Lifeline to recovery - RSPB

Lifeline to recovery - RSPB

Lifeline to recovery - RSPB

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

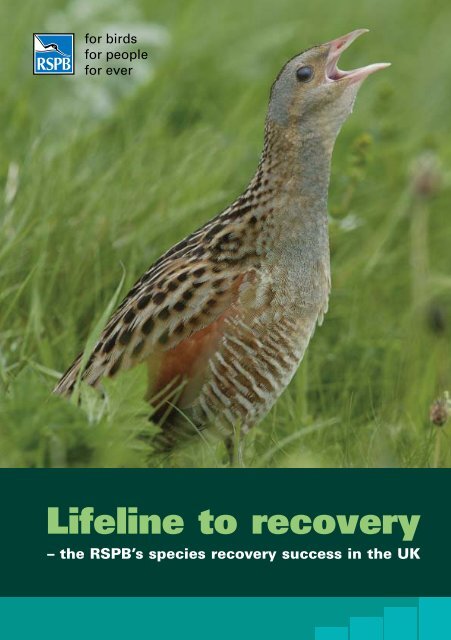

(rspb-images.com)<br />

<strong>Lifeline</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>recovery</strong><br />

– the <strong>RSPB</strong>’s species <strong>recovery</strong> success in the UK

Andy Hay (rspb-images.com)<br />

<strong>Lifeline</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>recovery</strong> – the <strong>RSPB</strong>’s<br />

species <strong>recovery</strong> success in the UK<br />

Foreword by Professor Ian New<strong>to</strong>n FRS, Chairman, The <strong>RSPB</strong><br />

David Kjaer (rspb-images.com)<br />

The <strong>RSPB</strong>’s species <strong>recovery</strong> work is a lifeline for species in trouble – such as this skylark on a lowland arable farm.<br />

Ask the average person what they<br />

associate with the <strong>RSPB</strong>, and the<br />

chances are they’ll mention ‘rare<br />

birds’ and ‘nature reserves’. And<br />

they’d be right – at least in part.<br />

Throughout its his<strong>to</strong>ry, the<br />

<strong>RSPB</strong> has had a vision of our<br />

countryside, our coasts and our<br />

seas alive with birds, and has<br />

always been ready with a lifeline<br />

for species in trouble – hence the<br />

title of this review. Early on, the<br />

focus was on protecting birds from<br />

being killed, or their eggs from<br />

being plundered. Later, the first<br />

nature reserves were established<br />

<strong>to</strong> help secure the habitat<br />

necessary <strong>to</strong> sustain populations<br />

of rare species.<br />

Protecting birds, their eggs and the<br />

places they live remains a vital part<br />

of our conservation work, but the<br />

founders of the <strong>RSPB</strong> would be<br />

amazed at the diversity and complexity<br />

of this work <strong>to</strong>day, and at the oncecommon<br />

species which are now<br />

priorities for action. We are no longer<br />

concerned only with rare birds,<br />

although work on such species<br />

remains undiminished. Priorities now<br />

include widespread birds, common<br />

for so long but now declining, such<br />

as lapwings, skylarks and even house<br />

sparrows. Indeed, house sparrows<br />

were once so abundant that the <strong>RSPB</strong><br />

was frequently asked how <strong>to</strong> keep<br />

them from dominating other species<br />

at birdtables! Nowadays, many people<br />

have noticed their decline and are<br />

anxious <strong>to</strong> see it reversed. Sound<br />

science is key <strong>to</strong> the <strong>RSPB</strong>’s<br />

successes, and it is <strong>to</strong> the <strong>RSPB</strong>’s<br />

credit that it has pioneered<br />

conservation techniques that are built<br />

on robust research and practical<br />

experience. The <strong>RSPB</strong> targets its work<br />

carefully <strong>to</strong> achieve the most from<br />

scarce resources. Recovery projects<br />

follow the same four essential steps –<br />

look at the figure on page six <strong>to</strong> see<br />

how this works. The species profiled in<br />

this review are at different stages in<br />

their <strong>recovery</strong>, and success can be<br />

measured by how much the population<br />

trend is upward, rather<br />

than downward as before.<br />

But there is one more essential<br />

ingredient in bird conservation –<br />

2<br />

<strong>Lifeline</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>recovery</strong> – the <strong>RSPB</strong>’s species <strong>recovery</strong> success in the UK

Right: Habitat res<strong>to</strong>ration is a major part of the <strong>RSPB</strong>’s work, but it takes<br />

some ‘fine-tuning’ <strong>to</strong> make it right for individual species.<br />

Below: Species <strong>recovery</strong> needs people – from research biologists<br />

<strong>to</strong> support from <strong>RSPB</strong> members and the public.<br />

Chris Gomersall (rspb-images.com)<br />

namely, people. The projects described<br />

in this booklet depended on the skills<br />

of many experts, some from within the<br />

<strong>RSPB</strong> and others from outside. Many<br />

people, including the <strong>RSPB</strong>’s one<br />

million members, want <strong>to</strong> see our<br />

countryside, seas and coasts once<br />

more alive with birds. They support<br />

the work of the <strong>RSPB</strong> magnificently;<br />

through their membership and through<br />

donations and legacies. Some also<br />

give vital support as volunteers,<br />

offering skills, enthusiasm and sheer<br />

hard work with as<strong>to</strong>nishing generosity,<br />

or through participation in large-scale<br />

science projects, helping us gain more<br />

understanding of what is happening<br />

<strong>to</strong> birds in our countryside. So<br />

celebrate, as I do, the successes<br />

described on the pages that follow.<br />

For example, in the mid-1980s, who<br />

would have thought that red kites<br />

would be re-established over much<br />

of the UK? Celebrate <strong>to</strong>o the<br />

dedicated visionaries who have<br />

made this <strong>recovery</strong> possible.<br />

The following pages will also<br />

mention the considerable challenges<br />

that lie ahead. With your support,<br />

the <strong>RSPB</strong> will strive <strong>to</strong> meet these<br />

challenges, ensuring a better<br />

environment for wildlife and<br />

people alike.<br />

Contents<br />

The need for a lifeline 4<br />

Making it happen 6<br />

Bittern 8<br />

Black grouse 10<br />

Capercaillie 12<br />

Chough 14<br />

Andy Hay (rspb-images.com)<br />

Cirl bunting 16<br />

Corncrake 18<br />

Hen harrier 20<br />

Lapwing 22<br />

Osprey 24<br />

Pine hoverfly 26<br />

Red kite 28<br />

Skylark 30<br />

S<strong>to</strong>ne-curlew 32<br />

Tree sparrow 34<br />

White-tailed eagle 36<br />

The future 38<br />

3

<strong>Lifeline</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>recovery</strong> – the <strong>RSPB</strong>’s<br />

species <strong>recovery</strong> success in the UK<br />

The need for a lifeline<br />

Andy Hay (rspb-images.com)<br />

Conserving and res<strong>to</strong>ring habitats at a landscape scale is a vital part of nature conservation.<br />

The challenge<br />

2010 is an important date for wildlife.<br />

By that year, the world is committed<br />

<strong>to</strong> reducing the rate of decline of<br />

biodiversity significantly. In the UK,<br />

and the rest of the European Union,<br />

the target is more ambitious: <strong>to</strong> halt<br />

the loss of biodiversity. Achieving<br />

these targets will be a challenge,<br />

but a start has been made.<br />

The <strong>RSPB</strong> has been at the forefront<br />

of meeting this challenge for many<br />

decades. Our ambition is not just<br />

<strong>to</strong> halt the decline, but <strong>to</strong> achieve<br />

a <strong>recovery</strong>. This review shows how<br />

we have been doing this for species<br />

that might otherwise have been lost<br />

from the UK, or that are back after<br />

many years of absence.<br />

Why species?<br />

Conserving biodiversity is about<br />

genetic variety, species, habitats and<br />

ecosystems. All are important, but<br />

it is often most appropriate, practical<br />

and effective <strong>to</strong> focus on species,<br />

be it birds, mammals, invertebrates<br />

or plants, from the most imposing<br />

preda<strong>to</strong>r <strong>to</strong> the smallest lichen. After<br />

all, these are the building blocks<br />

of biodiversity.<br />

Some species have obvious public<br />

appeal. People can identify, name,<br />

and relate <strong>to</strong> a lapwing much more<br />

easily than <strong>to</strong> coastal floodplain<br />

grazing marsh or an ecologically<br />

functioning landscape.<br />

Species often indicate the health<br />

of our environment and can be the<br />

easiest and most appropriate level<br />

of biodiversity <strong>to</strong> moni<strong>to</strong>r. In addition,<br />

interest in species, such as the bittern,<br />

can provide support, profile and<br />

impetus for habitat conservation.<br />

Having a specific focus often makes<br />

conservation sense.<br />

Over the years we have lost many<br />

native species from the UK, and the<br />

rate of loss has increased in the last<br />

200 years. Some, such as the wolf,<br />

beaver and osprey are well known,<br />

but the demise of many others will<br />

4<br />

<strong>Lifeline</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>recovery</strong> – the <strong>RSPB</strong>’s species <strong>recovery</strong> success in the UK

