Queensland Art Gallery - Queensland Government

Queensland Art Gallery - Queensland Government

Queensland Art Gallery - Queensland Government

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Publisher<br />

<strong>Queensland</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong><br />

Stanley Place, South Bank, Brisbane<br />

PO Box 3686, South Brisbane<br />

<strong>Queensland</strong> 4101 Australia<br />

www.qag.qld.gov.au<br />

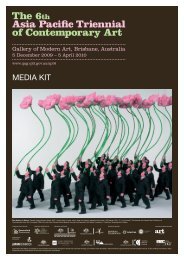

Published for ‘The 6th Asia Pacific Triennial of<br />

Contemporary <strong>Art</strong>’, organised by the <strong>Queensland</strong><br />

<strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong> and held at the <strong>Gallery</strong> of Modern<br />

<strong>Art</strong> and the <strong>Queensland</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong>, Brisbane,<br />

Australia, 5 December 2009 – 5 April 2010.<br />

© <strong>Queensland</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong>, 2009<br />

This work is copyright. Apart from any use as<br />

permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no<br />

part may be reproduced without prior written<br />

permission from the publisher. No illustration in<br />

this publication may be reproduced without the<br />

permission of the copyright owners. Requests<br />

and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights<br />

should be addressed to the publisher.<br />

Copyright for texts in this publication is held by<br />

the <strong>Queensland</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong> and the authors.<br />

Copyright for all art works and images is held<br />

by the creators or their representatives, unless<br />

otherwise stated. Copyright of photographic<br />

images is held by individual photographers and<br />

institutions or the <strong>Queensland</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong>.<br />

Every attempt has been made to locate holders<br />

of copyright and reproduction rights of all images<br />

reproduced in this publication. The publisher<br />

would be grateful to hear from any reader with<br />

further information.<br />

Care has been taken to ensure the colour<br />

reproductions match as closely as possible the<br />

supplied transparencies, film stock or digital files<br />

of the original works.<br />

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-<br />

Publication data:<br />

Author: Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary<br />

<strong>Art</strong> (6th : 2009 : Brisbane, Qld.)<br />

Title: The 6th Asia Pacific Triennial<br />

of Contemporary <strong>Art</strong>.<br />

ISBN: 9781921503085 (pbk.)<br />

Subjects: <strong>Art</strong>, Asian--21st century--Exhibitions.<br />

<strong>Art</strong>, Pacific Island--21st century--Exhibitions.<br />

Other Authors/Contributors: <strong>Queensland</strong><br />

<strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong>.<br />

Dewey Number: 709.50905<br />

ISBN 978 1 921503 08 5<br />

Notes on the publication<br />

The order of the artists’ family names and given<br />

names varies depending on the conventions used<br />

in their respective home countries, or the artist’s<br />

own preference.<br />

Text for this publication has been supplied by the<br />

authors as attributed. The views expressed are not<br />

necessarily those of the publisher.<br />

Dimensions of works are given in centimetres (cm),<br />

height preceding width followed by depth.<br />

Captions generally appear as supplied by lenders.<br />

All photography is credited as known.<br />

Typeset in Avenir and Clarendon. Printed by<br />

Platypus Graphics, Brisbane, on Novatech Satin<br />

from Raleigh Paper.<br />

Cover (including back cover and inside gatefold details):<br />

Kohei Nawa<br />

Japan b.1975<br />

PixCell-Elk#2 2009<br />

Taxidermied elk, glass, acrylic, crystal beads /<br />

240 x 249.5 x 198cm / Work created with the support<br />

of the Fondation d’enterprise Hermės / Image courtesy:<br />

The artist and SCAI, Tokyo / Photograph: Seiji Toyonaga<br />

Page 6–7:<br />

Subodh Gupta<br />

India b.1964<br />

Line of Control (1) (detail) 2008<br />

Stainless steel and steel structure, brass and copper<br />

utensils / 500 x 500 x 500cm / Image courtesy: The artist<br />

and Arario <strong>Gallery</strong>, Beijing<br />

Page 8–9:<br />

Rudi Mantofani<br />

Indonesia b.1973<br />

Nada yang hilang (The lost note) (detail) 2006–07<br />

Wood, metal, leather and oil / 9 pieces: 260 x 45 x 9cm<br />

(each) / Collection: Dr Oei Hong Djien / Image courtesy:<br />

The artist and Gajah <strong>Gallery</strong>, Singapore / Photograph:<br />

Agung Sukindra<br />

Page 10–11:<br />

Kim Gi Chol<br />

North Korea (DPRK) b.1959<br />

The Songchun River Clothing Factory team arrives<br />

(detail) 1999<br />

Ink on paper / 135.5 x 250cm / Collection:<br />

Nicholas Bonner, Beijing<br />

Page 12–13:<br />

Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian<br />

Iran b.1924<br />

Lightning for Neda (detail) 2009<br />

Mirror mosaic, reverse glass painting, plaster on wood /<br />

6 panels: 300 x 200cm (each) / Commissioned for APT6<br />

and the <strong>Queensland</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong> Collection. The artist<br />

dedicates this work to the loving memory of her late<br />

husband Dr Abolbashar Farmanfarmaian / Purchased<br />

2009. <strong>Queensland</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong> Foundation / Collection:<br />

<strong>Queensland</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong><br />

QUEENSLAND ART GALLERY

Contents<br />

16 Premier’s message / Anna Bligh<br />

68 Minam Apang Tales from the deep / Miranda Wallace<br />

140 Tracey Moffatt Plantation / Julie Ewington<br />

200 Building bridges: 10 years of Kids’ APT / Andrew Clark<br />

17 Sponsor message / Santos<br />

71 Alfredo and Isabel Aquilizan In flight / Michael Hawker<br />

143 Farhad Moshiri Hybrid confections / Abigail Fitzgibbons<br />

206 Kids’ APT artist projects<br />

18 Sponsors<br />

72 Chen Chieh-jen On going / Naomi Evans<br />

144 Kohei Nawa Seeing is believing / Michael Hawker<br />

21 Director’s foreword / Tony Ellwood<br />

75 Chen Qiulin Salvaged from ruins / Angela Goddard<br />

147 Shinji Ohmaki Dissolving into light / Shihoko Iida<br />

76 Cheo Chai-Hiang Cash converter / Yvonne Low<br />

148 The One Year Drawing Project / Suhanya Raffel<br />

79 DAMP Untitled and indefinite / Francis E Parker<br />

152 Pacific Reggae Roots Beyond the Reef / Brent Clough<br />

218 Catalogue of works<br />

80 Solomon Enos Polyfantastica / David Burnett<br />

157 Rithy Panh Gestures of protest / Amanda Slack-Smith<br />

230 <strong>Art</strong>ist biographies<br />

24 A restless subject / Suhanya Raffel<br />

85 Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian Lightning for Neda /<br />

