The Lower Thames Crossing - Kent County Council

The Lower Thames Crossing - Kent County Council

The Lower Thames Crossing - Kent County Council

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Lower</strong><br />

<strong>Thames</strong> <strong>Crossing</strong><br />

<strong>Kent</strong> <strong>County</strong> <strong>Council</strong><br />

KPMG Regeneration and Funding Report<br />

Final Version<br />

August 2010

Important notice<br />

<strong>The</strong> information in this report is based upon information provided by or on behalf of <strong>Kent</strong> <strong>County</strong> <strong>Council</strong> and reflects<br />

prevailing conditions and our views as of this date, all of which are accordingly subject to change. In preparing this<br />

report, we have relied upon and assumed, without independent verification, the accuracy and completeness of all<br />

information provided to us.<br />

<strong>The</strong> quantitative economic analysis contained in this report is related to three alternative <strong>Lower</strong> <strong>Thames</strong> crossing options:<br />

from east of Gravesham to Stanford-le-Hope; from east of Gravesham to Chadwell and close to or at the existing<br />

Dartford crossing. Analysis of funding and procurement approaches relates to the proposed Gravesham to Stanford-le-<br />

Hope crossing. Although we endeavour to provide accurate and timely information, there can be no guarantee that such<br />

information is accurate as of the date it is received or that it will continue to be accurate in the future. No one should act<br />

upon such information without appropriate professional advice after a thorough examination of the particular situation.<br />

This report was prepared for <strong>Kent</strong> <strong>County</strong> <strong>Council</strong> and can only be circulated within the terms of the engagement<br />

contract signed between the <strong>Council</strong> and KPMG LLP. Any party who obtains access to and chooses to rely on this report<br />

(or any part of it) will do so at its own risk. Whilst the information presented and views expressed in this report and<br />

related discussions have been prepared in good faith, <strong>Kent</strong> <strong>County</strong> <strong>Council</strong> and KPMG LLP accept no responsibility or<br />

liability to any party in connection with such information or views.<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Lower</strong> <strong>Thames</strong> <strong>Crossing</strong> <strong>Kent</strong> <strong>County</strong> <strong>Council</strong><br />

@ 2010 KPMG LLP, a UK limited liability partnership, is a subsidiary of KPMG Europe LLP and a member firm of the KPMG<br />

network of independent member firms affiliated with KPMG International Cooperative, a Swiss entity. All rights reserved.

Contents<br />

1 Executive Summary ___________________________________________________________ 1<br />

1.1 Likely regeneration impacts 1<br />

1.2 Funding 2<br />

1.3 Financing and procurement approaches 5<br />

1.4 Conclusions 5<br />

2 Introduction __________________________________________________________________ 7<br />

2.1 Background 7<br />

2.2 Purpose of this report 7<br />

3 Economic assessment framework ________________________________________________ 9<br />

3.1 Introduction 9<br />

3.2 Overview of methodology 9<br />

3.3 Measuring connectivity 10<br />

3.4 Data sources 13<br />

3.5 Assessing business location choice 18<br />

3.6 Considering relative connectivity and business mobility 19<br />

3.7 Assessing agglomeration and productivity 20<br />

3.8 Testing scenarios 21<br />

4 Strategic economic and regeneration impacts ______________________________________ 22<br />

4.1 <strong>The</strong> scenarios tested 22<br />

4.2 Changes in business location 23<br />

4.3 Changes in productivity 23<br />

4.4 Implications for economic output 24<br />

5 Costs _____________________________________________________________________ 25<br />

5.1 Capital costs 25<br />

5.2 Maintenance costs 25<br />

5.3 Unitary charge under a PPP 26<br />

6 Toll revenues _______________________________________________________________ 27<br />

6.1 Toll revenues from a Stanford-le-Hope to Gravesham crossing 27<br />

6.2 Relationship with the existing Dartford crossing 28<br />

7 Funding ____________________________________________________________________ 30<br />

7.1 Distinguishing funding from finance 30<br />

7.2 Funding from Department for Transport 30<br />

7.3 European support 30<br />

7.4 Lorry road user charging 31<br />

7.5 Capturing economic benefits 31<br />

8 Procurement and financing options ______________________________________________ 33<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Lower</strong> <strong>Thames</strong> <strong>Crossing</strong> <strong>Kent</strong> <strong>County</strong> <strong>Council</strong><br />

@ 2010 KPMG LLP, a UK limited liability partnership, is a subsidiary of KPMG Europe LLP and a member firm of the KPMG<br />

network of independent member firms affiliated with KPMG International Cooperative, a Swiss entity. All rights reserved.

8.1 Introduction 33<br />

8.2 Review of the project from a procurement perspective 34<br />

8.3 Conventional procurement and delivery partner approaches 36<br />

8.4 Public Private Partnership 36<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Lower</strong> <strong>Thames</strong> <strong>Crossing</strong> <strong>Kent</strong> <strong>County</strong> <strong>Council</strong><br />

@ 2010 KPMG LLP, a UK limited liability partnership, is a subsidiary of KPMG Europe LLP and a member firm of the KPMG<br />

network of independent member firms affiliated with KPMG International Cooperative, a Swiss entity. All rights reserved.

1 Executive Summary<br />

KPMG has been commissioned by <strong>Kent</strong> <strong>County</strong> <strong>Council</strong> to undertake a high level assessment of the wider<br />

economic and regeneration impacts of a new <strong>Lower</strong> <strong>Thames</strong> crossing and potential funding, financing and<br />

procurement options for delivering this. <strong>The</strong> analysis of wider economic and regeneration impacts on local areas<br />

in North <strong>Kent</strong> and South Essex has considered three crossing options: new capacity at or near to the existing<br />

crossing location; a new crossing between Chadwell and Gravesham and a new crossing from Eastern<br />

Gravesham to Stanford-le-Hope. Assessments of how a new river crossing could be funded and financed as well<br />

as high level procurement options are based on a proposed crossing from Eastern Gravesham to Stanford-le-<br />

Hope.<br />

1.1 Likely regeneration impacts<br />

<strong>The</strong> proposed new crossing sits within the wider context of the <strong>Thames</strong> Gateway Growth Area, the UK’s largest<br />

regeneration project. <strong>The</strong> <strong>Thames</strong> Gateway growth area stretches from East London to North <strong>Kent</strong> and South<br />

Essex. <strong>The</strong> <strong>Thames</strong> Gateway delivery plan outlines an expected growth in jobs of 225,000, and 110,000 new<br />

homes by 2016 1 although these projections however were produced before the recession of the recent years,<br />

and may not now be achievable.<br />

Improving connections between the north and south of the river in the <strong>Thames</strong> Gateway would make travel<br />

between them easier, expanding the size and depth of local labour markets on both sides of the river and<br />

enabling easier trade and business to business communication across the river. <strong>The</strong> economic evidence<br />

suggests that improvements in connectivity could lead to improvements in productivity and in attracting increased<br />

economic activity to the area.<br />

Three scenarios have been considered in the quantitative analysis of regeneration impacts:<br />

■ A scenario where capacity is increased at or close to the existing crossing;<br />

■ A new crossing from Stanford-le-Hope to Eastern Gravesham; and<br />

■ A new crossing from Chadwell to Gravesham.<br />

See Figure 8 on page 22 for a map of crossing options considered. Relieving congestion at the existing Dartford<br />

crossing would improve the experience of users of the existing crossing. However, this would not offer new<br />

journey opportunities or connections between businesses in local areas on different sides of the <strong>Thames</strong> estuary.<br />

<strong>The</strong> new crossing options that we have examined downstream of the existing bridge would provide decongestion<br />

benefits on the existing crossing and a new range of journey opportunities offering larger journey time savings for<br />

some trips. For example, both the Stanford-le-Hope to Eastern Gravesham and the Chadwell to Gravesham<br />

options would improve connections from the Medway towns to the North and from Southend and Chelmsford to<br />

areas in <strong>Kent</strong> and to Dover.<br />

Analysis suggests that the productivity benefits through agglomeration of economic activity could be around:<br />

■ £2m 2 per annum from reducing congestion on the existing crossing;<br />

■ £15m per annum from a new crossing from Chadwell to Gravesham; and<br />

■ £11m per annum from a new crossing from Stanford-le-Hope to Eastern Gravesham.<br />

1 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Thames</strong> Gateway Delivery Plan, HM Government, 2007<br />

2 Expressed as an annual benefit in 2021 in 2002 prices<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Lower</strong> <strong>Thames</strong> <strong>Crossing</strong> <strong>Kent</strong> <strong>County</strong> <strong>Council</strong> ⏐ 1<br />

@ 2010 KPMG LLP, a UK limited liability partnership, is a subsidiary of KPMG Europe LLP and a member firm of the KPMG<br />

network of independent member firms affiliated with KPMG International Cooperative, a Swiss entity. All rights reserved.

