2004 ATS/ERS Definition - Pulmonary, Critical Care & Sleep Medicine

2004 ATS/ERS Definition - Pulmonary, Critical Care & Sleep Medicine 2004 ATS/ERS Definition - Pulmonary, Critical Care & Sleep Medicine

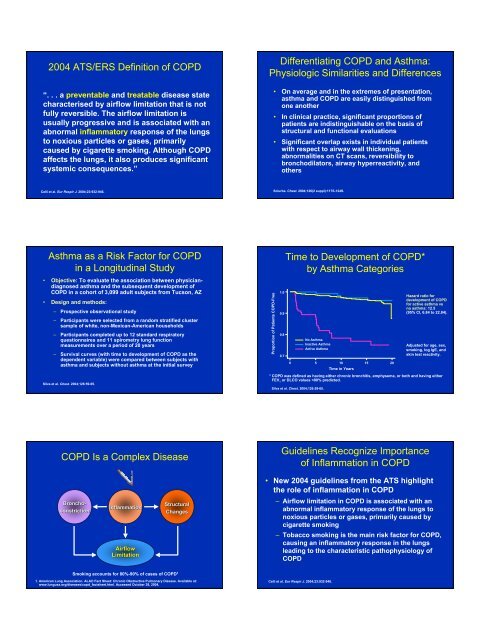

2004 ATS/ERS Definition of COPD “. . . a preventable and treatable disease state characterised by airflow limitation that is not fully reversible. The airflow limitation is usually progressive and is associated with an abnormal inflammatory response of the lungs to noxious particles or gases, primarily caused by cigarette smoking. Although COPD affects the lungs, it also produces significant systemic consequences.” Differentiating COPD and Asthma: Physiologic Similarities and Differences • On average and in the extremes of presentation, asthma and COPD are easily distinguished from one another • In clinical practice, significant proportions of patients are indistinguishable on the basis of structural and functional evaluations • Significant overlap exists in individual patients with respect to airway wall thickening, abnormalities on CT scans, reversibility to bronchodilators, airway hyperreactivity, and others Celli et al. Eur Respir J. 2004;23:932-946. Sciurba. Chest. 2004;126(2 suppl):117S-124S. Asthma as a Risk Factor for COPD in a Longitudinal Study • Objective: To evaluate the association between physiciandiagnosed asthma and the subsequent development of COPD in a cohort of 3,099 adult subjects from Tucson, AZ • Design and methods: – Prospective observational study – Participants were selected from a random stratified cluster sample of white, non-Mexican-American households – Participants completed up to 12 standard respiratory questionnaires and 11 spirometry lung function measurements over a period of 20 years – Survival curves (with time to development of COPD as the dependent variable) were compared between subjects with asthma and subjects without asthma at the initial survey Silva et al. Chest. 2004;126:59-65. Proportion of Patients COPD-Free 1.0 0.9 0.8 0.7 Time to Development of COPD* by Asthma Categories No Asthma Inactive Asthma Active Asthma 0 5 10 15 20 Time in Years Silva et al. Chest. 2004;126:59-65. Hazard ratio for development of COPD for active asthma vs no asthma: 12.5 (95% CI, 6.84 to 22.84). Adjusted for age, sex, smoking, log IgE, and skin test reactivity. * COPD was defined as having either chronic bronchitis, emphysema, or both and having either FEV 1 or DLCO values

- Page 2 and 3: Inflammation in COPD Inflammatory C

- Page 4 and 5: “NETT Lung Transplant and New Pha

- Page 6 and 7: Tiotropium • New-generation antic

- Page 8 and 9: ∆ FEV 1 (mL) 200 150 100 50 0 Sup

- Page 10: What do improvements in health stat

<strong>2004</strong> <strong>ATS</strong>/<strong>ERS</strong> <strong>Definition</strong> of COPD<br />

