Return of the Leopard. - Panthera

Return of the Leopard. - Panthera

Return of the Leopard. - Panthera

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

leopard<br />

RETURN OF THE<br />

Are <strong>the</strong>y protected or aren’t<br />

<strong>the</strong>y? Elusive and highly mobile,<br />

<strong>the</strong> leopards <strong>of</strong> Phinda in<br />

nor<strong>the</strong>rn KwaZulu-Natal, South<br />

Africa, pay scant attention to<br />

reserve boundaries and are<br />

consequently at a high risk <strong>of</strong><br />

being killed, legally or illegally.<br />

After three years <strong>of</strong> research<br />

into <strong>the</strong>ir predicament, <strong>the</strong><br />

Mun-Ya-Wana <strong>Leopard</strong> Project<br />

was ready to take action and,<br />

toge<strong>the</strong>r with <strong>the</strong> local conservation<br />

authority, devised a new<br />

regulatory system that could<br />

safeguard <strong>the</strong> big cats. Ano<strong>the</strong>r<br />

two years on and project member<br />

Guy Balme could already<br />

note <strong>the</strong> results.<br />

<br />

TEXT BY GUY BALME<br />

greg du toit<br />

34 AFRICA GEOGRAPHIC • february 2010<br />

www.africageographic.com<br />

35

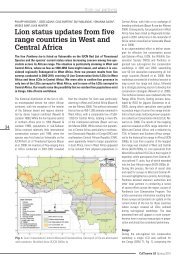

N<br />

U<br />

SWAZILAND<br />

Mkhuze Game<br />

Reserve<br />

KwaZulu-Natal<br />

Phinda Private Huddled in <strong>the</strong><br />

Game Reserve<br />

front seat <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

open Land Rover,<br />

I could not get<br />

I N D I A N<br />

OCEAN<br />

warm. Cold air<br />

lanced through<br />

• Richards Bay<br />

my jacket and <strong>the</strong> layers I had<br />

piled on to survive a winter<br />

night <strong>of</strong> tracking leopards. My<br />

motivation was fading fast. The young female I had<br />

been following since <strong>the</strong> previous afternoon had<br />

melted into a dense thicket and only <strong>the</strong> constant<br />

beep <strong>of</strong> her radio-collar reassured me that she had<br />

not disappeared entirely.<br />

One can stare at dead vegetation for only so long.<br />

Dawn was approaching and a cup <strong>of</strong> warming c<strong>of</strong>fee<br />

beckoned. As I reached for <strong>the</strong> ignition, an unexpected<br />

sound stopped my hand. S<strong>of</strong>t but unmistakable<br />

chirps – between a growl and a mew – were<br />

coming from <strong>the</strong> thicket. Carefully I repositioned<br />

<strong>the</strong> vehicle and <strong>the</strong>re, clambering among <strong>the</strong> branches,<br />

was <strong>the</strong> smallest leopard cub I had ever seen. Its<br />

spots were barely discernible and it looked no more<br />

than three weeks old. It stumbled onto <strong>the</strong> ground<br />

and approached <strong>the</strong> Land Rover one shaky step at a<br />

k<br />

MOZAMBIQUE<br />

iSimangaliso<br />

Wetland Park<br />

time. The pint-sized bundle <strong>of</strong> fur presented no danger,<br />

but an anxious mo<strong>the</strong>r leopard would have been<br />

a different story. Thankfully, a sharp hiss from <strong>the</strong><br />

female sent <strong>the</strong> cub scrambling for cover. Slowly I<br />

backed away and turned for home, elated with <strong>the</strong><br />

discovery <strong>of</strong> a new generation <strong>of</strong> Zululand leopards.<br />

Such sightings were rare in <strong>the</strong> early days <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Mun-Ya-Wana <strong>Leopard</strong> Project (see ‘Trash or in trouble?’<br />

in Africa Geographic, February 2004). Located in<br />

Phinda Private Game Reserve, <strong>the</strong> project was started<br />

in 2002 by Luke Hunter, now <strong>the</strong> executive director<br />

<strong>of</strong> Pan<strong>the</strong>ra, an organisation dedicated to conserving<br />

<strong>the</strong> world’s wild cats. At <strong>the</strong> time, Zululand represented<br />

