and conclusive scientific evidence<br />

documenting the adverse effects of secondhand smoke and calling the issue an important<br />

national priority, was the climax of many years of mounting evidence regarding secondhand<br />

smoke and gives further weight to the importance of the new Colorado legislation.<br />

The recommendations of the Surgeon General, World <strong>Health</strong> Organization and others represent a<br />

dramatic shift from the previous emphasis on direct interventions to address behavioral risk<br />

factors to intermediate outcomes in the “causal pathway between a determinant and the final<br />

health outcome” which include quality-of-life, social, and environmental effects beyond the<br />

intended health outcomes. This approach places a new importance on second hand smoke for<br />

both practitioners and policymakers at state and local levels (Truman, 2000).<br />

This shift toward environmental effects is evident in the <strong>Health</strong>y People 2010 initiative; as well<br />

as internationally in the Ottawa Charter; and various Canadian, European, and World <strong>Health</strong><br />

Organization initiatives in health promotion and population health. (Green, 2000).<br />

States with Clean Indoor Air Acts<br />

According to the 2006 Surgeon General’s report, most of the progress in adopting laws making<br />

public places and workplaces smoke-free has occurred at the local level and, more recently, at<br />

the state level. <strong>Local</strong> initiatives originally led the way because local governments tended to be<br />

more responsive to public sentiment on this issue. The progress in implementing local<br />

ordinances in hundreds of communities across the US, including high profile cities such as New<br />

York and Boston, has demonstrated that ordinances are popular, can be implemented with little<br />

difficulty, and are met with high levels of compliance. They also substantially reduce exposure<br />

to secondhand smoke (Picket et al., 2006). Laws also have been shown to not have a negative<br />

economic impact on restaurants and bars and may even increase revenues (Cowling and Bond,<br />

2

2005). Progress has also been helped by the growing tendency to view smoke-free laws as a<br />

protection for workers, particularly hospitality workers.<br />

Table 1 presents the states with relevant clean indoor air acts banning smoking in restaurants,<br />

bars, and/or workplaces and the date when the smoking ban went into effect or is expected to go<br />

into effect. Workplace bans include both public and private non-hospitality workplaces,<br />

including but not limited to offices, factories, and retail stores. Restaurant bans include any<br />

attached bar in the restaurants. Bar bans include all freestanding bars without separately<br />

ventilated rooms (American Nonsmokers’ Rights Foundation, 2006). The first state-wide<br />

smoking ban that included restaurants came into effect in California and Utah in 1995.<br />

California began its smoking ban in bars in 1998. In the past five years, many other states<br />

followed.<br />

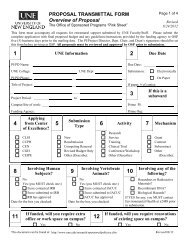

Table 1: States with Smoking Bans in Bars, Restaurants, and Workplaces*<br />

State<br />

Extent of Ban and Effective Date<br />

Restaurants Bars Workplaces<br />

California Jan 1995 Jan 1998<br />

Utah Jan 1995 Jan 2009 May 2006<br />

South Dakota July 2002<br />

Delaware Nov 2002 Nov 2002 Nov 2002<br />

Florida July 2003 July 2003<br />

New York July 2003 July 2003 July 2003<br />

Connecticut Oct 2003 April 2004<br />

Maine Jan 2004 Jan 2004<br />

Idaho July 2004<br />

Massachusetts July 2005 July 2005 July 2005<br />

Rhode Island March 2005 March 2005 March 2005<br />

North Dakota Aug 2005<br />

Vermont Sept 2005 Sept 2005<br />

Montana Oct 2005 Sept 2009 Oct 2005<br />

Washington Dec 2005 Dec 2005 Dec 2005<br />

New Jersey April 2006 April 2006 April 2006<br />

Colorado July 2006 July 2006<br />

Hawaii Nov 2006 Nov 2006 Nov 2006<br />

Louisiana Jan 2007 Jan 2007<br />

* The District of Columbia and Puerto Rico have both passed bans. DC banned smoking in workplaces<br />

as of April 2006 and in restaurants and bars as of January 2007. Puerto Rico banned smoking in<br />

workplaces as of March 2007.<br />

Many of the states that have passed smoking bans are in the first year or two of implementation,<br />

therefore the experience of local governments during implementation has not been widely<br />

documented in the peer reviewed literature. Additional information on this subject likely will<br />

become available as time goes by and additional states have a longer history of smoking bans<br />

and additional documentation of their experiences. In the meantime, much of the literature on<br />

the implementation and after-effects of a state-wide ban comes from states like California, where<br />

3

many years of a smoking ban have produced some lessons learned that may be useful to<br />

Colorado. Other states, such as New Jersey for example, offer limited, preliminary information<br />

on implementing a state-wide indoor air act, although they are still in the early years of the ban.<br />

New York was the third state to go smokefree (after California and Delaware), and brought<br />

legitimacy to the struggle for clean indoor air legislation in other states because of its<br />

comprehensive approach, diversity, geographic size and population (Stoner and Foley, 2005).<br />

Once evidence came in showing that New York’s law was working, many other states followed<br />

suit. Although many states are in the early stages of a ban, there is ample evidence available<br />

from states like California and New York on best practices for controlling smoking and<br />

promoting cessation after a ban is in place. This information may be useful to state and local<br />

tobacco policymakers in Colorado and elsewhere as they continue their work on this issue. It is<br />

important to note that most states credit the groundwork done by local health agencies at the<br />

community level for laying the necessary foundation for the statewide ban. In addition, most see<br />

the ban as part of a comprehensive tobacco control program. Thus, comprehensive, statewide<br />

smoking bans are generally a success attributable to the collaboration between state-wide<br />

agencies and interests with the local health agencies and community organizations. These<br />

ongoing collaborative efforts, both before and after enactment of the statewide laws, are the<br />

focus of this report.<br />

4

NATIONAL GUIDANCE FOR STATE AND LOCAL HEALTH AGENCY ROLES<br />

The CDC recommends a statewide strategy that emphasizes the number of organizations and<br />

individuals involved in education and training programs at the community level. Although<br />

statewide policies are critical to the success of tobacco control goals, they must be reinforced by<br />

community-based strategies, which are capable of influencing social norms and behaviors in the<br />

population.<br />

Clean indoor air acts have been shown to be an effective method of reducing tobacco exposure.<br />

However, acts like the Colorado Clean Indoor Air Act are only one component of a<br />

comprehensive state tobacco control program. A comprehensive state program typically<br />

includes community-level activities and advocacy, school-based education, cessation programs,<br />

and policies that restrict youth access to tobacco products and increase the price for products and<br />

media campaigns to counteract tobacco advertising.<br />

The Centers for Disease Control and the National Institutes for <strong>Health</strong> have issued reports on the<br />

best practices for statewide policy and community-based strategy in tobacco control. There is<br />

clear evidence that state programs make a difference and prevent deaths due to tobacco use<br />

