CANADA - SEXTONdigital

CANADA - SEXTONdigital

CANADA - SEXTONdigital

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

JOURNAL OF THE SOCIETY FOR THE STUDY OF I JOURNAL DE LA SOCIETE POUR L'ETUDE DE L'<br />

ARCHITECTURE!~<br />

<strong>CANADA</strong><br />

VOL. 30 > N' 1 > 2005

THE SOCIETY FOR THE STUDY OF ARCHITECTURE IN <strong>CANADA</strong> is a learned society<br />

devoted to the examination of the role of the built environment in Canadian society. Its membership includes<br />

structural and landscape architects, architectural historians and planners, sociologists, ethnologists, and<br />

specialists in such fields as heritage conservation and landscape history. Founded in 1974, the Society is currently<br />

the sole national society whose focus of interest is Canada's built environment in all of its manifestations.<br />

The Journal of the Society for the Study of Architecture in Canada, published twice a year, is a refereed journal.<br />

Membership fees, including subscription to the Journal, are payable at the following rates: Student, $30;<br />

lndividual,$50; Organization I Corporation, $75; Patron, $20 (plus a donation of not less than $100).<br />

Institutional subscription: $75.<br />

There is a surcharge of $5 for all foreign memberships. Contributions over and above membership fees are welcome,<br />

and are tax-deductible. Please make your cheque or money order payable to the :<br />

SSAC > Box 2302, Station 0, Ottawa, Ontario, K1P 5W5<br />

LA SOCIETE POUR L'ETUDE DE L'ARCHITECTURE AU <strong>CANADA</strong> est une societe savante qui se<br />

consacre a l'etude du role de l'environnement bati dans Ia societe canadienne. Ses membres sont architectes,<br />

architectes paysagistes, historiens de !'architecture et de l'urbanisme, urbanistes, sociologues, ethnologues<br />

ou specialistes du patrimoine et de l'histoire du paysage. Fondee en 1974, Ia Societe est presentement Ia seule<br />

association nationale preoccupee par l'environnement bati du Canada sous toutes ses formes.<br />

Le Journal de Ia Societe pour /'etude de /'architecture au Canada, publie deux fois par annee, est une revue dont les<br />

articles sont evalues par un co mite de lecture.<br />

La cotisation annuelle, qui comprend l'abonnement au Journal, est Ia suivante : etudiant, 30$; individuel, 50$;<br />

organisation I societe, 75$; bienfaiteur, 20$ (plus un don d'au moins 100$).<br />

Abonnement institutionnel: 75$.<br />

Un supplement de 5$ est demande pour les abonnements etrangers. Les contributions depassant l'abonnement<br />

annuel sont bienvenues et deductibles d'impot. Veuillez s.v.p. envoyer un cheque ou un mandat postal a Ia :<br />

StAC > Box 2302, Station 0, Ottawa, Ontario, K1P 5W5<br />

www.canada-architecture.org<br />

The Journal of the Society for the Study of Architecture in Canada is produced<br />

with the assistance of the Social Sciences and Humanities Research<br />

Council of Canada and the Canada Research Chair on Urban Heritage.<br />

Le Journal de Ia Societe pour /'etude de /'architecture au Canada est publie<br />

avec I' aide du Conseil de recherches en sciences humaines du Canada et de<br />

Ia Chaire de recherche du Canada en patrimoine urbain.<br />

Publication Mail40739147 > PAP Registration No. 10709<br />

We acknowledge the financial assistance of the Government of Canada,<br />

through the Publications Assistance Program (PAP), toward our mailing costs.<br />

