Adverse Drug Reactions in Clinical Practice - Journal of ...

Adverse Drug Reactions in Clinical Practice - Journal of ...

Adverse Drug Reactions in Clinical Practice - Journal of ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

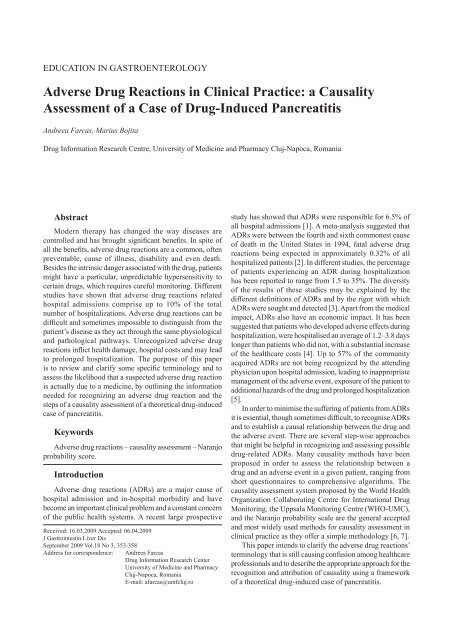

education <strong>in</strong> gastroenterology<br />

<strong>Adverse</strong> <strong>Drug</strong> <strong>Reactions</strong> <strong>in</strong> Cl<strong>in</strong>ical <strong>Practice</strong>: a Causality<br />

Assessment <strong>of</strong> a Case <strong>of</strong> <strong>Drug</strong>-Induced Pancreatitis<br />

Andreea Farcas, Marius Bojita<br />

<strong>Drug</strong> Information Research Centre, University <strong>of</strong> Medic<strong>in</strong>e and Pharmacy Cluj-Napoca, Romania<br />

Abstract<br />

Modern therapy has changed the way diseases are<br />

controlled and has brought significant benefits. In spite <strong>of</strong><br />

all the benefits, adverse drug reactions are a common, <strong>of</strong>ten<br />

preventable, cause <strong>of</strong> illness, disability and even death.<br />

Besides the <strong>in</strong>tr<strong>in</strong>sic danger associated with the drug, patients<br />

might have a particular, unpredictable hypersensitivity to<br />

certa<strong>in</strong> drugs, which requires careful monitor<strong>in</strong>g. Different<br />

studies have shown that adverse drug reactions related<br />

hospital admissions comprise up to 10% <strong>of</strong> the total<br />

number <strong>of</strong> hospitalizations. <strong>Adverse</strong> drug reactions can be<br />

difficult and sometimes impossible to dist<strong>in</strong>guish from the<br />

patient’s disease as they act through the same physiological<br />

and pathological pathways. Unrecognized adverse drug<br />

reactions <strong>in</strong>flict health damage, hospital costs and may lead<br />

to prolonged hospitalization. The purpose <strong>of</strong> this paper<br />

is to review and clarify some specific term<strong>in</strong>ology and to<br />

assess the likelihood that a suspected adverse drug reaction<br />

is actually due to a medic<strong>in</strong>e, by outl<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the <strong>in</strong>formation<br />

needed for recogniz<strong>in</strong>g an adverse drug reaction and the<br />

steps <strong>of</strong> a causality assessment <strong>of</strong> a theoretical drug-<strong>in</strong>duced<br />

case <strong>of</strong> pancreatitis.<br />

Keywords<br />

<strong>Adverse</strong> drug reactions – causality assessment – Naranjo<br />

probability score.<br />

Introduction<br />

<strong>Adverse</strong> drug reactions (ADRs) are a major cause <strong>of</strong><br />

hospital admission and <strong>in</strong>-hospital morbidity and have<br />

become an important cl<strong>in</strong>ical problem and a constant concern<br />

<strong>of</strong> the public health systems. A recent large prospective<br />

Received: 16.03.2009 Accepted: 06.04.2009<br />

J Gastro<strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong> Liver Dis<br />

September 2009 Vol.18 No 3, 353-358<br />

Address for correspondence: Andreea Farcas<br />

<strong>Drug</strong> Information Research Center<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Medic<strong>in</strong>e and Pharmacy<br />

Cluj-Napoca, Romania<br />

E-mail: afarcas@umfcluj.ro<br />

study has showed that ADRs were responsible for 6.5% <strong>of</strong><br />

all hospital admissions [1]. A meta-analysis suggested that<br />

ADRs were between the fourth and sixth commonest cause<br />

<strong>of</strong> death <strong>in</strong> the United States <strong>in</strong> 1994, fatal adverse drug<br />

reactions be<strong>in</strong>g expected <strong>in</strong> approximately 0.32% <strong>of</strong> all<br />

hospitalized patients [2]. In different studies, the percentage<br />

<strong>of</strong> patients experienc<strong>in</strong>g an ADR dur<strong>in</strong>g hospitalization<br />

has been reported to range from 1.5 to 35%. The diversity<br />

<strong>of</strong> the results <strong>of</strong> these studies may be expla<strong>in</strong>ed by the<br />

different def<strong>in</strong>itions <strong>of</strong> ADRs and by the rigor with which<br />

ADRs were sought and detected [3]. Apart from the medical<br />

impact, ADRs also have an economic impact. It has been<br />

suggested that patients who developed adverse effects dur<strong>in</strong>g<br />

hospitalization, were hospitalised an average <strong>of</strong> 1.2–3.8 days<br />

longer than patients who did not, with a substantial <strong>in</strong>crease<br />

<strong>of</strong> the healthcare costs [4]. Up to 57% <strong>of</strong> the community<br />

acquired ADRs are not be<strong>in</strong>g recognized by the attend<strong>in</strong>g<br />

physician upon hospital admission, lead<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>in</strong>appropriate<br />

management <strong>of</strong> the adverse event, exposure <strong>of</strong> the patient to<br />

additional hazards <strong>of</strong> the drug and prolonged hospitalization<br />