(National Cancer Policy Board, 2000), however the role of local health agencies has also been<br />

shown to have a critical role, and the best practice to address tobacco use and second hand smoke<br />

exposure is a statewide policy that works with local agencies for community based<br />

implementation (Zaza, 2005).<br />

The Guide to Community Preventive Services<br />

The Guide to Community Preventive Services (Community Guide), developed by the Task Force<br />

on Community Preventive Services (TFCPS), provides recommendations to states and<br />

communities regarding population-based interventions to promote health and prevent disease<br />

based on systematic reviews of topics. With respect to tobacco, the Community Guide addresses<br />

the effectiveness of community based interventions to reduce youth tobacco initiation, reduce<br />

environmental tobacco smoke, and enable smoking cessation through population-based strategies<br />

(Tobacco Guide to Preventive Services, 2005).<br />

In order to reduce youth initiation, TFPCS strongly recommends two, primarily state-level<br />

activities; increasing the unit price for tobacco products, particularly through raising state and<br />

federal excise taxes and developing extensive and extended mass media campaigns particularly<br />

as centerpieces combined with other, local-level strategies. To decrease the effects of ETS, the<br />

TFCPS strongly recommends developing laws and regulations to restrict or ban tobacco<br />

consumption in workplaces and general areas used by the public. Addressing smoking cessation<br />

from a population orientation, the TFCPS turns to community-level activities, strongly<br />

recommending the use of broadcast and print media, provider education and implementation of<br />

self-reminder systems to ensure that the issue is raised during clinical exams and telephone<br />

counseling and support services. At the state level, increasing the unit price for tobacco products<br />

is also strongly recommended.<br />

5

Community level data, gained through information systems developed and distributed by the<br />

state health department as part of its technical assistance program, should inform collaborative<br />

efforts between state agencies and county and city health departments. The collaborative effort<br />

should then focus on the application of guideline practices specific to each community setting,<br />

making use of the local expertise of local health agencies. In this way, state-wide policy can be<br />

tailored to local needs, and, with the assistance of the evidence found in the Community Guide, a<br />

state and local collaborative effort will “weave together a locally responsive yet comprehensive<br />

statewide approach” (Wasserman, 2000).<br />

NIH State of the Science Conference Statement on Tobacco Use: Prevention,<br />

Cessation, and Control<br />

The June 2006 National Institutes for <strong>Health</strong> State of the Science Conference Statement on<br />

Tobacco Use: Prevention, Cessation, and Control provided general consensus and guidance to<br />

State and local governments in Colorado on key issues around tobacco prevention, cessation, and<br />

control (NIH, 2006). Three general approaches to preventing tobacco use specifically in young<br />

adults were promoted, including: 1) taxation of tobacco products to increase their prices; 2)<br />

passage of laws and regulations that prevent young people from gaining access to tobacco<br />

products, reduce their exposure to tobacco smoke, or restrict industry advertising; and 3) mass<br />

media campaigns. While school-based interventions have also been shown to be effective in the<br />

short term, the conference concluded that there is a need to develop school-based strategies that<br />

lead to sustained reduction in starting to use tobacco.<br />

NIH concluded that the most effective cessation strategies were: mass media campaigns;<br />

telephone smoking cessation support that gives advice to stop smoking (e.g., quit line); an<br />

increase in the unit price for tobacco products, and a reduction in out-of-pocket costs for<br />

cessation therapies.<br />

Specifically at the community level, NIH concluded that local media campaigns, communitylevel<br />

quit lines, increases in tobacco pricing and taxation, and community-based cessation<br />

services were effective strategies. Community-based self help materials alone were not proven<br />

to be effective.<br />

Promising Practices in Chronic Disease Prevention and Control: A Public <strong>Health</strong><br />

Framework for Action<br />

Promising Practices in Chronic Disease Prevention and Control: A Public <strong>Health</strong> Framework for<br />

Action (2003) provides additional guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention<br />

(CDC) for tobacco control programs at the local level, with examples of how state and local<br />

health departments can develop evidence-based programs, leverage their limited resources, and<br />

coordinate the efforts with stakeholder groups. CDC emphasizes the utility of partnering with<br />

local and community groups, suggesting that state tobacco programs should partner with any<br />

group that has overlapping interests, from national nongovernmental health organizations (e.g.,<br />

American Cancer Society, to NIH or CDC, to groups representing specific local constituencies.<br />

<strong>Local</strong> groups can help state officials design interventions that target local residents appropriately.<br />

6

Best Practices for Comprehensive Tobacco Control Programs for Comprehensive<br />

Tobacco Control Programs<br />

Earlier CDC guidance on evidence-based interventions at the local level is available in Best<br />

Practices for Comprehensive Tobacco Control Programs for Comprehensive Tobacco Control<br />

Programs (1999). This document encouraged state programs to include the following programs<br />

at the local level: community programs to reduce tobacco use, school programs in coordination<br />

with local community coalitions, enforcement activities aided by local organizations, technical<br />

assistance to local programs, surveillance and evaluation efforts that measure local and statewide<br />

progress, and administration and management in collaboration with state and local<br />

agencies.<br />

The American Stop Smoking Intervention Study for Cancer Prevention (ASSIST)<br />

The National Cancer Institute (NCI), in collaboration with the American Cancer Society (ACS),<br />

produced The American Stop Smoking Intervention Study for Cancer Prevention, or ASSIST.<br />

ASSIST focused on four policy areas: (1) eliminating exposure to environmental tobacco smoke,<br />

(2) promoting higher taxes for tobacco, (3) limiting tobacco advertising and promotions, and (4)<br />

reducing minors’ access to tobacco products. Seventeen state health departments (Colorado,<br />

Indiana, Maine, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, New Jersey, New Mexico, New<br />

York, North Carolina, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Virginia, West Virginia, Washington, and<br />

Wisconsin) participated in the ASSIST project. The ASSIST states implemented the project in<br />

two phases: a 2-year planning phase (1991-1993) and a 6-year implementation phase (1993-<br />

1999). This project represented the first major nationwide effort to create state-level tobacco<br />

control infrastructures.<br />

The ASSIST project required states to develop strategic alliances with a variety of organizations<br />

and agencies, including national, state, and local agencies and organizations. At the state level,<br />

each health department was required to establish a comprehensive tobacco control program,<br />

build a coalition for tobacco control and provide leadership for community level coalitions<br />

(ASSIST, 2005). At the end of the intervention period, the ASSIST states had statistically<br />

significantly lower adult smoking prevalence than non-ASSIST states. The real focus of the<br />

