to download - International Classical Artists

to download - International Classical Artists

to download - International Classical Artists

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

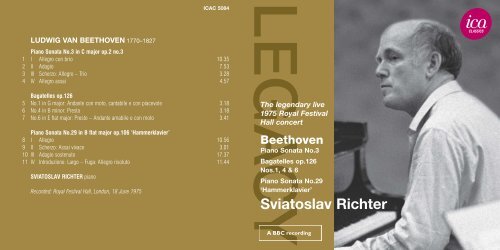

ICAC 5084<br />

LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN 1770–1827<br />

Piano Sonata No.3 in C major op.2 no.3<br />

1 I Allegro con brio 10.35<br />

2 II Adagio 7.53<br />

3 III Scherzo: Allegro – Trio 3.28<br />

4 IV Allegro assai 4.57<br />

Bagatelles op.126<br />

5 No.1 in G major: Andante con mo<strong>to</strong>, cantabile e con piacevole 3.18<br />

6 No.4 in B minor: Pres<strong>to</strong> 3.18<br />

7 No.6 in E flat major: Pres<strong>to</strong> – Andante amabile e con mo<strong>to</strong> 3.41<br />

Piano Sonata No.29 in B flat major op.106 ‘Hammerklavier’<br />

8 I Allegro 10.56<br />

9 II Scherzo: Assai vivace 3.01<br />

10 III Adagio sostenu<strong>to</strong> 17.37<br />

11 IV Introduzione: Largo – Fuga: Allegro risolu<strong>to</strong> 11.44<br />

SVIATOSLAV RICHTER piano<br />

Recorded: Royal Festival Hall, London, 18 June 1975<br />

The legendary live<br />

1975 Royal Festival<br />

Hall concert<br />

Beethoven<br />

Piano Sonata No.3<br />

Bagatelles op.126<br />

Nos.1, 4 & 6<br />

Piano Sonata No.29<br />

‘Hammerklavier’<br />

Svia<strong>to</strong>slav Richter

RICHTER PLAYS BEETHOVEN: THE 1975<br />

ROYAL FESTIVAL HALL RECITAL<br />

‘Pianist of the century’ is a phrase often used <strong>to</strong> describe<br />

Svia<strong>to</strong>slav Richter (1915-97) and not without reason.<br />

Bravura technique matched <strong>to</strong> high intelligence and a<br />

richly developed musical imagination is a rare combination<br />

of qualities in any instrumentalist.<br />

As a pianist, Richter was largely self-taught, albeit from<br />

within the confines of a deeply musical family. It was only<br />

after working as a répétiteur at the Odessa Opera that he<br />

travelled <strong>to</strong> Moscow <strong>to</strong> present himself <strong>to</strong> the great pianist<br />

and pedagogue Heinrich Neuhaus. Neuhaus recalled: ‘A<br />

young man arrived, tall, thin, fair-haired and blue-eyed. His<br />

face was alert and incredibly intense. He sat down at the<br />

piano, placed his long supple and powerful hands over the<br />

keys and began <strong>to</strong> play. His style of playing was reserved,<br />

simple, austere. The extraordinary musical perception that<br />

he showed won me over from the outset.’<br />

Life was not easy for Richter in Stalin’s Soviet Union. In<br />

1941 the Soviets shot his revered German-born musician<br />

father. Nor was there any quick escape. Richter was not<br />

heard in the West until 1960, five years after fellow<br />

Neuhaus pupil Emil Gilels who <strong>to</strong>ld an ecstatic American<br />

public: ‘Wait until you hear Richter!’.<br />

The piece with which the forty-five-year-old Richter<br />

introduced himself <strong>to</strong> the New York public was Beethoven’s<br />

Piano Sonata No.3 in C major, op.2 no.3. This was no<br />

inconsequential warm-up act but a powerful statement of<br />

intent, as indeed is the work itself. Completed in 1795 and<br />

dedicated <strong>to</strong> Beethoven’s teacher Haydn, the three op.2<br />

sonatas are the opening salvos in a sequence of thirty-two<br />

piano sonatas which over three decades would run<br />

alongside Beethoven’s nine symphonies and sixteen string<br />

quartets like a parallel mountain range.<br />

2<br />

The op.2 sonatas were deliberately laid out on a<br />

symphonic scale, in four richly developed movements<br />

rather than the more usual three. Argued with passion and<br />

precision, and with a fine epigrammatic wit, each sonata<br />

covers a vast range of thought and feeling. Technically they<br />

are far from easy. Beethoven was the leading keyboard<br />

virtuoso of the age in Vienna in the 1790s and was<br />

determined <strong>to</strong> exploit the fact in these sonatas.<br />

Richter recognised and relished every jot and tittle of<br />

the young Titan’s achievement here. In his diaries, he<br />

recalls hearing a recording by Artur Schnabel of another<br />

early Beethoven sonata, op.10 no.1. ‘I was literally<br />

as<strong>to</strong>unded by this remarkable interpretation. The sonata is<br />