[5].<br />

In order to m<strong>in</strong>imise the suffer<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> patients from ADRs<br />

it is essential, though sometimes difficult, to recognise ADRs<br />

and to establish a causal relationship between the drug and<br />

the adverse event. There are several step-wise approaches<br />

that might be helpful <strong>in</strong> recogniz<strong>in</strong>g and assess<strong>in</strong>g possible<br />

drug-related ADRs. Many causality methods have been<br />

proposed <strong>in</strong> order to assess the relationship between a<br />

drug and an adverse event <strong>in</strong> a given patient, rang<strong>in</strong>g from<br />

short questionnaires to comprehensive algorithms. The<br />

causality assessment system proposed by the World Health<br />

Organization Collaborat<strong>in</strong>g Centre for International <strong>Drug</strong><br />

Monitor<strong>in</strong>g, the Uppsala Monitor<strong>in</strong>g Centre (WHO-UMC),<br />

and the Naranjo probability scale are the general accepted<br />

and most widely used methods for causality assessment <strong>in</strong><br />

cl<strong>in</strong>ical practice as they <strong>of</strong>fer a simple methodology [6, 7].<br />

This paper <strong>in</strong>tends to clarify the adverse drug reactions’<br />

term<strong>in</strong>ology that is still caus<strong>in</strong>g confusion among healthcare<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>essionals and to describe the appropriate approach for the<br />

recognition and attribution <strong>of</strong> causality us<strong>in</strong>g a framework<br />

<strong>of</strong> a theoretical drug-<strong>in</strong>duced case <strong>of</strong> pancreatitis.

354<br />

Def<strong>in</strong>itions and classification <strong>of</strong> ADRs<br />

An adverse drug event or experience is def<strong>in</strong>ed as<br />

‘any untoward medical occurrence that may present<br />

dur<strong>in</strong>g treatment with a medic<strong>in</strong>e but which does not<br />

necessarily have a causal relationship with this treatment’.<br />

An adverse event is an adverse outcome that occurs while<br />

a patient is tak<strong>in</strong>g a drug, but is not or not necessarily<br />

attributable to it. This dist<strong>in</strong>ction is important, for<br />

example, <strong>in</strong> cl<strong>in</strong>ical trials <strong>in</strong> which not all events are<br />

drug-related. When this term is used to describe adverse<br />

outcomes, physicians should be aware that it is not always<br />

possible to impute causality [8, 9].<br />

An adverse drug reaction (ADR) is ‘a response to a<br />

medic<strong>in</strong>e which is noxious and un<strong>in</strong>tended, and which<br />

occurs at doses normally used <strong>in</strong> man for the prophylaxis,<br />

diagnosis, or therapy <strong>of</strong> disease or for the modification<br />

<strong>of</strong> a physiological function’. An ADR, contrary to an<br />

adverse event is characterised by the suspicion <strong>of</strong> a causal<br />

relationship between the drug and the occurrence. This<br />

def<strong>in</strong>ition underl<strong>in</strong>es the fact that the phenomenon is noxious<br />

(differentiat<strong>in</strong>g adverse drug reaction from side-effects<br />

which can also be beneficial) and that it <strong>in</strong>cludes doses<br />

prescribed cl<strong>in</strong>ically, exclud<strong>in</strong>g accidental or deliberate<br />

overdose [8, 10].<br />

An unexpected adverse reaction is ‘an adverse reaction,<br />

the nature or severity <strong>of</strong> which is not consistent with<br />

domestic labell<strong>in</strong>g or market authorisation or expected from<br />

characteristics <strong>of</strong> the drug’ [11].<br />

A side effect is ‘any un<strong>in</strong>tended effect <strong>of</strong> a pharmaceutical<br />

product occurr<strong>in</strong>g at doses normally used by a patient,<br />

which is related to the pharmacological properties <strong>of</strong> the<br />

drug’. This def<strong>in</strong>ition was formulated to <strong>in</strong>clude side effects<br />

that, although are not the ma<strong>in</strong> aim <strong>of</strong> the therapy, may be<br />

beneficial rather than harmful. For example a β-blocker agent<br />

used to treat hypertension may, by β-blockade, also relieve<br />

the patient’s ang<strong>in</strong>a [9, 11].<br />

A serious adverse event (experience) or reaction is any<br />

untoward medical occurrence that at any dose results <strong>in</strong><br />

death; is life-threaten<strong>in</strong>g; requires <strong>in</strong>patient hospitalization or<br />

prolongation <strong>of</strong> exist<strong>in</strong>g hospitalization; results <strong>in</strong> persistent<br />

or significant disability/<strong>in</strong>capacity, or is a congenital<br />

anomaly/birth defect.<br />

There is a difference between the terms “serious” and<br />

“severe”, which are not synonymous. The term “severe” is<br />

used to describe <strong>in</strong>tensity (severity) <strong>of</strong> an event (as <strong>in</strong> mild,<br />

moderate or severe). The event itself can be <strong>of</strong> relatively<br />

m<strong>in</strong>or medical significance, such as a severe headache. This<br />

is not the same as the “serious” which is based on the patient<br />

and event outcome [8].<br />

The most common classification <strong>of</strong> ADRs is the one<br />

that dist<strong>in</strong>guishes dose-related (type A – augmented effects<br />

