to download - International Classical Artists

to download - International Classical Artists

to download - International Classical Artists

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

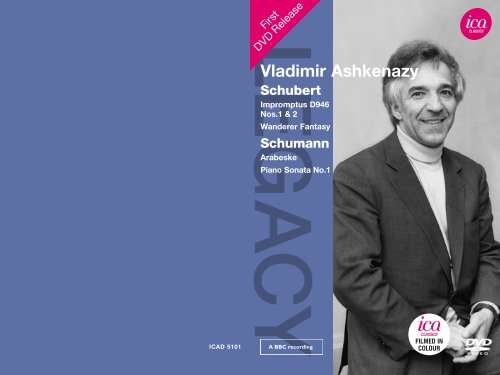

First<br />

DVD Release<br />

Vladimir Ashkenazy<br />

Schubert<br />

Impromptus D946<br />

Nos.1 & 2<br />

Wanderer Fantasy<br />

Schumann<br />

Arabeske<br />

Piano Sonata No.1<br />

ICAD 5101<br />

FILMED IN<br />

COLOUR

1 Introduction <strong>to</strong> ICA Classics 2.57<br />

FRANZ SCHUBERT 1797–1828<br />

Impromptus D946<br />

2 No.1 in E flat minor 11.05<br />

3 No.2 in E flat major 10.27<br />

Fantasia in C major D760 ‘Wanderer Fantasy’<br />

4 I Allegro con fuoco ma non troppo – 6.12<br />

5 II Adagio – 6.28<br />

6 III Pres<strong>to</strong> – 4.43<br />

7 IV Allegro – 4.05<br />

ROBERT SCHUMANN 1810–1856<br />

8 Arabeske in C major op.18 7.06<br />

For a free promotional DVD sampler including highlights from the<br />

ICA Classics DVD catalogue, please email info@icaclassics.com.<br />

For ICA Classics<br />

Executive Producer: Stephen Wright<br />

Head of DVD: Louise Waller-Smith<br />

Music Rights and Production Executive: Aurélie Baujean<br />

Executive Consultant: John Pattrick<br />

ICA Classics gratefully acknowledges the assistance of Mark Pickering<br />

DVD Production<br />

DVD Production and Packaging: WLP Ltd<br />

Introduc<strong>to</strong>ry Note & Translations © 2013 <strong>International</strong> <strong>Classical</strong> <strong>Artists</strong> Ltd<br />

Cover Pho<strong>to</strong>: © Neville Marriner/Associated Newspapers/Rex Features<br />

Art Direction: Georgina Curtis for WLP Ltd<br />

2013 BBC, under licence <strong>to</strong> <strong>International</strong> <strong>Classical</strong> <strong>Artists</strong> Ltd<br />

Licensed courtesy of BBC Worldwide<br />

The sound on this DVD has been improved with Enhanced Mono. During the remastering of this original mono programme, the audio<br />

signal has been res<strong>to</strong>red <strong>to</strong> give a wider and more open sound which, though not equivalent <strong>to</strong> a stereo recording, improves the quality<br />

of the original source and provides a richer sound experience.<br />

Piano Sonata No.1 in F sharp minor op.11<br />

9 I Introduzione: Un poco adagio – Allegro vivace 10.42<br />

10 II Aria: Senza passione, ma espressivo 3.18<br />

11 III Scherzo: Allegrissimo – Intermezzo: Len<strong>to</strong>. Alla burla, ma pomposo 5.07<br />

12 IV Finale: Allegro un poco maes<strong>to</strong>so 10.50<br />

VLADIMIR ASHKENAZY piano<br />

Series Producer: Keith Alexander<br />

Producer/Direc<strong>to</strong>r: Hilary Boulding<br />

Recorded: Studio A, Glasgow, 22 June 1987<br />

Broadcast: Music in Camera: Ashkenazy Plays Schubert, 1 November 1987 (Schubert);<br />

Music in Camera: Ashkenazy Plays Schumann, 8 November 1987 (Schumann)<br />

A BBC TV Production in association with Harrison & Parrott Productions<br />

and Polyphon Film und Fernseh GmbH<br />

With thanks <strong>to</strong> Sandra Funk (Funk Productions)<br />

© BBC 1987<br />

Vladimir Ashkenazy is an exclusive artist of Decca Music Group Limited<br />

ICA CLASSICS is a division of the management agency <strong>International</strong> <strong>Classical</strong> <strong>Artists</strong> Ltd (ICA). The label features archive material<br />

from sources such as the BBC, WDR in Cologne and the Bos<strong>to</strong>n Symphony Orchestra, as well as performances from the agency’s own<br />

artists recorded in prestigious venues around the world. The majority of the recordings are enjoying their first commercial release.<br />

The ICA Classics team has been instrumental in the success of many audio and audiovisual productions over the years, including<br />

the origination of the DVD series The Art of Conducting, The Art of Piano and The Art of Violin; the archive-based DVD series<br />