“. . . a preventable and treatable disease state<br />

characterised by airflow limitation that is not<br />

fully reversible. The airflow limitation is<br />

usually progressive and is associated with an<br />

abnormal inflammatory response of the lungs<br />

to noxious particles or gases, primarily<br />

caused by cigarette smoking. Although COPD<br />

affects the lungs, it also produces significant<br />

systemic consequences.”<br />

Differentiating COPD and Asthma:<br />

Physiologic Similarities and Differences<br />

• On average and in the extremes of presentation,<br />

asthma and COPD are easily distinguished from<br />

one another<br />

• In clinical practice, significant proportions of<br />

patients are indistinguishable on the basis of<br />

structural and functional evaluations<br />

• Significant overlap exists in individual patients<br />

with respect to airway wall thickening,<br />

abnormalities on CT scans, reversibility to<br />

bronchodilators, airway hyperreactivity, and<br />

others<br />

Celli et al. Eur Respir J. <strong>2004</strong>;23:932-946.<br />

Sciurba. Chest. <strong>2004</strong>;126(2 suppl):117S-124S.<br />

Asthma as a Risk Factor for COPD<br />

in a Longitudinal Study<br />

• Objective: To evaluate the association between physiciandiagnosed<br />

asthma and the subsequent development of<br />

COPD in a cohort of 3,099 adult subjects from Tucson, AZ<br />

• Design and methods:<br />

– Prospective observational study<br />

– Participants were selected from a random stratified cluster<br />

sample of white, non-Mexican-American households<br />

– Participants completed up to 12 standard respiratory<br />

questionnaires and 11 spirometry lung function<br />

measurements over a period of 20 years<br />

– Survival curves (with time to development of COPD as the<br />

dependent variable) were compared between subjects with<br />

asthma and subjects without asthma at the initial survey<br />

Silva et al. Chest. <strong>2004</strong>;126:59-65.<br />

Proportion of Patients COPD-Free<br />

1.0<br />

0.9<br />

0.8<br />

0.7<br />

Time to Development of COPD*<br />

by Asthma Categories<br />

No Asthma<br />

Inactive Asthma<br />

Active Asthma<br />

0 5 10 15 20<br />

Time in Years<br />

Silva et al. Chest. <strong>2004</strong>;126:59-65.<br />

Hazard ratio for<br />

development of COPD<br />

for active asthma vs<br />

no asthma: 12.5<br />

(95% CI, 6.84 to 22.84).<br />

Adjusted for age, sex,<br />

smoking, log IgE, and<br />

skin test reactivity.<br />

* COPD was defined as having either chronic bronchitis, emphysema, or both and having either<br />

FEV 1 or DLCO values

Inflammation in COPD<br />

Inflammatory Cells in Subjects<br />

Not Currently Smoking:<br />

Methods<br />

• Objective: Assess the differences in<br />

inflammatory parameters between subjects<br />

with COPD and healthy volunteers<br />

• Sputum induction and bronchoscopy with<br />

BAL and biopsies were performed<br />

• Subjects<br />

– 18 patients with COPD (according to <strong>ATS</strong> criteria)<br />

• 16 had chronic bronchitis<br />

– 11 healthy controls (matched for age and pack-years)<br />

Transverse section of a small airway showing<br />

peribronchiolitis consisting predominantly of lymphocytes<br />

Jeffery. Am J Respir Crit <strong>Care</strong> Med. 2001;164:S28-S38. Official journal of the American Thoracic Society.<br />

©American Lung Association. Reprinted with permission.<br />

Rutgers et al. Thorax. 2000;55:12-18.<br />

Inflammatory Cells in Subjects<br />

Not Currently Smoking:<br />

Methods (cont’d)<br />

• Inclusion criteria<br />

– Impaired lung function in COPD patients<br />

– Negative history of atopy, negative skin tests to<br />

18 common aeroallergens, negative specific<br />

serum IgE for 11 common aeroallergens<br />

– Not current smokers<br />

• 4 subjects with COPD were never smokers<br />

• All other subjects, including healthy controls, had quit<br />

smoking >1 year before study entry<br />

• Inhaled steroids were discontinued<br />

≥1 month before study entry<br />

Rutgers et al. Thorax. 2000;55:12-18.<br />

Sputum Neutrophils (%)<br />

100<br />

90<br />

80<br />

70<br />

60<br />

50<br />

40<br />

30<br />

20<br />

10<br />

0<br />

Inflammatory Cells in Subjects<br />

Not Currently Smoking<br />

Neutrophils<br />

P=0.0001<br />

Values are expressed as percentages of the total number of nonsquamous cells.<br />

