Management of Boerhaave's Syndrome: Report of Three ... - rjge.ro

Management of Boerhaave's Syndrome: Report of Three ... - rjge.ro

Management of Boerhaave's Syndrome: Report of Three ... - rjge.ro

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<st<strong>ro</strong>ng>Management</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> Boerhaave’s <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>Synd<strong>ro</strong>me</st<strong>ro</strong>ng>: <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>Report</st<strong>ro</strong>ng><br />

<st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>Three</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> Cases<br />

Konstantinos Tsalis, Konstantinos Vasiliadis, Theodor Tsachalis, Emmanuel Christ<st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng>oridis,<br />

Konstantinos Blouhos, Dimitrios Betsis<br />

4 th Surgical Department, Aristotle University <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> Thessaloniki, Exohi 570 10, Thessaloniki, Greece<br />

Abstract<br />

F<strong>ro</strong>m 2000 to 2005, three patients with Boerhaave’s<br />

synd<strong>ro</strong>me were successfully managed in our Department.<br />

Two <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> them received the app<strong>ro</strong>priate treatment belatedly,<br />

with primary closure and bolstering tissue wrap. One <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> them<br />

required further intervention with a cervical esophagostomy<br />

and exclusion <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> the perforated esophagus. The third<br />

patient with an esophageal perforation related disorder,<br />

was managed with surgical exploration and drainage alone.<br />

Primary suturing <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> the esophagus should be performed only<br />

in patients with an early perforation. In cases <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> p<strong>ro</strong>longed<br />

delay between rupture and diagnosis, esophageal resection<br />

with cervical esophagostomy and gast<strong>ro</strong>stomy is advocated<br />

as the safest therapy.<br />

Key words<br />

Primary esophageal perforation - Boerhaave’s synd<strong>ro</strong>me<br />

- current treatment<br />

Int<strong>ro</strong>duction<br />

Boerhaave’s synd<strong>ro</strong>me represents the most sinister cause<br />

<st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> esophageal perforation [1]. It remains a potentially lethal<br />

complication, and is still associated with a high mortality rate<br />

[1-6]. Classical presentation <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> this synd<strong>ro</strong>me is vomiting,<br />

chest pain, and subcutaneous emphysema. However, this<br />

triad, first described by Mackler [3] is seldom found. Delay<br />

in diagnosis is common, resulting in substantial mortality.<br />

Some authors report mortality figures more than 65% after<br />

24 hours and 75-89% after 48 hours [1,2,4].<br />

The general consensus, concerning the management <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng><br />

this synd<strong>ro</strong>me, is early diagnosis and timely inhibition <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> the<br />

J Gast<strong>ro</strong>intestin Liver Dis<br />

March 2008 Vol.17 No 1, 81-85<br />

Address for correspondence:<br />

K. Vasiliadis<br />

Dorileou 3<br />

55133 Kalamaria<br />

Thessaloniki, Greece<br />

E-mail: keva@med.auth.gr<br />

fatal esophageal injury-induced inflammatory p<strong>ro</strong>cess[1,7-<br />

10]. Nevertheless, the optimal therapeutic app<strong>ro</strong>ach remains<br />

cont<strong>ro</strong>versial. Indeed, divergent therapeutic app<strong>ro</strong>aches<br />

have been reported with significant variance in outcome<br />

and complications, with mortality rates ranging f<strong>ro</strong>m<br />

3% to more than 50% [1]. The aim <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> this study is to<br />

present our experience on diagnosis and management <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng><br />

spontaneous esophageal rupture and assess the current<br />

management status according to recent literature data.<br />

Case report<br />

F<strong>ro</strong>m 2000 to 2005, three consecutive spontaneous<br />

esophageal perforations were managed in our Department.<br />

All were men, aged between 32 and 47 years. Clinical<br />

presentation, radiographic findings, localization <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> rupture,<br />

degree <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> contamination in the thorax, days f<strong>ro</strong>m admission<br />

till operation, treatment method, complications, the period<br />

<st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> admission and ICU stay are listed in Table I.<br />