158 Reuben Paterson Pathways through history /<br />

242 Australian Cinémathèque Programs Promised Lands /<br />

32 Rites and rights: Contemporary Pacific / Maud Page<br />

Suhanya Raffel<br />

Angela Goddard<br />

The Cypress and the Crow: 50 Years of Iranian Animation<br />

42 Promised lands / Jose Da Silva and Kathryn Weir<br />

86 Subodh Gupta Cold war kitchen / David Burnett<br />

161 Campbell Patterson Intimate videos / Francis E Parker<br />

252 Acknowledgments<br />

50 The hungry goat: Iranian animation, media archaeology<br />

89 Gonkar Gyatso Trouble in paradise / Suhanya Raffel<br />

162 Wit Pimkanchanapong In-between spaces / Donna McColm<br />

259 Contributing authors<br />

and located visual worlds / Kathryn Weir<br />

90 Kyungah Ham Communication beyond<br />

165 Qiu Anxiong The new book of mountains and seas /<br />

58 The world and the studio / Russell Storer<br />

the unreachable place / Jose Da Silva<br />

Sarah Stutchbury<br />

93 Ho Tzu Nyen Of the way of the creator / Russell Storer<br />

166 Kibong Rhee There is no place / Donna McColm<br />

94 Emre Hüner Panoptikon / Naomi Evans<br />

169 Hiraki Sawa Active stillness / Mellissa Kavenagh<br />

97 Raafat Ishak Pathways in paint / Bree Richards<br />

170 Shirana Shahbazi A purely visual language / Bree Richards<br />

98 Runa Islam Things that are restless and<br />

173 Shooshie Sulaiman Who’s afraid of the dark? /<br />

things that are still / Kathryn Weir<br />

Ellie Buttrose<br />

101 Ayaz Jokhio Toward the within / Russell Storer<br />

174 Thukral and Tagra Dream merchants / Russell Storer<br />

102 Takeshi Kitano Fallen hero / Rosie Hays<br />

179 Charwei Tsai A space of contemplation / Ruth McDougall<br />

105 Ang Lee Quiet! The film is about to start / Ellie Buttrose<br />

180 Vanuatu Sculptors Innovation and tradition /<br />

106 Mansudae <strong>Art</strong> Studio and art in North Korea (DPRK) /<br />

Ruth McDougall<br />

Nicholas Bonner<br />

184 Traditions and rituals in North Ambrym /<br />

114 Rudi Mantofani What is aslant and what is oblique /<br />

Napong Norbert<br />

Julie Ewington<br />

186 Rohan Wealleans Ritual and excess / Nicholas Chambers<br />

117 Mataso Printmakers / David Burnett<br />

189 Robin White, Leba Toki and Bale Jione A shared garden /<br />

120 Mapping the Mekong / Rich Streitmatter-Tran<br />

Ruth McDougall<br />

125 Bùi Công Khánh Contemporary story / Ian Were<br />

190 Yang Shaobin X – Blind Spot / Abigail Fitzgibbons<br />

126 Jun Nguyen-Hatsushiba Breathing is free / Shihoko Iida<br />

193 Yao Jui-chung Wandering in the lens / Jose Da Silva<br />

129 Sopheap Pich 1979 / Mellissa Kavenagh<br />

196 YNG (Yoshitomo Nara and graf) Discovering new worlds /<br />

130 Manit Sriwanichpoom The agony of waiting /<br />

Nicholas Chambers<br />

Russell Storer<br />

199 Zhu Weibing and Ji Wenyu People holding flowers /<br />

135 Svay Ken Painting from life / Russell Storer<br />

Abigail Fitzgibbons<br />

136 Tun Win Aung and Wah Nu Between the two /<br />

Rich Streitmatter-Tran<br />

139 Vandy Rattana Fire of the year / Mellissa Kavenagh<br />

14 15

Premier’s message<br />

Anna Bligh mp<br />

Premier of <strong>Queensland</strong> and Minister for the <strong>Art</strong>s<br />

Sponsor message<br />

Rick Wilkinson<br />

President <strong>Queensland</strong> & GLNG<br />

The <strong>Queensland</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong>’s Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary <strong>Art</strong> (APT) has become one<br />

of Australia’s most anticipated international cultural events, earning <strong>Queensland</strong> an enviable<br />

position in the contemporary art world.<br />

The <strong>Queensland</strong> <strong>Government</strong> has supported the Asia Pacific Triennial since its inception in<br />

1993, building the <strong>Gallery</strong> of Modern <strong>Art</strong> (GoMA) as a home for this spectacular exhibition<br />

and for contemporary art.<br />

APT6 incorporates more than 100 artists from many nations and across many disciplines.<br />

GoMA has dedicated more than 5000 square metres of gallery, cinema and children’s activity<br />

space to the exhibition, and the original <strong>Queensland</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong> has also devoted significant<br />

space to the Triennial.<br />

The <strong>Queensland</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong> is recognised as an international leader in contemporary Asian and<br />

Pacific art and has been building its collection for almost two decades. The APT is unique and<br />

remains the only recurring exhibition to focus on the contemporary art of Asia, the Pacific and<br />

Australia. It attracts strong interest from outside <strong>Queensland</strong>, with more than a third of visitors to<br />

APT5 coming from interstate or overseas. With the five exhibitions since 1993 attracting a total of<br />

more than 1.3 million visitors, it’s clear there’s an audience for art work from Asia and the Pacific.<br />

At Santos we have been putting our energy into <strong>Queensland</strong> for more than 50 years, unlocking<br />

the state’s vast natural gas resources. We also put our energy into the communities we are part<br />

of, supporting events and organisations that are valued by and enrich those communities.<br />

Santos has been involved with the <strong>Queensland</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong>, an institution that is central to<br />

<strong>Queensland</strong>’s cultural life, since 1990. The art within its walls has the power to inspire and<br />

challenge us. It helps us to view the world in ways we might not have recognised before.<br />

We are delighted to be continuing our association with the <strong>Gallery</strong> as the Presenting Sponsor<br />

for ‘The 6th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary <strong>Art</strong>’. Showcasing the creativity of our Asia<br />

Pacific region brings people and ideas together in all their diversity, and everyone benefits<br />

from this exchange.<br />

Santos supports the arts, because we’re not just an energy company, we’re a company<br />

with energy.<br />

I trust you will enjoy this publication, a record of what you have seen and experienced<br />

at this outstanding exhibition.<br />

This event brings together two of <strong>Queensland</strong>’s mainstays — our cultural and tourism industries<br />

— and I encourage <strong>Queensland</strong>ers to experience for themselves this fantastic celebration of<br />

contemporary visual art.<br />

16 17

Sponsors<br />

FOUNDING SUPPORTER<br />

PRESENTING SPONSOR<br />

Principal Benefactor<br />

PRINCIPAL PARTNERS<br />

Assisted by the Australian <strong>Government</strong> through the<br />

Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory body,<br />

and the Visual <strong>Art</strong>s and Craft Strategy, an initiative of<br />

the Australian, State and Territory <strong>Government</strong>s.<br />

MAJOR SPONSORS<br />

TOURISM & MEDIA PARTNERS<br />

SUPPORTING SPONSORS<br />

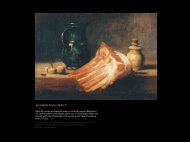

Shirana Shahbazi<br />

Iran/Switzerland b.1974<br />

[Stilleben-22-2008] (from ‘Flowers, fruits & portraits’<br />

series) 2003–ongoing, printed 2009<br />

Type C photograph, ed. of 5 (+ 1 AP) / 150 x 120cm /<br />

Image courtesy: The artist and Bob van Orsouw<br />

<strong>Gallery</strong>, Zurich<br />

18

Director’s foreword<br />

Tony Ellwood<br />

With each iteration since 1993, the Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary <strong>Art</strong> has taken on<br />

new and surprising forms. It remains the only major recurring exhibition in the world to<br />

maintain a focus on the contemporary art of Asia, Australia and the Pacific, and ‘The 6th Asia<br />

Pacific Triennial of Contemporary <strong>Art</strong>’ (APT6) reaches into a wider realm than ever before. It<br />

looks toward the dynamic region of West Asia and continues to explore the art of the Pacific.<br />

The exhibition includes more than 100 artists, many from countries which have never before<br />

featured in a Triennial: Tibet, North Korea (DPRK), Turkey and Iran, and countries of the Mekong<br />

region, such as Cambodia and Myanmar (Burma).<br />

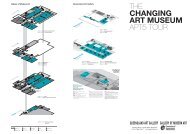

The last Triennial in 2006 marked the launch of our second site, the <strong>Gallery</strong> of Modern <strong>Art</strong><br />

(GoMA). This time, the Triennial occupies this wonderful building in its entirety, along with the<br />

<strong>Queensland</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong>’s iconic Watermall and adjoining galleries. The exhibition series has<br />

introduced many artists to Australian audiences, and this, of course, continues with APT6.<br />

An event of this scale will naturally strain at the bonds of any overarching themes, however, APT6<br />

has, at its core, a long-held interest in collaboration, interconnectivity and cross-disciplinary<br />

practice. This is expressed in many ways, from close partnerships between artists to larger scale<br />

and less predictable forms of connection and collaboration.<br />

Zhu Weibing<br />

China b.1971<br />

Ji Wenyu<br />

China b.1959<br />

People holding flowers (detail) 2007<br />

Synthetic polymer paint on resin; velour, steel<br />

wire, dacron, lodestone and cotton / 400 pieces:<br />

100 x 18 x 8cm (each) / Installed dimensions variable /<br />

The Kenneth and Yasuko Myer Collection<br />

of Contemporary Asian <strong>Art</strong>. Purchased 2008 with<br />

funds from Michael Simcha Baevski through the<br />

<strong>Queensland</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong> Foundation / Collection:<br />

<strong>Queensland</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong><br />

Three major multi-artist projects examine some of these themes, and have been coordinated<br />

in collaboration with co-curators working in the field. Focusing on artists working in the Mekong<br />

River region of South-East Asia, The Mekong is an ambitious consideration of art from Vietnam,<br />