Note that these are annual figures and do not represent a discounted flow of benefits as is common in transport<br />

appraisal. <strong>The</strong>se results assume no changes in land use and have been estimated using parameters drawn from<br />

the DfT’s WebTAG appraisal guidance.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re is evidence that the connectivity offered to businesses by the road network is related to business location<br />

choice, although the economic evidence to quantify such relationships is unclear in the data that has been<br />

available to us. While there is some uncertainty over the appropriate parameters for forecasting local employment<br />

outcomes, assumptions consistent with the best fit statistical equations suggest that the increase in employment<br />

in the areas of North <strong>Kent</strong> and South Essex could be around:<br />

■ 1,000 from reducing congestion at the existing crossing;<br />

■ 4,000 from a new crossing from Stanford-le-Hope to Eastern Gravesham; and<br />

■ 6,000 from a new crossing from Chadwell to Gravesham.<br />

Within this local geography, such employment impacts would have a larger influence on local economic output<br />

than changes in business productivity. <strong>The</strong> overall GVA impacts of the Chadwell to Gravesham crossing could be<br />

around £334m per annum in 2021 at 2002 prices. This implies that the discounted value of additional growth in<br />

economic activity in the study area as a result of this scheme could be £12.7bn, although this should be treated<br />

with caution as future changes in additional employment and productivity have been treated as constant over<br />

time. Changes in these benefits over time will therefore affect this analysis.<br />

<strong>The</strong> changes in connectivity brought about by the different crossing options indicates that a crossing to the east<br />

of the existing Dartford crossing would have a significantly larger impact on the connectivity of the areas in North<br />

<strong>Kent</strong> and South Essex where aspirations for future economic growth are high. If access to potential employees<br />

and access to other businesses does affect the attractiveness of locations as places to do business, then the<br />

impacts on employment in North <strong>Kent</strong> and South Essex could be up to eight times larger if new crossing capacity<br />

is provided to the east of the existing crossing rather than simply relieving capacity at the current crossing<br />

location.<br />

<strong>The</strong> local economic growth implications of a proposed new crossing fit in well with the context of the new<br />

government’s spending review and focus on economic outcomes for funding infrastructure schemes.<br />

<strong>The</strong> modelling has not taken into account resilience and reliability impacts of a new <strong>Thames</strong> crossing.<br />

Reassignment of traffic from the Dartford <strong>Crossing</strong> will enable bifurcation of traffic on an already very congested<br />

part of the road network. This in turn will generate congestion relief benefits, and reduce variability in journey<br />

times. <strong>The</strong> benefits of network resilience will not only be captured by local traffic, but also at a regional and<br />

national level, and is in line with the recent London to Dover DaSTS study.<br />

1.2 Funding<br />

<strong>The</strong> total capital costs of the <strong>Lower</strong> <strong>Thames</strong> crossing have been estimated by MVA Gifford and Capita as being<br />

in the region of £1.0bn in 2008 prices, including an allowance for risk and optimism bias of £0.4bn. <strong>The</strong>se costs<br />

have been used throughout the report but KPMG makes no comment as to their accuracy.<br />

Our analysis of funding options has considered:<br />

■ <strong>The</strong> role of toll revenues;<br />

■ Alternative central government funding sources such as national networks capital budgets, the Regional<br />

Funding Allocation or PFI credits; and<br />

■ Alternative sources of funding such as lorry road user charging and mechanisms for capturing the economic<br />

benefits that could be brought to the local area.<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Lower</strong> <strong>Thames</strong> <strong>Crossing</strong> <strong>Kent</strong> <strong>County</strong> <strong>Council</strong> ⏐ 2<br />

@ 2010 KPMG LLP, a UK limited liability partnership, is a subsidiary of KPMG Europe LLP and a member firm of the KPMG<br />

network of independent member firms affiliated with KPMG International Cooperative, a Swiss entity. All rights reserved.

<strong>The</strong> new crossing would work in tandem with the existing Queen Elizabeth II Bridge and Dartford tunnel, offering<br />

a substitute route and relieving capacity constraints on the current crossings. <strong>The</strong> Thurrock-Dartford crossing is<br />

currently tolled so we have assumed that the new crossing would also be tolled in order to avoid creating<br />

incentives for people to make longer journeys. Tolling strategy for the two crossings must therefore be<br />

considered together.<br />

Toll income could contribute different amounts to the capital costs of the project depending on tolling policy and<br />

which tolls are available to support the scheme costs.<br />

<strong>The</strong> interrelationship with tolls on the existing crossing creates some complexity in determining the funding and<br />

financing approach. If considered together, the combined crossing revenue could represent the single most<br />

important potential source of funding for the scheme. <strong>The</strong> existing crossing currently generates a net operating<br />

surplus of over £40m from its operations now that the capital costs of the crossing have been paid off.<br />

Tolls on the existing crossing act as a tax on movement across the river which make these journeys less<br />

attractive and could restrict the regeneration potential of the study area. Economic modelling of a scenario<br />

without tolls on the existing bridge indicated a potential increase in local employment by around 2,000, and<br />

additional annual economic output of over £115m if these tolls were taken away. As the capital cost of the bridge<br />

has been paid for, an argument could be made that the net operating surplus of the existing bridge should accrue<br />

to the local economic area that currently feels the impact of the toll and which could be used to fund additional<br />

local economic development, for example to fund a new <strong>Lower</strong> <strong>Thames</strong> <strong>Crossing</strong>. In this case, the revenues from<br />

the existing crossing could support around half of the debt required to pay for the capital costs of a new bridge.<br />

However, the existing toll revenues accrue to the DfT and can be deployed for other uses. Hence, a case for the<br />

crossing needs to be prepared that demonstrates both value for money and meets wider DfT objectives. More<br />

broadly, the case must demonstrate that the proposed crossing is of national importance and warrants<br />

redeployment of the revenue from the Dartford crossing or other sources to enable it.<br />

If net revenues from the existing crossing are not made available to fund the new crossing, revenues on the new<br />

crossing represent no more than perhaps 20% of the overall scheme costs, subject to the rate of growth of traffic<br />

after completion. This figure assumes that current toll levels are maintained, and is based on current traffic and<br />

revenue estimates provided to us. It is net of operating costs. Information about long term changes in toll incomes<br />

associated with demand growth has not been available to us. <strong>The</strong> new crossing would provide relief for the<br />

existing crossing which is effectively full, so demand growth for cross river traffic is likely to be accommodated by<br />

the new crossing. This may imply faster than usual demand growth which could result in relatively high traffic<br />

growth on the new crossing. This growth could increase the share of capital costs that could be supported by toll<br />

income from the new bridge. If tolls on the new bridge are considered net of abstraction from the existing<br />

crossing, then the ability of this funding stream to support the capital expenditure becomes very limited.<br />

