click here to download - Voice Male Magazine

click here to download - Voice Male Magazine

click here to download - Voice Male Magazine

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

By Rob Okun<br />

FROM THE EDITOR<br />

Finding Light in the<br />

Heart of Darkness<br />

Last fall I spent close <strong>to</strong> a week at<br />

Auschwitz, the death camp. It’s a place<br />

w<strong>here</strong> hearts ache and break, w<strong>here</strong><br />

the shadow side of human nature sought <strong>to</strong><br />

overwhelm the light by eclipsing every bit of<br />

what’s good and whole and radiant in our lives.<br />

What I found, though, was even that place—at<br />

the heart of darkness—couldn’t extinguish the<br />

light. I felt enlivened being t<strong>here</strong>, in no small<br />

part because I was in a community of more<br />

than 80 people from a dozen countries who had<br />

come <strong>to</strong> bear witness <strong>to</strong> what happened seven<br />

decades ago.<br />

Each morning we would walk from the<br />

Center for Dialogue and Prayer <strong>to</strong> Birkenau,<br />

the neighboring camp—22 times larger than<br />

Auschwitz—less than two miles away. We<br />

would sit in silence beside the railroad tracks<br />

w<strong>here</strong> cattle cars bearing men, women, and<br />

children screeched <strong>to</strong> a s<strong>to</strong>p at the “selection”<br />

site w<strong>here</strong> the healthy and young were forced<br />

in<strong>to</strong> barracks <strong>to</strong> become slave laborers and<br />

everyone else was herded <strong>to</strong> the “showers”—<br />

the gas chambers—<strong>to</strong> be fatally poisoned.<br />

We meditated on violence, on cruelty,<br />

on inhumanity. We meditated on peace, on<br />

kindness, on compassion. Away from our day<strong>to</strong>-day<br />

lives, we meditated, <strong>to</strong>o, on the contradictions<br />

of being human—from our murderous<br />

rage <strong>to</strong> our heroic selflessness. Is it really our<br />

nature <strong>to</strong> swing so wildly on the pendulum<br />

of human behavior? Certainly the politics<br />

and psychology of fascism lay at the root of<br />

what happened in Nazi Germany: The few<br />

had invaded the hearts and minds of the many,<br />

poisoning them, sending their frozen hearts in<strong>to</strong><br />

spiritual and political hibernation.<br />

In our group of 80 were a Palestinian imam,<br />

an Israeli rabbi, pas<strong>to</strong>rs, priests (Catholic<br />

and Zen), therapists, ac<strong>to</strong>rs, writers, lawyers,<br />

doc<strong>to</strong>rs, meditation teachers, business people,<br />

filmmakers, and students. I felt enriched by the<br />

voices and spirit of the young, 16 in all, high<br />

school and college age, brimming with open<br />

hearts and exercising quick, keen minds.<br />

Twice each day, some moments after we<br />

began another round of sitting in silence, four<br />

people would stand at the four points of our<br />

circle. Each held a typed sheet of paper covered<br />

with single-spaced names of those who had<br />

been murdered. Often the same surname was<br />

in<strong>to</strong>ned, person after person, age 47, or 36, or<br />

23. (Among the several thousand names we read<br />

that week none was younger than 16 or older<br />

than their 50s; the Nazis kept no records of the<br />

<br />

<strong>Voice</strong> <strong>Male</strong><br />

old and the young who they immediately gassed<br />

at the camps.)<br />

Beneath a gray November sky some would<br />

chant the names—they were praying. Others<br />

seemed <strong>to</strong> be working hard just <strong>to</strong> maintain<br />

control, just <strong>to</strong> be able <strong>to</strong> get through the recitation.<br />

It was the hardest part of each day for me.<br />

I found myself rocking back and forth, choking<br />

back a moan, picking up pebbles and flicking<br />

them down as if I was adding exclamation<br />

points proclaiming each of these people’s lives<br />

mattered. Goldberg, Avram! Goldberg, Sara!<br />

In the afternoons, we would walk in<strong>to</strong><br />

the dank, dark barracks—virtually un<strong>to</strong>uched<br />

since the Nazis left in January 1945—and light<br />

candles before reciting the Kaddish (the Jewish<br />

prayer for the dead) in Polish, English, Dutch,<br />

Hebrew and German. Often we would sing.<br />

Rabbi Ohad played guitar, leading us in songs of<br />

hope and healing. Whatever notion anyone had<br />

that singing at Auschwitz-Birkenau was disrespectful<br />

dissipated as our voices rose inside the<br />

barracks of death, and drifted skyward, a balm <strong>to</strong><br />

those whose spirits still hover above that place.<br />

At dusk on the last day of the retreat, we<br />

gat<strong>here</strong>d at the pond w<strong>here</strong> the ashes of the<br />

dead were dumped, delivered t<strong>here</strong> from the<br />

crema<strong>to</strong>rium in whose shadow we s<strong>to</strong>od. At<br />

the edge of the pond a stand of tall trees, many<br />

dating back <strong>to</strong> those dark days, still bore silent<br />

witness <strong>to</strong> the atrocities. We ringed the pond with<br />

candles and, standing behind the tapers, some<br />

s<strong>to</strong>od silent, some cried, and some sang: “We are<br />

rising, like a phoenix from the ashes, brothers<br />

and sisters spread your wings and fly high,” we<br />

chanted through our tears. “We are ri-i-sing, we<br />

are ri-i-sing.”<br />

A few days after I returned home I was<br />

a guest speaker in a first-year high school<br />

class that had just finished reading Eli Wiesel’s<br />

memoir, Night, about his horrific imprisonment<br />

at Auschwitz. Before we started talking,<br />

I wanted the students <strong>to</strong> have as a reference<br />

point this simple truth: understanding his<strong>to</strong>ry is<br />

key <strong>to</strong> understanding current events. So I wrote<br />

on the blackboard these words from the Czech<br />

writer turned political figure Václav Havel: “The<br />

struggle against oppression,” he said, “is the<br />

struggle of remembering against forgetting.”<br />

As I shared these words—and utter them<br />

<strong>to</strong> myself still—I am left with the questions of<br />

how <strong>to</strong> remember and how <strong>to</strong> best face the world<br />

I live in now.<br />

<strong>Voice</strong> <strong>Male</strong> edi<strong>to</strong>r Rob Okun can be reached at<br />

