Paper Conservation: Decisions & Compromises

Paper Conservation: Decisions & Compromises Paper Conservation: Decisions & Compromises

Fig. 2: Manuscript of the cofre no. 24: Deformation in the text block caused by the binding. sian illuminators of the 15 th century. This manuscript, kept inside a strongbox in the Library of the Mafra National Palace, characterized by low and stable temperature levels, is now in reasonable conservation conditions. The problem We came across a codex that had suffered several interventions at the level of bookbinding, which was replaced in late 18th early 19th centuries, contributing to the overall deterioration of the manuscript (Figure 2). The deteriorated bookbinding, that is accompanying the manuscript, no longer meets its essential goal, enabling the safe and secure manuscript’s handling. We took into account two hypotheses when considering the need to rebind the codex: 1 recovering the 18th/19th century binding; 2 making a new binding following the original 15th century style. It seemed more appropriate to choose the first Fig. 3: The body of the book is currently composed by 23 sections, from which five presented modifications. In section II, three original leaves were removed, resulting in discontinuity of text. option, since there was no evidence of an early bookbinding. Proper conservation of the current bookbinding would stabilize the movement of the parchment sheets and therefore it is the first step for the stabilization of the pictorial layers. In sections V, XV, and XX one folium was removed and replaced, probably in the second half of the 15th century, by two thicker parchments, with illuminations. In the case of the first two the illuminations were assembled in a puzzle like fashion. Finally, in the case of section XXIII, it presented a ‘collage’ of four leaves along the hinge area. The changes led to an imbalance of the whole and contributed to the deformation of the body of the book and degradation of the binding structure, affecting the entire codex. However, sections III, VII and XVIII, which were originally designed for the absence of a folium, also contributed to this disparity. Regarding the text block, two hypotheses were discussed by the team and with the Mafra curators: 1 insertion of a sheet of parchment on the all signatures that presented unevenness; 2 inclusion of only three sheets of parchment on section II, since this was the only truncated section. The last option was chosen, respecting the original historical evidence and the principle of minimum intervention. Conservation condition Deterioration was observed on the leather cover, namely surface soil, general wear, and missing areas of card and leather, especially in the spine and board corners, some caused by insects. The tight binding, related to the production period, was affected by incorrect handling causing stress on the spine and breaking the sewing. This meant that the manuscript was dismantled, with several loose signatures. In general, the support of parchment seems stable under visual damage assessment (using IDAP parameters; IDAP, 2008), but shows surface dirt and residues of animal glue, especially along the bifolia hinge area. Also observed were some gaps, caused by the sewing tension, and, in smaller amounts, tears in the fore edge of leaves. While in acceptable condition, the text showed areas of ink fading and areas of loose pigment due to poor adhesion of the different pictorial layers to the support. This condition is most evident in green, blue and white colors, probably due to the grain size of these pigments or low amount of binder. However, the hygroscopicity of parchment leads to its ICOM-CC Graphic Documents Working Group Interim Meeting | Vienna 17 – 19 April 2013 98

