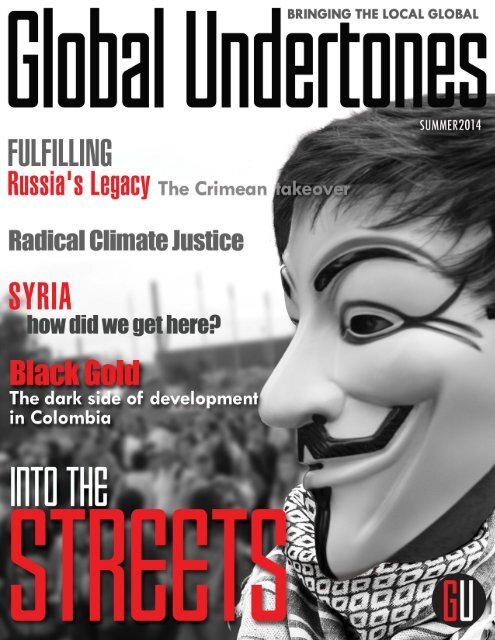

Global Undertones: INTO THE STREETS

Issue 1/ Summer 2014

Our first issue’s theme is entitled INTO THE STREETS.

Inspired by the recent expansion of public political participation and mobilization that has dominated foreign politics and media coverage over the last few years, this issue covers a range of topics from labor politics, climate change, to all out revolution.

All of these movements have similar bearings- rooted in shared economic, social, and political realities that have stirred civilians to act towards change.

The aim of this issue is to expose some of the less commonly explored narratives that shaped these ongoing events, as well as their outcomes and consequences.

Issue 1/ Summer 2014

Our first issue’s theme is entitled INTO THE STREETS.

Inspired by the recent expansion of public political participation and mobilization that has dominated foreign politics and media coverage over the last few years, this issue covers a range of topics from labor politics, climate change, to all out revolution.

All of these movements have similar bearings- rooted in shared economic, social, and political realities that have stirred civilians to act towards change.

The aim of this issue is to expose some of the less commonly explored narratives that shaped these ongoing events, as well as their outcomes and consequences.

- Page 2 and 3: CONTENT summer 2014 CONTRIBUTORS 4

- Page 4 and 5: CONTRIBUTORS FELICIA GRAHAM Felicia

- Page 6 and 7: EXTRACTING THE in 21 st Century Col

- Page 8 and 9: Part I: The ‘success’ story “

- Page 10 and 11: nature and society” - in short, h

- Page 12 and 13: een invested in making these houses

- Page 14 and 15: Photo Courtesy of Debra Sweet Prote

- Page 16 and 17: While compelling arguments have bee

- Page 18 and 19: problematic as a whole, and she rec

- Page 20 and 21: two individuals: while each holds t

- Page 22 and 23: By Sergey Salushev Crimea’s Succe

- Page 24 and 25: In the weeks following the overthro

- Page 26 and 27: Ukraine’s political crisis was a

- Page 28 and 29: nationalist constituent groups, as

- Page 30 and 31: limate Change and the Food Secur im

- Page 32 and 33: The United Nations Intergovernmenta

- Page 34 and 35: “ Get it DONE! [i] “ Rarer by f

- Page 36 and 37: The science is in: climate change i

- Page 38 and 39: demands revolutionary change to the

- Page 40 and 41: formed up, and attracted to it some

- Page 42 and 43: November 4-7 in Caracas. Another ma

- Page 44 and 45: Working with THREADS Realizing stud

- Page 46 and 47: The global “sweatshop” epidemic

- Page 48 and 49: called United Students Against Swea

- Page 50 and 51: Curving Towards REVOLUTION: Cronyis

CONTENT<br />

summer 2014<br />

CONTRIBUTORS 4<br />

EXTRACTING <strong>THE</strong> TRUTH 8<br />

Coexisting with black gold in 20th century Colombia<br />

WORLD ALIENATION & OUR LIVES WITH DRONES 16<br />

Arendt and Habermas’ solutions<br />

<strong>THE</strong> CRIMEAN SUCCESION 24<br />

History before politics<br />

CLIMATE CHANGE 32<br />

The food security dimension<br />

“GET IT DONE!” 36<br />

The <strong>Global</strong> Climate Justice Movement & the fateful race for a radical<br />

climate treaty<br />

WORKING WITH THREADS 46<br />

Realizing student activists’ clout in the global labor movement<br />

CURVING TOWARDS REVOLUTION 52<br />

Cronyism & deprivation in Syria<br />

SOURCES 60<br />

2 GLOBAL UNDERTONES / globalundertones.com

Executive Editor/Founder<br />

Jamison Crowell<br />

Managing Editor<br />

Emilie Olson<br />

Copy Editor<br />

M.A. Miller<br />

Graphic Designer<br />

Eve Klimova<br />

Issue I: <strong>INTO</strong> <strong>THE</strong> <strong>STREETS</strong><br />

Our first issue is inspired by the recent<br />

expansion of public political<br />

participations and mobilization that<br />

has dominated foreign politics and<br />

media coverage over the last few<br />

years. This issue covers a range of<br />

topics from labor politics, climate<br />

change, to all out revolution.<br />

All of these movements have similar<br />

bearings- rooted in shared economic,<br />

social, and political realities that<br />

have compelled civilians to act in<br />

the pursuit of change.<br />

The aim of “Into the Streets” is to<br />

expose some of the less commonly<br />

explored narratives that shaped<br />

these ongoing events, as well as<br />

their outcomes and consequences.<br />

About Us<br />

<strong>Global</strong> <strong>Undertones</strong> Magazine (GU)<br />

is a peer-reviewed global affairs<br />

publication. Founded in 2013 by<br />

a group of graduate students, our<br />

publication aims to narrow the gap<br />

between popular and academic<br />

narratives of world issues.<br />

GU’s objective of “bringing the local<br />

global” highlights our dedication to<br />

accessibility. The stories we publish<br />

not only help explain developments<br />

around the world, but take seemingly<br />

localized events and emphasize<br />

their importance in a way that<br />

resonates with readers regardless<br />

of their country of origin.<br />

Contact<br />

General:<br />

info@globalundertones.com<br />

Submissions Info:<br />

submissions@globalundertones.com<br />

Summer 2014<br />

3

CONTRIBUTORS<br />

FELICIA GRAHAM<br />

Felicia Graham earned her M.A. in <strong>Global</strong> & International Studies from<br />

the University of California Santa Barbara where her research explored<br />

the socioeconomic and psychological impacts of resource extraction in Latin<br />

America. She is also the author of various academic articles and has<br />

presented at a series of <strong>Global</strong> Studies conferences. Ms. Graham has extensive<br />

experience working with low-income youth and refugee children<br />

in the Bay Area and San Diego, both in education and mental health. Ms.<br />

Graham is currently the Department Chair and Lead Teacher of the <strong>Global</strong><br />

Studies and Social Science Program at American University Preparatory<br />

School in Los Angeles.<br />

JACOB MARTHALLER<br />

Jacob Marthaller is a graduate student in Religious Studies at the University<br />

of Virginia. His research interests focus primarily in the realm of political<br />

theology and ethics, with a particular bent towards legal theory. Currently<br />

pursuing his master’s degree, he hopes to continue in academia by obtaining<br />

a Ph.D. studying somewhere at the confluence of politics, theology, and<br />

law. Originally from Los Angeles, he is growing accustomed (albeit slowly)<br />

to life in rural Virginia. When not trapped in a university library, he can be<br />

found hiking the Appalachian Trail.<br />

SERGEY SALUSCHEV<br />

Sergey Saluschev was born in Potsdam, Germany. However, following the<br />

tumultuous collapse of the Soviet Union, his family returned to their original<br />

home in Russia’s Caucasus region where he lived until 2005. Sergey completed<br />

his Master in Arts degree in <strong>Global</strong> & International Studies in 2014<br />

and is currently pursuing a Ph.D. degree in History with an emphasis on<br />

history of Russia and Iran in the XIX century at the University of California,<br />