Recovery work for one species often<br />

benefits others. Habitat management<br />

for corncrakes on the Western Isles of<br />

Scotland also helps the great yellow<br />

bumblebee, a UK BAP priority<br />

species.<br />

Mike Edwards (rspb-images.com)<br />

have gone unrecorded. With modern<br />

conservation awareness, there is a<br />

welcome and popular commitment<br />

<strong>to</strong> maintaining the diversity of<br />

species in the UK. Nevertheless, over<br />

the last 50 years we have witnessed<br />

the severe decline of far <strong>to</strong>o many<br />

once widespread, common and<br />

familiar species.<br />

Conservation is not just about<br />

avoiding extinctions but about res<strong>to</strong>ring<br />

or recovering species populations<br />

<strong>to</strong> secure sustainable levels, and<br />

preventing other species from<br />

reaching such a perilous situation<br />

in the first place.<br />

Species, by their very nature, have<br />

specific ecological requirements. They<br />

may appear <strong>to</strong> share the same habitat<br />

with many others but they each have<br />

a different, specific niche. It is what<br />

sets them apart, and makes them<br />

what they are.<br />

Conserving and res<strong>to</strong>ring habitats<br />

at a landscape scale is a vital part<br />

of nature conservation, especially<br />

<strong>to</strong> make biodiversity robust <strong>to</strong><br />

environmental change. However,<br />

<strong>to</strong> really deliver conservation benefit,<br />

habitats must meet the needs of<br />

the species that depend on them.<br />

Res<strong>to</strong>ring reedbeds alone would not<br />

have enabled the bittern population<br />

<strong>to</strong> recover. The water levels in the<br />

reedbeds have <strong>to</strong> be right, with<br />

thriving fish populations, management<br />

informed by dedicated research.<br />

Habitat loss has his<strong>to</strong>rically been<br />

a key fac<strong>to</strong>r in the decline of many<br />

species in the UK. However, the<br />

way existing habitats are managed<br />

is also important. Many of the<br />

meadows and grasslands that used<br />

<strong>to</strong> echo the rasping call of the<br />

corncrake remain throughout the UK.<br />

But fairly simple changes, such as<br />

cutting the grass earlier in the summer,<br />

has resulted in the corncrake’s<br />

disappearance from what otherwise<br />

appears <strong>to</strong> be suitable habitat.<br />

Generalised habitat management, that<br />

does not take account of the needs of<br />

key species, can be very damaging.<br />

In some cases, even res<strong>to</strong>ring habitat<br />

and managing it in the right way is not<br />

enough <strong>to</strong> return species <strong>to</strong> areas from<br />

which they have been lost. Some may<br />

not readily re-colonise favourable<br />

habitat or will only do so by chance.<br />

In these circumstances, it may be<br />

appropriate <strong>to</strong> re-introduce a species<br />

<strong>to</strong> its former range. This is not a<br />

measure <strong>to</strong> undertake lightly: projects<br />

are invariably long-term, expensive<br />

and complex. Nevertheless, in the<br />

right circumstances, reintroduction<br />

can be an important part of the<br />

conservation <strong>to</strong>olkit.<br />

Setting targets<br />

Having identified the priorities, a<br />

conservation programme is most<br />

effective when working <strong>to</strong> clear,<br />

quantifiable targets against which<br />

progress can be measured. It may<br />

be a pragmatic miles<strong>to</strong>ne or an<br />

end-point at which the status of<br />

the species is favourable. It may<br />

be a minimum figure, a bot<strong>to</strong>m line<br />

below which things really cannot be<br />

allowed <strong>to</strong> slip, or a goal <strong>to</strong> res<strong>to</strong>re<br />

or enhance its population or range.<br />

It must be achievable, yet ambitious,<br />

something <strong>to</strong> aspire <strong>to</strong>. Most<br />

importantly it must provide a focus on<br />

real biological outcomes, or <strong>to</strong> put it<br />

somewhat informally, ‘bums on nests’.<br />

The <strong>RSPB</strong> sets biological targets<br />

for all its priority species and habitats,<br />

often framed as a contribution <strong>to</strong>wards<br />

a broader objective set in the UK<br />

Biodiversity Action Plan (UK BAP)<br />

or agreed with statu<strong>to</strong>ry conservation<br />

bodies.<br />

Using the right <strong>to</strong>olkit<br />

Nature surprises and inspires us<br />

precisely because each species is<br />

different, so when we need <strong>to</strong> secure<br />

its <strong>recovery</strong>, we have <strong>to</strong> use the right<br />

<strong>to</strong>ols. For localised species or those<br />

where the population is small, it<br />

is possible <strong>to</strong> use hands-on<br />

management – literally, for example,<br />

in the case of s<strong>to</strong>ne-curlews.<br />

(see page 32).<br />

Where we are influencing a large<br />

proportion of a small population<br />

directly, dedicated projects are very<br />

effective. Some of the work reported<br />

here has almost certainly prevented<br />

extinction from the UK, though<br />

the need for this last-chance<br />

conservation effort is a symp<strong>to</strong>m<br />

of land management that has failed<br />

for wildlife.<br />

For more widespread species,<br />

such as the skylark, it is not feasible<br />

<strong>to</strong> manage specifically for every pair<br />

in the country. Here, we must<br />

develop <strong>recovery</strong> measures that can<br />

be incorporated in<strong>to</strong> land-use policies,<br />

illustrated by the adoption of skylark<br />

plots in<strong>to</strong> the Environmental<br />

Stewardship Scheme for farmers<br />

in England.<br />

We hope that in the pages that follow,<br />

we will show how we translate careful<br />

planning in<strong>to</strong> real action on the ground.<br />

5

<strong>Lifeline</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>recovery</strong> – the <strong>RSPB</strong>’s<br />

species <strong>recovery</strong> success in the UK<br />

Making it happen<br />

This <strong>recovery</strong> curve illustrates broadly the sequence of activity that can take a declining species<br />

<strong>to</strong> <strong>recovery</strong>.<br />

Sustainable<br />

management<br />

Recovery<br />

management<br />

Population<br />

Trial management<br />

Research<br />

Time<br />

Research<br />

Trial<br />

management<br />

Recovery<br />

management<br />

Sustainable<br />

management<br />

Understanding a species’<br />

requirements and the<br />

specific threats that it faces<br />

are key. It is important that<br />

conservation efforts are<br />

based on sound knowledge,<br />

so detailed ecological<br />

research is often the first<br />

step <strong>to</strong>wards species<br />

<strong>recovery</strong>.<br />

The <strong>RSPB</strong> turns this<br />

knowledge in<strong>to</strong> a<br />

programme of conservation<br />

action, which may involve<br />

testing out management<br />

prescriptions or conducting<br />

feasibility studies for<br />

re-introduction projects.<br />

<strong>RSPB</strong> nature reserves<br />

are often used <strong>to</strong> trial<br />

management under<br />

controlled conditions.<br />

Once conservation<br />

measures have been tested<br />

and shown <strong>to</strong> work, they<br />

can be implemented as part<br />

of a <strong>recovery</strong> programme<br />

in the wider countryside,<br />

working in partnership<br />

with other conservation<br />

organisations, farmers,<br />

foresters and industry, and<br />

with government policies<br />

<strong>to</strong> ensure that public<br />

funding benefits, or at least<br />

does not threaten, wildlife.<br />

Ultimately, this is where<br />

we want <strong>to</strong> be. If all species<br />

were here, there would<br />

be no need for a species<br />

<strong>recovery</strong> programme.<br />

It is vital <strong>to</strong> moni<strong>to</strong>r the<br />

progress of <strong>recovery</strong> work<br />

so that adjustments can<br />

be made, and effort can be<br />

increased or curtailed<br />

once targets are met.<br />

6 <strong>Lifeline</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>recovery</strong> – the <strong>RSPB</strong>’s species <strong>recovery</strong> success in the UK

