Malaysia's capital of cronyism - Rengah Sarawak

Malaysia's capital of cronyism - Rengah Sarawak

Malaysia's capital of cronyism - Rengah Sarawak

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

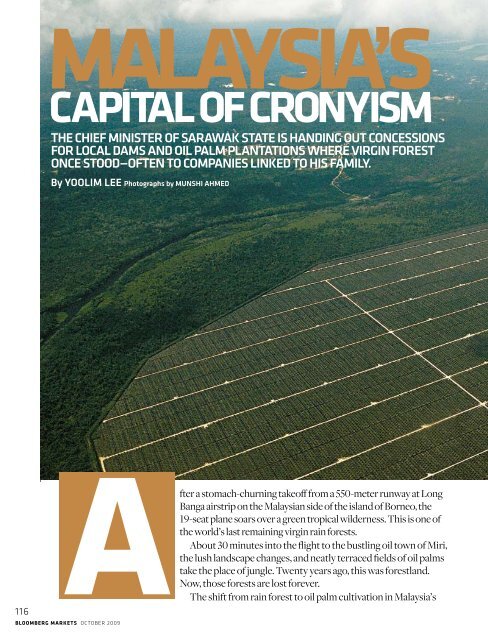

Malaysia’s<br />

Capital <strong>of</strong> <strong>cronyism</strong><br />

The chief minister <strong>of</strong> <strong>Sarawak</strong> state is Handing out concessions<br />

for local dams and oil palm plantations where virgin forest<br />

once stood—<strong>of</strong>ten to companies linked to his family.<br />

By Yoolim Lee Photographs by MUNSHI AHMED<br />

116<br />

fter a stomach-churning take<strong>of</strong>f from a 550-meter runway at Long<br />

Banga airstrip on the Malaysian side <strong>of</strong> the island <strong>of</strong> Borneo, the<br />

19-seat plane soars over a green tropical wilderness. This is one <strong>of</strong><br />

the world’s last remaining virgin rain forests.<br />

About 30 minutes into the flight to the bustling oil town <strong>of</strong> Miri,<br />

the lush landscape changes, and neatly terraced fields <strong>of</strong> oil palms<br />

take the place <strong>of</strong> jungle. Twenty years ago, this was forestland.<br />

Now, those forests are lost forever.<br />

AThe shift from rain forest to oil palm cultivation in Malaysia’s<br />

bloomberg markets October 2009

<strong>Sarawak</strong> state highlights the struggle taking place between<br />

forces favoring economic development, led by <strong>Sarawak</strong> state’s<br />

chief minister, Abdul Taib Mahmud, and those who want to<br />

conserve the rain forest and the ways <strong>of</strong> life it supports. During<br />

Taib’s 28-year rule, his government has handed out concessions<br />

for logging and supported the federal government’s<br />

megaprojects, including the largest hydropower site in the<br />

country and, most recently, oil palm plantations. The projects<br />

are rolling back the frontiers <strong>of</strong> Borneo’s rain forest, home to<br />

nomadic people and rare wildlife such as orangutans and proboscis<br />

monkeys. At least four prominent <strong>Sarawak</strong> companies<br />

that have received contracts or concessions<br />

have ties to Taib or his family.<br />

The government <strong>of</strong> Malaysia plans to<br />

transform the country into a developed<br />

nation by 2020 through a series <strong>of</strong> projects<br />

covering everything from electric<br />

The landscape <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Sarawak</strong> is<br />

changing from<br />

rain forest into<br />

oil palm<br />

plantations.<br />

power generation to education. The country’s gross domestic<br />

product, which has been growing at an average 6.7 percent annual<br />

pace since 1970, shrank 6.2 percent in the first quarter.<br />

In <strong>Sarawak</strong>, Taib’s government is following its own development<br />

plans that call for doubling the state’s GDP to 150 billion<br />

117<br />

October 2009 bloomberg markets

118<br />

ringgit ($42 billion) by 2020. <strong>Sarawak</strong> Energy Bhd., which is 65<br />

percent owned by the state government, said in July 2007 it<br />

plans to build six power plants, including hydropower plants and<br />

coal-fired plants. The state government also wants to expand the<br />

acreage in <strong>Sarawak</strong> devoted to oil palms to 1 million hectares<br />

