Ecology and Management of the Bobwhite Quail in Alabama

Ecology and Management of the Bobwhite Quail in Alabama

Ecology and Management of the Bobwhite Quail in Alabama

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

The Department <strong>of</strong> Conservation <strong>and</strong> Natural Resources does not discrim<strong>in</strong>ate on <strong>the</strong> basis <strong>of</strong> race,<br />

c o l o r, religion, age, gender, national orig<strong>in</strong> or disability <strong>in</strong> its hir<strong>in</strong>g or employment practices nor <strong>in</strong><br />

admission to, access to, or operations <strong>of</strong> its programs, services or activities.

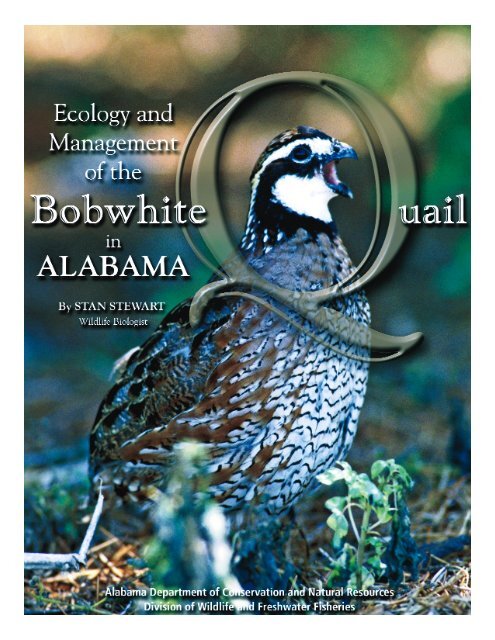

<strong>Ecology</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Management</strong><br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Q<br />

i n<br />

B o bwhite<br />

A L A B A M A<br />

By STAN STEWA RT<br />

Wildlife Biologist<br />

u a i l<br />

<strong>Alabama</strong> Department <strong>of</strong> Conservation <strong>and</strong> Natural Resourc e s<br />

Division <strong>of</strong> Wildlife <strong>and</strong> Freshwater Fisheries<br />

M. Barnett Lawley M.N., “Corky” Pugh<br />

C o m m i s s i o n e r<br />

D i re c t o r<br />

F red R. Hard e r s<br />

Assistant Dire c t o r<br />

G a ry H. Mood y<br />

Chief, Wildlife Section<br />

J a n u a ry 2005<br />

S u p p o rt for development <strong>of</strong> this publication was provided by <strong>the</strong> Wildlife Restoration Program <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Alabama</strong> Division <strong>of</strong> Wi l d l i f e<br />

<strong>and</strong> Freshwater Fisheries with funds provided by your purchase <strong>of</strong> hunt<strong>in</strong>g licenses <strong>and</strong> equipment.

Fo r ewo r d<br />

Wildlife conservationist Aldo Leopold said “a thicket without<br />

<strong>the</strong> potential roar <strong>of</strong> a quail covey is only a thorny place.” 2 6 H e<br />

viewed a l<strong>and</strong> without quail as somehow <strong>in</strong>complete <strong>and</strong> miss<strong>in</strong>g<br />

a valuable element <strong>of</strong> life. Only a quail hunter could make such a<br />

lament. Many <strong>of</strong> us long to aga<strong>in</strong> experience <strong>the</strong> rise <strong>of</strong> a favorite<br />

covey <strong>in</strong> front <strong>of</strong> a white statue <strong>of</strong> s<strong>in</strong>ew <strong>and</strong> steel. But, <strong>the</strong> old<br />

haunts have changed, replaced by <strong>the</strong> disputable marks <strong>of</strong><br />

“ p ro g ress.” In days past quail just happened. We didn’t give much<br />

thought to why <strong>the</strong>y were <strong>the</strong>re. We just expected <strong>the</strong>m to be<br />

t h e re, like <strong>the</strong> sun com<strong>in</strong>g up. Those days are gone.<br />

Associated with quiet countrysides, patch farms, idle fields<br />

<strong>and</strong> open woodl<strong>and</strong>s, <strong>the</strong> bobwhite earned <strong>the</strong> reputation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

g e n t l e m a n ’s game bird. Tod a y ’s sou<strong>the</strong>rn l<strong>and</strong>scape is vastly diff e r-<br />

ent from <strong>the</strong> one that fostered our quail hunt<strong>in</strong>g tradition.<br />

P e rhaps only <strong>the</strong> dedicated old-time quail hunters know how drastically<br />

quail hunt<strong>in</strong>g has changed. Because <strong>the</strong> younger generation<br />

does not really underst<strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> stark changes <strong>in</strong> quail abundance,<br />

it does not have <strong>the</strong> passionate sense <strong>of</strong> loss that fosters a desire for<br />

restoration. It is a pa<strong>in</strong>ful irony that this bird, once so benefited by<br />

m a n ’s actions, is now so displaced by man’s actions.<br />

The bobwhite’s future is bright <strong>in</strong> one sense. We no longer<br />

have to depend on quail just happen<strong>in</strong>g. We can make <strong>the</strong>m happen.<br />

In recent years managers <strong>and</strong> re s e a rchers have re - v i s i t e d<br />

sound bobwhite biology <strong>and</strong> have made new discoveries about<br />

bobwhite behavior, ecology <strong>and</strong> management. Individuals who are<br />

apply<strong>in</strong>g this knowledge are currently experienc<strong>in</strong>g unpre c e d e n t-<br />

ed bobwhite management successes <strong>and</strong> population highs. The<br />

message is clear. <strong>Quail</strong> do not have to be just a part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> past.<br />

They respond to management. Supply <strong>the</strong> birds a favorable environment<br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>y usually <strong>in</strong>crease rapidly.<br />

It is not foreseeable that bobwhites will aga<strong>in</strong> be <strong>in</strong>advert e n t-<br />

ly abundant. For populations to <strong>in</strong>crease, all who are concern e d<br />

about <strong>the</strong> bobwhite, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g wildlife agencies, wildlife managers,<br />

l<strong>and</strong>owners, advocacy organizations <strong>and</strong> hunters must learn<br />

to th<strong>in</strong>k diff e rently about <strong>the</strong> occurrence <strong>of</strong> bobwhites <strong>in</strong> cont<br />

e m p o r a ry l<strong>and</strong>scapes. We must become more precisely knowledgeable<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir re q u i rements. We must look for <strong>in</strong>novative ways<br />

to <strong>in</strong>clude quail habitat <strong>in</strong> l<strong>and</strong> uses. We must be proactive <strong>and</strong><br />

cooperative, concentrat<strong>in</strong>g on proven methods, both old <strong>and</strong> new.<br />

At <strong>the</strong> Fourth National <strong>Quail</strong> Symposium, long time bobwhite<br />

re s e a rcher John L. Roseberry, speak<strong>in</strong>g from <strong>the</strong> heart <strong>of</strong><br />

quail plantation country where <strong>the</strong> bobwhite is still supreme, said<br />

“ We have sufficient knowledge <strong>and</strong> skill to produce locally abundant<br />

quail populations. To be a viable game species, however,<br />

[quail] must be reasonably abundant over relatively large port i o n s<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scape.” 3 5 Identify<strong>in</strong>g opportunities to <strong>in</strong>corporate re a-<br />

sonable amounts <strong>of</strong> quail habitat across l<strong>and</strong>scapes <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>to major<br />

l<strong>and</strong> uses is tod a y ’s challenge.<br />

The Nort h e rn <strong>Bobwhite</strong> Conservation Initiative (NBCI),<br />

p re p a red by <strong>the</strong> Sou<strong>the</strong>ast <strong>Quail</strong> Study Group at <strong>the</strong> request <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

D i rectors <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Sou<strong>the</strong>astern Association <strong>of</strong> Fish <strong>and</strong> Wi l d l i f e<br />

Agencies, was released <strong>in</strong> 2002. NBCI is essentially a rangewide<br />

bobwhite re c o v e ry plan that quantifies <strong>the</strong> habitat additions needed<br />

<strong>in</strong> agricultural, pasture <strong>and</strong> forest l<strong>and</strong>scapes to re s t o re bobwhite<br />

populations to 1980 levels, when <strong>the</strong>y were still re a s o n a b l y<br />

abundant over much <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scape. In <strong>Alabama</strong> at that time,<br />

bobwhite populations were decl<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g at a rate <strong>of</strong> only 2 perc e n t<br />

a n n u a l l y. From <strong>the</strong> mid 1980s to mid 1990s <strong>the</strong> quail loss accelerated<br />

to a 9 percent per year average annual rate <strong>of</strong> decl<strong>in</strong>e. The<br />

l<strong>and</strong>scape conditions that prevailed <strong>in</strong> 1980 were clearly more<br />

suitable to bobwhites than current l<strong>and</strong>scapes.<br />

As a direct result <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Nort h e rn <strong>Bobwhite</strong> Conserv a t i o n<br />