<strong>of</strong> the drug action) and non-dose-related (type B – bizarre<br />

reactions) adverse drug reactions. There are other groups <strong>in</strong><br />

this system <strong>of</strong> classification but these may also be considered<br />

as subclasses or hybrids <strong>of</strong> type A and B ADRs. These are<br />

type C ADRs (chronic reactions, dose- and time-related),<br />

Farcas et al<br />

type D (delayed reactions, time-related), type E (end <strong>of</strong><br />

use reactions) and type F (failure <strong>of</strong> therapy) [9, 12]. The<br />

characteristics, some examples and the management <strong>of</strong><br />

these ADRs are listed <strong>in</strong> Table I [9, 13-18]. An alternative<br />

classification system proposes only 3 major groups <strong>of</strong><br />

adverse reactions, referred as type A (drug actions), type B<br />

(patient reactions) and type C (statistical effects) adverse<br />

drug reactions [13[.<br />

ADRs’ diagnosis and causality assessment<br />

It might be difficult to establish a cl<strong>in</strong>ical diagnosis <strong>of</strong><br />

drug-<strong>in</strong>duced disease as ADRs tend to mimic any natural<br />

occurr<strong>in</strong>g disease process. Few drugs produce dist<strong>in</strong>ctive<br />

and specific physical signs that can be considered without<br />

any doubt ADRs (e.g. extrapyramidal disorders). In any<br />

case, if the patient is tak<strong>in</strong>g drugs, a differential diagnosis<br />

should consider the probability <strong>of</strong> an ADR. Several years<br />

ago Irey described, <strong>in</strong> a very comprehensive manner, the<br />

diagnostic problems that might <strong>in</strong>terfere <strong>in</strong> the evaluation <strong>of</strong><br />

an ADR and proposed a methodology that is still valid and<br />

applicable. When assess<strong>in</strong>g the probability <strong>of</strong> a suspected<br />

ADR, the cl<strong>in</strong>ician should always evaluate the follow<strong>in</strong>g<br />

aspects: temporal relationship between the use <strong>of</strong> the drug<br />

and the occurrence <strong>of</strong> the reaction (time to onset), the<br />

differential diagnosis (<strong>of</strong> causes other than the suspected<br />

drug), the selection <strong>of</strong> the responsible drug on the basis<br />

<strong>of</strong> pattern <strong>of</strong> the event or by exclusion, dechallenge and<br />

rechallenge. The pattern <strong>of</strong> the adverse event must fit<br />

the known pharmacology or allergy pattern <strong>of</strong> one <strong>of</strong> the<br />

suspected drugs or <strong>of</strong> chemically or pharmacological related<br />

compounds. Detailed <strong>in</strong>formation on all these aspects that<br />

must be considered when evaluat<strong>in</strong>g an ADR is presented<br />

<strong>in</strong> Panel 1 [9, 15, 19].<br />

When evaluat<strong>in</strong>g an ADR, one must take <strong>in</strong>to consideration<br />

the factors that can predispose patients to adverse reactions.<br />

Some ADRs are associated with specific patient and/or drugrelated<br />

factors. These factors are presented <strong>in</strong> Table II. Among<br />

these factors, the pharmacok<strong>in</strong>etic and pharmacodynamic<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>ile <strong>of</strong> a drug might be <strong>in</strong>fluenced by disease pathology,<br />

physiologic status, concomitant therapy and lifestyle.<br />

For example, excessively high or low concentrations <strong>of</strong> a<br />

drug at the site <strong>of</strong> action may occur as a result <strong>of</strong> altered<br />

pharmacok<strong>in</strong>etic <strong>of</strong> the drug (e.g. metabolism, excretion).<br />

Concurrent diseases such as renal impairment will lead to<br />

drug toxicity for drugs or drug metabolites that are highly<br />

dependent on the kidney for removal, if the dose <strong>of</strong> the drug<br />

is not properly adjusted. Likewise, doses <strong>of</strong> the drugs that<br />

undergo hepatic metabolism may also produce toxicity <strong>in</strong><br />

patients with severe hepatic disease, particularly cirrhosis.<br />

Cardiovascular disease such as congestive heart failure may<br />

also reduce hepatic blood flow and decrease the clearance<br />

<strong>of</strong> certa<strong>in</strong> drugs [20].<br />

<strong>Drug</strong>-drug <strong>in</strong>teractions contribute to a significant number<br />

<strong>of</strong> ADRs, especially <strong>in</strong> elderly patients and <strong>in</strong> patients that are<br />

under polymedication. There is an exponential relationship<br />

between the number <strong>of</strong> drugs taken and the probability <strong>of</strong> an

<strong>Adverse</strong> drug reactions <strong>in</strong> cl<strong>in</strong>ical practice 355<br />

Table I. The classification <strong>of</strong> adverse drug reaction<br />

Type <strong>of</strong> ADR Characteristics Examples Management<br />

Type A (augmented)<br />

Type B (bizarre)<br />

Type C (chronic)<br />

Type D (delayed)<br />

Type E (end <strong>of</strong> use)<br />

Type F (failure <strong>of</strong><br />

therapy)<br />

Dose-related<br />

Common (overall proportion <strong>of</strong> ADRs<br />

- 80%)<br />

Suggestive time relationship<br />

Related to a pharmacological action <strong>of</strong><br />

the drug<br />

Predictable from known pharmacology<br />

Variable severity, but usually mild<br />

High morbidity<br />

Low mortality<br />

Reproducible<br />

Not dose–related<br />

Uncommon<br />

Not related to a pharmacological action<br />

<strong>of</strong> the drug<br />

Not predictable from known<br />

pharmacology<br />

Variable severity, proportionately more<br />

severe than type A<br />

High morbidity<br />

High mortality<br />

Not reproducible<br />

Uncommon<br />

Related to cumulative dose<br />

Long term exposure required<br />

Uncommon<br />

Usually dose-related<br />

Seen on prolonged exposure to a drug<br />

or exposure at a critical time<br />

Uncommon<br />

Occurs soon after withdrawal <strong>of</strong> a drug<br />

Common<br />

May be dose-related<br />

Often caused by drug <strong>in</strong>teractions<br />

<strong>Drug</strong> toxicity<br />

Nephrotoxicity caused by am<strong>in</strong>oglicosides<br />

Dysrhythmia caused by digox<strong>in</strong><br />

Side effects<br />

Constipation caused by chronic opioid use<br />

Antichol<strong>in</strong>ergic effects <strong>of</strong> tricyclic<br />

antidepressants<br />

They derive from:<br />

Primary pharmacology (augmentation <strong>of</strong> known<br />

actions): β-blocker <strong>in</strong>duced bradycardia<br />

Secondary pharmacology (<strong>in</strong>volves different<br />

organ or system, but expla<strong>in</strong>able from known<br />

pharmacology): β-blocker <strong>in</strong>duced bronchospasm<br />

Intolerance<br />

T<strong>in</strong>nitus caused by small doses <strong>of</strong> aspir<strong>in</strong><br />

