Contingency Plan for Hawaiian Monk Seal Unusual Mortality Events

Contingency Plan for Hawaiian Monk Seal Unusual Mortality Events

Contingency Plan for Hawaiian Monk Seal Unusual Mortality Events

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

4<br />

evaluations) are per<strong>for</strong>med in the field; these preliminary findings, as well as descriptions<br />

of gross lesions or clinical signs observed, are reported to the <strong>Monk</strong> <strong>Seal</strong> Assessment<br />

Program and <strong>Monk</strong> <strong>Seal</strong> Health and Disease Program. These measures increase the<br />

likelihood of timely detection of an unusual mortality event, allowing a response to be<br />

mounted within the field season if deemed appropriate.<br />

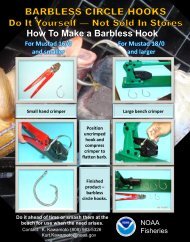

Known causes of mortality in <strong>Hawaiian</strong> monk seals include emaciation of juveniles,<br />

tiger and Galapagos shark attacks, male aggression (individual and multiple), deleterious<br />

fisheries interactions, and entanglement in marine debris (Balazs and Whittow, 1979;<br />

Kenyon, 1981; Henderson, 1985, 1990; Alcorn and Kam, 1986; Banish and Gilmartin,<br />

1992; Hiruki et al., 1993a, 1993b; Nitta and Henderson, 1993; Starfield et al., 1995).<br />

Disturbance of pregnant or nursing females likely causes them to desert preferred<br />

pupping beaches, resulting in decreased pup survival (Kenyon, 1972; Kenyon, 1981).<br />

Maximum age is believed to be 25-30 years, but few seals live this long (NMFS,<br />

unpublished data).<br />

The influence of disease on monk seal populations is not well understood, but is an<br />

active area of research (Aguirre et al., 1999; Aguirre, 2000; Appendix A, <strong>Hawaiian</strong> <strong>Monk</strong><br />

<strong>Seal</strong> Specimen Collection Protocol and Appendix B, <strong>Hawaiian</strong> <strong>Monk</strong> <strong>Seal</strong> Necropsy<br />

Protocol). Infectious and noninfectious diseases have been reported in <strong>Hawaiian</strong> monk<br />

seals but do not appear to be impeding population recovery: all wild seals carry parasites;<br />

dental and skeletal abscesses and pathology were the apparent causes of death in one<br />

aged seal; and biotoxins may pose a serious risk (Golvan, 1959; Rausch, 1969; Kenyon<br />

and Rauzon, 1977 [cited in Kenyon 1981]; DeLong, 1978; DeLong and Gilmartin, 1979;<br />

Gilmartin et al., 1980; Whittow et al., 1980; Dailey et al., 1988). Of the 15 Marine<br />

Mammal <strong>Unusual</strong> <strong>Mortality</strong> <strong>Events</strong> (UMEs) occurring in other marine mammals species<br />

since 1992 (Dierauf and Gulland, 2001: 72-73, Table 1), infectious diseases and biotoxins<br />

were the most common diagnoses (five cases each). Other factors implicated in UMEs<br />

included fisheries interactions, ship strikes, and large-scale decadal changes in oceanic<br />

productivity (Polovina et al., 1995).<br />

In a recent review of emerging and resurging diseases in marine mammals, Miller et<br />

al. (2001) describes three ways in which wildlife species may be exposed to emerging<br />

diseases (newly evolved or newly identified as pathogens), all three of which are<br />

applicable to <strong>Hawaiian</strong> monk seals. The first is exposure via spillover from domestic<br />

species or humans. Many recent reports of transmissible diseases in marine mammals<br />

have included organisms traditionally associated with domestic animals and humans<br />

(e.g.; Brucella sp., Ewalte et al., 1994; Ross et al., 1994; Jepson et al., 1994;<br />

Mycobacterium bovis and M. tuberculosis, Forshaw and Phelps, 1991; Cousins et al.,<br />

1993; Woods et al.; 1995; Bernardelli et al., 1996). The second method of exposure is via<br />

rehabilitation or translocation of animals (e.g., Stamper et al., 1998, reports the possible<br />

spread of leptospirosis from skunks to rehabilitating harbor seals). The third way that<br />

wildlife species may become exposed to emerging diseases is through the effects of<br />

environmental phenomena such as El Niño and large-scale climate change on the<br />

proliferation or spread of infectious organisms (Fauquier et al. 1998; Harvell et al., 1999;<br />

Reddy et al. 2001). Another source of exposure to infectious diseases in <strong>Hawaiian</strong> monk