Santa Barbara.<br />

4 GLOBAL UNDERTONES / globalundertones.com

HILAL ELVER<br />

Hilal Elver is a Research Professor, and co-director of the Project on <strong>Global</strong><br />

Climate Change, Human Security, and Democracy housed at the Orfalea<br />

Center for <strong>Global</strong> & International Studies at the University of California,<br />

Santa Barbara. She has a law degree, a Ph.D. from the University of Ankara<br />

Law School, and SJD from the UCLA Law School. She has written numerous<br />

chapters in books and articles in academic journals on <strong>Global</strong> Justice, New<br />

Constitutionalism, Secularism, women’s rights, water rights, environmental security,<br />

climate change diplomacy and food security. As of June, she is acting<br />

Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food by the Human Rights Council.<br />

JOHN FORAN<br />

John Foran is professor of Sociology at the University of California, Santa<br />

Barbara, where he is also involved with the programs in Latin American<br />

and Iberian Studies, <strong>Global</strong> and International Studies, Environmental Studies,<br />

and the Bren School. Professor Foran teaches courses on radical social<br />

change, globalization and resistance, global justice movements, climate activism,<br />

and research methods. He has written on many aspects of revolutions<br />

and movements for radical or deep social change. He is currently working on<br />

a book and is also engaged in a long-term research project on the global<br />

climate justice movement, with Richard Widick. Their work can be followed<br />

at www.iicat.org.<br />

CHRIS WEGEMER<br />

Chris Wegemer specializes in supply chain justice with a research focus on<br />

the Designated Suppliers Program. While working on his Master’s at the<br />

University of California, Santa Barbara, he worked for LaborVoices and<br />

the Worker Rights Consortium; organized campaigns for United Students<br />

Against Sweatshops; and spent time in the Dominican Republic partnering<br />

with student activists from all over the world. Chris previously studied physics<br />

at Providence College and electrical engineering at Columbia University.<br />

Among other things, he has: taught at Idyllwild Arts Academy, helped provide<br />

sustainable energy to rural communities in developing countries, and<br />

assisted with factory investigations.<br />

DANIEL ZORUB<br />

Daniel Zorub earned an M.A. in <strong>Global</strong> & International Studies from the<br />

University of California Santa Barbara. With strong research interests in<br />

the Middle East, Daniel wrote his thesis on political risk management for<br />

international education using the UC Education Abroad Program in Egypt as<br />

a case study. Previously, Daniel worked as a Communications Intern for the<br />

Carnegie Endowment for International Peace at their Carnegie Middle East<br />

Center in Beirut, and as a Sponsorship & Membership Intern at the Clinton<br />

<strong>Global</strong> Initiative in Washington, D.C.<br />

Summer 2014<br />

5

EXTRACTING<br />

<strong>THE</strong> in 21 st Century Colombia<br />

Coexisting with Black Gold<br />

TRUTH<br />

by Felicia Graham<br />

Throughout the world communities are beginning to mobilize in protest of<br />

the expansion of extractive industries (oil, gas, etc.) and the social ills they<br />

produce. In Papua New Guinea, the people of the Hela Province explain their<br />

preparations for war against Exxon Mobil’s Liquefied Natural Gas pipeline [i].<br />

In the U.S., Native American and Midwestern communities are protesting the construction<br />

of the Keystone XL Pipeline from Canada to the Gulf coast [ii]– not to mention oil<br />

rich countries like Nigeria and Sudan which have been mired in ongoing oil-related<br />

conflicts for years [iii].<br />

6 GLOBAL UNDERTONES / globalundertones.com

Because Colombia’s oil transportation<br />

infrastructure (pipelines) is insufficient to carry<br />

the oil from the southern fields to the refineries<br />

and terminals in the north, oil tank trucks are<br />

recruited. As a result, hundreds of oil tank trucks<br />

pass through Puerto Gaitan on a daily basis.<br />

Photo ourtesy of Felicia Graham<br />

But nowhere has there been more social movement and organization in opposition<br />

to resource extraction than in Latin America, as evidenced by the Gas [iv] and Water<br />

Wars in Bolivia [v], Peru, and Ecuador [vi].<br />

Yet, in Colombia, little to no attention has been paid to the plight of indigenous and<br />

local peoples’ struggles to protect their communities and ancestral territories from the<br />

pitfalls of extractive industries, and the perceived corporate globalization. In fact, the<br />

international community has done the opposite — labeling Colombia a development<br />

success story — in large part thanks to the oil, gas, and coal.<br />

Summer 2014<br />

7

Part I: The ‘success’<br />

story<br />

“At a time of acute doubt over<br />

the future… Colombia provides<br />

a model for hope as well as a<br />

reminder of what is required to<br />

make such progress possible”-<br />

Michael O’Hanlon and David<br />

Petraeus [vii]<br />

Throughout the 20th century,<br />

Colombia’s economic development<br />

and relations with neighboring<br />

countries were strained and<br />

hampered by fifty years of internal<br />

conflict with the leftist FARC<br />

(Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias<br />

de Colombia), leaving Colombia<br />

closed for business both politically<br />

and economically. But the 21st<br />

Century is shaping up quite<br />

differently and the country is<br />

increasingly being described as<br />

a success story.<br />

Indeed, in 2012 Colombia<br />

received an unprecedented<br />

invitation to join the Organization<br />

for Economic Development and<br />

Cooperation (OECD) - a true<br />

landmark in the country’s history<br />

and a marker of its triumph over<br />

systemic violence and a rampant<br />

international drug trade. After<br />

decades of violent conflict<br />

that slowed the economy to a<br />

frighteningly sluggish pace,<br />

Colombia finally appears to be<br />

surfacing and on the fast track<br />

to long hoped-for peace and<br />

development.<br />

But where has this growth<br />

come from? Relative peace in<br />

Colombia has been one part of<br />

Photo Courtesy of OECD/Herve Cortinat<br />

Columbia’s President (right), Juan Manuel Santos, shaking hands with OECD Secretary-General (left), Angel Gurría, in 2011-<br />