(2.5 million acres) by 2010, from 744,000 at the end <strong>of</strong> 2008,<br />

according to <strong>Sarawak</strong>’s Ministry <strong>of</strong> Land Development. Companies<br />

that formerly chopped down hardwood trees and exported<br />

the timber are now moving into palm plantations. Meanwhile,<br />

many <strong>of</strong> the ethnic groups who have traditionally lived from the<br />

land in <strong>Sarawak</strong>—known as Dayaks—have filed lawsuits that aim<br />

to block some projects and seek better compensation.<br />

<strong>Sarawak</strong>’s chief minister is also<br />

finance minister and planning and<br />

resources management minister—which<br />

gives him the power to dispense land,<br />

forestry and palm oil concessions.<br />

<strong>Sarawak</strong>’s ambitions could be hindered by a lack <strong>of</strong><br />

good governance, which would shut out overseas investors,<br />

says Steve Waygood, head <strong>of</strong> sustainable and<br />

responsible investment research at Aviva Investors in<br />

London, which manages more than $3 billion in sustainable<br />

assets. “Even just the perception <strong>of</strong> corruption can lead to<br />

restricted inflows <strong>of</strong> <strong>capital</strong> from the global investment community<br />

into emerging markets such as <strong>Sarawak</strong>,” says Waygood,<br />

who wrote about reputational risk in a 2006 book, Capital<br />

Market Campaigning (Risk Books). “The largest and most<br />

responsible financial institutions are very careful to avoid funding<br />

unsustainable developments,” he says.<br />

Unilever NV, which buys 1.5 million tons <strong>of</strong> palm oil a<br />

year—4 percent <strong>of</strong> the world’s supply—for use in products<br />

such as Dove soap and Flora margarine, announced in May<br />

that it would buy only from sustainable sources. “Unilever<br />

Fading Forest<br />

Logging, oil palm plantations and mega development<br />

projects are fast rolling back <strong>Sarawak</strong>’s frontiers.<br />

VIETNAM<br />

South China Sea<br />

BRUNEI<br />

M A L A Y S I A<br />

SINGAPORE<br />

BORNEO<br />

I N D O N E S I A<br />

Kuching<br />

Kampung Rejoi<br />

Kampung Lebor<br />

Source: Digital Wisdom<br />

bloomberg markets October 2009<br />

Miri<br />

SARAWAK<br />

Long Kerong<br />

Baram River<br />

Long Banga airstrip<br />

Bakun Dam<br />

does not source any palm oil directly from <strong>Sarawak</strong>,” says Jan<br />

Kees Vis, Unilever’s director <strong>of</strong> sustainable agriculture. “We<br />

buy from plantation companies and traders located elsewhere.”<br />

He says Unilever has committed by 2015 to buy all <strong>of</strong><br />

its palm oil from sources certified by the Roundtable on Sustainable<br />

Palm Oil, a group representing palm oil producers,<br />

consumers and nongovernmental organizations that seeks to<br />

establish standards for sustainably produced palm oil. Malaysia<br />

is a member <strong>of</strong> the RSPO.<br />

About 35 percent <strong>of</strong> the world’s cooking oil comes from<br />

palm—more than any other plant, according to the U.S. Department<br />

<strong>of</strong> Agriculture. And 90 percent <strong>of</strong> the world’s palm<br />

oil comes from Malaysia and neighboring Indonesia. The oil is<br />

an ingredient used in everything from Skittles candy to Palmolive<br />

soap to some kinds <strong>of</strong> biodiesel fuel. Palm oil futures have<br />

climbed 45 percent this year as <strong>of</strong> Aug. 10 on concern that dry<br />

weather caused by El Nino may reduce<br />

output. Crude oil prices rose to a fiveweek<br />

high <strong>of</strong> $72.84 a barrel, spurring<br />

demand for biodiesel.<br />

Malaysia lost 6.6 percent <strong>of</strong> its forest<br />

cover from 1990 to 2005, or 1.49 million<br />

hectares, the most-recent data available<br />

from the United Nations Food and Agriculture<br />

Organization show. That’s an area<br />

equivalent to the state <strong>of</strong> Connecticut.<br />

Neighboring Indonesia lost forestland at<br />

the fastest annual rate among the world’s<br />

44 forest nations from 2000 to 2005, Amsterdam-based<br />

Greenpeace says.<br />

“Palm oil is the new green gold after<br />

timber,” says Mark Bujang, executive director<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Borneo Resources Institute<br />