ASSIST project, however, was on policy change, which was assessed with an “initial outcomes<br />

index” (IOI), measuring the percentage of workers in 100% smoke-free workplaces, the price of<br />

cigarettes including tax, and a rating of local and state clean-indoor air policies. Increases in IOI<br />

scores were associated with proportional decreases in per capita cigarette consumption,<br />

regardless of the starting IOI score. Thus, the ASSIST project demonstrated a causal relationship<br />

between tobacco control policy change and per capita tobacco consumption.<br />

ASSIST states were associated with improvements in policy environment (i.e., increased IOI<br />

score) only during the first years of the intervention. By 1994, three years into the ASSIST<br />

project, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation<br />

and others were implementing programs in both ASSIST and non-ASSIST states, making it<br />

difficult to identify differences between ASSIST and non-ASSIST states. The differences<br />

attributable to policy changes held throughout this period however, and states with higher<br />

capacity and tobacco control infrastructure had statistically significantly lower per capita<br />

7

consumption rates than states with lower capacity, regardless of their ASSIST status (Stillman,<br />

2003).<br />

In summary, national guidance on best practices for state tobacco control programs indicates<br />

that state programs will be most effective if they partner with local and community groups to<br />

design interventions that appropriately target local residents and tailor community-based<br />

interventions to local populations. A comprehensive strategy for tobacco control at the<br />

community level would include, at a minimum:<br />

• An increase in the unit price for tobacco products,<br />

• Mass media education campaigns,<br />

• Cessation support (quit lines).<br />

Other interventions may include cessation services in community settings, a reduction in out-ofpocket<br />

costs for cessation therapies, and school-based interventions. There may be<br />

opportunities to partner with local groups to carry out a variety of aspects of a tobacco control<br />

program, from development of school programs to enforcement to surveillance and evaluation.<br />

8

ROLES OF STATES AND LOCAL AGENCIES IN STATES WITH CLEAN INDOOR AIR<br />

LAWS<br />

In general, local health agencies have had demonstrated success in tackling tobacco control<br />

issues throughout the country. And, in states where local agencies were instrumental in<br />

developing support for the enactment of smokefree laws, in most cases, they have also been an<br />

ally in the development of programs and policies to move the state forward.<br />

According to the 2006 Surgeon General’s Report, early local progress in enacting smokefree<br />

laws, or clean indoor air policies, was furthered by support by state tobacco control programs<br />

and other state organizations to develop and maintain a network of local coalitions (US<br />

Department of <strong>Health</strong> and Human Services, 2006). By backing and funding local changes, state<br />

programs were able to strengthen the work of community groups and local health agencies,<br />

helping them to achieve progress on evidence-based approaches by giving support through<br />

training and technical assistance. Some had extensive experience with local smoke-free<br />

ordinances at the community level before implementing a state-wide law (Maine, Massachusetts<br />

and New York). This prior local-level experience made it easier to transition to state-wide<br />

legislation. Other states, like Connecticut, faced a more frustrating path with a state law that<br />

regulated smoking in a limited array of venues (municipal and state-owned buildings, grocery<br />

stores, and hospitals) and that contained a clause pre-empting municipalities from passing<br />

additional local laws to regulate smoking (Blumenthal, 2002).<br />

After initial passage of state smokefree laws, existing community coalitions that may have been<br />

integral in achieving the passage of these laws, ideally should be supported by the state to<br />

continue to achieve further successes in controlling tobacco. The concentration of efforts at the<br />

city and county level has been noted as one of the highlights of California’s program and the<br />

reason for its success (Green et al., 2006). Additionally, a study on ten state tobacco control<br />

programs found that every state identified either community programs or counter marketing as<br />

the highest priority. Community programs were high priority because states felt that changes in<br />

policies and social norms are most likely to occur at the community level (Mueller et al., 2006).<br />

Most states with comprehensive smokefree laws have continued their work in this area, focusing<br />

on smokefree homes and cars, as well as drifting smoke in public outdoor areas and shared<br />

housing (California Department of <strong>Health</strong> Services, Tobacco Control Section, 2003). These<br />

efforts are often led by local jurisdictions, working with housing unit owners or disseminating<br />

information on smokefree homes and cars throughout the community. <strong>Local</strong> jurisdictions have<br />

also been active in passing additional smoke-free ordinances, making areas such as beaches and<br />

parks smokefree.<br />

In this section we explore the roles of states and local agencies in developing and implementing<br />

specific programs, with particular attention to states with existing indoor air laws. The evidence<br />

is strongly that state-wide comprehensive tobacco control programming, when combined with<br />

strong local policies, has an effect beyond that predicted by either programs or policies alone<br />

(Hyland et al., 2006). Further, statewide projects can increase the capacity of local programs by<br />

providing technical assistance on program evaluation, media advocacy, implementation of smoke<br />

9

free policies, and reduction of minor’s access to tobacco. With the passage of indoor air<br />

legislation in Colorado, the state may now find new ways to utilize existing infrastructure and<br />

resources at the local level to continue to improve tobacco control and to increase the<br />

effectiveness of local and community programming.<br />

Youth Focused Efforts<br />

Since the vast majority of smokers initiate during adolescence and addiction begins during the<br />

first few years of use, early interventions appear to offer a sensible approach. A study based on<br />

interviews of tobacco control representatives from Oregon, California, Mississippi, and<br />

Massachusetts found that the best return on investment in a tobacco control program is to reach<br />

youth through a youth prevention program before they begin smoking (Gleckler et al., 2001).<br />

The CDC’s Guidelines for School <strong>Health</strong> Programs to Prevent Tobacco Use and Addiction<br />

(Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1994) presents a range of strategies that have been<br />

demonstrated to be effective in preventing tobacco use among youth. The CDC defines tobaccofree<br />

school environments as those with policies that prohibit smoking and tobacco use in all<br />

areas inside and outside the school building, and applies to all tobacco products; all students,<br />

staff and visitors must adhere to this policy, and it is in effect 24 hours a day. (Centers for<br />

Disease Control and Prevention, 2006). Schools are encouraged to:<br />

• Develop and enforce a school policy on tobacco use<br />

• Provide instruction about short- and long-term negative physiologic and social<br />

consequences of tobacco use, social influences and peer norms regarding tobacco use,<br />

and refusal skills.<br />

• Provide tobacco-use prevention education in grades K-12, with intensive instruction in<br />

middle school that is reinforced in high school.<br />

• Provide program-specific training for teachers.<br />

• Involve families in support of school-based programs to prevent tobacco use.<br />

• Support cessation efforts among students and all school staff who use tobacco.<br />

