A Note From the Editor - SEXTONdigital

A Note From the Editor - SEXTONdigital

A Note From the Editor - SEXTONdigital

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Society for <strong>the</strong> Study of<br />

Architecture in Canada<br />

President<br />

MarkFram<br />

159 Russell Hill Road, No. 101<br />

Toronto, Ontario M4V 259<br />

Past President<br />

Douglas Franklin<br />

30 Renfrew Avenue<br />

Ottawa, Ontario KlS 1Z5<br />

Vice-President<br />

Diana Thomas<br />

Historic Sites Selvice<br />

Alberta Culture and Multiculturalism<br />

Old St. Stephen's College, 8820 112 Street<br />

Edmonton, Alberta T6G 2P8<br />

Treasurer<br />

Ann Bowering<br />

Heritage Canada<br />

P.O. Box 1358, Station B<br />

Ottawa, Ontario K1P 5R4<br />

Secretary<br />

Shannon Ricketts<br />

Environment Canada, Parks Service<br />

Ottawa, Ontario K1A OH3<br />

Bulletin <strong>Editor</strong><br />

Gordon Fulton<br />

76 Lewis Street<br />

Ottawa, Ontario K2P OS6<br />

res. ( 416) 961-9956<br />

office (613) 237-1867<br />

res. 236-5395<br />

office ( 403) 431-2343<br />

office (613) 237-1066<br />

office (819) 9534611<br />

office (819) 997-6966<br />

fax: (819) 953-4909<br />

Members-at-large (east to west)<br />

Philip Pratt office (709) 576-8612<br />

7PiankRoad<br />

St. John's, Newfoundland AlE 1H3<br />

Jim St. Oair office (902) 539-5300<br />

University College of Cape Breton, P.O. Box 5300<br />

Sydney, Nova Scotia BlP 612<br />

Dr. C. W. Eliot office (902) 566-0400<br />

University of Prince Edward Island<br />

550 University Avenue<br />

Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island CIA 4P3<br />

Allen Doiron office (506) 453-2122<br />

Provincial Archives<br />

P.O. Box 6000<br />

Fredericton, New Brunswick E3B 5Hl<br />

Donna McGee office (514) 939-7000<br />

13310 Sauriol<br />

Pierrefonds, Quebec H8Z 181<br />

Anne M. de Fort-Menares (416) 769-6862<br />

100 Quebec Avenue, Ste 608<br />

Toronto, Ontario M6P 488<br />

Philip N. Haese (204) 269-7994<br />

785 Pasadena Avenue<br />

Winnipeg, Manitoba R2T 2T6<br />

Terry Sinclair<br />

3111 Retallack Street<br />

Regina, Saskatchewan S4S 1T5<br />

Dorothy Field office (403) 431-2344<br />

Historic Sites Service<br />

Alberta Culture and Multiculturalism<br />

Old St. Stephen's College, 8820 112 Street<br />

Edmonton, Alberta T6G 2P8<br />

Valda Vidners (604) 662-7623<br />

1047 Barclay Avenue, Apt 702<br />

Vancouver, British Columbia V6E4H2<br />

Ann Peters (403) 873-7821<br />

Box2303<br />

Yellowknife, Northwest Territories XlA 2P7<br />

ISSN No. 0228.0744<br />

Produced with <strong>the</strong> assistance or <strong>the</strong> Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council<br />

COVER: The 38th Annual MeetU.g of <strong>the</strong> Albena Associatiot1 of Architects, Calgary,<br />

1948. Mary Imrie and Jean W allbridge are secot1d and third from <strong>the</strong> right, middle row.<br />

( ProvU.cial Archives of Alben a, Neg. No. 88· 290) See pages 12-18,<br />

BULLETIN<br />

Volume/Tome 17, Number/Numero 1<br />

A <strong>Note</strong> from <strong>the</strong> <strong>Editor</strong>/<strong>Note</strong> du redacteur<br />

by Dorothy Field ........................................................................... 3<br />

Slowly and Surely (and Somewhat Painfully): More or Less<br />

<strong>the</strong> History of Women in Architecture in Canada •<br />

by Blanche Lemco van Ginkel .................................................... 5<br />

Wall bridge and Imrie: The Architectural Practice of Two<br />

Edmonton Women, 1950-1979*<br />

by Em a Dominey ........................................................................ 12<br />

Women and <strong>the</strong> Built Environment: A Course for Students<br />

at <strong>the</strong> Technical University of Nova Scotia•<br />

By Maria Somjen ........................................................................ 19<br />

What's New in Print/Quoi de neuf? ........................................ 23<br />

* Proceedings<br />

Membership fees are payable at <strong>the</strong> following rates: Student, SI5.00;<br />

Individual/Family, $30.00; Organization/Corporation/Institution,<br />

$50.00; Patron, $20.00 (plus a donation or not less than SIOO.OO). There<br />

is a surcharge or $5.00 for all foreign memberships. Contributions over<br />

and above membership fees are welcome, and are tax-deductible. Please<br />

make your cheque or money order payable to <strong>the</strong> SSAC and send to Box<br />

2302, Station D, Ottawa, Ontario KIP 5W5.<br />

L'abonnement annuel est payable aux prix suivantes : etudiant, I5,00 $;<br />

individuel/famille, 30,00 $; organisation/societe/institut, 50,00 S;<br />

bienfaiteur, 20,00 $(plus un don d'au moins IOO,OO $). II y a des frai.s<br />

additionnels de 5,00$ pour les abonnements etrangers. Les contribu·<br />

lions au-dessus de l'abonnement annuel sont acceptees et deductibles<br />

d'imp6l Veuillez s.v.p. Caire le cheque ou mandai poste payable a l'ordre<br />

de SEAC et l'envoyer a Ia Case postale 2302, succursale D, Ottawa<br />

(Ontario) KIP 5W5.<br />

The Society for <strong>the</strong> Study or Architecture in Canada is a learned soci~ty devoted to<br />

<strong>the</strong> examination or <strong>the</strong> role or <strong>the</strong> built environment in Canadian soc1ety. Its member·<br />

ship includes structural and landscape architects, architectural historians, urban his·<br />

torians and planners, sociologists, folklorists, and specialists i~ su~h fields as heritage<br />

conservation and landscape history. Founded in 1974, .<strong>the</strong> ~1ety 1s cu.rrently ~e sole<br />

national society whose focus or interest is Canada's bu11t enVIronment In all or 1ts<br />

manifestations.<br />

2 SSAC BULLETIN SEAC 17:1

A <strong>Note</strong> <strong>From</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Editor</strong><br />

<strong>Note</strong> du redacteur<br />

~he <strong>the</strong>me of <strong>the</strong> 1991 Annual General Meet<br />

.1 ing and Conference of <strong>the</strong> SSAC was "Architecture<br />

on <strong>the</strong> Edge." Appropriately, it took<br />

place in Baddeck, Nova Scotia, near <strong>the</strong> eastern<br />

edge of <strong>the</strong> country. In addition to examining <strong>the</strong><br />

local architecture which lies geographically at edge<br />

<strong>the</strong> of Canada, <strong>the</strong> conference dealt with architecture<br />

which lies historically, structurally, and sociologically<br />

at <strong>the</strong> periphery.<br />

The articles which comprise this issue of<br />

<strong>the</strong> Bulletin are based on papers presented during<br />

<strong>the</strong> session "Women and Architecture." Although<br />

women represent over half <strong>the</strong> nation's population<br />

<strong>the</strong>y have always been marginal participants in <strong>the</strong><br />

field of architecture. This session provided an opportunity<br />

to bring forward a variety of historical and current<br />

topics to examine women's architectural<br />

activities in Canada. A historical scarcity of women<br />

architects in this country might have been viewed as<br />

an indication of a lack of material on which to base a<br />

session, but <strong>the</strong>re was no lack of interest in <strong>the</strong> subject,<br />

and no lack of qualified people wishing to address<br />

<strong>the</strong> topic at <strong>the</strong> conference. The three<br />

speakers selected provided a thought-provoking<br />

review of <strong>the</strong> topic through <strong>the</strong>ir presentations, and<br />

in <strong>the</strong>ir persons as well.<br />

Blanche Lemco van Ginkel is uniquely<br />

qualified to give an overview of <strong>the</strong> history of<br />

women in architectural practice in Canada. Prof.<br />

van Ginkel's long and distinguished career practising<br />

and teaching architecture in Canada, <strong>the</strong> United<br />

States, and Europe enables her to bring her personal<br />

experience and insight to bear on <strong>the</strong> subject.<br />

Erna Dominey, who works with <strong>the</strong> Historic Sites<br />

and Archives Service of Alberta Culture and Multiculturalism,<br />

is pursuing a graduate programme of research,<br />

focusing on a two-woman architectural firm,<br />

Wall bridge and Imrie, active in Edmonton from <strong>the</strong><br />

1950s through <strong>the</strong> 1970s. And Maria Somjen, a<br />

Halifax architect, has been involved in <strong>the</strong> groundbreaking<br />