* The role of eosinophils in COPD is not well defined.<br />

Rutgers et al. Thorax. 2000;55:12-18.<br />

Lymphocytes<br />

P=0.0161<br />

Eosinophils*<br />

P=0.0083<br />

10<br />

8<br />

6<br />

4<br />

2<br />

0<br />

Sputum Lymphocytes<br />

and Eosinophils (%)<br />

Patients with COPD<br />

Healthy controls<br />

Inflammatory Cells in<br />

Various GOLD Stages of COPD:<br />

Study Design<br />

Inflammatory Cells in<br />

Various GOLD Stages of COPD:<br />

Baseline Characteristics<br />

• Objective: Evaluate the relationship between progression of<br />

COPD (as reflected by GOLD stage) and the pathological<br />

findings in airways

Association Between Total Airway<br />

Wall Thickness and FEV 1<br />

V:SA (mm)<br />

0.25<br />

0.20<br />

0.15<br />

0.10<br />

0.05<br />

GOLD<br />

Stage 4<br />

GOLD GOLD<br />

Stage 3 Stage 2<br />

GOLD<br />

Stages 0 & 1<br />

0.00<br />

0 20 40 60 80 100 120<br />

Small Airway Obstruction in COPD<br />

• Progression of COPD was strongly<br />

associated with increased volume of tissue<br />

in the wall (P

“NETT Lung Transplant and New<br />

Pharmaceuticals for COPD”<br />

James F. Donohue, MD<br />

Professor of <strong>Medicine</strong><br />

&<br />

Chief, Division of <strong>Pulmonary</strong> & <strong>Critical</strong> <strong>Care</strong> <strong>Medicine</strong><br />

