PDF Download - Glidewell Dental Labs

PDF Download - Glidewell Dental Labs

PDF Download - Glidewell Dental Labs

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

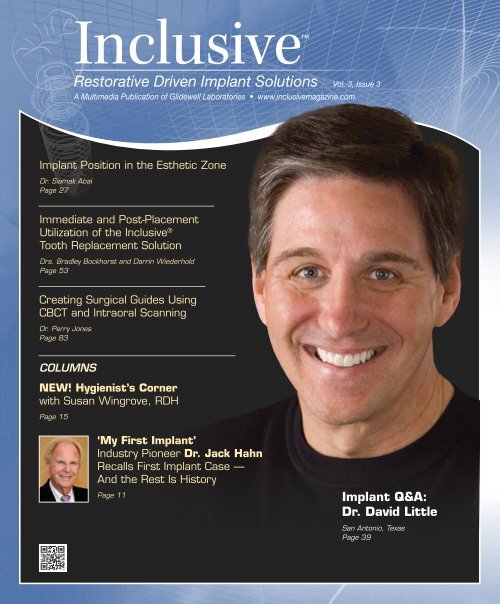

Inclusive<br />

Restorative Driven Implant Solutions Vol. 3, Issue 3<br />

A Multimedia Publication of <strong>Glidewell</strong> Laboratories • www.inclusivemagazine.com<br />

Implant Position in the Esthetic Zone<br />

Dr. Siamak Abai<br />

Page 27<br />

Immediate and Post-Placement<br />

Utilization of the Inclusive ®<br />

Tooth Replacement Solution<br />

Drs. Bradley Bockhorst and Darrin Wiederhold<br />

Page 53<br />

Creating Surgical Guides Using<br />

CBCT and Intraoral Scanning<br />

Dr. Perry Jones<br />

Page 83<br />

COLUMNS<br />

NEW! Hygienist’s Corner<br />

with Susan Wingrove, RDH<br />

Page 15<br />

‘My First Implant’<br />

Industry Pioneer Dr. Jack Hahn<br />

Recalls First Implant Case —<br />

And the Rest Is History<br />

Page 11<br />

Implant Q&A:<br />

Dr. David Little<br />

San Antonio, Texas<br />

Page 39

On the Web<br />

Here’s a sneak peek at additional<br />

Inclusive magazine content available online<br />

ONLINE Video Presentations<br />

■ Dr. Bradley Bockhorst details the process by which the Inclusive ®<br />

Tooth Replacement Solution can be used to efficiently and predictably<br />

restore a missing mandibular molar.<br />

■ Dr. Siamak Abai outlines spatial and angular considerations for the<br />

optimal placement of dental implants in the esthetic zone.<br />

■ Dr. David Little discusses some of the exciting services made possible<br />

by cutting-edge dental technologies, emphasizing the beneficial<br />

nature of personalized diagnoses and treatments.<br />

■ Dr. Michael DiTolla illustrates the use of a lab-fabricated verifi cation<br />

jig to obtain an accurate occlusal relationship in distal free-end cases.<br />

■ <strong>Glidewell</strong> Laboratories unveils the Open Platform Inclusive Tooth<br />

Replacement Solution, expanding this revolutionary treatment package<br />

to accommodate other popular implant brands.<br />

■ Drs. Darrin Wiederhold and Bradley Bockhorst demonstrate the<br />

clinician’s option with the Inclusive Tooth Replacement Solution to<br />

immediately temporize an implant with custom healing components<br />

or to provide patient-specific temporization post-implant placement.<br />

■ Dzevad Ceranic, CDT, and <strong>Glidewell</strong> staff showcase the advantages,<br />

increasing popularity, and industry-leading quality of Inclusive ®<br />

Custom Abutments.<br />

Check out the latest issue of Inclusive<br />

magazine online or via your smartphone<br />

at www.inclusivemagazine.com<br />

■ Dr. Christopher Travis reviews the symptoms, causes, and treatment<br />

of dry mouth, promoting implant-borne restorations as a solution<br />

for the partially or fully edentulous xerostomia patient.<br />

■ Dr. Perry Jones highlights the merging of CBCT and intraoral<br />

scanning technology to create precise surgical guides for safer,<br />

more predictable implant surgeries.<br />

Look for these icons on the pages that follow<br />

for additional content available online<br />

ONLINE CE credit<br />

■ Get free CE credit for the material in this issue with each test you<br />

complete and pass. To get started, visit our website and look for<br />

the articles marked with “CE.”<br />

– www.inclusivemagazine.com –

Contents<br />

19<br />

Restoring Mandibular Single Teeth with the<br />

Inclusive Tooth Replacement Solution<br />

The replacement of missing mandibular molars with single-tooth,<br />

implant-borne restorations provides many benefits over fixed partial<br />

dentures, and is by far the most common indication for implant treatment,<br />

according to laboratory statistics. Dr. Bradley Bockhorst offers<br />

a detailed walkthrough of the process by which the Inclusive Tooth<br />

Replacement Solution can be used to simplify the restorative process<br />

and provide a predictable outcome for this common restoration.<br />

27<br />

Implant Position in the Esthetic Zone<br />

Proper implant positioning is patient- and quite often implant-specific,<br />

making prosthetic treatment planning and pre-placement protocol<br />

paramount for achieving predictable restorative results. Dr. Siamak<br />

Abai, staff dentist of clinical research at <strong>Glidewell</strong> Laboratories, details<br />