course on "Women and <strong>the</strong> Built Environment"<br />

at <strong>the</strong> Technical University of Nova Scotia<br />

since its inception in <strong>the</strong> mid-1980s.<br />

Although <strong>the</strong> participation of women in<br />

<strong>the</strong> architectural profession has historically lagged<br />

behind o<strong>the</strong>r fields, recent years have seen a significant<br />

increase in enrolment in architecture<br />

schools and registration by architectural associations<br />

across <strong>the</strong> country. There has been a parallel increase<br />

in <strong>the</strong> attention given to <strong>the</strong> study of women's<br />

roles in <strong>the</strong> production of architecture. This has encompassed<br />

not only women as architects, but<br />

women as patrons or users of architecture. Slowly<br />

L<br />

e th~me de I 'Assembl~e g~n~rale annuelle de<br />

1991 et de Ia conf~rence de Ia SEAC portait<br />

sur "L'architecture ~ un tournant". La conf~rence<br />

s'est tenue ~ Baddeck, en Nouvelle-Ecosse, pr~ de<br />

l'extr~mit~ est du pays; il s'agissait I~ d'un choix<br />

appropri~ pour !'emplacement puisque le titre de Ia<br />

conf~rence sugg~re que !'architecture a atteint un<br />

point limite. En plus d'examiner I' architecture locale<br />

qui est siture ~ une extr~mit~ du Canada, Ia<br />

conf~rence traitait aussi de !'architecture qu'on<br />

retrouve en ¢riph~rie, au point de vue historique,<br />

structure! et sociologique.<br />

Les articles con tenus dans le Bulletin de ce<br />

mois-ci sont tir~ d'expos~s qui ont ~t~ pr~sent~s<br />

Iars de Ia session intitul~e "Femmes et Architecture".<br />

Bien que les femmes repr~sentent plus de Ia<br />

moiti~ de Ia population canadienne, elles ont<br />

toujours jou~ un r61e secondaire dans le domaine de<br />

!'architecture. Cette session a permis de ramener ~<br />

Ia surface une ~rie de th~mes historiques et actuels<br />

permettant d'examiner les activit~s des Canadiennes<br />

en architecture. Le tr~s petit nombre de femmes architectes<br />

dans notre histoire aurait pu etre per

and surely (in <strong>the</strong> words of Blanche van Ginkel),<br />

books, articles, exhibitions, and lectures have been<br />

added to <strong>the</strong> ever-increasing body of knowledge of<br />

women in <strong>the</strong> built environment. The result of <strong>the</strong>se<br />

initiatives, in simplified terms, has been a heightened<br />

awareness of and appreciation for <strong>the</strong> role women<br />

have played - often anonymously- in <strong>the</strong> architectural<br />

history of Canada. This issue of <strong>the</strong> Bulletin<br />

gives a taste of how far women have come in architecture<br />

in Canada. It also suggests how much<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir story needs to be documented and appreciated<br />

-and how determined <strong>the</strong>y are to continue to influence<br />

<strong>the</strong> future course of architecture in Canada.<br />

My thanks to Dominique Michel for translation.<br />

Dorothy Field, Edmonton<br />

Guest <strong>Editor</strong><br />

derni~res ann~es ont connu une hausse notable<br />

d'inscriptions dans des ~coles et des associations<br />

d'architecture A travers le pays. En meme temps, le<br />

nombre d'~tudes portant sur le rl'Jle des femmes<br />

dans Ia production architecturale a lui aussi<br />

augment~. Ces ~tudes ne comprennent pas seulement<br />

les femmes en tant qu'architectes, mais aussi<br />

celles qui parrainent et utilisent !'architecture. Lentement,<br />

mais sOrement (pour reprendre les mots de<br />

Blanche van Ginkel), on a ajout~ des livres, des articles,<br />

des expositions et des conf~rences au corps<br />

grandissant de connaissances sur les femmes et<br />

l'environnement bati. En termes simples, le r~ultat<br />

de ces initiatives se r~ume en une sensibilisation accrue<br />

et une appr~ciation du rl'Jie que les femmes ont<br />

jou~- souvent de fa~n anonyme- dans l'histoire<br />

architecturale du Canada. Le Bulletin de ce mois-ci<br />

donne un aperc;u du chemin qu'ont parcouru les<br />

femmes dans le domaine de !'architecture au<br />

Canada. II rappelle que leur histoire doit etre<br />

document~e et appr~ci~e; il rappelle aussi com bien<br />

les femmes sont d~termin~es A continuer d'intluencer<br />

le cours de !'architecture au Canada.<br />

Merci A Dominique Michel pour Ia traduction.<br />

Dorothy Field, Edmonton<br />

R~dactrice invit~e<br />

4<br />

SSAC BULLETIN SEAC<br />

17:1

Slowly and Surely<br />

(and Somewhat Painfully):<br />

More or Less <strong>the</strong> History of Women<br />

in Architecture in Canada<br />

CANADA'S FIRST WOMAN ARCHITECT .<br />

M iss E . M . Hill , of Toronto. who received <strong>the</strong> D e gr·ee o f B . A .Sc . fro m t hP<br />

Unr v ~rs rty o f Tcu·n..,to. :~t <strong>the</strong> recent spccii11 Conv oci1 t ion.<br />

Figure 1. E. Marjorie Hill, "Canada's First Woman<br />

Architect." (Saturday Night. 12 June 1920, p. 31<br />

[University of Toronto Archives])<br />

By Blanche Lemco van Ginkel<br />

17:1 SSAC BULLETIN SEAC 5

Figure 2. A three bedroom brick house designed by<br />

Marjorie Hill. (VICtoria Daily Colonist, 1952 [Uniwtrsity<br />

of Toronlo Archives])<br />

View and Sunshine in Privacy<br />

tltci::e ~"~ 'J<br />

u~ o · 1 ·~ · J. "<br />

w~•~•~ ; · ~<br />

.<br />

D••••><br />

1 ·o."W• II C.<br />

T X Tomeo entered <strong>the</strong> profession of architecture in Canada very slowly and with great dif<br />

Y Y flculty. A$ a student in architecture at McGill in <strong>the</strong> 1940s, I knew that women had<br />

not been admitted to <strong>the</strong> program until 1939. I attributed this resistance to admitting women<br />

to architecture to <strong>the</strong> social climate of Quebec, where my mo<strong>the</strong>r could not sign a contract,<br />

and where women had been disenfranchised until 1940. These, of course, were much more<br />

fundamental issues. Women of previous generations had distinguished <strong>the</strong>mselves as architects<br />

in England and <strong>the</strong> United States: Sophia Hayden had graduated from <strong>the</strong> Massachussets<br />

Institute of Technology in 1890; E<strong>the</strong>l Charles had been admitted to <strong>the</strong> Royal<br />

Institute of British Architects in 1898, albeit with difficulty; and Julia Morgan had established<br />

a prestigious practice in California in 1920. So I assumed that Quebec was <strong>the</strong> anomaly in<br />

Canada. I discovered, only much later, that although women had received a Canadian degree<br />

in architecture since 1920, <strong>the</strong>y experienced great difficulty in entering <strong>the</strong> profession in<br />

Canada, and <strong>the</strong>ir numbers were negligible (only five women were registered in 1939).<br />

Until <strong>the</strong> late nineteenth century, an architect learned his craft by apprenticeship<br />

and <strong>the</strong>re was no licensing of architects by an authorized body. I can find no record of a<br />

woman working as an architect in Canada in <strong>the</strong> nineteenth century, though undoubtably<br />

<strong>the</strong>re were women designing and supervising <strong>the</strong> construction of buildings on <strong>the</strong>ir own account.<br />

And, of course, pioneering women in Canada, particularly in <strong>the</strong> new West, worked on<br />

<strong>the</strong> construction of <strong>the</strong>ir own homes.<br />

The first formal education in architecture in Canada was offered in 1890 at McGill<br />

University and <strong>the</strong> University of Toronto. In <strong>the</strong> same year, <strong>the</strong> associations of architects in<br />

B<br />

SSAC BULlETIN SEAC 17:1

Figure 3. An apalfment house on Fort Street in Victoria,<br />

designed by Matjorie Hill in 1952. (University of<br />

Toronto Archives)<br />

Ontario and Quebec were <strong>the</strong> first to register architects. It was not until 1916 (by which time<br />

<strong>the</strong>re were five schools/ that a woman was admitted to a programme of architecture. In that<br />

year, Mary Anne Kentner was admitted to <strong>the</strong> programme at <strong>the</strong> University of Toronto and<br />

Marjorie Hill 2 to <strong>the</strong> University of Alberta. The former withdrew after two years for reasons<br />

ofill-health. 3 The latter transferred to <strong>the</strong> University of Toronto in 1918 and received <strong>the</strong> degree<br />

ofB.ASc. in Architecture in 1920 {figure 1).<br />

A cursory examination of Marjorie Hill's career reveals much about <strong>the</strong> position of<br />

women in <strong>the</strong> early twentieth century in Canada. After graduation, Miss Hill worked for <strong>the</strong><br />