Right: work <strong>to</strong> reverse the alarming<br />

declines in the numbers of lapwings<br />

on wet grassland is in the early<br />

stages, but on <strong>RSPB</strong> reserves we<br />

have maintained their numbers.<br />

Below: the return of the osprey <strong>to</strong><br />

the UK is an inspiration. In much of<br />

Scotland, this bird is now in the<br />

sustainable management phase after<br />

50 years of dedicated effort by the<br />

<strong>RSPB</strong> and others.<br />

Mark Hamblin (rspb-images.com)<br />

Making it happen<br />

At any particular time,<br />

a species may be at<br />

a different stage of the<br />

<strong>recovery</strong> curve according<br />

<strong>to</strong> local conditions.<br />

There is rarely a single<br />

solution, and <strong>recovery</strong> <strong>to</strong><br />

the levels of sustainable<br />

management can take<br />

several decades.<br />

Once the population has recovered<br />

sufficiently, intensive <strong>recovery</strong> work<br />

can be replaced by management<br />

aimed at sustaining an enhanced<br />

population. This might be incorporated<br />

in<strong>to</strong> dedicated conservation work (for<br />

localised species that live in specialised<br />

habitats, such as reedbeds or lowland<br />

heath) or in<strong>to</strong> land-use practices for<br />

more widespread species.<br />

This means that <strong>recovery</strong> has <strong>to</strong> be<br />

about more than just the biological<br />

needs of the species. It has <strong>to</strong> identify<br />

the sustainable economic and social<br />

context for biodiversity conservation.<br />

For example, recovering the population<br />

of corncrakes in the Scottish islands<br />

would not be possible without<br />

integrating management for this<br />

species in<strong>to</strong> support for crofting<br />

agriculture. This brings other benefits<br />

for those who work the land and<br />

visit the islands, and the many other<br />

species that depend on the rich<br />

machair habitats. As such, species<br />

<strong>recovery</strong> work can be an important<br />

contribution <strong>to</strong> sustainable<br />

development.<br />

Celebrate success<br />

Focusing action on the right species,<br />

setting clear biological objectives<br />

and using the right <strong>to</strong>ols means that,<br />

when delivered well, species <strong>recovery</strong><br />

work has successes that are worth<br />

celebrating. We hope that you’ll<br />

celebrate with us, and if you helped<br />

<strong>to</strong> make some of these s<strong>to</strong>ries<br />

a reality, we thank you.<br />

Chris Gomersall (rspb-images.com)<br />

7

Bittern<br />

In 2004, the UK bittern population reached the miles<strong>to</strong>ne<br />

of 50 booming males that was set in the UK Biodiversity<br />

Action Plan.<br />

Species status<br />

Phase of <strong>recovery</strong>:<br />

Recovery<br />

Red list Bird of Conservation Concern<br />

UK BAP lead partner – the <strong>RSPB</strong><br />

Andy Hay (rspb-images.com)<br />

Bittern numbers crashed during the late 20th century, but although still vulnerable, bitterns are on the way <strong>to</strong> <strong>recovery</strong>.<br />

Bitterns are large birds that live<br />

in reedbeds and are more often<br />

heard than seen. When we count<br />

the number of bitterns in an area,<br />

we do this by noting the number<br />

of birds that boom (the call the<br />

male birds use <strong>to</strong> attract a mate).<br />

This amazing booming sound can<br />

be heard from up <strong>to</strong> 5 km away<br />

and each male’s boom is slightly<br />

different, so we can identify each<br />

male individually.<br />

Drastic decline in<br />

bittern numbers<br />

Once common in wetlands, bitterns<br />

became extinct as breeding birds in<br />

the UK in the late 19th century, as<br />

a result of wetland drainage and<br />

hunting. These birds were next<br />

recorded as breeding in Norfolk in 1911.<br />

They slowly recolonised from there<br />

and by 1954 there were around 80<br />

booming males. However, numbers<br />

dropped again as their reedbed<br />

habitats became drier through lack<br />

of management. By 1997 only 11<br />

booming bitterns were recorded in<br />

the UK and there was a similar pattern<br />

of decline in bitterns across western<br />

Europe.<br />

Back from the brink<br />

Alarmed by the plunging bittern<br />

numbers, the <strong>RSPB</strong> started a research<br />

programme <strong>to</strong> investigate the needs<br />

of this previously little-studied bird.<br />

This led <strong>to</strong> some clear management<br />

recommendations that have been,<br />

and still are being, implemented<br />

at many sites in the UK.<br />

Bitterns are difficult <strong>to</strong> study as<br />

they are found at low densities in<br />

habitats that are difficult <strong>to</strong> work in.<br />

The research looked at the habitat<br />

that bitterns prefer, their feeding<br />

requirements, the home range of male<br />

bitterns, as well as female nesting<br />

requirements, chick diet and their<br />

dispersal. To find this information,<br />

lightweight radio-transmitters were<br />

attached <strong>to</strong> bitterns at two <strong>RSPB</strong><br />

reserves so that their movements<br />

could be tracked. Later, young birds<br />

at the nest were also radio-tagged<br />

and their food preferences studied.<br />

8<br />

<strong>Lifeline</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>recovery</strong> – the <strong>RSPB</strong>’s species <strong>recovery</strong> success in the UK

Right: The EU-Life fund has enabled<br />

the creation and res<strong>to</strong>ration of reedbeds<br />

– the future challenge is <strong>to</strong> manage these<br />

in a cost-effective and ecologically<br />

sustainable manner.<br />

Below: <strong>RSPB</strong> research found that bitterns<br />

need early successional wet reedbeds<br />

with extensive pool and ditch systems<br />

<strong>to</strong> provide feeding opportunities where<br />

the reedbed and water meet.<br />

Andy Hay (rspb-images.com)<br />

Continuing the improvement<br />

The research results meant that<br />

we unders<strong>to</strong>od what bitterns needed<br />

so we could manage the habitat<br />

appropriately for them. Much of the<br />

work <strong>to</strong> make habitats more suitable<br />

has been carried out through two<br />

large <strong>RSPB</strong>-led projects funded by<br />

the EU-Life programme.<br />

The first project, centred on East<br />

Anglia, was a partnership of seven<br />

organisations and ran from 1996–<br />

2000 at thirteen sites. The project<br />

concentrated on res<strong>to</strong>ring reedbeds<br />

by raising the water levels, controlling<br />

the growth of bushes, and excavating<br />

and reshaping pools and ditches in the<br />

reedbeds. By 2004, bittern numbers<br />

had increased at 10 of the 13 project<br />

sites. At the <strong>RSPB</strong>’s Minsmere nature<br />

reserve, two booming bitterns in 1997<br />

had increased <strong>to</strong> nine by 2004.<br />

The second bittern project, from<br />

2002–2006, is developing a wider<br />

network of reedbeds suitable for<br />

breeding or wintering bitterns. Eight<br />

organisations are involved at 19 sites.<br />

Much of the work involves creating<br />

700 hectares of new reedbeds.<br />

Improvements are also being made<br />

<strong>to</strong> encourage more fish for the birds<br />

<strong>to</strong> eat, which will increase the bitterns’<br />

breeding success.<br />

By 2004, the UK bittern population<br />

had risen <strong>to</strong> a minimum of 55 booming<br />

male birds. This was achieved because<br />

detailed <strong>RSPB</strong> research was rapidly<br />

put in<strong>to</strong> practice, the conservation<br />

organisations managing reedbeds<br />

developed strong partnerships and<br />

because a high percentage of<br />

reedbeds in the UK are managed<br />

by conservation organisations.<br />

The way ahead<br />

Management work <strong>to</strong> date has<br />

s<strong>to</strong>pped reedbed degradation and<br />

the projects underway should provide<br />

significant areas of high-quality<br />

reedbed in the future, although it will<br />

take many years for these new sites <strong>to</strong><br />

mature. The knowledge that the <strong>RSPB</strong><br />

has gained about bitterns’ needs, as<br />

well as how <strong>to</strong> manage and create<br />

reedbeds, is being shared among<br />

those managing reedbeds. Overall,<br />

the prospects for UK bitterns appear<br />

<strong>to</strong> be good, though the population is<br />

at risk from climate change. As sea<br />

levels rise, saltwater could flow in<strong>to</strong><br />

coastal reedbeds, making the habitat<br />

unsuitable for bitterns. As a result,<br />

several new reedbeds are being<br />

created inland, away from vulnerable<br />

coasts, such as Lakenheath Fen in<br />

Suffolk and the Hanson–<strong>RSPB</strong> Wetland<br />

Project in Cambridgeshire, where 500<br />

hectares of reedbed are planned.<br />

Andy Hay (rspb-images.com)<br />

Two major habitat projects have resulted in more bitterns,<br />

and in more places<br />

Number of males/sites<br />

60<br />

50<br />

40<br />

30<br />

20<br />

10<br />

2010 UK BAP target<br />

0<br />

1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004<br />

Booming males<br />

Occupied sites<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

The research was undertaken as part of Action for Birds in England, a conservation partnership<br />

between English Nature and the <strong>RSPB</strong>. Key work was undertaken by partners within the two<br />

bittern projects funded by the EU-LIFE programme. These include English Nature, The Broads<br />

