i Report Issue No. 3 2005 - Philippine Center for Investigative ...

i Report Issue No. 3 2005 - Philippine Center for Investigative ...

i Report Issue No. 3 2005 - Philippine Center for Investigative ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

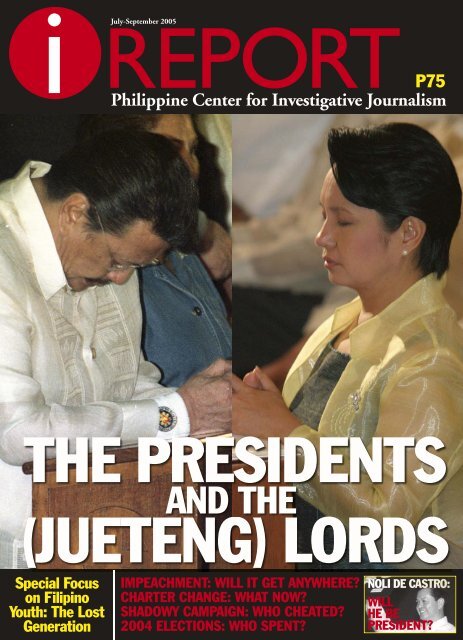

i REPORT<br />

July-September <strong>2005</strong><br />

P75<br />

<strong>Philippine</strong> <strong>Center</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Investigative</strong> Journalism<br />

THE PRESIDENTS<br />

AND THE<br />

(JUETENG) LORDS<br />

Special Focus<br />

on Filipino<br />

Youth: The Lost<br />

Generation<br />

IMPEACHMENT: WILL IT GET ANYWHERE?<br />

CHARTER CHANGE: WHAT NOW?<br />

SHADOWY CAMPAIGN: WHO CHEATED?<br />

2004 ELECTIONS: WHO SPENT?<br />

NOLI DE CASTRO:<br />

WILL<br />

HE BE<br />

PRESIDENT?

C O N T E N T S<br />

OVERVIEW<br />

ANAK NG JUETENG 2<br />

Sheila S. Coronel<br />

Like Joseph Estrada, Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo<br />

has been accused of accepting money from illegal<br />

gambling.<br />

THE CAMPAIGN<br />

JEKYLL-AND-HYDE CAMPAIGN 6<br />

Yvonne T. Chua<br />

Alongside the official Arroyo campaign was a<br />

parallel structure that operated secretly and with<br />

little accountability.<br />

PRESIDENTIAL MAKEOVER 10<br />

A <strong>for</strong>eign PR firm is re-engineering Mrs. Arroyo’s<br />

image.<br />

CAMPAIGN FUNDS<br />

RUNNING ON TAXPAYERS’ MONEY 12<br />

Luz Rimban<br />

Billions of pesos in government funds were<br />

used to pump prime Arroyo’s candidacy.<br />

THE VICE PRESIDENT<br />

THE MAN WHO WOULD BE PRESIDENT<br />

16<br />

Luz Rimban<br />

<strong>No</strong>li de Castro has come a long way from his<br />

days as a broadcaster; he may even end up in<br />

Malacañang.<br />

CHARTER CHANGE<br />

SOS: SYSTEM UNDER STRESS 20<br />

Sheila S. Coronel<br />

Can Congress be trusted to hold a credible impeachment<br />

trial and to change the constitution?<br />

IMPEACHMENT<br />

LIGHTS, CAMERA, IMPEACHMENT! 24<br />

Alecks P. Pabico<br />

The impeachment proceedings should be the<br />

best show in town, but so far, it’s been a sleeper.<br />

VOICES FROM THE PERIPHERY<br />

FOR VISAYANS,<br />

THE CENTER DOES NOT HOLD<br />

Resil Mojares<br />

THE MORO PEOPLE CAN BE PART<br />

OF A PLURAL SOCIETY WITHOUT<br />

LOSING THEIR IDENTITY<br />

28<br />

Omar Solitario Ali<br />

THE TIME FOR FEDERALISM<br />

IS NOW<br />

29<br />

Rey Magno Teves<br />

TWO AT EDSA<br />

“WHEN THE WHEELS OF HISTORY<br />

TURN, YOU HARDLY EXPECT THE<br />

WORLD TO TURN UPSIDE DOWN”<br />

Ed Lingao<br />

“I WAS AT EDSA OUT OF<br />

PURE DISGUST” 32<br />

Mylene Lising<br />

FOCUS ON FILIPINO YOUTH:<br />

THE LOST GENERATION<br />

FINDING SPACES 33<br />

Katrina Stuart Santiago<br />

They are the hi-tech generation, at ease with<br />

technology but otherwise lost when it comes<br />

26<br />

31<br />

to dealing with the complexities of a globalized<br />

world.<br />

SO YOUNG & SO TRAPO 36<br />

Avigail Olarte<br />

The Sangguniang Kabataan, training ground of<br />

future leaders, has fallen into the grip of traditional<br />

politics.<br />

TEEN & TIPSY<br />

40<br />

Vinia Datinguinoo<br />

More and more adolescent girls are drinking<br />

alcohol.<br />

PERILS OF GENERATION SEX 44<br />

Cheryl Chan<br />

Filipino women are having sex earlier, but are<br />

seldom aware of the risks, including sexually<br />

transmitted diseases.<br />

THE BEAUTY BUSINESS 46<br />

Cheryl Chan<br />

Shampoos, skin whiteners, and assorted other<br />

beauty products find a ready market among<br />

young women.<br />

MACHOS IN THE MIRROR 48<br />

Dean Francis Alfar<br />

Filipino men are spending millions to look—and<br />

feel—good.<br />

MALE & VAIN 50<br />

Photos by Jose Enrique Soriano<br />

Men are lining up to get facials, foot scrubs, and<br />

even dips in bathtubs filled with rose petals.<br />

GROWING UP FEMALE & MUSLIM 52<br />

Samira Gutoc<br />

Moro women still value religion and tradition,<br />

but are also responding to the challenges of<br />

modernity.<br />

VIRTUALLY YOURS 56<br />

Alecks P. Pabico<br />

Technology has redefined the barkada.<br />

Cover: Jueteng scandals have rocked two<br />

<strong>Philippine</strong> presidents, Joseph Estrada and<br />

Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo.<br />

Photo Credits: Malaya provided the photos<br />

<strong>for</strong> pages 2, 3, 4 (top photo), 10, 12, 14, 16-<br />

18, 20-22, 24-25, 35-39, and 46. Photos on<br />

pages 15 and 26 are by Laurent Duvillier. Joe<br />

Galvez took the photo of the jueteng gaming<br />

table on page 4. The photos of Ed Lingao on<br />

page 30 are courtesy of the author; that of<br />

Mylene Lising on page 31, also courtesy of<br />

the author, while Sid Balatan took the Edsa<br />

2 photo on that page. Sonny Yabao took the<br />

photos on pages 33 (top photo) and 34. The<br />

bottom photo on page 33 is from the National<br />

Youth Commission. The photos on pages 40-<br />

41 are by Vinia Datinguinoo; those on pages<br />

48-49 are by Jose Enrique Soriano; on page<br />

52 by Rick Rocamora, and on pages 56-58 by<br />

Alecks P. Pabico.<br />

CONFUSED CONFESSION<br />

Some of readers may be confused about<br />

our size. This year, i <strong>Report</strong> has come<br />

out two sizes: the book-sized version <strong>for</strong><br />

<strong>No</strong>.1 and 2 and the magazine-sized version<br />

you hold in your hand. The reason is<br />

simple: we started out thinking that we<br />

could stray away from the news and focus<br />

instead on long-term social, political,<br />

and lifestyle trends. But then Gloriagate<br />

broke out and we were proven so wrong.<br />

The tempo of the times required that<br />

we keep our readers abreast of current<br />

events. That entailed giving up the less<br />

timebound, book-sized i in favor of the<br />

more current, newsmagazine <strong>for</strong>mat.<br />

Our dealers have also asked that we<br />

keep to this size, as it is more visible<br />

on the newsstands and easier to sell.<br />

We will oblige them. Our apologies <strong>for</strong><br />

the confusion. We assure our readers<br />

that there will be no resizing of i in the<br />

<strong>for</strong>eseeable future. We know that you<br />

can take only so much uncertainty in<br />

this uncertain times.<br />

Feedback on the magazine is welcome.<br />

Email us at imag@pcij.org or fax us at<br />

929-3571.<br />

EDITOR Sheila S. Coronel<br />

DEPUTY EDITOR Cecile C.A. Balgos<br />

STAFF Yvonne T. Chua, Luz Rimban,<br />

Vinia M. Datinguinoo, Alecks P.<br />

Pabico, Avigail Olarte<br />

OFFICE MANAGER Fausta Cacdac<br />

BOARD OF EDITORS <strong>Philippine</strong> <strong>Center</strong><br />

<strong>for</strong> <strong>Investigative</strong> Journalism<br />

Lorna Kalaw-Tirol, Sheila S. Coronel,<br />

Marites Dañguilan Vitug, Malou<br />

Mangahas, Howie G. Severino, David<br />

Celdran, Ma. Ceres P. Doyo<br />

BOARD OF ADVISERS Jose V. Abueva,<br />

Jose F. Lacaba, Cecilia Lazaro, Tina<br />

Monzon-Palma, Sixto K. Roxas, Jose<br />

M. Galang<br />

Published by the <strong>Philippine</strong> <strong>Center</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Investigative</strong><br />