Classic Archive; co-production documentaries featuring artists such as Richter, Fricsay, Mravinsky and Toscanini; the creation of<br />

the BBC Legends archive label, launched in 1998 (now comprising more than 250 CDs); and the audio series Great Conduc<strong>to</strong>rs<br />

of the 20th Century produced for EMI Classics.<br />

WARNING: All rights reserved. Unauthorised copying, reproduction, hiring, lending, public performance and broadcasting<br />

prohibited. Licences for public performance or broadcasting may be obtained from Phonographic Performance Ltd.,<br />

1 Upper James Street, London W1F 9DE. In the United States of America unauthorised reproduction of this recording<br />

is prohibited by Federal law and subject <strong>to</strong> criminal prosecution.<br />

Made in Austria<br />

2<br />

3

VLADIMIR ASHKENAZY AT THE PIANO<br />

Filmed in 1987 for the BBC’s Music in Camera series, this DVD captures Vladimir Ashkenazy at the<br />

piano in an unusually intimate setting. In the BBC’s Glasgow studios in front of an invited audience,<br />

the great Russian-born pianist performs two programmes, each devoted <strong>to</strong> one composer,<br />

respectively Schumann and Schubert. The concerts present his pianistic artistry in his prime and<br />

reveal many of his unique qualities as a solo performer.<br />

Ashkenazy was celebrated as a pianist long before taking up the conduc<strong>to</strong>r’s ba<strong>to</strong>n. Born in Gorky<br />

(now Nizhny Novgorod) in 1937, he began lessons at the age of six and later studied at the Moscow<br />

Conserva<strong>to</strong>ry where his teacher was Lev Oborin. His career was launched in no uncertain terms with<br />

a triumvirate of <strong>to</strong>p awards: second prize at the 1955 <strong>International</strong> Chopin Competition in Warsaw,<br />

first prize at the Queen Elisabeth Music Competition in Brussels a year later and finally joint first,<br />

<strong>to</strong>gether with John Ogdon, at the Tchaikovsky Competition in Moscow in 1962. He entered the latter<br />

under some duress and has spoken of the way that the Soviet culture ministry, infuriated by the<br />

American pianist Van Cliburn’s win at the previous contest, put extra pressure on the Russian<br />

students <strong>to</strong> take part.<br />

It was a year later that Ashkenazy defected from the USSR, <strong>to</strong>gether with his Icelandic wife. The<br />

couple moved first <strong>to</strong> London and later Switzerland. In London during the Sixties, Ashkenazy<br />

established flourishing musical partnerships with his peers of this ‘golden generation’, notably<br />

Daniel Barenboim, Pinchas Zukerman and Zubin Mehta. He did not return <strong>to</strong> Russia until 1989; when<br />

he did so, a camera crew went with him <strong>to</strong> document the experience.<br />

As a pianist, Ashkenazy has never been a barns<strong>to</strong>rmer, often choosing the German and Viennese<br />

classics ahead of overt virtuoso showpieces, with Schubert and Schumann prime among his choices.<br />

His reper<strong>to</strong>ire is nevertheless extensive and varied, encompassing much-loved interpretations of the<br />

works of Chopin and Rachmaninov as well as Bach, Mozart, Beethoven and Shostakovich. During<br />

some fifty years with Decca, he has been one of his instrument’s most prolific recording artists.<br />

He has sometimes expressed frustration with the diminutive size of his hands, and in recent years he<br />

has played less often in public, partly due <strong>to</strong> a problem with arthritis. But his musicianship continues<br />

<strong>to</strong> as<strong>to</strong>nish his audiences and his orchestras alike. He has, over the years, added <strong>to</strong> his roster the<br />

chief conduc<strong>to</strong>rships of the Royal Philharmonic, Philharmonia, NHK, Iceland Symphony Orchestra,<br />

the European Union Youth Orchestra and, since 2009, the Sydney Symphony Orchestra in Australia.<br />

Ashkenazy has always been blessed with an extraordinary facility for absorbing music quickly, but<br />

also a rare humility in the face of his international celebrity. In an interview with me a few years ago,<br />

he commented: ‘Music is an incredible gift from God and nature. I’m only a performer and I don’t<br />

have the creative genius of, for example, Bach or Shostakovich, so I feel extremely humble before<br />

them. It’s my aim <strong>to</strong> be a servant <strong>to</strong> bring this music <strong>to</strong> life.’<br />

He also pointed out the close connections between playing the piano and conducting: ‘It’s a link like<br />

an umbilical cord. For example, on the piano you’re dealing with every register of sound production,<br />

which makes you aware, when you’re conducting, that you must remember every part of the sound<br />

spectrum from bot<strong>to</strong>m <strong>to</strong> <strong>to</strong>p. In the other direction, I’d had the sound of the orchestra in my head<br />

since childhood and always aimed <strong>to</strong> reproduce it when playing the piano.’<br />

Ashkenazy sits high and close <strong>to</strong> the keyboard, eschewing excess movement and gratui<strong>to</strong>us physical<br />