Potential revenue generation from tolling of the New <strong>Lower</strong> <strong>Thames</strong> crossing is limited by the current low tolls on<br />

the existing Dartford crossing and the high level of substitutability of the crossings. A commercial toll on both<br />

bridges could generate substantial additional income to support the cost of the new crossing. Demand for travel<br />

across the crossing is thought to be relatively inelastic, so changes in tolls are likely to have only a small adverse<br />

impact on traffic levels, although this could be significant for some user groups. Further work on tolling levels and<br />

their impact on demand and the affordability of the new crossing is recommended.<br />

Other central government funding is likely to be limited over the coming years. <strong>The</strong> existing indicative 10 year<br />

RFA budget is already subscribed and is likely to come under pressure in the spending review in the autumn,<br />

with expected cutbacks, the abolition of the regional tier and new prioritisation techniques. National networks<br />

capital budgets are likely to come under similar pressure. Indeed, transport is not one of the departments that has<br />

been protected from expenditure cuts and transport projects have already been targets of emergency cuts. In the<br />

short term, it cannot be assumed that either direct capital grants or PPP credits will be available, although over a<br />

longer timeframe, the growing capacity constraint and national significance of the crossing may make it a priority<br />

for central government investment.<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Lower</strong> <strong>Thames</strong> <strong>Crossing</strong> <strong>Kent</strong> <strong>County</strong> <strong>Council</strong> ⏐ 3<br />

@ 2010 KPMG LLP, a UK limited liability partnership, is a subsidiary of KPMG Europe LLP and a member firm of the KPMG<br />

network of independent member firms affiliated with KPMG International Cooperative, a Swiss entity. All rights reserved.

Our indicative analysis suggests that other sources of possible funding towards meeting the costs of the New<br />

<strong>Lower</strong> <strong>Thames</strong> crossing are not likely to be material to the scheme’s overall affordability unless the funding gap is<br />

already narrowed by a material change to tolls or a substantial other funding source. One exception to this is lorry<br />

road user charging. <strong>The</strong> new government’s coalition agreement 3 commits it to introduce this if elected. If<br />

implemented, it could provide additional income for central government and, if improvements to key freight routes<br />

were part of a combined investment initiative, then a case could be made for some of this income to support the<br />

<strong>Lower</strong> <strong>Thames</strong> crossing as a strategic national priority. If taken forward, a national initiative would overtake other<br />

options to implement a local scheme. To deliver transport investment, innovative forms of local funding are<br />

therefore likely to play a larger role. Transport for London, for example, is investigating tax increment financing<br />

approaches from expected development to fund the Northern Line Extension.<br />

Recent work by the Department for Transport indicates that the <strong>Lower</strong> <strong>Thames</strong> crossing is a strategic national<br />

priority and that central government is actively considering options for it. In April 2009 the DfT published a study<br />

outlining possible proposals to improve traffic flow at the Dartford crossing, and assessing possible options for a<br />

new crossing in the longer-term. Following the Budget in March 2010, the Dartford crossing has been identified<br />

as one of a number of assets within the Operational Efficiency Programme for which government is considering<br />

ways of changing the ownership or management through the sale of a concession to operate for example, in<br />

order to extract maximum value. This has given additional impetus to consideration of new crossing options and<br />

how they could be accommodated within a revised framework for the existing crossing.<br />

Other sources of possible funds could capture some of the local economic benefits that the scheme may deliver.<br />

Using assumptions on employment densities set out in the English Partnerships guide to employment densities,<br />

the additional employment numbers would require up to 170,000 sqm of new development to be built implying<br />

developer contributions could be between £1.7 and £5m. This is insignificant compared to the capital cost of the<br />

new bridge.<br />

Overall impacts on economic output will also have implications for tax revenues. A tentative assumption would be<br />

that 35% of the GVA impacts are captured in taxation and could thus contribute up to £117m per annum (35% of<br />

£334m) in new tax income from local businesses within the study area implying additional business rate income<br />

of around £6m per annum. This could represent a more significant funding stream if it can be captured. Tax<br />

increment financing or supplementary business rate approaches could both be used to appropriate some of these<br />

benefits. However, imposing any general business levy is likely to be seen as unacceptable because of its<br />

negative impact on the local and regional economy. <strong>The</strong>se will need to be explored more fully once the scheme<br />

reaches a full business case development stage.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Medway towns are expected to be some of the most significant beneficiaries of the enhanced connectivity<br />

provided by the two new crossing options, with areas local to the new crossings also benefitting. Dispersion of<br />

the potential regeneration benefits over a wider area suggests that potential financial mechanisms to capture<br />

benefits (such as for example, Section 106 or Community Infrastructure Levy contributions, tax increment<br />

financing approaches or local supplementary business rates) must target a wider area rather than the immediate<br />

vicinity of new bridge infrastructure.<br />

In parallel, <strong>Kent</strong> <strong>County</strong> <strong>Council</strong> should enter into dialogue with the EU to ascertain whether a case could be built<br />

for TEN-T funding. EU grant support, equal to up to 10% (or exceptionally 20%) of total eligible costs, represents<br />

a substantial building block to the affordability package. EIB funding of up to 50% of eligible borrowing, while it is<br />

a loan and not a grant, could assist in the scheme’s affordability by helping to minimise cost of finance.<br />

3 <strong>The</strong> Coalition: our programme for government, Cabinet Office, May 2010, Page 31<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Lower</strong> <strong>Thames</strong> <strong>Crossing</strong> <strong>Kent</strong> <strong>County</strong> <strong>Council</strong> ⏐ 4<br />

@ 2010 KPMG LLP, a UK limited liability partnership, is a subsidiary of KPMG Europe LLP and a member firm of the KPMG<br />

network of independent member firms affiliated with KPMG International Cooperative, a Swiss entity. All rights reserved.

1.3 Financing and procurement approaches<br />

Two broad approaches towards procurement were considered, with different implications for the management of<br />

risk and approach to whole life cost. <strong>The</strong>se are:<br />

1. conventional procurement (which, for the purposes of this review, means that <strong>Kent</strong> <strong>County</strong> <strong>Council</strong> and its<br />

delivery partners take the majority of the asset specific risks); and<br />

2. an approach which includes a greater involvement by the private sector in the whole life risks and project<br />

costs through a Public Private Partnership (PPP) structure.<br />

We are aware that the new government has made some adverse comments about the Private Finance Initiative<br />

but they are understood to wish to encourage the use of third party revenues in infrastructure development. In<br />

general, the features of undertaking a PPP are that the private sector will take the majority of the cost based risks<br />

and will use more complex financing tools to fund the project than are available to the public sector. By<br />

comparison, a conventional procurement approach involves a more selective approach to risk sharing and enjoys<br />

lower costs of borrowing but with a less sophisticated range of financing arrangements.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re is a prima facie case for the formation of a PPP. <strong>The</strong> promoter could also consider the payment of<br />

substantial milestone capital contributions, funded through PWLB borrowing, to further improve affordability. This<br />

procurement approach should be reinvestigated once government transport policy and the project revenues and<br />

costs are better understood. However, the cost of PPP borrowing remains high and any procurement analysis<br />

should be undertaken under a twin-track of PPP and a conventional (possibly delivery partner based) approach<br />

up to the point of development which allows and informed value for money choice to be made.<br />

Although the requirement to manage considerable finance and construction risks suggest that PPP may be a<br />

preferred option, any formal appraisal should however actively consider both approaches in tandem, focused on<br />

the objective of securing best value for money.<br />

1.4 Conclusions<br />

<strong>The</strong> proposed New <strong>Lower</strong> <strong>Thames</strong> crossing project is a significant piece of infrastructure to reduce congestion at<br />

one of the busiest parts of the national transport system. It is expected to provide alterative routes for long<br />

distance traffic of national importance as well as offering enhanced local connectivity to support the economic<br />

and social development of the region. <strong>The</strong> proposed crossing could also contribute to improved public transport<br />

links between <strong>Kent</strong> <strong>Thames</strong>ide and South Essex Growth Areas. It is the aspiration of both <strong>Kent</strong> and Essex<br />