Authority, The Wildlife Trusts, The Environment Agency, The National Trust and The Lee Valley<br />

Regional Park Authority.<br />

9

Black grouse<br />

Black grouse are declining in most European<br />

countries. Having reversed the decline in England<br />

and Wales, the challenge is <strong>to</strong> sustain the <strong>recovery</strong><br />

and <strong>to</strong> trial similar management in Scotland.<br />

Species status<br />

Phase of <strong>recovery</strong>:<br />

Research/Trial<br />

Red list Bird of conservation concern<br />

UK BAP lead partner – the <strong>RSPB</strong>/Game<br />

Conservancy Trust<br />

Mark Hamblin (rspb-images.com)<br />

This splendid male grouse is at a lek, a flamboyant display taking place on an area of flat, open ground where the males gather<br />

<strong>to</strong> compete for the attention of the hens. The dominant male is likely <strong>to</strong> mate with most of the visiting hens.<br />

Black grouse were formerly<br />

widespread but have been<br />

declining since the early 1900s.<br />

The decline has accelerated since<br />

newly-planted forestry matured<br />

in the 1980s. This bird has<br />

become locally extinct in many<br />

regions. Black grouse are<br />

moni<strong>to</strong>red by counting the<br />

number of males at leks, where<br />

birds gather <strong>to</strong> display <strong>to</strong> females<br />

in spring. A survey in 1995/96<br />

found only 6,500 lekking males –<br />

most of them in Scotland, with<br />

smaller numbers in England<br />

and Wales.<br />

A range of problems<br />

Black grouse need a mosaic of<br />

habitats. Over the last 50 years<br />

there have been considerable changes<br />

in the landscape of the UK. Farming<br />

has intensified and large-scale forestry<br />

plantations have matured, and this<br />

gives a uniform habitat rather than the<br />

patchwork that black grouse need.<br />

As black grouse numbers have fallen,<br />

other fac<strong>to</strong>rs have become more<br />

important, which larger populations<br />

should be able <strong>to</strong> withstand. Birds are<br />

killed by preda<strong>to</strong>rs, by crashing in<strong>to</strong><br />

deer fences and as a result of bad<br />

weather. Isolated populations have<br />

disappeared al<strong>to</strong>gether. Some fac<strong>to</strong>rs<br />

have affected black grouse on a<br />

regional basis, while others have<br />

operated on a UK-wide scale. Some<br />

are less of a threat than they were.<br />

Often a combination of fac<strong>to</strong>rs drives<br />

the populations <strong>to</strong> low levels, when<br />

a chance occurrence can kill a small<br />

number of birds and so cause a local<br />

extinction.<br />

Black grouse projects<br />

Several <strong>recovery</strong> projects have<br />

been set up, using the best available<br />

research, <strong>to</strong> focus on the needs of<br />

the black grouse on a regional basis.<br />

Project officers, usually supported by<br />

a partnership of government and<br />

voluntary organisations, work with<br />

farmers, foresters, estate managers<br />

and gamekeepers <strong>to</strong> safeguard and<br />

create vital habitat, often funded by<br />

government grants. Working with<br />

local people, project officers also<br />

moni<strong>to</strong>r the fortunes of black grouse,<br />

<strong>to</strong> see how they respond <strong>to</strong> the<br />

10<br />

<strong>Lifeline</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>recovery</strong> – the <strong>RSPB</strong>’s species <strong>recovery</strong> success in the UK

Until recently, this moorland and<br />

blanket bog was afforested, holding<br />

little value for black grouse or other<br />

wildlife. Pioneering work by the <strong>RSPB</strong><br />

and Forestry Commission Wales has<br />

opened out the habitat, and black<br />

grouse have recolonised this site<br />

at Penaran Forest.<br />

Andy Hay (rspb-images.com)<br />

changes in management.<br />

These regional projects are testing<br />

the mix of management measures,<br />

both <strong>to</strong> secure regional populations<br />

and <strong>to</strong> inform future land management<br />

policies. There are currently four<br />

partnership <strong>recovery</strong> projects: two<br />

in Scotland, one in Wales and one<br />

in England. As well as advice and<br />

assistance in finding grants, project<br />

officers also organise training events<br />

for land managers and advisers who<br />

want <strong>to</strong> help black grouse.<br />

■ The Welsh Black Grouse<br />

Recovery Project is focusing on<br />

key areas in mid and north Wales<br />

that hold the largest remaining<br />

populations. Work <strong>to</strong> res<strong>to</strong>re the<br />

diversity of moor edge, rough<br />

grazing and woodland has seen<br />

an 85% increase in the number of<br />

lekking males between 1997 and<br />

2002. Much of this has been thanks<br />

<strong>to</strong> major restructuring of forestry<br />

plantations. Where management<br />

work has not been carried out,<br />

the numbers of black grouse have<br />

continued <strong>to</strong> fall.<br />

■ The North Pennines Black<br />

Grouse Recovery Project<br />

encourages farmers and landowners<br />

<strong>to</strong> improve the conditions for black<br />

grouse on their land. This includes<br />

reducing grazing on the moor edges<br />

and adjacent rough pastures, the<br />

re-establishment of traditional hay<br />

meadow management, planting of<br />

small-scale upland ghyll woodlands<br />

and control of foxes, crows and<br />

s<strong>to</strong>ats. There has been an increase<br />

in the number of displaying males<br />

by 5% each year where grazing by<br />

sheep has been reduced through<br />

agri-environment schemes. This<br />

compares with a decline of 2%<br />

each year where grazing was<br />

not restricted.<br />

■ The Dumfries and Galloway<br />

Black Grouse Recovery<br />

Project is working <strong>to</strong> stem the<br />

decline of black grouse in this area.<br />

In recent decades, there has been<br />

a huge reduction in numbers, due<br />

<strong>to</strong> overgrazing, the lack of moorland<br />

management, and the maturation<br />

of conifer plantations. With<br />

plantation forestry accounting for<br />

over one quarter of Dumfries and<br />

Galloway – the highest density<br />

anywhere in the UK – a crucial<br />

aspect of the project is incorporating<br />

the needs of black grouse in<strong>to</strong><br />

Forest Design Plans. Through<br />

these, we have the best chance of<br />

securing the future of black grouse<br />

during future forestry changes.<br />

■ The Argyll and Bute Black<br />

Grouse Recovery Project<br />

has identified a core area of<br />

suitable habitat around important<br />

lek sites, which is being targeted<br />

for conservation action.<br />

Annual % population change<br />

30<br />

20<br />

10<br />

0<br />

-10<br />

1986-1997 1997-2002<br />

Areas where management started in winter 1997<br />

Sustaining <strong>recovery</strong><br />

On our reserves, we are trialling<br />

management <strong>to</strong> increase numbers of<br />

black grouse. At Corrimony, Highland,<br />

we have increased numbers from 16<br />

lekking males in 1997 and maintained<br />

these at over 35 since 2001.<br />

The four <strong>recovery</strong> projects show what<br />

can be done for black grouse. Learning<br />

from these projects, the partners hope<br />

<strong>to</strong> build the needs of black grouse<br />

in<strong>to</strong> farming, moorland and forestry<br />

management policies and practices.<br />

A survey of UK black grouse in 2005<br />

will tell us how much the population<br />

has changed over the last 10 years.<br />

We will continue <strong>to</strong> work for the<br />

<strong>recovery</strong> of this species and hope<br />

that land management for black grouse<br />

will help numbers <strong>to</strong> increase over<br />

a wider area.<br />

The change in numbers of lekking males on managed areas in Wales<br />

shows how they can respond <strong>to</strong> suitable habitat management<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

