Why is modernity such a burden for graphic design?

Why is modernity such a burden for graphic design?

Why is modernity such a burden for graphic design?

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

The rhetorics of rejection:<br />

<strong>Why</strong> <strong>is</strong> <strong>modernity</strong> <strong>such</strong> a <strong>burden</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>graphic</strong> <strong>design</strong>?<br />

David Cabianca<br />

Th<strong>is</strong> paper probes the rhetoric of <strong>graphic</strong> <strong>design</strong> critic<strong>is</strong>m in a context of rev<strong>is</strong>iting the accepted face of<br />

<strong>graphic</strong> <strong>design</strong> as an avant-garde practice. It attempts to examine the role of <strong>graphic</strong> <strong>design</strong> as a functioning<br />

part of culture, one which interprets and reflects society rather than an activity that <strong>is</strong> simply an instrument<br />

acting in the service of consumer capital. H<strong>is</strong>tories of <strong>graphic</strong> <strong>design</strong> tend to commence their narrative<br />

thread around the time that modern<strong>is</strong>m first emerged. 1 In order to reflect the rapid changes affecting society<br />

at the beginning of the 20th Century, the h<strong>is</strong>torical avant-garde sought to pursue a greater tie between the<br />

urbanization and industrialization of society and the v<strong>is</strong>ual materials produced by and communicated to that<br />

society. The h<strong>is</strong>torical avant-garde sought to create works that mirrored the newfound rationalization of life,<br />

works of “neue Sachlichkeit” or “new sobriety” which reflected the tenets of standardization, mechanization<br />

and industrialization. Work which was “objective” was considered rational. In th<strong>is</strong> vein, the terms “beauty,”<br />

“truth” and “neutrality” are both rhetorical devices which serve to prefigure an aesthetic outcome and<br />

gatekeepers which regulate the images that circulate within their d<strong>is</strong>course. Each term attempts to rehearse<br />

and anticipate the production of <strong>graphic</strong> <strong>design</strong> practice in the name of “unbiased communication.” In fact,<br />

the moment <strong>graphic</strong> <strong>design</strong> attempts to act within a critical framework, capital simply withdraws from its<br />

service and <strong>design</strong> <strong>is</strong> relegated to the dustbin.<br />

So how do we deal with <strong>modernity</strong>? What constitutes “the modern” and how do we come to understand it or<br />

interpret its significance? In an ef<strong>for</strong>t to identify what <strong>is</strong> “modern,” I turned to two individuals whose own<br />

writings were directly involved with the analys<strong>is</strong> and the interpretation of their respective turbulent times as<br />

observant critics of <strong>modernity</strong>, Charles Baudelaire and Walter Benjamin.<br />

In fact, Benjamin acknowledges Baudelaire as the intellectual template upon which he modeled h<strong>is</strong> own<br />

analyses of modern<strong>is</strong>t culture. Benjamin recognized that <strong>for</strong> Baudelaire, critic<strong>is</strong>m was not determined by a<br />

set structure of received notions handed down by the propriety of time. “Baudelaire placed the shock<br />

experience at the center of h<strong>is</strong> art<strong>is</strong>tic work… Shock <strong>is</strong> among those experiences that have assumed dec<strong>is</strong>ive<br />

importance <strong>for</strong> Baudelaire’s personality.” 2 Baudelaire rel<strong>is</strong>hed in <strong>modernity</strong>’s ability to generate<br />

