A simple rule for the evolution of cooperation on graphs and social ...

A simple rule for the evolution of cooperation on graphs and social ...

A simple rule for the evolution of cooperation on graphs and social ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Vol 441|25 May 2006|doi:10.1038/nature04605<br />

LETTERS<br />

A <str<strong>on</strong>g>simple</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>rule</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>evoluti<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooperati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<strong>on</strong> <strong>graphs</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>social</strong> networks<br />

Hisashi Ohtsuki 1,2 , Christoph Hauert 2 , Erez Lieberman 2,3 & Martin A. Nowak 2<br />

A fundamental aspect <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> all biological systems is <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooperati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>.<br />

Cooperative interacti<strong>on</strong>s are required <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> many levels <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> biological<br />

organizati<strong>on</strong> ranging from single cells to groups <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> animals 1–4 .<br />

Human society is based to a large extent <strong>on</strong> mechanisms that<br />

promote <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooperati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> 5–7 . It is well known that in unstructured<br />

populati<strong>on</strong>s, natural selecti<strong>on</strong> favours defectors over cooperators.<br />

There is much current interest, however, in studying <str<strong>on</strong>g>evoluti<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>ary<br />

games in structured populati<strong>on</strong>s <strong>and</strong> <strong>on</strong> <strong>graphs</strong> 8–17 . These ef<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>ts<br />

recognize <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> fact that who-meets-whom is not r<strong>and</strong>om, but<br />

determined by spatial relati<strong>on</strong>ships or <strong>social</strong> networks 18–24 . Here<br />

we describe a surprisingly <str<strong>on</strong>g>simple</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>rule</str<strong>on</strong>g> that is a good approximati<strong>on</strong><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> all <strong>graphs</strong> that we have analysed, including cycles,<br />

spatial lattices, r<strong>and</strong>om regular <strong>graphs</strong>, r<strong>and</strong>om <strong>graphs</strong> <strong>and</strong> scalefree<br />

networks 25,26 : natural selecti<strong>on</strong> favours <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooperati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>, if <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

benefit <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> altruistic act, b, divided by <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> cost, c, exceeds <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

average number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> neighbours, k, which means b/c > k. In this<br />

case, <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooperati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> can evolve as a c<strong>on</strong>sequence <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> ‘<strong>social</strong> viscosity’<br />

even in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> absence <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> reputati<strong>on</strong> effects or strategic complexity.<br />

A cooperator is some<strong>on</strong>e who pays a cost, c, <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> ano<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r individual<br />

to receive a benefit, b. A defector pays no cost <strong>and</strong> does not distribute<br />

any benefits. In <str<strong>on</strong>g>evoluti<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>ary biology, cost <strong>and</strong> benefit are measured<br />

in terms <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> fitness. Reproducti<strong>on</strong> can be genetic or cultural. In <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

latter case, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> strategy <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> some<strong>on</strong>e who does well is imitated by<br />

o<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>rs. In an unstructured populati<strong>on</strong>, where all individuals are<br />

equally likely to interact with each o<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r, defectors have a higher<br />

average pay<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>f than unc<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>al cooperators. There<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>e, natural<br />

selecti<strong>on</strong> increases <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> relative abundance <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> defectors <strong>and</strong> drives<br />

cooperators to extincti<strong>on</strong>. These <str<strong>on</strong>g>evoluti<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>ary dynamics hold <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

deterministic setting <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> replicator equati<strong>on</strong> 27,28 <strong>and</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> stochastic<br />

game dynamics <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> finite populati<strong>on</strong>s 29 .<br />

In our model, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> players <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> an <str<strong>on</strong>g>evoluti<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>ary game occupy <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

vertices <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a graph. The edges denote links between individuals in<br />

terms <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> game dynamical interacti<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> biological reproducti<strong>on</strong>.<br />

We assume that <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> graph is fixed <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> durati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>evoluti<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>ary<br />

dynamics. C<strong>on</strong>sider a populati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> N individuals c<strong>on</strong>sisting <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

cooperators <strong>and</strong> defectors. A cooperator helps all individuals to<br />

whom it is c<strong>on</strong>nected. If a cooperator is c<strong>on</strong>nected to k o<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r<br />

individuals <strong>and</strong> i <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> those are cooperators, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>n its pay<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>f is<br />

bi 2 ck. A defector does not provide any help, <strong>and</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>re<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>e has no<br />

costs, but it can receive <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> benefit from neighbouring cooperators. If<br />

a defector is c<strong>on</strong>nected to j cooperators, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>n its pay<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>f is bj.<br />

The fitness <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> an individual is given by a c<strong>on</strong>stant term, denoting<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> baseline fitness, plus <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> pay<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>f that arises from <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> game. Str<strong>on</strong>g<br />

selecti<strong>on</strong> means that <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> pay<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>f is large compared to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> baseline<br />

fitness; weak selecti<strong>on</strong> means <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> pay<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>f is small compared to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

baseline fitness. The idea behind weak selecti<strong>on</strong> is that many different<br />

factors c<strong>on</strong>tribute to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> overall fitness <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> an individual, <strong>and</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> game<br />

under c<strong>on</strong>siderati<strong>on</strong> is just <strong>on</strong>e <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> those factors.<br />

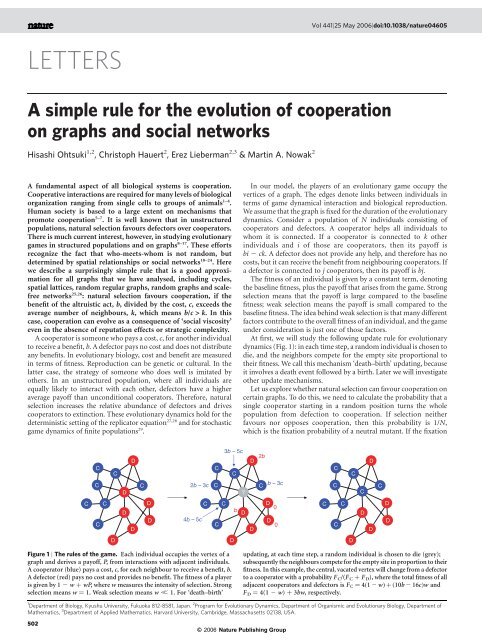

At first, we will study <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> following update <str<strong>on</strong>g>rule</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>evoluti<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>ary<br />

dynamics (Fig. 1): in each time step, a r<strong>and</strong>om individual is chosen to<br />

die, <strong>and</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> neighbors compete <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> empty site proporti<strong>on</strong>al to<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ir fitness. We call this mechanism ‘death–birth’ updating, because<br />

it involves a death event followed by a birth. Later we will investigate<br />

o<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r update mechanisms.<br />