<strong>the</strong> proverbial Wild West for leopards, which<br />

were targeted by almost every community in <strong>the</strong><br />

region: cattle ranchers, trophy hunters and Zulu pastoralists,<br />

as well as poachers who killed <strong>the</strong>m for<br />

traditional uses, from ceremonial dress to folk medicines.<br />

But that was all we knew.<br />

Until <strong>the</strong>n, leopards had been well studied only in a<br />

few protected areas where <strong>the</strong>y were insulated from<br />

human contact, so we had no information on <strong>the</strong><br />

consequences <strong>of</strong> high levels <strong>of</strong> persecution. If we were<br />

going to tackle those consequences, we would be taking<br />

on everyone in Zululand who had always killed<br />

D. & s. balfour/www.darylbalfour.com<br />

leopards, essentially without restriction. To do this we<br />

would need <strong>the</strong> support <strong>of</strong> strong science, so we<br />

launched <strong>the</strong> most intensive effort to date to understand<br />

<strong>the</strong> ecology <strong>of</strong> leopards in a patchwork <strong>of</strong> protected<br />

and non-protected areas. By using radio-collars<br />

and remotely triggered camera-traps and interviewing<br />

various communities, we gradually built up a picture<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> extent <strong>of</strong> leopard killing in <strong>the</strong> region – and<br />

whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> population could withstand it.<br />

Although leopards are protected in Phinda and<br />

several o<strong>the</strong>r private and state-run reserves in<br />

KwaZulu-Natal, problems arise when <strong>the</strong>y range into<br />

surrounding livestock farms, game ranches and tribal<br />

authority land. The electrified fencing around most<br />

protected areas does little to slow down <strong>the</strong> big cats:<br />

<strong>the</strong>y simply glide under <strong>the</strong> fences or go over <strong>the</strong>m. I<br />

once watched a young male leopard jump from a<br />

standing position onto a 2.5-metre-high fence pole,<br />

balance precariously for a few seconds, and <strong>the</strong>n leap<br />

nimbly down to <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r side. Thus, very few leopards<br />

in Zululand are permanently protected, and<br />

almost all are exposed to human persecution at some<br />

time in <strong>the</strong>ir lives.<br />

Legally, leopards can only be killed by private individuals<br />

who have ei<strong>the</strong>r a destruction permit or a<br />

CITES tag issued by <strong>the</strong> local conservation authority,<br />

Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife (EKZNW). Destruction permits<br />

are granted to remove confirmed ‘problem’<br />

leopards. In principle, a landowner has to prove that<br />

a leopard represents a threat to his safety or livelihood<br />

and that no o<strong>the</strong>r, less dire solution exists.<br />

When we first began our study, destruction permits<br />

were routinely awarded based on little evidence and,<br />

even more worryingly, recipients <strong>of</strong>ten pr<strong>of</strong>ited from<br />

<strong>the</strong>m. It is against <strong>the</strong> law to export a leopard skin<br />

obtained from a destruction permit, but local hunters<br />

will pay up to R20 000 for <strong>the</strong> opportunity to bag<br />

a cat. Farmers would <strong>the</strong>refore apply for a permit<br />

and sell <strong>the</strong> right to shoot <strong>the</strong> cat to a fellow South<br />

African. A permit would also be issued if a leopard<br />

was preying on wild ungulates. Even when killing<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir natural prey, leopards are treated as competitors<br />

by game ranchers – <strong>the</strong>y both harvest <strong>the</strong> same<br />

resource.<br />

CITES tags are allocated for <strong>the</strong> legal hunting <strong>of</strong><br />

leopards for sport. Of <strong>the</strong> 150 leopard skins South<br />

Africa is authorised to export every year, between<br />

five and 10 are allocated to KwaZulu-Natal. This<br />

hardly seems excessive for such an adaptable and<br />

widespread species, especially compared to <strong>the</strong> 50 for<br />

Limpopo Province or <strong>the</strong> 20 for North West.<br />

However, when we began our work, hunting effort<br />

was unevenly distributed in KwaZulu-Natal: almost<br />

80 per cent <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> CITES tags awarded between 2000<br />