“<strong>for</strong>eignness” or the shock of the new or unfamiliar. For Baudelaire, “‘[M]odernity’ mean[t] the ephemeral,<br />

the fugitive, and the contingent, the half of art whose other half <strong>is</strong> the eternal and the immutable... Th<strong>is</strong><br />

transitory, fugitive element, whose metamorphoses are so rapid, must on no account be desp<strong>is</strong>ed or<br />

d<strong>is</strong>pensed with.” 3 For Baudelaire, when something or some work captured h<strong>is</strong> attention in delight or<br />

revulsion, he would subsequently examine and analyze the why and where<strong>for</strong>e, until he was able to<br />

trans<strong>for</strong>m the initial shock or pleasure into knowledge. Baudelaire used the shock of the unfamiliar as a<br />

method to propel h<strong>is</strong> understanding of—and appreciation <strong>for</strong>—modern society. Benjamin was later to also<br />

theorize the value of shock in the modern metropol<strong>is</strong>. He recognized that the familiarity of accepted<br />

conventions <strong>is</strong> merely another <strong>for</strong>m of anesthesia, one which numbs the senses and the mind to the<br />

exigencies of the living world, “Com<strong>for</strong>t <strong>is</strong>olates… it brings those enjoying it closer to mechanization,” 4<br />

which <strong>is</strong> to say that com<strong>for</strong>t and familiarity deaden life’s experience to a mechan<strong>is</strong>tic, repetitive routine,<br />

while the new or the unfamiliar offers the mind the possibility to take note of life’s richness anew.<br />

Rather than examine emerging developments in 19th century society from the values of “high” art or<br />

culture, Baudelaire was fascinated by what was otherw<strong>is</strong>e marginalized—what society d<strong>is</strong>carded, what it<br />

otherw<strong>is</strong>e turned a blind eye towards, and what it criticized as being an aberration. Baudelaire’s study of<br />

painter Constantin Guys, “The painter of modern life,” <strong>is</strong> an analys<strong>is</strong> of the subjects Guys chose to paint.<br />

[Fig.1] Baudelaire wrote about the base or fringe components of society: prostitutes, cosmetics, fashion,<br />

carriages and the le<strong>is</strong>ure class—yet these figures were beginning to <strong>for</strong>m a substantial if not dominant<br />

portion of the culture of 19th-century Par<strong>is</strong>. [Fig.2] In the 19th Century, these marginalized elements of<br />

society were considered degenerates and delinquents, people and activities that were otherw<strong>is</strong>e symptoms of<br />

an unschooled lower class ignorant in the tastes of the dominant culture. By turning h<strong>is</strong> gaze to the<br />

periphery, Baudelaire was able to “see” contemporary society around him rather than long <strong>for</strong> a culture with<br />

which he was familiar and which was rapidly being replaced with one which was alien. It <strong>is</strong> to Baudelaire’s

credit that he was able to recognize and appreciate the emergence of a middle class and the values of its<br />

popular taste as being the driving <strong>for</strong>ce behind <strong>modernity</strong>.<br />

Modern now: The value of shock<br />

So what constitutes “shock” in 2008? Where do we turn to locate the marginal and d<strong>is</strong>enfranch<strong>is</strong>ed in<br />

contemporary <strong>graphic</strong> <strong>design</strong>? One possible option <strong>is</strong> to turn to critic<strong>is</strong>m itself. Similar to Baudelaire’s study<br />

of those figures derided by 19th century society, it <strong>is</strong> possible to look at contemporary critic<strong>is</strong>m itself to<br />

determine what our culture chooses to d<strong>is</strong>m<strong>is</strong>s now as a possible signifier of <strong>modernity</strong> today.<br />

One of the most infamous 20th-century critiques of <strong>graphic</strong> <strong>design</strong> was publ<strong>is</strong>hed in 1993 by writer and<br />

critic Steven Heller. In contrast to Baudelaire’s adventurous attitude toward the exigencies of <strong>modernity</strong>,<br />

Heller’s article, “The cult of the ugly,” lambasted the <strong>for</strong>ms of <strong>graphic</strong> <strong>design</strong> among an emerging<br />

generation as “ugly.” Originally publ<strong>is</strong>hed in the Brit<strong>is</strong>h <strong>graphic</strong> <strong>design</strong> magazine, Eye, Heller’s critic<strong>is</strong>m<br />

was precipitated by h<strong>is</strong> receiving a eight-page pamphlet produced by the graduate students of Cranbrook<br />

