CANADA - SEXTONdigital

CANADA - SEXTONdigital

CANADA - SEXTONdigital

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

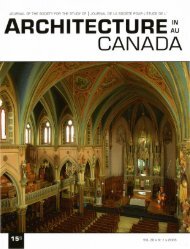

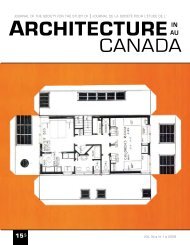

JOURNAL OF THE SOCIETY FOR THE STUDY OF I JOURNAL DE LA SOCIETE POUR L'ETUDE DE L'<br />

ARCHITECTURE!~<br />

<strong>CANADA</strong><br />

VOL. 32 > No 1 > 2007

PRFS IDE!JT<br />

PRESIDE'{!<br />

PIERRE DUPREY<br />

Department of Art<br />

Ontario Hall<br />

Queen's Uni versity<br />

Kingston, ON KZL 3N6<br />

(613 ) 533 -6166 1 f (6 t3) 533 -689 1<br />

e pduprey@ post.queensu .ca<br />

THE SOCIETY FOR THE STUDY OF ARCHITECTURE I N <strong>CANADA</strong> is a learned society<br />

devoted to the examination of the role of t he built environment in Canadian society. Its membership includes<br />

structural and landscape architects, architectural historians and planners, sociologists, ethnologists, and<br />

specialists in such fields as heritage conservation and landscape hi story. Founded in 1974, the Society is currently<br />

the sole national society whose focus of interest is Canada's built environment in all of its manifestations.<br />

The Journal of the Society for the Study of Architecture in Canada, published twice a year, is a refereed journal.<br />

Membership fe es, including subscription to the Journal, are payable at the following rates: Student, $30;<br />

lndividual,$50; Organization I Corporation, $75; Patron, $20 (plus a donation of not less than $100).<br />

Institutional subscription: $75. lndividuel subscription: $40.<br />

There is a surcharge of $5 for all foreign memberships. Contributions over and above membership fees are welcome,<br />

and are tax-deductible. Plea se make your chequ e or money order paya ble to the:<br />

SSAC >Box 2302, Station 0, Ottawa, Ontario, K1P 5W5<br />

LA SOCIETE POUR L'ETUDE DE l 'ARCHITECTURE AU <strong>CANADA</strong> est une societe savante qui se<br />

consacre a l'etude du role de l'environnement bati dans Ia societe can adienne. Ses membres sont architectes,<br />

architectes paysagistes, historiens de l'architecture et de l'urbanisme, urbanistes, sociologues, ethnologues<br />

ou specialistes du patrimoine et de l 'histoire du paysage . Fondee en 1974, Ia Societe est presentement Ia seule<br />

ass ociation nationale preoccupee par l'environnement bati du Canada sou s toutes ses formes.<br />

Le Journal de Ia Societe pour /'etude de /'architecture au Canada, publie deux lois par an nee, est une revue doni les<br />

articles sont evalues par un comite de lecture.<br />

La cotisation annuelle, qui comprend l'abonnement au Journal, est Ia suivante : etudiant, 30 $; individuel, 50$;<br />

organisation I societe, 75$; bienfaiteur, 20$ (plus un don d'au mains 100$).<br />

Abonnement institutionnel: 75 $. Abonnement individuel: 40$<br />

Un supplement de 5$ est demande pour les abonnements etrangers. Les contributions depassant l'a bonnement<br />

annuel sont bienvenues et deductibles d'imp6t. Veuillez s.v.p. envoye r un cheque ou un mandai postal a Ia :<br />

SEAC > c.,., postale 2302, succursale 0, Ottawa, Ontario, K1P 5W5<br />

www.canada-architecture.org<br />

The Journal of the Society for the Study of Architecture Jtl Canada is produced<br />

with the assistance of the Socia l Sciences and Huma nities Resea rch Council of<br />

Ca nada and the Ca nada Resea rch Chair on Urban Heritage, UQAM.<br />

Le Journal de Ia Societe pour /'etude de /'architecture au Canada est pub lie<br />

avec I' ai de du Consei l de recherches en sciences humain es du Ca nada et de<br />

Ia Chaire de recherche du Canada en patrimoine urba in, UQA M.<br />

Publication Mail 407391 47 > PAP Registrati on No. 10709<br />

We acknowledge the financial assistance of the Govern ment of Canada,<br />

through the Publ ications Assrstance Program (PAP), toward our mai lr ng costs.<br />