and 2005 went to <strong>the</strong> properties surrounding Phinda<br />

and <strong>the</strong> adjacent Mkhuze Game Reserve.<br />

<br />

ZULULAND REPRESENTED THE PROVERBIAL WILD WEST FOR<br />

LEOPARDS, WHICH WERE TARGETED BY ALMOST EVERY<br />

COMMUNITY IN THE REGION<br />

LEFT A threemonth-old<br />

leopard<br />

cub peers at a vehicle<br />

no more than<br />

30 metres away.<br />

Sightings such as<br />

this were unheard <strong>of</strong><br />

in Zululand before<br />

leopard management<br />

policies were<br />

changed in 2005.<br />

BELOW A female<br />

leopard and her cub<br />

survey <strong>the</strong> landscape<br />

from a l<strong>of</strong>ty perch.<br />

The ability to climb<br />

trees <strong>of</strong>fers young<br />

leopards some protection<br />

from lions<br />

and hyaenas, but is<br />

no safeguard against<br />

adult male leopards.<br />

grant atkinson<br />

36 AFRICA GEOGRAPHIC • february 2010 www.africageographic.com 37

A leopard hauls a<br />

grey duiker up an<br />

acacia tree. <strong>Leopard</strong>s<br />

at Phinda rarely hoist<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir kills, probably<br />

because <strong>the</strong>ir main<br />

competitors – lions<br />

and spotted hyaenas<br />

– are relatively scarce.<br />

greg du toit<br />

Moreover, leopards were hunted on three game<br />

farms adjacent to Phinda for two successive years<br />

and ano<strong>the</strong>r for four years running. Hunting <strong>the</strong> big<br />

cats on <strong>the</strong> same farm in consecutive years creates<br />

pockets <strong>of</strong> habitat that are permanently empty <strong>of</strong><br />

resident leopards. These vacancies attract o<strong>the</strong>rs <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> species, particularly dispersing sub-adults,<br />

because <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> lack <strong>of</strong> competition for food and<br />

space. A network <strong>of</strong> vacuums arose around Phinda<br />

and Mkhuze as more and more cats were drawn from<br />

surrounding areas, and were in turn exposed to<br />

hunting. The legal killing <strong>of</strong> leopards was compounded<br />

by illegal persecution, which is almost<br />

impossible to police. <strong>Leopard</strong>s were opportunistically<br />

shot, gin-trapped, snared and, worst <strong>of</strong> all, poisoned.<br />

Three years into <strong>the</strong> research, our results<br />

painted a bleak picture. Thirteen <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

26 leopards radio-collared in Phinda had<br />

died from a combination <strong>of</strong> natural and<br />

human-related causes. In addition, we<br />

knew <strong>of</strong> 10 uncollared leopards that had<br />

been killed on properties adjoining <strong>the</strong> reserve. The<br />

average mortality rate <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> population was higher<br />

than 40 per cent, more than double that for leopards<br />

in similar habitat in <strong>the</strong> Kruger National Park, where<br />

all deaths were from natural causes. Males were <strong>the</strong><br />

worst affected: nearly 55 per cent <strong>of</strong> males that we<br />

monitored died each year. Not only preferred by trophy<br />

hunters because <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir size, male leopards use<br />

large home ranges, covering greater daily distances<br />

than females. This increases <strong>the</strong>ir chances <strong>of</strong> moving<br />

<strong>of</strong>f <strong>the</strong> reserve into areas where <strong>the</strong>y are vulnerable<br />

to hunters.<br />

REMOVING TOO MANY MALES … CAN LEAD TO ELEVATED<br />

LEVELS OF INFANTICIDE, IN WHICH A NEW MALE ENTERING THE<br />

POPULATION KILLS CUBS SIRED BY THE PREVIOUS MALE<br />

Although trophy hunting is not always automatically<br />

damaging to populations, removing too many<br />

males can induce a cascade <strong>of</strong> harmful outcomes in<br />

carnivores. In particular, it can lead to elevated<br />

levels <strong>of</strong> infanticide, in which a new male entering<br />

<strong>the</strong> population kills cubs sired by <strong>the</strong> previous<br />

male. This is what happened with <strong>the</strong> very first litter<br />

I observed in Phinda: <strong>the</strong> fa<strong>the</strong>r was shot outside<br />