Initiative, <strong>the</strong> United States Department <strong>of</strong> Agriculture <strong>in</strong> 2004<br />

announced, by no less a spokesman than <strong>the</strong> President himself, a<br />

f a r- reach<strong>in</strong>g Nort h e rn <strong>Bobwhite</strong> <strong>Quail</strong> Habitat Initiative with<strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> Conservation Reserve Program. The implications for quail<br />

restoration are enormous because CRP is such a popular <strong>and</strong> wellfunded<br />

program <strong>of</strong> national scope. The <strong>in</strong>itiative is designed so<br />

that any l<strong>and</strong>owner with active cropl<strong>and</strong> who wants more quail<br />

back on <strong>the</strong> farm now has <strong>the</strong> f<strong>in</strong>ancial re s o u rces available<br />

t h rough CRP to <strong>in</strong>stall productive quail habitat along <strong>the</strong> bord e r s<br />

<strong>of</strong> farm fields. Participants who meet basic CRP eligibility ru l e s<br />

<strong>and</strong> who apply for CRP conservation practice CP33, Habitat<br />

B u ffers for Upl<strong>and</strong> Birds, are automatically approved for enro l l-<br />

ment. Enrollment provides f<strong>in</strong>ancial assistance to <strong>in</strong>stall <strong>the</strong> practice<br />

<strong>and</strong> annual rental payments for at least ten years to ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> practice. It also <strong>in</strong>cludes a very attractive up-front bonus payment<br />

for elect<strong>in</strong>g to enroll farm l<strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> this practice with high<br />

c o n s e rvation value. The future for quail is <strong>in</strong>deed bright if conservation<br />

<strong>in</strong>itiatives such as this are implemented on <strong>the</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scape.<br />

Stan Stewart<br />

4 <strong>Ecology</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Management</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Bobwhite</strong> <strong>Quail</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Alabama</strong>

Ac k n ow l e d g m e n t s<br />

T<br />

This book is a product <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> author’s ideas, experience <strong>and</strong><br />

review <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> published works <strong>of</strong> o<strong>the</strong>rs. I am grateful to <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividuals<br />

who read <strong>the</strong> manuscript <strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong>f e red suggestions for<br />

i m p ro v e m e n t .<br />

Special acknowledgment is extended to Ted DeVos <strong>of</strong> Bach<br />

<strong>and</strong> DeVos Fore s t ry <strong>and</strong> Wildlife Services, for his technical re v i e w<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> manuscript, his correction <strong>of</strong> discrepancies, <strong>and</strong> his extensive<br />

work that provided an <strong>Alabama</strong> quail restoration success story<br />

for <strong>the</strong> conclusion <strong>of</strong> this book.<br />

I acknowledge <strong>the</strong> <strong>Alabama</strong> Division <strong>of</strong> Wildlife <strong>and</strong><br />

F reshwater Fisheries for its support <strong>and</strong> encouragement <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

development <strong>of</strong> this publication as a re s o u rce management guide<br />

for l<strong>and</strong>owners, quail managers, <strong>and</strong> quail enthusiasts. Reviewers<br />

who made valuable additions to <strong>the</strong> text <strong>in</strong>clude Gary Mood y,<br />

Chief <strong>of</strong> Wildlife, <strong>Alabama</strong> Wildlife <strong>and</strong> Freshwater Fisheries<br />

Division; Keith Guyse, Assistant Chief, Wildlife Section,<br />

<strong>Alabama</strong> Wildlife <strong>and</strong> Freshwater Fisheries Division; Bob<br />

McCollum, Nongame Coord i n a t o r, <strong>Alabama</strong> Wildlife <strong>and</strong><br />

F reshwater Fisheries Division; Andrew Nix, Fore s t e r, <strong>Alabama</strong><br />

Wildlife <strong>and</strong> Freshwater Fisheries Division; Jerry De B<strong>in</strong>, Chief,<br />

I n f o rmation <strong>and</strong> Education Section, <strong>Alabama</strong> Department <strong>of</strong><br />

C o n s e rvation <strong>and</strong> Natural Resources; Kim Nix, Manag<strong>in</strong>g Editor,<br />

I n f o rmation <strong>and</strong> Education Section, <strong>Alabama</strong> Department <strong>of</strong><br />

C o n s e rvation <strong>and</strong> Natural Resources; Gaylon Gw<strong>in</strong>, Senior Staff<br />

Wr i t e r, Information <strong>and</strong> Education Section, <strong>Alabama</strong><br />

D e p a rtment <strong>of</strong> Conservation <strong>and</strong> Natural Resources; <strong>and</strong> Billy<br />

Pope, Graphic Artist, Information <strong>and</strong> Education Section,<br />

<strong>Alabama</strong> Department <strong>of</strong> Conservation <strong>and</strong> Natural Resources. I<br />

extend my thanks to Richard Liles, Conservation Operations<br />

D i re c t o r, <strong>Alabama</strong> Department <strong>of</strong> Conservation <strong>and</strong> Natural<br />

R e s o u rces, for his cont<strong>in</strong>u<strong>in</strong>g support <strong>of</strong> quail restoration eff o rts <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>Alabama</strong>. Thanks to George Pudzis Graphic Design, LLC for perf<br />

o rm<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> design <strong>of</strong> this publication.<br />

I thank Dr. Lee Stribl<strong>in</strong>g, Associate Pro f e s s o r, Auburn<br />

University School <strong>of</strong> Fore s t ry <strong>and</strong> Wildlife Sciences; Steven<br />

Mitchell, Research Assistant, Auburn University School <strong>of</strong><br />

F o re s t ry <strong>and</strong> Wildlife Sciences; Dr. Barry Gr<strong>and</strong>, Leader, <strong>Alabama</strong><br />

Cooperative Fish <strong>and</strong> Wildlife Research Unit; <strong>and</strong> Travis Folk,<br />

Graduate Research Assistant, <strong>Alabama</strong> Cooperative Fish <strong>and</strong><br />

Wildlife Research Unit for on-<strong>the</strong>-ground re s e a rch <strong>in</strong>sights provided<br />

through <strong>the</strong>ir respective associations with Auburn<br />

U n i v e r s i t y ’s <strong>Alabama</strong> <strong>Quail</strong> <strong>Management</strong> Project <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Alabama</strong> Cooperative Fish <strong>and</strong> Wildlife Research Unit’s <strong>in</strong>vestigation<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Ecology</strong> <strong>of</strong> Nort h e rn <strong>Bobwhite</strong>s <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Longleaf P<strong>in</strong>e<br />

E c o s y s t e m .<br />

L a s t l y, I want to thank my uncle Paul Johnson for tak<strong>in</strong>g me<br />

<strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> quail fields from an early age, for giv<strong>in</strong>g me Dan, my first<br />

b i rd dog, <strong>and</strong> for accord<strong>in</strong>g me equal status as a hunter among men<br />

dedicated to all th<strong>in</strong>gs quail.<br />

Table <strong>of</strong> Contents<br />

F o re w o rd. ............................................................................... 4. .....<br />

A c k n o w l e d g m e n t s. ................................................................ 5. ....<br />

Chapter 1: Ta x o n o m y, Description <strong>and</strong> Distribution . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .6<br />

Chapter 2: History <strong>and</strong> Status. ............................................... 8. ...<br />

Chapter 3: Habits . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1 0<br />

Chapter 4: Habitat Require m e n t s. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1 6<br />

Chapter 5: Habitat <strong>Management</strong>. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2 0<br />

Chapter 6: Predation <strong>and</strong> Predator <strong>Management</strong> . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .3 6<br />

Chapter 7: Hunt<strong>in</strong>g . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .3 8<br />

S u m m a ry . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .4 1<br />

A p p e n d i x. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .4 2<br />

B i b l i o g r a p h y. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .4 3<br />

Stan Stewart<br />

Cover photo by Jim Ra<strong>the</strong>rt/Missouri Dept. <strong>of</strong> Conserva t i o n .<br />

<strong>Ecology</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Management</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Bobwhite</strong> <strong>Quail</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Alabama</strong> 5