ISSN 1486·0872<br />

(supersedes I remplace ISSN 0228-0744)<br />

EDITlNC. PROOFREADING, lMNSLA> ION REVISIOIILINGUISIIQUr IRADU CTrO•'i<br />

MICHELINE GIROUX-AUBIN<br />

GRAPHIC DESIGN I CO!XEPTION GRAPH IQUE<br />

MARIKE PARADIS<br />

PAGE MAKE UP<br />

B GRAPHI STES<br />

pp,GfS<br />

PfUNTl t,;G! : ~JPRESS!ON<br />

MARQUIS IMPRIMEUR INC. , MONTMAGN Y (QC)<br />

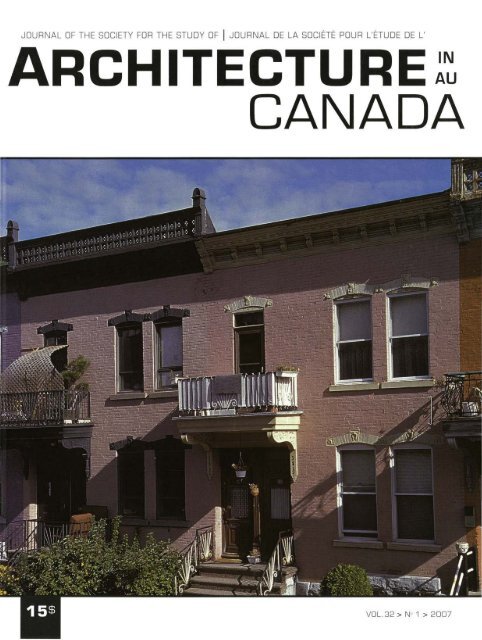

COVER COUVFRTIJRE<br />

Montreal. Ma isons de Ia rue Clark (3825-3851) .<br />

(PHOTO: LUC NOPPEN)<br />

JOUR!J.AI EDITOR REDACTEUR DU JOUR!•!.AL<br />

LUC NOPPEN<br />

Chaire de recherche du Canada en patrimoine urba in<br />

lnstitut du patrimoine<br />

Universite du Quebec a Montreal<br />

CP 88 88. succ. centre-ville<br />

Montrea l. QC H3C 3P8<br />

(514) 987 3000 x-2 562 1 f : (514) 987-78 27<br />

e nopp en .l uc@ uqam .ca<br />

to r !OR .ADJOINT .A LA REDACTION<br />

(FRA'l(OPHONE)<br />

MARTIN DROUIN<br />

e drou in .martin@uqam.ca<br />

ASSISTN!T EDITOR .ADJO INT .A. LA REDACTION<br />

(ANGLOPHO NE)<br />

PETER COFFMAN<br />

e · peter.coffman@sympatico.ca<br />

'iJEB S!TL ' S!TE \-V LB<br />

LANA STEWART<br />

Parks Ca nada<br />

25, Eddy Street, 5th Floor<br />

Gatrnea u, QC K1 A OMS<br />

(8 19) 997-6098<br />

e lana .stewart@pc.gc .ca<br />

& VIEWS !<br />

REDACT DE NOUVELL ES ET COUPS D'CEIL<br />

HEATHER BRETZ<br />

5tantec Architecture ltd .<br />

200 - 325 - 25th Street SE<br />

Ca lgary, AB T2A 7H8<br />

(403) 71 6-7901 I f (403) 716 8019<br />

e · heather.bretz@stantec.com<br />

VICE PRtSIDHITS VICF·PRES!DE\i f (E)S<br />

ANDREW WALDRON<br />

Architectural Historian, Na ti ona l Historic Sites Directorate<br />

Parks Canada<br />

5'" Floor, 25 Eddy Street<br />

Hull, QC K1A OMS<br />

(819) 953-5587 If. (819) 953 -4909<br />

e andrew.waldron@ pc.gc .ca<br />

LUCIE K. MORISSET<br />

Etudes urba ines et touristiques<br />

Ecole des sciences de Ia gestion<br />

Un iversite du Quebec a Montreal<br />

C.P. 8888. su cc. Centre-vrlle<br />

Montreal. QC H3C 3P8<br />

(514) 987·3000 X 4585 I f (5 14) 987-7827<br />

e · morisset .l ucie@uqam .ca<br />

I RI:.Ao!JRER i I RfSORitR<br />

BARRY MAGRILL<br />

8080 Dalemore Rd<br />

Richmond. BC V7C 2A6<br />

barrymagri ll@shaw.ca<br />

SECRETARY!<br />

MARIE-FRANCE BISSON<br />

Ecole de design, UQAM<br />

Case postale 8888, succursale « Centre·ville ))<br />

Montreal, QC H3C 3P8<br />

(514 ) 987-3000 X 3866<br />

e · bissonmf@yahoo.ca<br />

PROVI !>lCiAL RFPR FSHJT.ATiVES !<br />

REPR f SFNfMH( FIS DES PROVIWfS<br />

GEORGE CHALKER<br />

Heritage Foundation of Newfou ndl and and Labrador<br />

P.O. Box 5171<br />

St. John's, NF A1C 5V5<br />

(709) 739 -1892 If. (709) 739 -5413<br />

e. george@heritagefoundation.ca<br />

TERRENCE SMITH LAMOTHE<br />

1935 Vernon<br />

Hali fa x, NS B3H 3N8<br />

(902) 425-0101<br />

THOMAS HORROCKS<br />

ADilimited<br />

11 33 Regent Street, Sui te 300<br />

Fredericton. NB E3B 3Z2<br />

(506) 452 -9000 If (906) 452-7303<br />

e · thd@adi.ca I horto@ reg2.h ea lth.nb .ca<br />

CLAUDINE DEOM<br />

2078, avenue Claremont<br />

Montrea l. QC H3Z 2P8<br />

t I f · (514) 488-4071<br />

e · cdeom@supernet .ca<br />

SHARON VATTAY<br />

11 Elm Avenue. Apt #3 22<br />

Toronto. ON M4W 1 N2<br />

(41 6) 964·7235<br />

svattay@chass.utoronto.ca<br />

TERRENCE J. SINCLAIR<br />

Heritage Branch<br />

Saskatchewan Depa rtmen t of Mun icipa l Affairs,<br />

Culture and Housing<br />

430·1855 Victoria Avenue<br />

Regina. SK S4P 3V7<br />

(3 06 ) 787·5777 I f · (306) 787-0069<br />

e · ts in cl air@mach. gov.sk .ca<br />

L. FREDERICK VALENTI~E<br />

Stantec Architecture Ltd.<br />

200 · 325 - 25th Street IE<br />

Ca lgary. AB T2A 7H 8<br />

(403) 716 -7919 If (40 3) 716-8 01 9<br />

e . fred .valentin e@stantec .com<br />

DANIEL MILLETTE<br />

511-55 Water Street<br />

Vancouver, BC V6B 1A1<br />

t If (604) 687-4907<br />

e · lucubratio@yahoo .com<br />

KAYHAN NADJI<br />

126 Niven Dr.<br />

Yellowkni fe. NT X1A 3W8<br />

t I f : (867) 920-633 1<br />

e kayen@nadji _architects .ca<br />

SHELLEY BRUCE<br />

25 Forks Market Road# 40 1<br />

Winnipeg, MB R3C 4S8<br />

(204) 983-2221<br />

ANN HOWATT<br />

P.O. Box 23 11<br />

Charlottetown, P. E.I. C1A 8C1<br />

(902) 626-8076<br />

e: ahowatt@ upe i.ca

CONTENTS I TABLE DES MATIERES<br />

JOURNAL OF THE SOCIETY FOR THE STUDY OF I JOURNAL DE LA SOCIETE POUR L'ETU DE DE L'<br />

ARCHITECTURE~~<br />

<strong>CANADA</strong><br />

ANALYSES I ANALYSES<br />

REPORT I RAPPORT<br />

> MICHELANGELO SABATINO<br />

A Wigwam in Venice:<br />

The National Gallery of Canada Builds a Pavilion,<br />

1954-1958<br />

> MARIE-BLANCHE FOURCAOE<br />

La creation d'une petite Armenie ou les multiples usages<br />

d'un sous-sol au Quebec<br />

> SARAH BASSNETT<br />

Visuality and the Emergence of City Planning in Early<br />

Twentieth-Century Toronto and Montreal<br />

> SHANE O'DEA AND<br />

PETER COFFMAN<br />

William Grey: 'Missionary' of Gothic in Newfoundland<br />

> MALCOLM THURLBY<br />

Two Churches by Frank Wills:<br />

St. Peter's, Barton, and St. Paul's, Glanford, and<br />

the Ecclesiological Gothic Revival in Ontario<br />

> RHONA GOODSPEED<br />

Saskatchewan Legislative Building and Grounds<br />

3<br />

15<br />

21<br />

39<br />

49<br />

61<br />

VOL. 32 > No 1 > 2007

•<br />

pr1x<br />

Phyllis-Lambert • pr1ze<br />

Appel de candidatures<br />

Chaque annee l'lnstitut du patrimoine de I'UQAM decerne le Prix<br />

Phyll is-Lambert a un(e) candidat(e) qui a soumis Ia meilleure these<br />

de doctorat ou le meilleur memoire de maitrise portant sur<br />

l'histoire de !'architecture au Canada selon !'evaluation qui en est<br />

faite par un jury independant.<br />

Le prix honore Phyllis Lambert, architecte et figure tutela ire de Ia<br />

conservation architecturale, fondatrice du Centre Canadien<br />

d' Architecture, institution montrealaise mondialement reconnue<br />

pour son engagement dans Ia lutte pour Ia qualite du paysage<br />

construit.<br />

Chaque an nee, au plus tard a Ia fin du mois de janvier, l'lnstitut du<br />

patrimoine de I'UQAM lance un appel au sein de Ia communaute<br />

des historiens d'architecture et des architectes du Canada pour<br />

que soient soumis les theses ou memoires ayant pour theme<br />

l'histoire de !'architecture au Canada (histoire, theorie, critique et<br />

conservation) et completes dans les deux annees precedentes.<br />

Les documents soumis sont evalues par un jury national dont<br />

l'lnstitut du patrimoine de I'UQAM nom me les membres.<br />

Le Prix Phyllis-Lambert consiste en un certificat de reconnaissance<br />

accompagne d'une bourse de 1 500 $, versee par Ia Fondation de<br />

I'UQAM. L'lnstitut du patrimoine offre par ailleurs une aide a Ia<br />

publication du texte recompense, dans l'une de ses collections ou<br />

chez un editeur independant. L'ouvrage publie portera en couverture<br />

Ia mention « Prix Phyllis-Lambert ». Le prix est rem is lors d'une<br />

activite speciale, inscrite dans le programme du congres annuel de<br />

Ia Societe pour l'etude de !'architecture au Canada (SEAC) qui se<br />

tient en alternance dans differentes villes du Canada. L'auteur(e)<br />

du texte prime est invite(e) a presenter une conference publique<br />

sur son travail; ses frais de voyage et de sejour sont pris en charge<br />

par l'lnstitut du patrimoine avec l'appui de Ia Fondation de<br />

I'UQAM.<br />

Les candidats doivent envoyer une copie de leur manuscrit<br />

termine en 2005 ou 2006 (memoire ou these) accompagne d'une<br />

lettre d'appui de leur directeur de recherche a l'lnstitut du<br />

patrimoine.<br />

Call for candidacies<br />

Each year, the Phyllis Lambert Prize is awarded by UQAM's lnstitut<br />

du patrimoine to a candidate who has submitted the best<br />

doctoral dissertation or best master's thesis on the subject of<br />

architectural history in Canada, based on the assessment of an<br />

independent jury.<br />

This prize honours Phyllis Lambert, architect and tutelary figure<br />

of architectural conservation, founder of the Canadian Centre<br />

for Architecture, a Montreal institution renowned worldwide for<br />

its involvement in the promotion of the quality of the built<br />

environment.<br />

Each year, at the latest by the end of January, UQAM's lnstitut du<br />

patrimoine asks the community of Canadian architectural historians<br />

and architects for the submission of dissertations and theses<br />

dealing with Canadian architectural history (history, theory,<br />

critics, and conservation) that have been completed during the<br />

two previous years. The documents submitted are evaluated by a<br />

national jury whose members are appointed by UQAM's lnstitut<br />

du patrimoine.<br />

The Phyllis Lambert Prize consists of a certificate of recognition<br />

that comes with a $1500 scholarship, awarded by the Fondation<br />

UQAM.In addition, the lnstitut du patrimoine offers assistance for<br />

the publication of the prize-winning text, either in one of its<br />

collections or with an independent publisher. The cover page of<br />

the publication will bear the mention "Prix Phyllis-Lambert."The<br />

prize will be awarded during a special ceremony included in the<br />

program of the annual conference of the Society for the Study of<br />

Architecture in Canada (SSAC) - held in turn in various cities<br />

throughout Canada. The recipient will be invited to present a<br />

public lecture related to his/her work; his/ her travel and living<br />

expenses will be paid by the lnstitut du patrimoine, with the<br />

support of the Fondation UQAM.<br />

Candidates must send a copy of their manuscript completed in<br />

2005 or 2006 (doctoral dissertation or master's thesis) with a<br />

letter of support from their supervisor at the lnstitut du<br />

patrimoine.<br />

Les manuscrits doivent parvenir au plus tard le 1 5 avril 2007, a l'adresse suivante:<br />