in Miri, a city <strong>of</strong> about 230,000 people in<br />

<strong>Sarawak</strong>. “It has become the most destructive<br />

force after three decades <strong>of</strong> unsustainable<br />

logging.”<br />

While Malaysia’s palm oil exports have<br />

more than doubled to a record 46 billion<br />

ringgit in 2008 from 2006, according to<br />

the country’s central bank, the gain has<br />

come at a price. Development projects<br />

and palm plantations have displaced<br />

thousands <strong>of</strong> people, some <strong>of</strong> whom have<br />

lived for centuries by fishing, hunting and<br />

farming in the jungle. Almost 200 lawsuits<br />

are pending in the <strong>Sarawak</strong> courts<br />

relating to claims by Dayak people on<br />

lands being used for oil palms and logging,<br />

according to Baru Bian, a land rights<br />

lawyer representing many <strong>of</strong> the claimants. A<br />

handful <strong>of</strong> activists have been found dead<br />

under mysterious circumstances or disappeared,<br />

including Swiss environmental

activist Bruno Manser, who vanished in the jungle in 2000.<br />

Cutting down rain forests to cultivate palms in <strong>Sarawak</strong> has<br />

consequences far beyond Malaysia, says Janet Larsen, director<br />

<strong>of</strong> research at the Washington-based Earth Policy Institute. The<br />

forests that are being destroyed help modulate the climate because<br />

they remove vast stores <strong>of</strong> carbon from the atmosphere.<br />

Chopping down the trees ends up releasing greenhouse gases.<br />

“These last remaining forests are the lungs <strong>of</strong> the planet,” Larsen<br />

says. “It affects us all.”<br />

Chief Minister Taib, 73, has multiple<br />

roles in <strong>Sarawak</strong>. He’s also the state’s finance<br />

minister and its planning and resources<br />

management minister—a role<br />

that gives him the power to dispense land,<br />

forestry and palm oil concessions as well<br />

as the power to approve infrastructure<br />

Logging, right, is<br />

giving way to palm<br />

cultivation, below.<br />

The <strong>Sarawak</strong> state<br />

wants to double palm<br />

oil plantation land by<br />

2010 from 2006.<br />

119<br />

October 2009 bloomberg markets

120<br />

projects. Until last year, Taib held the additional role <strong>of</strong> chairman<br />

<strong>of</strong> the <strong>Sarawak</strong> Timber Industry Development Corp., which<br />

fosters wood-based industries in the state.<br />

Anwar ibrahim, the former Malaysian finance minister<br />

who’s the head <strong>of</strong> the country’s opposition alliance,<br />

sees parallels between Taib’s rule and those <strong>of</strong> other<br />

long-standing leaders in Southeast Asia, such as former<br />

Indonesian President Suharto and former Philippine leader Ferdinand<br />

Marcos. “It’s an authoritarian style <strong>of</strong> governance to protect<br />

their turf and their families,” says Anwar, who was fired as deputy<br />

prime minister by then Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad in<br />

1998 and jailed on charges <strong>of</strong> having homosexual sex and abusing<br />

power. The sodomy conviction was overturned in 2004.<br />

Sim Kwang Yang, an opposition member <strong>of</strong> parliament for<br />

<strong>Sarawak</strong>’s <strong>capital</strong> city <strong>of</strong> Kuching from 1982 to 1995, agrees<br />

with Anwar’s assessment. “It is crony <strong>capital</strong>ism driven by<br />

greed without any regard for the people,” he says.<br />

Taib’s adult children and his late wife, Lejla, together owned<br />

more than 29.3 percent <strong>of</strong> Cahya Mata <strong>Sarawak</strong> Bhd., the<br />

state’s largest industrial group, with 40 companies involved in<br />

bloomberg markets October 2009<br />

construction, property development, road maintenance, trading<br />

and financial services, according to the company’s 2008 annual<br />

report. Local residents jokingly say that the company’s<br />

initials, CMS, stand for “Chief Minister and Sons.” In total,<br />

CMS has won about 1.3 billion ringgit worth <strong>of</strong> projects from<br />

the state and the federal government since the beginning <strong>of</strong><br />