some of the established parameters with regard to implant spacing and<br />

angulation, and highlights the use of advanced tools such as Inclusive<br />

Digital Treatment Planning services and the Inclusive Tooth Replacement<br />

Solution to execute precise control over each individual case.<br />

39<br />

Implant Q&A: An Interview with Dr. David Little<br />

In this interview, a Texas-sized passion for excellence and commitment<br />

to improving quality of life for edentulous patients comes through as<br />

Dr. David Little weighs in on several aspects of what makes today’s<br />

progressive dental practice a success. Find out what this general dentist<br />

has to say on topics ranging from building a truly interdisciplinary<br />

practice, to incorporating advanced technologies, to educating the<br />

entire team, to treatment planning for patients as if they were family.<br />

53<br />

Photo Essay: Immediate and Post-Placement<br />

Utilization of the Inclusive Tooth Replacement Solution<br />

The Inclusive Tooth Replacement Solution enables clinicians to<br />

place and immediately temporize single-unit implants in edentulous<br />

spaces. It can also be used in cases where the implant has already<br />

been placed. With a pair of case reports, Drs. Darrin Wiederhold<br />

and Bradley Bockhorst illustrate the simplified, predictable process<br />

by which this versatile, one-of-a-kind solution addresses implant<br />

placement and soft tissue healing in a manner that will help pave<br />

the path to a superior final restoration.<br />

– Contents – 1

Contents<br />

75<br />

83<br />

91<br />

Treating Xerostomia Patients:<br />

A Clinical Conversation with Dr. Christopher Travis<br />

Dentists are often the first to identify patients who are experiencing<br />

the effects of xerostomia, or dry mouth. Here, Dr. Christopher<br />

Travis offers a brief refresher on oral anatomy and the major sets<br />

of salivary glands as he explores the symptoms, causes, treatment<br />

options, and advantages of dental implants for xerostomia patients.<br />

Implant prostheses can provide a good solution for these patients.<br />

Creating Surgical Guides Using CBCT and<br />

Intraoral Scanning<br />

Among recent advances in the use of Align Technology’s iTero <br />

optical scanner is the ability to merge its generic STL files<br />

directly with CBCT DICOM files to allow for the creation of very<br />

precise, tooth-borne surgical guides. In this clinical case report,<br />

Dr. Perry Jones showcases the use of oral scanning technology to<br />

plan implant placement, create a precise surgical guide in a virtual<br />

environment, place implant fixtures, and restore those implants —<br />

all without the use of a conventional analog model.<br />

“Rules of 10” — Guidelines for Successful<br />

Planning and Treatment of Mandibular Edentulism<br />

Using <strong>Dental</strong> Implants<br />

The three “Rules of 10” for treatment planning dental implant therapy<br />

in the edentulous mandible are designed to improve the success<br />

of both endosseous implants and the prosthesis. These so-called<br />

rules acknowledge and provide a method to control the mechanical<br />

environment, addressing factors affecting implant and prosthesis<br />

longevity. Dr. Lyndon Cooper, et al., outline and provide support<br />

for these rules, then illustrate their application in the treatment of<br />

mandibular edentulism.<br />

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE<br />

8 Trends in Implant Dentistry<br />

Average Number of Implants per Case<br />

11 My First Implant<br />

Dr. Jack Hahn<br />

15 Hygienist’s Corner<br />

A Probing Question<br />

31 Small Diameter Implants<br />

Planning from the<br />

Prosthetic Perspective<br />

35 Clinical Tip<br />

Bone Quality Based Drilling<br />

Protocol: Achieving High<br />

Primary Stability<br />

47 Product Spotlight<br />

Inclusive Tooth Replacement<br />

Solution: Open Platform<br />

49 Clinical Tip<br />

Obtaining Accurate Occlusal Records<br />

in Kennedy Class I and Class II<br />

Implant Cases<br />

65 Clinical Tip<br />

When a Flapless Approach<br />

Makes Sense<br />

67 Lab Sense<br />

Best in Class: Inclusive<br />

Custom Abutments<br />

2<br />

– www.inclusivemagazine.com –

Publisher<br />

Jim <strong>Glidewell</strong>, CDT<br />

Editor-in-Chief and clinical editor<br />

Bradley C. Bockhorst, DMD<br />

Managing Editors<br />

David Casper, Jennifer Holstein, Barbara Young<br />

Creative Director<br />

Rachel Pacillas<br />

Contributing editors<br />

Greg Minzenmayer; Dzevad Ceranic, CDT;<br />

Eldon Thompson<br />

copy editors<br />

David Frickman, Megan Strong<br />

digital marketing manager<br />

Kevin Keithley<br />

Graphic Designers/Web Designers<br />

Emily Arata, Jamie Austin, Deb Evans,<br />

Kevin Greene, Joel Guerra, Audrey Kame,<br />

Phil Nguyen, Kelley Pelton, Melanie Solis,<br />

Ty Tran, Makara You<br />

Photographers/Videographers<br />

Sharon Dowd, Mariela Lopez,<br />

James Kwasniewski, Andrew Lee,<br />

Marc Repaire, Sterling Wright, Maurice Wyble<br />

Illustrator<br />

Phil Nguyen<br />

coordinatorS/AD Representatives<br />

Teri Arthur, Vivian Tsang<br />

If you have questions, comments or suggestions, e-mail us at<br />

inclusivemagazine@glidewelldental.com. Your comments may<br />

be featured in an upcoming issue or on our website.<br />

© 2012 <strong>Glidewell</strong> Laboratories<br />

Neither Inclusive magazine nor any employees involved in its publication<br />

(“publisher”) makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes<br />

any liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness<br />

of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or<br />

represents that its use would not infringe proprietary rights. Reference<br />

herein to any specific commercial products, process, or services by<br />

trade name, trademark, manufacturer or otherwise does not necessarily<br />

constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring<br />

by the publisher. The views and opinions of authors expressed<br />

herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the publisher and<br />

shall not be used for advertising or product endorsement purposes.<br />

CAUTION: When viewing the techniques, procedures, theories and<br />

materials that are presented, you must make your own decisions<br />

about specific treatment for patients and exercise personal professional<br />

judgment regarding the need for further clinical testing or education<br />

and your own clinical expertise before trying to implement new<br />

procedures.<br />

Inclusive is a registered trademark of Inclusive <strong>Dental</strong> Solutions.<br />

4<br />

– www.inclusivemagazine.com –

Letter from the Editor<br />

There are many axioms used in implantology, such as, “begin with the end<br />

in mind” and “implant dentistry is a restorative procedure with a surgical<br />

component,” all pointing to the importance of proper diagnosis and case<br />

work-up. Addressing this topic we have: an article on implant planning<br />

in the esthetic zone, penned by our own Dr. Siamak Abai; an interview<br />

with Dr. David Little, where we look at treating the edentulous patient;<br />

and, because treatment planning should be considered not just from the<br />

surgical perspective but from the prosthetic aspect as well, we’ve included<br />

an informative article by Dr. Lyndon Cooper, et al., with guidelines for<br />

restoring edentulous mandibles. Our Small Diameter Implants column<br />

reviews the importance of planning from the prosthetic perspective for<br />

overdenture cases.<br />

As you’ve seen in the last few issues, the Inclusive ® Tooth Replacement<br />

Solution has the potential to change the way implant dentistry is practiced.<br />

We are pleased to announce the expansion of this comprehensive solution<br />

for other major implant platforms, as well as post-placement utilization<br />

of its patient-specific components. For more on this topic, check out our<br />

product spotlight (page 47) and photo essay (page 53).<br />

In our My First Implant column, we feature one of implant dentistry’s<br />

pioneers, Dr. Jack Hahn, who takes us back to 1969 — when another<br />

revolution entirely was taking place. We are confident you’ll enjoy this<br />

retrospective from a clinician who has made major contributions to<br />

implantology. We are also introducing a new column that will focus on a<br />

very critical aspect of implant dentistry: the role of the dental hygienist.<br />

Susan Wingrove, RDH, skillfully kicks off the Hygienist’s Corner with her<br />

discussion of evaluating implants at the recall appointment.<br />

These are exciting times. The field of implant dentistry is rapidly advancing,<br />

and we are committed to keeping you up to date with new technologies<br />

and procedures as we continue to provide easy, convenient, and<br />

affordable solutions for you and your patients.<br />

Wishing you continued success,<br />

Dr. Bradley C. Bockhorst<br />

Editor-in-Chief, Clinical Editor<br />

inclusivemagazine@glidewelldental.com<br />

– Letter from the Editor – 5

Contributors<br />

■ Bradley C. Bockhorst, DMD<br />

After receiving his dental degree from<br />

Washington University School of <strong>Dental</strong><br />

Medicine, Dr. Bradley Bockhorst served<br />

as a Navy <strong>Dental</strong> Officer. Dr. Bockhorst is<br />

director of clinical technologies at <strong>Glidewell</strong><br />

Laboratories, where he oversees Inclusive ®<br />

Digital Implant Treatment Planning services<br />

and is editor-in-chief and clinical editor of Inclusive<br />

magazine. A member of the CDA, ADA, AO, ICOI and the<br />

AAID, Dr. Bockhorst lectures internationally on an array<br />

of dental implant topics. Contact him at 800-521-0576 or<br />

inclusivemagazine@glidewelldental.com.<br />

■ DZEVAD CERANIC, CDT<br />

Dzevad Ceranic began his career at <strong>Glidewell</strong><br />

Laboratories while attending Pasadena<br />

City College’s dental laboratory technology<br />

program. In 1999, Dzevad began working at<br />

<strong>Glidewell</strong> as a waxer and metal finisher, then<br />

as a ceramist. He was then promoted to general<br />

manager of the Full-Cast department. In 2008,<br />

Dzevad took on the company’s rapidly growing Implant department,<br />

and in 2009 completed an eight-month implants course<br />

at UCLA School of Dentistry. Today, Dzevad leads an implant<br />

team of more than 250 employees at the lab. Contact him at<br />

inclusivemagazine@glidewelldental.com.<br />

■ SIAMAK ABAI, DDS, MMedSc<br />

Dr. Siamak Abai earned his DDS degree from<br />

Columbia University in 2004, followed by<br />

two years of residency in general dentistry.<br />

After two years of general private practice in<br />

Huntington Beach, Calif., Dr. Abai returned<br />

to academia and received an MMedSc degree<br />

and a certificate in prosthodontics from<br />

Harvard University. Before joining <strong>Glidewell</strong> in January<br />

2012, he practiced at the Wöhrle <strong>Dental</strong> Implant Clinic in<br />

Newport Beach. Dr. Abai brings nearly 10 years of clinical,<br />

research, and lecturing experience to his role as staff dentist<br />

of clinical research at <strong>Glidewell</strong> Laboratories. Contact him at<br />

