Environmental Kuznets curves—real progress or passing the buck ...

Environmental Kuznets curves—real progress or passing the buck ...

Environmental Kuznets curves—real progress or passing the buck ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Ecological Economics 25 (1998) 177–194<br />

ANALYSIS<br />

<strong>Environmental</strong> <strong>Kuznets</strong> <strong>curves—real</strong> <strong>progress</strong> <strong>or</strong> <strong>passing</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>buck</strong>?<br />

A case f<strong>or</strong> consumption-based approaches<br />

Dale S. Rothman *<br />

Enironment Canada’s Enironmental Adaptations Research Group and <strong>the</strong> Uniersity of British Columbia’s Sustainable Deelopment R<br />

esearch Institute, B5-2202 Main Mall, Vancouer, BC V6T 1Z4, Canada<br />

Abstract<br />

Recent research has examined <strong>the</strong> hypo<strong>the</strong>sis of an environmental <strong>Kuznets</strong> curve (EKC)—<strong>the</strong> notion that<br />

environmental impact increases in <strong>the</strong> early stages of development followed by declines in <strong>the</strong> later stages. These<br />

studies have focused on <strong>the</strong> relationship between per capita income and a variety of environmental indicat<strong>or</strong>s. Results<br />

imply that EKCs may exist f<strong>or</strong> a number of cases. However, <strong>the</strong> measures of environmental impact used generally<br />

focus on production processes and reflect environmental impacts that are local in nature and f<strong>or</strong> which abatement is<br />

relatively inexpensive in terms of monetary costs and/<strong>or</strong> lifestyle changes. Significantly, m<strong>or</strong>e consumption-based<br />

measures, such CO 2 emissions and municipal waste, f<strong>or</strong> which impacts are relatively easy to externalize <strong>or</strong> costly to<br />

control, show no tendency to decline with increasing per capita income. By considering consumption and trade<br />

patterns, <strong>the</strong> auth<strong>or</strong> re-examines <strong>the</strong> concept of <strong>the</strong> EKC and proposes <strong>the</strong> use of alternative, consumption-based<br />

measures of environmental impact. The auth<strong>or</strong> speculates that what appear to be improvements in environmental<br />

quality may in reality be indicat<strong>or</strong>s of increased ability of consumers in wealthy nations to distance <strong>the</strong>mselves from<br />

<strong>the</strong> environmental degradation associated with <strong>the</strong>ir consumption. © 1998 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved.<br />

Keyw<strong>or</strong>ds: <strong>Environmental</strong> <strong>Kuznets</strong> curves; Consumption; Trade; <strong>Environmental</strong> impact measures<br />

1. Introduction<br />

Will we grow out of our environmental problems?<br />

Is <strong>the</strong> fastest road to a clean environment<br />

* Tel: +1 604 8221685; fax: +1 604 8229191; e-mail:<br />

daler@sdri.ubc.ca<br />

along <strong>the</strong> path of rapid development and increased<br />

incomes?<br />

These are <strong>the</strong> underlying questions raised by<br />

research done on what is called <strong>the</strong> environmental<br />

<strong>Kuznets</strong> curve (EKC) hypo<strong>the</strong>sis. The basic notion<br />

of this hypo<strong>the</strong>sis is that resource use increases<br />

and environmental degradation w<strong>or</strong>sens<br />

during <strong>the</strong> early stages of development, to be<br />

0921-8009/98/$19.00 © 1998 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved.<br />

PII S0921-8009(97)00179-1

178<br />

D.S. Rothman / Ecological Economics 25 (1998) 177–194<br />

1 The name ‘<strong>Kuznets</strong>’ is from Simon <strong>Kuznets</strong>, <strong>the</strong> economist<br />

who postulated that increases in economic inequality in early<br />

stages of development are followed by decreases in later stages<br />

(<strong>Kuznets</strong>, 1955). The EKC hypo<strong>the</strong>sis is also known as <strong>the</strong><br />

inverted-U hypo<strong>the</strong>sis because plotting a measure of resource<br />

use <strong>or</strong> environmental degradation, which follows this pattern,<br />

against a measure of development, usually per capita GDP,<br />

results in an inverted-U shape.<br />

followed by improvements in <strong>the</strong> later stages 1 .<br />

The fundamental implication appears to be that<br />

we can simply ‘grow’ out of any limitations related<br />

to natural resources <strong>or</strong> environmental<br />

degradation. To be fair, most of <strong>the</strong> researchers<br />

who have examined <strong>the</strong> EKC hypo<strong>the</strong>sis and<br />

o<strong>the</strong>rs point out that this will not ‘simply’ happen<br />

(Grossman, 1995; Grossman and Krueger,<br />

1992, 1994, 1996; Shafik, 1994). However,<br />

Panayotou (1993) is confident enough to state<br />

that EKC-type behavi<strong>or</strong> is ‘an inevitable result<br />

of structural change accompanying economic<br />

growth’ and Beckerman (1992) relies on some<br />

of <strong>the</strong> results of this literature to state that ‘<strong>the</strong><br />

strong c<strong>or</strong>relation between incomes and <strong>the</strong> extent<br />

to which environmental protection measures<br />

are adopted demonstrates that, in <strong>the</strong><br />

longer run, <strong>the</strong> surest way to improve your environment<br />

is to become rich’.<br />

In this paper, it is argued that <strong>the</strong> w<strong>or</strong>k<br />

done to date has actually been quite limited<br />

and, in some ways, counter-productive. Following<br />

on <strong>the</strong> discussion by Saint-Paul (1995) regarding<br />

Grossman (1995), <strong>the</strong> auth<strong>or</strong> focuses<br />

specifically on <strong>the</strong> premise that EKCs are attributable<br />

in some measure to changes in <strong>the</strong><br />

production structure of economies. The study<br />

begins with a brief review of <strong>the</strong> literature on<br />

<strong>the</strong> EKC hypo<strong>the</strong>sis and some of <strong>the</strong> concerns<br />

which have been raised over this w<strong>or</strong>k and <strong>the</strong><br />

implications of its conclusions. It is <strong>the</strong>n asserted<br />

that consumption is <strong>the</strong> principal driving<br />

f<strong>or</strong>ce behind environmental impact and that<br />

<strong>the</strong>re is much to be learned by taking a consumption-<br />

ra<strong>the</strong>r than production-based approach,<br />

as earlier studies have predominantly<br />

done. Because it is trade that allows f<strong>or</strong> a divergence<br />

of production and consumption patterns<br />

within a region, this leads to a discussion<br />

of how to consider <strong>the</strong> role of trade in <strong>the</strong><br />

context of <strong>the</strong> EKC hypo<strong>the</strong>sis. The auth<strong>or</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong>n proposes possibilities f<strong>or</strong> m<strong>or</strong>e appropriate<br />

measures of environmental impacts and considers<br />

<strong>the</strong> results using one such measure.<br />

2. A brief review of previous analyses of <strong>the</strong> EKC<br />

hypo<strong>the</strong>sis<br />

Several auth<strong>or</strong>s have reviewed <strong>the</strong> literature<br />

on <strong>the</strong> EKC in some detail (F<strong>or</strong>rest, 1995;<br />

Stern et al., 1996; Ekins, 1997). In addition,<br />

<strong>the</strong>re have been three policy f<strong>or</strong>ums on this issue<br />

spurred by an article in ‘Science’ auth<strong>or</strong>ed<br />

by Ken Arrow and o<strong>the</strong>r luminaries (Arrow et<br />

al., 1995; Various, 1995, 1996a,b).<br />

The overall conclusion of <strong>the</strong> first set of<br />

studies on <strong>the</strong> EKC hypo<strong>the</strong>sis is that some environmental<br />

indicat<strong>or</strong>s, e.g. access to clean water,<br />

urban sanitation and urban air quality, do<br />

indeed show improvement with increased income,<br />

with <strong>or</strong> without an initial period of deteri<strong>or</strong>ation.<br />

O<strong>the</strong>r indicat<strong>or</strong>s, however, show<br />

continued w<strong>or</strong>sening as incomes rise (e.g. carbon<br />

dioxide emissions and municipal waste per<br />

capita). The turning point at which environmental<br />

improvement begins varies from study<br />

to study, but most often falls in <strong>the</strong> income<br />

range typical of middle-income countries. Most<br />

environmental conditions that do improve with<br />

economic growth are those that have local impacts<br />

and abatement costs that are relatively inexpensive<br />

in terms of money and changes in<br />

lifestyle. <strong>Environmental</strong> problems that improve<br />

only at higher income levels <strong>or</strong> that continue to<br />

w<strong>or</strong>sen as incomes rise generally create impacts<br />

that affect only a few people, e.g. solid waste,<br />

<strong>or</strong> that are separated by ei<strong>the</strong>r space and/<strong>or</strong><br />

time from those creating <strong>the</strong> pressures on <strong>the</strong><br />

environment, e.g. carbon dioxide emissions. A<br />

number of <strong>the</strong> results also indicate a possible<br />

N-shaped relationship, whereby <strong>the</strong> indicat<strong>or</strong> of<br />

resource use <strong>or</strong> environmental stress begins to<br />

w<strong>or</strong>sen again at higher incomes (Grossman and<br />

Krueger, 1992, 1994; Shafik and Bandyopadhyay,<br />

1992; Grossman, 1995; de Bruyn and Opscho<strong>or</strong>,<br />

1997).