Manuscripts should be sent by April 15th, 2007, at the following address:<br />

lnstitut du patrimoine<br />

Prix Phyllis-Lambert<br />

Universite du Quebec a Montreal<br />

279, rue Sainte-Catherine Est, local DC-1200<br />

Montreal (Quebec) H2X 1 LS<br />

Information :<br />

Marie-Blanche Fourcade<br />

courriel I email: fourcade.marie-blanche@uqam.ca<br />

Telephone I Phone : (514) 987-3000, poste 5626<br />

Telecopieur I Fax: (5 14) 987-6881<br />

UQAM<br />

Prenez position<br />

UQAM<br />

lnstitut du patrimoine<br />

Universite du Quebec a Montreal

ANALYSIS I ANALYSE<br />

A WIGWAM IN VENICE:<br />

THE NATIONAL GALLERY OF <strong>CANADA</strong> BUILDS A PAVILION,<br />

1954-1958<br />

MICHELANGELO SABATINO (Ph.O.J is Assistant<br />

Professor at the Gerald D . Hines College of<br />

>MICHELANGELO SABATIN0 1<br />

ArchitectUI'e of the University of Houston. His<br />

publications have appea1'ed in "Casabella," "Harvard<br />

Design Magazine," "Rotunda," and "JSAH." He<br />

has contributed an essay to Foro ltalico (20031<br />

and co-edited II nuovo e if moderno in architettura<br />

12001 J. Sabatino's forthcoming book is entitled<br />

Or'dinary Things: Folk Art and Architecture in Italian<br />

Modernism.<br />

Ca nada has built an intricate wigwam of<br />

glass and w ood around a t ree, presumabl y<br />

to symbol ize lov e o f nature. In truth,<br />

perhaps all the p avili ons are, to some<br />

extent, folkloric.<br />

- Lawrence Alloway, The Venice 8 iennale<br />

1895-1968.<br />

FIG. 1. BIRDS EYE VIEW, CANADIAN PAVILION, VENICE.<br />

Canada's first permanent international<br />

pavilion for the display of art opened<br />

to the general public on the grounds<br />

of the Venice Biennale in June 1958.'<br />

The Milanese architectural firm Studio<br />

Architetti BBPR designed the brick, glass,<br />

wood, and steel wigwam-like structure<br />

on commission from the National Gallery<br />

of Canada acting on behalf of the Canadian<br />

Government (figs. 1-3). The pavilion<br />

opened the same year in which BBPR's<br />

controversial Milanese Torre Velasca and<br />

Brussels Pavilion were completed. The<br />

English critic Reyner Banham hailed those<br />

two works as evidence of Italy's "retreat"<br />

from the modern. 3 Compared with the<br />

international style Canadian Pavilion by<br />

Charles Greenberg at the 1958 Brussels<br />

World's Fair, the Venice Pavilion offers<br />

a distinct Canadian character for spectators<br />

to contemplate. It is a testimony<br />

to engagement with issues of national<br />

identity in architecture during difficult<br />

years following the end of World War II.<br />

The modernism of the Canadian Pavilion<br />

opposed the neutrality of the international<br />

" white box" that would dominate<br />

art exhibition spaces in the 1960s. That<br />

divergence was typical of Italian architects<br />

during the 1950s. Carlo Scarpa,<br />

Franco Albini, and the Studio Architetti<br />

BBPR came up with singular responses<br />

to the design of museums; rather than<br />

JSSAC I JSEAC 32 > N' 1 > 2007 > 3-14<br />

3

M ICHELANGELO S ABATINO > ANALYSIS I ANALYSE<br />

FIG. 2. IN TER IOR, CANADIAN PAVI LI ON, VENIC E.<br />

;;<br />

-B<br />

L----------------------------------------------------~~<br />

FIG. 3. PERSPECTIVE DRAWING, CANADIAN PAVI LIO N, STUDIO ARC HI TETTI BBPR.<br />

viewing the buildings as containers of moveable<br />

objects, the architects permanently<br />

embedded art objects in the architecture.<br />

Such an approach w as encouraged by the<br />

fact that architects in postwar Italy were<br />

faced w ith the delicate task of restoring<br />

or adapting extant buildings for museums<br />

rather than designing new ones 4<br />

The qualities that make this quirky and<br />

idiosyncratic pavilion significant in the<br />

history of Italian as w ell as Canadian<br />

architecture and culture ha ve also made<br />

it difficult for art curators over the last<br />

decades to display w ork of various shapes<br />

and sizes. Th e pavilion was conceived for<br />

paintings, draw ings, and sculpture, without<br />

considering the possibility that new<br />

media might one day expand the field<br />

of art. Its inflexibility is one reason for<br />

the paucity of studies on the building's<br />

history. 5 The conflict betw een form and<br />

use-not unlike Frank Lloyd Wright's<br />

Guggenheim Muse um in New York<br />

(1959)-emerged early on; just t w o years<br />

after the grand opening in 1958, Claude<br />

Picher-a National Gallery Liai son Officer<br />

for ea stern Canada-raised concerns<br />

about the pavilion's capacity to fulfill its<br />

program : "I w as told by se rious people<br />

that the Venice Pavilion w as constructed<br />

in such an aesthetic w ay that you could<br />

not decently see one painting on its w alls,<br />

because of the tree in the centre and the<br />

continuous moving areas of light and<br />

shadow its creates" 6 (figs. 4-5) .<br />

Irritation at the aw kwardness of the exhibition<br />

space con ceals a more deep-seated--<br />

if unspoken--criticism of the underlying<br />

message ofthe pavilion. By using an indigenous<br />

w igw am as a source of inspiration<br />

for the pavilion, the designers w ere venturing<br />

into national identity building, an<br />

arena that rarely finds all parties in agree-<br />

ment. The pavilion w as designed and built<br />

at a time w hen Canada began its move<br />

from a Franco-English bicultural identity to<br />

a multicultural identity in order to dissolve<br />

the contradictions biculturalism posed.' In<br />

light ofthat pluralism, Studio BBPR's use of<br />

a form associated w ith Canada's First Nations<br />

might seem naive and opportunistic 8<br />

Despite the obvious reference, La w rence<br />

Allow ay w as one of the first commentators<br />

to explicitly compare the Canadian Pavilion<br />

to a w igw am .• There is no documentary<br />

evidence to suggest that the architects<br />

w ere prompted by their Canadian patrons<br />

to adopt or reinterpret the w igw am model<br />

or that they had ever visited Native-Indian<br />

communities in Canada and the United<br />

States of America. Perhaps the architects<br />

w ere able to view the monumental collection<br />

of photographs assembled by<br />

the US photographer Ed w ardS. Curtis.' 0<br />

The efforts of cultural professionals in<br />

Canada and Italy to construct an image<br />

of national identity that w as modern and<br />

indigenous makes the pavilion, despite its<br />

shortcomings as a place to exhibit art, a<br />

site that discloses contradictions embedded<br />

in the contemporary cultures of both<br />

nations, for w hich the fusion of modernity<br />

and the "primitive" promised to w ork as<br />

a solvent.<br />

The w igw am image that BBPR utilized to<br />

construct identity recalls the dw ellings<br />

of some of North America's indigenous<br />

population before European settlement.<br />

By evoking one of Canada's most ancient<br />

dw ellers, the Italian architects (and the<br />

National Gallery Board ofTrustees, w ho ultimately<br />

approved the design) circumvented<br />

the diplomatic tug-of-w ar that w ould have<br />

follow ed a decision favouring either Anglo<br />

or Francophile sources." BBPR sought to<br />

express an "original" Canadian identity<br />

that could be shared by the entire nation.<br />

Despite the pavilion's functional shortcomings,<br />

that pursuit of "authenticity"<br />

reflected the momentum of the Report<br />

4<br />

JSS AC I JSEAC 32 > N·• I > 2007

MICHELANGELO S ABATINO > ANALYSIS I ANALYSE<br />

of the Royal Commission on National<br />

Development in the Arts, Letters and Sciences<br />

(informally known as the Massey<br />

Report), issued in 1951, whose aim was to<br />

free the arts of the country from colonial<br />

subservience 12 (fig. 6) . The recommendations<br />

of the Massey Report led, amongst<br />

other things, to the establishment of the<br />

Canada Council for the Arts, which continues<br />

to play an important role in the<br />

cultural life of the nation.<br />

The Massey Report emerged from a desire<br />

