Expanding the Public Sphere through Computer ... - ResearchGate

Expanding the Public Sphere through Computer ... - ResearchGate Expanding the Public Sphere through Computer ... - ResearchGate

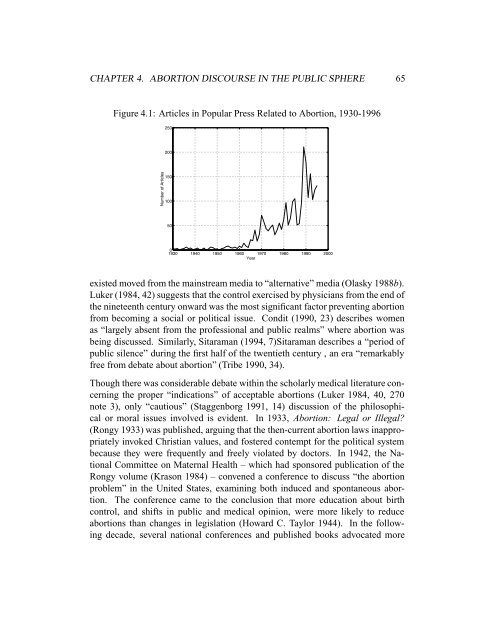

CHAPTER 4. ABORTION DISCOURSE IN THE PUBLIC SPHERE 64 abortion on moral grounds as early as 1797. Clear moral distinctions were made between the mother’s life and the life of the fetus: The public did not consider the embryo “not alive” in the biological sense .... Rather, public (and much medical opinion) seems to have been that embryos were, morally speaking simply not as alive as the mother, at least until quickening – and sometimes later than that, if the pregnancy threatened the life of the woman (Luker 1984, 26). On the other hand, Sitaraman (1994, 4) contends that fetuses prior to quickening were “not considered a human being, and abortions were viewed as a point on the continuum including contraception,” and suggests that ignorance of pregnancy and fetal development contributed to the lack of public discussion of abortion. Public discourse during the criminalization period is dominated by the medical profession, and it is clear that the voices of women and ordinary citizens were largely excluded from the limited debate that did occur. One indication of the lack of public debate during this period is the complete absence of articles concerning abortion indexed in the Reader’s Guide to Periodical Literature prior to 1890. In addition, neither the religious nor legal communities appear to have made significant contributions to the public discussion of the abortion issue. This is surprising, given the Catholic church’s 1869 papal statement abandoning the distinction between early and late abortions (Tribe 1990, 31), and given the large number of new state laws enacted. By contrast, the newly emergent American Medical Association regularly issued regular reports and papers urging that decisions about abortion be made by licensed physicians on the basis of their superior education, technical and moral standing. In an interesting rhetorical feat, simultaneously claimed “both an absolute right to life for the embryo (by claiming that abortion is always murder) and a conditional one (by claiming that doctors have a right to declare some abortions ’necessary’)” (Luker 1984, 32). During the fifty years following the criminalization period, discussion about abortion remained by and large confined to medical, legal and religious professionals. There are no articles indexed under “abortion” Reader’s Guide to Periodical Literature until 1929, and the number of articles from 1929 to 1960 never reached more than twelve in any year (See Figure 4.1 on the following page). Once the pattern of criminalization was established, whatever public discourse about abortion