2005, according to the firm’s stock exchange filings.<br />

Taib declined to comment for this article. In an interview he<br />

gave to Malaysia’s state news agency, Bernama, on Jan. 13,<br />

2001, Taib said CMS’s ties to him had nothing to do with its<br />

winning government jobs. “I am not involved in the award <strong>of</strong><br />

contracts,” he said. “No politician in <strong>Sarawak</strong> is involved in the<br />

award <strong>of</strong> contracts.” He told Bernama he<br />

doesn’t ask for special treatment <strong>of</strong> his<br />

Chief Minister Taib,<br />

right, pictured here sons. “I never ask anybody to do any favors,”<br />

he said.<br />

with former Prime<br />

Minister Abdullah<br />

Mahmud Abu Bekir Taib, the elder <strong>of</strong><br />

Badawi, looks at the<br />

model <strong>of</strong> an energy Taib’s two sons, is CMS’s deputy chairman<br />

and owns 8.92 percent <strong>of</strong> the firm,<br />

project in <strong>Sarawak</strong>.<br />

The Bakun Dam,<br />

according to the annual report. Sulaiman<br />

Abdul Rahman Taib, the younger<br />

under construction,<br />

will submerge an<br />

area equivalent to son and CMS’s chairman until 2008,<br />

the size <strong>of</strong> Singapore.<br />

holds an 8.94 percent stake. Taib’s two<br />

daughters and his son-in-law are also<br />

listed in the annual report as “substantial shareholders.”<br />

Taib, a Muslim who belongs to the Melanau group—one <strong>of</strong><br />

about 27 different ethnic groups in <strong>Sarawak</strong>—entered politics<br />

at the age <strong>of</strong> 27 after graduating from the University <strong>of</strong> Adelaide<br />

in Australia with a law degree in 1960. He held various ministerial<br />

positions in <strong>Sarawak</strong> and Malaysia before taking over in<br />

1981 as the chief minister from his uncle, Abdul Rahman<br />

Yaakub. Rahman, now 81, ruled <strong>Sarawak</strong> for 11 years.<br />

Taib, who has silver hair, appears almost daily on the front<br />

pages <strong>of</strong> <strong>Sarawak</strong> newspapers, sometimes sporting a goatee and<br />

a pair <strong>of</strong> rimless glasses, at the opening <strong>of</strong> new development<br />

projects or local events. He lives in <strong>Sarawak</strong>’s <strong>capital</strong> city <strong>of</strong><br />

Kuching, an urban area <strong>of</strong> about 600,000 people on the <strong>Sarawak</strong><br />

River. Its picturesque waterfront is dotted with colonial buildings,<br />

the legacy <strong>of</strong> British adventurer James Brooke, who<br />

founded the Kingdom <strong>of</strong> <strong>Sarawak</strong> in 1841 and became known as<br />

the White Rajah. Brooke’s heirs ruled the kingdom until 1946,<br />

when Charles Vyner Brooke ceded his rights to the U.K. <strong>Sarawak</strong><br />

joined the Federation <strong>of</strong> Malaysia on Sept. 16, 1963, along<br />

with other former British colonies.<br />

At Taib’s mansion, which overlooks the river, he receives<br />

guests in a living room decorated with gilt-edged Europeanstyle<br />

s<strong>of</strong>a sets, according to photos in the July to December<br />

2006 newsletter <strong>of</strong> Naim Cendera Holdings Bhd., which<br />

changed its name to Naim Holdings Bhd. in March. Naim is a<br />

property developer and contractor whose chairman is Taib’s<br />

cousin, Abdul Hamed Sepawi. He is also chairman <strong>of</strong> state<br />

power company <strong>Sarawak</strong> Energy and timber company Ta Ann<br />

Holdings Bhd., and is on the board <strong>of</strong> <strong>Sarawak</strong> Timber Industry<br />

Development Corp. and <strong>Sarawak</strong> Plantation Bhd.<br />

landov (top); xping via flickr

122<br />

bloomberg markets October 2009

Naim and cms jointly built Kuching’s iconic waterfront<br />

building, the umbrella-ro<strong>of</strong>ed, nine-story <strong>Sarawak</strong><br />

State Legislative Assembly complex. Naim has won<br />

more than 3.3 billion ringgit worth <strong>of</strong> contracts from<br />

the state and the federation since 2005, its stock exchange filings<br />

show. Ricky Kho, a spokesman for Naim, said the company<br />

declined to comment for this article. Naim’s deputy managing<br />

director, Sharifuddin Wahab, said in an interview with<br />

Bloomberg News in July 2007, that the chairman’s family ties<br />

weren’t why the company won government contracts. “We<br />

have been able to execute our projects on time, we stick to the<br />

budget and the quality <strong>of</strong> what we hand over to the government<br />

is up to their expectations, if not more,” he said.<br />

“Our teams have always acted pr<strong>of</strong>essionally” when working<br />

with the government, whether on large or small projects, CMS’s<br />

group managing director, Richard Curtis, said in an e-mail.<br />

“CMS is governed by the strict listing regulations <strong>of</strong> the Malaysian<br />

