Fourth Annual Chicago Forum on International ... - Mayer Brown

Fourth Annual Chicago Forum on International ... - Mayer Brown

Fourth Annual Chicago Forum on International ... - Mayer Brown

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

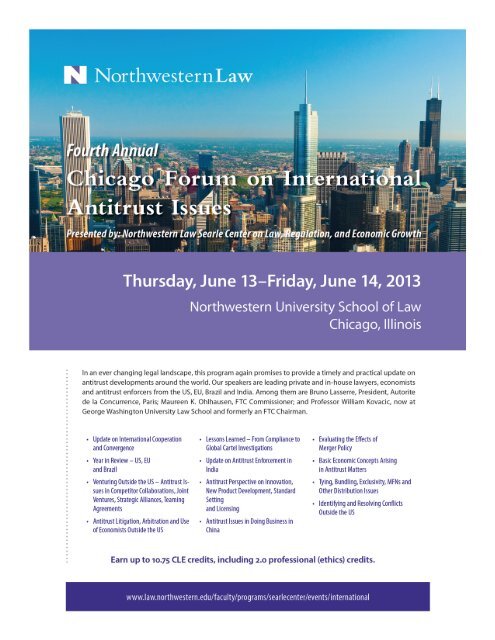

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Fourth</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Annual</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Chicago</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Forum</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> Internati<strong>on</strong>al Antitrust Issues<br />

TABLE OF CONTENTS<br />

FRONT COVER<br />

TABLE OF CONTENTS<br />

AGENDA<br />

WITH THANKS TO OUR SPONSORS<br />

PLANNING COMMITTEE<br />

SPEAKER BIOS<br />

KEYNOTE ADDRESS BY MAUREEN K. OHLHAUSEN: UPDATE ON INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AND<br />

CONVERGENCE<br />

• Memorandum of Understanding <strong>on</strong> Antitrust Cooperati<strong>on</strong> between the United States<br />

Department of Justice and the United States Federal Trade Commissi<strong>on</strong> and the Ministry<br />

of Corporate Affairs (Government of India) and the Competiti<strong>on</strong> Commissi<strong>on</strong> of India<br />

• The Never-ending yet Vital Pursuit of Greater Cooperati<strong>on</strong>, C<strong>on</strong>vergence, and<br />

Transparency—Remarks of Maureen K. Ohlhausen, Commissi<strong>on</strong>er, Federal Trade<br />

Commissi<strong>on</strong> at the First <str<strong>on</strong>g>Annual</str<strong>on</strong>g> Symposium. China Institute of Internati<strong>on</strong>al Antitrust<br />

and Investment, China University of Political Science and Law, Beijing, China (March 22,<br />

2013)<br />

• Memorandum of Understanding <strong>on</strong> Antitrust and Antim<strong>on</strong>opoly Cooperati<strong>on</strong> between<br />

the United States Department of Justice and Federal Trade Commissi<strong>on</strong>, <strong>on</strong> the One<br />

Hand, and the People’s Republic of China Nati<strong>on</strong>al Development and Reform<br />

Commissi<strong>on</strong>, Ministry of Commerce, and State Administrati<strong>on</strong> for Industry and<br />

Commerce, <strong>on</strong> the Other Hand<br />

• Taking Notes: Observati<strong>on</strong>s On the First Five Years of the Chinese Anti-M<strong>on</strong>opoly Law,<br />

Remarks of Maureen K. Ohlhausen, Commissi<strong>on</strong>er, Federal Trade Commissi<strong>on</strong> at the

Competiti<strong>on</strong> Committee Meeting, U.S. Council for Internati<strong>on</strong>al Business, Washingt<strong>on</strong>,<br />

DC (May 9, 2013).<br />

YEAR IN REVIEW—US, EU, and Brazil<br />

• “2013: What to expect <strong>on</strong> the European competiti<strong>on</strong> policy fr<strong>on</strong>t,” by Tom Jenkins and Bill<br />

Batchelor (Baker & McKenzie, European & Competiti<strong>on</strong> Law Practice, Brussels)<br />

• “FA Premier League: The Broader Implicati<strong>on</strong>s for Copyright Licensing,” by Tom Jenkins and Bill<br />

Batchelor (Baker & McKenzie, European & Competiti<strong>on</strong> Law Practice, Brussels)<br />

• “CJEU AstraZeneca Judgment: Groping Towards a Test for Patent Office Dealings,” by Bill<br />

Batchelor and Melissa Healy in European Competiti<strong>on</strong> Law Review<br />

• History of Competiti<strong>on</strong> Policy in Brazil: 1930–2010<br />

• Competiti<strong>on</strong> Policy in Brazil (Presentati<strong>on</strong>—Francisco Todorov)<br />

VENTURING OUTSIDE THE US—ANTITRUST ISSUES IN COMPETITOR COLLABORATIONS, JOINT VENTURES,<br />

STRATEGIC ALLIANCES, TEAMING AGREEMENTS<br />

• EC Guidelines <strong>on</strong> the applicability of Article 101 of the Treaty <strong>on</strong> the Functi<strong>on</strong>ing of the European<br />

Uni<strong>on</strong> to horiz<strong>on</strong>tal co-operati<strong>on</strong> agreements<br />

• EC Guidelines <strong>on</strong> Vertical Restraints<br />

• FTC/DOJ Antitrust Guidelines for Collaborati<strong>on</strong>s Am<strong>on</strong>g Competitors<br />

ANTITRUST LITIGATION, ARBITRATION AND USE OF ECONOMISTS OUTSIDE THE US<br />

• 2012 Global Guide to Competiti<strong>on</strong> Litigati<strong>on</strong>—England and Wales (Baker & McKenzie)<br />

• “Arbitrating Competiti<strong>on</strong> Law Disputes: A Matter of Policy?” by Francesca Richm<strong>on</strong>d in the<br />

Kluwer Arbitrati<strong>on</strong> Blog<br />

• Global Guide to Competiti<strong>on</strong> Litigati<strong>on</strong><br />

• Draft Guidance Paper: Quantifying Harm in Acti<strong>on</strong>s for Damages Based <strong>on</strong> Breaches of Article<br />

101 or 102 of the Treaty <strong>on</strong> the Functi<strong>on</strong>ing of the European Uni<strong>on</strong><br />

• The Use of Experts in Internati<strong>on</strong>al Litigati<strong>on</strong> (Presentati<strong>on</strong>—Kristin Terris)<br />

• Antitrust Litigati<strong>on</strong> Outside of the U.S (Presentati<strong>on</strong>—Francesca Richm<strong>on</strong>d)

LESSONS LEARNED FROM COMPLIANCE TO GLOBAL CARTEL INVESTIGATIONS (ETHICS CREDIT)<br />

• 2012 Guidelines Manual, Chapter Eight: Sentencing of Organizati<strong>on</strong>s<br />

• United States of America v. AU Optr<strong>on</strong>ics Corporati<strong>on</strong><br />

• Statement of Assistant Attorney General Bill Baer <strong>on</strong> Changes to Antitrust Divisi<strong>on</strong>’s Carve-Out<br />

Practice Regarding Corporate Plea Agreements<br />

• Sentencing Memo: United States of America v. AU Optr<strong>on</strong>ics Corporati<strong>on</strong><br />

• Guiding Principles of Enforcement<br />

• Compliance Matters: What companies can do better to respect EU competiti<strong>on</strong> rules<br />

• Framework-Document of 10 February 2012 <strong>on</strong> Antitrust Compliance Programmes<br />

• “Competiti<strong>on</strong> Law Compliance Programs and Government Support or Indifference” by Theodore<br />

Banks and Nathalie Jalabert-Doury<br />

• “Enforcers’ C<strong>on</strong>siderati<strong>on</strong> of Compliance Programs in Europe: Are 2011 Initiatives Raising Their<br />

Profile or Reducing It to the Lowest Comm<strong>on</strong> Denominator?” by Nathalie Jalabert-Doury & Gillian<br />

Sproul<br />

• Less<strong>on</strong>s Learned From Compliance to Global Cartels Translating Theory Into Practice<br />

(Presentati<strong>on</strong>—Karine Faden)<br />

UPDATE ON ANTITRUST ENFORCEMENT IN INDIA<br />

• Update <strong>on</strong> Antitrust Enforcement in India (Presentati<strong>on</strong>—Nicholas J. Franczyk)<br />

ANTITRUST PERSPECTIVE ON INNOVATION, NEW PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT, STANDARD SETTING AND LICENSING<br />

• Antitrust, Innovati<strong>on</strong>, and Standard-Setting (Presentati<strong>on</strong>—John D. Harkrider)<br />

ANTITRUST ISSUES IN DOING BUSINESS IN CHINA<br />

• Antitrust Issues in Doing Business in China (Presentati<strong>on</strong>—H. Stephen Harris, Jr.)<br />

EVALUATING THE EFFECTS OF MERGER POLICY<br />

• “Assessing the Quality of Competiti<strong>on</strong> Policy: The Case of Horiz<strong>on</strong>tal Merger Enforcement” by<br />

William E. Kovacic

BASIC ECONOMIC CONCEPTS ARISING IN ANTITRUST MATTERS<br />

• “Market Definiti<strong>on</strong> and Unilateral Competitive Effects in Online Retail Markets,” by Michael R.<br />

Baye<br />

• “Unilateral Competitive Effects of Mergers Between Firms with High Profit Margins,” by<br />

Elizabeth M. Bailey, Gregory K. Le<strong>on</strong>ard, and Lawrence Wu<br />

• “Horiz<strong>on</strong>tal Mergers of Online Firms: Structural Estimati<strong>on</strong> and Competitive Effects,” by<br />

Y<strong>on</strong>gh<strong>on</strong>g An, Michael R. Baye, Yingyao Hu and John Morgan<br />

• “Hypotheticals and Counterfactuals: the Ec<strong>on</strong>omics of Competiti<strong>on</strong> Policy,” by Mark Williams and<br />

A. Jorge Padilla<br />

• Horiz<strong>on</strong>tal Merger Guidelines<br />

TYING, BUNDLING, EXCLUSIVITY, MFNS AND OTHER DISTRIBUTION ISSUES<br />

• Tying, Bundling , Exclusive Dealing, & Loyalty Discounts: Basics of the Analysis Under US Antitrust<br />

Law (Presentati<strong>on</strong>—Mark McLaughlin)<br />

IDENTIFYING AND RESOLVING CONFLICTS OUTSIDE THE US<br />

• Identifying and Resolving C<strong>on</strong>flicts Outside the US (Presentati<strong>on</strong>—Jas<strong>on</strong> H. Staples and Charles F.<br />

Regan, Jr.)