• Routinely assess the tobacco-use prevention program in schools.<br />

Peer-Mentor Programs<br />

Youth-led community groups or “youth empowerment groups” are widely used in state tobacco<br />

control programs as a presence in the community that works to change norms about tobacco<br />

through peer influence. Florida was the first state to develop a youth movement against tobacco;<br />

when youth smoking rates declined in Florida, other states followed (O’Riordan et al., 2005).<br />

The “Truth” program fostered community partnerships with all 67 Florida counties, school based<br />

initiatives, an education and training initiative, enhanced enforcement of youth tobacco access<br />

laws, and a law that penalized youth for possession of tobacco (Wakefield and Chaloupka,<br />

2000). Due to the “Truth” program, a higher level of anti-tobacco awareness exist in Florida<br />

than in other states across the nation (Niederdepp, 2004).<br />

10

A similar program in Hawaii, the REAL: Hawaii Youth Movement Against the Tobacco<br />

Industry, has more than 2,500 members statewide. This program provides youth-run, youth, led<br />

initiatives aimed at raising awareness about tobacco prevention and the tobacco industry’s media<br />

campaigns, empowering youth, and developing advocacy and leadership skills. Partnerships<br />

have been developed with the state tobacco program, the American Cancer Society, the<br />

Department of Education’s Peer Education Program, and the Coalition for a Tobacco Free<br />

Hawaii (O’Riordan et al., 2005). In addition, Maine’s Partnership for A Tobacco Free Maine<br />

funds 31 local programs throughout the state to design and conduct community- and schoolbased<br />

programs. Each local grantee is responsible for the development of a Youth Advocacy<br />

Program.<br />

At the university level, similar youth empowerment programs have been shown to be effective.<br />

For example, the Student Tobacco Reform Initiative: Knowledge for Eternity (STRIKE) was<br />

implemented to target university students and engage students as advocates for deconstruct<br />

tobacco’s role on college campuses. This program was piloted on nine Florida campuses with<br />

funding given to the universities to implement the program (Morrison and Talbott, 2005).<br />

Teacher-focused interventions and anti-tobacco school policies also appear to increase the<br />

motivation, confidence and effectiveness of teachers in providing anti-tobacco education to<br />

students (Soza-Vento and Tubman, 2004). In addition, many states have funded the teaching of<br />

anti-tobacco curricula. Vermont’s Department of Education and Department of <strong>Health</strong> have<br />

partnered to give grants to school districts to teach research-based curricula on prevention,<br />

following the CDC Guidelines for school-based tobacco reduction. These funds also support<br />

cessation services for teens and peer leadership and youth empowerment programs (State of<br />

Vermont, 2006). In Washington State, funding is given to Educational Service districts to help<br />

schools improve and enforce tobacco-free policies, establish stop-smoking programs for<br />

students, deliver research-based curricula, train teachers and staff, and provide information to<br />

families (Washington State Department of <strong>Health</strong>, 2005). In Massachusetts, the state<br />

Department of Public <strong>Health</strong> has traditionally contracted with school health services to<br />

implement cessation services and health curricula. These school-based activities have<br />

complemented community-based programs and activities of local health departments (Koh,<br />

2005).<br />

Media/Counter-Marketing Campaigns<br />

Mass media campaigns to inform and motivate individuals to stay tobacco-free have been shown<br />

to be effective, particularly when used in combination with other interventions such as increases<br />

in costs of tobacco products and school-based education programs. Mass media social marketing<br />

campaigns are designed to provide an alternative perspective to tobacco industry marketing.<br />

Campaigns are often developed at the state level, sometimes in conjunction with local and<br />

community groups. <strong>Local</strong> entities often help in the dissemination at the local level and, in some<br />

states, have developed their own smaller media campaigns.<br />

The CDC provides justification and evidence in support of counter-marketing activities to<br />

promote smoking cessation, decrease the likelihood of initiation, and influence public support for<br />

11

tobacco control interventions and community- and school-based efforts. Using paid media<br />

placement, rather than relying on public service announcements and other free or low-cost<br />

methods, is necessary to ensure adequate levels of exposure. Counter-marketing efforts should<br />

be used in combination to address prevention, cessation, and protection from second hand<br />

smoke, and they should target both young people and adults, addressing individual behaviors and<br />

public policies. Counter marketing strategies work best when they include grassroots<br />

promotions and work in conjunction with community programs. Rather than repeating a single<br />

message, campaigns should maximize the number, variety, and novelty of messages. In addition,<br />

messages should be more collegial than authoritarian in nature (CDC, 1999).<br />

SmokeFreeColorado’s Outreach Implementation SubCommittee Key Informant Interviews<br />

(2006) found that local agencies were key in the development of community-specific messages.<br />

Advertisements have been found to be a frequently mentioned source of help among recent<br />

quitters (Beiner et al., 2006). Thus, counter-advertising can increase demand for local resources,<br />

and those responsible for the provision of local resources should be aware of marketing<br />

campaigns that may affect demand for their services. In Massachusetts, for example, counteradvertising<br />

campaigns disseminate messages that focus public attention on the tobacco problem,<br />

while the statewide resource center concurrently forges partnerships to drive change at the<br />

community level (Koh et al., 2005).<br />

In New York, the New York State Tobacco Control Program’s (NYSTCP) media plan utilizes<br />

community and local groups extensively in message development. This program is cited as one<br />

of the most extensive uses of community groups to conduct media and counter-advertising<br />

campaigns. Community Partnerships are provided with $6 million to collaboratively run<br />

statewide media with the State Department of <strong>Health</strong>. Although this program functioned<br />

effectively, there were occasions where the work of Community Partnerships had to be stopped<br />

and restarted when contracts were discontinued and funding was lost for certain periods of time.<br />

The evaluation of the program recommended that the functioning of the program could have<br />

been better if the contract renewal process were improved so that swings in activity from<br />

grantees were reduced. The evaluation also recommended that Community Partnerships be<br />

better used to consistently cultivate relationships with media outlets to fully utilize opportunities<br />

for donated advertising time (RTI, 2006).<br />

In cases where the Community Partnership ads were used to promote clean indoor air<br />

regulations, these ads were rated as low impact because they lacked emotional appeals and<br />

intense images. This does not necessarily mean that they are poorly developed ads, but the<br />

objectives associated with clean indoor air are of an educational nature and are not necessarily<br />

suited to high impact images. Secondhand smoke ads highlighting health impacts that used more<br />

emotional appeals tended to have a higher impact, particularly those that encouraged adults to<br />

not smoke in the presence of children (RTI, 2006). This finding aligns with other findings on the<br />

efficacy of ads. Advertisements that evoke strong emotion and portray the serious consequences<br />

of smoking generally have been found to be more effective (Koh et al., 2005; Biener, 2004).<br />

When properly coordinated, media campaigns can enable and support community level<br />

initiatives (Siegel, 2002). In Texas, rates of smoking reduction among adults in areas that<br />

received high-intensity anti-smoking media campaigns along with community-level programs<br />