Cambodia, Thailand and Myanmar. Another multi-artist project, Pacific Reggae: Roots Beyond<br />

the Reef, continues the Triennial’s engagement with the contemporary culture of the Pacific,<br />

in this case revealing reggae music’s responsiveness to influences of location and technology,<br />

and the genre’s ability to adapt from Jamaica to the Pacific. The third project presents a major<br />

display of works, in a variety of media, from North Korea (DPRK). A central component is a<br />

group of new works from the Mansudae <strong>Art</strong> Studio in Pyongyang. These works, including loans<br />

from a key private collection, will be seen in Australia for the first time.<br />

Three exceptional filmmakers — Ang Lee, Takeshi Kitano and Rithy Panh — are profiled as<br />

APT6 artists with retrospective seasons during the exhibition. The Australian Cinémathèque<br />

also presents two cinema projects, Promised Lands and The Cypress and the Crow: 50 years<br />

of Iranian Animation, presenting contemporary cinema reaching from the Indian subcontinent<br />

to West Asia and the Middle East.<br />

The APT has, since its inception, played a leading role in the development of the <strong>Gallery</strong>’s<br />

contemporary Asian and Pacific collections. The value of this was demonstrated earlier this<br />

21

year through ‘The China Project’, a three-part exhibition which provided a fresh context for the<br />

contemporary Chinese collection and included many acquisitions from previous APTs. Further<br />

acquisitions will be made from this Triennial, continuing the <strong>Gallery</strong>’s long-term commitment to<br />

the art of the region and building on its internationally significant collections.<br />

I gratefully acknowledge the continuing support of the Triennial’s Founding Supporter, the<br />

<strong>Queensland</strong> <strong>Government</strong>, whose unwavering commitment to this series has been essential<br />

to its ambition and achievements. I welcome Santos as the Presenting Sponsor of APT6.<br />

Santos also sponsors the <strong>Gallery</strong>’s Children’s <strong>Art</strong> Centre, and I look forward to working together<br />

in this important new relationship. I also express our gratitude to the Australian <strong>Government</strong>,<br />

which provides support through the Australia Council and the Visual <strong>Art</strong>s and Craft Strategy,<br />

an initiative of the Australian, State and Territory governments. Visual <strong>Art</strong>s and Craft Strategy<br />

funds, administered by <strong>Art</strong>s <strong>Queensland</strong>, also support a regional program of the Triennial,<br />

which has included the travelling exhibition ‘Frame by Frame: Asia Pacific <strong>Art</strong>ists on Tour’<br />

(2008–10). This exhibition presents works from the <strong>Gallery</strong>’s Asian and Pacific collections at<br />

eight <strong>Queensland</strong> venues.<br />

I wish to thank the Triennial’s Principal Benefactor, the Tim Fairfax Family Foundation, which has<br />

generously supported Kids’ APT. I also acknowledge and thank the exhibition’s Major Sponsors —<br />

Industrea Limited, Ishibashi Foundation and the <strong>Gallery</strong>’s Chairman’s Circle — as well as the many<br />

media and tourism partners, cultural bodies, foundations and supporters, whose contributions<br />

are greatly valued. The <strong>Gallery</strong> is also extremely grateful to the many lenders to the exhibition.<br />

Thanks to all the <strong>Queensland</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong> staff who have contributed to this Triennial, and also to<br />

the co-curators who have collaborated with us. Finally, I thank the artists for their work, and their<br />

generous and enthusiastic support. The APT series has always depended on an extraordinary<br />

network of close and enduring relationships with the participating artists. In fact, these<br />

relationships are the foundation on which the Triennial’s achievements rest. The <strong>Gallery</strong>’s staff<br />

are privileged and honoured to work with the participating artists, and I trust you will enjoy their<br />

outstanding works in ‘The 6th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary <strong>Art</strong>’.<br />

Subodh Gupta<br />

India b.1964<br />

The other thing 2005–06<br />

Steel structure, plastic, stainless steel tongs /<br />

206 x 211 x 63.5cm / The Lekha and Anupam Poddar<br />

Collection / Image courtesy: The artist and the Devi<br />

<strong>Art</strong> Foundation, Gurgaon<br />

22 23

A restless subject 1<br />

Suhanya Raffel<br />

The anthology What Makes a Great Exhibition? opens with an essay by the curator Robert Storr.<br />

He begins with the following words:<br />

It is customary in writing about what curators do to use the singular noun exhibition to cover<br />

what is in fact a plural category. From this, much confusion ensues in the experience and the<br />

judgment of the public. Rather than one form, exhibitions take many, some more, some less<br />

appropriate to their timing, their situation, their audience, and above all their contents. None of<br />

them is ideal and none exhausts the potential meanings of important art. A good exhibition is<br />

never the last word on its subject. 2<br />

The Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary <strong>Art</strong> (APT) is an ongoing project initiated in 1993.<br />

It is one of very few regularly recurring international exhibitions with a declared interest in a<br />

specific region; it addresses culture and ethnicity and acknowledges historical diasporas. It is<br />

also one of the rare series sustained within a museum context. With every exhibition since the<br />

first, the APT has been the subject of much discussion and debate in the art world and it has<br />

developed a large, dedicated audience. Its uniqueness, asserted through geography, provides<br />

structure and agency.<br />

Today, one of the most prominent ways of seeing contemporary international visual art en<br />

masse is via the biennale or triennial platform. These exhibitions are characterised by their<br />

scale, together with an understanding by artists, curators, educators, administrators, funding<br />

agencies and audiences that they offer a distinct perspective on the cultural life of a particular<br />

place. They provide evidence of cosmopolitanism and a ground for the exploration of ideas; are<br />

platforms for dialogue; and advocate a range of intellectual, political, aesthetic and otherwise<br />

‘artistic’ views. They are also an important means of bringing a broad range of international<br />

contemporary art to local audiences who would otherwise not have the opportunity to see<br />

such work. They have bloomed across the world, multiplying most recently in places where art<br />

infrastructure is less established, particularly in Asia, thus allowing for a decentralised viewing<br />

of contemporary art. As the curator and critic Hou Hanru recently commented: ‘biennales are<br />

really the most intense moments we see in the art world’. 3<br />

It is interesting that most of the best regarded of these events are not staged in the major art<br />

capitals of London, New York or Tokyo, but rather in Kassel, Brisbane, Gwangju, São Paulo and<br />

Havana. These towns and cities provide a critical level of population, infrastructure and interest,<br />

at a scale that is not suffocating, yet big enough to present an international event that allows<br />

for both a physical space that is open and accommodating, and a conceptual space that is<br />

curious and engaging.<br />

Shirana Shahbazi<br />

Iran/Switzerland b.1974<br />

In collaboration with Sirous Shaghaghi, Iran<br />

Sirous Shaghaghi painting Still life: Coconut and<br />

other things 2009 in his studio, Tehran<br />

Commissioned for APT6 / Image courtesy:<br />

The artist / Photograph: Roozbeh Tazhibi<br />

24 25

The curatorial structure of the inaugural APT laid the groundwork for subsequent events.<br />

It eschewed the auteur in favour of a multitude of voices, initially because it was a pragmatic<br />

way of both engaging and reflecting the diverse cultures of the region. The structure was built<br />

around <strong>Queensland</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong> staff working with curatorial partners in different countries.<br />

As <strong>Gallery</strong> expertise grew, this model evolved into an internal <strong>Gallery</strong> curatorial team seeking<br />

advice from curatorial colleagues and artists abroad and at home.<br />

In these two unique ways — regional specificity and no single directorial voice — the APT differs<br />

from other biennales and triennials. Importantly, it also provides opportunities for artists from<br />

the region to have external critical perspectives brought to their work. The APT advocates for<br />

decentralised positions, and was one of the first in this part of the world to concentrate and<br />

frame its ‘looking’ via this geography. Why is this important? It is an assertion that the work<br />

of artists from Asia and the Pacific be presented in a regional context within the international<br />

framework of the triennial. This productive focus offers significant perspectives generated by<br />

privileging location. As independent curator and publisher Sharmini Pereira notes:<br />

Even if an ambition to foster a world art history guided early APTs, its subsequent incarnations<br />

have highlighted the impossibility of such an enterprise. Defining itself in relation to Asia and<br />

the Pacific, the APT is, by choice, not geared to encompass a world art history. Through its<br />

exclusive regional focus, it has not only made a phenomenal contribution to cultural debates<br />

internationally but has provided rumination on problems of canons and linear narratives. 4<br />