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Fourth</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Annual</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Chicago</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Forum</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> Internati<strong>on</strong>al Antitrust Issues<br />

Thursday, June 13th<br />

Thursday, June 13-Friday, June 14, 2013<br />

Northwestern University School of Law<br />

Wieboldt Hall #147<br />

340 E. Superior Street, <str<strong>on</strong>g>Chicago</str<strong>on</strong>g>, IL 60611<br />

Morning Sessi<strong>on</strong> Chair: Roxane C. Busey, Partner, Baker & McKenzie LLP, <str<strong>on</strong>g>Chicago</str<strong>on</strong>g>, IL<br />

8:00 a.m. Registrati<strong>on</strong> and C<strong>on</strong>tinental Breakfast (WB 150)<br />

8:40-8:45 Welcome and Introducti<strong>on</strong> (WB 147)<br />

Dean Daniel B. Rodriguez, Dean and Harold Washingt<strong>on</strong> Professor, Northwestern University<br />

School of Law<br />

Max Schanzenbach, Professor of Law and Director of Searle Center <strong>on</strong> Law, Regulati<strong>on</strong>, and<br />

Ec<strong>on</strong>omic Growth at Northwestern University School of Law<br />

Matthew L. Spitzer, Incoming Director, Searle Center <strong>on</strong> Law, Regulati<strong>on</strong>, and Ec<strong>on</strong>omic<br />

Growth at Northwestern University School of Law<br />

8:45-9:15 Keynote Address: Update <strong>on</strong> Internati<strong>on</strong>al Cooperati<strong>on</strong> and C<strong>on</strong>vergence<br />

Maureen K. Ohlhausen, Commissi<strong>on</strong>er, Federal Trade Commissi<strong>on</strong><br />

9:15-10:15 Year in Review—US, EU, and Brazil<br />

Roxane C. Busey, Partner, Baker & McKenzie LLP, <str<strong>on</strong>g>Chicago</str<strong>on</strong>g>, IL (moderator)<br />

Bill Batchelor, Baker & McKenzie LLP, Brussels, Belgium<br />

Britt M. Miller, Partner, <strong>Mayer</strong> <strong>Brown</strong> LLP, <str<strong>on</strong>g>Chicago</str<strong>on</strong>g>, IL<br />

Francisco Todorov, Partner, Trench, Rossi e Watanabe Advogados, Brasilia, Brazil<br />

10:15-10:30 Networking Break (WB 150)

10:30-11:15 Venturing Outside the US—Antitrust Issues in Competitor Collaborati<strong>on</strong>s, Joint Ventures,<br />

Strategic Alliances, Teaming Agreements<br />

Nick Koberstein, Divisi<strong>on</strong> Counsel, Corporate Transacti<strong>on</strong>s, Abbott Laboratories (moderator)<br />

Jean-Yves Art, Associate General Counsel, Microsoft Corporati<strong>on</strong>, Brussels, Belgium<br />

Mildred L. Calhoun, formerly of BP America, <str<strong>on</strong>g>Chicago</str<strong>on</strong>g>, IL<br />

Anne Gr<strong>on</strong>, Vice President, NERA Ec<strong>on</strong>omic C<strong>on</strong>sulting<br />

11:15-12:15 Antitrust Litigati<strong>on</strong>, Arbitrati<strong>on</strong> and Use of Ec<strong>on</strong>omists Outside the US<br />

Robert McLeod, Editor in Chief, MLEX Market Intelligence (moderator)<br />

Patrick Ahern, Partner, Baker & McKenzie LLP, <str<strong>on</strong>g>Chicago</str<strong>on</strong>g>, IL<br />

Francesca Richm<strong>on</strong>d, Associate, Baker & McKenzie LLP, L<strong>on</strong>d<strong>on</strong>, United Kingdom<br />

Kristin Terris, Vice President, NERA Ec<strong>on</strong>omic C<strong>on</strong>sulting<br />

12:15-12:45 Lunch (WB 540)<br />

12:45-1:15 Lunch Address<br />

Bruno Lasserre, President, Autorité de la C<strong>on</strong>currence, Paris, France<br />

Afterno<strong>on</strong> Sessi<strong>on</strong> Chair: Thomas Campbell, Partner, Baker & McKenzie LLP, <str<strong>on</strong>g>Chicago</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

1:30-2:30 Less<strong>on</strong>s Learned From Compliance to Global Cartel Investigati<strong>on</strong>s (ethics credit)<br />

Thomas Campbell, Partner, Baker & McKenzie LLP, <str<strong>on</strong>g>Chicago</str<strong>on</strong>g>, IL (moderator)<br />

Karine R. Faden, Managing Counsel, Regulatory, Antitrust & Competiti<strong>on</strong>, United Airlines<br />

Neville S. Hedley, Director, Internal Investigati<strong>on</strong>s, Abbott Laboratories<br />

Nathalie Jalabert Doury, Partner, <strong>Mayer</strong> <strong>Brown</strong> Internati<strong>on</strong>al, Paris, France<br />

2:30-3:15 Update <strong>on</strong> Antitrust Enforcement in India<br />

H. Stephen Harris, Jr., Partner, Baker & McKenzie LLP, Washingt<strong>on</strong> D.C. (moderator)<br />

Nicholas R. Franczyk, Counsel for Internati<strong>on</strong>al Technical Assistance, Federal Trade<br />

Commissi<strong>on</strong><br />

Samir R. Gandhi, AZB & Partners, New Delhi, India<br />

3:15-3:30 Networking Break (WB 150)<br />

3:30-4:30 Antitrust Perspective <strong>on</strong> Innovati<strong>on</strong>, New Product Development, Standard Setting and Licensing<br />

Alice W. Detwiler, Senior Attorney, Microsoft Corporati<strong>on</strong> (moderator)<br />

John D. Harkrider, Axinn Veltrop & Harkrider LLP<br />

Roy Hoffinger, Vice President, Legal Counsel, Qualcomm Inc.<br />

Jay Jurata, Partner, Antitrust & Competiti<strong>on</strong>, Orrick, Herringt<strong>on</strong> & Sutcliffe LLP<br />

4:30-5:15 Antitrust Issues in Doing Business in China<br />

Russell W. Damtoft, Associate Director, Office of Internati<strong>on</strong>al Affairs, Federal Trade<br />

Commissi<strong>on</strong> (moderator)<br />

H. Stephen Harris, Jr., Partner, Baker & McKenzie LLP, Washingt<strong>on</strong>, DC<br />

5:15 Cocktail Recepti<strong>on</strong> (WB 540)

Friday, June 14th<br />

Morning Sessi<strong>on</strong> Chair: Chris Kelly, Partner, <strong>Mayer</strong> <strong>Brown</strong> LLP, <str<strong>on</strong>g>Chicago</str<strong>on</strong>g>, IL<br />

8:00 a.m. C<strong>on</strong>tinental Breakfast (WB 150)<br />

8:45-9:15 Evaluating the Effects of Merger Policy<br />

William E. Kovacic, Global Competiti<strong>on</strong> Professor of Law and Policy, George Washingt<strong>on</strong><br />

University Law School and former Chairman, Federal Trade Commissi<strong>on</strong><br />

9:15-10:15 Basic Ec<strong>on</strong>omic C<strong>on</strong>cepts Arising in Antitrust Matters<br />

Anne Gr<strong>on</strong>, Vice President, NERA Ec<strong>on</strong>omic C<strong>on</strong>sulting (moderator)<br />

Michael R. Baye, Bert Elwert Professor of Business Ec<strong>on</strong>omics and Public Policy, Department<br />

of Business Ec<strong>on</strong>omics, Kelley School of Business, Indiana University<br />

Thomas S. Respess, Principal Ec<strong>on</strong>omist, Baker & McKenzie LLP, Washingt<strong>on</strong>, D.C.<br />

10:15-10:30 Networking Break (WB 150)<br />

10:30-11:30 Tying, Bundling, Exclusivity, MFNs and Other Distributi<strong>on</strong> Issues<br />

Jean-Yves Art, Associate General Counsel, Microsoft Corporati<strong>on</strong>, Brussels, Belgium<br />

Paul Fr<strong>on</strong>tczak, Jr., Senior Antitrust Counsel, Shell Oil Company<br />

Nels<strong>on</strong> Jung, Director, Competiti<strong>on</strong> Enforcement, Office of Fair Trading, L<strong>on</strong>d<strong>on</strong>, United<br />

Kingdom<br />

11:30-12:30 Identifying and Resolving C<strong>on</strong>flicts Outside the US (professi<strong>on</strong>al resp<strong>on</strong>sibility(ethics) credit)<br />

Charles F. Regan, Partner, <strong>Mayer</strong> <strong>Brown</strong> LLP, <str<strong>on</strong>g>Chicago</str<strong>on</strong>g>, IL<br />

Jas<strong>on</strong> H. Staples, Senior Counsel, Internati<strong>on</strong>al Legal Operati<strong>on</strong>s, Abbott Laboratories<br />