Chapter 1<br />

TA XO N O M Y, DESCRIPTION<br />

AND DISTRIBUTION<br />

Col<strong>in</strong>us virg i n i a n u s, <strong>the</strong> nort h e rn bobwhite, belongs to <strong>the</strong><br />

o rder G a l l i f o rm e s ,which is from <strong>the</strong> Lat<strong>in</strong> gall<strong>in</strong>aceus mean<strong>in</strong>g “<strong>of</strong><br />

p o u l t ry.” They are <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> same order <strong>of</strong> birds as domestic fowl,<br />

which also <strong>in</strong>cludes turkeys, pheasants, grouse, partridges <strong>and</strong><br />

o<strong>the</strong>r quail. It is part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> family O d o n t o p h o r i d a e ,<strong>the</strong> New Wo r l d<br />

quails, which have a serrated lower m<strong>and</strong>ible. The next time you<br />

a re lucky enough to hold a bobwhite <strong>in</strong> h<strong>and</strong>, you can observe this<br />

characteristic. The genus name Col<strong>in</strong>us derives from an Aztec<br />

w o rd mean<strong>in</strong>g “quail.” There are four species <strong>of</strong> Col<strong>in</strong>us ( b o b-<br />

whites) <strong>in</strong> North, Central, <strong>and</strong> South America. Only <strong>the</strong> nort h-<br />

e rn bobwhite, Col<strong>in</strong>us virg i n i a n u s ,occurs <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> United States.<br />

The bobwhite’s common name derives from <strong>the</strong> sound <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

m a l e ’s breed<strong>in</strong>g call, a two- or three-note whistle that sounds like<br />

“bob-white” or “ah-bob-white;” <strong>the</strong> first syllables are low monotones<br />

followed by <strong>the</strong> f<strong>in</strong>al resound<strong>in</strong>g, ris<strong>in</strong>g note.<br />

Male bobwhites have a white fea<strong>the</strong>red throat patch <strong>and</strong> eye<br />

stripe bord e red with black. In females, <strong>the</strong>se areas are a deep buff<br />

c o l o r. The crown <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> head, neck, upper breast, upper back <strong>and</strong><br />

w<strong>in</strong>g coverts are russet, many fea<strong>the</strong>rs barred on <strong>the</strong> edge with<br />

black or gray. The nape <strong>and</strong> upper breast are streaked with white.<br />

Male bobwhites have a white fea<strong>the</strong>red throat patch <strong>and</strong> eye stripe bord e red with black. In females, <strong>the</strong>se areas are a deep buff color.<br />

JIM RAT H E RT/MISSOURI DEPT. OF CONSERVAT I O N<br />

6 <strong>Ecology</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Management</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Bobwhite</strong> <strong>Quail</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Alabama</strong>

N o r t h e rn <strong>Bobwhite</strong> Range <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> U.S.<br />

The tail is gray. The abdomen is white or buffy white with black<br />

b a rr<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> tawny strip<strong>in</strong>g on <strong>the</strong> flanks. The beak is black <strong>and</strong><br />

legs are tannish gray. Adult bobwhites are about eight <strong>in</strong>ches <strong>in</strong><br />

length. Average weights vary from a little less than six ounces for<br />

b i rds from warm sou<strong>the</strong>rn climates to slightly more than seven<br />

ounces for birds from <strong>the</strong> cold nort h e rn portions <strong>of</strong> its range. 3 7<br />

<strong>Alabama</strong> bobwhites average about six ounces. 41<br />

The nort h e rn bobwhite has an extensive range, from sou<strong>the</strong><br />

a s t e rn New York to sou<strong>the</strong>rn Ontario, west to south central<br />

South Dakota, eastern Wyom<strong>in</strong>g, eastern Colorado, eastern New<br />

Mexico, <strong>and</strong> south through <strong>the</strong> Gulf States <strong>and</strong> most <strong>of</strong> Mexico<br />

<strong>and</strong> Central America. They were <strong>in</strong>troduced to <strong>the</strong> Pacific<br />

N o rthwest, <strong>and</strong> scattered populations still exist <strong>in</strong> valleys along<br />

tributaries <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Snake <strong>and</strong> Columbia rivers <strong>in</strong> Idaho, Ore g o n ,<br />

Wash<strong>in</strong>gton, Montana, <strong>and</strong> British Columbia. Also, <strong>the</strong> masked<br />

bobwhite (Col<strong>in</strong>us virg<strong>in</strong>ianus ridgwayi), an endangered subspecies,<br />

has been re i n t roduced to sou<strong>the</strong>rn Arizona. Introduced populations<br />

<strong>of</strong> bobwhites also occur <strong>in</strong> Cuba, Haiti, <strong>the</strong> Dom<strong>in</strong>ican<br />

Republic, <strong>and</strong> New Zeal<strong>and</strong>.<br />

A female bobwhite.<br />

JIM RAT H E RT/MISSOURI DEPT. OF CONSERVAT I O N<br />

<strong>Ecology</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Management</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Bobwhite</strong> <strong>Quail</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Alabama</strong> 7

Chapter 2<br />

H I S TO RY AND STAT U S<br />

T h e re is serious concern about <strong>the</strong> status <strong>of</strong> bobwhite quail<br />

populations <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> decl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> quail hunt<strong>in</strong>g opportunities acro s s<br />

<strong>the</strong> Sou<strong>the</strong>ast, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Alabama</strong>. <strong>Bobwhite</strong> numbers are decl<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g<br />

over much <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> bird ’s U.S. range. Traditional quail hunt<strong>in</strong>g<br />

is almost gone <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Sou<strong>the</strong>ast, where quail hunt<strong>in</strong>g has a storied<br />

h i s t o ry <strong>and</strong> bobwhites were a customary part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scape.<br />

What happened? And, what can we do?<br />

No re c o rds or accounts exist that conclusively tell us <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

status <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> bobwhite quail <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> South <strong>and</strong> East at <strong>the</strong> time <strong>of</strong><br />

E u ropean settlement. We know that potential quail habitat was<br />

available as a result <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> shift<strong>in</strong>g agriculture <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> widely<br />

applied burn<strong>in</strong>g practices <strong>of</strong> aborig<strong>in</strong>als that ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>ed open<br />

l<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> open forest. Eastern Indians cleared a great amount <strong>of</strong><br />

l<strong>and</strong>scape for farm<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>and</strong> even after ab<strong>and</strong>onment <strong>the</strong>se are a s<br />

rema<strong>in</strong>ed open from broadcast burn<strong>in</strong>g. Early Europeans described<br />

<strong>the</strong>se open l<strong>and</strong>s as “barrens,” <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>y were by all accounts pre v a-<br />

lent. There was little <strong>in</strong> a heavily wooded forest to attract Indians.<br />

W h e rever possible <strong>the</strong>y replaced <strong>the</strong>m with a mosaic <strong>of</strong> open<br />

l<strong>and</strong>s <strong>and</strong> open woodl<strong>and</strong>s. The forest that existed was <strong>of</strong>ten lightly<br />

stocked <strong>and</strong> free <strong>of</strong> underbru s h . 3 1 Even <strong>the</strong> name <strong>Alabama</strong> is a<br />

Choctaw Indian word mean<strong>in</strong>g “thicket cleare r s . ” 5 0<br />

On his travels through Georgia <strong>and</strong> <strong>Alabama</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> 1780s,<br />

botanist William Bartram described <strong>the</strong> central portions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se<br />

states as “diversified with hills <strong>and</strong> dales, savannas <strong>and</strong> vast cane<br />

meadows…sublime forests contrasted by expansive illum<strong>in</strong>ed<br />

g reen fields, native meadows <strong>and</strong> cane brakes…open airy groves <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> superb tereb<strong>in</strong>th<strong>in</strong>e p<strong>in</strong>es…pellucid brooks me<strong>and</strong>er<strong>in</strong>g<br />

t h rough an expansive green savanna…a delightful varied l<strong>and</strong>scape,<br />

consist<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> extensive grassy fields <strong>and</strong> detached groves <strong>of</strong><br />

high forest trees.” South <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Tallapoosa <strong>and</strong> <strong>Alabama</strong> rivers<br />

w e re “expansive, illum<strong>in</strong>ed grassy pla<strong>in</strong>s…<strong>in</strong>vested by high<br />

f o rests…which project <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> pla<strong>in</strong>s on each side, divid<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>m<br />

<strong>in</strong>to many vast fields…<strong>the</strong> surface <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> pla<strong>in</strong>s clad with tall grass,<br />

i n t e rmixed with a variety <strong>of</strong> herbage. In south <strong>Alabama</strong> he<br />

e n c o u n t e red “one vast flat grassy savanna, <strong>in</strong>tersected…with narrow<br />

forests <strong>and</strong> groves on <strong>the</strong> banks <strong>of</strong> creeks…with long leaved<br />

p<strong>in</strong>es, scatter<strong>in</strong>gly planted amongst <strong>the</strong> grass.” 4<br />

Indians fired <strong>the</strong> woods annually for hunt<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> brush cont<br />

rol to ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> open l<strong>and</strong>s <strong>and</strong> open woods. There are no re c o rd s<br />