With every APT the definition of the region is tested. APT6 includes the work of artists from Iran<br />

and Turkey for the first time, with the major thematic cinema program Promised Lands exploring<br />

the rich cultures of the Indian subcontinent through to West Asia and the Middle East. Looking<br />

to the immediate west was first mooted by a number of Indian and Pakistani artist and curator<br />

colleagues who, when talking about their own practices, would often frame discussion around<br />

Tracey Moffatt<br />

Australia/United States b.1960<br />

Gary Hillberg<br />

Australia b.1952<br />

OTHER (stills) 2009<br />

DVD transferred to Digital Betacam, single channel<br />

projection, continuous loop, colour, sound,<br />

7:00 minutes, ed. 1/150 / Courtesy: The artists<br />

Kyong Sik<br />

North Korea (DPRK) b. unknown<br />

The high-speed construction unit 1988<br />

Linocut on paper / 59.5cm x 72cm /<br />

Collection: Nicholas Bonner, Beijing<br />

Jae Yong<br />

North Korea (DPRK) b. unknown<br />

Untitled 1964<br />

Watercolour on paper / 26 x 19cm /<br />

Collection: Nicholas Bonner, Beijing<br />

the complex exchange of artistic and cultural ideas from the Middle East, especially Islamic art.<br />

It is, in fact, a natural extension, and allows us to acknowledge the considerable influence that<br />

Islamic art and culture have across the region.<br />

Also included for the first time is a presentation of work from North Korea (DPRK). Working with<br />

Beijing-based British filmmaker Nicholas Bonner as co-curator, the discussion about showing art<br />

from North Korea began in early 2005. Given Bonner’s long-term relationships with artists and<br />

filmmakers in the DPRK, the 13 commissions at the heart of the display have been developed in<br />

close consultation with the artists from the Mansudae <strong>Art</strong> Studio, the curators and the <strong>Gallery</strong>.<br />

One clear aim of the exhibition has been to challenge assumptions, and therefore broaden<br />

understanding about what contemporary art is. The APT consistently addresses how artists live<br />

and work in diverse conditions. One of the great contributions this exhibition makes to broader<br />

discussions about art is the recognition of different, parallel art histories that have developed in<br />

the region in locally specific ways. For example, the art historical canons cited in the works from<br />

the Mansudae <strong>Art</strong> Studio include the socialist realist styles that were imported from the Soviet<br />

Union and China as revolutionary artistic movements, a form also echoed in the iconography<br />

developed in trade union banners in Australia and the English Midlands. Yet, this is not the only<br />

stylistic influence. Brush-and-ink painting, or chosunhua, is still considered the most important<br />

art form in Korea due to its established place in East Asian art; this is also the case with oil<br />

painting, which has its roots in Europe and was most recently taught to Korean artists by the<br />

Japanese during the occupation from 1910 to 1945.<br />

Such a trajectory is in sharp contrast to the art history that octogenarian Iranian artist Monir<br />

Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian draws on in her dazzling mirror mosaic sculptures. The rich traditions<br />

that distinguish Islamic architecture are key influences. The geometric structures and the ordered<br />

repetition of patterns that were developed as an intrinsic aspect of Islamic shrine and temple<br />

26 27

Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian<br />

Iran b.1924<br />

Lightning for Neda (detail) 2009<br />

Mirror mosaic, reverse glass painting, plaster on wood /<br />

6 panels: 300 x 200cm (each) / Commissioned for APT6<br />

and the <strong>Queensland</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong> Collection. The artist<br />

dedicates this work to the loving memory of her late<br />

husband Dr Abolbashar Farmanfarmaian / Purchased<br />

2009. <strong>Queensland</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong> Foundation / Collection:<br />

<strong>Queensland</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong><br />

Opposite<br />

Pasifika Divas<br />

Shigeyuki Kihara in performance 2002<br />

Produced by Lisa Taouma and the <strong>Queensland</strong> <strong>Art</strong><br />

<strong>Gallery</strong> for APT 2002 / Photograph: Lukas Davidson<br />

architecture, dating from the seventh century to the present, have been inspirational to her work.<br />

But so too was the artist’s training in New York during the late 1940s, when she studied at the<br />

Parsons School of Design. She then spent 12 years living and working as a freelance designer for<br />

American Vogue magazine, and as a commercial artist and fashion designer for the department<br />

store Bonwit Teller. Her exposure to artist colleagues, gallerists and other art world luminaries<br />

at the time meant she observed the postwar flowering of the New York Avant-garde before<br />

returning to Iran in 1957. Working mostly instinctively, her shimmering works are testaments to<br />

modernist abstract principles as well as the purity of Islamic geometry.<br />

The one constant of the APT is dissonance. There is a certain impenetrability that such ‘noise’<br />

engenders. An ordered consonance is not possible when the framework demands such broad<br />

scope. The voice of the Pacific — and for APT6, it can literally be heard in the drop beat of Pacific<br />

reggae — adds yet another pitch. Looking back at past APTs, it has been the Pacific artists who<br />

have challenged the structure of ‘seeing’. Perhaps this is due to the nature of contemporary<br />

practice on the many hundreds of islands, which also includes indigenous art-making forms.<br />

The inclusion in APT6 of powerful customary objects by North Ambrymese sculptors<br />

from Vanuatu encourages us to focus on the historical process of artistic creation and the<br />

engagement with tradition. In these circumstances, the act of separating oral, performative<br />

and visual art practices is both unproductive and uncreative. Why persist when such canonical<br />

definitions are of no concern in the local contemporary context? The work of these artists<br />

readily challenges assumptions about the stability of definitions within contemporary art<br />

discourses in the museum.<br />

For artists to alter the museum space is not a new phenomenon. It has a longer history growing<br />

from the restless dissent of the 1960s and 1970s, when artists in the West focused their energies<br />

on testing the conventional relationships between artist, audience, museum and market. Museum<br />

director and writer Sandy Nairne describes the burgeoning history of these phenomena:<br />

28 29

publication. The discrete projects — such as The Mekong, Pacific Reggae: Roots Beyond the<br />

Reef, the works from North Korea (DPRK), and the thematic film programs — each concentrate<br />

on particular regions to present more in-depth perspectives on art history and contemporary<br />

ideas. For example, The Mekong uses the river as metaphor for the movement and exchange<br />

of knowledge. As Rich Streitmatter-Tran, co-curator of The Mekong states:<br />

The Mekong region is often referred to through a variety of organisational frameworks including<br />

historic–cultural areas, sociolinguistic zones, and by the borders of the nations themselves. It has<br />

always been a shifting territory — an ebb and flow of conflict and cooperation, modernisation<br />

and preservation, exploitation and conservation. Each struggle can be found documented in<br />

the arts, whether in historical artefact or in the contemporary work featured in APT6. 6<br />

There is always more to be said about contemporary art and art-making in Asia and the<br />

Pacific and, as we approach the second decade of this century, the economic, social, political<br />

and cultural dynamics of the region — and its relationships with the rest of the world — are<br />

more intense than ever. Every three years, the APT revisits this territory. Within Brisbane and<br />

internationally, this exhibition marks a point of concentration and deliberation valued by many.<br />

To return to Storr’s apt observation, ‘a good exhibition is never the last word on its subject’.<br />

The general term ‘space’ replaced the word gallery (alternate spaces followed after<br />

experimental galleries and laboratories) and was used precisely because it was supposed to<br />

avoid the connotations of an institutional or commercial environment, where a hierarchical,<br />

formal arrangement might determine audience behaviour in pre-set ways. ‘Space’ usefully<br />

removed the immediate connotations of commodity.<br />

If artists already had any ‘space’ it was because they had studios. And the connotations of<br />

studio activity had long passed from associations of the model and the arranged tableau to<br />

a less structured, process-oriented concept of the creative site. The new spaces in the early<br />

seventies were thus much less the laboratories of technological or participatory experiment<br />

than a self-consciously chaotic milieu (of which Warhol’s space of the Factory is a precursor),<br />

where gesture and incident could be prominent and pre-eminent. 5<br />

Endnotes<br />

1 I would like to acknowledge Runa Islam for her wonderful work The Restless Subject 2008, which effortlessly<br />

captures the complexities involved in the act of ‘seeing’.<br />

2 Robert Storr, ‘Show and tell’, in Paula Marincola (ed.), What Makes a Great Exhibition?, Philadelphia Exhibitions<br />

Initiative, Philadelphia, 2006, p.14.<br />

3 Hou Hanru, interviewed by Robert Leonard, ‘The biennale makers’, <strong>Art</strong> & Australia [APT6 special issue], December<br />