Journalism; 3/F Criselda II Building, 107 Scout de Guia<br />

Street, Quezon City 1104<br />

T 4194768 F 929-3571<br />

Email: Pcij@pcij.org; imag@pcij.org<br />

PHILIPPINE CENTER FOR INVESTIGATIVE JOURNALISM<br />

I REPORT<br />

1

SHEILA S. CORONEL<br />

NO TWO presidents<br />

could be<br />

more unlike each<br />

other. She is a<br />

workaholic with a<br />

PhD in economics.<br />

He is a college<br />

dropout and a movie actor<br />

who gets up at noon. She is most<br />

com<strong>for</strong>table speaking in English<br />

and spouting economic jargon.<br />

He grunts rather than speaks, and<br />

when he does, he prefers Tagalog<br />

of the kanto<br />

boy variety. But<br />

then he has a natural charm and<br />

is ef<strong>for</strong>tlessly popular; his mass<br />

appeal is undeniable.<br />

She, on the other hand, is<br />

charisma challenged. While<br />

he acts like one of the boys,<br />

she behaves like an unpopular<br />

schoolmarm. Low on mass appeal,<br />

she projects herself as a<br />

skilled, hands-on executive, an<br />

image attractive to the middle<br />

class and the business community,<br />

but otherwise unappealing<br />

to the skeptical masa.<br />

In terms of style, personality,<br />

career track, and even linguistic<br />

preference, no two presidents<br />

could be more different from<br />

each other than Gloria Macapagal-<br />

Arroyo and her predecessor Joseph<br />

Estrada. But there is one thing that<br />

they have in common: jueteng.<br />

The scandals that have rocked<br />

both their governments involve the<br />

illicit numbers game, and no matter<br />

what they do, they will never live<br />

down their association with it.<br />

Nearly four years ago, Ilocos<br />

Sur Gov. Luis ‘Chavit’ Singson<br />

told a stunned nation that Erap<br />

was the “lord of all jueteng<br />

lords,” setting off street protests<br />

and a compromised impeachment<br />

trial that led to the president’s<br />

ouster. Today Arroyo is<br />

also facing impeachment, accused,<br />

among other things, of<br />

using jueteng money to bankroll<br />

her campaign and to bribe election<br />

officials.<br />

One would think that history<br />

would not repeat itself so crudely,<br />

or so soon. But then a closer look<br />

at history reveals the deep roots<br />

that jueteng has in <strong>Philippine</strong><br />

social and political life. Jueteng<br />

thrives in the murky underworld<br />

where crime, politics, and poverty<br />

meet. It lives in the spaces where<br />

the rule of law is weak, where<br />

those who hold power are in the<br />

thrall of illicit money and wealth,<br />

and where the poor are made<br />

complicit in the structures that<br />

keep them powerless.<br />

Today we have, by all appearances,<br />

a very modern president,<br />

a Georgetown classmate of<br />

Bill Clinton who comports herself<br />

more like a technocrat than a politician.<br />

But the reality is that our<br />

politics has deep, feudal roots<br />

and Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo is<br />

as immersed in the sleazy world<br />

of traditional <strong>Philippine</strong> politics<br />

as her predecessor was. Despite<br />

the talk of re<strong>for</strong>m and the ability<br />

to appeal to the urban middle<br />

class and the globalizing sectors<br />

of the business community, she<br />

has done little to yank the political<br />

system out of its feudal roots.<br />

It now looks that she is as trapo<br />

as they come. Like Estrada, she<br />

is anak ng jueteng, the child of<br />

a political system as tired and as<br />

old as that illicit numbers game.<br />

Jueteng there<strong>for</strong>e is at least<br />

100 years old. Its language alone<br />

betrays its age. The word itself is<br />

Chinese, deriving from the characters<br />

hue<br />

(flower) and<br />

eng<br />

(to<br />

bet). But because the game was<br />

probably introduced by Chinese<br />

traders during the Spanish colonial<br />

era, its vocabulary is in Spanish:<br />

cabo<br />

<strong>for</strong> the chief collector,<br />

cobradores<br />

<strong>for</strong> the bet collectors,<br />

cobranza <strong>for</strong> the collection.<br />

Jueteng’s links to local politics<br />

is probably as old. In 1929, <strong>for</strong><br />

example, Mariano Arroyo, then<br />

the governor of Iloilo and the<br />

most powerful man in the province,<br />

was accused of coddling a<br />

Chinese jueteng lord and of operating<br />

a gambling den himself in<br />

order to raise money <strong>for</strong> the 1931<br />

VERY OLD AND VERY<br />

LUCRATIVE<br />

The first jurisprudence on jueteng,<br />

says lawyer Sonny Pulgar, dates<br />

back to 1905, when a U.S. judge<br />

in the <strong>Philippine</strong> Supreme Court<br />

upheld a lower court’s decision<br />

that found two individuals guilty<br />

of “unlawful gambling” in Malabon.<br />

The tribunal upheld the<br />

sentences: a fine of 625 pesetas<br />

and imprisonment of two months<br />

<strong>for</strong> the owner and “banker” of<br />

the gambling establishment and a<br />

325-peseta fine and a prison term<br />

of one month and a day <strong>for</strong> the<br />

woman caught betting there.<br />

2 PHILIPPINE CENTER FOR INVESTIGATIVE JOURNALISM I REPORT

O V E R V I E W<br />

Jueteng keeps the police<br />

running as well: police officers<br />

use bribes from gambling<br />

lords to buy gasoline <strong>for</strong> their<br />

vehicles, office supplies, even<br />

medicine <strong>for</strong> sick cops. In addition,<br />

jueteng provides jobs—one<br />

estimate is that it employs close<br />

to 150,000 people throughout<br />

Luzon. Its grassroots base includes<br />

millions, many of them<br />

poor people who bet P1 or more<br />

in a game of chance that has<br />

deep roots in popular folklore.<br />

In short, jueteng is a parallel<br />

government, funding the social<br />

services that government, if it<br />

were working properly, should<br />

be delivering. Jueteng may be<br />

the most organized and the most<br />

public racket in the country, but<br />

it serves a social function, too.<br />

For sure, it preys on the poor<br />

and keeps them trapped in<br />

relationships of patronage, but<br />

it also provides them with temporary<br />

relief from their misery.<br />

Jueteng is not a victimless crime.<br />

As the parade of witnesses in the<br />

Senate hearings since May have<br />

shown, jueteng corrupts, and<br />

corrupts absolutely, including<br />

possibly even the presidency.<br />

TWO OF A KIND? Both the<br />

Arroyo and Estrada presidencies<br />

have been tainted by their<br />

association with illegal gambling.<br />

JUETENG<br />

elections. Because of exposés that<br />

ran in a local paper, Arroyo was<br />

investigated and subsequently<br />

dismissed from his post. Mariano<br />

had a brother, Jose, whose<br />

grandson is Jose Miguel Arroyo,<br />

the president’s husband.<br />

This is by no means unusual.<br />

Over the years, the names<br />

of politicians who have been<br />

linked to jueteng reads like a<br />

who’s who of <strong>Philippine</strong> political<br />

families. The names of<br />

the Singsons of Ilocos, the Cojuangcos<br />

of Tarlac, the Josons<br />

of Nueva Ecija, the Villafuertes<br />

of Camarines Sur, the Lees of<br />

Sorsogon, and the Espinosas of<br />

Masbate have all been tainted,<br />

whether rightly or wrongly, by<br />

jueteng. Some of these families<br />

have been accused of protecting<br />

illegal gambling operators. Others<br />

have been known to operate<br />

jueteng networks themselves.<br />

Puerto Princesa Mayor Edward<br />

Hagedorn, one of the<br />

president’s staunchest supporters,<br />

is a self-confessed <strong>for</strong>mer<br />

jueteng big boss. The current<br />

Batangas governor, Armand<br />

Sanchez, now also an Arroyo<br />

loyalist, was on the list of gambling<br />

operators who regularly<br />

gave Estrada a cut from their<br />

collections. More recently, the<br />

Lapids of Pampanga—action<br />

star Lito, now senator, and his<br />

son Mark, the provincial governor—have<br />

been linked to illegal<br />

gambling as well, not so much as<br />

operators but as protectors and<br />

beneficiaries of one particularly<br />

notorious jueteng lord.<br />

In most of Luzon, jueteng is<br />

the lifeblood of local politics.<br />

It is a source of campaign contributions.<br />

During elections, its<br />

network of collectors doubles as<br />

a campaign machine. It is, more<br />

importantly, also a well of money<br />

that allows local officials to deliver<br />

patronage. A significant cut<br />

of jueteng profits passes from the<br />