<strong>County</strong> <strong>Council</strong>s to connect the Fastrack and South Essex Rapid Transit (SERT) BRT schemes via the Dartford<br />

and <strong>Lower</strong> <strong>Thames</strong> <strong>Crossing</strong>s to provide a public transport link between the <strong>Kent</strong> <strong>Thames</strong>ide and South Essex<br />

Growth Areas.<br />

Initial quantitative assessment of regeneration impacts suggest that a new crossing from Chadwell to Gravesham<br />

could support up to an additional 6,000 jobs within the study area of North <strong>Kent</strong> and South Essex and productivity<br />

benefits from agglomeration of around £15m per annum in 2021. Within this local geography, such employment<br />

impacts would have a far larger influence on local economic output than changes in business productivity. <strong>The</strong><br />

overall GVA impacts of the Chadwell to Gravesham crossing could be around £334m in 2021 at 2002 prices, if<br />

accounting for the GVA impacts of additional employment moving into the study area. Note that this is an annual<br />

number and not a discounted value as is common in transport appraisal.<br />

Given the traffic forecasts we have had access to and under current tolling arrangements, toll income is unlikely<br />

to cover the capital cost of the project. If toll revenues on the existing crossing form part of the funding package,<br />

then these could support around half of the debt required. However, new toll income generated by the crossing is<br />

unlikely to meet a significant proportion of the capital costs of a new crossing. <strong>The</strong> Department for Transport is<br />

likely to consider toll income, net of abstraction from the existing crossing and net of operating costs in the<br />

business case for the project. A strong economic case is therefore required to demonstrate the case for use of<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Lower</strong> <strong>Thames</strong> <strong>Crossing</strong> <strong>Kent</strong> <strong>County</strong> <strong>Council</strong> ⏐ 5<br />

@ 2010 KPMG LLP, a UK limited liability partnership, is a subsidiary of KPMG Europe LLP and a member firm of the KPMG<br />

network of independent member firms affiliated with KPMG International Cooperative, a Swiss entity. All rights reserved.

existing tolls or other public funds. <strong>The</strong> strategic nature of the crossing, potential links to lorry road user charging<br />

and potentially significant forecast growth from future suppressed demand indicate that there may be a case for<br />

allocating national investment funds. In order to progress this, we recommend that a cost benefit analysis and<br />

business case is developed.<br />

<strong>The</strong> funding contribution from tolls could rise significantly if long term traffic growth projections net of changes in<br />

the existing crossing on the new crossing are high. However, even in this case there is likely to be a significant<br />

funding gap. It therefore seems likely that the majority of the shortfall would have to be met through changes to<br />

tolling arrangement, cross subsidy from the existing crossing or from other central government sources.<br />

<strong>The</strong> substitutability between the existing and new crossings argues for an integrated approach to tolling. <strong>The</strong><br />

extent of the funding shortfall will be driven by the user charging regime (if any) that is put in place. It is our view<br />

that the option that may derive the largest income, and therefore make the largest contribution to the project cost,<br />

is the development of a joint “<strong>Lower</strong> <strong>Thames</strong> crossing corridor” approach with user charges linked to the concept<br />

of providing a high standard motorway route between <strong>Kent</strong> and the Channel ports, and the rest of the UK. Tolls<br />

on both routes would need to be similar to avoid potentially biasing traffic towards longer and less efficient routes.<br />

Differential tolls could also undermine the aspiration to introduce a system of bifurcation for traffic heading from<br />

the North and East of London to the Channel Ports (via the LTC/M2/A2 and QEII/M20/A20 corridors<br />

respectively). Under a joint crossing concept, tolling of the <strong>Lower</strong> <strong>Thames</strong> crossing could be enhanced by a share<br />

of income from the existing crossing, potentially including some extra-inflationary toll increases to assist<br />

affordability.<br />

<strong>The</strong> resulting change in local economic activity and development may also provide opportunities for alternative<br />

funding sources to contribute to the construction of a new crossing provided suitable mechanisms for capturing<br />

them can be implemented.<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Lower</strong> <strong>Thames</strong> <strong>Crossing</strong> <strong>Kent</strong> <strong>County</strong> <strong>Council</strong> ⏐ 6<br />

@ 2010 KPMG LLP, a UK limited liability partnership, is a subsidiary of KPMG Europe LLP and a member firm of the KPMG<br />

network of independent member firms affiliated with KPMG International Cooperative, a Swiss entity. All rights reserved.

2 Introduction<br />

2.1 Background<br />

<strong>The</strong> proposed <strong>Lower</strong> <strong>Thames</strong> crossing is a strategically critical scheme, to meet current and future demand and<br />

to reduce the high level of congestion currently affecting the Dartford crossing.<br />

<strong>The</strong> current Dartford crossing is a highly congested arterial route, providing access between the main channel<br />

crossings and areas north of the <strong>Thames</strong>, and for regional traffic between Essex and <strong>Kent</strong>. In response to the<br />

high level of congestion on the route, <strong>The</strong> Department for Transport commissioned a report from Parsons<br />

Brinckerhoff Ltd to identify options for adding capacity and outlining the technical issues relating to them. This<br />

study, issued in January 2009, drew up a series of options ranging from operational improvements to the existing<br />

Dartford crossing, to the development of an additional crossing. In 2009, the government also published the<br />

Operational Efficiency Programme Asset Portfolio which highlighted the Dartford crossing as one of a number of<br />

strategic national assets for which new delivery arrangements are being considered. This presented options for<br />

alternative asset options taking into account the need for future capacity increases. Together, these documents<br />

imply that the government considers the Dartford crossing to be of national significance and demonstrate their<br />

active consideration of policy options for a new <strong>Lower</strong> <strong>Thames</strong> crossing.<br />

Separately to the DfT commissioned report, in 2008, <strong>Kent</strong> and Essex <strong>County</strong> <strong>Council</strong>s jointly commissioned a<br />

study from Gifford, MVA Consultancy and Capita (henceforth referred to in this report as the MVA study) to<br />

evaluate similar options. This report builds on that study, and in particular takes the cost and traffic forecasts set<br />

out in the MVA study as being correct.<br />

<strong>Kent</strong> <strong>County</strong> <strong>Council</strong> has concluded that the so-called ‘Option C’ (a crossing between Stanford-le-Hope and East<br />

of Gravesham) is the preferred crossing location. <strong>The</strong> funding and finance analysis in this report focuses on that<br />

option and assumes that the crossing will be a bridge and not a tunnel.<br />

<strong>The</strong> scheme is a major capital project. No dedicated budget for the New <strong>Lower</strong> <strong>Thames</strong> crossing Project has<br />

been identified by local or Central Government, although we are aware that the Department for Transport is<br />

considering the potential development of a new crossing as part of its assessment of the Dartford crossing. We<br />

understand that current revenue budgets going forward are fully accounted for, and that the current capital<br />

programme exceeds budgets. <strong>The</strong>refore it is essential to determine from which sources the project might<br />

ultimately be funded if it is to proceed to the procurement stages.<br />

<strong>The</strong> project will have to compete against other projects for the allocation of public resources. As such, the<br />

business case for funding will need to be compelling, demonstrating that:<br />

■ <strong>The</strong>re is a robust value for money case for government funding;<br />

■ <strong>The</strong> crossing is of strategic national importance and importance in securing local development objectives; and<br />

■ All of the viable options to secure external income have been fully explored.<br />

This report considers the strategic economic benefits of supporting development in the <strong>Thames</strong> Gateway and<br />

possible sources of revenue, such as toll charges, and considers the extent to which such sources might meet<br />

the estimated costs of the project. As a part of the development of this paper we have considered recent revenue<br />

generating schemes and funding alternatives from UK and worldwide experience.<br />

2.2 Purpose of this report<br />

<strong>Kent</strong> <strong>County</strong> <strong>Council</strong> has commissioned KPMG to appraise the scheme’s potential to support local economic<br />

development and to provide an initial high level review of options for funding, financing and procurement.<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Lower</strong> <strong>Thames</strong> <strong>Crossing</strong> <strong>Kent</strong> <strong>County</strong> <strong>Council</strong> ⏐ 7<br />

@ 2010 KPMG LLP, a UK limited liability partnership, is a subsidiary of KPMG Europe LLP and a member firm of the KPMG<br />

network of independent member firms affiliated with KPMG International Cooperative, a Swiss entity. All rights reserved.