to project a position of cultural independence<br />

for Canada by reducing its reliance<br />

on England, France, and the United States.<br />

The document did not yield immediate<br />

and quantifiable results in terms of architecture<br />

and art, but it stirred debate."<br />

The authors of the report asserted :<br />

A specific problem of architecture in Canada<br />

has bee n t he tendency t owar d imitative<br />

in 1945). Despite<br />

the explicitly collaborative<br />

nature<br />

of the group, archival<br />

materials<br />

and official accounts<br />

attribute<br />

the design to<br />

En rico Peressutti<br />

alone. 15 The impetus<br />

for a Ca -<br />

nadian Pavilion<br />

in Venice came<br />

when the prestige<br />

and fame of<br />

Studio Architetti<br />

BBPR in both<br />

North America<br />

and Europe was<br />

at its height. Of<br />

the three archi-<br />

tects in the firm,<br />

Enrico Peressutti<br />

and derivative st yles of ar chitecture. Th e and Ernesto N.<br />

aut hors of both the special st udies prepared<br />

for us dealt severely w ith t he longst andin g<br />

and widesp r ea d practice of imi t ati ng<br />

inappr opriat ely st yles of past generations<br />

or of other c ou nt r ies w hich have ind eed<br />

solve d t heir ow n ar c hi tectura l problem s<br />

but not necessarily in a manner which can<br />

be suitable at t his t ime and in t his cou ntry<br />

.. I It was drawn to our attent ion t hat t here<br />

is in cr easin g con scious ness of t he nee d in<br />

Ca nada for t he development of a r eg io na l<br />

archi t ect ure adapted to t he landscape and<br />

t he climate and also to t he material typical<br />

of t he area . . It has bee n st ated t o us t hat<br />

a true Canadian architecture must develop<br />

in t hi s way. 14<br />

ITALIAN ARCHITECTS FOR A<br />

CANADIAN PAVILION<br />

The architects of the Studio Architetti BBPR<br />

firm were Lodovico Barbiano di Belgiojoso,<br />

Enrico Peressutti, and Ernesto N. Rogers<br />

(Gian Luigi Banfi, the first Bin BBPR, died<br />

Rogers enjoyed<br />

FIG . 4. INTERIOR, CANADIAN PAVILION, VENI CE.<br />

the greatest international exposure; both<br />

taught at American ivy-league universities<br />

and both were involved with the ClAM<br />

(Congres international d'architecture<br />

moderne). Along with the engineer Pier<br />

Luigi Nervi, Pe ressutti and Rogers were<br />

the most visible Italian architects in North<br />

America and they gained that renown<br />

just as the arts in Canada were undergoing<br />

a "coming of age." In 1955, Harry Orr<br />

McCurry retired as Director of the National<br />

Gallery of Canada in Ottawa, giving<br />

way to charismatic Alan Hepburn Jarvis<br />

(1915-1972), a sculptor, author, art critic,<br />

film producer, and television commentator.16<br />

Although Jarvis resigned in 1959, his<br />

tenure coincided with the planning and<br />

construction of the Canadian Pavilion.<br />

Since the National Gallery was responsible<br />

for promoting the arts in Canada and<br />

abroad, it was the institution's responsibility<br />

to initiate the project. Board of<br />

Trustees minutes show that McCurry had<br />

started to lay the groundwork before the<br />

arrival of Jarvis:<br />

The Director pointed out that as in the fifty<br />

years since t he Biennale di Venezia was fir st<br />

opened in Ve ni ce all the principa l European<br />

countri es as wel l as the United States<br />

and Argent in e have built nat ional fine arts<br />

pavilio ns w ithin t he grounds of the Bi ennale<br />

and as the art of t hese count r ies has in<br />

t hi s way been brought regularly before the<br />

in formed international publi c, the Canadian<br />

Government should em ulate t he initiat ive<br />

of other natio ns in this respect and build a<br />

suit able sma ll pavilion to house Ca nadian ar t<br />

on a site to be donat ed by t he authorit ies<br />

of the Biennale, the cost t o be paid out<br />

of blocked lira available t o t he Canadi an<br />

Government in Italy. The Board fe lt that this<br />

was a matter for furt her investigation and<br />

t hat t he question of whether or not t here was<br />

blo cked lira avai labl e should be looked into-"<br />

JSSAC I JSEAC 32 > N" 1 > 2007<br />

5

M ICHELANGELO SABATINO > ANALYSIS I ANALYSE<br />

~ .. ,,.1 •• ho<br />

... , .. . ~o .. .<br />

._:.,~j,l<br />

· ·~· ... )"''.<br />

•··<br />

:<br />

PC6V<br />

2<br />

;;o•'''\ 1<br />

\,..·•<br />

., ., .,_<br />

~<br />

'<br />

C=========================~ ~<br />

FIG. 5. PLAN, CANADIAN PAVILION.<br />

Donald W. Buchanan (1908-1966), Deputy<br />

Director of the National Gallery under<br />

McCurry and Jarvis, provided continuity<br />

for the project through the change of<br />

leadership. Correspondence reveals that<br />

Buchanan worked behind the scenes on<br />

the pavilion with the Canadian Ambassador<br />

to Italy, Pierre Dupuy.' 8<br />

In a letter dated January 27, 1954, Peressutti<br />

responded to McCurry's inquiry<br />

about costs, which, according to the<br />

latter, were not to exceed $25,000, for<br />

a pavilion measuring approximately 60<br />

x 45 feet. McCurry had begun to think<br />

about engaging the Milanese firm as designer<br />

of the pavilion.' 9 Peressutti visited<br />

Ottawa later that year, likely during one<br />

of his regular visits to North America to<br />

teach at Princeton University, where his<br />

students included Charles Moore and<br />

William Turnbull. 20 Peressutti wrote a<br />

_j '2<br />

letter to Charles Moore in July 1958<br />

(only a month after the opening of the<br />

Canadian Pavilion in Venice) :<br />

Pr es ent architecture is going t hro ugh<br />

a very important period : the dog m a of<br />

functionalism being surpassed is an already<br />

acquired fact, a w ider and more free field<br />

of architectonic expression opens in front<br />

1950s, when the Marshall Plan was lendof<br />

us. We are t hese years. crossing the<br />

gate, architecturally speaking, between t he<br />

anxious to shake off the stigma of fasrecent<br />

past and the next future. Through<br />

cism with a renewed sense of cosmopolithis<br />

gate we must lea d the students and it<br />

is of very great im portance t hat we use in<br />

our di scussions t he r ight tools well defined<br />

J<br />

0<br />

had "just received authorization from<br />

the Government of Canada to proceed<br />

with building a Canadian Pavilion for La<br />

Biennale di Venezia if space is still available."<br />

" It may have been the fact that<br />

the blocked funds-initially earmarked<br />

for scholarships for Canadian students<br />

traveling to Italy-were available only in<br />

lira that prompted Curry and the Board<br />

of Trustees (and later Jarvis) to opt for an<br />

Italian rather than a Canadian architect."<br />

Or this may have been a politically exped i<br />

ent rationale for their open-minded (and<br />

practical) decision to give the job to an<br />

internationally recognized architect who<br />

had a strong local presence in Italy and<br />

could work without a language barrier.<br />

The promotion of Canadian art by the<br />

Massey Report coincided with a new<br />

public presence for the National Gallery<br />

in Canada and abroad. In 1959, one year<br />

after inaugurating the Canadian Pavilion<br />

in Venice, plans for a new building in<br />

Ottawa had been abandoned and the<br />

museum was moved into the uninspired<br />

Lorneofficebuilding. 24 AfterWorldWarll,<br />

the Venice Biennale emerged as the pre-<br />

mier international art venue for Europe.<br />

For a long time, the United States was the<br />

only non-European country with its own<br />

pavilion. Only in 1952 was Canada first<br />

represented at the Biennale, in a small<br />

room in the Italian Pavilion. During the<br />

ing a new stability to Italy, Italians were<br />

tan ism. The rebirth of the Ven ice Biennale<br />

was led by its General Secretary Rodolfo<br />

Pallucchini, a scholar of Venetian Renaisand<br />

w ithout possible misunderstandings. sance art. Under Pallucchini (1948-1956)<br />