Allergy (hypersensitivity or immunological)<br />

Result <strong>of</strong> an immune response to a drug:<br />

Penicill<strong>in</strong>- <strong>in</strong>duced urticaria<br />

Pseudoallergic (non-immunological)<br />

Immediate, generalised reaction <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g<br />

mast-cell mediator release: respiratory<br />

syndromes caused by NSAIDs<br />

Idiosyncratic (unexpected response to a drug, not<br />

related to an allergic mechanism)<br />

Anticonvulsant hypersensitivity syndrome<br />

reaction<br />

Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis suppression<br />

by corticosteroids<br />

Teratogenesis<br />

Carc<strong>in</strong>ogenesis<br />

Tardive dysk<strong>in</strong>esia caused by antipsychotic<br />

medication<br />

Opiate withdrawal syndrome<br />

Rebound hypotension on clonid<strong>in</strong>e withdrawal<br />

Ineffectiveness<br />

Resistance <strong>of</strong> a micro-organism or tumour to the<br />

drug action<br />

Tolerance<br />

Tachyphylaxia<br />

Reduce dose or withhold<br />

Consider effects <strong>of</strong><br />

concomitant therapy<br />

Withhold and avoid <strong>in</strong> the<br />

future<br />

Reduce dose or withhold;<br />

withdrawal may have to be<br />

prolonged<br />

Often <strong>in</strong>tractable<br />

Re<strong>in</strong>troduce and withdraw<br />

slowly<br />

Increase dosage or change<br />

the therapeutic agent;<br />

Consider effects <strong>of</strong><br />

concomitant therapy<br />

ADR, <strong>in</strong>dependent <strong>of</strong> the therapeutic class and the patient’s<br />

underly<strong>in</strong>g disease [21]. <strong>Drug</strong> <strong>in</strong>teractions may cause altered<br />

drug bioavailability, distribution, clearance and additive or<br />

antagonistic pharmacodynamic effects. A recently published<br />

study <strong>in</strong>dicated that the percentage <strong>of</strong> drug-drug <strong>in</strong>teractions<br />

identified as cause <strong>of</strong> ADRs was 15% [22]. Another study<br />

that <strong>in</strong>vestigated potential drug <strong>in</strong>teractions concluded that<br />

68-70% <strong>of</strong> the potential <strong>in</strong>teractions detected might demand<br />

cl<strong>in</strong>ical attention, while 1-2% are life-threaten<strong>in</strong>g [23]. These<br />

<strong>in</strong>teractions have been extensively reviewed <strong>in</strong> different<br />

studies and are <strong>of</strong>ten predictable and preventable.<br />

In appropriate prescription <strong>of</strong> drugs <strong>in</strong> the elderly<br />

population is also a major risk factor for present<strong>in</strong>g ADRs<br />

although <strong>in</strong>correctly used drugs constitute a cause <strong>of</strong> ADRs<br />

<strong>in</strong> the general population too [22, 24]. A recent prospective<br />

study demonstrated that from the total number <strong>of</strong> drugs used<br />

by the study population, 26% were <strong>in</strong>correctly used and that<br />

44.5% <strong>of</strong> the ADRs detected <strong>in</strong>volved at least one <strong>in</strong>correctly<br />

used drug [25]. Unknown co-medication to the treat<strong>in</strong>g<br />

physician, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g self-medication, may compromise<br />

drug safety, by <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g the risk <strong>of</strong> duplicate therapy, drug<br />

<strong>in</strong>teractions, and ADRs that are not recognised as such [26].<br />

Thus, it is essential to <strong>in</strong>terview the patient <strong>in</strong> order to take a<br />

proper full drug history and to consider a drug-related cause<br />

for the patient’s condition especially when other causes do<br />

not expla<strong>in</strong> it. All these factors that might predispose patients<br />

to ADR must be taken <strong>in</strong>to consideration when evaluat<strong>in</strong>g<br />

an adverse event.<br />

The development <strong>of</strong> a symptom or detrimental outcome<br />

while under therapy with several drugs, does not establish<br />

the fact that one <strong>of</strong> the drugs might be the cause <strong>of</strong> the <strong>in</strong>jury.<br />

Likewise, the development <strong>of</strong> an adverse event or disease,<br />

with no relevant time relationship with the use <strong>of</strong> a drug does<br />

not exonerate the drug from be<strong>in</strong>g the causative agent. In<br />

any case, the failure to recognise an adverse drug reaction,<br />

may lead to <strong>in</strong>appropriate measures. The universal decision<br />

to treat an unrecognised drug-related symptom with another<br />

medication exposes the patient to additional drug hazards. In

356<br />

Farcas et al<br />

Panel 1. Po<strong>in</strong>ts to consider for the evaluation <strong>of</strong> a suspected adverse drug reaction<br />

a. The temporal relationship (time to onset)<br />

There should be a plausible temporal relationship between exposure and the onset <strong>of</strong> the suspected ADR, tak<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>to consideration the<br />

pharmacological characteristics <strong>of</strong> the suspected drug. For short-term reactions, e.g. flush<strong>in</strong>g with nifedip<strong>in</strong>e, the relevant time to onset<br />

is the time between the last dose and the onset <strong>of</strong> the reaction. For long-term reactions, e.g. hepatitis with methotrexate, the relevant<br />

period is the time from the beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> the therapy and ADR onset.<br />

b. Exist<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>formation about the ADR<br />