<strong>the</strong> reserve and replaced by a new male that killed<br />

his predecessor’s cubs. Infanticide occurs naturally<br />

in leopard populations, but an artificially inflated<br />

turnover <strong>of</strong> males creates a situation in which<br />

females fail to raise youngsters because <strong>of</strong> constant<br />

incursions by immigrant males.<br />

Compounding this, females in Phinda gave birth<br />

at a later age and had longer intervals between litters<br />

than was known from stable populations. Even conception<br />

rates appeared to be affected. We knew from<br />

long-term research in <strong>the</strong> Serengeti that lionesses<br />

display a period <strong>of</strong> reduced fertility immediately after<br />

a new coalition <strong>of</strong> males has taken over <strong>the</strong> pride;<br />

females postpone conception until <strong>the</strong> threat <strong>of</strong><br />

fur<strong>the</strong>r takeovers has diminished. Female leopards in<br />

Phinda seemed to adopt a similar strategy, and less<br />

than a fifth <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> mating bouts we observed were<br />

successful. In <strong>the</strong> project’s first three years, only<br />

three cubs survived in <strong>the</strong> Phinda population while<br />

at least 23 leopards died.<br />

Spurred by <strong>the</strong>se figures, in 2005 we began<br />

working with EKZNW to turn things around. On<br />

our recommendation, <strong>the</strong> process governing <strong>the</strong><br />

use <strong>of</strong> destruction permits was overhauled. Only<br />

<strong>the</strong> landowner or an EKZNW <strong>of</strong>ficial can destroy<br />

an <strong>of</strong>fending leopard and <strong>the</strong> permits can no longer<br />

be sold for pr<strong>of</strong>it-making hunts. They are also<br />

no longer awarded for predation on wild herbivores,<br />

which is now treated as an inherent risk <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> game-farming industry. Finally, EKZNW<br />

decreed that relocation would be abandoned as a<br />

management tool to address problems with leopards.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> past, leopards suspected <strong>of</strong> killing<br />

livestock were <strong>of</strong>ten captured and moved to a<br />

reserve or game ranch committed to ecotourism.<br />

This may resolve <strong>the</strong> conflict on <strong>the</strong> affected<br />

farm, but <strong>of</strong>ten creates trouble elsewhere, as <strong>the</strong><br />

cats seldom remain on <strong>the</strong> new property and<br />

readily cross to a neighbouring farm and resume<br />

killing livestock.<br />

<br />

christian Sperka (2)<br />

ABOVE Female F9<br />

stops to scent-mark<br />

before continuing<br />

her territorial<br />

patrol. These<br />

patrols <strong>of</strong>ten take<br />

leopards beyond<br />

<strong>the</strong> borders <strong>of</strong><br />

Phinda into areas<br />

where <strong>the</strong>y are<br />

perceived as pests<br />

or targets for<br />

commercial<br />

trophy hunts.<br />

TOP Field assistant<br />

Tristan Dickerson<br />

moves cautiously<br />

up to a sedated<br />

female leopard.<br />

The Mun-Ya-Wana<br />

<strong>Leopard</strong> Project<br />

has radio-collared<br />

more than 65 leopards,<br />

resulting in<br />

<strong>the</strong> most intensive<br />

dataset ever<br />

collected on <strong>the</strong><br />

species.<br />

38 AFRICA GEOGRAPHIC • february 2010 www.africageographic.com 39

We also needed to encourage more sustainable<br />

sport hunting <strong>of</strong> leopards. Once EKZNW had scrutinised<br />

our data, it completely revised <strong>the</strong> system<br />

that allocated CITES tags. The most significant<br />

change was diluting <strong>the</strong> intense concentration <strong>of</strong><br />

hunting around Phinda. We created five <strong>Leopard</strong><br />

Hunting Zones (LHZs), which are allocated across <strong>the</strong><br />

species’ entire range in <strong>the</strong> province. The new system<br />

limits a single CITES tag to each LHZ, allowing<br />

only one leopard to be hunted <strong>the</strong>re. A tag assigned<br />

to an LHZ cannot be used elsewhere, regardless <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> demand for hunts in o<strong>the</strong>r zones. The upshot is<br />