one year before Columbia would be invited to join.<br />

the country’s apparent success,<br />

as Colombians and foreigners<br />

alike re-engage in business<br />

activities without the constraint<br />

of bombings, kidnappings, or<br />

homicides. But the other part<br />

is the economic success of the<br />

oil and gas industry, which<br />

has unquestionably driven the<br />

country’s growth in the past<br />

decade.<br />

In 2010 President Juan Manuel<br />

Santos identified oil and gas as<br />

one of Colombia’s five ‘engines<br />

of growth’[viii]. Since then,<br />

there has been consensus among<br />

politicians that the expansion of<br />

the industry benefits the country<br />

as a whole [ix].<br />

The successful expansion<br />

of the oil and gas industry in<br />

Colombia is aptly reflected in<br />

the numbers: in 2013 Colombia<br />

overtook Argentina to become the<br />

third largest economy in Latin<br />

America – worth $369 billion –<br />

behind Brazil and Mexico, while<br />

Colombia’s Gross Domestic<br />

Product (GDP) continues to<br />

steadily grow at an average of<br />

4% per annum [x] - a glaring<br />

achievement in light of U.S. and<br />

Europe’s struggling economies<br />

since the global economic<br />

depression, and implying a rising<br />

standard of living for Colombians<br />

on the whole.<br />

That same year Colombia<br />

registered a total of $16.8 billion<br />

in Foreign Direct Investment<br />

(FDI), more than nine times<br />

greater than a decade prior ($1.7<br />

billion in 2003) [xi]– indicating an<br />

attractive open economy, a “skilled<br />

workforce, and good growth<br />

prospects” – all prerequisites for<br />

a modern functional economy in<br />

a globalizing world [xii].<br />

And while FDI into the country<br />

continues to reach new heights,<br />

hydrocarbons (oil, gas, and coal)<br />

have become a cornerstone of<br />

the Colombian economy, with<br />

FDI into oil and gas multiplying<br />

exponentially since 2010 and<br />

financing almost all of the<br />

8 GLOBAL UNDERTONES / globalundertones.com

country’s recent progress. In<br />

2012, for example, FDI into<br />

Colombia’s oil and gas sector<br />

totaled only $5.3 billion; one<br />

year later, this number doubled<br />

to $13.3 billion – accounting<br />

for a record 81.6%of total FDI<br />

in 2013 [xiii].<br />

Without a doubt, Colombia is<br />

moving towards an extractive led<br />

development and growth model,<br />

with no intention of stopping any<br />

time soon. But what does this<br />

mean for the people living in<br />

areas where this oil exploration<br />

and production is taking place?<br />

While the influx of wealth<br />

from the oil industry’s expansion<br />

benefits the Colombian economy<br />

overall, there is another story to be<br />

told. The turbulent transformations<br />

to communities and individuals<br />

living adjacent to oil extraction<br />

sites are much more complex,<br />

and thus experience Colombia’s<br />

growth in a completely different<br />

way than the mainstream fairytale<br />

would have us believe. It is these<br />

experiences that persist just below<br />

the surface, which in the end<br />

can be much more influential in<br />

determining Colombia’s future.<br />

Part II: The reality<br />

Many communities that coexist<br />

with the black gold and other<br />

extractive industries have struggled<br />

to maintain their culture and<br />

livelihoods in Colombia, which<br />

is home to some 2.2 billion<br />

barrels of proven oil reserves<br />

[xiv]. The vast majority of oil<br />

extraction, however, takes place<br />

in the Colombian South, in an<br />

Summer 2014<br />

area known as los Llanos, or<br />

the planes. Geographically, los<br />

Llanos also referred to as the<br />

Orinoquia region, makes up<br />

part of the Oronico oil belt that<br />

runs from Venezuela, through<br />

Colombia to Ecuador.<br />

But los Llanos is also cattle<br />

ranching country, similar to<br />

a Colombian Texas. And like<br />

Texas, los Llanos is home to<br />

the country’s most successful<br />

and largest producing oil field<br />

– The Pacific Rubiales block,<br />

which accounts for more than 50<br />

percent of the country’s total oil<br />

production. The Pacific Rubiales<br />

field is housed in the state of<br />

Meta, which itself making up<br />

one of the larger states in the<br />

country [ xv].<br />

Despite its extensive territory,<br />

however, Meta’s population is<br />

relatively small. Yet because<br />

Meta produces the most oil in the<br />

country the state receives the most<br />

royalties. Between 2006-2008,<br />

for example, Meta’s royalties<br />

from oil and gas increased by<br />

270% [ xvi].<br />

But the success of the oil and<br />

gas industry has done far more<br />

than facilitate an influx of plata<br />

(wealth) into the region – it has<br />

also stimulated a wave of migrants<br />

seeking employment, and thus<br />

generated a number of cultural<br />

clashes and social tensions.<br />

While some have benefited from<br />

the arrival of the oil industry,<br />

many more have endured the<br />

negative consequences that the<br />

industry has brought, which,<br />

with little to no management,<br />

has time and again proven its<br />

ability to wreak havoc on local<br />

communities such as Puerto<br />

Gaitan – the oil capital of Meta.<br />

Meta’s ‘resource curse’<br />

The story of Puerto Gaitan,<br />

Meta is not particularly new or<br />

novel, as similar experiences<br />

have been documented by the<br />

Wayyu indigenous community the<br />

Northern state of La Guajira [xvii<br />

], the Bari indigenous community<br />

on the border of Venezuela [ xviii],<br />

and by indigenous communities<br />

in neighboring countries such<br />

as the Cofan in Ecuador and the<br />

Segunda and Cajas in Peru [ xix].<br />

In fact, issues related to resource<br />

extraction are so common that it<br />

has led academics to develop a<br />

number of theories to understand<br />

the problems of resource-rich<br />

countries including Resource<br />

Curse Theory and Resource Wars.<br />

One of the most comprehensive<br />

theories for understanding the<br />

problems afflicting resourcerich<br />

countries and communities,<br />

however, comes from Political<br />

Ecology.<br />

Anthony Bebbington constitutes<br />

one of the most notable thinkers<br />

to fully engage and compile<br />

evidence related to local struggles<br />

related to resource extraction,<br />

particularly in Latin America.<br />

His 2013 work Subterrenean<br />

Struggles illustrates the ‘new<br />

geographies of extraction’ which<br />

explains the intricate ways in<br />

which “extraction bundles<br />

9

nature and society” – in short,<br />

he makes clear the ways in which<br />

communities undergo changes<br />

related to land use, labor, and<br />

social relations, and how people<br />

exist, resist, and adapt to life in<br />

extractive communities [xx].<br />

While Bebbington’s work is<br />

extensive, Colombia is excluded<br />

from the discussion. Drawing on<br />

first-hand field research conducted<br />

in Puerto Gaitan, Meta during<br />

the fall of 2013, through the<br />

University of California, Santa<br />

Barbara, our team discovered how<br />

these changes also apply to the<br />

Colombian context, particularly<br />

in three areas: environmental<br />

degradation, job insecurity, and<br />

superficial development projects.<br />

The stories following illustrate<br />

the negative experiences of<br />

indigenous communities and<br />

mestizos alike since the arrival<br />

of the oil industry to los Llanos<br />

in 2000.<br />

Environmental<br />

degradation<br />

The Sikuani indigenous<br />

community is one of nine small<br />

communities home to Meta,<br />

though they are the largest in<br />

the area. Before the arrival of<br />

the oil industry, Sikuani life was<br />

characterized by a subsistence,<br />

lifestyle. But with the arrival of<br />

the oil industry the community<br />

agreed to sell their ancestral<br />

territory – though with little<br />

understanding of the implications.<br />

With the oil exploration process<br />

in full swing all but a few of the<br />

wildlife have now fled the area<br />

due to noise contamination. Dust<br />