rob@voicemalemagazine.org.<br />

Rob Okun

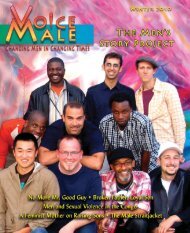

Winter 2011<br />

Volume 14 No. 52<br />

Changing Men in Changing Times<br />

www.voicemalemagazine.org<br />

8<br />

Features<br />

8<br />

12<br />

14<br />

16<br />

19<br />

22<br />

28<br />

John Lennon on Manhood, Fatherhood and Feminism<br />

By Jackson Katz<br />

Flying My Freak Flag at Half-mast<br />

By Michael A. Messner<br />

10 Things Men & Boys Can Do <strong>to</strong> S<strong>to</strong>p Human Trafficking<br />

By Jewel Woods<br />

Women Can Say No…and Yes<br />

By Michael Kimmel<br />

Real Men Know How <strong>to</strong> Take Paternity Leave<br />

By Allison Stevens<br />

It’s Not Just a Game<br />

An interview with filmmaker Jeremy Earp by Jackson Katz<br />

Coming Home <strong>to</strong> Pinsk<br />

By Rob Okun<br />

16<br />

Columns & Opinion<br />

19<br />

2<br />

4<br />

5<br />

7<br />

10<br />

20<br />

21<br />

From the Edi<strong>to</strong>r<br />

Letters<br />

Men @ Work<br />

Men & Nonviolence<br />

OutLines<br />

Poem<br />

Men Overcoming Violence<br />

Finding the Peacemaker Within By Jan Passion<br />

Gay Bashing Is About Masculinity By Michael Kimmel<br />

Tucson Lament<br />

W<strong>here</strong> Men Stand in Overcoming Violence Against Women<br />

By Michael Flood<br />

25<br />

27<br />

Men & Sports<br />

ColorLines<br />

In the NFL, Violence Comes <strong>to</strong> a Head By Dave Zirin<br />

Erotic Revolutionaries An Interview with Shayne Lee By Ebony Utley<br />

27<br />

32<br />

Resources<br />

ON THE COVER:<br />

Pete Salou<strong>to</strong>s Pho<strong>to</strong>graphy<br />

male positive • pro-feminist • open-minded<br />

Winter 2011

Mail Bonding<br />

<br />

Rob A. Okun<br />

Edi<strong>to</strong>r<br />

Lahri Bond<br />

Art Direc<strong>to</strong>r<br />

Michael Burke<br />

Copy Edi<strong>to</strong>r<br />

Read Predmore<br />

Circulation Coordina<strong>to</strong>r<br />

Azad Abbasi, Zach Bernard, Michael Wei<br />

Interns<br />

National Advisory Board<br />

Juan Carlos Areán<br />

Family Violence Prevention Fund<br />

John Badalament<br />

The Modern Dad<br />

Eve Ensler<br />

V-Day<br />

Byron Hurt<br />

God Bless the Child Productions<br />

Robert Jensen<br />

Prof. of Journalism Univ. of Texas<br />

Sut Jhally<br />

Media Education Foundation<br />

Bill T. Jones<br />

Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Co.<br />

Jackson Katz<br />

Men<strong>to</strong>rs in Violence Prevention Strategies<br />

Michael Kaufman<br />

White Ribbon Campaign<br />

Joe Kelly<br />

The Dad Man<br />

Michael Kimmel<br />

Prof. of Sociology SUNY S<strong>to</strong>ny Brook<br />

Charles Knight<br />

Other & Beyond Real Men<br />

Don McPherson<br />

Men<strong>to</strong>rs in Violence Prevention<br />

Mike Messner<br />

Prof. of Sociology Univ. of So. California<br />

Craig Norberg-Bohm<br />

Men’s Initiative for Jane Doe<br />

Chris Rabb<br />

Afro-Netizen<br />

Haji Shearer<br />

Massachusetts Children’s Trust Fund<br />

Shira Tarrant<br />

Prof. of Gender Studies,<br />

California State Long Beach<br />

<strong>Voice</strong> <strong>Male</strong><br />

Initiating Our Boys<br />

Thank you for bringing <strong>to</strong> light the<br />

possibility of modern day initiation for<br />

teenage boys (Philip Snyder’s “How Can<br />

Boys Come of Age in Today’s World?”<br />

<strong>Voice</strong> <strong>Male</strong>, Fall 2010).<br />

I believe Initiation<br />

is a missing<br />

link in the health<br />

of our society.<br />

The West African<br />

saying goes “If<br />

we don’t initiate<br />

our boys, they<br />

will burn down<br />

the village.”<br />

G a n g s ,<br />

v a n d a l i s m ,<br />

violence, alcohol<br />

and drug addiction,<br />

disrespect<br />

and abuse of<br />

women, despair<br />

and suicide are<br />

all fires we need<br />

<strong>to</strong> put out. As<br />

men, knowing who we are and w<strong>here</strong> we fit<br />

are keys <strong>to</strong> a positive and fulfilling life. Initiations<br />

begin this process. I believe we men<br />

have an obligation <strong>to</strong> our boys and <strong>to</strong> future<br />

generations. Mature men and elders are in<br />

our communities willing and ready <strong>to</strong> serve<br />

this process. They just don’t know w<strong>here</strong> <strong>to</strong><br />

start. We need <strong>to</strong> build a societal structure <strong>to</strong><br />

initiate and men<strong>to</strong>r all our boys. Our society<br />

needs it, our boys deserve it.<br />

Sam Rodgers<br />

Boys <strong>to</strong> Men Men<strong>to</strong>ring Network<br />

Western Mass. & Southern Vermont<br />

Leverett, Mass.<br />

Men Help Honor Friedan<br />

<strong>Voice</strong> <strong>Male</strong> readers may be interested<br />

<strong>to</strong> know that NOMAS, (the National<br />

Organization for Men Against Sexism), has<br />

helped <strong>to</strong> fund a his<strong>to</strong>rical marker <strong>to</strong> honor<br />

Betty Friedan and the ground-breaking<br />

influence of her book, The<br />

Feminine Mystique, which<br />

helped <strong>to</strong> create massive<br />

support among women for<br />

the women’s movement in<br />

the 1960s.<br />

In response <strong>to</strong> Veteran<br />

Feminists of America,<br />

which is seeking support <strong>to</strong><br />

place a plaque at Friedan’s<br />

birthplace in Nyack, N.Y.,<br />

NOMAS donated about<br />

60 percent of the cost of<br />

this endeavor. I find it<br />

impressive and noteworthy<br />

that an organization of<br />

primarily men helped <strong>to</strong><br />

make this happen, and I<br />

share this <strong>to</strong> let you know<br />

of the ethics, service and<br />

commitment of NOMAS. We have a good<br />

ally and partner in this organization.<br />

Please consider checking out the<br />

NOMAS web page—www.nomas.org—<br />

w<strong>here</strong> you can learn about a conference they<br />

are sponsoring in Tallahassee in April.<br />

Rose Garrity<br />

Owego, N.Y.<br />

Letters may be sent via email <strong>to</strong><br />

www.voicemalemagazine.org<br />

or mailed <strong>to</strong> Edi<strong>to</strong>rs: <strong>Voice</strong> <strong>Male</strong>,<br />

33 Gray Street, Amherst, MA 01002.<br />

VOICE MALE is published quarterly by the Alliance for Changing Men, an affiliate of Family<br />

Diversity Projects, 33 Gray St., Amherst, MA 01002. It is mailed <strong>to</strong> subscribers in the U.S., Canada,<br />

and overseas and is distributed at select locations around the country and <strong>to</strong> conferences, universities,<br />

colleges and secondary schools, and among non-profit and non-governmental organizations. The<br />

opinions expressed in <strong>Voice</strong> <strong>Male</strong> are those of its writers and do not necessarily reflect the views of<br />

the advisors or staff of the magazine, or its sponsor, Family Diversity Projects. Copyright © 2011<br />

Alliance for Changing Men/<strong>Voice</strong> <strong>Male</strong> magazine.<br />

Subscriptions: 4 issues-$24. 8 issues-$40. Institutions: $35 and $50. For bulk orders, go <strong>to</strong><br />

voicemalemagazine.org or call <strong>Voice</strong> <strong>Male</strong> at 413.687-8171.<br />

Advertising: For advertising rates and deadlines, go <strong>to</strong> voicemalemagazine.org or call at <strong>Voice</strong><br />

<strong>Male</strong> 413.687-8171.<br />

Submissions: The edi<strong>to</strong>rs welcome letters, articles, news items, reviews, s<strong>to</strong>ry ideas and queries, and<br />

information about events of interest. Unsolicited manuscripts are welcomed but the edi<strong>to</strong>rs cannot<br />

be responsible for their loss or return. Manuscripts and queries may be sent via email <strong>to</strong> www.voicemalemagazine.org<br />

or mailed <strong>to</strong> Edi<strong>to</strong>rs: <strong>Voice</strong> <strong>Male</strong>, 33 Gray St., Amherst, MA 01002.

Men @ Work<br />

Gender and Climate<br />

Concerned about the persistent<br />

exclusion of women’s rights and<br />

gender issues in climate debates, the<br />

Women’s Environment and Development<br />

Organization (WEDO) created<br />

an NGO-United Nations alliance in<br />

2005 as a unified front <strong>to</strong> address<br />

gender and climate change. It is a<br />

project of the Global Gender and<br />

Climate Alliance (GGCA), a unique<br />

network of 13 UN agencies and<br />

more than two dozen civil society<br />

organizations working <strong>to</strong>gether <strong>to</strong><br />

ensure that climate change decisionmaking,<br />

policies and initiatives, at<br />

all levels, are gender responsive.<br />

Since its founding, WEDO has<br />

played a leadership role in facilitating<br />

global and national policy advocacy,<br />

capacity building and knowledge<br />

generation, in partnership and<br />

collaboration with various members<br />

under the GGCA umbrella.<br />

The project was successful<br />

in seeing that eight strong references<br />

<strong>to</strong> women and gender, and<br />

new gender language was included<br />

in the December 2010 Cancun<br />

Agreements. Key partners in advocacy<br />

work include ENERGIA<br />

– the International Network on<br />

Gender and Sustainable Energy,<br />

Abantu for Development in Ghana,<br />

Oxfam International, CARE,<br />

ActionAid, UNIFEM (now part of<br />

UNWOMEN), among others.<br />

WEDO works with members of<br />

the alliance <strong>to</strong> lobby governments<br />

and build GGCA’s membership<br />

of organizations working <strong>to</strong>ward<br />

gender-sensitive international<br />

climate change agreements and<br />

plans. For more information, visit<br />

the GGCA website, www.genderclimate.org/.<br />

[Men @ Work continued on page 6]<br />

A Call <strong>to</strong> Take on The Gender Byline Gap know why. As only a child with a fierce, idealistic sense of right and<br />

wrong can be, I tried <strong>to</strong> resist these messages without knowing what<br />

