LATIN 4A, AP VERGIL: ESSAY #2 COMPILATION - Quia

LATIN 4A, AP VERGIL: ESSAY #2 COMPILATION - Quia

LATIN 4A, AP VERGIL: ESSAY #2 COMPILATION - Quia

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

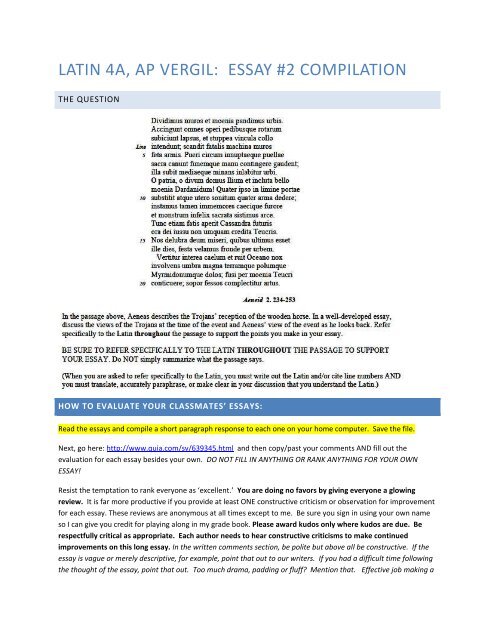

<strong>LATIN</strong> <strong>4A</strong>, <strong>AP</strong> <strong>VERGIL</strong>: <strong>ESSAY</strong> <strong>#2</strong> <strong>COMPILATION</strong><br />

THE QUESTION<br />

HOW TO EVALUATE YOUR CLASSMATES’ <strong>ESSAY</strong>S:<br />

Read the essays and compile a short paragraph response to each one on your home computer. Save the file.<br />

Next, go here: http://www.quia.com/sv/639345.html and then copy/past your comments AND fill out the<br />

evaluation for each essay besides your own. DO NOT FILL IN ANYTHING OR RANK ANYTHING FOR YOUR OWN<br />

<strong>ESSAY</strong>!<br />

Resist the temptation to rank everyone as ‘excellent.’ You are doing no favors by giving everyone a glowing<br />

review. It is far more productive if you provide at least ONE constructive criticism or observation for improvement<br />

for each essay. These reviews are anonymous at all times except to me. Be sure you sign in using your own name<br />

so I can give you credit for playing along in my grade book. Please award kudos only where kudos are due. Be<br />

respectfully critical as appropriate. Each author needs to hear constructive criticisms to make continued<br />

improvements on this long essay. In the written comments section, be polite but above all be constructive. If the<br />

essay is vague or merely descriptive, for example, point that out to our writers. If you had a difficult time following<br />

the thought of the essay, point that out. Too much drama, padding or fluff? Mention that. Effective job making a

point? Good! Say so. Be constructive and provide specific suggestions for improvements. Avoid comments<br />

regarding formatting unless citation has been done poorly.<br />

Please observe a hierarchy of ranking. The best essays should receive appreciably higher ranks than poorer essays.<br />

(you are NOT doing favors by trying to be nice to everyone).<br />

COMPLETE THIS EVALUATION SURVEY ONLINE NO LATER THAN FRIDAY, OCTOBER 25 ET MIDNIGHT.<br />

Once the evaluations are done, I’ll send out a compilation of essay critiques including the grade for each essay.<br />

Keep track of your own essay # for future reference: you’ll receive your grade by essay number.<br />

THE <strong>ESSAY</strong>S<br />

Once again, each essay has been randomly assigned a number. Use this number when evaluating the essays<br />

online. Refer to these numbers again for responses to your essay once I complete the compilation of rankings and<br />

comments.<br />

#1<br />

The Reception of the Horse<br />

The reception of the Trojans to the horse is evident in the very first line of the passage:<br />

Dividumus muros et moenia pandimus urbis, “we divide the ramparts and open the walls of the city”<br />

(Aeneid 2.234). Here, the Trojans appear willing to destroy their defense, the ramparts, and expose their<br />

city to allow the horse, of which they know nothing, into it. The Trojans relinquish their safety for a<br />

sacrifice (the horse), although they do not know that the real sacrifice will be their lives and city. They<br />

receive the horse without any apparent misgivings about its purpose and background.<br />

The next phrase, accingunt omnes opera, “all equip themselves for the task” (2.235), indicates<br />

that none, save for the now-dead Laocöon, have misgivings about the horse. Each citizen aids in the<br />

horse’s journey into and through the city in that they “place rolling wheels under its feet, and extend<br />

cables of hemp from its neck” (pedibusque rotarum subiciunt lapsus, et stuppea vincula collo intendant,<br />

2.235-237). The Trojans go through great lengths to ensure that the horse will enter the city by first<br />

destroying the fortifications, and then using rope and wheels, and their brute strength, to move it.<br />

They may have also felt that by seizing and binding the horse with hemp rope—a strong type of<br />

cord—they were symbolically capturing the Greeks. The passage indicates that pueri circum innuptaeque<br />

puellae sacra canunt funemque manu contingere gaudent, “around boys and unmarried girls sing sacred<br />

songs and exult to touch the rope with their hands” (2.237-238). The boys and girls, in singing sacred<br />

songs, emphasize that the horse is intended as a sacrifice, while their exultation in touching the ropes<br />

strengthens the impression that the ropes symbolized a Greek capture.<br />

The impression that the Trojans have no misgivings of danger is again emphasized in the phrase<br />

mediaeque minans inlabitur urbi, “and [the horse] glides into the middle of the city” (2.240). The center

of a city is the most vulnerable and important area, and for the Trojans to bring the unknown horse into it<br />

shows their faith and whole-hearted acceptance in its unthreatening appearance.<br />

However, in the next lines, Aeneas’ opinion is evident as he bemoans his countrymen’s stupidity<br />

and ignorance. He cries out to the three things most important to himself: his country, o patria (2.241),<br />

the household gods, o divum domus Ilium (2.241), and the city itself, moenia Dardanidum (2.242). In the<br />

next phrase, he addresses their folly. The use of the word quater, “four times” (2.242-243), reveals the<br />

true depth of heedlessness by hammering the idea repetitively into the reader. In context, the word<br />

presents an anaphoric presentation to emphasize its point: quater ipso in limine portae substitit atque uter<br />

sonitum quater arma dedere, “four times it [the horse] halts in the threshold of our gates and four times<br />

weapons give a sound from its womb” (2.242-243). Aeneas is stating that they could hear suspicious<br />

sounds coming from inside the horse not once, not twice, but four times, and they disregarded the sound<br />

while they were, as Aeneas puts it, “blind in our frenzy” (caecique furore, 2.244). The subtle insinuation<br />

of Aeneas is that the Trojans had plenty of opportunities (four times!) to stop the horse’s progress. They<br />

were so enraptured in celebration that they continue to bring the horse through their gates.<br />

Aeneas uses the words limine portae, “the threshold of our gates”, to represent a bit of irony and<br />

foreshadowing—although the event had already happened reality. “Threshold” has the connotations<br />

“edge” or “brink”, giving a different angle to the image being created. In substituting one of the previous<br />

words, the phrase becomes “the edge of the gates”. Now the reader knows that the horse was almost into<br />

the city; it was on the brink, the very edge, though not far enough in to destroy any possibility of removal<br />

from the city’s premises. Aeneas is again implying that the Trojans could have stopped the horse from<br />

entering the city, if they had not been caecique furore.<br />

Aeneas’ opinions of the horse appear in the passage by his reference to the horse as a fatalis<br />

machine, “fatal machine” (2.237), and a monstrum unfelix, “wretched monster” (2.245). He, with<br />

hindsight, calls the horse those names since he knows of the treachery and misery it would bring with its<br />

arrival. His views of the horse are ones of loathing and regret.<br />

Aeneas presents another irony for the Trojans in his mention of Cassandra. She, says Aeneas,<br />

would “disclose our future fates” (2.246) and yet would “never be believed by the Trojans” (2.247). By<br />

decree of a Apollo, dei iussu (2.247), Cassandra would never have her prophesies believed, and so<br />

Aneas—or more correctly Vergil—finds the irony fitting for the Trojans who, in addition to being<br />

caecique furore, were also deaf to reason. The Trojans continue to think that danger from the horse is<br />

nonexistent. Their views of horse consist of enchantment and celebration.<br />

Aeneas discloses his own grief at the approaching danger, yet opinion in the passage:<br />

nos…miseri, quibus ultimus ille dies, “we miserable men, for whom that day would be our last” (2.248-<br />