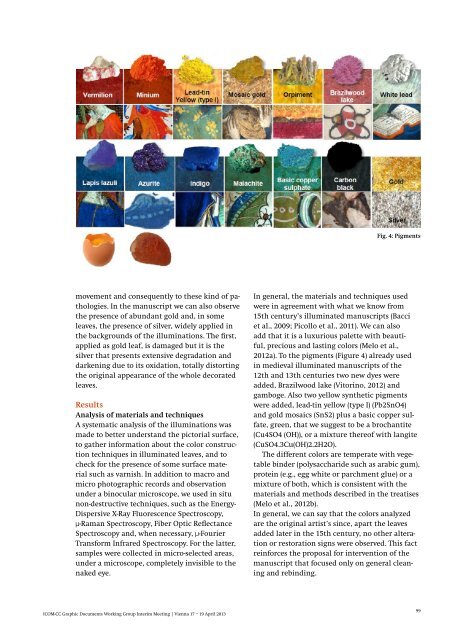

Fig. 4: Pigments movement and consequently to these kind of pathologies. In the manuscript we can also observe the presence of abundant gold and, in some leaves, the presence of silver, widely applied in the backgrounds of the illuminations. The first, applied as gold leaf, is damaged but it is the silver that presents extensive degradation and darkening due to its oxidation, totally distorting the original appearance of the whole decorated leaves. Results Analysis of materials and techniques A systematic analysis of the illuminations was made to better understand the pictorial surface, to gather information about the color construction techniques in illuminated leaves, and to check for the presence of some surface material such as varnish. In addition to macro and micro photographic records and observation under a binocular microscope, we used in situ non-destructive techniques, such as the Energy- Dispersive X-Ray Fluorescence Spectroscopy, μ-Raman Spectroscopy, Fiber Optic Reflectance Spectroscopy and, when necessary, μ-Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy. For the latter, samples were collected in micro-selected areas, under a microscope, completely invisible to the naked eye. In general, the materials and techniques used were in agreement with what we know from 15th century’s illuminated manuscripts (Bacci et al., 2009; Picollo et al., 2011). We can also add that it is a luxurious palette with beautiful, precious and lasting colors (Melo et al., 2012a). To the pigments (Figure 4) already used in medieval illuminated manuscripts of the 12th and 13th centuries two new dyes were added, Brazilwood lake (Vitorino, 2012) and gamboge. Also two yellow synthetic pigments were added, lead-tin yellow (type I) (Pb2SnO4) and gold mosaics (SnS2) plus a basic copper sulfate, green, that we suggest to be a brochantite (Cu4SO4 (OH)), or a mixture thereof with langite (CuSO4.3Cu(OH)2.2H2O). The different colors are temperate with vegetable binder (polysaccharide such as arabic gum), protein (e.g., egg white or parchment glue) or a mixture of both, which is consistent with the materials and methods described in the treatises (Melo et al., 2012b). In general, we can say that the colors analyzed are the original artist’s since, apart the leaves added later in the 15th century, no other alteration or restoration signs were observed. This fact reinforces the proposal for intervention of the manuscript that focused only on general cleaning and rebinding. ICOM-CC Graphic Documents Working Group Interim Meeting | Vienna 17 – 19 April 2013 99