Patient 1<br />

A 42-year-old man, with a history <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> organic psychosynd<strong>ro</strong>me<br />

and pyloric channel stricture secondary to ch<strong>ro</strong>nic<br />

duodenal ulcer, was transferred to our Department after a<br />

spontaneous esophageal rupture that had been diagnosed<br />

elsewhere. The original diagnosis was delayed because mid<br />

epigastric and lower thoracic pain after forcible c<st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng>fee-g<strong>ro</strong>und<br />

emesis was misinterpreted as an upper gast<strong>ro</strong>intestinal (GI)<br />

tract hemorrhage. On the fifth day <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> hospitalisation, after<br />

a hemorrhage relapse along with hemodynamic instability<br />

and systemic septic clinical signs, the patient underwent<br />

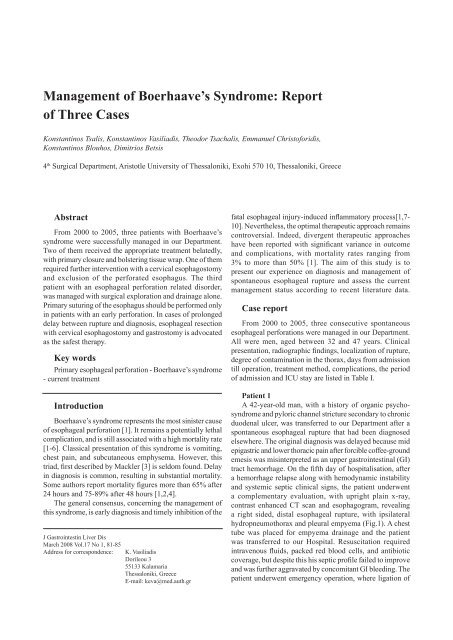

a complementary evaluation, with upright plain x-ray,<br />

contrast enhanced CT scan and esophagogram, revealing<br />

a right sided, distal esophageal rupture, with ipsilateral<br />

hyd<strong>ro</strong>pneumothorax and pleural empyema (Fig.1). A chest<br />

tube was placed for empyema drainage and the patient<br />

was transferred to our Hospital. Resuscitation required<br />

intravenous fluids, packed red blood cells, and antibiotic<br />

coverage, but despite this his septic pr<st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng>ile failed to imp<strong>ro</strong>ve<br />

and was further aggravated by concomitant GI bleeding. The<br />

patient underwent emergency operation, where ligation <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng>

82 Tsalis et al<br />

Table I Characteristics, treatment and outcome <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> patients who suffered spontaneous esophageal rupture<br />

Pt<br />

Sex/Age<br />

Chief<br />

complaints<br />

Time f<strong>ro</strong>m<br />

onset till<br />

surgery<br />

Imaging studies<br />

Chest X-ray CT Esophgography<br />

Location <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng><br />

rupture<br />

Surgical p<strong>ro</strong>cedure<br />

1M 42<br />

Postemetic, midepigastric,<br />

lower<br />

thoracic pain, dyspnea<br />

5 days<br />

Right hyd<strong>ro</strong>- Right Leakage into<br />

pneumo- pleural right pleural<br />

thorax empyema cavity<br />

Right side<br />

wall <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> LTE<br />

Right thoracotomydrainge,<br />

lapa<strong>ro</strong>tomybleeding<br />

duodenal ulcer<br />

oversewing-pylo<strong>ro</strong>plasty<br />

2M 32<br />

Postemetic lower<br />

thoracic pain,<br />

dyspnea, subcutaneous<br />

emphysema<br />

>25 hours<br />

Bilateral Bilateral Leakage<br />

pleural pleural into left<br />

effusion effusion pleural cavity<br />

Left side wall<br />

<st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> LTE<br />

Bilateral thoracotomiesdrainage,<br />

primary<br />

closure<br />

3M 47<br />

Postemetic midepigastric<br />

and back<br />

pain, dyspnea<br />

12 hours<br />

Pneumo- Left Leakage into<br />

mediastinum pleural left pleural<br />

effusion cavity<br />

Left side wall<br />

<st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> LTE<br />

Left thoracotomydrainage,lapa<strong>ro</strong>tomyprimary<br />

closure+foundoplication<br />

M=Male, LTE=Lower Thoracic Esophagus, SECMS=Self-Expandable Covered Metallic Stent, CT=Computed Tomography<br />