No management<br />

Welsh Recovery Project: This Project was funded by the European Union (European Agriculture Guidance and<br />

Guarantee Fund), the National Assembly for Wales (Rural Development Grant), the <strong>RSPB</strong>, Countryside Council for Wales<br />

and Forest Enterprise Cymru.<br />

North Pennines <strong>recovery</strong> project: a partnership between English Nature, the Game Conservancy Trust, Ministry<br />

of Defence, the <strong>RSPB</strong> and Northumbrian Water.<br />

Dumfries and Galloway <strong>recovery</strong> project: a partnership between the <strong>RSPB</strong> and Scottish Natural Heritage, assisted<br />

by Forestry Commission Scotland<br />

Argyll and Bute <strong>recovery</strong> project: a partnership of Forestry Commission Scotland, Scottish Power,<br />

the <strong>RSPB</strong>, Scottish Natural Heritage, supported by an award from the Esmée Fairbairn Foundation.<br />

11

Capercaillie<br />

Capercaillie populations have shown hopeful signs of starting<br />

<strong>to</strong> recover. However, they are very vulnerable and could still be<br />

lost from the UK in the next couple of decades. Management is<br />

helping <strong>to</strong> ensure that we don’t lose this magnificent bird again.<br />

Species status<br />

Phase of <strong>recovery</strong>:<br />

Recovery<br />

Red list Bird of Conservation Concern<br />

UK BAP lead partner – the <strong>RSPB</strong>/the<br />

Centre for Ecology and Hydrology<br />

Chris Gomersall (rspb-images.com)<br />

The capercaillie is the largest grouse in the world. In the UK it is now only found in Scotland, where it is associated with<br />

semi-natural Scots pine woods, though capercaillie also live in commercial conifer forests.<br />

Most of the capercaillie<br />

remaining in Scotland are found<br />

in Strathspey – with a significant<br />

proportion of the population<br />

on <strong>RSPB</strong> nature reserves.<br />

The rise and fall of<br />

the capercaillie<br />

It is believed that capercaillie<br />

became extinct in England in the<br />

17th century and the last known<br />

record of a native capercaillie in<br />

Scotland was in 1785. The birds<br />

disappeared because of extensive<br />

felling of forests.<br />

In the 19th century more forests<br />

were planted and capercaillie were<br />

successfully reintroduced from<br />

1837 onwards. They quickly recolonised<br />

the pinewoods of northern Scotland<br />

and their numbers grew <strong>to</strong> a peak in<br />

the early 1900s.<br />

The demand for wood during the<br />

two World Wars meant that much<br />

suitable capercaillie habitat was<br />

destroyed. Consequently, the number<br />

of birds fell and, although there was<br />

some increase in numbers in the<br />

1960s, by 1999 only 1,000 birds<br />

remained.<br />

What was the problem?<br />

The decline in capercaillie numbers<br />

over the last 30 years has resulted<br />

from poor breeding. The lack of food<br />

at crucial times in the breeding cycle,<br />

as a result of climate-induced changes,<br />

may be a fac<strong>to</strong>r in these failures.<br />

However, the effects of this have<br />

been compounded by:<br />

■ limited food for young capercaillie<br />

because of grazing of shrubs such<br />

as blaeberry by deer<br />

■ capercaillie dying as a result<br />

of flying in<strong>to</strong> forest fences<br />

■ foxes and crows, which eat<br />

capercaillie and their eggs<br />

■ disturbance by people and some<br />

unsympathetic forest management.<br />

Scotland is not the only place <strong>to</strong><br />

experience such declines. Capercaillie<br />

populations have also been falling in<br />

countries in central Europe, such as<br />

12<br />

<strong>Lifeline</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>recovery</strong> – the <strong>RSPB</strong>’s species <strong>recovery</strong> success in the UK

To s<strong>to</strong>p capercaillie from flying in<strong>to</strong><br />

fences and dying like this one, the<br />

<strong>RSPB</strong> worked with Forestry<br />

Commission Scotland <strong>to</strong> review<br />

their fencing policy, and the Scottish<br />

Executive funded the marking or<br />

removal of hundreds of kilometres<br />

of threatening deer fences in<br />

capercaillie woods.<br />

Chris Gomersall (rspb-images.com)<br />

Switzerland. Large populations still<br />

exist in Scandinavia and northern<br />

Russia, but even these are declining.<br />

Identifying the problem<br />

Capercaillie have been studied by the<br />

<strong>RSPB</strong> and the Centre for Ecology and<br />

Hydrology (CEH) <strong>to</strong> moni<strong>to</strong>r breeding<br />

success and survival in forests across<br />

the range. This quickly identified<br />

problems with breeding and collisions<br />

with deer fences.<br />

The studies found that capercaillie<br />

chicks need a diet rich in invertebrates,<br />

such as caterpillars, and that blaeberry<br />

was the best habitat for chicks. This<br />

habitat was scarce in many forests<br />

because of heavy grazing by deer.<br />

Fences, put up <strong>to</strong> keep deer out of<br />

pine woods and forestry plantations,<br />

proved <strong>to</strong> be a significant problem,<br />

with many birds flying in<strong>to</strong> them and<br />

dying. Predation by crows also limited<br />

breeding success at the <strong>RSPB</strong>’s<br />

Abernethy reserve.<br />

Partnership approach<br />

proves effective<br />

The <strong>RSPB</strong> bought the Forest Lodge<br />

Estate at Abernethy in 1988 and since<br />

then has been heavily involved in<br />

conserving capercaillie. Work was<br />

undertaken <strong>to</strong> res<strong>to</strong>re the habitat,<br />

crows and foxes were controlled and<br />

fences were removed or marked<br />

<strong>to</strong> make them more visible <strong>to</strong> the<br />

birds. The number of capercaillie<br />

subsequently increased <strong>to</strong> 100 birds.<br />

Work in one single forest would not<br />

help the capercaillie as there are no<br />

Scottish forests big enough <strong>to</strong> support<br />

a viable population of the birds on<br />

their own. However, the <strong>RSPB</strong>’s<br />

Abernethy reserve has proved a<br />

valuable example for conservation<br />

work throughout Scotland.<br />

Conservation work on a large scale<br />

is now being carried out at all the key<br />

sites for capercaillie in Scotland, based<br />

on what has been learnt at Abernethy<br />

and on research work carried out by<br />

the CEH and the <strong>RSPB</strong>. This work<br />

accords with the forests being used<br />

commercially and for recreation.<br />

Conservation work for the capercaillie<br />

has benefited from EU funding. More<br />

than £215 million is directly supporting<br />

jobs in forestry throughout rural<br />

Scotland. The capercaillie is probably<br />

not the only species <strong>to</strong> benefit, as<br />

managing the woodlands for them,<br />

particularly thinning, should increase<br />

the diversity of other vertebrates, such<br />

as small mammals, and invertebrates<br />

<strong>to</strong>o, from wood ants <strong>to</strong> pinewood<br />

beetles.<br />

Number of birds<br />

25,000<br />

20,000<br />

15,000<br />

10,000<br />

5,000<br />

0<br />

20,000<br />

BAP target 5000 birds by 2010<br />

2200<br />

1970 1994<br />

The future for capercaillie<br />

More than 50,000 hectares of native<br />

pinewoods have been planted, with<br />

the support of Forestry Commission<br />

Scotland. The network of capercaillie<br />

Natura sites (Special Protection Areas)<br />

is also being expanded by the Scottish<br />

Executive – so capercaillie should have<br />

more suitable habitat in future. All the<br />

key forests for capercaillie are now<br />

being managed with the birds in mind,<br />

and the <strong>RSPB</strong> will continue <strong>to</strong> provide<br />

advice until the capercaillie population<br />

is secure.<br />

The main difficulty ahead for these<br />

birds may be the damaging impact<br />

that the weather can have during the<br />

breeding season. However, we hope<br />

that by improving the habitat there<br />

will be more food and shelter <strong>to</strong> help<br />

chicks <strong>to</strong> survive in bad weather.<br />

Capercaillie populations in Scotland had crashed by the end of the<br />

last century but are showing some signs of <strong>recovery</strong><br />

Acknowledgements<br />

1100<br />

1999<br />

2000<br />

2004<br />

Much of the work for capercaillie has been funded by EU-Life. Partners in the Capercaillie BAP Group are<br />