In 2011, male writers still dominate the public discourse and have<br />

was really going on. But not very successfully. What I knew in my heart<br />

a much higher percentage of bylines in most corporate magazines<br />

then was that my cousin was a better student than I, and much more<br />

online and off, even in progressive media. In January Ms. <strong>Magazine</strong><br />

talented as an artist, a dancer, and in other ways. But <strong>to</strong> people around<br />

(msmagazine.com) started a campaign against the New Yorker after the<br />

us, my development—as the boy—seemed <strong>to</strong> be more important. This<br />

magazine went two issues with only two or three contributions by female<br />

pattern continued through high school and after. My uncle would give<br />

writers, that in a close <strong>to</strong> 150-page magazine. It’s not just the New Yorker.<br />

my father cigars when I scored <strong>to</strong>uchdowns<br />

January’s issue of Harpers had only three<br />

during high school football games, while my<br />

out of 21 s<strong>to</strong>ries by women. The Nation’s<br />

cousin would cheerlead in semi-obscurity. In<br />

latest print issue has four and a half female<br />

student government, I was the president and<br />

bylines out of 17 articles. The Atlantic did a<br />

she the secretary. . .<br />

little better, featuring five and a half female<br />

“Over the years it finally dawned on me<br />

bylines, of 18 <strong>to</strong>tal s<strong>to</strong>ries.<br />

why I was frustrated. I was being unfairly<br />

“Publications as prominent as the New<br />

deprived—deprived of the talents, the ideas,<br />

Yorker need <strong>to</strong> know they can’t get away<br />

the perspective of half of society. Often it was<br />

with gender inequity in bylines,” said<br />

a point of view I very much wanted. Women’s<br />

Jessica Stite, online edi<strong>to</strong>r at Ms. “This<br />

voices and writing provided a balance <strong>to</strong><br />

isn’t one of those examples of insidious,<br />

the macho orientation most successful boy<br />

difficult-<strong>to</strong>-measure sexism. They will get<br />

A meeting of concerned women writers at AlterNet. students and athletes received when I was<br />

caught by anyone who can count!” Ms.<br />

growing up in America.<br />

senior edi<strong>to</strong>r Michele Kort <strong>to</strong>ld the progressive media website AlterNet<br />

“When I came of age in the early seventies I discovered amazing<br />

(www.alternet.org) that although the New Yorker has showcased many<br />

women writers—authors of sprawling, multi-layered novels like Marge<br />

talented female writers over the years, it needs <strong>to</strong> do way better <strong>to</strong> ensure<br />

Piercy and Sara Davidson. I was introduced <strong>to</strong> the work of brilliant<br />

equal representation on a regular basis. “The New Yorker can only offer a<br />

thinkers like Dorothy Dinnerstein, Germaine Greer, and Shulamuth<br />

richer perspective on the world if it includes more women’s voices.”<br />

Fires<strong>to</strong>ne, whose ideas and social critiques made infinite sense <strong>to</strong> me,<br />

Meanwhile, The Harnisch Foundation offered a $15,000 challenge<br />

more so than many of the male thinkers did at that point.”<br />

grant <strong>to</strong> AlterNet for its Gender Byline Project if it matches that amount<br />

Hazen said women writers’ ideas helped <strong>to</strong> “shape me. They’ve<br />

from its readers, especially those on Facebook. All of the money in this<br />

been fundamental <strong>to</strong> who I am and what I value. So that is why I think<br />

project would pay for content written by women, said executive edi<strong>to</strong>r<br />

battling the gender byline gap—and it still is severe, we have <strong>to</strong>ns of<br />

Don Hazen in an appeal <strong>to</strong> readers.<br />

data <strong>to</strong> support it—is a key part of every issue we care about, and<br />

Why is gender byline fairness important <strong>to</strong> Hazen? “I became a<br />

a linchpin <strong>to</strong> our future success in creating the society we want. It’s<br />

‘feminist,’ or let’s say I had my ‘consciousness raised,’ as a young child,<br />

important for men <strong>to</strong> get on board, because currently we are being<br />

although I didn’t quite know what that was at the time. I think I was<br />

deprived.”<br />

seven. My female cousin was the same age as I, and almost a sibling<br />

To learn more, in addition <strong>to</strong> AlterNet and Ms., visit the OpEd<br />

since our families spent a lot of time <strong>to</strong>gether. As we grew, I started<br />

Project (www.opedproject.org), an initiative <strong>to</strong> expand public debate,<br />

getting messages about how I was supposed <strong>to</strong> act around her: protect<br />

emphasizing enlarging the pool of women experts who are accessing<br />

her, open the door for her, walk on the outside closer <strong>to</strong> the street. And<br />

(and accessible <strong>to</strong>) key print and online forums.<br />

t<strong>here</strong> were other, more subtle messages that made me angry, but I didn’t<br />