inclusivemagazine@glidewelldental.com.<br />

■ LYNDON F. COOPER, DDS, Ph.D<br />

Dr. Lyndon Cooper serves as a professor<br />

and current chair of the University of North<br />

Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Dentistry<br />

Department of Prosthodontics and has an<br />

adjunct appointment at the UNC School of<br />

Medicine. Dr. Cooper is also director of the<br />

graduate prosthodontics program and the<br />

Bone Biology and Implant Therapy Laboratory. He is a<br />

Diplomate of the American Board of Prosthodontics and<br />

current president of the American College of Prosthodontics<br />

Board of Directors. His lab’s research findings have been<br />

presented in more than 70 publications. Contact him at<br />

lyndon_cooper@dentistry.unc.edu.<br />

■ GRANT BULLIS, MBA<br />

Grant Bullis, director of implant R&D and<br />

digital manufacturing at <strong>Glidewell</strong> Laboratories,<br />

began his dental industry career at<br />

Steri-Oss (now a subsidiary of Nobel Biocare)<br />

in 1997. Since joining the lab in 2007,<br />

Grant has been integral in obtaining FDA<br />

510(k) clearances for the company’s Inclusive<br />

® Custom Implant Abutments. In 2010, he was promoted<br />

to director and now oversees all aspects of CAD/CAM, implant<br />

product development, and manufacturing. Grant has<br />

a degree in mechanical CAD/CAM from Irvine Valley College<br />

and an MBA from Keller Graduate School of Management.<br />

Contact him at inclusivemagazine@glidewelldental.com.<br />

■ JACK A. HAHN, DDS<br />

Dr. Jack Hahn earned his DDS from Ohio State<br />

University College of Dentistry, and completed<br />

postgraduate coursework at Boston University,<br />

New York University, the University of Michigan<br />

and the University of Kentucky. A pioneer in the<br />

field who developed the NobelReplace ® dental<br />

implant system for Nobel Biocare, Dr. Hahn<br />

has been actively involved in placing and restoring implants for<br />

40 years. In addition to lecturing to dentists around the world,<br />

he maintains a private practice in Cincinnati, Ohio, focused<br />

on placing and restoring implants. In 2004, he received the<br />

Aaron Gershkoff Lifetime Achievement Award in implant<br />

dentistry. Contact him at replace7@mac.com.<br />

6<br />

– www.inclusivemagazine.com –

■ PERRY E. JONES, DDS, FAGD<br />

Dr. Perry Jones received his DDS from<br />

Virginia Commonwealth University School of<br />

Dentistry, where he has held adjunct faculty<br />

positions since 1976. He maintains a private<br />

practice in Richmond, Va. One of the first GP<br />

Invisalign ® providers, Dr. Jones has been a<br />

member of Align’s Speaker Team since 2002,<br />

presenting more than 250 Invisalign presentations. He has<br />

been involved with CADENT optical scanning technology<br />

since its release to the GP market and is currently beta<br />

testing its newest software. Dr. Jones belongs to numerous<br />

dental associations and is a fellow of the AGD. Contact him<br />

at perry@drperryjones.com.<br />

■ CHRISTOPHER P. TRAVIS, DDS<br />

Dr. Christopher Travis received his dental<br />

degree and certificate in prosthodontics from<br />

USC School of Dentistry, where he served as an<br />

assistant clinical professor in predoctoral and<br />

graduate prosthodontics. For the past 30 years,<br />

he has maintained a full-time private practice<br />

specializing in prosthodontics in Laguna<br />

Hills, Calif. Dr. Travis is director of the Charles Stuart Study<br />

Group in Laguna Hills, prosthodontic coordinator for the<br />

Newport Harbor Academy of Dentistry and active member of<br />

the Pacific Coast Society for Prosthodontics, American College<br />

of Prosthodontists and AO, as well as a Fellow of the ACD.<br />

Contact him at 949-683-7456 or surfnswim@fea.net.<br />

■ DAVID A. LITTLE, DDS<br />

Dr. David Little received his DDS at the University<br />

of Texas Health Science Center at San<br />

Antonio <strong>Dental</strong> School and now maintains a<br />

multidisciplinary, state-of-the-art dental practice<br />

in San Antonio, Texas. An accomplished<br />

national and international speaker, professor,<br />

and author, he also serves the dental profession<br />

as a clinical researcher focusing on implants, laser surgery,<br />

and dental materials. As a professional consultant, he shares<br />

his expertise on emerging restorative techniques and materials<br />

with industry peers. Highly respected for his proficiency in<br />

team motivation, Dr. Little’s vision, leadership, and experience<br />

are recognized worldwide. Contact him at dlittledds@aol.com.<br />

■ DARRIN M. WIEDERHOLD, DMD, MS<br />

Dr. Darrin Wiederhold received his DMD<br />

in 1997 from Temple University School of<br />

Dentistry and a master’s degree in oral<br />

biology in 2006 from Medical University<br />

of Ohio at Toledo. He has worked in several<br />

private practices, and as a staff dentist for<br />

the U.S. Navy and the <strong>Glidewell</strong> Laboratories<br />

Implant department. While at <strong>Glidewell</strong>, he performed implant<br />

and conventional restorative procedures at the lab’s on-site<br />

training facility and helped support the lab’s digital treatment<br />

planning and guided surgery services. He is currently in private<br />

practice in San Diego, Calif. Contact him at 619-469-4144<br />

or DMWDMD97@hotmail.com.<br />

■ MICHAEL McCRACKEN, DDS, Ph.D<br />

After completing dental school at University of<br />

North Carolina at Chapel Hill and a prosthodontic<br />

residency at University of Alabama at<br />

Birmingham, Dr. Michael McCracken received<br />

a Ph.D in biomedical engineering for research<br />

related to growth factors and healing of implants<br />

in compromised hosts. Dr. McCracken is<br />

a professor in the department of general dental sciences at UAB<br />

School of Dentistry, where he has also served as associate dean<br />

for education, director of graduate prosthodontics, and director<br />

of the implant training program. He maintains an active<br />

research program within the university and a private practice<br />

focused on implant dentistry. He also lectures internationally.<br />

Contact him at inclusivemagazine@glidewelldental.com.<br />

■ SUSAN S. WINGROVE, RDH<br />

Susan Wingrove is a national and international<br />

speaker and practicing dental<br />

hygienist, who does regeneration research as<br />

a consultant for Regena Therapeutics and<br />

instrument design for Paradise <strong>Dental</strong> Technologies<br />

Inc. She designed the Wingrove<br />

Implant Series, ACE probes, and Queen of<br />

Hearts instruments. A member of the AO and The Implant<br />

Consortium (TIC), she is also a published author on implant<br />

dentistry who has written articles for Hygienetown and the<br />

British Society of <strong>Dental</strong> Hygiene and Therapy, as well as the<br />

textbook “Peri-Implant Therapy for the <strong>Dental</strong> Hygienist: A<br />

Clinical Guide to Implant Maintenance” (Wiley-Blackwell).<br />

Contact her at sswinrdh@gmail.com.<br />

– Contributors – 7

Trends in<br />

Implant Dentistry<br />

Average Number of Implants per Case<br />

With the large number of implant-borne cases fabricated at <strong>Glidewell</strong> Laboratories, certain<br />

evolving trends have come to light. Here are some stats about the number of implants that<br />

are being placed per case.<br />

1 Implant 2 Implants 3 Implants 4 Implants 5+ Implants<br />

Number of Implants per Case<br />

2010<br />

Number of Implants per Case<br />

2011<br />

71%<br />

75%<br />

3%<br />

3%<br />

7%<br />

16%<br />

1%<br />

1%<br />

4%<br />

19%<br />

Data Source: <strong>Glidewell</strong> Laboratories January 2010–August 2012<br />