gambling operator to the mayor,<br />

congressman, or governor, who<br />

in turn doles out some of the<br />

money to his or her constituents.<br />

For generations, voters have<br />

brought their supplications to<br />

politicians, who are seen as the<br />

local DSWD (Department of Social<br />

Welfare and Development).<br />

A MULTIBILLION-PESO<br />

INDUSTRY<br />

In 1995, Rep. Roilo Golez estimated<br />

that jueteng was an P18-<br />

billion-a-year industry. In 1999,<br />

retired <strong>Philippine</strong> National Police<br />

(PNP) Gen. Wilfredo Reotutar<br />

put the daily bets placed with<br />

jueteng operations in Luzon<br />

and the Visayas at P84 million<br />

a day, or about P30 billion<br />

a year. About a third of this<br />

amount—P25 million daily or P9<br />

billion a year—goes to protection<br />

money paid to government<br />

and police officials, Reotutar<br />

reported. In 2001, when Chavit<br />

Singson exposed his pal Erap’s<br />

jueteng links, the Ilocos Sur politico<br />

estimated the total jueteng<br />

collections from just 22 Luzon<br />

provinces at about P50 million a<br />

day or P18 billion a year.<br />

Wenceslao Sombero, a retired<br />

police colonel who was<br />

once chief of the Detective and<br />

Special Operations Office of the<br />

PNP’s Criminal Investigation<br />

and Detection Group (CIDG),<br />

estimated that in the post-Estrada<br />

era, jueteng had expanded to 27<br />

Luzon provinces, with operators<br />

raking in about P75 million in<br />

bets a day or about P27 billion<br />

a year. This is almost equal the<br />

2004 gross revenues of Fortune<br />

PHILIPPINE CENTER FOR INVESTIGATIVE JOURNALISM<br />

I REPORT<br />

3

Tobacco, the country’s biggest<br />

cigarette manufacturer, and is<br />

more than half the total sales that<br />

year of the country’s two biggest<br />

mobile-phone-services companies,<br />

Globe and Smart, which<br />

are roughly in the P50-billion<br />

range and are among the top 10<br />

companies in the country.<br />

Unlike the corporate Top<br />

1000, however, jueteng lords<br />

have low overheads, don’t pay<br />

taxes, and get cash collections<br />

on the spot, thanks to a network<br />

of cobradores. Jueteng is also<br />

a low-capital, low-tech operation;<br />

little investment in product<br />

innovation and research and<br />

development is needed. <strong>No</strong> advertising<br />

is required. Aside from<br />

its collectors, all it needs is the<br />

protection of officials.<br />

Although it had fallen into the<br />

pits of disrepute after Estrada,<br />

JUETENG WHISTLEBLOWER.<br />

Chavit Singson exposed<br />

Estrada’s jueteng links in<br />

2001, but the numbers<br />

game (below) still flourishes<br />

in many parts of the country.<br />

jueteng thrived in the post-Edsa<br />

2 period, when a few gambling<br />

lords, most notably the Pampangueño<br />

jueteng boss Rodolfo<br />

‘Bong’ Pineda, expanded and<br />

consolidated their operations.<br />

The complicity of the police and<br />

of local officials is partly to blame,<br />

because jueteng cannot operate<br />

without the tacit cooperation of<br />

law en<strong>for</strong>cers. But, police sources<br />

say, Pineda and the others were<br />

able to operate freely because<br />

of the perception that they were<br />

close to Malacañang and that the<br />

Palace was giving its blessings<br />

to their operations. Until the<br />

recent police crackdown in the<br />

wake of the Senate hearings, the<br />

signal being sent down the line<br />

was apparently that the present<br />

administration was okay with<br />

jueteng.<br />

JUETENG AND LOCAL<br />

POWER<br />

Jueteng’s intimate relationship<br />

with local power stems from its<br />

decentralized operations. The<br />

activities of a jueteng lord are<br />

confined to a town or a province;<br />

gambling operators do not cross<br />

jurisdictions, where they risk<br />

incurring the ire of rivals who<br />

have already been operating<br />

there <strong>for</strong> years. Moreover, jueteng<br />

is based on local knowledge:<br />

operators rely on a long-established<br />

network of cabos, usually<br />

respected local people whom<br />

they personally know and trust.<br />

It is hard to do that if one is an<br />

outsider or unable to speak the<br />

local language. Jueteng operators<br />

also invest in relationships with<br />

local officials and other local influentials,<br />

including parish priests<br />

and journalists. Outsiders would<br />

find it difficult to penetrate these<br />

local networks of trust.<br />

Unsurprisingly, the two presidents<br />

who have been linked to<br />

jueteng—Estrada and Arroyo—<br />

are also those with firm roots in<br />

small-town politics. Estrada was<br />

a longtime mayor of San Juan.<br />

He was mayor in the sense of<br />

a small-town boss, who took<br />

cuts from the illicit trades in his<br />

municipality, jueteng included.<br />

For Estrada, the presidency was<br />

the mayoralty writ large. This<br />

was why, according to Singson,<br />

just barely two months into his<br />

presidency, Erap already arranged<br />

to get a three-percent<br />

share from the collections of<br />

jueteng operators throughout<br />

the country. He apparently did<br />

the same <strong>for</strong> smuggling, according<br />

to his <strong>for</strong>mer finance secretary,<br />

Edgardo Espiritu. Estrada<br />

looked, and played, the part of<br />

gangster-president, and it was<br />

this that caused his ouster.<br />

While Arroyo herself did<br />

not spring from local politics<br />

as Estrada did, she has roots in<br />

Lubao, Pampanga, her father’s<br />

hometown and also the home<br />

base of jueteng uberlord Pineda,<br />

whose wife Lilia, a <strong>for</strong>mer Lubao<br />

mayor, is said to be a close presidential<br />

friend. <strong>No</strong> one can spend<br />

time in Lubao and not be aware<br />

of the tremendous hold that the<br />

Pinedas have there.<br />

Estrada’s relationship with<br />

jueteng operators was more<br />

like that of a mafia lord. It<br />

was a relationship motivated<br />

by pure greed: Estrada apparently<br />

thought that since jueteng<br />

bosses were making tons of easy<br />

money, there was no reason the<br />

president should not share in<br />

the loot. From the testimonies<br />

so far presented against her,<br />

Gloria Arroyo appears to have<br />

related to jueteng more like a<br />

politician than a godfather like<br />

Erap. Determined to contest the<br />

presidency in 2004 and anxious<br />

about her popularity, Arroyo,<br />

like many other politicians,<br />

apparently saw jueteng as a<br />

hard fact of <strong>Philippine</strong> political<br />

life—and that it could be used<br />

<strong>for</strong> electoral purposes.<br />

Unlike Estrada, who insisted<br />

on a share of gambling collections<br />

being delivered to him<br />

regularly, the testimonies so far<br />

given in the Senate hearings on<br />

jueteng point to presidential<br />

relatives—not President Arroyo<br />

herself—receiving far smaller<br />

(P500,000 monthly), but still<br />

regular, shares of jueteng collections<br />

from selected areas.<br />

Moreover, the collections were<br />

not aggregated nationally like<br />

they were during the Erap era<br />

(Estrada was alleged to have<br />

amassed P500 million in jueteng<br />

funds over a two-year period).<br />

There is there<strong>for</strong>e a difference in<br />

scale as well as purpose.<br />

To Arroyo, there is a difference<br />

in style as well. In 2001, after<br />

she assumed the presidency, she<br />

famously insisted in interviews<br />

that she was different from Estrada<br />

because she didn’t socialize<br />

with gamblers. “Is my social life<br />

entwined with their social life?”<br />

she asked in an Asiaweek inter-<br />

view. “Do I play mahjong with<br />

them, travel with them, drink with<br />

them? I am a godmother of one<br />

of (Pineda’s) children, but that is<br />

the custom, to have the highest<br />

official in the town be a sponsor.<br />

And I even asked Cardinal Sin<br />

about the propriety of accepting<br />

being godmother of a child of<br />

somebody with a dubious reputation.<br />

Cardinal Sin told me it is my<br />

obligation to accept because the<br />

sin of the father is not the sin of<br />

the child.”<br />

Despite her religious denials,<br />

the association with Pineda<br />

persists. The most damning<br />

accusation against the president<br />

so far is that she allowed<br />

jueteng money to be used <strong>for</strong><br />

her campaign and to bribe<br />