ISSN 1486-0872<br />

(supersedes I remplace ISSN 0228·0744)<br />

EDITING, PROOFREADING, TRANSLATION I REVISION LINGUISTIQUE, TR ADUCTION<br />

MICHELINE GIROUX-AUBIN<br />

ASSISTANT ED ITOR IADJOINTE A LA REDACTION<br />

ISABELLE CARON<br />

GRAPHIC DESIGN I CONCEPTION GRAPH IQUE<br />

MARIKE PARADIS<br />

PRINTING I IMPRESSION<br />

K2 IMPRESSIONS, QUEBEC<br />

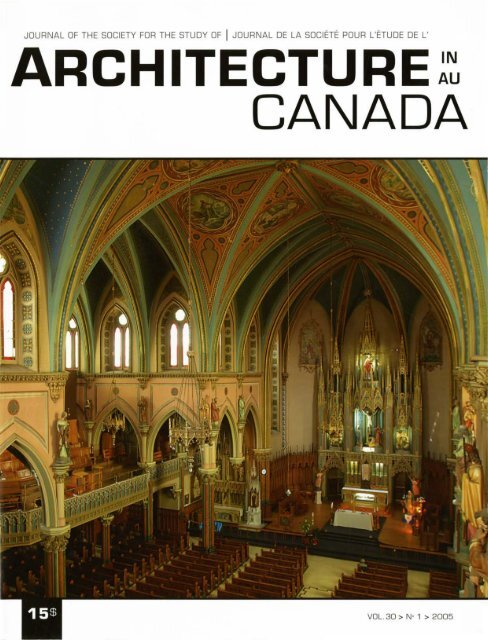

COVER ICOUVERTURE<br />

Montreal. lnterieur de l'eglise Saint-Edouard.<br />

(PHOTO LUC NOPPEN)<br />

PAGE MAKE-UP I MISE EN PAGES<br />

B GRAPHISTES<br />

JOURNAL EDITOR I REOACTEUR DU JOURNAL<br />

LUC NOPPEN<br />

Chaire de recherche du Canada en patrimoine urbain<br />

Etudes urbaines et touristiques,<br />

Ecole des sciences de Ia gestion<br />

Universite du Quebec a Montreal<br />

CP 8888. succ. centre-ville<br />

Montreal, (QC) H3C 3P8<br />

(514) 987-3000 x-25621 I : (514) 987-7827<br />

e : noppen.luc@uqam.ca<br />

WEB SITE I SITE WEB<br />

LANA STEWART<br />

Lana Stewart<br />

Parks Canada<br />

25, Eddy Street, 5th floor<br />

Gatineau, QC K1A OMS<br />

(819) 997-6098<br />

e : lana.stewart@pc.gc.ca<br />

ED ITOR Of NEWS & VIEWS I<br />

REDACTRICE OE NOUVELLES ET COUPS D'CEIL<br />

HEATHER BRETZ<br />

CPV Group Architects & Engineers Ltd.<br />

Calgary, Alberta<br />

e : HeatherB@cpvgroup.com<br />

PRESIDENT I PRES I DENTE<br />

PIERRE DU PREY<br />

Department of Art<br />

Ontario Hall<br />

Queen 's University<br />

Kingston, ON KZL 3N6<br />

(613) 533-61661 I: (613) 533-6891<br />

e: pduprey@post.queensu.ca<br />

VICE-PRESIDENTS I VICE-PRESIDENTS<br />

ANDREW WALDRON<br />

Architectural Historian, National Historic Sites Directorate<br />

Parks Canada<br />

5"' floor, 25 Eddy Street<br />

Hull, QC K1A OMS<br />

(819) 953·5587 If: (819) 953-4909<br />

e : andrew.waldron@pc.gc.ca<br />

LUCIE K. MORISSET<br />

Etudes urbaines et touristiques<br />

Ecole des sceinces de Ia gestion<br />

Universite du Quebec a Montreal<br />

C.P. 8888, succ. Centre-ville<br />

Montreal, QC H3C 3P8<br />

(514) 987-3000 X 45851 I : (514) 987-7827<br />

e : morisset.lucie@uqam.ca<br />

TR EASURER I TRESORIER<br />

JULIE HARRIS<br />

Julie Harris<br />

342, Maclaren St.<br />

Ottawa, ON K2P OM6<br />

e : jharris@contentworks.ca<br />

SECRETARY I SECRE TAIRE<br />

MARIE-FRANCE BISSON<br />

Ecole de design, UQAM<br />

Case postale 8888, succursale "Centre-ville»<br />

Montreal (Quebec)<br />

H3C 3P8<br />

(514) 987 3000 # 3866<br />

e: docomomo@er.uqam.ca<br />

PROVINCIAL REPRESENTATIVES I<br />

REPRESENTANTS PROVINCIAUX<br />

GEORGE CHALKER<br />

Heritage foundation of Newfoundland and Labrador<br />

P.O. Box 5171<br />

St. John's, Nf AlC SVS<br />

(709) 739-1892 1 I: (709) 739-5413<br />

e: george@heritagefoundation.ca<br />

TERRENCE SMITH LAMOTHE<br />

193S Vernon<br />

Halifax, NS B3H 3N8<br />

(902) 42S-0101<br />

THOMAS HORROCKS<br />

ADI Limited<br />

1133 Regent Street. Suite 300<br />

fredericton, NB E3B 3Z2<br />

(506) 452-9000 I I: (906) 452-7303<br />

e · thd @adi.ca I horto@reg2.health .nb.ca<br />

CLAUDINE DEOM<br />

2078, avenue Claremont<br />

Montreal, QC H3Z 2P8<br />

I I I: (514) 488-4071<br />

e : cdeom@supernet.ca<br />

SHARON VATTAY<br />

11 Elm Avenue, Apt#322<br />

Toronto, Ontario M4W 1N2<br />

(416) 964-723S<br />

svattay@chass.utoronto.ca<br />

TERRENCE J. SINCLAIR<br />

Heritage Branch<br />

Saskatchewan Department of Municipal Affairs,<br />

Culture and Housing<br />

430·1855 Victoria Avenue<br />

Regina, SK S4P 3V7<br />

(306) 787-5777 I I : (306) 787-0069<br />

e: tsinclair@mach.gov.sk.ca<br />

L. FREDERICK VALENTINE<br />

CPV Group Architects & Engineers ltd.<br />

Suite 500 110-12th Avenue SW<br />

Calgary, AB T2R OG7<br />

(403) 262-5511 I I : (403) 262-5519<br />

e : fval@cpv-architecture.com<br />

DANIEL MILLETTE<br />

511-55 Water Street<br />

Vancouver, BC V68 1 A 1<br />

t I I: (604) 687-4907<br />

e : lucubratio@yahoo.com<br />

KAY HAN NADJI<br />

126 Niven Dr.<br />

Yellowknife, NT X1 A 3W8<br />

I I I : (867) 920-6331<br />

e : kayhan_nadji@gov.nt.ca<br />

SHELLEY BRUCE<br />

25 forks Market Road# 401<br />

Winnipeg, MB R3C 4S8<br />

(204) 983-2221

CONTENTS I TABLE DES MATU~RES<br />

JOURN AL OF THE SOCIETY FOR THE STUDY OF I JOU RNAL DE LA SOCIETE POUR L'ETUDE DE L'<br />

ARCHITECTURE~~<br />

<strong>CANADA</strong><br />

ANALYSES I ANALYSES<br />

ESSAIS I ESSAYS<br />

RAPPORT I REPORT<br />

COMPTE-RENDU I REVIEW<br />

> LUC NOPPEN<br />

Presentation I Presentation<br />

> SOPHIE RIOUX-HEBERT<br />

Un patrimoine religieu x en devenir<br />

les eglises de !'arrondissement Rosemont<br />

La Petite-Patrie a M o ntreal<br />

> PETER COFFMAN<br />

St. Anne's Anglican Church and its Patron<br />

> RoBERT McGEACHY<br />

Polson Park and Calvin Pa rk, 1954-1962: Two<br />

Land Assembly Subdivisions in Kingston,<br />

Ontario<br />

> COLIN RIPLEY<br />

Emptiness and Landscape: National Identity in<br />

Canada's Centennial Projects<br />

> MELANIE BOUCHER<br />

Lo rsque les artistes e xposent dans les<br />

eglises. Les ca s de Carl Bouchard et de Laura<br />

Vickerson<br />

> KATE MACFARLANE<br />

Hangar No. 1 National Historic Site, Brandon<br />

Municipal Airport, Brandon, Manitoba<br />

> YONA JEBRAK<br />

De Ia Ruffiniere du Prey (2004).<br />

Ah Wilderness! Resort Architecture in the<br />

Thousand Islands.<br />

2<br />

3<br />

15<br />

25<br />

37<br />

47<br />

53<br />

61<br />

VOL. 30 > N' 1 > 2005

PRESENTATION I PRESENTATION<br />

Ce numero de Ia revue de Ia Societe pour !'etude de<br />

!'architecture au Canada marque le 30e anniversaire de sa<br />

parution. Du feuillet d'information qu'elle etait, Ia revue s'est<br />

au fil des ans metamorphosee en une veritable revue scientifique.<br />

Sa presentation graphique a connu des transformations, son<br />

contenu s'est enrichi de collaborations plus nombreuses- plus<br />

variees, aussi. Mais Ia revue cherche toujours, comme c'etait le<br />

cas lors de sa fondation, a donner une place enviable aux jeunes<br />

chercheurs.<br />

Pour souligner l'anniversaire, nous avons adopte une maquette<br />

graphique nouvelle- a Ia fois pour Ia couverture et pour les<br />

pages interieures- qui epouse les contours actuels de nos sensi <br />

bilites esthetiques changeantes. Marike Paradis, jeune graphiste<br />

de talent, fralchement dipl6mee de !'Ecole superieure d'arts<br />

appliques Estienne a Paris, nous a soumis plusieurs projets; nous<br />

vous proposons celui que nous avons retenu dans ce numero 1<br />

du volume 30 d'Architecture Canada .<br />

Lors de l'assemblee generale de Ia Societe, a Lethbridge, il a aussi<br />

ete decide de formaliser une pratique mise en ceuvre depuis<br />

quelques annees deja : Ia revue, desormais, est publiee deux<br />

fois l'an. Nous aurons done a Ia fin du printemps le numero<br />

1 et, a Ia fin de l'automne, le numero 2, chaque fois avec un<br />

nombre de pages equivalent a deux livraisons de l'ancienne<br />

edition trimestrielle.<br />

Notre revue sera aussi en vente au numero (15 $, plus les frais<br />

d'envoi s'il y a lieu) et offerte par le biais d'un abonnement institutionnel<br />