This report provides a high level assessment of:<br />

■ Likely regeneration outcomes using a model of regeneration potential developed by KPMG; and<br />

■ Options for funding, financing and procuring a new crossing based on indicative cost and revenue estimates<br />

from early studies of engineering feasibility and traffic impacts.<br />

Applying information currently available to <strong>Kent</strong> <strong>County</strong> <strong>Council</strong>, the funding, financing and procurement<br />

evaluation is developed as follows:<br />

a) Review of the estimated costs and revenues attributable to the New <strong>Lower</strong> <strong>Thames</strong> crossing Project;<br />

b) Consideration of the potential funding sources may be available to fund the scheme; and<br />

c) Consideration of the merits of conventional procurement against a PPP scheme are and what the issues that<br />

will affect that decision will bring.<br />

At the date of this report, the future availability of government funding for transport is uncertain. For the purpose<br />

of this report however, it is assumed that the environment is considered to be similar to that currently in<br />

existence, excepting that it is highly unlikely that significant new sources of grant funding will be available from<br />

UK Central Government for the foreseeable future. However, once the estimated costs of the New <strong>Lower</strong><br />

<strong>Thames</strong> crossing project are fully understood and the political landscape clarified, options for funding may be reexamined<br />

as a part of the Project Business Case. It is important that funding choices reflect a degree of realism<br />

with regard to their potential future availability.<br />

This study has been undertaken as a desk review, with additional information sourced from recent transactions in<br />

the sector that have been advised on by KPMG. It is recommended that this report is updated once transport<br />

policy has been confirmed by the new government, and that KPMG should commence a dialogue with each of<br />

the parties named to extend our mutual understanding of the project and to clarify the opportunities that each<br />

option may offer. As a precursor to formal discussions, however, <strong>Kent</strong> <strong>County</strong> <strong>Council</strong> should develop its<br />

understanding of the costs and revenues associated with the project, leading ultimately the formation of a<br />

Business Case.<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Lower</strong> <strong>Thames</strong> <strong>Crossing</strong> <strong>Kent</strong> <strong>County</strong> <strong>Council</strong> ⏐ 8<br />

@ 2010 KPMG LLP, a UK limited liability partnership, is a subsidiary of KPMG Europe LLP and a member firm of the KPMG<br />

network of independent member firms affiliated with KPMG International Cooperative, a Swiss entity. All rights reserved.

3 Economic assessment framework<br />

3.1 Introduction<br />

This section describes the methodology employed to assess the potential economic impact of crossing options<br />

and data sources used for the economic assessment, including the South Essex Transport and Land use Model<br />

(SETLUM) and the <strong>Kent</strong> <strong>Thames</strong>ide model (KTS). Data from the SETLUM model has been kindly provided by<br />

Essex <strong>County</strong> <strong>Council</strong>.<br />

3.2 Overview of methodology<br />

Transport is one of a number of factors that can affect business location decisions and the competitiveness of<br />

places. <strong>The</strong> transport network makes possible journeys to different kinds of economic opportunities and<br />

determines the ease or difficulty of accessing these opportunities.<br />

To better understand the impacts that the construction of a second <strong>Thames</strong> crossing could have on local<br />

communities and development, <strong>Kent</strong> <strong>County</strong> <strong>Council</strong> and its advisors have developed a methodology for<br />

assessing the impacts of transport interventions on economic output as measured by Gross Value Added (GVA).<br />

This methodology is based on how changes in connectivity to businesses and labour are related to productivity<br />

and business location decisions.<br />

<strong>The</strong> economic approach is based on the identity:<br />

■ GVA (Gross Value Added) = employment * labour productivity<br />

<strong>The</strong> analysis is therefore based on separately modelling impacts of changes in connectivity on employment and<br />

on productivity.<br />

<strong>The</strong> hypothesis that underlies the economic modelling work is that transport connectivity can affect the<br />

attractiveness of different locations as places to do business. This hypothesis has been investigated using data<br />

on transport supply and observed patterns of economic activity. Figure 1 on the next page shows some of the<br />

links between transport change and economic outcomes within an area when transport can affect land use.<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Lower</strong> <strong>Thames</strong> <strong>Crossing</strong> <strong>Kent</strong> <strong>County</strong> <strong>Council</strong> ⏐ 9<br />

@ 2010 KPMG LLP, a UK limited liability partnership, is a subsidiary of KPMG Europe LLP and a member firm of the KPMG<br />

network of independent member firms affiliated with KPMG International Cooperative, a Swiss entity. All rights reserved.

Figure 1: Flow chart of impacts of transport change on GVA<br />

Change in journey<br />

times<br />

Change in<br />

connectivity<br />

Agglomeration<br />

Move to more (or<br />

less) productive<br />

business locations<br />

within study area<br />

Jobs and workers<br />

attracted from<br />

outside study area<br />

Change in<br />

productivity<br />

Change in workplace<br />

employment<br />

Change in GVA<br />

<strong>The</strong> modelling approach deduces changes in business location decisions and agglomeration based on changes<br />

in measures of connectivity. Figure 1 above shows that changes in productivity can come about from changes in<br />

business location decisions as businesses move between areas which support different levels of productivity.<br />

<strong>The</strong> key relationships used for forecasting have been derived from a cross-sectional statistical analysis of the<br />

links between measures of connectivity and the economic outcomes found in different local areas across the<br />

study area.<br />

3.3 Measuring connectivity<br />

Much of the approach to linking transport supply and economic performance is based on measures of<br />

connectivity. For a particular area, a measure of connectivity captures how many economic opportunities there<br />

are within a reasonable journey time of that area. This presents a number of challenges:<br />

■ What represents an ‘opportunity’?<br />

■ How should journey time and different journey opportunities (for example by different modes) be captured?<br />

■ What represents a reasonable journey time? For example, how important is it for a business to be able to<br />

access employees with 20 minutes of commuting time, or 40 minutes, or an hour?<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Lower</strong> <strong>Thames</strong> <strong>Crossing</strong> <strong>Kent</strong> <strong>County</strong> <strong>Council</strong> ⏐ 10<br />

@ 2010 KPMG LLP, a UK limited liability partnership, is a subsidiary of KPMG Europe LLP and a member firm of the KPMG<br />

network of independent member firms affiliated with KPMG International Cooperative, a Swiss entity. All rights reserved.