stock exchange,” he said, adding that the chairman and the<br />

group managing director are both independent.<br />

“The large projects carry with them an equally large risk, including<br />

a huge reputational risk, particularly for crucial projects<br />

by the government,” he said. “It is the government’s<br />

prerogative and discretion to award projects using a variety <strong>of</strong><br />

approaches that includes open and closed tenders as well as directly<br />

negotiated processes, to the contractors and developers<br />

they feel will deliver the project as promised.”<br />

Malaysia’s reputation as a place to conduct business has<br />

deteriorated in recent years, according to Transparency International,<br />

the Berlin-based advocacy group that publishes an<br />

annual Corruption Perceptions Index. Transparency ranked<br />

the country 47th out <strong>of</strong> 180 in 2008,<br />

down from 43rd in 2007. Transparency<br />

also has singled out the Bakun Hydroelectric<br />

Dam, under construction on the<br />

Balui River in <strong>Sarawak</strong>, as a “monument<br />

<strong>of</strong> corruption.”<br />

The index lacks fairness, says Ahmad<br />

Said Hamdan, chief commissioner <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission,<br />

because it doesn’t take into consideration<br />

the size <strong>of</strong> the population <strong>of</strong> the<br />

countries in the ranking, for example.<br />

“I’ve seen a lot <strong>of</strong> improvement in civil<br />

service in the past 10 years,” he says.<br />

Early this year, hundreds <strong>of</strong> dead fish<br />

started floating on the muddy river near<br />

Penan people have the Bakun dam site. The fish were killed<br />

lived for centuries by by siltation, which was triggered by uncontrolled<br />

logging upstream, <strong>Sarawak</strong>’s<br />

fishing and hunting in<br />

the forest. Penan<br />

headman and antilogging<br />

activist<br />

public health, Abang Abdul Rauf Abang<br />

assistant minister <strong>of</strong> environment and<br />

Kelesau Naan, above,<br />

died under mysterious Zen, says. He says the Bakun dam has<br />

circumstances.<br />

very strict environmental assessments<br />

and isn’t to blame for the siltation.<br />

123<br />

October 2009 bloomberg markets

124<br />

In January, Tenaga Nasional Bhd., Malaysia’s state-controlled<br />

power utility, and <strong>Sarawak</strong> Energy said they won approval<br />

from the national government to take over the operation<br />

<strong>of</strong> the hydropower project through a leasing agreement. <strong>Sarawak</strong><br />

Energy also won preliminary approval to export about<br />

1,600 megawatts <strong>of</strong> electricity from the 2,400-megawatt Bakun<br />

project, once it begins operating, to Peninsular Malaysia. The<br />

remaining power will go to <strong>Sarawak</strong>.<br />

In 1994, Taib announced a plan called New Concept. The<br />

aim was to bring together local people, with their customary<br />

rights to the land, and private shareholders, who would<br />

‘the government is cruel,’ says Jengga Jeli, a Lebor<br />

resident whose village has sued for compensation.<br />

‘fruit trees have been cut down. It’s become<br />

harder to hunt and fish.’<br />

provide <strong>capital</strong> and expertise to create plantations. The plan<br />

called for companies to hold a 60 percent stake in the joint<br />

ventures, the state to own 10 percent and the remaining 30<br />

percent to go to local communities in return for a 60-year<br />

lease on their land. That time period equals about two complete<br />

cycles <strong>of</strong> oil palm development. An oil palm typically matures<br />

in 3 years, reaches peak production from 5 to 7 years and<br />

continues to produce for about 25 years, says Nirgunan<br />

Tiruchelvam, a commodities analyst at Royal Bank <strong>of</strong> Scotland<br />

Group Plc in Singapore.<br />

The policy has led to some disagreements. In his interview<br />

with Bernama in 2001, Taib said land acquisitions<br />

by the state have led to “emotional” disputes because<br />

some people seek too much compensation. “We are<br />

not allowed to pay more than market value,” he told Bernama.<br />

He said people need to prove that they have traditionally lived<br />

in an area—for example, by providing an aerial photograph—in<br />

order for the state to grant them title to the land. “If there are<br />

disputes, they go to the court,” Taib told Bernama.<br />

Some local people say they received no compensation at all<br />

for their land. In Kampung Lebor, a village about a two-hour<br />

drive from Kuching, 160 families, members <strong>of</strong> the Iban group<br />

that was formerly headhunters, live in longhouses and survive<br />

by fishing and some farming. The Iban are <strong>Sarawak</strong>’s largest single<br />