suddenly brought <strong>to</strong> life <strong>to</strong> the point where it’s almost<br />

palpable. It was splendid.’ Much the same could be said of<br />

this 1975 London performance of op.2 no.3.<br />

Between 1802 and 1816 Beethoven wrote no piano<br />

sonatas in the full four-movement form. The return <strong>to</strong> the<br />

form came with the sonatas opp.101 and 106, which in a<br />

sudden access of patriotism he described as being written for<br />

the ‘Hammerklavier’, the old German word for the pianoforte<br />

as opposed <strong>to</strong> harpsichord. In the event, the sobriquet stuck<br />

<strong>to</strong> op.106, which is not so much the Mount Everest among<br />

piano sonatas as the Mount Etna, so full of fire and wrath it is.<br />

The sonata was completed in 1819 and dedicated <strong>to</strong><br />

the Archduke Rudolf. It was a difficult time for Beethoven<br />

as he approached his fiftieth year. Litigation over his<br />

adopted nephew Karl, deep financial problems, and the<br />

vanishing of all hope where his deafness was concerned<br />

evinced not despair but that mix of anger, exultation and<br />

deep prayerfulness which characterises all the mighty<br />

works of this period: the Missa solemnis, the Ninth<br />

Symphony and the ‘Hammerklavier’ itself. Glorious <strong>to</strong> hear,<br />

all are creations which test musical technique and human<br />

resolve <strong>to</strong> the edge of destruction.<br />

The mood of the opening of the ‘Hammerklavier’ is one<br />

of open defiance and in the finale there is an anger that<br />

barely abates. Yet at the heart of the sonata lies an<br />

eighteen-minute slow movement which is plainly religious<br />

in character. Richter once remarked of the slow movement<br />

of the early op.7 Piano Sonata: ‘Beethoven seems <strong>to</strong> be<br />

communing with our Lord and affirming His existence.’<br />

This is even more palpable in the ‘Hammerklavier’ as<br />

Beethoven sublimates and transforms in<strong>to</strong> visionary art the<br />