kicked up in the air from the oil<br />

tank trucks has, additionally,<br />

They lost their ways of living,<br />

lost the characteristics that<br />

had allowed them to exist as<br />

something different.<br />

”<br />

clouded the river water where<br />

many used to fish.<br />

Though the oil company says<br />

the river is not chemically<br />

contaminated, the Sikuani no<br />

longer fish from the river for<br />

fear of contamination: “they<br />

dare not eat the fish anymore,<br />

they are afraid to eat them. You<br />

cannot see the physical damages<br />

on the bodies, but they are afraid<br />

of the contamination,” said one<br />

of the Siquani’s community<br />

leaders [xxi].<br />

To the Sikuani this culminates<br />

in the cultural degradation of the<br />

community, who are no longer<br />

able to adhere to their traditional<br />

practices. One member explains it<br />

as such: “The population Sikuani<br />

used to be based on fishing and<br />

hunting, but oil changed this way<br />

of life. Now they are getting used<br />

to white people behavior - they are<br />

entering a consumer and capitalist<br />

lifestyle. [They] lost their ways<br />

of living, lost the characteristics<br />

that had allowed them to exist<br />

as something different” [xxii].<br />

Another Sikuani member<br />

explained similarly, describing<br />

how “since [the exploitation]<br />

started they have been seeing<br />

environmental changes. The<br />

small water ways coming from<br />

the mountain are contaminated by<br />

crude and many fish died. From<br />

this the fishing activities were<br />

affected. [In some areas] there is<br />

also contamination from a crude<br />

explosion that contaminated the<br />

savannah, and from this also<br />

many cows died from lands and<br />

plants polluted by oil. We have<br />

tried to talk to the authorities,<br />

but when someone has the money<br />

they don’t care” [xxiii].<br />

Job insecurity<br />

These environmental changes<br />

have not only disrupted the<br />

lifestyles and livelihoods<br />

of communities, but deeply<br />

affected the sense of security and<br />

stability of indigenous men and<br />

women who are now forced to<br />

conform to a foreign monetarybased<br />

system of consumption<br />

and living: “There has been a<br />

dramatic change in life. Where<br />

the indigenous communities<br />

10 GLOBAL UNDERTONES / globalundertones.com

used to collect fruit and animals,<br />

now they are not able to. Now<br />

everything is bought. They live<br />

more of a white lifestyle, try to<br />

own a little store, or work with<br />

the oil companies” [xxiv].<br />

This lifestyle also requires<br />

these communities to enter<br />

the workforce whereas many<br />

were previously self-sufficient.<br />

Many of them have only a basic<br />

education and often experience<br />

language and cultural barriers in<br />

their interactions. As such, many<br />

now live in a state of constant<br />

uncertainty, or preocupacion<br />

as they are not able to secure<br />

who are treated unfairly, or who<br />

do not get the benefits they were<br />

promised. Additionally, there are<br />

those who haven’t been hired<br />

at all, but distinctly remember<br />

being promised jobs, but never<br />

received call backs. One woman<br />

explains: “I used to work at one<br />

of the oil companies, and I got<br />

pregnant. When they found out<br />

I was pregnant they fired me. I<br />

know its illegal, but what could<br />

I do” [xvi].<br />

Another woman comments: “I<br />

used to work at one of the oil<br />

companies. When I used to work<br />

there my daughter got shot. She<br />

operating in the south adhere to<br />

the ILO standards.<br />

Additionally, the stories told<br />

by these women are supported by<br />

the findings in a public hearing<br />

against the oil company Pacific<br />

Rubiales, which concluded<br />

that, “To a large extent, PRE<br />

[Pacific Rubiales Energy] avoids<br />

hiring employees directly by<br />

contracting with other companies.<br />

These companies then hire<br />

‘subcontractors’ who are, in all<br />

but name, employees on 28-day<br />

renewable contracts. The result<br />

is a precariously employed<br />

workforce” [xxviii]. Furthermore,<br />

the report finds that Pacific “is<br />

cited for unethical behavior,<br />

including the use of contractors<br />

and employment agencies as a<br />

strategy to avoid liability under<br />

labor laws” [xxix]. The result<br />

has been not only a workforce,<br />

but an entire town that lives in<br />

precariousness on the brink of<br />

poverty.<br />

Photo Courtesy of Felicia Graham<br />

This photo was taken at the entrance of a resguardo or reserve on the outskirts of Puerto Gaitan where members of the<br />

Sikuani residents live. This reserve remains unpaved and without proper water or sanitation facilities<br />

employment to meet their basic<br />

living needs [xxv].<br />

Outside of the indigenous<br />

community, many local mestizo<br />

women and men also look for<br />

work with the oil companies to<br />

no avail as there simply are not<br />

enough jobs. Those who are able<br />

to work for the industry wait for<br />

months, obtaining contracts that<br />

last no longer than 3-4 months.<br />

There are other stories too, of<br />

women working for the companies<br />

Summer 2014<br />

is now handicapped because<br />

of that. I was supposed to get<br />

benefits from the company for<br />

this, but they told me I needed<br />

to write a letter, and then they<br />

fired me” [xxvii].<br />

Though hiring for temporary<br />

contracts is outlawed in the<br />

standards outlined by the<br />

International Labor Organization<br />

(ILO), of which Colombia is<br />

party to, there are no physical<br />

means to ensure that companies<br />

Superficial development<br />

Furthermore, with the selling<br />

of the Sikuani territory, most<br />

indigenous community members<br />

now live in resguardos, or<br />

reserves, as there were no<br />

alternative residences set up<br />

by either the state or the oil<br />

company until 2009. Despite the<br />

influx of plata from the industry,<br />

however, these resguardos are<br />

generally considered to be subpar.<br />

When this field research was<br />

conducted in 2013, the resguardos<br />

were still being constructed, and<br />

it was clear that little effort had<br />

11

een invested in making these<br />

houses livable for the 450 Sikuani<br />

residents.<br />

Most buildings remain unfinished<br />

after 4 years, and most if not<br />

all are built with plastic tarp.<br />

There is also no pavement in the<br />

resguardo, nor proper sanitation<br />

infrastructure or running water<br />

– though much of Puerto Gaitan<br />

enjoys these luxuries, particularly<br />

in the town center where the<br />

mayor’s office resides.<br />

One Sikuani member commented<br />

While that may be true, the use<br />

of walls has a dubious history<br />

throughout the world –whether<br />

gated communities, the Berlin<br />

Wall, the U.S.-Mexican border,<br />

and the various walls dividing<br />

Palestinians and Israelis. Many<br />

Sikuani tend to share this suspicion,<br />

and it would seem likely that the<br />

wall’s true purpose is to hide<br />

the half-constructed indigenous<br />

reservation—in other words: out<br />

of sight, out of mind.<br />

Outside of the wall, however,<br />

for being just that – a medical<br />

center. There are actually no<br />

doctors to serve the town of now<br />

40 to 50,000: “They don’t even<br />

have professional doctors, just<br />

students who go to finish their<br />

residency training. And in the<br />

rural areas they still don’t have<br />

any access to schools, education,<br />

or hospitals” [xxxi]. For real<br />

treatment it’s necessary to make<br />

a three-hour journey northward<br />

to the neighboring city, but, “the<br />

municipality is not prepared for<br />

an emergency” [xxxii].<br />

“Turning a blind eye”<br />

Photo Courtesy of Felicia Graham<br />

The Rio Manacacias or Manacacias River is a main source of fish for the community. With the arrival of the oil industry,<br />

many people now claim that the water is contaminated, not only from chemicals, but from dust. In this picture, a cloud of<br />