University of North Carolina School of <strong>Medicine</strong><br />

At<br />

Chapel Hill, North Carolina<br />

Number of Transplants<br />

1800<br />

1600<br />

1400<br />

1200<br />

1000<br />

800<br />

600<br />

400<br />

200<br />

0<br />

NUMBER OF LUNG TRANSPLANTS REPORTED<br />

BY YEAR AND PROCEDURE TYPE<br />

Bilateral/Double Lung<br />

Single Lung<br />

408<br />

185<br />

13 15 47 80<br />

685<br />

902<br />

1417 1508 1537<br />

14131410<br />

1342 1337<br />

1206<br />

1069<br />

1985<br />

1986<br />

1987<br />

1988<br />

1989<br />

1990<br />

1991<br />

1992<br />

1993<br />

1994<br />

1995<br />

1996<br />

1997<br />

1998<br />

1999<br />

2000<br />

2001<br />

ADULT LUNG TRANSPLANTATION: Indications (1/1995-6/2002)<br />

DIAGNOSIS<br />

SLT (N = 5,000)<br />

BLT (N = 4,488)<br />

TOTAL (N = 9,488)<br />

LUNG TRANSPLANTATION<br />

Actuarial Survival (Transplants: January 1990 - June 2001)<br />

COPD/Emphysema<br />

IPF<br />

CF<br />

Alpha-1<br />

PPH<br />

Sarcoidosis<br />

Bronchiectasis<br />

Congenital Heart Disease<br />

LAM<br />

Re-TX: OB<br />

OB (Non-ReTX)<br />

Re-TX: Non-OB<br />

Connective Tissue Disorder<br />

Cancer<br />

2,698 ( 54.0% )<br />

1,186 ( 24.0% )<br />

49 ( 1.0% )<br />

429 ( 8.6% )<br />

66 ( 1.3% )<br />

127 ( 2.5% )<br />

11 ( 0.2% )<br />

10 ( 0.2% )<br />

45 ( 0.9% )<br />

47 ( 0.9% )<br />

30 ( 0.6% )<br />

35 ( 0.7% )<br />

21 ( 0.4% )<br />

3 ( 0.1% )<br />

1,000 ( 22.0% )<br />

403 ( 9.0% )<br />

1,447 ( 32.0% )<br />

434 ( 9.7% )<br />

361 ( 8.0% )<br />

113 ( 2.5% )<br />

192 ( 4.3% )<br />

99 ( 2.2% )<br />

58 ( 1.3% )<br />

47 ( 1.0% )<br />

52 ( 1.2% )<br />

37 ( 0.8% )<br />

22 ( 0.5% )<br />

25 ( 0.6% )<br />

3,698 ( 39.0% )<br />

1,589 ( 17.0% )<br />

1,496 ( 16.0% )<br />

863 ( 9.1% )<br />

427 ( 4.5% )<br />

240 ( 2.5% )<br />

203 ( 2.1% )<br />

109 ( 1.1% )<br />

103 ( 1.1% )<br />

94 ( 1.0% )<br />

82 ( 0.9% )<br />

72 ( 0.8% )<br />

43 ( 0.5% )<br />

28 ( 0.3% )<br />

Survival (%)<br />

100<br />

80<br />

60<br />

40<br />

20<br />

0<br />

Double lung: 1/2-life = 4.8 Years; Conditional 1/2-life = 8.1 Years<br />

Single lung: 1/2-life = 3.7 Years; Conditional 1/2-life = 5.8 Years<br />

All lungs: 1/2-life = 4.0 Years; Conditional 1/2-life = 6.5 Years<br />

Bilateral/Double Lung (N=6,068)<br />

Single Lung<br />

(N=7,385)<br />

All Lungs<br />

(N=13,453)<br />

p < 0.0001<br />

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12<br />

Years<br />

Histiocytosis X<br />

11 ( 0.2% )<br />

8 ( 0.2% )<br />

19 ( 0.2% )<br />

Other<br />

232 ( 4.6% )<br />

190 ( 4.2% )<br />

422 ( 4.4% )<br />

Smoking Cessation in<br />

Patients with COPD: Results<br />

Rates of Continuous Abstinence from Smoking<br />

Proportion of Patients Abstinent (%)<br />

35<br />

30<br />

25<br />

20<br />

15<br />

10<br />

5<br />

0<br />

Bupropion SR<br />

Placebo<br />

0 5 6 7 10 12 26<br />

Study Week<br />

*P < .05.<br />

Tashkin DP et al. Lancet. 2001;357:1571-1575.<br />

*<br />

* *<br />

*<br />

*<br />

*<br />

(cont)<br />

Mean FEV 1 (L)<br />

2.80<br />

2.75<br />

2.70<br />

2.65<br />

2.60<br />

2.55<br />

2.50<br />

2.45<br />

Lung Health Study: Results<br />

Mean Postbronchodilator FEV 1<br />

for All Participants<br />

SIP<br />

SI + Ipratropium<br />

UC<br />

Follow-Up (Years)<br />

Anthonisen NR et al. JAMA. 1994;272:1497-1505.<br />

Postbronchodilator FEV 1 (L)<br />

Mean Postbronchodilator FEV 1<br />

for Sustained Quitters and<br />

Continuous Smokers Receiving<br />

Smoking Intervention and Placebo<br />

2.9<br />

2.8<br />

2.7<br />

2.6<br />

2.5<br />

Sustained Quitters<br />

Continuing Smokers<br />

2.4<br />

Screen 2 1 2 3 4 5 Screen 2 1 2 3 4 5<br />

Follow-Up (Years)

Effect of Smoking Cessation on the<br />

Lung Function of Participants<br />

in the LHS: Results<br />

• Women who quit had a larger improvement in the first year<br />

compared with men<br />

• Women who continued to smoke had a greater loss of function<br />

than men with comparable smoking rates<br />

• Heavy smokers benefited from quitting more than light smokers<br />

• Baseline respiratory symptoms did not predict change in lung<br />

function<br />

Patients at High Risk of Death After<br />

LVRS: Early NETT Results<br />

• 1033 patients randomized by June 2001<br />

– 69 high-risk patients<br />

• FEV 1 ≤ 20% predicted and either a homogeneous<br />

distribution of emphysema on computed<br />

tomography or a carbon monoxide diffusing<br />

capacity ≤ 20% of predicted<br />

• Among high-risk patients<br />

– 30-day mortality after surgery was 16% vs 0%<br />

among medically treated patients<br />

– Overall mortality 0.43 deaths per person-year vs<br />

0.11 among medically treated patients<br />

Scanlon PD et al. Am J Respir Crit <strong>Care</strong> Med. 2000;161:381-390.<br />