group <strong>of</strong> Dayaks, who make up about half <strong>of</strong> the state’s 2.3<br />

million population.<br />

In mid-1996, the state handed out parcels <strong>of</strong> land that overlapped<br />

with the community’s customary hunting and fishing<br />

areas to the Land Custody and Development Authority and<br />

Nirwana Muhibbah Bhd., a palm oil company in Kuching. In<br />

mid-1997, the authority and the company cleared the land with<br />

bulldozers and planted oil palm seedlings, according to a copy<br />

<strong>of</strong> Kampung Lebor’s writ <strong>of</strong> summons filed to the High Court<br />

in Kuching.<br />

“The government is cruel,” says Jengga Jeli, 54, a father <strong>of</strong><br />

five in Lebor. “Fruit trees have been cut down. It’s become<br />

bloomberg markets October 2009<br />

harder to hunt and fish. Now we are forced to get meat and vegetables<br />

from the bazaar, and we are very poor.” Jengga’s village<br />

filed a lawsuit in 1998 against Nirwana, LCDA and the state government<br />

in a bid to get compensation.<br />

The case was finally heard in 2006 and is now awaiting judgment,<br />

according to Baru Bian, who is representing the Iban in<br />

Kampung Lebor. Reginal Kevin Akeu, a lawyer at Abdul Rahim<br />

Sarkawi Razak Tready Fadillah & Co. Advocates, which is representing<br />

Nirwana and LCDA, declined to comment.<br />

The cases show that the development projects, including<br />

plantations and dams, haven’t helped poverty among the local<br />

people, many <strong>of</strong> whom live without adequate<br />

electricity or schools, says Richard<br />

Leete, who served as the resident representative<br />

<strong>of</strong> the United Nations Development<br />

Program for Malaysia, Singapore<br />

and Brunei from 2003 to 2008.<br />

“This is the paradox <strong>of</strong> <strong>Sarawak</strong>—the great wealth it has, the<br />

natural resources in such abundance, and yet such an impoverishment<br />

and the real hardship these communities are suffering,”<br />

says Leete, who chronicled Malaysia’s progress since its<br />

independence from Britain in his book Malaysia: From Kampung<br />

to Twin Towers (Oxford Fajar, 2007). “There has no doubt been<br />

a lot <strong>of</strong> money politics,” he says.<br />

In the rugged hills about 150 kilometers (93 miles) south <strong>of</strong><br />

Kuching, some 160 Bidayuh families, known as the Land<br />

Dayaks, are clinging to their traditional habitat, while a dam is<br />

under construction nearby. They live by farming and fishing.<br />

With only a primary school in the village, children have to go to<br />

boarding schools outside the jungle to get further education,<br />

crossing seven handmade bamboo bridges and trekking two<br />

hours over the hills when they return home. The state has <strong>of</strong>fered<br />

the Bidayuhs 7,500 ringgit per hectare, 80 ringgit per rubber<br />

tree and 60 ringgit per durian fruit tree in compensation for<br />

their native land, says Simo ak Sekam, 48, a resident <strong>of</strong> Kampung<br />

