SO 2010 - webapps8 - Minnesota Department of Natural Resources

SO 2010 - webapps8 - Minnesota Department of Natural Resources

SO 2010 - webapps8 - Minnesota Department of Natural Resources

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

"EVERYBODY KNOWS .. . THAT THE AUTUMN LANDSCAPE IN THE NORTH WOODS IS<br />

THE LAND, PLUS A RED MAPLE, PLUS A RUFFED GROUSE. IN TERMS OF CONVENTIONAL<br />

PHYSICS, THE GROUSE REPRESENTS ONLY A MILLIONTH OF EITHER THE MASS OR THE<br />

ENERGY OF AN ACRE. YET SUBTRACT THE GROUSE AND THE WHOLE THING IS DEAD:'<br />

-ALDO LEOPOLD<br />

FEATURES<br />

10 BLUFFLAND BUCKS<br />

New hunting regulations in southeastern <strong>Minnesota</strong> could make the region's wooded hills<br />

a haven for big bucks. By Jason Abraham<br />

16 AFTER THE HARVEST<br />

Harvesting wild rice is only the first step in getting this native grain from the<br />

rna rsh to the table . By Annette Dray Drewes<br />

24 UPS AND DOWNS IN THE GROUSE WOODS<br />

The ruffed grouse population cycle works in mysterious ways. By Michael Furtman<br />

30 GATEWAY TO LAKE OF THE WOODS<br />

Zippel Bay State Park in northwestern <strong>Minnesota</strong> <strong>of</strong>fers access to the vast waters <strong>of</strong><br />

Lake <strong>of</strong> the Woods as well as sandy beaches to simply enjoy the view. By David Mather<br />

The number <strong>of</strong> processors who<br />

parch, thresh, and winnow wild<br />

rice has declined. Fortunately,<br />

people like Dale Greene Sr. ( center)<br />

are passing on the art. See<br />

story on page 16.

MINNE<strong>SO</strong>TA CONSERVATION VOLUNTEER, SEPTEMBER-OCTOBER <strong>2010</strong><br />

VOLUME ]3, NUMBER 432<br />

www.mndnr.govjmagazine<br />

40 LEARN TO HUNT<br />

Young <strong>Natural</strong>ists go afield with experienced<br />

hunters in search <strong>of</strong> wild game. By Michael A. Kallok<br />

48 TAONow ..<br />

Using scientists' tools, students discover opportunities<br />

to improve wildlife habitat. By Kathleen Weflen<br />

DEPARTMENTS<br />

2 THIS ISSUE<br />

4 LETTERS<br />

6 NATURAL CURIOSITIES<br />

8 FIELD NOTES<br />

52 THANK YOU<br />

64 MINNE<strong>SO</strong>TA PROFILE<br />

• LOON TRACKING. Watch<br />

researchers capturing and<br />

outfitting loons with telemetry<br />

equipment in an effort to learn<br />

more about the migratory patterns<br />

<strong>of</strong> our state bird .<br />

Go to www.mndnr.govjmagazine<br />

for videos, photo slide shows,<br />

teachers guides, and links to<br />

other resources.<br />

<strong>Minnesota</strong> Conservation \.blunteer (uSPS 129880) is published<br />

bimonthly by t he <strong>Department</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Natural</strong><br />

<strong>Resources</strong>, 500 Lafayette Road, St. Paul, MN 55155-<br />

4046. Preferred periodicals postage paid in St. Paul,<br />

Minn., and additional <strong>of</strong>fices.<br />

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to <strong>Minnesota</strong><br />

Con servation Volunteer, Departme nt <strong>of</strong> <strong>Natural</strong><br />

Resou rces, 500 l afayette Road, St. Paul , MN<br />

55155-4046. Equal opportunity to programs <strong>of</strong><br />

the <strong>Department</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Resources</strong> is avai la ble<br />

to all individuals regardless <strong>of</strong> race, color, national<br />

origin, sex, sexual orientation, age, or disability.<br />

Di scrim ination inquiries should be sent to DNR<br />

Affi rmative Action, 500 lafayette Road, St. Paul,<br />

MN 55155-4031, or the Equal Opportunity Office,<br />

<strong>Department</strong> <strong>of</strong> the Interior, Washington, DC 20240.<br />

For alternative formats, call651-259-5365.<br />

<strong>Minnesota</strong> Conservation Volunteer is sent free upon<br />

request and relies entirely on donations from its<br />

readers.<br />

® Printed on chlorine-free paper containing at least 10<br />

pe~tent post-

THIS ISSUE<br />

Dangerous Migration?<br />

MINNE<strong>SO</strong>TA's LOONS may soon be heading<br />

to the scene <strong>of</strong> a disaster. In October<br />

and November, thousands will migrate to<br />

coastal waters along the Gulf <strong>of</strong> Mexico.<br />

Between April 20 and July 15, an estimated<br />

200 million gallons <strong>of</strong> oil poured from a<br />

broken well deep in Gulf waters. The spillage<br />

has stopped and oil that rose to the surface<br />

has dissipated. Yet water birds-particularly<br />

deep-diving common loons-risk contact<br />

with oil and chemical dispersants that persist<br />

below the surface, says DNR Nongame<br />

Wildlife Program supervisor Carrol Henderson.<br />

So do other <strong>Minnesota</strong> birds wintering<br />

along the Gulf, including ospreys, American<br />

white pelicans, spotted sandpipers, western<br />

grebes, lesser scaup, and redheads.<br />

<strong>Minnesota</strong>'s migratory bird populations<br />

bring the oceanic catastrophe close to home<br />

and remind us that natural systems connect in<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>ound and sometimes unfathomable ways.<br />

When disaster strikes, concerned citizens<br />

have an immediate urge to help. For<br />

example, more than 13,000 people signed<br />

up to help the National Audubon Society<br />

in its coastal bird rescue work. And when a<br />

crisis appears to have passed, most Americans<br />

want to quickly move on. In this case<br />

<strong>of</strong> environmental contamination, we have<br />

reason to stand watch.<br />

"We have never had a spill <strong>of</strong> this magnitude<br />

in the deep ocean;' said oceanography pr<strong>of</strong>essor<br />

Ian MacDonald in a story in The New York<br />

Times. "These things reverberate through the<br />

ecosystem. It is an ecological echo chamber,<br />

and I think we'll be hearing the echoes <strong>of</strong> this,<br />

ecologically; for the rest <strong>of</strong> my life~'<br />

Henderson suggests some immediate<br />

actions <strong>Minnesota</strong>ns can take to help wildlife<br />

in the long term. One simple start: Buy federal<br />

duck stamps online or at your local post <strong>of</strong>fice.<br />

This year the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service<br />

2<br />

MINNE<strong>SO</strong>TA CONSERVATION VOLUNTEER

is <strong>of</strong>fering a $25 special edition to raise funds for purchasing<br />

wetlands to add to Gulf Coast national wildlife refuges.<br />

The DNR's long-term monitoring <strong>of</strong> the state's loon<br />

populations could prove vital to understanding the oil disaster's<br />

impact on loons. Volunteers in the <strong>Minnesota</strong> Loon<br />

Monitoring Program annually check 600 lakes. <strong>Minnesota</strong><br />

Loon Watcher Survey also relies on volunteers. And everyone<br />

can contribute to the DNR Nongame Wildlife Program,<br />

www. mndnr.gov/eco/nongame.<br />

As we continue to monitor birds on both their wintering and<br />

breeding grounds, we might keep in mind the slowly realized<br />

disaster <strong>of</strong> DDT use in the 1950s and '60s. The grave effects <strong>of</strong><br />

DDT on wildlife took a long time to recognize. The painstaking<br />

research and courageous reporting <strong>of</strong> Rachel Carson, a marine<br />

biologist and writer with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service,<br />

brought the problem <strong>of</strong> ubiquitous chemical contamination<br />

to the nation's attention in her 1962 bestseller, Silent Spring.<br />

"The history <strong>of</strong> life on earth has been a history <strong>of</strong> interaction<br />

between living things and their surroundings;' Carson<br />

wrote. She reported case after case <strong>of</strong> people failing to appreciate<br />

the complexity <strong>of</strong> those interactions. Consider one<br />

example: She told <strong>of</strong> attempts to control gnats on a popular<br />

fishing lake in northern California by spraying DDD, a close<br />

relative <strong>of</strong> DDT. "No trace <strong>of</strong> DDD could be found in the<br />

water shortly after the last application <strong>of</strong> the chemical. But the<br />

poison had not really left the lake; it had merely gone into the<br />

fabric <strong>of</strong> the life the lake supports~' Nearly two years after the<br />

spraying ended, DDD persisted in plankton, apparently passing<br />

from one generation to the next. Thus, the poison entered<br />

the food chain, accumulating in the flesh <strong>of</strong> frogs, fish, and<br />

birds to concentrations many times the original in the water.<br />

Oil does not move up the food chain as some compounds<br />

do. But the ripple effects <strong>of</strong> oil and nearly 2 million gallons <strong>of</strong><br />

dispersants underwater in the Gulf have yet to be discovered.<br />

What will happen to the continent's wildlife in the wake<br />

<strong>of</strong> this contamination? As Henderson says, no one wants to<br />

imagine <strong>Minnesota</strong> lakes absent the wild calls <strong>of</strong> common<br />

loons. That would be a silent spring.<br />

Kathleen Weflen, editor, kathleen.weflen@state.mn.us<br />

For more on birds and oil in the Gulf <strong>of</strong> Mexico, turn to Field Notes on page 8.<br />