anguish of the two opening movements. Not that the<br />

sonata’s more ferocious movements are at all reckless<br />

artistically. As Richter’s performance vividly attests, the<br />

‘Hammerklavier’ is from first note <strong>to</strong> last a work of<br />

extraordinary lucidity and clear-sightedness.<br />

Richter played this carefully crafted programme, in<br />

which the C major sonata is the proud herald of greater<br />

things <strong>to</strong> come, a good deal during 1975. The<br />

‘Hammerklavier’ was the work public flocked <strong>to</strong> hear but<br />

the entire recital merits close attention, not least the three<br />

op.126 Bagatelles which Richter deployed as a teasing<br />

pre-interval glimpse of Beethoven’s late mood. These<br />

aphoristic miniatures, Beethoven’s last significant music<br />

for the piano, are less concerned with process – with the<br />

business of becoming – than with the distillation of an<br />

image and the consecration of a mood. There are vestiges<br />

here of Beethoven’s old Promethean self. But at the outset<br />

of the first Bagatelle, in the strangely persistent trio section<br />

of the fourth and at the heart of the sixth we experience<br />

intimations of a deep inner calm: glimpses of a Great Good<br />

Place beyond the stir of worldly events.<br />

Richard Osborne<br />

3<br />

RICHTER JOUE BEETHOVEN : RÉCITAL<br />

DU ROYAL FESTIVAL HALL DE 1975<br />

On évoque souvent, non sans raison, Svia<strong>to</strong>slav<br />

Richter (1915–1997) comme le “pianiste du siècle”.<br />

Il possédait un ensemble de qualités plutôt rare pour un<br />

instrumentiste : une technique virtuose, une intelligence<br />

supérieure, et une imagination musicale largement<br />

développée.<br />

Bien qu’il soit issu d’une famille profondément<br />

musicienne, Richter était un pianiste largement<br />

au<strong>to</strong>didacte. C’est seulement après avoir travaillé comme<br />

répétiteur à l’Opéra d’Odessa qu’il se rendit à Moscou pour<br />

se présenter au grand pianiste et pédagogue Heinrich<br />

Neuhaus, qui l’évoqua ainsi par la suite : “Un jeune<br />

homme est arrivé, grand, fin, avec des cheveux blonds et<br />

des yeux bleus. Son visage était vif et incroyablement<br />

concentré. Il s’assit au piano, plaça ses longues mains<br />

souples et puissantes sur le clavier et il commença à<br />

jouer. Son style de jeu était réservé, simple, austère.<br />

L’extraordinaire compréhension musicale qu’il manifestait<br />

me convainquit dès le début.”<br />

La vie n’était pas facile pour Richter dans l’Union<br />

Soviétique stalinienne. En 1941, les Soviets fusillèrent son<br />

père vénéré, un musicien d’origine allemande. Il n’y avait<br />

pas de fuite rapide possible. On n’entendit pas Richter à<br />

l’Ouest avant 1960, cinq ans après Emil Guilels, son<br />

compagnon d’étude chez Neuhaus, qui affirma un jour à un<br />

public américain en extase : “Attendez d’entendre Richter!”<br />

A l’âge de quarante-cinq ans, Richter se présenta au<br />

public new-yorkais avec la Sonate pour piano n o 3 en<br />

ut majeur op.2 n o 3 de Beethoven. Ce n’était pas un<br />

échauffement anecdotique mais une puissante déclaration<br />

d’intention, comme l’est en fait l’œuvre elle-même.<br />

Achevées en 1795 et dédiées à Haydn, le professeur de

Beethoven, les trois Sonates op.2 sont les premières<br />

salves d’une série de trente-deux sonates pour piano qui<br />

ont accompagné sur trois décennies les neuf symphonies<br />

et les seize quatuors à cordes de Beethoven comme une<br />

chaîne de montagnes parallèle.<br />

Les Sonates op.2 ont été délibérément conçues à une<br />

échelle symphonique, en quatre mouvements richement<br />

développés plutôt que dans forme en trois mouvements<br />

plus usuelle. Développée avec passion et précision, et<br />

avec un admirable esprit épigrammatique, chaque sonate<br />

recouvre une vaste étendue de pensées et de sentiments.<br />