The event described had been previously reported as an ADR <strong>in</strong> cl<strong>in</strong>ical trials, post-market<strong>in</strong>g studies, case reports. If the event is not<br />

documented anywhere else, it does not necessarily mean that it cannot occur with the suspected drug.<br />

c. Pharmacological plausibility<br />

Most type A reactions are pharmacodynamic and pharmacok<strong>in</strong>etic plausible, though easy to diagnose. However, the recognition <strong>of</strong><br />

type B reaction might be difficult if previous reports on that particular ADR are not available.<br />

d. Exclusion <strong>of</strong> other causes<br />

Alternative causes (other than the suspected drug) such as patient’s underly<strong>in</strong>g disease or other drugs cannot expla<strong>in</strong> the reaction.<br />

e. Dechallenge or dose reduction<br />

Recovery or condition improvement after stopp<strong>in</strong>g the drug or after the dose reduction is supportive for a causal relationship,<br />

particularly when the tim<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> the recovery/condition improvement is consistent with the pharmacological characteristics <strong>of</strong> the drug;<br />

some ADRs might be irreversible.<br />

f. Rechallenge or dose <strong>in</strong>crease<br />

The recurrence <strong>of</strong> the ADR after dose <strong>in</strong>crease or rechallenge is a strong <strong>in</strong>dicator <strong>of</strong> causality. Rechallenge is justifiable only if the<br />

benefit to the patient outweighs the risks <strong>of</strong> the reaction’s recurrence, as <strong>in</strong> some cases the reaction (especially type B reactions) may<br />

be more severe or even fatal on repeated exposure.<br />

g. <strong>Drug</strong> <strong>in</strong>teractions<br />

If a drug <strong>in</strong>teraction is suspected <strong>in</strong> caus<strong>in</strong>g the ADR, plausible temporal relationship with the <strong>in</strong>troduction or withdrawal <strong>of</strong> the<br />

<strong>in</strong>teract<strong>in</strong>g drug is an important consideration <strong>in</strong> causality assessment.<br />

order to avoid multiple drug events, adverse drug reactions<br />

recognition is mandatory, as <strong>in</strong> this case, the appropriate<br />

action is the dose reduction or even the discont<strong>in</strong>uation <strong>of</strong><br />

the causative drug. Determ<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g if an adverse event is caused<br />

by a certa<strong>in</strong> drug with reasonable certa<strong>in</strong>ty is a difficult part<br />

<strong>of</strong> ADRs’ evaluation, but it is essential for proper cl<strong>in</strong>ical<br />

decisions [27, 28].<br />

The aim <strong>of</strong> the causality assessment is to establish a<br />

level <strong>of</strong> probability regard<strong>in</strong>g the suspicion that a certa<strong>in</strong><br />

drug is responsible for an adverse event. Accord<strong>in</strong>g to the<br />

most widely used with or without score algorithms, ADRs<br />

can be “certa<strong>in</strong>”, “probable/likely”, “possible” and “unlikely/<br />

doubtful”. The WHO-UMC developed a causality system<br />

which takes <strong>in</strong>to account the cl<strong>in</strong>ical-pharmacological<br />

aspects, whereas previous knowledge <strong>of</strong> the ADR plays a<br />

less prom<strong>in</strong>ent role [6]. Perhaps the most commonly used<br />

causality assessment method, which has ga<strong>in</strong>ed popularity<br />

among cl<strong>in</strong>icians because <strong>of</strong> its simplicity, is the Naranjo<br />

probability scale presented <strong>in</strong> Panel 2. It is a structured,<br />

transparent, consistent and easy to apply assessment method<br />

[15].<br />

Causality assessment <strong>of</strong> a theoretical drug<strong>in</strong>duced<br />

case <strong>of</strong> pancreatitis<br />

A 56-year old female with a history <strong>of</strong> hypertension,<br />

heart failure and type 2 diabetes mellitus was admitted<br />

to an <strong>in</strong>ternal medic<strong>in</strong>e department present<strong>in</strong>g abdom<strong>in</strong>al<br />

pa<strong>in</strong> radiat<strong>in</strong>g to the back, nausea and vomit<strong>in</strong>g, jaundice,<br />

anorexia, sweat<strong>in</strong>g, weakness, headache and low-grade fever<br />

(38.7°C) for the previous 3 days. The patient’s therapy <strong>in</strong><br />

the last six months <strong>in</strong>cluded digox<strong>in</strong> 0.25 mg daily except<br />

on Thursdays and Sundays, hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg once<br />

daily and a comb<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>of</strong> rosiglitazone/metform<strong>in</strong> 1mg/<br />

500 mg. Two months prior to admission alfacalcidol 2μg<br />

and calcium 1000 mg daily were <strong>in</strong>itiated for osteoporosis<br />

prophylaxis. There was no history <strong>of</strong> alcohol <strong>in</strong>gestion or<br />

previous abdom<strong>in</strong>al surgery.<br />

On physical exam<strong>in</strong>ation, the abdomen was distended<br />

and with dim<strong>in</strong>ished bowel sounds. On admission the<br />

laboratory data revealed <strong>in</strong>creased serum levels <strong>of</strong> amylase<br />