(75 $ par an, incluant les frais d'envoi). La cotisation<br />

a Ia Societe pour !'etude de !'architecture au Canada, qui pour sa<br />

part continue d'inclure l'abonnement a Ia revue, pourra dorenavant<br />

etre souscrite de fa~on triannuelle. Enfin, abonnements et<br />

cotisations seront renouvelables a leur terme et non plus a une<br />

date fixe a chaque an . En esperant que ces modifications plairont<br />

a notre lectorat, que nous souhaitons toujours plus vaste, nous<br />

proposons dans ce numero des articles issus de quelques-unes<br />

des ass·emblees annuelles passees, mais aussi des propositions<br />

soumises par de jeunes chercheurs qui, sans necessairement avoir<br />

participe aces assemblees, ont souhaite contribuer a Ia revue et<br />

vu leurs essais reconnus par les pairs.<br />

This issue marks the 30th anniversary edition of Architecture<br />

Canada, the journal of the Society for the Study of Architecture<br />

in Canada . With time, from its humble beginnings as<br />

an information leaflet, the magazine turned into a true scientific<br />

publication- its graphic grid was modified, and its content<br />

enriched thanks to more numerous, and varied, contributions.<br />

But, as was the case when it was founded, it still strives to lend<br />

enviable exposure to young researchers.<br />

To honour this milestone, we adopted a new look- both inside<br />

and out- which more accurately embodies the current outlines of<br />

our changing aesthetic sensibilities. To this end, Marike Paradis,<br />

a talented young graphic artist fresh out from Ecole superieure<br />

d'arts appliques Estienne in Paris, submitted a number of<br />

projects. It is a pleasure to introduce the one we retained with<br />

this first issue of volume 30 of Architecture Canada.<br />

During the general assembly of the Society held in Lethbridge,<br />

a decision was also made to officialize a practice which has<br />

already been implemented unofficially for a few years- the<br />

magazine is now published twice a year. Issue no. 1 will therefore<br />

be published at the end of spring and issue no. 2 at the end<br />

of fall, with twice the number of pages the previous quarterly<br />

editions held.<br />

Our magazine will also be sold on a per-issue basis ($15, plus applicable<br />

postage, if required) and available through corporate<br />

subscriptions ($75 per year, including shipping). From now on,<br />

membership fees to the Society for the Study of Architecture in<br />

Canada, which will continue to include a magazine subscription,<br />

can now be paid in three instalments. Finally, subscriptions and<br />

fees will be renewable upon term instead of on a fixed date<br />

each year. Hoping these changes will meet the expectations of<br />

our readers, whose numbers we always enjoy to see growing,<br />

we propose an issue filled with articles related to some of the<br />

past annual meeting topics, but also to proposals submitted by<br />

young researchers who, without necessarily having attended<br />

these meetings, wished to contribute to the magazine and see<br />

their efforts recognized by their peers.<br />

> LUC NOPPEN<br />

> LUC NOPPEN<br />

2

ANALYSIS I ANALYSE<br />

UN PATRIMOINE RELIGIEUX EN DEVENIR:<br />

LES EGLISES DE IJ\RRONDISSEMENT<br />

ROSEMONT-LA PETITE-PATRIE A MONTREAL 1<br />

SOPHIE RIOUX-HEBERT complete un rnemowe<br />

de maitr-rse en geogr-aph re a I'UQAM sur<br />

>SOPHIE RIOUX-HEBERT<br />

les fonctrons geo-rdentrtawes des eglrses de<br />

quartrer. En septembre 2005 el le entreprend<br />

des etudes doctorales dans le programme<br />

con1ornt en etudes urbarnes [UOAM/INRS ]<br />

Elle est assocree a Ia Charre de r-echer-che du<br />

Canada en pacr'llllOrne urbarn.<br />

Le Quebec, comme plusieurs autres<br />

regions du monde occidental, est aux<br />

prises avec un probleme d'amenagement<br />

des plus complexes en ce qui concerne<br />

les lieux de cu lte desaffectes ou en voie<br />

de l'etre. En effet, Ia diminution de Ia<br />

pratique religieuse, jumelee a !'augmentation<br />

des couts d'entretien des eglises et<br />

au manque de releve sacerdotale oblige<br />

les dioceses, tant catholiques que protestants,<br />

a fusionner eta eliminer des<br />

paroisses dans le but de consolider leurs<br />

avoirs et leurs activites' . Ces dioceses procedent<br />

ensuite a Ia vente des lieux de culte<br />

excedentaires qui, si le transfert a une<br />

autre communaute religieuse se revele<br />

impossible, sont reconvertis a d'autres<br />

usages ou encore demolis.<br />

Cette tendance se remarque surtout dans<br />

les quartiers centraux des principales vi lies<br />

quebecoises, attendu que leur population,<br />

plus importante, y a genere un plus grand<br />

nombre de lieux de culte. Par contre, les<br />

residants de ces quartiers s'opposent frequemment<br />

a Ia liquidation de leurs eglises,<br />

alleguant que ces biHiments font partie<br />

du patrimoine collectif. Ce conflit d'usage<br />

interpelle !'administration municipale qui<br />

s'efforce de preserver les batiments religieux<br />

les plus significatifs a l'echelle du<br />

quartier. Toutefois, ce qui est significatif<br />

pour les experts en patrimoine et les<br />

autorites municipales ne l'est peut-etre<br />

pas pour les residants.<br />

Un tel contexte souleve plusieurs questions<br />

:Comment les residants d'un quartier<br />

procedent-ils pour determiner Ia valeur<br />

relative de leurs eg lises? Temoignentils<br />

d'une certaine conscientisation dans<br />

leurs choix ou plut6t d 'un attachement<br />

lie a l'usage et a Ia connaissance? Se re <br />

presentent-ils les eglises comme des lieux<br />

JSSAC I JSEAC 30 > N 1 > 2005 > 5-16<br />

3

S OPH IE RIOUX-H EBERT > ANALYSIS I ANALYSE<br />

voues principalement au culte ou comme<br />

des lieux patrimoniaux qui possedent des<br />

valeurs historiques et artistiques ?<br />

A partir de l'exemple de !'arrondissement<br />

Rosemont-La Petite-Patrie a Montreal, le<br />

present article examine les representations<br />

que les residants se font de leurs eglises de<br />

quartier afin de decouvrir si ces representations<br />

temoignent de !'emergence d'une<br />

conscience patrimoniale.<br />

LES REPRESENTATIONS<br />

COLLECTIVES DES EGLISES, UNE<br />

PERSPECTIVE PEU ETUDIEE<br />

Un rapide survol de Ia litterature concernant<br />

les lieux de culte pe rmet de constater<br />

Ia pauvrete de Ia recherche scientifique sur<br />

les representations collectives des eglises<br />

de quartier dans un contexte de secularisation.<br />

La geographie de Ia religion, champ<br />

disciplinaire ou l'on pourrait s'attendre a<br />

trouver ce type d'etude, ne genere que<br />

peu de recherches en ce sens 3 . II existe<br />

bien deux etudes geographiques datant<br />

des annees 1980 qui examinent le recyclage<br />

des eglises rurales du Minnesota et<br />

du Manitoba en lien avec les represen <br />

tations identitaires qu'en possedent les<br />

families qui habitent a proximite•. Ces<br />

etudes concluent que les residants considerent<br />

toujours leurs eglises, malgre leur<br />

desaffectation, comme des batiments<br />

signifiants pour des raisons relig ieuse,<br />

historique et culturelle, mais surtout<br />

pa rce qu'ils entretiennent avec celles-ci<br />

des liens affectifs forts developpes sur<br />

plusieurs generations 5 .<br />

De !'autre cote de !'ocean, en France de<br />

!'Ouest, des geographes ont etudie !'impact<br />

des reamenagements paroissiaux sur<br />

les representations et les comportements<br />

religieux de divers groupes sociaux sans<br />

toutefois examiner les rapports possiblement<br />

affectifs et identitaires que ces<br />

groupes entretiennent avec leurs lieux<br />

de culte•.<br />

ILL. 1. MONTREAL ET L'ARRONDISSEME NT ROS EMO NT·LA PETITE·PATR IE<br />

Au Quebec, les etudes qui explorent le role<br />

des eglises dans Ia societe quebecoise ont<br />

emane principalement d'historiens, d'architectes<br />

et d'urbanistes. Toutefois, malgre<br />

le fait que le patrimoine religieux suscite<br />

depuis quelques annees un interet de plus<br />

en plus marque de Ia part des medias et<br />

de Ia population, comme en temoigne<br />

le nombre d'emissions de television et<br />

d'articles de journaux qui lui sont reserves,<br />

les etudes scientifiques qui abordent le<br />

probleme de Ia conservation des lieux de<br />

culte demeurent peu nombreuses. Au sein<br />

de ce mince corpus, nous n'avons trouve<br />

aucune etude scientifique analysant precisement<br />

les representations collectives<br />

des eglises de quartier dans le contexte<br />

actuel de Ia desaffectation ; tout au plus,<br />

certaines etudes soulignent !'importance<br />

des aspects culture! et identitaire dans<br />

Ia creation d 'un patrimoine religieux' .<br />

C'est pourquoi nous nous tournons<br />

vers Ia geographie de Ia representation<br />

pour alimenter le cadre theorique de<br />

notre etude.<br />

Les etu des geographiques sur les<br />

representations mentales se revelent<br />

particulierement fecondes pour notre<br />

!----!----!....<br />

analyse. A l'instar de Debarbieux et de<br />

Bailly 8 , nous considerons que Ia represen <br />

tation mentale de l'espace est un schema<br />

cognitif, une interpretation du reel, transmis<br />

soit par Ia perception d'un lieu, soit<br />

par les modes de communication, et qui<br />

s'inscrit dans un cadre ideologique. Ces<br />

representations individuelles interagissent<br />

entre elles grace aux moyens de communication,<br />

aux symboles et aux experiences<br />

pour se combiner et s'alterer mutuellement.<br />

De cette association, ou socialisation,<br />

resultent des representations collectives 9 •<br />

Celles-ci, continuellement alimentees par<br />

de nouvelles representations individuelles,<br />

fluctuent, se construisent ou se deconstruisent<br />

au fil du temps' 0 • Par ailleurs, ces<br />

representations collectives comportent<br />

une assise spatiale dans Ia mesure ou le<br />

groupe social ou culture! projette sur un<br />

lieu des valeurs affectives et identitaires,<br />

lui assignant par le fait meme une<br />

symbolique qui ancre dans celui-ci l'identite<br />

du groupe. Cette projection de valeurs<br />

resulte en un marquage territorial qui<br />

s'effectue par Ia production et l'entretien de<br />

referents identitaires, auxquels on accole<br />

frequemment le terme « patrimoine ».<br />

4<br />

JSSAC I JSEAC 30 > N' 1 > 2005

•,: r<br />

S OPHIE R IOUX-HE:BERT > ANALYSIS I ANALYSE<br />

., --=- ;:.'- \<br />

\ ,.,___,.....<br />

\<br />

\<br />

\ • • .-......:.: ~-4<br />

, . ··~~-_:;;. ,<br />

- ~·<br />

_...-·<br />

. '. \<br />

........<br />

...... - -.. ·~,: .~t ~Roy~l<br />

ILL. 4. L'EGLISE NOTRE-DAM E-D E-LA-DEFENSE I JONATHAN CHA<br />

ILL. 2. L'ARRONDISSEMENT ROSEMONT-LA PETI TE- PATRIE, SES TROIS QUART IE RS AIN SI<br />

QUE LE S DEU X EGLI SES DES PARO ISSES-MERES I PRODUIT PAR SOPHIE RIOUX-HEBERT<br />

Selon Gravaris-Barbas, « !'identification<br />

d'un groupe a un territoire [s 'exprime]<br />

compose de trois quartiers plus ou moins<br />

distincts : Ia Petite-Patrie, Rosemont et<br />

essentiellement a travers les elements Nouveau-Rosemont (ill. 1 et 2) .<br />

patrimoniaux materiels, portes par le territoire<br />

» 11 • Ainsi, les representations collectives<br />

peuvent mener a Ia patrimonialisation<br />

d'un lieu dans Ia mesure ou il y aurait un<br />

consensus au sein du groupe sur Ia valeur<br />

historique, architecturale, artistique et<br />

culturelle du lieu et sur !'importance de<br />

celui-ci dans !'affirmation identitaire et<br />

territoriale du groupe.<br />

LE CONTEXTE SOCIOHISTORIQUE<br />

DE L'ARRONDISSEMENT<br />

ROSEMONT-LA PETITE-PATRIE<br />

Pour illustrer nos propos, no us avons choisi<br />

d'explorer les representations que les re <br />

sidants de !'arrondissement Rosemont<br />

La Petite-Patrie possedent de leurs eglises.<br />

Le choix de cet arrondissement n'est pas<br />

fortuit. Celui-ci possede une riche histoire<br />

religieuse, s'etant developpe autour<br />

de deux poles paroissiaux catholiques,<br />

les paroisses Saint-Edouard et Sainte<br />

Philomene (qui devint, en 1964, Ia paroisse<br />

Saint-Esprit-de-Rosemont). II importe<br />

de mentionner que !'a rrondissement se<br />

La Petite-Patrie s'est developpe au tournant<br />

du vingtieme siecle grace a !'inauguration<br />

d'un trace de tramway qui Ionge Ia<br />

rue Saint-Denis (ancien chemin du Sault),<br />

entrainant le peuplement de ce quartier<br />

du nord de Ia ville". Les limites actuelles du<br />

quartier englobent une partie de deux an <br />

ciennes municipalites, Saint-Louis du Mile<br />

End et Coteau Saint-Louis, et de deux quartiers,<br />

Saint-Jean et Saint-Denis 13 • Compose<br />

majoritairement de Canadiens fran c;ais, a<br />

l'origine le secteur accueillit aussi des Italiens<br />

et des Canadiens anglais. Les premiers<br />

s'etablirent autour de Ia rue Saint-Denis<br />

et fonderent Ia paroisse Saint-Edouard en<br />

1895. La construction de l'eglise, situee au<br />

coin des rues Saint-Den is et Beaubien, fut<br />

terminee en 1909, ce qui en fait le lieu de<br />

culte le plus ancien de !'arrondissement<br />

(ill. 3) . Aujourd 'hui encore, l'eglise Saint<br />

Edouard constitue le cceur nevralgique<br />

du quartier. De me me que les francophones,<br />

les Canadiens anglais s'etablirent a<br />

proximite de Ia ligne de tramway, mais ils<br />

nommerent le secteur Amherst Park, du<br />

I JONATHAN CHA<br />

ILL. 6. L'EG LI SE SAINT-ARSENE I JONATHAN CHA<br />

JSSAC I JSEAC 30 > N' 1 > 2005<br />

5

S OPHIE R IOUX-H EBERT > ANALYSIS I ANALYSE<br />

nom d'une des compagnies immobilieres tive d'economie, ne s'est construit aucun dans le quartier. Par ailleurs, des angloqui<br />

le developpa. Les nombreux lieux de lieu de culte, utilisant plut6t l'eglise protestants et, plus tard, des immigrants<br />

culte protestants qui parsement toujours catholique Saint-Arsene (1954), situee ukrainiens de confessions orthodoxe et<br />

le quartier temoignent de cette presence sur Ia rue Belanger (ill. 6) . catholique s' installerent dans le quartier<br />