Eaton's Department Store in Toronto in <strong>the</strong> interior decorating department. In January 1921<br />

she moved back to Edmonton, where her parents lived, and applied for registration with <strong>the</strong><br />

Alberta Association of Architects. She was denied. It appears that a Mr. Burgess, who had<br />

been her teacher at <strong>the</strong> University of Alberta and who "did not approve of women in architecture,"<br />

was also one of her examiners. 3 She taught at an "ungraded Country School" until <strong>the</strong><br />

spring of 1922, when she gained employment as a draughtsman in <strong>the</strong> office of MacDonald &<br />

Magoon, Architects. The projects on which she worked included <strong>the</strong> Edmonton Public ubrary.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> fall of 1922, Hill decided to extend her knowledge in <strong>the</strong> field, and returned<br />

to <strong>the</strong> University of Toronto for a post-graduate year in town planning. It is evident from<br />

Miss Hill's accounts of her career that she experienced discrimination not only when attempting<br />

to work in her chosen profession, but also in her studies. In 1984 she wrote:<br />

When I went back to University of Toronto in <strong>the</strong> fall of 1922to study town planning I was under a worse cloud, mostly<br />

on account of <strong>the</strong> enormous applause given me when I went to kneel before <strong>the</strong> Chancellor and partly because <strong>the</strong><br />

Albert.1 Architects Association did not want to register me and <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>n Minister of Education in Albert.1, also<br />

University of Toronto alumnus, was so annoyed over it he put through <strong>the</strong> Legislature an amendment to <strong>the</strong> Profes·<br />

sional Architects' Actio <strong>the</strong> effect that "any graduate of any school of architecture in His Majesty's Dominion shall be<br />

admitted." It was a woman who spiked that by adding "arter a year's experience in an architect's office." Naturally, all<br />

this did not go down well with (Chairman of Architecture) C. H. C. Wright 4 who was already prejudiced. He didn't<br />

even come to Convocation 1920 when be bad 4 students graduating in architecture and it was left to Dean Mitchell to<br />

shake my band and congratulate me before 11eft<strong>the</strong> platform! 5<br />

During <strong>the</strong> summer of 1923 Hill attended a course at Columbia University in New<br />

York. She remained in New York, working for architect Marcia Mead until December 1924,<br />

when she returned to Edmonton. She reapplied to <strong>the</strong> Alberta association and was accepted<br />

as a registered architect in 1925. But she must have found <strong>the</strong> social climate for a woman in<br />

architecture less inimical in New York than in Toronto and Edmonton, for in September<br />

1925 she returned to New York to work for architect Kathryn C. Budd.<br />

Miss Hill returned to <strong>the</strong> Edmonton office of MacDonald & Magoon in April 1928<br />

but, as was <strong>the</strong> case throughout North America, <strong>the</strong> Depression severely curtailed architectural<br />

work, and she left <strong>the</strong> office in 1930. Since it was impossible to find work as an architect,<br />

and being a resourceful and independent woman, she applied her design skills to o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

enterprises. She became a prize-winning weaver, taught glove-making, and produced greeting<br />

cards for sale on a hand-press inherited from her fa<strong>the</strong>r.<br />

When her parents retired in 1936, Hill moved with <strong>the</strong>m to Victoria. It was <strong>the</strong>re,<br />

during <strong>the</strong> spate of building which followed <strong>the</strong> Second World War, that her practice finally<br />

flourished. Her work included several houses {figure 2), a motel addition, Fellowship Hall,<br />

apartment buildings (figure 3), and a convalescent hospital for seniors. She was not<br />

1 University of Toronto, McGill University, Ecole<br />

Polytechnique, University of Alberta, and University<br />

of Manitoba.<br />

2 Es<strong>the</strong>r Marjorie Hill was born 29 May 1895 in Guelph,<br />

Ontario, and died 7 January 1985 in Victoria, B.C.<br />

3 E.M. Hill to Anne Ford, 23 March 1984.<br />

4 C.H.C. Wright was <strong>the</strong> first professor of architecture in<br />

<strong>the</strong> School of Practical Science at <strong>the</strong> University of<br />

Toronto, and Chairman of Architecture.<br />

5 E.M. Hill to Blanche L van Ginkel, 3 July 1984.<br />

17:1 SSAC BULLETIN SEAC<br />

7

Figure 4. E. Marjorie Hill (1895-1985), in later life.<br />

registered in British Columbia until 1952; 6 ei<strong>the</strong>r her Alberta registration sufficed, or <strong>the</strong><br />

value of her commissions was not great before that time. She practiced as an architect until<br />

1963, when she was 68 {figure 4), but continued with great energy to weave, make woodcuts,<br />

and produce various design works for sale until shortly before her death at <strong>the</strong> age of 89.<br />

Notwithstanding that Marjorie Hill spent much of <strong>the</strong> early years of her career outside<br />

<strong>the</strong> practice of architecture, she must have remained strongly engaged. Her academic<br />

training was at a time when <strong>the</strong> University of Toronto remained immersed in <strong>the</strong> teachings<br />

derived from <strong>the</strong> Ecole des Beaux-Arts and when practice relied on a pastiche of borrowed<br />

forms and decoration. Never<strong>the</strong>less, contrary to many of her contemporaries who continued<br />

to design in this mode, Hill applied a social sensibility to her work and extolled <strong>the</strong> virtues of<br />

sun, light, air, and space. Her modest apartment buildings are well-proportioned with a<br />

straightforward grace and clarity of detail.<br />

One might have assumed that with Marjorie Hill <strong>the</strong> barricades had been breached,<br />

and that o<strong>the</strong>r women would have followed in swift succession. But by <strong>the</strong> end of <strong>the</strong> 1920s<br />

only two more women had graduated in architecture, both from <strong>the</strong> University of Toronto.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> 1930s <strong>the</strong>re were 16 women graduates, representing 5. 7 percent of <strong>the</strong> total of 282<br />

graduates in architecture from Canadian schools. These numbers should be seen in <strong>the</strong> context<br />

of a sparsely-populated country whose architects had no recognition internationally and<br />

little at home. During <strong>the</strong> era of great railway building and western expansion most major<br />

buildings were designed by architects from Britain or <strong>the</strong> United States, and this tendency<br />

continued, if to a diminishing degree, until <strong>the</strong> 1960s.<br />

Resistance to women entering architecture was both overt and covert. Once admitted<br />

to a school, women were subjected to subtle and not-so-subtle discrimination: <strong>the</strong>re<br />

were unfunny jokes and derogatory remarks in <strong>the</strong> classroom; <strong>the</strong>ir presence was ignored in<br />

<strong>the</strong> studio, where instruction is frequently on an individual basis. Ramsay Traquair, <strong>the</strong> head<br />

of <strong>the</strong> school at McGill, actively opposed admission of women as late as 1930 because of "<strong>the</strong><br />

very insufficient accommodation of our present classes." Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore, in a report to Principal<br />

Sir Arthur Currie, Traquair gave <strong>the</strong> following reasons why it was "impracticable to<br />

admit women":<br />

1. Women are not admitted to tbe Faculty of Applied Science and tbe School of Architecture is an integral part of<br />

tbat Faculty.<br />

2 There are not provisions in tbe Engineering Building for tbe accommodation of women students, and it would be<br />

an expensive matter to provide tbese.<br />

3. At present tbe School of Architecture has a registration of forty, and tbere is no accommodation available for additional<br />

students.<br />

4. Much architectural draughting is done at night, tbe main drawing room being open until ten o'clock. The<br />

responsibility for tbe maintenance of discipline in <strong>the</strong> evening is assumed by tbe students <strong>the</strong>mselves. If women students<br />

were admitted, it would be necessary to provide staff supervision during tbese evening drawing periods and such<br />

supervision would require additional members of staff and put tbe School to extra expense for which it has no funds. 7<br />

6 During an interview by David Hambleton, FRAIC, on<br />

26 May 1984, Hill remarked: "tbe AIBC solicitor was<br />

not at all nice and asked, 'how did you come to be<br />

here?'" She also said tbat Fred Lasserre, director of<br />

tbe School of Architecture at tbe University of British<br />

Columbia, was on tbe e:umination committee. Lasserre<br />

had written to me (about 1950) tbat he was opposed<br />

to women teaching in tbe school.<br />

7 Margaret Gillett, We Walked Very Warily (Montreal:<br />

Eden Press, 1981), 319.<br />

As was noted at <strong>the</strong> time, none of <strong>the</strong>se problems was insurmountable, particularly<br />

(given <strong>the</strong> expertise of <strong>the</strong> Engineering faculty) <strong>the</strong> plumbing shortcomings delicately<br />

referred to in <strong>the</strong> second statement. It is surprising that Professor Traquair did not enunciate<br />