www.alternet.org<br />

Winter 2011

Men @ Work<br />

Men Sitting on New<br />

Energy Source?<br />

Could men be literally sitting<br />

on a renewable energy source <strong>to</strong><br />

ease the nation’s dependence on<br />

oil? Researchers at the National<br />

Institute of Diabetes and Digestive<br />

and Kidney Diseases say the average<br />

man passes gas 14 <strong>to</strong> 23 times a day,<br />

producing up <strong>to</strong> a quart of untapped<br />

energy. “Many people think their<br />

own output is excessive,” according<br />

<strong>to</strong> William Chey, M.D., in a recent<br />

Men’s Health. A professor of internal<br />

medicine at the University of Michigan,<br />

Dr. Chey says, “it’s normal<br />

for men <strong>to</strong> produce between a pint<br />

and four pints of gas a day.” Such<br />

“backfires” are the body’s way of<br />

regulating the amount of air in your<br />

s<strong>to</strong>mach and the gas levels in your<br />

intestines. What if you try <strong>to</strong> stifle<br />

the urge <strong>to</strong> let it rip? You run the risk<br />

of abdominal cramping or s<strong>to</strong>mach<br />

rumbling, technically called borborygmi.<br />

Excess gassiness can result<br />

from a poor ability <strong>to</strong> process certain<br />

sugars, such as fruc<strong>to</strong>se and lac<strong>to</strong>se,<br />

or starchy carbs, including corn and<br />

wheat. With veggie oil-fueled cars<br />

on the rise, t<strong>here</strong> soon may be an<br />

answer <strong>to</strong> the burning question: Will<br />

t<strong>here</strong> finally be a good use for men’s<br />

hot air?<br />

Father Knows Best<br />

Among the oppressive patriarchal<br />

holdovers still in force in Saudi<br />

Arabia is a requirement that<br />

females obtain their father’s (or<br />

guardian’s) permission <strong>to</strong> marry—<br />

no exceptions. Consider: Despite<br />

being 42, and a surgeon licensed<br />

<strong>to</strong> practice in Canada and the U.K.<br />

as well as her native country, a<br />

female Saudi physician is viewed<br />

as subordinate <strong>to</strong> her father. It<br />

is estimated that more than three<br />

quarters of a million Saudi women<br />

are in the same position. Women<br />

New Documentary: Boys Becoming Men<br />

From the co-maker of<br />

the Academy Awardnominated<br />

Hoop Dreams<br />

will soon come Boys Become Men,<br />

a new two-hour documentary by<br />

filmmaker Frederick Marx. The<br />

documentary aims <strong>to</strong> dramatically<br />

demonstrate the urgent need “<strong>to</strong><br />

resurrect conscious initiation<br />

of teens in our times,” Marx<br />

says. Featuring families and<br />

rites of passage from different<br />

traditions—Native American,<br />

Christian, Jewish, Muslim, and<br />

secular—the film makes the<br />

point that “all traditions, old and<br />

new, have valuable, much needed<br />

initiations <strong>to</strong> offer young people.<br />

Having seen real-life teenage<br />

boys slay their personal dragons,<br />

having seen their adult men<strong>to</strong>rs<br />

tested but unfailing and true,”<br />

Marx believes both teen and<br />

adult audiences will witness the<br />

film’s closing celebrations “with<br />

a profound sense of hope that<br />

we can—and will—change our<br />

society through myriad forms of<br />

teen initiation and men<strong>to</strong>rship.<br />

Most documentaries only present<br />

social problems,” Marx says.<br />

“Boys Become Men will present<br />

Film direc<strong>to</strong>r Frederick Marx<br />

solutions.” The film complete<br />

a trilogy on urban teenage boys<br />

that, in addition <strong>to</strong> Hoop Dreams,<br />

included the earlier work, Boys <strong>to</strong><br />

Men. All express deep concerns<br />

about teen boys realizing a<br />

healthy and mature masculinity.<br />

Marx has worked in film and<br />

television for 35 years and his<br />

latest film, Journey from Zanskar,<br />

features the Dalai Lama with<br />

narration by Richard Gere. A<br />

successful online fundraising<br />

campaign raised $25,000 <strong>to</strong> help<br />

produce the film. To contribute,<br />

or <strong>to</strong> learn more, go <strong>to</strong> www.<br />

warriorfilms.org.<br />

“can’t even buy a phone without a<br />

guardian’s permission,” explained<br />

a women’s rights activist. As for<br />

the surgeon? She sued her father<br />

in court but no results had been<br />

reported at press time.<br />

A Manual on<br />

Masculinity<br />

A new manual Created in<br />

God’s Image: From Hegemony<br />

<strong>to</strong> Partnership, aimed at creating<br />

a positive masculinity, has been<br />

published by The World Communion<br />

of Reformed Churches. The manual<br />

seeks <strong>to</strong> break down images of<br />

masculinity that encourage men <strong>to</strong><br />

be dominant by providing positive<br />

examples of what masculinity<br />

can be. It includes studies of the<br />

Bible in the context of gender and<br />

sexuality, passages suggesting a<br />

liberation theology for men, and a<br />

series of modules meant <strong>to</strong> provide<br />

direction for Christian men and<br />

men’s groups seeking <strong>to</strong> embrace<br />

positive masculinity.<br />

“T<strong>here</strong> is violence <strong>to</strong>o within<br />

the church—in parishes and in<br />

church members’ homes,” said Setri<br />

Nyomi, general secretary of the<br />

World Communion of Reformed<br />

Churches (WCRC). “Yet <strong>to</strong>o often<br />

we turn a blind eye or are silent…”<br />

One activity in the manual<br />

asks men <strong>to</strong> make an inven<strong>to</strong>ry of<br />

their lives using the metaphor of a<br />

tree: the roots are one’s foundation<br />

(i.e. religious beliefs or family<br />

experiences); the trunk is the social<br />

structure within which one lives;<br />

the leaves are sources of strength<br />

and motivation.<br />

Ultimately, the manual seeks <strong>to</strong><br />

bolster men’s participation in the<br />

struggle against gender violence<br />

and helps <strong>to</strong> change gender relations<br />

which lead <strong>to</strong> that violence. For those<br />

engaged in faith-based communities<br />

drawing on the Christian tradition,<br />

the manual is an important addition<br />

<strong>to</strong> a social arena in need of more<br />

resources. To order a copy ($15)<br />

contact WCRC at wcrc.ch.<br />

Brother Keepers<br />

Brother Keepers: New<br />

Perspectives on Jewish Masculinity<br />

is an international book of<br />

new essays on Jewish men. A<br />

wide-ranging collection—from<br />

sociological surveys <strong>to</strong> confessional<br />

poetry—Brother Keepers offers<br />

a variety of perspectives on the<br />

journey from Abraham’s knives <strong>to</strong><br />

the flight of men from American<br />

Jewish life. It was edited by noted<br />

Jewish men and masculinity author<br />

Harry Brod, and Rabbi Shawn Zevit,<br />

who combines spiritual leadership<br />

with teaching and performing.<br />

“Like any good Jewish book,” says<br />

Jay Michaelson, executive direc<strong>to</strong>r<br />

of Nehirim, GLBT Jewish Culture<br />

and Spirituality, Brother Keepers<br />

“answers the questions it raises<br />

with more questions.”<br />

Essays address personal<br />

experience, gendered bodies, poetry<br />

and prayer, literature and film,<br />

illuminating how masculinities<br />

and Judaisms engage each other<br />

in gendered Jewishness. To order<br />

Brother Keepers ($25 paperback;<br />

$55 cloth; and $20 e-book), go<br />

<strong>to</strong> Men’s Studies Press at www.<br />

mensstudies.com.<br />

<br />

<strong>Voice</strong> <strong>Male</strong>

Men & Nonviolence<br />

Finding the Peacemaker Within<br />

By Jan Passion<br />

I<br />

was three years old when I<br />

watched the cops take my<br />

father. Before they arrived,<br />

I watched my parents fight over a<br />

gun. Their own guns drawn, the<br />

cops forced my dad in<strong>to</strong> a waiting<br />

squad car. I sat beside him in the<br />

police car, while my mother and<br />

brother rode in our car behind us. I<br />

think Dad was bleeding from a<br />

bullet that grazed him during the<br />

fight. Somehow, in all the trauma<br />

and chaos, it struck me — at the<br />

age of three — that this wasn’t<br />

right: More violence wasn’t the<br />

answer.<br />

Seven years later my father<br />

killed himself, and that wasn’t the<br />

answer, either. The legacy he left<br />

me is that violence is never the<br />

answer. But how else <strong>to</strong> protect<br />

oneself against violence, if not by<br />

violence?<br />

Thanks <strong>to</strong> my father, I set a course early in life <strong>to</strong> figure out an answer<br />

<strong>to</strong> that question. My searching would eventually lead me <strong>to</strong> Nonviolent<br />

Peaceforce (www.nonviolentpeaceforce.org).<br />

Before arriving at Nonviolent Peaceforce, I spent a decade working<br />

with perpetra<strong>to</strong>rs of domestic violence and their victims. I learned a lot<br />

about my father, working with men who acted just like him. I learned<br />

<strong>to</strong> more deeply understand the humanity of these men, who caused so<br />

much pain <strong>to</strong> their loved ones. I learned I could hate their actions without<br />

hating them.<br />

I learned that by listening <strong>to</strong> them, and by showing them that acting<br />

out violently was a choice, that by giving them a safe place <strong>to</strong> speak of<br />

their own injuries, and that by not taking sides against them, these men<br />

began <strong>to</strong> change. They changed not by force but of their own accord.<br />

They began <strong>to</strong> see the power of choosing nonviolence over violence.<br />

Slowly the seed of nonviolence began <strong>to</strong> grow, and the wall of violence<br />

they’d erected <strong>to</strong> protect themselves began <strong>to</strong> erode. As they stepped<br />

from the rubble of their violent pasts, just like me, these men began <strong>to</strong><br />

see solutions other than violence <strong>to</strong> protect their lives.<br />

The work of Nonviolent Peaceforce is a larger-scale version of my<br />

work in domestic violence. Both put mending lives and mending relationships<br />

first. Civilian protection is the number one mandate carried<br />

out by unarmed civilian peacekeepers, and we are rigorously trained <strong>to</strong><br />

respond nonviolently even when under extreme threat.<br />

I remember when one of our vehicles carrying three peacekeepers<br />

was surrounded by a group of violent young men. They smashed all<br />

the windows, hit the driver in the head and flashed a grenade under<br />

his face.<br />

Because this driver, a Kenyan peacekeeper, was able <strong>to</strong> respond<br />

nonviolently and was backed by his colleagues’ courage <strong>to</strong> remain calm,<br />

the situation de-escalated and the result was a meeting the next day.<br />

Once a dialogue opened, the attackers began <strong>to</strong> understand the mission<br />

of Nonviolent Peaceforce, and once they saw that we do not take sides,<br />

“The work of Nonviolent Peaceforce is a larger-scale version of my work<br />

in domestic violence.”<br />

they apologized for their violent<br />

outburst. The incident reminded me<br />

how tempting it is <strong>to</strong> write people<br />

off who commit violence. But if<br />

we have the courage <strong>to</strong> hold their<br />

humanity in our hearts even as<br />

we witness or are harmed by their<br />

acts, we can prepare the ground for<br />

nonviolent action and thus prepare<br />

the way <strong>to</strong> peace.<br />

I was <strong>to</strong> learn another lesson in<br />

courage from a 15-year-old child<br />

soldier. I never found out at what<br />

age she had been abducted. She<br />

came <strong>to</strong> us seeking help after she<br />

escaped her cap<strong>to</strong>rs and discovered<br />

that she was not safe at home in her<br />

own village with her family. This<br />

was in part because she had short<br />

hair, which marked her as a female<br />

fighter. Though she wanted more<br />

than anything <strong>to</strong> stay with her family,<br />

she knew she risked re-abduction and would face a severe penalty for<br />

desertion if retaken.<br />

We spent a day accompanying her <strong>to</strong> another part of the country w<strong>here</strong><br />

she would be safe, could escape the daily trauma of the life of a child<br />

soldier, and be able <strong>to</strong> grow her hair out. It was only one day out of the<br />

lives of the three of us accompanying her, but it made all the difference<br />

in her getting <strong>to</strong> keep hers. She was very quiet on the 10-hour journey,<br />

which involved passing through many military checkpoints. She had the<br />

stillness of terror about her. She did not make eye contact and answered<br />

our questions through the transla<strong>to</strong>r in monosyllables. But once we<br />

arrived at the safe place, her expression seemed <strong>to</strong> soften, and in her eyes<br />