Let us explore whe<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r natural selecti<strong>on</strong> can favour <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooperati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong><br />

certain <strong>graphs</strong>. To do this, we need to calculate <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> probability that a<br />

single cooperator starting in a r<strong>and</strong>om positi<strong>on</strong> turns <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> whole<br />

populati<strong>on</strong> from defecti<strong>on</strong> to <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooperati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>. If selecti<strong>on</strong> nei<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r<br />

favours nor opposes <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooperati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>n this probability is 1/N,<br />

which is <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> fixati<strong>on</strong> probability <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a neutral mutant. If <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> fixati<strong>on</strong><br />

Figure 1 | The <str<strong>on</strong>g>rule</str<strong>on</strong>g>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> game. Each individual occupies <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> vertex <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a<br />

graph <strong>and</strong> derives a pay<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>f, P, from interacti<strong>on</strong>s with adjacent individuals.<br />

A cooperator (blue) pays a cost, c, <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> each neighbour to receive a benefit, b.<br />

A defector (red) pays no cost <strong>and</strong> provides no benefit. The fitness <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a player<br />

is given by 1 2 w þ wP, where w measures <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> intensity <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> selecti<strong>on</strong>. Str<strong>on</strong>g<br />

selecti<strong>on</strong> means w ¼ 1. Weak selecti<strong>on</strong> means w ,, 1. For ‘death–birth’<br />

updating, at each time step, a r<strong>and</strong>om individual is chosen to die (grey);<br />

subsequently <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> neighbours compete <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> empty site in proporti<strong>on</strong> to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ir<br />

fitness. In this example, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> central, vacated vertex will change from a defector<br />

to a cooperator with a probability F C /(F C þ F D ), where <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> total fitness <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> all<br />

adjacent cooperators <strong>and</strong> defectors is F C ¼ 4ð1 2 wÞþð10b 2 16cÞw <strong>and</strong><br />

F D ¼ 4(1 2 w) þ 3bw, respectively.<br />

1 Department <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Biology, Kyushu University, Fukuoka 812-8581, Japan. 2 Program <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> Evoluti<strong>on</strong>ary Dynamics, Department <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Organismic <strong>and</strong> Evoluti<strong>on</strong>ary Biology, Department <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Ma<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>matics, 3 Department <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Applied Ma<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>matics, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138, USA.<br />

502<br />

© 2006 Nature Publishing Group

NATURE|Vol 441|25 May 2006<br />

LETTERS<br />

Figure 2 | The <str<strong>on</strong>g>simple</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>rule</str<strong>on</strong>g>, b/c > k, is in good agreement with numerical<br />

simulati<strong>on</strong>s. The parameter k denotes <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> degree <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> graph, which is<br />

given by <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> (average) number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> neighbours per individual. The first row<br />

illustrates <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> type <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> graph <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> k ¼ 2(a) <strong>and</strong> k ¼ 4(b–e). The sec<strong>on</strong>d <strong>and</strong><br />

third rows show simulati<strong>on</strong> data <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> populati<strong>on</strong> sizes N ¼ 100 <strong>and</strong> N ¼ 500.<br />

The fixati<strong>on</strong> probability, r, <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> cooperators is determined by <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> fracti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

runs where cooperators reached fixati<strong>on</strong> out <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 10 6 runs under weak<br />

selecti<strong>on</strong>, w ¼ 0.01. Each type <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> graph is simulated <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> different (average)<br />

degrees ranging from k ¼ 2tok ¼ 10. The arrows mark b/c ¼ k. The dotted<br />

horiz<strong>on</strong>tal line indicates <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> fixati<strong>on</strong> probability 1/N <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> neutral <str<strong>on</strong>g>evoluti<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>.<br />

The data suggest that b/c . k is necessary but not sufficient. The discrepancy<br />

is larger <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> n<strong>on</strong>-regular <strong>graphs</strong> (d, e) with high average degree (k ¼ 10).<br />

This is not surprising given that <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> derivati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>rule</str<strong>on</strong>g> is <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> regular<br />

<strong>graphs</strong> <strong>and</strong> in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> limit N . k. Note that <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> larger populati<strong>on</strong> size,<br />

N ¼ 500, gives better agreement. Interactive <strong>on</strong>line tutorials can be found at<br />

http://univie.ac.at/virtuallabs.<br />

probability <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a single cooperator is greater than 1/N, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>n selecti<strong>on</strong><br />

favours <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> emergence <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooperati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>. We also calculate <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> fixati<strong>on</strong><br />

probability <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a single defector in a populati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> cooperators, <strong>and</strong><br />

compare <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> two fixati<strong>on</strong> probabilities.<br />

The traditi<strong>on</strong>al well-mixed populati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>evoluti<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>ary game <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ory<br />

is represented by <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> complete graph, where all vertices are c<strong>on</strong>nected.<br />

In this special situati<strong>on</strong>, cooperators are always opposed by selecti<strong>on</strong>.<br />

This is <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> fundamental intuiti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> classical <str<strong>on</strong>g>evoluti<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>ary game<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ory. But what happens <strong>on</strong> o<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r <strong>graphs</strong>?<br />

Let us first c<strong>on</strong>sider a cycle. Each individual is linked to two<br />

neighbours. A single cooperator could be wiped out immediately or<br />

take over <strong>on</strong>e <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> its two neighbours. A cluster <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> two cooperators<br />

could exp<strong>and</strong> to three cooperators or revert to a single cooperator. In<br />

any case, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> lineage starting from <strong>on</strong>e cooperator always <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>ms a<br />

single cluster <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> cooperators, which cannot fragment into pieces. This<br />

fact allows a straight<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>ward calculati<strong>on</strong>. We find that selecti<strong>on</strong><br />

favours <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooperati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> if b/c . 2. This result holds <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> weak selecti<strong>on</strong><br />