on the resguardos as follows: “We<br />

used to be free to travel in the<br />

territory…. With the companies,<br />

now the indigenous communities<br />

feel they are enclosed, they have<br />

little territory, where they view<br />

their ancestral lands from afar<br />

that they no longer have” [xxx].<br />

What is perhaps most interesting,<br />

however, was that in addition to<br />

the lack of care that seems to have<br />

been put into the resguardo’s<br />

construction, the erection of a<br />

cement wall dividing the resguardo<br />

and the residents of Puerto Gaitan<br />

is in the process of being built<br />

for the ‘cultural preservation’ of<br />

the Sikuani community.<br />

life seems notably different.<br />

People bustle amid the dust and<br />

never-ending procession of oil<br />

tank trucks relatively unhindered,<br />

and many express pride in the<br />

newly paved roads and flashy<br />

buildings. Yet, these developments<br />

too are superficial.<br />

For example, much money has<br />

been invested in the local medical<br />

center. They have new equipment,<br />

and another investment is expected<br />

to bring more materials in next<br />

year. The problem is, however,<br />

not the lack of equipment, but<br />

the lack of doctors.<br />

In Puerto Gaitan, people typically<br />

joke about the medical center<br />

Though issues of environmental<br />

degradation, job insecurity, and<br />

superficial development projects<br />

are fairly easy to observe, other<br />

side effects from the oil industry<br />

are not so easy to quantify.<br />

Reflective of many community<br />

member’s opinions, one stated,<br />

“Since the company came there is<br />

much more social disintegration,<br />

and disintegration of the family…<br />

the people now invest much money<br />

in liquor… Fathers don’t have<br />

responsibilities anymore and it<br />

is common to see children on the<br />

street without anyone caring for<br />

them. And prostitution.. It was<br />

not seen before, but since the oil<br />

companies have arrived they are<br />

more open to the outside world”<br />

[xxxiii].<br />

These types of impacts from<br />

resource industries are often<br />

neglected, and hardly if ever<br />

make it into the environmental<br />

and social impacts assessment<br />

12 GLOBAL UNDERTONES / globalundertones.com

surveys that companies operating<br />

in Colombia are required to<br />

produce. Yet they constitute some<br />

of the most structural and deepseated<br />

changes that communities<br />

endure as a result of extraction.<br />

As Anthony Bebbington aptly<br />

remarks in his 2012 book Social<br />

Conflict, Economic Development,<br />

and Extractive Industry, “resource<br />

extraction often leaves footprints<br />

on individual and community<br />

consciousness that are not<br />

easily erased and become deeply<br />

embedded over time. Patterns of<br />

distrust emerge and are awakened<br />

during social movements” [xxxiv].<br />

As of yet, the international<br />

community has yet to pay notice<br />

to these critical changes.<br />

Conclusions<br />

Thus, the economic opening<br />

of 21st century Colombia that is<br />

claiming to bring the country into<br />

‘modernity’ [xxxv] does not resolve<br />

the deeply embedded conflicts<br />

of the previous century, or the<br />

newly arrived social problems.<br />

Patricia Vasquez explains, the<br />

underlying dynamics of conflict,<br />

particular[ly] around oil and gas,<br />

are “old, unresolved grievances…<br />

[which] if not addressed properly<br />

and in a timely fashion… can have<br />

regional – and sometimes even<br />

nationwide – impacts” [xxxvi ].<br />

Given the 21 st century’s global<br />

rush for natural resources and<br />

the consequent expansion of<br />

extractive industries across much<br />

of the developing world, from<br />

Africa to Latin America and Asia,<br />

Summer 2014<br />

many are now starting to take a<br />

closer look at the ways in which<br />

resource extraction transforms<br />

lives, livelihoods, and entire<br />

communities, particularly, but<br />

not solely in Latin America.<br />

The 2009 film “Crude,” for<br />

example, brought international<br />

attention to the struggle in<br />

Ecuador between 30,000 Cofan<br />

”<br />

Ecuadorian Cofan indigenous<br />

membersand Chevron-Texaco.<br />

Chevron-Texaco dumped over<br />

18 billion gallons of extractive<br />

crude waste over the span of<br />

a decade, which seeped into<br />

the foliage and water supply<br />

eventually killing off animals<br />

and causing extreme skin rashes<br />

and cancer in youth as young as<br />

17-18 years old [xxxvii]. A series<br />

of protests rocked the country and<br />

brought international criticism<br />

to the Ecuadorian government’s<br />

commitment to human and<br />

indigenous rights.<br />

Similarly, communities<br />

surrounding Peru’s Rio Blanco<br />

copper project voted unanimously<br />

against the proposal and protested<br />

[xxxviii] the government’s<br />

insistence that the project go<br />

through: “Protests erupted in<br />

2004 and 2005, in which two<br />

people were killed. A report was<br />

later released on the incident<br />

‘accusing the police and mine<br />

company security forces of<br />

illegally holding and torturing 28<br />

protestors… and includes graphic<br />

photos of bound prisoners, with<br />

plastic bags on their heads and<br />

wounds’” [xxxix].<br />

These struggles and many more<br />

like them continue to pop up<br />

throughout Latin America and<br />

the world to this very day, and<br />

“<br />

As of yet, the international community<br />

has yet to pay notice to these critical<br />

changes.<br />

will likely continue as long as<br />

governments embrace the rapid<br />

expansion of extractive industries<br />

for the benefit of the few, at the<br />

subtle expense of the majority<br />

In 2014, Colombia announced<br />

its intention to continue its<br />

extractive development project by<br />

the auction of 22 million hectares<br />

of land for oil exploration and<br />

production [xl]– roughly half the<br />

size of California and home to<br />

numerous indigenous communities,<br />

internally displaced communities,<br />

and rural farmers.<br />

If the Colombian government<br />

wishes to continue this<br />

development, it is essential<br />

that they more closely manage<br />

the changes the industry brings<br />

to communities, especially in<br />

regards to those it overlooks or<br />

excludes. If not, it is likely that<br />

Colombia may witness the same<br />

social conflicts as its extractive<br />

neighbors, but more critically<br />

risking a relapse into the systemic<br />

violence of the previous century.<br />

sources<br />

13

Photo Courtesy of Debra Sweet<br />

Protestors at an anti-war rally in Chicago on March 19, 2012<br />

criticize use of drone warfare in American foreign policy.<br />

14 GLOBAL UNDERTONES / globalundertones.com

World<br />

By Jacob Marthaller<br />

Alienation<br />

and our lives withdrones<br />

Arendt and Habermas’ Solutions<br />

February 2002, a mysterious flying<br />

object killed three Afghani men<br />

looking for scrap metal in the remote<br />

region of Zhawar Kili [i]. To be sure, this<br />

would not be the last mysterious killing,<br />

as the use of unmanned aerial vehicles<br />

(UAVs, more commonly known as drones)<br />

for lethal purposes would signal a new era<br />

of US counterterrorism policy. A little over<br />

a decade later, the United States remains<br />

adamant in their usage of drones in the<br />

War on Terror.<br />

While drones have been the target of<br />

countless protests in the last ten years,<br />

activists have made relatively little<br />

ground in mediating them [ii]. This article<br />

suggests that one of the chief reasons for<br />

this lack of progress is the United States’<br />

strict adherence to secrecy and their<br />

unwillingness to engage with the public<br />

in regards to drone policies.<br />

Before delving any deeper into this topic<br />

an indispensible caveat should be noted. For<br />

the purposes of this paper, only non-military<br />

drones piloted by civilian agencies (such<br />

as the CIA) will be examined at length.<br />

Although they are utilized in much the<br />

same way as non-military drones, military<br />

drones and the policies that regulate them<br />

are appropriately confidential, as American<br />

law and international military conventions<br />

sanction their classified status [iii].<br />

Summer 2014<br />

15

While compelling arguments<br />

have been made against the use of<br />

military drones as well, this essay<br />

cannot undertake such a broad<br />

focus and instead questions only<br />

non-military lethal UAVs used<br />

covertly outside of designated<br />

military zones [iv].<br />

Despite the fact that US<br />

drones and drone strikes seem<br />

to be increasing in number, the<br />

public still possesses relatively<br />

little information about them.<br />

This style of foreign policy—<br />

marked by political secrecy—is<br />

indeed a troubling aspect of the<br />

American drone strategy, as is<br />

the general lack of oversight into<br />

non-military drone programs. If<br />

drones are the future of American<br />

counterterrorism efforts, then<br />

their use should be monitored<br />

and overseen by the general<br />

population.<br />

To work against these notions<br />

of governmental secrecy,<br />

this article examines and<br />

elaborates on how two relatively<br />

contemporary political thinkers—<br />

the philosophers Hannah Arendt<br />

and Jürgen Habermas—would<br />

view drones and what they<br />

would recommend citizens do to<br />

ameliorate the American drone<br />

program.<br />

While neither thinker engages<br />

drones directly in their work, they<br />

both offer ways that citizens can<br />

work with their governments to<br />

“<br />

If drones are the future of<br />

American counterterrorism efforts,<br />

then their use should be monitored<br />

and overseen by the general<br />

population.<br />

”<br />

make political change, ultimately<br />

leading to better policies for all.<br />

Again, the scope of this piece<br />

