the world of private banking

the world of private banking

the world of private banking

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

LONDON’S FIRSt ‘BIG BANG’? 83<br />

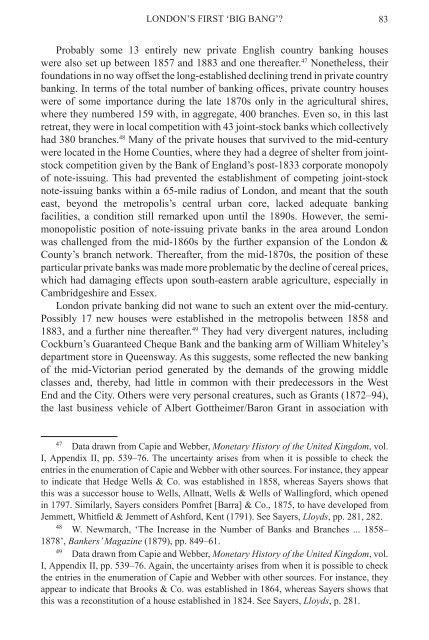

Probably some 13 entirely new <strong>private</strong> English country <strong>banking</strong> houses<br />

were also set up between 1857 and 1883 and one <strong>the</strong>reafter. 47 None<strong>the</strong>less, <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

foundations in no way <strong>of</strong>fset <strong>the</strong> long-established declining trend in <strong>private</strong> country<br />

<strong>banking</strong>. In terms <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> total number <strong>of</strong> <strong>banking</strong> <strong>of</strong>fices, <strong>private</strong> country houses<br />

were <strong>of</strong> some importance during <strong>the</strong> late 1870s only in <strong>the</strong> agricultural shires,<br />

where <strong>the</strong>y numbered 159 with, in aggregate, 400 branches. Even so, in this last<br />

retreat, <strong>the</strong>y were in local competition with 43 joint-stock banks which collectively<br />

had 380 branches. 48 Many <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>private</strong> houses that survived to <strong>the</strong> mid-century<br />

were located in <strong>the</strong> Home Counties, where <strong>the</strong>y had a degree <strong>of</strong> shelter from jointstock<br />

competition given by <strong>the</strong> Bank <strong>of</strong> England’s post-1833 corporate monopoly<br />

<strong>of</strong> note-issuing. This had prevented <strong>the</strong> establishment <strong>of</strong> competing joint-stock<br />

note-issuing banks within a 65-mile radius <strong>of</strong> London, and meant that <strong>the</strong> south<br />

east, beyond <strong>the</strong> metropolis’s central urban core, lacked adequate <strong>banking</strong><br />

facilities, a condition still remarked upon until <strong>the</strong> 1890s. However, <strong>the</strong> semimonopolistic<br />

position <strong>of</strong> note-issuing <strong>private</strong> banks in <strong>the</strong> area around London<br />

was challenged from <strong>the</strong> mid-1860s by <strong>the</strong> fur<strong>the</strong>r expansion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> London &<br />

County’s branch network. Thereafter, from <strong>the</strong> mid-1870s, <strong>the</strong> position <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se<br />

particular <strong>private</strong> banks was made more problematic by <strong>the</strong> decline <strong>of</strong> cereal prices,<br />

which had damaging effects upon south-eastern arable agriculture, especially in<br />

Cambridgeshire and Essex.<br />

London <strong>private</strong> <strong>banking</strong> did not wane to such an extent over <strong>the</strong> mid-century.<br />

Possibly 17 new houses were established in <strong>the</strong> metropolis between 1858 and<br />

1883, and a fur<strong>the</strong>r nine <strong>the</strong>reafter. 49 They had very divergent natures, including<br />

Cockburn’s Guaranteed Cheque Bank and <strong>the</strong> <strong>banking</strong> arm <strong>of</strong> William Whiteley’s<br />

department store in Queensway. As this suggests, some reflected <strong>the</strong> new <strong>banking</strong><br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> mid-Victorian period generated by <strong>the</strong> demands <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> growing middle<br />

classes and, <strong>the</strong>reby, had little in common with <strong>the</strong>ir predecessors in <strong>the</strong> West<br />

End and <strong>the</strong> City. O<strong>the</strong>rs were very personal creatures, such as Grants (1872–94),<br />

<strong>the</strong> last business vehicle <strong>of</strong> Albert Got<strong>the</strong>imer/Baron Grant in association with<br />

47<br />

Data drawn from Capie and Webber, Monetary History <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> United Kingdom, vol.<br />

I, Appendix II, pp. 539–76. The uncertainty arises from when it is possible to check <strong>the</strong><br />

entries in <strong>the</strong> enumeration <strong>of</strong> Capie and Webber with o<strong>the</strong>r sources. For instance, <strong>the</strong>y appear<br />

to indicate that Hedge Wells & Co. was established in 1858, whereas Sayers shows that<br />

this was a successor house to Wells, Allnatt, Wells & Wells <strong>of</strong> Wallingford, which opened<br />

in 1797. Similarly, Sayers considers Pomfret [Barra] & Co., 1875, to have developed from<br />

Jemmett, Whitfield & Jemmett <strong>of</strong> Ashford, Kent (1791). See Sayers, Lloyds, pp. 281, 282.<br />

48<br />

W. Newmarch, ‘The Increase in <strong>the</strong> Number <strong>of</strong> Banks and Branches ... 1858–<br />

1878’, Bankers’ Magazine (1879), pp. 849–61.<br />

49<br />

Data drawn from Capie and Webber, Monetary History <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> United Kingdom, vol.<br />

I, Appendix II, pp. 539–76. Again, <strong>the</strong> uncertainty arises from when it is possible to check<br />

<strong>the</strong> entries in <strong>the</strong> enumeration <strong>of</strong> Capie and Webber with o<strong>the</strong>r sources. For instance, <strong>the</strong>y<br />

appear to indicate that Brooks & Co. was established in 1864, whereas Sayers shows that<br />

this was a reconstitution <strong>of</strong> a house established in 1824. See Sayers, Lloyds, p. 281.

![[Pham_Sherisse]_Frommer's_Southeast_Asia(Book4You)](https://img.yumpu.com/38206466/1/166x260/pham-sherisse-frommers-southeast-asiabook4you.jpg?quality=85)