<strong>and</strong> large populati<strong>on</strong> size.<br />

Next, we study regular <strong>graphs</strong>, where each individual has exactly k<br />

neighbours. Such <strong>graphs</strong> include cycles, spatial lattices <strong>and</strong> r<strong>and</strong>om<br />

regular <strong>graphs</strong>. For all such <strong>graphs</strong>, a direct calculati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> fixati<strong>on</strong><br />

probability is impossible, because a single invader can lead to very<br />

complicated patterns: <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> emerging cluster usually breaks into many<br />

pieces, allowing a large number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>ceivable geometric c<strong>on</strong>figurati<strong>on</strong>s.<br />

In general, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> inherent complexity <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> games <strong>on</strong> <strong>graphs</strong> makes<br />

analytical investigati<strong>on</strong>s almost always impossible.<br />

© 2006 Nature Publishing Group<br />

Never<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>less, we can calculate <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> fixati<strong>on</strong> probability <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a r<strong>and</strong>omly<br />

placed mutant <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> any two-pers<strong>on</strong>, two-strategy game <strong>on</strong> a<br />

regular graph by using pair approximati<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> diffusi<strong>on</strong> approximati<strong>on</strong><br />

(see Supplementary In<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>mati<strong>on</strong>). In particular, we find<br />

that cooperators have a fixati<strong>on</strong> probability greater than 1/N <strong>and</strong><br />

defectors have a fixati<strong>on</strong> probability less than 1/N, if:<br />

b=c . k<br />

The ratio <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> benefit to cost <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> altruistic act has to exceed <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

degree, k, which is given by <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> neighbours per individual.<br />

This c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong> is derived <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> weak selecti<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> under <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> assumpti<strong>on</strong><br />

that <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> populati<strong>on</strong> size, N, is much larger than <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> degree, k.<br />

We find excellent agreement with numerical simulati<strong>on</strong>s (Fig. 2).<br />

For a given populati<strong>on</strong> size, b/c . k is a necessary c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

selecti<strong>on</strong> to favour cooperators. As <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> populati<strong>on</strong> size increases, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

discrepancy between b/c . k <strong>and</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> numerical simulati<strong>on</strong>s becomes<br />

smaller. Moreover, we find that <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>rule</str<strong>on</strong>g> also holds <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> r<strong>and</strong>om<br />

<strong>graphs</strong> 25 <strong>and</strong> scale-free networks 26,27 , where individuals differ in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ir neighbours. Here k denotes <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> average degree <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

graph. Scale-free networks fit slightly less well than r<strong>and</strong>om <strong>graphs</strong>,<br />

presumably because <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>y have a larger variance <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> degree<br />

distributi<strong>on</strong>.<br />

The intuitive justificati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> b/c . k <str<strong>on</strong>g>rule</str<strong>on</strong>g> is illustrated in Fig. 3.<br />

C<strong>on</strong>sider <strong>on</strong>e cooperator <strong>and</strong> <strong>on</strong>e defector competing <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> an empty<br />

site. The pay<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>f <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> cooperator is P C ¼ bq CjC (k 2 1) 2 ck. The<br />

pay<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>f <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> defector is P D ¼ bq CjD (k 2 1). The c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>al<br />

503

LETTERS NATURE|Vol 441|25 May 2006<br />

Figure 3 | Some intuiti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> games <strong>on</strong> <strong>graphs</strong>. a, For death–birth updating,<br />

we must c<strong>on</strong>sider a cooperator <strong>and</strong> a defector competing <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> an empty site.<br />

The pair-approximati<strong>on</strong> calculati<strong>on</strong> shows that <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> weak selecti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

cooperator has <strong>on</strong>e more cooperator am<strong>on</strong>g its k 2 1 o<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r neighbours than<br />

does <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> defector. Hence, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> cooperator has a higher chance to win <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

empty site if b/c . k. b, For birth–death updating, we must c<strong>on</strong>sider a<br />

cooperator–defector pair competing <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> next reproducti<strong>on</strong> event. Again<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> cooperator has <strong>on</strong>e more cooperator am<strong>on</strong>g its k 2 1 o<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r neighbours<br />

than <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> defector, but <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> focal cooperator is also a neighbour <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> defector.<br />

Hence, both competitors are linked to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> same number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> cooperators, <strong>and</strong><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>re<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>e <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> defector has a higher pay<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>f. For birth–death updating,<br />

selecti<strong>on</strong> does not favour <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooperati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>. c, On a cycle (k ¼ 2), <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> situati<strong>on</strong> is<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>simple</str<strong>on</strong>g>. A direct calculati<strong>on</strong>, <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> weak selecti<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> large populati<strong>on</strong> size,<br />

leads to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> following results. For birth–death updating, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> boundary<br />

between a cluster <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> cooperators <strong>and</strong> defectors tends to move in favour <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

defectors. For death–birth updating, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> cooperator cluster exp<strong>and</strong>s if<br />

b/c . 2. For imitati<strong>on</strong> updating, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> cooperator cluster exp<strong>and</strong>s if b/c . 4.<br />

probability to find a cooperator next to a cooperator is q CjC <strong>and</strong><br />

to find a cooperator next to a defector is q CjD . The cooperator pays<br />

cost c <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> all <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> its k neighbours <strong>and</strong> receives benefit b from each<br />

cooperator am<strong>on</strong>g its k 2 1 neighbours, excluding <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>tested site.<br />

The defector pays no cost, but receives benefit b from each cooperator<br />

am<strong>on</strong>g its k 2 1 neighbours, also excluding <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>tested site. The<br />

pay<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>f that comes from <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>tested site is excluded, because it<br />

c<strong>on</strong>tributes equally to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> cooperator <strong>and</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> defector <strong>and</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>re<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>e<br />

cancels out. If P C . P D , <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>n selecti<strong>on</strong> favours <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> cooperator.<br />