that no more than five leopards are hunted each<br />

year in KwaZulu-Natal, and hunting pressure is evenly<br />

distributed. Moreover, each LHZ adjoins a suitably<br />

large protected area that acts as a source population<br />

to replace hunted individuals. The protected area<br />

effectively serves as a biological savings account that<br />

protects <strong>the</strong> core population from <strong>the</strong> effects <strong>of</strong><br />

hunting while also providing dispersers to neighbouring<br />

areas where hunting is permitted.<br />

This was <strong>the</strong> first time that an African statutory<br />

authority had taken <strong>the</strong> results <strong>of</strong><br />

scientific research and redesigned its protocols<br />

for hunting and <strong>the</strong> control <strong>of</strong><br />

problem leopards. Never<strong>the</strong>less, it was<br />

only <strong>the</strong> first half <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> process. Our credibility<br />

was on <strong>the</strong> line unless <strong>the</strong> radical changes we<br />

had fostered proved to be good for leopards. By <strong>the</strong><br />

end <strong>of</strong> 2007, we had <strong>the</strong> first signs that <strong>the</strong> conservation<br />

interventions we introduced were working. In<br />

<strong>the</strong> first two years following <strong>the</strong> changes, we recorded<br />

only eight leopard deaths (seven collared and one<br />

uncollared) compared to <strong>the</strong> 23 deaths prior to 2005.<br />

Correspondingly, <strong>the</strong> annual mortality rate <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

population plunged from 40 to 13 per cent – close to<br />

that for protected leopard populations elsewhere in<br />

South Africa.<br />

<strong>Leopard</strong>s were not only living longer, <strong>the</strong>y were<br />

also reproducing more effectively. Females gave<br />

birth at a younger age, spent a greater proportion <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong>ir time with dependent cubs, and produced<br />

more litters. Most importantly, cub survival<br />

increased dramatically; in fact, all 14 <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> cubs<br />

that we knew were born in Phinda after 2005 survived<br />

to independence. We think this was because<br />

<strong>the</strong> threat <strong>of</strong> infanticide dropped as <strong>the</strong> turnover in<br />

territorial males declined. From an average tenure<br />

<strong>of</strong> only 32 months prior to 2005, males held onto<br />

territories for longer than 45 months – long enough<br />

for females to raise litters to independence without<br />

<strong>the</strong> disruption caused by new males continually<br />

moving in.<br />

Perhaps <strong>the</strong> most conclusive pro<strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> positive<br />

changes came from <strong>the</strong> camera-trap surveys we<br />

conducted every second year in Phinda. The most<br />

efficient way to estimate leopard numbers is with<br />

neil whyte<br />

remotely triggered cameras that take photographs<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> cats as <strong>the</strong>y go about <strong>the</strong>ir daily lives. Since<br />

leopards have unique coat patterns, individuals can<br />

be identified from photos and this, combined with<br />

powerful ‘capture–recapture’ statistics, generates<br />

highly accurate estimates <strong>of</strong> abundance. In 2005,<br />

we calculated that leopard density in <strong>the</strong> reserve<br />

was 7.2 leopards per 100 square kilometres – a quite<br />

respectable number, but only 65 per cent <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

estimate from neighbouring Mkhuze (11.1 leopards<br />

per 100 square kilometres). In 2007, <strong>the</strong> popu -<br />

lation in Phinda had increased to 9.4 leopards per<br />

100 square kilometres, and by 2009 it was on a par<br />

with that in Mkhuze: 11.2 leopards per 100 square<br />

kilometres. Throughout <strong>the</strong> study we had monitored<br />

natural variables that affect leopard numbers,<br />

such as prey availability and competition with<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r predators, and <strong>the</strong>y had remained static.<br />

Hence, <strong>the</strong> only explanation was that our intervention<br />

programme was driving <strong>the</strong> recovery <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Phinda leopard population.<br />

