Distinctly Dutch - New York State Museum

Distinctly Dutch - New York State Museum

Distinctly Dutch - New York State Museum

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

The Magazine<br />

of the<br />

<strong>New</strong> <strong>York</strong><br />

<strong>State</strong> <strong>Museum</strong><br />

Vol. 5 • No. 1<br />

summer 2009<br />

INSIDE:<br />

1609 Exhibition<br />

An Up Close Look<br />

at Micro Minerals<br />

Schuyler Flatts Research<br />

Mohawk Globe Basket<br />

<strong>New</strong> Collections<br />

and Publications<br />

<strong>Distinctly</strong> <strong>Dutch</strong><br />

<strong>Dutch</strong> <strong>New</strong> <strong>York</strong> lives on through the material<br />

culture preserved in the <strong>Museum</strong>’s collection Page 18

Book Smarts<br />

For more than 170 years, <strong>Museum</strong> publications have shared knowledge of anthropology,<br />

biology, geology, history, and paleontology with readers excited by discovery.<br />

In <strong>Museum</strong> Bulletin #509,<br />

Before Albany, An Archaeology<br />

of Native-<strong>Dutch</strong> Relations in<br />

the Capital Region, 1600–1664,<br />

author Dr. James W. Bradley<br />

explores the interaction<br />

between Native Americans<br />

and the <strong>Dutch</strong> settlers living<br />

in the Beverwijck settlement,<br />

now present-day Albany. He<br />

discusses the mutual respect<br />

between the two groups<br />

and how, despite some<br />

conflicts, they established<br />

reciprocal relationships that<br />

led to the settlement of the<br />

Capital Region.<br />

230 pages, 8 1 /8 x 9 3 /4 inches<br />

<strong>Museum</strong> Bulletin #502, Natural<br />

History of the Albany Pine Bush,<br />

is a comprehensive field guide<br />

to the trees, shrubs, wildflowers,<br />

insects, amphibians, reptiles,<br />

birds, and mammals that<br />

inhabit one of the most<br />

endangered landscapes in the<br />

Northeast. Author Dr. Jeffrey K.<br />

Barnes also reviews the human<br />

exploitation, land use, and<br />

conservation of the area as<br />

well as the challenges related<br />

to its ecological management.<br />

245 pages, 6 x 9 inches<br />

<strong>Museum</strong> Bulletin #505, James<br />

Eights, 1798–1882, Antarctic<br />

Explorer, Albany Naturalist,<br />

His Life, His Times, His Work,<br />

presents a synopsis of the life<br />

and times of a little-known<br />

but respected 19th century<br />

scientist from Albany. Author<br />

Dr. Daniel McKinley brings to<br />

life Eights’ professional career<br />

and recognizes his contributions<br />

to science. Interested in various<br />

fields of natural history, James<br />

Eights explored extensively in<br />

<strong>New</strong> <strong>York</strong> and donated many<br />

of the biological and geological<br />

specimens he collected to the<br />

<strong>State</strong> <strong>Museum</strong>.<br />

456 pages, 8 1 /2 x 11 inches<br />

<strong>Museum</strong> Bulletin #507,<br />

Fabulous Fossils: 300 Years of<br />

Worldwide Research on<br />

Trilobites, documents the history<br />

of research on this fascinating<br />

group of prehistoric animals.<br />

This collection of 15 papers,<br />

written by internationally<br />

renowned scientists, is a significant<br />

contribution to the history<br />

of trilobite paleontology. The<br />

book was edited by Dr. Donald<br />

G. Mikulic, Dr. Ed Landing<br />

of the <strong>State</strong> <strong>Museum</strong>, and<br />

Dr. Joanne Kluessendorf.<br />

248 pages, 8 1 /2 x 11 inches<br />

For information about these and other titles, call 518-486-2013 or visit www.nysm.nysed.gov/publications.

contents<br />

Vol. 5 • No. 1<br />

summer 2009<br />

features<br />

12<br />

17<br />

18<br />

Understanding a Mohawk Globe<br />

Basket in Its Makers’ World<br />

by Dr. Betty J. Duggan<br />

To fully appreciate the Globe Basket,<br />

commissioned in 2006 and now on<br />

display at the <strong>Museum</strong>, it’s important<br />

to learn the story of the basket’s<br />

creation, including its intended<br />

meanings and experiences of its<br />

makers, the Benedict family of the<br />

Akwesasne Mohawk community.<br />

NYSM In Person<br />

A familiar face around the <strong>Museum</strong>,<br />

Ryan Fitzpatrick of Visitor Services can<br />

be seen welcoming student groups,<br />

providing information about living or<br />

extinct fauna in the state, introducing<br />

children to the fish and turtle in<br />

Discovery Place, leading educational<br />

programs for Time Tunnel campers,<br />

and more.<br />

<strong>Distinctly</strong> <strong>Dutch</strong><br />

by John L. Scherer<br />

For more than 150 years after <strong>New</strong><br />

Netherland became <strong>New</strong> <strong>York</strong>, <strong>Dutch</strong><br />

culture remained dominant. Furniture,<br />

decorative pieces, and other material<br />

culture from the 18th century preserve<br />

our state’s <strong>Dutch</strong> heritage.<br />

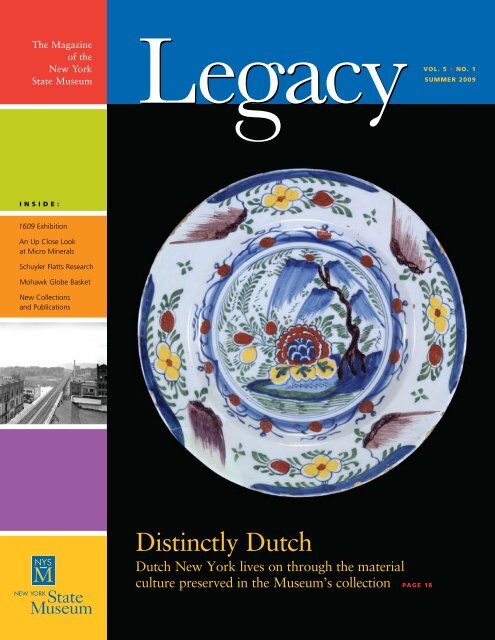

On the Cover: <strong>Dutch</strong> Delft Charger, c. 1760,<br />

originally owned by Conrad Anthony Ten Eyck<br />

(1789–1845) and his wife Hester Gansevoort<br />

(1796–1861) of Albany. They may have inherited<br />

the charger from either of their parents. <strong>Museum</strong><br />

purchase, funds provided by Georgann Byrd Tompkins.<br />

NYSM H-2007.48.2<br />

Cover Inset: The more than 400 photographs<br />

included in A Great Day for Elmira were selected<br />

from negatives in the collections of the <strong>New</strong> <strong>York</strong><br />

<strong>State</strong> Archives.<br />

www.nysm.nysed.gov<br />

departments<br />

2<br />

3<br />

9<br />

Director’s Note<br />

<strong>Museum</strong> <strong>New</strong>s<br />

Discovery Now<br />

Update on the Schuyler Flatts Burial Ground<br />

Additional studies provide information<br />

about the individuals buried at the unmarked<br />

18th-century African cemetery.<br />

By Lisa Anderson<br />

10<br />

Hidden Treasures<br />

Micro Minerals<br />

See crystal-clear views of the tiniest<br />

minerals in the <strong>Museum</strong>’s collections.<br />

By Dr. Marian Lupulescu<br />

20<br />

A stained glass window with the coat of arms of<br />

Jan Baptiste van Rensselaer, the second son of<br />

Killiean van Rensselaer and the third patroon of<br />

Rensselaerswyck. The 17th-century window<br />

(NYSM H-1937.4.2) was in the van Rensselaer<br />

manor house and will be on display in the 1609<br />

exhibition.<br />

<strong>New</strong> <strong>York</strong> Stories<br />

Berenice Abbott’s “Changing <strong>New</strong> <strong>York</strong>”<br />

In the 1920s, new construction changed<br />

the face of <strong>New</strong> <strong>York</strong> City. Photographer<br />

Berenice Abbott captured a city in transition.<br />

By Craig Williams<br />

Facial reconstructions of individuals<br />

buried at an unmarked 19th-century<br />

cemetery help bring to life the<br />

enslaved in colonial Albany.<br />

Below: Small, rounded, dark emerald<br />

green crystals of chromdravite<br />

from the Gouverneur # 1 Talc Mine,<br />

St. Lawrence County. The central<br />

crystal of chromdravite is 0.07 mm<br />

in diameter. NYSM 22112<br />

Below: Fulton Street Dock<br />

(November 26, 1935). From the East<br />

River pier, Berenice Abbott’s view is<br />

facing the historic fish market, now<br />

the South Street Seaport.<br />

(NYSM H-1940.7.27)