<strong>of</strong> actual quail numbers occurr<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>se regimes. We do know<br />

that bobwhites were widely distributed, although little utilized by<br />

aborig<strong>in</strong>als. Stod d a rd re p o rted study<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> 1920s an unhunted<br />

bobwhite population liv<strong>in</strong>g under natural conditions on a 10,000-<br />

a c re tract <strong>of</strong> open virg<strong>in</strong> p<strong>in</strong>e forest <strong>in</strong> Florida, an area re p re s e n t a-<br />

tive <strong>of</strong> much <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> orig<strong>in</strong>al p<strong>in</strong>ey woods <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>rn coastal<br />

pla<strong>in</strong>. He determ<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>the</strong> quail population to be relatively abundant,<br />

about one bird per four to five acres <strong>in</strong> w<strong>in</strong>ter. 5 1<br />

R e c o rds <strong>in</strong>dicate that “virg<strong>in</strong>” forests across most <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

s o u t h e rn coastal pla<strong>in</strong> were not heavily timbered. They were not<br />

t ruly virg<strong>in</strong> s<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>the</strong>y already had a long history <strong>of</strong> human <strong>in</strong>fluence<br />

by <strong>the</strong> time <strong>of</strong> European discovery. Surveys conducted <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

1890s <strong>in</strong> Mobile County, <strong>Alabama</strong> showed that one acre <strong>of</strong><br />

untouched forest, very open <strong>and</strong> free <strong>of</strong> smaller trees <strong>and</strong> underg<br />

rowth, conta<strong>in</strong>ed 16 trees, most <strong>of</strong> which were 16 to 18 <strong>in</strong>ches <strong>in</strong><br />

diameter at breast height. Ano<strong>the</strong>r one-acre plot considere d<br />

exceptionally heavily timbered conta<strong>in</strong>ed 45 trees, <strong>the</strong> majority <strong>of</strong><br />

which were 16 to 18 <strong>in</strong>ches <strong>in</strong> diameter at breast height. 5 0 Tod a y,<br />

a comparable st<strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong> trees considered fully stocked for timber<br />

p roduction would have 50 to 65 trees per acre .<br />

As European settlement pro g ressed, forests were cleared <strong>and</strong><br />

old Indian agricultural fields were adopted for <strong>the</strong> major livelih<br />

o od <strong>of</strong> farm<strong>in</strong>g. The Europeans also practiced shift<strong>in</strong>g agricult<br />

u re. Sequences <strong>of</strong> slash-<strong>and</strong>-burn l<strong>and</strong> clear<strong>in</strong>g were followed by<br />

t e m p o r a ry cultivation, field ab<strong>and</strong>onment <strong>and</strong> new clear<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

In <strong>Alabama</strong>, <strong>the</strong> first settlers were it<strong>in</strong>erant herdsmen. Indian<br />

b u rn<strong>in</strong>g practices were thoroughly adopted by <strong>the</strong>m for hunt<strong>in</strong>g,<br />

graz<strong>in</strong>g range improvement <strong>and</strong> pest control. An “<strong>Alabama</strong><br />

boom” <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> 1820s brought many new settlers who cleared <strong>the</strong><br />

best l<strong>and</strong> for plant<strong>in</strong>g cotton. Cotton farm<strong>in</strong>g quickly wore out<br />

<strong>the</strong> l<strong>and</strong>, m<strong>and</strong>at<strong>in</strong>g a cont<strong>in</strong>ual process <strong>of</strong> shift<strong>in</strong>g agriculture .<br />

Follow<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> collapse <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> plantation system after <strong>the</strong> Civil<br />

Wa r, share cropp<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> “patch farm<strong>in</strong>g” became <strong>the</strong> norm .<br />

B u rn<strong>in</strong>g practices cont<strong>in</strong>ued <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> open p<strong>in</strong>ey woods. Are a s<br />

a round home sites were burned annually, but cattle ranges were<br />

not burned as <strong>of</strong>ten, creat<strong>in</strong>g a mosaic <strong>of</strong> new growth <strong>and</strong> slightly<br />

older “ro u g h . ” 3 1 This pattern <strong>of</strong> l<strong>and</strong> use cont<strong>in</strong>ued until <strong>the</strong> end<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> n<strong>in</strong>eteenth century. Most <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scape was good for<br />

quail, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>y flourished <strong>in</strong> this atmosphere. Sou<strong>the</strong>astern bob-<br />

Longleaf P<strong>in</strong>e<br />

Range Map<br />

<strong>Bobwhite</strong>s were relatively abundant <strong>in</strong> much <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> orig<strong>in</strong>al p<strong>in</strong>ey woods <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

sou<strong>the</strong>ast. Today only four percent <strong>of</strong> longleaf forests re m a i n .<br />

8 <strong>Ecology</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Management</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Bobwhite</strong> <strong>Quail</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Alabama</strong>

white populations peaked just prior to <strong>the</strong> turn <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> twentieth<br />

c e n t u ry <strong>and</strong> rema<strong>in</strong>ed at relatively high levels until about 1940. 37<br />

F rom 1930 to 1960 farm<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>Alabama</strong> dim<strong>in</strong>ished rapidly as<br />

society <strong>in</strong>dustrialized. In 1930 <strong>Alabama</strong> had more than 250,000<br />

f a rms with an average farm size <strong>of</strong> about 60 acres. By 1960 farm<br />

numbers had decl<strong>in</strong>ed to 120,000 <strong>and</strong> farm size doubled.<br />

C u rre n t l y, farms number less than 50,000 <strong>and</strong> average farm size is<br />

about 190 acre s . 54 The shift from widespread crude agriculture to<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r l<strong>and</strong> uses has had a major impact on bobwhite populations<br />

a c ross <strong>the</strong> state. Alabamians boasted <strong>of</strong> hav<strong>in</strong>g more bobwhites<br />

than any o<strong>the</strong>r state <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> 1920s, with a roughly estimated<br />

17,000,000 acres <strong>of</strong> suitable habitat. 1 A re p o rt on an <strong>in</strong>ventory <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> state’s wildlife re s o u rces <strong>in</strong> 1942 noted a decl<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g quail population<br />

due to loss <strong>of</strong> fallow fields, clear<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> hedgerows, <strong>in</strong>cre a s-<br />

es <strong>in</strong> field size, <strong>and</strong> re f o re s t a t i o n . 2<br />

The quail population changes on a 4,000-acre quail re s e a rc h<br />

a rea <strong>in</strong> Barbour County, <strong>Alabama</strong> exemplify <strong>the</strong> quail decl<strong>in</strong>es <strong>of</strong><br />

this period. <strong>Quail</strong> hunt<strong>in</strong>g re c o rds from <strong>the</strong> 1920s to 1940s<br />

showed that two hunters could expect to move 20 to 35 coveys <strong>in</strong><br />

a day’s hunt. Dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> 1940s tenant farm<strong>in</strong>g ended, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> l<strong>and</strong><br />

was converted over time to timber <strong>and</strong> cattle prod u c t i o n .<br />

R e s e a rch from 1954 to 1958 showed <strong>the</strong> area was <strong>the</strong>n 43 perc e n t<br />

p<strong>in</strong>e woods, 39 percent hard w o ods, 10 percent improved pasture ,<br />

<strong>and</strong> 8 percent cropl<strong>and</strong>. Census work dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> study period<br />

d e t e rm<strong>in</strong>ed that <strong>the</strong> w<strong>in</strong>ter quail population varied from one bird<br />

per 5.1 to 7.5 acres, <strong>and</strong> quail hunt<strong>in</strong>g was considered poor comp<br />

a red to earlier times. 24<br />

A l a b a m a ’s farms, presently with about 4 million acres <strong>of</strong> agricultural<br />

cro p l a n d s , 38<br />

have become large, mechanized operations<br />

with little idle l<strong>and</strong>. Much former agricultural l<strong>and</strong> has been conv<br />

e rted to cattle forages us<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>troduced pasture grasses, with<br />

about 5 million acres now <strong>in</strong> this l<strong>and</strong> use. 3 A great deal <strong>of</strong> l<strong>and</strong><br />

has naturally regenerated to dense forest or has been converted to<br />

timber production. Ve ry little <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> state’s current 23 million<br />

a c res <strong>of</strong> fore s t 21 is good quail habitat. Follow<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> advent <strong>of</strong> forest<br />

restoration eff o rts <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> South, fire was generally re m o v e d<br />

f rom <strong>the</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scape as major eff o rts were directed toward fire prevention<br />

beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> 1924. 50 Population growth <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>cre a s i n g<br />

urbanization have fur<strong>the</strong>r precluded use <strong>of</strong> fire .<br />

B reed<strong>in</strong>g bird survey data documents a 4 percent per year<br />

decl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> bobwhite abundance <strong>in</strong> <strong>Alabama</strong> s<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>the</strong> 1960s, <strong>and</strong><br />

an accelerated 9 percent per year decl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> mid 1980s to mid<br />

1990 s . 39 A l a b a m a ’s quail population <strong>in</strong> less than 20 percent <strong>of</strong><br />

what it was when surveys began <strong>in</strong> 1966. To put this <strong>in</strong> perspective,<br />

where <strong>the</strong>re were five coveys a few decades ago, <strong>the</strong>re is now<br />

only one covey. And, those isolated coveys cont<strong>in</strong>ue to disappear.<br />