Centre for Ecology and Hydrology (Joint lead partner), Scottish Natural Heritage, Forestry Commission<br />

Scotland, Scottish Rural Property and Business Association, Game Conservancy Trust, Royal Zoological<br />

Society of Scotland, Scottish Gamekeepers’ Association, Forestry and Timber Association, Deer Commission<br />

for Scotland, and Dr Robert Moss. Project partners carry out work and/or provide co-financing <strong>to</strong> the project.<br />

We would also like <strong>to</strong> thank innumerable forest owners and land managers, and enthusiastic individuals<br />

<strong>to</strong>o numerous <strong>to</strong> mention.<br />

13

Chough<br />

Following a huge his<strong>to</strong>ric decline, chough populations are<br />

showing signs of <strong>recovery</strong>. However, the <strong>RSPB</strong> is urging<br />

government <strong>to</strong> develop agri-environment policies <strong>to</strong> secure<br />

suitable grazing management for choughs.<br />

Species status<br />

Phase of <strong>recovery</strong>:<br />

Recovery<br />

Amber list Bird of Conservation Concern<br />

BAP priority: Wales and Northern Ireland<br />

Andy Hay (rspb-images.com)<br />

The future looks brighter for choughs in the UK than it has done for decades.<br />

Chough declines<br />

These striking black birds with<br />

red beaks are members of the<br />

crow family and in the past,<br />

especially during the 19th<br />

century, their numbers declined<br />

because they were shot as pests.<br />

Once the chough had become<br />

rare, their eggs became attractive<br />

<strong>to</strong> egg collec<strong>to</strong>rs. Even now<br />

choughs are persecuted –<br />

sometimes as they are mistaken<br />

for other birds in the crow family<br />

– and egg theft still takes place.<br />

Changes in farming seem <strong>to</strong> have<br />

contributed <strong>to</strong> the decline in some<br />

areas. Choughs need enclosed nest<br />

sites and well grazed cliff slopes<br />

or hillsides <strong>to</strong> feed on. Lives<strong>to</strong>ck<br />

has been moved away from some<br />

of these areas, which leads <strong>to</strong> the<br />

vegetation becoming <strong>to</strong>o tall for the<br />

birds <strong>to</strong> feed. Some of these grassy<br />

cliff<strong>to</strong>ps are now used for arable<br />

cropping.<br />

What choughs need<br />

Over the last 10 years choughs have<br />

been studied <strong>to</strong> see what they eat and<br />

where they prefer <strong>to</strong> feed. We found<br />

that choughs take invertebrates from,<br />

or just below, the surface and that they<br />

prefer <strong>to</strong> feed in very short vegetation<br />

with bare areas.<br />

Taking action<br />

Choughs are found predominantly on<br />

western coasts. There are choughs on<br />

a number of <strong>RSPB</strong> reserves including<br />

South Stack and Ramsey Island in<br />

Wales, Oronsay and Loch Gruinart,<br />

Smaull Farm, the Oa and Ardnave<br />

on Islay, Scotland. The <strong>RSPB</strong> is also<br />

involved with protecting isolated<br />

populations in Cornwall and Northern<br />

Ireland, and is helping <strong>to</strong> find out<br />

more about chough feeding habits on<br />

the Isle of Man <strong>to</strong> secure their future.<br />

Different approaches <strong>to</strong> managing<br />

the land for choughs are being taken<br />

in different places in the UK. Some<br />

management is geared <strong>to</strong>wards<br />

providing nesting sites, which are<br />

usually ledges on cliffs or in caves,<br />

and the lofts of derelict buildings.<br />

Other work is <strong>to</strong> ensure there are<br />

places for choughs <strong>to</strong> feed, by using<br />

lives<strong>to</strong>ck <strong>to</strong> graze the land.<br />

14<br />

<strong>Lifeline</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>recovery</strong> – the <strong>RSPB</strong>’s species <strong>recovery</strong> success in the UK

Right: Choughs feed on invertebrates<br />

from, or just below, the surface and<br />

will also take invertebrates from dung.<br />

Grazing is essential <strong>to</strong> maintain<br />

a suitable vegetarian structure<br />

Below: Extensive research and<br />

moni<strong>to</strong>ring (here in Northern Ireland)<br />

has given us a much better<br />

understanding of the chough’s<br />

requirements.<br />

Andy Hay (rspb-images.com)<br />

This also benefits other species: the<br />

bare soil that results from grazing may<br />

benefit insects such as the hornet<br />

robber fly, and on machair in the<br />

Western Isles of Scotland, wading<br />

birds breed on chough feeding habitat.<br />

Government and EU funding in Wales<br />

has enabled the <strong>RSPB</strong> <strong>to</strong> work with<br />

landowners <strong>to</strong> provide suitable habitat<br />

for choughs in 18 key areas, mainly<br />

coastal, and in the west of the country.<br />

In Scotland, a government-funded<br />

scheme has secured agreements<br />

with landowners <strong>to</strong> provide suitable<br />

management for choughs, such as<br />

winter grassland grazing by lives<strong>to</strong>ck.<br />

There are good reasons for optimism:<br />

chough numbers have increased<br />

over the last 20 years and birds have<br />

recolonised sites from which they had<br />

previously disappeared. In Cornwall,<br />

a pair of choughs has bred successfully<br />

since 2002, after half a century of<br />

absence. Volunteers watch the site<br />

24-hours a day during the incubation<br />

stage <strong>to</strong> protect it from egg thieves,<br />

and large numbers of visi<strong>to</strong>rs enjoy<br />

seeing these birds from a public<br />

viewpoint.<br />

Choughs have also returned <strong>to</strong><br />

Northern Ireland. There, the <strong>RSPB</strong><br />

works closely with local farmers and<br />

the Environment and Heritage Service,<br />

<strong>to</strong> manage the grazing <strong>to</strong> benefit<br />

choughs within the Antrim Coast,<br />

Glens and Rathlin Island<br />

Environmentally Sensitive Area.<br />

What next?<br />

The prospects for choughs are better<br />

than for several decades, with birds<br />

breeding in all four countries of the<br />

UK. The UK and Isle of Man hold the<br />

majority of the northwest European<br />

breeding population. The <strong>RSPB</strong> is<br />

providing suitable conditions for<br />

choughs on its nature reserves,<br />

including Rathlin Island, in Northern<br />

Ireland, which we hope they will<br />

recolonise. Farmers, using<br />

agri-environment schemes,<br />

have the potential <strong>to</strong> encourage<br />

further increases in numbers.<br />

However, <strong>to</strong> ensure this <strong>recovery</strong><br />

continues, it is essential that grazing is<br />

maintained in coastal areas <strong>to</strong> keep<br />

the land suitable for choughs <strong>to</strong><br />

find food.<br />

The <strong>RSPB</strong> is providing advice on the<br />

development of agri-environment<br />

schemes, such as Tir Gofal, for Wales,<br />

and other European funding schemes.<br />

We are also urging the Countryside<br />

Council for Wales <strong>to</strong> consider<br />

designating key chough areas as<br />

Special Protection Areas.<br />

Andy Hay (rspb-images.com)<br />

National surveys, held every five years, show that the numbers<br />

of choughs have increased since 1982 in most parts of the UK<br />

Wales<br />

Scotland<br />

Isle of Man<br />

Northern Ireland<br />

England<br />

UK/IoM <strong>to</strong>tal<br />

1982<br />

142<br />

72<br />

60<br />

10<br />

0<br />

284<br />

1992<br />

177<br />

88<br />

77<br />

2<br />

0<br />

344<br />

2002<br />

262<br />

83<br />

151<br />

1<br />

1<br />

498<br />

Because of the difficulties of surveying choughs these figures are subject <strong>to</strong> slight variation.<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

Thanks <strong>to</strong> farmers and landowners across the UK who have supported our work <strong>to</strong> manage coastal and hill land<br />

for choughs. Also <strong>to</strong>: The Welsh European Funding Office, Countryside Council for Wales and Enfys, for funding chough<br />

work in Wales. Other key partners in Wales are Snowdonia and Pembrokeshire National Parks, Pembrokeshire’s Living<br />