12:30 pm Adjourn

With thanks to our sp<strong>on</strong>sors

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Fourth</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Annual</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Chicago</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Forum</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong><br />

Internati<strong>on</strong>al Antitrust Issues<br />

Planning Committee<br />

Chair<br />

Roxane C. Busey<br />

Baker & McKenzie LLP<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Chicago</str<strong>on</strong>g>, IL<br />

Members<br />

Thomas Campbell<br />

Baker & McKenzie LLP<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Chicago</str<strong>on</strong>g>, IL<br />

Russell W. Damtoft<br />

Associate Director<br />

Office of Internati<strong>on</strong>al Affairs<br />

Federal Trade Commissi<strong>on</strong><br />

Washingt<strong>on</strong>, D.C.<br />

Alice W. Detwiler<br />

Senior Attorney<br />

Microsoft Corporati<strong>on</strong><br />

Redm<strong>on</strong>d, WA<br />

Anne Gr<strong>on</strong><br />

Vice President<br />

NERA Ec<strong>on</strong>omic<br />

C<strong>on</strong>sulting<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Chicago</str<strong>on</strong>g>, IL<br />

Mark McLaughlin<br />

<strong>Mayer</strong> <strong>Brown</strong> LLP<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Chicago</str<strong>on</strong>g>, IL<br />

Nick Koberstein<br />

Divisi<strong>on</strong> Counsel,<br />

Corporate Transacti<strong>on</strong>s<br />

Abbott Laboratories<br />

Abbott Park, IL<br />

1

SPEAKER BIOS

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Fourth</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Annual</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Chicago</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Forum</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> Internati<strong>on</strong>al Antitrust Issues<br />

Participant Biographies<br />

PATRICK J. AHERN practices in the areas of antitrust and litigati<strong>on</strong>. His experience<br />

includes representing some of the world’s largest oil companies across various US<br />

courts. Am<strong>on</strong>g other publicati<strong>on</strong>s, Mr. Ahern co-authored secti<strong>on</strong>s <strong>on</strong> the Noerr-<br />

Penningt<strong>on</strong> Doctrine and Premerger Notificati<strong>on</strong> as an update <strong>on</strong> the chapter of<br />

"Antitrust C<strong>on</strong>siderati<strong>on</strong>s" of the Illinois Institute of C<strong>on</strong>tinuing Legal Educati<strong>on</strong> Health<br />

Care Handbook (1990 update). He also served as assistant editor of The Antitrust Law<br />

Journal from 1994-1996, and editorial board member of the ABA Antitrust Law<br />

Development Treatise from 1997 to 1998.<br />

Mr. Ahern focuses <strong>on</strong> antitrust litigati<strong>on</strong> and counseling, as well as commercial litigati<strong>on</strong><br />

and class acti<strong>on</strong>s. He has also led numerous presentati<strong>on</strong>s at meetings of the ABA<br />

Antitrust Secti<strong>on</strong><br />

Mr. Ahern received his BA from Georgetown University in 1981 and his JD from the<br />

University of Illinois College of Law in (1984).<br />

JEAN-YVES ART is Associate General Counsel at Microsoft. He leads a team of<br />

lawyers who counsel business executives <strong>on</strong> all antitrust aspects of Microsoft’s activities<br />

in the EMEA regi<strong>on</strong> (including merger review, interoperability and standards policy). In<br />

close coordinati<strong>on</strong> with the Company’s headquarters in Redm<strong>on</strong>d, Jean-Yves also<br />

manages the antitrust proceedings in which the Company is involved in the regi<strong>on</strong>.<br />

Before joining Microsoft in 2002, Jean-Yves had practiced European competiti<strong>on</strong> law for<br />

ten years with Coudert Brothers, a firm that he joined after having worked for three<br />

years as a legal secretary at the Court of Justice of the European Communities.<br />

Jean-Yves is also visiting professor at the College of Europe, Bruges, where he teaches<br />

EU merger c<strong>on</strong>trol, and at the University of Liège where he co-chairs a seminar <strong>on</strong><br />

advanced topics in EU antitrust law. He has written extensively and is a regular<br />

speaker at c<strong>on</strong>ferences <strong>on</strong> EU competiti<strong>on</strong> law.<br />

BILL BATCHELOR advises <strong>on</strong> merger c<strong>on</strong>trol, antitrust litigati<strong>on</strong> and regulatory<br />

investigati<strong>on</strong>s. He has worked in the Washingt<strong>on</strong> DC, L<strong>on</strong>d<strong>on</strong> and Brussels offices of<br />

Baker & McKenzie, as well as spending time at both the EU Commissi<strong>on</strong> and UK<br />

competiti<strong>on</strong> authorities. Bill's focus is <strong>on</strong> high tech IT and lifescience companies.<br />

1

Bill advises <strong>on</strong> EC and multi-jurisdicti<strong>on</strong>al merger c<strong>on</strong>trol laws in relati<strong>on</strong> to mergers and<br />

joint ventures. Recent projects include Cisco/WebEx, Cisco/Ir<strong>on</strong>port, Cisco/Navini,<br />

Cisco/Linksys/Belkin (for Cisco), ADM/Pura, ADM/Elstar, ADM/Wilmar (for ADM),<br />

Amex/Fortis/Alphacard (for Alphacard); OTPP/Camelot (for OTPP), Canal+/TVN/n (for<br />

Canal+), Biogen Idec/Elan (for Biogen).<br />

Bill regularly counsels clients <strong>on</strong> collaborati<strong>on</strong> and distributi<strong>on</strong> strategies, including copromoti<strong>on</strong>/co-branding,<br />

B2B platforms, media distributi<strong>on</strong> arrangements and go-tomarket<br />

channel programmes, including the 3G mobile, data networking, telecoms,<br />

lifescience and software sectors.<br />

Bill is acting for complainants and defendants in cartel and market power investigati<strong>on</strong>s.<br />

Recent projects include: reversing a Commissi<strong>on</strong> cartel decisi<strong>on</strong> in the Synthetic<br />

Rubber cartel; successfully securing <strong>on</strong>e of the lowest negotiated settlements in the<br />

seven year l<strong>on</strong>g DRAM investigati<strong>on</strong>; securing significant reducti<strong>on</strong>s in fine for Archer<br />

Daniels Midland in respect of the Citric Acid, Amino Acids and Sodium Gluc<strong>on</strong>ate<br />

investigati<strong>on</strong>s before the UK and EU authorities as well as before the EU courts;<br />

successfully representing KirchMedia (now Infr<strong>on</strong>t) before the EU courts reversing<br />

approval of a UK law mandating free-to-air coverage of the FIFA World Cup; defending<br />

a large multinati<strong>on</strong>al bank in the Belgian Banks cartel investigati<strong>on</strong> of the European<br />

Commissi<strong>on</strong> into the fixing of currency c<strong>on</strong>versi<strong>on</strong> rates leading to a successful<br />

settlement; successfully defending a global software company in antitrust litigati<strong>on</strong><br />

before the Greek courts; securing access to interface informati<strong>on</strong> for a complainant from<br />

the UK competiti<strong>on</strong> authorities in respect of a dominant software vendor; successfully<br />

defending abuse of dominance investigati<strong>on</strong>s by the EU and German authorities in<br />

relati<strong>on</strong> to a well known global IT company.<br />

Bill graduated from Bristol University and has also studied at the University of Hanover.<br />

Bill qualified as a solicitor (England & Wales) in 1998.<br />

In additi<strong>on</strong> to in-house and client briefs <strong>on</strong> competiti<strong>on</strong> law, commercial and gambling<br />

issues, Bill’s external publicati<strong>on</strong>s include c<strong>on</strong>tributing to Butterworths Competiti<strong>on</strong> Law,<br />

Cartels Chapter, Sweet & Maxwell’s IT Encyclopaedia, Competiti<strong>on</strong> Law Chapter,<br />

authoring “B2B Marketplaces and EC Competiti<strong>on</strong> Law” (Antitrust Bulletin), “Applicati<strong>on</strong><br />

of the Technology Transfer Block Exempti<strong>on</strong> to Software Licensing Agreements”<br />

(CTLR); “The Fallout from Microsoft: The Court of First Instance Leaves Critical IT<br />

Industry Issues Unanswered” (CTLR); Premier League: the Implicati<strong>on</strong>s for Copyright<br />

(ECLR); Antitrust in the IT Industry: Recent Merger C<strong>on</strong>trol Issues (e-C<strong>on</strong>currences)<br />

MICHAEL BAYE is the Bert Elwert Professor of Business at Indiana University’s Kelley<br />

School of Business. He served as the Director of the Bureau of Ec<strong>on</strong>omics at the US<br />

Federal Trade Commissi<strong>on</strong> during 2007 and 2008. Michael is also a Special C<strong>on</strong>sultant<br />

for NERA Ec<strong>on</strong>omic C<strong>on</strong>sulting, and has provided expert testim<strong>on</strong>y in matters ranging<br />

from advertising and pricing to mergers and m<strong>on</strong>opolizati<strong>on</strong>. He has provided written<br />

and oral expert testim<strong>on</strong>y for the Canadian Competiti<strong>on</strong> Bureau, the US Department of<br />

Justice, and numerous private parties.<br />

2

Professor Baye has w<strong>on</strong> numerous awards for his outstanding teaching and research,<br />

and has published several textbooks. His research focuses mainly <strong>on</strong> pricing strategies<br />

and their impact <strong>on</strong> c<strong>on</strong>sumer welfare and firm profits in both <strong>on</strong>line and traditi<strong>on</strong>al<br />

markets. His academic work <strong>on</strong> mergers, aucti<strong>on</strong>s, patents, advertising, <strong>on</strong>line markets<br />

and other areas related to antitrust and c<strong>on</strong>sumer protecti<strong>on</strong> has been published in<br />

leading ec<strong>on</strong>omics and marketing journals. Additi<strong>on</strong>ally, his academic research <strong>on</strong><br />

pricing strategies in <strong>on</strong>line markets has been featured in The Wall Street Journal,<br />