<strong>the</strong> reasons most often cited for <strong>the</strong> exclusion of women: a lack of intellectual capacity and<br />

physical strength. In any event, <strong>the</strong> admission of women was not seriously considered until<br />

1937, when enrolment in <strong>the</strong> McGill school had fallen from 40 to 27 due to <strong>the</strong> Depression.<br />

Women were finally admitted in 1939, <strong>the</strong> first being Ca<strong>the</strong>rine Chard and Arlene Scott.<br />

Given <strong>the</strong> obstacles and general ill-will, it is perhaps to be expected that women<br />

entering a school of architecture in <strong>the</strong>se early years were unusually committed to <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

course of study. At <strong>the</strong> University of Toronto, Beatrice Centner was awarded <strong>the</strong> Toronto Architectural<br />

Guild Medal on graduation in 1930, and Pegeen Synge <strong>the</strong> Royal Architectural Institute<br />

of Canada Medal in 1945. In <strong>the</strong> decade from 1980 to 1989 at <strong>the</strong> University of<br />

Toronto, <strong>the</strong> proportion of major awards earned by women on graduation was marginally<br />

higher than <strong>the</strong>ir 29 percent presence in <strong>the</strong> classes.<br />

Architecture was one of <strong>the</strong> last professional programmes to which women were admitted<br />

in Canadian universities, probably because <strong>the</strong> earliest programmes were in schools of<br />

engineering (though enrolment did not increase substantially when architecture was transferred<br />

from <strong>the</strong> Ecole Polytechnique in Montreal to <strong>the</strong> Ecole des Beaux-Arts in 1923).<br />

Women were accepted in medicine at Queen's University in 1880, and even McGill admitted<br />

women to medicine in 1918, having already admitted women to <strong>the</strong> law faculty in 1911.<br />

But schooling was only one of <strong>the</strong> hurdles on <strong>the</strong> licensing track. Prior to <strong>the</strong><br />

"registration examination," work experience or internship in <strong>the</strong> office of a registered ar-<br />

8<br />

SSAC BULLETlN SEAC 17:1

chitect was required. Apprenticeship without schooling, although lengthy, was and still is a<br />

possible route to licensing as an architect. But finding a position in an architect's office and<br />

gaining <strong>the</strong> required professional experience ei<strong>the</strong>r as an apprentice or intern was at least as<br />

difficult, if not more, as securing a place in a school. Until <strong>the</strong> late 1960s, <strong>the</strong> term "discrimination"<br />

had limited currency and was seldom applied to women. The refusal of an office<br />

to even entertain <strong>the</strong> idea of employing a woman could not be contested. Many women fully<br />

qualified by a university to take <strong>the</strong> first step into <strong>the</strong> profession were denied employment.<br />

Granted, <strong>the</strong>re was very little work at all in architecture in Canada during <strong>the</strong> 1930s, but this<br />

overt discrimination against women by architects' offices persisted through <strong>the</strong> boom period<br />

of <strong>the</strong> 1950s.<br />

There were, of course, exceptions to <strong>the</strong> prevailing attitude which excluded women<br />

from architects' offices. Like Elma Laird, a few of <strong>the</strong> earliest women to be licensed as architects<br />

did gain <strong>the</strong>ir credentials via <strong>the</strong> long term of apprenticeship. Never<strong>the</strong>less, even if<br />

hired by an office, a woman often had difficulty gaining a broad range of experience. She was<br />

frequently confined to work on domestic projects, particularly kitchens, and perhaps some<br />

small schools, but not more complex buildings that required a sophisticated knowledge of construction<br />

and engineering. And she was usually excluded from construction supervision,<br />

which is where a great deal is to be learned. She also was likely to be excluded from consultations<br />

with clients and contractors because it was assumed that <strong>the</strong>y would not have confidence<br />

in a woman.<br />

If and when a woman finally did achieve her goal and was registered as an architect,<br />

<strong>the</strong> social and political climate still placed her at a disadvantage with respect to her male<br />

peers. The daily press may represent an unduly unsophisticated view of society, but one might<br />

consider <strong>the</strong> following references to female architects- which presumably were acceptable,<br />

since no one objected to <strong>the</strong>m. In one report in a Toronto newspaper about Marjorie Hill's<br />

graduation from <strong>the</strong> University of Toronto in 1920, <strong>the</strong> headline read: "New Trail Blazed by<br />

a Varsity Girl," though <strong>the</strong> accompanying photograph of her convocation clearly showed a<br />

woman of some maturity. I do not find a reference to a "boy graduate" in architecture, let<br />

alone to a "boy architect," but <strong>the</strong> Canadian newspapers frequently referred to a female architect<br />

as a "girl." Admittedly, <strong>the</strong> more sophisticated Saturday Night did identify Hill as<br />

"Canada's First Woman Architect." 8 Then again, <strong>the</strong> Mail and Empire titled an article: "Miss<br />

Marjorie's Plans." 9<br />

In 1951, a Toronto newspaper described Barbara Harrison, who graduated from<br />

McGill in 1947, as "up to her attractive ears, you might say, in <strong>the</strong> building business." 10 Even<br />

in 1956, a Montreal newspaper carried <strong>the</strong> heading "Local Girl Architect Wins Award at<br />

Vienna Congress,'' 11 and this referred to a woman who had been working as an architect for<br />

eleven years and was an assistant professor of architecture at a university in <strong>the</strong> United<br />

States. Apart from such condescension, <strong>the</strong>re remained a general perception that women<br />

were not equal to <strong>the</strong> task, at least in anything more than a single-family home. And if she did<br />

gain <strong>the</strong> confidence of a client, <strong>the</strong>re remained <strong>the</strong> scepticism of <strong>the</strong> conservative construction<br />

industry, with an arsenal of weapons to undermine confidence.<br />

It is a wonder, <strong>the</strong>n, that Marjorie Hill did finally establish a practice of her own,<br />

and that she wea<strong>the</strong>red <strong>the</strong> Depression and o<strong>the</strong>r perils.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> decades from 1920 to 1939, of a total of 420 graduates from architecture<br />

schools in Canada, 19 were women. But by 1940, only two of <strong>the</strong>se women were licensed by a<br />

provincial association of architects: apart from Marjorie Hill in 1925, <strong>the</strong> Alberta Association<br />

of Architects registered Margaret Buchanan, a graduate of <strong>the</strong> University of Alberta school,<br />

in 1939. In this same period an additional three women were licensed, two having been educated<br />

in Europe and one entering <strong>the</strong> profession via apprenticeship. Sylvia Holland, educated<br />

in England, was licensed in British Columbia in 1933, and Alexandra Biriukova, educated in<br />

St. Petersburg and Rome, was licensed in Ontario in 1931. Biriukova is credited with <strong>the</strong> wellknown<br />

house for artist Lawren Harris at 2 Ava Crescent in Toronto {figure 5). Whe<strong>the</strong>r it<br />

was because of resistance to this frankly modernist house in conservative Toronto, or because<br />

of <strong>the</strong> Depression, she does not appear to have had additional commissions. 12 She trained as<br />

a nurse specialized in tuberculosis at West Park Hospital, York, graduated in 1934, and<br />

resigned from <strong>the</strong> OAA <strong>the</strong> same year. She remained at <strong>the</strong> hospital until her retirement in<br />

<strong>the</strong> 1960s, and is mentioned in The Story of Toronto Hospital as one of <strong>the</strong> longest serving<br />

tuberculosis nursesY Apparently, few in her later profession knew she had been an architect.<br />

Elma Laird also registered in Ontario in 1931. Having a business college education,<br />

she had worked for two contracting firms in Brant ford, Ontario, before serving an apprenticeship<br />

with architect F.C. Bodley. 14 But she, too, was a victim of <strong>the</strong> Depression, and after<br />

1934 worked as a secretary until her retirement in 1968.<br />

8 Saturday Night, 12 June 1920, p. 31.<br />

9 Mail and Empire, Toronto, 7 August 1920, p. 17.<br />

10 Glebe and Mail, Toronto, 20 January 1951, p. 12<br />

11 Montreal Star, August 1956.<br />

12 Geoffrey Simmins, Ontario Association of Architects: A<br />

Centennial History, 1889-1989 (foronto: University of<br />

Toronto Press for <strong>the</strong> Association, 1989), 110.<br />

13 Godfrey L. Gale, The Changing Years: The Story of<br />

Toronto Hospital and <strong>the</strong> Fight Against T uberculo.ris<br />

(foronto: West Park Hospital, 1979). I am grateful to<br />

Dorothy Field for this reference.<br />

14 Simmins, Ontario Association of Architects, 112<br />

17:1 SSAC BULLETIN SEAC<br />

9

Figure 5. Lawren Harris residence, 2 Ava Crescent,<br />

Toronto, built in 1931. The design is credited to<br />

Alexandra Biriukova. (Photo: B. L van Ginkel, 1991)<br />

By 1960, of <strong>the</strong> 2,400 architects registered in canada, only 30 were women. There<br />

were only ten women among <strong>the</strong> 1,010 registered in Ontario and five women among <strong>the</strong> 669<br />

in Quebec. However, Manitoba and Alberta each registered six women when <strong>the</strong> membership<br />

in each province was only about 160.<br />

It was not until <strong>the</strong> 1970s that women gained a recognizable presence among<br />

graduates of <strong>the</strong> canadian schools of architecture. <strong>From</strong> 1970 to 1979 <strong>the</strong>y represented 12<br />

percent of graduates, and from 1980 to 1985 <strong>the</strong>y were 25 percent. Consequently, it was not<br />

until <strong>the</strong> 1980s that <strong>the</strong>re was a meaningful increase in women's registration in <strong>the</strong> profession.<br />