249). Aeneas already knows what is coming, and he can only add his personal interjections in retelling the

story. The phrase delubra deum…festa velamus fronde per urbem, “we clothe the temples of the gods<br />

with fronds throughout the city” comes after Aeneas’ exclamation, showing his distress in knowing that<br />

that would be the last day of Troy and that they were decorating their city in celebration as well as in<br />

ignorance of their demise: the horse. Another cruel irony presented on Vergil’s part.<br />

Night, darkness, and sleep especially, have often been used to imply secrecy and ignorance. The<br />

following paragraph after the Trojans’ celebration follows the trend: involens umbra magna terramque<br />

polumque Myrmidonumque dolos, “[the night] envelops[ing] the earth and sky and the tricks of the<br />

Myrmidons in its great shadow” (2.251-252). The use of the word involvens, “enveloping”, implies that<br />

the night is conspiring against the Trojans to hide the coming disaster. In conjunction with what happens<br />

when night comes, sleep lulls the Trojans into a false sense of security; the Trojans think and feel<br />

themselves safe enough to sleep. Aeneas uses the words fusi, a perfect passive participle, and the noun<br />

Teucri to form the phrase “routed Trojans” (2.252), in order to indicate that the Trojans are already<br />

defeated even before they have gone to sleep (sopor fessos complectitur artus, 2.253). Their weary limbs,<br />

fessos artus, are indicative of much drinking and celebration.<br />

Throughout the passage, Aeneas’ opinion is represented as being remorseful and grieved at the<br />

ignorance and heedlessness of his countrymen. Since he is retelling the story, he allows himself to insert<br />

his opinion is small words and phrases such as fatalis machina or monstrum unfelix or Myrmidonumque<br />

dolos. The entire piece contains a sort of reflective resignation as Aeneas narrates the destruction of Troy.<br />

He knows that at the time he could have done little to stop it, after witnessing the fate of Laocöon;<br />

besides, he was perhaps caught up in the frenzied celebration.<br />

The Trojans, in Aeneas’ words, were blind in their madness (caecique furore), deaf to reason (from the<br />

prophetess Cassandra), and altogether heedless of any danger the horse presented to them. They received<br />

and viewed the horse as a boon to the war, an intended sacrifice, and a symbolical exhibition of<br />

defeating the Greeks.<br />

<strong>#2</strong><br />

How Happy Were We Fools<br />

No one can ever change the past. It is impossible. Still, there are always those who wish they could.<br />

In Aeneas’ retelling of the entrance of the wooden horse in to Troy, the overwhelming feel of the passage<br />

is one of grief and regret, although the Trojan’s reaction at the time was one of bliss and elation. Ashamed<br />

of how foolish the Trojans had been in welcoming the horse, Aeneas tells the audience of their reaction in<br />

full detail, as if asking to be punished or judged for it, yet without ridiculing them for having been glad.<br />

Aeneas sees the past actions of the Trojans as foolish, unequivocally describing them as<br />

immemores caecique furore, “heedless and blind with madness.” [Aeneid 2.243] But the actions of the

Trojans are nearly all in the first person plural: we. Dividimus muros et moenia pandimus, “We<br />

separated the ramparts and opened the walls.” [2.234] Instamus… immemores, “We press on…heedless.”<br />

[2.343] These snippets illustrate Aeneas’ complex attitude towards the Trojan’s reaction. Yes, in<br />

hindsight, it was ill-considered to tear down the walls, or to press on heedless of the clink of weapons<br />

inside the horse, but Aeneas does not absolve himself from the group’s guilt. He is a Trojan too, and acted<br />

alongside the people he describes.<br />

Notably, although Aeneas’ account shows us the pure joy of the Trojans upon receiving the horse,<br />

he never ceases to remind us that it was a machine of death. The descriptions of the Trojan’s festive<br />

reactions in this passage are closely juxtaposed with ominous adjectives describing the Greeks’<br />

contraption. Scandit fatalis machina muros feta armis. pueri circum innuptaeque puellae sacra canunt<br />

funemque manu contingere gaudent; illa subit mediaeque minans inlabitur urbi., “The deadly machine<br />

goes up the walls, pregnant with weapons. All around, boys and unmarried girls sing sacred songs, and<br />

rejoice to touch the rope with their hands. That thing goes up and glides, threatening the middle of the<br />

city.” [2.237-240] Later, the cheerful Trojans who deck the shrines of the gods with festive foliage<br />

throughout the city are forebodingly described in the same breath as miseri, quibus ultimus esset ille dies,<br />

“wretched ones, for whom that day would be the last.” [2.248-249] Aeneas’ (or Vergil’s) insistence on<br />

contrasting the celebratory war-is-over attitude of the Trojans, with the real, imminent threat of the horse<br />

sets up a parallel to show that Aeneas is also at odds with himself since he was also one of the Trojans<br />

who “stood the cursed monster in the sacred citadel.” [2.245]<br />

In the middle of the passage, the reader is confronted with a sudden and plaintive apostrophe to<br />

Aeneas’ lost country. O patria, o divum domus Ilium et incluta bello moenia Dardanium!, “O fatherland!<br />

O Ilium, home of the gods and Dardanian walls renowned in war!” [2.240-242] Aeneas departure from<br />

his retelling of the events reveals his mental state as anguished. The grief has become too much to bear,<br />

even more as he recalls the greatness that was Troy, because it is all now irretrievably demolished.<br />

Immediately, he goes on to describe how they had a number of lost opportunities to turn back.<br />

Quater ipso in limine portae substitit atque utero sonitum quater arma dedere, “Four times it stood on<br />

the threshold of the gates, and four times, the weapons gave a sound in its very womb.” [2.242-243] The<br />

word quater, “four times” is emphasized. The repetition of quater which Vergil has placed in Aeneas’<br />

mouth effectively conjures up an image of the Trojan leader silently cursing himself. It shows that he<br />

feels guilty for a failure outside of his control, a scene which Vergil must have intended to inspire the<br />

reader’s compassion.<br />

Aeneas even regrets not having listened to Cassandra, even though the Fates and Apollo’s<br />

ordinance made it impossible. Fate plays a huge role in letting the horse into the city, and Aeneas’<br />

recognition of fate in 2.246 as a reason why Cassandra is never believed, shows a sense of resignation.

The reader can see that Aeneas, despite his feelings of loss, recognizes that there is nothing anyone could<br />

have done to save Troy.<br />

Silence can sometimes speak louder than words; it is notable that rejoicing is not among the actions<br />

Aeneas lists as foolish. In his eyes, the horse is a curse of fate ironically treated as a blessing at first, but<br />

besides fate, the Trojans do have good reason to welcome the horse and rejoice. Firstly, the foe appears to<br />

have retreated and the war seems to be over. Secondly, Laocoon’s death was an ambiguous omen. It could<br />

be interpreted as a divine punishment for rejecting the horse. When Aeneas says nos delubra deum miseri,<br />

quibus ultimus esset ille dies, festa velamus fronde, “We wretched ones, for whom that day would be the<br />

last, deck the temples of the gods with festive foliage” [2.248-249], he describes the Trojans as wretched<br />

not because they are happy, but because they are about to die. At the very end of the passage, in an almost<br />

fatherly manner, he describes the exhausted Trojans sleeping outside all about, gradually falling silent,<br />

until sopor fessos complectitur artus, “Sleep embraced their weary limbs in its arms.” [2.253] Aeneas<br />

allows the fallen this: does not condemn their joy.<br />

Near the end of the passage, Aeneas describes the subsequent nightfall. Vertitur interea caelum et<br />

ruit oceano nox involvens umbra magna terramque polumque Myrmidonumque dolos, “Then the sky<br />

turned on its point, and night fell upon the ocean, covering the sky, land and all the deceit of the Greeks<br />

in its huge shadow.” [2.250-252] It is a very peaceful image of the natural world, in stark contrast to the<br />

destruction that will take place later on. Aeneas is waxing poetic. It is almost like a breath of fresh air<br />

after intense weeping. Yes, Aeneas does see the desolation of Troy, his homeland, as a catastrophic<br />

misfortune, but the imagery in this passage reinforces the idea that he accepts it was as inevitable as a<br />

force of nature. In this last scene, the umbra magna, “the great shadow” of night covers everything, both<br />

natural things such as sky, sea, and land, and the manmade incarnation of the Greeks’ scheme. None of<br />

these things can be stopped, but perhaps, someday, the Greeks too will be subject to justice.<br />

The whole passage of Aeneas’ retelling the entrance of the horse is a vivid example of the<br />

difference that hindsight can make. None of the Trojans would have felt such joy and inner peace if they<br />

could have known what was to befall them later. It is because Aeneas knows the outcome of welcoming<br />

the horse that his retelling is so full of regret. If only he could have done something, we almost hear him<br />

think to himself. But he is as powerless to change the story in his retelling of it as he was powerless to<br />

alter the original course of events, and he knows it. Why then relate the story of the Trojan’s initial<br />

happiness? Vergil here adds depth to Aeneas’ character. Aeneas is someone who is still going to<br />

remember the good things that were lost, most importantly, the fallen. It is out of respect for them that he<br />

does not belittle their joy, even though he admits that letting the horse in was foolish. Aeneas, as a<br />

survivor, feels guilt, and because of it, feels compelled to tell the entire story of the last day of Troy, and<br />

why the Trojans did what they did.