culturelle importante. Pour sa part, Ia<br />

communaute italienne s'etablit auteur du<br />

boulevard Saint-Laurent, entre les rues Saint<br />

Zotique et Jean-Talon, et c'est pourquoi ce<br />

secteur est nomme Piccola ltalia (Petiteltalie).<br />

L'eglise Notre-Dame-de-la-Defense<br />

(1911), classee monument historique national<br />

par le gouvernement federal en 2002,<br />

et l'eglise Notre-Dame-de-la-Consolata<br />

(1961) demeurent les deux lieux de culte<br />

les plus visibles de cette communaute (ill. 4<br />

et 5). En 1985, pour tenter de renforcer<br />

l'appartenance des residants au quartier 14 ,<br />

!'administration municipale lui accola<br />

!'appellation de Petite-Patrie, inspiree du<br />

titre d'un roman autobiographique de<br />

Claude Jasmin dans lequel il raconte son<br />

enfance dans le quartier 15 • Aujourd'hui,<br />

Ia communaute anglophone a pratiquement<br />

disparu du quartier et Ia population<br />

italienne a beaucoup diminue 16 • Par contre,<br />

une population latino-americaine s'y<br />

est installee. Celle-ci, dans une perspec-<br />

De meme que La Petite-Patrie, Rosemont<br />

a connu une urbanisation rapide vers le<br />

tournant du vingtieme siecle. L'element<br />

declencheur en fut l'arrivee du Canadien<br />

pacifique dans le sud-ouest du quartier".<br />

En effet, en 1902, le Canadien pacifique<br />

decida d'y installer ses usines de fabri <br />

cation et d'entretien de locomotives,<br />

communement appelees les Shops Angus.<br />

A partir de ce moment, les possibilites<br />

d'emplois aux Shops Angus ont amene un<br />

flot constant de nouveaux residants dans<br />

le quartier. La paroisse Sainte-Philomene,<br />

qui devint Saint-Esprit en 1964, vit le jour<br />

en 1904 et, l'annee suivante, le village de<br />

Rosemont fut fonde et annexe a Ia ville de<br />

Montreal. En 1933, Ia chapelle Sainte-Philomene,<br />

devenue trop exigue, fut remplacee<br />

pa r !'actuelle eglise Saint-Esprit , plus vaste<br />

et majestueuse (ill. 7) ' 8 . Celle-ci, situee sur<br />

Ia rue Masson, principale artere commerciale,<br />

jouit toujours d'une position centrale<br />

pour travailler au x usines Angus. Tout<br />

com me les catholiques, ces communautes<br />

y ont laisse leur marque sous Ia forme de<br />

nombreux lieux de culte. En 1961, Ia fermeture<br />

partielle des usines Angus amor ~ a le<br />

lent declin de Rosemont. Les anglophones<br />

et les Ukrainiens quitterent graduellement<br />

le quartier pour s'etablir dans differents<br />

secteurs de !'ouest de Ia ville. Toutefois,<br />

depuis les dix dernieres annees, Rosemont<br />

a subi un embourgeoisement semblable<br />

a celui de La Petite-Patrie grace a Ia<br />

tendance au reinvestissement des<br />

quartiers centraux, mais surtout grace a<br />

Ia reconversion des usines Angus, fermees<br />

en 1992, en technop61e eta Ia construction<br />

d'un vaste projet domiciliaire sur une<br />

partie des terrains laisses vacants .<br />

Au contraire de Rosemont et de La Petite<br />

Patrie qui se sont urbanisees des le debut<br />

du vingtieme siecle, Ia partie est de !'arrondissement<br />

ne se developpa veritablement<br />

6<br />

JSSAC I JSEAC 30 > N' 1 > 2005

S OPHIE R IOUX-HEBERT > ANA LYSIS I ANALYSE<br />

Ill. 11 . EGLISE SAINT-EUGENE I JONATHAN CHA<br />

que dans les annees 1950 pour repondre au !'arrondissement au centre de Ia polemique vifs debats societaux tant au sein qu'a !'exmanque<br />

de logement cause par le boom de- liee a Ia desaffectation des lieux de culte terieur de !'arrondissement, sur l'avenir des<br />

mographique de l'apres Deuxieme Guerre urbains. En effet, depuis les trois dernieres eglises de quartier. II y eut tout d'abord,<br />

mondiale. Deux projets ont favorise ce de- annees, quatre evenements ont suscite de en 2002, Ia demolition de l'eglise anglicane<br />

veloppement : le jardin botanique inaugure<br />

dans les annees 1930 et l'h6pital Maisonneuve<br />

construit dans les annees 1950. Considere<br />

comme une extension de Rosemont,<br />

le quartier s'est vu attribuee !'appellation<br />

de Nouveau-Rosemont. De plus, Ia population<br />

moins dense de ce quartier s'avere<br />

beaucoup plus homogene que dans le reste<br />

de !'arrondissement. Ainsi, seulement deux<br />

eglises catholiques francophones y ont pignon<br />

sur rue. Ne possedant aucun centre<br />

nevralgique, Nouveau-Rosemont peine toujours<br />

a se construire une identite distincte.<br />

ISD!¥1111<br />

Les cinq eglises les plus importantes selon les repondants et les types de raisons<br />

evoquees pour justifier ces choix<br />

1. Eglise 2. Eglise<br />

Saint-Edouard Saint-Esprit<br />

3. Cathedrale 4. Eglise Saintorthodoxe<br />

Jean-de-la-Croix<br />

Sainte-Sophie (avant sa reconversion)<br />

5. Eglise<br />

Saint-Marc<br />

Proportion de<br />

repondants ayant<br />

choisi ces eg lises<br />

67 % 50% 44% 38 % 34%<br />

Types de raisons<br />

Proportion de reponses se classant dans chaque categorie de raison pour chacune des egli ses<br />