8<br />

– www.inclusivemagazine.com –

In an evaluation of more than 70,000 cases,<br />

the average number of implants per case is<br />

Of all the cases we have processed<br />

over the last three years…<br />

1.43<br />

66%…were single teeth<br />

Number of Implants per Case<br />

2012 YTD<br />

Number of Implants per Case<br />

January 2010–August 2012<br />

60%<br />

69%<br />

1%<br />

1%<br />

24%<br />

14%<br />

1%<br />

2 % 11%<br />

17%<br />

Watch here for emerging trends<br />

Check back here for more observations in the next issue.<br />

– Trends in Implant Dentistry: Average Number of Implants per Case – 9

my first<br />

implant<br />

with Jack A. Hahn, DDS<br />

ack in the summer of 1969, against the<br />

backdrop of the cultural craziness that<br />

was the late sixties, there was another,<br />

quieter revolution taking place. Not man<br />

walking on the moon. Not the Beatles’ “Sgt. Pepper”<br />

album taking hold of a generation. But a sign of the<br />

times that technologies were changing the way we<br />

do things across professions, including the field of<br />

dentistry. Here, Dr. Jack Hahn recalls placing his<br />

first implant, an experience that would set the<br />

course for the rest of his professional life — and<br />

the lives of his future patients.<br />

– My First Implant: Dr. Jack Hahn – 11

We’ve Come a Long Way<br />

From subperiosteal implants…<br />

...to combined root-form and blade implants…<br />

...to the modern endosseous designs and CAD/CAM restorations of today.<br />

I got interested in implants when a patient<br />

came into my office one summer, decades ago, holding a<br />

shoebox that contained no less than 17 sets of dentures. She<br />

had a severely atrophic mandible that made it impossible<br />

to retain a mandibular conventional denture — and she<br />

was an emotional wreck. Her husband, who was a wellrespected<br />

orthopedic surgeon, explained that she was a<br />

dental cripple and that this condition had all but destroyed<br />

their social lives. They declined invitations to parties and<br />

avoided going out in public because she couldn’t wear her<br />

lower teeth. So sad. At the time I didn’t think there was any<br />

hope, and I told her so. (But the seed was planted.)<br />

Then, I ran into her husband at a hospital function. He’d<br />

since read about dental implants in an orthopedic journal,<br />

but I told him those things didn’t work. “There is infection<br />

and rejection.” That’s what we were told in school. In short,<br />

I gave them no solution or possibility for a better quality<br />

of life. I saw the husband yet again about five months later<br />

at a hospital meeting. He had since taken his wife to New<br />

York, and a Dr. Linkow had placed a subperiosteal implant<br />

that changed their lives. She could eat anything. They were<br />

able to go out in public again. And her self-confidence improved<br />

significantly. He said to me, “Implant dentistry is<br />

the future,” and that I should learn all about it — or get left<br />

behind. This advice, coming from an orthopedic surgeon,<br />

was a wake-up call.<br />

In January of 1970, I went to New York to take Dr. Leonard<br />

Linkow’s course. It was two days with a hands-on portion<br />

where the participants placed an endosseous blade in a<br />

clear plastic model. In order to take the course, you had to<br />

12<br />

– www.inclusivemagazine.com –

The House that Jack Built<br />

Inspired by that first experience, Dr. Jack Hahn went<br />

on to develop implant techniques and devices known<br />

for their simple yet ingenious designs that are used<br />

around the world today.<br />

1977 Miter blade-form implants<br />

1979 Titanodont root-form implants<br />

1986 Steri-Oss root-form and blade implants<br />

1997<br />

NobelReplace ® Tapered implant<br />

(Nobel Biocare)<br />

I didn’t sleep the<br />

night before.<br />

Evolution in Immediate Function<br />

purchase the implant kit, which consisted of 12 one-piece<br />

blades, 700 XXL burs, depth gauge, mallet, pliers, and seating<br />

instrument. A channel was prepared, and the implants<br />

were malleted into place using the seating instruments. As<br />

the implants were one piece with an abutment portion,<br />

one or two of the anterior abutment teeth were prepared,<br />

and an immediate provisional restoration was placed for<br />

immediate function. Three to six weeks post-insertion,<br />

impressions were taken for the final restoration: basically,<br />

a fixed bridge.<br />

Two months after completing the course, my first potential<br />

implant patient was sitting in my office for a consultation.<br />

She was bilaterally edentulous from the second premolars<br />

in the posterior mandible back. Her partial denture was<br />

wrapped in Kleenex in her purse. She said: “I can’t wear<br />

this thing, and I hate it. I want something permanent.”<br />

I told her that I had just taken an implant course, that<br />

she would be my first patient, and that I didn’t know if<br />

the things I demonstrated to her on my model would last<br />

10 minutes or 10 years. But she had good height and width<br />

of bone, so it seemed to me to be an ideal case. I told her<br />

we could do one side first, see how it went, and do the<br />

other side a month later. I also told her that because it was<br />

my first implant, I wouldn’t charge her for the implant, only<br />

the fixed bridge. She said, “Let’s do it.”<br />

In March of that same year, we scheduled Irma from 1:30<br />

p.m. to 5 p.m. I didn’t sleep the night before. I kept going<br />

over in my mind the incision, reflection of the soft tissue,<br />

implant groove preparation, implant placement, suturing,<br />

and fabrication of the provisional restoration.<br />

– My First Implant: Dr. Jack Hahn – 13

Sage advice for doctors<br />

new to implants<br />

1<br />

Enroll in an introductory<br />

course. Get a feel for whether implant<br />

dentistry is right for you.<br />

2<br />

3<br />

Educate yourself by enrolling<br />

in multiple courses. If implant<br />

dentistry is something you want to<br />

pursue, take an adequate number<br />

of courses — and wait until you feel<br />

confident in doing implant procedures.<br />

Learn basic surgical<br />

techniques. Aside from identifying<br />

important anatomical structures,<br />

diagnosis, treatment planning,<br />

radiographic interpretation and basic<br />

implant prosthetic principles — it’s<br />

critical that you understand basic<br />

surgical techniques.<br />

Start with an ideal case. Look<br />

for cases that have a good level of<br />

height and width of bone. Also, you<br />

want anatomical safe regions, such<br />

as the anterior mandible and single<br />

tooth replacements in both arches,<br />

eliminating three-unit bridges.<br />

Implant dentistry<br />

changed my life,<br />

as well as the<br />

lives of thousands<br />

of my patients.<br />

I started the procedure at 1:30 p.m. and had the provisional<br />

cemented by 3:30 p.m. Everything went absolutely perfectly.<br />

I was so excited that I said to my partner, “I don’t<br />

want to do anything else.” Replacing what nature had taken<br />

away was, from that instant on, exactly what I wanted to<br />

do for the rest of my professional life. Four weeks later, I<br />

placed her final bridge and placed the other implant on the<br />

opposite side. I told her that I’d have to charge her for that<br />

one because now I was an expert. We both laughed. She<br />

hugged me and said that I changed her life. Irma passed<br />

away in October 2000, 30 years later, with her implants and<br />

bridge still functioning until the day she died.<br />

After that first time, I went on to place many implant<br />

restorations, all types and various systems, over the next<br />

42 years. I estimate that I have placed and restored more<br />

than 30,000 implants. IM<br />

14<br />

– www.inclusivemagazine.com –

Hygienist’s<br />

Corner<br />

A Probing Question<br />

with Susan S. Wingrove, RDH<br />

When assessing for peri-implant disease, “bleeding on<br />

probing” (BOP) is invaluable in the diagnostic process for<br />

peri-implant mucositis, and probing depths are valuable<br />

in assessing loss of bone support around osseointegrated<br />

implants. 1,2 An important yet controversial component of<br />

the assessment is probing the dental implant.<br />

Some implant surgeons recommend not probing the<br />

implant, or waiting three to six months following abutment<br />

attachment to avoid disrupting the perimucosal seal. 3 The<br />

perimucosal seal is fragile, and penetration during probing<br />

can introduce pathogens and jeopardize the success of the<br />

implant. Recent studies show that 0.15 Ncm may represent<br />

the threshold pressure to be applied in order to avoid false<br />

positive BOP readings around oral implants. 4 Currently,<br />

clinicians are using 0.15 Ncm–0.20 Ncm of pressure, but most<br />

agree that probing around dental implants is more sensitive<br />

than probing natural teeth; thus, caution should be used. 4<br />

Emerging research holds that probing is not harmful,<br />

however, and is actually essential to the overall health of the<br />

implant. Complete regeneration of junctional epithelium and<br />

establishment of new epithelial attachment has been studied,<br />

revealing that probing around osseointegrated implants<br />

does not appear to have detrimental effects on the perimucosal<br />

seal. 5 Peri-implantitis infections occur in 28 to 56 percent<br />

of implants after five years. 6 An increase in reported cases<br />

of peri-implant diseases (collective term for inflammatory<br />

lesions, mucositis, and peri-implantitis) is a significant reason<br />

for monitoring and probing dental implants.<br />

The hygienist needs to know baseline measurements to be<br />

able to distinguish health from disease, or loss of osseointegration.<br />

This can give the hygienist a way of determining<br />

at recall visits whether detrimental changes have occurred.<br />

Also, if more than one hygienist is employed in the office,<br />

measurement with compatible probes in millimeters for all<br />

inflammation, exposed threads, or bone loss on films allow<br />

for more accurate monitoring and consistency.<br />

Courtesy of PDT Inc.<br />

Figure 1: Note difference in flexibility between metal probe (left) and plastic<br />

probe (right)<br />

There is a recommended protocol for probing dental<br />

implants. First, the complexity of implants makes the<br />

flexibility of the probe essential. Now with more platformswitching<br />

implants, narrow implants, and fixed prostheses,<br />

the tip needs to be flexible to follow the anatomy of the<br />

implant and get an accurate reading. Using a flexible<br />

plastic probe reduces the potential for trauma to the<br />

perimucosal seal and the risk of scratching the implant’s<br />

surface (Fig. 1).<br />

– Hygienist’s Corner: A Probing Question – 15

Protocol for Probing of <strong>Dental</strong> Implants<br />

Record the baseline measurements at the first implant maintenance appointment or after<br />

the allotted three months.<br />

● Use a flexible probe with 1 mm markings to de-plaque, which may be adequate<br />

supportive therapy.<br />

● Place the probe parallel to the long axis of the implant, six measurements per implant,<br />

and identify a location on the restoration as a monitor marker.<br />

● Gently probe using light pressure (only 0.15 Ncm) to check the clinical parameters.<br />

For new patients, record a baseline and note placement date, doctor who placed the implant,<br />

and any other details.<br />

Record if inflammation, bleeding on probing, cement, or exudate are present.<br />