(cont)<br />

National Emphysema Treatment Trial Research Group. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1075-1083.<br />

(cont)<br />

LVRS: National Emphysema<br />

Treatment Trial<br />

Results<br />

Probability of Death<br />

0.7<br />

0.6<br />

0.5<br />

0.4<br />

0.3<br />

0.2<br />

0.1<br />

Medical Therapy<br />

Surgery<br />

0.0<br />

0 12 24 36 48 60<br />

Months After Randomization<br />

P = .90.<br />

(cont)<br />

Overall mortality rate = 0.11 deaths per person-year in both treatment groups.<br />

National Emphysema Treatment Trial Research Group. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2059-2073.<br />

Patients (%)<br />

40<br />

35<br />

30<br />

25<br />

20<br />

15<br />

10<br />

5<br />

0<br />

LVRS: National Emphysema<br />

Treatment Trial<br />

Results<br />

Improvement in Exercise Capacity at 24 Months<br />

LVRS<br />

Medical<br />

Therapy<br />

*<br />

All patients<br />

*<br />

Low EC High EC Low EC High EC<br />

Predominantly Upper-<br />

Lobe Emphysema<br />

*<br />

Predominantly Non–Upper-<br />

Lobe Emphysema<br />

EC = exercise capacity.<br />

(cont)<br />

*P < .05 vs medical therapy.<br />

National Emphysema Treatment Trial Research Group. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2059-2073.<br />

LVRS: National Emphysema<br />

Treatment Trial<br />

Conclusions<br />

• Overall, LVRS increases the chance of improved exercise capacity, lung function,<br />

dyspnea, and quality of life but does not confer survival advantage vs medical<br />

therapy alone<br />

• Poor candidates for LVRS include<br />

– High-risk patients (ie, those with FEV 1 ≤ 20% predicted and either<br />

homogenous emphysema or carbon monoxide diffusing capacity ≤ 20%<br />

predicted)<br />

– Patients with non–upper-lobe emphysema and high baseline exercise<br />

capacity<br />

• Good candidates for LVRS include patients with predominantly upper-lobe<br />

emphysema and low baseline exercise capacity<br />

National Emphysema Treatment Trial Research Group. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2059-2073.<br />

Novel and Future Therapies for COPD<br />

Products in Late-Phase<br />

Development<br />

• Bronchodilators<br />

– Tiotropium<br />

– (R,R)-formoterol<br />

• Phosphodiesterase-4 (PDE4)<br />

inhibitors<br />

– Roflumilast<br />

– Cilomilast<br />

• Combination therapy<br />

– Fluticasone + salmeterol<br />

– Budesonide + formoterol<br />

Products in Early-Phase<br />

Development<br />

• Inflammatory mediators<br />

– Inhibitors of<br />

leukotriene B4,<br />

interleukin-8, and<br />

related chemokines<br />

– Anti–TNF-α agents<br />

• Antioxidants<br />

• Antiproteases<br />

• Retinoids

Tiotropium<br />

• New-generation anticholinergic agent<br />

• Structurally related to ipratropium bromide<br />

• Slow dissociation from the muscarinic M 3 receptor<br />

found on bronchial smooth muscle<br />

• Long duration of action (≈ 24 hours)<br />

• Inhaled as a dry powder<br />

• Suggested first-line maintenance therapy in GOLD<br />

guidelines (stages II-IV)<br />

Tiotropium vs Salmeterol:<br />

Study Objective and Design<br />

• Objective: to compare the efficacy and safety of tiotropium with<br />

salmeterol<br />

• Design: randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, double-dummy,<br />

parallel group study<br />

• 623 patients were randomized to either<br />

– Tiotropium 18 µg q.d.<br />

– Salmeterol 50 µg b.i.d.<br />

– Placebo<br />

• Patients were followed for 6 months<br />

Barnes PJ. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2001;10:733-740.<br />

Pauwels RA et al. Available at: http://www.goldcopd.com. Accessed July 15, 2003.<br />