#3<br />

Horses, Horror, and Multifaceted Regret<br />

Aeneas looks back on the Greek attack with the Trojan horse as a disaster. This is in part because<br />

of some Trojans’ misunderstanding of the horse (they interpreted it as perhaps an offering to the gods,<br />

when it was actually filled with marauding Greek soldiers). On the other hand, Aeneas claims that<br />

although the horse was appreciated by many Trojans, some were rightly suspicious of this perhaps “toogood-to-be-true”<br />

gift from the Greeks.<br />

Aeneas indicates throughout the passage that he thinks the event was very calamitous, and also<br />

that his fellow Trojans erroneously believed the arrival of the horse was a positive event. One instance in<br />

which he develops this point is when he says “Nos… miseri, quibus ultimus esset ille dies” ([We are]<br />

miserable men, for whom this would be our last day) (Aeneid 2.248-249). Here he not only indicates his<br />

overall dismay over the event, but he makes a hidden reference to how far off the Trojans’ estimate of the<br />

function of the horse may have been from its true function. He uses a poetic device called hyperbaton,<br />

placing two words between nos and its modifier, miseri. The distance between these two words represents<br />

the difference between the apparent beliefs of the Trojans about the horse and what the horse actually<br />

was.<br />

What is more in doubt is the overall view of the Trojans of this horse. It at first seems clear that<br />

the Trojans are lauding this wooden horse and thinking of it as a gift from the gods. In fact they were so<br />

enamored of this horse that when Cassandra opened her mouth with the future fates (fatis aperit<br />

Cassandra futuris ora) (2.246-7), that is, when she told the Trojans about the real purpose of the horse,<br />

she was not trusted by the Trojans (non umquam credita Teucris) (2.247). This shows how much the<br />

Trojans admired the horse.<br />

There are several selections from the passage that indicate that the Trojans are heaping praise on<br />

this huge wooden horse. When he says dividimus muros (we divide the walls) (2.234), he means that they<br />

opened the city walls for a ceremonial presentation of the horse. Also, boys and unmarried girls sing<br />

sacred songs around the horse. (Pueri circum innuptaeque puellae sacra canunt) (2.238-9). This indicates<br />

that the horse may be an offering to the gods, as evidenced by the word sacra, and also a wedding<br />

centerpiece. This is ironic, since its ultimate purpose was to attack the Trojans—virtually the opposite of<br />

what was initially thought. The use of irony here represents the disparity between Aeneas’s attitude<br />

looking back on the event and some of his men’s attitude during the event.<br />

The conflict of the two different attitudes is most notable when Aeneas describes the horse as a<br />

monstrum infelix (a bad omen) (2.245), but at the same time recalls the Trojans standing the horse, as if to<br />

present it as an offering, in the sacred citadel (sacrata sistimus arce) (2.245). It is possible that the use of

the term “bad omen” close to a reference to the Trojan feelings about the wooden horse indicates that the<br />

Trojans had an inkling that this horse was a weapon, and that their treatment of the horse was simply<br />

optimism. It was, particularly since chiasmus is used (monstrum infelix, sacrata arce), representing a<br />

“criss-cross” of different emotions felt by the Trojans.<br />

Aeneas’s emotions, on the other hand, are actually more complicated they seem to be. His dismay<br />

is likely not only at the horse itself and the attack on his city, but at the inability of his countrymen to<br />

recognize the Trojan horse as a weapon. He uses very strong words like fatalis (“fatal”) (2.238), and<br />

miseri (“unfortunate”) (2.248) to indicate that this wooden horse would be the end of Troy, and the way it<br />

contradicts with the Trojans’ positive reception of the beast is a perfect way to demonstrate Aeneas’s<br />

distress at his comrades’ incognizance of the horse’s threats. In fact, his functional description of the<br />

horse and its inimical motives are reinforced when he says, “Accingunt omnes opera pedibusque rotarum<br />

subiciunt lapsus” (they all equip themselves for work and place the rollings of the wheels under their feet)<br />

(2.235-6); he uses many harsh sounds, like “c,” “p,” and “r,” in his description of the workings within the<br />

horse to demonstrate the presence of harsh, painful objects, like weapons, within the horse.<br />

Additionally, Virgil uses a technique known as apostrophe when he says, “Oh the country, oh<br />

Ilium, house of the gods!” (O patria, o divum domus Ilium) (2.241). Apostrophe is vocative admiration of<br />

something that is not there, or at least not immediately accessible. He is expressing sorrow for his fallen<br />

land, and perhaps for the people in it, just as in English we might say, “Oh unfortunate men, who didn’t<br />

know that the tiger statue was actually a real tiger.” This use of apostrophe enhances the feeling of<br />

empathy expressed for the Trojans, who not only had their city destroyed but were unaware of the dangers<br />

posed by this horse.<br />

Arguably the most all-encompassing and important section in this passage is in its last sentence,<br />

when Aeneas says, “Teucri conticuere; sopor fessos complectitur artus” (the Trojans fell silent; sleep lays<br />

hold of the tired bodies) (2.252-3). There are three possible interpretations of this phrase. It may act as a<br />

display of the Trojans’ overall adulation of the horse, as people commonly fall silent simply to take in this<br />

wonder. It may also act as a display of concern (particularly since the use of the word complectitur, or<br />

“lays over,” alludes to a growing feeling of dread): they are falling asleep, hoping that all will be better in<br />

the morning, and trying to escape the threat of this “monstrum infelix.” Finally, this may mean that the<br />

Trojans are simply tired after a long day and need to sleep.<br />

The true meaning conveyed here is a combination of all three of these. While there is clear<br />

evidence throughout the passage that the Trojans are astounded by this horse, perhaps because they think<br />

it is a Greek offer of capitulation, there is evidence that they are suspicious about what this horse truly is.<br />

And night has fallen. Particularly in literature, night is often associated with fear (most people are more<br />

afraid of doing something at night than during the day). But this night is depicted grimly. The description

of the night falling here uses words like “great shadow” combined with a reference to Ocean, a god and<br />

river in the underworld, when Aeneas says, “ruit Oceano nox involvens umbra magna” (night falls from<br />

Ocean, covering with a great shadow) (2.250-1). Additionally, when he describes how the night falls over<br />

the land and the sky and the tricks of the Myrmidons, he uses polysyndeton (terramque polumque<br />

Myrmidonumque dolos) (2.251-2). This also increases the intensity of the night, as in English we might<br />

say, “Night fell over the land, and over the sky, and over the trees” for the readers to truly realize how<br />

powerful this night is. This makes the night almost seem like an approaching death, and represents the<br />

ominous horse that is approaching them.<br />

While this description enhances Aeneas’s looking back on this event as an ambush on the wholly<br />

unsuspecting Trojans, it may also indicate that the Trojans themselves felt afraid even thought they<br />

interpreted the horse as a divine gift. When people are tired and need sleep, they are more prone to<br />

misinterpret the significant of such events as the arrival of a large wooden horse.<br />

One final thing that must be remembered is that Aeneas is relating this as a flashback: he is telling<br />

his story to the people he is currently with, just as Odysseus told his own story to the Phaiakians. As<br />

Odysseus gave the Phaiakians a detailed account of his adventures, Aeneas needs to give the<br />

Carthaginians a detailed account of his experience and also of the emotions of his comrades. His<br />

expressions of dismay represent the feelings of the Trojans who were not afraid of the horse when they<br />

learned that the horse was a weapon, and also the overriding nervousness of the Trojans who were<br />

suspicious of the horse to begin with.<br />

While it is clear that Aeneas is looking back on the event as being very regrettable, this emotion<br />

is due both to the outcome and to the inability of the Trojans to recognize the threat. Additionally, it<br />

seems as if some of the Trojans were skeptical of this horse and thought it might have been a scheme to<br />

assail them. While this may seem contradictory, this is really just a representation of Aeneas’s<br />

multifaceted nature; perhaps he has separate feelings for the skeptical and unknowing Trojans. Also, even<br />

though Aeneas has seemingly contradictory opinions on this story, he should nevertheless give all of them<br />

to make sure he covers both his character and his experiences in this flashback.<br />