En 1992, !'administration municipale<br />

regroupa ces trois quartiers en arrondissement,<br />

mais ce dernier n'obtint de veritables<br />

pouvoirs decisionnels qu'en 2001<br />

grace a Ia reforme municipale. Aujourd'hui,<br />

!'arrondissement compte 37 eglises de<br />

confession majoritairement catholique,<br />

mais aussi protestante et orthodoxe' 9 •<br />

Ce corpus imposant d'eglises positionne<br />

Valeurs architecturale 55% 57% 75% 62 % 50%<br />

et artistique<br />

Valeur identitaire<br />

(attachement et<br />

38% 33% 18% 28% 41%<br />

habitude)<br />

Valeurs sociale et 5 % 8%<br />

communautaire<br />

7% 5% 8 %<br />

Va leur historique 1 % 2 % 0% 3% 1 %<br />

Valeur spirituelle 1 % 2 % 0 % 2% 1 %<br />

JSSAC I JSEAC 30 > N' 1 > 2005<br />

7

S OPHIE R IOUX-HEBERT > ANALYSI S I ANALYSE<br />

1. ~GLISE SAINT - ~DOUARD 2. ~GLISE SAINT-ESPRIT<br />

3. CATH~DRALE ORTHODOXE<br />

SAINTE-SOPHIE<br />

4. ~GLISE SAINT-JEAN -DE-LA-CROIX 5. ~GLISE SAINT-MARC<br />

St. Lukes (1928) qui fut remplacee par des<br />

condominiums, suivie en 2003 de Ia demolition<br />

de l'eglise catholique Saint-Etienne<br />

(1914) qui fit place a des logements<br />

sociaux et de Ia reconversion de l'eglise<br />

catholiq ue Saint-Jean-de-la-Croix (1926)<br />

en condominiums haut de gamme. Finalement,<br />

Ia reconversion, amorcee en 2004,<br />

de l'eglise catholique Saint-Eugene (1954)<br />

en hall communautaire d'un complexe de<br />

logements sociaux se poursuit toujours<br />

(ill. 6-9). Ces recents bouleversements,<br />

qui ont marque l'imaginaire collectif des<br />

residants, ainsi que Ia presence toujours<br />

forte des eglises dans le tissu urbain de<br />

!'arrondissement, en font un terrain privilegie<br />

pour l'etude des representations<br />

collectives de ces memes batiments.<br />

DES REPRESENTATIONS INEGALES<br />

Dans le but de decouvrir si les representations<br />

collectives des eglises temoignent<br />

d'un processus de patrimonialisation,<br />

nous avons interroge 304 residants de<br />

Rosemont-La Petite-Patrie au printemps<br />

2004' 0 • Nous avons classe les resultats en<br />

trois themes devant nous permettre de<br />

saisir, en partie du moins, Ia nature de<br />

leurs representations: !'importance relative<br />

des eglises et les raisons justifiant<br />

ces choix, les fonctions que les residants<br />

associent aux eglises et les valeurs qu'ils leur<br />

conferent.<br />

L'importance relative des eglises<br />

Nous avons cherche a connaTtre les eglises<br />

de !'arrondissement qui sont considerees<br />

par les residants comme etant les plus importantes.<br />

Pour ce faire, nous leur avons<br />

presente une planche-photo repertoriant<br />

toutes les eglises de !'arrondissement en<br />

leur demandant de choisir les trois plus importantes<br />

selon leurs propres criteres. S'ils<br />

avaient de Ia difficulte a repondre, nous<br />

leur demandions ensuite quelles etaient<br />

leurs trois eglises preferees. L'analyse<br />

des resultats montre que cinq eglises se<br />

demarquent particulierement des autres :<br />

l'eglise Saint-Edouard, l'eglise Saint-Esprit,<br />

Ia cathedrale orthodoxe Sainte-Sophie,<br />

l'eglise Saint-Jean-de-la-Croix et l'eglise<br />

Saint-Marc (tableau 1 ).<br />

Ce qui surprend de prime abord dans cette<br />

liste, c'est le rang qu'occupe l'ancienne<br />

eglise Saint-Jean-de- la -Croix. En effet,<br />

celle-ci se classe au quatrieme rang des<br />

eglises les plus importantes de !'arrondissement,<br />

selon les repondants, ce qui<br />

s'avere tout de meme etonnant pour une<br />

eglise qui fut reconvertie en coproprietes<br />

en 2003. Un autre resultat quelque peu<br />

surprenant concerne Ia cathedrale orthodoxe<br />

Sainte-Sophie qui se classe au<br />

troisieme rang. Pourtant, seulement un<br />

repondant de notre echantillon etait de<br />

confession orthodoxe, tandis que 71 %<br />

des repondants etaient de confession catholique".<br />

Cette majorite de repondants<br />

catholiques peut expliquer pourquoi les<br />

quatre autres eglises en tete de liste sont<br />

de vocation catholique. Fait a noter, les<br />

deux eglises des paroisses fondatrices de<br />

!'arrondissement, l'eglise Saint-Edouard et<br />

l'eglise Saint-Esprit, arrivent au premier et<br />

au deuxieme rangs respectivement. On<br />

note egalement que, a part Ia cathedrale<br />

orthodoxe Sainte-Sophie qui fut erigee<br />

en 1962, toutes les eglises de cette liste<br />

furent erigees pendant Ia periode allant<br />

de 1900 a 1935. On peut d'ailleurs observer<br />

des similitudes architecturales entre<br />

celles-ci. En effet, ces eglises possedent un<br />

style architectural traditionnel caracterise<br />

par une monumentalite, une elevation du<br />

plancher, un plan longitudinal et de hauts<br />

clochers 22 • Ces similitudes dans !'architecture<br />

de quatre des cinq eglises en tete de<br />

liste nous portent a croire que les repondants<br />

auraient une preference pour les<br />

eglises qui arborent ce style architectural<br />

traditionnel.<br />

Par ailleurs, il importe de noter qu'aucune<br />

de ces cinq eglises n'est classee patrimoniale<br />

par le gouvernement du Quebec ou du Ca <br />

nada. Seule l'eglise Saint-Esprit beneficie<br />

d'une protection a l'echelle municipale,<br />

car elle fait partie d'un site du patrimoine<br />

constitue en 1990 23 • La seule eglise qui<br />

possede une protection nationale, l'eglise<br />

Notre-Dame-de-la-Defense, classee monument<br />

historique du Canada, n'apparaTt<br />

qu'en treizieme position de notre liste.<br />

Ce constat suggere que l'eglise Notre-Damede-la-Defense<br />

jouit d'un statut mal defini<br />

a l'interieur de !'arrondissement, mais que<br />

8<br />

JSSAC I JSEAC 30 > N• 1 > 2005

S OPHIE R IOUX-H EBERT > ANALYSIS I ANALYSE<br />

son statut d'eglise-mere de Ia communaute<br />

italienne de Montreal lui confere<br />

un rayonnement important aux echelles<br />

regionale et nationale.<br />

Nous avons classe en cinq categories les<br />

raisons qui justifient les choix des repondants<br />

: 1) valeurs architecturale et artistique,<br />

2) valeur identitaire liee a !'habitude<br />

et a l'attachement, 3) valeurs sociale et<br />

communautaire, 4) valeur historique et<br />

5) valeur spirituelle (tableau 1). De plus,<br />

puisque les repondants justifiaient fre <br />

quemment leurs choix en evoquant plusieurs<br />

raisons se classant dans differentes<br />

categories, nous avons divise le nombre<br />

de reponses dans chaque categorie par le<br />

total de raisons evoquees pour chacune<br />

des eglises et non par le total de repondants.<br />

Les resultats de cette analyse montrent<br />

que Ia raison principale qui motive<br />

les choix des repondants est d'ordre<br />

esthetique. De fait, les repondants se sont<br />

grandement bases sur les dimensions et le<br />

style architectural d'une eglise pour faire<br />

leurs choix. C'est pourquoi les eglises les<br />

plus majestueuses se trouvent en tete de<br />

liste alors que les eglises de style moderne<br />

n'y figurent pas. La deuxieme raison evoquee<br />

le plus souvent releve d'un sentiment<br />

identitaire lie a !'habitude et a l'attachement.<br />

Plusieurs repondants ont choisi des<br />

eglises au xquelles ils s'identifient, soit parce<br />

qu' ils les connaissent depuis longtemps<br />

(s'y etant maries, ayant passe leur enfance<br />

dans Ia paroisse, etc.), soit parce qu'ils les<br />

c6toient f requemment (y assistant a Ia<br />

messe regulierement, passant devant tous<br />

les jours, habitant a proximite, etc.). No us<br />

remarquons que Ia cathedrale orthodoxe<br />

Sainte-Sophie a ete choisie beaucoup plus<br />

pour ses qua lites esthetiques que pour des<br />

raisons liees a !'habitude et a l'attachement.<br />

Beaucoup de repondants semblaient<br />

Ia reconnaitre et apprecier son architecture<br />

de style byzantin qui ajoute, selon eux, un<br />

exotisme au quartier; cependant, com me<br />

c'est un lieu de culte orthodoxe, peu s'y<br />

sont identifies.<br />

Pour ce qui est des activites sociales et<br />

communautaires, peu de repondants<br />

ont choisi ces raisons pour justifier leurs<br />

choix. Encore plus marquant est le fait<br />

que personne ou presque n'ait evoque<br />

Ia valeur historique de ces eglises comme<br />

raison de leurs choix. Pourtant, l'eglise<br />

Saint-Edouard, Ia plus ancienne de<br />

!'arrondissement, a joue un role non<br />

negligeable dans le developpement du<br />

nord de Ia ville. Aussi, nous remarquons<br />

que 3 % des repondants accordent une<br />

valeur historique et 2 % une valeur spirituelle<br />

a l'eglise Saint-Jean-de-la-Croi x, une<br />

eglise qui pourtant n'existe plus comme<br />

lieu de culte. Finalement, pour ce qui est<br />

de Ia qualite spirituelle, c'est-a-dire Ia<br />

qualite et Ia frequence de Ia messe, Ia<br />

disponibilite du pretre, etc., Ia faible proportion<br />

de gens qui ont choisi cette raison<br />

reflete sans doute Ia faible frequentation<br />

de ces lieux pour le culte.<br />

Par contraste, l'examen des cinq eglises<br />

qui ont obtenu le moins de mentions de<br />

Ia part des repondants nous apporte un<br />

eclairage complementaire sur Ia nature des<br />

representations des residants (tableau 2). II<br />

importe d 'abord de noter qu'a part l'eglise<br />

nationale polonaise Sainte-Croix, toutes<br />

ces eglises sont de vocation protestante.<br />

La majorite des repondants etant catholiques,<br />

ces lieux de culte les interpellent done<br />

d'une maniere moindre. II faut dire que le<br />

lieu de culte pour les protestants ne revet<br />

pas Ia meme signification, Ia meme symbolique,<br />

que pour les catholiques. En effet,<br />

pour une grande partie des protestants, a<br />

!'exception des anglicans, le culte se celebre<br />

dans une sobriete et une simplicite qui<br />

lf11C!¥11tl<br />

En ordre decroissant, les cinq eglises les moins importantes de !'arrondissement selon les repondants<br />