2009 [forthcoming].<br />

4 Sharmini Pereira, ‘The Asia Pacific Triennial: A forum’, in ‘21st century art history’, The Australian & New Zealand<br />

Journal of <strong>Art</strong>, vol.9, no.1/2, 2008–09, p.210.<br />

5 Sandy Nairne, ‘The institutionalization of dissent’, in Reesa Greenberg, Bruce W Ferguson and Sandy Nairne,<br />

Thinking about Exhibitions, Routledge, London, 1996, p.396.<br />

6 Rich Streitmatter-Tran, ‘Mapping the Mekong’, The 6th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary <strong>Art</strong> [exhibition<br />

catalogue], <strong>Queensland</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong>, Brisbane, 2009, p.128.<br />

I include this quote by way of arguing that, indirectly, the APT has had a similar influence on<br />

the art museum in which it takes place. The nature of art-making across the region is incredibly<br />

diverse and includes places with highly developed art infrastructures, as well as others with very<br />

limited foundations.<br />

Over the last two decades, the APT has shown the work of over 300 artists. In this context, it<br />

has introduced the work of little-known artists to Australia while also profiling artists with major<br />

international reputations, whose work is generally known through art publications rather than<br />

exhibitions staged in Brisbane. While APT6 presents work from places not previously included,<br />

the exhibition is built around artists from East Asia, South Asia, South-East Asia, Australia,<br />

the Pacific, as well as the diaspora, as it has from its inception. Thematic ideas — such as the<br />

significance of collaborative practice and the perspectives offered in the inclusion of the two<br />

major film programs, Promised Lands and The Cypress and the Crow: 50 Years of Iranian<br />

Animation — are integral to the APT, and are discussed in the other overview essays in this<br />

Simeon Simix<br />

Vanuatu b.1981<br />

Paw paw/coconut (from ‘Bebellic’ portfolio) 2007<br />

Screenprint on magnani paper ed. 1/45 / 76 x 56cm /<br />

Purchased 2008. <strong>Queensland</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong> Foundation /<br />

Collection: <strong>Queensland</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong><br />

Vandy Rattana<br />

Cambodia b.1980<br />

Fire of the year 5 2008<br />

Digital print / 105.5 x 63.5cm / Image courtesy:<br />

The artist<br />

30 31

Rites and rights: Contemporary Pacific<br />

Maud Page<br />

Leba Toki recently planted taro in the lush, terraced gardens of the Shrine of the Bab in Haifa,<br />

Israel, a place of worship dedicated to Bahá’ulláh, the Persian founder of the Bahá’Í faith that<br />

she follows. The experience of adding something from her own Fijian soil to a place already<br />

imbued with so many symbols of unity and understanding provided the genesis for the work<br />

Teitei vou (A new garden) 2009, produced in collaboration with New Zealand artist Robin White<br />

and renowned masi (Fijian barkcloth) artist Bale Jione. But this is a mistranslation of Leba’s<br />

account — formulating only a literal reading of the trio’s complex and poetic artistic process.<br />

Rather, every time the three artists added another motif to their four-metre barkcloth they<br />

saw it as planting — pushing the ink through the fibrous layers of masi with their fingertips, the<br />

remnants of the ink remaining, like earth underneath fingernails. Taro was one of the first things<br />

they ‘planted’ in their garden, followed by sugarcane, pineapples and orange trees. 1<br />

Exhibiting art works that are still functional objects or that are derived from customary<br />

practices, such as Teitei vou (A new garden), opens a number of dialogues that the Asia Pacific<br />

Triennials have been exploring for some time. These conversations are both rewarding, in<br />

that they broaden interpretive possibilities, and fraught, as they highlight the disjunctures<br />

and mistranslations of our comfort zone. Curator Okwui Enwezor, however, warns against the<br />

romantic idea that there will always be a ‘misunderstanding when you take on the work of other<br />

cultures. These do happen, but those misunderstandings can never be addressed unless you<br />

make an attempt’. 2 The APT is the only series of exhibitions to systematically engage with the art<br />

of the Pacific region and interject it within that of a very prolific Asia. This is a discursive act.<br />

This APT presents eight artists/collectives from the Pacific, including New Zealand. It has a<br />

particular interest in the cultural expressions of Vanuatu, showing customary sculptures from<br />

North Ambrym alongside prints made by a group of young Port Vila-based artists, as well as the<br />

music of the region in Pacific Reggae: Roots Beyond the Reef. These three examples provide an<br />

insight into ni-Vanuatuans’ engagement with modernity and history. In varying degrees, all draw<br />

on customary practices, with artists continuing to use selected customary elements or altering<br />

them to suit present needs and ideas.<br />

Teitei vou (A new garden) also addresses these concerns by using barkcloth and the traditional<br />

rites of Fijian marriage as a starting point. This installation explores the narratives relating to the<br />

artists’ shared Bahá’Í faith, Toki and Jione’s Fijian material culture, and the difficulties of living<br />

in a politically turbulent Fiji. The large Lautoka sugar mill dominating this town’s landscape is<br />

repeated as a pattern on the taunamu (masi screen), for example, recalling over 100 years of<br />

indentured Indian labour. Alongside these depictions, which include the symbols of major<br />

world religions together with jackals and crows, are also patterns specific to the Moce area from<br />

where Toki and Jione originate. In Teitei vou (A new garden), the artists have assembled and<br />

Robin White<br />

New Zealand b.1946<br />

Leba Toki<br />

Fiji b.1951<br />

Bale Jione<br />

Fiji b.1952<br />

Taunamu from Teitei vou (A new garden) (detail) 2009<br />

Natural dyes on barkcloth / 390 x 240cm / Purchased<br />

2009. <strong>Queensland</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong> Foundation Grant /<br />

Collection: <strong>Queensland</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong><br />

32 33

added to a number of customary practices. Taunamu are traditionally used as screens during<br />

wedding ceremonies. Although in recent times they have begun to feature family names, the<br />

patterns and formation of the masi have remained relatively constant over centuries. Similarly,<br />

the ibe vakabati (wool-fringed mat), that features a lotus flower surrounded by the Fijian<br />

sandalwood vine, in the past would likely have displayed colourful geometric designs. 3 To these<br />

transformed works, Toki, White and Jione have added two fabric mats to be placed on the masi<br />

where the couple would stand. These mats, featuring remnants of wedding saris sewn with strips<br />

of masi, were inspired by the work of Toki’s Indo–Fijian neighbours. The artists have chosen an<br />

installation rich in hope and cultural symbolism and, through their Bahá’Í faith, they call for the<br />

peaceful transformation of their society, which is imaged in exquisite detail in this work.<br />

Teitei vou (A new garden) is an example of how customary works convey artists’ alternative ideas<br />

about their locale, or how they allow them to interact differently with their own rites. The desire<br />

to communicate, and ensuing artistic change, facilitates the dialogue between customary-based<br />

and contemporary works. Customary-inspired works have been included in past APTs, most<br />

notably the ornate clay relief structures of the Indian artist Sonabai in APT3 (1999). The Rajwar<br />

community, to which Sonabai belongs, transform their homes with elaborate decorations and<br />

painted clay figures for the post-harvest festival of chherta. Sonabai came to international<br />

attention when she developed a style inimitable to the women in her village, by creating figures<br />

exploring different sculptural possibilities. Her inclusion in APT3 was a strong statement based<br />

on the questioning of definitions of contemporary art, revealing the porosity of art historical<br />

classifications and binding her practice to those that recognise different art histories.<br />

The fifth APT in 2006 featured the Pacific Textiles Project, which demonstrated the use of textiles<br />

across the South Pacific as a way of conveying narratives of religion and nationhood; in the past,<br />

they were largely devoid of imagery and text. These textiles are still being used in the same<br />

life-changing ceremonies as their forebears, but now use alternative materials, such as wool and<br />

cotton, to weave new ideas. The embroideries, which include the words ‘happy birthday’, the<br />

names of family members or bright depictions of biblical stories, circulate only within their own<br />

communities, travelling far only when accompanying members of the diaspora to their other<br />

homes. Consequently, they have not often found their way into exhibitions or the art market.<br />

The artist Sonabai creating her work Untitled in Brisbane<br />

for ‘The Third Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary <strong>Art</strong>’,<br />

<strong>Queensland</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong>, 1999 / Photograph: Ray Fulton<br />