3.3.1 Opportunities and transport modes<br />

<strong>The</strong> model has been developed to assess how different levels of connectivity affect businesses. Opportunities<br />

have therefore been divided into two groups: access to labour and access to other businesses. <strong>The</strong> segmentation<br />

enables the analysis to separately appraise connectivity to labour and to other businesses.<br />

Socio-economic data has been used to provide the measures of ‘opportunities’ as follows:<br />

■ Labour markets: measured by working age population in origin zone; and<br />

■ Business to business markets: measured by workplace jobs in origin zone<br />

3.3.2 Measuring the difficulty of travel<br />

To capture the combined barriers of journey time and fare/cost, the difficulty of making a journey is captured<br />

using a generalised cost including both of these elements. Generalised times are measured in minutes and<br />

include financial costs by converting them into minutes using values of time taken from WebTAG.<br />

Generalised time (including financial costs) has been sourced from the KTS and SETLUM models. Commuting<br />

journeys are represented as journeys in the AM peak (7am – 10am). Business to business journeys are assumed<br />

to take place during the inter-peak hours of 10am and 4pm.<br />

3.3.3 Assessing reasonable journey times<br />

Market sizes reflect the number of people willing to make a journey to a particular place for a particular purpose.<br />

As the difficulty of a journey increases, the number of people willing to make the journey declines.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re are a number of options available for representing this relationship: a simple boundary (e.g. how many<br />

people within one hour?); a simple linear decay function; a mathematically defined decay function such as an<br />

exponential decay function; or a relationship based on observed travel behaviour. In this analysis a relationship<br />

has been developed for each market segment which reflects the behaviour embodied in the demand data held<br />

within the transport models which is based on observed travel patterns.<br />

Demand and generalised cost data in the model has been used to generate generalised time decay curves or<br />

deterrence functions. For car commuting for example, this represents the share of people that currently accept a<br />

commute of different levels of generalised cost (e.g. Y% of people currently accept a commute of less than or<br />

equal to X minutes). A similar decay curve has been calculated for the business to business market segment for<br />

all journeys destinating within the core study area.<br />

Demand data for Public Transport was insufficient in both SETLUM and KTS to provide a smooth function<br />

describing how travel demand changes with generalised cost of travel. <strong>The</strong>refore a simple linear function was<br />

developed to assess Public Transport labour and business market catchments.<br />

Higher demand for car traffic enabled decay curves to be created based on car travel behaviour. <strong>The</strong> KTS model<br />

has a more finely grained zoning system and data that is more disaggregate than the SETLUM model, which<br />

means demand for different lengths of trips is well represented. Car decay curves were therefore produced using<br />

KTS generalised cost and demand data. <strong>The</strong> KTS and linear deterrence functions for car and Public Transport<br />

are outlined in Figure 2 overleaf.<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Lower</strong> <strong>Thames</strong> <strong>Crossing</strong> <strong>Kent</strong> <strong>County</strong> <strong>Council</strong> ⏐ 11<br />

@ 2010 KPMG LLP, a UK limited liability partnership, is a subsidiary of KPMG Europe LLP and a member firm of the KPMG<br />

network of independent member firms affiliated with KPMG International Cooperative, a Swiss entity. All rights reserved.

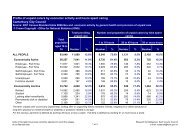

Figure 2: Willingness to travel by mode and journey purpose<br />

Percentage willing to travel<br />

100%<br />

90%<br />

80%<br />

70%<br />

60%<br />

50%<br />

40%<br />

30%<br />

20%<br />

10%<br />

0%<br />

0<br />

50<br />

100<br />

150<br />

200<br />

250<br />

300<br />

350<br />

<strong>The</strong> deterrence functions represent the pattern of behaviour of car commuters and car business travellers, using<br />

KTS for car travel and a linear function for public transport travel. It was assumed that willingness to travel of<br />

public transport users gradually falls as generalised travel time increases, to reach 0% for 1,000 minutes of<br />

generalised time. For car commute the decay curve shows that approximately 60% of car commuters accept a<br />

total daily commute of up to 150 generalised minutes. This reduces to just 10% for a daily commute of 350<br />

generalised minutes. For car business to business trips willingness to travel drops off at around 200 minutes to<br />

reach 0% at around 450 generalised minutes of travel.<br />

It has been assumed that the deterrence functions remain constant over time. If fuel, vehicle operating costs and<br />

fares rise in line with average income, this would be consistent with people spending the same share of their time<br />

and money on travel in future years.<br />

3.3.4 Calculating overall market sizes<br />

400<br />

Generalised cost (minutes)<br />

450<br />

500<br />

550<br />

600<br />

650<br />

700<br />

750<br />

800<br />

850<br />

900<br />

950<br />

1,000<br />

Car commute Car b2b PT commute and B2B<br />

<strong>The</strong> effective labour market for any of core study areas zone is calculated as the sum of people of working age in<br />

all origin zones willing to travel to that destination for work. <strong>The</strong> effective business to business markets are<br />

similarly calculated as the sum of all workplace jobs that can be reached from an origin using a deterrence<br />

function and value of time derived from observed business travel pattern.<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Lower</strong> <strong>Thames</strong> <strong>Crossing</strong> <strong>Kent</strong> <strong>County</strong> <strong>Council</strong> ⏐ 12<br />

@ 2010 KPMG LLP, a UK limited liability partnership, is a subsidiary of KPMG Europe LLP and a member firm of the KPMG<br />

network of independent member firms affiliated with KPMG International Cooperative, a Swiss entity. All rights reserved.

Figure 3: Illustrative example of contribution of origin zone to effective labour market in destination zone<br />

B<br />

A<br />

y% willing<br />

to travel<br />

z working<br />

age<br />

residents<br />

x mins<br />

y * z people in effective<br />

labour market for zone A<br />

from zone B<br />

From the generalised cost of a journey to a particular zone it was then possible to use the corresponding decay<br />

curve to assess the share of people willing to travel to that location from every other zone. Summing the share of<br />

all people willing to travel from all other zones to the destination provides the measure of connectivity for that<br />

market segment.<br />

More formally:<br />

j<br />

MarketSize<br />

=<br />

∑<br />

i<br />

Π<br />

ij<br />

Ο<br />

i<br />

Where i represents the origin and j the destination and where:<br />

∏ij =<br />

Oi =<br />

Share of people willing to accept generalised cost based on the journey time between i and j; and<br />

Opportunities in the origin zone i<br />

3.4 Data sources<br />

<strong>The</strong> economic analysis requires a detailed examination of the levels of connectivity offered to local areas in North<br />

<strong>Kent</strong> and South Essex. This requires geographically disaggregate representations of journey options and the<br />

difficulty of travel for journeys north of the river, south of the river and across the river. <strong>The</strong>re are various<br />

transport models covering the areas to the north and the south of the existing Dartford crossing and potential new<br />

crossing points nearby. However none of them adequately capture local travel options on both sides of the river.<br />

This is mainly because the river currently represents a significant barrier to movement and the transport models<br />

developed have focussed on one side and only captured a limited representation of the other side.<br />

<strong>The</strong> analysis undertaken for this project has therefore been based on combining datasets from different transport<br />

models with different characteristics and should therefore be treated with caution.<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Lower</strong> <strong>Thames</strong> <strong>Crossing</strong> <strong>Kent</strong> <strong>County</strong> <strong>Council</strong> ⏐ 13<br />

@ 2010 KPMG LLP, a UK limited liability partnership, is a subsidiary of KPMG Europe LLP and a member firm of the KPMG<br />

network of independent member firms affiliated with KPMG International Cooperative, a Swiss entity. All rights reserved.

3.4.1 Generalised cost<br />

Generalised costs have been sourced from the South Essex Transport and Land Use Model (SETLUM) and from<br />

the <strong>Kent</strong> <strong>Thames</strong>ide Model (KTS). Data and assistance on transport models was provided by Essex and <strong>Kent</strong><br />

<strong>County</strong> <strong>Council</strong>s.<br />

SETLUM contains 163 model zones. 110 of these are in Basildon, Thurrock, Castle Point, Rochford and<br />

Southend-on-Sea in Essex, 6 of these are in <strong>Kent</strong> and the remaining 47 are further afield. Matrices of generalised<br />

cost have been sourced from SETLUM for the 2001 base year for car and public transport trips for AM peak<br />

commute trips and interpeak business to business trips. <strong>The</strong> generalised costs include time costs, perceived<br />

inconvenience (for example public transport interchanges) and financial elements of costs such as vehicle<br />

operating costs, tolls and public transport fares. Where more than one public transport mode offers a viable<br />

alternative, the lowest generalised cost or ‘best path’ option has been selected.<br />

Figure 4: SETLUM model zone centroids in <strong>Thames</strong> Gateway area<br />

Romford<br />

Essex<br />

London<br />

Woolwich<br />

Grays<br />

Dartford<br />

Gravesend<br />

<strong>Kent</strong><br />

Gllingham<br />

KTS contains 590 model zones. <strong>The</strong> vast majority of these zones represent areas in <strong>Kent</strong> <strong>Thames</strong>ide with only a<br />

few model zones representing local areas in Essex. This is shown in Figure 5 overleaf.<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Lower</strong> <strong>Thames</strong> <strong>Crossing</strong> <strong>Kent</strong> <strong>County</strong> <strong>Council</strong> ⏐ 14<br />

@ 2010 KPMG LLP, a UK limited liability partnership, is a subsidiary of KPMG Europe LLP and a member firm of the KPMG<br />

network of independent member firms affiliated with KPMG International Cooperative, a Swiss entity. All rights reserved.