Academy of Art. [Fig.3] In writing about th<strong>is</strong> pamphlet, which Heller decidedly describes as ugly, he states,<br />

“Ask [what beauty <strong>is</strong>] to the Cranbrook Academy of Art students who created the ad hoc desktop<br />

publication, Output, and judge by the evidence that they might answer that beauty <strong>is</strong> chaos born of found<br />

letters layered on top of random patterns and shapes. [Fig.4] Those who value functional simplicity would<br />

argue that the Cranbrook students’ publication, like a toad’s warts, <strong>is</strong> ugly.” 5 [Fig.5] And Heller continues<br />

h<strong>is</strong> tirade, “Output <strong>is</strong> eight unbound pages of blips, type fragments, random words, and other <strong>graphic</strong><br />

minutiae purposely given the serendipitous look of a printer’s make-ready… Output could be considered a<br />

prime example of ugliness in the service of fashionable experimentation.” “As personal research, indeed as<br />

personal art, it can be justified, but as a model <strong>for</strong> commercial practice, th<strong>is</strong> kind of ugliness <strong>is</strong> a dead end.” 6<br />

But if Heller’s critique <strong>is</strong> held to the methods set <strong>for</strong>th by Baudelaire, clearly the shock value of the work<br />

Heller w<strong>is</strong>hes to d<strong>is</strong>m<strong>is</strong>s as “irrelevant,” suggests that th<strong>is</strong> work <strong>is</strong> modern.<br />

Heller’s essay was—and still <strong>is</strong>—one of the most valuable pieces of Western <strong>graphic</strong> <strong>design</strong> critic<strong>is</strong>m. Its<br />

value can be measured by the amount of d<strong>is</strong>cussion it caused which was symptomatic of a greater problem<br />

within <strong>graphic</strong> <strong>design</strong>: How does <strong>graphic</strong> <strong>design</strong> expand to accept that which <strong>is</strong> “other”? In 1993, the work<br />

of <strong>design</strong>ers like Ed Fella, [Fig.6] Jeffery Keedy [Fig.7] and David Carson [Fig.8] was a div<strong>is</strong>ive wedge<br />

<strong>is</strong>sue. It was hardly “beautiful” by any conventional or traditional definition. It lacked signs of a mastered<br />

technique and it flaunted the proper conventions of accepted norms in typography. In fact, it looked<br />

“amateur<strong>is</strong>h” or vernacular. It looked un<strong>design</strong>ed. The fallout from “The cult of the ugly” was ultimately<br />

beneficial to <strong>graphic</strong> <strong>design</strong> because it uncovered the cracks in the veneer of establ<strong>is</strong>hed practice. Sadly<br />

however, the ensuing d<strong>is</strong>cussion here will attempt to show that d<strong>is</strong>course in <strong>graphic</strong> <strong>design</strong> has not changed<br />

all that much since Heller’s article was first publ<strong>is</strong>hed.<br />

<strong>Why</strong> ugly? The loss of technique<br />

One of the tools that made th<strong>is</strong> free-wheeling “amateur” aesthetic possible was the introduction of the<br />

Macintosh computer in 1984 and Adobe’s PostScript printing language in 1986, which made desktop<br />

publ<strong>is</strong>hing commonplace. The computer brought us <strong>such</strong> great moments as the “swirl filter” [Fig.9] and<br />

some might say it was all downhill from there. [Fig.10] The computer gave us the possibility to easily layer,<br />

d<strong>is</strong>tort, merge, mutate and essentially per<strong>for</strong>m a whole number of operations which were either previously<br />

impossible, or immensely time consuming. One could even produce new typefaces by simply using software<br />

to merge their contours, thus we could literally produce a Frankenstein typeface. [Fig.11]<br />