12

and cessation services were three times higher than in areas that received no services or media<br />

messages. Smoking reduction rates in areas that received media messages alone, without<br />

community programs or cessation services, were twice as high as areas that received no<br />

interventions (McAlister, 2004).<br />

Vermont has also used state and local collaboration to develop “common theme campaigns” that<br />

deliver messages from multiple sources – statewide media, community coalitions, local schoolbased<br />

tobacco coordinators, and local hospital-based cessation coordinators. State and local<br />

activities are coordinated during three specific times of the year. Common theme campaigns<br />

were focused around: 1) youth prevention, targeted toward age 10-17, 2) smoking cessation,<br />

linking adults to cessation resources around the Great American Smokeout in November and<br />

New Years Day, and 3) secondhand smoke, encouraging people not to smoke in homes or cars<br />

(State of Vermont, 2006).<br />

Successful anti-smoking campaigns specifically targeted toward youth are often based on<br />

aggressive advertising educating youths on corporate marketing practices of the tobacco<br />

industry. In Florida, youths who viewed advertisements about tobacco industry manipulation of<br />

youths were substantially less likely to begin smoking (Siegel, 2002), (Niederdeppe, 2004).<br />

Many states have used this tactic, some in conjunction with community partners. For example,<br />

New Jersey, which just began implementation of an indoor air law in 2006, has had a youth-led<br />

anti-tobacco movement since 2000 called Reaching Everyone by Exposing Lies (REBEL).<br />

REBEL has trained high school graduates and college students to develop anti-tobacco<br />

initiatives. REBEL rallied youth to launch the Not For Sale advertising campaign in the state<br />

(New Jersey Comprehensive Tobacco Program, 2001).<br />

Among adolescents, reductions in tobacco use have been highest when intensive media<br />

campaigns and comprehensive community programs are combined. Intensive media campaigns<br />

combined with enhanced school programs achieve slightly lower, but significant reductions in<br />

tobacco use. These patterns are also demonstrated to reduce smoking intentions among youth<br />

(Mesack, 2004).<br />

While media campaigns generally tend to be expensive, there are ways to lower the budget in<br />

states with limited funds for tobacco control. In 1997, several years after Utah’s smokefree<br />

restaurant law went into effect, the state began a low-budget media campaign to target youth<br />

smoking, conducting interviews with other states that had already developed intensive media<br />

campaigns. Focus groups were conducted with youth who used tobacco and did not use tobacco<br />

to identify the most effective ads from various states, according to Utah teens. Given financial<br />

limitations, the process of interviewing other states and drawing from their experiences, as well<br />

as conducting focus groups was a useful way to develop messages at low cost (Murphy, 2000).<br />

Counter-advertising also does not have to take the form of a mass media campaign. Gains can be<br />

made by using community and local groups to help advocate against the tobacco industry in their<br />

area. In California, passage of city ordinances in San Francisco, Los Angeles, and San Diego<br />

have also effectively restricted advertising near the schools (Green et al., 2006). Additionally,<br />

several California Partnerships for Priority Populations have engaged in efforts to combat<br />

tobacco industry advertising and sponsorship in their communities. Some activities they have<br />

engaged in include: working with organizations in their communities to adopt policies that<br />

13

prohibit tobacco industry sponsorship; conduct educational campaigns about sponsorship issues,<br />

opposing donations, and reducing public display of products that use American Indian images<br />

(Toward a Tobacco-Free California, 2006).<br />

Community Partnerships in New York also advocated for the elimination of tobacco<br />

advertisement and offered incentives for eliminating or reducing tobacco advertising by sending<br />

mass mailings to store owners. Community Partnerships had realistic objectives, targeting one<br />

or two retailers in their area – often those with lower levels of advertising – which was a good<br />

start in this area. The evaluators of this program suggested concentrating on mass<br />

merchandisers, large grocery stores, and pharmacies because these retailers are less likely to<br />

participate in tobacco industry programs and rely less on tobacco revenue. Pharmacies and large<br />

grocery stores – particularly local chains – may be more concerned about their image and more<br />

likely to change. Challenges in these efforts were difficulty contacting store owners,<br />

nonresponse to letters, store managers indicating that placement of tobacco advertisements<br />

cannot be changed at the store level, store owners’ fear of loss of incentives from tobacco<br />

companies or decrease in sales, and retailers’ lake of awareness of impact of tobacco ads on<br />

tobacco smoking (RTI, 2006).<br />

Quit Lines<br />

Cessation services seem like an idea focus area for community organizations, running<br />

decentralized cessation centers. However, the main focus for states in this area has been the Quit<br />

Line, which tends to be an effective means of centralizing the cessation services and reaching<br />

people throughout the state and connecting patients to local resources.<br />

CDC’s Guide to Community Preventative Services recommends cessation programs such as a<br />

Quit line as an effective intervention at the community level. Although Quit Lines may not be as<br />

effective as face-to-face clinical contact, telephone counseling has been found to be effective<br />

relative to interventions with no personal contact (Murphy and Aveyard, 2005). Quit Lines also<br />

are more likely to be used than traditional counseling because they offer accessible counseling to<br />

people throughout a state or region who may have limited mobility, because they are large<br />

enough to offer counseling to a variety of ethnic groups and other populations with special<br />

language needs, and because they can cover areas where other services are not available (CDC,<br />

2004). Even those who are constrained by child care or transportation difficulties to participate<br />

in local programs can use the Quit Line. Evaluation of the Massachusetts Quit Line services<br />

have shown that a high percentage of callers are women, young people, and members of diverse<br />

communities who may have had barriers to accessing other quit services (Koh et al., 2005). It<br />

also is easier to promote than an array of separate local programs and saves money that can be<br />

directed to other programs. The centralized nature of a Quit Line also makes it easier to have<br />

extended Helpline hours. Other strengths are that clients are more candid when speaking over<br />

the phone to people they will never see (California Department of <strong>Health</strong> Services, 2000).<br />

Some states, like New York provide brief, on-the-spot one time counseling services to smokers<br />

who call during operating hours. This minimal counseling approach enables the state to provide<br />

services to a large number of callers. California, on the other hand, provides pro-active follow-<br />

14

up sessions according to the probability of relapse (e.g., within 24 hours of quitting, at three<br />

days, at one week, at two weeks, and at one month). Most states maintain lists of local programs<br />

for referral (CDC, 2004).<br />

In general, state Quit Line services have been offered to all those who initiate a call to the Quit<br />