No. Farms (Thous<strong>and</strong>s)<br />

3 0 0 –<br />

2 5 0 –<br />

2 0 0 –<br />

1 5 0 –<br />

1 0 0 –<br />

5 0 –<br />

0 –<br />

1 9 3 0 1 9 4 0 1 9 5 0 1 9 6 0 1 9 7 0 1 9 8 0 1 9 9 0 1 9 9 8 1 9 9 9 2 0 0 0 2 0 0 1<br />

Number <strong>of</strong> Farms<br />

<strong>Alabama</strong> Farms<br />

A c re s<br />

C o u n t<br />

6 0 –<br />

5 0 –<br />

4 0 –<br />

3 0 –<br />

2 0 –<br />

1 0 –<br />

0 –<br />

Average Number<br />

<strong>of</strong> Whistl<strong>in</strong>g Males<br />

Per Survey Route<br />

Annual quail harvests as high as 2.8 million birds <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> 1960s<br />

have decl<strong>in</strong>ed to recent harvest levels <strong>of</strong> only 160,000. 8 C u rre n t l y,<br />

quail harvests are less than 5 percent <strong>of</strong> those <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> 1960s.<br />

Although equivalent data is not available, anecdotal accounts<br />

suggest that bobwhite numbers <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> 1960s were only a fraction<br />

<strong>of</strong> populations <strong>in</strong> earlier times.<br />

A l<strong>and</strong>scape that once highly favored quail over large are a s<br />

has now become an environment <strong>of</strong>fer<strong>in</strong>g very few <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> habitat<br />

types that quail need to flourish. <strong>Bobwhite</strong>s have been <strong>in</strong> decl<strong>in</strong>e<br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Sou<strong>the</strong>ast for about a century, precipitously for <strong>the</strong> past 30<br />

years. From <strong>the</strong> historical descriptions, it is likely that bobwhites<br />

w e re more abundant <strong>in</strong> pre-colonial l<strong>and</strong>scapes than <strong>in</strong> those <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> pre s e n t .<br />

On most l<strong>and</strong>scapes across <strong>Alabama</strong>, quail occurrence is <strong>in</strong>cidental;<br />

chronically low, semi-isolated populations are now <strong>the</strong><br />

rule. Br<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>g quail back to some level <strong>of</strong> abundance on <strong>the</strong>se<br />

a reas re q u i res planned habitat developments, with emphasis on<br />

i n c reas<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> quantity <strong>and</strong> quality <strong>of</strong> re p roductive habitats.<br />

<strong>Bobwhite</strong>s are short-lived, annually produced animals. Eighty percent<br />

or more <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> birds alive dur<strong>in</strong>g early fall will be dead by <strong>the</strong><br />

next fall. Population levels,<br />

A c res (Millions)<br />

– 2 5<br />

– 2 0<br />

– 1 5<br />

– 1 0<br />

– 5<br />

– 0<br />

B o b w h i t e<br />

Population Tre n d<br />

A l a b a m a<br />

1 9 6 6 - 2 0 0 3<br />

t h e re f o re, are determ<strong>in</strong>ed by<br />

annual production, which is<br />

c o n t rolled by cover <strong>and</strong> environmental<br />

conditions that<br />

p revail dur<strong>in</strong>g each summer<br />

re p roductive season. S<strong>in</strong>ce<br />

quail populations can vary<br />

widely from year to year, bobwhite<br />

management re q u i re s<br />

constant vigilance. On locations<br />

where appropriate management<br />

practices have been<br />

rout<strong>in</strong>ely applied, quail numbers<br />

fluctuate annually with<br />

e n v i ronmental conditions,<br />

but have rema<strong>in</strong>ed abundant<br />

over time.<br />

<strong>Ecology</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Management</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Bobwhite</strong> <strong>Quail</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Alabama</strong> 9

Chapter 3<br />

H A B I TS<br />

REPRODUCTIVE ECOLOGY<br />

Breed<strong>in</strong>g Season<br />

Dur<strong>in</strong>g w<strong>in</strong>ter, bobwhites live <strong>in</strong> a covey, a group usually<br />

composed <strong>of</strong> 12 to 18 <strong>in</strong>dividuals. The covey moves <strong>and</strong> feeds<br />

toge<strong>the</strong>r on <strong>the</strong> ground dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> day, roosts on <strong>the</strong> ground <strong>in</strong> a<br />

tight circle to conserve heat a night, <strong>and</strong> functions as a unit to<br />

avoid predators. As spr<strong>in</strong>g approaches, <strong>the</strong> covey assembly, which<br />

s e rves bobwhites so well <strong>in</strong> w<strong>in</strong>ter, beg<strong>in</strong>s to weaken. Wa rm i n g<br />

days br<strong>in</strong>g on behavioral changes as pair-bond<strong>in</strong>g beg<strong>in</strong>s. Males<br />

<strong>of</strong>ten pair with females with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> covey, which at this time is<br />

composed <strong>of</strong> mostly unrelated <strong>in</strong>dividuals. Dur<strong>in</strong>g loaf<strong>in</strong>g period s ,<br />

covey members are more dispersed as pairs rest away from o<strong>the</strong>rs<br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> covey.<br />

The first “bobwhite” whistle usually happens <strong>in</strong> early to mid-<br />

April <strong>in</strong> <strong>Alabama</strong>, signal<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> breed<strong>in</strong>g season.<br />

O c c a s i o n a l l y, dur<strong>in</strong>g periods <strong>of</strong> unseasonably warm wea<strong>the</strong>r, male<br />

bobwhites may whistle as early as Febru a ry, or even <strong>in</strong> January.<br />

Most bobwhite call<strong>in</strong>g activity occurs from mid-June to mid-July<br />

at <strong>the</strong> height <strong>of</strong> nest<strong>in</strong>g season when hens are near <strong>the</strong> end <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>cubation <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir mates are left alone.<br />

Nest<strong>in</strong>g activity normally gets underway <strong>in</strong> late April, follow<strong>in</strong>g<br />

covey break-up. <strong>Bobwhite</strong>s are <strong>in</strong>determ<strong>in</strong>ate nesters <strong>and</strong><br />

will cont<strong>in</strong>ue to nest throughout <strong>the</strong> summer as long as wea<strong>the</strong>r<br />

<strong>and</strong> cover conditions are suitable. Mild summers with fre q u e n t<br />

ra<strong>in</strong>fall tend to be most favorable for nest<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> bro od rear<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>Alabama</strong>. Hot <strong>and</strong> droughty conditions dur<strong>in</strong>g breed<strong>in</strong>g season<br />

a re harmful to quail re p roductive success. Drought is especially<br />

detrimental to quail populations when re c u rrent over a period <strong>of</strong><br />

y e a r s .<br />

By <strong>the</strong> end <strong>of</strong> August most nests have hatched. Rare l y, a few<br />

nests may still be <strong>in</strong>cubated as late as October <strong>and</strong> hatch <strong>in</strong><br />

N o v e m b e r.<br />

Covey Dispersal <strong>and</strong> Individual Movements<br />

Coveys typically break up <strong>in</strong> late April, when <strong>the</strong> first nests<br />

a re constructed. Spr<strong>in</strong>g is a transitional period, <strong>and</strong> birds will re -<br />

jo<strong>in</strong> to loaf <strong>and</strong> roost as a group dur<strong>in</strong>g cold or <strong>in</strong>clement wea<strong>the</strong><br />

r. In <strong>Alabama</strong>, bobwhites typically move short distances, usually<br />

less than a mile, when shift<strong>in</strong>g from w<strong>in</strong>ter covey ranges to sum-<br />

The first “bobwhite” whistle usually happens <strong>in</strong> early to mid-April <strong>in</strong> <strong>Alabama</strong>,<br />

signal<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> breed<strong>in</strong>g season.<br />

JIM RAT H E RT/MISSOURI DEPT. OF CONSERVAT I O N<br />

In breed<strong>in</strong>g season bobwhites select weedy-grassy habitats. The summer home<br />

range <strong>of</strong> adult bobwhites is 30 to 40 acre s .<br />

S TAN STEWA RT<br />

10 <strong>Ecology</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Management</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Bobwhite</strong> <strong>Quail</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Alabama</strong>

mer breed<strong>in</strong>g ranges. Though uncommon, spr<strong>in</strong>g movements<br />

g reater than seven miles have been documented. 18<br />

In summer,<br />

b i rds are located <strong>in</strong> more open, grassy habitats compared to w<strong>in</strong>ter<br />

ranges, which are associated with woody <strong>and</strong> brushy pro t e c t i v e<br />

covers. The summer home range <strong>of</strong> adult bobwhites is 30 to 40<br />

a c re s .<br />

Mat<strong>in</strong>g Systems<br />

<strong>Bobwhite</strong>s exhibit a variety <strong>of</strong> mat<strong>in</strong>g systems. Dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong><br />

course <strong>of</strong> a breed<strong>in</strong>g season that <strong>in</strong>volves cont<strong>in</strong>uous mort a l i t y<br />