1. Eglise adventiste<br />

Beer Sheba<br />

2. Ministere de Ia foi<br />

en Jesus-Christ<br />

3. Centre evangelique<br />

eglise du Nazareen<br />

4. Eglise nationale<br />

polonaise Sainte-Croix<br />

5. Rosemount<br />

United Church<br />

1. PHOTO : FONOATION DU PATRIMOINE REUGIEUX 2, 3, 4, 5. PHOTOS : JONATHAN CHA<br />

JSSAC I JSEAC 30 > N' 1 > 2005<br />

9

S OPHIE R IOUX-HEBERT > ANALYSIS I ANALYSE<br />

100%<br />

80 %<br />

• 20 - 34 ans<br />

c<br />

• 35-54 ans<br />

0<br />

'f 60 %<br />

• 55 ans et +<br />

0<br />

c.<br />

0<br />

.t 40 %<br />

20 %<br />

0%<br />

Types de fonction<br />

economique<br />

touristique<br />

Les fonctions des eglises<br />

de /'arrondissement<br />

Un element qui revele une facette differente<br />

de Ia representation que possedent<br />

les res idants de leurs eglises reside dans<br />

leur perception de l'utilite de celles-ci .<br />

Nous avons done pose aux residants Ia<br />

question suivante : « A quoi servent les<br />

eglises de votre arrondissement selon<br />

vous ? >>. Nous avons classe leurs reponses<br />

en six categories qui ne sont pas exclusives,<br />

puisque plusieurs personnes ont nomme<br />

plus d'une fonction :<br />

ILL. 12. LES FONCTIONS DES EGLISES DE l'ARR ON DISSEME NT SELON LES REPONDANTS<br />

se refletent dans !'architecture depouiiiE~e<br />

du lieu de culte 24 • Au contraire, dans Ia<br />

tradition catholique romaine, les eglises,<br />

erigees pour Ia gloire de Dieu, temoignent<br />

de Ia grandeur de Ia foi de ceux qui financent<br />

leur construction et du pouvoir<br />

de I'Eglise catholique dans Ia societe. C'est<br />

pourquoi les eglises catholiques possedent<br />

bien souvent une somptuosite et un faste<br />

qui n'ont aucun egal dans !'architecture<br />

des batiments environnants". En outre, il<br />

faut com prendre que les communautes re-<br />

ligieuses protestantes qui se sont etablies<br />

dans !'arrondissement etaient de taille<br />

reduite et n'avaient done pas les moyens<br />

financiers ni le besoin de batir de plus<br />

grands et plus riches lieux de culte. Par<br />

consequent, le style architectural austere<br />

de ces quatre temples, qui se positionne a<br />

l'encontre de !'archetype de l'eglise pour<br />

les catholiques, a certainement joue en<br />

leur defaveur. Par ailleurs, leurs dimensions<br />

reduites et leur emplacement sur des<br />

rues residentielles ne leur donnent pas une<br />

visibilite et un rayonnement tres grands.<br />

Pourtant, elles font partie des dix eglises<br />

les plus anciennes de !'arrondissement.<br />

Trois de celles-ci, le centre evangelique<br />

eglise du Nazareen, le Ministere de Ia foi<br />

en Jesus-Christ et le Rosemount United<br />

Church, furent construites dans les annees<br />

1910, ce qui en fait les lieux de culte les<br />

plus anciens de !'arrondissement apres<br />

l'eglise Saint-Edouard. Ainsi, en depit de<br />

Ia modestie de leur architecture, ces lieux<br />

de culte possedent une valeur historique<br />

non negligeable puisqu'elles temoignent<br />

de Ia presence de Ia communaute angloprotestante<br />

des les debuts du developpement<br />

de !'arrondissement. Finalement,<br />

le pietre classement de l'eglise nationale<br />

polonaise Sainte-Croix peut s'expliquer par<br />

Ia banalite de son architecture, sa situation<br />

sur une rue tranquille ainsi que Ia faible<br />

representativite des residants d'origine<br />

polonaise dans notre echantillon 26 •<br />

45 %<br />

40 %<br />

35 %<br />

c 30 %<br />

0<br />

'f 25 %<br />

0<br />

c. 20%<br />

e<br />

a..<br />

15%<br />

10%<br />

5%<br />

0%<br />

religieuse<br />

sociale<br />

Valeurs<br />

1. fonction spirituelle ;<br />

2. fonction communautaire<br />

(evenements de charite, bazars, etc. ) ;<br />

3. fonction sociale<br />

(lieux de rassemblement, endroits ou<br />

rencontrer des gens, etc.) ;<br />

4. fonction ludique<br />

(danses, fetes, etc.);<br />

5. fonction economique<br />

(pole d'attraction et de developpement<br />

dans le quartier);<br />

6. fonction touristique.<br />

ILL. 13. LES VALEURS DES EGLISES DE l'ARRONDISSEMENT SELON LES REPONDANTS<br />

• 20 · 34 ans<br />

• 35 · 54 ans<br />

• 55 ans et +<br />

10<br />

JSSAC I JSEAC 30 > N' 1 > 2005

S OPHIE R IOUX-HEBERT > ANALYSIS I ANALYSE<br />

L'analyse nous demontre que Ia grande<br />

majorite des gens considerent que Ia fonction<br />

principale des eglises est spirituelle<br />

(ill. 12). En deuxieme et troisieme positions<br />

arrivent les fonctions communautaire et<br />

sociale. La fonction touristique, envisagee<br />

par certains auteurs comme une possible<br />

solution de reconversion 27 , arrive loin derriere<br />

dans le classement avec seulement<br />

2 % des repondants de 20-34 ans qui<br />

l'ont suggeree. Ce 2 % annonce toutefois<br />

!'emergence d'une transition dans Ia<br />

perception de l'eglise d'un lieu cultuel a<br />

un lieu culture I. Cette transition s'observe<br />

d'ailleurs entre Ia perception des gens plus<br />

ages qui, a 80 %, considerent que l'utilite<br />

principale des eglises est le culte et celle<br />

des autres groupes d'age qui accordent un<br />

peu moins d'importance a cette fonction<br />

et un peu plus a Ia fonction communautaire.<br />

Malgre ce faible decalage entre les<br />

groupes d'age, les representations des repondants<br />

concernant l'utilite des eglises<br />

demeurent conservatrices. De fait, meme<br />

si Ia majorite de ceux-ci ne frequentent<br />

plus que tres rarement, sinon jamais, les<br />

eglises, ils les per 2005<br />

11

S OPHIE A IOUX-HE:BERT > ANALYSIS I ANALYSE<br />

de !'arrondissement de 1992, puis dans<br />

le rapport de !'evaluation du patrimoine<br />

urbain de !'arrondissement de 2004 30 • De<br />

plus, une etude de Ia Chaire de recherche<br />

du Canada en patrimoine urbain de I'Universite<br />

du Quebec a Montreal confirme<br />

Ia valeur patrimoniale elevee des eglises<br />

Saint-Edouard, Saint-Esprit et Saint-Marc 3 '.<br />

Bien que Ia valeur historique de l'eglise<br />

Saint-Jean-de-la-Croix y soit mentionnee,<br />

celle-ci n'a pas fait l'objet d'une evaluation<br />

patrimoniale de meme nature que les<br />

trois precedentes, puisqu'elle a deja subi<br />

passablement de modifications architecturales32.<br />

Enfin, notre etude souligne Ia<br />

valeur emblematique de Ia cathedrale<br />

orthodoxe Sainte-Sophie qui lui procure<br />

un rayonnement au-dela des frontieres<br />

de !'arrondissement. Cette comparaison<br />

avec les etudes patrimoniales de Ia ville<br />

et des experts nous incite a conclure que<br />

les repondants, malgre leur faible evocation<br />

de Ia valeur historique des eglises<br />

choisies, ont fait preuve d'une conscience<br />

patrimoniale dans leurs choix.<br />

Si les repondants demontrent une sensibilite<br />

a Ia beaute architecturale et artistique<br />

des eglises, ils semblent difficilement<br />

pouvoir se les representer autrement<br />

qu'en lieux de culte. De fait, les resultats<br />

lies a Ia perception de Ia fonction et des<br />

valeurs des eglises montrent des representations<br />

beaucoup plus traditionnelles<br />

que ce a quoi nous nous attend ions. Ainsi,<br />