CHAPTER 4. ABORTION DISCOURSE IN THE PUBLIC SPHERE 65 Figure 4.1: Articles in Popular Press Related to Abortion, 1930-1996 250 200 Number of Articles 150 100 50 0 1930 1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 Year existed moved from the mainstream media to “alternative” media (Olasky 1988b). Luker (1984, 42) suggests that the control exercised by physicians from the end of the nineteenth century onward was the most significant factor preventing abortion from becoming a social or political issue. Condit (1990, 23) describes women as “largely absent from the professional and public realms” where abortion was being discussed. Similarly, Sitaraman (1994, 7)Sitaraman describes a “period of public silence” during the first half of the twentieth century , an era “remarkably free from debate about abortion” (Tribe 1990, 34). Though there was considerable debate within the scholarly medical literature concerning the proper “indications” of acceptable abortions (Luker 1984, 40, 270 note 3), only “cautious” (Staggenborg 1991, 14) discussion of the philosophical or moral issues involved is evident. In 1933, Abortion: Legal or Illegal? (Rongy 1933) was published, arguing that the then-current abortion laws inappropriately invoked Christian values, and fostered contempt for the political system because they were frequently and freely violated by doctors. In 1942, the National Committee on Maternal Health – which had sponsored publication of the Rongy volume (Krason 1984) – convened a conference to discuss “the abortion problem” in the United States, examining both induced and spontaneous abortion. The conference came to the conclusion that more education about birth control, and shifts in public and medical opinion, were more likely to reduce abortions than changes in legislation (Howard C. Taylor 1944). In the following decade, several national conferences and published books advocated more