I read the message, “I’m going <strong>to</strong> make it. I am safe.”<br />

This young woman is still in her teens <strong>to</strong>day, and when I think of her,<br />

I am reminded why the unarmed civilian peacekeepers of Nonviolent<br />

Peaceforce do what we do. We do our work for young girls taken as<br />

child soldiers. We do our work for young boys who hold grenades <strong>to</strong><br />

people’s faces. We do this work for ourselves. And some of us do it for<br />

our fathers.<br />

Jan Passion, a lifelong peace activist, spent 10 years as a<br />

psychotherapist working with perpetra<strong>to</strong>rs<br />

and victims of various forms of violence<br />

and trauma. Jan has been a peacebuilding<br />

trainer with The Conflict Transformation<br />

Across Cultures Program (CONTACT)—a<br />

member organization of Nonviolent<br />

Peaceforce—and worked at the Karuna<br />

Center for Peacebuilding and as a guest<br />

faculty with Lesley University in Israel. He<br />

can be reached at JPassion@NVPF.org.<br />

Winter 2011

John<br />

Lennon<br />

on<br />

Manhood,<br />

Fatherhood<br />

and Feminism<br />

By Jackson<br />

Katz<br />

Three decades after his murder in New York City, John Lennon’s hold on<br />

our cultural imagination is still strong. The subject of countless biographies,<br />

magazine articles, and documentaries, including a BBC special exploring his<br />

final days with the Beatles and the independent film Now<strong>here</strong> Boy delving<br />

in<strong>to</strong> his childhood and adolescence, this rock icon has been one of the most<br />

chronicled people of our times. So it was a surprise when Rolling S<strong>to</strong>ne<br />

magazine uncovered several hours of a taped interview by Jonathon Cott with<br />

Lennon just three days before his murder on December 8, 1980. While brief<br />

excerpts were published soon after his death, after Cott unearthed the original<br />

tapes a few months ago Rolling S<strong>to</strong>ne published the entire interview in its<br />

December 23, 2010 issue. While the interview revealed Lennon’s plans for a<br />

musical comeback just before his untimely death, longtime antiviolence activist,<br />

author, speaker and <strong>Voice</strong> <strong>Male</strong> contributing edi<strong>to</strong>r Jackson Katz was intrigued<br />

by something else. “Throughout the interview,” Katz writes, Lennon offered<br />

“a wealth of commentary related <strong>to</strong> his evolving ideas about manhood.” Katz<br />

believes that when Lennon was gunned down in front of his apartment building<br />

on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, the world lost not only one of the greatest<br />

musical talents of the 20th century, “it also lost an artist whose sense of himself<br />

as a man reflected the cultural shifts in gender norms that had been catalyzed by<br />

multicultural women’s movements; someone whose fame and example helped<br />

pioneer a new kind of masculinity for his and subsequent generations of men.”<br />

What follows are Katz’s thoughts on Lennon’s evolving ideas about masculinity,<br />

fatherhood and feminism.<br />

John Lennon is revered by many peace activists as an artist who used his<br />

public platform <strong>to</strong> oppose the U.S. war in Vietnam. His anthems “Happy<br />

Xmas (War Is Over),” “Give Peace a Chance” and “Imagine” are revered<br />

by millions worldwide. But Lennon was perhaps the most well-known male<br />

artist of his era <strong>to</strong> embrace feminism—and <strong>to</strong> incorporate feminist insights<br />

about masculinity and relationships in<strong>to</strong> his art.<br />

After a brief period of high-profile anti-Vietnam war activism in the early<br />

1970s, the former Beatle turned <strong>to</strong> subjects in his music and personal life that<br />

spoke <strong>to</strong> some of the changes faced by men of his generation: growing up and<br />

assuming adult responsibilities, nurturing more egalitarian relationships with<br />

women and being emotionally present for their children. One of his songs that<br />

decried sexism, “Woman Is The Nigger of the World” (1972), earned Lennon a<br />

spot in Michael Kimmel and Tom Mosmiller’s 1992 anthology Against the Tide:<br />

Pro-Feminist Men in the United States 1776-1990, a documentary his<strong>to</strong>ry.<br />

Lennon was a complicated person who struggled (often quite publicly)<br />

with his shortcomings as a father, a partner and a friend. He could be difficult<br />

and emotionally abusive. Many writers have noted that his audacious ambition<br />

and stunning musical achievements as a young man were propelled, in part,<br />

by his efforts <strong>to</strong> produce art through which he could communicate—and<br />

perhaps transcend—the pain he experienced as a young boy, when his parents<br />

effectively abandoned him. It is no small irony—and it is indefensible—that<br />

Lennon similarly neglected his first son, Julian.<br />

But despite the shortcomings of the man behind the myth, as a Beatle and as a<br />

solo act John Lennon produced some of the most popular and memorable music<br />

in his<strong>to</strong>ry. His songs have become a part of our cultural fabric and collective<br />

psyche; the enduring popularity of his artistic contributions is testament <strong>to</strong><br />

the fact that he connected—emotionally and intellectually—with hundreds<br />

of millions (billions?) of people. In light of that connection and Lennon’s<br />

continuing appeal, consider some of the things he said in his last interview on<br />

a range of <strong>to</strong>pics related <strong>to</strong> the major gender transformations of his—and our—<br />

time: fatherhood, <strong>to</strong>ugh guy posturing, feminism, and women. Three decades<br />

later his thoughts on these critical subjects are just as relevant and enduring as<br />

his music.<br />

<br />

<strong>Voice</strong> <strong>Male</strong>

On fatherhood:<br />

The thing about the child is... it’s still hard. I’m not the<br />

greatest dad on earth, I’m doing me best. But I’m a very irritable<br />

guy, and I get depressed. I’m up and down, up and down, and<br />

he’s (then-five-year-old son Sean) had <strong>to</strong> deal with that <strong>to</strong>o—<br />

withdrawing from him and then giving,<br />

and withdrawing and giving. I don’t know<br />

how much it will affect him in later life,<br />

but I’ve been physically t<strong>here</strong>.<br />

On <strong>to</strong>ugh guy<br />

posturing:<br />

I’m often afraid, but I’m not afraid<br />

<strong>to</strong> be afraid, otherwise it’s all scary. But<br />

it’s more painful <strong>to</strong> try not <strong>to</strong> be yourself.<br />

People spend a lot of time trying <strong>to</strong> be<br />

somebody else, and I think it leads <strong>to</strong><br />

terrible diseases. Maybe you get cancer<br />

or something. A lot of <strong>to</strong>ugh guys get<br />

cancer, have you noticed? John Wayne,<br />

Steve McQueen. I think it has something<br />

<strong>to</strong> do—I don’t know, I’m no expert—with<br />

constantly living or getting trapped in<br />

an image or an illusion of themselves,<br />

suppressing some part of themselves,<br />

whether it’s the feminine side or the<br />

fearful side.<br />

I’m well aware of that because I come<br />

from the macho school of pretense. I was<br />

never really a street kid or a <strong>to</strong>ugh guy. I<br />

used <strong>to</strong> dress like a Teddy boy and identify<br />

with Marlon Brando and Elvis Presley,<br />

but I never really was in real street fights<br />

or real down-home gangs. I was just a<br />

suburban kid, imitating the rockers. But it<br />

was a big part of one’s life <strong>to</strong> look <strong>to</strong>ugh. I spent the whole of my<br />

childhood with shoulders up around the <strong>to</strong>p of me head and me<br />

glasses off because glasses were sissy, and walking in complete<br />

fear, but with the <strong>to</strong>ughest-looking face you’ve ever seen... I<br />

wanted <strong>to</strong> be this <strong>to</strong>ugh James Dean all the time. It <strong>to</strong>ok a lot of<br />

wrestling <strong>to</strong> s<strong>to</strong>p doing that, even though I still fall in<strong>to</strong> it when I<br />

get insecure and nervous.<br />

On love, race and feminism:<br />

...we hear from all kinds of people. One kid living up in<br />

Yorkshire wrote this heartfelt letter about being both Oriental<br />

and English and identifying with John and Yoko. The odd kid in<br />

the class. T<strong>here</strong> are a lot of those kids who identify with us—as<br />

a couple, a biracial couple, who stand for love, peace, feminism<br />

and the positive things of the world.<br />

“I wanted <strong>to</strong> be this<br />

<strong>to</strong>ugh James Dean all<br />

the time. It <strong>to</strong>ok a lot of<br />

wrestling <strong>to</strong> s<strong>to</strong>p doing<br />

that, even though I still<br />

fall in<strong>to</strong> it when I get<br />

insecure and nervous.”<br />

On learning from women:<br />

I have <strong>to</strong> keep remembering that I never really was (a <strong>to</strong>ugh<br />