Subsequent p<strong>ro</strong>cedures<br />

Esophageal<br />

SECMS<br />

Cervical esophagostomy,<br />

esophageal exclusion,<br />

gast<strong>ro</strong>stomy, feeding<br />

jejunostomy, continuous<br />

pleural irrigation.<br />

Delayed esophageal<br />

reconstruction with left<br />

colic flexure<br />

None<br />

ICU<br />

stay<br />

10 days<br />

35 days<br />

2 days<br />

Time <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng><br />

discharge<br />

15 weeks<br />

9 weeks<br />

5 weeks

Boerhaave’s synd<strong>ro</strong>me 83<br />

Fig.1 Patient 1.Upright plain x-ray (a), esophagogram (b), and<br />

contrast enhanced CT scan (c) revealing a right sided, distal<br />

esophageal rupture, with ipsilateral hyd<strong>ro</strong>pneumothorax and<br />

pleural empyema.<br />

a bleeding vessel in the duodenal ulceration, pylo<strong>ro</strong>plasty,<br />

draining gast<strong>ro</strong>stomy and feeding jejunostomy were<br />

fashioned via an upper midline lapa<strong>ro</strong>tomy. Additionally, a<br />

right thoracotomy for better drainage and lavage <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> the right<br />

thoracic cavity was performed and the chest was closed with<br />

two large thoracostomy tubes in situ. A hypaque swallow<br />

study, on the 4th postoperative week demonstrated closure<br />

<st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> the esophageal rent but revealed the development <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> a<br />

stricture along the lower third <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> the esophagus, which p<strong>ro</strong>ved<br />

to be refractory to multiple endoscopic dilatations performed<br />

between the 9th and 11th postoperative weeks. The patient<br />

was considered to be unfit for esophageal replacement and in<br />

addition he was reluctant to undergo any major intervention.<br />

Hence, a covered self-expanding metallic stent (Ultraflex,<br />

Boston Scientific) was inserted on the 12th postoperative<br />

week, endoscopically. During the follow-up period he was<br />

able to eat normally and maintain his weight. He survived<br />

for 3 years and finally died <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> a severe depression disorder.<br />

Patient 2<br />

A 32-year-old man, with no history <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> previous illness<br />

but with an ambiguous reference to recent food and drink<br />

overindulgence, was presented to a peripheral Hospital<br />

Emergency department complaining <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> the sudden onset<br />

<st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> gradually increasing, lower thorax post emetic pain and<br />

subcutaneous emphysema. The suspicion <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> spontaneous<br />

esophageal rupture was confirmed on a subsequent erect<br />

x-ray film, CT scan and esophagogram by the presentation<br />

<st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> bilateral pleural effusion together with left sided contrast<br />

extravasation f<strong>ro</strong>m the lower third <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> the esophagus (Fig.2).<br />

Fig.2 Patient 2. Esophagogram depicting a leftsided<br />

leak.<br />

Bilateral thoracotomies, closure <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> the esophageal<br />

perforation in two layers, buttress <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> the defect with viable<br />

regional pleural flap and placement <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> chest tubes were<br />

performed. Subsequently, the patient was transferred to<br />

our department because <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> lack <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> ICU. On postoperative<br />

day 8, the patient demonstrated clinical signs <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> a recurrent<br />

leak, with recrudescing systemic sepsis, dyspnea, and<br />

hemodynamic instability. The subsequent CT scan study<br />

demonstrated contrast medium extravasation accompanied<br />

with large pleural effusion bilaterally. Re-operation was<br />

considered inevitable, during which mediastinum and pleural<br />

debridement, forcible irrigation <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> pleural spaces, cervical<br />

esophagostomy in combination with closure <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> the distal<br />

esophagus, feeding jejunostomy and draining gast<strong>ro</strong>stomy,<br />

were performed. Postoperatively, thoracotomies were left<br />

opened and continuous irrigation systems were applied to our<br />

patient’s thoracic wounds [6]. The patient had a p<strong>ro</strong>longed<br />

ICU stay, mainly because <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> the need for ventilation, as a<br />

result <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> severe pneumonitis, along with relapsing incidences<br />

<st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> systemic sepsis. Eventually, he was returned to the main<br />

ward on the 5th postoperative week. After a total period <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng><br />

14 weeks, the patient was discharged, continuing total enteral<br />

alimentation. Five months later, he underwent reconstruction<br />

by joining the cervical esophagus to the stomach using<br />

ret<strong>ro</strong>sternal left colic flexure based on the left branch <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> the<br />

middle colic vessels. He can now eat normally and maintain<br />

his weight and is leading a normal existence.<br />

Patient 3<br />

A 47-year-old man, with no history <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> previous illness,<br />

and with reference to a preceding overindulgence in a<br />

large meal, presented to our Department, complaining <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng>