Techniquement, elles sont loin d’être faciles. Beethoven<br />

était le principal virtuose du clavier à Vienne dans les<br />

années 1790, et il était déterminé à exploiter la virtuosité<br />

dans ces sonates.<br />

Ici, Richter souligne chaque iota et se délecte de la<br />

réalisation du jeune Titan. Dans son journal, il se rappelle<br />

avoir entendu l’enregistrement par Artur Schnabel de la<br />

Sonate op.10 n o 1, l’une des premières sonates de Beethoven.<br />

“J’étais littéralement abasourdi par cette interprétation<br />

remarquable. La sonate prenait soudainement vie au<br />

point qu’elle en était presque palpable. C’était splendide.”<br />

On pourrait pratiquement dire la même chose de cette<br />

interprétation londonienne de la Sonate op.2 n o 3 qui date<br />

de 1975.<br />

Entre 1802 et 1816 Beethoven n’écrivit plus aucune<br />

sonate pour piano en quatre mouvements. Le re<strong>to</strong>ur à cette<br />

forme ne vint qu’avec les Sonates opp. 101 et 106 qui, par<br />

un soudain accès de patriotisme de leur auteur, portent<br />

l’indication “pour le Hammerklavier”, l’ancien mot<br />

allemand désignant le pianoforte par opposition au<br />

clavecin. Finalement, l’indication resta collée à la<br />

Sonate op.106, qui n’est pas tant le Mont Everest<br />

des sonates pour piano que le Mont Etna, en raison de<br />

ses élans enflammés et de ses grondements de colère.<br />

La sonate fut terminée en 1819 et dédiée à l’archiduc<br />

Rodolphe. A l’approche de son cinquantième anniversaire,<br />

Beethoven vivait une période difficile. Le litige sur<br />

l’adoption de son neveu Karl, d’importants problèmes<br />

financiers et l’abandon de <strong>to</strong>ut espoir en ce qui concerne<br />

sa surdité se traduisirent non pas par un désespoir, mais<br />

par un mélange de colère, de jubilation et un esprit de<br />

prière profonde caractéristiques de <strong>to</strong>utes ses grandes<br />

œuvres de cette période : la Missa solemnis, la<br />

Neuvième Symphonie et la Sonate “Hammerklavier”<br />

elle-même. Merveilleuses à écouter, ce sont <strong>to</strong>utes<br />

des créations qui mettent à l’épreuve la technique<br />

musicale et la détermination humaine jusq’au seuil de<br />

la destruction.<br />

L’atmosphère du début de la Sonate “Hammerklavier”<br />

est un défi ouvert, et dans le finale il y a une fureur qui<br />

ne faiblit presque pas. Cependant, au centre de la sonate,<br />

il y a un mouvement lent de dix-huit minutes au caractère<br />

clairement religieux. Evoquant le mouvement lent de la<br />

Sonate pour piano op.7, Richter fit remarquer un jour que<br />

“Beethoven semble communier avec le Seigneur et<br />

affirmer son existence.” Cela est encore plus palpable dans<br />

la Sonate “Hammerklavier” car Beethoven sublime et<br />

transforme en art visionnaire l’anxiété des deux premiers<br />

mouvements. Ce qui n’empêche pas les mouvements<br />

les plus agités d’être audacieux sur le plan artistique.<br />

Comme l’atteste l’interprétation éclatante de Richter, la<br />

Sonate “Hammerklavier” est, de la première à la dernière<br />

note, une œuvre d’une lucidité et d’une clairvoyance<br />

extraordinaires.<br />

Au cours de l’année 1975, Richter a joué un grand<br />

nombre de fois ce programme soigneusement agencé,<br />

dans lequel la Sonate en ut majeur annonce fièrement de<br />

plus grandes choses à venir. La Sonate “Hammerklavier”<br />

était l’œuvre que le public s’empressait d’aller écouter,<br />

mais le récital entier mérite <strong>to</strong>ute notre attention, et<br />

notamment les trois Bagatelles de l’opus 126 que Richter<br />

a déployées comme un aperçu annonciateur du climat du<br />

dernier Beethoven. Ces miniatures aphoristiques, dernières<br />

pièces importantes pour piano de Beethoven, sont moins<br />

affectées par les aspects de construction formelle que par<br />

la distillation d’une image et la recherche d’une<br />

atmosphère. On trouve ici des vestiges du vieux Prométhée<br />