SEPTEMBER-OCTOBER <strong>2010</strong><br />

MINNE<strong>SO</strong>TA<br />

CONSERVATION<br />

VOLUNTEER<br />

A reader-supported publication encouraging<br />

conservation and careful use <strong>of</strong> <strong>Minnesota</strong>'s<br />

natural reso urces.<br />

Communications Director Colleen Coyrw<br />

Editor in Ch ief<br />

Art Director<br />

Manag ing Editor<br />

Associate Editor<br />

Database Manager<br />

Circulation Manager<br />

M AGAZ INE STAFF<br />

Kathleen Weflen<br />

Lynn Phelps<br />

Gustave Axelson<br />

Michael A. Kallok<br />

Dovid).Lent<br />

Susan M. Ryan<br />

Subscriptions and donations<br />

888·646·6367<br />

Governor Tim Pawlerlty<br />

D E PARTMENT OF N ATURAL R E<strong>SO</strong>UR CES<br />

~~m<br />

DEPARTIENT OF<br />

NAMAl"""""'<br />

W\Vw.mndnr.gov<br />

Our mission is to work with citizens to<br />

conserve and manage the state's natural<br />

resources, to provide outdoor recreation<br />

opportunities, and to provide for commercial<br />

uses <strong>of</strong> natural resources in a way that<br />

creates a sustainable quality <strong>of</strong> life.<br />

Commissioner Mark Holsten<br />

Deputy<br />

Commissioner<br />

Laurie Martinson<br />

Assistant Bob Meier, Larry Kramka<br />

Commissioners<br />

DIVIS ION DIRECTORS<br />

Steve Hirsch, Ecological <strong>Resources</strong><br />

Jim Konrad, Enforcement<br />

Dave Schad, Fish and Wildlife<br />

Dave Epperly, Forestry<br />

Marty Vadis, Lands and Minerals<br />

Courtland Nelson, Parks and Trails<br />

Kent Lokkesmoe, Waters<br />

R EGIONAL DIRECTORS<br />

Mike Carroll, Bemidji<br />

Craig Engwall, Grand Rapids<br />

joe Kurcinka, St. Paul<br />

Mark Matuska, New Ulm

I LETTERS I<br />

"I WAS GIVEN CLEAR INSTRUCTION TO PASS ON TO THOSE RESPONSIBLE FOR THE<br />

VOLUNTEER THEIR APPRECIATION."<br />

Brad Bolduan<br />

Could We Lose? How to Help?<br />

Is there a <strong>Minnesota</strong> connection to the oil spill?<br />

Could we lose some <strong>of</strong> our magnificent birds<br />

like the loon or blue heron as they migrate<br />

south through the oil spill this fall? Is there any<br />

<strong>Minnesota</strong> volunteer group working on this,<br />

and how do we help them before it is too late?<br />

Garry Kassube, Eagan<br />

See This Issue on page 2 and Field Notes on 8.<br />

Arrowheads at Fort Snelling<br />

I found "Deeper Into History" (July-Aug.<br />

<strong>2010</strong>), describing artifacts found during<br />

archaeological digs at Fort Ridgely, very interesting.<br />

I noticed the similarity <strong>of</strong> arrowheads<br />

found at Fort Ridgely to some I have. My<br />

father was the post photographer at Fort<br />

Snelling from about 1925 to 1935. During<br />

that period the sewer system was updated,<br />

which required substantial excavation. Many<br />

arrowheads were found at that time, and one<br />

<strong>of</strong> the workers gave arrowheads to my father.<br />

Charles Gustafson, Minneapolis<br />

Author David Mather responds (after seeing<br />

Gustafsorls artifacts): These stone tools are significant<br />

because the location where they were found<br />

is known. One spear point may be around 2,000<br />

years old-from a time <strong>of</strong> extensive American<br />

Indian trade across much <strong>of</strong> North America,<br />

which brought the traditions <strong>of</strong> mound building<br />

and pottery to <strong>Minnesota</strong>. The other two pieces<br />

may have been knives or earlier stages <strong>of</strong> making<br />

points. Anyone with artifacts should store<br />

them with a written note <strong>of</strong> where they came<br />

from. Without that record, an important artifact<br />

becomes just a curiosity<br />

Role <strong>of</strong> U.S. Agriculture<br />

In the May-June <strong>2010</strong> issue, you quoted<br />

Jonathan Foley in the This Issue page saying,<br />

"If you're concerned with preserving<br />

biodiversity and protecting ecosystems, focus<br />

on expanding agriculture, not suburbia:'<br />

Although his comment was meant to be<br />

worldwide, I take issue with it.<br />

Developed land includes roads, railroads,<br />

and built-up areas (residential, industrial,<br />

commercial). Development isolates tracts <strong>of</strong><br />

farmland, which degrades wildlife habitat and<br />

makes agricultural production inefficient.<br />

The loss <strong>of</strong> U.S. agricultural land to<br />

development concerns groups such as the<br />

American Farmland Trust. AFT points out<br />

that 4 million acres <strong>of</strong> active farmland and<br />

land formerly enrolled in the Conservation<br />

Reserve Program were converted to developed<br />

uses between 2002 and 2007.<br />

Keith Marty, Chokio<br />

Tell people how important agriculture is to<br />

this state, and how important it is for agriculture<br />

to coexist with our natural resources programs.<br />

You can't have one without the other.<br />

Doug Miller, Sauk Centre<br />

4<br />

MINNE<strong>SO</strong>TA CONSERVATION VOLUNTEER

Good Review at Reunion<br />

I was at a family reunion last week when some distant relatives<br />

fonnd out I worked for the DNR. I was given dear instruction to<br />

pass on to those responsible for the Volunteer their appreciation.<br />

They all had numerous nice things to say about our magazine.<br />

Brad Bolduan, Windom<br />

Trout in Whitewater, Walleye in Voyageurs<br />

I particularly enjoyed the article on the Whitewater River<br />

("Fishing After the Flood;' July-Aug. <strong>2010</strong>) and the state<br />

park there. I was born in 1930 and grew up in Lewiston. We<br />

picnicked there, and I remember swimming in the Whitewater<br />

River. My father fished for trout in the Whitewater.<br />

My father grew up at Forestville, and his old home became<br />

staff housing for [Forestville state] park personnel. There was<br />

no rnnning water in the house but a wonderful spring about<br />

two blocks into the woods. Wash water was collected from the<br />

ro<strong>of</strong> in a tank and pumped for laundry.<br />

I now live at the edge <strong>of</strong>Voyageurs National Park. It is the<br />

place Dad spent a week every summer fishing for walleye.<br />

He also hunted deer on the Kabetogama Peninsula, when<br />

hunting was allowed before the park was established. I have<br />

lived here year-round now for 22 years.<br />

Mary Satterlee Kolner, Orr<br />

Interactive Birdsong<br />

[The MCV online interactive<br />

birdsong graphic is an]excellent<br />

tool! I will return to this <strong>of</strong>ten. I<br />

hope you will add more birds.<br />

Gary Horn, Maplewood<br />

See and hear the birds at www.<br />

mndnr.gov/magazine.<br />

CONTRIBUTORS<br />

Deer hunting is just one excuse that<br />

DNR furbearerjseason setting specialist,<br />

jason Abraham, page 10, uses to<br />

spend time walking the bluffs along the<br />

Mississippi River.<br />

Annette Dray Drewes, page 16, is<br />

executive director <strong>of</strong> a wild rice conservation<br />

organization called <strong>SO</strong>RA. She<br />

wanders the north country come late<br />

August, following the wild rice harvest.<br />

Miigwech, she says, to Dale, Martin,<br />

and Sunfish for sharing.<br />

Michael Furtman, page 24, was taught<br />

by his father to hunt ruffed grouse 35 years<br />

ago, when they were still known by the colloquial<br />

name"partridge:'Whatevertheyare<br />

called, he misses more <strong>of</strong> them than he hits.<br />

David Mather, page 30, is a writer and<br />

archaeologist from St. Paul. He dreams<br />

nightly <strong>of</strong> Lake <strong>of</strong> the Woods walleye, ever<br />