Line. Vermont, however, has in the past offered a free telephone support service specifically for<br />

pregnant women smokers. Patients are referred from the Women, Infants, and Children program<br />

and telephone contact is initiated by the telephone service representatives. This service resulted<br />

in 25% self-reported abstinence from smoking at last telephone contact and 20% abstinence by<br />

the postpartum visit at the Women, Infants, and Children program. The benefit of this program<br />

is that it may succeed in reaching women who would not initiate a call to a Quit Line (Solomon<br />

and Flynn, 2005).<br />

CDC (2004) emphasizes that Quit Line community partnerships are essential. Partners can<br />

increase referrals and supplement funding. Many community partners are also in need of referral<br />

services that the Quit Line provides. Partnerships also promote closer coordination with county<br />

and local control programs, and enable the Quit Line to act as the primary resource linking state<br />

and local initiatives. For example, in New York, local coalitions feature the Quit Line in their<br />

media campaigns and use the Quit Line as a referral resource to community-based programs.<br />

Some states have also partnered with health plans. For example, Massachusetts negotiated with<br />

all of its major health plans to adopt a universal system of fax referral and proactive telephone<br />

counseling (CDC, 2004).<br />

States can partner with community groups and with local tobacco control programs to get these<br />

organizations to promote the Quit Line. In turn, the Quit Line can provide local referrals. In<br />

New York State, Community Partnerships and Cessation Centers were used to promote the Quit<br />

Line. They provided Quit Line information and giveaways at health care provider trainings and<br />

presentations. They conducted mass media efforts promoting the Quit Line (e.g., tv, radio,<br />

newspaper, billboards, etc.) They provided Quit Line information to cessation groups. They<br />

increased spending in January to capitalize on New Year’s resolutions. However, there was a<br />

lull in activities in late summer 2005 when Community Partnership contracts were not renewed<br />

in time. For every 10% increase in expenditures on television ads for the Quit Line, call volume<br />

increased by 5.3%; a 10% increase in radio or newspaper ads resulted in a 1.9% and 1.1%<br />

increase in call volume, respectively (RTI, 2006).<br />

The California Helpline began in August 1992. One of the Helpline’s interventions is to refer<br />

clients to local programs. The program works with all of the local health departments across the<br />

state to maintain up-to-date listings of legitimate (as determined at the local level) tobacco<br />

cessation services in each county. Lists are updated twice a year. The Helpline is publicized as<br />

a part of the California Tobacco Control Program’s media campaign, which advertises on<br />

television, radio, billboards, bus signs, and local newspapers. Since 1996, the Helpline has also<br />

been doing its own outreach to increase awareness among health care providers (by sending them<br />

back thank you cards), sending promotional materials to high school tobacco educators, and<br />

sending newsletters to county-level and regional, and local level partners (California Department<br />

of <strong>Health</strong> Services, 2000).<br />

15

Some Quit Lines, along with providing counseling and referrals, also provide training to health<br />

care providers For example, Washington State’s Quit Line, funded by the state Department of<br />

<strong>Health</strong>, provides residents with one-on-one counseling, quit kits, and referrals to local programs.<br />

This Quit Line also trains healthcare system workers to effectively intervene with their patients<br />

who are smokers (Washington State Department of <strong>Health</strong>, 2005). Massachusetts’ Quit Works<br />

program links providers to the Quit Line, the Quit Net (an Internet-based service) and other<br />

cessation services and promotes provider education (Koh et al., 2005).<br />

Offering free or reduced price distribution of nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) may be an<br />

effective strategy for getting people to call the Quit Line and increasing the success of their quit<br />

attempt. This strategy, in conjunction with community partners, has been used effectively in<br />

New York. The New York City Department of <strong>Health</strong> and Mental Hygiene, with the New York<br />

State Department of <strong>Health</strong>, and the Roswell Park Cancer Institute distributed free nicotine<br />

replacement therapy (NRT) to over 34,000 callers to the Quit Line in 2003. Of individuals<br />

contacted after 6 months, more NRT recipients than comparison group members quit smoking<br />

(33% vs. 6%). This program was begun at a time when new smoke-free legislation was coming<br />

into effect and increased taxation of cigarettes also focused more attention on cessation. Those<br />

who received at least one counseling call during that time also had a higher level of quitting. A<br />

quit-line driven free NRT distribution program might help increase the success rate of quitting<br />

among smokers who are seeking help (Miller et al., 2005). Maine’s Quit Line also offers free<br />

NRT to eligible callers, with higher quit rates among those who received NRT, another<br />

indication that tobacco medication access may be vital for states to maximize the impact of their<br />

programs (Swartz et al., 2005). In other areas of New York, due to budget constraints, another<br />

program sent a one-week or two-week supply of NRT to a smaller group of smokers instead of a<br />

six-week supply (and in one area, participants got a voucher sent to their home for redemption of<br />

a two-week supply at a local pharmacy). Lower quit rates (21%) were observed in areas where<br />

only a one-week supply of patches was sent. However, the cost of an intervention with only a<br />

one-week supply was far lower (Cummings et al., 2006).<br />

Free medication may not only increase success of quit attempts but may also prompt smokers<br />

who wish to quit to call the quitline (Cummings et al., 2006). Responses to a newspaper<br />

advertisement promotion to call the Quit Line for a free 2-week supply of medication resulted in<br />

a 25-fold increase in calls and a similar promotion of a Better Quit stop smoking aide that can be<br />

used as a cigarette substitute resulted in a 2-fold increase in calls (Bauer et al., 2006). Programs<br />

like these may work especially well in states when there is a climate in the state (e.g., a new<br />

indoor air law, an increase in cigarette taxes) that prompts smokers to want to quit (Murphy and<br />

Aveyard). Additional smokers may be trying to quit and be ready to take advantages of such free<br />

NRT services and follow-up counseling offered by a Quit Line.<br />

Additional localized programs services promoted by state tobacco control programs include:<br />

• Vermont’s “Ready, Set… STOP” program, which supports a network of counselors in every<br />

hospital in the state who coordinate and provide services at the local level, collaborating<br />

with community partners, employers, and providers to promote services and administering<br />

the QuitBucks program, which offers free or reduced price nicotine replacement therapy<br />

(NRT) to those in counseling. NRT is also shipped from the Quit Line to clients enrolled in<br />

16

Medicare and Ladies first (a woman’s health program) and to uninsured Vermonters (State<br />

of Vermont, 2006).<br />

• Utah’s Ending Nicotine Dependence (END) program has served over 1,000 youth cited by<br />

Utah courts for tobacco possession to help them quit. Most participants liked the END class<br />

and would recommend it to friends who use tobacco (Utah Department of <strong>Health</strong>, 2006).<br />

• New Jersey’s “Quitcenters”, 15 clinics at locations throughout the state that offer face-toface<br />

counseling on a sliding-scale fee based on income (New Jersey Comprehensive<br />