Because also t he students must go through<br />

this gate. 21<br />

On December 14, 1955, the newly appointed<br />

Jarvis informed the Biennale<br />

Secretary Rodolfo Pallucchini that he<br />

and subsequently Gian Alberto Deii'Acqua<br />

(1958 -1968), a number of modernist<br />

pavilions were added to the many permanent<br />

historicist ones erected during the<br />

first half of the twentieth century. 25 The<br />

Canadian Pavilion, which would be owned<br />

6<br />

JSSAC I JSEAC 32 > N" 1 > 2007

MICHE LANGELO SABATINO > ANALYSIS I ANALYSE<br />

by Canada, was to be built on land ofthe<br />

City of Venice. It was the twenty-third in<br />

a growing list of buildings designed by<br />

an international coterie of architects.<br />

Among the most notable postwar additions<br />

were Gerrit Rietveld's Dutch Pavilion<br />

(1954), Carlo Scarpa's Venezuelan Pavil <br />

ion (1954), Alvar Aalto's Finnish Pavilion<br />

(1956), and Sverre Fehn's Nordic Pavilion<br />

(1961) . The Canadian Pavilion was one of<br />

the few to be designed by architects who<br />

didn't have the citizenship of the country<br />

they were designing it for. 26 This receptiveness<br />

to modern architecture on the<br />

Biennale grounds is in marked contrast to<br />

the fierce resistance during the mid 1950s<br />

to Frank Lloyd Wright's design for a new<br />

building along the Grand Canal. The Biennale<br />

itself did not include an architecture<br />

section until several decades later, when<br />

Vittorio Gregotti was asked to direct the<br />

first architecture biennale in 1976.<br />

The Studio Architetti BBPR acquired<br />

a reputation as "humanist" architects<br />

who rejected the sterile formalism of the<br />

"international style." They were seen as<br />

creatively engaged with cultural realities<br />

FIG. 7. PERSPECTI VE SKETCH, CANA DIAN PAVILION.<br />

and traditions ("continuity" was the term<br />

Rogers used to refer to the design process)<br />

without falling into historical mimeticism.<br />

In 1955, they designed the acclaimed<br />

Olivetti showroom in New York with the<br />

collaboration of the emigre artist and<br />

sculptor Costantino Nivola (1911-1988).<br />

Stalagmites of green cipollino marble<br />

thrusting up from the floor on wh ich the<br />

typewriters and business machines were<br />

displayed (indoors and outdoors) created<br />

the impression of a primitive yet modern<br />

cave in the heart of ManhattanY Rather<br />

than ce lebrate the machine-aesthetic as<br />

an impersonal and anonymous style, the<br />

architects chose-taking their cues from<br />

the enlightened approach of Olivetti's<br />

promotion of the arts in Italy-to highlight<br />

craftsmanship and human ingenuity.<br />

The architects' involvement with an<br />

addition (never realized) to Ca' Venier,<br />

home of the American art collector Peggy<br />

Guggenheim, introduced them to the<br />

cosmopolitan circles of Venice that Canadians<br />

were eager to join during those<br />

years. BBPR had many commissions for<br />

pavilion design in Italy during the 1950s,<br />

including the American building for the<br />

IX'h Triennale in Milan and the cupola-like<br />

exhibition pavilion in Turin (1953). In 1956<br />

Eric Arthur invited Rogers to serve as a<br />

juror in the international competition for<br />

the new city hall for Toronto 2 8<br />

The reaction against post-and-lintel<br />

"rationalism" that Studio BBPR's evocation<br />

of the wigwam suggests reflected<br />

a preoccupation in postwar Italy with<br />

organic architecture that was paralleled<br />

on Canada's West Coast or in Arizona by<br />

such renegades as the Italian emigre architect<br />

Paolo Soleri. 29 Rationalism, with its<br />

classical underpinnings, was stigmatized<br />

in postwar Italy by its association with<br />

Fa scist architecture during the inter-war<br />

years. A new generation of Italian critics<br />

and historians directed architects towards<br />

more "democratic" forms of expression.<br />

Bruno Zevi (1918-2000) forcefully advocated<br />

that position in his book Towards an<br />

Organic Architecture, published in Italian<br />

in 1945 (and in English in 1950), and his<br />

short-lived journal, Metron. 30 In writing<br />

about the Canadian Pavilion, Zevi characteristically<br />

pointed out how it subverts<br />

the compact and monumental qualities<br />

JSSAC I JSEAC 32 > N ' 1 > 2007

M ICHELANGELO S ABATINO > ANALYSIS I ANALYSE<br />

by Giuseppe Pagano and his "Architettura<br />

rurale ita Iiana" (Italian rural architecture)<br />

exhibition of 1936. 32<br />

FIG . 9. SKETC HES, CANADIAN PAVILION.<br />

The w igwam evoked by the structural<br />

and spatial organization of the pavilion<br />

(as reflected in preparatory sketches) is an<br />

indigenous Canadian dw elling type that<br />

predates European settlement (fig. 7).<br />

Other dwelling types associated w ith Can <br />

ada's First Nations include the lroquoian<br />

long house, the teepee (tipi) of the Plains<br />

Indians, the six and t w o-beam w ood<br />

houses of the West Coa st Nations, and<br />

the snow houses (igloos) of the North-"<br />

In BBPR's interpretation, brick and steel<br />

lent w eight to a semi-permanent building<br />

type that was originally constructed<br />

w ith saplings and tree bark. 34 The Algonquian<br />

wigwam used saplings covered w ith<br />

sheets of bark whereas the teepee employed<br />

poles (peeled pine or cedar) t hat<br />

w ere covered with buffalo skins sewn<br />

together. More significantly, the intimatesized<br />

wigwam is significantly blow n up in<br />

scale by the designers in order to fulfill<br />

the requirements of a fully inhabitable<br />

exhibition space. Studio BBPR 's first schematic<br />

drawings of the pavilion w ere of<br />

t w o octagons of varying sizes linked by<br />

a passageway 35 (fig. 8). The facets of the<br />

octagon recalled the round or oblong<br />

plan of both wigwam and teepee. Sketches<br />

show the architects struggling w ith<br />

of the neighbouring classical English and the spatial and functional implications<br />

German pavilions. 31 For architects w ho of an octagon and circle plan (figs. 9-11).<br />

had not distanced themselves from fascism<br />

in time, the move from classicism and patrons considered the possibility of<br />

There is no evidence that the architects<br />

tow ards an anthropologically oriented a w ood building in the manner of other<br />

"primitive" vernacular offered possibilities<br />

for redemption and "continuity" such as Alvar Aalto's pavilion for Finland<br />

earlier pavilions on the Biennale grounds,<br />

with inter-war interests. The redemptive (1956) and Carlo Scarpa's Galleria del<br />

role of the vernacular in the discourse of Libro d'Arte (1950) 36<br />

postw ar Italian modernism w as evident<br />

in Franco Albini and Giancarlo De Carlo's BBPR's final scheme abandoned the octagon<br />

plan of the initial design for the<br />

" Spontaneous Architecture" exhibition<br />

at the Milan Triennale of 1951, based Archimedes spiral of the nautilus shell.<br />

on the model provided years earlier How ever, since the spiral can be generated<br />

8<br />

I ,JSE AC 32 > N" 1 > 2 007

MICHELANGE LO SAB ANALYSIS I A'IJALVS E<br />

from the o cta gon, its fa ceted presen ce<br />

is fe lt throughout th e pla n and in the<br />

tapered octagonal colum n that supports<br />

t he roof be a m s (fig s. 12-13). Roge rs<br />

and other m embers of t he Stud io BBP R<br />

parti cipated in an important international<br />

conference on De divina proport<br />

ione (divine proportion) held in 19 51 at<br />

the Mi lan Triennale, along side Rudolf<br />

Wittkow er and Sigfried Giedion. 37 leo<br />

Pari si's Hospit alit y Pavili on for the Milan<br />

Triennale of 1954 w as also ba sed upon the<br />

geometry of t he spiral and bea rs a striking<br />

resemblance to the Canadian Pavilion<br />

completed four years later 38 (fig. 14). Movable<br />

w al ls/sc reens reflecting the generative<br />

geometry of the p lan and the layout<br />

of the roof beam s w ere add ed to th e<br />

Venice Pavilion to expand the hanging<br />

surfaces and articulate the inner spa ce<br />

(fig . 15). Yet, the re lativel y lim ited size<br />

of the permanent and movable w all s (as<br />

w ell as t he sloped cei li ngs) reflected la ck<br />

of planning (or f oresight) by the pavilion's<br />

clients and architects. The explosion of<br />

canvas size during the 1960s left many<br />

Canadian curators of the pavilion hard<br />

pre ss ed t o display the paintings of Ja ck<br />

Bu sh and Pau l- Emile Borduas.<br />

FIG. 10. SKETCHES, CANADIAN PAVILI ON.<br />

FIG. 12. VIEW OF COLUMN FRO M INSIDE THE<br />

CANADIAN PAVILI ON.<br />

Sketches of the o ctagon plan show that<br />

Enri co Peress utti con sidered variou s<br />

options. In these draw ings, the iconic image<br />

of a preindustria l semi -permanent<br />

dw elli ng is combined w ith idea l pro <br />

portions; th e "s pontaneou s" quality of<br />

the former competes w ith the ideali sm<br />

of the lat ter. Though lac k ing the mysti <br />

cism of the Canadian pa inter Emil y Carr's<br />

West Coa st " prim itivism, " the pavilion's<br />

embrace of nati ve -Ameri can imagery<br />

reflect s a spirit of rugged vit ality and a<br />

heightened aw areness of text ure similar<br />

t o those perceptible in t he spectacular<br />

Cana dian landscape paintings of the Group<br />

FIG. 11. SK ETCHES, CANADIAN PAVILI ON.<br />

renegade decision to li ve immersed in<br />

FIG. 13. VIEW OF COLUMN FRO M OUTS IDE THE CANADIAN<br />

PAVILI ON.<br />

for the disp lay of art. Like a w igw am,<br />

the Canadian w ilderness so that he might the buil ding does not have exterior w in -<br />

capture the spi rit of th e pla ce on hi s<br />

canvases.<br />

dow s apart f rom narrow ribbon apertures<br />

located just under the roofline. On the<br />

interior, floor-to-ceiling w indows face a<br />

of Seven and asso ciates li ke Tom Thorn- The conflation of the w igw am and the sma ll open-a ir courtyard, drawing indison.<br />

The rugged and eccentric qualities of nautilus shell revea led by Peressutti's many rect light int o a spa ce that is ot herw ise<br />

the Canadian pavilion paral lel Thomson's sketches created an ever-changing space shaded by t w o tall trees located w ithin<br />