‘projection’; all his energy is focused on the musical content. Here the small-scale BBC studio<br />

enhances his purity of approach, while the camera affords ample opportunity <strong>to</strong> watch the hands (in<br />

his case, amazingly small) of a master pianist at work.<br />

The Schubert recital begins with the first two of the composer’s three late piano pieces D946,<br />

referred <strong>to</strong> sometimes as Impromptus and sometimes as Klavierstücke. Both are sectional, based<br />

around extreme contrasts. No.1 sets a feverish tarantella against inward-looking passages, with rich<br />

chordal textures reminiscent of the composer’s song cycles Winterreise and Schwanengesang. The<br />

second opens with a folksong-like melody which is then contrasted with more unsettling episodes.<br />

Next comes Schubert’s Wanderer Fantasy, a grand-scale sonata in four movements played without a<br />

break. Its core is the melody of the composer’s song Der Wanderer, D493, stated at the start of the<br />

slow movement: ‘Ich bin ein Fremdling überall,’ says the text, a poem by Georg Philipp Schmidt von<br />

Lübeck – ‘I am a stranger everywhere.’ Ashkenazy produces a velvety <strong>to</strong>ne well suited <strong>to</strong> the<br />

lieder-like nature of these works, but he also delves wholeheartedly in<strong>to</strong> the flair of the Wanderer<br />

Fantasy’s opening and its <strong>to</strong>wering final fugue in performances whose outwardly calm aspect is a<br />

cocoon for music-making of impassioned conviction.<br />

The Schumann programme features the much-loved Arabeske op.18, followed by the Sonata No.1 in<br />

F sharp minor op.11. The Arabeske dates from 1839; the fluid unpredictability of its form pointed<br />

forward <strong>to</strong> the experimental structures that Schumann loved <strong>to</strong> explore. Although Schumann’s<br />

metronome mark indicated a swift tempo, many have thought it <strong>to</strong>o fast. Here Ashkenazy takes time<br />

<strong>to</strong> highlight the inner detail of Schumann’s multi-layered writing, focusing likewise on the work’s<br />

poetic ebb and flow.<br />

It is Schumann’s passion for the young pianist Clara Wieck – whose father furiously opposed<br />

their marriage – that underpins the Piano Sonata No.1. He published it anonymously, headed:<br />

‘Piano Sonata. To Clara, from Florestan and Eusebius.’ These two characters represented opposite<br />

sides of his own personality: Florestan extrovert and s<strong>to</strong>rmy, Eusebius gentle, reflective and poetic.<br />

Portions of the sonata can be identified with each, but there is also a link with Clara: in the first<br />

movement Schumann <strong>to</strong>ok a figure from a piano piece that she had composed and combined it<br />

with a theme of his own. If they could not be <strong>to</strong>gether in life, this seemed <strong>to</strong> say, they could be<br />

united in art. Ultimately the couple defied Clara’s father and were married in September 1840.<br />

Ashkenazy highlights the sonata’s contrasts by his variety of <strong>to</strong>ne, rather than by choosing extreme<br />

tempi. His depth and strength of <strong>to</strong>uch evokes the turbulent power of the opening, while the slow<br />

4<br />

5

movement has exceptional delicacy and a sense of spotlit beauty that holds the listener’s<br />

rapt attention.<br />

The early Romanticism of Schubert and Schumann is ideally suited <strong>to</strong> Ashkenazy’s tender-hearted<br />

and self-effacing pianism. These films preserve his ever-rewarding musicianship for a new<br />

generation of music-lovers <strong>to</strong> enjoy.<br />

Jessica Duchen<br />

VLADIMIR ASHKENAZY AU PIANO<br />

Filmé en 1987 pour la série “Music in Camera” de la BBC, ce DVD immortalise Vladimir Ashkenazy<br />

au piano dans un cadre exceptionnellement intime. Enregistré dans les studios de la BBC à Glasgow,<br />

devant un public d’invités, le grand pianiste d’origine russe interprète deux programmes consacrés<br />

chacun à un compositeur, respectivement Schumann et Schubert. Ces concerts montrent son talent<br />

pianistique à son apogée et révèlent nombre de ses qualités de soliste <strong>to</strong>ut à fait remarquables.<br />

Ashkenazy était un pianiste célèbre bien avant de se mettre à la direction d’orchestre. Né à Gorki<br />

(aujourd’hui Nijni Novgorod) en 1937, il commença à prendre des leçons à l’âge de six ans; plus<br />

tard, il étudia au Conserva<strong>to</strong>ire de Moscou sous la houlette du professeur Lev Oborine. Sa carrière<br />

démarra sur les chapeaux de roues par un trio des récompenses les plus prestigieuses : deuxième<br />

prix au Concours <strong>International</strong> Chopin de Varsovie en 1955, premier prix au Concours Reine<br />

Elisabeth de Bruxelles un an plus tard, et enfin premier prix ex aequo avec John Ogdon au Concours<br />

Tchaïkovski de Moscou en 1962. Il s’était inscrit à ce dernier sous la contrainte et a ultérieurement<br />

expliqué la manière dont le Ministre de la culture soviétique, furieux du succès du pianiste américain<br />