Heathland project and Ceredigion County Council. Scottish Natural Heritage and Heritage Lottery Fund for funding<br />

chough management in the Hebrides. The Manx Government for financial support for chough studies on the Isle of<br />

Man, and Manx Atlas for their administrative support. The Department of Agriculture and Rural Development in<br />

Northern Ireland, in partnership with the NI Chough BAP Group.<br />

Moni<strong>to</strong>ring chough breeding in England, and favourable habitat management of coastal habitats in Devon and Cornwall,<br />

is part of Action for Birds in England, a conservation partnership between English Nature and the <strong>RSPB</strong>.<br />

15

Cirl bunting<br />

The cirl bunting is the UK’s rarest resident farmland bird.<br />

Twenty-five percent of the population is threatened directly<br />

or indirectly by development.<br />

Species status<br />

Phase of <strong>recovery</strong>:<br />

Recovery<br />

Red list Bird of Conservation Concern<br />

UK BAP lead partner – the <strong>RSPB</strong>/English<br />

Nature<br />

Chris Gomersall (rspb-images.com)<br />

<strong>RSPB</strong> research found that the widespread loss of low intensity mixed farms was responsible for the decline of the cirl bunting.<br />

The cirl bunting is the UK’s<br />

rarest resident farmland bird<br />

with a population of only 700<br />

pairs. These birds are found in<br />

Devon, in an area up <strong>to</strong> 15 km<br />

from the coast between Exeter<br />

and Plymouth.<br />

Agricultural changes<br />

In the 1930s cirl buntings were<br />

widespread in southern England<br />

and were known as the village<br />

bunting. Numbers have crashed<br />

since then and by 1989 there were<br />

only about 120 pairs left in the UK,<br />

most of these in south Devon.<br />

<strong>RSPB</strong> research discovered<br />

that changes in land management<br />

had reduced the food available<br />

<strong>to</strong> the buntings – especially in winter –<br />

and the number of suitable nest sites.<br />

■ Changing from spring <strong>to</strong> autumn<br />

sown cereals meant there were<br />

fewer winter food sources. The<br />

decline of s<strong>to</strong>oking (the gathering<br />

of cut wheat or straw in<strong>to</strong> bundles,<br />

ready <strong>to</strong> be taken <strong>to</strong> the farmyard),<br />

the loss of threshing yards, and the<br />

increased use of pesticides resulted<br />

in fewer weedy stubbles.<br />

■ Using more pesticides and fertilisers<br />

on crops and grassland meant there<br />

were fewer insects – especially<br />

grasshoppers – for the young<br />

birds <strong>to</strong> eat in summer.<br />

■ Removing hedges and bushes<br />

meant there were fewer suitable<br />

places for nesting.<br />

■ Traditional mixed farms have virtually<br />

disappeared and areas have become<br />

specialised so that there is mostly<br />

grassland in the west and arable<br />

land in the east.<br />

Cirl buntings don’t travel far, usually<br />

moving no more than 2 km between<br />

their breeding and wintering areas. This<br />

lack of movement may be the key <strong>to</strong><br />

why cirl buntings were almost lost<br />

from the UK. Losing just one habitat<br />

component from an area, such as<br />

winter food, makes it unsuitable for<br />

these birds and they are likely <strong>to</strong> be<br />

lost. Once cirl buntings are lost from<br />

an area, they are unlikely <strong>to</strong> recolonise<br />

unless there are breeding birds within<br />

about 2 kms.<br />

16<br />

<strong>Lifeline</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>recovery</strong> – the <strong>RSPB</strong>’s species <strong>recovery</strong> success in the UK

Right: As well as helping birds,<br />

some of our rarest arable<br />

plants are benefiting from<br />

cereals grown with reduced<br />

pesticides, such as this<br />

weasel’s snout.<br />

(Malcolm S<strong>to</strong>rey www.bioimages.org.uk)<br />

These findings were used <strong>to</strong> develop<br />

specific options for cirl buntings within<br />

the Countryside Stewardship Scheme,<br />

the forerunner <strong>to</strong> the Government’s<br />

Environmental Stewardship Scheme.<br />

Making progress<br />

The cirl bunting is a UK and Devon<br />

Biodiversity Action Plan species and<br />

since 1993 a cirl bunting project officer<br />

has worked with landowners <strong>to</strong> provide<br />

cirl buntings with good quality habitat.<br />

Suitable habitat for the birds has<br />

been created through project officer<br />

advice and government grants <strong>to</strong><br />

hundreds of land managers, enabling<br />

them <strong>to</strong> farm in a wildlife friendly way.<br />

A special management prescription<br />

for the cirl bunting, for which the<br />

<strong>RSPB</strong> pressed hard, has encouraged<br />

many landowners <strong>to</strong> provide weedy<br />

stubbles that are vital for the birds’<br />

winter survival.<br />

Thanks <strong>to</strong> this work, the cirl bunting<br />

population has increased dramatically<br />

<strong>to</strong> around 700 pairs. Cirl buntings<br />

increased by 146% on farms that were<br />

part of the Countryside Stewardship<br />

Scheme (CSS) compared with only<br />

56% on areas that were not. Now,<br />

more than 50% of cirl buntings breed<br />

on land managed for them as part of<br />

the CSS and another 45% are within<br />

two kilometres of a CSS scheme. The<br />

farmers who have joined the scheme<br />

say that they have found the support<br />

and advice from the <strong>RSPB</strong>, the<br />

Farming and Wildlife Advisory<br />

Group and Defra very valuable.<br />

Habitat that is good for cirl buntings<br />

is also good for skylarks and woodlarks<br />

<strong>to</strong> nest in. Brown hares also benefit<br />

from spring cropping. Thick hedges<br />

where cirl buntings nest are a<br />

wonderful habitat <strong>to</strong>o and barn owls<br />

also use rough grassland around fields.<br />

Stubbles are a vital winter food source<br />

for many of our farmland birds, and can<br />

even provide habitat for rare mosses<br />

What next?<br />

The cirl bunting population remains<br />

vulnerable. Although numbers have<br />

increased, there has not been a<br />

corresponding expansion in range. The<br />

species can be vulnerable <strong>to</strong> severe<br />

winter weather: prolonged snow cover<br />

would be less worrying if the<br />

population was more widely dispersed.<br />

Birds that rely on small areas of habitat<br />

are also very susceptible <strong>to</strong> any loss<br />

or changes. Away from the coast,<br />

cirl buntings often breed around the<br />

edges of settlements, inhabiting land<br />

between housing and farmland. This<br />

is prime development land, which can<br />

result in the loss of habitat. If there<br />

is nowhere for the cirl buntings <strong>to</strong><br />

go, they are lost.<br />

The future<br />

Cirl bunting terri<strong>to</strong>ries<br />

800<br />

600<br />

400<br />

200<br />

0<br />

1982 1985<br />

Voluntary<br />

set-aside<br />

1988<br />

Setaside<br />

<strong>RSPB</strong><br />

stubbles<br />

The <strong>RSPB</strong> continues <strong>to</strong> work with<br />

farmers and local communities <strong>to</strong> help<br />

the cirl bunting population <strong>to</strong> grow. Its<br />

future looks more secure than it did<br />

10 years ago, but there are still big<br />

challenges <strong>to</strong> be met.<br />

We will be working with Local Authorities<br />

and developers <strong>to</strong> ensure that important<br />

areas are not developed, and that any<br />

impacts on cirl buntings are minimised.<br />

To secure a long-term future for cirl<br />

buntings, their range needs <strong>to</strong> be<br />

expanded. This will only be achieved<br />

through further and more wide ranging<br />

changes in agricultural policy <strong>to</strong><br />

encourage farming that supports both<br />

farmers and wildlife. To aid the <strong>recovery</strong><br />

and <strong>to</strong> reduce the risk of the Devon<br />

population crashing, the <strong>RSPB</strong> and<br />

English Nature are working on plans<br />

<strong>to</strong> establish a population outside<br />

the county.<br />

Cirl bunting populations have responded well <strong>to</strong> species<br />

<strong>recovery</strong> initiatives<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