Report findings to the dentist for evaluation.<br />

The hygienist needs to know<br />

baseline measurements<br />

to be able to distinguish<br />

health from disease,<br />

or loss of osseointegration.<br />

Second, record a probe baseline measurement, at a specific<br />

location, to establish a clinical parameter for the patient’s<br />

record (Fig. 2). Place the probe parallel to the long axis of<br />

the implant, six measurements per implant, and identify<br />

a location on the restoration as a monitor marker. Record<br />

this baseline measurement in the patient notes at the first<br />

maintenance appointment after the allotted three months. 7<br />

Ideally the measurement should read 2.5 mm–5 mm or<br />

less, depending on soft tissue depth, with no other signs of<br />

inflammation. 8 Compare this measurement to the baseline,<br />

and if the probe depth changes, note this in the chart. If<br />

the implant has a probing depth of 5 mm–6 mm or greater,<br />

bleeding, or a presence of exudate, a radiograph should<br />

be taken to assess the implant, and the doctor needs to<br />

evaluate for bone loss. 9<br />

16<br />

– www.inclusivemagazine.com –

Probe using only 0.15 Ncm of pressure so as not to jeopardize the success<br />

of the implant by possibly introducing pathogens into the peri-implant sulcus,<br />

or by damaging the delicate fibers that surround the implant.<br />

Courtesy of Dr. J Remien<br />

Courtesy of Nancy Adair, RDH<br />

Hygiene Excellence Inc.<br />

Figure 2: Recording and probing the baseline<br />

Figure 3: Probing the dental implant<br />

Third, probe using only 0.15 Ncm of pressure so as not<br />

to jeopardize the success of the implant by possibly<br />

introducing pathogens into the peri-implant sulcus, or by<br />

damaging the delicate fibers that surround the implant<br />

(Fig. 3). The perimucosal seal of the implant is fragile and<br />

more susceptible to trauma from probing than a natural<br />

periodontal ligament. If the tissue is healthy, the probe will<br />

stop at the coronal level, and if inflammation is present,<br />

the probe tip will penetrate close to the bone.<br />

Finally, use the probe as a measuring device for documenting<br />

inflammation and measuring exposed implant threads<br />

for monitoring. Continue to record and monitor by comparing<br />

the measurement to the baseline at every implant<br />

maintenance appointment. If probe depths have changed<br />

or inflammation, bleeding on probing, cement, or exudate<br />

are present, bring this information to the dentist’s attention<br />

per proper protocol for probing of implants.<br />

Using proper protocol, probing is one of the key monitoring<br />

tools in evaluating the health of the tissue surrounding<br />

the dental implant. Inflammation or bleeding on probing<br />

should not occur with healthy peri-implant tissue. Keep in<br />

mind that peri-implant infections can progress more rapidly<br />

than an infection in a natural tooth. Therefore, monitoring<br />

the tissue surrounding the dental implant is critical in the<br />

overall long-term success of the implant. IM<br />

– Hygienist’s Corner: A Probing Question – 17

Using proper protocol, probing is one of the key monitoring tools<br />

in evaluating the health of the tissue surrounding the dental implant.<br />

References<br />

1. Salvi GE, Lang NP. Diagnostic parameters for monitoring peri-implant conditions.<br />

Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2004;19 Suppl:116-127.<br />

2. Lang NP, Mombelli A, Tonetti MS, Brägger U, Hämmerle CH. Clinical trials on<br />

therapies for peri-implant infections. Ann Periodontol. 1997 Mar:2(1):343-356.<br />

3. Bauman GR, Mills M, Rapley JW, Hallmon WH. Clinical parameters of evaluation<br />

during implant maintenance. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 1992 Summer;<br />

7(2):220-227.<br />

4. Gerber JA, Tan WC, Balmer TE, Salvi GE, Lang NP. Bleeding on probing and<br />

pocket probing depth in relation to probing pressure and mucosal health around<br />

oral implants. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2009 Jan:20(1):75-78.<br />

5. Etter TH, Hakanson I, Lang NP, Trejo PM, Caffesse RG. Healing after standardized<br />

clinical probing of the peri-implant soft tissue seal: a histomorphometric study in<br />

dogs. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2002 Dec;13(6):571-580.<br />

6. Nogueira-Filho G, Iacopino AM, Tenenbaum HC. Prognosis in implant dentistry:<br />

a system for classifying the degree of peri-implant mucosal inflammation. J Can<br />

Dent Assoc. 2011;77:b8.<br />

7. Mombellli A, Mühle T, Brägger U, Lang NP, Bürgin WB. Comparison of periodontal<br />

and peri-implant probing by depth-force pattern analysis. Clin Oral Implant<br />

Res. 1997 Dec;8(6):448-454.<br />

8. Misch CE. Contemporary Implant Dentistry. 3rd ed. St. Louis: Mosby;2008:1061.<br />

9. Stuart J. Froum, DDS. My patient’s implant is bleeding; what do I do? DentistryIQ,<br />

July 13, 2011.<br />

18<br />

– www.inclusivemagazine.com –

Restoring Mandibular Single Teeth<br />

with the Inclusive Tooth Replacement Solution<br />

Go online for<br />

in-depth content<br />

by<br />

Bradley C. Bockhorst, DMD<br />

While the prosthetic rehabilitation of<br />

full-arch cases provides a tremendous<br />

service for the patient and can be very<br />

professionally rewarding for the clinician, single<br />

tooth replacement is by far the most common<br />

implant restoration. Restoring single posterior<br />

teeth with implants provides a viable treatment<br />

option and has been well documented. 1-5 Of the<br />

single posterior teeth, the first molar, or “money<br />

tooth” as termed by Dr. Curtis Jansen, very<br />

often requires replacement. 6 At the <strong>Glidewell</strong><br />

Laboratories operatory, 59 percent of the single<br />

Inclusive ® Tapered Implants placed have been<br />

in the posterior mandible.<br />

One of the most obvious concerns when placing<br />

implants in the posterior mandible is identifying<br />

and avoiding the inferior alveolar nerve (IAN). 7<br />

This can be accomplished through the use of<br />

appropriate radiography and proper planning.<br />

– Restoring Mandibular Single Teeth with the Inclusive Tooth Replacement Solution – 19

Conventional implant planning typically involves the use<br />

of a periapical radiograph (PA) and/or a panoramic film.<br />

The drawback to these types of two-dimensional images is<br />

distortion. The PA should be taken with a paralleling technique<br />

to avoid vertical distortion as much as possible. A<br />

radiographic marker of known diameter (e.g., 5 mm ball<br />

bearing) can be used to determine the distortion in the<br />

planned implant site. The marker is measured on the film<br />

to determine the distortion factor in that area. A transparent<br />

overlay can be used as an aid to determine the correct<br />

implant selection (Fig. 1).<br />

Another option is a CT scan. Cone beam scanners provide a<br />

three-dimensional image and a precise method for identification<br />

of the IAN. 8 The patient’s scan can be imported into<br />

planning software, the mandibular canal identified, and the<br />

implant placed in a virtual environment (Fig. 2).<br />

In the case presented here, the canal was well differentiated<br />

and identified. The mandibular canal is typically identifiable.<br />

However, there are situations where the cortical bone<br />

surrounding the canal is not dense and therefore does not<br />

show up radiographically. These cases present a significant<br />

challenge. One rule of thumb for first molars is to not drill<br />

deeper than the roots of the adjacent teeth.<br />

An optical scan of the model provides a clear view of<br />

the anatomy of the teeth and the soft tissue (Fig. 3). The<br />

appropriate-sized implant is placed within the confines of<br />

the available bone (Fig. 4). It is important to be aware that the<br />

drills are approximately 1 mm longer than the stated length<br />

of the implant. The trajectory of the implant is aimed toward<br />

the opposing stamp cusp through the center of the<br />

occlusal table.<br />

Figure 1: Implant radiographic template for Inclusive Tapered Implants<br />

Figure 2: Digital Treatment Plan<br />

Surgery<br />

The osteotomy should be prepared with the aid of a<br />

surgical or prosthetic guide. The prosthetic component of<br />

the Inclusive ® Tooth Replacement Solution is a traditional<br />

surgical stent designed to convey the ideal position of the<br />

implant platform from the restorative perspective (Figs. 5, 6).<br />

By starting the osteotomy using this guide, the implant will<br />

be inserted in the appropriate location to take advantage of<br />

the custom temporary abutment and BioTemps ® provisional<br />

crown. The prosthetic guide is intended for prosthetic<br />

reference only, and does not take into consideration any<br />

anatomical landmarks or contraindications. This guide<br />

should be used in combination with the radiographic and<br />

clinical information to determine the best position for<br />

the implant.<br />

Figure 3: View of mandibular arch with proposed implant trajectory<br />

A surgical guide based on the virtual plan utilizing a CBCT<br />

scan of the patient provides the option of drill depth and<br />

angulation control. Based on the amount of guidance<br />

desired, a surgical guide can be produced that guides the<br />

pilot drill. Subsequent drilling with progressively wider<br />

20<br />

– www.inclusivemagazine.com –

Figure 4: Cross-sectional view of proposed implant site<br />

Figure 7: Universal SurgiGuide<br />

Figure 5: The Inclusive Tooth Replacement Solution prosthetic guide<br />

Figure 8: Universal SurgiGuide in situ<br />

surgical drills (as needed) and implant placement are<br />

performed freehand.<br />

If additional guidance is needed, Universal SurgiGuides (Materialise<br />

<strong>Dental</strong>; Glen Burnie, Md.) are available (Figs. 7, 8).<br />

In these cases, all the drills can be guided. The implant is<br />

placed freehand once the osteotomy has been created.<br />

At the time of placement, a custom healing abutment can be<br />

delivered (Figs. 9, 10). The custom healing abutment allows<br />

you to start anatomically sculpting the soft tissues at the<br />

time of surgery.<br />

Figure 6: Prosthetic guide in situ<br />

A custom temporary abutment and BioTemps crown also<br />

are provided with the Inclusive Tooth Replacement Solution.<br />

If high primary stability is achieved and the crown is<br />

taken well out of occlusion, the implant can be temporized<br />

at the time of surgery. Due to the occlusal forces that can be<br />

exerted in the molar region, another approach would be to<br />

utilize the custom healing abutment at the time of surgery<br />

and provisionalize the case at a later date.<br />

– Restoring Mandibular Single Teeth with the Inclusive Tooth Replacement Solution – 21