Forbes, and The New York Times.<br />

Michael has lectured and spoken at c<strong>on</strong>ferences and academic instituti<strong>on</strong>s throughout<br />

North America and Europe, and has held visiting appointments at Cambridge, Oxford,<br />

Erasmus University, Tilburg University, and the New Ec<strong>on</strong>omic School in Moscow. In<br />

additi<strong>on</strong> to his extensive academic publicati<strong>on</strong>s and practical antitrust experience, he<br />

has also served <strong>on</strong> numerous editorial boards in ec<strong>on</strong>omics as well as marketing.<br />

Professor Baye received his B.S. from Texas A&M University in 1980 and his Ph.D. in<br />

ec<strong>on</strong>omics from Purdue University in 1983.<br />

ROXANE C. BUSEY, a partner in the <str<strong>on</strong>g>Chicago</str<strong>on</strong>g> office of Baker & McKenzie, is a<br />

nati<strong>on</strong>ally recognized antitrust attorney. She served as Chair of the ABA Secti<strong>on</strong> of<br />

Antitrust Law in 2001-02 and as Chair of the Secti<strong>on</strong>’s Task Force <strong>on</strong> the Antitrust<br />

Modernizati<strong>on</strong> Commissi<strong>on</strong> from 2003-2007. She is also featured in the ABA Antitrust<br />

Secti<strong>on</strong>’s Oral History, which is available <strong>on</strong> the Secti<strong>on</strong>’s website.<br />

Ms. Busey’s practice includes both antitrust counseling and litigati<strong>on</strong>. She has<br />

practiced before the Federal Trade Commissi<strong>on</strong>, the Department of Justice, and various<br />

state antitrust enforcement agencies. A significant porti<strong>on</strong> of Ms. Busey’s practice<br />

relates to mergers, joint ventures and strategic alliances. She has obtained merger<br />

clearance from the FTC or the DOJ for numerous transacti<strong>on</strong>s in various industries,<br />

including a recent transacti<strong>on</strong> for $1.3 billi<strong>on</strong> involving IFCO Systems NV where the<br />

FTC issued a Sec<strong>on</strong>d Request but closed the investigati<strong>on</strong> and terminated the waiting<br />

period prior to IFCO certifying substantial compliance. She also works in c<strong>on</strong>juncti<strong>on</strong><br />

with the firm’s global competiti<strong>on</strong> network of over 250 competiti<strong>on</strong> lawyers to provide<br />

multijurisdicti<strong>on</strong>al merger c<strong>on</strong>trol and other antitrust advice.<br />

Ms. Busey’s litigati<strong>on</strong> experience includes both civil and criminal matters. She was <strong>on</strong>e<br />

of the lead counsel successfully defending the Nati<strong>on</strong>al Resident Matching Program in<br />

Jung v. AAMC, an antitrust class acti<strong>on</strong> lawsuit filed by three medical residents alleging<br />

a wage fixing c<strong>on</strong>spiracy am<strong>on</strong>g the nati<strong>on</strong>’s leading teaching hospitals. She served as<br />

a Special Master in an antitrust health care case pending in federal district court. She<br />

recently represented clients in criminal cartel cases before the DOJ and has<br />

represented clients in class acti<strong>on</strong> price fixing cases in federal court.<br />

Ms. Busey has developed global antitrust compliance programs, given antitrust training,<br />

and c<strong>on</strong>ducted compliance audits in many industries for many companies and<br />

3

associati<strong>on</strong>s. She has counseled companies with large or dominant market shares <strong>on</strong> a<br />

variety of practices, including exclusi<strong>on</strong>ary c<strong>on</strong>duct, essential facility, refusals to deal,<br />

tying arrangements, bundled discounts, and resale pricing. She also has addressed<br />

antitrust intellectual property issues in licensing and pooling agreements, and she was<br />

involved in an FTC investigati<strong>on</strong> involving standard setting and related intellectual<br />

property issues.<br />

Ms. Busey has been recognized for at least a decade as a leading antitrust authority by<br />

Chambers USA America’s Leading Business Lawyers; The Best Lawyers in America;<br />

Who’s Who in America; Competiti<strong>on</strong> & Antitrust Expert Guide; Global Counsel,<br />

Competiti<strong>on</strong> Law Handbook; Guide to the World’s Leading Competiti<strong>on</strong> and Antitrust<br />

Lawyers; Illinois Leading Lawyers Network; Illinois Top 50 Business Lawyers; Illinois<br />

Top 10 Women Lawyers; and Illinois Top 10 Women Litigators.<br />

Ms. Busey is a frequent lecturer and author <strong>on</strong> antitrust issues. She has been co-chair<br />

of the Practicing Lawyers Institute’s antitrust program in <str<strong>on</strong>g>Chicago</str<strong>on</strong>g> for over a decade,<br />

where she regularly speaks <strong>on</strong> Relati<strong>on</strong>ships Am<strong>on</strong>g Competitors. She also regularly<br />

speaks <strong>on</strong> Antitrust Counseling for the Antitrust Secti<strong>on</strong>’s biannual Master’s Program.<br />

She has testified before the FTC <strong>on</strong> Mergers, Joint Ventures; Efficiencies and Global<br />

Competiti<strong>on</strong>; Intellectual Property; and Health Care. She is also <strong>on</strong>e of the founders of<br />

the annual <str<strong>on</strong>g>Chicago</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Forum</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> Internati<strong>on</strong>al Antitrust Issues sp<strong>on</strong>sored by the Searle<br />

Foundati<strong>on</strong> and Northwestern Law School.<br />

Ms. Busey received her law degree from Northwestern Law School.<br />

MILDRED L. CALHOUN retired in June 2011 after 12 years as the Senior Antitrust and<br />

Trade Regulati<strong>on</strong> lawyer at BP America Inc., the US affiliate of BP plc, <strong>on</strong>e of the<br />

world’s largest integrated oil companies. Her practice included counseling <strong>on</strong> antitrust<br />

issues in all of BP’s businesses, including explorati<strong>on</strong> and producti<strong>on</strong> of oil and gas,<br />

refining and retail gasoline sales, chemicals and commodities trading. She was<br />

resp<strong>on</strong>sible for BP’s US antitrust compliance programs and c<strong>on</strong>ducted many hours of<br />

training programs worldwide every year. She supported BP’s Mergers & Acquisiti<strong>on</strong><br />

Group in providing market analysis and merger counseling. This includes resp<strong>on</strong>sibility<br />

for Hart Scott Rodino filings and advice.<br />

Prior to joining BP in 1999, Ms. Calhoun was employed by the Antitrust Divisi<strong>on</strong> of the<br />

United States Department of Justice for seventeen years.<br />

Ms. Calhoun has written and lectured <strong>on</strong> topics relating to antitrust. She has been a<br />

member of the faculty of the Practicing Law Institute’s <str<strong>on</strong>g>Annual</str<strong>on</strong>g> Antitrust Law Institute<br />

since 2002 and was an adjunct member of the faculty of the Indiana University School<br />

of Law at Indianapolis.<br />

She was Chair of the Antitrust & Unfair Competiti<strong>on</strong> Law Secti<strong>on</strong> Council of the Illinois<br />

State Bar Associati<strong>on</strong> from 2008-2009. She is a member of the American Bar<br />

4

Associati<strong>on</strong> and was a member of the Advisory Board of the Corporate Counseling<br />

Committee (Antitrust Secti<strong>on</strong>).<br />

Ms. Calhoun earned her J.D., in 1978 from Indiana University School of Law and her<br />

B.A. in 1975 from Northwestern University. She is admitted to the bars in Indiana,<br />

Illinois and Washingt<strong>on</strong>, D.C.<br />

THOMAS CAMPBELL is senior counsel with Baker & McKenzie LLP in <str<strong>on</strong>g>Chicago</str<strong>on</strong>g> and<br />

has more than 30 years of experience trying cases in a wide variety of industries,<br />

including defending a pipeline company accused of m<strong>on</strong>opolizing the transportati<strong>on</strong> of<br />

natural gas, a maker of grand pianos accused of m<strong>on</strong>opolizati<strong>on</strong>, and a baking<br />

company accused of predatory pricing. He has been <strong>on</strong> the winning side in seven of<br />

eight antitrust cases tried to verdict or decisi<strong>on</strong>.<br />

Mr. Campbell focuses <strong>on</strong> the trial of antitrust acti<strong>on</strong>s and business disputes. He is<br />

particularly recognized for having tried a series of prominent cases in the healthcare<br />

field that have c<strong>on</strong>tributed to the development of antitrust law applicati<strong>on</strong> in the<br />

healthcare industry.<br />

Mr. Campbell is a graduate of Cornell Law School (J.D.) (1968) and Dartmouth College<br />

(B.A.) (1965).<br />

RUSSELL DAMTOFT is the Associate Director of the Federal Trade Commissi<strong>on</strong>’s<br />

Office of Internati<strong>on</strong>al Affairs. He is part of the teams that are resp<strong>on</strong>sible for building<br />

relati<strong>on</strong>ships between the FTC and antitrust agencies in China and India, as well as<br />

maintaining <strong>on</strong>going relati<strong>on</strong>ships with Canada, Latin America, and Russia. He also<br />

manages porti<strong>on</strong>s of the FTC’s technical assistance program for developing competiti<strong>on</strong><br />

agencies. He has provided technical assistance to newer competiti<strong>on</strong> agencies in<br />

numerous countries, in Latin America, Central and Eastern Europe, the former Soviet<br />

Uni<strong>on</strong>, India, Pakistan, and China, which included stints as a l<strong>on</strong>g-term advisor in<br />