Figure 5: KTS model zone centroids in <strong>Thames</strong> Gateway area<br />

Romford<br />

Essex<br />

London<br />

Woolwich<br />

Grays<br />

Dartford<br />

Gravesend<br />

<strong>Kent</strong><br />

Gllingham<br />

Cost data from these two models has been merged to create a representation of a disaggregate matrix of<br />

journeys with origins and destinations represented at ward level on both sides of the <strong>Thames</strong> in the districts of<br />

Basildon, Brentwood, Castle Point, Dartford, Gravesham, Medway, Rochford, Southend-on-Sea, Swale and<br />

Thurrock. Further afield, zones are represented using larger administrative areas such as districts/unitary<br />

authorities (e.g. London boroughs), counties (e.g. Suffolk) and regions (e.g. the South West). <strong>The</strong> zoning system<br />

is therefore consistent with UK administrative geography. This zoning system is shown in Figure 6 overleaf.<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Lower</strong> <strong>Thames</strong> <strong>Crossing</strong> <strong>Kent</strong> <strong>County</strong> <strong>Council</strong> ⏐ 15<br />

@ 2010 KPMG LLP, a UK limited liability partnership, is a subsidiary of KPMG Europe LLP and a member firm of the KPMG<br />

network of independent member firms affiliated with KPMG International Cooperative, a Swiss entity. All rights reserved.

Figure 6: Centroids of geographical zoning system used for analysis<br />

Romford<br />

Essex<br />

London<br />

Woolwich<br />

Grays<br />

Dartford<br />

Gravesend<br />

<strong>Kent</strong><br />

Gllingham<br />

<strong>The</strong> core model areas consist of the districts of Medway, Dartford, Gravesham and Swale within <strong>Kent</strong> and of the<br />

districts of Southend-on-Sea, Thurrock, Basildon, Brentwood, Castle Point and Rochford in Essex. This area is<br />

covered at ward level in the modelling. A hinterland of zones has also been defined to enable the different labour<br />

markets and business to business trip catchments of these core zones to be estimated.<br />

To create the generalised journey time dataset for this model zoning, the following process was applied:<br />

1. Calculate the closest zone centroid in KTS to each model zone centroid used in the analysis;<br />

2. Create model zone to zone generalised cost matrices based on the closest KTS zone centroid to the model<br />

origin centroid and the closest KTS zone centroid to the model destination centroid;<br />

3. Repeat for SETLUM data to create the model zone matrices derived from the SETLUM model;<br />

4. Identify flows which use the existing bridge;<br />

5. For flows that are south of the river and do not use the bridge, use the KTS data as the best proxy for<br />

generalised cost;<br />

6. For flows that are north of the river and do not use the bridge, use the SETLUM data as the best proxy for<br />

generalised cost;<br />

7. For flows that travel south across the bridge, use the SETLUM cost from origin to the bridge plus the KTS<br />

cost from the bridge to the destination, plus a representation of bridge tolls; and<br />

8. For flows that travel north across the bridge, use the KTS cost from origin to the bridge plus the SETLUM cost<br />

from the bridge to the destination, plus a representation of bridge tolls.<br />

This approach provides a matrix of costs for travel on the north side of the river, the south side of the river and for<br />

cross river trips. However, for cross river trips the cost data is a hybrid from different sources and data for trips on<br />

the south side of the river is from a different source from trips in the north. <strong>The</strong> key similarities and differences<br />

between the models are as follows:<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Lower</strong> <strong>Thames</strong> <strong>Crossing</strong> <strong>Kent</strong> <strong>County</strong> <strong>Council</strong> ⏐ 16<br />

@ 2010 KPMG LLP, a UK limited liability partnership, is a subsidiary of KPMG Europe LLP and a member firm of the KPMG<br />

network of independent member firms affiliated with KPMG International Cooperative, a Swiss entity. All rights reserved.

■ Both models share definitions of time periods, so for example, peak journeys represent the average hour<br />

between 7AM and 10AM.<br />

■ <strong>The</strong> SETLUM data represents 2001 while the KTS data represents 2005<br />

■ All times and costs have been expressed in 2001 prices and values<br />

Using this hybrid approach is unavoidable given the study timescales and budgets. <strong>The</strong> time and cost<br />

components of generalised cost have been made consistent as far as possible but nevertheless represent<br />

different underlying model assumptions. Figure 7 below shows the relationships between the car commuting<br />

generalised costs in KTS and SETLUM for comparable origins and destinations.<br />

Figure 7: Comparison of KTS and SETLUM car generalised costs, 2001 prices<br />

Generalised cost (pence)<br />

2,000<br />

1,800<br />

y = 1.7679x<br />

KTS<br />

1,600<br />

1,400<br />

1,200<br />

1,000<br />

800<br />

600<br />

400<br />

200<br />

Source: SETLUM and KTS models<br />

0<br />

0 200 400 600 800 1,000 1,200<br />

<strong>The</strong> comparable origins and destinations selected are based on cross river origin to destination trips where the<br />

centroids of both zones lie within 1km of each other. For these trips KTS shows consistently higher generalised<br />

costs than SETLUM. <strong>The</strong> best fit line shows that the KTS generalised costs is some 1.8 times higher than the<br />

SETLUM cost, although the two are closely related. More detailed analysis of differences between the models is<br />

presented in Appendix A. We recommend that a suitable transport model with suitable geographical<br />

representation to the north and south of the <strong>Thames</strong> is developed if the analysis of <strong>Lower</strong> <strong>Thames</strong> crossing<br />

options is to be progressed further.<br />

Journey times and costs have all been measured in pence using values of time from WebTAG to represent<br />

commuting and business to business travellers. <strong>The</strong> costs are taken to be the best available representation of<br />

generalised costs consistent with the most recent socioeconomic data available given the journey time and cost<br />

data available.<br />

3.4.2 Socioeconomic data<br />

SETLUM<br />

Population data has been sourced for each model zone from the Office for National Statistics experimental local<br />

area population statistics by quinary group. To represent labour markets, working age population data has been<br />

constructed using the quinary groups between 20-24 and 60-64 years old plus four fifths of the quinary age group<br />

15-19. <strong>The</strong> latest available data from the Office for National Statistics is for 2007.<br />

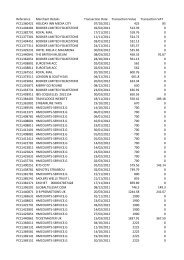

Workplace employment data by business sector has been collected from the Annual Business Inquiry. <strong>The</strong> latest<br />

available data is for 2008.<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Lower</strong> <strong>Thames</strong> <strong>Crossing</strong> <strong>Kent</strong> <strong>County</strong> <strong>Council</strong> ⏐ 17<br />

@ 2010 KPMG LLP, a UK limited liability partnership, is a subsidiary of KPMG Europe LLP and a member firm of the KPMG<br />

network of independent member firms affiliated with KPMG International Cooperative, a Swiss entity. All rights reserved.