r;r,.L1,i_; J.- A ~ > ~-J > ,- 00 9

MICHELANGELO S ABAT INO > ANALYSIS I ANALYSE<br />

clarity of a classical modern temple, BBPR's<br />

feels more like a rustic tree house. Yet the<br />

shortcomings are precisely w hat make the<br />

experience of the space so unique.<br />

FIG. 14. HOSPITALI TY PAVI LIO N, ICO PARISI, MILAN TR IENNALE, 1954.<br />

Although Canada was considered a<br />

young nation in comparison to its European<br />

forebears, it w as given a prestigious<br />

site in the cul -de-sac at the end of the<br />

two main thoroughfares in the Biennale<br />

gardens, between the classically inspired<br />

English and German pavilions and across<br />

from the French . Ironically, Canada's<br />

founding as a new nation in 1867 had<br />

coincided with the political founding of<br />

the Italian nation. Canada was presented<br />

w ith t w o sites for consideration: site A<br />

w as located behind the United States<br />

and Czechoslovakian pavilions; site B<br />

was located between the English and<br />

German pavilions. Jarvis, advised by Peressutti,<br />

chose site 8 39 (fig. 17). In a letter<br />

dated March 23'd, 1956 Peressutti went to<br />

great lengths to explain in his awkward<br />

English why site B was more appropriate.<br />

Having taken photographs and sent<br />

Jarvis and Buchanan the schematic<br />

drawings based upon the octagon plan,<br />

Peressutti listed the follow ing reasons<br />

for choosing site B over site A: "(1) wider<br />

area for the construction, (2) open space<br />

in front of the pavilion along the main<br />

public circulation, (3) wider horizon on<br />

the background of the pavilion looking<br />

~ towards the laguna."<br />

E<br />

!<br />

·~ Although the w igwam evoked a timeless,<br />

FI G. 15. PLAN OF ROOF, CANA DI AN PAVILI ON.<br />

its footprint. One of those trees is incorporated<br />

into the pavilion's floor plan and<br />

is encased in glass (fig. 16). The light well<br />

created by the glass-encased tree evokes<br />

the opening at the apex of the wigwam<br />

traditionally used for release of smoke<br />

generated by the hearth. Sverre Fehn followed<br />

the Canadian Pavilion's lead in his<br />

design of the luminous Northern Pavilion<br />

(representing Finland, Norway, and Sweden),<br />

completed for the Biennale in 1961.<br />

Unlike the vast airy expanse of Fehn's exhibition<br />

space, in w hich the trees are tall and<br />

slender enough to weave gracefully in and<br />

out of the roof structure without any glass<br />

encasements, the integration of the trees<br />

is awkward in the Canadian Pavilion. While<br />

Fehn's pavilion evokes the elegance and<br />

10<br />

JSSAC JSE AC 32 > N 1 > 2007

M ICH ELANGELO SABATINO > ANALYSIS I ANALYSE<br />

---·------···------·----,<br />

fnte Au!onomo "l A BIENNAL!. ~ I Vlllf~ I A ~<br />

ti'OSIZIOtiE.IMTE&tiAZKlNI.U ~-,I. ~TE.<br />

FIG . 16. IN TERIOR VIEW, CAN ADIAN PAVILION, VEN ICE.<br />

serves as its backdrop (fig. 19). Although<br />

Peressutti believed that the shared plaza<br />

in front of the English and German pavilions<br />

would attract visitors to the building,<br />

the pavilion was placed so far back that<br />

many visitors have a hard time finding<br />

its entrance. Despite Pe ressutti's stated<br />

interest in the view toward the laguna<br />

the pavilion actually turns its back to it.<br />

The most welcoming aspect of the pavilion<br />

is the fact that it was constructed on<br />

the ground (thus avoiding the ceremonial<br />

steps used for the classical pavilions).<br />

.,BACINO<br />

£)/<br />

1"~ .· /'1ARC 0<br />

"'B"<br />

. ~<br />

·l,j;"~itj} ,;-1 .:7 · 1.'/PPP "<br />

E<br />

01<br />

~<br />

0<br />

~<br />

~<br />

~<br />

' ~ J<br />

L-------------------------------------~<br />

FIG . 17. PLAN, VEN ICE BIENNALE GARD ENS (SITES A AND B)<br />

Philip Po cock, a friend of Bu chanan,<br />

recounted in an interview that when the<br />

pavilion was under discu ss ion and then<br />

construction, Peressutt i lectured in Ottawa<br />

on the cone-shaped stone trul/i of<br />

southern Italy, much to the dismay of those<br />

w ho were expecting to hear him speak<br />

on avant-garde architecture. In terms of<br />

"primitivism" and modernist architecture,<br />

it is useful to note that the initial version<br />

of the pavilion featured a Brancusi-like<br />

endless co lumn of two elongated modules<br />

in the place of octagonal tapered<br />

co lumn that supports the steel 1-beams<br />

holding the roof planes (fig. 20). Recent<br />

scholarsh ip has demonstrated to what<br />

FIG. 18. EXTERIOR VIEW, DETAI L OF I-BEAM, CANADIA N PAV ILION, VEN ICE.<br />

JSSAC I JSEAC 32 > N• 'I > 2007<br />

11

M ICHELANGELO SABAT INO > ANA LYSIS I ANALYSE<br />

.--------------------·------------·-···-·----·····----<br />

FIG. 19. SITE PLAN, CANADIAN PAVILION.<br />

degree Brancusi's sculpture was indebted<br />

to the folk art of his native Romania 40<br />

Brancusi is just one of many artists w ho<br />

achieved-not unlike major twentiethcentury<br />

architects ranging from Loos to<br />

Le Corbusier-their modernity by looking<br />

with great interest to "timeless" folk<br />

tradition for inspiration.<br />

With the exception of Etienne-Joseph<br />

Gaboury's Church of the Precious Blood<br />

in Manitoba (1967-1968), the romanticized<br />

identity represented in the w igw<br />

am-inspired Canadian Pavilion w ould<br />

be supplanted in the 1960s by a bolder,<br />

less-literal "Canadianess" in the work of<br />

Arthur Erickson and Ron Thorn. Erickson<br />

evoked the sublime expansiveness of the<br />

Western Canadian landscape in his designs<br />

for Simon Fraser University (1963}<br />

and Lethbridge University (1968) 41 Thom<br />

recalled the massive, rugged landscape of<br />

the Canadian Shield with his design for<br />

Trent University (1964). Douglas Cardinal's<br />

Canadian Museum of Civilization (1989} in<br />

Hull builds on these precedents by recalling<br />

rugged rock outcrops. A more recent<br />

attempt at recreating the atmosphere of<br />

a teepee (especially when seen glowing<br />

at night with a blazing hearth) has been<br />

achieved by Brian Mackay Lyons in his<br />

"Ghost House" completed in 1994 (Upper<br />

Kingsburg, Nova Scotia). By combining a<br />

traditional European wood house with<br />

indigenous transparencies, Lyons and<br />

his students achieved a lasting tribute to<br />

Canadian identities in architecture•'<br />

The Massey Report and the Canadian<br />

Pavilion set the precedent for architects<br />

during the late 1950s and early 1960s to<br />

begin to search for "origins" common to<br />

all Canadians•' Parallel w ith these events,<br />

Canada's charismatic Eric Ross Arthur<br />

challenged the architecture profession<br />

to rediscover North-American indigenous<br />

architecture by looking to early "buildings"<br />

and the majesty of cathedral-like<br />

barns 44 Others took his cue and went on<br />

to promote the "quiet dignity" of small<br />

tow ns. 45 As editor of the Royal Architectural<br />

Institute of Canada Journal (RAIC),<br />

Arthur published Ernesto Roger's seminal<br />

essay "Continuity or Crisis" (1958),<br />

in w hich the Italian architect challenged<br />

his peers to reconsider the creative role<br />

that tradition (and not historicism) could<br />

play in modern architecture.' 6 It is hard<br />

not to see how those events laid the intellectual<br />

groundwork for landmarks of<br />

critical regionalism like the Mississauga<br />

City Hall (1987) in which cues from regional<br />

history were subsumed into an<br />

international framework. By transforming<br />

a vernacular model like the barn-not<br />

unlike what BBPR set out to do with the<br />

wigwam for the Canadian Pavilion in Venice-,<br />

Edward Jones and Michael Kirkland<br />

created a lasting civic monument; despite<br />

its urbanity (achieved in part thanks to its<br />

classical underpinnings), the new city hall<br />

recalls the agrarian values of a pastoral<br />

12<br />

J SSAC I ciSEAC :32 > f\J '1 > 2007

MICH ELANG ELO S ABATI NO > ANALYSIS I ANALYSE<br />

landscape forever transformed by more<br />

recent housing at odds with any sense<br />

of place. Not unlike the Mississauga City<br />

Hall, the Venice Pavilion reminds visitors,<br />

almost fifty years after its inauguration,<br />

of Canada's impressive natural environment<br />

and the difficulties involved with<br />

achieving a balance-common to ancient<br />

as well as modern-day dwellersbetween<br />

gentle stewardship ofthe land and<br />

responding to the aggressive demands<br />

of urbanization.<br />

NOTES<br />

1. This article closes a chapter of my life spent<br />

traveling between Italy and Canada . The Social<br />

Sciences and Humanities Research Council of<br />

Canada deserves my gratitude for a doctoral<br />

and a postdoctoral grant that made my studies<br />

on Italian modernism possible. I w ould like<br />

to thank Cyndie Campbell (Head of Archives)<br />

and David Franklin (Deputy Director and Chief<br />

Curator) at the National Gallery of Canada. In<br />

Italy the staff of the Archivio Progetti of the<br />

lstituto Universitario di Architettura di Venezia<br />

(IUAV) was most helpful. A host of Canadian<br />

colleagues deserves collective thanks: George<br />

Baird, Robert Hill, Stephen Otto, Phyllis Lambert,<br />

and Larry Richards. Thanks are in order<br />

for my University of Houston colleagues who<br />

read and commented the essay: Stephen Fox,<br />

John Zemanek, and Bruce Webb.<br />

2. The pavilion opened w ith a retrospective<br />

exhibition of the post-impressionist painter<br />

James Wilson Morrice (1865-1924) and work by<br />

contemporary artists Jacques de Tonnancour<br />