John Whipple<br />

The Magazine of the<br />

<strong>New</strong> <strong>York</strong> <strong>State</strong> <strong>Museum</strong><br />

director’s note<br />

The economic downturn has placed a great deal of stress on<br />

museums and historical societies in <strong>New</strong> <strong>York</strong> state. Many<br />

have seen endowments dwindle while gifts and sponsorships<br />

have become more difficult to secure. The <strong>State</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> has<br />

not been immune to financial difficulties—periodic spending and hiring<br />

restrictions have been part of our operational landscape for many years.<br />

It’s in the difficult times when the enthusiasm and creativity of our staff<br />

spark a true appreciation for the privilege and responsibility of being<br />

director of the <strong>State</strong> <strong>Museum</strong>. A few examples from the first half of the year:<br />

n We’ve had to cancel cleaning contracts with outside vendors. In<br />

response, staff organized a “strike team,” made a plan, and set<br />

out to clean the galleries. Their pride in presenting the most<br />

welcoming experience for our visitors while protecting the<br />

objects on exhibit drove them to step up and voluntarily work<br />

beyond expectations.<br />

n Federal stimulus funds have been awarded to realize our vision<br />

of the Day Peckinpaugh, the <strong>Museum</strong>’s 1921 motor ship, as a<br />

traveling museum and educational presence on the state’s<br />

waterways. This support is wonderful recognition of the value<br />

of the <strong>Museum</strong>’s collections and the importance of our<br />

educational mission.<br />

n<br />

Staff, working with outside exhibit planners and designers,<br />

completed the design phases for our new natural history gallery<br />

and new history gallery. These galleries will transform the visitor<br />

experience, and our commitment to these projects continues<br />

despite the sometimes daunting economic challenges.<br />

Visitors often ask how I cope with such financial difficulties and<br />

uncertainties. I tell them I take pride in the <strong>Museum</strong>’s legacy—and<br />

in our stewardship of more than 12 million artifacts and specimens<br />

representing <strong>New</strong> <strong>York</strong>’s past—knowing we continue to inspire our<br />

visitors with the discoveries they make. Most of all, I take pride in and<br />

appreciate the steadfast dedication of our staff. I invite you to come<br />

to the <strong>Museum</strong> and meet them!<br />

Maria C. Sparks, Managing Editor<br />

Contributors<br />

Lisa Anderson<br />

Betty J. Duggan<br />

Ryan Fitzpatrick<br />

Lucy Larner<br />

Marian Lupulescu<br />

John L. Scherer<br />

Michelle Stefanik<br />

Craig Williams<br />

Advisory Board<br />

Clifford A. Siegfried<br />

John P. Hart<br />

Mark Schaming<br />

Jeanine L. Grinage<br />

Robert A. Daniels<br />

Penelope B. Drooker<br />

Editorial Board<br />

Carrie Bernardi<br />

Penelope B. Drooker<br />

Cecile Kowalski<br />

Geoffrey N. Stein<br />

Chuck Ver Straeten<br />

Legacy is published quarterly by the<br />

<strong>New</strong> <strong>York</strong> <strong>State</strong> <strong>Museum</strong>, Cultural<br />

Education Center, Albany, NY 12230.<br />

Members can receive the magazine<br />

via e-mail. For information about<br />

membership, call 518-474-1354<br />

or send an e-mail to:<br />

membership@mail.nysed.gov.<br />

Cliff Siegfried<br />

Director, <strong>New</strong> <strong>York</strong> <strong>State</strong> <strong>Museum</strong><br />

www.nysm.nysed.gov<br />

2 n Legacy

museum news<br />

Exhibition Explores Hudson’s Voyage<br />

and Its Legacy<br />

This cannon (NYSM H-1937.4.1) was made<br />

in 1630 in Amsterdam and may have been<br />

sent to Fort Orange that same year. In 1663,<br />

at the outbreak of the Second Esopus War,<br />

Jeremias van Rensselaer demanded the<br />

return of a cannon previously lent to the<br />

<strong>Dutch</strong> West India Company, and this one<br />

may have been sent by mistake. The logo of<br />

the company is found on the cannon’s barrel.<br />

The cannon remained in the van Rensselaer<br />

family, and according to tradition, was only<br />

used to announce the birth of a male heir,<br />

until it was bequeathed to the <strong>Museum</strong> in<br />

1939 by Mrs. William B. van Rensselaer.<br />

Must-See<br />

Exhibitions<br />

1609<br />

Opens July 3<br />

Mapping the Birds<br />

of <strong>New</strong> <strong>York</strong>:<br />

The Second Atlas of<br />

Breeding Birds in<br />

<strong>New</strong> <strong>York</strong> <strong>State</strong><br />

Through August 16<br />

Berenice Abbott’s<br />

Changing <strong>New</strong> <strong>York</strong>:<br />

A Triumph of Public Art<br />

Through October 4<br />

An upcoming exhibition at the <strong>State</strong><br />

<strong>Museum</strong> investigates, presents, and<br />

celebrates 400 years since the 1609<br />

voyage of Henry Hudson.<br />

The aptly named 1609 opens July 3 and will<br />

be the featured exhibition at the <strong>Museum</strong> during<br />

its eight-month stay. The exhibition introduces<br />

visitors to information about Henry Hudson,<br />

Native People of <strong>New</strong> <strong>York</strong>, and the <strong>Dutch</strong> period<br />

in <strong>New</strong> <strong>York</strong> by dispelling some commonly held<br />

myths and showing the legacy these groups have<br />

left to residents of <strong>New</strong> <strong>York</strong> state and to the<br />

nation as a whole.<br />

The <strong>New</strong> <strong>York</strong> <strong>State</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> collaborated<br />

with the <strong>State</strong> Archives, <strong>State</strong> Library, and Office<br />

of Educational Television and Public Broadcasting<br />

on 1609, and these institutions provided additional<br />

expertise, documents, and artifacts for the<br />

exhibition. Archaeologist Dr. James Bradley, an<br />

expert on Native Americans, Russell Shorto,<br />

an authority on colonial <strong>Dutch</strong> history, and Steven<br />

Comer, a Mohican Indian living within the original<br />

territory of the Mohican people, consulted on the<br />

project. The exhibition will also feature paintings<br />

by Capital District historical artist L.F. Tantillo.<br />

1609 presents two very different 17th-century<br />

worlds: the world of Henry Hudson and the <strong>Dutch</strong><br />

and the world of the Native People of <strong>New</strong> <strong>York</strong>.<br />

The exhibition investigates the myths that Hudson<br />

deliberately set out to discover a new land and that<br />

Native People were happy to see these newcomers.<br />

It looks at the interaction of these two cultures<br />

living in <strong>New</strong> Netherland and addresses the fallacy<br />

that Europeans took advantage of Native People<br />

and destroyed their culture. The exhibition gives<br />

visitors a view of the trade-oriented existence of<br />

<strong>New</strong> Netherland’s residents, both European and<br />

Native, and show how Native People adapted to<br />

these new people and materials in their world.<br />

The exhibition concludes with an educational<br />

and fun view of all things <strong>New</strong> <strong>York</strong> left to us by<br />

the <strong>Dutch</strong> and Native Peoples of four centuries past.<br />

Visitors can explore and discover the origins in <strong>New</strong><br />

<strong>York</strong> of contemporary cultural mainstays, such as<br />

street plans, community names, holiday celebrations,<br />

cultural diversity, and religious and cultural tolerance.<br />

In addition, the exhibition takes a look at two harsh<br />

realities of this cultural interaction: the introduction<br />

of European-style slavery and the displacement of<br />

<strong>New</strong> <strong>York</strong>’s Native People from their homelands. The<br />

exhibition will be on view through March 7, 2010. n<br />

– Michelle Stefanik, Exhibition Planner<br />

Upcoming<br />

Exhibitions<br />

Through the Eyes<br />

of Others<br />

African Americans and<br />

Identity in American Art<br />

Opens September 8<br />

This Great Nation<br />

Will Endure<br />

Opens October 2009<br />

For more details on<br />

the exhibitions, go to<br />

www.nysm.nysed.gov.<br />

Summer 2009 n 3

museum<br />

news<br />

Recent Acquisitions on Display<br />

Detail of a decorated family record<br />

produced in 1799 for the Garlogh<br />

family who lived in Montgomery<br />

County. NYSM H-2008.17.1<br />

In April, the “Collections in<br />

the <strong>New</strong> <strong>York</strong> <strong>State</strong> <strong>Museum</strong>”<br />