549 U/L, glucose 166 mg/dL, WBC 14,400, bilirub<strong>in</strong> 4.2 mg/<br />

dL. Except a calcium value <strong>of</strong> 12 mg/dL, all other laboratory<br />

exam<strong>in</strong>ations were normal. Abdom<strong>in</strong>al ultrasonography<br />

showed pancreatic oedema and ruled out gallstones,<br />

cysts and <strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al obstruction. No biliary dilatation was<br />

observed. <strong>Drug</strong>-<strong>in</strong>duced pancreatitis was considered after<br />

exclusion <strong>of</strong> other causes (alcohol <strong>in</strong>take, cholelithiasis,<br />

hyperlipidemia, abdom<strong>in</strong>al trauma). Hydrochlorothiazide<br />

was the suspected drug and it was discont<strong>in</strong>ued. A mild drug<br />

<strong>in</strong>duced hypercalcemia was also considered, alfacalcidol<br />

and calcium be<strong>in</strong>g stopped until the serum levels became<br />

normocalcemic. The patient received symptomatic medical<br />

treatment. The cl<strong>in</strong>ical status <strong>of</strong> the patient improved with<strong>in</strong><br />

48 hours after the discont<strong>in</strong>uation <strong>of</strong> hydrochlorothiazide.<br />

On hospital day 3 serum amylase levels returned to normal<br />

and on day 5 the patient was discharged.<br />

Case discussion<br />

Thiazide diuretics <strong>in</strong> normal doses have been reported<br />

to be associated with pancreatitis which develops with<strong>in</strong>

<strong>Adverse</strong> drug reactions <strong>in</strong> cl<strong>in</strong>ical practice 357<br />

Table II. Factors predispos<strong>in</strong>g patients to ADRs<br />

Pharmacodynamic factors<br />

Variation <strong>in</strong> receptor sensitivity<br />

Pharmacok<strong>in</strong>etic factors<br />

Absorption<br />

Distribution<br />

Metabolism<br />

Excretion<br />

Concurrent disease<br />

Renal impairment<br />

Hepatic impairment<br />

Congestive heart failure<br />

<strong>Drug</strong> <strong>in</strong>teractions<br />

Physiologic conditions<br />

Age<br />

Pregnancy<br />

Obesity<br />

Lifestyle factors<br />

Alcohol <strong>in</strong>take<br />

Smok<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Genetic variability (genetic polymorphism)<br />

Adherence to prescribed therapy<br />

Medication errors<br />

Panel 2. Naranjo probability scale<br />

1. Are there previous conclusive reports on<br />

this reaction?<br />

2. Did the adverse reaction appear after the<br />

suspected drug was adm<strong>in</strong>istered?<br />

3. Did the adverse reaction improve when<br />

the drug was discont<strong>in</strong>ued or a specific<br />

antagonist was adm<strong>in</strong>istered?<br />

4. Did the adverse reaction reappear when<br />

the drug was readm<strong>in</strong>istered?<br />

5. Are there alternative causes that could on<br />

their own have caused the reaction?<br />

6. Did the reaction reappear when a placebo<br />

was given?<br />

7. Was the drug detected <strong>in</strong> the blood (or<br />

other fluids) <strong>in</strong> concentrations known to be<br />

toxic?<br />

8. Was the reaction more severe when the<br />

dose was <strong>in</strong>creased or less severe when the<br />

dose was decreased?<br />

9. Did the patient have a similar reaction<br />

to the same or similar drug <strong>in</strong> any previous<br />

exposure?<br />

10. Was the adverse event confirmed by<br />

any objective evidence?<br />

Yes No Don’t<br />

know<br />

+1 0 0<br />

+2 -1 0<br />

+1 0 0<br />

+2 -1 0<br />

-1 +2 0<br />

-1 +1 0<br />

+1 0 0<br />

+1 0 0<br />

+1 0 0<br />

+1 0 0<br />

SCORE 9 = def<strong>in</strong>ite; 5-8 = probable; 1-4 = possible; 0 = doubtful<br />

two weeks to as long as 1 year after <strong>in</strong>itiation <strong>of</strong> the<br />

therapy. Several potential mechanisms <strong>of</strong> thiazide-<strong>in</strong>duced<br />

pancreatitis have been suggested <strong>in</strong> the literature. Thiazides<br />

Panel 3. Causality assessment <strong>of</strong> the pancreatitis case<br />

us<strong>in</strong>g the Naranjo probability scale<br />

1. There are conclusive reports on this adverse reaction<br />

as thiazide diuretics agents are known to produce<br />

pancreatitis; we found several case <strong>of</strong> pancreatitis<br />

associated with hydrochlorothiazide<br />

2. Hydrochlorothiazide, the suspected drug, was<br />

adm<strong>in</strong>istered dur<strong>in</strong>g the previous six months before the<br />

sudden onset <strong>of</strong> the adverse reaction<br />

3. The adverse reaction improved with<strong>in</strong> the 48 hours<br />

after the discont<strong>in</strong>uation <strong>of</strong> the drug<br />

4. There is no <strong>in</strong>formation about the reappearance <strong>of</strong> the<br />

drug-<strong>in</strong>duced pancreatitis <strong>in</strong> this patient as rechallenge<br />

was not performed<br />

Score<br />

5. The alternative causes for pancreatitis were ruled out +2<br />

6. A placebo was not given to the patient, the answer is<br />

“don’t know” <strong>in</strong> this case<br />

7. This analysis (drug’s plasmatic concentration) was<br />

not performed <strong>in</strong> this case, the answer is “don’t know”<br />

8. The dose was neither decreased nor <strong>in</strong>creased so we<br />

don’t know the evolution <strong>of</strong> the reaction <strong>in</strong> this case<br />