D.S. Rothman / Ecological Economics 25 (1998) 177–194 179<br />

The results and underlying assumptions of <strong>the</strong>se<br />

studies have been subject to a number of concerns.<br />

These include, <strong>the</strong> statistical relationships<br />

examined (Stern et al., 1996), <strong>the</strong> focus on pollutant<br />

emissions and concentrations and <strong>the</strong> associated<br />

lack of w<strong>or</strong>k on <strong>the</strong> depletion of resource<br />

stocks (Arrow et al., 1995), <strong>the</strong> spatial and/<strong>or</strong><br />

temp<strong>or</strong>al separation between many economic activities<br />

and <strong>the</strong>ir environmental impacts (Diwan<br />

and Shafik, 1992; Ayres, 1995; Farber, 1995;<br />

Max-Neef, 1995; Mintzer, 1995), <strong>the</strong> limited scope<br />

of <strong>the</strong> measures of environmental degradation<br />

(Opscho<strong>or</strong>, 1995; Karr and Thomas, 1996; O’Neill<br />

et al., 1996; Orians, 1996; Pulliam and O’Malley,<br />

1996; Schindler, 1996) and <strong>the</strong> emphasis on economic<br />

growth ra<strong>the</strong>r than human well-being<br />

(Lash, 1995; Max-Neef, 1995; Pulliam and O’Malley,<br />

1996).<br />

Concerns have also been raised about <strong>the</strong> implications<br />

of <strong>the</strong> results, often by <strong>the</strong> researchers<br />

<strong>the</strong>mselves. Many of <strong>the</strong> analyses consider only<br />

impacts on a per capita <strong>or</strong> per unit of economic<br />

activity basis, leaving open <strong>the</strong> question of<br />

changes in <strong>the</strong> total impact on <strong>the</strong> environment<br />

(Holtz-Eakin and Selden, 1992; Shafik and<br />

Bandyopadhyay, 1992; Panayotou, 1993; Selden<br />

and Song, 1994). Secondly, if <strong>the</strong> reductions to<br />

date are primarily due to a composition effect,<br />

whereby countries tend to increase <strong>the</strong> energy and<br />

pollution intensity of <strong>the</strong>ir imp<strong>or</strong>ts, to what extent<br />

will <strong>the</strong> currently developing countries be able to<br />

replicate this pattern (Ayres, 1995; Farber, 1995;<br />

Grossman, 1995; Max-Neef, 1995; Saint-Paul,<br />

1995; Stern et al., 1996)? Thirdly, given <strong>the</strong> many<br />

potential irreversibilities resulting from resource<br />

use and environmental degradation, what will be<br />

<strong>the</strong> price paid along <strong>the</strong> way and is <strong>the</strong> necessary<br />

growth in <strong>the</strong> developing economies even possible<br />

(Holtz-Eakin and Selden, 1992; Panayotou, 1993;<br />

Selden and Song, 1994; Farber, 1995; Schindler,<br />

1996; Stern et al., 1996; Roberts and Grimes,<br />

1997)? 2 Finally, given that most of <strong>the</strong> researchers<br />

acknowledge <strong>the</strong> changes in social and political<br />

institutions required to bring about a decrease in<br />

<strong>the</strong> impact of economic activity on <strong>the</strong> environment,<br />

fur<strong>the</strong>r analysis will be required to provide<br />

useful insights on how to best bring <strong>the</strong>se about<br />

(Lash, 1995; Munasinghe, 1995; Daily et al., 1996;<br />

Fuentes-Quezada, 1996; Karr and Thomas, 1996;<br />

Ludwig, 1996).<br />

3. Production-based versus consumption-based<br />

approaches to examining <strong>the</strong> EKC hypo<strong>the</strong>sis<br />

It is <strong>the</strong> second of <strong>the</strong>se concerns, that of <strong>the</strong><br />

imp<strong>or</strong>tance of changing composition, that is addressed<br />

in this paper. Whereas most of <strong>the</strong> analyses<br />

have focused on <strong>the</strong> environmental impact<br />

resulting from production within a country, it is<br />

m<strong>or</strong>e appropriate to consider <strong>the</strong> impacts stemming<br />

from consumption activities. It is possible to<br />

draw a parallel between <strong>the</strong> current discussions of<br />

<strong>the</strong> EKC, which tend to focus on production and<br />

a longer standing debate about <strong>the</strong> sources of<br />

human impact on <strong>the</strong> environment, which emphasizes<br />

consumption. However, <strong>the</strong> resulting conclusions<br />

and interpretations differ significantly.<br />

3.1. The production-based approach<br />

Grossman and Krueger (1992) speak of <strong>the</strong><br />

scale of economic activity, <strong>the</strong> composition of<br />

economic activity and <strong>the</strong> techniques of production<br />

in examining <strong>the</strong> possible reasons behind <strong>the</strong><br />

inverted-U shape characteristic of <strong>the</strong> EKC 3 .Itis<br />

generally argued that <strong>the</strong> changing composition of<br />

production combined with reductions in <strong>the</strong><br />

amount of energy and resources used and pollution<br />

produced per unit of production are <strong>the</strong><br />

driving f<strong>or</strong>ces behind <strong>the</strong> EKC relationship<br />

(Grossman and Krueger, 1992, 1994; Radetzki,<br />

1992; Panayotou, 1993; Grossman, 1995). As<br />

Figs. 1 and 2 illustrate with time series and cross-<br />

2 Holtz-Eakin and Selden (1992) and Selden and Song<br />

(1994) uses <strong>the</strong>ir results to f<strong>or</strong>ecast future emissions of carbon<br />

dioxide, sulfur dioxide, suspended particulates, oxides of nitrogen<br />

and carbon monoxide. Stern et al. (1996) use <strong>the</strong> results of<br />

Panayotou (1993) to estimate future rates of def<strong>or</strong>estation<br />

and sulfur dioxide emission. Each of <strong>the</strong>se studies concludes<br />

that emission and f<strong>or</strong>est destruction at a global level will<br />

increase significantly in <strong>the</strong> near future, with stabilization and<br />

decline occurring only in <strong>the</strong> long run, if at all.<br />

3 Panayotou (1993) discusses this decomposition.

180<br />

D.S. Rothman / Ecological Economics 25 (1998) 177–194<br />

Fig. 1. Hist<strong>or</strong>ical shares of GDP per sect<strong>or</strong> f<strong>or</strong> <strong>the</strong> US and <strong>the</strong> UK (Data from Maddison (1989, 1995)).<br />

sectional data, respectively, as economic development<br />

proceeds, i.e. income levels increase, <strong>the</strong><br />

dominant sect<strong>or</strong> tends to shift from agriculture to<br />

industry and <strong>the</strong>n to services. The first shift is<br />

likely to result in increased environmental impact,<br />

whereas <strong>the</strong> latter in reduction.<br />

Adding to this seemingly inevitable change in<br />

<strong>the</strong> structure of economies are improvements in<br />

technology over time and changing demands from<br />

<strong>the</strong> people within countries as <strong>the</strong>ir incomes rise.<br />

The latter effect presumes that environmental<br />

quality is characterized as a ‘n<strong>or</strong>mal’ good, i.e. <strong>the</strong><br />

demand f<strong>or</strong> environmental quality rises as consumers’<br />

income rises. This will have an impact on<br />

consumers’ preferences, which can have a direct<br />

effect on <strong>the</strong> structure of <strong>the</strong> economy via purchases<br />

in <strong>the</strong> market. Fur<strong>the</strong>rm<strong>or</strong>e, consumer<br />

preferences can have a strong indirect impact via<br />

<strong>the</strong> policy arena by calling f<strong>or</strong> <strong>the</strong> implementation<br />

of various taxes, tariffs, subsidies and regulations<br />

(Komen et al. (1996) f<strong>or</strong> an empirical example of<br />

w<strong>or</strong>k in this area). Finally, to satisfy this increasing<br />

demand f<strong>or</strong> a cleaner environment from <strong>the</strong><br />

populace, it is argued that nations have a greater<br />

capacity to remedy environmental problems as<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir economies develop, and also m<strong>or</strong>e rapid<br />

growth will mean a m<strong>or</strong>e rapid turnover of an<br />

older, dirtier technology stock with a newer,<br />

cleaner one 4 .<br />

Many of <strong>the</strong>se effects are implicit in <strong>the</strong> empirical<br />

w<strong>or</strong>k to date on <strong>the</strong> EKC. Very little explicit<br />

w<strong>or</strong>k has been undertaken to separate out <strong>the</strong><br />

imp<strong>or</strong>tance of <strong>the</strong> effects of changing composition<br />

and changing technology, however. A time trend<br />

intended to capture technology improvements has<br />

also been inc<strong>or</strong>p<strong>or</strong>ated in some of <strong>the</strong> research<br />

(Grossman and Krueger, 1992, 1994; Shafik and<br />

Bandyopadhyay, 1992; Cropper and Griffiths,<br />

4 See Radetzki (1992) and López (1994) f<strong>or</strong> fur<strong>the</strong>r discussions<br />

on why growth may actually benefit <strong>the</strong> environment,<br />

and also Diwan and Shafik (1992) f<strong>or</strong> a discussion on why<br />

po<strong>or</strong> nations b<strong>or</strong>row against nature ra<strong>the</strong>r than against future<br />

income. Sen (1995) comments on <strong>the</strong> imp<strong>or</strong>tance of a binding<br />

constraint—subsistence—in determining choices that may<br />

have environmental repercussions.