Temporization<br />

Temporization utilizing the Inclusive Tooth Replacement<br />

Solution consists of seating the custom temporary abut ment,<br />

then relining and cementing the BioTemps provisional crown<br />

(Fig. 11). If a screw-retained temporary is preferred, after<br />

adjustments are made, an occlusal hole is drilled through<br />

the crown (Fig. 12). The abutment and internal surfaces are<br />

roughened up to help create mechanical retention. A guide<br />

pin is used to maintain the screw opening, and the crown is<br />

luted to the abutment with permanent cement. The crownabutment<br />

assembly is then delivered to the implant (Fig. 13),<br />

and the abutment screw is tightened to 15 Ncm (Fig. 14).<br />

The occlusal screw is covered with a piece of Teflon tape<br />

and the access opening sealed with composite (Fig. 15). The<br />

crown should be out of occlusion (Fig. 16).<br />

Figure 9: Inclusive Tooth Replacement Solution custom healing abutment<br />

Final Impressions<br />

The final impression is made with the Inclusive Tooth<br />

Replacement Solution custom impression coping (Fig. 17).<br />

The custom impression coping allows you to transfer the<br />

position of the implant as well as the soft tissue contours to<br />

the master cast. The custom impression coping is seated on<br />

the implant and the screw is tightened (Fig. 18).<br />

The access opening is sealed with soft wax to prevent<br />

impression material from flowing into the coping (Fig. 19).<br />

The closed-tray impression is made following standard<br />

technique. When the material has set, the impression is<br />

pulled. The impression coping is removed and replaced<br />

with the healing abutment or provisional restoration. The<br />

shade is selected (Fig. 20) and clinical photos are taken.<br />

A bite registration and impression of the opposing arch<br />

are made. The pre-populated Inclusive Tooth Replacement<br />

Solution lab prescription is filled out and the case sent to<br />

the lab.<br />

Figure 10: Custom healing abutment in place with access opening sealed<br />

Laboratory Fabrication<br />

Upon receipt, the lab will mount the custom impression<br />

coping on an implant analog (Fig. 21) and reseat it back<br />

into the impression (Fig. 22). A soft tissue model will be<br />

poured (Fig. 23), the case articulated, and the final restoration<br />

fabricated.<br />

Figure 11: Custom temporary abutment and BioTemps crown<br />

Based on the clinician’s preference, a cemented or screwretained<br />

prosthesis can be ordered. In this case, the<br />

cemented restoration consisted of an Inclusive ® All-Zirconia<br />

Custom Abutment (Figs. 24a, 24b) and an IPS e.max ® crown<br />

(Ivoclar Vivadent; Amherst, N.Y.) (Fig. 25). An acrylic jig is<br />

fabricated to aid in seating the abutment (Figs. 26a, 26b).<br />

Final Delivery: Cement-Retained Crown<br />

When the healing abutment or provisional restoration<br />

is removed, the soft tissues will have healed to more<br />

Figure 12: After adjustments, a hole is drilled through the crown and the<br />

crown cemented to the abutment.<br />

22<br />

– www.inclusivemagazine.com –

Figure 13: Seated provisional restoration<br />

Figure 17: Custom impression coping<br />

Figure 14: The abutment screw is tightened<br />

Figure 18: The impression coping is seated<br />

Figure 15: The occlusal access opening is sealed<br />

Figure 19: The screw access opening is sealed with soft wax<br />

Figure 16: The temporary crown is out of occlusion<br />

Figure 20: Shade selection<br />

– Restoring Mandibular Single Teeth with the Inclusive Tooth Replacement Solution – 23

anatomically correct contours (Fig. 27). The abutment is<br />

seated utilizing the jig (Fig. 28) and the screw tightened<br />

to 35 Ncm (Fig. 29). The jig is then removed (Fig. 30). The<br />

crown is seated and the margins and interproximal and<br />

occlusal contacts are checked (Figs. 31a, 31b). Any necessary<br />

adjustments are made. There should be light centric contact<br />

with a firm bite and no lateral contacts. The interproximal<br />

contacts should be light. The abutment screw is tightened<br />

once more to 35 Ncm, and the access opening sealed with<br />

a piece of Teflon tape. The crown is cemented in place<br />

with RelyX Unicem Self-Adhesive Resin Cement (3M ESPE;<br />

St. Paul, Minn.). All excess cement must be meticulously<br />

removed. A PA was taken to verify complete seating and<br />

cement removal (Fig. 32).<br />

Final Delivery:<br />

IPS e.max Screw-Retained Crown<br />

If a screw-retained crown was selected (Figs. 33a–33c), the<br />

one-piece restoration is seated on the implant (Fig. 34). The<br />

abutment screw is tightened to 35 Ncm utilizing the jig<br />

(Fig. 35). The interproximal and occlusal contacts are<br />

checked and adjusted as needed (Fig. 36). The screw access<br />

opening is sealed with a piece of Teflon tape and an occlusal<br />

composite (Fig. 37).<br />

Figure 22: Assembly reseated into impression<br />

Summary<br />

Replacement of missing mandibular molars with singletooth<br />

implant-borne restorations provides many benefits<br />

over fixed partial dentures. It avoids having to prep adjacent<br />

teeth, it makes hygiene easier for the patient, and it allows<br />

for flexure of the mandible. 2 The osteotomy can be created<br />

conventionally or through a guided surgical procedure.<br />

The Inclusive Tooth Replacement Solution provides the<br />

components to simplify the restorative process and provide<br />

a superior final restoration for this common restoration. IM<br />

Figure 23: Soft tissue model<br />

Figures 24a, 24b: Inclusive All-Zirconia Custom Abutment<br />

Figure 21: Custom impression coping mounted on implant analog<br />

Figure 25: Inclusive All-Zirconia Custom Abutment and IPS e.max crown<br />

24<br />

– www.inclusivemagazine.com –

Figures 26a, 26b: Acrylic abutment seating jig<br />

Figure 30: The jig is removed<br />

Figure 27: The provisional restoration is removed<br />

Figures 31a, 31b: After adjustments, the IPS e.max crown is cemented in place<br />

Figure 28: The abutment is seated with the jig<br />

Figure 32: PA verifying seating and cement removal<br />

Figure 29: The abutment screw is tightened to 35 Ncm<br />

Figures 33a–33c: IPS e.max screw-retained crown<br />

– Restoring Mandibular Single Teeth with the Inclusive Tooth Replacement Solution – 25

References<br />

1. Becker W, Becker BE. Replacement of maxillary and mandibular molars with single<br />

endosseous implant restorations: a retrospective study. J Prosthet Dent. 1995 Jul;<br />

74(1):51–55.<br />

2. Misch CE, Misch-Dietsh F, Silc J, Barboza E, Cianciola LJ, Kazor C. Posterior<br />

implant single-tooth replacement and status of adjacent teeth during a 10-year<br />

period: a retrospective report. J Periodontol. 2008 Dec;79(12):2378-82.<br />

3.Misch CE. Endosteal implants for posterior single tooth replacement: alternatives,<br />

indications, contraindications, and limitations. J Oral Implantol. 1999;25(2):80-94.<br />