elections officials. This was the<br />

gist of the testimony given on<br />

August 1 by political operative<br />

Michaelangelo Zuce, who said<br />

he witnessed payoffs to elections<br />

officials made in the Arroyo<br />

home by Lilia Pineda. <strong>No</strong>t only<br />

that, Zuce said that the Pinedas<br />

bankrolled other expenses of<br />

elections officials.<br />

Be<strong>for</strong>e that, Lingayen Archbishop<br />

Oscar Cruz had accused<br />

the president of receiving support<br />

“in kind” from the Lubao jueteng<br />

lord. Much earlier, when she ran<br />

<strong>for</strong> the Senate in 1995, politicians<br />

like Senator Aquilino Pimentel Jr.<br />

already accused Arroyo of having<br />

her famous <strong>No</strong>ra Aunor look-alike<br />

posters printed by Pineda. Some<br />

senatorial candidates also said<br />

that Pineda’s jueteng network<br />

were mobilized <strong>for</strong> the Arroyo<br />

campaign that year.<br />

THE PROBLEM WITH<br />

PINEDA<br />

What rouses the suspicions of<br />

jueteng watchers is that Bong<br />

Pineda has done exceedingly<br />

well during the Arroyo presidency,<br />

faring much better than he did<br />

during the Estrada era, when he<br />

had the president in his pocket,<br />

in a manner of speaking, being<br />

one of the main contributors<br />

listed in Chavit Singson’s famous<br />

ledger. Ex-cop and avid gambling<br />

watcher Sombero reckons that<br />

Pineda probably nets close to<br />

P2 billion a year from jueteng<br />

operations in 10 areas. These include<br />

his home base Pampanga,<br />

Pangasinan, Isabela, Bulacan,<br />

Bataan, Zambales, Camarines<br />

4 PHILIPPINE CENTER FOR INVESTIGATIVE JOURNALISM I REPORT

O V E R V I E W<br />

Sur, Camarines <strong>No</strong>rte, Albay, and<br />

parts of Metro Manila, a lucrative<br />

territory that Pineda reportedly<br />

shares with his <strong>for</strong>mer boss and<br />

mentor, the now aging jueteng<br />

lord Tony Santos.<br />

<strong>No</strong> one else in the history of<br />

jueteng in the country has been<br />

able to expand and consolidate<br />

illegal gambling operations as<br />

Pineda supposedly has. He is a<br />

jueteng franchisee, the Jollibee<br />

of jueteng according to Sombero,<br />

who was also vice president of<br />

the gambling firm BW Resources<br />

during the Estrada period. There<br />

are maybe half a dozen jueteng<br />

franchise operators in the country.<br />

These are the entrepreneurs<br />

and financiers who link up with<br />

a local jueteng operator, paying<br />

<strong>for</strong> the costs of protection to<br />

provincial, regional and national<br />

government and police officials,<br />

thereby allowing local gambling<br />

networks to operate free from<br />

official harassment.<br />

Sombero says local operators<br />

pay a one-time franchise fee of<br />

about P500,000 to P1 million<br />

each, and also shoulder the<br />

payoffs to the winning bettors.<br />

In a fairly large province, total<br />

bet collections would amount to<br />

about P5 million a day or P150<br />

million a month. By Sombero’s<br />

calculations, which jibe with<br />

testimonies made by several<br />

witnesses in the Senate investigation<br />

on jueteng, the national<br />

operator or franchise holder<br />

shoulders the following:<br />

• the salaries of cabos (average<br />

15 per town) and cobradores<br />

(15 per cabo) - 12<br />

percent of total collections<br />

or about P18 million monthly<br />

(in a province with 30 towns,<br />

this is about P2,500 monthly<br />

per person);<br />

• the payoffs to local officials<br />

- eight percent or about P12<br />

million monthly, including<br />

payments to the mayor,<br />

vice mayor, and sometimes<br />

councilors as well as chief<br />

of police; also includes contributions<br />

to the church and<br />

other charities as well as<br />

bribes to local media; and<br />

• the payoffs to higher-level<br />

officials and the media—10<br />

percent or about P15 million<br />

a month, including<br />

the governor (P1 million<br />

to 3 million), congressman<br />

(P1 million or less), board<br />

members, the head of the<br />

PNP regional (P1.5 million)<br />

and provincial commands<br />

(P2 million), the CIDG in the<br />

region and in the province<br />

and CIDG headquarters.<br />

The national franchise holder<br />

nets about five percent of the<br />

total collections, about P7.5 million<br />

monthly per province, and<br />

it is from these that payoffs to<br />

presidential relatives are made, if<br />

needed. But he could earn more<br />

if, like Pineda, he finances the local<br />

operations himself. The local<br />

operator, according to Sombero,<br />

gets 65 percent of the total collections,<br />

but has to pay the winners<br />

from this amount as well as<br />

personnel and other expenses,<br />

which could add up to about<br />

five percent of the collections.<br />

Local operators are dispersed; one<br />

working in just one town like Senate<br />

witness Wilfredo ‘Boy’ Mayor<br />

who operated in Daraga, Albay,<br />

would net P100,000 to P300,000<br />

a month. Someone who operates<br />

in an entire congressional district<br />

or province could net P1 million<br />

to P2 million monthly. The operators<br />

earn more if they cheat the<br />

winners and rig the bola, or the<br />

raffle where the winning numbers<br />

are picked.<br />

BULGING CASH COW<br />

In other words, jueteng is as<br />

big a cash cow as they come.<br />

And since the Estrada era, officials<br />

have wizened up to how<br />

much they can actually squeeze<br />

from gambling operators. Ten<br />

years ago, according to Mayor,<br />

the payoff to a congressman<br />

was only P25,000 a month; to a<br />

governor, just P100,000. Today<br />

Mayor says a governor would<br />

ask <strong>for</strong> at least P1 million. The<br />

amounts of bribes vary, though,<br />

and some officials do refuse to<br />

accept jueteng payoffs.<br />

But the trend throughout<br />

the country is that of ballooning<br />

payoffs. The increased demand<br />

is driven by the fact that<br />

elections—and the day-to-day<br />

doleouts that are required of<br />

patronage politics—are now<br />

more expensive. Because government<br />

finances are tight, there<br />

are fewer opportunities to make<br />

money out of public works and<br />

other contracts. The private sector,<br />

too, is feeling the pinch, and<br />

there<strong>for</strong>e not inclined to top up<br />

political contributions. At the<br />

same time, the demands <strong>for</strong> patronage<br />

are rising, as constricting<br />

economic opportunities leave<br />

more and more voters with few<br />

options left except relying on the<br />

tender mercies of politicians.<br />

For all these reasons, including<br />

the fact that politicians<br />

now have a clearer idea of how<br />

much gambling operators make,<br />

jueteng has emerged as a stable<br />

source of political funding at the<br />

local level, on top of traditional<br />

sources like Chinese-Filipino<br />

businessmen and government<br />

contractors. There is also now an<br />

evident phenomenon of jueteng<br />

operators running <strong>for</strong> local office.<br />

Apart from Pineda’s son (and<br />

the president’s godson) Dennis,<br />

who is now mayor of Lubao,<br />

there’s Armand Sanchez, who<br />

was elected Batangas governor<br />

in 2004. Liberal Party officials say<br />

that Arroyo herself interceded<br />

with the LP to adopt Sanchez a<br />

few months be<strong>for</strong>e the elections,<br />

so he could contest the governorship<br />

as a member of the party.<br />

At the national level, jueteng<br />

funds were supposedly mobilized<br />

<strong>for</strong> at least one particularly<br />

favored senatorial candidate in<br />

2004. And if the testimonies of the<br />

likes of Zuce are to be believed,<br />

jueteng funds were also used <strong>for</strong><br />

“special operations” linked to<br />

Arroyo’s 2004 presidential campaign.<br />

As a source of campaign<br />

contributions, however, jueteng<br />

lords are still dwarfed by the<br />

Chinoy tycoons, among them the<br />

likes of Lucio Tan, who supposedly<br />

gave Estrada P1.5 billion in<br />

1998. While Pineda is swimming<br />

in cash, it is unlikely he can<br />

cough up that much even <strong>for</strong> a<br />

favorite president. Capt. Marlon<br />

Mendoza, the ex-security aide<br />

of <strong>for</strong>mer election commissioner<br />

Virgilio Garcillano, alleges that<br />

DEATH BY EXPOSÉ.<br />

Arroyo beams as Estrada’s<br />

vice president at a public<br />

function be<strong>for</strong>e jueteng<br />