since his first taste <strong>of</strong> a Zippel Bay shore<br />

lunch. Mather is determined to visit Fort<br />

St. Charles, at the top <strong>of</strong> the Northwest<br />

Angle, and head farther north from there.<br />

Associate editor Michael A. Kallok,<br />

page 40, is thankful for the mentors who<br />

kindled his appreciation for the outdoors.<br />

Editor in chief Kathleen Weflen, page<br />

48, thought Tao was an ancient pathway<br />

to the true nature <strong>of</strong> the world. Then she<br />

learned about TAO, a new curriculum<br />

for children to learn about wildlife and<br />

habitat. Seeing TAO in action, she realized<br />

that TAO is indeed a pathway to nature.<br />

We welcome your comments. We'll edit letters for accuracy,<br />

style, and length. Send your letter and daytime phone number to<br />

Letters, MCV, 500 Lafayette Road, St. Paul, MN 55155-4046.<br />

E-mail: lettertoeditor.mcv@state.mn.us<br />

SEPTEMBER-OCTOBER <strong>2010</strong><br />

DN R INFORMATION CENTER<br />

www.mndnr.gov<br />

651-296-6157<br />

Toll-free 888-646-6367<br />

TTY (hearing impaired) 651-296-5484<br />

TTY 800-657-3929<br />

Volunteer Programs 651-259-5249<br />

STATE PARKS RESERVATIONS<br />

866-857-2757, TTY 866-672-2757<br />

www.stayatmnparks.com

I NATURAL CURIOSITIES<br />

ABUNDANT EGGS I BIRCH STROBILE$ I DEAD FISH I NATIVE LAMPREYS I PRAIRIE SKINKS<br />

SUNNING PIKE I RESISTANT ELMS<br />

trees, but are narrower. What are these objects?<br />

Dan Wicht, Fridley<br />

The conelike objects on birch branches are<br />

called strobiles. Birch flowers turn into strobiles<br />

as the seeds form. The brown scales <strong>of</strong><br />

the strobile contain the seeds. Often the seeds<br />

drop in winter, and you may have seen them<br />

against new snow. They look like flat, round<br />

dots with wings.<br />

My kids and I were cleaning out our wood duck houses<br />

in late winter, and one house had 21 unhatched<br />

eggs. Should we check the house in the spring and<br />

remove some eggs if there is a large number?<br />

Rex Ewert, Marine on St. Croix<br />

It is not unusual to find wood duck houses with<br />

a large number <strong>of</strong> unhatched eggs, says DNR<br />

wetland wildlife program leader Ray Norrgard.<br />

It happens when more than one hen is laying<br />

eggs in the same house or natural cavity and is<br />

referred to as dump nesting. As long as a hen<br />

is tending to the nest and is able to turn the eggs<br />

while incubating, all the eggs have a chance to<br />

hatch. When cleaning the nest box between<br />

nesting seasons, dispose <strong>of</strong> unhatched eggs.<br />

Every fall after the leaves drop, I see conelike<br />

objects hanging from the branches <strong>of</strong> birch trees.<br />

They resemble pollen-bearing cones on coniferous<br />

The last few days at the lake I live on in central<br />

<strong>Minnesota</strong>, my daughter, son-in-law, and I buried<br />

at least 100 dead crappies. What would kill that<br />

many fish at one time?<br />

Sandee Jones, Hillman<br />

The fish likely died from a bacterial infection<br />

called columnaris, according to DNR aquatic<br />

education specialist Roland Sigurdson. The bacterium<br />

is around all the time but <strong>of</strong>ten explodes<br />

when water temperature rises into the 70s and<br />

fish are spawning. Spawningfish such as crappie<br />

are more susceptible to infection because they<br />

are stressed from not feeding while building<br />

nests and defending territories.<br />

My son and I were fishing on the Snake River near<br />

Mora on Memorial Day weekend. My son caught a<br />

decent 15-inch bass, and when I landed the fish, I<br />

was aghast to see a lamprey hanging on the back<br />

6<br />

MINNE<strong>SO</strong>TA CONSERVATION VOLUNTEER

<strong>of</strong> the fish. Where do these lampreys come from?<br />

Bruce Miller, Mound<br />

Along with the fish you likely landed a chestnutsided<br />

lamprey, says DNR aquatic education<br />

specialist Roland Sigurdson. <strong>Minnesota</strong> has five<br />

native lamprey species. Unlike the nonnative sea<br />

lamprey, which has invaded Lake Superior and<br />

its tributaries, <strong>Minnesota</strong>'s native lampreys are a<br />

natural part <strong>of</strong> lake and river ecosystems. They<br />

pose no threat to fish populations. To learn more<br />

go to mndnr.gov/minnaqua.<br />

<strong>of</strong> its head were above water, like it was coming<br />

up for air or looking at us. It swam like this with<br />

its head out <strong>of</strong> the water for a few seconds. What<br />

would cause a pike to do this?<br />

Jonah Gilbert, Arden Hills<br />

Large muskie or pike ''sun" themselves near the<br />

surface or in the shallows, says DNR aquatic<br />

education specialist Roland Sigurdson. As a<br />

cold-blooded organism, the fish might have been<br />

increasing its body temperature, thereby boosting<br />

its metabolism and speed-useful for an ambush<br />

predator. Or it might have been trying to finish<br />

swallowing a large prey fish or rid itself <strong>of</strong> parasites<br />

irritating its gill tissue.<br />

I saw a lizard in my building at work yesterday in<br />

Crosslake in Crow Wing County. Is this a common<br />

area for lizards? I found this very unusual.<br />

Chris Sands, Crosslake<br />

You probably saw a prairie skink, according to<br />

<strong>Minnesota</strong> County Biological Survey herpetologist<br />

Carol Hall. They are common in the<br />

grasslands <strong>of</strong> Crow Wing and Cass counties.<br />

Not so common inside buildings though!<br />

We were fishing from our canoe in Lake Johanna<br />

and saw something that looked like a fish head<br />

sticking out <strong>of</strong> the water a little ways away. It was<br />

a northern pike or muskie at least 30 inches long<br />

swimming at the surface. Its dorsal fin and most<br />

In the '7os we were all saddened as SummitAvenue<br />

lost its glorious elm trees and the rest <strong>of</strong> the state<br />

also suffered the plague <strong>of</strong> Dutch elm disease.<br />

Now I take heart whenever I travel back roads and<br />

occasionally come upon a lone soldier elm tree still<br />

standing. Are these single, isolated trees simply<br />

naturally occurring, disease-resistant trees, or is it<br />

just that they have been isolated?<br />

Dale Wolf, Wrenshall<br />

DNR botanist Welby Smith says some <strong>of</strong> the<br />

surviving elms may be resistant to the disease,<br />

but most have escaped by chance. The disease<br />

and the beetles that spread it are still present,<br />

and elms will continue to become infected and<br />

die. Resistant hybrid elms have been bred, but<br />

the true American elm that was so abundant<br />

in <strong>Minnesota</strong> forests will not return.<br />

Send your questions and daytime phone<br />

number to <strong>Natural</strong> Curiosities, MC\1, 500 Lafayette<br />

Road, St. Paul, MN 55155-4046. E-mail:<br />

natura l.cu riosities@state. m n. us<br />

SEPTEMBER-OCTOBER <strong>2010</strong><br />

7

fiELD NOTES<br />

~.....-____ ___.!<br />

Gulf Disaster and <strong>Minnesota</strong> Birds<br />

THE APRIL <strong>2010</strong> OIL SPILL in the Gulf <strong>of</strong><br />

Mexico happened about 1 ,200 miles away<br />

from <strong>Minnesota</strong>, but the fouled waters could<br />

harm the state's migratory birds. Our state bird,<br />

the common loon, and 12 species <strong>of</strong><strong>Minnesota</strong><br />

waterfowl winter along the Gulf Coast.<br />

"This is a tragedy, not only for the Gulf<br />

states, but [also for] the entire continent;' DNR<br />

wildlife biologist Rich Baker said.<br />

According to Ducks Unlimited, more than<br />

25 waterfowl species, including 13 million<br />

ducks, winter in the Gulf, mostly in Louisiana<br />

and Texas. The Gulf also hosts nearly half <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Minnesota</strong>'s estinlated 12,000 loons in winter.<br />