guy). That’s what Yoko has taught me. I couldn’t have done it<br />

alone—it had <strong>to</strong> be a female <strong>to</strong> teach me. That’s it. Yoko has been<br />

telling me all the time, “It’s all right, it’s all right.” I look at early<br />

pictures of meself, and I was <strong>to</strong>rn between<br />

being Marlon Brando and being the sensitive<br />

poet—the Oscar Wilde part of me with<br />

the velvet, feminine side. I was always<br />

<strong>to</strong>rn between the two, mainly opting for<br />

the macho side, because if you showed the<br />

other side, you were dead.<br />

On his song “Woman”<br />

(1972):<br />

“Woman” came about because, one<br />

sunny afternoon in Bermuda, it suddenly<br />

hit me what women do for us. Not just<br />

what my Yoko does for me, although I<br />

was thinking in those personal terms...<br />

but any truth is universal. What dawned<br />

on me was everything I was taking for<br />

granted. Women really are the other half<br />

of the sky, as I whisper at the beginning of<br />

the song. It’s a “we” or it ain’t anything.<br />

The song reminds me of a Beatles track,<br />

though I wasn’t trying <strong>to</strong> make it sound<br />

like a Beatles track. I did it as I did “Girl”<br />

many years ago -- it just sort of hit me like<br />

a flood, and it came out like that. “Woman”<br />

is the grown-up version of “Girl.”<br />

This interview—and many others over<br />

the years—makes clear that John Lennon<br />

was strong enough both <strong>to</strong> acknowledge<br />

his own vulnerability and fear, and also<br />

<strong>to</strong> embrace women’s leadership, both personally and politically.<br />

For a man who would have turned 70 last year, he was way<br />

ahead of the curve. It is one of the defining tragedies of our<br />

cultural moment that a non-violent man—the leader of the<br />

Beatles!—who possessed the rare gift of translating his genderbending<br />

introspection in<strong>to</strong> brilliant, accessible art was ultimately<br />

silenced by another man’s violence.<br />

John Lennon’s final Rolling S<strong>to</strong>ne interview can be found<br />

at:www.rollings<strong>to</strong>ne.com/music/news/john-lennons-finalinterview-20101207.<br />

<strong>Voice</strong> <strong>Male</strong> contributing edi<strong>to</strong>r Jackson<br />

Katz is author of The Macho Paradox and<br />

writer-producer, with the Media Education<br />

Foundation, of Tough Guise: Violence,<br />

Media and the Crisis in Masculinity (www.<br />

jacksonkatz.com).<br />

Winter 2011

OutLines<br />

The tragic suicide of Rutgers<br />

University first-year student Tyler<br />

Clementi last fall led <strong>to</strong> a wave of<br />

national hand-wringing anguish about the<br />

daily <strong>to</strong>rture and humiliations suffered by<br />

young gays and lesbians. An article in The<br />

New York Times expanded the conversation<br />

<strong>to</strong> include the s<strong>to</strong>ries of several other gay<br />

teens who recently committed suicide,<br />

such as Seth Walsh of Fresno, Calif., who<br />

endured a “relentless barrage of taunting,<br />

bullying and other abuse at the hands of his<br />

peers.” Walsh hanged himself in September<br />

at age 13.<br />

Gay<br />

Bashing<br />

Is About<br />

Masculinity<br />

By Michael Kimmel<br />

Yet, in our collective search for<br />

explanations and solutions we’ve missed<br />

one salient fact. Here are the names of<br />

the teenagers in The Times article: Tyler<br />

Clementi, Seth Walsh, Billy Lucas, Asher<br />

Brown. Notice anything?<br />

They’re all boys.<br />

Writing that gay “teens” suffer such<br />

relentless abuse or bullying obscures as much<br />

as it reveals. It’s not “teens.” It’s boys.<br />

Yes, lesbian teens can be relentlessly<br />

<strong>to</strong>rmented, harassed and bullied in school.<br />

They can be mercilessly taunted in<br />

cyberspace, and shunned in real space.<br />

But the amount of rage they inspire rarely<br />

compares <strong>to</strong> that experienced by boys.<br />

And that’s not because of the current<br />

fad of faux-lesbianism among teenage<br />

girls. Sure, it’s true that many teen girls<br />

have “kissed a girl” and “liked it,” as Katy<br />

Perry proclaims. But t<strong>here</strong> is something<br />

fundamental about male homosexuality<br />

that elicits what psychologists call<br />

“homosexual panic,” and a near-hysterical<br />

effort <strong>to</strong> circle the wagons and get rid of<br />

the perceived threat.<br />

For my book Guyland I interviewed<br />

nearly 400 young people all across the<br />

country. I found that many of America’s<br />

high schools have become gauntlets<br />

through which students must pass every<br />

day. Bullies roam the halls, targeting the<br />

most vulnerable or isolated, beating them<br />

up, destroying their homework, shoving<br />

them in<strong>to</strong> lockers, dunking their heads in<br />

<strong>to</strong>ilets or just relentlessly mocking them.<br />

It’s all done in public—on playgrounds,<br />

bathrooms, hallways, even in class. And<br />

the other kids either laugh and encourage<br />

it or scurry <strong>to</strong> the walls, hoping <strong>to</strong> remain<br />