beethovénien lui-même. Mais, au début de la première<br />

Bagatelle, dans l’étrange trio répété de la quatrième et au<br />

centre de la sixième, on ressent un calme intérieur<br />

profond, aperçu d’un havre idéal au-delà de l’agitation des<br />

événements terrestres.<br />

Richard Osborne<br />

Traduction : Jean-Jacques Velly<br />

4 5<br />

RICHTER SPIELT BEETHOVEN: DAS ROYAL<br />

FESTIVAL HALL RECITAL 1975<br />

“Pianist des Jahrhunderts” ist eine Phrase, die oft und<br />

nicht unbegründet benutzt wird, um Swja<strong>to</strong>slaw Richter<br />

(1915–1997) zu beschreiben. Bravouröse Technik<br />

gekoppelt mit gleichermaßen hoher Intelligenz und reich<br />

entwickelter musikalischer Einfallskraft ist eine seltene<br />

Kombination von Qualitäten in einem Instrumentalisten.<br />

Als Pianist war Richter vorwiegend Au<strong>to</strong>didakt, wenn<br />

auch innerhalb einer äußerst musikalischen Familie. Erst<br />

nachdem er als Korrepeti<strong>to</strong>r an der Oper Odessa gearbeitet<br />

hatte, ging er nach Moskau, um sich dem großen Pianisten<br />

und Pädagogen Heinrich Neuhaus vorzustellen. Neuhaus<br />

erinnert sich: “Ein junger Mann erschien, groß, schlank,<br />

blond und blauäugig. Sein Gesicht war aufgeschlossen und<br />

unglaublich intensiv. Er setzte sich ans Klavier, setzte seine<br />

langen, geschmeidigen und unglaublich starken Hände auf<br />

die Tasten und begann zu spielen. Sein Stil war reserviert,<br />

schlicht und streng. Die außerordentliche musikalische<br />

Einsicht, die er aufwies, überzeugte mich sogleich.”<br />

Das Leben in Stalins Sowjetunion war nicht leicht für<br />

Richter. 1941 erschossen die Sowjets seinen verehrten<br />

deutschen Musikervater. Es gab auch keine schnelle<br />

Ausflucht. Richter war erst 1960 zum ersten Mal im<br />

Westen zu hören, fünf Jahre nach Emil Gilels, sein<br />

Studienkollege bei Neuhaus, der zu seinem ekstatischen<br />

amerikanischen Publikum sagte: “Warten Sie, bis Sie<br />

Richter hören!”<br />

Das Stück, mit dem sich der 45-jährige Richter der<br />

New Yorker Öffentlichkeit vorstellte, war Beethovens<br />

Klaviersonate Nr. 3 C-dur, op. 2, Nr. 3. Dies war kein<br />

belangloser Aufwärmakt, sondern eine kraftvolle<br />

Absichtserklärung wie das Werk selbst. Die drei 1795<br />

vollendeten und Beethovens Lehrer Haydn gewidmeten

Sonaten op. 2 sind die Auftaktssalven für seine 32<br />

Sonaten, die er in den nächsten drei Jahrzehnten wie<br />

ein Nachbargebirge neben seinen neun Sinfonien und<br />

sechzehn Streichquartetten errichten sollte.<br />

Die Sonaten op. 2 wurden absichtlich nach<br />

sinfonischen Maßstäben in vier intensiv verarbeiteten<br />

Sätzen statt der üblicheren drei angelegt. Jede Sonate<br />

wird mit Leidenschaft und Präzision und feinem<br />

epigrammatischen Sinn durchgeführt und befasst sich mit<br />

einer weiten Bandbreite von Gedanken und Gefühlen.<br />

Technisch sind sie alles andere als leicht. Beethoven war<br />

in den 1790er Jahren in Wien der führende Klaviervirtuose<br />

seiner Zeit und entschlossen, sich diese Tatsache in<br />

diesen Sonaten zunutze zu machen.<br />

Richter erkannte und genoss hier jede Facette der<br />

Errungenschaften des jungen Titanen. In seinen<br />

Tagebüchern erinnert er sich an eine Aufnahme einer<br />

anderen frühen Beethoven-Sonate, op. 10, Nr. 1, von<br />

Artur Schnabel. “Ich war buchstäblich von dieser<br />

bemerkenswerten Aufnahme überwältigt. Die Sonate wird<br />

plötzlich so lebendig, dass sie fast greifbar wird. Es war<br />

herrlich.” Ähnliches könnte man über seine Aufführung<br />

von op. 2, Nr. 3 in London 1975 sagen.<br />

Zwischen 1802 und 1816 schrieb Beethoven keine<br />

Klaviersonaten in der vollen viersätzigen Form. Die<br />

Wiederkehr zu dieser Form folgte mit den Sonaten<br />

opp. 101 und 106, die er plötzlich patriotisch als “für das<br />

Hammerklavier” beschrieb – das alte deutsche Wort<br />