(1917-), Jack Nichols (1921 -), and Anne Kahane<br />

(1924-) . See the exhibition catalogue XXIX Biennale<br />

di Venezia, Venice, La Bi ennale, 1958,<br />

p. 220-224. For an overview of Canada's participation<br />

at the Venice Biennale, see Reesor,<br />

Carol Harrison, 1995, The Chronicles of The<br />

National Gallery of Canada at the Venice Biennale,<br />

Master's thesis, Concordia University,<br />

p. 18-39. Paikowsky, S., 1999, "Constructing an<br />

Identity- The 1952 XXVI Biennale di Venezia<br />

and 'The Projection of Canada Abroad"', The<br />

Journal of Canadian Art History, XX/1-2, 130-<br />

181 . The opening celebrations for the pavilion<br />

w ere captured in the documentary, City Out<br />

of Time, produced by the National Film Board<br />

of Canada in 1958 [Camera operator: Dufaux;<br />

58 -209-ECN-6] .<br />

3. Ban ham, Reyner, 1959, « Neoliberty-The Italian<br />

Retreat f rom Modern Architecture >>, The<br />

Architectural Review, val. 747, p. 231 -235.<br />

4. Significant examples of "renovations" are<br />

Franco Albini's Palazzo Bianco and Rosso in<br />

Genua (1952-1962), Carlo Scarpa's Castellvecchio<br />

in Verona (1954-1967), and the Studio<br />

Architetti BBPR's intervention in the Castello<br />

Sforzesco of Milan (1949-1963) .<br />

5. The pavilion has received only cursory attention<br />

in Canada and abroad: see 1958, >, The Canadian Architect, no. 3,<br />

November. p. 62-64; Buchanan, Donald W.,<br />

1958, « Canada Builds a Pavilion at Venice >>,<br />

Canadian Art, January, p. 29-31; Fenw ick,<br />

Kathleen M., 1958, «The New Canadian Pavilion<br />

at Venice>>, Canadian Art, November,<br />

p. 274-277; 1958, , in Hubert-Jan Henket and Hilde<br />

Heyden (eds.), Back from Utopia: The Challenge<br />

of the Modern Movement, Rotterdam,<br />

010 Publishers, p. 126-137.)<br />

14. Royal Commission Studies: A Selection of<br />

Essays Prepared for the Royal Commission on<br />

National Development in the Arts, Letters and<br />

Sciences, 1949-1951, Ottawa, Edmond Cloutier,<br />

1951, p. 216-221; republished in Simmins,<br />

Geoffrey (ed.), 1992, Documents in Canadian<br />

Architecture, Peterborough, Ontario, Broadview<br />

Press, p. 183-204. Only recently a French<br />

translation of the report has been published<br />

(Ottaw a, National Library of Canada, 1999).<br />

15. See The National Gallery of Canada: Annual<br />

Report of the Board of Trustees for the Fiscal<br />

Year 1958-1959, Ottaw a, The National Gallery<br />

of Canada, 1959, p. 32-36. The summary reads:<br />

"There is no doubt that the Canadian Government<br />

was most fortunate in obtaining the<br />

services of the brilliant young Italian architect,<br />

Enrico Perresutti of Milan, who was persuaded<br />

to take on the assignment of designing the<br />

pavilion and overseeing its construction, for<br />

he has given Canada an exceptionally fine<br />

pavilion w hich he has designed and supervised<br />

to the last detail from the landscaping of its<br />

immediate surroundings to the interior display<br />

panels and stands."<br />

16. Ord, Douglas, 2003, The National Gallery of<br />

Canada : Ideas, Art, Architecture, Montreal<br />

and Kingston, MeGill-Queen's University Press;<br />

Mainprize, Ga rry, 1984, The National Gallery<br />

of Canada: A Hundred Years of Exhibitions,<br />

Ottaw a, The National Gallery of Canada,<br />

originally published in RACAR-Revue d 'art<br />

canadienne I Canadian Art Review, nos. 1-2,<br />

1984; and Sutherland Boggs, Jean, 1971, The<br />

National Gallery of Canada, London, Thames<br />

and Hudson.<br />

JSSAC I JSEAC 32 > N' 1 > 2007<br />

13

MICHELANGELO SABATINO > ANALYSIS I ANALYSE<br />

17. Canadian Pavilion Venice 1953-1968, op. cit.<br />

18. See Donald Buchanan to Harry Orr, August 28,<br />

1954. Canadian Pavilion Venice 1953-1968,<br />

op. cit.<br />

19. Canadian Pavilion Venice 1953-1968, op. cit.<br />

20. Ibid.<br />

21 . Cited in Keim, Kevin, 1996, An Architectural<br />

Life-Memoirs & Memories of Charles W.<br />

Moore, Boston, A Bulfinch Press Book I Little,<br />

Brown and Company, p. 28.<br />

22. Canadian Pavilion Venice 1953-1968, op. cit.<br />

23. That is the ambiguous impression left by a<br />

letter of May 14, 1956, from Alan Jarv is to<br />

Geoffrey Massey, who had solicited future<br />

plans for the pavilion: "Many thanks for your<br />

letter about the Canadian Pavilion in Venice.<br />

In fact this has been arranged through External<br />

Affairs using blocked funds and we have<br />

therefore chosen an Italian architect to do this<br />

job. It is Peressutti of Milan, whom I imagine<br />

you know. We are sorry that we could not use<br />

a Canadian architect for this job." (Canadian<br />

Pavilion Venice 1953-1968, op. cit.)<br />

24. Rybczynski, Witold, 1993, A Place for Art:<br />

The Architecture of the National Gallery of<br />

Canada, Ottawa, National Gallery of Canada.<br />

25. On the history of the Biennale, see: Alloway,<br />

op. cit.; Rizzi, Paolo, and Enzo Di Martino,<br />

1982, Storia della Biennale 1895-1982, Milan,<br />

Electa; and DiMartino, Enzo, 1995, La Biennale<br />

di Venezia-1895-7995-Cento Anni di Arte e<br />

Cultura, Milan, Editoriale Giorgio Mondadori.<br />

26. Mulazzani, op. cit.<br />

27. See Huxtable, Ada Luisa, 1954, «Olivetti's<br />

Lavish Shop >>,Art Digest, Jul y, p. 15; and 1954,<br />

, Architectural<br />

Forum, August, p. 98-103.<br />

28. In the brief biographies compiled by Arthur<br />

for the article announcing the winner of the<br />

Toronto City Hall competition published in the<br />

Journal of the Royal Architectural Institute of<br />

Canada (October 1958), he draws attention<br />

to the fact that "Dr. Rogers' firm is engaged<br />

on the Canadian Pavilion for the 'Biennale<br />

d'Arte,' Venice, 1958."<br />

29. Li scombe, Rhodri Windsor, 1997, The New<br />

Spirit-Modern Architecture in Vancouver,<br />

1938-1963, Cambridge, Mass., MIT Press; Lima,<br />

Antonietta lolanda, 2003, Soleri: Architecture<br />

as Human Ecology, New York, Monacelli Press.<br />

30. Zevi, Bruno, 1945, Verso un'architettura organica,<br />

Turin, Giulio Einaudi; English ed., 1950,<br />

Towards an Organic Architecture, London,<br />

Faber & Faber.<br />

31. Zevi, Bruno, 1958, « Architetture alia Biennale-Arredi<br />

Scarpiani Spaccato BBPR >,<br />

L'architettura- Cronache e storia di architettura,<br />

p. 216; republished in Zevi, Bruno, 1978,<br />

Cronache di architettura-daii'Expo mondiale<br />

di Bruxelles aii'Unesco parigino, Rome and<br />

Bari, Laterza, p. 216.<br />

32. For an overview, see Sabatino, Michelangelo,<br />

2004, « Back to the Drawing Board: Revisiting<br />

the Vernacular Tradition in Italian Modernism >>,<br />

Annali di architettura, no. 16, p. 169-185.<br />

33. For a discussion of the "first buildings" of<br />

Canada, see Kalman, Harold, 2000, A Concise<br />

History of Canadian Architecture, Oxford, Oxford<br />

University Press, p. 1-23.<br />

34. For an overview of indigenous dwellings in<br />

North America, see Nabokov, Peter, and Robert<br />

Easton, 1989, Native American Architecture,<br />

New York, Oxford University Press.<br />

35. Canadian Pavilion Venice 1953-1968, op. cit.<br />

36. That option wou ld also have been more in<br />

keeping with the longstanding Canadian<br />

tradition of building in wood, whether for<br />

log cabins or barns. (See Rempel, John 1. ,<br />

1967 [rev. ed. 1980], Building with Wood and<br />

Other Aspects of Nineteenth-Century Building<br />

in Central Canada. Toronto, University<br />

of Toronto Press .) On the tent in history, see<br />

Hatton, E.M., 1979, The Tent Book, Boston,<br />

Houghton Mifflin Company.<br />

37. See Payne, Alina A., 1994, « Rudolf Wittkower<br />

and Architectural Principles in the Age<br />

of Modernism >>, Journal of the Society of<br />

Architectural Historians, no. 53, September,<br />

p. 322-342. The classic text suggesting the<br />

relationship possible between natural organisms<br />

and architecture is Wentworth Thompson,<br />

D'Arcy, 1917 [2"' ed. 1992], On Growth<br />

and Form, Cambridge, England, Cambridge<br />

University Press. See also Otto, Frei, 1982,<br />

NaWrliche Konstruktionen: Form en und Konstruktionen<br />

in Natur und Technik und Prozesse<br />

ihrer Entstehung, Stuttgart, Deutsche<br />

Verlags-Anstalt (Italian translation: Otto,<br />

Frei, 1984, L'architettura della natura, Milan,<br />

II saggiatore); and Coineau, Yves, and Biruta<br />

Kresling, 1989, Les inventions de Ia nature et<br />

Ia bionique, Hachette, Paris.<br />

38. Peressutti, Belgiojoso, and Rogers were no<br />

doubt familiar with that building, just minutes<br />

from their office and published in 1954 in Casabella-Continuita,<br />

no. 202, August-September,<br />

p. 31-32. (See Gualdoni, Flaminio, 1990, leo Parisi<br />

& Architecture, Modena, Nuova Alfa Editore.)<br />

39. In a memorandum to the Secretary ofthe Treasury<br />

Board, July 26, 1956, Alan Jarvis wrote: "I<br />

have recently returned from Venice where I<br />

have chosen the site in the Biennale grounds<br />

which is being given us for our permanent use<br />

by the Biennale authorities. The National Gallery<br />

of Canada now wishes to obtain permission<br />

to make a contract with the architectural<br />

firm of Belgiojoso, Peressutti and Rogers, via<br />

dei Chiostri 2, Milan, Italy, for the designing of<br />

this small pavilion." (Canadian Pavilion Venice<br />

1953-1968, op. cit.)<br />

40. Balas, Edith, 1987, Brancusi and Rumanian<br />

Folk Traditions, Boulder, East European<br />

Monographs.<br />

41. Steele, Allen (ed.), 1988, The Architecture of<br />

Arthur Erickson, London, Thames and Hudson;<br />

Shapiro, Barbara E. (ed.), 1985, Arthur Erickson:<br />

Selected Projects 1971-1985, New York,<br />

Th e Center.<br />