brought about his fall.<br />

he heard the official saying that<br />

Pineda had given P300 million to<br />

the Arroyo campaign.<br />

If these charges are true, then<br />

it is clear that the one danger of<br />

accepting that kind of money<br />

is discovery. The expansion of<br />

the Pineda jueteng empire was<br />

achieved by crushing rival operators.<br />

Apparently, these rivals<br />

were only biding their time. “He<br />

(Pineda) edged out everyone<br />

else,” Senator Panfilo Lacson told<br />

reporters in June. “He is the reason<br />

cited by many operators who<br />

have offered to be witnesses in<br />

the (Senate) investigation.”<br />

If this plot sounds familiar, it’s<br />

because we’ve heard and seen this<br />

be<strong>for</strong>e. In 2001, Chavit Singson<br />

revealed all about Erap because<br />

he felt edged out of the gambling<br />

racket. <strong>No</strong>w the small jueteng<br />

operators are ganging up against<br />

Pineda by surfacing witnesses attesting<br />

to the possible involvement<br />

of the president and her kin in the<br />

illegal numbers game.<br />

In 2001, we wrote of Estrada,<br />

“Death by exposé: this is the<br />

danger of treating presidency as<br />

a protection racket.”<br />

For sure, Estrada is suffering<br />

the consequences of his jueteng<br />

misdeeds. But everyone else, including<br />

Pineda and the two dozen<br />

or so jueteng operators who made<br />

Estrada rich, remain in business.<br />

Today is another day, another<br />

presidency. Jueteng is still going<br />

strong, and not only because it is<br />

a lifeline <strong>for</strong> politicians. It persists<br />

because of the failure of state and<br />

society to en<strong>for</strong>ce the law, deliver<br />

services, and provide <strong>for</strong> the needy.<br />

All of us are anak ng jueteng.<br />

PHILIPPINE CENTER FOR INVESTIGATIVE JOURNALISM<br />

I REPORT<br />

5

THE TWO FACES OF GMA.<br />

Aides say that while the<br />

president has a re<strong>for</strong>mist<br />

side, she has also accepted<br />

the realities of trapo politics,<br />

including paybacks and payoffs.<br />

JEKYLL-AND-HYDE<br />

CAMPAIGN<br />

YVONNE T. CHUA<br />

I<br />

N THE<br />

May 2004 elections,<br />

President Gloria Macapagal<br />

Arroyo maintained a<br />

campaign organization so<br />

elaborate it even included<br />

a group dubbed “Special<br />

Ops,” an infamous abbreviation<br />

<strong>for</strong> “special operations” that<br />

many equate with “dirty tricks,” or<br />

cruder still, poll cheating.<br />

What the “Special Ops” group<br />

under then presidential liaison<br />

officer <strong>for</strong> political affairs Jose<br />

Ma. ‘Joey’ Rufino was tasked<br />

to do—or did exactly—was not<br />

known to the president’s official<br />

campaign advisers. Up to now,<br />

many of them are still clueless<br />

about that group’s tasks.<br />

Former presidential peace<br />

adviser Teresita ‘Ging’ Deles<br />

can only say that Rufino’s activities<br />

were never taken up in<br />

the meetings of the executive<br />

council Arroyo convened to take<br />

charge of plotting and directing<br />

her campaign. Deles was part of<br />

that council, also referred to as<br />

the advisory council.<br />

“We thought we were running<br />

the campaign,” says another<br />

council member, <strong>for</strong>mer social<br />

welfare secretary Corazon ‘Dinky’<br />

Soliman. “We thought we were in<br />

the inner circle of the box.”<br />

But since the wiretapped<br />

conversations between Arroyo<br />

and Commission on Elections<br />

(Comelec) commissioner Virgilio<br />

Garcillano became public on June<br />

6, and the subsequent sworn<br />

statement issued on August 1 by<br />

Garcillano nephew and Rufino<br />

subaltern Michaelangelo ‘Louie’<br />

Zuce, Deles and Soliman now<br />

know better. Quips Soliman: “Inside<br />

the box was a smaller box.”<br />

Apparently working alongside<br />

Arroyo’s official campaign<br />

team was an in<strong>for</strong>mal network<br />

that included Garcillano, Comelec<br />

field personnel, the police<br />

and the military, freelance political<br />

operators, and perhaps<br />

a banana-chips processor and<br />

assorted businesspeople in<br />

Mindanao and elsewhere. Said<br />

to be on top of it all was First<br />

Gentleman Mike Arroyo, ably<br />

assisted by now Antipolo Rep.<br />

Ronaldo ‘Ronnie Puno, a veteran<br />

campaign strategist who was<br />

part of the Marcos, Ramos, and<br />

Estrada campaigns.<br />

These “backroom operators,”<br />

as one ex-Palace insider describes<br />

the motley team, made up<br />

several groups whose functions<br />

ranged from the seemingly mundane,<br />

such as quick-counting<br />

votes, to more questionable tasks<br />

that could have had electoral<br />

manipulation among them.<br />

These parallel operations<br />

seem to come as little surprise<br />

to those who have worked <strong>for</strong><br />

the president, given what some<br />

describe as her “dualistic” nature.<br />

A <strong>for</strong>mer aide notes that<br />

during the canvassing, Arroyo<br />

was going around the Carmelite<br />

convents, including those in Bacolod<br />

and Iloilo, even as she was<br />

then placing “improper” calls to<br />

Garcillano. “It’s like Jekyll and<br />

Hyde,” says the ex-aide.<br />

At the height of the political<br />

crisis, even her Cabinet split into<br />

two groups: one concerned with<br />

the president’s “survival at all cost,”<br />

the other pushing <strong>for</strong> “re<strong>for</strong>ms.”<br />

Soliman, a <strong>for</strong>mer Arroyo<br />

confidante, says of the president’s<br />

personality: “She was exposed<br />

and has accepted the practices of<br />

traditional politics such as paybacks,<br />

payups, operations of dirty<br />

tricks. At the same time she also<br />

believed in instituting re<strong>for</strong>ms in<br />

the economic, social and governance<br />

spheres using principles of<br />

transparency, accountability, and<br />

service to the people. She believed<br />

that both worlds can exist<br />

in one person and the dissonance<br />

and disconnect will not clash in<br />

her and in her actions.”<br />

Soliman says that in a crisis,<br />

such as now, when the two parts<br />

of the president become dissonant,<br />

Arroyo is more com<strong>for</strong>table<br />

with traditional politicians<br />

and reverts to the old world of<br />

wheeling-dealing and compromises<br />

that she knows so well.<br />

THE OFFICIAL COUNCIL<br />

When she was with her executive<br />

council during the campaign, it<br />

was the no-nonsense technocrat<br />

Gloria Arroyo that presided over<br />

the meetings. The council shared<br />

with the president the top rung<br />

of her official campaign organization.<br />

From January 2004 to the<br />

elections, the council met weekly<br />

to hear and analyze Palace pollster<br />

Pedro ‘Junie’ Laylo’s report<br />

on the province-by-province<br />

surveys he was running. It identified<br />

strategies <strong>for</strong> Arroyo in areas<br />

where her showing was weak, to<br />

turn “swing” votes among the undecided<br />

voters to her favor, and<br />

to maintain her showing in places<br />

where she was likely to win.<br />

Former President Fidel V. Ramos<br />

co-chaired the meetings with<br />

Arroyo. Aside from Ramos, council<br />

members included Deles and Soliman<br />

(both of whom represented<br />

civil society), campaign manager<br />

Gabriel Claudio, and campaign<br />

spokesman Michael Defensor. Also<br />

part of the council were the leaders<br />

of the political parties that made up<br />

the administration K-4 (Koalisyon<br />

ng Katapatan at Karanasan sa<br />

Kinabukasan) coalition: Speaker<br />

Jose de Venecia and then Defense<br />

Secretary Eduardo Ermita of the<br />

Lakas-CMD, Senate President Franklin<br />

Drilon and then Batanes Rep.<br />

Florencio Abad of the Liberal Party,<br />

Sen. Manuel Villar of the Nacionalista<br />

Party, and National Security<br />

Adviser <strong>No</strong>rberto Gonzales of the<br />

Partidong Demokratiko-Sosyalista<br />

ng Pilipinas.<br />

Businessman and <strong>Philippine</strong><br />

National Oil Company president<br />

Paul Aquino occasionally sat in<br />

the council meetings in his capacity<br />

as K-4’s consultant. Then<br />

presidential adviser <strong>for</strong> media<br />

and ecclesiastical affairs Conrado<br />

‘Dodie’ Limcaoco, who was in<br />

charge of the K-4 senatorial slate,<br />

was also in the meetings.<br />

Initially, the council met at the<br />

Palace. But when Cabinet meetings<br />