The Pacific Textiles Project installed at ‘The 5th Asia<br />

Pacific Triennial of Contemporary <strong>Art</strong>’, <strong>Queensland</strong> <strong>Art</strong><br />

<strong>Gallery</strong>, 2006 / Photograph: Natasha Harth<br />

Robin White<br />

Leba Toki<br />

Bale Jione<br />

Teitei vou (A new garden) (work in progress) 2009<br />

Taunamu from Teitei vou (A new garden) (detail) 2009<br />

Natural dyes on barkcloth / Purchased 2009.<br />

<strong>Queensland</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong> Foundation Grant /<br />

Collection: <strong>Queensland</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong><br />

This type of work raises a number of issues — the altering of customary practice is sometimes<br />

perceived as merely derivative of the original; the authenticity of tradition somehow maintains a<br />

cultural purity which is stronger and more valued, particularly by the tribal art market. Similarly,<br />

customary work, whether used as a departure point for new work or not, is often not considered<br />

to be contemporary art, and is therefore excluded from international platforms. 4 This important<br />

and ongoing discussion also concerns contemporary Australian Aboriginal art.<br />

34 35

The visibility and success of Aboriginal art has transformed the way Australians understand<br />

modern and contemporary art. Its diversity of practice, strong formalist sensibility and inclusion<br />

of customary objects as part of its ambit have created productive dialogues, some of which also<br />

inform contemporary Pacific art. Awkward divisions between art and craft, secular and ritual,<br />

and urban and remote have slowly become less rigid, allowing for a far richer appreciation of<br />

what constitutes Aboriginal creativity. The fact that audiences are able to see such a diversity<br />

of practice allows non-traditional media, such as fibre art, for example, to be critically explored,<br />

while the accompanying debate continues. 5 Most recently, the academic Ian McLean has<br />

sought to historicise Central Australian Aboriginal art practice, arguing for a more critically<br />

engaged view, and allowing for alternative modernisms within the art historical canon:<br />

The fear that applying theories of the modern to remote Aboriginal art will assimilate its<br />

differences into Eurocentric concerns is paternalistic and ignores the ways in which Aboriginals<br />

have, since the time of first contact, readily sought to translate and assimilate and use the<br />

cultural products of modernity. 6<br />

Sometimes, as is the case for the sculptures from Vanuatu shown here in APT6, novelty and<br />

artistic autonomy are not readily apparent. Consisting of a number of mague (ranking black<br />

palm figures), temar ne ari (ancestor spirit figures), atingting (slit drums) and guardian of tabou<br />

house figures, the grouping invites comparison. Yet, what is more rewarding, and as Ruth<br />

McDougall explains, is a historical account of how these practices have adapted and changed<br />

to suit the needs and artistic impetuses of the community who makes them. 7 Ambrymese<br />

carvers’ translations of a number of stylistic, as well as actual, rites from the neighbouring island<br />

of Malakula occurred over a long period of time, and were the result of complex inter-island<br />

canoe trading and intermarriage.<br />

Although house paints have mostly replaced natural pigments and ochres (except in the case<br />

of the guardian of tabou house figures), according to anthropologist Kirk Huffman: ‘influences<br />

from the white man’s world have had very little stylistic effect on the art styles on Ambrym’. 8<br />

Covering the torso of a temar figure we see a fluorescent green; previously derived from a<br />

particular moss it is now conveniently available in acrylic. This vivid hue, combined with the<br />

ancestors’ red markings on a white face, forms a striking representation. 9<br />

As part of the group of black palm figures is a selection of mague that feature a more<br />

experimental use of paint. Many have bright blue and lime fish forms which appear to emerge<br />

from the figures’ mouths, their noses and crescent-shaped eyes often contoured in bright pink.<br />

One of the figures is said to feature the receding hairline of the man who commissioned it. 10<br />

This design (if it does not already belong to somebody else) is now governed by copyright,<br />

and other makers will have to negotiate its future use. Such a system — infinitely more complex<br />

than that conveyed — can be seen as an impetus for constant invention, yet the practice of<br />

all four types of carving has not dramatically altered over time, suggesting that Ambrymese<br />

artistic interests and priorities lie elsewhere. These probably do not conform to Western ideas<br />

of artistic production or evolution; however, we can surmise that the visibility of these art forms<br />

outside Ambrym — whether on the streets of the capital of Port Vila, which are lined with black<br />

palm ranking figures, or in Australia and Europe — will lead to further developments. Indeed,<br />

there may be a commercialisation of these objects, which, as Ian McLean so cogently argues in<br />

terms of Australian Aboriginal art, does not necessarily mean it will be to the detriment of the<br />

works and the rites accompanying them.<br />

Mansak Family<br />

Vanuatu b.unknown<br />

Temar ne ari (ancestor spirit) c.1995<br />

Natural fibres, clay, synthetic polymer paint, ochres,<br />

coconut shells, bamboo and sticks / 145 x 50 x 25cm /<br />

Purchased 2008. The <strong>Queensland</strong> <strong>Government</strong>’s<br />

<strong>Gallery</strong> of Modern <strong>Art</strong> Acquisitions Fund /<br />

Collection: <strong>Queensland</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong><br />

Michel Rangie<br />

Vanuatu b.c.1981<br />

Mague ne sagran (ranking black palm) grade 4 painted<br />

c.2005<br />

Carved black palm with synthetic polymer paint /<br />

195 x 38 x 48cm / Gift of David Baker through the<br />

<strong>Queensland</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong> Foundation 2008 /<br />

Collection: <strong>Queensland</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong><br />

36 37

Kava street sign, Mataso-Ohlen, Port Vila, Vanuatu 2007<br />

Photograph: Newell Harry<br />

Opposite<br />

Herveline Lité<br />

Vanuatu b.1980<br />

Le pigeon de Mataso (from ‘Bebellic’ portfolio) 2007<br />

Screenprint on magnani paper ed. 1/45 / 76 x 56cm /<br />

Purchased 2008. <strong>Queensland</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong> Foundation /<br />

Collection: <strong>Queensland</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong><br />

The archipelago of Vanuatu has been contested by Western countries and markets for over a<br />

century. It was governed by a British–French condominium from 1906 until its independence<br />

in 1980, and has therefore been far from isolated, having to variously adapt and resist. Under<br />

international pressure, Vanuatu began to redress its tax haven status in 2008. The influx of<br />

foreign money has brought with it many changes, primarily in Port Vila and the island of Efate,<br />

with the selling of land for beef farming and tourism. These industries demand a certain level of<br />

labour to sustain them and, when combined with a lack of opportunity outside of subsistence<br />

practices, have caused an influx of people from the outer islands to Port Vila. For example,<br />

most of the population of the small island of Mataso, which lies off the northern tip of Efate,<br />

has relocated to Ohlen, a shantytown on the outskirts of Port Vila. It is from here, with only a<br />

few fluorescent lights overhead, that a number of young men and women have created a bold,<br />

simple and effective series of drawings (subsequently transformed into prints in Australia) as<br />

a response to their changing daily environment; their primary inspiration derived from their<br />

encounters with advertising signage promoting food, beverages and commercial products in<br />

the capital. David Kolin’s drawing of a lion, with the speech bubble text ‘Mi laekem kae kaeman’,<br />

which translates as ‘I like to eat man’, is a humorous response to the viewing of National<br />

Geographic magazines showing African fauna.<br />

Some of the artists also draw on their cultural heritage, like Herveline Lité who comes from<br />

the island of Malakula, where sand-drawing is prevalent. 11 Her vibrant blue work features<br />

a compartmentalised design comprised of rectilinear and circular motifs. In this work, Lité<br />

references a large natural rock lying four kilometres off the coast of Mataso, which is a<br />

favourite fishing location for villagers. It was also used for target practice by United States Navy<br />

personnel during World War Two and, over time, the holes in the monolithic rock face have<br />

served as nesting spots for pigeons which are hunted every spring. The soldiers’ presence on<br />

the islands is still very visible through the abandoned machinery and army barracks, and the<br />

glass Coke bottles peppering Efate’s north coast shoreline.<br />

In contrast, a more sombre, and ultimately violent, act which occurred on the Vanuatu coast<br />

in the late nineteenth century was the practice of ‘blackbirding’. Between the 1860s and early<br />