4. Ekfeldt A, Carlsson GE, Börjesson G. Clinical evaluation of single tooth restorations<br />

supported by osseointegrated implants: a retrospective study. Int J Oral<br />

Maxillofac Implants. 1994 Mar-Apr;9(2):179–83.<br />

5. Muftu A, Chapman RJ. Replacing posterior teeth with freestanding implants: fouryear<br />

prosthodontic results of a prospective study. J Am Dent Assoc. 1998 Aug;<br />

129(8):1097–102.<br />

6. Jansen C. Presentation given at the Academy of Osseointegration 2012 Annual<br />

Meeting, Phoenix, Ariz.<br />

7. Anderson LC, Kosinski TF, Mentag PJ. A review of the intraosseous course of the<br />

nerves of the mandible. J Oral Implantol. 1991;17(4):394-403.<br />

8. Alhassani AA, AlGhamdi AS. Inferior alveolar nerve injury in implant dentistry: diagnosis,<br />

causes, prevention, and management. J Oral Implantol. 2010;36(5):401-7.<br />

Epub 2010 Jun 14.<br />

Figure 34: Abutment screw tightened utilizing jig<br />

Figure 35: IPS e.max screw-retained crown seated<br />

Figure 36: Occlusion verified<br />

Figure 37: Access opening sealed with composite<br />

26<br />

– www.inclusivemagazine.com –

IMPLANT POSITION<br />

IN THE ESTHETIC ZONE<br />

Go online for<br />

in-depth content<br />

by<br />

Siamak Abai, DDS, MMedSc<br />

Since the advent of modern root<br />

form osseointegrated implant<br />

dentistry in 1952 by Per-Ingvar<br />

Brånemark 1 and colleagues, clinicians<br />

have strived for improvements in<br />

implant positioning in the esthetic<br />

zone to achieve predictable restorative<br />

and esthetic results. Years of clinical<br />

experience in congruence with controlled<br />

clinical studies have led to<br />

established parameters as a guide<br />

for these results. Prosthetic treatment<br />

planning and establishing a set clinical<br />

protocol prior to implant placement<br />

are paramount. It is important to note<br />

that proper implant positioning is<br />

patient- and often implant-specific, and<br />

that inter-patient generalizations can<br />

result in myopic treatment planning<br />

and decrease the predictability of an<br />

esthetic outcome.<br />

Treatment planning prior to implant placement traditionally<br />

begins with comprehensive medical and dental evaluation,<br />

articulated diagnostic casts, periapical and panoramic radiographs,<br />

cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) scans, and<br />

a diagnostic wax-up. Patient demands must always be taken<br />

into consideration prior to surgery, and presurgical mockups<br />

may be necessary to convey the information to the patient.<br />

Prosthetic treatment planning helps the clinician with a<br />

restorative-driven implant placement rather than a bonedriven<br />

approach, with the latter leading to poor abutment<br />

angulations and drastically reduced restorative options. Bone<br />

augmentation is often necessary in order to achieve optimal<br />

residual ridge dimensions prior to implant placement.<br />

The inventive work of Sir Godfrey Hounsfield 2 and the<br />

advancement of CBCT technology have led the dental<br />

profession into a new realm of dimensional accuracy that<br />

is often unattainable with conventional dental radiography.<br />

In combination with the use of a surgical or guided stent,<br />

proper 3-D positioning of a dental implant has become<br />

an attainable goal, leading to increased confidence for<br />

the clinician and accurate clinical results. The importance<br />

– Implant Position in the Esthetic Zone – 27

IMPLANT POSITION IN THE ESTHETIC ZONE<br />

of the implant position can be manifested in the four<br />

dimensionally sensitive positioning criteria: mesiodistal,<br />

labiolingual, and apico-coronal location, as well as implant<br />

angulation. 3 The ultimate goal is not only to avoid adjacent<br />

sensitive structures, but to respect the biological principles<br />

that have been established to achieve esthetic results.<br />

MESIODISTAL CRITERIA<br />

Correct implant position in a mesiodistal orientation allows<br />

the clinician to avoid iatrogenic damage to adjacent critical<br />

structures. Maintaining adequate distance from adjacent<br />

teeth also helps preserve crestal bone and interproximal<br />

papillary height. When placing an implant adjacent to a<br />

tooth, it has been shown that crestal bone peak is based on<br />

and maintained by the bone level of the teeth adjacent to<br />

the missing space. A minimum distance of 1.5 mm between<br />

implant and existing dentition has been determined to<br />

prevent damage to the adjacent teeth and to provide proper<br />

osseointegration and gingival contours 4–6 (Fig. 1a). Implants<br />

placed too closely together can reduce the height of the<br />

inter-implant bone crest, and a distance of less than 3 mm<br />

between two adjacent implants leads to increased bone<br />

loss. It has been shown that a distance of more than 3 mm<br />

between two adjacent implants preserves the interproximal<br />

bone peak and results in 0.45 mm of resorption on average,<br />

giving a better chance of proper interproximal papillary<br />

height (Fig. 1b). If the space between implants is 3 mm<br />

or less, the average resorption of the interproximal bone<br />

peak increases to 1.04 mm, compromising support for the<br />

interdental papilla. 4,7 As a result, wide-bodied implants less<br />

than 3 mm apart in the esthetic zone would compromise<br />

the desired outcome.<br />

LABIOLINGUAL CRITERIA<br />

Labiolingual implant position is often determined by the<br />

gingival biotype, occlusal considerations of opposing teeth,<br />

and desired emergence profile. An implant placed too far<br />

labially can cause bone dehiscence and gingival recession<br />

leading to exposure or show-through of the implant collar.<br />

An implant placed too far lingually can cause prosthetic<br />

difficulties with ridge-lap restorations that can be unhygienic<br />

and unesthetic. A thickness of 1.8 mm of labial bone has<br />

been determined to be critical in maintaining an implant soft<br />

tissue profile and increasing the likelihood of an esthetic<br />

outcome 8 (Fig. 2). Labially oriented implants compromise<br />

the subgingival emergence profile development, creating<br />

long crowns and misalignment of the collar with respect to<br />

the adjacent teeth. 9<br />

APICO-CORONAL CRITERIA<br />

Peri-implant crestal bone stability plays a critical role in the<br />

presence of interdental papilla. 10 Many factors contribute<br />

to crestal bone resorption, including existing anatomy, surgical<br />

trauma, overloading, peri-implantitis, implant surface<br />

characteristics, microgap at the implant-abutment junction,<br />

Figure 1a: Minimum distance of 1.5 mm between implant and existing dentition<br />

Figure 1b: Minimum distance of 3 mm between two adjacent implants<br />

Figure 2: Proper labiolingual placement with 1.8 mm thickness of labial bone<br />

28<br />

– www.inclusivemagazine.com –

type of connection between implant, and prosthetic components.<br />

11 Several factors are cause for concern in the<br />

apico-coronal placement of implants. Implants placed too<br />

shallow may reveal the metal collar of the implant through<br />

the gingiva. Countersinking implants below the level of<br />

the crestal bone may give prosthetic advantages with more<br />

running room for prosthetic components and tissue contouring,<br />

but can lead to crestal bone loss due to the location<br />

of a microgap at the implant-abutment interface. The<br />

ideal solution to exposure of the implant collar would be<br />

the placement of an implant equicrestal or subcrestal to<br />

the ridge. However, the existing microgap at the implantabutment<br />

junction leads to bone resorption due to periimplant<br />

inflammation. 12 It is suggested that an implant collar<br />

be located 2 mm apical to the CEJ of an adjacent tooth<br />

if no gingival recession is present 13 (Fig. 3). Implant diameter<br />

also plays a role in apico-coronal position, with smaller<br />

diameter implants needing more space for soft-tissue development<br />

and tissue contouring.<br />

Figure 4: Proper implant angulation with screw access in the cingulum area<br />

Figure 3: Lateral view of implant placed with the collar at the level of crestal bone<br />

with adjacent teeth CEJ 2 mm coronal to the collar of the implant<br />

IMPLANT ANGULATION<br />

Implant angulation is particularly important in treatment<br />

planning for screw-retained restorations. Implants angled<br />

too far labially compromise the placement of the restorative<br />

screw, leaving the clinician with fewer restorative options.<br />

Implants angled too far lingually can result in unhygienic<br />

and unesthetic prosthetic design. For every millimeter<br />

of lingual inclination, the implant should be placed an<br />

additional millimeter apically in order to create an optimal<br />

emergence profile. 14 In general, implant angulation should<br />

mimic angulation of adjacent teeth so long as they are<br />

in reasonable alignment (Fig. 4). Furthermore, maxillary<br />

anterior regions require a subtle palatal angulation to<br />

INCLUSIVE TOOTH<br />

REPLACEMENT SOLUTION<br />

The Inclusive ® Tooth Replacement Solution was developed<br />

by <strong>Glidewell</strong> Laboratories as a complete, prosthetically<br />

driven method of restoring missing dentition. The solution<br />

comprises treatment planning, implant placement, patientspecific<br />

temporization, and the definitive restoration<br />

(Figs. 5a–5f). When utilizing the comprehensive range of<br />

Inclusive Digital Treatment Planning services for guided<br />

implant surgeries and restorations, the clinician has absolute<br />

and precise control of each step. This results in an efficient<br />

and accurate workflow that is beneficial for the clinician and,<br />

ultimately, the patient. With the Inclusive Tooth Replacement<br />

Solution, the clinician has control of the four dimensions of<br />

implant placement in the esthetic zone, creating a consistently<br />

predictable result. Having a single source of services and<br />

materials is also advantageous in providing a more affordable<br />

yet high-value product for patients.<br />

increase labial soft tissue bulk. 15 – Implant Position in the Esthetic Zone – 29