became irregular in the runup to<br />

the polls, the council would get<br />

together at the old Macapagal family<br />

residence in Forbes Park, Makati.<br />

Drilon also took over in the latter<br />

part of the campaign, says Deles.<br />

At the Cabinet, then Executive<br />

Secretary and now Foreign<br />

Secretary Alberto Romulo was in<br />

charge of how members were to<br />

6 PHILIPPINE CENTER FOR INVESTIGATIVE JOURNALISM I REPORT

T H E C A M P A I G N<br />

“CONSULTATIONS”<br />

WITH CASH<br />

Apparently more focused on<br />

their “tasks” were Garcillano and<br />

his cohorts. Indeed, Garcillano<br />

already seemed to know what he<br />

would be doing when he applied<br />

<strong>for</strong> the post of Comelec commissioner.<br />

In his <strong>No</strong>v. 11, 2003 letter<br />

to the president, Garcillano<br />

reminded Arroyo that he was<br />

among those approached by<br />

her husband when she ran and<br />

topped the 1995 senatorial polls.<br />

He also underlined his role in<br />

monitoring and protecting the<br />

votes of the Lakas senatorial candidates<br />

in 2001. Garcillano was<br />

<strong>for</strong>merly the Region 10 (<strong>No</strong>rthern<br />

Mindanao) Comelec director.<br />

Sen. Aquilino Pimentel called<br />

him a “dagdag bawas” (vote-padding<br />

and shaving) operator, but<br />

he was named elections commissioner<br />

anyway in February 2004.<br />

The burly Zuce says he was instrumental<br />

in bringing Garcillano<br />

to Rufino’s —and consequently<br />

the president’s––attention. In his<br />

sworn statement, Zuce says Garcillano,<br />

with Rufino’s blessings, in<br />

2002 organized three “consultation<br />

meetings” with Mindanaobased<br />

Comelec officials in Lanao<br />

del <strong>No</strong>rte and General Santos City<br />

during which he solicited their<br />

support <strong>for</strong> the president’s candidacy<br />

and gave out cash ranging<br />

from P5,000 to P20,000.<br />

A year later, says Zuce, Mindanao<br />

regional directors and procampaign<br />

<strong>for</strong> the president. Cabinet<br />

members, <strong>for</strong> example, were<br />

told to make a pitch <strong>for</strong> Arroyo<br />

when they distributed Philhealth<br />

cards. “We asked if we could<br />

campaign and they said we could<br />

legally because we were political<br />

appointees,” says Soliman.<br />

On election day onward,<br />

Cabinet members fanned out<br />

to the provinces to gather the<br />

provincial certificates of canvass<br />

and the accompanying statements<br />

of votes. This time they<br />

took their cues from then presidential<br />

legal counsel and now<br />

Defense Secretary Avelino Cruz,<br />

who had set up a quick-count<br />

center at the basement of the<br />

Olympia Towers in Makati.<br />

Cruz also headed a legal panel<br />

assembled <strong>for</strong> the president’s<br />

election bid. Operating out of Olympia<br />

Towers as well, the panel<br />

included <strong>for</strong>mer local governments<br />

undersecretary and now<br />

Government Corporate Counsel<br />

Agnes Devanadera, ex-Comelec<br />

Commissioner Manuel Gorospe,<br />

and election-law experts Romulo<br />

Makalintal and Al Agra.<br />

A BIG WINNING MARGIN<br />

Like any candidate, Arroyo<br />

wanted to win. That much was<br />

clear to all the president’s men<br />

and women. Actually, says<br />

an ex-Cabinet member, “she<br />

was obsessed with the idea of<br />

winning. She (couldn’t) stand<br />

a loss….(She) felt she had to<br />

redeem her father (the late president<br />

Diosdado Macapagal) who<br />

lost in his reelection (bid).”<br />

That the president should<br />

win by at least a million votes,<br />

however, was never made<br />

known to most members of her<br />

Cabinet. Yet it apparently was<br />

common knowledge among the<br />

other groups working <strong>for</strong> her.<br />

A handler of a K-4 senatorial<br />

candidate says that two weeks<br />

be<strong>for</strong>e the May 10, 2004 elections,<br />

a campaign operative had<br />

said the president would win by<br />

800,000 votes. “Plantsado na<br />

raw<br />

(It was already arranged),”<br />

the handler says. That statement<br />

would make sense to the handler<br />

only after the “Hello, Garci”<br />

tapes controversy broke out.<br />

More interestingly, however,<br />

is that other campaign insiders<br />

say First Gentleman Mike Arroyo,<br />

Kampi stalwart Ronaldo ‘Ronnie’<br />

Puno, and a top government official<br />

met regularly at the Wack Wack<br />

Country Club be<strong>for</strong>e the campaign<br />

to discuss ways to ensure not only<br />

the president’s victory, but also a<br />

huge winning margin.<br />

As campaign manager, presidential<br />

political adviser Gabriel<br />

Claudio was the K-4’s public face<br />

in last year’s elections. But those<br />

with the administration party say it<br />

was Mike Arroyo who was the de<br />

facto campaign manager, and that<br />

he got a lot of help from Puno.<br />

At the peak of the political<br />

crisis, the president herself told<br />

some Cabinet members that<br />

she had called in the Antipolo<br />

congressman to help. But during<br />

the campaign, he had no official<br />

role in the Arroyo camp. “He was<br />

never mentioned, he was never<br />

seen,” says Deles. “I would even<br />

deny his involvement in the president’s<br />

campaign. Even the First<br />

Gentleman was not visible.”<br />

Some Palace insiders, however,<br />

say Puno was working<br />

quietly behind the scenes with<br />

the First Gentleman and had recommended<br />

“unorthodox” means<br />

to clinch Arroyo’s huge winning<br />

margin over her opponent, actor<br />

Fernando Poe Jr.<br />

A campaign strategist who<br />

was part of the K-4 coalition<br />

also recalls a K-4 lawyer assuring<br />

them that they were certain to get<br />

help. “The same operations as<br />

Sulo Hotel and Byron Hotel,” the<br />

strategist was told, apparently in<br />

reference to Puno’s operations at<br />

Sulo Hotel in Quezon City when<br />

he helped Ramos’s 1992 presidential<br />

campaign and at Byron Hotel<br />

in Mandaluyong when he backed<br />

Joseph Estrada’s presidential bid.<br />

The strategist says, “DILG<br />

(the Department of Interior and<br />

Local Governments that Puno<br />

headed under the Estrada presidency)<br />

people in the provinces<br />

were used as listening posts.<br />

They even knew who drug and<br />

jueteng money were funding.”<br />

Both Claudio and Puno were<br />

with the Ramos campaign. In a<br />

2003 interview with PCIJ, Puno<br />

scoffed at allegations that he was<br />

the architect of Ramos’s supposed<br />

dirty-tricks department based at<br />

Sulo Hotel. He said he delivers<br />

because he has the science, citing<br />

his experience a campaign<br />

consultant <strong>for</strong> the U.S. lobbying<br />

firm Black, Mana<strong>for</strong>t, Stone, and<br />

Kelly, which has strong links to<br />

the Republican Party.<br />

In 2002, Puno supposedly set<br />

up camp again at Byron Hotel<br />

to build a comprehensive elections<br />

database <strong>for</strong> Arroyo. A K-4<br />

campaign strategist says Puno<br />

disbanded the group when President<br />

Arroyo announced on Rizal<br />

Day in 2002 she was not running.<br />

But he quickly got the group<br />

back together in April 2003, long<br />

be<strong>for</strong>e the president announced<br />

her candidacy. The strategy, this<br />

source says, was to use the database<br />

to pinpoint places where Arroyo<br />

was strong and employ “all<br />

means” to increase her votes.<br />

Malaya columnist and opposi-<br />

tion stalwart Lito Banayo, quoting<br />

Loren Legarda’s electoral recount<br />

consultants, says Byron Hotel was<br />

the “headquarters of choice in the<br />

2004 electoral experience of a<br />

coven of pre-fabricators of election<br />

returns” used to ensure the president’s<br />

landslide victory in Pampanga,<br />

Cebu, Iloilo, and Bohol.<br />

One member of the K-4 campaign<br />

says Puno oversaw the<br />

Mindanao canvassing after being<br />

proclaimed Antipolo City’s congressman.<br />

This source asserts that “Ronnie<br />

Puno played a big role,” although<br />

he was “distracted because he was<br />

running at the same time.”<br />

vincial election supervisors met<br />

at the Grand Boulevard Hotel on<br />

Roxas Boulevard to discuss the<br />

president’s candidacy. Envelopes<br />

containing P17,000 each were<br />

distributed to the participants.<br />

On Jan. 10, 2004, Garcillano,<br />

through Rufino’s office, organized<br />

yet another meeting with<br />

23 Mindanao election officials,<br />