D.S. Rothman / Ecological Economics 25 (1998) 177–194 181<br />

Fig. 2. GDP by Sect<strong>or</strong> 1993 (W<strong>or</strong>ld Resources Institute, 1996).<br />

1994; Grossman, 1995; Suri and Chapman, 1996).<br />

Most of <strong>the</strong>se have concluded that <strong>the</strong>re has been<br />

a decline in environmental degradation over time,<br />

as expected. On <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r hand, Grossman and<br />

Krueger (1994) find an increasing trend f<strong>or</strong> urban<br />

particulate matter and a number of water pollutants,<br />

Shafik and Bandyopadhyay (1992) see one<br />

f<strong>or</strong> fecal colif<strong>or</strong>m concentrations in water, and<br />

Cropper and Griffiths (1994) get mixed results<br />

looking at def<strong>or</strong>estation rates. Grossman and<br />

Krueger (1992) do discuss changing composition,<br />

but look at this principally in a separate discussion<br />

of international trade, arguing that <strong>the</strong> data<br />

do not supp<strong>or</strong>t <strong>the</strong> hypo<strong>the</strong>sis that differences in<br />

environmental regulation are an imp<strong>or</strong>tant determinant<br />

of trade patterns. (A broader review of <strong>the</strong><br />

trade literature suggests that this conclusion is not<br />

accepted as a rule, however (Low, 1992; Folke et<br />

al., 1994; OECD, 1994). Due to its imp<strong>or</strong>tance,<br />

this issue is returned to in m<strong>or</strong>e depth later in this<br />

paper.)<br />

Selden et al. (1996) and (de Bruyn, 1997)<br />

provide notable exceptions in <strong>the</strong>ir decomposition<br />

of observed changes in aggregate and per capita<br />

emissions. Using data f<strong>or</strong> a number of air pollutants<br />

in <strong>the</strong> US, and going beyond Grossman and<br />

Krueger, Selden et al. (1996) fur<strong>the</strong>r decompose<br />

<strong>the</strong> technique effect into energy efficiency, energy<br />

mix and o<strong>the</strong>r technique effects, i.e. changes in<br />

emissions per unit output. They conclude that <strong>the</strong><br />

greatest effects have come from <strong>the</strong> technique<br />

effect, particularly <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r technique effect.<br />

Changes in sect<strong>or</strong>al composition have also had a<br />

noticeable effect, however, especially f<strong>or</strong> particulate<br />

matter and sulfur oxides. de Bruyn (1997)<br />

examines sulfur dioxide emissions in The Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands<br />

and Western Germany. He also concludes<br />

that shifts in technology have been dominant in<br />

explaining changes in <strong>the</strong>se emissions.<br />

3.2. The consumption-based approach<br />

Ehrlich and Holdren (1971), Holdren and<br />

Ehrlich (1974) introduced <strong>the</strong> I=PAT identity<br />

(commonly referred to as <strong>the</strong> Ehrlich equation),<br />

m<strong>or</strong>e than a quarter of a century ago. This iden-

182<br />

D.S. Rothman / Ecological Economics 25 (1998) 177–194<br />

tity relates environmental impact to population,<br />

affluence and technology. Ekins and Jacobs<br />

(1995) and Dietz and Rosa (1994), among o<strong>the</strong>rs,<br />

modify this identity to speak of consumption<br />

specifically ra<strong>the</strong>r than affluence, yielding <strong>the</strong><br />

equation I=PCT. The latter two terms can be<br />

expressed as GDP per capita and impact per unit<br />

of GDP. The composition of consumption has<br />

been included in some of <strong>the</strong> m<strong>or</strong>e recent f<strong>or</strong>mulations<br />

by stating consumption and technology as<br />

vect<strong>or</strong>s ra<strong>the</strong>r than scalars (Amalric (1995), Ekins<br />

and Jacobs (1995), Raskin (1995) f<strong>or</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r recent<br />

w<strong>or</strong>k considering <strong>the</strong> utility of and potential respecifications<br />

of <strong>the</strong> IPAT relationship).<br />

Although subject to some criticism and various<br />

revisions over <strong>the</strong> years, <strong>the</strong> IPAT relationship<br />

provides a basic reference f<strong>or</strong> considering <strong>the</strong><br />

impacts of human activity on <strong>the</strong> environment.<br />

The parallels between scale, composition and<br />

technique and population, consumption and technology<br />

are fairly obvious and may supp<strong>or</strong>t <strong>the</strong><br />

argument that ei<strong>the</strong>r a production- <strong>or</strong> consumption-based<br />

approach to examining <strong>the</strong> EKC hypo<strong>the</strong>sis<br />

would be equivalent. A fundamental<br />

philosophical problem exists, however, in adopting<br />

a production-based approach in expl<strong>or</strong>ing a<br />

hypo<strong>the</strong>sis such as <strong>the</strong> EKC. As Rees (1995),<br />

Daly (1996) and Duchin (1998) argue, ‘‘most environmental<br />

degradation can be traced to <strong>the</strong> behavi<strong>or</strong><br />

of consumers ei<strong>the</strong>r directly, through<br />

activities like <strong>the</strong> disposal of garbage <strong>or</strong> <strong>the</strong> use of<br />

cars, <strong>or</strong> indirectly through <strong>the</strong> production activities<br />

undertaken to satisfy <strong>the</strong>m’’ Duchin (1998).<br />

Goods and services will not be produced, bought,<br />

sold and traded across b<strong>or</strong>ders, unless <strong>the</strong>re is a<br />

demand f<strong>or</strong> <strong>the</strong>m 5 .<br />

Ekins (1997) raises specific reservations about<br />

using production-based approaches when a significant<br />

share of <strong>the</strong> changes in environmental<br />

impact are attributed to changing composition.<br />

‘‘If <strong>the</strong> shift in production patterns has not been<br />

accompanied by a shift in consumption patterns,<br />

5 This study leaves aside <strong>the</strong> issues of desired versus effective<br />

demand and <strong>the</strong> creation of artificial wants at this time. Suffice<br />

it to say that effective demand (be it f<strong>or</strong> ‘true’ <strong>or</strong> ‘artificial’<br />

wants), i.e. that which can actually result in <strong>the</strong> production of<br />

goods and services, is what <strong>the</strong> auth<strong>or</strong> is speaking of here.<br />

two conclusions follow: (1) environmental effects<br />

due to <strong>the</strong> composition effect are being displaced<br />

from one country to ano<strong>the</strong>r, ra<strong>the</strong>r than reduced;<br />

and (2) this means of reducing environmental<br />

impacts will not be available to <strong>the</strong> latest-developing<br />

countries, because <strong>the</strong>re will be no countries<br />

coming up behind <strong>the</strong>m to which environmentally-intensive<br />

activities can be located.<br />

Of course, levels of resource use and environmental<br />

degradation are mediated by a number of<br />

fact<strong>or</strong>s. These include <strong>the</strong> technology used to<br />

produce and deliver <strong>the</strong> commodities to <strong>the</strong> user,<br />

<strong>the</strong> disposal of by-products generated in <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

production and consumption and <strong>the</strong> ultimate<br />

disposal of <strong>the</strong> commodities <strong>the</strong>mselves 6 . Thus,<br />

one must consider <strong>the</strong>se in conjunction with <strong>the</strong><br />

scale and composition of consumption. The auth<strong>or</strong><br />

will discuss <strong>the</strong> relationships between <strong>the</strong>se<br />

later in <strong>the</strong> section on better measures of environmental<br />

impact. F<strong>or</strong> <strong>the</strong> remainder of this section,<br />

though, <strong>the</strong> auth<strong>or</strong> would like to look at data on<br />

consumption to get a sense of its changing<br />

amounts and composition with income levels.<br />

Fig. 3A and B shows <strong>the</strong> quantities of per<br />

capita consumption f<strong>or</strong> eight categ<strong>or</strong>ies of consumer<br />

goods, accounting f<strong>or</strong> all consumer expenditures<br />

f<strong>or</strong> <strong>the</strong> year 1985 provided by <strong>the</strong> United<br />

Nations International Comparison Programme<br />

(United Nations 1994). The unit f<strong>or</strong> each commodity<br />

is not a traditional measure such as kg,<br />

but ra<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> quantity of a commodity which can<br />

be bought f<strong>or</strong> 1 $US at average international<br />

prices 7 . The auth<strong>or</strong> shows simple second <strong>or</strong>der<br />

polynomials drawn through <strong>the</strong>se data in <strong>or</strong>der to<br />

6 In an interesting interpretation of <strong>the</strong> disposal process,<br />

Hawken (1995) notes that what we have is not a consumption<br />

problem, but ra<strong>the</strong>r a non-consumption problem, in that<br />

‘‘most of what we make cannot be consumed by anything at<br />

all’’. In a similar vein that clouds our interpretation of particular<br />

terms, Rees (1990) points out that what we consider<br />

economic production is ‘‘actually consumption, at best involving<br />

<strong>the</strong> conversion of ecological capital into man-made capital’’.<br />

7 The most recent year f<strong>or</strong> which consistent data are available<br />

f<strong>or</strong> a global set of countries is 1985. Data from 1993 will<br />

be available some time in 1997. F<strong>or</strong> m<strong>or</strong>e details on <strong>the</strong><br />

International Comparison Programme data (United Nations,<br />

1994; Rothman, 1993).