Van Cliburn au concours précédent, avait exercé une forte pression sur les étudiants russes pour<br />

qu’ils prennent part à cette édition.<br />

Un an plus tard, Ashkenazy quitta l’URSS avec son épouse, une Islandaise. Le couple s’installa<br />

d’abord à Londres, et ultérieurement en Suisse. Présent à Londres durant les années soixante,<br />

Ashkenazy noua des partenariats musicaux très fructueux avec ses contemporains de la “golden<br />

generation”, notamment Daniel Barenboim, Pinchas Zukerman et Zubin Mehta. Il ne re<strong>to</strong>urna en<br />

Russie qu’en 1989. Lors de son voyage, une équipe de <strong>to</strong>urnage l’accompagna pour<br />

documenter son expérience.<br />

En tant que pianiste, Ashkenazy n’a jamais été un grand frimeur. Il préférait souvent les œuvres<br />

classiques allemandes et viennoises aux pièces de bravoure, Schubert et Schumann figurant en<br />

première place dans ses choix. Son réper<strong>to</strong>ire n’en est pas moins vaste et varié, et comprend des<br />

interprétations très applaudies de Chopin et de Rachmaninov aussi bien que de Bach, Mozart,<br />

Beethoven et Chostakovitch. Au cours des quelque cinquante ans de sa collaboration avec Decca, il<br />

a été l’un des artistes qui a le plus enregistré pour son instrument.<br />

Ashkenazy s’est parfois montré frustré de posséder des mains de petite taille, et les dernières<br />

années, il s’est produit moins souvent en public, en partie à cause de problèmes d’arthrite. Mais sa<br />

musicalité continue à émerveiller son public autant que les orchestres qu’il dirige. Au fil du temps,<br />

il a ajouté à son palmarès la direction musicale du Royal Philharmonic, du Philharmonia, de<br />

l’Orchestre de la NHK, de l’Orchestre symphonique d’Islande, de l’Orchestre des jeunes de l’Union<br />

européenne et, depuis 2009, du Sydney Symphony Orchestra en Australie.<br />

Vladimir Ashkenazy a <strong>to</strong>ujours été doué d’une facilité extraordinaire pour assimiler la musique<br />

rapidement, mais aussi d’une rare humilité face à sa célébrité internationale. Dans une interview<br />

qu’il m’avait accordée il y a quelques années, il avait déclaré : “La musique est un don fabuleux de<br />

Dieu et de la nature. Je ne suis qu’un exécutant et je n’ai pas le génie créatif d’un Bach ou d’un<br />

Chostakovitch, donc je me sens extrêmement humble devant eux. Mon but est d’être un serviteur qui<br />

fasse vivre cette musique.”<br />

Il soulignait aussi les liens étroits entre le jeu au piano et la direction musicale : “C’est un lien<br />

semblable à un cordon ombilical. Par exemple, au piano, vous avez affaire à <strong>to</strong>ute l’étendue de<br />

l’échelle des sons, ce qui vous amène à prendre conscience, quand vous dirigez, que vous devez penser<br />

à chaque partie du spectre sonore, des sons les plus graves aux plus aigus. Dans l’autre sens, j’ai<br />

depuis mon enfance la sonorité de l’orchestre en tête, et j’ai <strong>to</strong>ujours essayé de la reproduire au piano.”<br />

Ashkenazy se tient haut et près du clavier, évitant les mouvements excessifs et la “projection” physique<br />

gratuite; <strong>to</strong>ute son énergie est concentrée sur le contenu musical. Ici, le petit studio de la BBC met en<br />

valeur la pureté de son approche, tandis que le jeu de la caméra offre au spectateur maintes occasions<br />

d’observer les mains – extraordinairement menues – d’un grand maître du piano à l’ouvrage.<br />

Le récital Schubert s’ouvre sur les deux premières des trois pièces pour piano tardives D. 946,<br />

appelées parfois “Impromptus” et parfois “Klavierstücke”. Toutes deux sont construites en plusieurs<br />

sections basées sur des contrastes extrêmes. La première oppose une tarentelle enfiévrée à des<br />

passages introspectifs, avec une texture d’accords très riche, évocatrice des cycles de lieder<br />

Winterreise et Schwanengesang. La deuxième commence par une mélodie d’allure populaire,<br />

contrastée ensuite par des épisodes plus troublants. Vient ensuite la Wanderer-Fantasie, véritable<br />

sonate de grande envergure en quatre mouvements joués sans interruption. Son noyau central est la<br />

mélodie du lied Der Wanderer D. 493, énoncé au début du mouvement lent : “Ich bin ein Fremdling<br />

überall”, “je suis un étranger par<strong>to</strong>ut”, dit le texte, un poème de Georg Philipp Schmidt von Lübeck.<br />

Ashkenazy produit un son velouté qui convient bien au caractère chantant de ces pièces, mais il<br />

s’adonne aussi sans réserve au panache du début de la Wanderer-Fantasie et de sa majestueuse<br />

fugue finale, pour en donner une exécution dont l’apparente tranquillité n’empêche pas une<br />

interprétation musicale d’une conviction passionnée.<br />

Le programme Schumann propose la célèbre Arabesque op. 18, suivie de la Sonate n o 1 en fa dièse<br />

mineur op. 11. L’Arabesque date de 1839; la fluidité imprévisible de sa forme laisse présager les<br />