again at the Grand Boulevard.<br />

This time, each Comelec official<br />

got P25,000, Zuce says.<br />

But Zuce’s most damning allegation<br />

so far is that President<br />

Arroyo hosted dinner <strong>for</strong> 27 Mindanao-based<br />

Comelec officials at her<br />

La Vista residence in Quezon City<br />

four months be<strong>for</strong>e the elections,<br />

and that envelopes containing<br />

P30,000 each were distributed by<br />

Lilia ‘Baby’ Pineda, wife of jueteng<br />

lord Rodolfo ‘Bong’ Pineda, to<br />

her guests in her presence. Zuce,<br />

who was invited to the dinner<br />

and got an envelope himself, says<br />

Garcillano and <strong>for</strong>mer Isabela Gov.<br />

Faustino Dy were also present.<br />

Zuce told the PCIJ as well as<br />

the Senate later that the president<br />

hosted another dinner that same<br />

month <strong>for</strong> about 20 Comelec officials<br />

from Luzon and the Visayas.<br />

Baby Pineda again distributed<br />

money to the officials be<strong>for</strong>e they<br />

left Arroyo’s home.<br />

Malacañang has issued no<br />

categorical denial about the dinners,<br />

although the president herself<br />

has said, “Ang masasabi ko<br />

walang nagbibigay ng suhol sa<br />

harap ko (All I can say is no one<br />

gives out bribes in front of me).”<br />

The now ailing Rufino’s own<br />

statement said, “I and my office<br />

have never been involved in influencing,<br />

much less bribing,<br />

Comelec officials to support Lakas-NUCD<br />

candidates including<br />

President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo.”<br />

Comelec officials led by<br />

Region 4 Director Juanito ‘Johnny’<br />

Icaro, who allegedly distributed<br />

the envelopes at La Vista, have<br />

PHILIPPINE CENTER FOR INVESTIGATIVE JOURNALISM<br />

I REPORT<br />

7

likewise rebutted Zuce’s charges.<br />

But Comelec regional director<br />

Helen A. Flores, who was not in<br />

any of the meetings Zuce said<br />

took place from 2002 to 2004, says<br />

Garcillano, through his security officer<br />

and nephew Capt. Valentino<br />

Lopez, had offered her P50 million<br />

to rig the 2004 polls. Flores says<br />

she spurned the offer. Four days<br />

be<strong>for</strong>e election day, she was relieved<br />

as regional director <strong>for</strong> the<br />

Autonomous Region of Muslim<br />

Mindanao and moved to Region 9<br />

(Western Mindanao). Lopez, now<br />

with the Army Headquarters Support<br />

Group, denies involvement<br />

in the bribery attempt.<br />

ZUCE’S MINDANAO<br />

TRIPS<br />

On August 10, Capt. Marlon Mendoza,<br />

a <strong>for</strong>mer Intelligence Service<br />

officer assigned as Garcillano’s<br />

chief security officer during the<br />

polls, surfaced to say he flew to<br />

Mindanao on May 11, 2004 on<br />

Garcillano’s order, and accompanied<br />

Zuce when the latter visited<br />

Lanao del <strong>No</strong>rte and Cotabato<br />

City. Mendoza told the Senate<br />

he saw Zuce handing Lanao<br />

provincial election supervisor Ray<br />

Sumalipao a “large amount of cash<br />

in an envelope” on May 12. A<br />

Comelec director in Cotabato City<br />

also received cash from Zuce on<br />

May 14, he said.<br />

Mendoza said that by May 16,<br />

he and Zuce were in Iligan City.<br />

As their group was having lunch in<br />

a restaurant there, he heard someone<br />

say, “Huling binibilang ang<br />

balota sa<br />

area ng Lanao del <strong>No</strong>rte<br />

at Lanao del Sur para makakuha<br />

ng dagdag (The ballots from Lanao<br />

del <strong>No</strong>rte and Lanao del Sur will be<br />

the last to be counted so we can<br />

increase these) if GMA will lose in<br />

other areas in the country.”<br />

In a recorded May 29 conversation<br />

with Garcillano, the president<br />

had asked pointedly, “So will<br />

I still lead by more than one million<br />

(votes)?” The commissioner<br />

replied that her rival’s count was<br />

high but “mag-compensate<br />

po<br />

sa Lanao<br />

‘yan (that will be com-<br />

pensated in Lanao).” At the time,<br />

the counting of votes from seven<br />

towns in Lanao del Sur’s 39 provinces<br />

was far from over.<br />

Zuce says his uncle sent him<br />

to Mindanao to coordinate with<br />

the Comelec personnel there. He<br />

says the region’s “special operations”<br />

headed by Ernesto ‘Butch’<br />

Paquingan, a political consultant<br />

based in Cagayan de Oro City,<br />

helped in ensuring Arroyo’s victory.<br />

Zuce says Paquingan was<br />

reporting directly to then Executive<br />

Secretary Romulo.<br />

Paquingan has called Zuce<br />

a liar. Zuce, he added, told him<br />

the opposition had offered him<br />

P4 million to P5 million to testify<br />

against Arroyo.<br />

But an old hand in electoral<br />

RIGGING THE COUNT.<br />

“Special operations” in<br />

Mindanao supposedly<br />

widened Arroyo’s lead.<br />

campaigns says Zuce worked<br />

with Paquingan in previous polls,<br />

including the 1998 elections. Many<br />

candidates <strong>for</strong> national position<br />

also engaged Paquingan’s services<br />

to help them win in Mindanao,<br />

says the campaign veteran.<br />

In his Senate testimony, Mendoza<br />

said Garcillano sent him<br />

to Cagayan de Oro on May 11,<br />

2004 as security officer <strong>for</strong> Zuce,<br />

Paquingan, “King James,” and a<br />

certain “Jun L. Bamboo” of the<br />

Presidential Management Services.<br />

He identified Paquingan as<br />

“a consultant related to DFA Secretary<br />

Romulo” and “King James”<br />

as George Goking, whom he said<br />

was Arroyo’s close friend.<br />

In the “Hello, Garci” tapes,<br />

there are two recorded conversations<br />

between the Comelec commissioner<br />

and Zuce. The first<br />

was on May 28, 2004 when Garcillano<br />

asked Zuce and Goking,<br />

a Cagayan de Oro businessman<br />

who is also a director of the <strong>Philippine</strong><br />

Amusements and Gaming<br />

Corporation (Pagcor), to come to<br />

his house <strong>for</strong> a meeting.<br />

Zuce, who confirmed to the<br />

Senate that he was among those recorded<br />

in the “Hello, Garci” tapes,<br />

called the commissioner again on<br />

June 16 to say he and “George”<br />

(apparently Goking) were at Harrison<br />

Plaza. In both conversations,<br />

Zuce addressed Garcillano as<br />

“’cle,” short <strong>for</strong> uncle.<br />

The campaign veteran says<br />

Mindanao is home to many freelance<br />

operators, including businessmen,<br />

who help candidates<br />

by buying votes <strong>for</strong> them. Zuce<br />

had been Garcillano’s conduit<br />

to some of these key players,<br />

according to the source.<br />

“(The operators) join Senate<br />

party coalitions if not hired by<br />

a senatorial candidate,” says the<br />

campaign expert. “Then they<br />

moonlight toward the finish line<br />

either buying votes or doing<br />

presidential campaigns. After<br />

the campaign, they are hired as<br />

political officers.”<br />

The campaign veteran says<br />

the operators have long been<br />

in existence; all a candidate has<br />

to do is tap into the existing<br />

syndicates and networks.<br />

“OPLAN MERCURY”<br />

Businessman Rodolfo Galang,<br />

however, says it is also important<br />

to ensure the “cooperation” of local<br />

officials and political rivals <strong>for</strong><br />

a candidate to win. Galang says<br />

he volunteered to do this <strong>for</strong> the<br />

president in parts of Mindanao<br />

during the 2004 elections.<br />

Galang, who co-owns a banana<br />

chips processing plant in<br />

Maguindanao with Paulino Ejercito,<br />

brother of ousted President<br />

Estrada, says he decided to help<br />

the Arroyo camp because he<br />

believed the country would not<br />

benefit from a Poe presidency.<br />

Galang had also been eyeing a<br />

slot machine franchise from the<br />

Pagcor. He never got it.<br />

Soon after the polls, Galang<br />

changed his mind about Arroyo<br />

and executed on June 21, 2004<br />

an affidavit he later filed with the<br />

Office of the Ombudsman. His<br />

affidavit charged the Arroyo administration<br />

with buying off local<br />

officials and opposition candidates<br />

in Romblon and certain areas in<br />

Mindanao under “Oplan Mercury.”<br />

These were Lanao del Sur, Davao<br />

City, Davao del <strong>No</strong>rte, Maguindanao,<br />

Cotabato City, Davao Oriental,<br />

South Cotabato, Davao del<br />

Sur, Sulu, <strong>No</strong>rth Cotabato, Sultan<br />

Kudarat, Tawi-Tawi, Samal, Compostela,<br />

Sarangani, Zamboanga<br />

Sibugay, and Bukidnon.<br />

Galang says his conduit to the<br />