en depit du fait que leur frequentation<br />

a beaucoup diminue, les repondants se<br />

representent toujours les eglises comme<br />

des lieux servant principalement au culte<br />

et comme des lieux investis d'une valeur<br />

religieuse avant tout.<br />

De tels resultats suggerent que les eglises<br />

possedent toujours une dimension sacree a<br />

leurs yeux et qu'elles repondent toujours a<br />

un besoin de spiritualite qui, meme s'il ne<br />

se materialise que pour les rites de passage<br />

ou les fetes religieuses, requiert, a tout<br />

le moins, Ia conservation de Ia fonction<br />

cultuelle pour quelques-unes des eglises<br />

de !'arrondissement. II importe de souligner<br />

que ces rites et ces celebrations font<br />

partie des traditions qui appartiennent a<br />

l'identite et a Ia culture quebecoises et<br />

c'est pourquoi certains residants y sont<br />

attaches. A ce sujet, il faut s'interroger<br />

sur un possible glissement semantique du<br />

terme N• 1 > 2005

SOPH IE R IOUX-HEBERT > ANALYSIS I ANALYSE<br />

3. Kong, Lily, 2001, « Mapping 'New' Geographies<br />

of Religion: Politics and Poetics in Modernity »,<br />

Progress in Human Geography, vol. 25, n• 2,<br />

p. 211-233; et Kong, Lily, 1990, >,<br />

Yearbook of the Association of Pacific Coast<br />

Geographers, n• 45, p. 55-70.<br />

5. Ibid.<br />

6. Humeau, Jean-Bertrand, 1997, ,<br />

dans Jacques Levy et Michel Lussault (dir.),<br />

Dictionnaire de Ia geographie et de l'espace des<br />

societl!s, Paris, Belin, p. 791 ; et Bailly, Antoine,<br />

1995, ><br />

dans Antoine Bailly, Roger Ferras et Daniel<br />

Pumain (dir.), Encyclopedie de geographie,<br />

Paris, Economica, p. 371-383.<br />

9. Relph, Edward, 1976, Place and Placelessness,<br />

Londres, Pion; et Durkheim, Emile, 1967,<br />

Sociologie et philosophie, Paris, Presses<br />

universitaires de France<br />

10. Debarbieux, Bernard, 2001, , n• 9,<br />

Montreal, Ville de Montreal / Ministere des<br />

Affaires culturelles.<br />

18. Cha, Jonathan, 2005, Evaluation du potentie/<br />

monumental du patrimoine religieux de<br />

/'arrondissement Rosemont-La Petite-Patrie<br />

a Montreal, memoire de maitrise, Montreal,<br />

Universite du Quebec a Montreal.<br />

19. Nous incluons sous le vocable N' 1 > 2005<br />

13

S OPHIE R IOUX-H EBERT > ANALYSIS I ANALYSE<br />

23. Ville de Montreal, Service de Ia mise en valeur<br />

du territoire et du patrimoine, Division du<br />

patrimoine et de Ia toponymie, 2004, Evaluatio!?<br />

du patrimoine urbain. Ville de Montreal,<br />

Arrondissement de Rosemont-La Petite-Patrie<br />

-26, 5 mai 2004, Montreal.<br />

24. Munkittrick, Judy A., 1984, Les eglises<br />

protestantes de Ia region de Coaticook,<br />

Coaticook, Quebec, Musee Beaulne; et<br />

Bergevin, Helene, 1981 , L'architecture des<br />

eglises protestantes des Cantons de /'Est et<br />

des Bois Francs au XIX' siecle, Art ancien du<br />

Quebec I Etudes, n' 3, Sainte-Fay, Quebec,<br />

Universite Laval.<br />

25. Martin, Paul-Louis, 2001, « Le paysage des<br />

noyaux religieux >>, dans Serge Courville et<br />

Normand Seguin (dir.), La Paroisse, Atlas<br />

historique du Quebec, Sainte-Fay, Quebec, Les<br />

Presses de I'Universite Laval, p. 53-81 .<br />

26. Sur les 304 repondants, un seul a affirme etre<br />

d'origine polonaise.<br />

27. Blais, Sylvie, et Pierre Bellerose, 1997, « Analyse<br />

du potentiel touristique du patrimoine religieux<br />

mont realais >>, Teoros, val. 16, n' 2, p. 38-40 ;<br />

Noppen, Luc, et Lucie K. Morisset, 1997, « A<br />

propos de paysage culture! : le patrimoine<br />

architectural religieu x, une offre distinctive au<br />

Quebec 7 >> Teoros, val. 16, n' 2, p. 14-20; et<br />

Noppen, Luc, et Lucie K. Morisset, 2003, « Le<br />

tourisme rellgieux et le patrimoine 7 >> Teoros,<br />

val. 22, n' 2, p. 69-70.<br />

28. Demers, Christiane, 1997, « Rapport de<br />

I' atelier 1: L'economie >> dans Nap pen, Luc,<br />

Lucie K. Morisset, et Robert Caron (dir.) 1997, La<br />

conservation des eg/ises dans /es vil/es-centres,<br />

Sillery, Les editions du Septentrion, p. 141 -144.<br />

29. Cha, /oc. 6 •.<br />

30. Ville de Montreal. 2004; et Ville de Montreal,<br />

Service de !'habitation et du deve·loppement<br />

urbaiA, 1992, Plan d'urbanisme : plan directeur<br />

de /'arrondissement Rosemont I Petite-Patrie,<br />

Montreal.<br />

31 . Cha, /oc. cit<br />

32. Cha, /oc. cit.<br />

33. Noppen et Morisset, 2003 : 69-70.<br />

14<br />

JSSAC I JSEAC 30 > N' 1 > 2005

ANALYSIS I ANALYSE<br />

ST. ANNE'S ANGLICAN CHURCH<br />

AND ITS PATRON<br />

PETER COFFMAN 1s a doctoral student at<br />

Queen's Univei'Sity, w1th prev1ous degrees from<br />

>PETER COFFMAN 1<br />

York. Ryerson. and the Un1vers1ty of Toronto.<br />

He has published on varrous aspects of English<br />

Rornanesque end Gothic Rev1val arch1tectu1'e.<br />

and h1s architectural photogl'aphy has been<br />

exhibited at d1fferent venues 111 Canada and<br />

the Un1ted States.<br />

Ther e is one city church which is not afraid of<br />

in novation [ ... ] When the present St. Anne's<br />

was built in Byzantine style instead of the<br />

conventional Gothic, there was surprise and<br />

to t his day its unusual lines [ ... ] stand out<br />

for their suggestion of the Moslem world<br />

[The Globe, December 15, 1923].<br />

By the time St . Anne's Anglican<br />

Church was completed in 1925, it was<br />

certainly the oddest Anglican church in<br />

Toronto, and arguably in the country<br />

(fig. 1). Designed in 1907 by Ford Howland,<br />

St. Anne's is Byzantine in style, with interior<br />

murals and sculptures by such artists as<br />

J.E.H . MacDonald, Frederick Varley, Frank<br />

Carmichael, Frances Loring, and Florence<br />

Wyle. It rema ins a singular monument<br />

to a wilful, visionary, and singularly<br />

determined patron, the Rev. Lawrence<br />

Skey.<br />

At the time St. Anne's was built, Gothic<br />

had for several decades been the accepted<br />

and expected style for Anglican churches.<br />

That had come about largely through the<br />

zeal of the Cambridge Camden Society,<br />

which held an iron grip on matters of Anglican<br />

architectural propriety in the middle<br />

and later nineteenth century.' Since<br />

the 1850s, their model church had been<br />

William Butterfield's All Saints, in London<br />

(fig. 2). 3 Later christened "The Ecclesiological<br />

Society," the Camdenians aired their<br />

views, praised "good" church architects,<br />

admonished "bad" ones, and generally<br />

bullied the architectural community into<br />

submission in the pages of their journal,<br />

The Ecclesiologist. The influence of<br />

the Society was enormous, and their<br />

judgements had a profound effect on the<br />

careers of many Victorian architects.'<br />

Ecclesiological Gothic arrived in British<br />

North America via the east coast. Christchurch<br />

Cathedral in Fredericton (begun<br />

JSSAC I JSEAC 30 > N 1 > 2005 > 17-26<br />

15

PETER COFFMAN > ANALYSIS I ANALYSE<br />

1845), designed mostly by Frank Wills (the Gothic was complete. No other style,<br />

east end was completed by Butterfield), it seemed, was as beautiful, as pracwas<br />