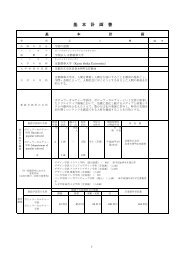

But perhaps most importantly, what the computer did do, was to d<strong>is</strong>seminate the tools of <strong>graphic</strong> <strong>design</strong><br />

among a general public: now everyone could be a <strong>graphic</strong> <strong>design</strong>er. But the d<strong>is</strong>semination of <strong>graphic</strong> <strong>design</strong><br />

as an open practice comes with a price. The “uninitiated” or amateur <strong>design</strong>er’s lack of knowledge about the<br />

strict rules of typography resulted in a loss of quality from a classical perspective. Th<strong>is</strong> democratization and<br />

resulting debasement of quality meant that there was little to d<strong>is</strong>tingu<strong>is</strong>h the work of trained, educated<br />

<strong>graphic</strong> <strong>design</strong>ers from that of a general public. The loosening of the rules of knowledge about what

constitutes the “proper” and what does not, would lead <strong>design</strong>ers to create eccentric advert<strong>is</strong>ements [Fig.12]<br />

with tattooed, Hare Kr<strong>is</strong>hna nud<strong>is</strong>ts that use six different typefaces at the same time.<br />

But the accusation that <strong>graphic</strong> <strong>design</strong> which <strong>is</strong> excessive, decorative and clumsy <strong>is</strong> there<strong>for</strong>e “amateur” or<br />

“un<strong>design</strong>ed” relative to the refined modern<strong>is</strong>t <strong>design</strong>s of Josef Müller-Brockmann, Massimo Vignelli, or<br />

Wim Crouwel [Fig.13] <strong>is</strong> not a label which <strong>is</strong> so clearly applied. In 1922, William Add<strong>is</strong>on Dwiggins coined<br />

the term “<strong>graphic</strong> <strong>design</strong>” to d<strong>is</strong>tingu<strong>is</strong>h h<strong>is</strong> profession from the practice of fine art and the vocational<br />

service of mere typesetting. But while Dwiggins recognized that as a <strong>graphic</strong> <strong>design</strong>er, h<strong>is</strong> work was more<br />

intellectually complex than that of a commercial typesetter, he also d<strong>is</strong>tanced himself from what he saw as<br />

the non-American, imported aesthetic of “those Bauhaus boys” as he liked to call them, which included the<br />

likes of Paul Rand and Herbert Bayer. In contrast to the European modern<strong>is</strong>ts, Dwiggins’ work recalled the<br />

decorative, irregular and painterly lettering of the Arts and Crafts or Art Nouveau periods [Fig.14]:<br />

Dwiggins’ work appeared old-fashioned and personal. H<strong>is</strong> typography was ornamented, highly idiosyncratic<br />

and irrational. In contrast, the spare, rational<strong>is</strong>t work influenced by the Bauhaus was new—and in an<br />

American context—it was shocking. [Fig.15] Dwiggins’ work appealed to the decorative impulse of the<br />

general public, which put it in an antagon<strong>is</strong>tic position relative to the spare, minimal<strong>is</strong>t work of the<br />

commonly accepted <strong>for</strong>ms of modern<strong>is</strong>m. So while Dwiggins’ work was mannered and some might say a<br />

throwback because of its roots in Arts and Crafts <strong>design</strong>, it was hardly “shocking,” and in th<strong>is</strong> context,<br />

hardly “modern.” But nearly 70 years later, by the time that Steven Heller wrote “The cult of the ugly” and<br />

criticized <strong>design</strong>s which were being non-conventional and excessive, the d<strong>is</strong>cipline’s acceptance of what<br />

was expected in <strong>graphic</strong> <strong>design</strong> had reversed: in a context of well establ<strong>is</strong>hed minimal corporate <strong>graphic</strong><br />

<strong>design</strong> of the 1990s, the mannered experiments described by Heller were shocking.<br />

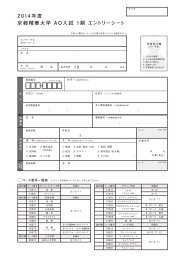

It’s 1993 all over again: The new ugly <strong>graphic</strong> <strong>design</strong><br />