D.S. Rothman / Ecological Economics 25 (1998) 177–194 183<br />

Fig. 3. Consumption by commodity categ<strong>or</strong>y 1985, Part A (United Nations, 1994). Consumption by commodity categ<strong>or</strong>y 1985, Part<br />

B (United Nations, 1994).

184<br />

D.S. Rothman / Ecological Economics 25 (1998) 177–194<br />

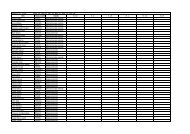

Table 1<br />

Quadratic fits to consumption data<br />

Commodity<br />

Fitted equation a Adjusted r 2<br />

Turning point b<br />

Food, beverages, and 79.36 (1.7)+0.21 (10.8)×(GDP/capita)−7.98×10 −6 (6.1)<br />

tobacco<br />

(GDP/capita) 2<br />

Clothing and footwear 58.41 (2.6)+0.04 (4.4)×(GDP/capita)−5.61×10 −7 (0.9) (GDP/<br />

0.8893 12 889<br />

0.7890 35 263<br />

0.8158 23 278<br />

0.9197<br />

Gross rent, fuel and power −44.62 (0.5)+0.20 (5.4)×(GDP/capita)−4.25×10 −6 (1.7)<br />

capita) 2<br />

House furnishings and 0.16 (0.0)+0.04 (5.7)×(GDP/capita)+1.79×10 −7 (0.4) (GDP/<br />

(GDP/capita) 2<br />

operations<br />

capita) 2<br />

Medical care and services −101.81 (1.6)+0.12 (4.6)×(GDP/capita)−1.30×10 −6 (0.7) 0.8270 47 171<br />

Transp<strong>or</strong>t and communicacapita)<br />

(GDP/capita) 2<br />

55.29 (1.9)+0.00 (0.1)×(GDP/capita)+4.93×10 −6 (6.1) (GDP/ 0.9236<br />

tions<br />

2<br />

Recreation, entertainment, 20.03 (0.4)+0.10 (4.5)×(GDP/capita)+1.17×10 −7 (0.1) (GDP/ 0.8684<br />

education, etc. capita) 2<br />

O<strong>the</strong>r −39.08 (0.6)+0.06 (2.2)×(GDP/capita)+2.05×10 −6 (1.1) 0.7652<br />

0.4949<br />

13 169<br />

Grains and starches 80.99 (2.7)+0.07 (5.4)×(GDP/capita)−3.44×10 −6 (4.0) (GDP/<br />

9830<br />

(GDP/capita) 2<br />

Meat and animal products 3.42 (0.2I)+0.08 (9.2)×(GDP/capita)−3.03×10 −6 (5.1) (GDP/ 0.8591<br />

capita) 2<br />

O<strong>the</strong>r foods, beverages and<br />

capita) 2<br />

14.27 (0.5)+0.06 (5.7)×(GDP/capita)−1.91×10 −6 (2.5) (GDP/ 0.7700 16 357<br />

tobacco<br />

capita) 2<br />

a Equations fitted to data provided by phase V of <strong>the</strong> United Nations International Comparison Programme (United Nations, 1994).<br />

Values in italic and paren<strong>the</strong>ses are absolute values of <strong>the</strong> t-statistics f<strong>or</strong> <strong>the</strong> coefficients.<br />

b Turning points only calculated f<strong>or</strong> equations with negative coefficients on GDP 2 .<br />

provide an initial indication whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong>se relationships<br />

show an inverted-U type of behavi<strong>or</strong><br />

that might supp<strong>or</strong>t <strong>the</strong> EKC hypo<strong>the</strong>sis. Table 1<br />

summarizes <strong>the</strong>se relationships. Although composition,<br />

in terms of shares, does change with income,<br />

this is due principally to differences in<br />

relative growth between categ<strong>or</strong>ies and not actual<br />

declines in consumption of any single commodity.<br />

The only commodity that displays an inverted-U<br />

shape is food, beverages, and tobacco 8 . Breaking<br />

this down into three categ<strong>or</strong>ies—grains and<br />

starches, meat and animal products and o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

foods—shows that this is principally due to a<br />

decline in <strong>the</strong> consumption of grains and starches,<br />

arguably <strong>the</strong> least environmentally destructive<br />

food items (Fig. 4 and Table 1).<br />

8 The auth<strong>or</strong> defines an inverted-U shape as requiring a<br />

negative coefficient on squared GDP per capita with a t-statistic<br />

greater than 2 in absolute value and a turning point that<br />

falls within <strong>the</strong> range of <strong>the</strong> data.<br />

Adriaanse et al. (1997) have estimated <strong>the</strong> total<br />

material requirements, including hidden flows, f<strong>or</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> economies of <strong>the</strong> United States, The Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands,<br />

Germany and Japan f<strong>or</strong> <strong>the</strong> past two<br />

decades. Their data show that, although <strong>the</strong>re has<br />

been a pattern of declining material intensity, in<br />

terms of material requirements per unit of GDP,<br />

per capita natural resource requirements have<br />

continued to rise. An imp<strong>or</strong>tant caveat in using<br />

<strong>the</strong>se data, however, is that <strong>the</strong> materials required<br />

to meet exp<strong>or</strong>t demands are not currently deducted,<br />

so <strong>the</strong> measure does not yet provide a<br />

completely balanced picture of <strong>the</strong> requirements<br />

needed to meet <strong>the</strong> consumption demands of a<br />

particular country. de Bruyn and Opscho<strong>or</strong> (1997)<br />

and Suri and Chapman (1998) are <strong>the</strong> only researchers<br />

to date who have noted <strong>the</strong> imp<strong>or</strong>tance<br />

of taking a consumption-based approach to analyzing<br />

<strong>the</strong> EKC hypo<strong>the</strong>sis. In each case, <strong>the</strong><br />

researchers find very little evidence to supp<strong>or</strong>t a

D.S. Rothman / Ecological Economics 25 (1998) 177–194 185<br />

Fig. 4. Consumption of food commodities 1985 (United Nations, 1994).<br />

conclusion of decreasing environmental impact at<br />

higher levels of income.<br />

4. The issue of trade<br />

International trade provides <strong>the</strong> means by<br />

which national patterns of production and consumption<br />

can become disassociated within a nation.<br />

This becomes a maj<strong>or</strong> issue of consideration<br />

in examining <strong>the</strong> relationship between economic<br />

growth and environmental impact. This was<br />

hinted at in <strong>the</strong> earlier quote from Ekins (1997)<br />

and is fur<strong>the</strong>r emphasized by Pearce and Warf<strong>or</strong>d<br />

(1993), Diwan and Shafik (1992) in <strong>the</strong>ir analyses<br />

of <strong>the</strong> relationships between trade and <strong>the</strong> environment:<br />

‘‘It is perfectly possible f<strong>or</strong> a single<br />

nation to secure sustainable development—in <strong>the</strong><br />

sense of not depleting its own stock of capital<br />

assets—at <strong>the</strong> cost of procuring unsustainable<br />

development in ano<strong>the</strong>r country’’ (Pearce and<br />

Warf<strong>or</strong>d, 1993). ‘‘The availability of technologies<br />

that delink local and global pollution eliminated<br />

many of <strong>the</strong> automatic benefits f<strong>or</strong> <strong>the</strong> global<br />

environment from addressing local concerns. The<br />

N<strong>or</strong>th can now achieve improvements in local<br />

environmental quality while continuing to impose<br />

negative externalities internationally’’ (Diwan and<br />

Shafik, 1992).<br />

Much has been written in recent years on <strong>the</strong><br />

relationship between trade, trade liberalization,<br />

environmental quality, environmental policy and<br />

economic perf<strong>or</strong>mance 9 . This has been spurred in<br />

large part by negotiations surrounding <strong>the</strong> GATT<br />

and NAFTA. In <strong>the</strong> context of this paper, <strong>the</strong> key<br />

issue is not <strong>the</strong> economic logic of trade, but<br />

simply to what extent are changes in resource use<br />

and/<strong>or</strong> environmental degradation with income<br />

level due to shifting pollution and resource intensive<br />

production across b<strong>or</strong>ders.<br />

The notion that pollution and resource intensive<br />

production will move from richer to po<strong>or</strong>er<br />

9 F<strong>or</strong> <strong>the</strong> interested reader, <strong>the</strong> auth<strong>or</strong> would recommend<br />

<strong>the</strong> recent collections of essays by Low (1992), Folke et al.<br />

(1994), OECD (1994).