84 Tsalis et al<br />

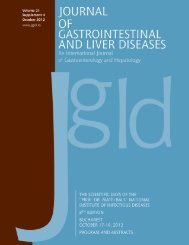

Fig.3 Patient 3. Contrast enhanced CT scan, demonstrating<br />

significant mediastinal free air, and extended left sided<br />

pleural effusion.<br />

the sudden onset <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> a sharp, post emetic, mid epigastric<br />

pain, radiating to the left shoulder. On the basis <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> classic<br />

esophageal rupture history, the diagnosis was readily made<br />

by means <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> erect chest x-ray and CT (Fig.3). A confirmative<br />

subsequent hypaque swallow study demonstrated small<br />

extravasation <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> contrast medium f<strong>ro</strong>m a distal esophageal<br />

perforation. After a short resuscitation period, the patient<br />

was transferred to the Operating Theatres, where the<br />

rupture site, located on the left esophageal wall next to the<br />

gast<strong>ro</strong>esophageal junction, was app<strong>ro</strong>ached with midline<br />

lapa<strong>ro</strong>tomy. A primary esophageal closure in two layers with<br />

additional fundoplication was performed. Furthermore, a<br />

small left thoracotomy was performed and the thoracic cavity<br />

was copiously irrigated. Finally the chest was closed with<br />

a large (32-gauge) thoracostomy tube in situ. On the third<br />

postoperative day the patient was returned to the main ward<br />

where repeated esophageal contrast medium studies verified<br />

a successful outcome. On postoperative day 15 the patient<br />

began oral feeding. Five weeks after surgery, the patient was<br />

discharged in good general condition. At the time <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> writing,<br />

6 years after the initial operation, he continues to do well.<br />

Discussion<br />

The presentation <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> Boerhaave’s synd<strong>ro</strong>me is usually nonspecific<br />

and may mimic many other clinical disorders [11].<br />

Our diagnostic tools were chest X-ray, CT, esophagography,<br />

and esophagoscopy, but principally a high index <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> suspicion<br />

is required for timely diagnosis. In our cases, CT scans were<br />

done immediately after oral contrast administration, to detect<br />

the level and size <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> perforation and define the sur<strong>ro</strong>unding<br />

tissue inflammation, which helped as in deciding on the most<br />

app<strong>ro</strong>priate therapy [12,13].<br />

The management <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> the synd<strong>ro</strong>me remains cont<strong>ro</strong>versial<br />

since treatment can be surgical or non-surgical, and indications<br />

vary according to the functional state <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> the esophagus, the<br />

presence <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> associated lesions and the habits <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> the different<br />

medical teams [1,9,14]. Today, it is accepted that the method<br />

<st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> treatment plays an important <strong>ro</strong>le in the mortality rate<br />

and although surgery has been the most common app<strong>ro</strong>ach,<br />

the selection criteria for conservative treatment reported by<br />

Altorjay et al [15] (intramural perforation, benign defects,<br />

and the absence <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> sepsis) in 1977, and Came<strong>ro</strong>n et al [16]<br />

in 1979 (disruption contained in the mediastinum; the cavity<br />

draining back into the esophagus; minimal symptoms; and<br />

minimal signs <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> sepsis), are still valid and should be taken<br />

into account. With reference to the above, perforations<br />

and pleural contamination, once cont<strong>ro</strong>lled by adequate<br />

drainage, simply become an esophagocutaneous fistula and<br />

will heal the same as most gast<strong>ro</strong>intestinal fistulas [17].<br />

Recently, some authors claimed that rapid closure <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> the<br />

esophageal leak and drainage, could also be achieved by<br />

the minimal invasive endoscopic app<strong>ro</strong>ach by inserting an<br />

endop<strong>ro</strong>sthesis, followed by interventional drainage and/or<br />

thoracoscopic irrigation <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> the contaminated thoracic cavity<br />

[18-20]. Nevertheless, we believe that this app<strong>ro</strong>ach can be<br />

applied only for iat<strong>ro</strong>genic and early detected perforations.<br />

A self-expandable covered metallic esophageal stent<br />

was placed in one <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> our patients in order to treat a distal<br />

esophageal post perforation stricture. Esophageal stenting<br />

for non-malignant strictures is cont<strong>ro</strong>versial. The covered<br />

self-expanding metallic stent was originally used for the<br />

stricture or fistula caused by malignant diseases [18]. On the<br />

other hand, many authors investigated the application <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> this<br />

alternative method to the management <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> benign conditions<br />

[21]. In our case, stent placement was used mainly because<br />

<st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> the patient’s refusal for further invasive p<strong>ro</strong>cedure, as well<br />

as considering his moderate medical condition.<br />

There is still cont<strong>ro</strong>versy about the most app<strong>ro</strong>priate<br />

type <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> surgery for patients with esophageal perforation.<br />

