The Face of the New American Farmer - Edible Communities

The Face of the New American Farmer - Edible Communities

The Face of the New American Farmer - Edible Communities

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

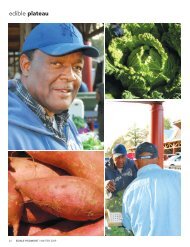

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Face</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>New</strong> <strong>American</strong> <strong>Farmer</strong><br />

BY JOHN BROENING<br />

10 EDIBLE FRONT RANGE | SPRING 2008

Photo by Brian Rabin and Junichi Arakawa<br />

What can we say about <strong>the</strong> average <strong>American</strong> farmer circa<br />

1930, <strong>the</strong> year Grant Wood painted his iconic portrait <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> gaunt figure with his pitchfork, his hard Puritan gaze<br />

and his anxious wife?<br />

He owned his own farm. He <strong>of</strong>ten worked <strong>the</strong> same occupation (and<br />

<strong>the</strong> same land) his fa<strong>the</strong>r had. He was secure in his place on <strong>the</strong> food<br />

chain—though less secure than his fa<strong>the</strong>r had been—and didn’t use<br />

words like sustainable.<br />

What about his present-day counterpart on <strong>the</strong> Front Range? Well,<br />

unless he inherited his farm, he rents his land. His numbers are<br />

shrinking every year; <strong>the</strong>y’re about a tenth <strong>of</strong> what <strong>the</strong>y were in<br />

1930. His average age, statewide, is 54. His children, more likely<br />

than not, won’t follow him into <strong>the</strong> family business. His farm has<br />

more lucrative potential as real estate than as a working farm; as<br />

CSU Agricultural Extension Agent Adrian Card says, “We lament<br />

that <strong>the</strong> last crop farms grow are houses.”<br />

If he (or, increasingly, she) is a new farmer, he <strong>of</strong>ten comes from a<br />

background somewhat related to agriculture. Josh Palmer <strong>of</strong> Grant<br />

Family Farms studied outdoor education. Josh Hadler from Verde<br />

Farms got a culinary degree from Johnson & Wales. Sue Johnson<br />

from Wolf Moon Farms was a landscape architect.<br />

Or farming can be a refuge from <strong>the</strong> corporate world. Shanan Olson<br />

from Abbondanza Farms was a self-described “corporate guru.”<br />

Wyatt Barnes from Red Wagon was driven out <strong>of</strong> his job in<br />

sportswear design by “an evil HR director straight out <strong>of</strong> Dilbert.”<br />

Unless he owns a monocrop farm, <strong>the</strong> Front Range farmer practices<br />

some form <strong>of</strong> direct marketing. She has a farm stand on her land or a<br />

stall at <strong>the</strong> farmers’ market. Or sells directly to restaurants. Or has an<br />

online store. Or uses some form <strong>of</strong> Community Supported Agriculture<br />

(CSA), a subscription service in which members pay in advance<br />

for a weekly basket <strong>of</strong> produce. Or, like, Grant Family Farms,<br />

does all <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se things in addition to selling to wholesalers and<br />

frozen food companies.<br />

CSAs have been a boon to small farms. “Everything we grow is presold,”<br />

says Bailey Stenson <strong>of</strong> three-acre Happy Heart Farm, which is<br />

100 percent CSA-driven.<br />

Rich Olson, whose Abbondanza Farms is moving more towards <strong>the</strong><br />

CSA approach, spoke <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> sheer difficulty <strong>of</strong> maintaining a farm<br />

geared towards <strong>the</strong> farmers’ market. “Market-driven farms are <strong>the</strong><br />

most difficult and labor-intensive; <strong>the</strong> hours are grueling. Five years<br />

ago, <strong>the</strong> market was our best advertisement and <strong>the</strong> best venue for<br />

educating consumers. But now…”<br />

Rich and Shanan Olson have launched one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> most ambitious<br />