Our final pro<strong>of</strong> was in <strong>the</strong> number <strong>of</strong> leopards<br />

killed by people, both legally and illegally: a drop<br />

from 15 to four. EKZNW’s new strategy for managing<br />

problem leopards had reduced <strong>the</strong> number <strong>of</strong><br />

cats removed, and <strong>the</strong> overhauled trophy hunting<br />

protocols successfully dispersed <strong>the</strong> hunting pressure.<br />

We believe <strong>the</strong> drop in illegal kills – from eight<br />

to two – reflects greater tolerance among landowners<br />

for leopards (as opposed to illegal killing<br />

becoming even more covert than previously). Our<br />

strategy for problem leopards hinged on helping<br />

farmers by providing training and support in alternative<br />

means <strong>of</strong> protecting <strong>the</strong>ir stock from predators,<br />

and by helping to identify where <strong>the</strong>re was a<br />

genuine problem individual; losses declined in all<br />

cases where our recommendations were adopted. In<br />

addition, <strong>the</strong> more democratic distribution <strong>of</strong> CITES<br />

WITH INTENSELY LIMITED RESOURCES, WE CAN’T AFFORD<br />

TO PERSIST WITH FEEL-GOOD PROJECTS UNLESS WE CAN<br />

SHOW SUCCESS – OR UNDERSTAND WHY THEY FAIL<br />

tags across <strong>the</strong> region gave a larger proportion <strong>of</strong><br />

landowners <strong>the</strong> opportunity to host a hunt, and<br />

hence <strong>the</strong> chance to benefit financially from having<br />

leopards on <strong>the</strong>ir land. When we interviewed<br />

farmers on properties surrounding Phinda towards<br />

<strong>the</strong> end <strong>of</strong> 2007, most told us <strong>the</strong>y preferred <strong>the</strong><br />

new management system to <strong>the</strong> old.<br />

If <strong>the</strong> changes become permanent, <strong>the</strong> future <strong>of</strong><br />

leopards in Phinda and Mkhuze is now much brighter.<br />

More than that, our study is one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> few examples<br />

demonstrating that conservation <strong>of</strong> big cats<br />

does work. We set out to achieve what many conservationists<br />

strive for: to address a threat, reduce <strong>the</strong> decline<br />

<strong>of</strong> a population or save a species. But we also<br />

scrutinise our results. With intensely limited resources,<br />

we can’t afford to persist with feel-good projects<br />

unless we can show success – or understand why<br />

<strong>the</strong>y fail. Our project has probably ensured <strong>the</strong> future<br />

<strong>of</strong> leopards in KwaZulu-Natal. Just as importantly, by<br />

showing that conservation can succeed, I hope we<br />

have inspired fellow conservationists to prove that<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir efforts are working. If we can do that, I believe<br />

that <strong>the</strong> future <strong>of</strong> leopards and many o<strong>the</strong>r similarly<br />

imperilled species will be far more secure.<br />

For fur<strong>the</strong>r information about <strong>the</strong> Mun-Ya-Wana<br />

<strong>Leopard</strong> Project and o<strong>the</strong>r initiatives <strong>of</strong> Pan<strong>the</strong>ra, go to<br />

www.pan<strong>the</strong>ra.org. Technical papers related to this article<br />

are available at http://pan<strong>the</strong>ra.org/scientific_<br />

publications.html<br />

The author would like to thank &Beyond and EKZNW,<br />

whose assistance in developing <strong>the</strong> new leopard management<br />

strategy was essential, and <strong>the</strong> many pr<strong>of</strong>essional<br />

hunters, game ranch managers, farmers and landowners<br />

who agreed to adopt it in <strong>the</strong> field.<br />

<br />

greg du toit<br />

Above The unique<br />

pattern <strong>of</strong> spots<br />

above where <strong>the</strong><br />

whiskers grow<br />

from <strong>the</strong> leopard’s<br />

face is used by<br />

researchers to distinguish<br />

individuals.<br />

OPPOSITE A picture<br />

<strong>of</strong> stealth and<br />

grace. <strong>Leopard</strong>s<br />

in KwaZulu-Natal<br />

have been <strong>of</strong>fered a<br />

new lifeline thanks<br />

to conservation<br />

interventions<br />

im plemented by<br />

<strong>the</strong> Mun-Ya-Wana<br />

<strong>Leopard</strong> Project and<br />

Ezemvelo KwaZulu-<br />

Natal Wildlife.<br />

40 AFRICA GEOGRAPHIC • february 2010 www.africageographic.com 41