Pair-approximati<strong>on</strong> shows that (k 2 1)(q CjC 2 q CjD ) ¼ 1 <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> weak<br />

selecti<strong>on</strong>. Thus, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> cooperator has <strong>on</strong> average <strong>on</strong>e more cooperator<br />

neighbour than <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> defector. There<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>e, we obtain P C 2 P D ¼ b 2 ck,<br />

which leads to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> b/c . k <str<strong>on</strong>g>rule</str<strong>on</strong>g>.<br />

We have also explored o<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r update mechanisms. Suppose at each<br />

time step a r<strong>and</strong>om individual is chosen to update its strategy; it will<br />

stay with its own strategy or imitate <strong>on</strong>e <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> neighbours proporti<strong>on</strong>al<br />

to fitness. For this ‘imitati<strong>on</strong>’ updating, we find that<br />

cooperators are favoured if b/c . k þ 2. This result can be obtained<br />

with an exact calculati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> cycle <strong>and</strong> with pair approximati<strong>on</strong><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> regular <strong>graphs</strong>. Again, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>re is good agreement with numerical<br />

simulati<strong>on</strong>s (Supplementary Fig. 4). Ma<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>matically, imitati<strong>on</strong><br />

updating can be obtained from our earlier death–birth updating by<br />

adding loops to every vertex. There<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>e, each individual is also its<br />

own neighbour. Let us define <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>nectivity, k, <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a vertex as <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

total number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> links c<strong>on</strong>nected to that vertex, noting that a loop is<br />

c<strong>on</strong>nected twice. Then <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>simple</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>rule</str<strong>on</strong>g> b/c . k holds both <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

imitati<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> death–birth updating.<br />

There are also update <str<strong>on</strong>g>rule</str<strong>on</strong>g>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> which selecti<strong>on</strong> can never favour<br />

cooperators. For example, let us c<strong>on</strong>sider ‘birth–death’ updating: at<br />

each time step an individual is selected <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> reproducti<strong>on</strong> proporti<strong>on</strong>al<br />

to fitness, <strong>and</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>fspring replaces a r<strong>and</strong>omly chosen<br />

neighbour. In this case, selecti<strong>on</strong> always favours defectors, because<br />

<strong>on</strong>ly <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> pay<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>f <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> individuals right at <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> boundary between<br />

cooperators <strong>and</strong> defectors matters, <strong>and</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>re cooperators are always<br />

at a disadvantage (Fig. 3b). In <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> two o<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r models, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> pay<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>fs <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

individuals that are <strong>on</strong>e place removed from <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> boundary also play a<br />

role, which gives <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooperati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> a chance to survive.<br />

Using a different model, van Baalen <strong>and</strong> R<strong>and</strong> 11 have derived a<br />

c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> initial invasi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> cooperators. In <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ir model, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

vertices <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a spatial lattice (or a graph) are ei<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r empty or occupied<br />

by cooperators or defectors. There are birth, death <strong>and</strong> migrati<strong>on</strong><br />

events. Implicitly, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>y have shown that without migrati<strong>on</strong> a few<br />

cooperators can successfully invade a populati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> defectors if<br />

b/c . k 2 /(k 2 1). The difference between this result <strong>and</strong> ours is<br />

not surprising. The invasi<strong>on</strong> c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> ref. 11 examines whe<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r<br />

rare cooperators are able to increase in abundance, whereas our<br />

fixati<strong>on</strong> probability includes <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> whole <str<strong>on</strong>g>evoluti<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>ary trajectory<br />

including <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> initial invasi<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> propagati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> cooperators as<br />

well as <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> final extincti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> defectors. For a comparis<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> invasi<strong>on</strong><br />

<strong>and</strong> fixati<strong>on</strong> criteria see Wild <strong>and</strong> Taylor 30 .<br />

504<br />

Thus, we have shown that <str<strong>on</strong>g>evoluti<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>ary dynamics <strong>on</strong> <strong>graphs</strong> can<br />

favour <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooperati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> over defecti<strong>on</strong> if <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> benefit to cost ratio, b/c, <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> altruistic act exceeds <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> average c<strong>on</strong>nectivity, k. The fewer<br />

c<strong>on</strong>necti<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>re are, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> easier it is <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> natural selecti<strong>on</strong> to promote<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>cooperati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>. In our present analysis, all c<strong>on</strong>necti<strong>on</strong>s are equally<br />

str<strong>on</strong>g. A next step will be to explore <strong>graphs</strong> with weighted edges. In<br />

<strong>social</strong> networks, people might have a substantial number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>necti<strong>on</strong>s,<br />

but <strong>on</strong>ly very few <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>m are str<strong>on</strong>g. Hence, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> ‘effective’<br />

average degree, k, <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> many relevant networks could be small, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>reby<br />

making selecti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooperati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>graphs</strong> a powerful opti<strong>on</strong>.<br />

Our study is <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>oretically motivated, but has implicati<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

empirical research. For example, <strong>on</strong>e can envisage an experiment<br />

where people are asked to play a n<strong>on</strong>-repeated Pris<strong>on</strong>er’s Dilemma<br />

within a given network. Certain network structures should promote<br />

cooperative behaviour more than o<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>rs. In particular, more<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>cooperati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> should emerge if c<strong>on</strong>nectivity is low. Moreover, in<br />

certain animal species <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>re exist complicated <strong>social</strong> networks.<br />

Observati<strong>on</strong>al studies could reveal how network structure affects<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> level <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooperati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>; higher c<strong>on</strong>nectivity should reduce<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>cooperati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>. In this paper, as a logical first step, we have studied<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>simple</str<strong>on</strong>g>st possible interacti<strong>on</strong> between unc<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>al cooperators<br />

<strong>and</strong> defectors, but in an extended approach, both in terms <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ory<br />

<strong>and</strong> experiment, it will be interesting to see which strategies <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> direct<br />

or indirect reciprocity evolve <strong>on</strong> particular networks.<br />

Finally, we note <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> beautiful similarity <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> our finding with<br />