Even as the oil slick has dissipated on the<br />

water's surface, scientists say impacts from the<br />

spill could continue from oil and oil dispersants<br />

underwater and in the food chain. Loons<br />

remain at risk <strong>of</strong> oil exposure because they<br />

dive as deep as 200 feet to pursue prey in their<br />

wintering waters, said DNRNongame Wildlife<br />

Program supervisor Carrol Henderson.<br />

Juvenile loons are especially at risk because<br />

they stay in the Gulf for up to three years after<br />

their first migration south from <strong>Minnesota</strong>.<br />

The U.S. Geological Survey and the DNR<br />

implanted satellite transmitters in three loons<br />

in central <strong>Minnesota</strong> this past July to follow<br />

their movements south this fall (their migration<br />

is being tracked online at www. umesc. usgs.<br />

gov/terrestrial!migratory _birds!loons/migrations.html).<br />

"It is a small sample size;' Henderson said,<br />

"but it could help us develop longer-term<br />

strategies for monitoring the fate <strong>of</strong> loons on<br />

their wintering grounds:'<br />

DNR waterfowl biologist Steve Cordts said<br />

that other diving birds, including duck species<br />

such as scaup, redheads, and canvasbacks, also<br />

continue to be threatened by after -effects from<br />

the oil spill. In an attempt to keep migrating<br />

waterfowl from heading into the Gulf, government<br />

agencies and conservation groups<br />

are working together to create temporary<br />

wetlands north <strong>of</strong> the area affected by the spill.<br />

For example, Ducks Unlimited is paying rice<br />

farmers to flood their fields in the fall. Bird<br />

experts hope that migrating waterfowl will see<br />

these wetlands first and winter there, instead <strong>of</strong><br />

flying farther south to the Gulf<br />

As for the Gulf, only tinle will tell what the<br />

ultinlate impact will be on migratory birds.<br />

8<br />

MINNE<strong>SO</strong>TA CONSERVATION VOLUNTEER

"[Waterfowl] need a clean, healthy, and diverse marine environment.<br />

It may take years to restore such an environment in<br />

the Gulf No one knows at this point how long that may take;'<br />

said Henderson. "When the environment is cleaned up, then<br />

the wildlife victims <strong>of</strong> the oil spill can begin to recover. We aren't<br />

going to know [the impact] until birds start coming back:'<br />

Birgitta Anderson, editorial intern<br />

(,. www.mndnr.govjmagazine See a multimedia video <strong>of</strong> the loons being<br />

tagged with satellite transmitters.<br />

Dollars for Wildlife Action<br />

DURING THE PAST DECADE, <strong>Minnesota</strong>'s wildlife species<br />

in greatest conservation need have benefited from the federally<br />

funded State Wildlife Grants program. Congress created<br />

the program in 2000 with two aims: to prevent species from<br />

becoming threatened or endangered and to aid recovery<br />

<strong>of</strong> species already listed. The program required each state<br />

wildlife agency and their conservation partners to develop<br />

a wildlife action plan. <strong>Minnesota</strong>'s plan, Tomorrows Habitat<br />

for the Wild and Rare, identifies native species that are rare,<br />

declining, or vulnerable to decline; and it outlines actions to<br />

help protect and recover them.<br />

<strong>Minnesota</strong>'s loon monitoring program, for example,<br />

receives funding from the program. Baseline population<br />

data from this long-term monitoring project will be<br />

instrumental in assessing the impact <strong>of</strong> the recent oil spill in<br />

the Gulf <strong>of</strong> Mexico on <strong>Minnesota</strong>'s loon population.<br />

Together, the states' wildlife action plans amount to a<br />

nationwide strategy to recover native species and prevent<br />

them from becoming endangered. In 10 years, <strong>Minnesota</strong><br />

has received $12.5 million to support over 50 projects<br />

benefiting species from northern myotis bats and Blanding's<br />

turtles, to longear sunfish and greater redhorse fish,<br />

to regal fritillary butterflies and timber rattlesnakes. DNR<br />

staff and partners identify priority conservation areas,<br />

purchase land, restore and manage habitat, and conduct<br />

species and habitat research. To learn more, visit www.<br />

mndnr.gov/cwcs/swg.html.<br />

Sarah Wren, DNR rare species guide project manager<br />

NEw CHAMP<br />

A new big tree champion red<br />

pine, <strong>Minnesota</strong>'s state tree, was<br />

found in Chippewa National<br />

Forest near the Lost Forty Trail.<br />

The tree's circumference 4 1 /> feet<br />

above the ground is 115 inches.<br />

Its height is 120 feet, and its<br />

crown spread is 38 feet.<br />

SEA<strong>SO</strong>N OPENERS<br />

Sept. 1: bear, mourning dove,<br />

snipe, rail; Sept. 4: early Canada<br />

goose season; Sept. 18: small<br />

game, archery deer; Sept. 25:<br />

woodcock; Oct. 2: waterfowl, fall<br />

turkey, moose; Oct. 16: pheasant.<br />

SEPTEMBER-OCTOBER <strong>2010</strong><br />

9

10<br />

new hunting

terms <strong>of</strong> habitat and the quality and percentage<br />

<strong>of</strong> mature bucks that are taken, the central<br />

part <strong>of</strong> the state is good, but the southeast<br />

part <strong>of</strong> the state is probably better:'<br />

Southeastern <strong>Minnesota</strong> has superb<br />

deer habitat and too many deer in many<br />

places. For the past five years, the DNR<br />

has been studying regulations aimed at reducing<br />

the deer population while increasing<br />

the potential for larger-antlered bucks.<br />

This year, the DNR will implement these<br />

new regulations in southeast <strong>Minnesota</strong>.<br />

Lots <strong>of</strong> Deer. Deer densities in the southeast<br />

are among the state's highest, ranging from<br />

ownership, hunters can have a hard time<br />

getting permission to hunt deer. For comparison,<br />

parts <strong>of</strong> northern <strong>Minnesota</strong> are 40<br />

to 50 percent public land.<br />

While some hunters prefer high deer densities<br />

because it makes hunting easier, many<br />

landowners and residents in southeastern<br />

<strong>Minnesota</strong> prefer fewer deer. A high deer<br />

population creates more risk for auto collisions<br />

and more depredation <strong>of</strong> trees and<br />

other plants, including agricultural crops.<br />

Damage caused by deer is a particular problem<br />

in apple orchards, which are common<br />

in Winona and Houston counties.<br />

Although deer densities are no longer<br />

Antlerless deer harvests could increase by 15 percent under new antler-paint restriction rules in southeastern<br />

<strong>Minnesota</strong>. The rules will be evaluated within Jive years for effectiveness and acceptance by hunters.<br />

10 to 23 deer per square mile, depending<br />

on habitat. In most <strong>of</strong> the state, the density<br />

<strong>of</strong> deer ranges from 1 to 10 deer per square<br />

mile. Deer densities are high in southeast<br />

<strong>Minnesota</strong>'s oak forests and agricultural<br />

fields because the area provides abundant<br />

acorns, corn, and alfalfa for deer to eat. The<br />

area is also known for milder winters and a<br />

lack <strong>of</strong> large predators, such as wolves. Another<br />

reason is light hunting pressure-with<br />

roughly 92 percent <strong>of</strong> the area in private<br />

climbing in the southeast, thanks to increased<br />

bag limits and longer deer hunting<br />

seasons, they remain above deer density<br />

goals <strong>of</strong> 10 to 17 deer per square mile set<br />

by the DNR with input from local residents<br />

and hunters. Moreover, many hunters say<br />

theyCl like to see more bucks with larger antlers<br />

rather than just lots <strong>of</strong> deer. About half<br />

<strong>of</strong> respondents to a random survey <strong>of</strong> deer<br />