42. Brian Mackay Lyons, Halifa x, Tuns Press,<br />

1998.<br />

43. See Baird, George, 1982, «Northern Polarities:<br />

Architecture in Canada Since 1950 >>, Okanada,<br />

Ottawa, Th e Canada Council.<br />

44. Arthur, Eric R., 1938, The Early Buildings of<br />

Ontario, Toronto, University of Toronto Press;<br />

Arthur, Eric R., 1926, Small Houses of the<br />

Late 18" and Early 79" Centuries in Ontario,<br />

Toronto, University of Toronto Press; Arthur,<br />

Eric R., and Dudley Witney, 1972, The Barn<br />

A Vanishing Landmark in North America,<br />

Toronto, M.F. Feheley Arts. On Arthur, see<br />

my 2001, «Eric Arthur: Practical Visions>>,<br />

Journal of the Society for the Study of Architecture<br />

in Canada, vol. 26, nos. 1-2, December<br />

p. 33-42.<br />

45. The phrase "quiet dignity" is taken from<br />

Greenhill, Ralph, Ken Macpherson, and Douglas<br />

Richardson, 1974, Ontario Towns, Toronto,<br />

Oberon.<br />

46. Rogers, Ernesto N., 1958, «Continuity or<br />

Crisis? >>, Journal of the Royal Architectural<br />

Institute of Canada, May, p. 188-189 (originally<br />

published in Casabel/a-Continuita,<br />

April-May 1957).<br />

14<br />

JSSAC I JSEAC 32 > N' 1 > 2007

ANALYSIS I ANALYSE<br />

LA CREATION D'UNE PETITE ARMENIE OU LES<br />

MULTIPLES USAGES D'UN SOUS-SOL AU QUEBEC<br />

MARIE-BLANCHE FOU RCAOE est docteure en<br />

ethnologie. Sa these. recemment soutenue,<br />

>MARIE-BLANCHE FDURCADE<br />

portait sur le role du patrimoine domestique de<br />

Ia communaute armenienne residant au Quebec<br />

dans ]'expression d'une identite en diaspora.<br />

Ses interets de rechel'che ont pour objet Ia<br />

culture materielle des migrants, Ia museologie<br />

du deracinement et les expressions identitai1·es<br />

diaspo1·iques . Elle occupe actuellement le poste<br />

de coordonnatl'ice a l'lnstitut du patrimoine<br />

a I'UQAM.<br />

Dans l'ouvrage Habiter, reve, image,<br />

projet, Jacques Pezeu-Massabuau<br />

commence son premier chapitre par Ia<br />

description d'une maison. II dit ainsi :<br />

Sa forme et sa couleur ne Ia distinguent<br />

guere des maisons vo isines. Elle ne paralt<br />

a l'etranger ni mains avenante ni plu s desirable<br />

mais s'insere dans l'anonymat des<br />

fagades proches, que le temps a acheve<br />

de fondre dans l'harmonieux contrepoint de<br />

ces parois I .. I Mais elle a pour vous une<br />

evidence qui leur fait defaut : ell e seule vous<br />

est intimement connue et vous attend. En<br />

elle seule vous reconnaissez un refuge I .. I<br />

II me su ffit de pousser une de ces partes<br />

pour retrouver un monde familier ce que je<br />

considere mien et qui ne revele que moi 1 .<br />

Le sentiment d'intimite et d'harmonie<br />

entre les habitats et les habitants decrit<br />

par Jacques Pezeu-Massabuau releve<br />

d'une observation commune des que<br />

l'on interroge quiconque possedant un<br />

logement.<br />

Ill. 1. SOUS-SOL DES PARENTS DE HAS MIG. LA BIBLIOTHEQUE ACCUEILLE DES LIVRES DE COLLECTIONS, DES SOUVENIRS<br />

D'ARMENIE ET QUELQUES BIBELOTS PRODUITS EN DIASPORA. I MARIE-BLANCHE FOURCADE<br />

II y a cependant des situations ou Ia relation<br />

entre individu et espace domestique<br />

s'exacerbe considerablement. Tel<br />

est le cas de Ia migration ou de l'exil<br />

qui provoque l'abandon d'un espace a<br />

soi et d'objets qui constituent le quotidien.<br />

Dans le nouveau pays d'accueil,<br />

les migrants doivent se reconstruire un<br />

espace de reperes dans lequel ils pourrant<br />

s'installer et reinstaurer une temporalite<br />

fracturee par les deplacements. La<br />

maison est un refuge contre l'exterieur.<br />

Cet exterieur peut etre menac;ant par<br />

son lot d'agressions et de problemes,<br />

mais il demande surtout d'abandonner<br />

sur le seuil de Ia porte une partie de sa<br />

JSSAC I JSEAC 32 > N" 1 > 2007 > 1 5 -20<br />

15

M ARIE-BLANCHE FDURCADE > ANALYSIS I ANALYSE<br />

specificite : sa langue, ses habitudes ainsi<br />

que ses reperes au profit d'un collectif. Le<br />

refuge n'est done pas veritablement contre<br />

l'autre, mais pour soi, afin de pouvoir,<br />

a l'abri des regards, conserver son identite<br />

ainsi que les valeurs qui y sont attachees<br />

et cela, tout en s'adaptant au x normes<br />

du pays d'accueil. Pour chacun, done, le<br />

foyer familial offre une liberte d'action<br />

considerable dans les choix culturels et<br />

personnels; il apporte aussi un sentiment<br />

de force rattache a l'unite du groupe qui<br />

efface une part de Ia vulnerabilite liee<br />

a l'etat diasporique. En somme, il s'agit<br />

d'un lieu ou se re-enraciner a moyen ou<br />

a long terme.<br />

Lors de mes recherches doctorales sur Ia<br />

communaute armenienne residant a Montreal<br />

eta Quebec, je me suis interessee a<br />

l'investissement de l'espace domestique<br />

par les migrants et, plus precisement,<br />

au role de Ia culture materielle domestique-<br />

que j 'ai finalement nommee patrimoine-<br />

dans l'enonciation d'une identite<br />

diasporique. Pour ce faire, j'ai effectue<br />

dix-neuf entretiens dans Ia communaute<br />

armenienne de Montreal et de Quebec,<br />

aupres de onze migrants arrives des pays<br />

du Moyen-Orient, de quatre autres venus<br />

d'Armenie et enfin de quatre jeunes nes<br />

au Canada. Dans chacun des logements,<br />

j'ai suivi Ia visite guidee menee par les<br />

proprietaires a travers les differentes<br />

pieces afin de voir, par le biais des<br />

amenagements, comment les individus<br />

s'appropriaient les lieux et comment ils<br />

exprimaient leur culture ou leur appartenance<br />

armenienne. La comprehension<br />

des espaces de vie s'est principalement<br />

appuyee sur le comportement des informateurs<br />

au cours des entretiens. Les visites<br />

des interieurs constituent, en effet,<br />

une situation d'hospitalite exemplaire au<br />

cours de laquelle les occupants se doivent<br />

de delimiter leur territoire face a I'Autre.<br />

L'ordre des pieces parcourues, les endroits<br />

valorises et oublies, Ia decoration des<br />

ILL. 2. SO US -SOL DE VI CHEN. LE MANTEAU DE CHEMIN PERMET D'EXPOSER DE NOMBREUX OBJETS<br />

<strong>CANADA</strong> OU RA PPORTES PAR LES ENFANTS DE LA MAISON. I MARIE-BLANCHE FOURCAOE<br />

lieux et les choix semantiques accordes a<br />

Ia description des differents endroits, tels<br />

sont les indices qui ont permis le dechiffrage<br />

d'une pratique quotidienne de Ia<br />

maison et d'une relation particuliere aux<br />

objets. L'exploration de !'habitat nous fait<br />

progressivement traverser les sas d'intimite<br />

qui, un a un, nous menent au plus<br />

pres des individus.<br />

Parmi toutes les pieces de Ia maison, le<br />

sous-sol est apparu des plus interessants<br />

et ce, a plusieurs egards. D'abord parce<br />

qu'il etait l'objet, chez certains informateurs,<br />

d'un investissement identitaire<br />

distinct des autres pieces; ensuite parce<br />

que tout en s'inscrivant dans une pratique<br />

courante, depuis les annees 1960' ,<br />

d'amenagement au Quebec liee a !'architecture<br />

du bungalow, les migrants en<br />

ont fait un espace a part entiere en le<br />

transformant a leur maniere.<br />

LE SOUS-SOL COMME<br />

LIEU D'INTIMITE<br />

Lors des entretiens, le sous-sol, pour les huit<br />

informateurs qui en possedent un, fut Ia<br />

derniere piece visitee, du fait de sa localisation,<br />

mais aussi de son contenu. Avant me me<br />

de savoir ce qu'il renferme, le discours des<br />

repondants laisse entendre par les phrases<br />

du type : « Vous verrez tout a l'heure en<br />

bas )) que l'espace est, a differents titres,<br />

une de de comprehension incontournable<br />

de l'univers dont on entreprend !'exploration.<br />

Au plus pres des assises de Ia maison,<br />

le sous-sol est un endroit retire et protege<br />

du reste du monde. Menagee tel un tresor,<br />

l'espace est ainsi decouvert sous l'angle<br />

d'une intimite cachee ou, tout du moins,<br />

soustraite au regard des autres.<br />

L'amenagement du sous-sol permet en<br />

effet a chaque famille de creer, dans les<br />

16<br />

JSSAC i JSEAC 32 > N" 1 > 2007

M ARIE -BLAN CHE FOURCADE > ANALYSIS I ANALYSE<br />

ou l'on cache les objets les plus intimes,<br />

mais aussi un lieu de mise en valeur ou<br />

certains biens et souvenirs sont exposes a<br />

Ia maniere d'un musee personnel.<br />

LE SOUS-SOL COMME SALON<br />

UN E ORGANI SATION OR IENTALE QUI RENVOIE AUX<br />

MAISONS ANTERIEURES AU LI BAN. I MARIE-BLANCHE FOURCADE<br />

fondations de son habitation, un lieu de ou pour Ia retraite solitaire. Ainsi, Ia piece<br />

vie complementaire qui varie en fonction<br />

des interets et des besoins de cha<br />

des occupants qui trouve normalement sa<br />

assume une part de l'intimite quotidienne<br />

cun : > 3 . Qu'il soit une aire visiteurs. Certains ont ajoute un bureau<br />

de rangement ou de loisirs, le sous-sol au salon ou ont totalement converti le<br />

demeure l'objet d'un usage aleatoire qui lieu en un bureau et une bibliotheque.<br />

prend cependant toujours appui sur sa II s'agit alors davantage d'un territoire<br />

double qualite d'etre a Ia fois separe du individuel, pour travailler ou pour etre<br />

reste de !'habitat tout en faisant partie au calme. Le fait d'etre partiellement<br />

integrante de Ia maison par les activites coupe du monde en facilite l'usage. Le s<br />

qui s'y deroulent. Malgre Ia diversite des rangements restent quant a eux essentiels<br />

puisque Ia piece remplace d'une<br />

endroits visites, deux tendances se dessinent<br />

parmi les personnes interrogees, soit certaine maniere le role de Ia cave dont<br />

Ia transformation de Ia salle en second Ia fonction est d'accueillir tousles biens<br />

salon ou en bureau. Sont invariablement temporairement inactifs de Ia maison :<br />