9. There is no past history <strong>of</strong> any similar reaction to the<br />

same or similar drugs<br />

10. The adverse reaction was documented by relevant<br />

laboratory tests<br />

Total score +7<br />

Category<br />

+1<br />

+2<br />

+1<br />

0<br />

0<br />

0<br />

0<br />

0<br />

+1<br />

Probable<br />

can cause hypercalcemia by decreas<strong>in</strong>g renal calcium<br />

excretion. Hypercalcemia is a condition known to <strong>in</strong>crease<br />

the risk <strong>of</strong> pancreatitis which may lead to calculi with<strong>in</strong> the<br />

pancreatic duct and/or may accelerate the conversion <strong>of</strong><br />

tryps<strong>in</strong>ogen to tryps<strong>in</strong> [20]. At the same time, hypercalcemia<br />

is a predom<strong>in</strong>ant adverse effect associated with alfacalcidol,<br />

which <strong>in</strong> this patient has been adm<strong>in</strong>istered <strong>in</strong> a high<br />

dose; the effect usually reverses rapidly on withdrawal <strong>of</strong><br />

the drug. A probable drug-drug <strong>in</strong>teraction may also be<br />

suspected to have <strong>in</strong>creased the calcium serum levels, as<br />

the concurrent use <strong>of</strong> calcium-conta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g preparations and<br />

thiazide diuretics enhance the risk <strong>of</strong> hypercalcemia. Another<br />

drug <strong>in</strong>teraction, with no relation to pancreatitis, but which<br />

should be underl<strong>in</strong>ed and considered <strong>in</strong> this case, is digox<strong>in</strong><br />

– hydrochlorothiazide <strong>in</strong>teraction which may lead to digitalis<br />

toxicity with nausea, vomit<strong>in</strong>g and arrhythmias. If a digitalis<br />

glycoside and a thiazide diuretic are used concurrently, the<br />

patient should be monitored for ECG signs <strong>of</strong> potassium<br />

depletion, and potassium supplementation should be<br />

considered. The causality assessment <strong>of</strong> this adverse event,<br />

presented <strong>in</strong> Panel 3, revealed a probable association between<br />

hydrochlorothiazide and pancreatitis as rechallenge was<br />

not performed. In a drug-<strong>in</strong>duced pancreatitis case, patients<br />

should never be rechallenged with any drug that has caused<br />

even one episode <strong>of</strong> pancreatitis [20].<br />

Conclusions<br />

Prompt recognition <strong>of</strong> adverse drug reactions, adequate<br />

and effective cl<strong>in</strong>ical management <strong>of</strong> their outcome

358<br />

is mandatory <strong>in</strong> promot<strong>in</strong>g patients’ safety. Health<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>essionals who care for patients’ drug therapy are taught<br />

to consider as well the benefit as the risk when mak<strong>in</strong>g<br />

therapeutic choices. The tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g regard<strong>in</strong>g adverse events<br />

is <strong>of</strong>ten limited, consider<strong>in</strong>g the reality that expected (due to<br />

pharmacologic action) or unexpected (due to idiosyncratic<br />

reactions) adverse drug reactions, if not recognised, can<br />

<strong>in</strong>crease the risk <strong>of</strong> harm. Several aspects should be taken<br />

<strong>in</strong>to consideration <strong>in</strong> order to recognize and properly manage<br />

adverse drug reactions. The first is that careful observation<br />

and high cl<strong>in</strong>ical suspicion are <strong>of</strong> crucial importance <strong>in</strong><br />

order to identify a drug related problem, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g adverse<br />

drug reactions. The second is that, even though a drug has<br />

been on the market for several years, is widely used and<br />

with known side effects pr<strong>of</strong>ile, unusual adverse reactions<br />

may still be identified. Tak<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>to account all these aspects<br />

will lead to better adverse drug reaction management and<br />

<strong>in</strong>creased patients’ safety.<br />

Conflicts <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>terest<br />

None to declare.<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

The documentation for this study was supported by<br />

a research grant f<strong>in</strong>anced by the Romanian M<strong>in</strong>istry <strong>of</strong><br />

Education and Research – PNII Partnership <strong>in</strong> Prioritary<br />

Issues 12-102 / 2008<br />

References<br />

1. Pirmohamed M, James S, Meak<strong>in</strong> S, et al. <strong>Adverse</strong> drug reaction<br />

as cause <strong>of</strong> admission to hospital: prospective analysis <strong>of</strong> 18 820<br />

patients. BMJ 2004; 329: 15-19.<br />

2. Lazarou J, Pomeranz B, Corey PN. Incidence <strong>of</strong> adverse drug<br />

reactions <strong>in</strong> hospitalized patients. A meta-analysis <strong>of</strong> prospective<br />

studies. JAMA 1998; 279: 1200-1205.<br />

3. Dormann H, Muth-Selbach U, Krebs S, et al. Incidence and costs<br />

<strong>of</strong> adverse drug reactions dur<strong>in</strong>g hospitalization: computerized<br />

monitor<strong>in</strong>g versus stimulated spontaneous report<strong>in</strong>g. <strong>Drug</strong> Saf 2000;<br />

22: 161-168.<br />

4. Rodriguez-Monguio R, Otero MJ, Rovira J. Assess<strong>in</strong>g the economic<br />

impact <strong>of</strong> adverse drug effects. Pharmacoeconomics 2003; 21: 623-<br />

650.<br />

5. Dormann H, Criegee-Rieck M, Neubert A, et al. Lack <strong>of</strong> awareness <strong>of</strong><br />

community-acquired adverse drug reactions upon hospital admission.<br />

<strong>Drug</strong> Saf 2003; 26: 353-362.<br />

6. The use <strong>of</strong> the WHO–UMC system for standardised case causality<br />

assessment. Accessed at http://www.who-umc.org/graphics/4409.<br />

pdf on February, 28th, 2009.<br />

7. Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, et al. A method for estimat<strong>in</strong>g the<br />

probability <strong>of</strong> adverse drug reactions. Cl<strong>in</strong> Pharmacol Ther 1981;<br />