remains with covert non-military<br />

drone use, as this is where Arendt’s<br />

concerns over political secrecy<br />

become most apparent and where<br />

Habermas’ prescriptions hold<br />

the most weight.<br />

A new kind of warfare<br />

While UAVs have only recently<br />

gained notoriety in the media, their<br />

use (particularly in surveillance)<br />

has been a common feature of<br />

American military campaigns and<br />

foreign policy since the beginning<br />

of the twentieth century [v].<br />

However, this surveillance strategy<br />

would be radically altered after<br />

9/11, when President George W.<br />

Bush began equipping drones for<br />

combat missions, carrying out<br />

the first lethal strike in February<br />

2002 [vi].<br />

After this strike, the US expanded<br />

the drone program into Yemen in<br />

November 2002, conducting their<br />

first strike there on an al-Qaida<br />

member who was thought to<br />

be involved in the USS Cole<br />

bombing; a terrorist attack that<br />

claimed seventeen American lives<br />

in 2000 [vii]. Despite several<br />

UN officials condemning this<br />

drone strike as illegal, the Bush<br />

administration expanded the<br />

US’s drone presence to Pakistan<br />

and Somalia as well, a policy<br />

that remained unchanged when<br />

Barack Obama took office [viii].<br />

Although he initially hoped<br />

to curtail the drone program,<br />

President Obama’s use of<br />

UAVs has in fact exceeded his<br />

predecessor’s. According to one<br />

source, the Bush administration<br />

had been responsible for 45-51<br />

drone strikes [ix], while Barack<br />

Obama’s presidency has (at<br />

the time of writing) authorized<br />

approximately 390 [x].<br />

Drones have become a standard<br />

fixture in both President Bush’s<br />

and Obama’s War on Terror.<br />

With this technology, drones<br />

offer personnel an unprecedented<br />

level of safety, as the possibility<br />

of endangering human lives by<br />

deploying them into combat is<br />

almost completely eliminated.<br />

However, these benefits have<br />

come at the price of public<br />

outcry and international debate<br />

as to whether counterterrorism<br />

measures should be carried out<br />

16 GLOBAL UNDERTONES / globalundertones.com

this remotely, as well as if the<br />

public should have more knowledge<br />

of these measures—themes that<br />

have been examined in various<br />

ways by Hannah Arendt.<br />

Hannah Arendt: World<br />

alienation and political<br />

obscurity<br />

Well known for her work on the<br />

rise of totalitarianism and how it<br />

affects individual citizens within<br />

Image first published by the National Journal<br />

a government, Hannah Arendt is<br />

unquestionably one of the most<br />

highly revered political theorists<br />

of the twentieth century. Although<br />

the subjects she takes up in her<br />

work are vast, two unifying themes<br />

emerge throughout her writings:<br />

violence and the motivation<br />

Summer 2014<br />

behind those who perpetrate it.<br />

In looking at how Arendt would<br />

view American drone policies,<br />

these themes must be a facet of<br />

the conversation, as they help<br />

to direct both how individuals<br />

can view drones and what can<br />

be done to mediate their usage.<br />

Without a doubt, Hannah Arendt<br />

would not have a favorable<br />

outlook on the use of drones in<br />

the War on Terror. Although she<br />

rarely wrote explicitly on military<br />

technology or prohibiting certain<br />

means of warfare [xi], she often<br />

discussed how technology could<br />

alter society as a whole and<br />

how it could change humanity’s<br />

perception of itself.<br />

Using the satellite Sputnik<br />

as an example, Arendt wrote<br />

that modern technology has the<br />

ability to distance humankind<br />

from their own world—what<br />

she called “world alienation”—<br />

subsequently distorting their<br />

conception of physical and<br />

metaphysical reality and with<br />

it their perception of humanity<br />

[xii]. Put another way, Arendt<br />

thought that modern technology,<br />

like drones, could create too<br />

much distance between human<br />

beings, and that the use of this<br />

technology could potentially<br />

erode the “anthropocentric”<br />

worldview prevalent in Western<br />

society [xiii].<br />

Though Arendt wrote this<br />

with mid-twentieth century<br />

technology in mind, its relevance<br />

to the contemporary use of<br />

drones is striking: in utilizing<br />

UAV technology, combatants<br />

are removed from the imminent<br />

danger that is inherent to ground<br />

combat. Birds-eye vision and<br />

bird-eye judgments take the<br />

place of tactical, on-the-ground<br />

decisions, thereby introducing an<br />

unparalleled degree of separation<br />

between aggressor and target that<br />

could lead to countless civilian<br />

deaths. For Arendt, judgments<br />

made through such a panoramic<br />

lens are proof of technology’s<br />

capacity to “decrease the stature<br />

of man” [xiv]; thus, one should<br />

be cautious of decisions made<br />

in this way [xv].<br />

While the US may have legitimate<br />

national security interests in<br />

maintaining the secrecy of the<br />

drone program, Arendt thought<br />

governmental obscurity was<br />

17

problematic as a whole, and she<br />

recognized that the disingenuous<br />

nature of “lying in politics”<br />

can be detrimental to a state’s<br />

relationship with its citizens [xvi].<br />

The obscure nature of the drone<br />

program becomes most apparent<br />

in discussions of noncombatant<br />

deaths and how targets are selected.<br />

In other words, the public lacks<br />

may simply look suspicious—has<br />

received ample negative attention<br />

from many sources [xx].<br />

In addition to never releasing the<br />

criteria for how these signature<br />

strike targets are determined,<br />

the Obama administration has<br />

rarely addressed whether strikes<br />

have been made in this way<br />

at all. While they have been<br />

political leaders, subsequently<br />

allowing those leaders to maintain<br />

a degree of distance from their<br />

work in order that certain actions<br />

could be performed on behalf of<br />

the state without anyone’s ethics<br />

impeding them. Eventually,<br />

those governing become so<br />

dissociated from their actions<br />

that they no longer acknowledge<br />

“<br />

For the United States to begin correcting<br />

these policies, it will have to recognize its<br />

complacency and come out from behind the<br />

bureaucratic veil.<br />

”<br />

knowledge of how drones are<br />

being used strategically [xvii].<br />

Not surprisingly, scholars and<br />

journalists alike have criticized<br />

the US government for their<br />

lack of disclosure in addressing<br />

specific components of drone<br />

strikes, as well as their persistence<br />

in “prevent[ing] journalists or<br />

researchers from consistently<br />

reporting on each individual<br />

strike” [xviii].<br />

Due to either implicit or explicit<br />

government censorship, there<br />

has been significant difficulty<br />

in obtaining accurate death tolls<br />

resulting from drone strikes,<br />

which in turn makes critiquing<br />

the efficacy of the drone program<br />

even more challenging [xix].<br />

Furthermore, America’s alleged<br />

use of “signature strikes”—where<br />

drone targets are selected based on<br />

particular lifestyle behaviors that<br />

dispelled to some degree [xxi],<br />

the continuing lack of sufficient<br />

information regarding signature<br />

strikes suggest, to some, an<br />

underlying atmosphere of secrecy<br />

surrounding American drone<br />

strategy [xxii].<br />

Though this obscurity is<br />

discomforting in and of itself, the<br />

government’s surreptitiousness<br />

seems to be a microcosm of a<br />

problem more clearly stated in<br />

Arendt’s work: the complications<br />

that result from a government’s<br />

overreliance on bureaucracy.<br />

Through her work on the<br />

development of totalitarianism<br />

in the twentieth century, Arendt<br />

would write meticulously on<br />

how governmental bureaucracy<br />

affects a state. For Arendt,<br />

bureaucracy was a form of rule<br />

characterized by a circulation<br />

of orders advocated by obscure<br />

the consequences of their orders,<br />

especially violent ones.<br />

In the bureaucratic state,<br />

violent actions can be performed<br />

to achieve political ends with<br />

limited human interference, as<br />

many within the organization<br />

are viewed as nonentities in an<br />

“intricate system of bureaus in<br />

which no man, neither one nor<br />

the best, neither the few nor the<br />

many, can be held responsible”<br />

for what the state does [xxiii].<br />

A state like this is disconcerting<br />

at best, and such “invisible<br />

governments”, as Arendt calls<br />

them, are deeply troubling [xxiv].<br />

The United States’ drone policy,<br />

as it currently exists, appears to<br />

fall into just this kind of trouble.<br />

While the public possesses slightly<br />

more information concerning<br />

drone practices than they have<br />

in recent years, an overall<br />

18 GLOBAL UNDERTONES / globalundertones.com

understanding of the way drones<br />

have been employed in the War on<br />

Terror by civilian agencies has never<br />

been made public. For the United<br />

States to begin correcting these<br />

policies, it will have to recognize<br />

its complacency and come out from<br />

behind the bureaucratic veil.<br />

First and foremost for Arendt,<br />

it is imperative that a government<br />

encourages its citizens to participate<br />

in the public realm, and she insists<br />

on a political environment where<br />

participants are free to create<br />

a self-conscious understanding<br />

of an issue and/or its need for<br />

improvement [xxv]. For Arendt,<br />

this necessitates what she comes<br />

to call the “space of appearance”,<br />

Photo Courtesy of Arc of Justice<br />

One of the few US anti-drone rallies held on January 30, 2013 in Washington, D.C.<br />