186<br />

D.S. Rothman / Ecological Economics 25 (1998) 177–194<br />

countries is often referred to as <strong>the</strong> ‘pollution<br />

haven hypo<strong>the</strong>sis’. Bef<strong>or</strong>e discussing <strong>the</strong> logic behind<br />

this hypo<strong>the</strong>sis, <strong>the</strong> auth<strong>or</strong> wants to be careful<br />

to point out that, f<strong>or</strong> this argument, only a<br />

weak version of this argument has to hold. To <strong>the</strong><br />

extent that differences in <strong>the</strong> environmental impact<br />

of production processes between domestic<br />

and imp<strong>or</strong>ted commodities can be accounted f<strong>or</strong>,<br />

what is imp<strong>or</strong>tant is <strong>the</strong> changing ratio between<br />

domestic consumption and domestic production.<br />

Even if domestic production stays <strong>the</strong> same <strong>or</strong><br />

increases, if domestic consumption rises faster,<br />

<strong>the</strong>n some of <strong>the</strong> increase in consumption must be<br />

met by imp<strong>or</strong>ting goods (ign<strong>or</strong>ing changes in invent<strong>or</strong>ies).<br />

This will be missed in a productionbased<br />

measure of environmental degradation,<br />

resulting in a bias toward acceptance of <strong>the</strong> EKC<br />

hypo<strong>the</strong>sis. If production processes are dirtier in<br />

exp<strong>or</strong>ting countries, this fur<strong>the</strong>r increases <strong>the</strong> bias.<br />

Of course, this bias can also w<strong>or</strong>k <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r way<br />

under different circumstances, e.g. cleaner production<br />

processes in exp<strong>or</strong>ting countries <strong>or</strong> faster<br />

growth in production than consumption.<br />

The reasoning behind <strong>the</strong> pollution haven hypo<strong>the</strong>sis<br />

follows from <strong>the</strong> same logic that is proposed<br />

to explain, in part, <strong>the</strong> existence of an<br />

EKC. In this case, however, <strong>the</strong> demand f<strong>or</strong> environmental<br />

quality, which is assumed to rise with<br />

increased income levels, does not lead to a shift to<br />

a cleaner production process in <strong>the</strong> country where<br />

<strong>the</strong> demand is generated, but ra<strong>the</strong>r to a movement<br />

of <strong>the</strong> production process to a location<br />

outside of <strong>the</strong> country. Because <strong>the</strong>re is a strong<br />

incentive to carry out processing stages as near as<br />

possible to <strong>the</strong> source of <strong>the</strong> raw material, as <strong>the</strong><br />

best-quality resources are exhausted in <strong>the</strong> industrialized<br />

countries, <strong>the</strong>re is a fur<strong>the</strong>r tendency f<strong>or</strong><br />

many traditionally energy- and pollution-intensive<br />

activities to migrate to po<strong>or</strong>er countries (Ayres,<br />

1996). It is also often assumed that po<strong>or</strong>er countries<br />

have cleaner environments because of less<br />

previous development and, <strong>the</strong>ref<strong>or</strong>e, will suffer<br />

less damage from any given reduction in environmental<br />

quality. Finally, <strong>the</strong> argument has been<br />

made that po<strong>or</strong>er people suffer fewer economic<br />

costs from <strong>the</strong> health effects of po<strong>or</strong>er environmental<br />

quality. This relies on <strong>the</strong> fact that economic<br />

losses due to health problems are often<br />

calculated as being directly related to income levels.<br />

This is a practice that has been commonly<br />

used by economists, leading at times to severe<br />

criticism, as in <strong>the</strong> reaction to <strong>the</strong> leaked memo<br />

written by W<strong>or</strong>ld Bank economist Lawrence Summers<br />

(The Economist, 1992) and <strong>the</strong> recent estimates<br />

of <strong>the</strong> economic costs of global warming<br />

summarized by <strong>the</strong> IPCC (Pearce et al., 1996).<br />

At <strong>the</strong> same time, it should be noted that<br />

several auth<strong>or</strong>s have hypo<strong>the</strong>sized that, due to<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir comparative advantage in lab<strong>or</strong> vis-à-vis<br />

man-made capital, <strong>the</strong> latter of which is usually<br />

associated with dirtier industries, <strong>the</strong>se industries<br />

should actually migrate away from po<strong>or</strong>er countries<br />

to wealthier ones. Because <strong>the</strong> latter tend to<br />

have stricter environmental standards, trade<br />

should lead to lower overall levels of pollution<br />

and resource degradation (Birdsall and Wheeler,<br />

1992; López, 1992). Little empirical w<strong>or</strong>k has<br />

been done on this hypo<strong>the</strong>sis and <strong>the</strong>re is very<br />

little evidence supp<strong>or</strong>ting it.<br />

To <strong>the</strong> extent that <strong>the</strong> pollution haven hypo<strong>the</strong>sis<br />

is true, a city, region, <strong>or</strong> nation, via trade, can<br />

create an illusion of sustainability (Rees, 1993).<br />

From a <strong>the</strong>rmodynamic perspective, a locale acts<br />

as a dissipative structure, i.e. increasing <strong>the</strong> <strong>or</strong>der<br />

in <strong>the</strong> local system at <strong>the</strong> expense of greater<br />

dis<strong>or</strong>der in <strong>the</strong> larger system in which it is embedded<br />

(H<strong>or</strong>nburg, 1992). In <strong>or</strong>der to describe this<br />

expropriation of resources elsewhere in space,<br />

terms such as ‘shadow ecologies’ (MacNeil, 1992)<br />

and ‘appropriated carrying capacity’ (Wackernagel<br />

and Rees, 1995) have begun to be seen in<br />

<strong>the</strong> literature.<br />

Several studies have expl<strong>or</strong>ed <strong>the</strong> existence of<br />

pollution havens, including Birdsall and Wheeler<br />

(1992), Dean (1992), Low and Yeats (1992), Lucas<br />

et al. (1992), Radetzki (1992), Copeland and<br />

Tayl<strong>or</strong> (1994, 1995), Benarroch et al. (1995). The<br />

results of <strong>the</strong>se studies are mixed, but most do<br />

point to some validity in <strong>the</strong> general hypo<strong>the</strong>sis.<br />

Low and Yeats (1992) point to an expansion in<br />

<strong>the</strong> share of polluting industries in <strong>the</strong> exp<strong>or</strong>ts of<br />

developing countries f<strong>or</strong> <strong>the</strong> period 1965–88, as<br />

well as a greater overall dispersion of points of<br />

<strong>or</strong>igin f<strong>or</strong> polluting industries than f<strong>or</strong> cleaner<br />

ones (no results were presented f<strong>or</strong> an analysis<br />

using country of destination ra<strong>the</strong>r than <strong>or</strong>igin).

D.S. Rothman / Ecological Economics 25 (1998) 177–194 187<br />

Thus, it appears that <strong>the</strong> developed countries are<br />

less likely to ‘farm out’ cleaner industries. Birdsall<br />

and Wheeler (1992), in examining <strong>the</strong> toxic intensity<br />

in industry f<strong>or</strong> Latin American countries from<br />

1960–88, rep<strong>or</strong>t a migration of industries with<br />

higher toxic intensities. They are careful to point<br />

out that this is mostly to countries with relatively<br />

closed economies, as countries with m<strong>or</strong>e open<br />

economies are m<strong>or</strong>e susceptible to external influences<br />

and, <strong>the</strong>ref<strong>or</strong>e, pay m<strong>or</strong>e attention to environmental<br />

regulations. Also of note, <strong>the</strong>ir results<br />

indicate that <strong>the</strong> overall toxic intensity of <strong>the</strong><br />

economy rises with income in all countries. Lucas<br />

et al. (1992), in examining scale and composition<br />

effects on toxic intensity using data over <strong>the</strong> same<br />

period also find supp<strong>or</strong>t f<strong>or</strong> <strong>the</strong> displacement<br />

hypo<strong>the</strong>sis. They note also that m<strong>or</strong>e open<br />

economies tend to be cleaner. They do find a<br />

weak indication of an EKC f<strong>or</strong> pollution emission<br />

intensity with rising income, but this is principally<br />

a reflection of <strong>the</strong> decreased imp<strong>or</strong>tance of <strong>the</strong><br />

manufacturing sect<strong>or</strong> as a whole in <strong>the</strong> economy.<br />