Some surgeons performed primary repair, regardless <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> the<br />

interval between the perforation and intervention, resulting<br />

in a diverse outcome [8,10]. Our opinion on primary<br />

repair is that it is better to be avoided in delayed patients.<br />

Conversely, if the inflammatory p<strong>ro</strong>cess is limited, primary<br />

repair is a reasonable option and may result in an excellent<br />

outcome [10]. Some others suggest that esophagectomy<br />

may be better f<strong>ro</strong>m primary repair for patients with delayed<br />

perforation, because <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> the high risk <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> leakage [1,22].<br />

We believe that primary reconstruction must be the first<br />

treatment option in stable, nonseptic patients. Debridement<br />

and drainage with or without continuous lavage [23, 24] is<br />

another option, especially if the patient’s general condition<br />

is impaired or p<strong>ro</strong>gressive sepsis is apparent. We applied this<br />

method in one <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> our patients with satisfactory results. If the<br />

interval between injury and intervention exceeds 24h or CT<br />

shows signs <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> p<strong>ro</strong>gressive periesophageal inflammation,<br />

reinforcement <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> the esophageal repair by viable regional<br />

tissue is recommended [11].<br />

If delayed reconstruction is being considered, it is<br />

possible to bring up the stomach, the small intestine or<br />

the colon to join the cervical esophagus. The timing <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng><br />

reconstruction must be based on the patient’s condition or/and<br />

recovery. Reconstruction <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> the esophagus can be performed<br />

simultaneously if there is no severe systemic inflammatory<br />

response. Otherwise, delayed reconstruction (2-4 months)<br />

is possibly the best option [1]. The new esophagus can be

Boerhaave’s synd<strong>ro</strong>me 85<br />

placed in the posterior mediastinum or in the ret<strong>ro</strong>sternal<br />

or subcutaneous positions. In patient 2 delayed esophageal<br />

reconstruction was performed with colonic graft positioned<br />

ret<strong>ro</strong>sternally in order to achieve a better cosmetic result.<br />

All our patients were surgically treated after resuscitative<br />

measures such as fluids and antibiotics. Our intention<br />

was to prevent ongoing spoilage, to p<strong>ro</strong>vide debridement<br />

<st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> devitalized tissue and to perform wide drainage.<br />

Postoperatively, all patients received supportive management<br />

including nasogastric tube decompression <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> the stomach,<br />

b<strong>ro</strong>ad-spectrum antibiotic administration, and nutrition.<br />

In conclusion, without treatment, patients with esophageal<br />

rupture frequently die <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> mediastinitis. Because <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> the very<br />

small numbers <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> cases, no standard therapy has been<br />

established. Conservative treatment remains a cont<strong>ro</strong>versial<br />

topic, although recent sporadic reports have documented<br />

the efficacy <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> nonoperative care, especially following<br />

perforations in nonseptic patients. Primary suturing <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> the<br />

esophagus should be performed only in patients with an<br />

early perforation. When ongoing mediastinitis and pleural<br />

contamination has occurred, only esophageal exclusion or<br />

resection can definitely eliminate the source <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> intrathoracic<br />

sepsis.<br />

References<br />

1. Huber-Lang M, Henne–Bruns D, Schmitz B, Wuerl P. Esophageal<br />

perforation: principles <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> diagnosis and surgical management. Surg<br />

Today 2006; 36:332-340.<br />

2. Lawrence DR, Ohri SK, Moxon RE, Townsend ER, Fountain SW.<br />

Primary esophageal repair for Boerhaave’s synd<strong>ro</strong>me. Ann Thorac<br />

Surg 1999; 67:818-812.<br />

3. Mackler SA. Spontaneous rupture <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> the esophagus; an experimental<br />

and clinical study. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1952; 95:345-356.<br />

4. Pate JW, Walker WA, Cole FH Jr, Owen EW, Johnson WH.<br />

Spontaneous rupture <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> the esophagus: a 30-year experience. Ann<br />

Thorac Surg 1989; 47: 689-692.<br />

5. Hafer G, Haunhorst WH, Stallkamp B. Atraumatic rupture <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> the<br />

esophagus (Boerhaave synd<strong>ro</strong>me). Zentralbl Chir 1990; 115: 729-<br />

735.<br />

6. XWitte J, Pratschke E. Esophageal perforation. In: Baue A D,<br />

ed. Glenn’s Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. Norwalk, CT:<br />