Lithuania and Romania.<br />

Mr. Damtoft has been with the Federal Trade Commissi<strong>on</strong> since 1985. Before the<br />

Office of Internati<strong>on</strong>al Affairs was established, he performed similar duties in the Bureau<br />

of Competiti<strong>on</strong>, served as Assistant Regi<strong>on</strong>al Director of the FTC’s <str<strong>on</strong>g>Chicago</str<strong>on</strong>g> Regi<strong>on</strong>al<br />

Office, as Assistant to the Director of the Bureau of C<strong>on</strong>sumer Protecti<strong>on</strong>, Attorney-<br />

Advisor to a Commissi<strong>on</strong>er, and as a staff attorney in the Bureau of C<strong>on</strong>sumer<br />

Protecti<strong>on</strong>.<br />

He graduated from the University of Iowa College of Law in 1981 and from Grinnell<br />

College in 1976. He is a member of the American Bar Associati<strong>on</strong>, where he serves <strong>on</strong><br />

the Editorial Board of Competiti<strong>on</strong> Laws Outside of the United States.<br />

5

ALICE W. DETWILER is a senior attorney, antitrust with Microsoft Corporati<strong>on</strong> where<br />

she has been since 2007. Prior to this she was an associati<strong>on</strong> with DLA Piper and a<br />

member, Bureau of Competiti<strong>on</strong>, Office of Policy and Evaluati<strong>on</strong>, Federal Trade<br />

Commissi<strong>on</strong>, 2001-2003.<br />

Ms. Detwiler is a graduati<strong>on</strong> of Princet<strong>on</strong> University, A.B., cum laude, 1991 and Harvard<br />

Law School, J.D. magna cum laude, 1994.<br />

KARINE R. FADEN is Managing Counsel – Regulatory, Antitrust & Competiti<strong>on</strong> for<br />

United Airlines, based in its Washingt<strong>on</strong>, DC office.<br />

At United, Ms. Faden is in charge of regulatory legal matters with the DOT, FAA, TSA,<br />

CBP and other U.S. regulatory agencies, as well as antitrust and competiti<strong>on</strong> law<br />

worldwide. Her antitrust resp<strong>on</strong>sibilities range from ensuring global antitrust compliance<br />

to providing the full range of strategic and agency counseling. Prior to joining United,<br />

Ms. Faden practiced in the Washingt<strong>on</strong>, DC antitrust group of Freshfields Bruckhaus<br />

Deringer, where she focused <strong>on</strong> aviati<strong>on</strong> and represented various Star Alliance carriers.<br />

Ms. Faden received her JD from the Georgetown University Law Center, together with<br />

an MPH from the Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health. She is admitted to<br />

the bars of New York and Washingt<strong>on</strong>, DC, and lives in Washingt<strong>on</strong>, D.C. with her<br />

husband and two children.<br />

NICHOLAS J. FRANCZYK is Counsel for Internati<strong>on</strong>al Technical Assistance in the<br />

Federal Trade Commissi<strong>on</strong>’s Office of Internati<strong>on</strong>al Affairs. He has been an attorney<br />

with the Federal Trade Commissi<strong>on</strong> since 1987, where he has worked <strong>on</strong> various<br />

antitrust and c<strong>on</strong>sumer protecti<strong>on</strong> matters. As Counsel for Internati<strong>on</strong>al Technical<br />

Assistance, Nick is resp<strong>on</strong>sible for providing various assistance and training to foreign<br />

agencies in the areas of competiti<strong>on</strong> and c<strong>on</strong>sumer protecti<strong>on</strong> law and policy, including<br />

training of pers<strong>on</strong>nel in substantive legal principles, analytical framework, and<br />

investigative techniques. He has served as l<strong>on</strong>g‐term resident advisor to the South<br />

African Competiti<strong>on</strong> Commissi<strong>on</strong> (July– November 2004 and April–September 2008)<br />

and to the Ind<strong>on</strong>esian Business Competiti<strong>on</strong> Supervisory Commissi<strong>on</strong> (January–April<br />

2004). He has participated in more than forty training programs for competiti<strong>on</strong> and<br />

c<strong>on</strong>sumer protecti<strong>on</strong> authorities throughout the world, including bilateral programs in<br />

India, Ind<strong>on</strong>esia, Kenya, Mozambique, the Philippines, Russia, South Africa, Tanzania,<br />

Vietnam, and Zambia, and regi<strong>on</strong>al workshops in Colombia, Ghana, Hungary, Kenya,<br />

Korea, Slovakia, South Africa, Vietnam, and Zambia. He has prepared written<br />

comments <strong>on</strong> numerous draft competiti<strong>on</strong> laws, rules and regulati<strong>on</strong>s. In additi<strong>on</strong>, he<br />

has c<strong>on</strong>ducted commercial law assessments in Ind<strong>on</strong>esia (2007), Kenya (2009) and<br />

Tanzania (2007 and 2010) for the United States Agency for Internati<strong>on</strong>al Development.<br />

PAUL FRONTCZAK is Senior Americas Antitrust Counsel at Shell Oil Company where<br />

he advises management regarding antitrust and other legal issues associated with<br />

6

general commercial activities and strategic business initiatives, including mergers and<br />

acquisiti<strong>on</strong>s, joint ventures and alliances. Prior to joining Shell, Paul was Counsel in the<br />

Washingt<strong>on</strong> D.C. office of Clifford Chance where he represented merging parties, thirdparty<br />

complainants, potential divestiture candidates and targets of government<br />

investigati<strong>on</strong>s in their dealings with the Federal Trade Commissi<strong>on</strong>, the Department of<br />

Justice, State Attorneys General, Department of Defense, CFIUS and foreign<br />

regulators. Paul was also a Lead Attorney in the Mergers I divisi<strong>on</strong> of the United States<br />

Federal Trade Commissi<strong>on</strong> where he led merger investigati<strong>on</strong>s and secured a number<br />

of multi-billi<strong>on</strong> dollar enforcement acti<strong>on</strong>s.<br />

Late this year Paul is taking a new positi<strong>on</strong> at Shell as Senior Counsel, Anti-bribery and<br />

Corrupti<strong>on</strong> and Antitrust for Asia. He will be based in Singapore.<br />

Paul has an MBA from Rice University, a J.D. from Albany Law School and a B.A from<br />

Muhlenberg College.<br />

SAMIR R. GANDHI heads the Competiti<strong>on</strong> practice at AZB & Partners and deals with a<br />

broad range of competiti<strong>on</strong> law and policy issues.<br />

Samir has represented the Competiti<strong>on</strong> Commissi<strong>on</strong> of India (CCI) as its counsel in its<br />

early litigati<strong>on</strong> so<strong>on</strong> after it was made operati<strong>on</strong>al, including in its first appeal at the<br />

Supreme Court of India. He has also advised clients-both as complainants and as<br />

defendants, in several cartel and abuse of dominance cases, including in sectors such<br />

as cement, pharmaceuticals, internet search & advertising, automobiles and others.<br />

Samir has worked <strong>on</strong> numerous merger filings since the enforcement of the merger<br />

c<strong>on</strong>trol provisi<strong>on</strong>s in India and was part of the advisory team to the Commissi<strong>on</strong> that<br />

helped give shape to the 2011 merger regulati<strong>on</strong>s. He has advised Pfizer in the<br />

acquisiti<strong>on</strong> of its nutriti<strong>on</strong> business by Nestle, Google in the acquisiti<strong>on</strong> of assets by Intel<br />

from Motorola Mobility, Qualcomm in its merger of Indian entities with Bharti Airtel<br />

am<strong>on</strong>gst others.<br />

Samir also routinely advises <strong>on</strong> competiti<strong>on</strong> compliance programmes and has also been<br />

involved in framing competiti<strong>on</strong> policy for the Competiti<strong>on</strong> Commissi<strong>on</strong> of India as well<br />

as the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan. He is a member of the Internati<strong>on</strong>al Bar<br />

Associati<strong>on</strong> working group <strong>on</strong> merger regulati<strong>on</strong> and frequently publishes and speaks<br />

<strong>on</strong> competiti<strong>on</strong> law.<br />

Samir is a graduate of the Nati<strong>on</strong>al Law School of India University, Bangalore and the<br />

L<strong>on</strong>d<strong>on</strong> School of Ec<strong>on</strong>omics and Political Science, where he was a Comm<strong>on</strong>wealth<br />

Scholar and Mahindra Trust Fellow. He was a visiting fellow at Columbia Law School<br />

and is admitted to practise in India.<br />

ANNE GRON is a vice president at NERA Ec<strong>on</strong>omic C<strong>on</strong>sulting specializing in<br />

ec<strong>on</strong>omic research and analyses in the areas of securities and finance, intellectual<br />

7

property and antitrust. Dr. Gr<strong>on</strong> has worked <strong>on</strong> competiti<strong>on</strong>-related matters involving<br />

companies in insurance distributi<strong>on</strong>, automobile insurance, and financial instituti<strong>on</strong>s.<br />

She has also worked <strong>on</strong> matters involving companies in a number of markets and<br />

industries including life insurance, annuities, reinsurance, mortgage financing, retail<br />

deposits, marketing databases, artificial joints, computer peripherals, beverage<br />

distributi<strong>on</strong>, airlines, automotive repair, mutual funds, and discount retailing.<br />

Dr. Gr<strong>on</strong>’s work has been published in a number of the top ec<strong>on</strong>omic journals including<br />

the Rand Journal of Ec<strong>on</strong>omics, the Journal of Industrial Ec<strong>on</strong>omics, the Journal of Law<br />

and Ec<strong>on</strong>omics, the Review of Ec<strong>on</strong>omics and Statistics, and the American Ec<strong>on</strong>omic<br />

Review.<br />

Prior to joining NERA, Dr. Gr<strong>on</strong> taught Competitive Strategy, Microec<strong>on</strong>omics and Risk<br />

