Why is modernity such a burden for graphic design?

Why is modernity such a burden for graphic design?

Why is modernity such a burden for graphic design?

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

credit that he was able to recognize and appreciate the emergence of a middle class and the values of its<br />

popular taste as being the driving <strong>for</strong>ce behind <strong>modernity</strong>.<br />

Modern now: The value of shock<br />

So what constitutes “shock” in 2008? Where do we turn to locate the marginal and d<strong>is</strong>enfranch<strong>is</strong>ed in<br />

contemporary <strong>graphic</strong> <strong>design</strong>? One possible option <strong>is</strong> to turn to critic<strong>is</strong>m itself. Similar to Baudelaire’s study<br />

of those figures derided by 19th century society, it <strong>is</strong> possible to look at contemporary critic<strong>is</strong>m itself to<br />

determine what our culture chooses to d<strong>is</strong>m<strong>is</strong>s now as a possible signifier of <strong>modernity</strong> today.<br />

One of the most infamous 20th-century critiques of <strong>graphic</strong> <strong>design</strong> was publ<strong>is</strong>hed in 1993 by writer and<br />

critic Steven Heller. In contrast to Baudelaire’s adventurous attitude toward the exigencies of <strong>modernity</strong>,<br />

Heller’s article, “The cult of the ugly,” lambasted the <strong>for</strong>ms of <strong>graphic</strong> <strong>design</strong> among an emerging<br />

generation as “ugly.” Originally publ<strong>is</strong>hed in the Brit<strong>is</strong>h <strong>graphic</strong> <strong>design</strong> magazine, Eye, Heller’s critic<strong>is</strong>m<br />

was precipitated by h<strong>is</strong> receiving a eight-page pamphlet produced by the graduate students of Cranbrook<br />

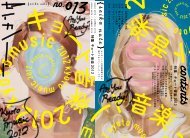

Academy of Art. [Fig.3] In writing about th<strong>is</strong> pamphlet, which Heller decidedly describes as ugly, he states,<br />

“Ask [what beauty <strong>is</strong>] to the Cranbrook Academy of Art students who created the ad hoc desktop<br />

publication, Output, and judge by the evidence that they might answer that beauty <strong>is</strong> chaos born of found<br />

letters layered on top of random patterns and shapes. [Fig.4] Those who value functional simplicity would<br />

argue that the Cranbrook students’ publication, like a toad’s warts, <strong>is</strong> ugly.” 5 [Fig.5] And Heller continues<br />

h<strong>is</strong> tirade, “Output <strong>is</strong> eight unbound pages of blips, type fragments, random words, and other <strong>graphic</strong><br />

minutiae purposely given the serendipitous look of a printer’s make-ready… Output could be considered a<br />

prime example of ugliness in the service of fashionable experimentation.” “As personal research, indeed as<br />

personal art, it can be justified, but as a model <strong>for</strong> commercial practice, th<strong>is</strong> kind of ugliness <strong>is</strong> a dead end.” 6<br />

But if Heller’s critique <strong>is</strong> held to the methods set <strong>for</strong>th by Baudelaire, clearly the shock value of the work<br />

Heller w<strong>is</strong>hes to d<strong>is</strong>m<strong>is</strong>s as “irrelevant,” suggests that th<strong>is</strong> work <strong>is</strong> modern.<br />

Heller’s essay was—and still <strong>is</strong>—one of the most valuable pieces of Western <strong>graphic</strong> <strong>design</strong> critic<strong>is</strong>m. Its<br />

value can be measured by the amount of d<strong>is</strong>cussion it caused which was symptomatic of a greater problem<br />

within <strong>graphic</strong> <strong>design</strong>: How does <strong>graphic</strong> <strong>design</strong> expand to accept that which <strong>is</strong> “other”? In 1993, the work<br />

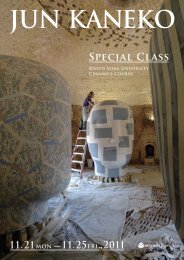

of <strong>design</strong>ers like Ed Fella, [Fig.6] Jeffery Keedy [Fig.7] and David Carson [Fig.8] was a div<strong>is</strong>ive wedge<br />

<strong>is</strong>sue. It was hardly “beautiful” by any conventional or traditional definition. It lacked signs of a mastered<br />

technique and it flaunted the proper conventions of accepted norms in typography. In fact, it looked<br />

“amateur<strong>is</strong>h” or vernacular. It looked un<strong>design</strong>ed. The fallout from “The cult of the ugly” was ultimately<br />

beneficial to <strong>graphic</strong> <strong>design</strong> because it uncovered the cracks in the veneer of establ<strong>is</strong>hed practice. Sadly<br />

however, the ensuing d<strong>is</strong>cussion here will attempt to show that d<strong>is</strong>course in <strong>graphic</strong> <strong>design</strong> has not changed<br />

all that much since Heller’s article was first publ<strong>is</strong>hed.<br />

<strong>Why</strong> ugly? The loss of technique<br />

One of the tools that made th<strong>is</strong> free-wheeling “amateur” aesthetic possible was the introduction of the<br />

Macintosh computer in 1984 and Adobe’s PostScript printing language in 1986, which made desktop<br />

publ<strong>is</strong>hing commonplace. The computer brought us <strong>such</strong> great moments as the “swirl filter” [Fig.9] and<br />

some might say it was all downhill from there. [Fig.10] The computer gave us the possibility to easily layer,<br />

d<strong>is</strong>tort, merge, mutate and essentially per<strong>for</strong>m a whole number of operations which were either previously<br />

impossible, or immensely time consuming. One could even produce new typefaces by simply using software<br />

to merge their contours, thus we could literally produce a Frankenstein typeface. [Fig.11]<br />

But perhaps most importantly, what the computer did do, was to d<strong>is</strong>seminate the tools of <strong>graphic</strong> <strong>design</strong><br />

among a general public: now everyone could be a <strong>graphic</strong> <strong>design</strong>er. But the d<strong>is</strong>semination of <strong>graphic</strong> <strong>design</strong><br />

as an open practice comes with a price. The “uninitiated” or amateur <strong>design</strong>er’s lack of knowledge about the<br />

strict rules of typography resulted in a loss of quality from a classical perspective. Th<strong>is</strong> democratization and<br />

resulting debasement of quality meant that there was little to d<strong>is</strong>tingu<strong>is</strong>h the work of trained, educated<br />

<strong>graphic</strong> <strong>design</strong>ers from that of a general public. The loosening of the rules of knowledge about what