hunters this past spring said theyCl support<br />

more restrictive hunting regulations<br />

12<br />

MINNE<strong>SO</strong>TA CONSERVATION VOLUNTEER

that might result in more mature bucks.<br />

This year, for the southeast, the DNR will<br />

implement new deer hunting regulations<br />

aimed at increasing the harvest <strong>of</strong> does while<br />

protecting yearling bucks so they can live<br />

longer and can potentially grow larger antlers.<br />

The regulations will mark a departure<br />

from current deer population management,<br />

which focuses on maintaining acceptable<br />

deer densities without regard to the age or<br />

antler size <strong>of</strong> bucks.<br />

Earn-A-Buck. In 2005 Marrett Grund,<br />

DNR farmland deer research biologist,<br />

and Cornicelli designed a five-year study<br />

to test regulations that reduce deer density,<br />

with the secondary benefit <strong>of</strong> providing<br />

more mature bucks. They also wanted<br />

to develop regulations that hunters would<br />

understand and abide. They focused their<br />

study on state parks where hunters had to<br />

apply for a special permit and could be easily<br />

identified and surveyed. State parks also<br />

provided a more controlled environment<br />

because hunters had to present their deer<br />

for registration before leaving.<br />

At St. Croix, Wild River, Great River<br />

Bluffs, and Maplewood state parks, as well<br />

as Lake Elmo Park Reserve in Washington<br />

County, hunters were allowed to harvest a<br />

buck only after tagging an antlerless deer, a<br />

regulation known as Earn-A-Buck.<br />

At Savanna Portage, Itasca, and Forestville/Mystery<br />

Cave state parks, they tested<br />

a regulation known as an antler point<br />

restriction, where hunters were only allowed<br />

to harvest bucks with at least three<br />

or four antler points on one side, depending<br />

on the park. This regulation protects<br />

yearling bucks from harvest because most<br />

yearlings don't have enough antler points<br />

to be legal during the deer season.<br />

Each year the hunters were asked for<br />

their opinions <strong>of</strong> their hunt, including their<br />

overall level <strong>of</strong> satisfaction and whether<br />

they planned to return to the park to hunt<br />

the next year. In addition the age, sex, and<br />

antler size <strong>of</strong> each deer harvested in the<br />

parks was recorded.<br />

The data showed that the Earn-A-Buck<br />

regulations increased the antlerless harvest<br />

by 60 to 70 percent in the first year and<br />

slightly increased the number <strong>of</strong> mature<br />

bucks in the population.<br />

"We know that most hunters only take one<br />

deer, even when they had to take a doe first.<br />

Given that, we ended up protecting some<br />

bucks because [hunters] just don't tend to<br />

take more than a single dee[,' Cornicelli says.<br />

Many hunters said they didn't like the<br />

regulation because it forced them to harvest<br />

an antlerless deer first, Grund says.<br />

"According to our surveys, about 40 percent<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>Minnesota</strong> deer hunters will never<br />

harvest an antlerless deer:' he says. "Many<br />

hunters grew up in a tradition <strong>of</strong> harvesting<br />

bucks only. Theyu rather go home<br />

empty-handed:'<br />

More Popular. Restricting hunters to bucks<br />

with at least three or four antler points on<br />

one side was more popular, but that regulation<br />

increased the antlerless harvest by only<br />

10 to 15 percent, Grund says. The regulation<br />

also successfully increased the number<br />

<strong>of</strong> adult bucks with large antlers. At Itasca<br />

State Park, the percentage <strong>of</strong> 4V2-yearold<br />

bucks-trophy deer with large, heavy<br />

beamed antlers-increased from 4 percent<br />

<strong>of</strong> the deer population to more than 10 percent<br />

during the five-year study.<br />

Cornicelli says antler-point restrictions<br />

SEPTEMBER-OCTOBER <strong>2010</strong><br />

13

work on the principle that most hunters<br />

harvest only one deer each season, no<br />

matter the bag limit. "If a hunter doesn't<br />

think they are going to get an opportunity<br />

at a mature buck, some <strong>of</strong> them will harvest<br />

a doe because they want the venison;'<br />

he says.<br />

The study showed that both regulations<br />

increased the antlerless harvest and protected<br />

bucks. Antler-point restrictions didn't<br />

increase the antlerless harvest as much as<br />

Earn-A-Buck regulations did, but the former<br />

received more support from hunters.<br />

"Deer densities aren't that far out <strong>of</strong><br />

goal in southeast <strong>Minnesota</strong>, and a 60<br />

Although this hunt accounts for only 15<br />

percent <strong>of</strong> the overall deer harvest (2,890<br />

deer in 2009), Cornicelli says the lack <strong>of</strong><br />

conflicts with other outdoor enthusiasts<br />

and the satisfaction <strong>of</strong> hunters who participated<br />

was clear from the beginning.<br />

"When we looked at the data after<br />

the first year we decided to make<br />

that season operational by expanding<br />

the early antlerless area, including the<br />

southeast in 2007 :'<br />

Modest Support. After the five-year study,<br />

Grund and Cornicelli conducted a mail survey<br />

<strong>of</strong> southeastern hunters to gauge what<br />

In 2004, Missouri implemented antler-point restrictions for hunters in 29 counties. By 2007 the<br />

harvest <strong>of</strong> adult bucks in those counties had increased by as much as 62 percent.<br />

14<br />

to 70 percent increase in the doe harvest<br />

isn't required;' Grund says. "Antler-point<br />

restrictions are a better fit than Earn<br />

A-Buck right now. We would consider<br />

Earn-A-Buck in situations where we need<br />

to quickly increase the antlerless deer harvest<br />

in a specific area:'<br />

The state park study also looked at the<br />

effectiveness <strong>of</strong> allowing an antlerlessonly<br />

hunt for two days in October in<br />

areas where deer densities remain high.<br />

they want from new deer regulations. Nearly<br />

2,000 hunters who purchased a license to<br />

hunt deer in southeastern <strong>Minnesota</strong> during<br />

the 2008 season responded.<br />

Of the regulatory options that would<br />

result in more mature bucks, eliminating<br />

rules that allow members <strong>of</strong> the same<br />

hunting party to tag bucks for each other (a<br />

practice known as cross-tagging) garnered<br />

the most support with 50 percent. Instituting<br />

antler-point restrictions earned 47<br />

MINNE<strong>SO</strong>TA CONSERVATION VOLUNTEER

percent support. The option <strong>of</strong> delaying<br />

firearms seasons until later in November,<br />

when the rut or deer breeding season has<br />

ended, received less than 30 percent support.<br />

Some hunters believe bucks are less<br />

wary during the rut and more vulnerable<br />

to harvest. The option <strong>of</strong> requiring hunters<br />

to harvest a doe before harvesting a buck<br />

was not part <strong>of</strong> the survey, Cornicelli says,<br />

because that measure wouldn't be necessary<br />

in the southeast.<br />

Marty Stubstad, Bluffiand Whitetail Association<br />

board member, says his group<br />

would have preferred to delay the firearms<br />

deer season until later November,<br />

when the deer breeding season was over.<br />

Still, he's supportive <strong>of</strong> regulations aimed<br />

at protecting young bucks.<br />

"It was never part <strong>of</strong> the plan to tell people<br />

what kind <strong>of</strong> deer they could shoot:'<br />

Stubstad says. "But [antler-point restrictions]<br />

seem to be the only solution to start<br />

increasing the age level <strong>of</strong> our ded'<br />

JohnNy Vang, state director <strong>of</strong> the Capital<br />

Chapter <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Minnesota</strong> Deer Hunters<br />

Association, isn't sure how fellow Hmong<br />

hunters might react to the new regulations.<br />

"Some <strong>of</strong> them hunt for big bucks, so they'll<br />

probably support the new regulations:' he<br />

says. "Others hunt for meat, and they're not<br />

going to like having to pass up a buck because<br />

it doesn't have big antlers:'<br />

While hunters will sometimes have to<br />

pass on a yearling buck because <strong>of</strong> the new<br />

regulations, Cornicelli says there will still<br />

be ample opportunity to shoot does.<br />

"Passing on yearling bucks is part <strong>of</strong><br />

the compromise necessary to balance our<br />

deer population objectives against the<br />

clear interest that hunters have in seeing<br />

more mature bucks:'<br />

Increase in Leases? If antler-point restrictions<br />

successfully increase the number <strong>of</strong><br />

mature bucks in southeastern <strong>Minnesota</strong>,<br />

some hunters worry that landowners will<br />

lease large blocks <strong>of</strong> land at high prices to<br />

hunters seeking trophy deer. Conversely,<br />

some say that successful antler-point restrictions<br />

would produce more mature<br />

bucks across the landscape, including on<br />

public land. Hunters might be less likely to<br />

purchase a lease if they have a reasonable<br />

chance at a large buck on public land.<br />

"''m not sure which side <strong>of</strong> that debate is<br />

right;' Cornicelli says. "I don't think either<br />

argument is 100 percent correct, and we'll<br />

probably see better opportunities on public<br />

land and some increase in the number <strong>of</strong><br />

trophy leases. We do need to keep a close<br />

eye on any issue that would further limit<br />

hunting access in the southeast:'<br />

Whatever the outcome <strong>of</strong> antler-point<br />

restrictions, Cornicelli says protecting bucks<br />

with four points or fewer on one side is a<br />

philosophical shift in deer management.<br />

"Saying as an agency that a mature buck<br />

is more important than the yearling buck<br />

represents a significant change in deer management:'<br />

he says. ''At the core, we're still<br />

managing deer density in a way that has biological<br />

merit, so it's not a fundamental shift.<br />

"However, it will be a big change for<br />

hunters:' .<br />

New Southeast Deer Regulations<br />

• Harvested bucks must have at least one<br />

4-point antler (youth ages 10 to 17 may<br />

harvest any buck)<br />

• No cross-tagging <strong>of</strong> bucks; a member <strong>of</strong><br />

a hunting party who harvests a buck must<br />

use his or her own tag.<br />

SEPTEMBER-OCTOBER <strong>2010</strong><br />

15

~Annette Dray Drewes<br />

~~tep4 by Marc Norberg<br />

Each fall <strong>Minnesota</strong>ns harvest tens <strong>of</strong> thousands <strong>of</strong> pounds <strong>of</strong><br />

ripe wild rice. But only a few dozen processors are practicing the<br />

art <strong>of</strong> parching, threshing, and winnowing the rice for the table.<br />