Management and Insurance to MBA students at Kellogg School of Management and at<br />

the Graduate School of Business (now Booth) at the University of <str<strong>on</strong>g>Chicago</str<strong>on</strong>g>. Dr. Gr<strong>on</strong><br />

received her PhD in ec<strong>on</strong>omics from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, with<br />

c<strong>on</strong>centrati<strong>on</strong>s in industrial organizati<strong>on</strong> and regulati<strong>on</strong>, and public finance. She<br />

received her BA, magna cum laude, in ec<strong>on</strong>omics and computer science from Williams<br />

College.<br />

JOHN HARKRIDER is co-chair of Axinn, Veltrop & Harkrider’s antitrust practice. His<br />

practice c<strong>on</strong>centrates <strong>on</strong> mergers, counseling and litigati<strong>on</strong>. In the merger c<strong>on</strong>text, he<br />

advised Google in c<strong>on</strong>necti<strong>on</strong> with its acquisiti<strong>on</strong>s of Motorola Mobility and hA Software.<br />

He represented Cingular in its $41 billi<strong>on</strong> acquisiti<strong>on</strong> by BellSouth and BellSouth in its<br />

$86 billi<strong>on</strong> acquisiti<strong>on</strong> by AT&T and is currently representing Thermo Fisher in its $13<br />

billi<strong>on</strong> acquisiti<strong>on</strong> of Life. In litigati<strong>on</strong>, he has represented Tys<strong>on</strong> Foods in litigati<strong>on</strong><br />

against the DOJ, and represented United Technologies Corporati<strong>on</strong> in Walker Process<br />

and Sham Litigati<strong>on</strong> Secti<strong>on</strong> 2 claims. He also represented the U.S. Department of<br />

Justice in its investigati<strong>on</strong> and suit to enjoin WorldCom’s attempted acquisiti<strong>on</strong> of Sprint,<br />

which was the largest merger ever challenged by the DOJ.<br />

Recently, he represented Google and Motorola Mobility in c<strong>on</strong>necti<strong>on</strong> with the FTC’s<br />

standard-essential patent investigati<strong>on</strong>. He also represents Red Hat <strong>on</strong> patent/antitrust<br />

issues.<br />

H. STEPHEN HARRIS, JR. is a partner in Baker & McKenzie’s Global Antitrust &<br />

Competiti<strong>on</strong> Group. Mr. Harris is widely published and globally recognized as a leading<br />

antitrust lawyer and commercial litigator by publicati<strong>on</strong>s including Chambers USA<br />

(2004-2011), Internati<strong>on</strong>al Who's Who of Competiti<strong>on</strong> Lawyers (2000-2011), and PLC<br />

Which Lawyer? (2001-2011).<br />

Mr. Harris practices antitrust law, including class acti<strong>on</strong>s and cartel and merger<br />

investigati<strong>on</strong>s, before US and internati<strong>on</strong>al courts and agencies. He also represents<br />

financial instituti<strong>on</strong>s in complex regulatory and commercial litigati<strong>on</strong>.<br />

8

Mr. Harris handles civil and criminal antitrust litigati<strong>on</strong> and cartel investigati<strong>on</strong>s in a<br />

broad range of industries, including financial instituti<strong>on</strong>s, pharmaceuticals, informati<strong>on</strong><br />

technology, electr<strong>on</strong>ics, health care, c<strong>on</strong>sumer products, retail, and software. He also<br />

has represented major m<strong>on</strong>ey-center banks in numerous cases against US financial<br />

regulatory agencies<br />

Mr. Harris attended Columbia Law School (J.D. H<strong>on</strong>ors, Harlan Fiske St<strong>on</strong>e Scholar)<br />

(1982) and Cornell University (A.B. magna cum laude, College Scholar) (1977).<br />

NEVILLE (NED) HEDLEY is the Director of Internal Investigati<strong>on</strong>s at Abbott<br />

Laboratories. Prior to that Mr. Hedley was a Trial Attorney at the U.S. Department of<br />

Justice, Antitrust Divisi<strong>on</strong>, Midwest Field Office from 2009 – 2012 where he worked<br />

primarily <strong>on</strong> nati<strong>on</strong>wide bid-rigging and market manipulati<strong>on</strong> investigati<strong>on</strong> and related<br />

prosecuti<strong>on</strong>s c<strong>on</strong>cerning the municipal finance and municipal derivatives market. Mr.<br />

Hedley was also Senior Trial Attorney, U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commissi<strong>on</strong>,<br />

Enforcement Divisi<strong>on</strong>, <str<strong>on</strong>g>Chicago</str<strong>on</strong>g> Office from 2007 – 2009 and Assistant U.S. Attorney,<br />

Southern District of California, San Diego, CA, Criminal Divisi<strong>on</strong> from 2004 – 2007 and<br />

Associate, <strong>Mayer</strong> <strong>Brown</strong>, Tax C<strong>on</strong>troversy Group, <str<strong>on</strong>g>Chicago</str<strong>on</strong>g> Office from 1997 – 2004.<br />

He received his B.A. from Wake Forest University, his J.D. from New England School of<br />

Law, his LL.M. from New York University School of Law and his M.B.A. Northwestern<br />

University Graduate School of Business.<br />

ROY HOFFINGER is Vice President, Legal Counsel, for Qualcomm, Inc, a positi<strong>on</strong> he<br />

has held since October 2006. At Qualcomm, Mr. Hoffinger is resp<strong>on</strong>sible for antitrust<br />

and competiti<strong>on</strong> law matters. Prior to joining Qualcomm, Mr. Hoffinger was a member of<br />

Perkins, Coie LLP and Holme, Roberts & Owen in Denver, Colorado, where he<br />

practiced antitrust and regulatory law. Prior to returning to private practice, Mr. Hoffinger<br />

spent 14 years as in-house counsel for Qwest and AT&T, as Vice President, Chief<br />

Counsel for Federal and State Regulati<strong>on</strong>, and Chief Counsel, Antitrust & Federal<br />

Regulati<strong>on</strong>, respectively. Mr. Hoffinger currently serves <strong>on</strong> the Advisory Board of the<br />

Silic<strong>on</strong> Flatir<strong>on</strong>s Telecommunicati<strong>on</strong>s Program sp<strong>on</strong>sored by the University of Colorado.<br />

He received his J.D. from the University of <str<strong>on</strong>g>Chicago</str<strong>on</strong>g> Law School in 1982.<br />

NATHALIE JALABERT DOURY is the head of <strong>Mayer</strong> <strong>Brown</strong>’s Antitrust and<br />

Competiti<strong>on</strong> in the Paris office.<br />

Nathalie has developed an extensive practice in all aspects of competiti<strong>on</strong> law at both a<br />

nati<strong>on</strong>al and European level, including: cartels, c<strong>on</strong>certed practices and abuse of<br />

dominance, mergers, horiz<strong>on</strong>tal and vertical agreements as well as State aids.<br />

She regularly advises companies <strong>on</strong> compliance issues and has recently coordinated<br />

with Theodore Banks (Compliance and Competiti<strong>on</strong> C<strong>on</strong>sultants) an internati<strong>on</strong>al<br />

survey <strong>on</strong> competiti<strong>on</strong> law compliance programs covering 17 antitrust regimes around<br />

9

the world. The study was published in the C<strong>on</strong>currences Review N°2/2012. She is a<br />

member of the Antitrust & Competiti<strong>on</strong> Law Compliance <str<strong>on</strong>g>Forum</str<strong>on</strong>g>.<br />

Nathalie earned a Master's Degree in English and North American Business Law (DEA)<br />

from the Université Paris I Panthé<strong>on</strong>-Sorb<strong>on</strong>ne, and a Master's Degree in Internati<strong>on</strong>al<br />

Business Law (DESS) from the Université Paris X Nanterre.<br />

JOHN “JAY” JURATA, a partner in Orrick’s Washingt<strong>on</strong>, D.C., office, is a member of<br />

the Antitrust and Competiti<strong>on</strong> Group. His practice covers all areas of U.S. and EU<br />

competiti<strong>on</strong> law, with an emphasis <strong>on</strong> antitrust and intellectual property issues involving<br />

technology markets.<br />

Mr. Jurata has wide experience representing clients in government investigati<strong>on</strong>s<br />

relating to m<strong>on</strong>opolizati<strong>on</strong> and abuse of dominance, mergers and acquisiti<strong>on</strong>s, and<br />

high-stakes antitrust and intellectual property litigati<strong>on</strong>. He also provides counseling<br />

advice regarding the strategic use of patents, intellectual property licensing,<br />

interoperability, tying/bundling, pricing, distributi<strong>on</strong>, and competitor collaborati<strong>on</strong>s. Mr.<br />

Jurata has participated in six trials in federal/state courts and appears regularly before<br />

the U.S. Department of Justice Antitrust Divisi<strong>on</strong>, the U.S. Federal Trade Commissi<strong>on</strong>,<br />

the European Commissi<strong>on</strong> Directorate General for Competiti<strong>on</strong>, the U.S. Internati<strong>on</strong>al<br />

Trade Commissi<strong>on</strong>, and various State Attorneys General offices.<br />

Prior to entering the legal professi<strong>on</strong>, Mr. Jurata served as an officer in the United<br />

States Navy.<br />

NELSON JUNG is the Director of Mergers at the Office of Fair Trading where, until<br />

recently, he was a Director of Competiti<strong>on</strong> Enforcement. He is a qualified lawyer in<br />

Germany as well as a Solicitor in England and Wales. Having qualified as a lawyer in<br />

Germany in 2002, Nels<strong>on</strong> completed an LLM at University College L<strong>on</strong>d<strong>on</strong>, specialising<br />

in European Law. He then joined the Antitrust practice group at Clifford Chance LLP in<br />