Donohue JF et al. Chest. 2002;122:47-55.<br />

Tiotropium vs Salmeterol: Results<br />

Mean FEV 1 Before and After Administration of<br />

Study Drug<br />

FEV 1 (L)<br />

1.35<br />

1.30<br />

1.25<br />

1.20<br />

1.15<br />

1.10<br />

Donohue JF et al. Chest. 2002;122:47-55.<br />

Tiotropium (n = 202)<br />

Salmeterol (n = 203)<br />

1.05<br />

Day 1<br />

Placebo (n = 179)<br />

1.00<br />

Day 15<br />

Day 169<br />

0.95<br />

-1 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12<br />

Time After Administration (Hours)<br />

(cont)<br />

Tiotropium vs Salmeterol: Results<br />

Mean SGRQ Total Score<br />

SGRQ Total Score<br />

47<br />

Salmeterol (n = 187)<br />

46<br />

Placebo (n = 159)<br />

Tiotropium (n = 186)<br />

45<br />

44<br />

43<br />

42<br />

41<br />

40<br />

0 57 113 169<br />

Test Day<br />

SGRQ = St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire.<br />

P < .05 for tiotropium vs placebo. Salmeterol vs placebo is not significant. Tiotropium vs<br />

salmeterol is not significant.<br />

Donohue JF et al. Chest. 2002;122:47-55.<br />

Improvement<br />

(cont)<br />

Oral Steroids – Effects on lung function<br />

in acute COPD exacerbation<br />

Forest Plot Showing the Effect of Estimate of Each<br />

Study and Respective 95% Cls<br />

1) Aaron – N Engl J Med 2003<br />

Study (Reference)<br />

Patients, n<br />

Study (Reference)<br />

147 patients in ED – 10 days of oral Prednisone 40mg<br />

-lower relapse<br />

-Increase in FEV 1 34% vs 15% or 0.30liters vs 0.16L with<br />

placebo<br />

Vestbo et al (3)<br />

Weir et al (9)<br />

Pauwels et al (6)<br />

Lung Health Study<br />

Research Group (7)<br />

Renkema et al (10)<br />

290<br />

98<br />

1277<br />

1116<br />

39<br />

3.1 ± 11.4 (-12.8 to 19.0)<br />

-36.3 ± 22.6 (-80.6 to 8.0)<br />

-12.0 ± 14.0 (-39.4 to 15.4)<br />

-2.8 ± 4.03 (-11.0 to 5.4)<br />

-30.0 ± 93.8 (-213.8 to 153.8)<br />

2) Scope Trial<br />

Burge et al (8)<br />

751<br />

-9.0 ± 6.38 (-21.5 to 3.5)<br />

Niewoehner – N Engl J Med 1999<br />

-active treatment – FEV 1 increases 100ml within 24 hours<br />

3) Davies – Lancet 1999<br />

Total 3571<br />

-5.0 ± 3.2 (-11.2 to 1.2)<br />

-300 -200 -100 0 100 200 300<br />

Difference Between Placebo and Treatment Groups in FEV 1 , Decline mL/y

Effect of FP in COPD<br />

• ISOLDE – Run in – Fall of FEV 1 of 75ml on ICS –<br />

89ml FEV 1 fall – not on ICS 47ml<br />

• Oral steroides – 60ml increase in FEV 1<br />

• Rate of decline – 59 verses 50ml<br />

• At 3 and 6 months – 76ml and 100ml higher<br />

• At all points FEV 1 70ml higher with FP<br />

• No relationship to oral CS<br />

Exacerbation in COPD<br />

• Associated with mortality<br />

• Multiple causes – infections, irritants<br />

• Defining event<br />

• Costly – drugs, hospital, loss<br />

• Correlates with Hs QOL<br />

Reduced Risk of Mortality and Repeat<br />

Hospitalization with Inhaled<br />

Corticosteroids<br />

COPD Hospitalization Free Survival<br />

1.0<br />

0.9<br />

0.8<br />

0.7<br />

0.6<br />

No Inhaled Corticosteroids<br />

Inhaled Corticosteroids<br />

0.5<br />

0 2 4 6 8 10 12<br />

Months After Discharge<br />

ICS associated with a 26% lower<br />

relative risk for all-cause mortality<br />

and repeat hospitalization<br />

FP Reduces Median Annual Exacerbation<br />

Rate: ISOLDE Study<br />

Exacerbations/patient/year<br />

1.4<br />

1.2<br />

1<br />

0.8<br />

0.6<br />

0.4<br />

0.2<br />

0<br />

1.3<br />

2<br />

Placebo<br />

O.99*<br />

Fluticasone 500mcg<br />

BID<br />

*p=0.026<br />

Adapted from Sin DD, Tu JV. Am J Respir Crit <strong>Care</strong> Med 2001;164:580-584<br />