<strong>and</strong> varied mat<strong>in</strong>g systems to produce young, nearly all bre e d i n g<br />

b i rds will be associated with more than one mate. 6 , 1 0 , 1 2 Some pairs<br />

rema<strong>in</strong> toge<strong>the</strong>r dur<strong>in</strong>g nest<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> re-nest<strong>in</strong>g attempts. Some<br />

females mate <strong>and</strong> lay a clutch that is <strong>in</strong>cubated by <strong>the</strong> male. The<br />

hen may <strong>the</strong>n lay <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>cubate ano<strong>the</strong>r clutch alone, or mate <strong>and</strong><br />

p roduce a nest with ano<strong>the</strong>r male. Up to one-fourth <strong>of</strong> nests may<br />

be <strong>in</strong>cubated solely by males. 6 <strong>Bobwhite</strong> breed<strong>in</strong>g mechanisms act<br />

to overcome high natural mortality <strong>of</strong> nests, chicks, <strong>and</strong> adults,<br />

<strong>and</strong> to cope with wea<strong>the</strong>r changes dur<strong>in</strong>g breed<strong>in</strong>g season.<br />

Nest<strong>in</strong>g Behavior<br />

Pairs beg<strong>in</strong> build<strong>in</strong>g nests <strong>in</strong> late April. Natural herbaceous<br />

cover <strong>in</strong> open woods, fallow fields, field borders, fence rows <strong>and</strong><br />

roadsides are common nest locations. 5 1 Sites selected for nest cons<br />

t ruction characteristically have open, scattered growths <strong>of</strong> bunch<br />

type grasses that comb<strong>in</strong>e bare ground <strong>and</strong> overhead concealment.<br />

In <strong>Alabama</strong>, this ideal composition occurs <strong>in</strong> natural herbaceous<br />

plants that grew <strong>the</strong> previous summer <strong>and</strong> rema<strong>in</strong> st<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g for <strong>the</strong><br />

c u rrent nest<strong>in</strong>g season. 3 7 A mixed st<strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong> broomsedge, dewberry,<br />

b l a c k b e rry, legumes <strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r broad-leafed weeds provides ideal<br />

nest<strong>in</strong>g cover. Such cover types <strong>of</strong>fer dead grass (bro o m s e d g e )<br />

leaves for nest material. They are tall enough, about 18 <strong>in</strong>ches or<br />

m o re, to conceal <strong>the</strong> nest <strong>and</strong> birds. And, <strong>the</strong>y aff o rd open travel<br />

ways to <strong>and</strong> from <strong>the</strong> nest.<br />

<strong>Bobwhite</strong> nest sites typically have a mix <strong>of</strong> bunch grasses <strong>and</strong> broadleaf weeds<br />

that <strong>of</strong>fer bare ground <strong>and</strong> overhead concealment.<br />

J E R RY DEBIN<br />

<strong>Bobwhite</strong>s exhibit a variety <strong>of</strong> mat<strong>in</strong>g systems. Dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> course <strong>of</strong> a bre e d i n g<br />

season that <strong>in</strong>volves cont<strong>in</strong>uous mortality <strong>and</strong> varied mat<strong>in</strong>g systems to pro d u c e<br />

young, nearly all breed<strong>in</strong>g birds will be associated with more than one mate.<br />

JIM RAT H E RT/MISSOURI DEPT. OF CONSERVAT I O N<br />

Nest distribution is not uniform. Many nests may occur close<br />

t o g e t h e r. One four- a c re field <strong>in</strong> Tennessee, for example, was documented<br />

to conta<strong>in</strong> 41 bobwhite nests dur<strong>in</strong>g a s<strong>in</strong>gle nest<strong>in</strong>g season,<br />

12 <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se with eggs. 1 4 On l<strong>and</strong>scapes subjected to burn i n g ,<br />

d i s p ro p o rtionate numbers <strong>of</strong> nests are constructed <strong>in</strong> unburn e d<br />

a reas than <strong>in</strong> areas burned immediately preced<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> nest<strong>in</strong>g seas<br />

o n . 14 The male <strong>and</strong> female construct <strong>the</strong> nest <strong>of</strong> primarily dead<br />

grass material, <strong>of</strong>ten <strong>of</strong> broomsedge leaves. The nest may be placed<br />

<strong>in</strong> or at <strong>the</strong> base <strong>of</strong> a broomsedge clump for concealment. P<strong>in</strong>e<br />

needles are also used for nest material, especially where grass is<br />

sparse. The birds scratch <strong>and</strong> peck out a slight depression on bare<br />

g round, l<strong>in</strong>e it with dead grass blades, small leaves, plant stems or<br />

p<strong>in</strong>e needles <strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong>ten arch it over <strong>the</strong> top with dead grass, stems<br />

or needles. If nest material is scarce, as on ground just re c e n t l y<br />

b u rned, <strong>the</strong> arched top may not be present. Late summer nests<br />

may also be more poorly constructed, without an arched top. Such<br />

nests are more exposed <strong>and</strong> vulnerable to pre d a t i o n . 3 7<br />

Nest build<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> spr<strong>in</strong>g may occur over <strong>the</strong> course <strong>of</strong> a week<br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>clude construction or partial construction <strong>of</strong> nests that are<br />

never utilized. Once a nest site is chosen, <strong>the</strong> hen lays one egg<br />

<strong>Ecology</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Management</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Bobwhite</strong> <strong>Quail</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Alabama</strong> 11

F rom beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> nest build<strong>in</strong>g to hatch<strong>in</strong>g re q u i res about<br />

50 days, with early nests hatch<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> late May. 3 7 H o w e v e r, <strong>in</strong>cubation<br />

<strong>of</strong> most nests beg<strong>in</strong>s <strong>in</strong> late May <strong>and</strong> results <strong>in</strong> a first peak <strong>of</strong><br />

hatch<strong>in</strong>g around mid-June. Second <strong>and</strong> third hatch<strong>in</strong>g peaks may<br />

occur <strong>in</strong> July <strong>and</strong> August follow<strong>in</strong>g re-nest<strong>in</strong>g activity. The bobwhite<br />

range should be managed to make <strong>the</strong> most <strong>of</strong> first nest<strong>in</strong>g<br />

attempts <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> first hatch<strong>in</strong>g peak. 3 7 As summer pro g re s s e s ,<br />

wea<strong>the</strong>r becomes hotter, dryer <strong>and</strong> less favorable for nest<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

Fewer birds are alive to breed, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> breed<strong>in</strong>g condition <strong>of</strong><br />

rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g birds decl<strong>in</strong>es.<br />

Nest<strong>in</strong>g eff o rt varies significantly with ra<strong>in</strong>fall fluctuations. In<br />

<strong>Alabama</strong>, above average July <strong>and</strong> August ra<strong>in</strong>fall <strong>in</strong>creases <strong>and</strong><br />

extends nest<strong>in</strong>g. Summer drought ends nest<strong>in</strong>g activity pre m a-<br />

t u re l y. 4 1 Dur<strong>in</strong>g very hot <strong>and</strong> dry wea<strong>the</strong>r hens may not attempt to<br />

nest, but shortly after summer ra<strong>in</strong>s that create moist, warm conditions<br />

<strong>and</strong> new plant growth, nest<strong>in</strong>g activity re s u m e s . 2 5<br />

Most nests are not successful. Only one-third to one-half <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>cubated nests results <strong>in</strong> a bro od . 4 1 , 5 1 Of those hens alive at <strong>the</strong><br />

beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> breed<strong>in</strong>g season, less than half hatch a nest, 5 3 a con-<br />

<strong>Bobwhite</strong> nests are <strong>of</strong>ten placed <strong>in</strong> or at <strong>the</strong> base <strong>of</strong> a broomsedge clump for con -<br />

cealment. Look closely for <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>cubat<strong>in</strong>g hen on <strong>the</strong> nest.<br />

J E R RY DEBIN<br />

each day until <strong>the</strong> clutch is complete. Clutches average 12 eggs. 1 5 , 4 1<br />

Incubation beg<strong>in</strong>s after <strong>the</strong> clutch is laid <strong>and</strong> re q u i res 24 days. The<br />

female <strong>and</strong> male do not share <strong>in</strong>cubation. Some males <strong>in</strong>cubate<br />

<strong>the</strong> nest solely, or may take over <strong>in</strong>cubation if <strong>the</strong> hen is killed.<br />

Once <strong>in</strong>cubation beg<strong>in</strong>s, <strong>the</strong> bird stays on <strong>the</strong> nest except for<br />

s h o rt periods, dur<strong>in</strong>g which time it leaves <strong>the</strong> nest to feed.<br />