Appleton and Lange, 1991: 669.<br />

7. Lundell L, Liedman B, Hyltander A. Emergency oeso-phagectomy<br />

and p<strong>ro</strong>ximal deviating oesophagostomy for fulminent mediastinal<br />

sepsis. Eur J Surg 2001; 167:675-678.<br />

8. Sung SW, Park JJ, Kim YT, Kim JH. Surgery in thoracic esophageal<br />

perforation: primary repair is feasible. Dis Esophagus 2002; 15:204-<br />

209.<br />

9. Ökten I, Cangir AK, Özdemir N, Kavukcu S, Akay H, Yavuzer S.<br />

<st<strong>ro</strong>ng>Management</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> esophageal perforation. Surg Today 2001; 31:36-<br />

39.<br />

10. Port JL, Kent MS, Korst RJ, Bacchetta M, Altorki NK. Thoracic<br />

esophageal perforations: a decade <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> experience. Ann Thorac Surg<br />

2003; 75:1071-1074.<br />

11. Henderson JA, Peloquin AJ. Boerhaave revisited: spontaneous<br />

esophageal perforation as a diagnostic masquerader. Am J Med 1989;<br />

86:559-567.<br />

12. Akman C, Kantarci F, Cetinkaya S. Imaging in mediastinitis: a<br />

systematic review based on aetiology. Clin Radiol 2004; 59:573-<br />

585.<br />

13. Fadoo F, Ruiz DE, Dawn SK, Webb WR, Gotway MB. Helical<br />

CT esophagography for the evaluation <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> suspected esophageal<br />

perforation. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2004; 182:1177-1179.<br />

14. Chao YK, Liu YH, Ko PJ, et al. Treatment <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> esophageal perforation<br />

in a referral center in taiwan. Surg Today 2005; 35:828-832.<br />

15. Altorjay A, Kiss J, Vörös A, Sziranyi E. The <strong>ro</strong>le <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> esophagectomy in<br />

the management <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> esophageal perforations. Ann Thorac Surg 1998;<br />

65:1433-1436.<br />

16. Came<strong>ro</strong>n JL, Kieffer RF, Hendrix TR, Mehigan DG, Baker RR.<br />

Selective nonoperative management <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> contained intrathoracic<br />

esophageal disruptions. Ann Thorac Surg 1979; 27: 404-408.<br />

17. Lawrence DR, Moxon RE, Fountain SW, Ohri SK, Townsend ER,.<br />

Iat<strong>ro</strong>genic oesophageal perforations: a clinical review. Ann R Coll<br />

Surg Engl 1998; 80:115-118.<br />

18. Fischer A, Thomusch O, Benz S, von Dobschuetz E, Baier P,<br />

Hopt UT. Nonoperative treatment <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> 15 benign esophageal<br />

perforations with self-expandable covered metal stents.<br />

Ann Thorac Surg 2006; 81:467-472.<br />

19. Radecke K, Gerken G, Treichel U. Impact <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> a self-expanding,<br />

plastic esophageal stent on various esophageal stenoses, fistulas,<br />

and leakages: a single-center experience in 39 patients. Gast<strong>ro</strong>intest<br />

Endosc 2005; 61:812-818.<br />

20. Gelbmann CM, Ratiu NL, Rath HC, et al. Use <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> self-expandable<br />

plastic stents for the treatment <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> esophageal perforations and<br />

symptomatic anastomotic leaks. Endoscopy 2004; 36:695-699.<br />

21. Sheikh RA, Trudeau WL. Expandable metallic stent placement<br />

in patients with benign esophageal strictures: results <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> long-term<br />

follow-up. Gast<strong>ro</strong>intest Endosc 1998; 48: 227-229.<br />

22. Attar S, Hankins JR, Suter CM, Coughlin TR, Sequeira A, McLaughlin<br />

JS. Esophageal perforation: a therapeutic challenge. Ann Thorac Surg<br />

1990; 50: 45-49.<br />

23. Rao KV, Mir M, Cogbill CL. <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>Management</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> perforations <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng><br />

the thoracic esophagus: a new technic utilizing a pedicle flap <st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng><br />

diaphragm. Am J Surg 1974; 127: 609-612.<br />

24. Grillo HC, Wilkins EW Jr. Esophageal repair following late diagnosis<br />

<st<strong>ro</strong>ng>of</st<strong>ro</strong>ng> intrathoracic perforation. Ann Thorac Surg 1975; 20: 387-399.