6 7

structures expérimentales qu’aimait à explorer Schumann. Bien que l’indication métronomique<br />

donnée par Schumann prescrive un tempo enlevé, de nombreux pianistes la trouvent trop rapide.<br />

Dans le cas présent, Ashkenazy prend le temps d’éclairer les détails intimes de l’écriture<br />

polyphonique de Schumann, et met aussi en relief le flux et reflux poétique de l’œuvre.<br />

C’est la passion que Schumann portait à la jeune pianiste Clara Wieck – le père de celle-ci<br />

s’opposait furieusement à leur mariage – qui sous-tend la Sonate pour piano n o 1. Il la publia<br />

anonymement, avec le titre : “Sonate pour piano. Pour Clara, de Florestan et Eusebius.” Ces deux<br />

personnages représentaient les côtés opposés de sa propre personnalité : Florestan extroverti et<br />

fougueux, Eusebius doux, méditatif et poète. Les différentes sections de la sonate peuvent être<br />

identifiées à l’un ou à l’autre, mais il existe aussi un lien avec Clara : au premier mouvement,<br />

Schumann utilise une <strong>to</strong>urnure empruntée à une pièce pour piano qu’elle avait composée et la<br />

combine à un thème de sa propre invention. S’ils ne pouvaient être ensemble dans la vie,<br />

semblaient dire ces motifs, ils pouvaient néanmoins être unis dans l’art. Finalement, le couple brava<br />

l’interdiction du père, et ils se marièrent en septembre 1840. Ashkenazy met en valeur les contrastes<br />

de la sonate par une belle variété de sonorités plutôt qu’en optant pour des tempi extrêmes. La<br />

profondeur et l’intensité de son <strong>to</strong>ucher soulignent la puissance turbulente du début, tandis que le<br />

mouvement lent possède une délicatesse exceptionnelle et une beauté éclatante qui captivent et<br />

ravissent l’auditeur.<br />

Le romantisme naissant de Schubert et de Schumann convient parfaitement au talent pianistique<br />

d’Ashkenazy, sensible et effacé. Ces films se font les témoins, pour que puisse en jouir une nouvelle<br />

génération de mélomanes, d’une musicalité qui méritera <strong>to</strong>ujours l’intérêt.<br />

Jessica Duchen<br />

Traduction : Sophie Liwszyc<br />

VLADIMIR ASHKENAZY AM KLAVIER<br />

Die Aufnahmen auf dieser DVD stammen aus der BBC-Reihe Music in Camera von 1987 und sie<br />

zeigen Vladimir Ashkenazy in einem ungewöhnlich intimen Rahmen am Klavier. Der berühmte, aus<br />

Russland stammende Pianist präsentiert im BBC-Studio in Glasgow vor geladenen Gästen zwei<br />

Programme, die jeweils einem Komponisten gewidmet sind: Schumann und Schubert. Diese<br />

Konzerte zeigen sein pianistisches Können zu Höchstzeiten und bringen viele seiner einzigartigen<br />

Eigenschaften als Solokünstler zum Vorschein.<br />

Ashkenazy war schon lange, bevor er sich dem Dirigieren zuwandte, als Pianist bekannt. Er wurde<br />

1937 in Gorky (heute Nischni Nowgorod) geboren und erhielt ab dem Alter von sechs Jahren<br />

Klavierunterricht; später studierte er unter Lew Oborin am Moskauer Konserva<strong>to</strong>rium. Seine Karriere<br />

begann bereits vielversprechend mit einem Triumvirat von Spitzenauszeichnungen: Er gewann 1955<br />

in Warschau den zweiten Preis beim <strong>International</strong>en Chopin-Wettbewerb, ein Jahr später den ersten<br />

Preis beim Königin-Elisabeth-Wettbewerb in Brüssel und teilte sich schließlich 1962 mit<br />

John Ogdon den ersten Platz beim Tschaikovskij-Wettbewerb in Moskau. An Letzterem hatte<br />

er unter einigem Druck teilgenommen und er berichtete später davon, dass das sowjetische<br />

Kulturministerium vom Gewinn des amerikanischen Pianisten Van Cliburn beim vorigen<br />

Wettbewerb so entsetzt gewesen war, dass es die russischen Studenten mehr oder weniger<br />

zur Teilnahme nötigte.<br />

Ein Jahr später verließ er zusammen mit seiner isländischen Frau die UdSSR. Das Paar zog<br />

erst nach London und später in die Schweiz. In London knüpfte Ashkenazy in den Sechzigern<br />

fruchtbare musikalische Beziehungen zu den anderen Angehörigen dieser „goldenen<br />

Generation“, besonders zu Daniel Barenboim, Pinchas Zukerman und Zubin Mehta. Er kehrte<br />

bis 1989 nicht mehr nach Russland zurück; als er es tat, wurde er von einem Kamerateam<br />

begleitet, das diese Erfahrung dokumentierte.<br />

Als Pianist neigte Ashkenazy nie zu übermäßiger Theatralik, häufig wählte er eher deutsche und<br />