One would think by now that th<strong>is</strong> mannered and clumsy work would be fully embraced by <strong>graphic</strong> <strong>design</strong> as<br />

part of the conventions of practice, and hardly worth critic<strong>is</strong>m, but th<strong>is</strong> <strong>is</strong> apparently not the case. In 2007<br />

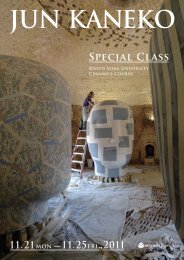

and in an editorial column publ<strong>is</strong>hed on the <strong>design</strong> blog Design Observer, [Fig.16] contributing writer<br />

Dimitri Siegel has th<strong>is</strong> to say about the work of Elliott Earls, current Chair of the 2D Design Department at<br />

Cranbrook Academy of Art: [Fig.17] “The problem with the authorship model <strong>is</strong> that it replaces a tangible<br />

engaged client with a vague notion of a market, passively waiting to consume (or more likely ignore) the<br />

self-generated work of the <strong>design</strong>er (as author).... [T]he quest <strong>for</strong> authorship may jeopardize the economic<br />

and cultural free agency that defines the field.” 7 Which was followed by an anonymous post, “[G]arbage.<br />

It’s just not <strong>design</strong>.” 8 [Fig.18] Forgive me <strong>for</strong> dredging up some old h<strong>is</strong>tory, but many of the comments echo<br />

some of what was written by Steven Heller in “The cult of the ugly.” In fact, in a column publ<strong>is</strong>hed January<br />

30, 2008, Steven Heller laments the re-emergence of hand typography or “amateur” <strong>graphic</strong> <strong>design</strong> as yet<br />

again, a “dead end” in development:<br />

Handwritten, expressively drawn lettering… <strong>is</strong> perilously close to the veritable precipice, and on the<br />

proverbial edge of becoming an overused <strong>graphic</strong> <strong>design</strong> cliché. While style invariably breeds<br />

redundancy, th<strong>is</strong> hand-wrought style <strong>is</strong> so easily (and pleasurably) used in place of rigidly<br />

conventional <strong>for</strong>m, and it <strong>is</strong> found in so many print and internet venues that it may become an old<br />

hand-me-down too soon.” 9<br />

The comments of both Siegel and Heller d<strong>is</strong>play a desire to maintain d<strong>is</strong>ciplinary limits based on a nostalgia<br />

<strong>for</strong> familiar v<strong>is</strong>ual tenets, a nostalgia <strong>for</strong> a loss of status. It <strong>is</strong> hardly <strong>for</strong>ward thinking to <strong>for</strong>ecast the success<br />

or failure of a <strong>for</strong>m of v<strong>is</strong>ual expression. Rather than attempt to impede the progression of a v<strong>is</strong>ual <strong>for</strong>m, the<br />

value of <strong>such</strong> work could be found in highlighting how the work makes present the character of an age: “The<br />

pleasure which we derive from the representation of the present <strong>is</strong> due not only to the beauty with which it<br />

can be invested, but also to its essential quality of being present.” 10<br />

The anti-mastery of today’s handwork comes with a difference: [Fig.19] Hand typography <strong>is</strong> no longer<br />

necessary. [Fig.20] The computer made hand typography and hand <strong>design</strong> superfluous. By stripping hand<br />

typography of its necessity—nowadays, type comes from a pulldown menu—the choice to do typography or<br />

lettering by hand <strong>is</strong> a conscious polemical statement. [Fig.21] The partners of Par<strong>is</strong>-based Vier5, Achim<br />