display case in Adirondack Hall<br />

was updated with some recent<br />

acquisitions. Now on view are:<br />

n An intricate Globe Basket made<br />

collaboratively by three generations<br />

of an Akwesasne Mohawk<br />

family, the Benedicts. The <strong>State</strong><br />

<strong>Museum</strong> commissioned the<br />

basket, which represents a striped<br />

gourd and brings to mind stories<br />

of the life-sustaining Three Sisters<br />

(corn, beans, and squash-gourd),<br />

for the Governor’s Collection of<br />

Contemporary Native American<br />

Art. (See page 12 for more on<br />

this acquisition.)<br />

n Eight mineral specimens from<br />

an important early collection of<br />

<strong>New</strong> <strong>York</strong> minerals acquired<br />

from the Philadelphia Academy<br />

of Sciences. The minerals on<br />

display are from Niagara, Orange,<br />

St. Lawrence, Ulster, Warren, and<br />

Westchester counties, including<br />

many localities long ago depleted<br />

or built over.<br />

n Bats and birds that crashed<br />

into wind turbines while migrating<br />

to and from breeding sites. To<br />

help understand the impact of<br />

wind power on wildlife, <strong>Museum</strong><br />

scientists are identifying the<br />

species and preserving them<br />

as research specimens.<br />

n A decorated family record<br />

produced in 1799 for a Mohawk<br />

Valley family. The artist, William<br />

Murray, worked in the style<br />

of early European decorated<br />

or “illuminated” manuscripts<br />

to appeal to the German<br />

immigrants of this region. The<br />

document on display is one of<br />

only about two dozen known<br />

examples of this type from the<br />

Mohawk Valley.<br />

As part of the exhibition,<br />

visitors can see additional digital<br />

materials related to the artifacts<br />

and a video of <strong>Museum</strong> biologists<br />

providing a “behind the scenes”<br />

window into their collections.<br />

The collections case was<br />

installed in 2006 to display<br />

highlights from and new<br />

additions to the <strong>Museum</strong>’s<br />

collections. The comprehensive<br />

collection includes more than<br />

12 million artifacts and specimens<br />

in the areas of biology,<br />

geology, and human history.<br />

It is the single most significant<br />

record of <strong>New</strong> <strong>York</strong>’s natural<br />

and cultural heritage. n<br />

On the Bookshelf<br />

The photographs included in A<br />

Great Day for Elmira were selected<br />

from thousands of Department of<br />

Public Works negatives documenting<br />

railroad projects. The negatives are<br />

in the collections of the <strong>New</strong> <strong>York</strong><br />

<strong>State</strong> Archives.<br />

The <strong>State</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> and<br />

the Chemung County<br />

Historical Society in Elmira<br />

recently published A Great Day<br />

for Elmira: An Illustrated History<br />

of Twentieth-Century Grade<br />

Crossing Elimination Projects in<br />

Elmira and Elsewhere in <strong>New</strong><br />

<strong>York</strong>, <strong>New</strong> <strong>York</strong> <strong>State</strong> <strong>Museum</strong><br />

Memoir No. 28, by Senior<br />

Historian Geoffrey N. Stein.<br />

The 426-page book contains<br />

hundreds of historical photographs<br />

that show how communities and<br />

landscapes changed when<br />

railroad tracks were separated<br />

from roadways. Three railroads<br />

operated in Elmira, but in the<br />

1920s, as more people began<br />

driving cars, the tracks became<br />

impediments to drivers as well<br />

as a safety concern, says Stein.<br />

Trains, previously essential to<br />

communities, would begin to<br />

fade from public view. “The<br />

significance of railroads now<br />

is lost for most people,” adds<br />

Stein, who curates the <strong>Museum</strong>’s<br />

transportation collections.<br />

The photographs included<br />

in the book were taken in the<br />

1930s, 1940s, and 1950s by<br />

photographers working for the<br />

<strong>New</strong> <strong>York</strong> <strong>State</strong> Department of<br />

Public Works. They document<br />

track projects, from the onset<br />

through completion, showing<br />

how the work transformed<br />

places where railroad tracks<br />

and streets had intersected.<br />

“Elmira is an example of what<br />

was happening all over the state,<br />

especially in the 1930s,” says Stein.<br />

The <strong>Museum</strong> also recently<br />

produced Interpretation of<br />

Topographic Maps, <strong>New</strong> <strong>York</strong><br />

<strong>State</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> Leaflet No. 36,<br />

by John B. Skiba. The leaflet<br />

provides an overview of topographic<br />

maps, how to read<br />

them, and their use. n<br />

4 n Legacy

volunteers in action<br />

Jerry Haller Makes Plant Specimens<br />

Available for Study<br />

museum<br />

news<br />

At any given time of the<br />

day, any day of the work<br />

week, volunteer Jerry<br />

Haller can be found mounting and<br />

filing specimens in the vascular<br />

plant herbarium. Haller, who<br />

retired in June 2008 after a career<br />

as a pediatric neurologist, is said<br />

to be a full-time volunteer. His<br />

involvement came at a fortuitous<br />

time for the <strong>Museum</strong> because<br />

in January 2009, the number<br />

of specimens in the herbarium<br />

topped the significant milestone<br />

of 200,000.<br />

“That’s remarkable for a state<br />

museum,” says Dr. Charles J. Sheviak,<br />

curator of botany at the <strong>New</strong> <strong>York</strong><br />

<strong>State</strong> <strong>Museum</strong>. The vascular plant<br />

herbarium documents the flora of<br />

the state, including flowering<br />

plants, ferns, trees, grass, and<br />

more. It records what was growing<br />

in an area at a certain time. The<br />

collection represents all portions<br />

of the state and also includes<br />

specimens from throughout the<br />

United <strong>State</strong>s and Canada that<br />

are used to compare trends in<br />

variation. All told, the herbarium<br />

provides great historical depth,<br />

stretching back to the earliest<br />

part of the 19th century, says<br />

Dr. Sheviak. It contains approximately<br />

400 type specimens that<br />

serve as the standard references<br />

for the identification of species.<br />

Dr. Sheviak recalls that when<br />

he came to the <strong>Museum</strong> in 1978,<br />

he inherited about 55,000 unprocessed<br />

specimens. Then, 23,000<br />

additional specimens were brought<br />

in from other state institutions<br />

and collections during one year<br />

in the early 1980s. Although the<br />

number of specimens grew, there<br />

has not always been staff or time<br />

to identify and label each specimen<br />

for the collection. Processing<br />

specimens would be just one<br />

responsibility of a collections<br />

manager, for example. “Needless<br />

to say, there are still 10’s of<br />

thousands of specimens remaining<br />

from the original backlog,<br />

and other material comes in regularly,”<br />

says Dr. Sheviak. “Jerry,<br />

by working full-time on this, has<br />

been processing specimens at a<br />

much higher rate than staff with<br />

additional responsibilities.”<br />

Haller reached his own milestone<br />

by the end of April—he<br />

has mounted more than 3,000<br />

specimens since starting at the<br />

<strong>Museum</strong> in August 2008.<br />

Haller has had a longtime<br />

interest in orchids and other<br />

plants, and while in high school,<br />

he thought about becoming a<br />

field botanist. While his career<br />

aspirations led in another direction,<br />

his avocation returned to<br />

botany. As a volunteer, he has<br />

become increasingly familiar with<br />

vascular plants and was able to<br />

organize the recent addition of<br />

400 specimens from the <strong>State</strong><br />

University of <strong>New</strong> <strong>York</strong> at<br />

Oneonta’s herbarium. He has<br />

also brought in specimens for<br />

the herbarium.<br />

If the specimen has an identification<br />

label, he mounts the<br />

specimen and the label on cotton<br />

acid-free paper. Once mounted,<br />

the specimen officially goes into<br />

the collection and can be used<br />

by scientists and others for the<br />

purposes of research and reference.<br />

“There’s a goal to clear up as<br />

much [of the backlog] as possible,”<br />

Haller says, then turns away<br />

to work on another specimen. n<br />

Jerry Haller focuses on mounting and filing specimens in the Asteraceae family. As a result<br />

of his work, more than 3,000 additional vascular plant specimens are available for study.<br />