Burge PS et al. Br Med J. 2000;320:1297-1303<br />

Study Design<br />

ADVAIR 250/50 mcg b.i.d.<br />

p.r.n.<br />

albuterol<br />

Placebo<br />

run-in<br />

Fluticasone propionate 250 mcg b.i.d.<br />

Salmeterol 50 mcg b.i.d.<br />

Placebo b.i.d.<br />

2 weeks<br />

24 weeks<br />

All treatments administered via the DISKUS ® device.<br />

Patients were stratified based on reversibility to albuterol.<br />

Hanania et al. Chest. 2003;124:834-843.

∆ FEV 1 (mL)<br />

200<br />

150<br />

100<br />

50<br />

0<br />

Superior Improvement in Predose FEV 1<br />

Demonstrates Contribution of Fluticasone Propionate<br />

PLA SAL 50 ADV 250/50<br />

(1%)<br />

(9%)<br />

(17%)<br />

-50<br />

Endpoint<br />

0 2 4 6 8 12 16 20 24 (last evaluable FEV 1 )<br />

Time (weeks)<br />

* P

* # * # *<br />

∆ Inspiratory Capacity (L)<br />

Salmeterol reduces dynamic<br />

hyperinflation during exercise in<br />

COPD<br />

0.4<br />

0.3<br />

0.2<br />

0.1<br />

0<br />

*<br />

SLM<br />

PLAC<br />

a<br />

b<br />

c<br />

Effect of salmeterol on mucosal<br />

damage<br />

Epithelial ciliated cells (% surface area)<br />

50<br />

40<br />

30<br />

20<br />

10<br />

0<br />

Haemophilus<br />

influenzae<br />

(a) Basal (b) Control (c) Salmeterol<br />

* p=0.002 vs. placebo<br />

Man et al. Thorax <strong>2004</strong><br />

Dowling et al, Eur Respir J 1998<br />

Synergistic interactions between<br />

salmeterol and fluticasone<br />

propionate<br />

Seretide onset of action: Significant<br />

improvement in lung function from day<br />

1<br />

Improvement in<br />

PEF (L/min)<br />

30<br />

Seretide 50/500mcg bd<br />

Salmeterol 50mcg bd<br />

Fluticasone propionate 500mcg bd<br />

20<br />

10<br />

*<br />

0<br />

Day 1 Days 1-14<br />

* p

What do improvements in health<br />

status actually mean for a patient?<br />

A 4 unit improvement in SGRQ<br />

score means that the patient<br />

No longer walks more slowly<br />

than others of their age<br />

and<br />

Is no longer breathless on<br />

bending over<br />

and<br />

Is no longer breathless when<br />

washing and dressing<br />

A 2.7 unit improvement in<br />

SGRQ score means that the<br />

patient<br />

No longer takes a long time<br />

to wash or dress<br />

and<br />

Can now climb a flight of<br />

stairs without stopping<br />

Jones Data on file<br />

Conclusion:<br />

COPD management can be<br />

improved today<br />

• Combination therapy of fluticasone<br />

propionate and salmeterol is an effective<br />

treatment for COPD<br />

– Functional impairement<br />

– Breathlessness<br />

– Health status<br />

• Patient condition can be rapidly improved:<br />

– In a few days for functional impairement and<br />

dyspnea<br />

– In a few weeks for health status<br />

Conclusions: COPD<br />

• Bronchodilators increase time to<br />

exacerbations<br />

• Inhaled corticosteroids reduce<br />

exacerbation rate<br />

• Exacerbation have effects on Hs QOL<br />

• And recovery of pulmonary function