- Page 48 and 49: Evaluation of stochiometric effects

- Page 50 and 51: Practice and Progress in the Conser

- Page 52 and 53: Fig. 1 Fig. 2 plex picture and prov

- Page 54 and 55: Fig. 2: Coloured paper strips place

- Page 56 and 57: the fire (on the other hand paper,

- Page 58 and 59: inform decisions on conservation tr

- Page 60 and 61: This paper summarizes what is known

- Page 62 and 63: 2. Methods An interdisciplinary met

- Page 64 and 65: Fig. 4: Dyed endpaper pasted at the

- Page 66 and 67: Preservation of Architectural Drawi

- Page 68 and 69: Notes 1 According Salvador Muñoz V

- Page 70 and 71: course of time under the influence

- Page 72 and 73: the curators in review of the treat

- Page 74 and 75: cellulose powders with cellulose et

- Page 76 and 77: Authors Xing Kung Liao Conservator

- Page 78 and 79: Fig. 2: Our Railroad Workers and th

- Page 80 and 81: The Restoration of Cartoons at the

- Page 82 and 83: tation presumes that the works are

- Page 84 and 85: To Remove or Retain? - Extensive In

- Page 86 and 87: Fig. 4 repeated applications until

- Page 88 and 89: The Migration of Hydroxy Propyl Cel

- Page 90: tion issue allowed a visualisation

- Page 93 and 94: Ethical Considerations Concerning t

- Page 95 and 96: emoved with damp cotton swab. Then

- Page 97: Conservation of a Book of Hours fro

- Page 101 and 102: Notes 1 Brazilwood lake, lapis lazu

- Page 103 and 104: pages, which would easily have torn

- Page 105 and 106: The Microflora Inhabiting Leonardo

- Page 107 and 108: Acknowledgments The authors would l

- Page 109 and 110: Microorganisms in Books - First Res

- Page 111 and 112: hyaline white mycelia on and in the

- Page 113 and 114: Deconstructing the Reconstruction E

- Page 115 and 116: Fig. 3: Poster after 2012 conservat

- Page 117 and 118: Conservators’ Investigation of Ch

- Page 119 and 120: had been used, may be false-positiv

- Page 121 and 122: function will provide a holistic pi

- Page 123 and 124: Fig. 2: Patriarchs of Chan Buddhism

- Page 125 and 126: ing techniques, which build upon fu

- Page 127 and 128: Applications of Image Processing So

- Page 129 and 130: Fig. 3 Fig. 4 images in a single wi

- Page 131 and 132: Analysing Deterioration Artifacts i

- Page 133 and 134: Fig. 3 similarity maps. Similarity

- Page 135 and 136: Strategy in the Case of a Wrecked P

- Page 137 and 138: without preliminary consolidation.

- Page 139 and 140: Fiber Optic Reflectance Spectroscop

- Page 141 and 142: Fig. 3: 18 th century paper seal, i

- Page 143 and 144: Fig. 3 Fig. 4 of responsibilities r

- Page 145 and 146: Characterising the Origin of Carbon

- Page 147: Fig. 3: Sampling depth for ATR spec

Fig. 4: Pigments<br />

movement and consequently to these kind of pathologies.<br />

In the manuscript we can also observe<br />

the presence of abundant gold and, in some<br />

leaves, the presence of silver, widely applied in<br />

the backgrounds of the illuminations. The first,<br />

applied as gold leaf, is damaged but it is the<br />

silver that presents extensive degradation and<br />

darkening due to its oxidation, totally distorting<br />

the original appearance of the whole decorated<br />

leaves.<br />

Results<br />

Analysis of materials and techniques<br />

A systematic analysis of the illuminations was<br />

made to better understand the pictorial surface,<br />

to gather information about the color construction<br />

techniques in illuminated leaves, and to<br />

check for the presence of some surface material<br />

such as varnish. In addition to macro and<br />

micro photographic records and observation<br />

under a binocular microscope, we used in situ<br />

non-destructive techniques, such as the Energy-<br />

Dispersive X-Ray Fluorescence Spectroscopy,<br />

μ-Raman Spectroscopy, Fiber Optic Reflectance<br />

Spectroscopy and, when necessary, μ-Fourier<br />

Transform Infrared Spectroscopy. For the latter,<br />

samples were collected in micro-selected areas,<br />

under a microscope, completely invisible to the<br />

naked eye.<br />

In general, the materials and techniques used<br />

were in agreement with what we know from<br />

15th century’s illuminated manuscripts (Bacci<br />

et al., 2009; Picollo et al., 2011). We can also<br />

add that it is a luxurious palette with beautiful,<br />

precious and lasting colors (Melo et al.,<br />

2012a). To the pigments (Figure 4) already used<br />

in medieval illuminated manuscripts of the<br />

12th and 13th centuries two new dyes were<br />

added, Brazilwood lake (Vitorino, 2012) and<br />

gamboge. Also two yellow synthetic pigments<br />

were added, lead-tin yellow (type I) (Pb2SnO4)<br />

and gold mosaics (SnS2) plus a basic copper sulfate,<br />

green, that we suggest to be a brochantite<br />

(Cu4SO4 (OH)), or a mixture thereof with langite<br />

(CuSO4.3Cu(OH)2.2H2O).<br />

The different colors are temperate with vegetable<br />

binder (polysaccharide such as arabic gum),<br />

protein (e.g., egg white or parchment glue) or a<br />

mixture of both, which is consistent with the<br />

materials and methods described in the treatises<br />

(Melo et al., 2012b).<br />

In general, we can say that the colors analyzed<br />

are the original artist’s since, apart the leaves<br />

added later in the 15th century, no other alteration<br />

or restoration signs were observed. This fact<br />

reinforces the proposal for intervention of the<br />

manuscript that focused only on general cleaning<br />

and rebinding.<br />

ICOM-CC Graphic Documents Working Group Interim Meeting | Vienna 17 – 19 April 2013<br />

99