The <strong>New</strong> <strong>York</strong><br />

<strong>State</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> offers<br />

many interesting<br />

and educational<br />

opportunities for<br />

volunteers, interns,<br />

and those interested<br />

in community<br />

service placements.<br />

For more information,<br />

call 518-402-5869.<br />

Summer 2006 2009 n 5

museum<br />

news<br />

Memory Keepers<br />

John Pasquini (right) and Ralph<br />

Rataul (center) interview Senior<br />

Historian John Scherer about his<br />

experiences at the <strong>State</strong> <strong>Museum</strong>.<br />

The two anthropologists initiated<br />

an oral history project to record<br />

the unwritten history of the people<br />

“who’ve worked at and shaped”<br />

the <strong>Museum</strong>.<br />

When Senior Historian<br />

John Scherer retired in<br />

April, he took with him<br />

nearly 42 years of firsthand knowledge<br />

of the decorative arts, popular<br />

entertainment, and print collections<br />

as well as information about the<br />

<strong>Museum</strong>’s history and day-to-day<br />

activities. While it’s impossible<br />

to capture all of a person’s institutional<br />

knowledge, an ongoing<br />

oral history project aims to record<br />

the experiences of longtime staff<br />

members to compile a history of<br />

the <strong>State</strong> <strong>Museum</strong>.<br />

<strong>Museum</strong> anthropologists<br />

John Pasquini and Ralph Rataul<br />

conceived the research project in<br />

April 2006. The 2002 death of<br />

Dr. Robert Funk, who served as<br />

<strong>State</strong> Archaeologist from 1973<br />

to 1993, had left a void in their<br />

professional lives. They both considered<br />

Funk “a great resource and<br />

friend” and knew he had “a wealth<br />

of tales” about his time working<br />

at the <strong>Museum</strong> and could provide<br />

the answers to questions about<br />

decisions made during his tenure.<br />

As a result of this loss, Pasquini<br />

and Rataul identified a need to<br />

capture and preserve the first-person<br />

accounts, stories shared among<br />

colleagues, and personal remem-<br />

brances that shape an individual’s<br />

institutional memory.<br />

“Some of this information can<br />

and does live on in the written and<br />

oral traditions that surround us<br />

everyday as friends and co-workers<br />

reminisce about the individuals in<br />

question, but that information is<br />

secondhand and is often altered<br />

through these recollections and<br />

time,” says Pasquini, a director of<br />

the archaeology lab in the Cultural<br />

Resources Survey Program. “The<br />

Oral History Project collects these<br />

memories firsthand and records<br />

them for future generations.”<br />

Pasquini and Rataul, a research<br />

and collections technician for<br />

anthropology, have interviewed<br />

more than a dozen longtime<br />

employees and former staff members.<br />

During the recorded interviews,<br />

topics range from the<br />

general background of the staff<br />

members and how they came to<br />

work at the <strong>Museum</strong> to details<br />

about how they did their job, who<br />

they reported to, what accomplishments<br />

they are most proud<br />

of, and how the <strong>Museum</strong> operated.<br />

Oral histories have the advantage<br />

of being from the “insider’s perspective,”<br />

says Rataul, who points<br />

out that neither he nor Pasquini<br />

or the majority of the current<br />

staff were <strong>Museum</strong> employees<br />

at the time many of the recalled<br />

events took place.<br />

“These insider perspectives,<br />

covering the last half century,<br />

provide a very real conception<br />

of coping and thriving during<br />

periods of massive facility and<br />

management change,” says<br />

Rataul. “Potential blueprints for<br />

how we, the current staff, might<br />

promote and manage pending<br />

changes within our time at this<br />

institution can be found in these<br />

interviews… .”<br />

A key area of interest is past<br />

relocations of the collections, and<br />

many of the <strong>Museum</strong>’s senior staff<br />

participated in the last major move<br />

[from the <strong>State</strong> Education Building].<br />

“We suspect the lessons learned<br />

during that effort would be<br />

applicable to any future relocations<br />

of the Research and<br />

Collections department,” say<br />

Pasquini and Rataul.<br />

The oral history initiative is<br />

one of several internally funded<br />

Research and Collections projects.<br />

Pasquini and Rataul were granted<br />

a percentage of time from their<br />

regular positions to work on this<br />

additional project. n<br />

6 n Legacy

Discovery Squad<br />

Student Receives<br />

Prestigious Scholarship<br />

Ocasio Willson joined the<br />

Discovery Squad as a<br />

9th grader looking for<br />

a job; this June he “graduated’<br />

from the after-school program<br />

looking ahead to Vassar College<br />

and beyond. And the <strong>Museum</strong><br />

community couldn’t be more<br />

proud of him—In April, Willson<br />

received a 2009 Gates Millenium<br />

Scholarship, a prestigious award<br />

that will cover the cost of his<br />

undergraduate education.<br />

The Albany High School graduate<br />

was one of 1,000 high school<br />

seniors from throughout the<br />

country, and 37 in <strong>New</strong> <strong>York</strong><br />

state, selected for this scholarship.<br />

The scholarship provides educational<br />

support by covering the<br />

costs that remain after a college<br />

or university provides its financial<br />

aid package. The scholarship,<br />

initially funded by a $1 billion<br />

grant from the Bill and Melinda<br />

Gates Foundation, is renewable<br />

each year. It will also provide<br />

funding for graduate school and<br />

doctoral programs, if the recipient<br />

pursues education in computer<br />

science, education, engineering,<br />

library science, mathematics,<br />

public health, or science.<br />

As a member of the Discovery<br />

Squad, Willson received academic<br />

and personal support, career<br />

guidance, and assistance with<br />

college preparation and applications.<br />

He mentored the young<br />

students in the <strong>Museum</strong> Club<br />

after-school program, helping<br />

them with homework and facilitating<br />

educational programs. He<br />

also worked as a junior counselor<br />

for Time Tunnel summer camp<br />

and as a staff host for birthday<br />

parties. This is all in addition to<br />

his involvement in about a dozen<br />

community and school organizations.<br />

“I’m the type of person<br />

who goes for any opportunity<br />

open to me,” says Willson.<br />

Stephanie Miller, the director<br />

of the after-school programs at<br />

the <strong>Museum</strong>, describes Willson as<br />

“the epitome of a role model” with<br />

his selection as a Gates Millenium<br />

Scholar. “I don’t know if I have<br />

Discovery Squad member Ocasio<br />

Willson, a Gates Millenium Scholar,<br />

helps <strong>Museum</strong> Club students with<br />

their homework.<br />

ever met a young person so<br />

focused and driven to achieve<br />

his goals …,” says Miller. “We<br />

are very proud of this young<br />

man’s many accomplishments<br />

and know that his strength of<br />

character and dedication to<br />

hard work and excellence will<br />

take him a long way.” n<br />

<strong>Dutch</strong> Apple-<strong>New</strong> <strong>York</strong> <strong>State</strong> <strong>Museum</strong><br />

Hudson Heritage Cruise<br />

The <strong>State</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> and <strong>Dutch</strong> Apple<br />

Cruises offer a Hudson Heritage Cruise to<br />

celebrate the quadricentennial of Henry<br />

Hudson’s exploration.<br />

To complement the new<br />

exhibition 1609, the<br />

<strong>Museum</strong> has teamed with<br />

<strong>Dutch</strong> Apple Cruises to offer<br />

a two-hour, narrated cruise on<br />

Albany’s popular <strong>Dutch</strong> Apple.<br />

And thanks to the generosity<br />

of <strong>Dutch</strong> Apple Cruises, the<br />

<strong>Museum</strong>’s educational programs<br />

will benefit from a donation<br />

from ticket revenue at the end<br />

of the cruise season.<br />

The Hudson Heritage Cruise<br />

is available on selected dates<br />

though October 31, at a special<br />

cost of $16.09 per person.<br />

During the two-hour cruise, the<br />

boat passes historic and contemporary<br />

landmarks.<br />

Guide “Henrietta Hudson”<br />

holds forth, covering these important<br />

sites along the shoreline. This<br />

mysterious, long lost “relative” of<br />

Henry Hudson shares her vast<br />

knowledge of the history of<br />

the <strong>Dutch</strong> in Albany and their<br />

interactions with Native People,<br />

sprinkled with a touch of humor<br />

and personal anecdotes from<br />

her many travels on the river.<br />

The cruise departs from the<br />

Steamboat Square dock in<br />

downtown Albany at 11 a.m.<br />

and returns at 1 p.m. Boarding<br />

begins at 10:30 a.m. For more<br />

information on cruise dates,<br />

please visit www.dutchapplecruises.com;<br />

for reservations,<br />

please call 518-463-0220. n<br />

– Lucy Larner, Executive<br />

Director, <strong>New</strong> <strong>York</strong> <strong>State</strong><br />