#4<br />

The opposite views of Aeneas and the Trojans<br />

Although the Trojans were overjoyed, grateful, and motivated when they acquired the ligneous<br />

horse, Aeneas recalls their ill-advised acceptance of the horse with regret and sorrow. Aeneas’ portrayal<br />

of the Trojans performing several celebratory activities and various labors emphasizes their excitement<br />

and their determination to move the horse inside the city. Aeneas’ emotions, which are contrary to those<br />

experienced by the Trojans, are evident both in his overall narration of the event and in his woeful

exclamation at the heart of the passage. Enmeshed within his retelling of the Trojans’ joyous reception of<br />

the wooden horse, Aeneas’ mournful reflection on the event darkens the mood of the passage and stresses<br />

his regretful and grievous emotions.<br />

The Trojans’ determination is revealed in the very first line of this passage: Dividimus muros et<br />

moenia pandimus urbis, (Aeneid 2.234) “We divide the ramparts and open the walls of the city.” Their<br />

laboring through the tedious task of disassembling their giant walls exemplifies their determination to<br />

bring the horse into the city. In addition, his usage of “we” as the subject of this sentence shows that he<br />

has a firsthand account of the event and allows the reader to relate to the Trojans’ feelings; had Aeneas<br />

simply used “they” or “the Trojans” as the subject, his retelling of the event would not be nearly as<br />

relatable or trustworthy.<br />

Similarly, the first words of the second sentence clearly illustrate the Trojans’ universal<br />

determination to transport the horse into their city. Aeneas recounts, Accingunt omnes operi, (2.235)<br />

“Everyone equips themselves for work.” By employing the word omnes, “everyone,” Aeneas emphasizes<br />

the Trojans’ emotions; the fact that every single Trojan is involved in the work is a clear indicator of their<br />

determination. Without omnes, this phrase would be much less effective.<br />

Aeneas then lists specific tasks undertaken by the Trojans: pedibusque rotarum subiciunt lapsus,<br />

(2.235-236) “and they place rolling wheels under the feet of the horse”; stuppea vincula collo intendunt,<br />

(2.236-237) “they stretch hempen cords from its neck.” Taking the enormous size of the horse into<br />

account, these labors require abundant manpower and are extremely strenuous. Therefore, by mentioning<br />

these difficult tasks involved in bringing the horse into the city, Aeneas reemphasizes the determination of<br />

the Trojans.<br />

As indicated by this passage, the Trojans experienced not only emotions of determination, but<br />

also feelings of joy and thankfulness. Aeneas depicts their excitement when he narrates, pueri circum<br />

innuptaeque puellae sacra canunt, (2.238-239) “boys and unmarried girls sing sacred songs around the<br />

horse.” The children’s chanting of songs clearly expresses their happiness. Furthermore, as shown by the<br />

presence of sacra, “sacred,” they are not only singing but perhaps also thanking god for bestowing the<br />

horse upon them as a gift. Likewise to chanting songs, praising and thanking god portrays their gratitude<br />

and delight.<br />

Later on in the passage, their pleasure and gratefulness is again depicted: festa velamus fronde per<br />

urbem, (2.249) “we deck the gods’ temples throughout the city with festive foliage.” The action of<br />

adorning buildings with garlands illustrates their joy; choosing temples as the buildings to decorate<br />

portrays their appreciation towards the gods. Thus, Aeneas’ description of the Trojans bedecking their<br />

shrines with foliage indicates not only their pleasure but also their gratitude.

Contrary to the Trojans’ feelings when receiving the horse, Aeneas, looking back on the event,<br />

experiences regret and sorrow. His sorrow is first evident when he exclaims, O patria, o divum domus<br />

Ilium et incluta bello moenia Dardanidum, (2.241-242) “O my country, O Ilium, house of the gods, and O<br />

the Trojan walls, famous in war!” By suddenly bursting into a lamentation of the fate of his country,<br />

Aeneas exemplifies his woe. In addition, his usage of alliteration, particularly in Dardanidum, increases<br />

the pathos and sadness of his lamentation.<br />

Aeneas’ exclamation is made more impactful by the fact that he suddenly bursts into grief and<br />

lamentation in the midst of his retelling instead of keeping his woe at bay until his narration is finished.<br />

Ideally, Aeneas would be able to contain his woe and eschew interrupting his narration. His inability to<br />

hold back his sorrow and to refrain from disrupting the flow of his retelling portrays the intensity of his<br />

sadness. His need to interrupt his narration with a grievous lamentation thus magnifies his sorrow; had he<br />

restrained himself from delivering an emotional fit until he had completed his retelling, the true deepness<br />

and heaviness of his woe would not be revealed.<br />

Aeneas’ regret is exemplified when he recounts the horse’s lurching on the threshold of the gate<br />

of Troy: quater ipso limine portae substitit atque utero sonitum quater arma dedere; instamus tamen<br />

immemores caecique furore, (2.242-244), “four times it halted on the threshold of the gate and four times<br />

the weapons gave a sound from its belly; nevertheless, we press on, unmindful and blind in the frenzy.”<br />

By bemoaning that the Trojans failed to notice the sound emanating from the horse’s interior, Aeneas<br />

expresses his regret. Furthermore, Aeneas’ anaphoric repetition of quater, “four times,” stresses that a<br />

noise occurred not once, but four times. This anaphora emphasizes the Trojans’ carelessness and thus<br />

amplifies the regret currently experienced by Aeneas.<br />

Aeneas’ negative emotions are further expressed in his picturesque portrayal of night enveloping<br />

Troy. He describes, vertitur interea caelum et ruit Oceano nox involvens umbra magna terramque<br />

polumque Myrmidonumque dolos, (2.250-252), “meanwhile, the sky is turned and night, enveloping in<br />

the form of a great shadow the earth and the sky and the wiles of the Greeks, charges from the Ocean.”<br />

Aeneas’ vivid illustration of night enveloping the city and concealing the treachery of the Greeks<br />

increases the gloominess and darkness of the mood. This mood amplifies the sorrow and regret felt by<br />

Aeneas while he depicts this dark image.<br />

In the selection above, Aeneas’ sorrow and regret are also stressed by his usage of alliteration and<br />

polysyndeton. Especially noticeable in Myrmidonumque, the repetition of the “m” sound greatens the<br />

darkness and gloominess of the mood. The excessive reiteration of “que” serves the same purpose of<br />

blackening the mood; it also indicates that Aeneas is incorporating an unnecessary timesaver between his<br />

words, probably because he is struggling to formulate and articulate his thoughts. Since his inability to

speak without pausing is likely due to intense emotions, the polysyndeton therefore stresses his regret and<br />

sorrow.<br />

In conclusion, though the Trojans received the wooden horse with gratitude, joy, and<br />

determination, Aeneas recalls the event with woe and regret. The Trojans’ emotions are evident in<br />

Aeneas’ depiction of the Trojans laboriously transporting the horse into the city and his description of<br />

their celebratory rituals. Aeneas’ feelings are exemplified not only in his sudden lamentation in the<br />

middle of the passage but also in his overall retelling of the event; his emotions are further unearthed and<br />

stressed when delving deeper into his language and usage of rhetorical devices. Thus, the emotions of the<br />

Trojans when acquiring the horse and those of Aeneas when recounting the event are opposites: while the<br />

Trojans experienced glee and gratitude, Aeneas’ feelings were ones of sadness and regret.<br />

#5<br />

From Rapture to Ruin<br />

In Book 2 of the Aeneid, Vergil describes the fall of Troy through Aeneas' own words rather than<br />

those of a narrator. This is a perfect opportunity for the author to give his audience insight into both the<br />

Trojans' mindset at the time and Aeneas' opinion looking back in retrospect. By contrasting the Trojans'<br />

joyful reactions to the horse with Aeneas' mournful feelings looking back on the event, Vergil is able to<br />

create a deep sense of tragedy in an ironic situation.<br />

It is evident that Aeneas' view of the event, looking back in retrospect, is very different from that<br />

of the Trojans at the time. In the beginning of the passage, Aeneas describes how happy the Trojans are at<br />

the appearance of the horse. He says, “The boys and unmarried girls sang sacred songs around it,” (Pueri<br />

circum innuptaeque puellae sacra canunt) to show the joy of the moment (2.238-239). He uses the word<br />

innuptae, meaning “unmarried,” to describe the young girls. This word, however, does not simply have<br />

the strict meaning of “unmarried” in this context. More importantly, it implies the sheer youth and<br />

naivety of the victims who suffered from the fall of Troy and who, ironically, are celebrating its inception.<br />