one of the most ecclesiologically up<br />

to date buildings of its day. 5 That was closely<br />

tical, as adaptable, as rational-in short,<br />

as English.<br />

followed by the Anglican Cathedral of<br />

Seven years after the completion of All<br />

St. John's, Newfoundland, begun in 1847<br />

Saints, London, in 1867, Lawrence Edward<br />

to the designs of the most prolific and famous<br />

of all Victorian architects, Sir George<br />

Skey was born to a good Anglican family<br />

in Toronto. In 1902, Lawrence Skey-by<br />

Gilbert Scott.• Through the second half of<br />

then the Rev. Lawrence Skey-became Rector<br />

of St. Anne's Anglican Church, whose<br />

the nineteenth century, Ecclesiological Gothic<br />

established itself in Toronto 7 through<br />

congregation worshipped in a respectable<br />

such monuments as St. James' Cathedral by<br />

Gothic Revival church in Toronto's west<br />

Frederick Cumberland and Thomas Ridout<br />

end that had been designed by Kivas<br />

in 1849 (fig. 3), 8 St. James's Cemetery Chapel<br />

Tully (fig. 5). That church, built in 1862,<br />

(Cumberland and Storm, 1857-1861), 9<br />

had been enlarged by the addition of a<br />

St . Paul's Church (G .K. and E. Radford,<br />

south aisle in 1879, a north aisle in 1881 ,<br />

1861),' 0 All Saints Church (Richard Windeyer,<br />

1874), and the Church of St. Alban<br />

and by the addition of transepts and a<br />

new chancel in 1888. 17 Skey soon realized<br />

the Martyr (Richard Windeyer and John<br />

that his flock had yet again outgrown its<br />

Falloon, 1885-1891). The identification of<br />

space, and a special meeting of the congregation<br />

was called on April 17, 1906, to<br />

Gothic with the Established Church even<br />

extended to academia, where Bishop John<br />

discuss the building of a new church.' 8 By<br />

Strachan's Trinity College, founded in 1851,<br />

1907, Skey was ready to act.<br />

was housed in an appropriately "Pointed"<br />

building on Queen Street West designed<br />

by Kivas Tulley."<br />

It is not known whether, by 1907, the<br />

Anglican authorities in Toronto already<br />

knew that Lawrence Skey was born to be<br />

Thus, by the time St . Anne's was built,<br />

a square peg in a round hole. If not, then<br />

Gothic utterly dominated Anglican church<br />

they would know by 1908, when Skey held<br />

building in British North America. It did<br />

the first service in his newly built (but not<br />

not matter that Gothic had originated in<br />

yet decorated) church (fig. 6). The unsuspecting<br />

Toronto Anglicans of 1908, familiar<br />

medieval France," nor did it matter that<br />

the Gothic Revival's first great champion<br />

with the traditions of Anglican architecture,<br />

must have thought that a dreadful<br />

as a serious church style had been a zealous<br />

Catholic convert, A.W.N. Pugin. 13 To<br />

mistake had occurred. The architect, Ford<br />

the eyes of a century ago, Gothic was as<br />

Howland, produced a Byzantine design<br />

English, and as Anglican, as architecture<br />

that would have looked quite at home in<br />

could be. 14 That is reflected in St. Anne's<br />

very near contemporary, St. Paul's Anglican<br />

Church (the successor to the Radford<br />

brothers' building), designed by E.J . Lennox<br />

in 1913 (fig. 4) . 15 With its size, rectilinear<br />

apse, delicate arch mouldings, and<br />

cliff-like transept fa N' 1 > 2005

P ETER C OFFMAN > ANALYSIS I ANALYSE<br />

concerned with church union. Exceedingly<br />

resistant to the idea of papal supremacy,<br />

he had written off the Roman Catholics,<br />

and had, by his own admission, no<br />

sympathy at all for the Anglo-Catholics.<br />

Skey's hope was for union with the Protestant<br />

denominations and, according to<br />

Mastin, his choice of Byzantine was a deliberate<br />

attempt to evoke an early era of<br />

church history not blighted by interdenominational<br />

schisms and bickering.<br />

If that was his motivation, however, it is<br />

not clear why Byzantine would have seemed<br />

the right choice. An early Christian<br />

Basilica, being the style spread by Constantine<br />

himself when there was only one<br />

Christian Church, would have done just as<br />

well. Romanesque, a style which flourished<br />

centuries before the Reformation, was<br />

already well established in Toronto, both<br />

in sacred and secular contexts." Indeed<br />

Gothic, which also pre-dates the Reformation,<br />

would offer a distinctly English idiom<br />

within which to work, and enjoyed the<br />

wholehearted approval of the Anglican<br />

establishment as well as a solid grounding<br />

in Anglican theology. Moreover, anyone<br />

familiar enough with church history and<br />

architecture to have been concerned with<br />

that question in the first place would<br />

surely have known that, in choosing<br />

Byzantine, he was erecting a potent reminder<br />

not of church unity, but of the<br />

great and ancient schism in church history<br />

between Rome and Constantinople.»<br />

More recently, Marilyn MacKay has suggested<br />

that Skey's architect, Ford Howland,<br />

was the driving choice behind the selection<br />

of Byzantine. 23 Howland, she argues,<br />

is far more likely than his patron to have<br />

been up to date with current architectural<br />

trends, and by the time he began designing<br />

St. Anne's, the Byzantine Revival was<br />

a significant, though not widespread,<br />

trend. James Cubitt had recommended<br />

Byzantine for Protestant worship in his<br />

FIG. 5. 'OLD' ST. ANNE 'S, TORONTO, BY KIVAS TULLEY (1862)<br />

Church Designs for Congregations in<br />

1870. 24 Whether either Howland or Skey<br />

owned a copy of that book is unfortunately<br />

not known. John Oldrid Scott and<br />

Beresford Pite had each designed one<br />

Byzantine Anglican church in London."<br />

The best-known example of the Byzantine<br />

Revival, however, was the Roman Catholic<br />

Cathedral in Westminster-hardly a model<br />

likely to have been emulated by an anti<br />

Catholic low-churchman like Skey. A letter<br />

in the Anglican archive in Toronto, written<br />

in 1960 by one P. Douglas Knowles,<br />

muddles things further.'• According to<br />

Knowles, who identified himself as a<br />

friend and neighbour of Ford Howland's<br />

from 1907-1910, the architect had intended<br />

St. Anne's to be a miniature version of the<br />

Roman Catholic Cathedral at Manila, Philippines.<br />

If that is true, then one can only<br />

suppose that Howland had kept it a secret<br />

from his patron-like Westminster Cathedral,<br />

this is hardly a model that would<br />

have impressed Skey. And therein lies the<br />

FIG. 6. ST. ANNE'S ANG LICAN CHU RCH, TORONTO;<br />

INTERIOR BEF ORE DECORATI ON<br />

JSSAC I JSEAC 30 > N• 1 > 2005<br />

17

PETER COFFMAN > ANALYSIS I ANALYSE<br />

FIG. 7. WALMER ROAD BAPTIST CHURC H, TORONTO, BY LANGLEY AND BURKE (BEGUN 1889) I PETE R COFFMAN<br />

main problem with attributing too much<br />

credit to Howland: whatever his wishes<br />

and inspirations, nothing was going to<br />

happen unless Lawrence Skey agreed that<br />

it was a good idea. And, as we shall see,<br />

Skey was no pushover.<br />

A simpler explanation may suffice. Skey<br />

was a Low Church Anglican, deeply com <br />

mitted to both halves of that label. Gothic<br />

had been revived in large part to facilitate<br />

the Anglo-Catholic liturgy; thus, it was<br />

the style of the High Church, and would<br />

have been undesirable to Skey. Byzantine,<br />

on the other hand, was emphatically not<br />

High Church in appearance, as well as<br />

being spatially well suited to Low Church,<br />

sermon-centred services. Nor could it<br />

be confused with non-Anglican spaces<br />

built by Protestant denominations like<br />

the Baptists and Methodists, whose amphitheatrical<br />

plans (for example, Walmer<br />

Road Baptist Church, 1888-1992, fig . 7)<br />

were by that time a frequent feature of<br />

the Canadian architectural landscape. In<br />

Byzantine, Skey had a style that was practical,<br />

unique, beautiful, and free of ideological<br />

baggage that would play into the<br />

hands of the feuding Protestants of early<br />

twentieth-century Toronto.<br />

Those considerations may have justified<br />

the choice of Byzantine in Skey's mind,<br />

but the choice remained an extremely<br />

unconventional one for Canadian Anglicans.<br />

In order to execute a highly original<br />

and expensive project within a highly<br />

conservative institution, it helps to have a<br />

dynamic, charismatic, slightly bull-headed<br />

instigator pushing it along. By all accounts,<br />

that describes Lawrence Skey quite accurately<br />

(fig. 8) . A newspaper profile of 1917<br />

characterized him as follows:<br />

Slight of build, but well-knit, fresh of face,<br />

hair slightly gray, mind alert and exceptionally<br />

well-informed, quick and enthusiastic in<br />

speech, strong in his opinions, shrewd,<br />

warm-hearted , and wholly devoted to his<br />

work-there you have an impressionistic<br />

picture of Reverend Lawrence Skey, M.A 27<br />

His popularity among his parishioners<br />

seems to have been unbounded. Skey served<br />

as an army chaplain in the First World<br />

War, and his flock welcomed him back from<br />

the front with an elaborate celebration on<br />

December 5, 1918. The musical program<br />

leaves no doubt about the feelings of the<br />

18<br />

JSSAC I JSEAC 30 > N' 1 > 200 5

P ETER C OFFMAN > ANALYSI S I ANA LYSE<br />

FIG. R. REV. LAWRENCE SKEY<br />

FIG. 9. ST. GEORGE'S ANGLICAN CATHEDRAL, KINGSTON, BY VARIO US ARCHITECTS (1825-1899) 1 PETE R COff MAN<br />

congregation for the Reverend Captain<br />

Lawrence Skey. To the tune of "Marching<br />

Through Georgia," they sang of how Skey<br />

had single-handedly won the war:<br />

Don't you all remember w hen he went<br />

to do his bit<br />

We all prophesied the huns would<br />

surely have a fit<br />

Hindy and the Kaiser, Little Willy<br />

all have quit<br />

Let's give a cheer for the Re ctor. 28<br />

Later, this verse rang out (to the tune of<br />

"When Johnny Comes Marching Home"):<br />

They say that when he got to France,<br />

Th ey do. Hurrah I<br />

The Kaiser said: "We haven't a chance,"<br />

He did. Hurrahl<br />

If he is only a chaplain, Gee I<br />

What must the regular soldiers be-<br />

Ach himmell Donnervetterl It's all<br />

off mit me. 29<br />

Had Skey suggested that they worship in<br />

an outhouse, he would probably have won<br />

the instant, wholehearted agreement of<br />

his flock. One doesn't generally win that<br />

kind of following by being an indecisive<br />

ditherer, so it comes as no surprise that<br />

Skey was not. Another newspaper clipping<br />

in the Anglican archive, unfortunately<br />

undated, tells of an occasion when Skey<br />

learned that a man in his church neighbourhood<br />

was in the habit of beating his wife.<br />

Skey paid the man a visit, and, finding<br />

him obstinate in the face of reasonable<br />

persuasion, determined to settle the<br />

matter once and for all:<br />

"Take off your coat," cried Mr. Skey, removing<br />

his own. Dumbly, the husband obeyed, and<br />

the fighting parson started at him. It was a<br />

fair fight, with no one to interfere. It lasted<br />

several minutes, but in the end the minister<br />

had "licked" his man. Mr. Skey came out of<br />

the fight with a black eye, but that worried<br />

him nothing at all. 30<br />

Whether that anecdote is true is less<br />

important than the fact that it was<br />

circulated. Moreover, Skey's feisty streak<br />

did not extend only to the weak and the<br />

drunk. In 1923, he held a special service to<br />

celebrate the completion of the decoration<br />

of St. Anne's. To mark the occasion, he invited<br />

one Rev. Pidgeon (a Methodist) and<br />

one Rev. MacNeill (a Baptist) to share his<br />

pulpit. Skey's bishop (Sweeney). in turn,<br />

marked the occasion by informing Skey<br />

that under no circumstances was he to<br />

share his pulpit with such company. Skey<br />

being Skey, he followed his convictions<br />

and ignored his boss. "I was glad," he reflected<br />

later, "that I stood by my principles<br />

in the matter." He then added a thought<br />

that could serve as his epitaph: "One must<br />

learn to defy opposition.""<br />

Such lack of regard for the approval of<br />

others-even of one's own superiors-was<br />

doubtless a useful trait for anyone planning<br />

to build a Byzantine Anglican church<br />

in Toronto in 1907. After the opening service<br />

of 1908, the Canadian Churchman<br />

summarized the resistance to Skey's new<br />

church :<br />

When this church w as in the course of<br />

erection many and various were the remarks<br />

made upon it, and many of them were far<br />

from flattering . Mosque, cyclorama and<br />

synagogue were among the most common<br />

JSSAC I JSEAC 30 > N• 1 > 200 5<br />

19

P ETER COFFMAN > ANALYSIS I ANALYSE<br />

FIG. 10. ST. ANNE'S ANGLICAN CHURCH, J.E.H. MACDONALD'S ORIGINAL<br />

DECORATIVE SCHEME.<br />

and frequent epithets used, and, judged<br />

from the exterior view, having a dome as the<br />

main feature, it has of necessity a certain<br />

outward resemblance to the synagogue<br />

of the Jew, and no one is blamed fo r not<br />

altogether liking the external appearance. 32<br />

The writer does, however, make an<br />

attempt to defend Skey's church :<br />

The objections that have been made that<br />

it is contrary to church architecture are,<br />

of course, only made by the ignorant, for<br />

there is no rule or law that Gothic is the only<br />

type for Anglican churches. St. George's<br />

Cathedral, Kingston, is of the same [Greek or<br />

Byzantine] type, and though, like St. Anne's,<br />

many do not admire it from without, there<br />

are few who would not admit that when you<br />

enter in you find one of the most beautiful<br />

churches in our country. 33<br />

Several architectural and historical facts<br />

are muddled in that account: St. Anne's is<br />

Byzantine, not Greek; and Byzantine had,<br />

for 1300 years, been a Christian style only<br />

recently used in synagogues. The St. George's<br />

Cathedral referred to is not Byzantine<br />

(fig. 9), and has, in Wren's St. Paul's Ca <br />

thedral, London (begun 1675), as mainstream<br />

a lineage as one can wish for in the<br />

Anglican Church . 34 The claim that there<br />

was "no rule or law" that Anglican churches<br />

had to be Gothic, while technically<br />

true, displays remarkable ignorance the<br />

Ecclesiological Society and the very long<br />

shadow they had<br />

cast on Anglican<br />

church building.<br />

But perhaps more<br />

revea I i ng than<br />

the art historical FIG . 11 . ST. ANNE'S ANGLICAN CHURCH , INTERIOR I PETER COFFMAN<br />

mistakes is the assumption<br />

that identifying an architectu- J.E .H. MacDonald is famed as a founding<br />

ral precedent somehow made St. Anne's member of the Group of Seven . On the faacceptable.<br />

The need to find authority in ce of it, a more unlikely candidate for the<br />

historical precedent is a distinctly ecclesiological<br />

way of thinking, and one probably liturgical art in Canadian history would<br />

most ambitious programme of Anglican<br />

not shared by Skey. Despite the efforts be difficult to find. MacDonald had never<br />