Incubat<strong>in</strong>g birds need an abundance <strong>of</strong> foods near <strong>the</strong> nest site.<br />

This allows <strong>the</strong>m to forage nearby, quickly rega<strong>in</strong> energ y, <strong>and</strong><br />

reduce <strong>the</strong>ir time away from <strong>the</strong> nest. Dewberries <strong>and</strong> blackberr i e s<br />

a re pre f e rred foods dur<strong>in</strong>g nest<strong>in</strong>g season. Insects <strong>and</strong> early matur<strong>in</strong>g<br />

seeds are also important food s .<br />

F rom beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> nest build<strong>in</strong>g to hatch<strong>in</strong>g re q u i res about 50 days, with a first<br />

peak <strong>of</strong> hatch<strong>in</strong>g around mid-June.<br />

J E R RY DEBIN<br />

About thre e - f o u rths <strong>of</strong> hens <strong>and</strong> one-fourth <strong>of</strong> males that survive <strong>the</strong> bre e d i n g<br />

season hatch a bro o d .<br />

N O RTH CAROLINA WILDLIFE RESOURCES COMMISSION<br />

12 <strong>Ecology</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Management</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Bobwhite</strong> <strong>Quail</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Alabama</strong>

P redators cause at least thre e - f o u rths <strong>of</strong> nest failures. The destroyed nest <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

b a c k g round <strong>and</strong> re c o v e red radio <strong>of</strong> a telemetered hen <strong>in</strong>dicate a mammalian<br />

p re d a t o r.<br />

J E R RY DEBIN<br />

sequence <strong>of</strong> cont<strong>in</strong>uous breed<strong>in</strong>g season mort a l i t y. 5 <strong>Bobwhite</strong>s are<br />

persistent nesters, <strong>and</strong> most hens (about thre e - f o u rths) surv i v i n g<br />

at <strong>the</strong> end <strong>of</strong> breed<strong>in</strong>g season hatch a successful nest due to re -<br />

n e s t i n g . 12<br />

In addition, male <strong>in</strong>cubation <strong>of</strong> nests contributes substantially<br />

to annual production. Males <strong>in</strong>cubate more than onef<br />

o u rth <strong>of</strong> nests. 6 Of those males alive at <strong>the</strong> end <strong>of</strong> breed<strong>in</strong>g season,<br />

one-fourth hatch a bro od . 6<br />

Most hens that fail on an <strong>in</strong>itial nest<strong>in</strong>g attempt will re - n e s t .<br />

Because <strong>of</strong> high nest losses, hens must <strong>in</strong>itiate two or three nests<br />

to produce one that is successful. 33<br />

Attempts to raise second<br />

b ro ods, after successfully rais<strong>in</strong>g a first bro od, are not uncommon.<br />

In an <strong>Alabama</strong> study, four <strong>of</strong> 16 radio-marked hens successfully<br />

hatch<strong>in</strong>g first bro ods re-nested, <strong>and</strong> two successfully hatched second<br />

bro od s . 42 Although rare, third bro ods have been documented<br />

<strong>in</strong> early-lay<strong>in</strong>g hens. 28 Though multiple bro ods occur, <strong>the</strong>ir usual<br />

<strong>in</strong>cidence makes only m<strong>in</strong>or numerical diff e rence <strong>in</strong> autumn bobwhite<br />

populations. 19 Double clutches are a regular component <strong>of</strong><br />

bobwhite re p roduction, but are not necessary to replace populations<br />

dur<strong>in</strong>g normal conditions. 34 Variation <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> rate <strong>of</strong> second<br />

clutches could substantially affect re p rod u c t i o n , 6 primarily when<br />

bobwhites are recover<strong>in</strong>g from population lows.<br />

The largest contributor to nest loss is depredation by egg eat<strong>in</strong>g<br />

predators. Predators account for at least thre e - f o u rths <strong>of</strong> nest<br />

f a i l u res. Nest depredations along with predation <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>cubat<strong>in</strong>g<br />

adults, both on <strong>and</strong> away from <strong>the</strong> nest, may account for 90 to 100<br />

p e rcent <strong>of</strong> nest losses. 12 , 41 Nest predators <strong>in</strong>clude snakes, raccoons,<br />

opossums, skunks, armadillos, rats, weasels, squirrels, foxes, coyotes,<br />

bobcats, dogs, cats, hogs, turkeys, crows, jays <strong>and</strong> ants. The<br />

list <strong>of</strong> egg-destroy<strong>in</strong>g predators is so long that it becomes appare n t<br />

that nest predation cannot be elim<strong>in</strong>ated. However, nest pre d a-<br />

tion can be moderated by habitat management <strong>and</strong> judicious cont<br />

rol <strong>of</strong> major egg predators. Nest predation is generally highest<br />

early <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> nest<strong>in</strong>g season <strong>and</strong> decl<strong>in</strong>es as summer pro g re s s e s .<br />

This is <strong>the</strong> time when cover is greater <strong>and</strong> alternative pre d a t o r<br />

f o ods such as fruits <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>sects are abundant. Nest depre d a t i o n s<br />

a re also higher dur<strong>in</strong>g dry summers when covers are th<strong>in</strong>ner <strong>and</strong><br />

natural food production is low. The bobwhite’s persistence to re -<br />

nest helps overcome high nest losses.<br />

Adult mortality contributes substantially to nest failure. An<br />

<strong>Alabama</strong> study documented that about one-fourth <strong>of</strong> all unsuccessful<br />

nests resulted from death <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>cubat<strong>in</strong>g hen <strong>and</strong> that<br />

m o rtality was greatest dur<strong>in</strong>g recesses away from <strong>the</strong> nest. 41 In <strong>the</strong><br />

s t u d y, <strong>the</strong> predation rate <strong>of</strong> adult bobwhite hens dur<strong>in</strong>g bre e d i n g<br />

season was 60 percent <strong>and</strong> most losses were to avian pre d a t o r s .<br />

Nest ab<strong>and</strong>onment can result <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> failure <strong>of</strong> 10 to 20 percent<br />

<strong>of</strong> nests. 12 , 51 Reasons for ab<strong>and</strong>onment are not always apparent,<br />

but birds are sensitive to disturbance dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> lay<strong>in</strong>g period<br />

<strong>and</strong> will readily desert <strong>the</strong> nest. 51<br />

Human disturbance, such as<br />

mow<strong>in</strong>g agricultural areas dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> nest<strong>in</strong>g season, causes nest<br />

d e s e rtion <strong>and</strong> destru c t i o n . 34<br />

F l o od<strong>in</strong>g, heavy ra<strong>in</strong>s <strong>and</strong> extre m e<br />

d rought also contribute to nest ab<strong>and</strong>onment. 51<br />

The total number <strong>of</strong> nests produced each season 14 <strong>and</strong> number<br />

<strong>of</strong> chicks hatched 34 (nest<strong>in</strong>g success) are <strong>the</strong> primary determ i-<br />

nants <strong>of</strong> annual quail production <strong>and</strong> quail population fluctuations.<br />

Small diff e rences <strong>in</strong> nest<strong>in</strong>g success dramatically affect <strong>the</strong><br />

numbers <strong>of</strong> juvenile birds <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> fall population 19 <strong>and</strong> may mean<br />

<strong>the</strong> diff e rence between an <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g or a decl<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g population. 51<br />

H a t c h i n g<br />

A couple <strong>of</strong> days before <strong>in</strong>cubation ends <strong>the</strong> chicks beg<strong>in</strong> to<br />

peep <strong>and</strong> pip <strong>the</strong>ir shells. With its egg tooth, <strong>the</strong> heav<strong>in</strong>g chick<br />

eventually cracks a small hole <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> shell near <strong>the</strong> large end <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

egg. Once a hole is made hatch<strong>in</strong>g pro g resses rapidly as <strong>the</strong> chick<br />

pips an arc around <strong>the</strong> large end <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> shell until <strong>the</strong> area is weak<br />

enough for <strong>the</strong> chick to push <strong>the</strong> “h<strong>in</strong>ged” portion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> shell fre e<br />

<strong>and</strong> emerge. Most <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> eggs will hatch with<strong>in</strong> an hour or so <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> first chick’s emergence. In over half <strong>the</strong> nests, all eggs hatch.<br />

On average, about 8 percent <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>cubated eggs do not hatch due<br />

to <strong>in</strong>fertility or dead embry o s . 3 4 In <strong>the</strong> warm summer air, <strong>the</strong> wet<br />

chicks dry quickly as <strong>the</strong> parent on <strong>the</strong> nest fluffs out its fea<strong>the</strong>rs<br />

<strong>and</strong> bro ods <strong>the</strong>m. The active bro od is led away from <strong>the</strong> nest, usually<br />

with<strong>in</strong> a few hours <strong>of</strong> hatch<strong>in</strong>g. If a hen hatched <strong>the</strong> bro od ,<br />