THREE FEET ABOVE MY HEAD the slightly moving,<br />

tawny green stalks <strong>of</strong> rice quietly close around us.<br />

Sound, sky, and light filter through these living walls<br />

as slowly we pick up a rhythm, reaching, parting, and<br />

pulling rice stalks over the side <strong>of</strong> the boat. Strong, alternating<br />

sweeps <strong>of</strong> the knocking sticks bring a shower<br />

<strong>of</strong> heavy seed, raining into the bottom <strong>of</strong> the canoe.<br />

Coming to open water in the rice bed, we pause. I<br />

sink my hand deep into the pile <strong>of</strong> rice in front <strong>of</strong> me.<br />

The heavy seed, a mixture <strong>of</strong> pale greens and purples,<br />

feels solid, rich, sustaining. Atop the pile, the slender<br />

awns point skyward, creating a peltlike covering.<br />

Gathering the rice <strong>of</strong>f this northern <strong>Minnesota</strong><br />

lake is only the first step in the process <strong>of</strong> turning<br />

the state's native grass into a dish for the dinner table.<br />

TOP: A WILD RICE BED NEAR MCGREGOR, MI LLE LACS BAND ELDER DALE GREENE; MIDD LE: WH ITE EARTH ELDER OSCAR"SUNFISH"OPPEGARD, PARCHED WILD<br />

RICE BEING COLLECTED FOR THRESHING; BOTIOM : FRESHLY HARVESTED RICE DRYING ON A TARP, LEECH LAKE BAND MEMBER MARTIN JENNINGS

~e Lacs Band <strong>of</strong> Ojibwe elder Kaadaak-Dale Greene Sr.-and his grandson Maaclwoz (top left)<br />

discuss wild rice processing at their plant west <strong>of</strong> McGregor. Hand-harvested wild rice is parched inside a drum<br />

heated by a gas burner (below). Parched rice (top right) ready to be threshed is removed from the drum.<br />

Greene inspects parched rice (opposite page) to ensure it is dry enough to be threshed.

Like other grains, wild rice must be dried<br />

(parched), the grain separated from the<br />

hull (threshed), and cleaned (winnowed)<br />

before it is ready for storage in the pantry.<br />

For first-time ricers and many who harvest<br />

for personal use, locating someone to<br />

finish the rice is the most challenging step<br />

because the number <strong>of</strong> processors in most<br />

areas is dwindling.<br />

Harvesters in a 2006 <strong>Department</strong> <strong>of</strong><strong>Natural</strong><br />

<strong>Resources</strong> survey identified finding a<br />

processor as one <strong>of</strong> the top three barriers to<br />

harvesting wild rice; the others were knowing<br />

when and where to harvest. Some 85<br />

percent said they gather wild rice for personal<br />

use. This is a shift from the 1950s<br />

and '60s, when wild rice was considered a<br />

cash crop and <strong>Minnesota</strong> supplied about<br />

half <strong>of</strong> the wild rice consumed worldwide.<br />

Declining participation in harvesting and<br />

market economics have influenced the<br />

number <strong>of</strong> wild rice processors able to stay<br />

in the market.<br />

Simply put, processing wild rice is a<br />

dying art, and few are stepping forward<br />

to continue the tradition.<br />

Many kinds <strong>of</strong> processors. Indigenous<br />

people <strong>of</strong> the region have practiced the<br />

fall gathering <strong>of</strong> wild rice for thousands<br />

<strong>of</strong> years. Today this gathering involves<br />

both Ojibwe and nontribal harvesters.<br />

Annual licenses sold by the DNR to harvest<br />

wild rice peaked at 16,000 in the late<br />

1960s and in recent years has typically<br />

numbered around 1,500. Roughly twice<br />

that number <strong>of</strong> harvesters participate<br />

under tribal regulation.<br />

How many wild rice processors are<br />

there in <strong>Minnesota</strong>? No one knows ex-<br />

actly because processors don't need to be<br />

licensed by the state unless they buy wild<br />

rice for resale. Processing operations<br />

come in various sizes. Some families and<br />

friends finish their own rice using traditional<br />

methods. Small side-yard processors,<br />

usually found by word <strong>of</strong> mouth,<br />

process batches <strong>of</strong> 100 to 300 pounds.<br />

Large operations with permanent facilities<br />

can handle 1,000-pound orders.<br />

Tucked in the woods just west <strong>of</strong><br />

McGregor is the wild rice processing<br />

business <strong>of</strong> Dale Greene Sr., a Mille<br />

Lacs Band <strong>of</strong> Ojibwe elder <strong>of</strong> 77 years.<br />

Greene sits outside one <strong>of</strong> two new<br />

buildings, his calloused hands working<br />

on an electrical switch. He has been<br />

processing wild rice for over 10 years,<br />

was a buyer before that, and prior to<br />

that harvested wild rice beginning at<br />

age 12. He learned the art <strong>of</strong> processing<br />

from Clarence Sandberg, former owner<br />

<strong>of</strong> the plant. Greene runs one <strong>of</strong> the<br />

larger operations for custom processing<br />

<strong>of</strong> hand-harvested rice and draws<br />

harvesters in from as far away as White<br />

Earth, 180 miles to the northwest.<br />

Inside one building, four large black<br />

parchers line up over propane burners.<br />

Each can dry up to 300 pounds <strong>of</strong> wild<br />

rice. Propane provides a consistent,<br />

clean heat, yet each batch <strong>of</strong> rice is dif-<br />

SEPTEMBER-OCTOBER <strong>2010</strong><br />

19

ferent and must be watched accordingly.<br />

In a quiet voice, Greene describes<br />

the responsibility <strong>of</strong> keeping wild rice<br />

ecosystems healthy. "We need to quit<br />

messing with dams on the lakes, trying<br />

to control water levels;' he says. "Spring<br />

flows bring in nutrients and flush out the<br />

dead leaves and stuff, allowing the rice<br />

seed to get into the bottom mud:'<br />

One <strong>of</strong> his grandsons approaches<br />

with a test scoop <strong>of</strong> parched rice. Greene<br />

pours a few grains into his hand. Snapping<br />

a kernel in half, he looks inside for<br />

that glossiness he uses to judge when the<br />

rice is done. He nods and says it's close.<br />

"My grandsons have their hearts into<br />

White Earth elder, runs a small, side-yard<br />

wild rice processing operation. Most harvesters<br />

here are locals from the reservation,<br />

yet some come from as far as Mille<br />

Lacs and McGregor.<br />

A delicious aroma wafts on the breeze.<br />

The rhythmic sound <strong>of</strong> wild rice being<br />

turned emanates from the parcher, a large<br />

metal fuel tank able to hold 250 pounds <strong>of</strong><br />

rice. A paddle wheel moves the rice up the<br />

sides <strong>of</strong> the tank, then lets it fall back to the<br />

heat on the bottom. The sound reminds<br />

one <strong>of</strong> ocean waves breaking on the shore.<br />

The parcher requires a constant watch<br />

as the wood stacked beneath it burns.<br />

Steam escapes from an opening on top, a<br />

wild rice;' he says. Four <strong>of</strong> them and a<br />

nephew work with him to process wild rice.<br />

This year Greene will process nearly<br />

10,000 pounds, a number he hopes to<br />

increase substantially next year.<br />

"More harvesters are coming to us because<br />

processors are getting scarce:'<br />

Greene considers his work a service.<br />

"Younger people don't want to take it on,<br />

no money in if' But he has hope through<br />

his grandsons, if the rice stays healthy.<br />

Yard processing. On the White Earth<br />

Indian Reservation along the low shores<br />

<strong>of</strong> Roy Lake, Oscar "Sunfish" Oppegard, a<br />

sign <strong>of</strong> moisture still in the rice. Ask most<br />

harvesters and you will get an opinion regarding<br />

the better fuel for parching, propane<br />

or wood.<br />

"Hard parch [with wood] gives you a<br />

little bit different flavor. Lot <strong>of</strong> people like<br />

what I'm doing here;' says Oppegard.<br />

Constantly on the move, Oppegard<br />

checks each batch <strong>of</strong> rice before moving<br />

it to the next processing stage. With<br />

two parchers going, a backlog <strong>of</strong>ten occurs<br />

at the thresher, or dehuller, a modified<br />

55-gallon oil drum. Inside the drum,<br />

rubber-coated paddles beat the parched<br />

rice, breaking the hulls loose. An old, red<br />

20<br />

MINNE<strong>SO</strong>TA CONSERVATION VOLUNTEER

ahe White Earth Indian Reservation, bags <strong>of</strong> hand-harvested rice (opposite page) are ready to be processed<br />

byOscar"Sunfish"Oppegard.At his small processing operation, rice is parched inside a metal fuel tank (below).<br />

which is heated with a wood fire (top left). Rice parched with wood heat, or hard parched, takes on a flavor that<br />

some harvesters prefer. Oppegard (top right) winnows parched and threshed rice with a large fan.