a communal action in which the<br />

public takes an inadequate political<br />

idea and restores it for better use<br />

[xxvi].<br />

Rather than obscuring a political<br />

idea or policy with varying levels<br />

Summer 2014<br />

of bureaucratic ambiguity, Arendt<br />

would argue that introducing<br />

that idea to the general populace<br />

could correct it. Entrenched in<br />

secrecy as they currently exist,<br />

American drone policies diminish<br />

the possibility that the space of<br />

appearance can emerge, therefore<br />

diminishing the possibility that<br />

the space of appearance could<br />

improve them.<br />

While Arendt’s space of<br />

appearance as a way to publicly<br />

mediate governmental policies is<br />

useful, her method is often too<br />

abstract and can lack concrete<br />

prescription at times. To explicitly<br />

address the United States’<br />

non-military drone policies, a<br />

more immersed form of public<br />

deliberation may be necessary, one<br />

in which change comes through<br />

direct interaction of individuals<br />

seeking to find common ground.<br />

For this to take place, citizens must<br />

initiate something more closely<br />

resembling Jürgen Habermas’<br />

deliberative democracy to<br />

engage with and ameliorate<br />

drone policies.<br />

Habermasian<br />

deliberation<br />

Like Arendt, Habermas contends<br />

that a citizen looking to make<br />

political change must be visible<br />

in the public sphere. However,<br />

for Habermas, the best way<br />

for an individual to confront a<br />

governmental policy is with a<br />

method he calls “deliberative<br />

democracy”.<br />

Ideally, Habermas’ method<br />

leads to a rational exchange<br />

between conversation partners<br />

on a particular issue, thereby<br />

producing a reasonable solution<br />

that satisfies both parties’<br />

demands.<br />

For Habermas, deliberative<br />

democracy is the most efficient<br />

way a citizen can interact with<br />

the law in an attempt to change<br />

it, a process that will be useful<br />

in looking for ways the American<br />

citizenry could engage with its<br />

government to obtain a more<br />

moderate drone strategy.<br />

Unlike Arendt, Habermas has<br />

a relatively positive view of the<br />

way democracies can negotiate<br />

agreements for themselves.<br />

For him, this requires first<br />

and foremost that a segment<br />

of the population be involved<br />

with the legal institutions of a<br />

state [xxvii].<br />

Put simply, this type of discourse<br />

resembles an interaction between<br />

19

two individuals: while each<br />

holds to their own rationally<br />

legitimate position, both are<br />

willing to negotiate with each<br />

other to reach an accord. This<br />

“communicative freedom”, as<br />

Habermas calls it, can only take<br />

place when two people hold<br />

competing claims, both of which<br />

are reparable through the process<br />

of communicative action [xxviii].<br />

Although Habermas explains his<br />

theory as a conversation between<br />

individual political interlocutors,<br />

this is not to say that political<br />

action must always be a solitary<br />

endeavor. On the contrary,<br />

Habermas—like Arendt—holds<br />

that one’s communicative power<br />

is enhanced by membership in<br />

a particular group [xxix]. In<br />

this way, Arendt and Habermas<br />

share the belief that political<br />

action is best executed within a<br />

community, a notion that has been<br />

amply explicated by proponents<br />

of civil disobedience and political<br />

obligation [xxx].<br />

In a democratic political society,<br />

potential deliberators are free<br />

to involve themselves with the<br />

legal and political processes<br />

of the state in order to rectify<br />

deficient government institutions.<br />

In looking to how this method<br />

could be applied to drones,<br />

individual citizens and activist<br />

groups could engage with the<br />

legal and political institutions<br />

of the state—such as Congress<br />

or the courts—in order to reform<br />

drone practices.<br />

Immediately one can see how<br />

Habermas modifies Arendt’s<br />

thought: whereas for her the<br />

establishment of a space within<br />

which political actors can engage<br />

with governments is paramount,<br />

Habermas outlines how such an<br />

exchange should work. While<br />

Arendt emphasizes that citizens<br />

must be visible in the public sphere<br />

(more classical conceptions of<br />

political protest come to mind),<br />

Habermas would say that potential<br />

political actors must be engaged<br />

with governmental institutions<br />

through communication, not<br />

merely expressing their dissent<br />

outside of them [xxxi].<br />

For deliberative democracy<br />

to be successful on Habermas’<br />

terms, the representative bodies<br />

of the state must recognize the<br />

“general will” of the people<br />

[xxxii]. Once this general will<br />

“<br />

has been attained and recognized,<br />

the essence of a Habermasian<br />

interactive dialogue can take place<br />

[xxxiii]. Therefore, immersing<br />

oneself with the political order<br />

is the responsibility of every<br />

particular citizen.<br />

This is especially relevant to<br />

the attempted amelioration of<br />

drones; while numerous protests<br />

have been held in the last decade,<br />

the number of activists directly<br />

involved have been few in number,<br />

and greater percentages of the<br />

population may need to include<br />

themselves in the discourse<br />

before significant changes can<br />

be made.<br />

Like Arendt, Habermas contends<br />

that the possibility for engagement<br />

must always be available if this<br />

is to be an effective method; that<br />

is, the government with which the<br />

citizenry is attempting to interact<br />

with must not silence or shut out<br />

potential conversation partners.<br />

Again, both Arendt and Habermas<br />

hold that political action of this<br />

kind should take place in groups,<br />

as this is the most sufficient way<br />

to translate political ideology<br />

into “purposive action” [xxxiv].<br />

Once deliberative democracy<br />

Therefore, immersing oneself<br />

with the political order is the<br />

responsibility of every particular<br />

citizen.<br />

”<br />

takes this form, more tenable<br />

policies can be reached, ones<br />

that appeal to a wider breadth<br />

of the political community.<br />

At this point, the reader may<br />

be skeptical of how Habermas’<br />

vision could translate to practical<br />

reality. Haven’t past attempts<br />

at reforming drone policies—<br />

such as the efforts of Medea<br />

Benjamin and Code Pink, among<br />

20 GLOBAL UNDERTONES / globalundertones.com

many others—been largely<br />

unsuccessful? Furthermore, what<br />

exactly constitutes “successful”<br />

deliberative engagement? Indeed,<br />

these concerns are challenging but<br />

not insurmountable, as there are<br />

many ways in which the American<br />

public could engage with the<br />

US government to mitigate the<br />

latter’s drone policies.<br />

Avenues of change<br />

Beginning with public protest is<br />

a good place to start as it tracks<br />

rather well with the Arendtian-<br />

Habermasian schema outlined<br />

above. In essence, Arendt and<br />

Habermas’ perspectives call<br />

for individuals to immerse<br />

themselves in these issues as<br />

much as possible, as immersion<br />

itself can easily be viewed as a<br />

form of public protest.<br />

For Arendt this means being<br />

visible within a public debate<br />

while for Habermas it means<br />

discussing one’s political<br />

values. In this sense, one can<br />

participate in a political protest<br />

in numerous ways; for example,<br />

Internet activism or writing to a<br />

congressman is potentially just<br />

as effective as picketing on the<br />

National Mall.<br />

The quintessential prescription<br />

that Arendt and Habermas offer to<br />

the everyday citizen is to engage<br />

with these issues. In this way, the<br />

question of how one will engage<br />

is directed back to that individual.<br />

However, for one’s involvement<br />

to be effective it would seem that<br />

Summer 2014<br />

the US government would first<br />

need to “come to the table”, so<br />

to speak, with their own rational<br />

and defensible position on drones.<br />

When something like this takes<br />

place, a more Habermasian form<br />

of deliberation will be possible.<br />

With that, this article suggests<br />

that the Obama administration<br />

openly embrace the American<br />

public as a dialogue partner in<br />