In 1960 women were 1.2 percent of all registered architects in canada; in 1985 <strong>the</strong>y were 6.6<br />

percent.<br />

By 1990, women accounted for 7.7 percent of registered architects in Ontario, but<br />

<strong>the</strong> proportion had increased to 16 percent in Quebec. Considering that <strong>the</strong>re was not a<br />

woman registered in Quebec until 1942, and <strong>the</strong> second was not registered until 1952 (by<br />

which time all but <strong>the</strong> small maritime provinces had admitted women), this indeed represents<br />

a dramatic change in <strong>the</strong> profession in Quebec. Signals of change had appeared in 1971,<br />

when <strong>the</strong> first woman was elected to <strong>the</strong> council of <strong>the</strong> Quebec association, and two years<br />

later, when <strong>the</strong> first woman to sit on <strong>the</strong> council of <strong>the</strong> Royal Architectural Institute of<br />

canada was <strong>the</strong> representative from Quebec. Only Alberta had preceded Quebec's election<br />

of a woman to a provincial association council (in 1966). In Ontario it did not happen until<br />

1977.<br />

Considering <strong>the</strong> high proportion of women now in public life in Quebec, it might be<br />

reasonable to assume that <strong>the</strong> apparently higher regard for women architects in <strong>the</strong> province<br />

is a function of <strong>the</strong> fundamental societal change of <strong>the</strong> "Quiet Revolution" in <strong>the</strong> 1960s.<br />

There does seem to be a concurrence between <strong>the</strong> acceptance of women in architecture and<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir acknowledgement as citizens. Apart from <strong>the</strong> Quebec story, one might consider that <strong>the</strong><br />

first school of architecture to accept a female student was in Alberta; that Alberta and<br />

Manitoba in 1960 had by far <strong>the</strong> highest proportion of women among registered architects;<br />

and that <strong>the</strong>se two provinces, toge<strong>the</strong>r with Saskatchewan, were <strong>the</strong> first to enfranchise<br />

10<br />

SSAC BULLETIN SEAC 17:1

women (in 1916). I speculate, too, on whe<strong>the</strong>r this more generous acceptance of women as<br />

"persons" was due to <strong>the</strong> role that pioneering women had played in a tough territory.<br />

I am reminded of <strong>the</strong> story of women architects in Finland. I do not have recent<br />

figures, but in 1975 women represented 25 percent of <strong>the</strong> practicing architects, and in 1979,<br />

43 percent of <strong>the</strong> students in architecture were female. The first woman received a degree in<br />

architecture from <strong>the</strong> Polytechnic Institute in Helsinki in 1890, when Finnish nationalism was<br />

ga<strong>the</strong>ring force. Finland had a high degree of autonomy during <strong>the</strong> period when it was a<br />

duchy of <strong>the</strong> Russian Empire (1809-1917), and <strong>the</strong> nationalist movement was as much cultural<br />

(particularly counter to 650 years of Swedish culture) as it was political. It was a movement<br />

which belonged to <strong>the</strong> entire people, not just to an elite male group. Consequently,<br />

women were enfranchised and could hold office as early as 1906, and today about one-third<br />

of <strong>the</strong> members of parliament are women. In this social climate, a woman architect, Vivi<br />

LOnn, was commissioned to design <strong>the</strong> central fire station at Tampere in 1908, and Elsa<br />

Arokallio designed <strong>the</strong> Kauhava barracks for <strong>the</strong> Finnish army in 1923. 15<br />

Architecture is a cultural pursuit and those who practice it-or are allowed to practice<br />

it - reflect our culture, our mores, our attitudes, in Canada as elsewhere.<br />

But numbers are not all- and distinction in <strong>the</strong> profession is ultimately more important.<br />

It may be significant that <strong>the</strong> open competition in 1989 to design a new headquarters<br />

building for <strong>the</strong> Ontario Association of Architects was won by a woman, Ruth Cawker.<br />

O<strong>the</strong>rs have achieved distinction in recent years: Patricia Patkau of British Columbia, who,<br />

with her partner, won <strong>the</strong> national competition for <strong>the</strong> Clay and Glass Museum in Waterloo,<br />

Ontario, in 1982; Helga Plumb of Dubois/Plumb, who was awarded a Governor General's<br />

Medal for Architecture in 1983 for design of <strong>the</strong> Oaklands apartments in Toronto; and<br />

Brigitte Shim, whose work was featured on <strong>the</strong> cover of <strong>the</strong> prestigious Architectural Review<br />

in April1991.<br />

The only international institution in Canada devoted to architecture, <strong>the</strong> Canadian<br />

Centre for Architecture, in Montreal, was founded by Phyllis Lambert, who also received a<br />

Massey Medal of <strong>the</strong> Royal Architectural Institute of Canada as architect of <strong>the</strong> Saidye<br />

Bronfman Centre in Montreal. The liveliest and most innovative Canadian periodical on architecture,<br />

SECTION a, was founded and published by Odile Htnault. And 14 women have<br />

now been elevated to <strong>the</strong> status of Fellow of <strong>the</strong> RAIC. So, despite <strong>the</strong> painful process and<br />

slow pace, women surely are making <strong>the</strong>ir place in architecture in Canada, not merely in<br />

quantity but with quality.<br />

15 Profiles: PiOfleering W omm Architects from Finland<br />

(Helsinki: Museum of Finnish Architecture, 1983).<br />

I am grateful to Anne Ford for introducing me to<br />

Marjorie Hill; to David Hambleton, FRAIC, for<br />

interviewing her on my behaff; and to Mary Clarlr,<br />

MRAIC, from whose as·)'llt unpublished studies of<br />

women in architecture in Canada I obtained dllla on<br />

Canadian schools.<br />

Data on registration is from <strong>the</strong> provincial associations<br />

of architecture. lnformaoon on <strong>the</strong> UniwJrsity of Toronto<br />

is from <strong>the</strong> School of Architecture and Landscape<br />

Architecture, UniwJrsity Archives, and Faculty of<br />

Applied Science and Engineering.<br />

17:1 SSAC BUl.l.ETlN SEAC<br />

11

WALLBRIDGE<br />

The Architectural Practice of Two<br />

8 Y E R N A<br />

12<br />

SSAC BUUETIN SEAC 17:1

AND IMRIE<br />

Edmonton Women, 1950-1979<br />

DOMINEY<br />

Figure 1. The Queen Mary apartments in Edmonton,<br />

built between 1951 and 1953, were Wallbridge and<br />

Imrie's first effort in private practice. (Photo: Mary<br />

Bramley)<br />

17:1 SSAC BULLETIN SEAC<br />

13

T .J" Tomeo have made great strides in <strong>the</strong> architectural profession during <strong>the</strong> course of <strong>the</strong><br />

Y Y ~entieth century. While <strong>the</strong> experience of Canadian women has certainly not been<br />

easy, <strong>the</strong>ir numbers in this specialized field have grown substantially in <strong>the</strong> past thirty years. 1<br />

The few who took degrees in architecture during <strong>the</strong> first half of this century struggled first to<br />

gain entry, <strong>the</strong>n acceptance into <strong>the</strong> profession. Once <strong>the</strong>re, <strong>the</strong>y had to fight simply to stay in<br />

business. That <strong>the</strong> situation is no longer quite so difficult is in no small way due to <strong>the</strong> efforts<br />

of those women who had <strong>the</strong> courage to enter that most un-feminine realm, <strong>the</strong> construction<br />

industry. In Alberta, two such pioneering women were Jean Wallbridge and Mary Imrie.<br />

Wallbridge and Imrie were <strong>the</strong> third and fifth women respectively to join <strong>the</strong> Alberta<br />

Association of Architects, but <strong>the</strong> first in Edmonton to form <strong>the</strong>ir own architectural practice.<br />

They were in business from 1950 unti11979, when Jean died at <strong>the</strong> age of 67. By far <strong>the</strong><br />

majority of <strong>the</strong>ir architectural projects were of a domestic nature: private residences and<br />

apartment buildings, as well as both tract and row housing. This was typical of <strong>the</strong> experience<br />

of women architects, as <strong>the</strong> literature on <strong>the</strong> subject makes clear. According to Gwendolyn<br />