Wiener Klassiker als übermäßig virtuose Vorzeigestücke. Schubert und Schumann gehörten<br />

dabei zu seinen bevorzugten Komponisten. Nichtsdes<strong>to</strong>weniger ist sein Reper<strong>to</strong>ire breit<br />

gefächert und abwechslungsreich; es umfasst überaus populäre Interpretationen der Werke von<br />

Chopin und Rachmaninoff sowie von Bach, Mozart, Beethoven und Schostakovitsch. In seinen<br />

mehr als fünfzig Jahren als Decca-Künstler hat er sich als einer der aufnahmefreudigsten<br />

Klavierinterpreten erwiesen.<br />

Er hat sich manchmal unzufrieden über seine kleine Handgröße geäußert und ist in den letzten<br />

Jahren weniger häufig öffentlich aufgetreten, zum Teil aufgrund seiner Arthritis. Doch seine<br />

musikalische Meisterschaft erstaunt weiterhin Publikum und Orchester. Im Laufe der Jahre<br />

konnte er seiner Liste von Chefdirigenten-Positionen die Royal Philharmonic, das Philharmonia<br />

Orchestra, das NHK-Sinfonieorchester, das Isländische Sinfonieorchester, das Jugendorchester<br />

der Europäischen Union und, seit 2009, das Sydney Symphony Orchestra in Australien hinzufügen.<br />

Ashkenazy ist immer mit einer außergewöhnlichen musikalischen Auffassungsgabe gesegnet<br />

gewesen, doch gleichzeitig zeigt er angesichts seiner internationalen Berühmtheit eine seltene<br />

Bescheidenheit. Vor einigen Jahren sagte er im Interview mit mir: „Musik ist ein unglaubliches<br />

Geschenk Gottes und der Natur. Ich bin nur ein aufführender Musiker und ich besitze nicht<br />

das kreative Genie von beispielsweise Bach oder Schostakovitsch, deshalb empfinde ich<br />

ihnen gegenüber große Demut. Mein Ziel ist es, ein Diener zu sein, der die Musik zum<br />

Leben erweckt.“<br />

Außerdem wies er auf die enge Verbindung zwischen Klavierspielen und Dirigieren hin: „Es<br />

ist eine nabelschnurähnliche Verknüpfung. Beispielsweise setzt man auf dem Klavier jedes<br />

klangliche Register ein und dies lässt einem beim Dirigieren bewusst werden, dass man alle<br />

Bereiche des Klangspektrums berücksichtigen muss, von ganz tief bis ganz hoch. Und was die<br />

8 9

Gegenrichtung angeht, so hatte ich seit meiner Kindheit den Orchesterklang im Kopf und habe<br />

immer versucht, diesen beim Klavierspielen nachzubilden.“<br />

Ashkenazy sitzt hoch und nah an den Tasten, er vermeidet unnötige Bewegungen und überflüssige<br />

physikalische „Projektion“; seine gesamte Energie konzentriert sich auf den musikalischen Inhalt. In<br />

diesem Fall hebt das kleine BBC-Studio die puristische Klarheit seines Ansatzes hervor, während die<br />

Kameraführung hinreichende Gelegenheit gibt, die (in seinem Fall überraschend kleinen) Hände<br />

eines Meisterpianisten bei der Arbeit zu studieren.<br />

Das Schubert-Rezital beginnt mit den ersten beiden der drei späten Klavierwerke D946, welche<br />

manchmal als Impromptus und manchmal als Klavierstücke bezeichnet werden. Beide sind sektional<br />

und basieren auf extremen Kontrasten. Nr. 1 kontrastiert eine fieberhafte Tarantella mit introspektiven<br />

Passagen, wobei die vielschichtigen Akkordstrukturen an die Liederzyklen Winterreise und<br />

Schwanengesang des Komponisten erinnern. Das zweite Stück beginnt mit einer volksliedhaften<br />

Melodie, der dann deutlich unruhigere Episoden gegenübergestellt werden. Als Nächstes folgt<br />

Schuberts Wanderer-Fantasie, eine große Sonate mit vier Sätzen ohne Pause. Ihr Kernstück bildet die<br />

Melodie des Liedes Der Wanderer (D493), die zu Beginn des langsamen Satzes auftaucht. „Ich bin<br />

ein Fremdling überall“ lautet der Text aus einem Gedicht von Georg Philipp Schmidt von Lübeck.<br />

Ashkenazy erzeugt einen samtenen Klang, der hervorragend zum liederartigen Charakter dieser<br />

Stücke passt, und gleichzeitig konzentriert er sich völlig auf die Atmosphäre des Beginns der<br />

Wanderer-Fantasie und dessen krönender Schlussfuge, wobei seine äußerlich ruhige<br />