At the end of the excerpt, Aeneas also tells his audience, “sleep seized our tired limbs,” (sopor fessus<br />

complectitur artus) to describe the sheer relief of the weary Trojans, which is so great that they all settle<br />

down peacefully (2.253). However, through Aeneas' narration, this short sentence becomes more sinister.<br />

Aeneas gives sleep its own character by using personification and a special verb, complectitur. This word<br />

has a dual meaning; while it can mean “embrace or hug,” it can also mean “seize or grasp.” In this way,<br />

the word seems to act as a parallel to the Trojan horse itself by at first giving the impression of being<br />

harmless when actually it is extremely disastrous, especially when placed in Aeneas' ironic interpretation<br />

of the event. Through Aeneas' description, this word gives sleep, sopor, the entirely distinct character of a<br />

specious thief in the night, robbing the Trojans of their senses and defenses, much like the Greeks

themselves. Thus, even though the Trojans are described in these examples as being happy and relieved,<br />

the audience is still given a terrible sense of foreboding.<br />

In some instances, Aeneas explicitly describes to the audience how foolish and ignorant the<br />

Trojans are, but he also explains that it isn't their fault. Aeneas says, “Nevertheless we pressed onward,<br />

forgetful and blind from our madness,” (instamus tamen immemores caecique furore) trying to explain the<br />

Trojans' behavior (2.243). He uses caeci, meaning “blind” as well as “confused and rash,” to describe the<br />

Trojans as being lost and confused, and then he blames it on their furore, or madness. This madness that<br />

affects the Trojans is not something they can help, but something sent forth by the gods. Aeneas<br />

recognizes this, along with many of the gods' other tricks which are played on the Trojans. He also says,<br />

“But the gods had ordered that no Trojan would believe (Cassandra's words),” (ora dei iussu non umquam<br />

credita Teucris) to further this point (2.247). He uses the word iussa to show that the Trojans' “madness”<br />

was not just the mere wish of the gods but their precise “order.” Through his words, the audience can<br />

clearly observe that Aeneas, while distraught and regretful about the destruction of his homeland, at the<br />

same time has also realized its inevitability.<br />

Aeneas' retrospective description of the fall of Troy employs careful wording in order to create a<br />

sense of foreboding. He says, “The night, enshrouding the ocean and the small amount of land with great<br />

shadows,” (nox involvens umbra magna terramque polumque) to convey a sense of dread (2.250-251).<br />

This image in itself is ominous, especially with the word umbra, which not only means shadow but also<br />

ghost. This haunting word gives the passage the image of not only the approaching night but also of<br />

death, something which cannot completely be conveyed in English. He creates a similar feeling in his<br />

narration of the appearance of the Trojan Horse. Aeneas says, “Four times it (the horse) halted in the very<br />

threshold of the gates,” (quarter ipso in limine portae substitit) (2.242-243). Though this short excerpt<br />

showcasing the Trojan's blind ignorance may have no affect on the modern reader, the act of stopping in<br />

an entryway was actually a very bad omen in ancient Rome. The fact that the horse did this not once, not<br />

twice, but four times echoes the events replaying over and over in Aeneas' own mind and implies to the<br />

audience his regret at not doing anything about it. By listening carefully to Aeneas' words, it is clear to<br />

the audience that his story of the fall of Troy is heavily influenced by the pain and sadness he feels inside,<br />

even when he isn't saying it explicitly.<br />

Throughout this small excerpt, Aeneas speaks of both the Trojans' reactions to the Greeks' gift<br />

and his own while looking back on the event. While he describes the Trojans as being joyful and relieved<br />

in his narration, Aeneas' specific tone and word choices still give the audience a sense of foreboding.<br />

Therefore, it is Vergil's way of detailing the story's irony and tragedy that truly shines through in his<br />

narration.

#6<br />

20/20<br />

As the phrase “hindsight is 20/20” implies, one can only grasp the full implications of a situation<br />

once it is over. The procession of the wooden horse as described in Vergil’s Aeneid provides a perfect<br />

example of this fact. At the time, the people of Troy welcome the carrier of Greeks gladly, but years<br />

later, once Troy has been burnt to the ground, Aeneas’ recollections are full of grief, gloomy irony, and<br />

apprehension.<br />

Although doubtful at first, the Trojans become convinced that the horse is harmless. As they<br />

figuratively let down their guard and cease to worry about the Greeks, they physically “split the ramparts”<br />

(dividimus muros, Aeneid, 2.234) which were their last line of defense against the enemy. Even children<br />

are allowed near the horse (pueri…puellae,2.238). With little difficulty or opposition it reaches the very<br />

heart of the city, as indicated by inlabitur (“glides,” 2.240). When the Trojans lead it to the highest and<br />

most defensible ground in the city (mediaeque…urbi, 2.240), they have given it the military advantage.<br />

Eventually, they fall asleep (sopor…artus, 2.253), further evidence of their imagined security.<br />

As they march it towards the temples, the Trojans evidently regard the horse as a gift from the<br />

gods. Sacred songs, normally sung during religious festivals are employed for this special occasion<br />

(sacra canunt, 2.239). No one ventures to touch the horse, daring only “to touch the rope”<br />

(funemque…gaudent, 2.239), indicating their respect for it as a sacred object. Since they stop it at the<br />

“consecrated citadel” (sacrata..arce, 2.245), one can assume that that is where they believe it belongs:<br />

among other sacred things. Vergil shows us their thanksgiving to the gods by adding that they “deck the<br />

shrines of the gods” (delubra deum…velamus, 2.248-249), a practice usually reserved for festa (“festive,”<br />

2.249) occasions, namely feasts of the gods.<br />

Believing that the Greeks have left for good, the Trojans also view the entrance of the horse as<br />

worth celebrating. The use of gaudent (“rejoice,” 2.239), implies that many are giddy simply to be near<br />

it. Aeneas describes the Trojan’s attitude as a “frenzy” or “madness” (furore, 2.244), an understandable<br />

response to victory and a sign of frantic rejoicing. As if in preparation for their festivities, they decorate<br />

the city (delubra deum…velamus, 2.248-249). Such flurries of activity indicate great joy at the horse’s<br />

arrival.<br />

Looking back, Aeneas remembers the event with a similar burst of emotions, though not of joy.<br />

Throughout the passage, Aeneas chooses present-tense verbs, such as dividimus, “we split” (2.234) and<br />

ruit, “it falls” (2.250), indicating that he is reliving the event as he retells it. By utilizing the plural<br />

subject, “we” (Dividimus…pandimus…velamus, 2.234, 2.249), he identifies himself a member of his<br />

story’s cast of characters. In the middle of his recollections, he interrupts himself with a lament directed<br />

towards his country, his city, and its walls (O patria…Dardanidum, 2.241-242). In this interjection,

Vergil utilizes apostrophe, addressing someone or something not present, to point out Aeneas’ distance<br />

from his homeland, thus adding to the pathos of his character. Aeneas counts himself among those “for<br />

whom that day was the last” (quibus ultimus esset ille dies, 2.248) as if to show that a part of him died<br />

when his city was destroyed.<br />

At the same time, Aeneas is also removed, seeing the celebration around the horse as morbidly<br />

ironic. The Trojans open their walls to their worst enemy, (diuidimus…Urbis, 2.234) then “equip<br />

themselves for work” (accingunt operi, 2.235), unwittingly readying themselves to bring about their own<br />

destruction. Aeneas points out the care they take to add rolling wheels under the horse’s feet (pedibusque<br />

rotarum subiciunt lapsus, 2.235), which makes the entrance even easier for the Greeks. Aeneas recalls<br />

the people rejoicing (gaudent, 2.239) over something they should have destroyed when they had the<br />

chance. Bitterly, he calls the ramparts “renowned in war” (inculata bello, 2.241), although they are no<br />

longer useful since the Trojans themselves have already divided them (dividimus muros, 2.234).<br />

Likewise, when moeni (2.252) refers to the “fortified city” of Troy, one is reminded that enemies are<br />

already waiting inside the walls. As the Trojans “deck the shrines of the gods with festive foliage”<br />