Wright, author of one of <strong>the</strong> first studies on women and architecture in North America,<br />

Those few women who were able to uke part seldom challenged ... or competed with <strong>the</strong> men who dominated architectural<br />

practice; instead <strong>the</strong>y took up <strong>the</strong> slack where <strong>the</strong>y could, performing jobs and concentrating on <strong>the</strong> services<br />

which <strong>the</strong>ir male colleagues ei<strong>the</strong>r put aside or treated only peripherally. 2<br />

Mary Imrie (standing) and Jean Wallbridge, 1947.<br />

(Alberta Recreation, Paries and Wildlife Foundation)<br />

1 Blanche Lemco van Ginkel, "Slowly and Surely {and<br />

Somewhat Painfully): More or Less <strong>the</strong> History of<br />

Women in Architecture in Canada," in this issue of<br />

<strong>the</strong> SSAC Bulletin {pp. 5-11 ).<br />

2 Gwendolyn Wright, "On <strong>the</strong> Fringe of <strong>the</strong> Profession:<br />

Women in American Architecture," in The Architect:<br />

Chaplen in <strong>the</strong> History of <strong>the</strong> Profession, ed. Spiro Kos·<br />

tof {New York: Oxford University Press, 1977), 280.<br />

3 Mary Imrie to Eric Arthur, 3 June 1954, Provincial<br />

Archives of Alberta.<br />

4 Frank Burlington Fawcett, ed., Their Majesties' Courts<br />

Held at Buckingham Palace 1932 (London: Grayson<br />

and Grayson, 1932), 115, 138.<br />

A spattering of ''women's fields," namely domestic architecture and interiors,<br />

evolved as areas of specialization where it was permissible for women to practice, since here<br />

<strong>the</strong>y were dealing with o<strong>the</strong>r women's needs. Wallbridge and Imrie's practice did indeed conform<br />

to this pattern, as Mary Imrie herself observed in a 19541etter to Eric Arthur, her<br />

former professor at <strong>the</strong> University of Toronto:<br />

Our business is still providing a meagre living, although it is not so booming as last year. If only we got more bigger<br />

jobs and fewer headachy ones, we would be considerably wealthier and happier. But that is probably one of <strong>the</strong> disadvantages<br />

of being female. People will get us to do <strong>the</strong>ir houses, be thrilled with <strong>the</strong>m and go to larger male firms for<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir warehouses or office buildings. 3<br />

There may be many reasons why <strong>the</strong>y focused on domestic architecture, but <strong>the</strong>se remain to<br />

be explored.<br />

Jean Wallbridge was born in Edmonton in 1912. She was schooled privately in Victoria,<br />

Switzerland, and England. Before returning home, she was presented by Lady Cunliffe<br />

Lister to King George V and Queen Mary at <strong>the</strong>ir Third Court on 23 June 1932. 4 This would<br />

seem to indicate a social position that would enable her to make career choices unavailable to<br />

most women at <strong>the</strong> time.<br />

She completed grade 12 at Edmonton's Victoria High School, <strong>the</strong>n enroled at <strong>the</strong><br />

University of Alberta. She was one of four women to graduate with a Bachelor of Applied<br />

Sciences in Architecture in <strong>the</strong> 27 -year history of <strong>the</strong> programme. Her teacher was Cecil Burgess,<br />

a Scottish architect who had come to Edmonton in 1913 via Montreal, after having been<br />

recommended by Percy Nobbs for <strong>the</strong> position of University Architect and Professor of<br />

Architecture. Burgess taught his students an Arts-and-Crafts respect for materials and a<br />

knowledge of <strong>the</strong> Classical orders.<br />

In 1939, her graduating year, Jean was awarded a fourth in Class A of <strong>the</strong> Royal<br />

Architectural Institute of Canada medals. Some of her student drawings are preserved in <strong>the</strong><br />

University of Alberta Archives. She took a Bachelor of Arts <strong>the</strong> following year, and on 6<br />

February 1941 she was registered with <strong>the</strong> Alberta Association of Architects.<br />

Her first job was with Rule, Wynn and Rule, a firm established by one of her<br />

classmates, Peter Rule. Her next position was with <strong>the</strong> Town Planning Commission in Saint<br />

John, New Brunswick, during World War II. She returned to Edmonton in 1946 to work as a<br />

draughtsman in <strong>the</strong> Department of <strong>the</strong> City Architect and Inspector of Buildings, where she<br />

remained until 1949.<br />

Mary Louise Imrie was born in Toronto in 1918. She moved to Edmonton in 1921,<br />

when her fa<strong>the</strong>r, John Mills Imrie, became publisher of The Edmonton JournaL He encouraged<br />

Mary in her interest in architecture and allowed her to design <strong>the</strong> family's lakeside<br />

cottage when she was 16. Mary received her education in <strong>the</strong> Edmonton public school system,<br />

completing high school in 1936. She took a ·secretarial course and <strong>the</strong>n worked for a year<br />

before enroling in architecture at <strong>the</strong> University of Alberta in 1938.<br />

Upon hearing that <strong>the</strong> architecture programme at <strong>the</strong> University of Alberta would<br />

no longer be offered after <strong>the</strong> retirement of Cecil Burgess, Mary applied to <strong>the</strong> University of<br />

Toronto and was accepted into second year architecture in 1940. The summers of 1941 and<br />

14<br />

SSAC BULLETIN SEAC 17:1

1942 were spent back home in Edmonton, employed in <strong>the</strong> office of Rule, Wynn. and Rule,<br />

who were on <strong>the</strong>ir way to becoming <strong>the</strong> most successful firm in <strong>the</strong> city. In 1944 she received<br />

her degree, but stayed in Toronto to work with architect Harold Smith on hospital projects.<br />

She <strong>the</strong>n moved to Vancouver to work in <strong>the</strong> office of architect C.B.K. Van Norman. By <strong>the</strong><br />

end of 1944 she had returned to Edmonton, joining <strong>the</strong> Alberta Association of Architects on<br />

7 December. 5<br />

Back with Rule, Wynn and Rule in 1945, Mary draughted plans for schools, offices,<br />

and industrial buildings. In 1946 she entered <strong>the</strong> office of <strong>the</strong> City Architect and Inspector of<br />

Buildings, and worked <strong>the</strong>re for four years. Although both she and Jean Wallbridge were<br />

registered architects, <strong>the</strong> pair accepted positions as draughtsmen on civic projects. It seems,<br />

however, that <strong>the</strong>y were highly regarded by <strong>the</strong> city architect, Max Dewar. In 1947 he recommended<br />

that <strong>the</strong>y be given three months' leave to take a study tour of post-war reconstruction<br />

and community planning in Europe.' City commissioner D.B. Menzies authorized <strong>the</strong><br />

leave, but did so reluctantly, insinuating that Dewar's office must be overstaffed for him to<br />

release staff at <strong>the</strong> height of <strong>the</strong> building season.<br />

Both women kept diaries and took photographs on this, <strong>the</strong> first of <strong>the</strong>ir many journeys<br />

toge<strong>the</strong>r overseas. These are now in <strong>the</strong> Provincial Archives of Alberta. Mary Imrie<br />

wrote articles on <strong>the</strong>ir travels, which she submitted to <strong>the</strong> Journal of <strong>the</strong> Royal Architectural<br />

Institute of Canada. 7 Their first contribution, "Planning in Europe," documenting <strong>the</strong> British<br />

leg of <strong>the</strong> journey, appeared in <strong>the</strong> October 1948 issue.<br />

The two women's contribution to <strong>the</strong>ir employer was not lost on <strong>the</strong> city architect,<br />

who, in 1949, recommended that <strong>the</strong>y be reclassified so that <strong>the</strong>ir wages could be increased.<br />

He suggested that Miss Wallbridge be given <strong>the</strong> title "Technical Assistant in Town Planning"<br />

and that Miss Imrie be known as "Junior Architect." In his letter to <strong>the</strong> commissioner, Dewar<br />

wrote<br />

Both <strong>the</strong>se girls, being registered architects, are much more valuable to this department than would be a draughtsman<br />

who would accept a salary of this amount I can assure you that it would be next to impossible to replace <strong>the</strong>m with experienced<br />

draughtsmen in this salary bracket 8<br />

Fur<strong>the</strong>r correspondence in <strong>the</strong> City of Edmonton Archives reveals that Dewar was unsuccessful<br />

in his bid to pay <strong>the</strong> two women <strong>the</strong> wages of experienced draughtsmen, let alone<br />

registered architects.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> December 1949 issue of <strong>the</strong> RAIC Journa~ it was noted in <strong>the</strong> column<br />

"News from <strong>the</strong> Institute" that <strong>the</strong> Misses Imrie and Wall bridge had resigned from <strong>the</strong>ir positions<br />