Hamilt<strong>on</strong>’s <str<strong>on</strong>g>rule</str<strong>on</strong>g> 1 , which states that kin selecti<strong>on</strong> can favour<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>cooperati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> provided b/c . 1/r, where r is <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> coefficient <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> genetic<br />

relatedness between individuals. The similarity makes sense. In our<br />

framework, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> average degree <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a graph is an inverse measure <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<strong>social</strong> relatedness (or <strong>social</strong> viscosity). The fewer friends I have <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

more str<strong>on</strong>gly my fate is bound to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>irs.<br />

© 2006 Nature Publishing Group<br />

Received 7 December 2005; accepted 26 January 2006.<br />

1. Hamilt<strong>on</strong>, W. D. The genetical <str<strong>on</strong>g>evoluti<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>social</strong> behaviour. J. Theor. Biol. 7,<br />

1–-16 (1964).<br />

2. Trivers, R. The <str<strong>on</strong>g>evoluti<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> reciprocal altruism. Q. Rev. Biol. 46, 35–-57<br />

(1971).<br />

3. Axelrod, R. & Hamilt<strong>on</strong>, W. D. The <str<strong>on</strong>g>evoluti<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooperati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>. Science 211,<br />

1390–-1396 (1981).<br />

4. Wils<strong>on</strong>, E. O. Sociobiology (Harvard Univ. Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts,<br />

1975).<br />

5. Wedekind, C. & Milinski, M. Cooperati<strong>on</strong> through image scoring in humans.<br />

Science 288, 850–-852 (2000).<br />

6. Fehr, E. & Fischbacher, U. The nature <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> human altruism. Nature 425, 785–-791<br />

(2003).<br />

7. Nowak, M. A. & Sigmund, K. Evoluti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> indirect reciprocity. Nature 437,<br />

1291–-1298 (2005).<br />

8. Nowak, M. A. & May, R. M. Evoluti<strong>on</strong>ary games <strong>and</strong> spatial chaos. Nature 359,<br />

826–-829 (1992).<br />

9. Killingback, T. & Doebeli, M. Spatial <str<strong>on</strong>g>evoluti<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>ary game <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ory: Hawks <strong>and</strong><br />

Doves revisited. Proc. R. Soc. L<strong>on</strong>d. B 263, 1135–-1144 (1996).<br />

10. Nakamaru, M., Matsuda, H. & Iwasa, Y. The <str<strong>on</strong>g>evoluti<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooperati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> in a<br />

lattice-structured populati<strong>on</strong>. J. Theor. Biol. 184, 65–-81 (1997).

NATURE|Vol 441|25 May 2006<br />

LETTERS<br />

11. van Baalen, M. & R<strong>and</strong>, D. A. The unit <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> selecti<strong>on</strong> in viscous populati<strong>on</strong>s <strong>and</strong><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>evoluti<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> altruism. J. Theor. Biol. 193, 631–-648 (1998).<br />

12. Mitteldorf, J. & Wils<strong>on</strong>, D. S. Populati<strong>on</strong> viscosity <strong>and</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>evoluti<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> altruism.<br />

J. Theor. Biol. 204, 481–-496 (2000).<br />

13. Hauert, C., De M<strong>on</strong>te, S., H<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>bauer, J. & Sigmund, K. Volunteering as red queen<br />

mechanism <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooperati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> in public goods games. Science 296, 1129–-1132<br />

(2002).<br />

14. Le Galliard, J., Ferriere, R. & Dieckman, U. The adaptive dynamics <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> altruism in<br />

spatially heterogeneous populati<strong>on</strong>s. Evoluti<strong>on</strong> 57, 1–-17 (2003).<br />

15. Hauert, C. & Doebeli, M. Spatial structure <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>ten inhibits <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>evoluti<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>cooperati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> snowdrift game. Nature 428, 643–-646 (2004).<br />

16. Ifti, M., Killingback, T. & Doebeli, M. Effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> neighbourhood size <strong>and</strong><br />

c<strong>on</strong>nectivity <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> spatial c<strong>on</strong>tinuous pris<strong>on</strong>er’s dilemma. J. Theor. Biol. 231,<br />

97–-106 (2004).<br />

17. Santos, F. C. & Pacheco, J. M. Scale-free networks provide a unifying<br />

framework <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> emergence <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooperati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 098104<br />

(2005).<br />

18. Levin, S. A. & Paine, R. T. Disturbance, patch <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>mati<strong>on</strong>, <strong>and</strong> community<br />

structure. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 71, 2744–-2747 (1974).<br />

19. Durrett, R. & Levin, S. A. The importance <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> being discrete (<strong>and</strong> spatial). Theor.<br />

Popul. Biol. 46, 363–-394 (1994).<br />

20. Hassell, M. P., Comins, H. N. & May, R. M. Species coexistence <strong>and</strong><br />

self-organizing spatial dynamics. Nature 370, 290–-292 (1994).<br />

21. Skyrms, B. & Pemantle, R. A dynamic model <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>social</strong> network <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>mati<strong>on</strong>. Proc.<br />

Natl Acad. Sci. USA 97, 9340–-9346 (2000).<br />

22. Abrams<strong>on</strong>, G. & Kuperman, M. Social games in a <strong>social</strong> network. Phys. Rev. E<br />

63, 030901 (2001).<br />

23. Szabó, G. & Vukov, J. Cooperati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> volunteering <strong>and</strong> partially r<strong>and</strong>om<br />

partnership. Phys. Rev. E 69, 036107 (2004).<br />

24. Lieberman, E., Hauert, C. & Nowak, M. A. Evoluti<strong>on</strong>ary dynamics <strong>on</strong> <strong>graphs</strong>.<br />

Nature 433, 312–-316 (2005).<br />

25. Watts, D. J. & Strogatz, S. H. Collective dynamics <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> ‘small-world’ networks.<br />

Nature 393, 440–-442 (1998).<br />

26. Barabasi, A. & Albert, R. Emergence <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> scaling in r<strong>and</strong>om networks. Science<br />

286, 509–-512 (1999).<br />

27. Taylor, P. D. & J<strong>on</strong>ker, L. Evoluti<strong>on</strong>ary stable strategies <strong>and</strong> game dynamics.<br />

Math. Biosci. 40, 145–-156 (1978).<br />

28. H<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>bauer, J. & Sigmund, K. Evoluti<strong>on</strong>ary Games <strong>and</strong> Populati<strong>on</strong> Dynamics<br />

(Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, UK, 1998).<br />

29. Nowak, M. A., Sasaki, A., Taylor, C. & Fudenberg, D. Emergence <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>cooperati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>and</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>evoluti<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>ary stability in finite populati<strong>on</strong>s. Nature 428,<br />

646–-650 (2004).<br />

30. Wild, G. & Taylor, P. D. Fitness <strong>and</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>evoluti<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>ary stability in game<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>oretic models <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> finite populati<strong>on</strong>s. Proc. R. Soc. L<strong>on</strong>d. B 271, 2345–-2349<br />

(2004).<br />

Supplementary In<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>mati<strong>on</strong> is linked to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong>line versi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> paper at<br />

www.nature.com/nature.<br />

Acknowledgements Support from <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> John Templet<strong>on</strong> Foundati<strong>on</strong>, JSPS,<br />

NDSEG <strong>and</strong> Harvard-MIT HST is gratefully acknowledged. The Program <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Evoluti<strong>on</strong>ary Dynamics at Harvard University is sp<strong>on</strong>sored by Jeffrey Epstein.<br />

Author In<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>mati<strong>on</strong> Reprints <strong>and</strong> permissi<strong>on</strong>s in<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>mati<strong>on</strong> is available at<br />

npg.nature.com/reprints<strong>and</strong>permissi<strong>on</strong>s. The authors declare no competing<br />

financial interests. Corresp<strong>on</strong>dence <strong>and</strong> requests <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> materials should be<br />

addressed to M.A.N. (martin_nowak@harvard.edu).<br />

© 2006 Nature Publishing Group<br />

505

A <str<strong>on</strong>g>simple</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>rule</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>evoluti<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooperati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong><br />

<strong>graphs</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>social</strong> networks<br />

Hisashi Ohtsuki, Christoph Hauert, Erez Lieberman, Martin A. Nowak<br />

February 10, 2006<br />

Supplementary In<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>mati<strong>on</strong><br />

C<strong>on</strong>sider a game between two strategies, A <strong>and</strong> B, with <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> general pay<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>f matrix<br />

A B<br />

⎛ ⎞<br />

A a b<br />

⎝ ⎠. (1)<br />

B c d<br />

A populati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> fixed size N is distributed over <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> vertices <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a graph. All vertices <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> graph are<br />

occupied by individuals who use ei<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r strategy A or B. The pay<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>f <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> each individual is <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> sum over<br />

all interacti<strong>on</strong>s with its neighbors. Each vertex is c<strong>on</strong>nected to k o<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r vertices; this number denotes <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

degree <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> graph.<br />

We study three different update <str<strong>on</strong>g>rule</str<strong>on</strong>g>s. First, we c<strong>on</strong>sider ‘death-birth’ (DB) updating: in each time<br />

step a r<strong>and</strong>om individual is chosen to die; subsequently <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> neighbors compete <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> empty site proporti<strong>on</strong>al<br />

to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ir fitness. Sec<strong>on</strong>d, we c<strong>on</strong>sider imitati<strong>on</strong> (IM) updating: in each time step a r<strong>and</strong>om individual<br />

is chosen to evaluate its strategy; it will ei<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r stay with its own strategy or imitate a neighbor’s strategy<br />

proporti<strong>on</strong>al to fitness. Third, we c<strong>on</strong>sider ‘birth-death’ (BD) updating: in each time step an individual<br />

is chosen <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> reproducti<strong>on</strong> proporti<strong>on</strong>al to fitness; <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>fspring replaces a r<strong>and</strong>om neighbor. In an unstructured<br />

populati<strong>on</strong>, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>se three update mechanism generate almost equivalent <str<strong>on</strong>g>evoluti<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>ary dynamics,<br />

but <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> games <strong>on</strong> <strong>graphs</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>y lead to very different outcomes.<br />

Using a combinati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> pair approximati<strong>on</strong> 1 <strong>and</strong> diffusi<strong>on</strong> approximati<strong>on</strong> 2 , we derive <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> fixati<strong>on</strong><br />

probability, ρ A , which represents <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> probability that a single A player starting in a r<strong>and</strong>om positi<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> graph (with N − 1 many B players occupying <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> remaining positi<strong>on</strong>s) generates a lineage <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> A<br />

1

players that takes over <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> entire populati<strong>on</strong>. If ρ A > 1/N, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>n selecti<strong>on</strong> favors <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> fixati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> A. We<br />

can also compare <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> two fixati<strong>on</strong> probabilities, ρ A <strong>and</strong> ρ B .<br />

Having derived <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> general game, we will <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>n examine <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> fixati<strong>on</strong> probabilities,<br />

ρ C <strong>and</strong> ρ D , <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> cooperators, C, <strong>and</strong> defectors, D, in a Pris<strong>on</strong>er’s Dilemma given by <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> pay<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>f matrix<br />

C D<br />

⎛ ⎞<br />

C b − c −c<br />

⎝ ⎠.<br />

D b 0<br />

The parameters b <strong>and</strong> c denote <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> benefit <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> recipient <strong>and</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> cost <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> d<strong>on</strong>or <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> an altruistic act.<br />

For DB updating, we find that ρ C > 1/N > ρ D if b/c > k. For IM updating, we find that<br />

ρ C > 1/N > ρ D if b/c > k + 2, where k is <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> degree <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> graph. For BD updating, we obtain that<br />

ρ D > 1/N > ρ C always holds, <strong>and</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>re<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>e selecti<strong>on</strong> cannot favor <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooperati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> in this case.<br />

These results hold <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> large populati<strong>on</strong> size, N >> k, <strong>and</strong> weak selecti<strong>on</strong>. Moreover, pair approximati<strong>on</strong><br />

is <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>mulated <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> Be<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> lattices (or Cayley trees), which are regular <strong>graphs</strong> without any loops.<br />

There<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>e, some discrepancy with numerical simulati<strong>on</strong>s <strong>on</strong> <strong>graphs</strong> with loops is expected.<br />