<strong>Museum</strong> Institute<br />

Summer 2009 n 7

museum<br />

news<br />

a look back<br />

The Big Move: <strong>Museum</strong> Collections<br />

Relocated from the Education Building<br />

The largest of the <strong>Museum</strong>’s<br />

three dugout canoes in the<br />

anthropology collections<br />

(NYSM CN A-37517) was<br />

hoisted out of the Education<br />

Building in 1980 (shown at<br />

right) and now resides in the<br />

<strong>Museum</strong>’s off-site collections<br />

facility. This canoe was<br />

reported found along the banks<br />

of the Susquehanna River near<br />

Binghamton and gifted to the<br />

<strong>Museum</strong> in 1922.<br />

All three dugout canoes are<br />

undergoing dendrochronology<br />

dating analysis to determine<br />

their exact ages. Recovered in<br />

1893 from Glass Lake, Rensselaer<br />

County, the <strong>Museum</strong>’s second<br />

largest dugout canoe<br />

(CN A-37516) measures 20 feet<br />

in length and will be on view<br />

in the 1609 exhibition.<br />

In 1976, when the <strong>Museum</strong><br />

opened in the new Cultural<br />

Education Center, the research<br />

collections remained a few<br />

blocks away in the Education<br />

Building on Washington Avenue.<br />

By 1979, however, an effort to<br />

remove the thousands of artifacts<br />

and specimens (as well as<br />

a few intact exhibitions) housed<br />

there was underway.<br />

Like any move, it was not<br />

without challenges. At more<br />

than 27 feet in length, a large<br />

dugout canoe that had been<br />

displayed on top of cases in<br />

Morgan Hall was too long to<br />

fit inside the building’s freight<br />

elevator. The solution was<br />

to place the canoe in a crate<br />

that would be lifted through<br />

one of the upper windows in<br />

Biology Hall, according to John<br />

Krumdieck, who as a new hire<br />

at the <strong>Museum</strong> in October 1978<br />

was charged with coordinating<br />

the move of the collections.<br />

Special scaffolding was<br />

constructed to hold the crated<br />

canoe at the height needed<br />

for it to slide out the window,<br />

which overlooked Elk Street.<br />

Early on a Saturday morning<br />

in August 1980, two cranes<br />

were positioned outside for the<br />

delicate operation of removing<br />

the canoe. “Two slings were<br />

attached to the crate as it slid out<br />

the window,” Krumdieck recalls.<br />

“As the crate emerged out of<br />

the window, the first sling was<br />

attached to the first crane, which<br />

supported one end of the crate<br />

until it had moved far enough<br />

out of the window for the<br />

second crane to be attached to<br />

fully support the crate. The two<br />

cranes then lowered the canoe<br />

evenly onto a flatbed truck.”<br />

The canoe was temporarily<br />

housed in what is now South Hall,<br />

with some of the history collections,<br />

remembers Krumdieck. The biology,<br />

anthropology, geology, and<br />

paleontology collections were<br />

also moved from the Education<br />

Building to the Cultural Education<br />

Center. Prior to this move, the<br />

bulk of the history collections<br />

had been moved from other<br />

locations and consolidated<br />

at the <strong>Museum</strong>’s off-site<br />

storage facility. n<br />

8 n Legacy

Update on the Schuyler Flatts<br />

Burial Ground<br />

discovery now<br />

By Lisa anderson<br />

Gay Malin, a facial reconstruction artist at the<br />

<strong>Museum</strong>, created this initial reconstruction<br />

of Burial 3, one of the individuals buried<br />

at the unmarked 18th-century cemetery on<br />

property owned by the Schuyler family.<br />

When an unmarked 18th-century African cemetery was<br />

accidentally discovered during construction in Colonie in<br />

2005, it was an unprecedented opportunity to learn about<br />

the lives of people who otherwise would be little known. Although<br />

there was no record of the burial ground, historical research suggested<br />

it probably was used by African individuals enslaved by the prominent<br />

Schuyler family. Studies of the skeletal remains of 14 individuals (eight<br />

adults and six children) gave a glimpse into their lives, showing that<br />

they worked hard and suffered from arthritis and poor dental health.<br />

Additional studies, including DNA analysis, were recently conducted<br />

to learn about their origins and histories. In particular, tests were conducted<br />

to confirm their African ancestry and identify the regions where<br />

they, or their ancestors, originated. Accounts in Ann Grant’s Memoirs of<br />

an American Lady describe two extended African families enslaved in the<br />

household of Margaret Schuyler, who lived at the Flatts from about 1723<br />

to 1771. Because of this, tests also were conducted to determine if any of<br />

the people from the burial ground were related.<br />

DNA testing revealed some<br />

unexpected results. Looking at<br />

mitochondrial DNA, a type of<br />

DNA inherited from our mothers<br />

that is more abundant and easier<br />

to identify in ancient bone, Esther<br />

Lee at the Andrew Merriwether<br />

Lab at Binghamton University<br />

determined that none of the<br />

adults tested were related to<br />

each other through their mother’s<br />

line. She did find, however, that<br />

three of the Schuyler Flatts people<br />

had maternal ancestry that could<br />

be traced to Africa. One of them<br />

had DNA commonly found in west<br />

and west central Africa while two<br />

others traced their maternal lineages<br />

to east Africa. The results<br />

mean that those individuals or their<br />

mothers, grandmothers, or even<br />

great-grandmothers were from<br />

Africa. Their paternal ancestry, or<br />

father’s heritage, remains unknown.<br />

The DNA for two other individuals<br />

was initially difficult to<br />

identify but was eventually traced<br />

to Madagascar, an island off the<br />

southeast coast of Africa. In the<br />

late 18th and 19th centuries,<br />

Madagascar was home to a<br />

lucrative and illegal slave trade,<br />

where pirates sold Malagasy men<br />

and women in exchange for rum<br />

and other merchandise. Members<br />

of at least one wealthy <strong>New</strong> <strong>York</strong><br />

family, Frederick Philipse and his<br />

son Adolph, were slave traders<br />

who profited from the illicit trade<br />

off Madagascar. They were also<br />

associates of the Schuylers, who<br />

may have purchased slaves directly<br />

from Philipse’s Madagascar<br />

slave ships.<br />

Another individual, a woman<br />

known only as Burial 3, had DNA<br />

that was different from the other<br />

people buried at Schuyler Flatts.<br />

Her maternal ancestry was identified<br />

as Native American. Even<br />

more interesting, the closest<br />

match for her DNA is not with<br />

Native American groups in <strong>New</strong><br />

<strong>York</strong> but with the Micmac, a<br />

tribe from the Gulf of St. Lawrence<br />

around Nova Scotia and <strong>New</strong><br />

Brunswick in eastern Canada.<br />

While additional DNA analyses<br />

are being conducted to confirm<br />

the identity by comparing DNA<br />

from members of the Aroostook<br />

Band of Micmacs living today in<br />

Maine, historical evidence may<br />

explain the connection. Heavily<br />

involved in the fur trade, the<br />

Schuylers seized upon opportunities<br />

to trade with Native groups<br />

in Canada despite laws on both<br />

sides of the border prohibiting<br />

such trade. They may have profited<br />

from trade in areas as far away<br />

as Micmac territory, apparently<br />

returning with more than furs.<br />

Each new piece of information<br />

sheds more light on the story of<br />

the Schuyler Flatts people and<br />

the complex history of enslavement<br />

and diversity in colonial<br />

Albany. Once the tests are<br />

concluded, plans will be made<br />

for reburial of the Schuyler Flatts<br />

people. Their story will be told<br />

as part of the planned Empire<br />

<strong>State</strong> gallery. n<br />

Lisa Anderson is the<br />

curator of human<br />

osteology at the <strong>New</strong><br />

<strong>York</strong> <strong>State</strong> <strong>Museum</strong><br />

and coordinator for the<br />

<strong>Museum</strong>’s compliance<br />

with the Native American<br />

Graves Protection and<br />

Repatriation Act.<br />

Summer 2009 n 9

hidden treasures<br />

MicroMinerals<br />

By Dr. Marian Lupulescu<br />

Beautiful yellow calcite “flower,”<br />

CaCO 3<br />

, on dolomite matrix,<br />

Middleville, Herkimer County.<br />

The calcite cluster is<br />

5 mm across. NYSM 22263<br />

By Dr. Marian Lupulescu<br />

The minerals in some specimen samples are too tiny to<br />

be seen by the naked eye, but mineralogists can study<br />

their form, color, and relationship with other components<br />

by using digital imaging software. The software used by <strong>Museum</strong><br />

scientists extends the capabilities of the optical microscope,<br />

such as the depth of field, and produces perfect image stitching<br />

from samples with considerable depth of field. For the images<br />

shown here, the scientist used the optical microscope to take<br />

a number of images from different levels between the base<br />

and the top of the mineral. Then, the software assembled<br />

all the images and rebuilt the crystal in high-resolution 3-D<br />

digital photography. n<br />

Dr. Marian Lupulescu is<br />

curator of minerals at the<br />

<strong>New</strong> <strong>York</strong> <strong>State</strong> <strong>Museum</strong>.<br />