- Page 13 and 14: CHAPTER 1. COMPUTERS, CONVERSATION

- Page 15 and 16: CHAPTER 2. THE PUBLIC SPHERE 15 2.1

- Page 17 and 18: CHAPTER 2. THE PUBLIC SPHERE 17 Sch

- Page 19 and 20: CHAPTER 2. THE PUBLIC SPHERE 19 sta

- Page 21 and 22: CHAPTER 2. THE PUBLIC SPHERE 21 or

- Page 23 and 24: CHAPTER 2. THE PUBLIC SPHERE 23 own

- Page 25 and 26: CHAPTER 2. THE PUBLIC SPHERE 25 new

- Page 27 and 28: CHAPTER 2. THE PUBLIC SPHERE 27 com

- Page 29 and 30: CHAPTER 2. THE PUBLIC SPHERE 29 Hab

- Page 31 and 32: CHAPTER 2. THE PUBLIC SPHERE 31 pub

- Page 33 and 34: CHAPTER 2. THE PUBLIC SPHERE 33 the

- Page 35 and 36: CHAPTER 2. THE PUBLIC SPHERE 35 ori

- Page 37 and 38: CHAPTER 2. THE PUBLIC SPHERE 37 gen

- Page 39 and 40: CHAPTER 2. THE PUBLIC SPHERE 39 pub

- Page 41 and 42: CHAPTER 2. THE PUBLIC SPHERE 41 By

- Page 43 and 44: Chapter 3 Technology & the Public S

- Page 45 and 46: CHAPTER 3. TECHNOLOGY & THE PUBLIC

- Page 47 and 48: CHAPTER 3. TECHNOLOGY & THE PUBLIC

- Page 49 and 50: CHAPTER 3. TECHNOLOGY & THE PUBLIC

- Page 51 and 52: CHAPTER 3. TECHNOLOGY & THE PUBLIC

- Page 53 and 54: CHAPTER 3. TECHNOLOGY & THE PUBLIC

- Page 55 and 56: CHAPTER 3. TECHNOLOGY & THE PUBLIC

- Page 57 and 58: Chapter 4 Abortion Discourse in the

- Page 59 and 60: CHAPTER 4. ABORTION DISCOURSE IN TH

- Page 61 and 62: CHAPTER 4. ABORTION DISCOURSE IN TH

- Page 63: CHAPTER 4. ABORTION DISCOURSE IN TH

- Page 67 and 68: CHAPTER 4. ABORTION DISCOURSE IN TH

- Page 69 and 70: Chapter 5 Measuring the Public Sphe

- Page 71 and 72: CHAPTER 5. MEASURING THE PUBLIC SPH

- Page 73 and 74: CHAPTER 5. MEASURING THE PUBLIC SPH

- Page 75 and 76: CHAPTER 5. MEASURING THE PUBLIC SPH

- Page 77 and 78: CHAPTER 6. ANALYZING THE TALK.ABORT

- Page 79 and 80: CHAPTER 6. ANALYZING THE TALK.ABORT

- Page 81 and 82: CHAPTER 6. ANALYZING THE TALK.ABORT

- Page 83 and 84: CHAPTER 6. ANALYZING THE TALK.ABORT

- Page 85 and 86: CHAPTER 6. ANALYZING THE TALK.ABORT

- Page 87 and 88: CHAPTER 6. ANALYZING THE TALK.ABORT

- Page 89 and 90: CHAPTER 6. ANALYZING THE TALK.ABORT

- Page 91 and 92: CHAPTER 6. ANALYZING THE TALK.ABORT

- Page 93 and 94: CHAPTER 6. ANALYZING THE TALK.ABORT

- Page 95 and 96: CHAPTER 6. ANALYZING THE TALK.ABORT

- Page 97 and 98: CHAPTER 6. ANALYZING THE TALK.ABORT

- Page 99 and 100: CHAPTER 6. ANALYZING THE TALK.ABORT

- Page 101 and 102: Chapter 7 The Expanding Public Sphe

- Page 103 and 104: CHAPTER 7. THE EXPANDING PUBLIC SPH

- Page 105 and 106: CHAPTER 7. THE EXPANDING PUBLIC SPH

- Page 107 and 108: Appendix A The talk.abortion newsgr

- Page 109 and 110: APPENDIX A. TALK.ABORTION: AUGUST 9

- Page 111 and 112: APPENDIX A. TALK.ABORTION: AUGUST 9

- Page 113 and 114: APPENDIX A. TALK.ABORTION: AUGUST 9

CHAPTER 4. ABORTION DISCOURSE IN THE PUBLIC SPHERE 65<br />

Figure 4.1: Articles in Popular Press Related to Abortion, 1930-1996<br />

250<br />

200<br />

Number of Articles<br />

150<br />

100<br />

50<br />

0<br />

1930 1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000<br />

Year<br />

existed moved from <strong>the</strong> mainstream media to “alternative” media (Olasky 1988b).<br />

Luker (1984, 42) suggests that <strong>the</strong> control exercised by physicians from <strong>the</strong> end of<br />

<strong>the</strong> nineteenth century onward was <strong>the</strong> most significant factor preventing abortion<br />

from becoming a social or political issue. Condit (1990, 23) describes women<br />

as “largely absent from <strong>the</strong> professional and public realms” where abortion was<br />

being discussed. Similarly, Sitaraman (1994, 7)Sitaraman describes a “period of<br />

public silence” during <strong>the</strong> first half of <strong>the</strong> twentieth century , an era “remarkably<br />

free from debate about abortion” (Tribe 1990, 34).<br />

Though <strong>the</strong>re was considerable debate within <strong>the</strong> scholarly medical literature concerning<br />

<strong>the</strong> proper “indications” of acceptable abortions (Luker 1984, 40, 270<br />

note 3), only “cautious” (Staggenborg 1991, 14) discussion of <strong>the</strong> philosophical<br />

or moral issues involved is evident. In 1933, Abortion: Legal or Illegal?<br />

(Rongy 1933) was published, arguing that <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>n-current abortion laws inappropriately<br />

invoked Christian values, and fostered contempt for <strong>the</strong> political system<br />

because <strong>the</strong>y were frequently and freely violated by doctors. In 1942, <strong>the</strong> National<br />

Committee on Maternal Health – which had sponsored publication of <strong>the</strong><br />

Rongy volume (Krason 1984) – convened a conference to discuss “<strong>the</strong> abortion<br />

problem” in <strong>the</strong> United States, examining both induced and spontaneous abortion.<br />

The conference came to <strong>the</strong> conclusion that more education about birth<br />

control, and shifts in public and medical opinion, were more likely to reduce<br />

abortions than changes in legislation (Howard C. Taylor 1944). In <strong>the</strong> following<br />

decade, several national conferences and published books advocated more