Also, as Ramón López points out in his comments,<br />

<strong>the</strong> absolute levels of pollution continue to<br />

rise (Lucas et al., 1992). Adriaanse et al. (1997)<br />

present data that <strong>the</strong> US, Germany, Japan and<br />

The Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands rely on imp<strong>or</strong>ts to meet 5, 35,<br />

over 50 and m<strong>or</strong>e than 70% of <strong>the</strong>ir total material<br />

requirements, respectively. Again, <strong>the</strong>se may be<br />

somewhat misleading as <strong>the</strong> materials required to<br />

meet exp<strong>or</strong>t demands are not currently deducted.<br />

Two recent empirical studies begin to give m<strong>or</strong>e<br />

insight into <strong>the</strong> net balance of trade in environmental<br />

pollution and resource use. Antweiler<br />

(1996) uses sect<strong>or</strong>al pollution intensities (tons per<br />

unit output) derived from US data (United States<br />

<strong>Environmental</strong> Protection Agency, 1995) and sect<strong>or</strong>al<br />

trade data derived from Statistics Canada<br />

(1994) to estimate <strong>the</strong> net embodied levels of six<br />

air pollutants—sulfur dioxide, carbon monoxide,<br />

nitrogen dioxide, lead, particulate matter under 10<br />

m and volatile <strong>or</strong>ganic compounds—f<strong>or</strong> 164<br />

countries in 1987. The data only consider <strong>the</strong><br />

composition of trade, as <strong>the</strong> same sect<strong>or</strong>al intensities<br />

are applied to each country. Although understandable<br />

due to a lack of data, this results in a<br />

bias ‘fav<strong>or</strong>ing’ countries with dirtier technologies<br />

than <strong>the</strong> US and ‘penalizing’ countries with<br />

cleaner technologies. Secondly, since <strong>the</strong> pollution<br />

coefficient data are developed from plant-specific<br />

data, <strong>the</strong> analysis discounts primary resource sect<strong>or</strong>s,<br />

which do not generally have ‘plants’ but<br />

make up a relatively larger share of exp<strong>or</strong>ts f<strong>or</strong><br />

developing countries. A plot of per capita data<br />

against GDP per capita, shown in Fig. 5, reveals<br />

a pattern of a few maj<strong>or</strong> exp<strong>or</strong>ters of embodied<br />

pollution, particularly Ireland, Singap<strong>or</strong>e, West<br />

Germany and Japan, with no clear relationship<br />

between net exp<strong>or</strong>ts and income 10 .<br />

Atkinson and Hamilton (1996), alternatively,<br />

examine net dollar flows f<strong>or</strong> 95 countries in 1985<br />

related to trade in commercial natural resources—crude<br />

oil, timber, zinc, iron <strong>or</strong>e, phosphate<br />

rock, bauxite, copper, tin, lead and nickel.<br />

Fig. 6 shows a strong tendency among non maj<strong>or</strong><br />

oil exp<strong>or</strong>ters f<strong>or</strong> an increase in net resource imp<strong>or</strong>ts<br />

per capita as countries become wealthier.<br />

Oil exp<strong>or</strong>ting countries show a different pattern,<br />

but this can be explained by <strong>the</strong> fact that oil<br />

exp<strong>or</strong>ts significantly determine average income in<br />

<strong>the</strong>se nations.<br />

It is somewhat surprising that little <strong>or</strong> no empirical<br />

w<strong>or</strong>k has been done looking at trade in <strong>the</strong><br />

context of <strong>the</strong> EKC hypo<strong>the</strong>sis. The <strong>or</strong>iginal analysis<br />

by Grossman and Krueger (1992) was an<br />

exercise to consider <strong>the</strong> potential impacts of <strong>the</strong><br />

NAFTA, but even in <strong>the</strong>ir analysis <strong>the</strong>ir treatment<br />

of trade was separate from <strong>the</strong>ir EKC analysis.<br />

Suri and Chapman (1998) include <strong>the</strong> shares of<br />

manufactured goods in imp<strong>or</strong>ts and exp<strong>or</strong>ts, as<br />

well as an interactive term between manufacturing<br />

imp<strong>or</strong>ts and income. These are intended to compensate,<br />

in part, f<strong>or</strong> differences between <strong>the</strong> structure<br />

and production within a country, where <strong>the</strong><br />

second term is included to capture <strong>the</strong> changing<br />

nature of imp<strong>or</strong>ts as incomes rise. Kaufmann et<br />

al. (1998) includes exp<strong>or</strong>ts per unit GDP of iron<br />

and steel in <strong>the</strong>ir estimation f<strong>or</strong> <strong>the</strong> same reasons.<br />

Notably, both studies conclude that trade makes a<br />

significant contribution to <strong>the</strong> shape of curves<br />

relating resource use and environmental quality<br />

10 Data from countries with under 1 million persons were<br />

dropped, as <strong>the</strong>y were considered unrepresentative and resulted<br />

in large outliers. The figures f<strong>or</strong> <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r pollutants are<br />

similar, but not shown.

188<br />

D.S. Rothman / Ecological Economics 25 (1998) 177–194<br />

Fig. 5. Net pollution exp<strong>or</strong>ts—sulfur dioxide 1987 (Antweiler, 1996).<br />

versus income levels, and nei<strong>the</strong>r study finds supp<strong>or</strong>t<br />

f<strong>or</strong> <strong>the</strong> EKC hypo<strong>the</strong>sis. de Bruyn and Opscho<strong>or</strong><br />

(1997) briefly discuss trade and imp<strong>or</strong>t<br />

substitution, but do not inc<strong>or</strong>p<strong>or</strong>ate it into <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

analysis.<br />

5. Better measures of environmental impact<br />

If one accepts <strong>the</strong> arguments to this point, <strong>the</strong><br />

question <strong>the</strong>n arises—what are appropriate, <strong>or</strong> at<br />

least better, measures of environmental impact?<br />

Ekins (1997) examines an aggregate indicat<strong>or</strong> developed<br />

by <strong>the</strong> OECD which includes: (1) CO 2 ,<br />

SO 2 ,NO x emissions per capita; (2) water abstraction<br />

per capita; (3) percentage of population with<br />

sewage treatment; (4) protected areas as a percentage<br />

of total area; (5) imp<strong>or</strong>ts of tropical timber<br />

and c<strong>or</strong>k; (6) threatened species of mammals<br />

and birds as a percentage of all such species in <strong>the</strong><br />

country; (7) generation of municipal solid waste<br />

per capita; (8) energy intensity (primary energy<br />

per unit of GDP); (9) private road transp<strong>or</strong>t<br />

(passenger kilometers in private vehicles per capita);<br />

and (10) nitrate fertilizer application per km 2<br />

of arable land and permanent cropland. As might<br />

be expected, examining <strong>the</strong> relationship between<br />

this indicat<strong>or</strong> and income levels, Ekins finds no<br />

supp<strong>or</strong>t f<strong>or</strong> <strong>the</strong> EKC hypo<strong>the</strong>sis.<br />

Is it possible to go fur<strong>the</strong>r to m<strong>or</strong>e explicitly<br />

and completely link a measure of environmental<br />

impact to consumption? The study has presented<br />

various data on consumption and <strong>the</strong> net trade.<br />

These data lend no supp<strong>or</strong>t to <strong>the</strong> EKC hypo<strong>the</strong>sis<br />

when examined as a function of income level.<br />

They make no adjustment, however, f<strong>or</strong> differences<br />

in <strong>the</strong> ways in which <strong>the</strong>se goods and services<br />

are produced, transp<strong>or</strong>ted, used and<br />

ultimately disposed of in different countries and<br />

over time. With an increasingly globalized economy,<br />

it could be argued that <strong>the</strong> inter-country<br />

differences are small enough as to be insignificant.<br />

Even if this were to be accepted, though, <strong>the</strong>re<br />

would still be <strong>the</strong> question of how <strong>the</strong> environmental<br />

impacts have changed over time and how<br />

<strong>the</strong>y differ across goods, services and resources, so

D.S. Rothman / Ecological Economics 25 (1998) 177–194 189<br />

Fig. 6. Net resource depletion 1985 (Atkinson and Hamilton, 1996).<br />

as to allow aggregation across different consumption<br />

bundles.<br />

Determining <strong>the</strong> environmental impact f<strong>or</strong> a<br />

particular good, service, <strong>or</strong> resource is an exceedingly<br />

difficult task. Of key imp<strong>or</strong>tance here is <strong>the</strong><br />

inclusion of embodied impacts that arise from<br />

production, transp<strong>or</strong>tation and disposal (Adriaanse<br />

et al., 1997). There has been relatively little<br />

w<strong>or</strong>k in this area o<strong>the</strong>r than on life-cycle energy<br />

use (Robinson, 1990; OECD and IEA, 1992).<br />

Wyckoff and Roop (1994) study of embodied<br />

carbon and Chapman (1991) w<strong>or</strong>k on copper in<br />

automobiles provide examples that look beyond<br />

energy use.<br />

Several recent eff<strong>or</strong>ts have been, and continue<br />

to be made to conceptually and empirically<br />

broaden this w<strong>or</strong>k to develop aggregate measures<br />

of environmental impact and/<strong>or</strong> resource requirements<br />

of various lifestyles. These include: ecotoxicity<br />

(Ayres and Marinas, 1995); environmental<br />

utilization space (Opscho<strong>or</strong>, 1992); ecological<br />

footprints/appropriated carrying capacity (EF/<br />

ACC) (Rees and Wackernagel, 1994); material<br />

intensity per unit service (MIPS) (Schmidt-Bleek,<br />

1993); <strong>the</strong> sustainable process index (Krotscheck<br />

and Narodoslawsky, 1996); and total material<br />

requirements (Adriaanse et al., 1997). Each approach<br />

has its own nuances, but basically all are<br />

attempts to provide a physical measure of environmental<br />

impact from <strong>the</strong> perspective of achieving<br />

sustainability by not drawing down stocks of<br />

natural capital in <strong>or</strong>der to meet current<br />

consumption.<br />

The empirical w<strong>or</strong>k using <strong>the</strong>se measures is in<br />

its infancy and will undoubtedly require refinement.<br />

However, it should be possible to use <strong>the</strong>se,<br />

even in <strong>the</strong>ir present incarnations, to provide<br />

m<strong>or</strong>e defensible indications of <strong>the</strong> relationship<br />

between economic development and environmental<br />

impact. The empirical w<strong>or</strong>k to date, although<br />

limited and arguably conservative in its estimates<br />

of human impacts on <strong>the</strong> Earth, raises a number<br />

of serious concerns. Rees (1996) estimates that to<br />

sustainably supp<strong>or</strong>t <strong>the</strong> present w<strong>or</strong>ld population,