His research interests in<br />

mineralogy include mineral<br />

classification and new<br />

mineral species as well as<br />

how minerals form and<br />

change their composition<br />

and structure with the<br />

environment.<br />

“The Tower of Pisa.”Cluster of shinny<br />

golden crystals of marcasite, FeS 2<br />

, with<br />

white melanterite, FeSO 4<br />

.7H 2<br />

O, from<br />

the Cicero clay pits, Onondaga County.<br />

The cluster is 3 mm in length.<br />

NYSM 22265<br />

Short prism of pale yellow olenite, NaAl 3<br />

Al 6<br />

Si 6<br />

O 18<br />

(BO 3<br />

) 3<br />

(O 3<br />

)(OH), associated with white rossmanite,<br />

[ ](Li 2<br />

Al)Al 6<br />

Si 6<br />

O 18<br />

(BO 3<br />

) 3<br />

(OH) 3<br />

(OH), from <strong>New</strong>comb, Essex County. The olenite crystal is<br />

1 mm in length. NYSM 426.21<br />

hhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhh<br />

10 n Legacy

Tiny wine-red crystal of the tourmaline-group<br />

species, manganese-rich hydroxy-uvite,<br />

CaMg 3<br />

(Al 5<br />

Mg)Si 6<br />

O 18<br />

(BO 3<br />

) 3<br />

(OH) 3<br />

(OH),<br />

from the Arnold Pit, Balmat, St. Lawrence<br />

County. The crystal is 0.5 mm in length.<br />

NYSM 15248<br />

Square crystal of wulfenite, PbMoO 4<br />

, with<br />

rounded corners from Ellenville, Ulster County.<br />

The crystal is 0.9 mm on the outer edge.<br />

NYSM 19307<br />

Small, rounded, emerald-dark-green crystals of chromdravite, NaMg 3<br />

Cr 6<br />

Si 6<br />

O 18<br />

(BO 3<br />

) 3<br />

(OH) 3<br />

(OH),<br />

associated with green tremolite and quartz, from the Gouverneur # 1 Talc Mine, St. Lawrence<br />

County. The central crystal of chromdravite is 0.07 mm in diameter. NYSM 22112<br />

Two beautiful golden sprays of goethite,<br />

FeO(OH), on quartz from the Sterling mine,<br />

Jefferson County. The sprays are 0.4 mm<br />

across. NYSM 22533<br />

Beautiful spray of pale green fibers of<br />

pecoraite, Ni 3<br />

Si 2<br />

O 5<br />

(OH) 4<br />

, in a tiny vug in<br />

quartz, from the Sterling mine, Jefferson<br />

County. The longest fiber is 3.9 mm.<br />

NYSM 22549<br />

Cluster of lamellar white crystals of gypsum, CaSO 4<br />

.2H 2<br />

O, with calcite (brown) peppered by<br />

balls of pyrite (dark). The longest gypsum crystal is 3 mm in length. NYSM 22300<br />

hhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhh<br />

Summer 2009 n 11

Three generations of an Akwesasne<br />

Mohawk basket-making family, (from<br />

left to right) Rebecca, Luz, and Florence<br />

Benedict, offer a collaboratively made<br />

Striped Gourd Basket from Florence’s<br />

Globe Basket series. Photo by Salli<br />

Benedict, 2006.<br />

Understanding a<br />

Mohawk Globe Basket<br />

in Its Makers’ World<br />

By Dr. Betty J. Duggan

In 2006, the <strong>New</strong> <strong>York</strong> <strong>State</strong><br />

<strong>Museum</strong> commissioned a<br />

basket from a Mohawk family<br />

from Akwesasne. A year later,<br />

soon after I joined the <strong>Museum</strong>,<br />

the Anthropology Department<br />

was abuzz one day with the<br />

basket’s arrival, and I was introduced<br />

to a gracefully wrought<br />

Benedict “Globe Basket,” in all<br />

the newness of its natural colors<br />

of black ash and sweetgrass, and<br />

the latter’s distinctive fragrance.<br />

Once examined, named, catalogued,<br />

measured, and technically<br />

described for entry in the<br />

<strong>Museum</strong>’s electronic database,<br />

this gem became a part of the<br />

<strong>Museum</strong>’s Ethnology Collection/<br />

Governor’s Collection of<br />

Contemporary Native American<br />

Art, to await future study and<br />

exhibitions. As an ethnographer,<br />

an anthropologist who studies<br />

contemporary cultures from<br />

cultural insiders’ and scholarly<br />

viewpoints, usually including<br />

original field research, I was<br />

eager to conduct my first fieldwork<br />

with the Benedict family.<br />

From my initial in-depth ethnographic<br />

interview with them in<br />

March 2008, through subsequent<br />

follow-up inquiries over the next<br />

year, I would explore with the<br />

Benedicts the making—contexts,<br />

meanings, and particular story—<br />

of this basket, its relation to<br />

earlier, stylistically very different<br />

Mohawk baskets, and their own<br />

lives as its makers.<br />

Meeting the Benedicts<br />

Just entering the Akwesasne<br />

Mohawk community and then<br />

reaching the home of the Ernest<br />

Benedict family, on Cornwall<br />

Island (Kawehnoke), Ontario, in<br />

the middle of the St. Lawrence<br />

River, is a lesson in Mohawk,<br />

U.S., and international history,<br />

politics, and culture. Akwesasne<br />

(“land where the partridge<br />

drums”) is the Mohawk name<br />

for the now-drowned rapids<br />

at this place in the mighty<br />

St. Lawrence when it still ran<br />

free, reverberating with a sound<br />

reminiscent of the partridge’s<br />

drumming call. It is a Mohawk<br />

community that pre-dates both<br />

the United <strong>State</strong>s and Canada,<br />

first split by those two powers<br />

in 1783 at the point where the<br />

provinces of Ontario and Quebec<br />

and St. Lawrence and Franklin<br />

counties now converge. Yet,<br />

culturally and in daily life for the<br />

Mohawk people, Akwesasne<br />

remains seemless as Native<br />

Nation and social community.<br />

The Benedict family, though its<br />

members might modestly beg to<br />

differ, saying they simply live by<br />

Mohawk ways, holds a critical<br />

place in modern Mohawk history,<br />

politics, and cultural revitalization<br />

(see page 15, For Further Reading).<br />

Florence Katsitsienhawi<br />

Benedict (trans., “she carries<br />

flowers”), born in 1931, who<br />

like the central globe in the<br />

Globe Basket, is the heart of this<br />

traditional matrilineal Mohawk<br />

family. She is a lifelong community<br />

worker, as well as a stellar<br />

and widely recognized basket<br />

maker, and granddaughter of a<br />

Wolf Clan Mother. At 78, she<br />

continues as a basketry instructor<br />

and supervises interns in the<br />

Akwesasne <strong>Museum</strong>’s crafts<br />

revitalization programs. Ernest<br />

Kaientaronkwen Benedict (“he<br />

gathers the small sticks of wood<br />

as in the ceremonial game”),<br />

born in 1918, is the eminent<br />

Mohawk intellectual, activist,<br />

early leader in Native-controlled<br />

education reform, professor,<br />

spiritual leader, and<br />

condoled Mohawk Life Chief<br />

(Rotinonkwiseres). He is founder<br />

of the North American Indian<br />

Traveling College (now Native<br />

North American Traveling<br />

College and Ronathahonni<br />

Cultural Center) and the noted<br />

Indian Country activist news<br />

journal, Akwesasne Notes.<br />

During one visit by Pope John<br />

Paul II to Canada, he was chosen<br />

to present the sacred eagle<br />

The Benedict family followed traditional Mohawk kinship and collective work patterns when<br />

they joined together to produce the Globe Basket commissioned by the <strong>State</strong> <strong>Museum</strong>. Left to<br />

right: Rebecca, Salli, Ernie, Florence, and Luz. Photo by Dr. Betty J. Duggan, 2008.<br />