Aufführungsweise den Kokon für leidenschaftlich hingebungsvolles Musizieren bildet.<br />

der Sonate eher durch die klangliche Bandbreite hervor als durch extreme Tempi. Sein kraftvoller,<br />

tiefer Anschlag drückt die stürmische Turbulenz der Eröffnung aus, während der langsame Satz sich<br />

durch außergewöhnliche Sensibilität und eine strahlende Schönheit auszeichnet, welche die Zuhörer<br />

völlig fesselt.<br />

Die frühe Romantik von Schubert und Schumann harmoniert hervorragend mit Ashkenazys sanfter<br />

und zurückhaltender Klavierkunst. Diese Filmaufnahmen geben einer weiteren Generation von<br />

Musikliebhabern die Möglichkeit, sein musikalisches Können zu genießen.<br />

Jessica Duchen<br />

Übersetzung: Leandra Rhoese<br />

Das Schumann-Programm besteht aus der beliebten Arabeske op. 18, gefolgt von der Sonate Nr. 1<br />

in fis-Moll op. 11. Die Arabeske stammt von 1839 und die fließende Unvorhersehbarkeit ihrer Form<br />

verweist auf die experimentelleren Strukturen, denen Schumann sich später widmete. Auch wenn<br />

Schumanns Metronomangabe ein rasches Tempo vorgibt, ist dies von vielen als zu schnell<br />

empfunden worden. Ashkenazy nimmt sich auf dieser Aufnahme die Zeit, die inneren Feinheiten<br />

Schumanns vielschichtiger Komposition herauszuarbeiten, und konzentriert sich gleichzeitig auf das<br />

poetische Anschwellen und Abebben des Werkes.<br />

Der Klaviersonate Nr. 1 liegt Schumanns leidenschaftliche Zuneigung zur jungen Pianistin Clara<br />

Wieck zugrunde – deren Vater sich heftigst weigerte, ihrer Heirat zuzustimmen. Er veröffentlichte es<br />

anonym unter dem Titel „Clara zugeeignet von Florestan und Eusebius“. Diese beiden Charaktere<br />

repräsentierten entgegengesetzte Seiten seiner Persönlichkeit: Florestan war extrovertiert und<br />

stürmisch, Eusebius sanftmütig, nachdenklich und poetisch. Große Teile der Sonate lassen sich<br />

diesen beiden Charakteren zuordnen, doch es gibt auch eine Verbindung zu Clara: Im ersten Satz<br />

nahm Schumann eine Figur aus einem Klavierstück, das sie komponiert hatte, und kombinierte es<br />

mit einem seiner eigenen Themen. Dieser Satz schien zu sagen: Wenn es ihnen nicht möglich war,<br />

im Leben zusammen zu sein, so konnten sie doch zumindest in der Kunst vereint sein. Letztendlich<br />

trotzte das Paar Claras Vater und sie heirateten im September 1840. Ashkenazy hebt die Kontraste in<br />