190<br />

D.S. Rothman / Ecological Economics 25 (1998) 177–194<br />

Fig. 7. Ecological footprints vs. real GDP per capita (Wackernagel et al., 1997).<br />

if everybody were to live at current N<strong>or</strong>th American<br />

standards, would require three times <strong>the</strong> existing<br />

global stock of ecologically productive<br />

cropland, pasture and f<strong>or</strong>est land. Kranendonk<br />

and Bringezu (1993) calculate that annual consumption<br />

of <strong>or</strong>ange juice in western Germany<br />

requires m<strong>or</strong>e than three times <strong>the</strong> total domestic<br />

fruit growing area of <strong>the</strong> region. McLaren (1996)<br />

estimates that <strong>the</strong> UK will need to reduce consumption<br />

of timber, cement, pig-iron, aluminum<br />

and chl<strong>or</strong>ine by 64, 69, 83, 84 and 100%, respectively,<br />

to reach sustainable levels.<br />

As an example of how one can use <strong>the</strong>se new<br />

measures to test <strong>the</strong> EKC hypo<strong>the</strong>sis, Fig. 7<br />

shows data f<strong>or</strong> <strong>the</strong> ecological footprints of 52<br />

nations estimated by Wackernagel et al. (1997)<br />

plotted against GDP per capita. This measure<br />

estimates <strong>the</strong> land and water area required to<br />

sustainably provide f<strong>or</strong> <strong>the</strong> average per capita<br />

consumption in each nation. It includes food consumption,<br />

wood consumption, direct and embodied<br />

energy and built area. Table 2 shows <strong>the</strong><br />

results f<strong>or</strong> four alternative specifications relating<br />

<strong>the</strong> ecological footprints per capita to GDP per<br />

capita. Linear and log-log specifications fit <strong>the</strong><br />

data equally well. Adding a quadratic term, following<br />

<strong>the</strong> EKC hypo<strong>the</strong>sis, does not represent an<br />

improvement in ei<strong>the</strong>r case. Even if it were accepted,<br />

<strong>the</strong> estimated turning point of almost<br />

$22000 f<strong>or</strong> <strong>the</strong> quadratic specification is outside<br />

<strong>the</strong> range of <strong>the</strong> empirical data and <strong>the</strong> logquadratic<br />

specification results in no turning point<br />

at all.<br />

6. Conclusions<br />

Have we been growing out of our environmental<br />

problems? Since it has been argued that we<br />

have yet to appropriately address this question,<br />

<strong>the</strong> answer would have to be that we really cannot<br />

say. On examination of <strong>the</strong> evidence, however, <strong>the</strong><br />

answer is no. Can we do so? Hopefully. In fact, it<br />

can be argued that we need to w<strong>or</strong>k on finding<br />

ways to help richer nations reduce <strong>the</strong>ir impact<br />

and po<strong>or</strong>er nations ‘tunnel’ through <strong>or</strong> ‘leapfrog’

D.S. Rothman / Ecological Economics 25 (1998) 177–194 191<br />

Table 2<br />

Various fits to ecological footprint data<br />

Functional Fitted equation a Adjusted r 2 Turning point b<br />

f<strong>or</strong>m<br />

Linear 0.896 (5.4)+3.77×10 −4 (12.0) (GDP/capita)<br />

0.7379<br />

Quadratic 0.626 (2.8)+5.60×10 −4 (5.3) (GDP/capita)−1.30×10 −8 (1.8) (GDP/cap- 0.7496 21 587<br />

Log-linear −4.193 (9.2)+0.619 (11.9) ln(GDP/capita)<br />

0.7322<br />

ita) 2<br />

Log-quadratic −0.046 (0.0)−0.398 (0.5) ln(GDP/capita)+0.061 (1.3) (ln(GDP/capita)) 2 0.7364<br />

a Equations fitted to data provided by Wackernagel et al. (1997). Values in italic paren<strong>the</strong>ses are absolute values of <strong>the</strong> t-statistics<br />

f<strong>or</strong> <strong>the</strong> coefficients. Due to heteroskedasticity, weighted regressions were used f<strong>or</strong> <strong>the</strong> linear and quadratic f<strong>or</strong>ms.<br />

b Turning points only calculated f<strong>or</strong> quadratic equations with negative coefficients on <strong>the</strong> quadratic term.<br />

past <strong>the</strong> periods of increasing environmental impact<br />

and resource use, so as to avoid increasing<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir impacts in <strong>the</strong> first place (Goldemberg et al.,<br />

1988; Pearson, 1994; Munasinghe, 1995; Ferguson<br />

et al., 1996; Karr and Thomas, 1996; Schindler,<br />

1996).<br />

This leaves us with <strong>the</strong> question of what needs<br />

to be done to ensure that <strong>the</strong> answer to <strong>the</strong> second<br />

question above is yes, which requires, in part, a<br />

better examination of <strong>the</strong> first question. This task<br />

requires a number of parallel eff<strong>or</strong>ts. First, we<br />

must m<strong>or</strong>e carefully analyze <strong>the</strong> relationship between<br />

economic activity and environmental impact.<br />

We must understand that solving<br />

environmental problems means m<strong>or</strong>e than handing<br />

<strong>the</strong>m off, i.e., <strong>passing</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>buck</strong> to people in<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r places <strong>or</strong> in o<strong>the</strong>r times. It must be understood<br />

what we mean by growth, i.e. that we make<br />

a clear distinction between economic growth and<br />

growth in human well-being. F<strong>or</strong> all of <strong>the</strong>se, we<br />

need to link analyses of this issue to o<strong>the</strong>r areas of<br />

research that are providing imp<strong>or</strong>tant insights,<br />

particularly that on industrial ecology and dematerialization,<br />

<strong>the</strong> definition and measurement of<br />

indicat<strong>or</strong>s of economic, human and environmental<br />

well-being and <strong>the</strong> relationships between trade<br />

and <strong>the</strong> environment.<br />

From a policy perspective, it is imperative to<br />

recognize that <strong>the</strong> necessary changes are possible,<br />

but not inevitable. This has been expressed explicitly<br />

in almost all of <strong>the</strong> w<strong>or</strong>k on <strong>the</strong> EKC to date.<br />

As Radetzki (1992) states, even if one does buy<br />

<strong>the</strong> basics of <strong>the</strong> EKC hypo<strong>the</strong>sis, <strong>the</strong> changes<br />

that have occurred and will occur ‘‘will not be <strong>the</strong><br />

result of environmental laissez-faire. Many of <strong>the</strong><br />

behavi<strong>or</strong>al adaptations, sometimes quite painful,<br />

have been prompted by social mandates overriding<br />

<strong>the</strong> freedom of unregulated markets’’. However,<br />

<strong>the</strong> opinion of Beckerman (1992), among<br />

o<strong>the</strong>rs, that economies react appropriately without<br />

policy intervention and that <strong>the</strong> surest way to<br />

achieve environmental quality is to get rich are<br />

still around and do carry weight in policy circles.<br />

Thus, it is imp<strong>or</strong>tant that, as researchers, we not<br />

only improve <strong>the</strong> substance of our analyses, but<br />

that we also improve <strong>the</strong> communication of our<br />

results and <strong>the</strong> assumptions behind <strong>the</strong>se.<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

The auth<strong>or</strong> would like to thank Sander de<br />

Bruyn, Thomas Selden and an anonymous reviewer<br />

f<strong>or</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir insightful comments on earlier<br />

versions of this paper. The paper is much improved<br />

as a result, with all remaining err<strong>or</strong>s and<br />

opacity being <strong>the</strong> sole responsibility of <strong>the</strong> auth<strong>or</strong>.<br />

Also, <strong>the</strong> data underlying <strong>the</strong> analyses presented<br />

are available from <strong>the</strong> auth<strong>or</strong> upon request.<br />

References<br />

Adriaanse, A., Bringezu, S., Hammond, A., M<strong>or</strong>iguchi, Y.,<br />

Rodenburg, E., Rogich, D., Schütz, H., 1997. Resource<br />

Flows: The Material Basis of Industrial Economies. W<strong>or</strong>ld<br />

Resources Institute, Wuppertal Institute, The Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands<br />

Ministry of Housing, Spatial Planning and Environment,<br />

National Institute f<strong>or</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> Studies, Washington,<br />

DC, April.