(delubra deum... festa uelamus fronde,2.248-249), Aeneas mourns that, for many, it was their final day<br />

(ultimus..dies,2.248-249), a fact worth little celebration.<br />

While Aeneas recounts his story, he also feels an uneasy sense of foreboding and dread of the<br />

inevitable. He uses the twisted imagery of a real horse to lend foreboding to the artificial one: it is led by<br />

hemp cables stretched from its neck (stuppea..intendunt, 2.236-237), it is “pregnant with weapons” (feta<br />

armis, 2.238), and “weapons gave a crash from its womb” (utero…dedere,2.243). His use of minans<br />

(2.240) could refer to the horse “towering” over the city and its inhabitants, or more aptly be construed as<br />

“threatening,” fitting Aeneas’ knowledge of what hides inside. Once the Trojans have finished their<br />

celebration, night “falls” (ruit, 2.250), a verb that can denote ruin or destruction. Aeneas knows that the<br />

night brings not only darkness but also death for the Trojans, now scattered throughout the city<br />

(fusi...Teucris, 2.247), imagery that foreshadows their scattering in flight once the city is destroyed.<br />

Finally, they fall silent in sleep (conticuere, 2.253), just as Aeneas knows many will soon be silenced in<br />

death.<br />

Aeneas’ further implies that he views the success of the horse as a result of the<br />

interference of the gods. When he calls it fatalis machina (2.237), Aeneas remembers the horse as a<br />

device of war both “fatal” and “fated,” that is, inevitable by the will of the gods. When he refers to Ilium<br />

as the home of the gods (divum domus Ilium, 2.241), Aeneas possibly indicates resentment, believing that<br />

Troy’s fall was a result of their abandonment. According to Aeneas, it should have been obvious that the<br />

horse was “unlucky” (infelix, 2.245) since it halts “four times on the threshold of the gate itself”<br />

(quarter…substitit, 2.243). Because the Romans believed tripping on the doorstep was a bad omen,

Vergil’s readers would agree that four times was enough to convince the least superstitious of men, even<br />

without the audible crash of weapons inside (sonitum...arma, 2.243). Despite such warnings, the Trojans<br />

were, including Aeneas, “heedless and blind” in their frenzy (immemores…furore, 2.244), blindness<br />

which would only be removed by the passing of time.<br />

#7<br />

A Memory of Disaster<br />

Throughout Aeneas’ description of the fall of Troy, Vergil uses several techniques to contrast the<br />

original reaction of the Trojans to Greek horse found outside their city and Aeneas’ view of the event as<br />

he looks back at the disaster that destroyed his home. These techniques include the use of the contrast<br />

between the city’s celebration and willingness to tear down their fortifications when the horse arrives and<br />

the ten years of trusting these fortifications to protect their city from the Greek invaders. Vergil also<br />

shows the irony of people’s blindness to the danger within the horse in comparison to the numerous<br />

warning they were given. Vergil uses such contrasting phrases to explain how Aeneas now views the<br />

triumphant entry of the Trojan horse.<br />

Vergil begins this passage with: Dividimus muros et moenia pandimus urbis. (Aeneid 2.234)<br />

This translates as, “We broke up the wall and spread out the fortifications of the city.” The breaking up of<br />

the city walls to make an entry for the horse symbolizes how easily the fortifications used successfully for<br />

the previous ten years are crumbled by the city’s own people. Aeneas also states: Accigunt omnes opera,<br />

or, “Everyone equipped for the work.” (2.235) Aeneas’ description of the reception of the horse shows<br />

the contrast between the initial excitement of all of the citizens to help tear down the fortifications and<br />

protection of their city and the actual outcome when he says: Scandit fatalis machine muros feta armis,<br />

or, “The fatal machine climbed the walls full of arms”. (2.237) The Greek horse accomplishes its purpose<br />

and literally breaks down all of the defenses that were keeping the Greeks out of the city. Not only is<br />

Aeneas describing the crumble of the city’s physical defenses, but the willingness of all of the citizens of<br />

Troy to aid in the destruction of the walls show that the horse also accomplished the purpose of<br />

encouraging the city to lower its guard, allowing the Greeks to slip in unnoticed. By contrasting the story<br />

of breaking up of the wall with Aeneas’ description of the dangerous horse, Vergil shows the change of<br />

view from the time of the horse’s entry into the city, and Aeneas’ new view as he looks back upon the<br />

event.<br />

Vergil also contrasts the views of the event using an ironic description of the citizens’ excited<br />

celebration at the coming of the horse into their city. Aeneas recalls: Pueri circum inuptaeque puellae<br />

sacra canunt funemque manu contigere gaudent, or, “Boys and unmarried girls chant sacred songs around<br />

it, and rejoice to touch the rope with their hands.” (2.28-239) This description of the joyful singing and

the use of the word gaudent shows the great happiness of the people as they receive the horse in the belief<br />

that the long war has finished. Not only do the people trust that this horse is harmless enough to bring<br />

into the city, but even the children are permitted to approach and touch it, showing the Trojans’ complete<br />

faith in the belief that that the Greeks have gone and that the horse is safe. Aeneas contrasts this image<br />

sharply with his new view of the event when he speaks of the horse as a fatalis machine, or fatal machine,<br />

earlier in the passage. In this passage, Vergil is using the irony of the people’s rejoicing and celebrating<br />

the arrival of the horse even as it is about to bring their destruction. Aeneas then states: Illa subit<br />

mediaeque minans inlabitur urbi, or, “This horse ascends and glides threatening into the middle of the<br />

city.” (2.250) Looking back, Aeneas bitterly recounts the foolishness of the city, and views the horse as<br />

a danger, but it is too late to save the city of Troy.<br />

Not only do the people rejoice at the arrival of the horse, but they also remain blind to the<br />

impending disaster even as they are shown signs of the horse’s true nature. While celebrating, the people<br />

were given warnings about the danger of contents of the horse as they pulled it into the city. Aeneas tells<br />

of how: Quarter ipso in limine portae substitit atque utero sonkitum quarter arma dedere, or, “Four times<br />

it stopped on the threshold of the gate and four times the arms gave sound from the belly.” (2.242-243)<br />

His view of the horse as a peaceful gift was altered only after the fall of Troy, as the Trojans chose to<br />

ignore all of the warnings they were given about the horse and what it contained. Aeneas goes on to<br />

explain that: Instamus tamen immemores caecique furore et monstrum infelix sacrata sistimus arce.<br />

(2.244-245) This portion of the passage can be translated as, “Nevertheless we pressed on forgetful and<br />

blind with frenzy, and the unlucky monster stood at the sacred alter.” Vergil moves from the lighthearted<br />

and joyful words of the original celebration of the horse’s arrival to this evidence of Aeneas’ new view of<br />

the machine as an “unlucky monster”. He also recognizes the unwillingness to heed the warnings of<br />

danger as he speaks of the Trojans’ “blind frenzy” as they bring the horse into the city and up to the<br />

sacred alter. Aeneas shows how the original danger was willingly ignored as the Trojans refused to view<br />

the Greek horse as anything that could harm the city. The current viewpoint of Aeneas in regard to the<br />

horse is then quickly revealed in his vivid description of the horse as a monster which was only brought<br />

into the city because of the blindness of the citizens to an obvious danger. He ends his account of this<br />

folly by stating: Nos delubra deum miseri, quibus ultimus esset ille dies, festa velamus fronde per urbem.<br />

(2.248-249) This can be translated as the following: “We miserable ones, for whom that day would be the<br />

final one, clothed the temples in foliage through the city.”<br />

Using the reminiscing of Aeneas, Vergil shows the major contrast between the opinions of the<br />

Trojans about the horse as it entered their city and how they viewed the huge battle machine once the plot<br />

inside was revealed and Troy had fallen. The alternating of statements about the Trojans’ joy at bringing<br />

the horse into the city and Aeneas’ descriptions of the horse as a destructive machine show both the old

and new viewpoints about the horse as well as Aeneas’ opinion concerning how the city of Troy could<br />

have been saved. Throughout Aeneas’ tale of the destruction of his city, Vergil explains how the<br />

triumphant entry of the Greek horse became a disaster for the Trojan people and how the Trojans’ idea of<br />

the nature of the horse changes from a sacred image to that of a destructive monster after the fall of the<br />

city. Using irony and contrast, Vergil chronicles this change in a way that accurately describes and<br />

compares both views.<br />

#8<br />

How the Trojans Rejoiced in Their Demise<br />

In book 2 of Virgil’s Aeneid, Aeneas gives a detailed account of the fall of Troy. During this account,<br />