£ch lake Band member Martin jennings and his son Marty (top left) process small batches <strong>of</strong> rice by<br />

hand. Rice is parched in a cast-iron kettle (opposite page) over an open fire. jennings separates the parched<br />

rice grain from the hull by foot (top right)-a process known as 'jigging."jennings (below) winnows wild<br />

rice with a birch-bark tray that he crafted by hand.

McCormick Farmall tractor provides the<br />

power to the thresher.<br />

Oppegard muses that he would like to<br />

build a bigger mill for the future, in duding<br />

ro<strong>of</strong>ing over some <strong>of</strong> the equipment<br />

and adding a new and different thresher.<br />

Traditional processing. South<strong>of</strong>Garrison<br />

near Whitefish Lake, Martin Jennings<br />

and his family process their own rice. A<br />

Leech Lake Band member, Jennings began<br />

"finishing" wild rice in college.<br />

In an old field, wild rice is spread out<br />

on tarps, drying in the sun. Nearby a<br />

wood fire burns beneath a mediumsized<br />

cast-iron kettle, one-third filled<br />

with rice. From a chair beside the kettle,<br />

Joyce Shingobe, a family friend, stirs<br />

the rice with a small cedar paddle. She<br />

scoops the rice up one side <strong>of</strong> the tilted<br />

kettle, then lets it cascade back to the<br />

heat. Too much heat will pop the ricelike<br />

popcorn. In 20 minutes this batch<br />

should be thoroughly parched.<br />

Jennings and his son Marty walk<br />

across the field to a friend's cabin tucked<br />

in the edge <strong>of</strong> the forest. In the yard, a<br />

clump <strong>of</strong> birch trees provides the perfect<br />

setting for jigging rice. Two stout, 8-foot<br />

poles meet high in the birches and support<br />

the thresher-Jennings. He stands<br />

in a wooden tub filled with parched wild<br />

rice. He twists his smooth-soled boots<br />

back and forth to separate the rice from<br />

the hulls.<br />

Jennings pauses after roughly eight<br />

minutes, sweat beading his face. On a<br />

good day, he can jig out about 40 pounds<br />

<strong>of</strong> fully parched rice an hour. Today he<br />

empties about half <strong>of</strong> the rice from the<br />

tub into a birch-bark winnowing tray,<br />

which he made by hand.<br />

Paying attention to the slight breeze,<br />

he tosses the rice up with a smooth motion<br />

<strong>of</strong> his wrists, allowing the chaff to<br />

fall to the ground while keeping the full<br />

seed solidly in the basket. It's a practiced<br />

motion, one that he has done for nearly<br />

30 years-and one that he says he will<br />

continue to do as long as he can.<br />

For future generations. Though <strong>Minnesota</strong><br />

has fewer processors <strong>of</strong> native<br />

wild rice today, business is booming for<br />

the remaining processors. And some <strong>of</strong><br />

those processors would welcome a little<br />

more competition.<br />

"We were loaded right to the last daY,'<br />

says Oppegard <strong>of</strong> the demand at his yardprocessing<br />

operation. "There is more<br />

room for processors:'<br />

The philosophy among those working<br />

with wild rice is not market -driven, but<br />

driven by tradition-and the desire to<br />

preserve this art.<br />

"I want to see the young kids get interested<br />

by participating:' says Jennings,<br />

"and pass the whole process on to the next<br />

generation:' .<br />

r.- www.mndnr.govjmagazine See a multimedia<br />

slideshow about the families who process wild rice.<br />

SEPTEMBER-OCTOBER <strong>2010</strong><br />

23

By Michael Furtman<br />

Up S and downs<br />

in the Grouse Woods<br />

The ruffed grouse population cycle<br />

works in mysterious ways, sometimes<br />

defying the best attempts <strong>of</strong> wildlife<br />

biologists to understand it.<br />

rn y grou.

3-0<br />

2.5<br />

~<br />

..<br />

Q. 2.0<br />

CD<br />

Q. loS<br />

Ill<br />

E<br />

2<br />

c 1.0<br />

26<br />

Over the years, success has varied wildly-ups<br />

and downs in the grouse woods.<br />

While all animal populations fluctuate,<br />

only those that rise and fall in large<br />

amounts and with regularity are considered<br />

cyclical. Grouse numbers rise and fall<br />

in a 10-year cycle that remains somewhat<br />

<strong>of</strong> a mystery. Wildlife managers simply call<br />

it the "grouse cycle:'<br />

''As wildlife managers, we just accept the<br />

grouse cycle as a given;' said Mike Larson,<br />

<strong>Department</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Resources</strong> research<br />