für das Pianoforte im Gegensatz zum Cembalo. Dieser<br />

Beiname haftete schließlich op. 106 an, die mit ihrem<br />

Feuer und Zorn in den Gefilden der Sonate eher den Ätna<br />

als den Everest repräsentiert.<br />

Die Sonate wurde 1819 vollendet und Erzherzog Rudolf<br />

gewidmet. Es war eine schwere Zeit für Beethoven, als er<br />

sich seinem 50. Lebensjahr näherte. Ein Gerichtsverfahren<br />

über seinen Adoptivneffen Karl, schwere Finanznöte und<br />

die hoffnungslose Situation seiner Ertaubung brachten aber<br />

nicht Verzweiflung sondern die charakteristische Mischung<br />

von Zorn, Jubel und tiefer Andächtigkeit mit sich, die alle<br />

gewaltigen Werke dieser Periode auszeichnet: die Missa<br />

solemnis, die Neunte Sinfonie und die “Hammerklavier”-<br />

Sonate selbst. Diese glorreich anzuhörenden Schöpfungen<br />

stellen musikalische Technik und menschliche<br />

Entschlossenheit bis zur Grenze der Zerstörung auf die<br />

Probe.<br />

Der Anfang der “Hammerklavier”-Sonate grüßt uns mit<br />

einer Stimmung unverhohlenen Trotzes, und das Finale<br />

drückt eine kaum nachlassende Wut aus. Im Herzen der<br />

Sonate liegt jedoch ein 18 Minuten langer, eindeutig<br />

religiöser langsamer Satz. Richter bemerkte einmal über<br />

die frühe Sonate op. 7, dass “Beethoven mit unserem<br />

Herrn zu kommunizieren und seine Existenz zu bestätigen<br />

scheint”. In der “Hammerklavier”-Sonate tritt dies noch<br />

deutlicher zutage. Beethoven sublimiert und transformiert<br />

die Qualen der ersten beiden Sätze in visionäre Kunst. Das<br />

heißt nicht, dass die wilderen Sätze künstlerisch einfach<br />

nur verwegen sind. Richters Ausführung attestiert lebhaft,<br />

dass die “Hammerklavier”-Sonate von der ersten bis zur<br />

letzten Note ein Werk von außerordentlicher Transparenz<br />

und Klarsicht ist.<br />

Richter spielte 1975 dieses sorgfältig gestaltete<br />

Programm häufig, in dem die C-dur-Sonate als s<strong>to</strong>lzer<br />

Vorbote größerer Dinge erscheint, die bevorstehen. Das<br />

Publikum kam in Scharen, um die “Hammerklavier”-Sonate<br />

zu hören, aber das gesamte Programm verdient unsere<br />

Aufmerksamkeit, nicht zuletzt die Bagatellen op. 126,<br />

die Richter vor der Pause als lockende Vorspeise auf<br />

Beethovens Spätstimmung spielte. Diese aphoristischen<br />

Miniaturen, Beethovens letzte signifikante Klaviermusik,<br />

beschäftigen sich weniger mit dem Prozess – dem<br />

6<br />

Werdegang – als der Destillation einer Anschauung und<br />

der Hingabe an eine Stimmung. Hier finden sich Spuren<br />

von Beethovens altem prometheischen Selbst. Aber am<br />

Beginn der ersten Bagatelle, dem seltsam beharrlichen<br />

Trio der vierten und im Herzen der sechsten erfahren<br />

wir Anklänge an eine tiefe innere Stille: flüchtige Blicke<br />

auf einen großen, guten Ort jenseits der Aufregungen<br />

weltlichen Geschehens.<br />

Richard Osborne<br />

Übersetzung: Renate Wendel<br />

For a free promotional CD sampler including<br />

highlights from the ICA Classics CD catalogue,<br />

please email info@icaclassics.com.<br />

7<br />

For ICA Classics<br />

Executive Producer/Head of Audio: John Pattrick<br />

Music Rights Executive: Aurélie Baujean<br />

Head of DVD: Louise Waller-Smith<br />

Executive Consultant: Stephen Wright<br />

Remastering: Paul Baily (Re.Sound)<br />

ICA Classics acknowledges the assistance of Milena Boromeo<br />

With special thanks <strong>to</strong> Keith Bennett<br />

Introduc<strong>to</strong>ry note & translations<br />

2012 <strong>International</strong> <strong>Classical</strong> <strong>Artists</strong> Ltd<br />

Booklet editing: WLP Ltd<br />

Art direction: Georgina Curtis for WLP Ltd<br />

2012 BBC, under licence <strong>to</strong> <strong>International</strong> <strong>Classical</strong> <strong>Artists</strong> Ltd<br />

Licensed courtesy of BBC Worldwide<br />

2012 <strong>International</strong> <strong>Classical</strong> <strong>Artists</strong> Ltd<br />