30: 239–245.<br />

8. L<strong>in</strong>dquist M. The need for def<strong>in</strong>itions <strong>in</strong> pharmacovigilance. <strong>Drug</strong><br />

Saf 2007; 30: 825-830.<br />

Farcas et al<br />

9. Edwards IR, Aronson JK. <strong>Adverse</strong> drug reactions: def<strong>in</strong>itions,<br />

diagnosis, and management. Lancet 2000; 356:1255–1259.<br />

10. Cl<strong>in</strong>ical safety data management: def<strong>in</strong>itions and standards for<br />

expedited report<strong>in</strong>g. London: European Agency for the Evaluation<br />

<strong>of</strong> Medic<strong>in</strong>al Products, Human Medic<strong>in</strong>es Evaluation Unit; 1995.<br />

Accessed at www.emea.eu.<strong>in</strong>t/pdfs/human/ich/037795en.pdf.<br />

11. WHO safety <strong>of</strong> medic<strong>in</strong>es. A guide to detect<strong>in</strong>g and report<strong>in</strong>g adverse<br />

drug reactions. Why health pr<strong>of</strong>essionals need to take action. Geneva:<br />

World Health Organization; 2002. WHO/EDM/QSM/2002.2.<br />

12. Atuah KN, Hughes D, Pirmohamed M. Cl<strong>in</strong>ical pharmacology: special<br />

safety considerations <strong>in</strong> drug development and pharmacovigilance.<br />

<strong>Drug</strong> Saf 2004; 27: 535-554.<br />

13. Meyboom RH, L<strong>in</strong>dquist M, Egberts AC. An ABC <strong>of</strong> drug-related<br />

problems. <strong>Drug</strong> Saf 2000; 22: 415-423.<br />

14. Mann RD, Andrews EB. Pharmacovigilance. 2nd Edn, Chichester,<br />

UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2007.<br />

15. Talbot J, Waller P. Stephens: Detection <strong>of</strong> New <strong>Adverse</strong> <strong>Drug</strong><br />

<strong>Reactions</strong>. 5th Edn, Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, 2004.<br />

16. Rehan HS, Chopra D, Kakkar AK. Physician’s guide to<br />

pharmacovigilance: term<strong>in</strong>ology and causality assessment. Eur J<br />

Intern Med 2009; 20: 3-8.<br />

17. Jaquenoud Sirot E, Van der Velden JW, Rentsch K, Eap CB, Baumann<br />

P. Therapeutic drug monitor<strong>in</strong>g and pharmacogenetic tests as tools<br />

<strong>in</strong> pharmacovigilance. <strong>Drug</strong> Saf 2006; 29: 735-768.<br />

18. Meyboom RH, L<strong>in</strong>dquist M, Flygare AK, Biriell C, Edwards IR.<br />

The value <strong>of</strong> report<strong>in</strong>g therapeutic <strong>in</strong>effectiveness as an adverse drug<br />

reaction. <strong>Drug</strong> Saf 2000; 23: 95-99.<br />

19. Irey NS. Diagnostic problems <strong>in</strong> drug-<strong>in</strong>duced diseases. Ann Cl<strong>in</strong><br />

Lab Sci. 1976; 6: 272-277.<br />

20. Tisdale JE, Miller DA. <strong>Drug</strong>-Induced Diseases. Prevention,<br />

Detection and Management. Bethesda, Maryland: American Society<br />

<strong>of</strong> Health-System Pharmacists Press, 2005.<br />

21. Atk<strong>in</strong> PA, Veitch PC, Veitch EM, Ogle SJ. The epidemiology <strong>of</strong><br />

serious adverse drug reactions among the elderly. <strong>Drug</strong>s Ag<strong>in</strong>g 1999;<br />

14: 141-152.<br />

22. Passarelli MC, Jacob-Filho W, Figueras A. <strong>Adverse</strong> drug reactions<br />

<strong>in</strong> an elderly hospitalised population: <strong>in</strong>appropriate prescription is<br />

a lead<strong>in</strong>g cause. <strong>Drug</strong>s Ag<strong>in</strong>g 2005; 22: 767-777.<br />

23. Köhler GI, Bode-Böger SM, Busse R, Hoopmann M, Welte T, Böger<br />

RH. <strong>Drug</strong>-drug <strong>in</strong>teractions <strong>in</strong> medical patients: effects <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>-hospital<br />

treatment and relation to multiple drug use. Int J Cl<strong>in</strong> Pharmacol Ther<br />

2000; 38: 504-513.<br />

24. Laroche ML, Charmes JP, Nouaille Y, Fourrier A, Merle L. Impact<br />

<strong>of</strong> hospitalisation <strong>in</strong> an acute medical geriatric unit on potentially<br />

<strong>in</strong>appropriate medication use. <strong>Drug</strong>s Ag<strong>in</strong>g 2006; 23: 49-59.<br />

25. Jonville-Bera AP, Bera F, Autret-Leca E. Are <strong>in</strong>correctly used drugs<br />

more frequently <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> adverse drug reactions? A prospective<br />

study. Eur J Cl<strong>in</strong> Pharmacol 2005; 61: 231–236.<br />

26. Rieger K, Scholer A, Arnet I, et al. High prevalence <strong>of</strong> unknown<br />

co-medication <strong>in</strong> hospitalised patients. Eur J Cl<strong>in</strong> Pharmacol 2004;<br />

60: 363–368.<br />

27. Brewer T, Colditz GA. Postmarket<strong>in</strong>g surveillance and adverse drug<br />

reactions. current perspectives and future needs. JAMA 1999; 281:<br />

824-829.<br />

28. Nebeker JR, Barach P, Samore MH. Clarify<strong>in</strong>g adverse drug events:<br />

a cl<strong>in</strong>ician’s guide to term<strong>in</strong>ology, documentation, and report<strong>in</strong>g. Ann<br />

Intern Med 2004; 140: 795-801.