<strong>the</strong> family may jo<strong>in</strong> with <strong>the</strong> cock bird wait<strong>in</strong>g nearby.<br />

Brood Rear<strong>in</strong>g<br />

The newly hatched chicks only weigh about six to seven<br />

grams each, less than a quarter <strong>of</strong> an ounce. They are alert <strong>and</strong> can<br />

move quickly to hide <strong>and</strong> “freeze” when confronted with danger<br />

while <strong>the</strong> parent(s) may perf o rm a crippled w<strong>in</strong>g act to lead an<br />

enemy away. The chicks feed at once, search<strong>in</strong>g for small <strong>in</strong>sects,<br />

tender leaves, berries <strong>and</strong> seeds. Most <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> time dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> first<br />

week is spent bro od<strong>in</strong>g. A parent fluffs out its fea<strong>the</strong>rs to cover <strong>the</strong><br />

downy chicks <strong>and</strong> keep <strong>the</strong>m from gett<strong>in</strong>g chilled or takes <strong>the</strong>m<br />

<strong>in</strong>to a shady area to escape heat. The chicks may be bro oded by<br />

one or both parents. Ab<strong>and</strong>oned bro ods <strong>and</strong> orphaned chicks are<br />

<strong>of</strong>ten adopted <strong>and</strong> raised by lone adults, both female <strong>and</strong> male. 12<br />

By <strong>the</strong> end <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> first week <strong>the</strong> chicks’ w<strong>in</strong>gs are stro n g<br />

enough for <strong>the</strong>m to fly a few feet, <strong>and</strong> by two weeks <strong>of</strong> age <strong>the</strong>y<br />

will flush when disturbed. Dur<strong>in</strong>g this time <strong>the</strong> weekly home<br />

range <strong>of</strong> bro ods may vary from as small as four acres up to about 15<br />

a c res <strong>in</strong> size. 41<br />

The chicks feed almost cont<strong>in</strong>uously. Their diet<br />

consists predom<strong>in</strong>antly <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>sects — mostly beetles, true bugs <strong>and</strong><br />

small grasshoppers — as well as some caterpillars, moths <strong>and</strong> spid<br />

e r s . 22 , 51<br />

The seeds <strong>of</strong> early matur<strong>in</strong>g grasses, primarily those <strong>of</strong><br />

panic grasses, are also taken frequently by chicks. 22<br />

The adults,<br />

p a rticularly <strong>the</strong> hen, are feed<strong>in</strong>g on <strong>the</strong> same <strong>in</strong>sects, although<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir diet still mostly consists <strong>of</strong> s<strong>of</strong>t fruits <strong>and</strong> weed <strong>and</strong> grass<br />

seeds. In summer, quail are <strong>of</strong>ten tak<strong>in</strong>g fruits <strong>and</strong> seeds dire c t l y<br />

f rom plants, seed pods, <strong>and</strong> seed heads, whereas <strong>in</strong> w<strong>in</strong>ter <strong>the</strong>y are<br />

retriev<strong>in</strong>g seeds fallen to <strong>the</strong> gro u n d . 51<br />

M o re than half <strong>of</strong> quail chicks die with<strong>in</strong> two weeks <strong>of</strong> hatch<strong>in</strong>g,<br />

mostly from pre d a t i o n . 12 , 41 After two weeks <strong>of</strong> growth, chicks<br />

experience much lower mort a l i t y. By this time <strong>the</strong>y are fea<strong>the</strong>re d<br />

enough for short flights <strong>and</strong> can better escape predators. After <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Ecology</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Management</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Bobwhite</strong> <strong>Quail</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Alabama</strong> 13

M o re than half <strong>of</strong> quail chicks die with<strong>in</strong> two weeks <strong>of</strong> hatch<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

N O RTH CAROLINA WILDLIFE RESOURCES COMMISSION<br />

age <strong>of</strong> two weeks, <strong>the</strong>ir diet shifts to <strong>in</strong>clude more s<strong>of</strong>t fru i t s ,<br />

b e rries <strong>and</strong> grass seeds. <strong>Quail</strong> populations are highest, however<br />

b r i e f l y, <strong>in</strong> mid-summer after most nests have hatched. This population<br />

high does not last long because so many chicks die with<strong>in</strong><br />

two weeks <strong>of</strong> hatch<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

At three to five weeks <strong>of</strong> age bro ods are capable <strong>of</strong> surv i v i n g<br />

<strong>in</strong>dependently <strong>of</strong> parents. Some hens ab<strong>and</strong>on bro ods by this time<br />

<strong>and</strong> re - n e s t . 41 By this age <strong>the</strong> bro ods may have ranged over more<br />

than 40 acre s . 4 1 At seven weeks <strong>of</strong> age, <strong>the</strong> young birds roost <strong>in</strong> a<br />

c i rcle as <strong>the</strong> adults <strong>and</strong> survive ra<strong>in</strong>storms without bro od<strong>in</strong>g. At<br />

eight weeks hens <strong>and</strong> cocks are identifiable by <strong>the</strong> respective buff<br />

or white <strong>and</strong> black throat patch. They weigh a little more than<br />

half that <strong>of</strong> adults <strong>and</strong> are capable <strong>of</strong> strong flights <strong>of</strong> 100 yards or<br />

m o re. They are <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly feed<strong>in</strong>g on summer matur<strong>in</strong>g grass<br />

<strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r seeds. At 12 weeks <strong>the</strong>y are nearly mature <strong>in</strong> size <strong>and</strong><br />

weight, <strong>and</strong> at 15 weeks <strong>the</strong>ir plumage is almost <strong>in</strong>dist<strong>in</strong>guishable<br />

f rom that <strong>of</strong> adults. Fully grown birds, at least 21 weeks old, are<br />

165 to 180 grams <strong>in</strong> weight, or about six ounces. 3 7<br />

Out <strong>of</strong> a successful bobwhite nest <strong>of</strong> 12 eggs, about 11 eggs<br />

hatch, five chicks are alive after two weeks, <strong>and</strong> three or four<br />

chicks make it <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> fall population. Based on average population<br />

dynamics, if one-third <strong>of</strong> quail chicks survive to autumn, 80<br />

p e rcent <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> fall population will be birds produced that year, <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> quail population will have doubled from spr<strong>in</strong>g to fall. This is<br />

g o od production. In less productive years, <strong>the</strong> quail population<br />

does not double itself from spr<strong>in</strong>g through summer.<br />

The quail population at its autumn high may average six or<br />

m o re young birds per surviv<strong>in</strong>g adult hen <strong>in</strong> a good prod u c t i o n<br />

y e a r. Dur<strong>in</strong>g excessively hot <strong>and</strong> dry summers, production may be<br />

t h ree or fewer young per hen. Of those birds that make up an<br />

autumn population, 20 percent or less will survive to <strong>the</strong> follow<strong>in</strong>g<br />

autumn.<br />

FALL AND WINTER BEHAV I O R<br />

Covey Formation <strong>and</strong> W<strong>in</strong>ter Range Selection<br />

The covey assembly is a behavior mechanism that pro m o t e s<br />

bobwhite survival dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> harsh environment <strong>of</strong> w<strong>in</strong>ter.<br />

Concentration <strong>of</strong> birds <strong>in</strong>to a group lowers <strong>the</strong> chance <strong>of</strong> encounters<br />

with predators, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> watchful eyes <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> group assist <strong>in</strong><br />

p redator detection. The close association <strong>of</strong> birds <strong>in</strong>to a ro o s t i n g<br />

disk conserves heat <strong>and</strong> energy dur<strong>in</strong>g cold w<strong>in</strong>ter nights. In<br />

autumn, bobwhite coveys form <strong>in</strong>to group sizes that are pre s u m-<br />

ably optimal for fall <strong>and</strong> w<strong>in</strong>ter survival. Fall coveys space <strong>the</strong>mselves<br />

on ranges that have accessible food sources near pro t e c t i v e<br />

c o v e r.<br />

Dur<strong>in</strong>g late summer <strong>and</strong> early fall, large associations <strong>of</strong> bird s<br />

may be encountered. Several adults with bro ods <strong>of</strong> various ages<br />

f o rm large comb<strong>in</strong>ation coveys <strong>of</strong> 30 or more birds. These are<br />

<strong>of</strong>ten encountered <strong>in</strong> field areas where weed growth is at its rankest<br />

<strong>and</strong> large quantities <strong>of</strong> seeds are beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g to fall. As nights<br />

become chilly <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> weed covers th<strong>in</strong>, <strong>the</strong> birds re - f o rm <strong>in</strong>to<br />

smaller w<strong>in</strong>ter coveys <strong>of</strong> 12 to 18 birds. This is <strong>the</strong> fall shuff l e .<br />