Curator of Ethnography<br />

and Ethnology Dr. Betty<br />

J. Duggan joined the<br />

<strong>New</strong> <strong>York</strong> <strong>State</strong> <strong>Museum</strong><br />

in 2007. She is the first<br />

to hold this recently<br />

created position.<br />

Dr. Duggan received a<br />

Ph.D. in anthropology from<br />

the University of Tennessee<br />

and a graduate certificate<br />

in museum studies from<br />

Harvard University. Her<br />

research, and more than<br />

60 professional publications,<br />

focus on North<br />

American Indians, material<br />

culture, folklife, applied<br />

ethnography, anthropology<br />

in museums, and cultural<br />

tourism. She was Hrdy<br />

Visiting Research Curator<br />

at Harvard’s Peabody<br />

<strong>Museum</strong> of Archaeology<br />

and Ethnology during<br />

1999–2000 and a visiting<br />

professor and research<br />

associate for Wake Forest<br />

University from 2003 to<br />

2005. From 1983 to 2004,<br />

she directed and/or curated<br />

more than two dozen<br />

grant-, university-, and<br />

tribal-funded collaborativeresearch<br />

exhibitions and<br />

community projects in<br />

Tennessee, North Carolina,<br />

Mississippi, and Georgia.<br />

She is a guest editor for<br />

Practicing Anthropology<br />

in 2010.<br />

At the <strong>State</strong> <strong>Museum</strong>,<br />

she negotiated a new<br />

Native American Advisory<br />

Committee (NAAC), with<br />

formal representatives from<br />

ten Native Nations, with<br />

whom she now partners to<br />

plan and research new historic<br />

through contemporary<br />

exhibits for the renewed<br />

Native Peoples Gallery<br />

(slated for 2012).<br />

Summer 2009 n 13

“<br />

Mohawk baskets<br />

and design<br />

elements tell us<br />

stories, and must<br />

have purpose, even<br />

if only decorative;<br />

otherwise, to take<br />

the life of a tree<br />

is selfish.<br />

”<br />

Page 15: Globe Basket made by<br />

Florence, Rebecca, Luz, and Salli<br />

Benedict (basket); Kevin Lazore<br />

(ash splints). Iroquois, Mohawk.<br />

Black Ash and Sweetgrass, 34.5 cm<br />

x 32.5 cm. Ethnology Collection/<br />

Governor’s Collection of<br />

Contemporary Native American Art.<br />

NYSM E-2007.12.01A–B<br />

Below: Florence, Rebecca, and Ernie<br />

Benedict sort fresh sweetgrass<br />

before air drying and then braiding<br />

it, preparatory to basket making.<br />

Photo by Salli Benedict, 2008.<br />

feather to the Pope on behalf<br />

of all First Nations of Canada.<br />

Growing up, Florence and<br />

Ernie’s daughters and sons<br />

witnessed, participated in, and<br />

learned from their parents’<br />

important cultural work. In their<br />

own lives they consciously base<br />

their choices and actions in<br />

Mohawk values, language,<br />

teachings, and traditions, even<br />

as they engage in materially<br />

modern lives and careers.<br />

Daughters Salli Kawennotakie<br />

Benedict (“she brings a<br />

goodword”) and Rebecca<br />

Wenniseriiostha Benedict (“she<br />

makes the day nice”), both are<br />

artists and authors. Between<br />

them, the sisters work for two<br />

of the three Mohawk Councils<br />

that govern at Akwesasne:<br />

Rebecca is office manager for<br />

the St. Regis Mohawk Health<br />

Service Dental Office and Salli<br />

is a manager in the Mohawk<br />

Council of Akwesasne Aboriginal<br />

Rights and Research Office. More<br />

than two decades ago, Salli<br />

and brother, Lloyd Skaroniati<br />

Benedict (“beyond the sky”),<br />

also a former Mohawk Council<br />

of Akwesasne District chief,<br />

founded CKON Radio (“Sekon”<br />

the Mohawk greeting), which<br />

brings community news and<br />

Mohawk language, music,<br />

and arts to Akwesasne residents.<br />

Lloyd has also undertaken<br />

numerous environmental projects,<br />

including growing black ash trees<br />

and sweetgrass. Another brother,<br />

Daniel Kiorenhakwente Benedict<br />

(“light coming through the<br />

trees”), previously a media specialist<br />

at CKON and director of the<br />

Akwesasne Freedom School, now<br />

works for the St. Regis Mohawk<br />

Tribe Environment Division.<br />

Florence’s granddaughter<br />

and Salli’s oldest daughter,<br />

Luz Teiohontasen Benedict<br />

(“sweetgrass is around her”),<br />

a linguist and life coach by<br />

training, worked at a group<br />

home for Akwesasne youth and<br />

will continue a private practice<br />

in coaching young people. She<br />

and younger sisters, Jasmine<br />

Kahentineson Benedict and<br />

Kawehras Benedict-George (“it<br />

thunders”), all learned basket<br />

making at an early age from their<br />

grandmother, Florence, and assist<br />

her with new basketry projects<br />

today. Also, significant for<br />

Akwesasne basket weavers, a<br />

cousin, Les Benedict, of the St. Regis<br />

Mohawk Tribe Environment<br />

Division, co-directs a long-term,<br />

black ash restoration project aimed<br />

at revitalizing this species and<br />

area forests devastated by decades<br />

of industrial contamination and,<br />

more recently, invasive insects.<br />

Exploring the “Globe Basket<br />

Series: Striped Gourd Variant”<br />

In the comfort of Ernie and<br />

Florence’s home, a solid structure<br />

built by his grandfather, in a living<br />

room lined with commemorative<br />

honors, diplomas, family pictures<br />

and memorabilia, and, everywhere,<br />

baskets in various stages of<br />

completion, Florence, with Salli,<br />

Rebecca, and Luz, who have<br />

driven in from their homes<br />

tonight, settle in to tell me about<br />

the <strong>Museum</strong>’s new basket, and<br />

14 n Legacy

their family’s long history in<br />

basket making. Three hours go<br />

by quickly, with occasional interruptions<br />

as these and other family<br />

come and go in the course of<br />

daily routine. The interview<br />

proceeds intently, yet<br />

probingly respectful,<br />

and slowly<br />

a dialogue<br />

emerges,<br />

alternating<br />

conversations<br />

in<br />

Mohawk<br />

between<br />

Florence<br />

and Salli and<br />

English translations<br />

for the benefit<br />

of the other two, less<br />

fluent in Mohawk, and me.<br />

The women gradually chronicle<br />

for me the making and meaning<br />

of this Globe Basket. At points,<br />

their narrative is enriched with<br />

the names and basketry styles<br />

and techniques learned throughout<br />

Florence’s life, first in<br />

childhood from her grandmother,<br />

and then from other female<br />

relatives and neighbors. Other<br />

stories emerge: of economic<br />

necessity, exceedingly low prices,<br />

and changing basket forms and<br />

function geared to non-Indian<br />

tastes over more than two<br />

centuries; of periodic boat<br />

crossings of the St. Lawrence<br />

within living memory to sell<br />

stockpiled baskets to non-Indian<br />

stores. Ernie listens quietly to our<br />

conversations in the adjacent<br />

den; later he is persuaded to<br />

join us for photographs.<br />

I am instructed that Mohawk<br />

baskets and design elements<br />

tell us stories, and must have<br />

purpose, even if only decorative;<br />

otherwise, to take the life of<br />

a tree is selfish. Following the<br />

traditional rootedness and<br />

interweaving of story and spoken<br />

language within craft and<br />

production, Florence decided a<br />

few years ago to create a series<br />

of globe-shaped baskets woven<br />

from sweetgrass and black ash<br />

to represent key messages<br />

associated with Mother<br />

Earth. Each unique<br />

variant’s form,<br />

story, and<br />

name—“Hair<br />

of Mother<br />

Earth,”<br />

“Friendship,<br />

Peace and<br />

Respect,”<br />

“Striped<br />

Gourd,”<br />

“Onenhakenhra:<br />

White Corn,” “Globe<br />

Thistle,” “Onenhakenhra<br />

Spirit”—illuminates in<br />

Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) and<br />

Mohawk worldviews, essential<br />

values, relationships, and<br />

obligations human beings have<br />

in sustaining this Earth, now<br />

and into the future, to the<br />

Seventh Generation.<br />

I learn the <strong>Museum</strong>’s Globe<br />

Basket is of the “Striped Gourd<br />

variant” and in intended<br />

meanings and making demonstrates<br />

the Benedicts’ traditional<br />

collective and individual<br />

commitments to expressing,<br />

living, sharing, and passing on<br />