regards to non-military drone<br />

strategy. Doing this would<br />

require, at least to start, increased<br />

transparency of drone policies<br />

and practices. Indeed, President<br />

Obama seems to have taken steps<br />

in this direction [xxxv], but this<br />

can only be the beginning of a<br />

long process to increase openness<br />

of drone use.<br />

In addition, other branches of<br />

the United States government<br />

should publicly deliberate on<br />

drones more frequently. Though<br />

two Congressional hearings were<br />

held on drones in 2010, meetings<br />

of this kind have been conducted<br />

sparingly, and Congress should<br />

hold further hearings on this<br />

subject [xxxvi].<br />

Finally, one of the most effective<br />

public demonstrations took place<br />

in 2012 when a group of twentyseven<br />

high-ranking Congressmen<br />

drafted a letter to the Obama<br />

administration requesting greater<br />

presidential transparency in the<br />

way drones are used [xxxvii].<br />

This letter brought drones to<br />

the attention of many and was<br />

a powerful form of protest, and<br />

more acts of its kind should<br />

be executed to further mediate<br />

drones and drone usage.<br />

With the continued and increased<br />

use of drones, the United States<br />

is currently on a foreign policy<br />

path that could lead to disrupted<br />

international alliances and global<br />

insecurity. This article has shown—<br />

via Hannah Arendt—that opposition<br />

to drone combat extends beyond<br />

merely the fear of robot soldiers,<br />

and questions the very nature of how<br />

citizens interact with technology<br />

and political institutions.<br />

While the use of UAVs can<br />

be seen as questionable on both<br />

technological and political grounds,<br />

neither Arendt nor Habermas would<br />

consider leaving these tactics to<br />

their own devices. Rather, both<br />

thinkers call for a society that<br />

addresses the apparent problems<br />

of their state to promote global<br />

justice—the former arguing that a<br />

visible public sphere is crucial for<br />

change while the latter explains<br />

the ways in which a political<br />

discourse could take place.<br />

With that, it is imperative to<br />

state that this paper can only<br />

serve as an introduction into the<br />

larger conversation about the<br />

legitimacy of non-military drone<br />

use. It is only when a multitude<br />

of individuals commit themselves<br />

to mediating these political ideas<br />

that more agreeable policies will<br />

be found. Therefore, citizens must<br />

step forward into this conversation<br />

for themselves, bringing their own<br />

rational political values to the<br />

public sphere in order to make<br />

substantial change.<br />

sources<br />

21

By Sergey Salushev<br />

Crimea’s Succession<br />

History Before Politics<br />

22 GLOBAL UNDERTONES / globalundertones.com

Ethnic Russians demonstrate<br />

in the Crimean city<br />

of Simferopol with banners<br />

calling for “yes” vote to<br />

join Russia, 2014.<br />

Courtesy of Forbes<br />

After months of impassioned protests and<br />

violent clashes with the riot police on the<br />

Maidan (Independence Square), Ukraine’s<br />

legitimately elected, albeit unpopular,<br />

government of President Viktor Yanukovych<br />

was finally ousted from power in February.<br />

Summer 2014<br />

23

In the weeks following the<br />

overthrowing of the Ukrainian<br />

government, the pro-Russian<br />

political and paramilitary forces<br />

in the Autonomous Republic<br />

of Crimea, which historically<br />

enjoyed very strong ties to<br />

Russia, emulated protests in<br />

the capitol and effectively took<br />

control of the peninsula. Then, in<br />

a hastily organized referendum,<br />

the majority of the peninsula’s<br />

Russia. Ideology and realpolitik<br />

theories have dominated the<br />

discourse on Crimea’s secession<br />

since.<br />

Indeed, an article recently<br />

published in The Economist<br />

magazine, entitled Diplomacy<br />

and Security after Crimea: The<br />

new world order, argued that<br />

Russian President Putin laid<br />

the foundation for a new world<br />

order by annexing Crimea from<br />

Russia’s annexation of Crimea<br />

was a spontaneous and promptly<br />

executed reaction to the political<br />

tumult that gripped Ukraine and<br />

threatened the strategic interests<br />

of Russia in the Black Sea.<br />

Moreover, the crisis in Crimea<br />

has very deep historic roots that<br />

supersede the present political<br />

upheavals. As such, the crisis was<br />

predicted a long time ago and<br />

surely could have been averted<br />

had it not been for the misguided<br />

attempts at ‘Ukrainization’ of the<br />

ethnic Russian community and<br />

the inept political interference<br />

of the United States and the<br />

European Union (EU).<br />

EU negotiations fail<br />

Ethnic Russians in Crimea celebrate the results of a hastily organized referendum on the Ukrainian peninsula’s future. The<br />

majority voted overwhelmingly in favour of seceding from Ukraine and re-uniting with Russia.<br />

Courtesy of AFP-JIJI<br />

ethnic Russians voted to secede<br />

from Ukraine and reunite with<br />

Russia.<br />

Russia, much to dismay of the<br />

United States and the European<br />

Union, obliged the will of the<br />

people and absorbed the territory<br />

into the country’s sovereign<br />

borders. This controversial<br />

decision sparked a storm of<br />

speculations and suppositions<br />

which suggested that Russia’s<br />

actions in Crimea were part of<br />

a premeditated stratagem of a<br />

resurgent and more belligerent<br />

Ukraine [i]. Or, in other words,<br />

Putin set the country on the<br />

course of inevitable confrontation<br />

with American and European<br />

geopolitical and security interests<br />

on the continent.<br />

Of course, Russia’s annexation of<br />

Crimea on March 18 2014, clearly<br />

violated the territorial integrity<br />

of Ukraine and undermined<br />

international norms concerning<br />

principles of national selfdetermination.<br />

However, it did not<br />

represent the strategic move the<br />

Economist article suggests [ii].<br />

Before Ukraine’s uprising<br />

in 2014, the vast majority of<br />

Ukrainians were frustrated by<br />

pervasive state corruption, inept<br />

governance, and widespread<br />

poverty, among other things.<br />

These frustrations reached a<br />

peak of despair when President<br />

Viktor Yanukovych refused to<br />

sign an association agreement<br />

with the EU citing unfair terms of<br />

such an agreement for Ukraine’s<br />

economy. This rejection was<br />

widely interpreted as a veiled<br />

promise of eventual integration<br />

into the Russian economic zone.<br />

Fearing for the economic<br />

future of the country, tens of<br />

thousands of Ukrainians occupied<br />

the Independence Square in the<br />

country’s capital – Kiev, in order to<br />

exert pressure on the government<br />

to sign an association agreement<br />

24 GLOBAL UNDERTONES / globalundertones.com

with the EU. Consequently, the<br />

protests on the Independence<br />

Square in central Kiev were<br />

dubbed Euromaidan.<br />

These protests received an<br />

outpouring of support both<br />

domestically and internationally.<br />

Indeed, according to the poll<br />

published by the Pew Research<br />

Center - <strong>Global</strong> Attitudes Project,<br />

many people in the Russian<br />

speaking regions of the country<br />

favored unity and eventual<br />

integration into the EU [iii]. .<br />

After all, “the EU is Ukraine’s<br />

largest trading partner”[iv].<br />

Irrespective of linguistic and<br />

ethnic differences, many Ukrainian<br />

citizens understood that in the<br />

long term, association and free<br />

trade with the EU would offer<br />

a broad range of economic and<br />

political advantages, far more<br />

beneficial than forging closer<br />

links with Russia. Indeed,<br />

Ukrainians were wary of reliance<br />

on Russia given its economy’s<br />

structural inefficiency and rampant<br />

corruption in the government.<br />

However, at times explicitly<br />

anti-Russian and nationalistic<br />

undertones of the Maidan protests<br />

have tarnished the credibility of<br />

the uprising and alarmed otherwise<br />

politically apathetic ethnic<br />

Russians living in Ukraine. In<br />

short, the modern revolt against<br />

state corruption had suddenly<br />

unearthed decades-old historic<br />

resentments that divided the<br />

country along the fault-lines of<br />

ethnicity, religion and language.<br />

The West responds<br />

The actions of the American<br />