L<strong>on</strong>d<strong>on</strong> before, as a Senior Associate, he moved to the Office of Fair Trading in 2010.<br />

Nels<strong>on</strong> is the author of the chapter <strong>on</strong> “Air Transport and EC competiti<strong>on</strong> law” in<br />

Competiti<strong>on</strong> Law of the European Community (LexisNexis) and has written several<br />

articles <strong>on</strong> developments <strong>on</strong> EU and competiti<strong>on</strong> law in publicati<strong>on</strong>s such as<br />

Competiti<strong>on</strong> Policy Internati<strong>on</strong>al and Competiti<strong>on</strong> Law Insight. His experience includes<br />

advising <strong>on</strong> mergers and acquisiti<strong>on</strong>s under the EU Merger Regulati<strong>on</strong>, joint ventures,<br />

cartels, abuses of dominance as well as vertical and horiz<strong>on</strong>tal agreements across a<br />

wide range of sectors.<br />

CHRISTOPHER KELLY has an antitrust litigati<strong>on</strong> practice that focuses <strong>on</strong> the<br />

applicati<strong>on</strong> of antitrust law to the acquisiti<strong>on</strong> and use of intellectual property rights. He<br />

counsels and represents clients regarding antitrust implicati<strong>on</strong>s of patent infringement<br />

litigati<strong>on</strong> and settlement, patent pools, licensing, and standard-setting. He also<br />

10

frequently advises and represents clients <strong>on</strong> distributi<strong>on</strong>-related antitrust issues. Chris<br />

co-authored the Supreme Court briefs in Illinois Tool Works Inc. v. Independent Ink,<br />

Inc., which led to an important antitrust victory for intellectual property owners. He has<br />

advised and represented several major innovator pharmaceutical firms in c<strong>on</strong>necti<strong>on</strong><br />

with the initiati<strong>on</strong> and settlement of Hatch-Waxman patent infringement litigati<strong>on</strong>. He<br />

speaks frequently at CLE programs <strong>on</strong> mitigating antitrust risk in settling Hatch-Waxman<br />

infringement litigati<strong>on</strong>. Prior to entering private practice, Chris served in several<br />

significant positi<strong>on</strong>s over 16 years at the United States Department of Justice, Antitrust<br />

Divisi<strong>on</strong>. From 1996 until 2001, he was the Divisi<strong>on</strong>’s Senior Counsel for Intellectual<br />

Property, advising Justice Department officials <strong>on</strong> infringement settlements, patent<br />

pools, competitor collaborati<strong>on</strong>s, the future of the Internet Domain Name System,<br />

database protecti<strong>on</strong>, and other important IP-related legal and policy issues. He also<br />

was a Special Assistant US Attorney in the Eastern District of Virginia, and following law<br />

school served a judicial clerkship with Judge John A. Terry of the District of Columbia<br />

Court of Appeals.<br />

NICK KOBERSTEIN Based at the company’s headquarters near <str<strong>on</strong>g>Chicago</str<strong>on</strong>g>, Illinois, Nick<br />

serves as Abbott’s in-house antitrust specialist. His resp<strong>on</strong>sibilities include leading the<br />

company’s preparati<strong>on</strong> for antitrust agency reviews of proposed transacti<strong>on</strong>s and<br />

managing merger c<strong>on</strong>trol submissi<strong>on</strong>s before competiti<strong>on</strong> authorities <strong>on</strong> a global basis.<br />

He has successfully obtained merge c<strong>on</strong>trol clearances for Abbott transacti<strong>on</strong>s in<br />

numerous jurisdicti<strong>on</strong>s, including the US, EU, Russia, Korea, Colombia, Ukraine and<br />

Vietnam.<br />

Am<strong>on</strong>g Nick’s accomplishments at Abbott is obtaining merger c<strong>on</strong>trol clearances for the<br />

company’s $6.2 billi<strong>on</strong> acquisiti<strong>on</strong> of Solvay Pharmaceuticals in 2010. For this<br />

transacti<strong>on</strong>, Nick oversaw the submissi<strong>on</strong>s of over a dozen merger c<strong>on</strong>trol notificati<strong>on</strong>s<br />

around the World and led the company’s negotiati<strong>on</strong>s with the European Commissi<strong>on</strong><br />

that resulted in the Commissi<strong>on</strong> approving the transacti<strong>on</strong> during the Phase I review<br />

period, c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>ed <strong>on</strong> the company divesting Solvay’s cystic fibrosis testing business.<br />

Prior to joining Abbott, Nick was an antitrust partner in the Washingt<strong>on</strong>, D.C., office of<br />

McDermott Will & Emery, where he defended mergers, acquisiti<strong>on</strong>s and joint ventures<br />

before the Federal Trade Commissi<strong>on</strong>, Department of Justice, Department of Defense,<br />

CFIUS and state antitrust agencies. Representative transacti<strong>on</strong>s include:<br />

Mars Incorporated’s (the owner of Pedigree branded pet nutriti<strong>on</strong> products)<br />

acquisiti<strong>on</strong>s of Nutro Products, a leading producer of nutriti<strong>on</strong>al pet food<br />

products, the North American operati<strong>on</strong>s of Doane Pet Care, a leading<br />

manufacturer of private label pet food products, and Greenies, a leading<br />

manufacturer of pet snacks and treats;<br />

Jarden Corporati<strong>on</strong>’s acquisiti<strong>on</strong> of K2 Inc., which combined two leading sporting<br />

goods suppliers;<br />

11

The acquisiti<strong>on</strong> of ADVO, Inc., by Valassis Communicati<strong>on</strong>s, Inc., which<br />

combined two large marketing services providers; and<br />

H.I.G. Capital’s acquisiti<strong>on</strong> of Severn Trent Laboratories, which was merged with<br />

TestAmerica Inc. to create the largest envir<strong>on</strong>mental testing company in the US.<br />

Nick began his legal career as an attorney in the Mergers III and I Divisi<strong>on</strong>s of the<br />

Federal Trade Commissi<strong>on</strong>’s Bureau of Competiti<strong>on</strong>. During his eight years with the<br />

FTC, Nick led merger investigati<strong>on</strong>s in a wide variety of industries, four of which<br />

resulted in asset divestitures pursuant to c<strong>on</strong>sent agreements and three of which<br />

resulted in the parties aband<strong>on</strong>ing their proposed transacti<strong>on</strong>s.<br />

Nick earned his J.D. in 1994 from Georgetown University and his B.A. in 1990 from<br />

Michigan State University. He is admitted to the bars in Illinois and Washingt<strong>on</strong>, D.C.<br />

WILLIAM E. KOVACIC is the Global Competiti<strong>on</strong> Professor of Law and Policy and the<br />

Director of the Competiti<strong>on</strong> Law Center at the George Washingt<strong>on</strong> University Law<br />

School. Kovacic joined the George Washingt<strong>on</strong> faculty in 1999.<br />

From January 2006 to October 2011, Professor Kovacic was a member of the Federal<br />

Trade Commissi<strong>on</strong>, He chaired the agency from March 2008 until March 2009. From<br />

January 2009 to September 2011, he served as Vice Chair for Outreach of the<br />

Internati<strong>on</strong>al Competiti<strong>on</strong> Network. Professor Kovacic was the FTC’s General Counsel<br />

from 2001 through 2004, and also worked for the Commissi<strong>on</strong> from 1979 until 1983,<br />

initially in the Bureau of Competiti<strong>on</strong>’s Planning Office and later as an attorney advisor<br />

to former Commissi<strong>on</strong>er George W. Douglas.<br />

Kovacic was a member of the faculty at the George Mas<strong>on</strong> University School of Law<br />

from 1986 to 1999. From 1983 to 1986, he practiced antitrust and government<br />

c<strong>on</strong>tracts law with Bryan Cave’s Washingt<strong>on</strong>, DC, office. Earlier in his career, Kovacic<br />

spent <strong>on</strong>e year <strong>on</strong> the majority staff of the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee’s Antitrust<br />

and M<strong>on</strong>opoly Subcommittee.<br />

Beginning in 1992, Kovacic was an adviser <strong>on</strong> antitrust and c<strong>on</strong>sumer protecti<strong>on</strong> issues<br />

to the governments of Armenia, Benin, Egypt, El Salvador, Georgia, Guyana, Ind<strong>on</strong>esia,<br />

Kazakhstan, M<strong>on</strong>golia, Morocco, Nepal, Panama, Russia, Ukraine, Vietnam, and<br />

Zimbabwe.<br />

BRUNO LASSERRE is a member of the C<strong>on</strong>seil d’État, the French supreme<br />

administrative court, which he joined in 1978 after graduating from École Nati<strong>on</strong>ale<br />

d’Administrati<strong>on</strong> (ENA), the French nati<strong>on</strong>al school for civil service.<br />

Between 1989 and 1997, he served as Director for Regulatory Affairs, and then Director<br />

General for Posts and Telecommunicati<strong>on</strong>s at the French Ministry of Posts and<br />

Telecommunicati<strong>on</strong>s. In this positi<strong>on</strong>, he developed and implemented a comprehensive<br />

12

overhaul of the telecommunicati<strong>on</strong>s sector, culminating in its full opening to competiti<strong>on</strong><br />

as well as in the creati<strong>on</strong> of an independent regulator.<br />

He returned to the C<strong>on</strong>seil d’État in 1998, where he chaired the 1 st Chamber for three<br />

years, before becoming Deputy Chairman for all litigati<strong>on</strong> activities, between 2002 and<br />

2004.<br />

After serving as Member of the board of the C<strong>on</strong>seil de la c<strong>on</strong>currence (1998-2004), he<br />

was appointed President in July 2004, and in this capacity pushed through a major<br />

reform that transformed it into the Autorité de la c<strong>on</strong>currence, resp<strong>on</strong>sible for merger<br />

review and competiti<strong>on</strong> advocacy in additi<strong>on</strong> to antitrust enforcement. He has chaired<br />

the Autorité since then.<br />

He is also an Officer of the French Légi<strong>on</strong> d’h<strong>on</strong>neur and a Commander of the French<br />