Aeneas gives a description of how the Trojans joyfully received the wooden horse which would<br />

ultimately be the engine of their destruction. Throughout the passage, Aeneas switches between ecstatic<br />

mood of his people on that day and the remorse that his hindsight gives him. Through these different<br />

emotions, Virgil creates a feeling of hopelessness surrounding the Trojans, making them seem helpless<br />

victims of fate.<br />

The first use of the positive way in which Aeneas describes the reception of the horse is when he<br />

says Pueri circum innuptaeque puellae sacra canunt funemque manu contingere gaudent “Boys and<br />

virgin girls sing around the sacred thing and they rejoice to touch a rope with a hand” (Aeneid, 2.238-<br />

239). Here, Aeneas describes the innocent joy of the children of Troy in just being able to touch the ropes<br />

pulling the wooden horse. This section contrasts greatly with the preceding statement, which calls the<br />

horse fatalis machina muros feta armis “a fatal engine filled with weapons” (2.237-238). This contrast of<br />

children reaching out to touch an engine of destruction creates a tragic irony that makes the reader<br />

sympathize with the pain of Aeneas and his fellow Trojans.<br />

Aeneas continues in his description of events to say how the Trojans should have known not to<br />

trust the horse, because quater ipso in limine portae substitit, atque utero sonitum quater arma dedere<br />

“four times it stopped on the same threshold and four times the weapons in the belly gave a crash” (2.242-<br />

243). In ancient times, it was considered a bad omen to stop on the threshold, but Aeneas says instamus<br />

tamen inmemores caecique furore “nevertheless we press on heedless and blind from a frenzy” (2.244).<br />

Here we see Aeneas describe that even with the warnings of an omen and the sound of weapons crashing<br />

in the horse, the Trojans were too happy to notice their danger. We also see that Aeneas implies with the<br />

phrase caeci…furore that the Trojans could not notice their danger because a “frenzy” or “madness” had<br />

come upon them and blinded them to a truth they might have otherwise discovered. This increases the<br />

feeling that the Trojans were helpless victims of fate.<br />

Yet another instance of hindsight in the passage occurs when Aeneas states Tunc etiam fatis

aperit Cassandra futuris ora dei iussu non umquam credita Teucris “Then also Cassandra opens her<br />

mouth with fates about to be by order of a god not ever believed by Teucrians” (2.246-247). This speaks<br />

of yet another indication that the Trojans had that the horse was indeed a trap. However, Virgil indicates<br />

that again fate was against the Trojan people, since the priestess Cassandra, who could tell the future, was<br />

cursed by Apollo never to be believed until it was too late. This again serves to show that Aeneas and the<br />

other Trojans were victims of fate, with Aeneas only realizing after the Troy fell that Cassandra was right.<br />

Aeneas again shows the joy of the Trojans versus his own view as he looks back when he says<br />

nos delubra deum miseri, quibus ultimus esset ille dies, festa velamus fronde per urbem “wretched we, for<br />

whom that day was our last, clothe the temples of the gods through the city with festive foliage” (2.248-<br />

249). This indicates that the Trojans were so excited, they were getting ready for celebrations by<br />

decorating the temples with festa fronde (festive foliage). However, these festivities are contrasted with<br />

Aeneas’ description of himself and his people as miseri (wretched) and indicating that they were in their<br />

final hours. This again creates irony from the fact that the Trojans were getting ready to officially<br />

celebrate the engine that was going to cause their destruction that very night.<br />

In the final lines of the passage, Aeneas presents two very different images. The first is the<br />

ominous picture of night involvens umbra magna terramque polumque Myrmidonumque dolos “rolling in<br />

its great shadow the earth and the pole-star and the devices of the Myrmidons” (2.251-252). Here, the<br />

magna umbra (great shadow) is intended to create a feeling of foreboding as it conceals the horse, hiding<br />

the Greeks inside it. This is opposite of the lines following, which say that the people of Troy conticuere,<br />

sopor fessos complectitur artus “fell silent, weary joints grasped by sleep” (2.253). We find in this line<br />

that the people go to bed thinking nothing is wrong, able to rest without fear of war. This ideal picture and<br />

Aeneas’ foreboding earlier create a final picture of helplessness as the Trojans are unable to see a trap<br />

until it is sprung.<br />

During Aeneas’ description of the how he and his countrymen received the wooden horse left by<br />

the Greeks, he combines the feelings felt at the time with what he feels looking back on the event. At<br />

times Aeneas is describing the joy of the Trojans, but at others he is lamenting their state of affairs. By<br />

using these contrasting feelings, Virgil creates the idea that the Trojans were helpless victims who could<br />

not prevent their downfall, even though the signs of a trap were right in front of them.<br />

#9<br />

Blind to the Threats<br />

The opening word of this passage, dividimus (“we divide,” Aeneid 2.234), sets the tone for the<br />

entire passage, foreshadowing the divisive effect the wooden horse sent by the Greeks would have upon<br />

the Trojan city. The arrival of the horse forced the Trojans to decide whether they ought to allow the

unknown beast entrance to their walls, or to barricade it outside their defenses. Though most Trojans<br />

argued that the horse, which they considered a sign from Athena, must be admitted, the tension within<br />

their own ranks effectively split their city in two, far before they literally opened their defenses.<br />

Repetition further enhances the dramatic effect of this sentence: it is explained that the Trojans “divide the<br />

walls” (dividimus muros, 2.234) and “open the fortifications” (moenia pandimus, 2.234) of their city,<br />

strengthening the image of division that the arrival of the horse has created.<br />

Despite the hostility they have faced in battle, and the violence they have recently witnessed as<br />

Laocoon and his sons were attacked by snakes, most of the Trojans seem determinedly carefree, as though<br />

they were resolved to throw themselves wholeheartedly into celebration without a thought of risks or<br />

consequences. Young men and women dance around the horse (pueri...puellae, 2.238) and they even<br />

“rejoice” (gaudent, 2.239) to be allowed to partake in the celebration. The illusion of gaiety and carefree<br />

fun is a recurring theme throughout the Trojans' reception of the horse, but it hints at the darker reality<br />

just beneath the surface. The Trojans are so caught up in the present, both the gift horse and the current<br />

moment, that they fail to notice the danger that is right before them.<br />

In this section of the text, Aeneas relives the harrowing events through his retelling. This<br />

perspective shifts, however, as he is especially moved by his tale: he pauses his recount to cry out to his<br />

homeland in agony (O patria...Ilium, 2.241). Here, he changes the focus of the story from one directly in<br />

the middle of the action to someone looking back on it from a distance. He knows, as he is telling this<br />

tale, the horrible outcome that will result in the city's downfall because of the Trojans' heedlessness. This<br />

further serves to remind the reader that these events took place in the past, evoking a sense of inevitability<br />

within the passage.<br />

Troy is described as the “divine home” (divum domus, 2.241), in respect to the comforts and<br />

amenities it supplied its inhabitants. However, it is also called the “sacred citadel” (sacrata arce, 2.245),<br />

because of the many temples and altars to the gods that it contained. In Aeneas's eyes, Troy was great not<br />

only for its mortal comforts, but also for the intense devotion its inhabitants felt to the gods. Godly<br />

devotion and piety are recurring themes throughout the Aeneid, and a blind, unquestioning sense of<br />

loyalty to the gods was valued so strongly at the time that the destruction of Troy would seem even more<br />

unthinkable and tragic.<br />

Aeneas goes on to say that the great horse “stopped four times in the very threshold of the gate”<br />

(Quater...substitit, 2.242-243). Halting on the doorstep was considered to be a bad omen, but Aeneas and<br />

the reckless Trojans “press on” (instamus, 2.244). Aeneas describes the Trojans as “heedless and blind”<br />

(immemores caecique, 2.244). This creates an interesting distinction because it suggests an almost willful<br />

quality to their disregardful behavior: they seem utterly determined to bring the horse into the city. They<br />

ignored even the warning of Cassandra, a seer, but “it was the command of the gods that she was not

trusted by the Trojans at any time” (dei...Teucris, 2.247). Both the Trojans' own blindness and the gods<br />

themselves conspired to keep them from knowing the truth about the horse.<br />

#10<br />

Latin Essay <strong>#2</strong>: The Doom of The Trojans<br />

Although “Hindsight is 20/20” is one of the most overused sayings in the English language, it<br />

certainly does have its merits. In literary terms, that 20/20 hindsight most closely resembles the device<br />

called foreshadowing. In this passage, Aeneas tells the story of the Trojan people bringing the Trojan<br />