Data for 2010 has been constructed by applying the growth rates for the appropriate local authority sourced from<br />

the DfT’s National Trip End Model (NTEM) version 5.4 which provides forecast data for transport planning<br />

purposes. Data for the 2026 forecast year has been similarly constructed based on the NTEM datasets extracted<br />

using the TEMPRO software.<br />

3.4.3 Demand<br />

Demand data has been sourced from both the <strong>Kent</strong> <strong>Thames</strong>ide Model and the SETLUM model. <strong>The</strong>se data sets<br />

have been collected for commuting in the AM peak and business travel in the interpeak. For both models, this<br />

data was split by mode and by journey purpose. SETLUM data was collected for 2001 (the model base year) and<br />

for 2021, and KTS data for 2005 (again, the model base year) and 2025.<br />

<strong>The</strong> demand data has only been used to determine the relationship between demand and the generalised cost of<br />

travel for the different model segments and for assessing the generalised cost deterrence functions used in the<br />

modelling (see for example Figure 2).<br />

3.5 Assessing business location choice<br />

<strong>The</strong> relationship between employment density and connectivity was assessed using econometric techniques and<br />

other evidence for business location decision making.<br />

<strong>The</strong> relationships between connectivity and employment density have been investigated using linear regression<br />

formulations. This analysis has taken the form:<br />

Log(employment density) = f (ln(connectivity measures), ln(other variables))<br />

Where zones both north and south of the river have been considered in the same equation, a flag has been<br />

introduced in the regression analysis to distinguish between these. This allows the differences in connectivity due<br />

to model differences to be mitigated to some extent. However, given that the data has been drawn from two<br />

separate models, we have also considered equations that look separately at zones to the north of the river and<br />

zones to the south of the river.<br />

Two connectivity measures were tested: access to labour by road, and access to other business by road. Access<br />

to labour by public transport and access to other businesses by public transport were excluded from the analysis<br />

due to the dominance of car travel which makes understanding the importance of public transport connectivity<br />

more complex. <strong>The</strong> complexity of integrating public transport data from the KTS and SETLUM models also<br />

makes the analysis of public transport catchments less reliable.<br />

<strong>The</strong> only other variable considered as a driver of business location choice was proximity to the <strong>Thames</strong> ports<br />

(and historic <strong>Thames</strong> ports). This reflects the current and historic importance of the <strong>Thames</strong> in providing<br />

connectivity to markets by river and sea.<br />

Cross sectional analysis alone cannot determine causation. To determine the extent to which any links are causal<br />

requires analysis of time series data and analysis of lead and lag relationships. Such data is not available.<br />

Without a time series analysis causation must be judged based on the underlying theory. <strong>The</strong>re are reasons why<br />

one would expect causation to run in both directions. Businesses are likely to move to places where they have<br />

locational advantages which could come from better transport connectivity. However, high levels of employment<br />

are also likely to lead to higher levels of transport connectivity as infrastructure provision follows demand. In this<br />

analysis we present the results of what would occur if the statistical relationships did represent a causal<br />

relationship between changes in transport connectivity and changes in employment density. This is the same as<br />

the approach taken to measuring agglomeration by the Department for Transport.<br />

<strong>The</strong> relationships between car connectivity to businesses and labour and employment density were assessed.<br />

<strong>The</strong> model draws data from both the KTS and SETLUM models to estimate hybrid journey times. However, as<br />

there are differences between these models, we have separately conducted statistical analysis for zones north of<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Lower</strong> <strong>Thames</strong> <strong>Crossing</strong> <strong>Kent</strong> <strong>County</strong> <strong>Council</strong> ⏐ 18<br />

@ 2010 KPMG LLP, a UK limited liability partnership, is a subsidiary of KPMG Europe LLP and a member firm of the KPMG<br />

network of independent member firms affiliated with KPMG International Cooperative, a Swiss entity. All rights reserved.

the river, zones south of the river and for all of the hybrid model zones taken together. <strong>The</strong>se different model<br />

formulations and datasets provide different findings for the strength of relationships between business location<br />

and car connectivity.<br />

Initial statistical tests found that business to business connectivity dominated the relationship, therefore labour<br />

market/commute connectivity was taken out of subsequent regressions tests. <strong>The</strong> results of the statistical<br />

analysis showed a coefficient of 0.76 for zones north of the river and 0.65 when assessing all zones together<br />

using the hybrid model . However, no statistically significant results were obtained for zones to the south of the<br />

river.<br />

In order to take into account variations in generalised time between KTS and SETLUM, an alternative model<br />

formulation was designed to treat connectivity levels on different sides of the river in a different way. <strong>The</strong><br />

alternative formulation returns an analogous coefficient of 0.46. It therefore does appear that some positive<br />

relationships exist between car connectivity and employment density, although a range of values have been used<br />

for forecasting. Further information on the regression analysis is provided in Appendix B.<br />

Different scenarios have been considered, according to the regression results explained above. <strong>The</strong> fixed land<br />

use estimate reflects the fact that in some model formulations, car connectivity does not show a statistically<br />

significant relationship with employment density. For this scenario it is assumed the distribution and quantum of<br />

employment remains unchanged. GVA impacts will therefore only be attributable to changes in productivity levels<br />

arising from agglomeration economies. <strong>The</strong> parameters used in modelling are shown in Table 1 below.<br />

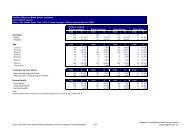

Table 1: Model parameters<br />

Car connectivity to labour<br />

Car business to business connectivity<br />

markets<br />

Fixed land-use formulation 0.00 0.00<br />

Hybrid model formulation 0.65 0.00<br />

Alternative model formulation 0.46 0.00<br />

Note:<br />

In all model formulations, access to labour markets has been assumed to have a parameter of zero and hence not to play a role. This is because the statistical<br />

analysis has been unable to detect such a relationship. This may be partly because the business to business connectivity measures and the labour market<br />

connectivity measures are closely related and the statistical analysis has been unable to separate their impact.<br />

3.6 Considering relative connectivity and business mobility<br />

<strong>The</strong> cross sectional quantitative analysis provides evidence of the correlation between business location and<br />

connectivity. However, it is not true to say that a change in connectivity will simply result in a change in the<br />

number of workplace jobs or employment density.<br />

<strong>The</strong> analysis shows how connectivity affects the relative attractiveness of the different sites studied. Hence,<br />

changes in connectivity could either lead to redistribution of existing businesses or could result in businesses<br />

being attracted to the study area or discouraged from moving there. Hence applying the equation described<br />

above to forecast employment will tend to produce unconstrained employment forecasts that assume all change<br />

is due to change into or out of the study area and do not allow for this redistribution. <strong>The</strong> challenge then is to<br />

estimate the extent to which change in connectivity could lead to internal redistribution within the study area or to<br />

changes in employment to or from outside the core study area.<br />

To estimate the change in employment within the core study area, the degree of business mobility between city<br />

regions was assessed. Unfortunately, suitable dynamic studies of business mobility and relocation decisions do<br />

not exist. Instead, mobility was assessed by looking at the geographical distribution of businesses, and the<br />

proportion of footloose businesses – hypothesized as those that could take advantage of changes in the<br />

connectivity offered by different locations. Footloose businesses were deemed to be those that were not tied to<br />

serving a local market, but that served an inter-regional or international market and could relocate to take<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Lower</strong> <strong>Thames</strong> <strong>Crossing</strong> <strong>Kent</strong> <strong>County</strong> <strong>Council</strong> ⏐ 19<br />

@ 2010 KPMG LLP, a UK limited liability partnership, is a subsidiary of KPMG Europe LLP and a member firm of the KPMG<br />

network of independent member firms affiliated with KPMG International Cooperative, a Swiss entity. All rights reserved.

advantage of changes in locational factors. Businesses serving local markets (such as grocery shops, hair<br />

dressers etc.) tend to be geographically tied to local markets.<br />