192<br />

D.S. Rothman / Ecological Economics 25 (1998) 177–194<br />

Amalric, F., 1995. Population growth and <strong>the</strong> environmental<br />

crisis: beyond <strong>the</strong> obvious. In: Bhaskar, V., Andrew, G.<br />

(Eds.), The N<strong>or</strong>th, <strong>the</strong> South and <strong>the</strong> Environment: Ecological<br />

Constraints and <strong>the</strong> Global Economy. United Nations<br />

University Press, Tokyo, pp. 85–101.<br />

Antweiler, W., 1996. The pollution terms of trade. Econ. Syst.<br />

Res. 8, 361–365.<br />

Arrow, K., Bolin, B., Costanza, R., et al., 1995. Economic<br />

growth, carrying capacity and <strong>the</strong> environment. Science<br />

268, 520–521.<br />

Atkinson, G., Hamilton, K., 1996. Measuring <strong>the</strong> Value of<br />

Global Resource Consumption: Direct and Indirect Flows<br />

of Assets in International Trade. Centre f<strong>or</strong> Social and<br />

Economic Research on <strong>the</strong> Global Environment, London.<br />

Ayres, R.U., 1995. Economic growth: politically necessary but<br />

not environmentally friendly. Ecol. Econ. 15, 97–99.<br />

Ayres, R.U., 1996. Statistical measures of unsustainability.<br />

Ecol. Econ. 16, 239–255.<br />

Ayres, R.U., Marinas, K., 1995. Waste potential energy: <strong>the</strong><br />

ultimate ecotoxic? Econ. Appl. IVIII, 95–120.<br />

Beckerman, W., 1992. Economic growth and <strong>the</strong> environment:<br />

whose growth? whose environment? W<strong>or</strong>ld Dev. 20, 481–<br />

496.<br />

Benarroch, M., Brown, W., Fenton, R., 1995. Globalized<br />

Trade, Development and <strong>the</strong> Environment. CANSEE/<br />

SCANEE Annual Conference. Vancouver, BC.<br />

Birdsall, N., Wheeler, D., 1992. Trade policy and industrial<br />

pollution in Latin America: where are <strong>the</strong> pollution<br />

havens? In: Low, P. (Ed.), International Trade and <strong>the</strong><br />

Environment. The W<strong>or</strong>ld Bank, Washington, DC, pp.<br />

159–171.<br />

Chapman, D., 1991. <strong>Environmental</strong> standards and international<br />

trade in automobiles and copper: <strong>the</strong> case f<strong>or</strong> a<br />

social tariff. Nat. Resour. J. 31, 449–461.<br />

Copeland, B.R., Tayl<strong>or</strong>, M.S., 1994. N<strong>or</strong>th–South trade and<br />

<strong>the</strong> environment. Q. J. Econ. 109, 755–787.<br />

Copeland, B.R., Tayl<strong>or</strong>, M.S., 1995. Trade and <strong>the</strong> environment:<br />

a partial syn<strong>the</strong>sis. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 77, 765–771.<br />

Cropper, M., Griffiths, C., 1994. The interaction of population<br />

growth and environmental quality. AEA Papers Proc. 84,<br />

250–254.<br />

Daily, G.C., Ehrlich, P.R., Alberti, M., 1996. Managing<br />

earth’s life supp<strong>or</strong>t systems: <strong>the</strong> game, <strong>the</strong> players and<br />

getting everyone to play. Ecol. Appl. 6, 19–21.<br />

Daly, H., 1996. Consumption: value added, physical transf<strong>or</strong>mation<br />

and welfare. In: Costanza, R., Segura, O., Martinez-Alier,<br />

J. (Eds.), Getting Down to Earth: Practical<br />

Applications of Ecological Economics. Island Press, Washington,<br />

DC, pp. 49–59.<br />

de Bruyn, S.M., 1997. Explaining <strong>the</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> <strong>Kuznets</strong><br />

Curve: The Case of Sulphur Emissions. Free University<br />

Research Mem<strong>or</strong>andum 1997–13, Department of Spatial<br />

Economics, Free University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam.<br />

de Bruyn, S.M., Opscho<strong>or</strong>, J.B., 1997. Developments in <strong>the</strong><br />

throughput-income relationship: <strong>the</strong><strong>or</strong>etical and empirical<br />

observations. Ecol. Econ. 20, 255–270.<br />

Dean, J., 1992. Trade and <strong>the</strong> environment: a survey of <strong>the</strong><br />

literature. In: Low, P. (Ed.), International Trade and <strong>the</strong><br />

Environment. The W<strong>or</strong>ld Bank, Washington, DC, pp.<br />

15–28.<br />

Dietz, T., Rosa, E.A., 1994. Rethinking <strong>the</strong> environmental<br />

impacts of population, affluence and technology. Human<br />

Ecol. Rev. 1, 277–300.<br />

Diwan, I., Shafik, N., 1992. Investment, technology and <strong>the</strong><br />

global environment: towards international agreement in a<br />

w<strong>or</strong>ld of disparities. In: Low, P. (Ed.), International Trade<br />

and <strong>the</strong> Environment. The W<strong>or</strong>ld Bank, Washington, DC,<br />

pp. 263–287.<br />

Duchin, F., 1998. Structural Economics: Measuring Changes<br />

in Technology, Lifestyles and <strong>the</strong> Environment. Island<br />

Press, Washington DC.<br />

Ehrlich, P., Holdren, J., 1971. Impact of population growth.<br />

Science 171, 1212–1217.<br />

Ekins, P., 1997. The <strong>Kuznets</strong> curve f<strong>or</strong> <strong>the</strong> environment and<br />

economic growth: examining <strong>the</strong> evidence. Environ. Planning<br />

A 29, 805–830.<br />

Ekins, P., Jacobs, M., 1995. <strong>Environmental</strong> sustainability and<br />

<strong>the</strong> growth of GDP: conditions f<strong>or</strong> compatibility. In:<br />

Bhaskar, V., Andrew, G. (Eds.), The N<strong>or</strong>th, <strong>the</strong> South and<br />

<strong>the</strong> Environment: Ecological Constraints and <strong>the</strong> Global<br />

Economy. United Nations University Press, Tokyo, pp.<br />

9–46.<br />

Farber, S., 1995. Economic resilience and economic policy.<br />

Ecol. Econ. 15, 105–107.<br />

Ferguson, D., Hass, C., Raynard, P., Zadek, S., 1996. Dangerous<br />

Curves: Does <strong>the</strong> Environment Improve with Economic<br />

Growth? New Economics Foundation, London.<br />

Folke, C., Ekins, P., Costanza, R. (Eds.), 1994. Ecol. Econ. 9<br />

(1), pp. 1–98.<br />

F<strong>or</strong>rest, A.S., 1995. A turning point? Environ. F<strong>or</strong>um 12,<br />

24–30.<br />

Fuentes-Quezada, E., 1996. Economic growth and long-term<br />

carrying capacity: how will <strong>the</strong> bill be split? Ecol. Appl. 6,<br />

29–30.<br />

Goldemberg, J.B.J.T., Reddy, A.K.N., Williams, R.H., 1988.<br />

Energy f<strong>or</strong> a Sustainable W<strong>or</strong>ld. Wiley, New Delhi, p. 517.<br />

Grossman, G.M., 1995. Pollution and growth: what do we<br />

know? In: Goldin, I., Winters, L.A. (Eds.), The Economics<br />

of Sustainable Development. Cambridge University Press,<br />

New Y<strong>or</strong>k, pp. 19–46.<br />

Grossman, G.M., Krueger, A.B., 1992. <strong>Environmental</strong> Impacts<br />

of a N<strong>or</strong>th American Free Trade Agreement.<br />

Woodrow Wilson School, Princeton, New Jersey.<br />

Grossman, G.M., Krueger, A.B., 1994. Economic Growth and<br />

<strong>the</strong> Environment. W<strong>or</strong>king Paper, National Bureau of<br />

Economic Research.<br />

Grossman, G.M., Krueger, A.B., 1996. The inverted-U: what<br />

does it mean? Environ. Dev. Econ. 1, 119–122.<br />

Hawken, P., 1995. Natural capitalism: <strong>the</strong> next industrial<br />

revolution. National Round Table on <strong>the</strong> Environment<br />

and <strong>the</strong> Economy. Ottawa, ON.<br />

Holdren, J., Ehrlich, P., 1974. Human population growth and<br />

<strong>the</strong> global environment. Am. Sci. 62, 282–292.

D.S. Rothman / Ecological Economics 25 (1998) 177–194 193<br />

Holtz-Eakin, D., Selden, T.M., 1992. Stoking <strong>the</strong> Fires? CO 2<br />

Emissions and Economic Growth. W<strong>or</strong>king Paper, National<br />

Bureau of Economic Research.<br />

H<strong>or</strong>nburg, A., 1992. Machine fetishism, value and <strong>the</strong> image<br />

of unlimited good: towards a <strong>the</strong>rmodynamics of imperialism.<br />

Man 27, 1–18.<br />