Ordre nati<strong>on</strong>al du Mérite.<br />

MARK MCLAUGHLIN is a partner with <strong>Mayer</strong> <strong>Brown</strong> LLP in <str<strong>on</strong>g>Chicago</str<strong>on</strong>g>, and has<br />

c<strong>on</strong>centrated his practice <strong>on</strong> antitrust, securities class acti<strong>on</strong>s and related litigati<strong>on</strong>, and<br />

franchising and distributi<strong>on</strong> matters. He has litigated substantial antitrust cases<br />

involving a variety of industries and issues, including m<strong>on</strong>opolizati<strong>on</strong> claims, challenges<br />

to acquisiti<strong>on</strong>s, price fixing, exclusive dealing, sham litigati<strong>on</strong> and price discriminati<strong>on</strong><br />

claims, and claims involving practices in foreign commerce. He also regularly provides<br />

counseling in antitrust matters.<br />

Mark is a graduate of the University of Notre Dame Law School, JD magna cum laude<br />

and the University of Notre Dame, BA, summa cum laude.<br />

ROBERT MCLEOD is Chief Executive of MLex Ltd, Editor-in-Chief of MLex market<br />

intelligence and publisher of MLex magazine. He founded MLex, a service focused <strong>on</strong><br />

antitrust, trade and financial services regulati<strong>on</strong> and enforcement, in 2005 and has<br />

overseen the expansi<strong>on</strong> of the subscripti<strong>on</strong> based news service to cover energy and<br />

climate change regulati<strong>on</strong>, financial services and telecommunicati<strong>on</strong>s and media. MLex<br />

has operati<strong>on</strong>s in the US, Europe, China and Brazil.<br />

Robert McLeod writes extensively <strong>on</strong> antitrust and competiti<strong>on</strong> policy and is a frequent<br />

c<strong>on</strong>ference speaker <strong>on</strong> issues relating to policy implementati<strong>on</strong> in Brussels. As well as<br />

MLex, he is a frequent c<strong>on</strong>tributor to other publicati<strong>on</strong>s including The Banker, IP Law<br />

and Business, e-C<strong>on</strong>currences and the Competiti<strong>on</strong> Policy Internati<strong>on</strong>al Antitrust<br />

Journal.<br />

Prior to launching MLex, Mr McLeod worked for Bloomberg News in L<strong>on</strong>d<strong>on</strong>, Paris and<br />

Brussels covering financial services, mergers and acquisiti<strong>on</strong>s, and antitrust.<br />

13

BRITT M. MILLER is a partner in the <str<strong>on</strong>g>Chicago</str<strong>on</strong>g> office, where she practices in the areas<br />

of antitrust litigati<strong>on</strong> and complex commercial litigati<strong>on</strong>. She is co-leader of the <str<strong>on</strong>g>Chicago</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Litigati<strong>on</strong> Practice and a group leader of <strong>Mayer</strong> <strong>Brown</strong>’s Antitrust & Competiti<strong>on</strong><br />

practice. Britt focuses <strong>on</strong> representing domestic and internati<strong>on</strong>al corporati<strong>on</strong>s in pricefixing,<br />

market allocati<strong>on</strong>, m<strong>on</strong>opolizati<strong>on</strong>, and c<strong>on</strong>spiracy cases, and has also counseled<br />

clients <strong>on</strong> general antitrust issues. Since joining <strong>Mayer</strong> <strong>Brown</strong> in 1998, Britt has been<br />

involved in numerous antitrust cases including In re Vitamins Antitrust Litigati<strong>on</strong>, <strong>on</strong>e of<br />

the largest antitrust cases ever filed in the US. Her antitrust work has involved a variety<br />

of products and industries including synthetic rubber, aspartame, resins, household<br />

moving services, c<strong>on</strong>sumer health products, industrial chemicals, nursing services,<br />

fertilizers and vitamins.<br />

Britt’s general litigati<strong>on</strong> experience spans both the federal and state court systems and<br />

includes client representati<strong>on</strong>s relating to c<strong>on</strong>tract disputes, c<strong>on</strong>stituti<strong>on</strong>al rights,<br />

securities fraud, banking practices, airline deregulati<strong>on</strong>, products liability and trust<br />

interpretati<strong>on</strong>. Britt co-authored the "United States" chapter for the 2007-2012 editi<strong>on</strong>s<br />

of Global Competiti<strong>on</strong> Review’s "Private Antitrust Litigati<strong>on</strong>" treatise, is a c<strong>on</strong>tributing<br />

author to West’s Illinois Civil Discovery Practice, and has given numerous presentati<strong>on</strong>s<br />

<strong>on</strong> internati<strong>on</strong>al antitrust issues. She is a member of the American Bar Associati<strong>on</strong>’s<br />

Secti<strong>on</strong> of Antitrust Law and the Secti<strong>on</strong> of Litigati<strong>on</strong> and has been named a "Rising<br />

Star" in the Antitrust Litigati<strong>on</strong> secti<strong>on</strong>s of the Illinois Super Lawyers list published by<br />

Law & Politics since 2008. Britt was named also “Future Star” by Benchmark Litigati<strong>on</strong><br />

in 2010, 2011, 2012 and 2013. In additi<strong>on</strong>, she was recently named <strong>on</strong>e of Law 360’s<br />

“10 competiti<strong>on</strong> lawyers under 40 to watch.” Prior to joining <strong>Mayer</strong> <strong>Brown</strong>, Britt served<br />

as a Judicial Extern to the H<strong>on</strong>orable George M. Marovich, US District Court for the<br />

Northern District of Illinois (1997).<br />

Britt earned her BA from Auburn University and her JD from Northwestern University.<br />

MAUREEN K. OHLHAUSEN was sworn in as a Commissi<strong>on</strong>er of the Federal Trade<br />

Commissi<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong> April 4, 2012, to a term that expires in September 2018. Prior to joining<br />

the Commissi<strong>on</strong>, Ohlhausen was a partner at Wilkins<strong>on</strong> Barker Knauer, LLP, where she<br />

focused <strong>on</strong> FTC issues, including privacy, data protecti<strong>on</strong>, and cybersecurity.<br />

Ohlhausen previously served at the Commissi<strong>on</strong> for 11 years, most recently as Director<br />

of the Office of Policy Planning from 2004 to 2008, where she led the FTC’s Internet<br />

Access Task Force. She was also Deputy Director of that office. From 1998 to 2001,<br />

Ohlhausen was an attorney advisor for former FTC Commissi<strong>on</strong>er Ors<strong>on</strong> Swindle,<br />

advising him <strong>on</strong> competiti<strong>on</strong> and c<strong>on</strong>sumer protecti<strong>on</strong> matters. She started at the FTC<br />

General Counsel’s Office in 1997.<br />

Before coming to the FTC, Ohlhausen spent five years at the U.S. Court of Appeals for<br />

the D.C. Circuit, serving as a law clerk for Judge David B. Sentelle and as a staff<br />

attorney. Ohlhausen also clerked for Judge Robert Yock of the U.S. Court of Federal<br />

Claims from 1991 to 1992. Ohlhausen graduated with distincti<strong>on</strong> from George Mas<strong>on</strong><br />

University School of Law in 1991 and graduated with h<strong>on</strong>ors from the University of<br />

Virginia in 1984.<br />

14

Ohlhausen was <strong>on</strong> the adjunct faculty at George Mas<strong>on</strong> University School of Law,<br />

where she taught privacy law and unfair trade practices. She served as a Senior Editor<br />

of the Antitrust Law Journal and a member of the American Bar Associati<strong>on</strong> Task Force<br />

<strong>on</strong> Competiti<strong>on</strong> and Public Policy. She has authored a variety of articles <strong>on</strong> competiti<strong>on</strong><br />

law, privacy, and technology matters.<br />

CHARLES F. REGAN, JR., a partner in <strong>Mayer</strong> <strong>Brown</strong>’s <str<strong>on</strong>g>Chicago</str<strong>on</strong>g> office, currently serves<br />

as the Firm’s lead c<strong>on</strong>flicts attorney. He advises <strong>on</strong> legal and business c<strong>on</strong>flict issues,<br />

as well as other professi<strong>on</strong>al resp<strong>on</strong>sibility matters, that arise in <strong>Mayer</strong> <strong>Brown</strong>’s offices<br />

worldwide. Before taking <strong>on</strong> his c<strong>on</strong>flicts resp<strong>on</strong>sibilities, Chuck was a litigator who<br />

focused <strong>on</strong> benefits and ERISA litigati<strong>on</strong>, and has extensive experience in pensi<strong>on</strong><br />

class acti<strong>on</strong>s and commercial litigati<strong>on</strong>. He earned an AB from the University of<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Chicago</str<strong>on</strong>g> and a JD from Northwestern University School of Law, where he was<br />

Managing Editor of the Northwestern University Law Review. Before joining <strong>Mayer</strong><br />

<strong>Brown</strong>, Chuck clerked for the H<strong>on</strong>orable Marvin E. Aspen of the United States District<br />

Court for the Northern District of Illinois.<br />

THOMAS S. RESPESS, III has experience in all areas of antitrust, including the<br />

competitive analysis of mergers and acquisiti<strong>on</strong>s, price fixing and volume of commerce,<br />

and m<strong>on</strong>opolistic practices. In prior positi<strong>on</strong>s at the Federal Trade Commissi<strong>on</strong>, Tom<br />

developed expertise in the financial analysis of merger efficiency claims and failing firm<br />

defenses. He teams with other ec<strong>on</strong>omists in Baker & McKenzie C<strong>on</strong>sulting LLC to<br />