invisible so that they won’t become the<br />

next target. For many, just being noticed for<br />

being “uncool” or “weird” is a great fear.<br />

Why are some students targeted?<br />

Because they’re gay or even “seem” gay—<br />

which may be just as disastrous for a teenage<br />

boy. After all, the most common put-down<br />

in American high schools <strong>to</strong>day is “that’s so<br />

gay,” or calling someone a “fag.” It refers<br />

<strong>to</strong> anything and everything: what kind of<br />

sneakers you have on, what you’re eating<br />

for lunch, some comment you made in class,<br />

who your friends are or what sports team<br />

you like. The average high school student<br />

in Des Moines hears an anti-gay comment<br />

every seven minutes, and teachers intervene<br />

only about 3 percent of the time. After<br />

spending a year in a California high school,<br />

one sociologist titled her ethnographic<br />

account Dude, You’re a Fag.<br />

It’s true that gays and lesbians are far<br />

more often the target of hostility than their<br />

straight peers. But it’s often true that antigay<br />

sentiments are only partly related <strong>to</strong><br />

sexual orientation. Calling someone gay or a<br />

fag has become so universal that it’s become<br />

synonymous with dumb, stupid or wrong.<br />

And it’s “dumb” or “wrong” because<br />

it isn’t masculine enough. To the “that’sso-gay”<br />

chorus, homosexuality is about<br />

10 <strong>Voice</strong> <strong>Male</strong>

gender nonconformity, not being a “real<br />

man,” and so anti-gay sentiments become<br />

a shorthand method of gender policing.<br />

One survey found that most American boys<br />

would rather be punched in the face than<br />

called gay. Tell a guy that what he is doing<br />

or wearing is “gay,” and the gender police<br />

have just written him a ticket. If he persists,<br />

they might have <strong>to</strong> lock him up.<br />

Many guys think being gay means<br />

not being a guy. That’s the choice: gay or<br />

guy. In a study by Human Rights Watch,<br />

heterosexual students consistently reported<br />

that the targets were simply boys who were<br />

un-athletic, dressed nicely, or were bookish<br />

and shy.<br />

Take the case of Jesse Montgomery,<br />

who filed a Title IX suit in the Minnesota<br />

courts after suffering 11 years of verbal<br />

and physical abuse. Jesse was treated <strong>to</strong> a<br />

daily verbal barrage of “faggot,” “queer,”<br />

“homo,” “gay,” “girl,” “princess,” “fairy,”<br />

“freak,” “bitch,” “pansy” and more. He was<br />

regularly punched, kicked, tripped. Some<br />

of the <strong>to</strong>rment was directly sexual: One of<br />

the students grabbed his own genitals while<br />

squeezing Jesse’s but<strong>to</strong>cks and on other<br />

occasions would stand behind him and grind<br />

his penis in Jesse’s backside.<br />

By the way, Jesse Montgomery is<br />

straight. So, <strong>to</strong>o, was Dylan Theno, an 18-<br />

year-old former student at Tonganoxie High<br />

School in Kansas. Beginning in the seventh<br />

grade, he was consistently taunted as<br />

“flamer,” “faggot” and “masturba<strong>to</strong>r boy,”<br />

harassed daily in the lunchroom and on the<br />

playground. Teachers looked the other way<br />

or laughed along with the harassers. Why?<br />

Dylan explained: “Because I was a different<br />

kid, you know, I wasn’t the alpha male. …<br />

I had different hair than everybody else; I<br />

wore earrings … I wasn’t a big time sports<br />

guy at school.”<br />

Of course, if you actually are gay,<br />

the harassment is relentless—and often<br />

dismissed entirely by the adults in charge<br />

or, worse, considered appropriate. Take<br />

the case of Jamie Nabozny in the mid-<br />

1990s. Beginning in middle school, he<br />

was harassed, spit on, urinated on, called<br />

a “fag” by a teacher and mock-raped while<br />

at least 20 other students looked on and<br />

laughed. Each time the school principals<br />

and teachers shrugged off his complaints,<br />

telling Jamie that he should “expect” this<br />

sort of treatment if he’s gay and that, well,<br />

“Boys will be boys.”<br />

Nabozny successfully sued the school<br />

district and the principals of both his middle<br />

school and high school, who paid out close<br />

<strong>to</strong> $1 million in damages. His lawsuit<br />

opened a door for those who are the targets<br />

of bullying and harassment in school,<br />

because school districts and administra<strong>to</strong>rs<br />

may be held liable if they do not intervene<br />

effectively <strong>to</strong> s<strong>to</strong>p the abuse.<br />

But gender non-conforming boys still<br />

need protection—not just from the bullies<br />

but from the teachers, parents, administra<strong>to</strong>rs<br />

and community members who look the other<br />

way, at best, or collude with it.<br />

Most Americans find explicit racist and<br />

anti-Semitic behavior unacceptable, an<br />

affront <strong>to</strong> their moral sensibilities. Racism<br />

and anti-Semitism are out of bounds even<br />

when they don’t become physical, and most<br />

of us believe that those who openly express<br />

those sentiments should be severely punished.<br />

Why is the same not true of gay bashing?<br />

Michael Kimmel, a<br />

<strong>Voice</strong> <strong>Male</strong> contributing<br />

edi<strong>to</strong>r, is author or edi<strong>to</strong>r<br />

of more than 20 books on<br />

masculinity and teaches<br />

in the Sociology Department<br />

at the State University<br />

of New York at S<strong>to</strong>ny<br />

Brook.<br />

Winter 2011 11

Flying My Freak Flag at Half-mast<br />

By Michael A. Messner<br />

Not long ago I pulled the plug on my four-decade flirtation<br />

with the John Lennon Look. A few years back, I had<br />

already quit with the round granny glasses. But now, at<br />

age 57, I’ve truly done it: I cut my hair. I really had little choice,<br />

having observed with growing horror the death throes of the thinning<br />

diaphanous do above my rapidly growing forehead. Oh, t<strong>here</strong>’s still<br />

enough hair <strong>to</strong> run a comb through. But when I gaze in<strong>to</strong> the mirror<br />

while standing under the unforgiving fluorescent lights in a public<br />

restroom, the truth is revealed—I am crowning like a newborn,<br />

the oval <strong>to</strong>p of my increasingly shiny skull transparent through the<br />

graying wisps. What I see is a shock—not of hair, but of cranium.<br />

My hair is not entirely gone: it’s still ample on the sides, and on<br />

<strong>to</strong>p a sparse tuft survives, still substantial enough that I’ve not yet<br />

begun <strong>to</strong> take daily inven<strong>to</strong>ry of the individual hairs—or <strong>to</strong> name<br />

them (as in, “Oh, honey, as we slept last night, I lost Walter!”). But<br />

rather than resembling as they once did a neatly unified congregation<br />

flowing uni-directionally in some shared faith, the follicles a<strong>to</strong>p my<br />

head are now akin <strong>to</strong> a shrinking gathering of nonbelievers, upright<br />

but akimbo in surprise during a cruel moment of final judgment.<br />

Like so many mid-1960s American boys, in the wake of the<br />

British Invasion I abandoned my crew-cut, and urged my straight<br />

brown hair <strong>to</strong> creep over my ears and forehead, as far as would be<br />

allowed by parents and coaches. My dad, it turned out, was both my<br />

parent and my coach (a particular breed of post-World War II man<br />

passionately committed <strong>to</strong> the idea that long hair on their sons erased<br />

their own ability <strong>to</strong> make the crucial distinction between boys and<br />

girls). Later, off <strong>to</strong> college, I was freed up <strong>to</strong> cultivate a semi-sloppy<br />

“hippie look.” Long hair became more than a style: it was a political<br />

statement, a sign of my opposition <strong>to</strong> war, patriarchy, and “the establishment.”<br />

The equation was simple: Short hair = Nixon; long hair<br />

= a New Man, peaceful and egalitarian. As usual, John Lennon in<br />

12 <strong>Voice</strong> <strong>Male</strong><br />

Viet Nam War protest, 1971 pho<strong>to</strong>: Diana Davies<br />

1971 drew the line in the sand between the violent lies of Nixon and<br />

the truth of our Nu<strong>to</strong>pian vision:<br />

I’ve had enough of reading things by neurotic, psychotic, pig-headed<br />

politicians, all I want is the truth, just give me some truth, no shorthaired,<br />

yellow-bellied son of Tricky Dicky is gonna mother hubbard<br />

soft soap me with just a pocketful of hope<br />

During the 1968 elections, Sena<strong>to</strong>r Eugene McCarthy’s peace<br />

campaign for the presidency inspired some from my generation <strong>to</strong><br />

go “Clean for Gene.” Four years later, many young people rallied<br />

similarly behind Sena<strong>to</strong>r George McGovern, hoping he would<br />

reverse Nixon’s terrible war. I resisted the drift <strong>to</strong>ward conventional<br />

attire and the pull of liberal politics. Already, the lyrics of David<br />

Crosby’s 1970 anthem <strong>to</strong> the deeper meanings of long hair looped<br />

inside my head:<br />

Almost cut my hair<br />

It happened just the other day<br />

It’s gettin’ kind of long<br />

I coulda’ said it was in my way<br />

But I didn’t, and I wonder why<br />

I feel like letting my freak flag fly<br />

Yes I feel like I owe it <strong>to</strong> someone.<br />

Did others besides me buy this illogic? In retrospect, it’s amusing<br />

that Crosby’s nebulous “explanation” for keeping his hair long resonated<br />

with anybody. Maybe we were all ingesting the same mindmuddling<br />

substances at the time; I don’t know. But I do recall that,<br />

with some degree of self-righteousness, I continued <strong>to</strong> sport long hair<br />

as a statement of my anti-establishment identity.<br />

Long hair on guys didn’t retain its radical political meanings for<br />

long. In the 1980s, I should have gotten my first motley clue from<br />

the mullet, a truly unfortunate look that likely inspired many men’s<br />

return <strong>to</strong> the barbershop. And by the 1990s, it seemed that the only<br />

longhaired male musicians were twanging Country or shredding<br />

Heavy Metal, two genres I could not s<strong>to</strong>mach. Most of the rockers<br />

I admired—Eric Clap<strong>to</strong>n, Mark Knopfler, Neil Young—had gone<br />

<strong>to</strong> a shorter look. Even Paul McCartney was keeping his mop<br />

neatly trimmed (and presumably dyed). By the turn of the millennium,<br />

some middle-aged men faced up <strong>to</strong> imminent hair loss with<br />

a suddenly-fashionable Bruce-Willis-pre-emptive depilation. When<br />

my brother-in-law Willy (who in his shaggy youth was frequently<br />

mistaken for Jerry Garcia or Karl Marx) went shiny billiard-ball, I<br />

should have noticed that the fashion shift had penetrated the grassroots<br />

of society. But I remained stubborn in my longhairishness, still<br />

figuring, I suppose, I owed it <strong>to</strong> someone.<br />

For a time, I fought <strong>to</strong> preserve my gray, thinning mane. Three<br />

or four years ago, I considered using Rogaine. But simply reading<br />

the instructions on the box turned me off. Slather slimy goop on my<br />

head every day? And leave it t<strong>here</strong>? Yeccch! Ever since the midsixties,<br />

when I’d joined the generational rejection of Brylcreem and<br />

other “greasy kids’ stuff,” I had sailed proudly under the banner that<br />

the wet-head is dead.