Tobacco Control Program, 2001).<br />

• New York’s 19 Cessation Centers, established in late 2004 to increase the screening and<br />

counseling of tobacco users by health care providers. These centers are working with 187<br />

health care provider organizations and are targeting larger organizations because of their size<br />

and reach and will use those relationships to facilitate future outreach to affiliated clinics and<br />

medical practices. Cessation Centers advocate for policy change with provider<br />

organizations, provide training to providers, and provide technical assistance.<br />

Collaborations with provider organizations and activities have increased over time. Best<br />

practices identified by the Cessation Centers for provider trainings were: provide training<br />

on-site, provide incentives such as lunch, coordinate training with already scheduled<br />

meetings, offer CME credits. In addition, providing mini-grants to targeted health care<br />

providers appears to facilitate systems-level changes. Barriers were competing priorities,<br />

financial barriers, and perceptions that existing systems sufficiently address cessation (RTI,<br />

2006).<br />

Use of cessation centers like those in New York to train providers to provide better smoking<br />

cessation services, including motivational interviewing techniques may be another useful<br />

intervention, complementing a Quit Line. However, follow-up trainings may need to be<br />

organized to yield the full benefits of this type of intervention and, in some cases, competing<br />

priorities will make it difficult for changes to be sustained (Velasquez et al., 2000). Working<br />

with hospitals may be another opportunity, which is often missed currently. When patients are<br />

hospitalized, this may be an opportune time to initiate smoking cessation interventions to<br />

increase quit rates (Polednak, 2000).<br />

Financial incentives, NRT, and competitions may also prompt smokers to quit. In New York<br />

State, local tobacco coalitions partnered with the Roswell Park Cancer Institute to administer 11<br />

“Quit and Win” competitions between November 2001 and March 2004. These competitions<br />

were intended to motivate smokers to initiate quit attempts and provide incentives for abstinence<br />

(e.g., cash prizes via a lottery) in the weeks immediately following the quit date when relapse is<br />

likely. Across all eleven contests, 87-93% of participants reported actually making a quit<br />

attempt and the average quit rate after one month was 21-49%. By comparison the average quit<br />

rate across all New Yorkers was 21.5%. For 8 of the 11 programs, participants had a<br />

significantly higher rate of quitting than the general population. Costs per attributable quit<br />

ranged from $301 to $953 and were not related to market size (O’Connor et al., 2006). A survey<br />

of adult smokers in Erie and Niagara Counties found that the offer of free nicotine patches/gum<br />

17

or cash incentives were interventions that would be most likely to convince smokers to stop<br />

smoking (Giardina et al., 2004).<br />

Physician Education Efforts<br />

The <strong>Agency</strong> for <strong>Health</strong> Care Policy and <strong>Research</strong> (AHCPR) has found that brief advice by<br />

medical providers is effective, although less effective than intensive individual, group, and<br />

telephone counseling interventions. FDA-approved pharmacotherapy can be effective,<br />

particularly when combined with counseling.<br />

The CDC recommends that statewide tobacco treatment include the following elements:<br />

• Population-based counseling and treatment programs, such as cessation helplines<br />

• Systemic changes that incorporate the AHCPR-sponsored cessation guideline<br />

• Coverage for treatment for tobacco use under public and private insurance<br />

• Elimination of cost barriers to treatment for underserved populations, particularly the<br />

uninsured<br />

The Community Guide’s Tobacco <strong>Review</strong> website (CDC, 2006) summarizes the results of 39<br />

measurements, taken from 20 studies on the use of provider reminders prompting providers to<br />

ask patients about their smoking status, and found that, although none were found to increase<br />

provider knowledge, 15 resulted in the provider offering cessation advice, 7 resulted in patient<br />

cessation attempts and 14 of the 39 measurements resulted in the cessation of patient smoking.<br />

18

ENFORCEMENT<br />

Both local entities and state governments benefit when states provide assistance to local<br />

governments in enforcement with respect to secondhand smoke and use of tobacco by minors.<br />

Most local governments do not have the resources or expertise in legal and enforcement issues<br />

pertaining to tobacco control strategies, and most state-level lack knowledge of community<br />

accessibility. It therefore is helpful to develop state-wide resources that can be accessed by local<br />

governments and community groups for legal issues associated with enforcement of policies.<br />

In California, the Technical Assistance Legal Center (TALC) is a statewide project which<br />

provides legal technical assistance to California cities and counties that have questions relating to<br />

tobacco control policies and strategies. TALC conducts legal research and develops print<br />

resources – including model ordinances – and provides technical assistance on legal strategies to<br />

reduce tobacco use, including preventing tobacco sponsorship, limiting youth access to tobacco,<br />

regulating tobacco retailers, expanding secondhand smoke protections, etc. TALC’s legal staff<br />

are lawyers with experience in public health, policy development, and municipal government.<br />

TALC works on legal issues that are almost always generated by the community. Rather than<br />

telling advocates or municipal legislators which issues to work on, TALC assists them in<br />

developing the strongest and most defensible policy possible to achieve their goals. TALC<br />

responds to approximately 750 requests for assistance each year. TALC employs a “train the<br />

trainers” approach to educating community advocates, communicates with public officials via<br />

written and oral presentations, and participates in statewide workgroups. TALC has been able to<br />

work with local agencies because California’s tobacco control infrastructure enables this type of<br />

collaboration. Without community-based agencies involved in the issue formally, TALC would<br />

have had to work only at the state level (California Department of <strong>Health</strong> Services, 2002).<br />

Similarly, Massachusetts has traditionally offered legal assistance to local entities through its<br />

Community Assistance Statewide Team to help them create and enforce smoke-free laws (Koh et<br />

al., 2005).<br />

States generally will benefit if they can get local entities interested in working on enforcement<br />

and policy development; however, providing some resources to help local groups conduct their<br />

work will multiply their effectiveness.<br />

Smokefree Policies<br />

In general, there have been very low rates of infraction with secondhand smoke policies in most<br />

industries. For example, a study of bars in Los Angeles County after the 1998 smoke-free law<br />

passed showed that compliance with the law – initially at 45.7% -- climbed to 75.8% by 2002<br />

(Weber et al., 2003). One month after the New York state smoke-free law went into effect, the<br />

proportion of smoke-free restaurants, bars, and bowling alleys in the state climbed from 31 to 93<br />

percent (New York State Department of <strong>Health</strong>, 2004). A preliminary assessment after the<br />

Massachusetts statewide indoor air act came into effect found that 3.7% (n=1) of establishments<br />

assessed had smoking in them. In this one establishment, there was only one smoker who put<br />

out his cigarette when a peer asked him to (Connoly et. al, 2005). In Vermont, the Department<br />