Technical Information<br />

Pyramix software<br />

Yamaha 03D mixing console<br />

CEDAR including Re<strong>to</strong>uch<br />

dCS conver<strong>to</strong>rs<br />

TC Electronic M5000 (digital audio mainframe)<br />

Studer A820 1/4" tape machine with Dolby A noise reduction<br />

ATC 100 active moni<strong>to</strong>rs<br />

Stereo ADD<br />

Sourced from the original master tapes<br />

WARNING:<br />

All rights reserved. Unauthorised copying, reproduction, hiring,<br />

lending, public performance and broadcasting prohibited.<br />

Licences for public performance or broadcasting may be obtained<br />

from Phonographic Performance Ltd., 1 Upper James Street,<br />

London W1F 9DE. In the United States of America unauthorised<br />

reproduction of this recording is prohibited by Federal law and<br />

subject <strong>to</strong> criminal prosecution.<br />

Made in Austria

Also available on CD and digital <strong>download</strong>:<br />

ICAC 5000<br />

Beethoven: Piano Concer<strong>to</strong>s Nos.1 & 3<br />

New Philharmonia Orchestra · Sir Adrian Boult<br />

Emil Gilels<br />

ICAC 5003<br />

Brahms: Piano Concer<strong>to</strong> No.2<br />

Chopin · Falla<br />

Kölner Rundfunk-Sinfonie-Orchester<br />

Chris<strong>to</strong>ph von Dohnányi · Arthur Rubinstein<br />

Gramophone Edi<strong>to</strong>rs’ Choice<br />

ICAC 5007<br />

Tchaikovsky: Symphony No.1 ‘Winter Dreams’<br />

Stravinsky: The Firebird Suite (1945 version)<br />

BBC Symphony Orchestra · Philharmonia Orchestra<br />

Evgeny Svetlanov<br />

ICAC 5008<br />

Liszt: Rhapsodie espagnole<br />

Hungarian Rhapsody No.2<br />

CPE Bach · Couperin · Scarlatti<br />

Georges Cziffra<br />

ICAC 5004<br />

Haydn: Piano Sonata No.62<br />

Weber: Piano Sonata No.3<br />

Schumann · Chopin · Debussy<br />

Svia<strong>to</strong>slav Richter<br />

Diapason d’or<br />

ICAC 5006<br />

Verdi: La traviata<br />

Maria Callas · Cesare Valletti · Mario Zanasi<br />

The Covent Garden Opera Chorus & Orchestra<br />

Nicola Rescigno · Supersonic Award (Pizzica<strong>to</strong> Magazine)<br />

ICAC 5020<br />

Rachmaninov: Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini<br />

Prokofiev: Piano Sonata No.7<br />

Stravinsky: Three Scenes from Petrushka<br />

Kölner Rundfunk-Sinfonie-Orchester · Zdeněk Mácal<br />

Shura Cherkassky<br />

ICAC 5021<br />

Mahler: Symphony No.3 · Debussy: La Mer<br />

Kölner Rundfunkchor · Kölner Domchor<br />

Kölner Rundfunk-Sinfonie-Orchester · Dimitri Mitropoulos<br />

Toblacher Komponierhäuschen <strong>International</strong><br />

Record Prize 2011<br />

8<br />

9

ICAC 5032<br />

Beethoven: Piano Concer<strong>to</strong> No.4<br />

Tchaikovsky: Piano Concer<strong>to</strong> No.2<br />

Hallé Orchestra · Sir John Barbirolli<br />

London Philharmonic Orchestra · Kirill Kondrashin<br />

Emil Gilels<br />

ICAC 5033<br />

Mahler: Symphony No.3<br />

Waltraud Meier · E<strong>to</strong>n College Boys’ Choir<br />

London Philharmonic Choir & Orchestra<br />

Klaus Tennstedt<br />

Choc de Classica · Diapason d’or<br />

ICAC 5047<br />

Mendelssohn: A Midsummer Night’s Dream<br />

Beethoven: Symphony No.8<br />

Kölner Rundfunkchor · Kölner Rundfunk-Sinfonie-Orchester<br />

Ot<strong>to</strong> Klemperer<br />

ICAC 5048<br />

Brahms: Piano Concer<strong>to</strong> No.1<br />

Chopin · Liszt · Schumann · Albéniz<br />

BBC Symphony Orchestra · Rudolf Kempe<br />

Julius Katchen<br />

ICAC 5036<br />

Shostakovich: Symphony No.10<br />

Tchaikovsky · Rimsky-Korsakov<br />