Horse into the city walls. Vergil is able to contrast the joyous emotions of the Trojans as the horse was<br />

being received with the feelings of Aeneas after Troy has been burned to the ground through imagery and<br />

word choice. Throughout the passage, he includes in the passage small details that are only knowable in<br />

hindsight and paints a poignant if somewhat ironic picture. Vergil makes is quite clear that he is a strong<br />

believer in the harsh reality of 20/20 hindsight.<br />

Imagery is a key component of this passage from the start. When Aeneas first begins to describe<br />

the Trojans’ attempts to bring the horse into the city with Dividimus muros et moenia pandimus urbis.<br />

“We (ourselves) broke the walls and we opened the barricades.” (Aeneid 2.234), the imagery leads the<br />

reader to find the irony of the situation, which has become obvious for our hero: after a decade of<br />

unsuccessful attempts by the Greeks to break into Troy, the Trojans eventually did the hard work for their<br />

greatest enemy and opened themselves up to the slaughter. As Aeneas’ somber retelling of the events<br />

continues, we see the hindsight of the Trojan leader shed some light on the mystery of the true motive of<br />

the Trojan Horse, that is, to help destroy Troy: scandit fatalis machina muros feta armis. “The deadly<br />

machine climbed over the walls, teeming with armed men.” (2.237-238). The knowledge that we have<br />

gained from Aeneas’ perspective makes the happy emotions of the “boys and unwed girls (who) sing<br />

sacred songs around it (the horse), and they are happy to touch the gift with a hand” (Pueri circum<br />

innuptaeque puellae sacra canunt funemque manu contingere gaudent) (2.238-239), turn sour in both<br />

Aeneas’ and the reader’s mouth. In a matter of hours, the entire Trojan world turns on its head, and as a<br />

result, Aeneas’ emotions regarding the horse are far different from his Trojan compatriots. As the Horse<br />

moves towards the center of the city, we continue to see that Aeneas is hit hard by the ignorance of his<br />

fellow Trojans: O patria, o divum domus Ilium et incluta bello moenia Dardanidum! “O fatherland, O<br />

home of the Trojan gods! Glorious walls of the sons of Dardan!” (2.241-242). He is still so hurt by the<br />

destruction of his city that he cannot bear to continue without screaming to his gods and homeland, a sign<br />

that his bitter and mournful emotions surrounding the circumstances of Troy’s demise highly contrast the<br />

joyous emotions of his comrades while they were bringing the Horse towards the center of Troy.<br />

Moreover, actions that seemed to be inconsequential before, such as Cassandra’s foretelling of the doom

of Troy, now seem obvious to our hero: Tunc etiam fatis aperit Cassandra futuris ora dei iussu non<br />

umquam credita Teucris. “Then also Cassandra opens her mouth to the future by the order of fate, never<br />

to be believed by the Trojans.” (2.246-247). When powerful imagery is used in conjunction with word<br />

choice, the poet is able to more eloquently convey the emotion and meaning of the scene. It is clear to the<br />

reader the depth of Aeneas’ pain that his people joyfully accepted their demise into their city.<br />

Word choice is a key tool that Vergil uses throughout this passage to strengthen the contrast<br />

between the joyfulness of the Trojans before the destruction of Troy and the soberness of Aeneas<br />

afterwards. The first example of this is the continual use of quater “four” (2.242-243) when Aeneas<br />

describes the Trojan’s attempts to bring the Trojan Horse into the city. By showing that the horse got<br />

stuck four times before entering the city, Vergil shows the reader that the horse is very unlucky and once<br />

again uses hindsight to show how doomed the Trojans were from the start. Another key example of Vergil<br />

using word choice to his advantage is when he uses umbra “veil” (2.251) to describe the night. This<br />

perfectly describes the plan of Odysseus and his comrades: they successfully use the darkness of the night<br />

to sneak out of the Trojan Horse and destroy the city that they fought for a decade. Because Aeneas is<br />

aware of what has happened to his people, his telling of the fall of Troy subtly includes clues to how Troy<br />

will fall: through deceit and treachery.<br />

There are three other key phrases where Vergil expertly contrasts Aeneas’ melancholy emotions<br />

and the Trojans’ delighted sentiments regarding the acceptance of the Trojan Horse into the city: 2.240,<br />

2.243-244, and 2.248-249. In 2.240, Vergil describes the pleasure that the Trojans show by destroying<br />

their own ramparts to let in the Trojan Horse with the somber attitude of Aeneas, as he knows what<br />

destroying the ramparts has truly done: illa subit mediaeque minans inlabitur urbi. “It threateningly<br />

moved towards the middle of our forum after it had opened the city.” (2.240) This contrast is again put on<br />

display when Aeneas explicitly laments the blind ignorance of the Trojans as they roll it towards their<br />

stronghold: instamus tamen immemores caecique furore et monstrum infelix sacrata sistimus arce. “We<br />

press on however, blinded by fury and heedless, and we bring the unlucky monster to our sacred citadel.”<br />

(2.243-244). This passage shows again to the reader that while the Trojans celebrate their “victory” over<br />

their enemy, Aeneas knows the truth: the war is over, and his then-celebrating nation has lost. The final<br />

key area where Vergil contrasts the feelings of the Trojans and Aeneas’ emotions is when Aeneas<br />

describes the celebrations throughout the city. Vergil ironically juxtaposes quibus ultimus esset ille dies<br />

“for whom it was the last day” (2.248-249) with festa velamus fronde per urbem. “We cover the buildings<br />

with leaves and conduct festivals.” (2.249), showing the reader and the listeners to Aeneas’ tale that doom<br />

is just around the corner for the Trojans.<br />

Throughout this passage, Vergil uses foreshadowing, imagery, and word choice to show the<br />

reader how the feelings of the Trojans before the Fall of Troy are vastly different from Aeneas’ emotions

following the Fall, and for good reason. Whether Aeneas is lamenting the ignored signs or the premature<br />

celebrations, the message is clear: in Aeneas’ eyes, the Trojans should not have declared victory so early,<br />

and above all, they should not have permitted the Trojan Horse to enter the city, even if it was a symbol<br />

of Athena. This passage truly shows that hindsight is 20/20; even though Aeneas has no reason to be<br />

upset with himself over what has happened to Troy, he still finds himself at fault for not correcting the<br />

mistakes the Trojans all made, so he somberly tells the story of a time when his people were filled with<br />

joy.<br />

#11<br />

A Verbal Frame<br />

This is an excerpt from Aeneas’s account of the Trojan horse. The passage is organized by the<br />

careful placement of its verbs. This framework, and its consistent use of the historical present tense make<br />

it very symmetrical. Homer uses this symmetry to help describe both Aeneas, and the Trojans in Aeneas's<br />

story.<br />

The first stanza dominates this passage and uses a more complex verb pattern than the second. Its<br />

first section only uses verbs in the first person. The second only uses verbs of the third person, and the<br />

third set of lines lacks a stated verb, but there are indications that there is an assumed second person.<br />

After that, there is another section of third person verbs, and the stanza is brought to a close by a return to<br />

the first person. Thus the verb pattern of the first stanza is: first, third, second, third, first.<br />

The different persons correlate with different perspectives and moods. When Aeneas speaks in<br />

the first person, he is looking back, grieving on the tragic event he is describing, When Aeneas uses the<br />

third person, he is more withdrawn, merely describing the actions of the Trojans at the time. In the<br />

middle section, in which there is no stated verb, the tone becomes passionate and less controlled.<br />

The very first word of the passage is Dividimus (we divide) (2.234). It introduces the use of the<br />

historical present tense that heightens the drama by including Aeneas in his story. It also introduces the<br />

first person. This again includes Aeneas in the action, and increases the pathos. Homer uses words such<br />

as miseri (wretched) (2.248) to emphasize the point that Aeneas is suffering with the retelling.<br />

In the first four lines of the passage, the verbs are first in the sentence. This puts considerable<br />

emphasis on them, and it builds suspense, since the subject is still forthcoming. For example, in line four:<br />

intendunt scandit fatalis machina muros feta armis. "They stretch; it mounts, the fateful machine filled<br />

with arms" (2.237). First, notice that Aeneas has changed to the third person, distancing himself from the<br />

action to draw attention to the horse. This is an excellent narrative device, building suspense by starting<br />

with the action of the people. Then, the nameless thing mounts. Last is the description of the fateful<br />

machine.

The center lines of the first stanza are the climax of the passage. This is emphasized by the lack<br />

of a verb, the passage breaking the preceding pattern and carrying on without an important piece of<br />