Countryside<br />

Stewardship<br />

Special project<br />

1991 1994 1997 2000 2003<br />

Thank you <strong>to</strong> all the farmers and volunteers who have been involved with the project, without the support<br />

of farmers, cirl buntings could have been lost from the UK. Thanks also <strong>to</strong> the Defra project officers, local<br />

authority staff who have supported the project, CJ Wildbird Foods who have provided free seed and other<br />

non-governmental organisations, particularly the National Trust, who have helped <strong>to</strong> promote cirl bunting<br />

conservation.<br />

Cirl bunting <strong>recovery</strong> work is part of Action for Birds in England, a conservation partnership between<br />

English Nature and the <strong>RSPB</strong>.<br />

17

Corncrake<br />

The <strong>recovery</strong> of the corncrake population in Scotland, which<br />

started in the early 1990s, is continuing. A translocation project<br />

is underway <strong>to</strong> assist the return of the corncrake <strong>to</strong> England.<br />

Species status<br />

Phase of <strong>recovery</strong>:<br />

Recovery<br />

Red list Bird of Conservation Concern<br />

UK BAP lead partner – the <strong>RSPB</strong><br />

Andy Hay (rspb-images.com)<br />

After more than 20 years of species <strong>recovery</strong> work, the call of the corncrake is being heard more widely once again.<br />

Corncrakes are closely related <strong>to</strong><br />

moorhens and coots. They spend<br />

the winter in Africa, returning <strong>to</strong><br />

the UK in spring. The males arrive<br />

in April, and start singing <strong>to</strong><br />

attract a female as they return<br />

from migration. Their distinctive<br />

rasping ‘crex crex’ call gives<br />

them their scientific name: Crex<br />

crex.<br />

Corncrakes retreat<br />

Corncrakes used <strong>to</strong> be widespread<br />

and common across the UK, but<br />

about 150 years ago it was noticed<br />

that they were declining from the<br />

east. Knowledge of this familiar<br />

but secretive bird was very sketchy<br />

and, although it was suspected that<br />

the decline was linked <strong>to</strong> changes<br />

in management of grass fields and<br />

meadows, it was unclear what was<br />

happening. The decline continued<br />

through the 20th century until, by the<br />

1990s, they were restricted almost<br />

entirely <strong>to</strong> the islands on the north<br />

and west coasts of Scotland.<br />

Corncrakes have been lost from many<br />

areas of Europe and, although some<br />

big populations remain in eastern<br />

states, most countries have lost<br />

at least 20% of their corncrakes.<br />

What happened?<br />

By the late 1980s, it was clear that<br />

the UK corncrake population was in<br />

a critical state. However, it was also<br />

evident that our understanding of<br />

this bird’s ecology was relatively poor.<br />

<strong>RSPB</strong> research revealed that<br />

corncrakes need tall (20 cm+)<br />

invertebrate-rich vegetation throughout<br />

the breeding season, that the birds can<br />

easily walk through. It also found that<br />

the species is adversely affected by<br />

mechanical mowing. This information<br />

was used <strong>to</strong> develop and refine<br />

management techniques, which were<br />

trialled on <strong>RSPB</strong> reserves, notably on<br />

the Hebridean islands of Coll and Islay.<br />

Measures included the adoption of<br />

‘corncrake friendly’ mowing methods.<br />

This means that fields are mowed in a<br />

way which pushes the birds <strong>to</strong>wards<br />

cover in which they will be safe once<br />

18<br />

<strong>Lifeline</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>recovery</strong> – the <strong>RSPB</strong>’s species <strong>recovery</strong> success in the UK

Right: <strong>RSPB</strong> reserves have hosted<br />

detailed research in<strong>to</strong> practical ways<br />

<strong>to</strong> provide corncrake habitat.<br />

Below: simple measures, such as this<br />

‘corncrake corridor’ – ideal habitat<br />

for corncrakes – can make all<br />

the difference for these birds.<br />

Andy Hay (rspb-images.com)<br />

the crop is cut without forcing them <strong>to</strong><br />

cross an already-cut area. This usually<br />

means mowing fields from the centre<br />

outwards, rather than the more<br />

traditional out-in, which traps the birds<br />

in the centre. Other measures include<br />

changes in grazing management <strong>to</strong><br />

provide areas of vegetation cover<br />

throughout the breeding cycle, and<br />

the provision of corncrake ‘corners’<br />

and ‘corridors’ <strong>to</strong> ensure that sufficient<br />

cover is available during the early and<br />

late parts of the breeding season.<br />

Taking the initiative<br />

Once successful management<br />

techniques had been developed,<br />

these were implemented in the key<br />

corncrake areas. Fieldworkers advised<br />

farmers and crofters and offered them<br />

grant aid <strong>to</strong> support corncrake friendly<br />

practices through the <strong>RSPB</strong>/Scottish<br />

Crofting Foundation/Scottish Natural<br />

Heritage Corncrake Initiative. The key<br />

techniques were demonstrated on<br />

nature reserves so that other land<br />

managers could see at first hand<br />

what is involved. The <strong>RSPB</strong> pressed<br />

successfully for the inclusion<br />

of corncrake measures in<br />

agri-environment funding schemes<br />

for farmers. Working in partnership<br />

with crofters and farmers has resulted<br />

in changes in grassland management<br />

leading, in turn, <strong>to</strong> an increase in the<br />

UK corncrake population. It has also<br />

benefited other important species<br />

such as the great yellow bumblebee,<br />

a BAP species for which the <strong>RSPB</strong> is<br />

lead partner.<br />

The future<br />

The corncrake remains in a precarious<br />

position, but current signs are<br />

encouraging. The population <strong>recovery</strong>,<br />

which started in the early 1990s,<br />

continues, with a survey of Core Areas<br />

(Orkney and the Hebrides, generally<br />

encompassing around 90% of the<br />

national population) recording 1,042<br />

calling males in 2004. The next<br />

challenge is <strong>to</strong> expand the species’<br />

range. Management work will be<br />

targeted <strong>to</strong>wards areas with high<br />

re-colonisation potential. The <strong>RSPB</strong><br />

is undertaking a trial <strong>to</strong> re-establish<br />

corncrakes in eastern England. Though<br />

it is <strong>to</strong>o early <strong>to</strong> say whether this will<br />

be successful in the long term, a first<br />

breeding record at the release site<br />

is encouraging.<br />

The Corncrake Initiative remains<br />

an important mechanism for funding<br />

corncrake management. However,<br />

favourable grassland measures under<br />

agri-environment schemes (such as<br />

the Environmentally Sensitive Areas<br />

scheme and the Rural Stewardship<br />

Scheme in Scotland) are increasing<br />

the land under favourable<br />

management. This will be essential<br />

if the <strong>recovery</strong> of the corncrake<br />

is <strong>to</strong> be assured.<br />

Chris Gomersall (rspb-images.com)<br />

Five-yearly national surveys show a steady increase in population, and<br />

counts in core areas in Scotland demonstrate the sustained <strong>recovery</strong><br />

Calling males<br />

1200<br />

1000<br />

800<br />

600<br />

400<br />

200<br />

0<br />

1978<br />

1988<br />

1989<br />

1990<br />

1991<br />

1992<br />

1993<br />

1994<br />

1995<br />

1996<br />

1997<br />

1998<br />

1999<br />

2000<br />

2001<br />

2002<br />

2003<br />

2004<br />

Total in GB & IoM<br />

Total in Core Areas<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

The <strong>recovery</strong> of the corncrake in Scotland has been the result of a partnership between the<br />

<strong>RSPB</strong>, Scottish Natural Heritage, the Scottish Executive, farming and crofting organisations,<br />

and the agricultural communities of the north and west coast.<br />

The re-introduction of corncrakes <strong>to</strong> the Nene Washes is part of Action for Birds in England,<br />

a conservation partnership between English Nature and the <strong>RSPB</strong> with the Zoological Society<br />

of London. We would also like <strong>to</strong> thank Chester Zoo.<br />

19

Hen harrier<br />

<strong>RSPB</strong> nature reserves hold around 7% of the UK hen harrier<br />

population, even though moorland managed by the <strong>RSPB</strong><br />

accounts for just under 1% of the UK’s <strong>to</strong>tal.<br />

Species status<br />

Phase of <strong>recovery</strong>:<br />

Recovery<br />

Red list Bird of Conservation Concern<br />

BAP priority: Wales and Northern<br />

Ireland<br />

Laurie Campbell (rspb-images.com)<br />