1 ‘Death-birth’ (DB) updating<br />

Let p A <strong>and</strong> p B denote <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> frequencies <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> A <strong>and</strong> B in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> populati<strong>on</strong>. Let p AA , p AB , p BA <strong>and</strong> p BB denote<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> frequencies <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> AA, AB, BA <strong>and</strong> BB pairs. Pair approximati<strong>on</strong> means that <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> frequencies <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> larger<br />

clusters are derived from <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> frequencies <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> pair. Let q X|Y denote <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>al probability to find an<br />

X-player given that <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> adjacent node is occupied by a Y -player. Here, both X <strong>and</strong> Y st<strong>and</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> A or B.<br />

The identities<br />

p A + p B = 1<br />

q A|X + q B|X = 1<br />

(2)<br />

p XY = q X|Y · p Y<br />

p AB = p BA<br />

imply that <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> whole system can be described by <strong>on</strong>ly two variables, p A <strong>and</strong> q A|A , in pair approximati<strong>on</strong>.<br />

Each player derives a pay<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>f from interacti<strong>on</strong> with all its neighbors. At each time step, a r<strong>and</strong>om<br />

player is chosen to die. The neighbors compete <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> empty site proporti<strong>on</strong>al to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ir fitness. First we<br />

calculate <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> probabilities that <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> variables p A <strong>and</strong> p AA change during <strong>on</strong>e time step.<br />

2

1.1 Updating a B-player<br />

A B player is eliminated with probability p B . Its k neighbors compete <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> vacancy. Let k A <strong>and</strong> k B<br />

denote <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> numbers <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> A <strong>and</strong> B players am<strong>on</strong>g <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>se k neighbors. We have k A + k B = k. The frequency<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> such a c<strong>on</strong>figurati<strong>on</strong> is (k!/k A !k B !) q A|B<br />

k A<br />

q B|B<br />

k B<br />

. The fitness <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> each A-player is<br />

The fitness <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> each B-player is<br />

[<br />

]<br />

f A = (1 − w) + w (k − 1)q A|A · a + {(k − 1)q B|A + 1} · b . (3)<br />

[<br />

]<br />

f B = (1 − w) + w (k − 1)q A|B · c + {(k − 1)q B|B + 1} · d . (4)<br />

The parameter w represents <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> intensity <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> selecti<strong>on</strong>. If w = 1 <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>n <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> fitness is identical to pay<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>f;<br />

this is <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> case <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> str<strong>on</strong>g selecti<strong>on</strong>. If w

The probability that <strong>on</strong>e <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> B-players replaces <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> vacancy is given by<br />

k B g B<br />

k A g A + k B g B<br />

.<br />

The vacancy is replaced by a B-player <strong>and</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>re<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>e p A decreases by 1/N with probability<br />

(<br />

Prob ∆p A = − 1 ) ∑<br />

= p A<br />

N<br />

k A +k B =k<br />

k!<br />

k A !k B ! q A|A k A k<br />

q B<br />

k B g B<br />

B|A . (9)<br />

k A g A + k B g B<br />

Regarding pairs, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> AA-pairs decreases by k A <strong>and</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>re<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>e p AA decreases by k A /(kN/2)<br />

with probability<br />

(<br />

Prob ∆p AA = − 2k )<br />

A k!<br />

= p A<br />

kN k A !k B ! q A|A k A k<br />

q B<br />

k B g B<br />

B|A . (10)<br />

k A g A + k B g B<br />

1.3 Diffusi<strong>on</strong> approximati<strong>on</strong><br />

Let us now suppose that <strong>on</strong>e replacement event takes place in <strong>on</strong>e unit <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> time. The time derivatives <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

p A <strong>and</strong> p AA are given by<br />

<strong>and</strong><br />

ṗ AA =<br />

ṗ A = 1 N · Prob (<br />

∆p A = 1 N<br />

k∑<br />

k A =0<br />

We have used <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> notati<strong>on</strong><br />

From Eq.(12) we have<br />

) (<br />

+ − 1 ) (<br />

· Prob ∆p A = − 1 )<br />

N<br />

N<br />

= w · k − 1<br />

N p AB(I a a + I b b − I c c − I d d) + O(w 2 )<br />

2k<br />

(<br />

A<br />

kN · Prob<br />

∆p A = 2k A<br />

kN<br />

)<br />

+<br />

= 2 [<br />

]<br />

kN p AB 1 + (k − 1)(q A|B − q A|A )<br />

k∑ (<br />

k A =0<br />

− 2k A<br />

kN<br />

+ O(w).<br />

) (<br />

· Prob<br />

I a = k − 1<br />

k<br />

q A|A(q A|A + q B|B ) + 1 k q A|A,<br />

I b = k − 1<br />

k<br />

q B|A(q A|A + q B|B ) + 1 k q B|B,<br />

I c = k − 1<br />

k<br />

q A|B(q A|A + q B|B ) + 1 k q A|A,<br />

I d = k − 1<br />

k<br />

q B|B(q A|A + q B|B ) + 1 k q B|B.<br />

˙q A|A = d ( )<br />

pAA<br />

dt p A<br />

= 2 p<br />

[<br />

]<br />

AB<br />

1 + (k − 1)(q<br />

kN p A|B − q A|A ) + O(w).<br />

A<br />

∆p A = − 2k A<br />

kN<br />

)<br />

(11)<br />

(12)<br />

(13)<br />

(14)<br />

4

Remember that <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> system is described by p A <strong>and</strong> q A|A . Rewriting <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> r.h.s’s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Eq.(11) <strong>and</strong> Eq.(14)<br />

as functi<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> p A <strong>and</strong> q A|A yields <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> closed dynamical system:<br />

ṗ A = w · F 1 (p A , q A|A ) + O(w 2 ),<br />

˙q A|A = F 2 (p A , q A|A ) + O(w).<br />

(15)<br />

For weak selecti<strong>on</strong>, w k.<br />

Instead <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> studying a diffusi<strong>on</strong> process with respect to two r<strong>and</strong>om variables, p A <strong>and</strong> q A|A , we now<br />

assume, that <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> relati<strong>on</strong>ship given by Eq.(16) always holds. Hence, we study a <strong>on</strong>e dimensi<strong>on</strong>al diffusi<strong>on</strong><br />

process <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> r<strong>and</strong>om variable p A .<br />