Mohawk culture. The viewer is<br />

visually and figurativelypresented<br />

with a striped gourd, prompting<br />

remembrance of traditional<br />

stories about three special Life<br />

Givers or Kionhekkwa (“The<br />

Three Sisters”: corn, beans, and<br />

squash-gourd-pumpkin), which<br />

in Haudenosaunee worldview<br />

and agricultural practice work<br />

in tandem to sustain life physically,<br />

emotionally, and spiritually.<br />

As Salli writes (2008a:20), for<br />

contemporary Mohawk people,<br />

the actual striped gourd is still<br />

used for multiple purposes:<br />

“… as a container for holding<br />

our food or water, or<br />

for supporting our fishing<br />

nets … [and] in making<br />

music, so that we can sing<br />

the songs that are our<br />

thanksgiving tribute to the<br />

Creator and all elements<br />

of Creation … so that<br />

the World will have the<br />

resources we need to<br />

survive. Everybody sing!”<br />

I discover that from idea to<br />

completion, this Striped Gourd<br />

basket’s creation was a traditional<br />

collaborative effort, requiring<br />

more than four months of coordinated<br />

work by five people.<br />

Salli designed it. Kevin Lazore,<br />

another Mohawk from the<br />

Sugarbush area of Akwesasne,<br />

harvested, debarked, pounded,<br />

and prepared splints from a black<br />

ash tree, as he does for many<br />

basket weavers. (In earlier<br />

generations, male family<br />

members did the arduous preliminary<br />

preparation of black<br />

ash. Ernie, now 91, still assists<br />

the Benedict women in gathering<br />

and preparing sweetgrass.)<br />

From the pounded splints,<br />

Florence then wove the large<br />

central basket, while Rebecca<br />

and Luz made the roughly<br />

27 dozen miniature baskets<br />

that stripe its curved sides.<br />

I am informed the thin gold,<br />

green, and brown strands that<br />

ring the globe’s lid and rims and<br />

completely form the miniature<br />

baskets are made of native<br />

sweetgrass (Anthoxanthum<br />

nitens), harvested from a wild<br />

patch tended by Florence and<br />

Rebecca. The sweetgrass’ colors<br />

will ripen and change over time,<br />

as the long strands of grass age<br />

after cutting; its pleasant aroma<br />

will always return, strong and<br />

fresh, when dampened with<br />

life-giving water. Later, in going<br />

For Further Reading:<br />

Writings by or About<br />

the Benedicts<br />

Benedict, Ernest. 1999. “‘I<br />

would say when you search after<br />

truth, truth is that which you will<br />

find that is dependable and is of<br />

use to you.’” In In the Words of<br />

the Elders: Aboriginal Cultures in<br />

Transition, Peter Kulchyski, Don<br />

McCaskill, and David <strong>New</strong>house,<br />

eds., p. 95–140. Toronto:<br />

University of Toronto Press.<br />

_____. 1995. “’Through these<br />

stories we learned many things.’”<br />

In Native Heritage: Personal<br />

Accounts by American Indians<br />

1790 to the Present, Arlene<br />

Hershfelder, ed., p. 111–112.<br />

MacMillan Publishing Company.<br />

_____. Editor, Akwesasne<br />

Notes, 1994–1996.<br />

Benedict, Les and Richard<br />

David. 2003. “Propagation Protocol<br />

for Black Ash (Fraxinus nigra<br />

Marsh).” Native Plants: 100–103.<br />

Benedict, Rebecca and Charis<br />

Wahl. 1976. St. Regis Reserve.<br />

Don Mills, Ontario: Fitzhenry &<br />

Whiteside.<br />

Benedict, Salli. 2008a.<br />

“Akwesasne Basket Making: An<br />

Enduring Tradition.” In North by<br />

Northeast: Wabanaki, Akwesasne<br />

Mohawk, and Tuscarora<br />

Traditional Arts, Kathleen<br />

Mundell, ed., p. 11–15. Gardiner,<br />

Maine: Tilbury House, Publishers.<br />

_____. 2008b. “The Globe<br />

Basket Series of Akwesasne<br />

Basketmaker Florence<br />

Katistsienkwi Benedict.” In<br />

North by Northeast: Wabanaki,<br />

Akwesasne Mohawk, and<br />

Tuscarora Traditional Arts,<br />

Kathleen Mundell, ed., p. 16–23.<br />

Gardiner, Maine: Tilbury House,<br />

Publishers.<br />

_____. 2007. “Made in<br />

Akwesasne.” In Archaeology of<br />

the Iroquois: Selected Readings<br />

and Research Sources, Jordan<br />

E. Kerber, ed., p. 422–441.<br />

Syracuse: Syracuse University<br />

Press. [Originally published in J.V.<br />

Wright and Jean-Luc Pilo (2004).]<br />

_____. 2000. “Tahotahontanekenseratkerontakwenkakie.”<br />

In Stories for a<br />

Winter’s Night, Maurice Kenny,<br />

ed., p. 146–148. Buffalo, NY:<br />

White Pine Press. [Also published<br />

in Jerome Beaty and Paul Hunter<br />

(1999) and Simon Ortiz (1983).]<br />

Summer 2009 n 15

For Further Reading:<br />

Writings by or About<br />

the Benedicts (continued)<br />

_____. 1999. “Mother Earth.” In<br />

The Words that Come before All<br />

Else: Environmental Philosophies<br />

of the Haudenosaunee.<br />

Haudenosaunee Environmental<br />

Task Force.<br />

_____. 1997. “The Serpent<br />

Story.” In Reinventing the<br />

Enemy’s Language: Contemporary<br />

Native Women’s Writing of North<br />

America, Joy Harjo and Gloria<br />

Bird, eds., p. 311–314. <strong>New</strong> <strong>York</strong>:<br />

W. W. Norton & Co.<br />

Hauptman, Laurence M. 2008.<br />

“Where the Partridge Drums: Ernest<br />

Benedict, Mohawk Intellectual as<br />

Activist.” In Seven Generations<br />

of Iroquois Leadership: The Six<br />

Nations Since 1800. Syracuse:<br />

Syracuse University Press.<br />

Johansen, Bruce. 2007.<br />

Grandfathers of Akwesasne<br />

Mohawk Revitalization: Ray Fadden<br />

and Ernest Benedict. In The Praeger<br />

Handbook on Contemporary<br />

Issues in Native America, p. 209–<br />

219. Praeger Publishers.<br />

over an essay by Sue Ellen Herne,<br />

Mohawk author, artist, and<br />

curator, I find another quotation<br />

by Salli (in Herne and Williamson<br />

2008:7) that connects this<br />

Striped Gourd basket’s material<br />

and symbolic essence back to<br />

the first story and name in<br />

Florence’s inspired Globe Basket<br />

series. She explains, “In<br />

Rotinonshonni [Mohawk for<br />

Haudenosaunee] culture, sweetgrass<br />

is the ‘Hair of Mother<br />

Earth.’ Its sweet fragrance is<br />

appealing and endears us to<br />

her. We know that we are not<br />

disconnected from our Mother<br />

Earth when we can smell her<br />

sweet hair.”<br />

On Making Mohawk Art<br />

and Community<br />

There is yet deeper meaning<br />

and purpose to consider in<br />

understanding the <strong>Museum</strong>’s<br />

Globe Basket. This is the role<br />

of creation and continuation<br />

of Mohawk social community,<br />

in this case, glimpsed through<br />

Mohawk basket making and its<br />

embeddedness and interconnectedness<br />

within the larger,<br />

collective cultural frames of<br />

Mohawk society.<br />

Taking us further, in speaking<br />

of distinctions between understandings<br />

of meaning and<br />

purpose of art/craft and<br />

aesthetics in Western and<br />

Native American societies, the<br />

distinguished Tuscarora and<br />

Haudenosaunee artist, museum<br />

director and curator, author,<br />

educator, and activist Richard<br />

W. Hill, Sr. (2002:10) explains:<br />

“From birth, the Native<br />

child is immersed in a<br />

circle of tradition and<br />

surrounded with objects<br />

of belief, power, and<br />

identity … The sacredness<br />

of life, the interconnectedness<br />

of community,<br />

and the preciousness of<br />

knowledge are expressed<br />

through art. Images of<br />

power, of spiritual beings,<br />

and of personal dreams<br />

and visions become the<br />

legacy of the first artists<br />

of this land … Taking<br />

the time to craft objects,<br />

to decorate them to feel<br />

connected to a community<br />

aesthetic are all part of<br />

the creative process.<br />

However, the act of creating<br />

is also an act of faith<br />

in your individual and group<br />

identity that connects you<br />

to your ancestors, as well<br />

as to future generations.<br />

Art is the linking of the<br />

past, present, and future<br />

and is thus the reason for<br />

making objects as much<br />

as it is the object itself.”<br />

To appreciate the deepest<br />

meanings of the <strong>Museum</strong>’s<br />

Globe Basket for its makers<br />

ultimately is to understand it<br />

as part of ongoing Mohawk<br />

society— to see it as one<br />

microscopic element in the<br />

making, renewal, and remaking<br />