USSR State Symphony Orchestra<br />

Evgeny Svetlanov<br />

ICAC 5045<br />

Chopin: Piano Concer<strong>to</strong> No.1<br />

Beethoven: Piano Concer<strong>to</strong> No.4<br />

Ot<strong>to</strong> Klemperer · Chris<strong>to</strong>ph von Dohnányi<br />

Kölner Rundfunk-Sinfonie-Orchester · Claudio Arrau<br />

Supersonic Award (Pizzica<strong>to</strong> Magazine)<br />

ICAC 5053<br />

Holst: The Planets<br />

Britten: Variations and Fugue on a Theme of Purcell<br />

BBC Symphony Orchestra<br />

Gennadi Rozhdestvensky<br />

ICAC 5054<br />

Beethoven: Missa solemnis<br />

Kölner Rundfunkchor<br />

Kölner Rundfunk-Sinfonie-Orchester<br />

William Steinberg<br />

10<br />

11

ICAC 5055<br />

Schubert: Impromptu in B flat<br />

Beethoven: Piano Sonatas Nos. 6 & 29<br />

Wilhelm Backhaus<br />

ICAC 5061<br />

Verdi: Falstaff<br />

Fernando Corena · Anna Maria Rovere · Fernanda Cadoni<br />

Glyndebourne Opera Chorus<br />

Royal Philharmonic Orchestra<br />

Carlo Maria Giulini<br />

ICAC 5068<br />

Verdi: Requiem · Rossini: Overtures<br />

Moscow Philharmonic Orchestra<br />

Orchestre National de l’ORTF<br />

Igor Markevitch<br />

ICAC 5069<br />

Rachmaninov: The Bells<br />

Prokofiev: Alexander Nevsky<br />

BBC Symphony Chorus and Orchestra<br />

Philharmonia Chorus and Orchestra<br />

Evgeny Svetlanov<br />

ICAC 5062<br />

Schumann: Piano Concer<strong>to</strong><br />

Beethoven: Eroica Variations · Piano Sonata No.30<br />

Kölner Rundfunk-Sinfonie-Orchester · Joseph Keilberth<br />

Annie Fischer<br />

ICAC 5063<br />

Brahms: Symphony No.3<br />

Elgar: Symphony No.1<br />

BBC Symphony Orchestra<br />

Sir Adrian Boult<br />

Supersonic Award (Pizzica<strong>to</strong> Magazine)<br />

ICAC 5075<br />

Berlioz: Requiem<br />

Nicolai Gedda<br />

Kölner Rundfunkchor<br />

Kölner Rundfunk-Sinfonie-Orchester<br />

Dimitri Mitropoulos<br />

ICAC 5076<br />

Wolf: Italienisches Liederbuch<br />

Janet Baker · John Shirley-Quirk<br />

Steuart Bedford<br />

12<br />

13

ICAC 5077<br />

Brahms: Piano Concer<strong>to</strong> No.2<br />

Debussy · Prokofiev<br />

Kölner Rundfunk-Sinfonie-Orchester<br />

Mario Rossi<br />

Emil Gilels<br />

ICAC 5078<br />

Rachmaninov: Symphony No.2<br />

Bernstein: Candide – Overture<br />

Philharmonia Orchestra<br />

London Symphony Orchestra<br />

Evgeny Svetlanov<br />

ICAC 5081<br />

Schumann: Symphony No.4<br />

Debussy: Le Martyre de Saint Sébastien – Suite<br />

Philharmonia Orchestra<br />

Guido Cantelli<br />

ICAC 5085<br />

Chopin: Piano Concer<strong>to</strong>s Nos. 1 & 2<br />

BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra · Chris<strong>to</strong>pher Adey<br />

BBC Symphony Orchestra · Richard Hickox<br />

Shura Cherkassky<br />

ICAC 5079<br />

Grieg · Liszt: Piano Concer<strong>to</strong>s<br />

Lully · Scarlatti<br />

Orchestre National de l’ORTF<br />

Georges Tzipine · André Cluytens<br />

Georges Cziffra<br />

ICAC 5080<br />

Mahler: Das klagende Lied<br />

Janáček: The Fiddler’s Child<br />

Teresa Cahill · Janet Baker · Robert Tear · Gwynne Howell<br />

BBC Symphony Chorus and Orchestra<br />

Gennadi Rozhdestvensky<br />

ICAC 5086<br />

Beethoven: Piano Concer<strong>to</strong>s Nos. 2 & 4<br />

Sinfonia Varsovia<br />

Jacek Kaspszyk<br />

Ingrid Jacoby<br />

ICAC 5087<br />

Beethoven: Symphony No.3 ‘Eroica’<br />

Smetana: The Bartered Bride – Overture<br />

Orquesta Nacional de España · Orchestre de<br />

la Suisse Romande · Gran Orquesta Sinfónica<br />

Ataúlfo Argenta<br />

14<br />

15