1900s, ni-Vanuatuans (amongst other Melanesians and some Polynesians) were kidnapped to<br />

work on sugar plantations in <strong>Queensland</strong> and Fiji. 12 This ‘recruitment’ preceded that of Indian<br />

indentured labour and is addressed in Teitei vou (A new garden).<br />

Marcel (Mars Melto) Meltherorong, a prominent ni-Vanuatuan singer–songwriter, recently<br />

composed a reggae song with Georgia Corowa called ‘Slavaland’, lamenting the taking of<br />

their forefathers. The song ends with the lyric: ‘Melanesians, Polynesians and Micronesians are<br />

coming, you better be ready!’. No music seems more suited to melding storytelling with a call<br />

38 39

tok pisin (Papuan pidgin) to a Tahitian (Polynesian) audience who then sing the chorus to him —<br />

but perhaps this is simply due to this pan-Pacific star’s charisma and catchy tunes. Whatever the<br />

reason, Pacific reggae is traversing this ‘one saltwater’, creating a multitude of narratives about<br />

a region and a people who ‘stand up for their rights’ and who confront social, political and<br />

environmental issues when needed, but which also promotes the things that strengthen in the<br />

face of adversity — community, family and, of course, romance.<br />

Together, projects such as these continue to build on a conversation with the people of the<br />

Pacific that began in 1993 with the first APT, but which is now also maintained through this<br />

<strong>Gallery</strong>’s collecting practices and exhibition programming. 16 This dialogue is liberating for its<br />

open-endedness.<br />

for social consciousness than reggae. Across one third of the world’s surface, Pacific people<br />

come together to make reggae, continuing an oral history, regardless of what is happening<br />

outside the ‘one saltwater’. 13 Today, Pacific reggae is flourishing; musicians travel throughout<br />

the region to perform in concerts and festivals, such as the annual Fest’Napuan festival, which<br />

began in 1996, and where, on a large outdoor stage on the lawns of the Vanuatu Cultural<br />

Centre, musicians play to crowds gathered in their thousands.<br />

Pacific Reggae: Roots Beyond the Reef, co-curated with Brent Clough, brings together reggae<br />

artists from Hawai’i, New Zealand, Australia and Melanesia. It presents their unique approaches<br />

to this music genre which originated in Jamaica. Through video clips, playlists, interviews,<br />

documentaries and live performances, the project shows how reggae is one of the Pacific’s<br />

most valued means of communication. As Clough argues, reggae is used by many in these<br />

island nations to highlight the political and social problems that are often ignored due to the<br />

promotion of tourism-related language and images. 14<br />

For reggae, the language of choice is principally a local form of pidgin. Melanesian pidgin<br />

(Hawai’i has its own) arose in the nineteenth century, when Europeans were harvesting and<br />

trading sandalwood and sea cucumbers (known as bêche-de-mer in French), and had to<br />

develop a common form of communication. It was primarily during the ‘blackbirding’ period,<br />

however, that Melanesian men developed pidgin as a communicative tool of survival used<br />

between themselves and the overseers. Those men who returned to their own countries<br />

continued using pidgin when working with foreigners, and the language proliferated. The form<br />

of pidgin in Vanuatu is Bislama (derived from the phonetic bêche-de-mer), and is now one<br />

of the archipelago’s official languages, with ni-Vanuatuans also speaking English and French,<br />

as well as a number of their own vernacular languages. 15 Although pidgin languages across<br />

Melanesia have developed their own lexicons, for the most part they are widely understood.<br />

This doesn’t explain how the blond-dreadlocked, Papuan-raised O-shen can sing ‘Meri Lewa’ in<br />

26 Roots at home in Espíritu Santo, Vanuatu<br />

Photograph: Dan Cole<br />

Endnotes<br />

1 Robin White: ‘For us — especially for Leba and Bale — it was a way of signalling our presence in that place, as well<br />

as representing the idea of growth . . . and the process of growth . . . it’s really about people and about growing<br />

communities’. Email to the author, 14 October 2009.<br />

2 Okwui Enwezor, ‘Curating beyond the canon’, in Paul O’Neill (ed.), Curating Subjects, Open Editions, London,<br />

2007, p.119.<br />

3 See the Pacific Textiles Project featured in APT5, which displayed ibe vakabati as well as cloth textiles.<br />

4 See Nicholas Thomas, ‘Our history is written in our mats’, in The 5th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary <strong>Art</strong><br />

[exhibition catalogue], <strong>Queensland</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong>, Brisbane, 2006, pp.24–31.<br />

5 Refer to the work of, but not exclusively, Marcia Langton, Ian McLean and Nicholas Thomas.<br />

6 Ian McLean, ‘Aboriginal Modernism in Central Australia’, in Kobena Mercer (ed.), Exiles, Diasporas and Strangers,<br />

Iniva and MIT Press, London, 2008, p.75.<br />

7 Ruth McDougall, ‘Vanuatu sculptors: Innovation and tradition’, in The 6th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary<br />

<strong>Art</strong> [exhibition catalogue], <strong>Queensland</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong>, Brisbane, 2009, pp.188–91.<br />

8 Kirk Huffman, ‘Sacred pigs to Picasso. Vanuatu art in the traditional and “modern” worlds’, <strong>Art</strong> and Australia,<br />

vol.46, no.3, 2009, p.476.<br />

9 Huffman also recounts that, as far back as the nineteenth century, the Ambrymese had discovered that the<br />

laundry bleaching solution Reckitt’s Blue when left to dry, then mixed, formed a brilliant ultramarine colour, which<br />

is echoed in much of the mague figures’ colouration. See Huffman, p.476.<br />

10 As relayed to the author by David Baker, the donor of this group of works.<br />

11 Called ‘sandroing’ locally; a key feature of this visual form of communication is that motifs are drawn directly<br />

onto the sand in one single movement.<br />

12 South Sea Islanders are the Australian descendants of these ‘blackbirded’ men and women.<br />

13 Marcel ‘Mars Melto’ Meltherorong video interview with the author, 6 July 2009, as featured in Pacific Reggae:<br />

Roots Beyond the Reef for APT6.<br />

14 Brent Clough, ‘Pacific Reggae: Roots Beyond the Reef’, in The 6th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary <strong>Art</strong><br />

[exhibition catalogue], <strong>Queensland</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong>, Brisbane, 2009, pp.160–3.<br />

15 For example, the national anthem is in Bislama, and there are over 100 vernacular languages in Vanuatu.<br />

16 Most recently, and running concurrently with APT6, is the exhibition ‘Paperskin: Barkcloth across the Pacific’,<br />

a collaboration involving the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, the <strong>Queensland</strong> Museum and the<br />

<strong>Queensland</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong>.<br />

40 41

Promised lands<br />

Jose Da Silva and Kathryn Weir<br />

Yael Bartana’s video A Declaration 2006 opens with a man rowing in the Mediterranean Sea.<br />

He anchors alongside Andromeda’s Rock in Jaffa Harbor, where he substitutes the Israeli flag<br />

planted on the rock with an olive tree. Seen within the context of Israeli–Palestinian relations,<br />

the man’s actions are a bold intervention into the territory staked by the flag. The olive tree’s<br />

symbolic resonance also imbues the gesture with sacred significance, representing not only<br />

a peace offering and a call for an end to conflict, but also a celebration of strength and the<br />

capacity for renewal. Promised Lands, a major cinema project for APT6, features artists and<br />

filmmakers who similarly find opportunities to rethink the past and imagine the future. As in<br />

Bartana’s poetic statement, their work draws on the historical roots of contemporary experience,<br />

bringing the past to life in the present to transform our understanding of then and now.<br />

Promised Lands profiles cinematic and geopolitical relationships throughout the Indian<br />

subcontinent (Bangladesh, India, Kashmir, Pakistan, Sri Lanka) and across to West Asia and the<br />

Middle East (including Afghanistan, Armenia, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Kurdistan, Lebanon, Palestine<br />

and Turkey). In the context of the APT, which seeks to question the cultural and geographical<br />

frameworks of the Asia Pacific region, Promised Lands offers an opportunity to open up a<br />

deeper conversation with West Asia and the Middle East. This discussion underlines the need<br />

for a more specific awareness of distinct histories and genealogies within these regions, while<br />

also acknowledging interactions and shared influences across borders. Through the process<br />

of bringing political geographies and histories into question, the opportunity arises to reflect<br />

on how the region’s complex and diverse cultures and artistic practices contribute to new and<br />

more nuanced understandings of ‘Asia’.<br />

Promised Lands includes five programs of film and video that consider local politics and<br />

individual lives within a larger context. Each program has an autonomous curatorial framework:<br />

responses to civil war in Sri Lanka (The Road to Jaffna); the legacies of partition across the<br />