CSA programs in <strong>the</strong> country: <strong>the</strong> Dream Share initiative, in which<br />

members provide a one-time, three-year financial commitment. <strong>The</strong><br />

money not only pays for seeds, fertilizer and equipment for <strong>the</strong><br />

growing season, but will allow <strong>the</strong> Olsons to achieve every farmer’s<br />

dream: to own <strong>the</strong>ir farm. As <strong>of</strong> press time, over a quarter <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

shares have been sold.<br />

Abbondanza has also been a beneficiary <strong>of</strong> Thomas Open Space, a<br />

voter-led initiative by <strong>the</strong> citizens <strong>of</strong> Lafayette to turn public land<br />

into a market farm, complete with farm stand. Abbondanza will have<br />

an irrigation system, a greenhouse and a multi-use building complete<br />

with a walk-in cooler. “It stands as a model for o<strong>the</strong>r municipalities<br />

to make an effort to create working market farms,” says Card.<br />

Most farmers speak <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> importance <strong>of</strong> educating consumers and <strong>the</strong><br />

gratification in building a sense <strong>of</strong> community. <strong>The</strong>y’ve also learned<br />

<strong>the</strong> necessity <strong>of</strong> working sustainably on a smaller scale. “We’re losing<br />

our large farms in Nor<strong>the</strong>rn Colorado, but we’re gaining more small<br />

operations,” said Karen McManus <strong>of</strong> Wolf Moon Farms. “We’re<br />

working smaller farms but we’re doing more with <strong>the</strong>m.”<br />

Says John Long, a former biochemist and renegade pig farmer who<br />

left large-scale pig farming as it became controlled by conglomerate<br />

packers and retailers, “I made a decision to produce only what I can<br />

sell directly. Basically I’m back where I started 50 years ago with one<br />

bred gilt [a young female swine]. When I sold pigs to <strong>the</strong> packers<br />

<strong>the</strong>re was a constant tug-<strong>of</strong>-war. Now, when I sell to restaurants or<br />

<strong>the</strong> people who order it, <strong>the</strong>re’s no haggling over price. I’m thrilled to<br />

death to deliver it, <strong>the</strong>y’re happy to get it, and I’m making a number<br />

<strong>of</strong> peoples’ lives pleasant and safe.”<br />

Dale Lassiter, Fulbright scholar, author and a rancher who now raises<br />

exclusively grass-fed cattle, also chose to opt out <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> factory<br />

farming system. A one-time member <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> National Cattleman’s Association<br />

(<strong>the</strong> lobbying arm <strong>of</strong> Big Cattle), he now opposes <strong>the</strong><br />

grain-intensive methods <strong>of</strong> <strong>American</strong> cattle farming.<br />

“Thirty years ago it was not as obvious [as it is now] how detrimental<br />

this whole subsidized grain-based petrochemical agriculture is to every<br />

phase <strong>of</strong> <strong>American</strong> life, from <strong>the</strong> environment to human health.”<br />

So where does this contradictory picture leave us? In Ian McEwan’s<br />

novel Saturday, one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> characters tries to make sense <strong>of</strong> it all:<br />

“<strong>The</strong> bigger you think, <strong>the</strong> crappier it looks…. So this is going to be<br />

my motto—think small.”<br />

Likewise, if we focus on <strong>the</strong> big picture—looming environmental catastrophe,<br />

an imminent water crisis in <strong>the</strong> West, disappearing<br />

farmland—it looks pretty grim. But if we focus on <strong>the</strong> small gains in<br />

<strong>the</strong> Front Range—an influx <strong>of</strong> younger organic farmers (a nationwide<br />

trend, according to a recent <strong>New</strong> York Times article), ambitious<br />

local initiatives like <strong>the</strong> Thomas Open Space, a farmers’ market<br />

in Boulder that some consider <strong>the</strong> city’s most vital institution, and<br />

more chefs and home cooks searching out local products—<strong>the</strong>re’s a<br />

lot to be optimistic about.<br />

John Broening is Executive Chef <strong>of</strong> Duo Restaurant in Denver. He<br />

has written for <strong>the</strong> Denver Post, <strong>the</strong> Baltimore Sun, <strong>the</strong> Colorado<br />

Springs Gazette, and Gastronomica.<br />

SPRING 2008 / EDIBLE FRONT RANGE 13<br />

EDIBLE FRONT RANGE | SPRING 2008 11