"to carry out private researches in South America." They took a full year to make <strong>the</strong><br />

long drive <strong>the</strong>re and back, and submitted an article on <strong>the</strong>ir travels, "South American Architects,"<br />

to <strong>the</strong> Journal in 1951.<br />

They were unable to return to <strong>the</strong>ir jobs with <strong>the</strong> city after <strong>the</strong>ir trip: Dewar had<br />

gone into private practice. Wallbridge and Imrie decided to follow suit. "The girls," as <strong>the</strong>y became<br />

known, established <strong>the</strong>mselves in an office in downtown Edmonton and began to look<br />

for commissions.<br />

As a result of <strong>the</strong>ir years in <strong>the</strong> City Architect's office <strong>the</strong>y knew projects were often<br />

submitted to <strong>the</strong> City Building Permits office without an architect's stamp. Mary Imrie found<br />

<strong>the</strong> firm's first job by going to see her former co-workers and <strong>the</strong>n following up <strong>the</strong> leads <strong>the</strong>y<br />

provided. 9 The Queen Mary apartments were three medium-sized apartment buildings of ten<br />

suites each (figure 1). They were built between 1951 and 1953 for a consortium from Regina<br />

of two dentists, a contractor, and a plasterer. The site was favourable for developers, located<br />

north of Edmonton's downtown, and relatively low in price because it had originally been part<br />

of <strong>the</strong> Hudson's Bay Reserve lands. Although not markedly different in appearance than<br />

most walkups of <strong>the</strong> time, <strong>the</strong> Queen Mary apartments are spacious, convenient, and well<br />

landscaped. They have been so well kept that, after forty years, <strong>the</strong>y are still commanding <strong>the</strong><br />

highest rents in <strong>the</strong> neighbourhood.<br />

<strong>From</strong> this beginning, <strong>the</strong> firm continued for nearly thirty years and undertook 224<br />

projects. Of <strong>the</strong>se, 67 were private residences. Most were in Edmonton, but <strong>the</strong>re were a few<br />

in Calgary, Red Deer, and Lloydminster. The firm designed 23 residential additions and alterations,<br />

including garages, fireplaces, and recreation rooms- many for houses <strong>the</strong>y had<br />

originally designed -as well as five lakeside cottages.<br />

Fifty of <strong>the</strong> firm's projects were apartments, mainly walkups but also row housing<br />

and what are listed in <strong>the</strong>ir files as "garden apartments." These seem to have been relatively<br />

inexpensive structures, for developer clients. Most were located in Edmonton but 11 were in<br />

nor<strong>the</strong>rn Alberta. The firm also designed tract housing for construction and lumber companies<br />

in Edmonton. 10<br />

5 Much of this biographical information on Mary Imrie<br />

was compiled by Mary Clark for <strong>the</strong> 1986 exhibition<br />

For <strong>the</strong> Record, which documented women graduates<br />

in architecture from <strong>the</strong> University of Toronto.<br />

6 M.C_ Dewar to <strong>the</strong> City Commissioners, 21 July 1947,<br />

City of Edmonton Archives.<br />

1 "Les Girls en Voyage," February 1958, pp. 44-46;<br />

"Hong Kong to Chandigarh," May 1958, pp-160-63;<br />

"Khyber Pass to Canada," July 1958, pp. 218-79.<br />

8 Max Dewar to Commissioner D.B. Menzies, 8<br />

February 1949, City of Edmonton Archives.<br />

9 Mary Clark, "Architectural Scrapbook" (unpublished),<br />

prepared for <strong>the</strong> exhibition For <strong>the</strong><br />

Record, University of Toronto Archives.<br />

10 These companies included Alldritt Construction,<br />

Maclab Construction, and Imperial Lumber.<br />

17:1 SSAC BULLETIN SEAC<br />

15

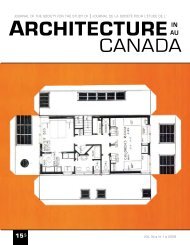

Figure 2 (above). Side view of Wallbridge and lmrHJ's<br />

home and office, Six Acres. The main living areas on<br />

<strong>the</strong> ground floor and <strong>the</strong> offiC8S and spare b«Jroom in<br />

<strong>the</strong> bllsernert face <strong>the</strong> ravine. (Provincial Archives of<br />