Reichert and Marco Fiedler write,

We no longer build like we did 30 years ago, we don’t dress in the same fashion as 30 years ago, so<br />

why should we still write like we did 30 years ago? [Fig.22] Th<strong>is</strong> <strong>is</strong> the starting point of a new<br />

generation of typography, guided by the idea of shaping the future creatively and meaningfully. The<br />

objective <strong>is</strong> to create a new <strong>for</strong>m of typography that aims at replacing outdated standards which turn<br />

out to be more and more anachron<strong>is</strong>tic and useless, with new signs that are valid and respond to<br />

contemporary structures. 11<br />

Vier5 are in fact rather optim<strong>is</strong>tic about <strong>graphic</strong> <strong>design</strong>. They do not see their work as a regression or as an<br />

anachron<strong>is</strong>m: [Fig.23] “Working with typography <strong>is</strong> also a scientific research work, research in cultural as<br />

well as sociological areas. Developing typo<strong>graphic</strong>al structures <strong>is</strong> close to exploring contemporary social<br />

and cultural trends and influences.” 12 In fact, surpr<strong>is</strong>ingly, many of the clients of the new ugly are leading<br />

cultural and fashion institutions. Firms like Vier5, MM Par<strong>is</strong> and Antoine+Manuel [Fig.24] l<strong>is</strong>t among their<br />

clients the Centre <strong>for</strong> Contemporary Art in Bretigny. the Collection Lambert Contemporary Art Museum in<br />

Avignon, [Fig.25] Lorient Théâtre in Par<strong>is</strong>, [Fig.26] and fashion <strong>design</strong>ers Chr<strong>is</strong>tian Lacroix, [Fig.27]<br />

[Fig.28] and Calvin Klein. [Fig.29] Cultural institutions and fashion houses are perhaps among the most<br />

attuned to the social and cultural mores of contemporary society. [Fig.30] Judged by the standards of<br />

classical typography, the “poor technique” of contemporary hand typography would indicate that the there <strong>is</strong><br />

some other intent present than an urge to fulfill the conventions of accepted beauty (yet again). [Fig.31] Yet<br />

whatever that intent might be, th<strong>is</strong> work still shocks us, and <strong>is</strong>, ultimately, modern. [Fig.32]<br />

__<br />

David Cabianca, Ass<strong>is</strong>tant Professor<br />

York University<br />

Department of Design<br />

4008 TEL Building<br />

4700 Keele Street<br />

Toronto ON, M3J 1P3<br />

Canada<br />

e cabianca@yorku.ca<br />

t 416.736.2100 x44024<br />

f 416.736.5450<br />

w <strong>design</strong>.yorku.ca<br />

1 For the purposes of d<strong>is</strong>cussion here, I am pinning my definition of modern<strong>is</strong>m to the emergence of the<br />

h<strong>is</strong>torical avant-garde.<br />

2 Walter Benjamin, “On some motifs in Baudelaire,” Illuminations (New York: Schocken Books, 1969)<br />

p.163–164.<br />

3 Charles Baudelaire, “The painter of modern life,” The painter of modern life and other essays (New York:<br />

Da Capo, 1964) p.13.<br />

4 Benjamin, p.174.<br />

5 Steven Heller, “The cult of the ugly,” Eye no.9 vol.3 1993: 52–59.<br />

6 Ibid.<br />

7 Dimitri Siegel, “Designers and Dilettantes,” Design Observer Blog, September 18, 2007,<br />

http://www.<strong>design</strong>observer.com/archives/027986.html (accessed March 11, 2008).<br />

8 Anonymous, comment on “Designers and Dilettantes,” Design Observer Blog, comment posted September<br />

22, 2007, http://www.<strong>design</strong>observer.com/archives/027986.html (accessed March 11, 2008).<br />

9 Steven Heller, “The hand <strong>is</strong> back,” A Brief Message Blog, January 30, 2008,<br />

http://abriefmessage.com/2008/01/30/heller/ (accessed March 21, 2008).<br />

10 Baudelaire, p.1.<br />

11 Achim Reichert and Marco Fiedler, “Look <strong>for</strong>ward, never back: A view on modern typography,” New<br />

Typo<strong>graphic</strong>s (Tokyo: Pie Books, 2005), np.<br />

12 Ibid.