Indian subcontinent (Cinema of Partition); dissent and the affirmation of cultural identity<br />

in a climate of political intervention in West Asia, as well as the fraught nexus of religious<br />

fundamentalism and national politics (The Tree of Life); the traumatic histories linking Armenia<br />

and Turkey (Return of the Poet); and fault lines throughout the Middle East in response to<br />

conflict and territorial incursions in Israel, Palestine and Lebanon (Eating My Heart). Several<br />

broad themes appear across these strands, in particular the intersection of daily life with<br />

relationships to land, religious affiliations and cultural histories.<br />

<strong>Art</strong>ists and filmmakers across the Indian subcontinent have given expression to the<br />

consequences of partitioning British India into the states of India and Pakistan following<br />

the country’s independence from colonial rule in 1947. This imposed geographic division<br />

along religious lines caused profound physical, social and emotional scars for Muslim, Hindu,<br />

Mahmoud al Massad<br />

Jordan b.1969<br />

Production still from Ea’ Adat Khalk (Recycle) 2007 /<br />

HD video, colour, Dolby SR, 78 minutes, Netherlands/<br />

Jordan, Arabic (English subtitles) / Image courtesy:<br />

Wide Management, Paris<br />

42

Vimukthi Jayasundara<br />

Sri Lanka b.1977<br />

Production still from Sulanga Enu Pinisa (The Forsaken<br />

Land) 2005 / 35mm, colour, Dolby SR, 108 minutes,<br />

Sri Lanka/France, Sinhala (English subtitles) / Image<br />

courtesy: Unlimited Films, Paris<br />

Sarah Singh<br />

India b.1971<br />

Production still from The Sky Below 2007 / Digital video,<br />

black and white and colour, stereo, 76 minutes, India/<br />

Pakistan, Urdu/Hindi/English/Punjab/Sindhi/Kashmiri<br />

(English subtitles) / Image courtesy: The artist<br />

Christian and Sikh communities that are still carried in the region today. Large-scale border<br />

crossings and emigration occurred in attempts to flee conflict, intolerance and economic<br />

hardship, and individual and collective identities were subject to media and political<br />

manipulation. East Pakistan, which would become Bangladesh after the Liberation War of 1971,<br />

also suffered economically and culturally when it was separated from the rest of Bengal, and the<br />

exodus to the wealthy emirates of the Persian Gulf that began at this time continues today.<br />

Filmmakers working in India after partition have attempted to address what had been repressed<br />

through fear of further conflict. Ritwik Ghatak’s Meghe Dhaka Tara (The Cloud-Capped Star) 1960<br />

is considered one of the most important cinematic statements of its time. Set amongst a refugee<br />

community in post-partition Bengal, it is a compassionate study of dislocation and poverty<br />

experienced by a family uprooted from their ancestral home. Sanjay Kak and Sarah Singh belong<br />

to a younger generation of documentary filmmakers who offer insights into the continuing effects<br />

of partition and the possibility of transcending the divisions created. In Jashn-e-Azadi (How We<br />

Celebrate Freedom) 2007, Kak examines two decades of conflict in the disputed territories of<br />

Jammu and Kashmir and the differing interpretations of azadi (freedom) throughout the Kashmir<br />

valley. By reflecting on first-person testimonies, Singh’s The Sky Below 2007 asks whether the<br />

shared cultural roots of India and Pakistan may bring lasting peace between them in the future.<br />

Similarly, in the predominantly Buddhist country of Sri Lanka, filmmakers have examined the 26<br />

years of civil war between the Sinhala majority and Tamil minority, and the continuing struggle for<br />

an independent Tamil state. 1 In Sulanga Enu Pinisa (The Forsaken Land) 2005 and Ahasin Wetei<br />

(Between Two Worlds) 2009, Vimukthi Jayasundara expresses a pervasive ambivalence felt in<br />

Sri Lanka. The films respectively investigate a period of ceasefire in 2001, and the defeat of the<br />

Tamil Tigers by the Sri Lankan military in May 2009, both signalling the end, if only temporarily,<br />

of fighting throughout the country. 2 Jayasundara shows a nation suspended in a state of being<br />

without war and without peace and, like his contemporaries Asoka Handagama, Dharmasena<br />

Pathiraja and Prasanna Vithanage, attempts to reconcile the history, religious myth and political<br />

rhetoric which have brought both Tamil and Sinhalese nationalist discourse into being.<br />

<strong>Art</strong>ists and filmmakers in Lebanon, Israel and Palestine underline the imbrication of faith,<br />

nationalism and memory, as well as the relationship between political instability and resistance<br />

across the Middle East. Cinematic approaches to its social and political situation often<br />

combine personal observations with performative devices designed to question the situations<br />

presented and their inscription in collective memory. First shot as a documentary before<br />

being reconstructed as an animated film, Ari Folman’s Vals Im Bashir (Waltz with Bashir) 2008<br />

explores the trauma — and its legacy of unresolved guilt — that he experienced as a young<br />

Israeli conscript during the 1982 Israel–Lebanon war. 3 The soldier’s haunting dreams awaken a<br />

powerful examination of personal memory and responsibility independent of media versions of<br />

the events. In contrast, Avi Mograbi’s Z32 2008 uses musical numbers and a Greek chorus-like<br />

ensemble to reflect the director’s ambivalence at reducing to artistic representation a soldier’s<br />

confession of complicity in the death of two innocent Palestinian policemen.<br />

Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige’s Baddi Chouf (I Want to See) 2008 underlines the<br />

importance of bearing witness to historical events. The directors stage a road trip for French actress<br />

Catherine Deneuve and celebrated Lebanese artist–actor Rabih Mroué to survey the devastated<br />

regions of southern Lebanon after the 2006 Israel–Hezbollah War. Explaining their motivation<br />

for the experiment and its significance for international audiences, the directors have written:<br />

There are many things to be seen, but what do we see? . . . Catherine never pretends she<br />

knows, she is not affirming anything . . . Catherine herself says: ‘I don’t know if I’ll understand<br />

anything, but I want to see’. In today’s world, it is important to be in a time of questioning.<br />

We are never finished with what there is to see, the important [thing] is the feeling. 4<br />

44 45

Ari Folman<br />

Israel b.1963<br />

Production stills from Vals Im Bashir (Waltz with Bashir)<br />

2008 / 35mm, colour, Dolby Digital, 90 minutes, Israel/<br />

France/USA/Finland/Switzerland/Belgium/Australia,<br />

Hebrew/German/English/Arabic (English subtitles) /<br />

Image courtesy: Sharmill Films, Melbourne<br />

While Palestinian cinema finds its roots in the traumatic experience of dispossession — the nakba<br />

or ‘catastrophe’, 5 which followed the exodus of Palestinians from their homeland and the creation<br />

of the State of Israel in 1948 — many contemporary artists and filmmakers working in the Gaza<br />

Strip have produced works that stand out against the gravity we might expect. Elia Suleiman’s<br />

Al Zaman Al Baqi (The Time That Remains) 2009 uses irreverent humour and absurdist situations<br />

to chart his father’s move from resistance fighter during Israel’s 1948 War of Independence to<br />

postwar compliance, alongside the filmmaker’s own path from young conformist to rebellious<br />

activist then, ultimately, to mute observer. Larissa Sansour’s Happy Days 2006 employs the theme<br />

music from the 1970s American sitcom of the same name to convey the resilience of individuals<br />

in the occupied territories and their ability to transcend expectations of their experiences.<br />

A refusal to be defined by historical trauma or political circumstances is characteristic of works<br />

by artists and filmmakers from Armenia and the diaspora. At the juncture of West Asia and<br />

Eastern Europe, Armenians live with the legacies of the 1915 Armenian Genocide in which over<br />

a million Armenians were killed. 6 Economic hardships resulting from Armenia’s independence<br />

from the Soviet Union in 1991, as well as the Armenia–Azerbaijan conflict that followed it,<br />

are reflected in Harutyun Khachatryan’s Sahman (Border) 2009, where a buffalo becomes<br />

the symbol of trauma and redemption on a farm occupied by refugees. <strong>Art</strong>avazd Pelechian’s<br />

cinematic poems Tarva Yeghanakneve aka Vremena Goda (The Seasons) 1972 and Obibateli<br />

(The Inhabitants) 1970 celebrate resilient humanity, raw animal life, landscape and community<br />

in an allegorical register that creates new cinematic languages.<br />

The region from Afghanistan to Iraq and Iran has experienced parallel trajectories of political<br />

manipulation, war and invasion, with outside political interference in Iran’s internal politics from<br />