19

of <strong>Health</strong> is the lead agency for enforcement of the Clean Indoor Air Act, handling complaints<br />

and sending out a Food and Lodging sanitarian to investigate, sometimes in coordination with<br />

the Department of Liquor Control. The Department of <strong>Health</strong> has generally obtained voluntary<br />

compliance through owner education and large fines for noncompliance (State of Vermont,<br />

2006).<br />

According to the 2006 Surgeon General’s Report, public education and public debate before the<br />

adoption of the law, as well as in the period leading up to its implementation, can help<br />

jurisdictions achieve high levels of compliance with the law. To be effective, the law also needs<br />

to designate an appropriate enforcement agency and establish a public complaint mechanism and<br />

make complaints received the driving force for enforcement (Jacobson and Wasserman, 1999).<br />

Using local or community officials to help enforce tobacco control policies enhances their<br />

efficacy both by deterring violations and by sending a message to the public that community<br />

leadership supports the policy (Erikson, 2000).<br />

BREATH, the California Smoke-free Bar Project, a statewide project of the American Lung<br />

Association of Contra Costa and Solano Counties was initiated to ease the transition to the new<br />

law for business owners, to activate public support for the law, and to defeat tobacco industry<br />

efforts to undermine the law. As described by Kiser and Boschert (2001) BREATH included just<br />

four full-time and one part-time staff members assigned to work with the county and local health<br />

departments, the regions, ethnic networks, voluntary health groups, and various tobacco control<br />

grantees throughout California. Some of the main activities they conducted, using local and<br />

community resources included: working with local health departments to help ease the transition<br />

to the new law; activating support for the law; developing a network of local experts to work<br />

with on enforcement actions; and working with lobbyists for voluntary health organizations to<br />

defeat attempts to undermine the law. The use of powerful community members to tell public<br />

officials that they support smoke-free laws was an essential component of BREATH’s strategy.<br />

In addition, grassroots organizing through voluntary health organizations (for heart disease, lung<br />

disease, and cancer) proved to be indispensable in providing financial help and volunteer<br />

advocates (Kiser and Boschert, 2001).<br />

<strong>Local</strong> Lead Agencies (LLAs) in California played an important role in enforcement of the<br />

Smoke-free law, developing local interventions based on local needs, including ethnic make-up<br />

and language challenges. Using local officials helped because they were less visible to those<br />

who opposed the law at a state level (Magzamen and Glanz, 2001). Grants were awarded to law<br />

enforcement agencies at the local level to help fund these activities (Tobacco Education and<br />

<strong>Research</strong> Oversight Committee, 2003). Activities included helping smooth the transition to the<br />

new law and enforcement. For example, LLAs in Shasta and Riverside Counties hired law<br />

enforcement officers or health educators to cite noncompliant bars throughout the country,<br />

writing citations and educating local judges and court commissions. LLA members in San<br />

Mateo County rode along with city police officers to witness citations of bars (California<br />

Department of <strong>Health</strong> Services, 2001). Regional organizations also played a role in enforcement,<br />

and the four Ethnic Tobacco Education Networks of the California Tobacco Control Program<br />

have provided ethnic-specific technical assistance and training. The smoke-free workplace law<br />

was implemented with equal fidelity in small and large workplaces (Green et al., 2006).<br />

20

Broadening Protection from Environmental Tobacco Smoke<br />

The states discussed in this report have all enacted smokefree legislation at the state level,<br />

usually affecting workplaces, restaurants, and bars. Many states have continued their work on<br />

environmental tobacco smoke, addressing smoke in homes, cars, and other public places. Most<br />

of this work has been done in collaboration with local governments or community groups.<br />

Some local public housing authorities and municipalities in California have adopted nonsmoking<br />

policies in at least some sections of publicly-funded housing complexes for nonsmokers,<br />

including Los Angeles, San Francisco, Santa Barbara, San Luis Obispo, Madera, Belmont,<br />

Sebastopol, and Thousand Oaks (Toward a Tobacco-Free California, 2006). Smiliarly, Utah’s<br />

Tobacco Control Program educates local municipalities and multi-unit housing owners and<br />

tenants about policies that protect users of recreation venues and tenants about secondhand<br />

smoke (Utah Department of <strong>Health</strong>, 2006).<br />

A variety of local jurisdictions in Utah have also been active in banning smoking in countyowned<br />

vehicles, in city parks, in assisted living facilities, at fairs and festivals, in playgrounds,<br />

and on sports fields (Utah Department of <strong>Health</strong>, 2006). <strong>Local</strong> jurisdictions in California have<br />

continued to enact ordinances to protect the public from smoke, including outdoor tobacco<br />

smoke at beaches and parks, in shared spaces of multi-unit housing, in front of entryways to<br />

private buildings open to the public, and at public events such as fairs and festivals. San Luis<br />

Obispo also passed an ordinance to protect foster children, prohibiting foster parents from<br />

allowing children in their care to smoke, prohibiting smoking in cars during and prior to<br />

transporting foster children, and prohibiting smoking within 20 feet of children in foster care. In<br />

addition, the Campuses Organized and United for Good <strong>Health</strong> (COUGH) campaign continued<br />

its work to strengthen anti-smoking policies on the 23 campuses of the California State<br />

University and has expanded to the University of California and community college systems<br />

(Toward a Tobacco-Free California, 2006).<br />

On a voluntary basis, the State of Vermont has also conducted a “Take it Outside” campaign to<br />

encourage smoke-free policies in homes and cars for parents and caregivers (State of Vermont,<br />

2006) New York set a goal to increase the percentage of adults and youth who live in<br />

households where smoking is prohibited and ride in vehicles where smoking is prohibited. This<br />

effort has been lead by Community Partners throughout NY state. They have used two broad<br />

strategies: 1) paid media (including television, radio, billboard, print ads, website ads, and mass<br />

mailings) and 2) community education (including information dissemination at community<br />

events, planning and implementing smoke-free pledge campaigns, and identifying partners and<br />

collaborators to gain access to targeted groups). Several partners worked through health care<br />

providers or used materials from the US EPA. Others advocated with landlords and realtors<br />

about smoke-free dwelling policies. Community Partners reported struggling with designing and<br />

distributing materials and questioned the value of community education efforts. Data on trends<br />

in smoke-free homes and cars showed that the efforts were not effective, indicating that either<br />

the strategies have been ineffective or have not been sufficiently coordinated across the state.<br />

The evaluators of this program suggested that community activities are less effective in<br />

21

promoting home activities than paid media, indicating that a state-led effort would be more<br />

effective than an effort led by the Community Partners (RTI International, 2006).<br />

Youth Access Restrictions<br />

Combined with mass media and educational programs, the restriction of tobacco sales to youth<br />

may be an additional deterrent to initiation of smoking. This can be accomplished through the<br />

passage of laws at the federal, state, or local level preventing sales to people under a certain age.<br />