scientist and grouse biologist in Grand<br />

Rapids. "The historical data show the cycle<br />

very clearly, and whatever the reasons for<br />

it, there is little that people could do to influence<br />

it anyway. Consequently, our job is<br />

really to manage the habitat.<br />

"Providing quality habitat means there<br />

will be more ruffed grouse than there<br />

would otherwise be, no matter where we<br />

are in the cycle:' According to Larson,<br />

quality habitat for grouse contains many<br />

components, but, in general, it is a forest <strong>of</strong><br />

mixed species, predominately aspen with<br />

stands <strong>of</strong> various ages.<br />

Inevitable Cycle. Many factors influence<br />

grouse populations. But even under the<br />

best <strong>of</strong> situations, the ruffed grouse is not a<br />

long-lived bird. Few survive to 3 years <strong>of</strong> age,<br />

according to research conducted by the late<br />

Gordon Gullion, head <strong>of</strong> the Forest Wildlife<br />

Project at the University <strong>of</strong> <strong>Minnesota</strong>!;<br />

Cloquet Forestry Center. Of 1,000 eggs laid<br />

in spring, only about 250 ruffed grouse will<br />

survive to their first autumn, 120 to their first<br />

spring, about 50 to a second spring, and fewer<br />

than 20 will still be alive the third spring.<br />

Mortality comes in many forms-disease,<br />

MINNE<strong>SO</strong>TA CONSERVATION VOLUNTEER

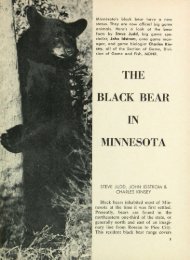

Cycle within a cycle: The ruffed grouse population<br />

shows peaks and valleys about every IO years, with "super<br />

peaks" every 20 years. But a super peak only lasts for one<br />

year, while the lower peaks can last two to three years.<br />

accidents, weather-related stress, and predation.<br />

Predation ranks highest, though it is frequently<br />

difficult to separate it from the other<br />

factors. A ruffed grouse weakened by cold or<br />

disease might have died regardless <strong>of</strong> whether<br />

it had been caught by a fox or goshawk.<br />

While losses occur every year, ruffed<br />

grouse populations, as well as those <strong>of</strong><br />

snowshoe hares, rise and fall in a cycle <strong>of</strong><br />

about 10 years and are synchronous. The<br />

ruffed grouse cycle appears to be largely<br />

unrelated to food availability or variation<br />

in reproduction due to weather.<br />

Evidence suggests there is a cycle to the<br />

cycle: a pattern that shows every other peak<br />

is higher than the intervening one. And<br />

there are differences in the cycle depending<br />

upon location. In <strong>Minnesota</strong> the cycle is<br />

most noticeable in the prime grouse range<br />

in the northeast. The cycle is more subtle<br />

in the northwestern tallgrass aspen parklands,<br />

the central hardwoods region, and<br />

the southeastern blufflands.<br />

"Where habitat isn't as good, the cycle is<br />

not as apparent;' says Larson. "In the periphery<br />

<strong>of</strong> their range, you can see minor peaks<br />

and valleys, but not every 10 years, and the<br />

peaks and valleys aren't as dramatic:'<br />

Unravel the Mystery. Several studies have<br />

tried to unravel the mystery <strong>of</strong> the grouse<br />

cycle. University <strong>of</strong> Wisconsin researcher<br />

Lloyd Keith's classic Wildlife's Ten- Year Cycle,<br />

published in 1963 and based on his work in<br />

Alberta, chronicled not only the periodic<br />

fluctuations <strong>of</strong> ruffed grouse, but also those<br />

<strong>of</strong> snowshoe hares, red fox, lynx, and prairie<br />

grouse. He found that these fluctuations are<br />

frequently related to each other and usually<br />

are synchronous among species within<br />

areas. He also noted that this cycle seems to<br />

be limited primarily to northern forests and<br />

adjacent prairie.<br />

Keith's research <strong>of</strong>fers the following explanation<br />

for the ruffed grouse cycle: Snowshoe<br />

hares, which can breed several times in one<br />

year, increase in number. Lynx, red fox, goshawks,<br />

and great horned owls prey upon the<br />

abundant hares and produce numerous <strong>of</strong>fspring.<br />

Despite the success <strong>of</strong> the predators,<br />

reproduction by the hares outpaces that <strong>of</strong><br />

the predators. Eventually; hares are so numerous<br />

that they deplete their food sources<br />

and then die <strong>of</strong>f rapidly.<br />

During this boom in hares and predators,<br />

ruffed grouse increase because the<br />

hares buffer them against predation. But<br />

when hare populations crash, the abundant<br />

predators must find another food source,<br />

such as ruffed grouse. Unlike the snowshoe<br />

hare population, the grouse population<br />

cannot reproduce fast enough to sustain its<br />

numbers while being targeted by abundant<br />

predators. Ruffed grouse numbers slowly<br />

decline, followed by a drop in the predator<br />

population. Because this cycle takes years,<br />

the woody brush that provides food for the<br />

snowshoe hare rebounds, snowshoe hare<br />

numbers climb, and the cycle repeats.<br />

However, because ruffed grouse populations<br />

are also cyclical south <strong>of</strong> the snowshoe<br />

hare's main range, some researchers looked<br />

for additional factors. In 1982 Donald Rusch<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Wisconsin Cooperative Wildlife Research<br />

Unit studied winter ruffed grouse<br />

mortality in Wisconsin. He found predation<br />

rates on ruffed grouse climbed when large in-<br />

SEPTEMBER-OCTOBER <strong>2010</strong><br />

27

28<br />

fluxes <strong>of</strong> raptors-primarily goshawks-migrated<br />

south into the northern United States<br />

during a decline in hares in their Canadian<br />

home range.<br />

Increased winter predation by migrating<br />

raptors was further documented by<br />

David Lauten <strong>of</strong> the University <strong>of</strong> Wisconsin-Madison.<br />

For his master's thesis,<br />

he radio-tagged large numbers <strong>of</strong> grouse<br />

and noted significant mortality in winters<br />

when numerous northern raptors migrated<br />

into the area. He confirmed the influx<br />

<strong>of</strong> raptors by using data from monitoring<br />

sites such as Hawk Ridge in Duluth and<br />

the Audubon Christmas bird counts.<br />

These winter studies in Wisconsin show<br />

that the 10-year cycle far to the north has<br />

impacts on more southerly grouse cycles.<br />

As the hare population subsides to the<br />

north, the grouse populations are driven<br />

down by the subsequent increased predation.<br />

Then some predators move south for<br />

the winter and prey on grouse there.<br />

Still Puzzling. But predation might not<br />

be the only factor in the cycle. Throughout<br />

most <strong>of</strong> their range, ruffed grouse depend<br />

on aspen buds for winter food. In the 1990s,<br />

Gullion documented that ruffed grouse<br />

refused to eat aspen buds in some winters<br />

because the buds had a resinous coating that<br />

inhibited digestion. Gullion speculated that<br />

in years when an outbreak <strong>of</strong> tent caterpillars<br />

stressed trees, aspens protected themselves<br />

by creating less palatable buds. Ruffed<br />

grouse switched to less abundant or nutritious<br />

foods such as birch buds, perhaps lowering<br />

grouse survival. If the trees exhibit this<br />

self-defense mechanism for more than just<br />

one winter, then a cycle could be triggered.<br />

MINNE<strong>SO</strong>TA CONSERVATION VOLUNTEER

A 2008 study by a team <strong>of</strong> researchers<br />

from the University <strong>of</strong> <strong>Minnesota</strong> and the<br />

Ruffed Grouse Society analyzed all <strong>of</strong> the<br />

research from Wisconsin, <strong>Minnesota</strong>, and<br />

elsewhere. The team looked at 27 years <strong>of</strong><br />

data from the Ruffed Grouse Societys annual<br />

hunt in Grand Rapids (during which<br />

biological data, such as age, sex, and health,<br />

is gathered from the harvested birds). The<br />

team also reviewed DNR annual spring<br />

drumming counts, which monitor grouse<br />

populations. The team examined forest tent<br />

caterpillar outbreak information, raptor migration<br />

and irruption data from Hawk Ridge<br />

and other monitoring sites, and weather data<br />

to further seek answers to the grouse cycle.<br />

The researchers concluded that the predation<br />

theory isn't sufficient to explain the<br />

grouse cycle. They found no direct correlation<br />

between influxes <strong>of</strong> migrating raptors<br />

and the cycle in <strong>Minnesota</strong>. However, they<br />

concluded predation plays a supporting role<br />

and is influenced by winter weather. Years<br />

with abundant snow and cold weather favored<br />

grouse. But in years with poor snow<br />

cover, predation may increase because<br />

grouse can't roost beneath the snow and<br />

must roost in trees. Without the warmth <strong>of</strong><br />

snow roosts, they also must feed more <strong>of</strong>ten.<br />

In both cases, they are more visible and<br />

more vulnerable to predation.<br />

"These studies are the best summaries<br />

about what is <strong>of</strong>ficially known about the<br />

ruffed grouse cycle;' said Larson. "But the<br />

fact is, we aren't able to really explain very<br />

much except that the cycle is real.<br />

"People are always inquiring about how<br />

wet, cool springs might affect nesting success.<br />

The cyclical pattern holds true despite<br />

the fact that spring weather fluctuates. You<br />

can have the best spring weather imaginable,<br />

but if we're on the downward side <strong>of</strong> the cycle,<br />

populations are still going to go down:'<br />

In other words, ideal weather might<br />

mean a larger population overall, both at<br />

the peak and at the valley, but the cycle<br />

will occur regardless <strong>of</strong> weather.<br />

Current Cycle. In the region surrounding<br />

the Great Lakes, the cycle is generally at<br />

its low point in mid-decade and at its high<br />

point in years at the end and beginning <strong>of</strong><br />

the decade. The cycle is remarkably synchronous<br />

across this range. The most recent low<br />

began in 2001 and bottomed out in 2004. As<br />

it turns out, 2009 was likely the most recent<br />

peak. Larson said that drumming counts in<br />

<strong>2010</strong> were 27 percent lower than in 2009, so<br />

the cycle might be heading down.<br />

Grouse hunting harvest rates follow the<br />

same cycle. In 2009, hunters harvested an<br />

average <strong>of</strong> 0.64 birds per day, compared<br />

with 0.4 birds at the bottom <strong>of</strong> a typical cycle.<br />

Total harvest in <strong>Minnesota</strong> can be five<br />

times larger during peak years than at the<br />

valley. However, Larson said, the 2009 harvest<br />

did not show a dramatic increase because<br />

fewer hunters went afield-roughly<br />

85,000 hunters compared with 140,000 at<br />

the last peak in 1998.<br />

Looking to This Fall. What will this fall<br />

bring to the grouse woods?<br />

"Some peaks in the cycle last for a few<br />

years;' said Larson, "but some peaks only<br />

last for one. It would have been a lot to expect<br />

<strong>2010</strong> to equal2009:'<br />

Yes, it would have. That's the nature <strong>of</strong><br />

the grouse cycle. But come fall-peak or<br />

valley, good year or poor-there'll still be<br />

a trail to walk through rolling hills and a<br />

dog eager to parse the forest's scents . •<br />

SEPTEMBER-OCTOBER <strong>2010</strong><br />

29

By David Mather<br />

Photography by Richard Hamilton Smith<br />

Zippel Bay State Park in northwestern <strong>Minnesota</strong> <strong>of</strong>fers a beachhead for<br />

launching onto a million-acre lake-or a nice<br />

sandy spot for just looking out onto the water.<br />

SMALL WAVES lap at my toes as I gaze out onto an inland<br />

ocean. The panorama <strong>of</strong> water before me is the Big Traverse,<br />

a vast expanse that is just one part <strong>of</strong> Lake <strong>of</strong> the Woods.<br />

I'm looking north toward the Northwest Angle, the familiar<br />

peak on top <strong>of</strong> <strong>Minnesota</strong>'s outline. I know from maps that<br />

the lake extends far beyond my sight, east and north toward<br />

Ontarids twisting channels, islands, and cliffs, and west into<br />

Manitoba's large, open bay.<br />

A living remnant <strong>of</strong> Glacial Lake Agassiz and nearly a<br />

million acres in size, Lake <strong>of</strong> the Woods is larger than Vermilion,<br />

Kabetogama, Winnibigoshish, Minnetonka, Mille<br />

SEPTEMBER-OCTOBER <strong>2010</strong> 31

From serene to tempestuous, the<br />

mood <strong>of</strong> Lake <strong>of</strong> the Woods is<br />

ever changing. With its protected<br />

harbor and access to these vast<br />