Rejoi, one <strong>of</strong> four villages in the<br />

See Chee How, a<br />

land rights lawyer<br />

for the Dayaks, in<br />

front <strong>of</strong> a poster<br />

<strong>of</strong> opposition<br />

leader Anwar.<br />

area. In Rejoi, about half <strong>of</strong> 39 families<br />

have refused.<br />

“We don’t want to move because we<br />

are happy here,” Simo says. “We feel<br />

very sad because our land will be

126<br />

covered with water. The<br />

young generations won’t<br />

know this land. They won’t<br />

see the bamboo bridges.”<br />

The builder <strong>of</strong> the local<br />

reservoir is Naim Holdings—the<br />

company headed<br />

by Chief Minister Taib’s<br />

cousin. The state awarded<br />

Naim the 310.7 million–<br />

ringgit contract without<br />

putting it out for bids.<br />

Naim’s statement announcing<br />

the deal in July 2007 said<br />

it won the job on a “negotiated<br />

basis.”<br />

One <strong>of</strong> the most threatened<br />

groups is the Penan,<br />

nomadic people who live<br />

deep in the jungle on the upper<br />

reaches <strong>of</strong> the Baram<br />

River. On a steamy equatorial<br />

morning in late October<br />

2007, Long Kerong village leader Kelesau Naan and his wife,<br />

Uding Lidem, walked two hours to their rice-storing hut. Kelesau,<br />

who was in his late 70s and who had protested logging activity<br />

in their area, told Uding he’d go check on an animal trap<br />

he had set nearby. He never came back.<br />

Two months later, his skull and several pieces <strong>of</strong> his<br />

bones, along with his necklace made <strong>of</strong> red, yellow and<br />

white beads, surfaced on the banks <strong>of</strong> the Segita River.<br />

Inspector Sumarno Lamundi at the regional police<br />

station says the investigation is ongoing.<br />

It was just the latest tragedy among activists working for the<br />

Penan since the early 1990s, when rampant logging took place.<br />

At least two other Penan were found dead, including Abung<br />

Ipui, a pastor and an advocate for land rights for his village. His<br />

body was found in October 1994 with his stomach cut open.<br />

Manser, the Swiss activist for the rights <strong>of</strong> the Penan, vanished<br />

without a trace from the Borneo rain forests in May 2000 and<br />

was <strong>of</strong>ficially declared missing in March 2005.<br />

Kelesau’s death has made the Penan willing to stand up for<br />

their survival. “We are scared <strong>of</strong> something terrible happening<br />

to us if we don’t resist,” says grim-faced Bilong Oyoi, 48, headman<br />

<strong>of</strong> Long Sait, a Penan settlement close to Long Kerong. Bilong,<br />

who wears a traditional rattan hat decorated with hornbill<br />

feathers, says his group is setting up blockades to resist logging<br />

activities. They are also working with NGOs to get attention for<br />

their plight and filing lawsuits.<br />

With the help <strong>of</strong> the Basel, Switzerland–based Bruno Manser<br />

Fund, an NGO set up by the late activist, Bilong and 76 other<br />

Penan sent a letter—which some signed using only thumb<br />

prints—to Gilles Pelisson, the chief executive <strong>of</strong>ficer <strong>of</strong> French<br />

bloomberg markets October 2009<br />

A Penan man in<br />

traditional garb<br />

hunts using darts<br />

and a blowpipe.<br />

hotel chain Accor SA. The letter urged Accor<br />

to think twice about partnering with<br />

logging company Interhill Logging Sdn. to<br />

build a 388-room Novotel Interhill in<br />

Kuching. The Penan community says Interhill’s<br />

operations in <strong>Sarawak</strong> have a devastating effect on them.<br />

Accor responded by sending a fact-finding mission to <strong>Sarawak</strong><br />

to investigate Interhill’s logging activities. “If the worstcase<br />

scenario occurs and if no action plan is implemented, we<br />

will not continue with our partnership,” Helene Roques, Accor’s<br />

director for sustainable development in Paris, said in<br />

June. In mid-August, she said she expects “good results” by the<br />

end <strong>of</strong> September.<br />

No foreign investor has made a larger bet on Taib’s development<br />

plans than Rio Tinto Alcan, a unit <strong>of</strong> London-based mining<br />

company Rio Tinto Plc. A joint venture between Rio Tinto<br />

and CMS for a $2 billion aluminum smelter has been negotiating<br />

power purchase agreements with <strong>Sarawak</strong> Energy for more<br />

than 12 months, according to Julia Wilkins, a Rio Tinto Alcan<br />

spokeswoman in Brisbane, Australia.<br />

CMS meets Rio Tinto’s requirements as a joint-venture partner,<br />

she says. “CMS is a main-board-listed company with its<br />

own board <strong>of</strong> directors,” she says. “It has a free float <strong>of</strong> shares in<br />

excess <strong>of</strong> the minimum market requirement. The chairman and<br />

the group managing director are both independent.”<br />

Malaysia grants special economic advantages to the country’s<br />

Malay majority and the local people <strong>of</strong> Sabah and <strong>Sarawak</strong><br />

states on Borneo, collectively referred to as Bumiputra—literally,<br />

sons <strong>of</strong> the soil. Still, the country is leaving behind many <strong>of</strong><br />

its ethnic minorities, says Colin Nicholas, a Malaysian activist <strong>of</strong><br />

Eurasian descent who has written a book about the mainland’s

oldest community,<br />

The Orang<br />

Asli and the Contest<br />

for Resources<br />

(IWGIA, 2000).<br />

One person trying<br />

to help the<br />

Dayaks is See<br />

Chee How, 45, a<br />

land rights lawyer<br />

who became an activist after meeting Sim, the former opposition<br />

member <strong>of</strong> parliament in Kuching. In 1994, See witnessed<br />

an attack on Penan demonstrators who’d erected a roadblock<br />

to prevent logging trucks from driving through their land. A<br />

6-year-old boy died after security forces used tear gas on the<br />

demonstrators, he says. “They were completely powerless,”<br />

recalls the s<strong>of</strong>t-spoken, crew-cut See, sporting a white T-shirt<br />

and a pair <strong>of</strong> jeans, in his <strong>of</strong>fice above a bustling market in<br />