But then my doc<strong>to</strong>r introduced me <strong>to</strong> a little blue pill called<br />

Propecia. Before taking it, I looked it up online and learned that most<br />

men who take the drug daily for a three-month period of time experience<br />

noticeable “hair re-growth” that reverses hair loss. Eureka,<br />

yes! Let a thousand follicles bloom! And oh, yes: Clinical studies<br />

also showed that “A small number of men had sexual side effects,<br />

occurring in less than 2% of men. These include less desire for sex,<br />

difficulty in achieving an erection, and a decrease in the amount<br />

of semen.” Seeking a second opinion, I found another website that<br />

reported even better odds: only 1.8 percent of men who take Propecia<br />

experience decreased libido, a mere 0.8 percent a decreased volume<br />

of ejaculate, and incidence of impotence is “less than one percent.”<br />

Lucky me <strong>to</strong> learn that I am so rare as <strong>to</strong> be included in an epidemiologically<br />

singular group of less than 1 percent! To be concrete,<br />

after three weeks of swallowing the magical blue pill, I began <strong>to</strong><br />

wither w<strong>here</strong> it most mattered. In the manhood department below<br />

the belt, I had always already been painfully average in size—oh, a<br />

bit below average in size, okay? But this had never been a problem.<br />

My wife, Pierrette, is petite, standing a full foot shorter than I, and<br />

weighing eighty pounds less. Once in the early 1980s, as a younger<br />

couple strolling in a neighborhood of Mexico City, Pierrette and I<br />

walked by a group of snickering men. One of them made a comment,<br />

and they all burst in<strong>to</strong> laughter. After we had passed the men, Pierrette<br />

translated: “He said, ‘How does he reach her?’” Now, gentle<br />

reader, you can intuit the answer <strong>to</strong> this question.<br />

But now, after three weeks of Propecia, I had <strong>to</strong> make a choice:<br />

accept a self-imposed flaccidity (albeit potentially <strong>to</strong>pped off with<br />

a full noggin of hair), or capitulate <strong>to</strong> a balding crown (but with<br />

continued virile tumescence). If forced <strong>to</strong> choose thusly, which freak<br />

flag would you elect <strong>to</strong> fly?<br />

It was not that hard <strong>to</strong> decide. Now, with my hair cut shorter, I<br />

have found that I’ve not yet been ejected from any clubs—political,<br />

professional or musical. My friends and family still love me, and<br />

my students still take notes when I speak. It turns out apparently that<br />

nobody felt I owed it <strong>to</strong> them <strong>to</strong> keep my hair long. And maybe, I<br />

have <strong>to</strong> admit, I look less bad as a shorthair. A 20-year-old mophead<br />

in 1972 may have shined with sexy, youthful rebellion. A mophead<br />

pushing 60 comes across more like, well, an inverted worn-out mop,<br />

with gravity tugging the lifeless gray threads down on the sides.<br />

Life transitions, however unwelcome, can bring small and<br />

surprising benefits. With my hair now more closely cropped, I have<br />

discovered older women on occasion bat their eyes and say that I<br />

look just like Clint Eastwood. To be sure, this is not the look I was<br />

going for. After all, Eastwood is what?—20, 25 years older than me?<br />

(He’s no John Lennon, either, I should add.) Overriding my objections,<br />

a woman friend recently advised my wife, “I wouldn’t take it<br />

as an insult; Clint is hot.” So I have decided <strong>to</strong> take this unexpected<br />

comparison as a compliment. Or perhaps, at least, as the only sort<br />

of compliment I can expect <strong>to</strong> get from <strong>here</strong> on in.<br />

<strong>Voice</strong> <strong>Male</strong> contributing edi<strong>to</strong>r Michael<br />

Messner is professor of sociology and gender<br />

studies at the University of Southern California.<br />

His memoir, King of the Wild Suburb:<br />

A Memoir of Fathers, Sons and Guns, will be<br />

published this spring by Plain View Press.<br />

Winter 2011 13

10 Things Men<br />

and Boys Can Do<br />

<strong>to</strong> S<strong>to</strong>p Human<br />

Trafficking<br />

By Jewel Woods<br />

Human trafficking is modern-day<br />

slavery. It is the use of force, fraud,<br />

or coercion <strong>to</strong> compel another person<br />

<strong>to</strong> provide labor or commercial sex against<br />

their will, and it is one of the fastest growing<br />

criminal enterprises in the world.<br />

The Renaissance <strong>Male</strong> Project believes<br />

that men are complicit in this crime when they<br />

purchase sex because they create the demand<br />

by allowing others <strong>to</strong> exploit women and<br />

children for profit. Men must play a role in<br />

ending this form of slavery, a vicious industry<br />

that exploits and perpetuates the suffering of<br />

hundreds of thousands of women and children<br />

in the United States and around the world.<br />

Based on a list of statistics that the Polaris<br />

Project compiled:<br />

▪ A <strong>to</strong>tal of 27 million are enslaved globally.<br />

▪ Between 14,500 and 17,500 individuals are<br />

brought in<strong>to</strong> the U.S. as human trafficking<br />

victims each year.<br />

▪ One million children enter the global commercial<br />

sex trade every year.<br />

T<strong>here</strong> are specific actions that men and<br />

boys can take <strong>to</strong> end these atrocities:<br />

14 <strong>Voice</strong> <strong>Male</strong><br />

1. Challenge the glamorization<br />

of pimps in our culture<br />

Mainstream culture has popularized the<br />

image of a pimp <strong>to</strong> the point that some men<br />

and boys look up <strong>to</strong> them as if they represent<br />

legitimate male role models, and they view<br />

“pimping” as a normal expression of masculinity.<br />

As Carrie Baker reflects in “Jailing Girls<br />

for Men’s Crimes” in the Summer 2010 Ms.<br />

issue, the glorification of prostitution is often<br />

rewarded, not punished, in pop culture:<br />

Reebok awarded a multi-million-dollar<br />

contract for two shoe lines <strong>to</strong> rapper 50 Cent,<br />

whose album Get Rich or Die Tryin (with the<br />

hit single “P.I.M.P.”) went platinum. Rapper<br />

Snoop Dogg, who showed up at the 2003 MTV<br />

Video Music Awards with two women on dog<br />

leashes and who was described in the December<br />

2006 cover of Rolling S<strong>to</strong>ne as “America’s<br />

Most Lovable Pimp,” has received endorsement<br />

deals from Orbit gum and Chrysler.<br />

In reality, pimps play a central role in<br />

human trafficking and routinely rape, beat and<br />

terrorize women and girls <strong>to</strong> keep them locked<br />

in prostitution. Men can take a stand against<br />

pimps and pimping by renouncing the pimp<br />

culture and the music that glorifies it.<br />

2. Confront the belief that<br />

prostitution is a<br />

“victimless crime”<br />

Many men view prostitution as a “victimless<br />

crime.” But it is not. For example, American<br />

women who are involved in prostitution<br />

are at a greater risk <strong>to</strong> be murdered than<br />

women in the general population. Research<br />

also shows that women involved in prostitution<br />

suffer tremendous physical and mental<br />

trauma associated with their work. Viewing<br />

prostitution as a victimless crime or something<br />

that women “choose” allows men <strong>to</strong> ignore the<br />

fact that the average age of entry in<strong>to</strong> prostitution<br />

in the U.S. is 12 <strong>to</strong> 14 and that the vast<br />

majority of women engaged in prostitution<br />

would like <strong>to</strong> get out but feel trapped. Men<br />

should s<strong>to</strong>p viewing prostitution as a victimless<br />

crime and acknowledge the tremendous<br />

harm and suffering their participation in<br />

prostitution causes.<br />

3. S<strong>to</strong>p patronizing strip clubs<br />

When men think of human trafficking, they<br />

often think of brothels in countries outside of<br />

the U.S. However, strip clubs in this country as<br />

well as abroad may be a place w<strong>here</strong> human traf-

ficking victims go unnoticed or<br />

unidentified. Strip clubs are also<br />

places of manufactured pleasure<br />

w<strong>here</strong> strippers are routinely<br />

sexually harassed and assaulted<br />

by owners, patrons and security<br />

personnel. Men rarely consider<br />

whether women working in strip<br />

clubs are coerced in<strong>to</strong> that line<br />

of work, because <strong>to</strong> do so would<br />

conflict with the pleasure of<br />

participating in commercialized<br />

sex venues. Men can combat<br />

human trafficking by no longer<br />

patronizing strip clubs and by<br />

encouraging their friends and<br />

coworkers <strong>to</strong> do the same.<br />

4. Don’t consume<br />

pornography<br />

Pornography has the power<br />

<strong>to</strong> manipulate male sexuality,<br />

popularize unhealthy attitudes<br />

<strong>to</strong>ward sex and sexuality and eroticize violence<br />

against women. Pornography leads men and<br />

boys <strong>to</strong> believe that certain sexual acts are<br />

normal, when in fact sexual acts that are nonconsensual,<br />

offensive and coupled with violent<br />

intent result in the pain, suffering and humiliation<br />

of women and children. In addition,<br />

a disproportionate amount of mainstream<br />

pornography sexualizes younger women with<br />

such titles as “teens,” “barely 18,” “cheerleaders,”<br />