Here<br />

Within <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> short time interval, ∆t, we have<br />

(<br />

)<br />

k − 2<br />

E[∆p A ] ≃ w ·<br />

k(k − 1)N p A(1 − p A )(αp A + β)∆t ≡ m(p A )∆t ,<br />

Var[∆p A ] ≃ 2<br />

( )<br />

k − 2<br />

N 2 k − 1 p A(1 − p A )∆t ≡ v(p A )∆t .<br />

(18)<br />

α = (k + 1)(k − 2)(a − b − c + d),<br />

β = (k + 1)a + (k 2 − k − 1)b − c − (k 2 − 1)d.<br />

(19)<br />

The fixati<strong>on</strong> probability, φ A (y) <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> strategy A with initial frequency p A (t = 0) = y, satisfies <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> following<br />

differential equati<strong>on</strong>:<br />

0 = m(y) dφ A(y)<br />

dy<br />

+ v(y) d 2 φ A (y)<br />

2 dy 2 . (20)<br />

5

Since w is very small, we have<br />

as an approximate soluti<strong>on</strong>.<br />

φ A (y) = y + w · N<br />

6k y(1 − y)[ (α + 3β) + αy ] (21)<br />

1.4 Fixati<strong>on</strong> probabilities<br />

The fixati<strong>on</strong> probability <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a single A player in a populati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> N − 1 B players is given by ρ A =<br />

φ A (1/N). For large N, we have ρ A > 1/N if <strong>and</strong> <strong>on</strong>ly if α + 3β > 0, which is equivalent to<br />

(k 2 + 2k + 1)a + (2k 2 − 2k − 1)b > (k 2 − k + 1)c + (2k 2 + k − 1)d. (22)<br />

Similarly, ρ B > 1/N is equivalent to<br />

(k 2 + 2k + 1)d + (2k 2 − 2k − 1)c > (k 2 − k + 1)b + (2k 2 + k − 1)a. (23)<br />

For k = 2, both <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> expectati<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> variance in Eq.(18) are zero. There<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>e, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> above calculati<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong>ly<br />

makes sense <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> k ≥ 3. A separate exact calculati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> cycle shows, however, that inequalities (22)<br />

<strong>and</strong> (23) also hold <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> k = 2.<br />

From Eq.(21), we can also calculate <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> ratio <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> fixati<strong>on</strong> probabilities,<br />

ρ A<br />

= 1 + w · N − 1 {(k + 1)a + (k − 1)b − (k − 1)c − (k + 1)d}. (24)<br />

ρ B 2<br />

If k ≫ 1, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>n inequality (22) leads to a + 2b > c + 2d, which is <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> 1/3 <str<strong>on</strong>g>rule</str<strong>on</strong>g> 3 . This <str<strong>on</strong>g>rule</str<strong>on</strong>g> works as<br />

follows. C<strong>on</strong>sider a game between two strategies, A <strong>and</strong> B, which are best replies to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>mselves: a > c<br />

<strong>and</strong> d > b. In this case, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> replicator equati<strong>on</strong> has an unstable equilibrium at x ∗ = (d−b)/(a−b−c+d)<br />

denoting <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> frequency <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> A. If x ∗ < 1/3, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>n in an unstructured populati<strong>on</strong> (described by a complete<br />

graph) <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> fixati<strong>on</strong> probability ρ A will be greater than 1/N <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> weak selecti<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> sufficiently large<br />

populati<strong>on</strong> size, N. The calculati<strong>on</strong> shown here has extended <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> 1/3 <str<strong>on</strong>g>rule</str<strong>on</strong>g> to any <strong>graphs</strong> with sufficiently<br />

large N.<br />

6

1.5 The <str<strong>on</strong>g>rule</str<strong>on</strong>g> b/c > k<br />

Let us now c<strong>on</strong>sider a game between cooperators, C, <strong>and</strong> defectors, D. The benefit <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooperati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> is b<br />

<strong>and</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> cost is c. The pay<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>f matrix takes <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>m<br />

A<br />

⎛<br />

B<br />

⎞<br />

A a<br />

⎝<br />

b<br />

⎠ →<br />

B c d<br />

C D<br />

⎛ ⎞<br />

C b − c −c<br />

⎝ ⎠. (25)<br />

D b 0<br />

Substituting those pay<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>f values into inequalities (22) <strong>and</strong> (23) leads to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>clusi<strong>on</strong> that if b/c > k<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>n ρ C > 1/N > ρ D . Vice versa, we have if b/c < k <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>n ρ C < 1/N < ρ D . There<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>e, <str<strong>on</strong>g>cooperati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> is<br />

favored (<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> weak selecti<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> large populati<strong>on</strong> size) if <strong>and</strong> <strong>on</strong>ly if<br />

b/c > k. (26)<br />

2 Imitati<strong>on</strong> (IM) updating<br />

Let us now study a different update <str<strong>on</strong>g>rule</str<strong>on</strong>g>. In any <strong>on</strong>e time step, a r<strong>and</strong>om individual is chosen to compare<br />

its pay<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>f with those <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> its neighbors. The individual stays with its own strategy or imitates a neighbor’s<br />

strategy proporti<strong>on</strong>al to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> pay<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>f. In c<strong>on</strong>trast to ‘death-birth’ (DB) updating, here <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> pay<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>f <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

individual that is being updated also matters. We expect that this effect will introduce an advantage <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

defectors, because defectors at <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> boundary <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a cluster have a higher pay<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>f than cooperators at <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

boundary <strong>and</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>re<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>e defectors are less likely to change <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ir strategy.<br />

The fitness <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a B-player with k A many A-players <strong>and</strong> k B many B-players in its neighborhood is<br />

given by<br />

The probability that <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> B player will adopt strategy A is given by<br />

f 0 = 1 − w + w(k A c + k B d). (27)<br />

k A f A<br />

k A f A + k B f B + f 0<br />

.<br />

The fitness <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> an A-player with k A many A-players <strong>and</strong> k B many B-players in its neighborhood is<br />

given by<br />

g 0 = 1 − w + w(k A a + k B b). (28)<br />

7