Kuching. “They were depending on logging trucks to move<br />

around because their passageways had been destroyed by logging<br />

trails.” See now works with Baru Bian, 51, one <strong>of</strong> the first<br />

land rights lawyers representing the Dayaks in <strong>Sarawak</strong>.<br />

Nicholas says <strong>Sarawak</strong>’s people have to fight for their rights<br />

not only through lawsuits but by voting. “The biggest problem<br />

we have with indigenous people’s rights is that we have the federal<br />

government and state government run and dictated by<br />

people who have no respect or interest for indigenous people,”<br />

he says. “We need a change <strong>of</strong> government.” The prime minister’s<br />

<strong>of</strong>fice declined to comment.<br />

Opposition leader Anwar says change is possible. His<br />

Palm Oil Statistics<br />

To use the Commodity Curve Analysis function to display the<br />

forward curve for the palm oil futures that trade on the<br />

Malaysia Derivatives Exchange, type KOA CCRV<br />

. For prices from the Malaysian Palm Oil Board, type<br />

POIL , as shown below. To display headlines <strong>of</strong> news<br />

stories related to Malaysia, type NI MALAYSIA .<br />

You can use the Equity Screening (EQS) function<br />

to find publicly traded companies that grow<br />

oil palms. Type EQS and click on Product<br />

Segments in the Universe Criteria section <strong>of</strong> the<br />

screen. Tab in to the Search field, enter PALM OIL<br />

and press . Then click on Palm Oil Farming in<br />

the list <strong>of</strong> Search Results. For companies that<br />

derive at least 10 percent <strong>of</strong> their revenue from<br />

palm oil farming, click on the first arrow under<br />

Step 2. Select Measure to Analyze, in blue, and select<br />

Revenue Percent if it isn’t already selected.<br />

Click on the next arrow to the right, select Latest<br />

Filing and click on the Update button. In the menu<br />

<strong>Sarawak</strong>’s State<br />

Legislative<br />

Assembly<br />

complex was<br />

built by two<br />

companies with<br />

family ties to the<br />

chief minister.<br />

alliance won control <strong>of</strong> an unprecedented<br />

five states in Peninsular Malaysia<br />

in a March 2008 election. Malaysian<br />

Prime Minister Najib Razak’s ruling coalition<br />

has lost at least four regional polls<br />

held this year. “I think this is a turning<br />

point,” Anwar says.<br />

Still, Taib’s coalition won 30 <strong>of</strong> <strong>Sarawak</strong>’s<br />

31 seats in March 2008 parliamentary<br />

elections. That helped the ruling<br />

National Front coalition led by then<br />

Prime Minister Abdullah Ahmad Badawi<br />

retain a 58–seat majority, ahead <strong>of</strong> Anwar’s<br />

People’s Alliance. <strong>Sarawak</strong> is due<br />

to hold the next election by 2011.<br />

Taib defended his government’s program<br />

to turn forestlands into oil palm<br />

plantations as a way <strong>of</strong> improving living<br />

standards for the Dayaks at a seminar on native land development<br />

in Miri on April 18, 2000. “Land without development is<br />

a poverty trap,” he said, according to his Web site. Many<br />

Dayak people, who have seen their land transformed as a result<br />

<strong>of</strong> Taib’s policies and companies linked to him, say they<br />

are still waiting to see their share <strong>of</strong> wealth. ≤<br />

Yoolim Lee is a senior writer at Bloomberg News in Singapore.<br />

yoolim@bloomberg.net With assistance from Claire Leow in Singapore<br />

and Ranjeetha Pakiam in Kuala Lumpur.<br />

To write a letter to the editor, type MAG or send an e-mail<br />

to bloombergmag@bloomberg.net.<br />

<strong>of</strong> conditions that appears on the main page <strong>of</strong> EQS, select<br />

>= Greater Than Or Equal To. In the field that appears below,<br />

enter 10% and press . Click on the Results button for a<br />

list <strong>of</strong> the matching companies.<br />

JON ASMUNDSSON<br />

128<br />

bloomberg markets October 2009