president was Limcaoco. A March<br />

28, 2004 memorandum <strong>for</strong> Arroyo<br />

purportedly coursed through<br />

Limcaoco identified the political<br />

leaders who Galang said he could<br />

convince to pledge their support<br />

<strong>for</strong> the president, paving the way<br />

<strong>for</strong> the conversion of about a third<br />

of Poe’s projected votes to Arroyo’s.<br />

He estimated this roughly<br />

to be 1.6 million of the 5.5 million<br />

votes in the “Mercury” areas.<br />

The “conversion,” according to<br />

Galang, could be made by using<br />

the carrot of fund releases to convince<br />

local government officials to<br />

mobilize support <strong>for</strong> Arroyo. Thus,<br />

in his affidavit, Galang implicated<br />

the officials who made those fund<br />

releases possible: Nena Valdez,<br />

the president’s <strong>for</strong>mer Assumption<br />

Convent classmate who reportedly<br />

took charge of the funds released<br />

<strong>for</strong> Oplan Mercury; then Agriculture<br />

Secretary Luis Lorenzo <strong>for</strong> approving<br />

the release of the fertilizers<br />

given to Mindanao officials; then<br />

National Food Authority director<br />

Arthur Yap <strong>for</strong> the rice distributed<br />

to them; Pagcor chair Ephraim<br />

Genuino <strong>for</strong> the capital equipment<br />

that was also given out; and then<br />

Health Secretary Manuel Dayrit <strong>for</strong><br />

the medicine. (See “Running on<br />

Taxpayer’s Money.”)<br />

Be<strong>for</strong>e the March 2004 memo,<br />

Galang says he submitted to the<br />

president, again through Limcaoco,<br />

analyses of the political situation<br />

these places, including in<strong>for</strong>mal<br />

surveys assessing the chances of<br />

Arroyo and local candidates. The<br />

document on Maguindanao projected<br />

Poe would win 70 percent<br />

of the votes, or about 284,310.<br />

“Oplan Mercury” would pad the<br />

votes to ensure that Arroyo got<br />

262,2440, leaving Poe with only<br />

43,740 votes. (PCIJ has copies of<br />

the Maguindanao document and<br />

the March 2004 memo.)<br />

Right after Galang disclosed<br />

“Oplan Mercury” in a press conference<br />

last year, Limcaoco dismissed<br />

his allegations as hearsay<br />

and baseless. He said Galang had<br />

volunteered to campaign <strong>for</strong> K-4<br />

but “he was never my employee<br />

or political operator. <strong>No</strong>r did we<br />

authorize or support any illegal<br />

operation.”<br />

Former Cabinet members<br />

say it was unlikely Limcaoco<br />

had time to mount such an operation.<br />

They say taking care of<br />

the K-4 senatorial candidates<br />

was a full-time job.<br />

Still, the president did post one<br />

8 PHILIPPINE CENTER FOR INVESTIGATIVE JOURNALISM I REPORT

T H E C A M P A I G N<br />

of her biggest winning margins<br />

in the congressional count <strong>for</strong><br />

Maguindanao, garnering 193,938<br />

votes against Poe’s 59,892. The opposition<br />

considers the outcomes<br />

in eight towns there as highly<br />

dubious. Poe scored zero in Ampatuan<br />

and Datu Piang, and got<br />

as little as five to 174 votes in six<br />

other towns.<br />

In their June 6 conversation,<br />

the president sought Garcillano’s<br />

assurance that the documents in<br />

Maguindanao were consistent.<br />

The commissioner had replied<br />

that Maguindanao wasn’t really<br />

much of a problem.<br />

Four days later, Arroyo expressed<br />

concern over the local<br />

canvassing in South Upi town,<br />

where Comelec had proclaimed<br />

different winners. But she told<br />

Garcillano that the important thing<br />

was “hindi madamay ‘yung sa<br />

taas<br />

(we don’t get affected at the<br />

top).” The commissioner assured<br />

her that he had control there.<br />

A SHADOW QUICK<br />

COUNT<br />

Like the other Cabinet members<br />

gathering certificates of canvass,<br />

Deles brought the documents<br />

she had collected to presidential<br />

legal counsel Cruz, who ran the<br />

K-4’s official quick-count center<br />

at Olympia Towers. But that was<br />

not the only Arroyo quick-count<br />

in town. K-4 campaign handlers<br />

now speak of another done with<br />

the help of the <strong>Philippine</strong> National<br />

Police (PNP), then under<br />

Gen. Hermogenes Ebdane. <strong>No</strong>w<br />

public works secretary, Ebdane’s<br />

name was mentioned in the<br />

“Hello, Garci” tapes.<br />

The PNP appeared to have<br />

instructed some of its members to<br />

get copies of precinct-level election<br />

returns. These were <strong>for</strong>warded to<br />

the K-4 headquarters <strong>for</strong> senatorial<br />

candidates and their handlers to<br />

monitor. On the count’s third day,<br />

however, the Senate tally was canceled,<br />

<strong>for</strong>cing the candidates to get<br />

their own precinct count.<br />

A consultant of a K-4 senatorial<br />

candidate was told the PNP<br />

received word to send the results<br />

straight to Malacañang. The consultant<br />

was then asked to call<br />

two phone numbers to check<br />

the count’s progress: one number<br />

was a phone at the Olympia Towers;<br />

the other was picked up by<br />

someone at the Department of<br />

National Defense or DND.<br />

Soliman recalls that as election<br />

day neared, then Defense Secretary<br />

Ermita increasingly took the<br />

lead among the Cabinet members<br />

in the president’s campaign. But<br />

Deles says Arroyo had stressed the<br />

need <strong>for</strong> Ermita, a Lakas regional<br />

chairman known <strong>for</strong> his good political<br />

instincts, to stay “behind the<br />

scene.” Neither Deles nor Soliman,<br />

though, remembers any instructions<br />

given to the DND.<br />

The K-4 candidate’s consultant,<br />

however, says ex-elections<br />

commissioner Gorospe, who<br />

reportedly had his own group<br />

besides being in the K-4 legal<br />

team, was often at the DND during<br />

the counting. A <strong>for</strong>mer DND<br />

staffmember also says access to<br />

the Defense Intelligence Service<br />

Group (DISG) compound at the<br />

back of the DND building in<br />

Camp Aguinaldo was prohibited<br />

during the elections. The DISG<br />

primarily provides the security escort<br />

of the defense secretary and<br />

pursues intelligence projects.<br />

Heavily tinted vehicles were<br />

GUIDE TO NAMES IN THE CAMPAIGN CHART<br />

Silvestre Afable: then Arroyo’s communications<br />

director; chief government negotiator<br />

with the Moro Islamic Liberation Front<br />

Al Agra: elections and local governance<br />

law expert<br />

Amable Aguiluz: founder and chairman<br />

of the AMA Education System; special<br />

envoy to the Gulf Cooperation Council<br />

Tomas Alcantara: businessman, <strong>for</strong>mer trade<br />

undersecretary; now presidential chief of staff<br />

Paul Aquino: <strong>Philippine</strong> National Oil Co.<br />

president and CEO<br />

Hernani Braganza: mayor of Alaminos,<br />

Pangasinan; a Lakas stalwart<br />

Gabriel Claudio: political adviser<br />

Avelino Cruz: then presidential legal<br />

counsel, now defense secretary<br />

Angelo Tim de Rivera: commissioner,<br />

Commission on In<strong>for</strong>mation and Communications<br />

Technology<br />

Michael Defensor: then housing chief;<br />

now environment secretary<br />

Rodolfo del Rosario: Davao del <strong>No</strong>rte<br />

governor; also presidential adviser <strong>for</strong><br />

New Government <strong>Center</strong>s<br />

Agnes Devanadera: <strong>for</strong>mer local government<br />

undersecretary, now government<br />

corporate counsel<br />

Marita “Mai Mai” Jimenez: <strong>for</strong>mer presidential<br />

assistant on appointments and<br />

<strong>for</strong>mer secretary <strong>for</strong> special projects and<br />

overseas development assistance; now<br />

<strong>Philippine</strong> representative to the Asian<br />

Development Bank<br />

Pedro “Junie” Laylo: <strong>for</strong>merly with Social<br />

Weather Stations; now Palace pollster<br />

Conrado Limcaoco: then presidential adviser<br />

on media and ecclesiastical affairs;<br />

now Cabinet Offi cer <strong>for</strong> Provincial Events<br />

Edgardo “Ed” Pamintuan: presidential<br />

adviser on external affairs<br />

Abraham Purugganan: <strong>for</strong>mer deputy<br />

presidential adviser <strong>for</strong> special concerns;<br />

now <strong>Philippine</strong> National Construction Corp.<br />

director<br />

Jose Ma. “Joey” Rufino: then presidential<br />

liaison offi cer <strong>for</strong> political affairs<br />