IMPLANT POSITION IN THE ESTHETIC ZONE<br />

Figure 5a: Inclusive Tapered Implant at placement<br />

Figure 5b: Inclusive custom healing abutment in place<br />

Figure 5c: Contoured soft tissue sulcus after healing<br />

Figure 5d: Screw-retained IPS e.max ® crown (Ivoclar<br />

Vivadent; Amherst, N.Y.) in place<br />

Figure 5e: PA to verify seating of crown<br />

Figure 5f: Buccal view of final restoration at delivery<br />

IM<br />

REFERENCES<br />

1. Albrektsson T, Brånemark PI, Hansson HA, Lindstrom J. Osseointegrated titanium<br />

implants. Requirements for ensuring a long-lasting, direct bone-to-bone<br />

implant anchorage in man. Acta Orthop Scand. 1981;52(2):155-70.<br />

2. Hounsfield GN. Computerized transverse axial scanning (tomography): Part I.<br />

Description of system. Br J Radiol .1973;46:1016-22.<br />

3. Al-Sabbagh M. Implants in the esthetic zone. Dent Clin N Am. 2006 Jul;50(3):<br />

391-407.<br />

4. Tarnow DP, Cho SC, Wallace SS. The effect of inter-implant distance on the<br />

height of inter-implant bone crest. J Periodontol. 2000 Apr;71(4):546-49.<br />

5. Spray JR, Black CG, Morris HF, Ochi S. The influence of bone thickness on<br />

facial marginal bone response: stage 1 placement through stage 2 uncovering.<br />

Ann Periodontol. 2000 Dec;5(1):119–28.<br />

6. Saadoun AP, LeGall M, Touati B. Selection and ideal tridimensional implant position<br />

for soft tissue aesthetics. Pract Periodontics Aesthet Dent. 1999 Nov-Dec;<br />

11(9):1063-72.<br />

7. Degidi M, Perrotti V, Shibli JA, Novaes AB, Piatelli A, Lezzi G. Equicrestal and<br />

subcrestal dental implants: a histologic and histomorphometric evaluation of<br />

nine retrieved human implants. J Periodontol. 2011 May;82(5):708-15. Epub<br />

2010 Dec 7.<br />

8. Hermann JS, Buser D, Schenk RK, Schoolfield JD, Cochran DL. Biological width<br />

around one- and two-piece titanium implants. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2001 Dec;<br />

12(6):559-71.<br />

9. Kazor CE, Al-Shammari K, Sarment DP, Misch CE, Wang HL. Implant plastic<br />

surgery: a review and rationale. J Oral Implantol. 2004;30(4):240-54.<br />

10. Berglundh T, Lindhe J. Dimension of the periimplant mucosa. Biological width<br />

revisited. J Clin Periodontol. 1996 Oct;23(10):971-73.<br />

11. Hermann F, Lerner H, Palti A. Factors influencing the preservation of the<br />

periimplant marginal bone. Implant Dent. 2007 Jun;16(2):165-75.<br />

12. Broggini N, McManus LM, Hermann JS, Medina RK, Buser D, Cochran DL.<br />

Peri-implant inflammation defined by the implant-abutment interface. J Dent<br />

Res. 2006 May;85(5):473-78.<br />

13. Saadoun AP, LeGall M, Touati B. Selection and ideal tridimensional implant<br />

position for soft tissue aesthetics. Pract Periodontics Aesthet Dent. 1999<br />

Nov-Dec;11(9):1063-72.<br />

14. Potashnick SR. Soft tissue modeling for the esthetic single-tooth implant restoration.<br />

J Esthet Dent. 1998;10(3):121-31.<br />

15. Tishler M. <strong>Dental</strong> implants in the esthetic zone. Considerations for form and<br />

function. N Y State Dent J. 2004 Mar;70(3):22-6.<br />

30<br />

– www.inclusivemagazine.com –

SMALL DIAMETER<br />

implants<br />

Planning from the<br />

Prosthetic Perspective<br />

with Bradley C. Bockhorst, DMD<br />

Whether you’re placing small-diameter or conventionaldiameter<br />

implants for an overdenture, the case must be<br />

planned from surgical and prosthetic perspectives. The<br />

restorative aspect of the Inclusive ® Mini Implant involves<br />

encasing the O-ring housings within the denture base and<br />

creating a parallel line of draw.<br />

O-ring Housing Dimensions<br />

4.75 mm<br />

The height of the O-ring housing is 3.5 mm (Fig. 1). There<br />

is a space of approximately 1.0 mm between the top of<br />

the collar and the base of the O-ring housing to allow<br />

the housing to be rotated in cases where the implants<br />

are divergent. The housings can accommodate up to<br />

30 degrees of angular divergence between implants.<br />

However, the implants should be placed parallel to one<br />

another as much as possible to provide an ideal prosthetic<br />

fit and to avoid excessive wearing of the O-rings.<br />

There should be a minimum of 3 mm thickness of acrylic<br />

in the denture base above the housing to provide adequate<br />

strength to the prosthesis. Therefore, there should be at<br />

least 8 mm of vertical space from the top of the collar. The<br />

denture teeth would be in addition to this space.<br />

1.0 mm<br />

Figure 1: O-ring housing with 3.5 mm height<br />

3.5 mm<br />

– Small Diameter Implants: Planning from the Prosthetic Perspective – 31

Figure 2a: Cast framework<br />

Figure 2b: Framework incorporated into overdenture<br />

Providing implant-retained<br />

overdentures can be one of the<br />

most professionally rewarding<br />

aspects of your practice.<br />

Figure 3: Virtual framework design with strut over attachment housing<br />

If vertical space is lacking, a cast framework can be incorporated<br />

into the new denture to provide strength (Figs. 2a, 2b).<br />

Frameworks are designed to have a strut over the top of the<br />

attachment housing (Fig. 3).<br />

In mandibular overdenture cases, it is customary to place<br />

four mini implants within the symphysis area with as wide<br />

an anterior-posterior spread as possible while still ensuring<br />

an adequate margin of safety from the nerve (Fig. 4a).<br />

In maxillary overdenture cases, it is customary to place six<br />

mini implants anterior to the sinuses (Fig. 4b). The O-ring<br />

housings are 4.75 mm in diameter, and there should be at<br />

least 2 mm of acrylic between these metal housings in the<br />

denture base (Fig. 5). Therefore, the centers of the implants<br />

should be at least 7 mm apart.<br />

Providing implant-retained overdentures can be one of<br />

the most professionally rewarding aspects of your practice<br />

— and it can be life-changing for your patients. Planning<br />

from both the prosthetic perspective and the surgical<br />

perspective will help the cases go smoothly and minimize<br />

future complications. IM<br />

32<br />

– www.inclusivemagazine.com –

Mandibular Spacing<br />

Maxillary Spacing<br />

Figure 4a: Typical placement of mini implants in the mandible<br />

Figure 4b: Typical placement of mini implants in the maxilla<br />

Figure 5: Digital treatment plan for four Inclusive Mini Implants in an edentulous mandible. Cross-sectional view (upper right quadrant) shows O-ring housing well positioned<br />

within the denture base.<br />

– Small Diameter Implants: Planning from the Prosthetic Perspective – 33

CLINICAL<br />

TIP<br />

Bone Quality Based Drilling Protocol:<br />

Achieving High Primary Stability<br />

by<br />

Darrin M. Wiederhold, DMD, MS<br />

Figure 1:<br />

Planning software<br />

used to evaluate<br />

relative bone<br />

density showing<br />

Type IV bone<br />

ONE OF THE MOST FUNDAMENTAL PROCEDURES performed<br />

by implant surgeons is the creation of the osteotomy for<br />

implant placement. Without a well-developed osteotomy<br />

site, both the immediate surgical and future restorative<br />

success of the case can be compromised. There are various<br />

factors that must be considered when performing the<br />

osteotomy, such as location, angulation, and spacing for<br />

multiple implants. Critical decisions to be made concern the<br />

choice of whether to follow the soft or dense bone protocol<br />

for a given case, and whether to utilize a bone tap drill. The<br />

goal is to achieve high primary stability, at least 35 Ncm,<br />

at the time of implant placement. This will also impact the<br />