10<br />

11

Also available on DVD and digital <strong>download</strong>:<br />

ICAD 5013<br />

Brahms: Piano Concer<strong>to</strong> No.2<br />

Garrick Ohlsson<br />

BBC Symphony Orchestra<br />

James Loughran<br />

ICAD 5027<br />

Glinka: Ruslan and Lyudmila<br />

Three Dances from ‘A Life for the Tsar’<br />

Tchaikovsky: The Nutcracker – Act II<br />

BBC Symphony Orchestra<br />

Gennadi Rozhdestvensky<br />

Diapason d’or<br />

ICAD 5031<br />

R. Strauss: Till Eulenspiegel<br />

Ein Heldenleben<br />

London Symphony Orchestra<br />

Michael Tilson Thomas<br />

ICAD 5037<br />

Vaughan Williams: Symphony No.8<br />

Job: A Masque for Dancing<br />

London Philharmonic Orchestra<br />

Sir Adrian Boult · Diapason d’or<br />

ICAD 5028<br />

Haydn: Symphony No.98<br />

Bruckner: Symphony No.7<br />

Bos<strong>to</strong>n Symphony Orchestra<br />

Charles Munch<br />

ICAD 5029<br />

Brahms: Symphonies Nos.1 & 2<br />

Bos<strong>to</strong>n Symphony Orchestra<br />

Charles Munch<br />

ICAD 5038<br />

Rachmaninov: The Bells<br />

Prokofiev: Lieutenant Kijé<br />

Sheila Armstrong · Robert Tear<br />

John Shirley-Quirk<br />

London Symphony Orchestra and Chorus<br />

André Previn<br />

ICAD 5039<br />

Mendelssohn: Symphonies Nos.3 & 4<br />

Bos<strong>to</strong>n Symphony Orchestra<br />

Charles Munch<br />

12<br />

13

ICAD 5041<br />

Mahler: Symphony No.5<br />

London Philharmonic Orchestra<br />

Klaus Tennstedt · Diapason d’or<br />

ICAD 5042<br />

Schumann: Symphony No.4<br />

Mahler: Das Lied von der Erde<br />

Carolyn Watkinson · John Mitchinson<br />

BBC Philharmonic Orchestra<br />

Kurt Sanderling<br />

ICAD 5050<br />

Tchaikovsky: Ballet Masterpieces<br />

Extracts from Sleeping Beauty, Swan Lake<br />

and The Nutcracker<br />

Margot Fonteyn · Michael Somes<br />

ICAD 5051<br />

Mahler: Symphony No.1<br />

Richard Strauss: Till Eulenspiegel<br />

Bos<strong>to</strong>n Symphony Orchestra<br />

Erich Leinsdorf<br />

ICAD 5043<br />

Schubert: Symphony No.9 ‘Great’<br />

Schumann: Symphony No.4<br />

Wagner: Good Friday Music from Parsifal<br />

Bos<strong>to</strong>n Symphony Orchestra<br />

Erich Leinsdorf<br />

ICAD 5049<br />

Bruckner: Symphony No.5<br />

BBC Symphony Orchestra<br />

Günter Wand<br />

ICAD 5052<br />

Schumann: Genoveva Overture<br />

Symphony No.2<br />

Schubert: Symphony No.5<br />

Bos<strong>to</strong>n Symphony Orchestra<br />

Charles Munch · Diapason d’or<br />

ICAD 5056<br />

Haydn: String Quartet in C ‘Emperor’<br />

Mozart: String Quartet in C K465<br />

Amadeus Quartet<br />

14 15

ICAD 5057<br />

Handel: Water Music Suite<br />

Mozart: Symphony No.36 ‘Linz’<br />

Symphony No.38 ‘Prague’<br />

Bos<strong>to</strong>n Symphony Orchestra<br />

Charles Munch<br />

ICAD 5059<br />

Beethoven: Egmont Overture<br />

Tchaikovsky: Symphony No.5<br />

Bos<strong>to</strong>n Symphony Orchestra<br />

Erich Leinsdorf · Diapason d’or<br />

ICAD 5066<br />

Bruckner: Symphony No.7<br />

Bos<strong>to</strong>n Symphony Orchestra<br />

Klaus Tennstedt<br />

ICAD 5067<br />

Haydn: Symphony No.55<br />

Beethoven: Symphonies Nos.7 & 8<br />

Bos<strong>to</strong>n Symphony Orchestra<br />

William Steinberg · Diapason d’or<br />

ICAD 5064<br />

Mendelssohn: Symphony No.4 ‘Italian’<br />

Britten: Les Illuminations<br />

Handel · Beethoven<br />

Academy of St Martin in the Fields<br />

Sir Neville Marriner<br />

ICAD 5065<br />

Berlioz: Le Corsaire – Overture<br />

Tchaikovsky: Manfred Symphony<br />

Elgar · Prokofiev<br />

St Petersburg Philharmonic Orchestra<br />

Yuri Temirkanov<br />

ICAD 5071<br />

Bruckner: Symphony No.8<br />

Bos<strong>to</strong>n Symphony Orchestra<br />

William Steinberg<br />

ICAD 5072<br />

Mahler: Symphony No.4<br />

Mozart: Symphony No.35 ‘Haffner’<br />

Bos<strong>to</strong>n Symphony Orchestra<br />

Klaus Tennstedt<br />

16<br />

17

ICAD 5073<br />

Chopin: Piano Works<br />

Beethoven: Piano Sonatas Nos.23 & 32<br />

Van Cliburn<br />

Claudio Arrau<br />

ICAD 5074<br />

Treasures of the Russian Ballet<br />

Galina Ulanova · Maya Plisetskaya<br />

Vladimir Vasiliev · Ekaterina Maximova<br />

Yuri Soloviev · Maris Liepa<br />

Raisa Struchkova<br />

ICAD 5025<br />

Tchaikovsky: Variations on a Rococo Theme<br />

Pezzo capriccioso · Romeo and Juliet Overture<br />

Britten: Gloriana (extracts)<br />

Mstislav Rostropovich · Peter Pears<br />

Aldeburgh Festival Singers<br />

English Chamber Orchestra<br />

Benjamin Britten<br />

ICAD 5089<br />

Mendelssohn: Overture – A Midsummer<br />

Night’s Dream<br />

Brahms: Symphony No.1<br />

Chicago Symphony Orchestra<br />

Sir Georg Solti<br />

ICAD 5082<br />

Stravinsky: The Rite of Spring<br />

Sibelius: Symphony No.5<br />

London Symphony Orchestra<br />

Leonard Bernstein · Diapason d’or<br />

18<br />

ICAD 5083<br />

Mozart: Symphony No.40<br />

Britten: Nocturne<br />

Mendelssohn: Symphony No.3 ‘Scottish’<br />

(extracts)<br />

Peter Pears · English Chamber Orchestra<br />

Benjamin Britten<br />

ICAD 5099<br />

Choreography by Bournonville<br />

La Sylphide<br />

Flower Festival in Genzano – Pas de deux<br />

Flemming Flindt · Lucette Aldous · Shirley Dixon<br />

Rudolf Nureyev · Merle Park<br />

19<br />

ICAD 5100<br />

Mozart: Symphony No.39<br />

Tchaikovsky: Symphony No.4<br />

Debussy: Fêtes (Trois Nocturnes)<br />

Chicago Symphony Orchestra<br />

Sir Georg Solti