Albelta)<br />

Figure 3 (below). Ground floor plan of Six Acres. The<br />

compact open plan with built· in furniture demonstrates<br />

<strong>the</strong> simplicity and economical use of space that is<br />

typical of <strong>the</strong>ir worlr. (Provincial Archives of Alberta)<br />

v<br />

~~~~~..-~"!:::~~1!!!!'!~~m- ': -- ----= ---- --- ·- 0 0 ~~<br />

fUNd C.Uati !IM)U ) I. ; :<br />

t - - ·<br />

--,-- ~~ -:L -_ -_ ..-·'~<br />

't<br />

.,<br />

CR.OUOo.ID rLOOIIl. !<br />

i [ · & ·- .,<br />

. te ' 'T<br />

Late in <strong>the</strong>ir practice <strong>the</strong> firm designed three apartments for senior citizens in small<br />

centres for <strong>the</strong> Alberta government's Alberta Housing Corporation. The only o<strong>the</strong>r projects<br />

done for <strong>the</strong> Alberta government were three small town telephone exchanges (two were extensions<br />

to existing buildings), and <strong>the</strong> Department of Public Welfare's Diagnostic and<br />

Receiving Centre for young offenders in Edmonton, through <strong>the</strong> Department of Public<br />

Works.<br />

There are only 23 commercial projects listed in Wall bridge and Imrie's files. These<br />

include two small office buildings and two office alterations, a machine shop, two warehouses<br />

and an extension to one of <strong>the</strong>m, <strong>the</strong> Alberta Seed Growers' plant and a later addition to it,<br />

three stores, two alterations to stores, and one small shopping centre, all in Edmonton. Their<br />

firm also designed a radio and 1V station in Lloydminster, a hotel in Lac LaBiche, two<br />

motels and a restaurant in Jasper, and a burger drive-in in Edmonton. There was also a<br />

Roman Catholic church, St. James, in Edmonton (with a later addition), and a small museum<br />

made of logs, <strong>the</strong> Luxton, in Banff.<br />

According to architectural colleagues of Wall bridge and Imrie, this concentration<br />

on residential work differed markedly from <strong>the</strong> pattern of <strong>the</strong> typical architectural firm in Edmonton<br />

at <strong>the</strong> time. As Roy Gordon observed,<br />

I would think that most firms starting out would depend on house commissions to some degree but <strong>the</strong>y would<br />

18<br />

SSAC BULLETIN SEAC 17:1

Figure 4 (above). Lo-floor plan. (Provincial Archives<br />

of Alberta)<br />

Figure 5 (below). Dining room and kitchen. The openbeamed<br />

ceiling and <strong>the</strong> horizortal window between <strong>the</strong><br />

kitchen counter and cupboards are found in many of <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

houses. (Provincial Archives of Alberta)<br />

D<br />

.II&.•CA'If'AT&D<br />

.. •<br />

•<br />

D<br />

........... CAL n<br />

0<br />

w-.T&&•~&<br />

L.ow 1!. R.<br />

?LOOR.<br />

broaden <strong>the</strong>ir practice very quickly because house design was not a very lucrative practice. Domestic design doesn't<br />

have to be unremunerative. It is in Edmonton because of <strong>the</strong> circumstances. The houses are small and people are not<br />

prepared to pay you what it's worth for <strong>the</strong> design. 11<br />

When asked why his firm didn't do domestic work, one successful Edmonton architect stated<br />

flatly, "No money in it," and chuckled, "we couldn't charge what <strong>the</strong>y were worth. They [<strong>the</strong><br />

clients] would waste your whole afternoon talking about a kitchen and <strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong>y'd change<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir minds." 12 This is in direct contrast with what clients of Wall bridge and Imrie said of <strong>the</strong><br />

pair:<br />

I think <strong>the</strong> one thing about <strong>the</strong>m that architects or all professional people would do well do emulate was <strong>the</strong>ir ability<br />

to combine business with pleasure. You didn't feel as if <strong>the</strong>y were punching a time clock or charging you $40 apiece<br />

for every phone call. 13<br />

By all accounts, "<strong>the</strong> girls" were extremely conscientious about meeting <strong>the</strong> clients'<br />

needs and designing houses that would "fit" and make <strong>the</strong>m happy. Here's what ano<strong>the</strong>r<br />

client recalled:<br />

I didn't want any hot shot architect telling me what I wanted .... There weren't any conflicts with <strong>the</strong>m, <strong>the</strong>y listened and<br />

<strong>the</strong>y advised ... and I was amazed at how <strong>the</strong>y could produce a house that pleased us so well with so little instruction ....<br />

II InTerview with Roy Gordon of Gordon Mangold<br />

Hamilton Architects, 28 June 1991.<br />

12 Interview with Gor,don Wynn of Rule, Wynn and<br />

Rule, Architects, rt June 1991.<br />

13 Interview with Mamie and Sanford T. Fitch, 21 June<br />

1991. The Fitch family took occupancy in Aprill967.<br />

17:1 SSAC BULLETIN SEAC<br />

17

Fi(JUre 6. v-of <strong>the</strong> ravine and Notfh<br />

Sas/attc'-17 River from <strong>the</strong> dining room. (Provincial<br />

Archi'les of AJ~)<br />

But it was really such a wonderful experience for us and we were so fond of <strong>the</strong>m .... After 23 yean, I would hate to be<br />

parted from <strong>the</strong> house. 14<br />

14lnterviewwith Mn. Jean Ward, 20June 1991. Mn.<br />

Ward and her late husband Henry moved into <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

house in October 1968.<br />

Wallbridge and Imrie's own home, which <strong>the</strong>y began in 1954, will serve as an introduction<br />

to <strong>the</strong>ir architectural style. In May 1957 <strong>the</strong>y moved into <strong>the</strong> combined home and office,<br />

named "Six Acres" after <strong>the</strong> size of <strong>the</strong> property. Originally just a weekend shack, <strong>the</strong>y<br />

built a large part of it <strong>the</strong>mselves, including <strong>the</strong> window frames, and became, in Mary Imrie's<br />

words, "half-decent carpenters."<br />

As with many of <strong>the</strong>ir projects, <strong>the</strong> house was built on a river bank, taking full advantage<br />

of <strong>the</strong> beautiful view (figure 2). The compact open plan with built-in furniture<br />

demonstrates <strong>the</strong> simplicity and economical use of space that is typical of <strong>the</strong>ir work (fagures<br />

3, 4). The open-beamed ceiling and <strong>the</strong> long horizontal window between <strong>the</strong> kitchen counter<br />

and cupboards are found in many of <strong>the</strong>ir houses (figure S). The house's front elevation is unassuming,<br />

as <strong>the</strong> main living area was located at <strong>the</strong> rear, oriented toward <strong>the</strong> view (figure 6).<br />

Their office, located in <strong>the</strong> basement, had large windows because of <strong>the</strong> drop in elevation. On<br />

her death in April 1988, Mary Imrie left Six Acres to <strong>the</strong> Alberta Recreation, Parks and<br />

Wildlife Foundation.<br />

While <strong>the</strong>ir architectural practice did not conform to that of most firms in Edmonton<br />

at <strong>the</strong> time - <strong>the</strong>y were hands-on, "studio" architects who specialized in domestic architecture<br />

-contemporaries agree <strong>the</strong> two were spirited, talented, capable architects and a<br />

credit to <strong>the</strong> profession in <strong>the</strong> province. In <strong>the</strong>ir careers Jean Wallbridge and Mary Imrie overcame<br />

<strong>the</strong> obstacles placed before Canadian women architects. Wall bridge and Imrie's 30-year<br />

practice demonstrates that success, on <strong>the</strong>ir own terms as well as <strong>the</strong>ir profession's, was possible-<br />

if not easy.<br />

Ema Dominey, a graduate student in M History at <strong>the</strong><br />

University of Alberta, is IIK)rlcing on a Master's <strong>the</strong>sis on<br />

<strong>the</strong> Edmonton firm of Wallbridge and Imrie, Architects.<br />

At this early stage most effort has been of a<br />

•reconnaissance· nature: reading through <strong>the</strong> firm's<br />

project files in <strong>the</strong> Provincial Archives of Alberta,<br />

identifying and locating <strong>the</strong>ir buildings, conacting <strong>the</strong><br />

current Ownet3, and photographing as many projects<br />

as possible.<br />

Happily, many of <strong>the</strong> houses are still occupied by <strong>the</strong><br />

original clients, many of whom have been willing to<br />

participate in an oral history project to ga<strong>the</strong>r more<br />

data about Wallbridge and Imrie. And many of <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

friends and colleagues have also co-operated,<br />

providing valuable information impossible to obtain<br />

through written sources.<br />

18<br />

SSAC BULlETIN SEAC 17:1

WOMEN AND THE<br />

BUILT ENVIRONMENT<br />

A course for students in <strong>the</strong> Masters of Architecture and Planning Program at <strong>the</strong><br />

Technical University of Nova Scotia, Halifax<br />

1n 1984, a group of women consisting of architectural<br />

students, practising architects, and local artists<br />

decided to meet regularly to read articles about<br />

art and architecture with a feminist <strong>the</strong>me. Each<br />

week a different member of <strong>the</strong> group would suggest<br />

a reading for discussion. It was from <strong>the</strong>se grass<br />

roots beginnings that <strong>the</strong> course "Women and <strong>the</strong><br />

Built Environment" evolved and became an official<br />

entry in <strong>the</strong> calendar of <strong>the</strong> School of Architecture<br />

and Planning at Technical University of Nova Scotia<br />

(TUNS).<br />

Having been asked to instruct <strong>the</strong> course,<br />

my first plan of attack was to approach Sherry<br />

Ahrentzen, a faculty member at <strong>the</strong> School of Architecture<br />

and Planning at <strong>the</strong> University of Wisconsin<br />

who had recently published an article about a similar<br />

By Maria Somjen<br />

course in Women and <strong>the</strong> Environment magazine.<br />

Ahrentzen sent us an outline with <strong>the</strong> names of<br />

o<strong>the</strong>rs who taught similar courses: Rochele Martin,<br />

Chris Cook, Susan Saegert, and Canadians Gerda<br />

Werkele and Rebecca Peterson.<br />

The TUNS course structure is similar to<br />

o<strong>the</strong>rs in that it provides a general survey of women<br />

in <strong>the</strong> roles of creators, consumers, and critics of <strong>the</strong><br />

built environment. The objective of <strong>the</strong> course is to<br />

create an awareness of <strong>the</strong> built environment as a<br />

feminist issue. Although many references are<br />

provided to <strong>the</strong> students taking <strong>the</strong> course, <strong>the</strong> main<br />

texts are Women in American Architecture: A Historic<br />

and Contemporary Perspective, edited by Susanna<br />

Torre, and Redesigning <strong>the</strong> American Dream, by<br />

Dolores Hayden.<br />

Carolyn Wallace (centre) and<br />

Maria Somjen (right) in<br />

conversation with former student<br />

Kathleen Robbins. (Photo: Paul<br />

Toman, TUNS)<br />

17:1<br />

SSAC BULLETIN SEAC<br />

19

Students at <strong>the</strong> TUNS School of<br />

.ArchitBcture and Planning<br />

examine a model of <strong>the</strong><br />

conceptual design for <strong>the</strong> new<br />

GST building, designed by Carol<br />

Rogers, an architect with Public<br />

Worlcs Canada. (Photo: Paul<br />

Toman, TUNS)<br />

The course is composed<br />

of three parts, based on <strong>the</strong> roles<br />

described above. In addition, an<br />

introduction to <strong>the</strong> course surveys<br />

<strong>the</strong> women's movement and<br />

culminates with an explanation of<br />

feminism as a discipline of study.<br />

Carolyn Wallace and I do this<br />

quick survey because we have students<br />

who come from diverse<br />

backgrounds: this introduction<br />

attempts to put <strong>the</strong> students on<br />

an equal footing.<br />

The first part of <strong>the</strong><br />

course, "Women as Producers of <strong>the</strong> Built Environment,"<br />

is a series of lectures and presentations by<br />

students which surveys <strong>the</strong> unacknowledged role of<br />

women in <strong>the</strong> production of architecture. Traditionally,<br />

history and <strong>the</strong>ory courses in architecture follow<br />

a standard approach which deals with great men,<br />

great monuments or great movements and totally ignores<br />

<strong>the</strong> roles and contributions of women. When<br />

American Modernism or <strong>the</strong> European movements<br />

are analyzed, women- even those notable by virtue<br />

of <strong>the</strong> fact that <strong>the</strong>y worked alone, as was <strong>the</strong><br />

case with architects Julia Morgan, Eileen Grey, and<br />

Eleanor Raymond - are ignored in most textbooks.<br />

And when we look at women architects such as Lily<br />

Reich, Denise Scott Brown, and Marion Mahoney<br />

Griffin, who worked side by side with famous men,<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir accomplishments are often obscured or discounted<br />

because of <strong>the</strong>ir associations with <strong>the</strong>se<br />

men.<br />

Historically, <strong>the</strong> design of domestic architecture<br />

was considered a role for which women were<br />

eminently suited. At <strong>the</strong> same<br />

time, domestic architecture was<br />

denigrated as not being "serious<br />

architecture." For example, one of<br />

<strong>the</strong> women designers most widely<br />

mentioned in histories of architectural<br />

design is Ca<strong>the</strong>rine Beecher,<br />

who, though she worked to<br />

redesign <strong>the</strong> american home (particularly<br />

<strong>the</strong> kitchen) within a<br />